Education is thought to be an essential tool for building a sense of nationhood, trust, and tolerance in ethnically diverse states (Weber Reference Weber1976; Gellner Reference Gellner2023; Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm1992; King Reference King2014). By bringing learners together from diverse corners of multi-ethnic countries, schools can foster a sense of ‘civic nationalism’ and build national cohesion (Weber Reference Weber1976). As venues that facilitate repeated contact with diverse others in pursuit of a common goal, schools could reduce outgroup prejudice – potentially contributing to trust and tolerance (Pettigrew Reference Pettigrew1998; Pettigrew et al. Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006; Paluck and Green Reference Paluck and Green2009; Paluck et al. Reference Paluck, Green and Green2018; Allport Reference Allport, Clark and Pettigrew1954). School socialization can also foster civic attachment and state legitimacy (Koesel Reference Koesel, Lynch and Rosen2024; Yanarocak, Reference Yanarocak2022), which could elevate citizen-level identities above more localized attachments such as regional or ethnic identity (King Reference King2014) and potentially build greater social trust and tolerance of other citizens.Footnote 1 Finally, schools also offer opportunities to create deeper connections such that some classmates become friends. Friendship – or deep bonds of solidarity, reciprocity, and understanding – with dissimilar peers could also be a potential pathway to build trust and tolerance towards outgroups as well as a civic national identity.

Building national cohesion is particularly important in post-conflict societies and/or places where subnational identities outweigh civic nationalism. Yet, to date, there has been little empirical evaluation of nation-building efforts in schools on nation-state identity, trust, and tolerance in post-conflict settings – including many states in sub-Saharan Africa where ethnic identity remains extremely salient for politics.Footnote 2 This is striking given that there has been a dramatic expansion of schooling across the continent in the last thirty years. In some countries, for example Kenya and Tanzania, governments have made specific policy efforts to build national unity through education provision (Prewitt et al. Reference Prewitt, Von der Muhll and Court1970; Barnes Reference Barnes1982; Robinson Reference Robinson2014). One of the ways that the Kenyan government attempts to build unity is by increasing student body diversity. In 2011 the Kenyan government expanded the number of national schools from 18 to 103; these schools require students to come from different counties across Kenya to learn together in an explicit attempt to build national unity in the wake of inter-ethnic tension and ethnic violence.Footnote 3 The Kenyan policy to create diversity quotas is similar to other integration initiatives in countries such as the United States, Brazil, India, South Africa, and Belgium that have sought to put learners from different racial, linguistic, or ethnic groups in classrooms together (Danhier and Friant Reference Danhier and Friant2019; Mickelson et al. Reference Mickelson and Nkomo2012).

This paper evaluates the effect of attending a ‘new national school’, a school with diversity quotas, on trust, tolerance, and a sense of civic national identity in a post-conflict context where ethnic identity remains extremely salient for politics.Footnote 4 Our design leverages the policy change related to student placement, which is exogenous to parent or school preferences, as well as an expert matching exercise to compare students in secondary schools that differ in their use of a diversity quota, but are similar in most other characteristics. We draw on an original survey of 984 Form 4 (grade 12) students in 5 Kenyan counties with histories of ethnic conflicts and compare students in ten newly established national schools and ten similar schools without diversity quotas. How does attending a more diverse school affect how students prioritize national identity relative to subnational identities? How do experiences in more ethnically diverse schools affect the degree to which students are trustful and tolerant of each other?

We confirm that, consistent with the policy, students in schools with diversity quotas educate students from more Kenyan counties and ethnic groups than comparable extra-county and county schools. We find that students in national schools are more likely to prioritize national identity over ethnic or local identity. However, we find that attending a national school has no direct effect on trust and tolerance, implying that contact with diverse classmates is insufficient to generate trust and tolerance. Instead, we observe that inter-ethnic friendship is an important mediating factor connecting national school attendance to improved trust and tolerance. National school students have more friends from different ethnic groups than students in comparison schools. Inter-ethnic friendship is associated with heightened tolerance and trust measures.

Our paper makes significant contributions to literature on nation-building, contact theory, and schooling in post-conflict contexts. First, our research focuses on questions about schooling policy as a tool to build national cohesion. To date, most existing political science analysis on the impact of expanding school enrollments on the continent has focused primarily on the impact of formal schooling on political participation and knowledge (Larreguy & Marshall, Reference Larreguy and Marshall2017; Croke et al. Reference Croke, Grossman, Larreguy and Marshall2016; Bleck Reference Bleck2015), the role of civic education in shaping participation, knowledge, and civic norms (Finkel and Lim Reference Finkel and Lim2021; Gottlieb Reference Gottlieb2016; Finkel and Smith Reference Finkel and Smith2011; Finkel et al. Reference Finkel, Horowitz and Rojo-Mendoza2012), the degree to which politicians’ ethnicity affects access to schooling (Kramon and Posner Reference Kramon and Posner2016; Simson and Green Reference Simson and Green2020), and students’ attitudes about the political environment and patterns of participation (King Reference King2018; Gilchrist et al. Reference Gilchrist, Edgell and Elischer2022). Literature has not explored the role of schools in generating contact or friendship between diverse students as a way to build civic nationalism. This is puzzling given the salience of subnational identities in Africa, which have often presented obstacles to national cohesion in the form of military coups and electoral violence (Straus Reference Straus2015; Harkness Reference Harkness2016). Our article demonstrates how education policy can generate students who prioritize national identity – even in a post-conflict context where ethnic identities remain very salient.

Second, our study contributes to a growing body of work that utilizes experimental or quasi-experimental methods to estimate the causal effects of contact with outgroup members (Paluck et al. Reference Paluck, Green and Green2018; Mo and Conn Reference Mo and Conn2018; Rao Reference Rao2019; Corno Reference Corno, Ferrara and Burns2022; Okungbe Reference Okunogbe2024; Mousa Reference Mousa2020). Our mixed methods research design – based on expert matching of similar schools as well as interviews with education officials and teachers – enables us to evaluate a real-world schooling policy and to highlight an additional mechanism through which schools can foster unity: friendship. Schools introduce a range of potential mechanisms that might foster trust, tolerance, and national identity: socialization that endorses this civic orientation, but also exposure to diverse others in a collaborative environment which may enable diverse friendships. Our survey design, by collecting information on friend characteristics, allows us to better isolate the role of intergroup contact and friendship. We find evidence that outgroup friendship is correlated with important outcomes in this context: trust and tolerance. While attending a national school can foster national identity, it is insufficient to affect trust and tolerance of outgroups. However, when schools can create an enabling environment for students to make diverse friendships, those friendships can increase outgroup trust and tolerance. Our findings suggest that contact alone may be insufficient to generate pro-social outcomes and that emotional connections and solidarity in the form of friendship may be important to generate trust and tolerance. It suggests that research should further explore the role of friendship distinct from ‘contact’ with diverse others in terms of its ability to build social cohesion, social capital, trust, and tolerance.

Finally, the study brings important new data on an understudied population: Kenyan secondary students. Young people are central players in African politics, but too often their experiences and perspectives are not studied (King Reference King2018).Footnote 5 The research offers us unique insight into students’ experiences in new national schools. Drawing on a sample of learners from ten such schools as well as ten similar schools across a diverse set of counties that have all experienced various forms of electoral conflict, the study sheds light on a deliberate government policy to forge civic nationalism in post-conflict contexts. The findings from Kenya can inform student experience in other diverse, conflict-affected environments where the government is using school to forge national cohesion.

Theory

Throughout history, governments have viewed schools as important tools to heighten a sense of civic nationalism, build allegiance to the state, build national cohesion, and socialize citizens into political communities (Almond and Verba Reference Almond and Verba1963; Weber Reference Weber1976; Gellner Reference Gellner2023; Koesel Reference Koesel, Lynch and Rosen2024; Alesina et al. Reference Alesina, Giuliano and Reich2021). Many states have used schools as environments to build patriotic orientation (Wang Reference Wang2008), support of the regime (Koesel Reference Koesel2020), national cohesion, norms of democratic engagement or political behaviors,Footnote 6 or civic virtue (Stevick and Levinson Reference Stevick and Levinson2007; Curren and Dorn Reference Curren and Dorn2018), but also to control and discipline behavior (Paglayan Reference Paglayan2024). Receiving a high-quality service from the state could also build loyalty and allegiance through a type of policy feedback mechanism, where citizens feel more motivated and engaged after receiving a positive welfare service (Mettler Reference Mettler2007; Cammet and MacLean Reference Cammett and MacLean2011).

Schools have a particularly important role to play in post-conflict societies, where important work remains to encourage students to see themselves as part of a broader civil society (Chambers and Kopstein Reference Chambers and Kopstein2001). By bringing diverse learners together, creating opportunities for friendship, which represents a more intimate, emotional connection between learners, and socializing students into a civic nationalism, schools could potentially affect outcomes such as learner identity as well as trust and tolerance of other citizens. Schools can bring students from diverse family, ethnic, religious, and socio-economic backgrounds together in the same classroom. They can instill norms of collaboration, trust, and co-operation and foster allegiance to a country-level identity. They also offer opportunities to bond with other classmates and potentially build friendships that transcend mere repeated and sustained contact, leading to deeper emotional connections and solidarity (Putnam Reference Putnam2000).

This paper explores two specific mechanisms that are linked to diversifying student bodies: contact theory and mechanisms linked to friendship. Schools with diverse populations are ideal venues to explore the role of ‘contact’ in national cohesion. Theorists argue that intergroup interactions can be positive for outgroup trust and tolerance when the following key conditions are met: equal status, common goals, the absence of intergroup competition, and a sanctioning authority (Allport et al. Reference Allport, Clark and Pettigrew1954).Footnote 7 Schooling – particularly at boarding schools – is interesting because of the ‘intensity’ of exposure to classmates, the existence of sanctioning authority (teachers and the principal) that could support a unity narrative or pro-social norms, and the fact that learners in the classroom should have equal status (be treated fairly by teachers).Footnote 8 Inside the school, students interact as peers and pursue common goals when they work and learn together as teams or on classroom projects. Teachers serve as the sanctioning authority in the school environment and can reinforce norms of co-operation and solidarity. Thus, schooling can build intergroup trust and tolerance by facilitating positive relationships for those in the school community (Juvonen et al. Reference Juvonen, Nishina and Graham2006; Rao Reference Rao2019). This may lead students to prioritize a sense of ‘civic’ nationalism over other subnational identities such as ethnicity.

Evidence from studies on the impact of exposure to diverse others at schoolFootnote 9 on trust, tolerance, and social cohesion has been mixed. In a variety of educational contexts around the world, integration and exposure to diversity (ethnic, socio-economic, and/or religious) has been associated with heightened outgroup trust (Dinesen Reference Dinesen2011), empathy (Boisjoly et al. Reference Boisjoly, Duncan, Kremer, Levy and Eccles2006), tolerance (Janmaat Reference Janmaat2010), lower levels of anxiety about outgroup interaction, higher valuation of diversity (Gaither and Sommers Reference Gaither and Sommers2013), and more prosocial behavior (Rao Reference Rao2019). In other cases, studies have found null or negative effects of student body diversity on outgroup trust or tolerance (Janmaat Reference Janmaat2010; Kokkonen et al. Reference Kokkonen, Esaiasson and Gilljam2010). Some variables, including school environment, are important for diversity in schools to generate greater inter-ethnic tolerance (Thijs and Verkuyten Reference Thijs and Verkuyten2013).

Friendship within diverse schools is another potential mechanism for building trust and tolerance among diverse populations (Putnam Reference Putnam2000; Pettigrew Reference Pettigrew1998). We can think of friendship as emotional contact and solidarity among students, as distinct from contact with colleagues as peers. Some scholars demonstrate that these effects can translate to broader groups of outgroup members (outside of immediate contact) (Pettigrew et al. Reference Pettigrew, Tropp, Wagner and Christ2011). In schools, greater student body diversity has been shown to be positively correlated with interaction among students from different backgrounds (Pike and Kuh Reference Pike and Kuh2005). Intergroup friendships are promoted in environments that enable cross-group interaction and interdependence, equality of status, and explicit support for intergroup mixing by the authorities; in the school setting, this can manifest in integrated extracurricular activities and learning in the same classrooms (for example, an absence of segregated tracks) (Moody Reference Moody2001). As students ‘bond’ with diverse peers, they develop emotional connections that surpass contact as colleagues. By heightening diversity in the student body, school administrators could increase the probability that students interact with outgroup members. Friendship is thought to play a role in building social cohesion by reducing anxiety and increasing empathy during intergroup contact (Schroeder and Risen Reference Schroeder and Risen2016). Thus, school friendship is another potentially powerful mechanism for fostering trust and tolerance. However, contact does not always result in friendship – it is something that must be empirically tested. For instance, studies in the United States have found that increasing diversity does not necessarily generate intergroup friendships and can create friendship segregation – especially if schools have a diverse population but remain ‘internally divided’ without significant contact between groups or there is insufficient multicultural curriculum (Moody Reference Moody2001; Banks Reference Banks2008). It is also important to note that student body diversity alone might be insufficient to create intergroup friendship. Student-level variables may lead students to form friendships, and these factors may also relate to desired outcomes like trust and tolerance.

Education, Diversity, and Citizenship in Kenya

The Kenyan context allows us to explore the effects of an explicit government effort to foster social cohesion. Kenya is an ethnically diverse state and, like many states with a relatively recent colonial past, has struggled to foster national unity among its citizens. Politics in Kenya remains tethered to ethnic lines. In a survey of almost 1,000 students at the University of Nairobi campus, Edgell et al. (Reference Gilchrist, Edgell and Elischer2022) find that while young Kenyans aspire to move past ethnic politics, their political perceptions remain filtered by ethnicity. Even when some studies have found evidence that the political salience of ethnic identity has been on the decline in Kenya (Berge et al. Reference Berge, Bjorvatn, Galle, Miguel, Posner, Tungodden and Zhang2015), there is reason to think that recent electoral violence looms large in the experience of many Kenyans and may affect the way people of different ethnic groups view each other. Robinson reports that Kenya has among the highest ethnic fractionalization rates of countries within the Afrobarometer (2016). In 2019, only 20.1 per cent of Afrobarometer respondents stated that they trusted other ethnic groups a lot; this percentage dropped to 13.6 for the same question in 2021, slightly lower than reported trust of other people they know (14.3 per cent) or other citizens (17.7 per cent) in the same year.Footnote 10 The percentage of Kenyans stating that they felt more Kenyan than their ethnic group dropped from around 50–55 per cent in the years 2011–18, to around 35 per cent in 2019–21.Footnote 11

While inter-ethnic rivalries for access to political power and economic opportunities have been a feature of Kenya’s politics since independence, such rivalries did not become violent in a significant way until the reintroduction of multiparty elections in the early 1990s (Kasara Reference Kasara2013; Cheeseman et al. Reference Cheeseman, Kanyinga, Lynch, Ruteere and Willis2019). Following a heavily contested general election in 2007, a number of major cities flared into post-election violence, namely Nairobi, Naivasha, Mombasa, and Kisumu, as well as other smaller towns. This politically initiated violence led to the deaths of approximately 1,000 people and displaced more than 600,000 (Adeagbo and Iyi Reference Adeagbo and Iyi2011). Following this, the country established constitutional bodies such as the Commission of Inquiry into Post-Election Violence, the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC), and the National Commission on Integration and Cohesion (NCIC). These commissions aimed at promoting tolerance, human rights, and cohesion. The country also embarked on a series of national campaigns such as Najivunia Kuwa Mkenya (‘I’m proud to be a Kenyan’ in Swahili) that were aimed at promoting trust, tolerance, and a national identity.

Kenyan Education Policy

At independence in 1964, the Kenyan government transformed the privileged ‘white schools’ into ‘national schools’, which were designed to bring together the country’s brightest students (Alwy and Schech Reference Alwy and Schech2004). In addition to the production of human capital to foster Kenya’s development, the Ministry of Education conceptualized students living and learning together in pursuit of their education as a way to foster pan-ethnic trust, tolerance, and patriotism (Anderson Reference Anderson1965). Still, in the decades that followed independence, only a small population of Kenyan students could attend the limited number of national schools, which were considered elite. There were only 18 such highly ranked schools compared to nearly 3,000 other secondary schools categorized as either extra-county (next privileged), county, and subcounty (lowest classification). Alwy and Schech (Reference Alwy and Schech2004) note that the national school system perpetuated a system of social stratification which was in place during colonial times.

In the wake of the 2007 post-election violence and constitutional reform, the government decided to expand the national schools from the original 18 schools to 103 in 2011; in doing so, some former provincial schools (renamed extra-county) were upgraded to national school status. As these schools became national schools, they became subject to a diversity quota. This policy created centralized placement procedures that elevated two schools (one girls’ and one boys’ school) in each county to national school status. New national schoolsFootnote 12 were required to receive students from other regions of the country as assigned by the Ministry of Education. Due to the condition of only one boys’ and one girls’ school being elevated in each county, this policy left similar county and extra-county schools without the same national diversity quota. We leverage these diversity quotas to explore the effect of student body diversity on trust, tolerance, and national identity among secondary school students in Kenya, as compared to the experience in otherwise similar high-quality schools.

Research suggests that Kenyan schools are salient venues for political socialization; studies have shown that Kenya’s civics curriculum contributed to heightened democratic norms, knowledge, peaceful behavior, and reconciliation (Finkel and Smith Reference Finkel and Smith2011; Finkel et al. Reference Finkel, Horowitz and Rojo-Mendoza2012; Omundi and Okendo Reference Omundi and Ogoti Okendo2018). These studies focus on two phases of the ‘Kenya National Civic Education Programme’, a large-scale civic education effort implemented by civil society organizations and respondents’ exposure to sensitization activities.

While there is strong salience and politicization of ethnic identities in Kenya, secondary schools could potentially foster high rates of intergroup friendship for a few reasons. First, all schools in the study are boarding schools. Since students live together in cloistered campuses, this assures us that sustained intergroup contact actually takes place. We can be confident that students engage in regular face-to-face interactions as they learn and live together. Second, because this is a top-down government initiative and there has been substantial Ministry of Education emphasis on the role of schooling in generating a more united Kenya, we expect the school authorities to buy into the importance of positive intergroup interaction. Lastly, existing work by Kasara (Reference Kasara2013) demonstrates that Kenyans living in more ethnically diverse areas report higher levels of inter-ethnic trust as compared to those in more segregated areas. Given the government’s commitment to building greater social cohesion through education, the existing literature on contact theory and diversity in schools, and Kasara’s (2013) work on intergroup contact in the Kenyan case, we anticipate that increases in student body ethnic diversity have the potential to impact trust, tolerance, and national identity in the Kenyan context.

We test the following hypotheses that look at the direct effect of attending a new national school as well as the mediating role of friendship with diverse others:

H1a: Students in new national schools will be more trusting of outgroup members.

H1b: Students in new national schools will be more tolerant of outgroup members.

H1c: Students in new national schools will exhibit higher prioritization of Kenyan identity over ethnic identity than students in comparable schools.

H2: Students in new national schools will be more likely to engage in friendships with students from other ethnic groups than students in county/extra-county schools.

H3a: Outgroup friendships will serve as the mediating factor by which students in national schools have higher levels of tolerance.

H3b: Outgroup friendships will serve as the mediating factor by which students in national schools have higher levels of trust towards outgroup members.

H3c: Outgroup friendships will serve as the mediating factor by which students in national schools will exhibit higher prioritization of Kenyan identity over ethnic identity than students in comparable schools.

Research Design: The Impact of Attending a National School on Trust, Tolerance, and National Identity

School Selection

Our research design compares trust, tolerance, and prioritization of national identity over ethnic identity among Form 4 students (seniors) in more diverse national schools and in matched schools. Our quasi-experimental design utilizes (a) the National School Upgrading Programme in Kenya that elevated former county and extra-county schools to national school status and (b) expert advice to find pairs of national and non-national schools that are as similar as possible to compare groups of students.Footnote 13 We create our sample at three levels: county, school, and student. First, we identify five counties that are broadly representative of Kenya’s ‘ecosystems’ (agriculturally productive highlands with high population density, versus rural arid/semi-arid areas with low economic productivity and sparse population). These counties vary in their degree of ethnic diversity but have all been flashpoints for ethnically driven political violence. Our selection of counties for sampling is as follows: Homa Bay, Kericho, Tana River, Marsabit, and Trans-Nzoia (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of Kenya’s counties, with sampled counties highlighted.

As described above, a centralized placement policy allows us to compare students at schools that are similar in most characteristics, except their acceptance of students from all over the nation. Five top-scoring students from each subcounty automatically get admission to national schools. In practice this means that student body composition in national schools is largely governed by factors other than students’ and parents’ preference for specific schools. Many students typically list top-ranking schools first – meaning that requests for these schools may be 100 times more than the number of available slots; in practice, very few students get their top choice. Wait lists for the ‘original’ national schools have included over 15,000 students (Ouka Reference Ouka2018). Students’ and parents’ preferences for national schools are primarily motivated by the academic ranking of these schools rather than the consideration of the type of school.Footnote 14 In those schools, there are very few slots available outside of those assigned by the government.Footnote 15 Additionally, we explore students’ reasons for accepting their assignment in the new national schools and find very limited evidence of selection effects related to preferences for greater diversity as driving schooling enrollment.Footnote 16

This policy allows us to compare students in new national schools to students in county or extra-county schools that have many of the same characteristics as the national schools (student bodies with nearly the same mean entrance exam scores, boarding facilities, and material resources). To be eligible to become a national school, schools needed to meet certain basic infrastructure requirements – for example, they had to be able to accommodate three streams, or classrooms of students, in each cohort. Only two schools in each county received this new status – one boys’ and one girls’ school. There were typically more than two schools in the county that met the qualifications.Footnote 17 These other eligible schools (county and extra-county schools) serve as our comparison schools, because they are presumably similar to the new national schools in most ways except for the independent variable of interest – ethnic diversity of the student body.

After selecting counties to include in the study, we engaged in an expert school selection exercise with county-level directors of education to identify pairs of national schools and very similar county and extra-county schools. We conducted school-level surveys to verify this similarity along key covariates. This school-level survey was further verified during data collection with an enumerator observation sheet and a school-level questionnaire. From the short list of potential matches, we selected two schools in each county (one boys’ school and one girls’ school) to serve as the matched comparison schools. These schools were selected based on the following criteria, which were decided in consultation with Kenyan education experts and theorized to relate to the student experience in the school. Only single-sex boarding schools founded twenty or more years ago were selected as comparison schools. In the counties where there were several schools identified by the experts that met these criteria, we selected the nearest match with the county’s national school in terms of fees and entrance exam scores. This process enabled us to select comparison schools for all the ten new national schools included in our sample. The research team then conducted school-level observations and surveys to confirm the similarity of treatment and comparison schools. During a second trip, they proceeded with a survey of fifty Form 4 learners in each school. In the next section we describe sampling procedures as well as how we check for balance on covariates at the school and student level.Footnote 18

Addressing selection effects

In order to ensure that there are not consistent differences between students in national schools and other school types, we compare the students based on variables such as probability above or below the Kenyan National Poverty Line based on an assets index, average age of the students surveyed, and student score on the national secondary school entrance exam.Footnote 19 We also focus our balance tests of student data on two important characteristics related to our outcomes of interest – exposure to diversity outside of the school and school choice.Footnote 20

We find no differences between the student profiles at new national schools and comparison schools. Students in these schools are comparable in terms of age, socio-economic status, and school exam scores.Footnote 21 They are also comparable to each other in previous or at-home exposure to diversity, geographic mobility, and how they came to attend the school they are currently enrolled in. We also find balance in the likelihood that students attended the school they were assigned to by the Ministry. The only statistically significant difference we observe is that students at national schools are more likely to list ‘wanted to attend a national school’ as the reason for their enrollment in the school (Table A1 in Supplementary Material).Footnote 22

Measurement and Operationalization

School-Level Measures

We collected a series of school-level data from three sources. First, we collected information from the county office of education on each potential school in the sample. Variables in this dataset include year of founding, boarding status (board, day, or mixed), single-sex or mixed school, fees charged, and average student entrance exam scores. We used these variables to create eligibility criteria for comparison schools and resolve instances where there were several potential matches for the new national schools. Second, we completed a survey with a school official on the counties of origin of the student body while visiting the school to schedule data collection and drop off parental consent forms. This allowed us to confirm our key variable (diversity) before launching data collection. Third, we conducted a school observation exercise and principal survey, where enumerators observed the school facilities and infrastructure such as classrooms, computers, science labs, study rooms, dormitories, bathrooms, cafeterias, student health facilities, and additional student support such as athletic, extracurricular clubs, and guidance counselors.

We use data from the school observation exercise and the principal survey to confirm balance on covariates between each pair of schools. Schools also share the same curriculum, which is mandated at the national level, so we know that this particular mechanism of socialization is not driving results. This gives us confidence that the main characteristic that differs between schools is the diversity of the student body rather than some other variable.

Student Survey: Student-Level Dependent Variables

Working with the school principal and a designated teacher in each school, we invited all Form 4 students in these schools to participate in the survey. All students 18 and older who provided consent, and those students who were under 18 who had parental consent and provided assent, were eligible to participate in the study. Enumerators randomly selected from that pool of students with the aim of sampling fifty students per school.

Sampled students completed surveys that captured their attitudes, behaviors, school experiences, and school preferences. Our outcomes of interest include trust, tolerance, and national identity. We compare the responses of students who attend new national schools to those who are in comparison schools to learn if there are significant differences across these groups.

We use self-reported attitudes and behaviors to assess two of our dependent variables: trust and tolerance. To measure trust, we used standard Afrobarometer measures about how much students trust members of their own ethnic group and how much they trust members of other ethnic groups. We also asked behavioral questions such as how often respondents had lent money or possessions to others in the last year. To measure tolerance, we asked students about their own willingness to marry members of a different ethnic group.Footnote 23 For national identity, we asked students to rank various identities by their level of importance: African, national, religious, ethnic, and county.Footnote 24

The independent variable is enrollment in a national school. As discussed above, outgroup friendship is viewed as a key mediating factor for correlation with higher trust and tolerance. We anticipate that ethnic diversity in schools generates trust, tolerance, and higher prioritization of national identity over ethnic identity by fostering outgroup friendships (since students have a more ethnically diverse pool of friends to choose from). We measure the demographics of students’ friends by asking them to list their four best friends, and then inquiring about each friend’s ethnic group, favorite subject in school, religion, and whether the friend was made in the school or not. From this information we construct an outgroup friend index indicating the proportion of the student’s friends who are outgroup members in terms of ethnicity. Since students have already been exposed to three years of boarding in new national schools, we are fairly confident that these friendships are tied to the national school setting.

We include a list of individual-level covariates that might affect trust, tolerance, and national identity as measured in our dependent variables. We control for student gender, since we anticipate greater hurdles for outgroup marriage for women. We also control for exposure to outgroup members in other venues. While students live on the school grounds, their past experiences might have been sources of other exposure to intergroup contact and friendships. It’s possible, although unlikely, that students choose to enroll in national schools because of some preference to be in a more diverse school environment, or due to comfort with living in another place. We ask questions as proxies for previous exposure to diversity such as ‘At home, do any of your neighbors speak another mother tongue/practice another religion?’ or if the students lived or attended primary school in a different county than the one where their parents live now.

We also include ethnic controls as we anticipate that different ethnic identities will affect how students interact with in- or outgroup members, due to norms or traditions of various ethnic groups. Lastly, previous studies have found that increases in diversity are associated with different effects for majority and minority group members (Gross and Maor Reference Gross and Maor2020; Dinesen Reference Dinesen2011). It is important to think about the size of individuals’ ethnic group’s percentage of the overall student body. Increasing diversity is more likely to foster outgroup interactions among majority members as minority group members are already likely to have to interact with their respective outgroups. Therefore, we also controlled for whether the student is a member of a dominant group, defined as the most common ethnic group in the school.

Understanding the Treatment: National Schools as Facilitating Diverse Contact and Friendship

Before analyzing the differences between students’ trust, tolerance, and national identities in national and comparison schools, we establish that national schools are, in fact, more diverse than other school types. We determine student body ethnic diversity by examining the county of origin of the students surveyed. This is in line with the quota requirement as well as other research on the Kenyan national school system, which uses county of origin as a proxy for ethnic diversity (Ouka Reference Ouka2018). Since students were selected randomly to be included in the survey and weighted at the school level to reflect the overall student population of Form 4, our measurement of student diversity is representative of the overall student population in Form 4 in the twenty schools surveyed.

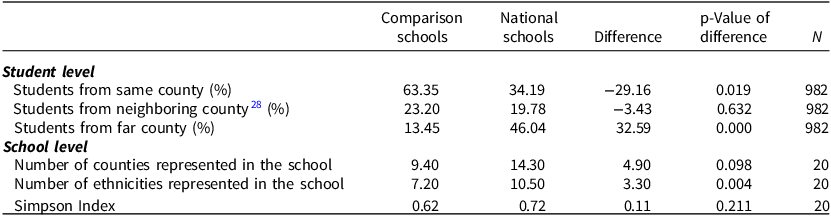

We find that there is indeed a large and statistically significant difference in student body diversity when determined by county of origin. Of the students in comparison schools, 63 per cent are from the county where the school is located, compared with only 34 per cent of students in national schools (p < 0.05, Table 1). Only 13 per cent of students in comparison schools are from far-away counties (defined as counties that do not share a border with the school county), compared with 46 per cent of students in national schools (p < 0.001, Table 1). From this we can conclude that the student body make-up of the national schools is more diverse. We also investigate how diversity in terms of county of origin translates to ethnic diversity in the school. We first look at the number of self-reported ethnic groups present in the school and find that national schools indeed contain students from three additional ethnic groups, on average (p < 0.01).

Table 1. Student diversity, by school type

Next, we examine diversity using Simpson’s Index of Diversity. Simpson’s Index of Diversity can be interpreted practically as the probability that two individuals randomly drawn from the sample will be from a different ethnic group. The scale ranges from 0 to 1, with higher numbers indicating a higher level of diversity. The index was initially created for measuring diversity in the biological sciences (Simpson Reference Simpson1949), but it has since been applied to various fields of study, including crop diversity in agriculture, dietary diversity in food security, and ethnic and racial diversity in the social sciences (Adjimoti and Kwadzo Reference Adjimoti and Kwadzo2018; McLaughlin et al. Reference McLaughlin, McLaughlin, McLaughlin and White2016; Moody Reference Moody2001). It is also equivalent to the Herfindahl–Hirschman index, which is used to study market diversity in economics. The index is calculated using the following formula, where p represents the proportion of the school that comes from group i, and R represents the total number of entities in the dataset. We observe that national schools have a higher diversity index score (Table 1). However, this difference is not statistically significant, likely due to the small number of schools in our sample and wide variation in this score, particularly among comparison schools.

Equation (1): Simpson Index

$$D = 1 - \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^R p_i^2$$

$$D = 1 - \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^R p_i^2$$

We note that outside of student body diversity, there are very few differences between treatment and comparison schools. Research has shown that school infrastructure and classroom climate have had a positive impact on outcomes such as tolerance and institutional trust (Campbell Reference Campbell2006), so it is important to make sure that these other differences are not driving our results. This tests our hypothesis that the schools are statistically similar on characteristics other than the treatment (student body diversity). We use two data sources to make these comparisons – school observation data and student surveys. See online Supplementary Material (Table A2) for balance tests.

From the school observation data, we observe that the schools differ from each other in very few characteristics. In our sample, we fail to detect a difference between treatment and comparison schools in terms of student housing, eating, and bathing facilities; classroom infrastructure and personnel such as books, computers, laptops, study lounges, tutoring rooms, or libraries; recreational and additional spaces such as sports facilities, nursing offices, guidance counselors, and availability of activities such as extracurricular clubs. From this, we can conclude that becoming a new national school has not led to broad and significant improvements in school infrastructure. Local reporting on the policy finds a similar scenario – namely that these new national schools failed to meet the standards of the ‘original’ national schools in terms of infrastructure and facilities (Ouka Reference Ouka2018) – such that they are not that dissimilar from extra-county schools, which make up our comparison. We also investigate teacher diversity and note that across the treatment status, teachers are comparable in terms of diversity (measured by county of origin and proportion from the school’s county). Thus, we can identify the main school-level difference as the level of student body diversity.

Given greater diversity within national schools, we take attending the national schools to be a proxy for ‘contact’ with more diverse others but also places where there is a higher likelihood of making an outgroup friend. The next section explores the direct effect of national schools and thus being exposed to higher levels of student body diversity, as well as the additional role that making friends from other ethnic groups might have on the outcome variables of interest.

Analytical Model: Multivariate Regression and Mediation Framework

Our analytical approach is as follows. We run multivariate regression analysis on the dependent variables of interest (trust, tolerance, national identity). We control for relevant covariates, including gender of the student, mother tongue (as a proxy for ethnicity), whether the respondent was in the dominant ethnic group or not, and religion. We include county-level fixed effects and present robust standard errors clustered at the school level. Our data are weighted to represent the entire Form 4 student population, and post-stratified by the proportion of students under 18, since this group followed a different consent procedure. For all outcome variables, we employ ordinary least squares (OLS) regression.

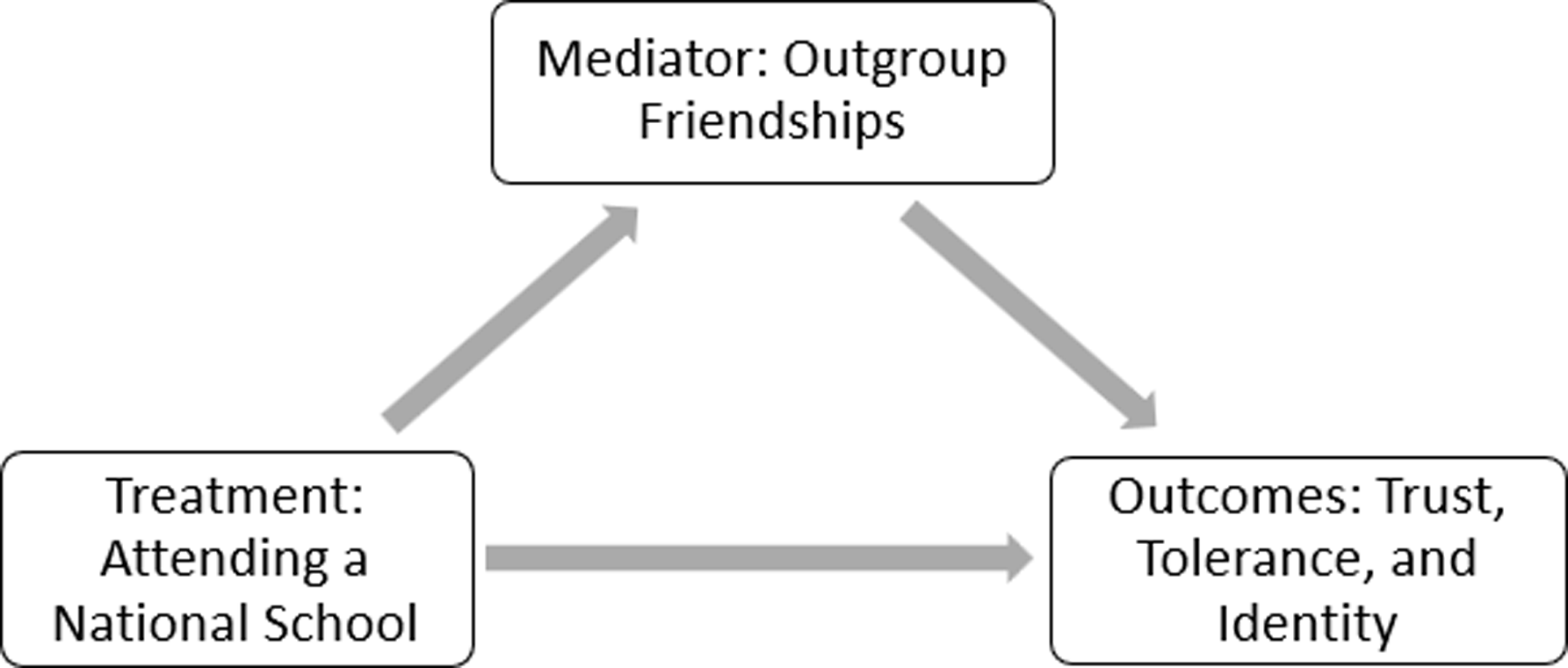

Then, we explore the mediating effects of friendship on these outcomes. We aim to understand if attendance in a national school is associated with greater trust, tolerance, and identity formation; we posit that this might happen through the mechanism of outgroup friendships. We first explore the relationship between national school attendance and diversity of friend groups to confirm that those going to new national schools do in fact have more diverse friendships. In order to calculate the average causal mediation effect (ACME) of friendships on these outcomes, we employ a potential outcomes framework (Imai et al. Reference Imai, Keele, Tingley and Yamamoto2011). Analysis is conducted using Stata 18’s mediate command, with the outcome model specified as a probit, as all outcomes tested are binary. The mediation model is specified as a linear probability model. Figure 2 depicts the mediation mechanism tested. Further sensitivity analyses of the model are presented in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 2. Mediation model diagram.

Outcomes Variables: Tolerance, Trust, and National Identity

First, we explore the impact of national school enrollment on national identity prioritization, trust, and tolerance. Tables 2 and 3 explore the effect of attending a national school and our three outcomes of interest using a multivariate regression. First, in Table 2, we examine respondents’ prioritization of national identity as compared to narrower ethnic-based identity categories. Respondents were asked to rank which identity is most important to them from a list of options: national identity, ethnic group, African identity, religion, and, due to the nature of this study, also county of origin. Students were instructed to rank the five options from 1 (most important) to 5 (least important). Again, we ran a similar multivariate regression analysis on the outcomes of this question. The variable in the first column indicates if the student ranked nationality over the more local identifiers (ethnicity and county). The second column indicates if they ranked ethnic group over the broader options (nationality and African identity). We use this specific operationalization to capture the transformation of identity preference intended by the Ministry of Education: can we encourage learners to prioritize being Kenyan over any allegiance to any subgroup? We see a statistically significant relationship between being enrolled in a national school and probability of ranking nationality above more local identities such as county or ethnicity.

Table 2. Diversity of student’s friend group

Note: robust standard errors in parentheses, *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

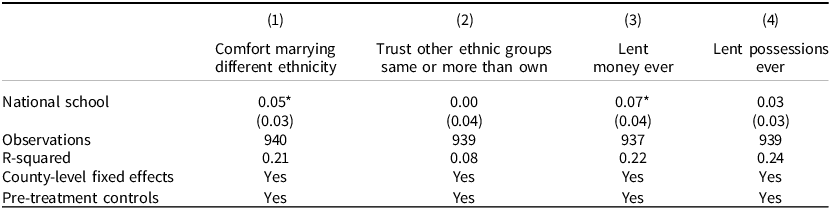

Table 3 explores the direct effect of attending a national school on the other two outcome variables: trust and tolerance. Our indicator of tolerance is self-reported comfort marrying a person outside the student’s ethnicity. We also measure self-reported trust and trusting behavior (lending money and lending possessions) as well as whether the respondent ‘trusts other ethnic groups the same or more than own group’. These first two measures of self-reported behavioral trust best capture general trust towards communities these students are embedded in. The third measure references trust towards a specific outgroup. Again, we present multivariate regression analysis controlling for pre-treatment covariates. There is no consistent, direct effect of attending a national school on trust or tolerance. We see that attending a national school is positively correlated with stating comfort in marrying someone from a different ethnicity and lending money, but only at p < 0.10 significance.

Table 3. Multivariate regressions, identity outcomes

Note: robust standard errors in parentheses. Pre-treatment covariates include gender, religion, mother tongue, and prior exposure to diversity (neighbors in home community speak another language). *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Student Body Diversity and Outgroup Friendship

We explore the effect of being enrolled in a new national school on outgroup friendship. It is possible that the students go to a school which is more diverse, but they are able to limit their social circles to their own ethnic group only. To test this, we asked students to name up to four of their closest friends. We then inquired about various characteristics of these friends, including religion and ethnicity. We coded these characteristics as different from those of the respondent, or not.Footnote 25 We averaged these characteristics across all the friends listed by the student, to create an index of the proportion of the student’s closest friends who are from a different ethnic group. We ran multivariate regression analysis, to learn about the effect of being in a national school on the percentage of the student’s friend group that are a different ethnicity.

We controlled for other variables that may impact friend choice, such as membership in a dominant (most common) ethnicity, and if the student’s neighbors speak a different language. We also controlled for the gender, mother tongue, and religion of the student. We include county-level fixed effects and present robust standard errors clustered at the school level. In Table 4, we see that students in national schools have a greater probability of having a friend from a different ethnic group. Their friend groups are made up of 9 per cent more outgroup members (p < 0.01) than friend groups in non-national schools. Membership in a dominant ethnic group is negative and statistically significant, indicating that, consistent with previous research, students in dominant ethnic groups have a less diverse friend group. As might be expected, having a neighbor who speaks another language is also associated with a higher likelihood of having a more diverse friend group. We do not observe statistically significant relationships between other covariates (religion, mother tongue, gender, or county, not shown) and friendship diversity.

Table 4. Multivariate regressions, student tolerance and trust outcomes

Note: robust standard errors in parentheses. Pre-treatment covariates include gender, religion, mother tongue, and prior exposure to diversity (neighbors in home community speak another language). *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

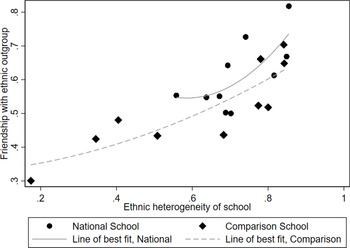

Figure 3 illustrates the school’s diversity index score with the proportion of a student’s friends who are from another ethnicity. The cluster of circles in the upper-right-hand quadrant of the figure indicates that national schools have more ethnic diversity, and students in these schools have a higher proportion of their friend group coming from other ethnic groups besides their own. We can also observe that the situation for the comparison schools is much more mixed, with some schools having similar levels of ethnic heterogeneity and ethnically mixed friendships, but others falling much lower on both scales.

Figure 3. Ethnic heterogeneity and friendship with ethnic outgroup, by school type.

Mediation Models

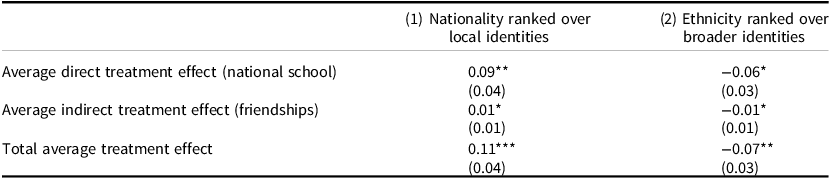

Next, we employ causal mediation models to determine whether national schools can affect these outcomes by fostering inter-ethnic friendships. Pursuing the causal mediation model with these outcomes, we observe average direct treatment effects of attending a national school on prioritization of national identity (Table 5, Model 1). This is consistent with the multivariate regression models above. This effect also carries over to the total average treatment effect. However, we do not observe a mediating effect of outgroup friendships on prioritization of national identity over the more local identities. Finally, these two components seem to come together when we operationalize the outcome as a prioritization of ethnicity over broader categories such as Kenyan or African identities. There is a total average treatment effect of a 7-percentage point reduction in this prioritization (Table 5, Model 2).

Table 5. Average causal mediation effects, social identity outcomes

Note: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1, robust standard errors in parentheses. Covariates included in model: member of a majority group in the school, gender, home language. County-level fixed effects and clustering at school level. In Model 2, local identities are ethnicity and county of origin. In Model 4, broader identities are Kenyan or African.

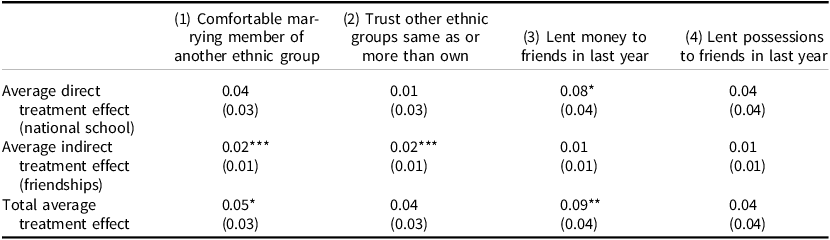

We further investigate the causal mediation effects of diverse friendships on the trust and tolerance outcomes. While there was no statistically significant direct effect of attending a national school on these outcomes, we can observe an indirect, or mediating effect of diverse friendships on the outcomes of tolerance, as reported comfort marrying a member of another ethnic group, and trust, as measured by reporting to trust other ethnic groups the same as or more than one’s own group (Table 6, Models 1 and 2). These effects are statistically significant but somewhat small in magnitude – therefore, they do not translate to total average treatment effects. In terms of trusting behaviors (lending possessions or money), we do not observe similar indirect effects of friendship (Table 6, Models 3 and 4). In one case (lending money), we note that the direct effect, which is only significant at the ten percent level, appears to interact with the indirect effect (which is insignificant) to produce a total average treatment effect that is significant at the 5 per cent level (Table 6, Model 4).

Table 6. Average causal mediation effects, trust and tolerance outcomes

Note: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1, robust standard errors in parentheses. Covariates included in the model: member of a majority group in the school, gender, home language. County-level fixed effects and clustering at school level. First model also includes a covariate of reported parents’ comfort with respondents marrying a member of another ethnic group.

Discussion

In this paper, we find that national schools are associated with a greater prioritization of ‘Kenyan’ identity consistent with the government’s attempts to build civic nationalism. We attribute that to the greater diversity of student bodies in national schools as our national and comparison schools are similar in most other ways.Footnote 26 Attending a new national school is associated with the prioritization of national identity over localized identities. Conversely, we do not find any direct effects of national schools on trust or tolerance. However, we find that friendship with other ethnic groups, which is more common in national schools, serves as a mediating factor that leads to significantly higher levels of reported trust and tolerance. Finally, we find no consistent evidence of direct effects of national school attendance, or the mediation of friendship, on trusting behaviors such as lending money or possessions.

The results highlight important differences between ‘contact’ and a deeper connection between students as friends. It suggests ‘friendship’ as a promising mechanism that could help explain instances where sustained or regular contact can have a more powerful effect than contact alone. In some existing work on contact in other environments, like through sports or training, scholars manipulate group composition to assess the role of outgroup contact on discrimination, attitudes, and pro-social behavior, but find limited impact on sustained behavior or attitudes (Scacco and Warren Reference Scacco and Warren2018; Mousa Reference Mousa2020). Footnote 27 It could be possible that the interactions within these interventions were insufficient to create friendships among diverse participants. Consistent with the setting of our study, diverse interactions characterized by longer time horizons and more organic settings that facilitate repeated contact – such as Okunogbe’s (Reference Okunogbe2024) study of the effects of national service placement and exposure to diversity in Nigeria, Corno et al.’s (Reference Corno, Ferrara and Burns2022) research on mixed-race roommate pairs in South Africa, and Mo and Conn’s (Reference Mo and Conn2018) work on the impact of participation in the Teach for America program in the United States – have uncovered more lasting positive effects of exposure to diverse others such as inter-ethnic romantic relationships, willingness to live outside of one’s home region in the future, national pride (Okungbe Reference Okunogbe2024), reduction in outgroup stereotypes, increase in interracial friendships (outside that of the roommate) (Corno et al. Reference Corno, Ferrara and Burns2022), and greater adoption of marginalized groups’ beliefs (Mo and Conn Reference Mo and Conn2018). It is possible that these ‘interventions’ gave the participants ample time and the right setting to create friendships that drove some of these results.

We observe differences in levels of tolerance, national civic identity, and inter-ethnic trust among learners with more inter-ethnic friendships. We find that attending a national school is associated with increased diversity of friendship. These findings suggest that inter-ethnic contact in schools could play an important role in fostering diverse friendships. It is important to note that there may be self-selection in the learners that pursue diverse friendship opportunities. For example, we find that previous exposure to diversity, proxied by having neighbors at home who speak a different mother tongue, is also consistent with a greater likelihood of having outgroup friends (Table 2). It may be that only a subset of students – who are predisposed to be more tolerant or trusting to those unlike them – are also more likely to form inter-ethnic friendships given the opportunity presented by national school attendance.

There are a few limitations to our findings. First, the most important limiting factor is sample size, which was largely driven by available resources. A sample of only twenty schools, and fewer than 1,000 students overall, limits our statistical power to detect effects that are small in magnitude or pursue subgroup analysis. It also limits our ability to explore school-level variables. Further, our data are cross-sectional, meaning we only observe outcomes at a single point in time. Without a baseline data collection, we cannot be sure that the effects are driven by unmeasured pre-treatment variables.

Next, our mediation model could be sensitive to potential confounders. Though school curricula are the same in all schools, there may be other unobserved characteristics about the national schools’ environment, socialization, or school culture (beyond what we observe as covariates) that foster better friendships that might also be part of the mechanism for how these diverse friendships form and impact trust, tolerance, and identity in national schools. Indeed, sensitivity analyses (see Supplementary Material) indicate that our mediation analysis is likely sensitive to potential confounders, which could affect both intergroup friendship and outcomes of trust, tolerance, or identity. This is expected, as the mediation effects observed in this analysis were small in magnitude and did not consistently translate to overall average treatment effects. With a larger sample of schools, future studies could test potential confounders such as school culture or activities that enable or foster friendship. Potential confounders at the student level could also be explored. For example, Myers and Tingley (Reference Myers and Tingley2016) investigate if emotions, such as anger, guilt, anxiety, and uncertainty can mediate interventions aimed at increasing trust between groups. Research in social psychology dives into the cognitive and affective (emotional) processes of reducing prejudice and interacts with these different processes with direct and indirect friendships to understand which has the most effect on prejudice reduction (Paolini et al. Reference Paolini, Hewstone and Cairns2007). Our survey did not measure outcomes related to emotion, such as anxiety, anger, uncertainty, or fear. Future research exploring such potential mechanisms would greatly enrich the findings presented here.

Next, we should consider the magnitude of these effects. A 9 per cent change in diverse friendships, while significant, implies that likely some individuals made one close non-co-ethnic friend as a result of being in the national school, and some respondents did not make any. Readers may consider an effect of this size to represent a ‘nudge’, but others may consider that one close friendship could indeed be meaningful in changing outlooks towards outgroups. Indeed, we observe that this is the case here, as friendships did play a mediating role in improving self-reported trust and tolerance. However, the magnitude of those effects is small as well. Policy makers and implementers can compare these effects to other effects in the social cohesion space, in deciding what types of interventions to prioritize.

Lastly, these findings should not be generalized to all secondary school students. We examine this effect in the context of a government-led policy promoting intergroup contact; it is possible that this program shaped school culture in important ways that allows these friendships to form. In a setting where student diversity is not valued by school and government leadership, intergroup contact may not be able to generate friendships. We know that in many other educational contexts heightened diversity can lead to self-segregation (Moody Reference Moody2001), and we observe in our data that members of the ethnic majority have fewer friendships outside their own ethnic group, compared with members of ethnic minorities (Table 2). Further, we examine these outcomes among what could be considered the young Kenyan elite. These schools aspire to be the top schools in Kenya; they are tasked with educating the next generation of leaders. Lower-quality schools in Kenya are day schools, which would imply less intensity of contact for learners (Zachariah and Joshua Reference Zachariah and Joshua2016). Imposing diversity quotas in day schools may not elicit as many school friendships, as students would have less sustained contact with their classmates as compared to boarders. Trust, tolerance, and national identity are also all outcomes that are known to vary by economic status or educational level. We cannot say that these outcomes would be realized among students whose parents cannot afford to send or are opposed to sending their children to boarding school, or among students who could not gain entrance into these schools. Further, there may be limits to the degree that students generalize from experiences in schools to broader communities. When students report measures of trust and trusting behavior (lending money and possessions) they are likely to be referencing general trust within this elite schooling ecosystem that might not translate to broader inter-ethnic trust outside of the school walls. Nevertheless, we believe these outcomes are important. The next generation of leaders can have an immense effect on Kenyan politics, policy, business, and more. It is worthwhile to understand if school-based policies can nudge those individuals in the direction of inter-ethnic trust, tolerance, and a sense of civic national identity. This paper provides quasi-experimental evidence that a diverse schooling experience may indeed achieve such an effect for a critical subset of Kenyan youth.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425100690

Data availability statement

Replication data for this paper can be found in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/47SXKJ.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Principal Secretary of Basic Education in Kenya and all the Ministry of Education staff in Kenya who facilitated access to schools and the data collection process, as well as all the principals and students from the study schools. We recognize Shana Scogin, Trevor Lwere, Patrick McCabe, Brian Olemo, Aisha Tunkara, and Lughano Kabaghe for valuable research assistance related to survey design and data analysis. We thank Zizi Afrique Foundation for partnering with University of Notre Dame in this study. We thank Hellen Neria, Alloyce Ngao, Michael Juma, Brian Ambutsi, Cindy Makanga, Purity Ngina, Karen Arisa, Mellen Bosibori, Stephen Okoth, James Ngome, Belinda Okoth, Caroline Mutuku, Joshua Ndegwa, Jackline Opole, Grace Wanga, Lilian Mvoyi, John Mueke, Enock Imani, Jamesa Wagwau, Janet Wesonga, Edith Wekesa, Roman Kamau, and Faith Mukiria for excellent research support in data collection. We thank Laura Gamboa, Karrie Koesel, Jacob Lewis, Malte Lierl, Scott Mainwaring, and Luis Schiumerini as well as the anonymous reviewers and editors at BJPS for excellent comments. Conference participants at the American Political Science Association Meeting (2023) and the Ford Program in Human Development and Solidarity Seminar Series provided useful feedback, which helped to improve the paper.

Financial support

We received financial support for this project from the Franco Institute for Liberal Arts and the Public Good, the Ford Program in Human Development and Solidarity, and the Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies at the University of Notre Dame.