Introduction

The global population continues to expand and urbanize, and is expected to peak at 10.3 billion people by 2080 (UN DESA, 2024), with 68% of people expected to live in cities by 2050 (United Nations Habitat, 2022). In OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) member countries, 82% of people already live in urban settings, and this proportion is slowly increasing (World Bank, 2023). Feeding this population in a healthy, sustainable, and equitable manner is a key challenge for humanity (Lawrence and Friel, Reference Lawrence and Friel2020; Tedesco et al., Reference Tedesco, Petit, Billen, Garnier and Personne2017; Willett et al., Reference Willett, Rockstrom, Loken, Springmann, Lang, Vermeulen, Garnett, Tilman, DeClerck, Wood, Jonell, Clark, Gordon, Fanzo, Hawkes, Zurayk, Rivera, De Vries, Majele Sibanda and Murray2019), and there is much interest in the potential of urban agriculture (UA) to contribute to resilient local food systems.

UA refers to the production and distribution of food in urban and peri-urban areas surrounding cities and towns (FAO, 2012; Lovell, Reference Lovell2010; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Brauer and Frank2009; Mougeot, Reference Mougeot2002). It encompasses both commercial enterprises that sell produce, as well as non-commercial initiatives, such as community and home gardens, where food is consumed or shared locally (Mougeot, Reference Mougeot2002; Smit et al., Reference Smit, Nasr and Ratta1996). Some enterprises are hybrids, such as small-scale farms that grow food primarily to feed their households but sell any surplus. UA includes soil-based cultivation such as market gardens, livestock, poultry, and orchards, as well as soil-less cultivation in controlled environments such as aquaponics, hydroponics, and vertical gardens (Orsini et al., Reference Orsini, Pennisi, Michelon, Minelli, Bazzocchi, Sanyé-Mengual and Gianquinto2020). Commercial enterprises generally operate within localized alternative food networks (AFNs) that are enmeshed in their specific ecological, environmental, and socio-political contexts. While urban settings share some global similarities, they also exhibit significant diversity in community dynamics, cultural practices, food systems, climates (and microclimates), ecologies, farmer and customer demographics, political and policy frameworks, economic drivers, supply chains, and technologies (Orsini et al., Reference Orsini, Pennisi, Michelon, Minelli, Bazzocchi, Sanyé-Mengual and Gianquinto2020).

The UA sector presents a range of potential benefits for people and the planet, but also faces major challenges. Lovell (Reference Lovell2010) posits that UA enterprises are ‘multifunctional’ and have intermingled environmental, socio-political, and economic motivators. Much of the literature focuses on the multifarious nature of UA, and a number of reviews have been conducted to understand the environmental (Aerts et al., Reference Aerts, Dewaelheyns and Achten2016; Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Egerer and Daane2019; Clucas et al., Reference Clucas, Parker and Feldpausch-Parker2018; Dorr et al., Reference Dorr, Goldstein, Horvath, Aubry and Gabrielle2021; Wilhelm and Smith, Reference Wilhelm and Smith2018), social (Horst et al., Reference Horst, McClintock and Hoey2017; Ilieva et al., Reference Ilieva, Cohen, Israel, Specht, Fox-Kämper, Fargue-Lelièvre, Poniży, Schoen, Caputo and Kirby2022), health (Audate et al., Reference Audate, Fernandez, Cloutier and Lebel2019; Cano-Verdugo et al., Reference Cano-Verdugo, Flores-García, Núñez-Rocha, Ávila-Ortíz and Nakagoshi-Cepeda2024; Warren et al., Reference Warren, Hawkesworth and Knai2015; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Marquez, Deng, Iu, Fabella, Salonga, Ashardiono and Cartagena2022), and multifunctional impacts of UA (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Tichit, Poulot, Darly, Li, Petit and Aubry2015; Mok et al., Reference Mok, Williamson, Grove, Burry, Barker and Hamilton2014; Orsini et al., Reference Orsini, Pennisi, Michelon, Minelli, Bazzocchi, Sanyé-Mengual and Gianquinto2020; Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Pearson and Pearson2011; Rao et al., Reference Rao, Patil, Singh, Roy, Pryor, Poonacha and Genes2022; Srinivasan and Yadav, Reference Srinivasan and Yadav2023; Weidner et al., Reference Weidner, Yang and Hamm2019). There is considerably less understanding of the economic sustainability and associated organizational viability of UA enterprises, and researchers have called for more investigation of this aspect (Appolloni et al., Reference Appolloni, Pennisi, Tonini, Marcelis, Kusuma, Liu, Balseca, Jijakli, Orsini and Monzini2022; Dimitri et al., Reference Dimitri, Oberholtzer and Pressman2016; Kafle et al., Reference Kafle, Hopeward and Myers2022; Milestad et al., Reference Milestad, de Jong, Bustamante, Molin, Martin and Malone Friedman2024; Moglia, Reference Moglia2014; Morel et al., Reference Morel, San Cristobal and Léger2018; Stolhandske and Evans, Reference Stolhandske and Evans2016).

The 38 OECD member countries primarily share economic and social factors, with a focus on development and governance. Member countries are predominantly democracies with neoliberal market-based economies, and most are defined as ‘high-income’ by the World Bank, with the exception of Mexico, Turkey, and Colombia, which are categorized as ‘upper-middle income’ (World Bank, 2024). To endure within such socio-political contexts, commercial enterprises generally need to be economically sustainable or find organizational viability in other ways. As Hunold articulates:

the financial sustainability of urban agriculture would seem to be an important condition of its long-term stability and of its capacity to contribute to wider community and economic development goals (Hunold et al., Reference Hunold, Sorunmu, Lindy, Spatari and Gurian2016).

Therefore, the primary aim of this study is to address the knowledge gap regarding factors that influence the economic sustainability of soil-based commercial urban and peri-urban farming in OECD countries by reviewing literature on this topic. A secondary aim is to identify broader factors that influence the organizational viability of these enterprises and their networks. The economic sustainability of commercial urban farms is a central focus of this review. Non-commercial UA typologies, such as community gardens and home gardens, are not operated as businesses and pursue different goals and economic imperatives. Therefore, this review focuses on UA operations that include a commercial component. The original scope for this review included both soil-based and soil-less UA typologies; however, preliminary search results indicated that the scope was too large for one review. Additionally, soil-less enterprises, such as hydroponics and aquaponics, are often situated in controlled environments and tend to face a different set of economic, technical, and regulatory challenges compared to soil-based enterprises (Benis and Ferrao, Reference Benis and Ferrao2018; Buehler and Junge, Reference Buehler and Junge2016; Burritt et al., Reference Burritt, de Souza and Peterson2025; Fussy and Papenbrock, Reference Fussy and Papenbrock2022; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Marquez, Deng, Iu, Fabella, Salonga, Ashardiono and Cartagena2022). Therefore, the authors decided to limit the scope of this review to soil-based UA enterprises in order to allow for more focused and meaningful analysis.

For the purposes of this review, economic sustainability relates to the monetary flows through an organization, such as the financial inputs and outputs that determine profitability, as termed ‘economic benchmarks’ by Hunold et al. (Reference Hunold, Sorunmu, Lindy, Spatari and Gurian2017). Viability refers to the broader forces that may enable or disable an enterprise (Latruffe et al., Reference Latruffe, Diazabakana, Bockstaller, Desjeux, Finn, Kelly, Ryan and Uthes2016), including (but not limited to) socio-political context, ecological systems, human networks, labor, skills and information, internal and external governance frameworks, regulations, technology, innovation, and business systems. In line with the collegiate goals of OECD member countries, this review aims to provide insights and recommendations to help strengthen urban and peri-urban farming networks in OECD member countries. This topic has the potential for far-reaching impact, as it intersects with a diverse range of disciplines, including social theory (Tornaghi, Reference Tornaghi2014), agriculture, economics, sustainability, transition theory (Irwin, Reference Irwin2015), livable cities, urban planning, nutrition, and health, each offering unique theoretical and methodological frameworks.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted according to the Arksey and O’Malley framework (Arksey and O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005; Munn et al., Reference Munn, Peters, Stern, Tufanaru, McArthur and Aromataris2018) and followed the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred-Reporting-Items-for-Systematic-Reviews extension for Scoping Review) checklist (PRISMA, 2020; Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsley, Weeks, Hempel, Akl, Chang, McGowan, Stewart, Hartling, Aldcroft, Wilson, Garritty and Straus2018). The following steps were actioned: (1) identify the research question; (2) identify relevant studies; (3) select studies according to inclusion criteria; (4) chart data; (5) collate, summarize, and report the results. The protocol for the scoping review was registered in the Open Science Framework (2024).

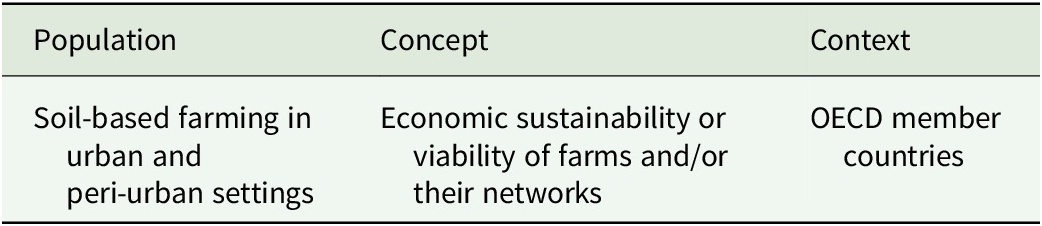

The ‘Population, Concept and Context’ (PCC) framework (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2024) was used to construct the research question, as follows: ‘What factors influence the economic sustainability/viability of small-scale farming/agricultural enterprises located in urban and peri-urban areas within OECD member countries?’ (Table 1).

Table 1. The ‘population, concept, and context’ (PCC) framework

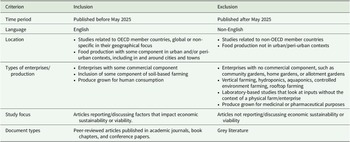

Articles were selected for inclusion in this scoping review according to a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of inclusion and exclusion criteria

Searches were conducted in four databases, Scopus, ProQuest, Environment Complete, and Web of Science Core Collection, on April 30, 2025. Three concepts defined the search strategy, namely: (1) urban agriculture/farms; (2) economic sustainability/viability; and (3) location (i.e., OECD countries) (Supplementary Item 1). The feasibility of the search was demonstrated through preliminary searches conducted in July 2024 in collaboration with a university librarian, during which the search strategy was tested and refined using sentinel articles (n = 3).

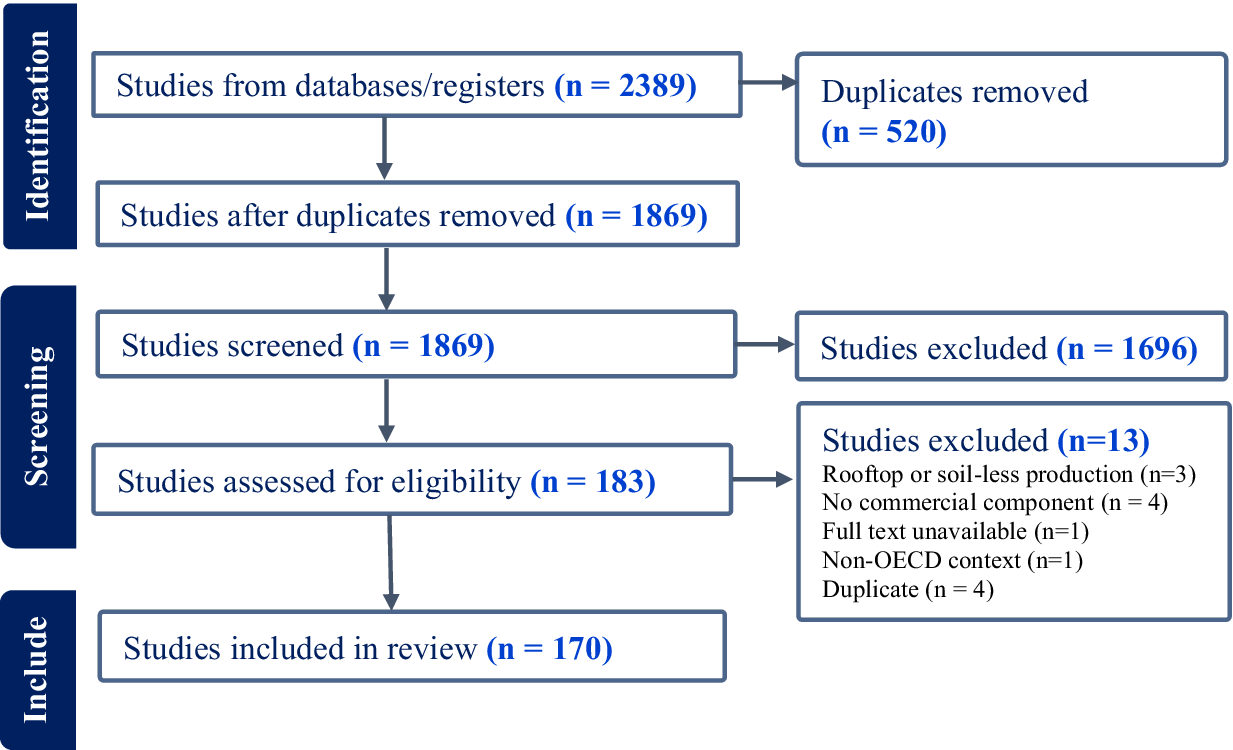

Identified records from each database were uploaded into Covidence software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia; available at https://www.covidence.org), where duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers (SP, KC) screened titles, abstracts, and full texts of the retrieved sources. Discrepancies or uncertainties were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (ASN) until consensus was achieved. Two researchers (SP, KC) strictly applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine the final included studies. The article selection process is summarized according to the PRISMA flowchart (PRISMA, 2020) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA-ScR flowchart illustrating the study selection process.

The data extraction template was reviewed by three researchers (SP, ASN, KC), each of whom extracted a random sample of 10 articles to confirm methodological consistency. Data were descriptively and narratively synthesized according to the research question and were summarized in tables by one researcher (SP). Two researchers (ASN, KC) verified the quality of the extracted data, which included: article reference (authors, title, journal, year of publication), country, aims/objectives, methodology/study design, key results, main themes, and exemplar quotations. Themes were identified inductively through immersion in the findings reported by each of the included articles. In an attempt to synthesize and summarize the diverse outcomes across the large number of articles included in the review, a final step was to count the frequency of each identified theme for every article (n = 170) and then sum the frequencies to determine the overall prevalence of each theme across the entire review. No quality appraisal of the sources was conducted, as per the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines for scoping reviews (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2024).

Results

The search identified 2,389 articles across four databases (Fig. 1). After removing 520 duplicates, 1,869 articles remained. Abstract screening excluded 1,696 studies of these, leaving 183 articles for full-text review. Following this review, 13 more studies were excluded, resulting in 170 studies included in the scoping review. Some studies examined UA enterprises and networks spanning urban, peri-urban, and rural areas, such as Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) networks, micro-farms, and food hubs. These were included in the review due to their relevant insights into urban and peri-urban farm viability.

Of the 170 articles, the majority were published from 2015 to 2025 (n = 139, 82%), with the highest number of studies published in 2022 (n = 20, 12%). Only four studies were published prior to 2008 (n = 4, 2%).

A high proportion of studies investigated populations in Europe (n = 73, 43%), with the majority of these in Italy (n = 17), Germany (n = 15), France (n = 14), and Spain (n = 9). One third of studies were in North American contexts (n = 56, 33%), with most from the United States (n = 46), followed by Canada (n = 12), and two studies that were in both. Just under one tenth of studies investigated the Asia Pacific region (n = 15, 9%), looking at either Australia (n = 11) or Japan (n = 4). A small number of studies were from Central/South America (n = 4, 2%), and only focused on Mexico. Some studies were non-specific or global in their geographical focus (n = 22, 13%), and some studies were conducted across multiple countries and/or regions (n = 19), but each is reported in the classification above (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Geographical location of studies within the literature, with OECD countries represented as a slightly darker grey color. Note that some studies assess more than one geographical location.

Most of the articles were primary research (79%, n = 134) where data were collected from populations and analyzed. Over half of these used mixed-methods (n = 77), around one quarter used qualitative methods to understand the experiences of people involved in the UA sector (n = 33), and less than one-fifth used quantitative methods, typically to investigate on-farm production efficiencies (n = 24). The remainder were discussion papers (n = 14, 8%), review articles (n = 11, 6%), book chapters (n = 6, 4%), and conference papers (n = 5, 3%).

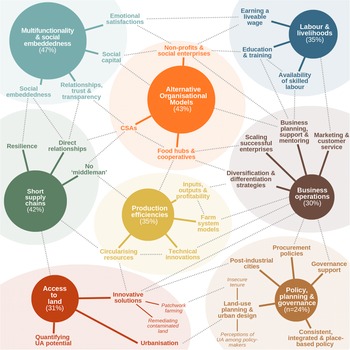

The major findings of the papers are summarized according to the following identified themes (Table 3): (i) short supply chains; (ii) multifunctionality and social embeddedness; (iii) alternative organizational models; (iv) access to land; (v) policy, planning and governance; (vi) labor and livelihoods; (vii) production efficiencies; and (viii) business operations (Table 1). See Supplementary Item 2 for details about each article. Some of the themes were further grouped into subthemes, many of which have interdependencies with each other (Fig. 3).

Table 3. Summary of data extraction with all articles and their themes organized according to the geographical regions of their studies

Figure 3. Themes (large white text in colored circles), sub-themes (large, colored text), and sub-sub themes (small italics, colored text) in the literature, as well as key interdependencies (grey dashed lines).

Frequency of themes identified across the 170 papers, in descending order were: multifunctionality and social embeddedness (n = 80, 47%); alternative organizational structures (n = 73, 43%); short supply chains (n = 71, 42%); labor and livelihoods (n = 60, 35%); production efficiencies (n = 59, 35%); access to land (n = 52, 31%); business operations (n = 51, 30%); and policy, planning and governance (n = 41, 24%). Interestingly, the same dominant themes and subthemes were evident across a breadth of settings and countries, with each article discussing 2.9 themes on average. According to the primary and secondary aims of the review, themes are reported in order of those related to economic sustainability, followed by those that are related to viability.

Theme 1: Production efficiencies

Production efficiencies emerged as a common theme, with articles investigating the inputs, outputs, and profitability of urban farms as well as the potential for technical innovations and circularized resources to increase efficiencies.

Inputs, outputs, and profitability

Some studies reported that economic sustainability was achievable for urban and peri-urban farms growing a variety of produce types across a range of scales, including an organic micro farm in France (Morel et al., Reference Morel, Guégan and Léger2016), a study cultivating high value crops in Australia (Kafle et al., Reference Kafle, Hopeward and Myers2022), two family-run asparagus farms in Turkey (Özden and Acar, Reference Özden and Acar2022), and a patchwork farm in Canada (Morin, Reference Morin2009). A study of agriculture in four US states (California, Idaho, Oregon, Washington) reported that, in some cases, urbanization created more opportunities than barriers for agriculture, with urban farms having higher production costs, but also higher net incomes due to higher sales prices for their produce (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Fisher and Pascual2011).

Conversely, profitability often varied widely across enterprises within the studies, and many urban farms were not economically sustainable (Conseil et al., Reference Conseil, Riviere, De Lapparent, Berry, Pellat, Leroy, Arnaud-Dupont, Icard, Hervouet, Herbeth and Sautereau2022; Hunold et al., Reference Hunold, Sorunmu, Lindy, Spatari and Gurian2017; Lohest et al., Reference Lohest, Joris Van and Bauler2019; Waldman et al., Reference Waldman, Conner, Biernbaum, Hamm and Montri2012). In the United States, a national survey of 315 urban farms found that less than one third of primary farmers earned a livable wage from the sale of produce and almost half reported less than US$10,000 in sales per annum (Dimitri et al., Reference Dimitri, Oberholtzer and Pressman2016; Oberholtzer et al., Reference Oberholtzer, Dimitri and Pressman2014). Labor as well as capital costs were reported to be key impediments, with the cost of trucks, soil, refrigeration, land tunnels, greenhouses, machinery storage space, and irrigation challenging the financial viability of enterprises.

Farm system models

A number of studies modeled various aspects of urban farming systems in order to provide tools for farmers to use and to inform best practice, to predict and maximize efficiencies, and potentially support the economic sustainability of businesses (Brulard et al., Reference Brulard, Cung, Catusse and Dutrieux2019; Chang and Morel, Reference Chang and Morel2018; Coscia and Russo, Reference Coscia, Russo, Bisello, Vettorato, Laconte and Costa2018; Hatziioannou and Kokkinos, Reference Hatziioannou and Kokkinos2021; Morel et al., Reference Morel, San Cristobal and Léger2017, Reference Morel, San Cristobal and Léger2018; Paut et al., Reference Paut, Sabatier, Dufils and Tchamitchian2021; Zanzi et al., Reference Zanzi, Vaglia, Spigarolo and Bocchi2021). Morel et al. (Reference Morel, San Cristobal and Léger2017, Reference Morel, San Cristobal and Léger2018) developed a validated model for micro farmers to test profitability across a range of production inputs, business scenarios, and environmental conditions (Morel et al., Reference Morel, San Cristobal and Léger2017, Reference Morel, San Cristobal and Léger2018). Their MERLIN computational model helps small-scale farmers test and refine profit-maximizing strategies. Applied to 10 socially motivated microfarms in London, it showed viability was possible, particularly when using affordable land (e.g. on city outskirts or subsidized municipal sites) in exchange for social services (e.g. community workshops); cultivating high value fast-growing crops (e.g. leafy greens); selling at high prices to local restaurants; using high tunnels to extend the growing season; relying on volunteers; and offering lower pay in exchange for non-material benefits (Chang and Morel, Reference Chang and Morel2018).

Technical innovations

Technical innovations that undertake, simplify, or improve farming processes in urban environments were reported to increase the economic sustainability of farms by reducing labor, improving precision, expanding capacity, or minimizing other costs (Christmann et al., Reference Christmann, Graf-Drasch and Schäfer2025; D’Arpa et al., Reference D’Arpa, Colangelo, Starace, Petrosillo, Bruno, Uricchio and Zurlini2016; García-Vanegas et al., Reference García-Vanegas, García-Bonilla, Forero, Castillo-García and Gonzalez-Rodriguez2023; Holt et al., Reference Holt, Shukla, Hochmuth, Muñoz-Carpena and Ozores-Hampton2017; Umeda, Reference Umeda2007). Some studies compared technologies in specific growing contexts, including one showing that ‘cable driven robots’ outperformed conventional ‘suspended parallel robots’ in accuracy and reach for repetitive tasks in greenhouses and open fields (García-Vanegas et al., Reference García-Vanegas, García-Bonilla, Forero, Castillo-García and Gonzalez-Rodriguez2023). Harnessing geothermal energy to heat greenhouses in cold climates was found to reduce energy costs and extend the growing season with low establishment costs, and could therefore increase efficiencies and reduce CO2 emissions (D’Arpa et al., Reference D’Arpa, Colangelo, Starace, Petrosillo, Bruno, Uricchio and Zurlini2016; Umeda, Reference Umeda2007).

Circularizing resources

Several studies evaluated the efficacy and challenges of collecting, treating, and repurposing resources like wastewater, grey water, biosolids, rainwater, stormwater, and kitchen scraps, reporting significant benefits for irrigation, nutrients, and cost savings (Barboz et al., Reference Barboz, Morales, Barrantes, Moreno and Lwanga2010; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Sim, Lin and Lai2013; Moglia, Reference Moglia2014; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Herrero, Hatt, Farrelly and McCarthy2018; Novaes and Marques, Reference Novaes and Marques2023; Tedesco et al., Reference Tedesco, Petit, Billen, Garnier and Personne2017; Wielemaker et al., Reference Wielemaker, Weijma and Zeeman2018). A systematic review found that US wastewater facilities collect 32 billion gallons of wastewater daily and 8 million tonnes of nutrient-rich biosolids annually (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Sun, Xia, Deines, Cooper, Pallansch and Wang2022). The authors proposed processing and recirculating resources to surrounding farms as a cost-effective, reliable, drought-proof supply of water, fertilizer, soil amendments, nutrients (including finite phosphorus for growing food), energy, and even materials like garden pots and bioplastics (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Sun, Xia, Deines, Cooper, Pallansch and Wang2022). Tedesco et al. (Reference Tedesco, Petit, Billen, Garnier and Personne2017) found that ‘recoupling’ producers and consumers within communities could enable circular resource use, shorten supply chains, generate fuel from waste, and cut costs, though infrastructure was needed (Tedesco et al., Reference Tedesco, Petit, Billen, Garnier and Personne2017). Sundov and Gajdic (Reference Sundov and Gajdic2019) proposed expanding food hubs into multifunctional centers that distribute food and return waste (e.g. scraps, cardboard packaging) to farms as bio-fertilizer. These place-based hubs could strengthen local producer-consumer connections, bypass conventional supply chains, boost urban resilience, save money, reduce waste, and embed UA within city systems (Sundov and Gajdic, Reference Sundov and Gajdic2019).

Theme 2: Business operations

A large number of articles discussed the importance of business planning, mentorship and marketing, and customer service strategies for the success of UA enterprises. Many farms employed diversification and differentiation strategies in order to mitigate risk and maximize profitability, and some researchers investigated ways to scale successful enterprises.

Business planning

Business planning and financial literacy could increase economic sustainability by streamlining the vision, goals, and operational strategy of organizations (Albrecht and Wiek, Reference Albrecht and Wiek2021; Brislen et al., Reference Brislen, Barham and Feldstein2017; Genus et al., Reference Genus, Iskandarova and Brown2021; Gu et al., Reference Gu, Paul, Nixon and Duschack2012; Sitaker, McCall, Kolodinsky, et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Belarmino, Wang, Kolodinsky, Becot, McGuirt, Ammerman, Pitts and Seguin-Fowler2020; Slámová et al., Reference Slámová, Kruse, Belčáková and Dreer2021). Tailored business plans helped farms understand and capitalize on the opportunities in their specific context (Slámová et al., Reference Slámová, Kruse, Belčáková and Dreer2021), however researchers reported that urban farmers needed to remain agile and adaptable, responding to and leveraging opportunities that may arise in their context (Barrett and Leeds, Reference Barrett and Leeds2022; Cohen and Reynolds, Reference Cohen and Reynolds2015; Morel and Léger, Reference Morel and Léger2016; Slámová et al., Reference Slámová, Kruse, Belčáková and Dreer2021).

Diversification and differentiation strategies

Many urban farms enhanced their economic sustainability through diversification strategies, including multiple (on and off-farm) income streams, varied distribution channels (Galt et al., Reference Galt, Bradley, Christensen, Kim and Lobo2016; Jablonski et al., Reference Jablonski, Sullins and Dawn Thilmany2019; Medici et al., Reference Medici, Canavari and Castellini2021; Rommel et al., Reference Rommel, Posse, Wittkamp, Paech, Filho, Kovaleva and Popkova2022; Stolhandske and Evans, Reference Stolhandske and Evans2016; Torquati et al., Reference Torquati, Giacchè, Marino, Pastore, Mazzocchi, Niño, Arnaiz and Daga2018; Yoshida et al., Reference Yoshida, Yagi, Kiminami and Garrod2019), and a broad range of offerings (Balázs et al., Reference Balázs, Pataki and Lazányi2016; Lèger and Morel, Reference Lèger and Morel2016; Milestad et al., Reference Milestad, de Jong, Bustamante, Molin, Martin and Malone Friedman2024; Morel and Léger, Reference Morel and Léger2016; Mussillon and Morel, Reference Mussillon and Morel2022). These strategies were purported to spread risk and maximize income (Bertran-Vilà et al., Reference Bertran-Vilà, Ayari, Ayari and Jessica Geraldine Villatoro2022; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Ruiz-Menjivar and DeLong2022; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Norrman and Berg2021; McKee, Reference McKee2018; Morel and Léger, Reference Morel and Léger2016; Mussillon and Morel, Reference Mussillon and Morel2022; Oberholtzer et al., Reference Oberholtzer, Dimitri and Pressman2014; Yoshida et al., Reference Yoshida, Yagi, Kiminami and Garrod2019). A study of German CSAs found some farms used hybrid models, cooperating with non-CSA businesses to offer ‘add-on’ products such as bread, coffee, and cooking oil (Rommel et al., Reference Rommel, Posse, Wittkamp, Paech, Filho, Kovaleva and Popkova2022). This expanded customer choice, supported adjacent businesses, and strengthened food system resilience (Rommel et al., Reference Rommel, Posse, Wittkamp, Paech, Filho, Kovaleva and Popkova2022). Diversified income, referred to as ‘polyincomes’ (Genus et al., Reference Genus, Iskandarova and Brown2021) or ‘pluriactivities’ (Yoshida et al., Reference Yoshida, Yagi, Kiminami and Garrod2019), included workshops, farm tours and class field trips, speaker engagements, and consulting (Galt et al., Reference Galt, O’Sullivan, Beckett and Hiner2012; Lohest et al., Reference Lohest, Joris Van and Bauler2019; Medici et al., Reference Medici, Canavari and Castellini2021; Oberholtzer et al., Reference Oberholtzer, Dimitri and Pressman2014; Pölling and Mergenthaler, Reference Pölling and Mergenthaler2017; Schutzbank and Riseman, Reference Schutzbank and Riseman2013; Stolhandske and Evans, Reference Stolhandske and Evans2016). An urban farmer from Vancouver said,

we can’t charge enough for the food we are growing, so we must increase the value-added side of the business (Stolhandske and Evans, Reference Stolhandske and Evans2016).

A national survey of 315 US urban farms found 60% relied on off-farm income, while 31% required grants or fundraising to remain viable (Oberholtzer et al., Reference Oberholtzer, Dimitri and Pressman2014). Agritourism was a common revenue stream (Bertran-Vilà et al., Reference Bertran-Vilà, Ayari, Ayari and Jessica Geraldine Villatoro2022; Medici et al., Reference Medici, Canavari and Castellini2021; Pölling and Mergenthaler, Reference Pölling and Mergenthaler2017; Pölling et al., Reference Pölling, Mergenthaler and Lorleberg2016; Slámová et al., Reference Slámová, Kruse, Belčáková and Dreer2021; Sroka et al., Reference Sroka, Pölling and Mergenthaler2019). In Europe, protected European Agricultural Landscapes (EALs) enabled income from events, accommodation, festivals, tastings, and ‘pick your own’ experiences (Slámová et al., Reference Slámová, Kruse, Belčáková and Dreer2021). However, farmers often needed education about the cultural value of these historical patterns and cultural landscapes to capitalize on such opportunities (Slámová et al., Reference Slámová, Kruse, Belčáková and Dreer2021). Some UA enterprises bolstered their viability through market differentiation, offering niche or high-quality products (Lèger and Morel, Reference Lèger and Morel2016; Oberholtzer et al., Reference Oberholtzer, Dimitri and Pressman2014; Pölling and Mergenthaler, Reference Pölling and Mergenthaler2017), obtaining accreditations/certifications, and using regional branding (Lohest et al., Reference Lohest, Joris Van and Bauler2019; Simón-Rojo et al., Reference Simón-Rojo, Couceiro, del Valle and Tojo2020; Slámová et al., Reference Slámová, Kruse, Belčáková and Dreer2021; Torquati et al., Reference Torquati, Giacchè, Marino, Pastore, Mazzocchi, Niño, Arnaiz and Daga2018). Products grown in these European locations can be labeled as ‘Protected Designation of Origin’, ‘Protected Geographical Indication’, and ‘Traditional Specialities Guaranteed’ (Slámová et al., Reference Slámová, Kruse, Belčáková and Dreer2021; Torquati et al., Reference Torquati, Giacchè, Marino, Pastore, Mazzocchi, Niño, Arnaiz and Daga2018).

Marketing and customer service

Marketing, advertising, and customer service were critical for the economic sustainability of UA enterprises (Appolloni et al., Reference Appolloni, Pennisi, Tonini, Marcelis, Kusuma, Liu, Balseca, Jijakli, Orsini and Monzini2022; Morel et al., Reference Morel, San Cristobal and Léger2018; Paül and McKenzie, Reference Paül and McKenzie2013; Specht et al., Reference Specht, Weith, Swoboda and Siebert2016; Stolhandske and Evans, Reference Stolhandske and Evans2016). Marketing was used to communicate the values of the enterprise, highlight their production methods and accreditations, and to build acceptance for locally produced food within the community (Specht et al., Reference Specht, Weith, Swoboda and Siebert2016; Stolhandske and Evans, Reference Stolhandske and Evans2016). Visual identity, product design, and labeling helped build a recognizable brand (Paül and McKenzie, Reference Paül and McKenzie2013; Specht et al., Reference Specht, Weith, Swoboda and Siebert2016). Marketing channels included publicly facing events such as farmers’ markets, festivals, and workshops, as well as digital platforms such as e-newsletters, websites, and social media profiles (Diehl, Reference Diehl2020; Haley, Reference Haley2010; Stolhandske and Evans, Reference Stolhandske and Evans2016). When modeling the viability of French microfarms, Morel et al. (Reference Morel, San Cristobal and Léger2018) found that marketing and investment strategies played a key role in the ability of a farm to generate income. Understanding customer expectations and meeting their needs contributed to the economic sustainability of UA enterprises (Barrett and Leeds, Reference Barrett and Leeds2022; Slámová et al., Reference Slámová, Kruse, Belčáková and Dreer2021). Barrett and Leeds (Reference Barrett and Leeds2022) pointed out the importance of ‘awesome customer service’ as a key factor in the viability of urban farms, and outlined the steps involved in developing and implementing a customer service plan.

Retaining customers, particularly with direct distribution models such as vegetable box subscription systems, farmers’ markets, and CSAs, was found to be important for the economic sustainability of urban farms (Freedman and King, Reference Freedman and King2016; Galt et al., Reference Galt, Kim, Munden-Dixon, Christensen and Bradley2019; McKee, Reference McKee2018; Medici et al., Reference Medici, Canavari and Castellini2021). A study of 80 CSAs in California iterated that retaining members from season to season was ‘a core part of economic well-being’ for farmers, yet most CSAs in the study were not retaining enough customers to maintain economic sustainability (Galt et al., Reference Galt, Kim, Munden-Dixon, Christensen and Bradley2019).

Scaling successful enterprises

Numerous studies assessed the mechanisms by which successful UA enterprises could be scaled to reach more people, initiate institutional change, and change mindsets (Marradi and Mulder, Reference Marradi and Mulder2022; Voltan, Reference Voltan2017). Marradi and Mulder (Reference Marradi and Mulder2022) developed and validated a methodology to identify and address challenges scaling a successful initiative from one context to others with different ecological, political and/or cultural contexts. The approach draws on co-design and transition design methodologies (Marradi and Mulder, Reference Marradi and Mulder2022). A study of nine CSAs in Nova Scotia, Canada, found strong ‘bonding ties’ (between family, friends, neighbors, and co-workers) and weak ‘bridging ties’ (connecting actors within networks) across organizations (Voltan, Reference Voltan2017). Strengthening bridging ties, through knowledge and skills sharing, was proposed as key to scaling and expanding the CSA network (Voltan, Reference Voltan2017).

Theme 3: Access to land

Difficultly accessing secure, arable, affordable land was reported as a key challenge for soil-based UA in many OECD member countries and affected the financial sustainability of enterprises. Challenges stemmed from limited land availability, high costs, and the prioritization of housing and infrastructure over farming; however some enterprises implemented innovative solutions to access affordable land.

Urbanization

With an expanding and increasingly urbanized global population, many studies reported that cities were densifying and sprawling into surrounding peri-urban and rural regions, resulting in fragmentation and displacement of farmland (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Ruiz-Menjivar and DeLong2022; Choy and Buxton, Reference Choy, Buxton, Farmar-Bowers, Higgins and Millar2013; Diehl, Reference Diehl2020; James, Reference James2015; Paül and McKenzie, Reference Paül and McKenzie2013; Rao et al., Reference Rao, Patil, Singh, Roy, Pryor, Poonacha and Genes2022; Simón-Rojo et al., Reference Simón-Rojo, Couceiro, del Valle and Tojo2020; Sroka et al., Reference Sroka, Pölling and Mergenthaler2019; Wästfelt and Zhang, Reference Wästfelt and Zhang2018; Yurday et al., Reference Yurday, YaĞCi and İŞCan2021). Prime agricultural land in urban and peri-urban locations was often more valuable when sold for urban development, resulting in the conversion of much farmland to housing in OECD settings (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Ruiz-Menjivar and DeLong2022; Carey et al., Reference Carey, Krumholz, Duignan, McConell, Browne, Burns and Lawrence2010; Kafle et al., Reference Kafle, Hopeward and Myers2022; Paül and McKenzie, Reference Paül and McKenzie2013; Simón-Rojo et al., Reference Simón-Rojo, Couceiro, del Valle and Tojo2020; Spataru et al., Reference Spataru, Faggian and Docking2020; Yurday et al., Reference Yurday, YaĞCi and İŞCan2021). In Greater Western Sydney, Australia, long known as Sydney’s ‘food bowl’, urbanization has driven the rezoning and sale of agricultural land for housing, with land-owning farmers selling to capitalize on higher land values (Diehl, Reference Diehl2020; Lawton and Morrison, Reference Lawton and Morrison2022). In many OECD member countries, urbanization has led to the displacement of soil-based farming to rural areas or marginal urban land, often characterized by contamination, insecure tenure, development pressure, or exposure to natural disasters, such as flooding (DeLind, Reference DeLind2015; James, Reference James2015; Oberholtzer et al., Reference Oberholtzer, Dimitri and Pressman2014; Rozanski and Gavin, Reference Rozanski and Gavin2023; Wästfelt and Zhang, Reference Wästfelt and Zhang2018).

Innovative solutions

Some farmers have found innovative solutions to access affordable urban land, though they often come with additional risks and challenges. In Michigan, USA, farmers cultivated flood-affected abandoned land, overcoming the land access challenge, but exposing them to other risks that threatened the viability of their enterprises, such as flooding and associated contamination (DeLind, Reference DeLind2015). Some researchers investigated potential solutions to safely grow crops on contaminated land, including using sunflowers to help remove contaminants from soil through phytoremediation (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2010), grazing goats on closed landfill sites (Hard et al., Reference Hard, Brusseau and Ramirez-Andreotta2019), and building clean topsoil over polluted soil by using locally sourced organic and mineral growing substrates (Barbillon et al., Reference Barbillon, Lerch, Araujo, Manouchehri, Robain, Pando-Bahuon, Cambier, Nold, Besançon and Aubry2023). In the USA and Canada, many urban farmers cultivated a ‘patchwork’ of multiple backyards as micro-farms, often known as ‘SPIN’ (Small Plot INtensive) farms (Newman, Reference Newman2008; Rozanski and Gavin, Reference Rozanski and Gavin2023; Schutzbank and Riseman, Reference Schutzbank and Riseman2013; Stolhandske and Evans, Reference Stolhandske and Evans2016). This land was often accessed cheaply, for free, or via trade for produce or labor, making it affordable for urban farmers (Rozanski and Gavin, Reference Rozanski and Gavin2023; Schutzbank and Riseman, Reference Schutzbank and Riseman2013). However, patchwork farms often operated on borrowed land with non-legally binding agreements with landowners, compromising their long-term viability (Rozanski and Gavin, Reference Rozanski and Gavin2023; Stolhandske and Evans, Reference Stolhandske and Evans2016).

Quantifying UA potential

Building an argument for wider-scale implementation of UA in OECD countries, numerous studies quantified the potential of cities or towns to grow food to feed their populations (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2010; Haberman et al., Reference Haberman, Gillies, Canter, Rinner, Pancrazi and Martellozzo2014; MacRae et al., Reference MacRae, Gallant, Patel, Michalak, Bunch and Schaffner2010; Patel and MacRae, Reference Patel and MacRae2012). For instance, in Detroit, 4,800 acres of vacant public land could provide 76% of the population’s vegetable and 42% of its fruit needs (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2010). While such scenarios require significant urban shifts, modeling studies demonstrate UA’s potential to feed urban populations and support a vision of urban farming as a thriving and essential part of resilient, healthy urban environments.

Theme 4: Policy, planning, and governance

Policy, planning, and governance were key topics in the literature, with articles discussing the role of planning in the allocation and protection of land for farming, as well as broader regulatory and governance mechanisms that impact the financial sustainability of soil-based commercial UA in OECD countries.

Land-use planning and urban design

Land-use planning and urban design were found to be crucial for the integration of productive landscapes with urban environments. In recent decades, concepts like the ‘edible city’, ‘food urbanism’, and ‘agrarian urbanism’ have brought food and farming back into focus within urban planning and design discourse (Nasr and Potteiger, Reference Nasr and Potteiger2023). However, these ideas have not always translated into practical implementation (Gómez-Villarino et al., Reference Gómez-Villarino, Urquijo, Villarino and García2021), and planning policies continue to impact urban farming in many OECD settings (Simón-Rojo et al., Reference Simón-Rojo, Couceiro, del Valle and Tojo2020; Spataru et al., Reference Spataru, Faggian and Docking2020; Stone et al., Reference Stone, Thompson, Zimmerman, Brighenti and Liebman2024; van der Gaast et al., Reference van der Gaast, Jansma and Wertheim-Heck2023). For example, in Melbourne, Australia, policy and planning frameworks were reported to be driven by a ‘paradigm of continuous urban growth’ which was ‘ill-equipped to capture the economic and non-economic benefits of agriculture’ (Spataru et al., Reference Spataru, Faggian and Docking2020). Researchers recommended governance initiatives to protect and allocate land for farming in the design of new developments, as well as the assimilation of farming into existing suburbs within OECD member countries (Fricano and Davis, Reference Fricano and Davis2020; Kafle et al., Reference Kafle, Hopeward and Myers2022; Patel and MacRae, Reference Patel and MacRae2012; Tedesco et al., Reference Tedesco, Petit, Billen, Garnier and Personne2017). Mechanisms included land-use strategies, plans, zoning, subsidies, agricultural buffers, ‘right to farm’ ordinances, acquisition of farmland through trusts, financial incentives, taxation, and national legal regulations (Kafle et al., Reference Kafle, Hopeward and Myers2022; Pawlowski, Reference Pawlowski2018; Spataru et al., Reference Spataru, Faggian and Docking2020). Fricano and Davis (Reference Fricano and Davis2020) found that UA expansion often correlated with supportive land use policies, such as a Land Use Policy Map, Open Space Plan, or a Neighborhood. However, perceptions of UA as not being ‘real’ farming among urban planners hindered its integration into municipal planning (Rao et al., Reference Rao, Patil, Singh, Roy, Pryor, Poonacha and Genes2022).

Consistent, integrated, place-based policy

Studies showed that consistent, integrated and place-based policy across levels of government and departments was needed to protect farmland and to support the economic sustainability and viability of UA and AFNs (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Ruiz-Menjivar and DeLong2022; Carey et al., Reference Carey, Krumholz, Duignan, McConell, Browne, Burns and Lawrence2010; Choy and Buxton, Reference Choy, Buxton, Farmar-Bowers, Higgins and Millar2013; Dedeurwaerdere et al., Reference Dedeurwaerdere, De Schutter, Hudon, Mathijs, Annaert, Avermaete, Bleeckx, de Callataÿ, De Snijder, Fernández-Wulff, Joachain and Vivero2017; Delgado, Reference Delgado2017; Fanfani et al., Reference Fanfani, Battisti and Agosta2024; Milestad et al., Reference Milestad, de Jong, Bustamante, Molin, Martin and Malone Friedman2024; Miralles-Garcia, Reference Miralles-Garcia2023; Nasr and Potteiger, Reference Nasr and Potteiger2023; Pawlowski, Reference Pawlowski2018; Recasens et al., Reference Recasens, Alfranca and Maldonado2016; Torquati et al., Reference Torquati, Giacchè, Marino, Pastore, Mazzocchi, Niño, Arnaiz and Daga2018; Valencia et al., Reference Valencia, Qiu and Chang2022; Yurday et al., Reference Yurday, YaĞCi and İŞCan2021). Urban food systems emerged from their local socio-cultural, political, geographic, and climatic contexts, and studies found that place-based, integrated, interdisciplinary, inclusive policy was needed to support the specific needs of urban farming related to specific conditions (Pawlowski, Reference Pawlowski2018; Torquati et al., Reference Torquati, Giacchè, Marino, Pastore, Mazzocchi, Niño, Arnaiz and Daga2018). To support UA in US cities, Pawlowski (Reference Pawlowski2018) recommended first evaluating existing resources and policies in the area, then developing a place-based Comprehensive Plan that considered all participants in the city’s food economy, including residents, farmers, and other supply chains. Other governance mechanisms to support UA networks included supportive regulatory frameworks, financial policies, local food strategies, public-private partnerships, grants, subsidies, mentorship, as well as access to facilities and services (Dedeurwaerdere et al., Reference Dedeurwaerdere, De Schutter, Hudon, Mathijs, Annaert, Avermaete, Bleeckx, de Callataÿ, De Snijder, Fernández-Wulff, Joachain and Vivero2017; Hunold et al., Reference Hunold, Sorunmu, Lindy, Spatari and Gurian2017; Lamont, Reference Lamont2013; Oberholtzer et al., Reference Oberholtzer, Dimitri and Pressman2014; Simón-Rojo et al., Reference Simón-Rojo, Couceiro, del Valle and Tojo2020; Stone et al., Reference Stone, Thompson, Zimmerman, Brighenti and Liebman2024; Zhu and Tsoulfas, Reference Zhu and Tsoulfas2024).

Ambiguous government policies could be confusing and time consuming for farmers to navigate, and sometimes resulted in farmland not being protected (Carey et al., Reference Carey, Krumholz, Duignan, McConell, Browne, Burns and Lawrence2010; Choy and Buxton, Reference Choy, Buxton, Farmar-Bowers, Higgins and Millar2013; Miralles-Garcia, Reference Miralles-Garcia2023; Spataru et al., Reference Spataru, Faggian and Docking2020; Tedesco et al., Reference Tedesco, Petit, Billen, Garnier and Personne2017). In Australia, a lack of integrated policies across jurisdictions such as land use, climate and water, economics, and other government areas was deemed ineffective in protecting land for farming use and negatively impacted the viability of UA (Carey et al., Reference Carey, Krumholz, Duignan, McConell, Browne, Burns and Lawrence2010; Choy and Buxton, Reference Choy, Buxton, Farmar-Bowers, Higgins and Millar2013). In the United States, municipal zoning and regulations dictated where farming could take place, what type of produce could be grown, and how it could be sold, sometimes requiring the involvement of licensed vendors (Pawlowski, Reference Pawlowski2018). Zoning policy seldom referenced UA and varied considerably across municipalities, leading to negative impacts on landscape preservation, land stewardship, resilience, and sustainable ecologies and in the longer-term undermining the viability of UA enterprises (Lawton and Morrison, Reference Lawton and Morrison2022; Pawlowski, Reference Pawlowski2018; Plant et al., Reference Plant, Walker, Rayburg, Gothe and Leung2012; Spataru et al., Reference Spataru, Faggian and Docking2020).

The policies of financial institutions and insurance companies determined whether UA enterprises could access financial tools such as loans, lines of credit, and insurance, and directly impacted their economic sustainability (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Ruiz-Menjivar and DeLong2022; Sabih and Baker, Reference Sabih and Baker2000; Spicka, Reference Spicka2020). Some UA enterprises had alternative organizational models and motivations that did not align with conventional metrics, making it difficult to secure financial support (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Ruiz-Menjivar and DeLong2022; Sabih and Baker, Reference Sabih and Baker2000; Spicka, Reference Spicka2020). For example, a study of micro-farmers in the Czech Republic found that young, single, less-educated farmers were more likely to take business risks, leading financial institutions to view them as high-risk clients (Spicka, Reference Spicka2020).

Leased land

Some farmers accessed affordable land in and around OECD cities by leasing it (DeLind, Reference DeLind2015; Oberholtzer et al., Reference Oberholtzer, Dimitri and Pressman2014; Pölling et al., Reference Pölling, Mergenthaler and Lorleberg2016; Rozanski and Gavin, Reference Rozanski and Gavin2023; Wästfelt and Zhang, Reference Wästfelt and Zhang2018). Rao et al. (Reference Rao, Patil, Singh, Roy, Pryor, Poonacha and Genes2022) argued that insecure tenure was less of a concern in wealthy nations than in developing nations due to ‘well-defined land governance and formal agreements between urban and peri-urban agriculture communities and municipalities, private landowners, and/or other organizations’ (Rao et al., Reference Rao, Patil, Singh, Roy, Pryor, Poonacha and Genes2022). However, a number of studies demonstrated that insecure tenure was an issue for urban farmers in OECD member countries (Oberholtzer et al., Reference Oberholtzer, Dimitri and Pressman2014; Pölling et al., Reference Pölling, Mergenthaler and Lorleberg2016; Wästfelt and Zhang, Reference Wästfelt and Zhang2018).

Procurement policies

Researchers reported that governments and institutions could help provide stable income for the UA sector in their region by mandating the purchase of food grown locally through procurement and food relief programs (Dunning et al., Reference Dunning, Day and Creamer2019; Guthman et al., Reference Guthman, Morris and Allen2006; Orlando et al., Reference Orlando, Spigarolo, Alali and Bocchi2019; Slámová et al., Reference Slámová, Kruse, Belčáková and Dreer2021). A study in Madrid claimed that local produce could meet 100% of the fruit demand of local institutions, around 35% of milk, 20% of vegetables, oil, pulse, and nuts, and around 12% of meat requirements, and that public procurement could be a ‘powerful instrument to support local food production’ (Slámová et al., Reference Slámová, Kruse, Belčáková and Dreer2021). However, influencing existing institutional supply chains can be challenging, as evidenced in the failure of a three-year initiative to increase the amount of local food from small-scale producers procured by a military base in North Carolina, USA (Dunning et al., Reference Dunning, Day and Creamer2019). Shifting the procurement practices of large, inflexible institutions such as the military requires policy support as well as organizational change, and as a first step, researchers suggested identifying champions and supporters to agitate from within the organization (Dunning et al., Reference Dunning, Day and Creamer2019; Orlando et al., Reference Orlando, Spigarolo, Alali and Bocchi2019).

Post-industrial cities

In some post-industrial cities, particularly in the United States, declining populations and greater land availability, combined with supportive government policies, spurred a revival of UA. Cities like Detroit, Philadelphia, St Louis, Baltimore, and Kansas City saw growth in UA initiatives (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2010; Gu et al., Reference Gu, Paul, Nixon and Duschack2012; Hunold et al., Reference Hunold, Sorunmu, Lindy, Spatari and Gurian2016; Pawlowski, Reference Pawlowski2018; Poulsen, Reference Poulsen2017). In Philadelphia, where manufacturing jobs dropped from 46% in the early 1950s to 5% in 2007, UA expanded following the first commercial urban farm in 1998. Municipal support included a Food Policy Advisory Council, a revised zoning code, legislation identifying UA as a priority for vacant land, and stormwater fee exemptions (Hunold et al., Reference Hunold, Sorunmu, Lindy, Spatari and Gurian2016). However, despite a robust UA sector, most urban farms remained unprofitable when labor costs were considered (Hunold et al., Reference Hunold, Sorunmu, Lindy, Spatari and Gurian2016).

Theme 5: Labor and livelihoods

Labor was highlighted as a challenge for the economic sustainability of urban farms in many studies. Issues related to the cost of labor, difficulties earning a livable wage in high-income countries, limited education and training opportunities, and difficulty accessing a skilled UA labor force.

Earning a livable wage

Earning a livable wage was reported as a challenge for many urban farmers (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Ruiz-Menjivar and DeLong2022; Jablonski et al., Reference Jablonski, Sullins and Dawn Thilmany2019; James, Reference James2015; Leger et al., Reference Leger, Léger and Morel2016; Samoggia et al., Reference Samoggia, Perazzolo, Kocsis and Del Prete2019; Stolhandske and Evans, Reference Stolhandske and Evans2016). With comparatively high wages in OECD member countries, and low food prices set by the industrial food system, researchers reported that if farmers included their own labor within their costs, even at a ‘minimum wage’ level, many businesses would make a loss, and therefore not be financially viable according to conventional business indicators (Conseil et al., Reference Conseil, Riviere, De Lapparent, Berry, Pellat, Leroy, Arnaud-Dupont, Icard, Hervouet, Herbeth and Sautereau2022; Hunold et al., Reference Hunold, Sorunmu, Lindy, Spatari and Gurian2016). There are, however, some exceptions (Kafle et al., Reference Kafle, Hopeward and Myers2022; Medici et al., Reference Medici, Canavari and Castellini2021; Morin, Reference Morin2009; Özden and Acar, Reference Özden and Acar2022). Consistent accounting frameworks were found to be lacking across the sector, with many enterprises omitting labor costs from their reporting methods, calling into question their underlying economic sustainability and raising some doubts about their real financial status (Kafle et al., Reference Kafle, Hopeward and Myers2022; Peña and Rovira-Val, Reference Peña and Rovira-Val2020). Work conditions and salary standards often did not meet conventional standards, and urban farmers in OECD countries often worked for free or underpaid themselves, worked long hours, and had unstable contracts with a lack of employee benefits, sometimes termed ‘self-exploitation’ (Biewener, Reference Biewener2015; Kafle et al., Reference Kafle, Hopeward and Myers2023; Lohest et al., Reference Lohest, Joris Van and Bauler2019; Savels et al., Reference Savels, Dessein, Lucantoni and Speelman2024; Stolhandske and Evans, Reference Stolhandske and Evans2016).

Many urban farms supplemented their labor requirements by utilizing unpaid labor in the form of volunteers and interns (Chang and Morel, Reference Chang and Morel2018; Gudzune, Welsh, Lane, Chissell, Anderson Steeves, and Gittelsohn, Reference Gudzune, Welsh, Lane, Chissell, Anderson Steeves and Gittelsohn2015; Savels et al., Reference Savels, Dessein, Lucantoni and Speelman2024; Stolhandske and Evans, Reference Stolhandske and Evans2016). In the context of Alternative Farming Initiatives (AFIs) being advocates for ‘fair food’ and ‘fair jobs’, Biewener (Reference Biewener2015) suggests that AFIs should remain aware of the tensions involved in utilizing free labor to maintain organizational viability, and they should work to ensure their community is not exploited.

Availability of skilled labor

Finding and keeping skilled labor was identified as a challenge that affected the financial sustainability of some enterprises (Diehl, Reference Diehl, Diehl and Kaur2022; Mussillon and Morel, Reference Mussillon and Morel2022; Samoggia et al., Reference Samoggia, Perazzolo, Kocsis and Del Prete2019; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Egli, Gaspers, Zech, Gastinger and Rommel2025). A study of farms in the Paris city-region identified a shortage of skilled labor, claiming ‘agriculture attracts few people’ (Mussillon and Morel, Reference Mussillon and Morel2022). This was attributed to the physically demanding nature of the work and low wages, which make it an unsustainable livelihood in the high-cost Paris region (Mussillon and Morel, Reference Mussillon and Morel2022).

Education, training, and capacity building

Researchers identified that education and training to build capacity among farmers and expand the cohort of skilled labor were required for the financial sustainability of the UA sector (Albrecht and Wiek, Reference Albrecht and Wiek2021; Diehl, Reference Diehl2020; Pennisi et al., Reference Pennisi, Magrefi, Michelon, Bazzocchi, Maia, Orsini, Sanyé-Mengual and Gianquinto2020). With many urban farms being small-scale operations that are distributed directly, farmers needed expertise in production, regulatory and governance frameworks, as well as business and marketing. Education in these areas could help improve farm efficiencies, reduce the risk of crop failure, and strengthen operational and logistical performance. A shortage of education programs and skilled labor in the communities was identified (Benessaiah, Reference Benessaiah2021; Diehl, Reference Diehl2020; Miralles-Garcia, Reference Miralles-Garcia2023; Mussillon and Morel, Reference Mussillon and Morel2022; Patel and MacRae, Reference Patel and MacRae2012), while training or mentorship contributed to successful outcomes (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Paul, Nixon and Duschack2012; Lamont, Reference Lamont2013; Sitaker, McCall, Kolodinsky, et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Belarmino, Wang, Kolodinsky, Becot, McGuirt, Ammerman, Pitts and Seguin-Fowler2020; Surls et al., Reference Surls, Bennaton, Feenstra, Lobo, Pires, Sowerwine, Kim and Wilen2023).

Strengthening UA training programs is, therefore, an area where viability could be increased. Some researchers proposed that education should be formalized, calling for governments to establish training programs, workshops, internships, high school programs, and subsidized labor programs (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Ruiz-Menjivar and DeLong2022; Kafle et al., Reference Kafle, Hopeward and Myers2022; Patel and MacRae, Reference Patel and MacRae2012; van der Gaast et al., Reference van der Gaast, Jansma and Wertheim-Heck2023; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Marquez, Deng, Iu, Fabella, Salonga, Ashardiono and Cartagena2022; Yurday et al., Reference Yurday, YaĞCi and İŞCan2021). Peer-to-peer networks also played an important role in the informal exchange of knowledge and technical advice, and urban farmers wanted more informal opportunities to connect with each other to share learnings and ideate solutions to common problems (Oberholtzer et al., Reference Oberholtzer, Dimitri and Pressman2014; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Egli, Gaspers, Zech, Gastinger and Rommel2025; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Kolodinsky, DeSisto and Conte2011; Sitaker, McCall, Kolodinsky, et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Belarmino, Wang, Kolodinsky, Becot, McGuirt, Ammerman, Pitts and Seguin-Fowler2020; Surls et al., Reference Surls, Bennaton, Feenstra, Lobo, Pires, Sowerwine, Kim and Wilen2023).

Theme 6: Short supply chains

Studies highlighted the importance of short supply chains in the economic sustainability and viability of soil-based UA in OECD countries. The role of CSAs, farmers’ markets, and direct sales to consumers or institutions in distributing locally grown, seasonal produce from UA enterprises, featured prominently (Atakan and Yercan, Reference Atakan and Yercan2021; Bertran-Vilà et al., Reference Bertran-Vilà, Ayari, Ayari and Jessica Geraldine Villatoro2022; Brulard et al., Reference Brulard, Cung and Catusse2017; Drottberger et al., Reference Drottberger, Melin and Lundgren2021; James, Reference James2015; Merino and Buratti, Reference Merino, Buratti, Hayden and Martin2025; Mundler and Jean-Gagnon, Reference Mundler and Jean-Gagnon2020; Pölling and Mergenthaler, Reference Pölling and Mergenthaler2017; Rosman et al., Reference Rosman, Macpherson, Arndt and Helming2024; Saleh et al., Reference Saleh, Hilletofth and Fobbe2025; Simón-Rojo et al., Reference Simón-Rojo, Couceiro, del Valle and Tojo2020; Sitaker et al., Reference Sitaker, McGuirt, Wang, Kolodinsky and Seguin2019; Zhu and Tsoulfas, Reference Zhu and Tsoulfas2024). These channels offered small-scale urban farmers an alternative to mainstream supply chains. Supermarkets typically require specific standards for price, quality, timing, quantity, and uniformity that small-scale urban farmers often cannot meet (James, Reference James2015; Milford et al., Reference Milford, Lien and Reed2021; Rosman et al., Reference Rosman, Macpherson, Arndt and Helming2024; Schmutz et al., Reference Schmutz, Kneafsey, Sarrouy Kay, Doernberg and Zasada2018). Short supply chains reduced the need for intermediaries, storage, and transportation, helping to lower costs while fostering mutual trust, community engagement, and social cohesion between producers and consumers (Medici et al., Reference Medici, Canavari and Castellini2021; Merino and Buratti, Reference Merino, Buratti, Hayden and Martin2025; Rosman et al., Reference Rosman, Macpherson, Arndt and Helming2024; Samoggia et al., Reference Samoggia, Perazzolo, Kocsis and Del Prete2019; Schmutz et al., Reference Schmutz, Kneafsey, Sarrouy Kay, Doernberg and Zasada2018; Sroka et al., Reference Sroka, Pölling and Mergenthaler2019; Zhu and Tsoulfas, Reference Zhu and Tsoulfas2024). Key success factors for local food supply chains included an effective marketing mix, strong customer engagement, clear market segmentation, access to resources, social capital, government support, and sound managerial practices (Saleh et al., Reference Saleh, Hilletofth and Fobbe2025).

Researchers proposed that direct or collaborative sales models such as CSAs, farmers’ markets, and farm gates were ‘contributing to a renaissance of niche agriculture by building relationships between customers and producers’ (Schutzbank and Riseman, Reference Schutzbank and Riseman2013). There was mixed reporting on the impact of direct distribution models on the economic sustainability of urban farms. Some studies reported that they offered tangible benefits such as higher income retention due to the omission of ‘middlemen’, allowing farmers to charge higher amounts (Lohest et al., Reference Lohest, Joris Van and Bauler2019) and receive a higher proportion of the sale price (Özden and Acar, Reference Özden and Acar2022). Dialogue at the point-of-sale allowed customers to communicate specific preferences or expectations regarding produce, in turn allowing farmers to understand and meet specific needs of their clientele, facilitating sales while fostering reciprocity, thereby contributing to economic sustainability (Mussillon and Morel, Reference Mussillon and Morel2022). Other studies reported that short supply chains demanded more logistics, sales knowledge, marketing expertise, and labor and could result in lower overall margins (Lohest et al., Reference Lohest, Joris Van and Bauler2019; McKee, Reference McKee2018; Mundler and Jean-Gagnon, Reference Mundler and Jean-Gagnon2020; Pölling and Mergenthaler, Reference Pölling and Mergenthaler2017). Some researchers found that direct distribution channels could increase resilience and provide livelihoods for farming households during times of economic distress (Delgado, Reference Delgado2017; Yoshida and Yagi, Reference Yoshida and Yagi2021; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Marquez, Deng, Iu, Fabella, Salonga, Ashardiono and Cartagena2022). In the ‘upper-middle’ income OECD setting of Mexico City, however, public infrastructure was limited, and the transportation of fresh produce from peri-urban farms into the city for sale presented a major challenge for direct distribution models (Merino and Buratti, Reference Merino, Buratti, Hayden and Martin2025).

Social networks associated with direct distribution channels provided benefits that were less tangible yet supported the viability of organizations, such as resource-sharing, skills exchange, and community support (Gudzune, Welsh, Lane, Chissell, Steeves, and Gittelsohn, Reference Gudzune, Welsh, Lane, Chissell, Steeves and Gittelsohn2015; Sitaker, McCall, Belarmino, et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Belarmino, Wang, Kolodinsky, Becot, McGuirt, Ammerman, Pitts and Seguin-Fowler2020). In a study of eight urban farms in Vancouver, ‘cash poor’ farmers bolstered their viability by limiting monetary transactions and ‘favoring trade, barter and other methods of payment’ (Schutzbank and Riseman, Reference Schutzbank and Riseman2013). Similarly, Leger et al. (Reference Leger, Léger and Morel2016) found farmers and their customers were anchored together by bonds built on conversations, equipment or labor exchange, trading resources such as manure, seeds and seedlings, participation in workshops, and involvement in local associations. These bonds were core to the farm economy and contributed to their success, demonstrating that ‘the viability of these alternative farms stands upon the access to intangible or material resources available in their social environment’ (Lèger and Morel, Reference Lèger and Morel2016). However, these transactions are typically not captured by standard accounting frameworks, suggesting that factors beyond conventional economic sustainability measures can contribute to the viability of UA enterprises.

Theme 7: Multifunctionality and social embeddedness

Many studies highlighted how ‘social embeddedness’ supported the viability of UA enterprises. Rooted in social networks, trust, and social capital (Hinrichs, Reference Hinrichs2000), this concept reflects how urban farmers often viewed their work as a holistic practice aimed at social, environmental, and economic transformation, alongside earning a living (Bertran-Vilà et al., Reference Bertran-Vilà, Ayari, Ayari and Jessica Geraldine Villatoro2022; Chang and Morel, Reference Chang and Morel2018; Clerino and Fargue-Lelièvre, Reference Clerino and Fargue-Lelièvre2020; Cohen and Reynolds, Reference Cohen and Reynolds2015; Diehl, Reference Diehl2020; Dimitri et al., Reference Dimitri, Oberholtzer and Pressman2016; Drottberger et al., Reference Drottberger, Melin and Lundgren2021; Galt et al., Reference Galt, O’Sullivan, Beckett and Hiner2012; John and Artmann, Reference John and Artmann2024; Spataru et al., Reference Spataru, Faggian and Docking2020). Farmers found purpose in participating in a ‘moral economy’ that aligned with their values (Bertran-Vilà et al., Reference Bertran-Vilà, Ayari, Ayari and Jessica Geraldine Villatoro2022; Jablonski et al., Reference Jablonski, Sullins and Dawn Thilmany2019; Sabih and Baker, Reference Sabih and Baker2000; Sitaker et al., Reference Sitaker, McGuirt, Wang, Kolodinsky and Seguin2019), and enjoyed intangible benefits such as living and raising children on a farm, connecting with the community, improving their property and surrounding ecologies, and eating and living healthily (Galt et al., Reference Galt, O’Sullivan, Beckett and Hiner2012; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Norrman and Berg2021). In France, micro-farmers were reported to value both the material (income, workload) and immaterial (quality-of-life, autonomy, meaning) aspects of their work, and they viewed their farms as a ‘life project’ where their personal welfare was a fundamental condition of their enterprise (Morel et al., Reference Morel, San Cristobal and Léger2018; Morel and Léger, Reference Morel and Léger2016).

Such intangible benefits and personal satisfactions may be considered factors that support the viability of urban farms even though they may not directly contribute to economic sustainability, as discussed in the ‘short supply chains’ section. Even so, UA organizations were expected to deliver a ‘trifecta’ of expectations, including good food, building skills and training, and income generation, often deemed unattainable (Daftary-Steel et al., Reference Daftary-Steel, Herrera and Porter2015). To counter this, Daftary-Steel et al. (Reference Daftary-Steel, Herrera and Porter2015) suggested UA organizations may need to compromise on their social goals at times in order to achieve economic sustainability and remain viable.

Some researchers argued that UA organizations choosing to provide non-market benefits, such as education, training, or the provision of fresh healthy food to low-income communities, should be subsidized by the state in the same way that public education institutions in many OECD countries are (Daftary-Steel et al., Reference Daftary-Steel, Herrera and Porter2015; Hunold et al., Reference Hunold, Sorunmu, Lindy, Spatari and Gurian2017). For such organizations, economic sustainability would therefore stem from external funding, as seen in the section on non-profit and social enterprises in the context of different organizational models below.

Relationships, trust, and transparency

A large number of studies reported that relationships built on trust, transparency, and reciprocity between producers, consumers, and other stakeholders were essential to the viability of UA enterprises (Atakan and Yercan, Reference Atakan and Yercan2021; Balázs et al., Reference Balázs, Pataki and Lazányi2016; Bloemmen et al., Reference Bloemmen, Bobulescu, Le and Vitari2015; Larsson, Reference Larsson2012; Medici et al., Reference Medici, Canavari and Castellini2021; Poulsen et al., Reference Poulsen, Spiker and Winch2014; Sitaker, McCall, Kolodinsky, et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Belarmino, Wang, Kolodinsky, Becot, McGuirt, Ammerman, Pitts and Seguin-Fowler2020). Such relationships built social capital to strengthen enterprises and their networks (Atakan and Yercan, Reference Atakan and Yercan2021; Bertran-Vilà et al., Reference Bertran-Vilà, Ayari, Ayari and Jessica Geraldine Villatoro2022; Genus et al., Reference Genus, Iskandarova and Brown2021; Kiminami et al., Reference Kiminami, Furuzawa and Kiminami2020; Larsson, Reference Larsson2012; Voltan, Reference Voltan2017). This concept aligns with corporate social responsibility principles where ‘businesses make their contribution to the community and, inversely, they depend on good health, stability and the prosperity of the communities that welcome them’ (Coscia and Russo, Reference Coscia, Russo, Bisello, Vettorato, Laconte and Costa2018). Social networks were utilized by farmers to access resources, and the availability, quality, and stability of this resource exchange could enable or disable their enterprise (Diehl, Reference Diehl2020). Researchers placed some of the onus on customers, espousing that they have a responsibility to make spending decisions that support their local producers (James, Reference James2015). While some studies found consumers would be willing to share the risk with farmers (Schmutz et al., Reference Schmutz, Kneafsey, Sarrouy Kay, Doernberg and Zasada2018), others found the opposite, particularly low-income households (Balázs et al., Reference Balázs, Pataki and Lazányi2016; Galt et al., Reference Galt, Bradley, Christensen, Kim and Lobo2016; Hinrichs, Reference Hinrichs2000). Several studies illuminated the importance of aligning the values and goals of urban farmers with stakeholders such as customers, local residents, Civil Society Organisations, funders, and government representatives, in order to maintain open and reflexive communication in which conflicts were navigated successfully (Cohen and Reynolds, Reference Cohen and Reynolds2015; Delgado, Reference Delgado2017; Mancini et al., Reference Mancini, Arfini, Antonioli and Guareschi2021; Poulsen et al., Reference Poulsen, Spiker and Winch2014; Sitaker, McCall, Belarmino, et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Belarmino, Wang, Kolodinsky, Becot, McGuirt, Ammerman, Pitts and Seguin-Fowler2020). As such, researchers recommended the development of tools for mediating potential disagreements to ensure the comfort of all stakeholders (Heuschkel et al., Reference Heuschkel, Hirsch, Terlau and Lorleberg2018). Additionally, farms located in urban residential areas needed buy-in from residents and neighborhood leaders, which required a community engagement process underpinned by transparency, trust, inclusiveness, and fairness (Poulsen, Reference Poulsen2017; Poulsen et al., Reference Poulsen, Spiker and Winch2014). However, while relationships were a key factor in the success of UA networks, farmers were often time-poor, and finding time to cultivate and maintain these relationships was deemed a challenge (Balázs et al., Reference Balázs, Pataki and Lazányi2016; Mundler and Jean-Gagnon, Reference Mundler and Jean-Gagnon2020; Sitaker, McCall, Kolodinsky, et al., Reference Sitaker, McCall, Belarmino, Wang, Kolodinsky, Becot, McGuirt, Ammerman, Pitts and Seguin-Fowler2020).

Conversely, distrust and lack of transparency among the community could be a hindrance to commercial farms (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2010; Poulsen et al., Reference Poulsen, Spiker and Winch2014). In Detroit, where a dynamic and widespread ‘bottom up’ patchwork of community-based edible farms had emerged, proposals for larger-scale commercial UA operations were met with community distrust (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2010).

Theme 8: Alternative organizational models

Many urban farming enterprises forged alternative organizational models built on social entrepreneurship that subverted market-base (economic) indicators of success (Kiminami et al., Reference Kiminami, Furuzawa and Kiminami2020), yet still appeared to achieve viability. These models were either formal or informal in nature, and included social enterprises, non-profits, public-private partnerships, food hubs/cooperatives, buyers groups, CSAs, and cost-offset CSAs (CO-CSA) (Appolloni et al., Reference Appolloni, Pennisi, Tonini, Marcelis, Kusuma, Liu, Balseca, Jijakli, Orsini and Monzini2022; Biewener, Reference Biewener2015; Bloemmen et al., Reference Bloemmen, Bobulescu, Le and Vitari2015; Brislen et al., Reference Brislen, Barham and Feldstein2017; Dedeurwaerdere et al., Reference Dedeurwaerdere, De Schutter, Hudon, Mathijs, Annaert, Avermaete, Bleeckx, de Callataÿ, De Snijder, Fernández-Wulff, Joachain and Vivero2017; Dimitri et al., Reference Dimitri, Oberholtzer and Pressman2016; Drottberger et al., Reference Drottberger, Melin and Lundgren2021; Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2010; Genus et al., Reference Genus, Iskandarova and Brown2021; Poulsen, Reference Poulsen2017).

Enterprises often had unique structures that evolved in response to contextual factors such as farmer motivations, available assets and equipment, skills and experience, customer preferences, and broader social, political, and environmental influences (Atakan and Yercan, Reference Atakan and Yercan2021; Mundler and Jean-Gagnon, Reference Mundler and Jean-Gagnon2020; Paül and McKenzie, Reference Paül and McKenzie2013; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Egli, Gaspers, Zech, Gastinger and Rommel2025). Researchers argued that classical agro-economic criteria could not adequately assess the viability of these organizations, and that new conceptual frameworks incorporating their non-pecuniary aspirations were required (Biewener, Reference Biewener2015; Brozovic, Reference Brozovic2020; Morel and Léger, Reference Morel and Léger2016). Biewener (Reference Biewener2015) proposed that AFIs sat outside the industrial food system. AFIs prioritized ‘food justice’, ‘fair food’, and ‘fair jobs,’ and were often considered a form of activism that challenged neoliberal, free-market practices and subjectivities (Biewener, Reference Biewener2015). AFIs were often sustained in ways outside conventional business metrics, including through grants, donations, non-financial ‘share economy’ transactions, and unpaid work in the form of volunteers and internships (Appolloni et al., Reference Appolloni, Pennisi, Tonini, Marcelis, Kusuma, Liu, Balseca, Jijakli, Orsini and Monzini2022; Biewener, Reference Biewener2015).

Non-profits and social enterprises

Social enterprises and non-profits often achieve viability by supplementing their income with public and private funding such as grants, subsidies, and donations (Dimitri et al., Reference Dimitri, Oberholtzer and Pressman2016; Tulla et al., Reference Tulla, Vera, Valldeperas and Guirado2018; Weissman, Reference Weissman2015). While they have a commercial component, typically providing employment and selling produce, social enterprises and non-profits have overt social goals, with profits directed back into the enterprise rather than to owners or shareholders. Researchers reported that these models ‘shifted the challenge of viability from finding markets and selling output to one of scrambling for donations and grants’ (Dimitri et al., Reference Dimitri, Oberholtzer and Pressman2016). In Catalonia, some conventional farms struggling to maintain economic sustainability transitioned to non-profit or social enterprises (Tulla et al., Reference Tulla, Vera, Valldeperas and Guirado2018). Organizational viability was found by supplementing their income from produce sales with public and private funding that supported their social agendas (Tulla et al., Reference Tulla, Vera, Valldeperas and Guirado2018).

Food hubs and cooperatives

Many urban farms were small in scale and experienced challenges at all stages of the production and distribution process. A study of 199 farms in Ruhr, Germany, found that larger farms were more likely to achieve economic sustainability through the size of their operations, whereas smaller farms were likely to utilize ‘adjustment factors’ such as tourism or direct selling to overcome their small scale (Sroka et al., Reference Sroka, Pölling and Mergenthaler2019). Small farms were often precluded from accessing mainstream storage, delivery, and distribution services due to their scale (Bertran-Vilà et al., Reference Bertran-Vilà, Ayari, Ayari and Jessica Geraldine Villatoro2022; James, Reference James2015; Zhu and Tsoulfas, Reference Zhu and Tsoulfas2024). Food hubs or cooperatives could provide a bridge between larger-scale supply chains and small-scale producers, and they allowed farmers to access markets, equipment, infrastructure, cheaper supplies and insurance, certifications, and logistical support that would otherwise not be available to them (Brislen et al., Reference Brislen, Barham and Feldstein2017; Carvalho, Reference Carvalho, Jean-Vasile and Popescu2015; Felicetti, Reference Felicetti2014; Gonzales et al., Reference Gonzales, Forrest and Balos2013; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Kolodinsky, DeSisto and Conte2011; Stone et al., Reference Stone, Thompson, Zimmerman, Brighenti and Liebman2024).