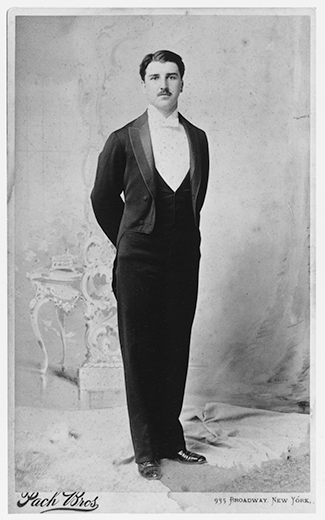

Susan Glaspell’s life can be seen as a mirror image of the lives and decisions of her protagonists, indicating a certain ambivalence toward the social order “that held life in chains” (Glaspell, “The Rules” 208). Glaspell’s protagonists – all women – rebel against social conventions, although there are exceptions: Mother and Dotty in Chains of Dew (1922) resolve to accept that there are times when it is best to maintain the given order even when it means giving up one’s desires and ambitions; however, such sacrifice has to be justified by the supposed good of a loved one. Glaspell, in her decision to leave her hometown of Davenport, Iowa, to devote herself to writing rather than marrying and having children, as women in her time were brought up to do, undoubtedly pained her parents. To top that, not only did she fall in love with a twice-married, divorced manic enthusiast belonging to higher social spheres than her family, George Cram “Jig” Cook, but she eventually married him, moved to New York, and was a significant part of early twentieth-century Greenwich Village bohemia (Figures 1.1 and 1.2).

Figure 1.1 Susan Glaspell at work.

Figure 1.2 Portrait of George Cram “Jig” Cook.

Having disregarded social conventions, she devoted her life to her husband – and later on to her lover, Norman Matson. Rebelling against the strictures of society as to women’s freedom, she then seemingly built them up by frequently ignoring her own good for the sake of the men she loved. Such ambivalence marked all aspects of Glaspell’s life, making it difficult to classify her definitively as a feminist, socialist, modernist – although she was all of these.

Glaspell produced a substantial oeuvre that more than justifies her inclusion in the canon of American dramatists and novelists. Her best-known piece, the one-act play Trifles (1916), has been regularly staged and republished, and also used as a model for playwriting students throughout the twentieth century and beyond;Footnote 1 by the 1970s, both Trifles and itsrewriting as the short story “A Jury of Her Peers” (1917) had been rediscovered by women’s studies and law schools as examples of women’s bonding and the need to change jurisprudence.Footnote 2 In Trifles Glaspell created her absent protagonist, a device that she would use in many of her longer plays and that can be considered characteristic of her dramaturgy. Her plays, stories, and novels are stylistically innovative, witty, intelligent examinations of women’s position in society and, more generally, of the human predicament as seen from a sensitive woman’s point of view, albeit one deeply influenced by the Transcendentalists, and by Ernst Haeckel and Friedrich Nietzsche.Footnote 3 Contemporary critics considered her playwriting to be on a par with that of Anton Chekhov, Henrik Ibsen, and Bernard Shaw (Shay, “Drama”); British critic A. D. Peters believed her to be “the most important of the contemporary American dramatists, and in the opinion of almost all she vies for the first place with Eugene O’Neill” (“Susan Glaspell”). The critical reception of The Verge (1921), Glaspell’s most clearly modernist philosophical piece, was, and still is, mixed, while the realistic, Chekhovian enquiry into the morality of listening to the heart in one’s search for happiness and self-fulfillment, Alison’s House, won her the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1931. Across the twentieth century and beyond her dramas have held the boards; through the efforts of the International Susan Glaspell Society and Artistic Directors committed to women’s dramaturgy, especially at the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond, London, and the Metropolitan Playhouse in New York, a number of Glaspell’s plays have seen recent revivals.Footnote 4 When first published, Glaspell’s novels were also extremely well received, many reaching the bestseller lists, shoulder to shoulder with American greats such as Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. And yet almost all are out of print today and not easy to find except in university libraries.Footnote 5

Susan Glaspell’s ambivalence and rebellion against the social strictures constraining women’s lives in the late nineteenth century, enforced by her parents, particularly her father, must be understood against the backdrop of the nineteenth-century Midwest.Footnote 6 Glaspell was born in 1876 into a family that had seen better days; her mother, Alice Keating, had been a school teacher before marrying Elmer Glaspell, a marriage considered beneath her by her family. He was a builder and sewage contractor whose family had once owned considerable property, but all the wealth had been lost or inherited by the older siblings of previous generations. The young Susie aspired to the culturally lively upper class. After finishing high school, she followed in her mother’s footsteps and graduated from the Scott County Normal Davenport Training School in 1895 (“The Trainers”). Her literary ambitions were nurtured by her mother, while her father, who had a soft spot for his daughter – there were also two boys in the family – overcame his traditional opinions on a woman’s education and career, allowing her to write for the local Davenport Outlook and go to college. Serious journalism was not considered a suitable profession for women in the Midwest at that time,Footnote 7 and the young Susie had to report on social comings and goings until she convinced the editors to give her a column where she could express her own ideas on women’s roles in society. Glaspell enrolled at Drake University in Des Moines in 1897 as a junior and completed her degree in philosophy in 1899; she was a popular student, starring in the debating society and publishing short stories in the college magazine, The Delphic. These stories show her growing interest in the social and philosophical issues that she had already begun to develop in her Outlook column.

Glaspell then took a job as a reporter on the Des Moines Daily News and was assigned the statehouse and legislative beat; among the stories she covered was that of John Hossack’s murder.Footnote 8 The case marked a turning point in Glaspell’s development as a feminist and as a writer, although it would take her almost fifteen years to give literary form to these epiphanies in Trifles. While carrying out her reporting duties, Glaspell also made time to write short stories that she published in popular magazines such as Youth’s Companion and the Metropolitan.Footnote 9 Quitting her job in 1901, she returned home to Davenport determined to write a novel, but the summer of 1902 found her in Chicago, where she registered for two courses at the University of Chicago Graduate School. Judging by a later comment of Cook’s – and extrapolating from Glaspell’s first novel, The Glory of the Conquered (1909) – it seems that she lived through a cataclysmic romance there that had inspired “an ideal of fidelity,” but of which we know nothing more (Cook to Mollie Price, 26, 27 December 1907). There is also a hint of this in the letter Cook wrote Glaspell on reading her novel: “I feel in it your own heart’s knowledge of love – saddened by knowledge that love is less strong than death” (George Cram Cook to Susan Glaspell, 10 December 1907).

In 1904, the magazine The Black Cat awarded Glaspell a $500 prize for the story “For Love of the Hills,” which it published the following year. This success imbued her with confidence that she could indeed make a career out of writing, thereby emulating the Davenport socialite and literary celebrity Alice French (who wrote as Octave Thanet). Glaspell, now a published writer and active in the Davenport Dramatic Club (“Many Amateur Productions”), came under Alice French’s wing, and was invited not only to join the illustrious Tuesday Club but also to give talks to the ladies of society. Much as Glaspell had aspired to this honor, she enjoyed the company of the Davenport rebels and bohemians more, and after meeting the socialist and novelist Floyd Dell, Glaspell joined the Monist Society in 1907,Footnote 10 there coming into frequent contact with the galvanizing Jig Cook, scion of one of the founders of Davenport. Social class differences, however, did not separate them as much as the fact that Cook was waiting for a divorce from his first wife in order to marry Mollie Price, by whom he would have two children. True to her independent spirit and yet bowing to the fact that Cook was a married man, Glaspell left for Europe with her friend Lucy Huffaker in 1909. After touring Holland and Belgium, they settled in Paris; during this almost year-long sojourn Glaspell’s first novel, The Glory of the Conquered, was published.

The attraction to Cook that Glaspell had hoped to stifle on her travels flamed up anew on her return, and her ever more visible relationship with him, and his decision to fight for a second divorce, roused, as he would joke, “Public Opinion” (Cook to Susan Glaspell, 10 December 1907) to such an extent that Glaspell decided to move to New York while Cook joined Floyd Dell in Chicago to write for the Friday Literary Supplement of the Chicago Evening News.Footnote 11 In New York, Glaspell quickly found her place in the bohemian circles of Greenwich Village, making new friends and enjoying the ebullient cultural and literary scene. She joined the Liberal Club, where Freudian analysis dominated all conversations; dined at the Hotel Brevoort, or at Polly’s when short of cash; frequented the offices of The Masses for socialist and political discussions;Footnote 12 and was an admiring member of Marie Jenney Howe’s Heterodoxy Club, a loose organization of women ready to free themselves of the taboos they had been brought up on.Footnote 13 These activities would give her material for her plays, notably Suppressed Desires, The People, The Verge, and Chains of Dew.

Cook joined Glaspell in New York once he had obtained the desired divorce, and they were married on 14 April 1913. They then moved to a rented cottage in Provincetown, Massachusetts, a sleepy fishing village at the tip of Cape Cod, to which the Greenwich Village bohemian crowd liked to escape from the oppressive heat of New York summers. It was there, on 15 July 1915, that they performed their co-written comic one-act, Suppressed Desires, in the home of Hutchins Hapgood and Neith Boyce; the other play of that evening was Boyce’s Constancy. The following summer, Cook, exhilarated by the success of those first performances, announced a season of six plays and told his wife to write one, famously exclaiming, “You’ve got a stage, haven’t you?” when she protested that she didn’t write plays, only short stories and novels (Glaspell, Road 205). That “certain strain of Christian submissiveness which is apparent, not real” (Cook to Susan Glaspell, 10 December 1907) that Cook had once observed in Glaspell, and his conviction that all a playwright needed was a stage, brought out the determination to succeed that characterized her career; she sat down on the bare boards of the stage Cook had built in an old fish shed and allowed Trifles to take form. Finally, she was able to put the emotions that the Hossack case had awoken into words. The play was performed on 8 August 1916 and its topic, the relationships between men and women and our different ways of understanding and communicating, is still compelling today.

The performances were so successful that by the end of the summer the energized actors and playwrights held a meeting and, with Cook and Glaspell at the helm, and supported by Jack Reed and the as-yet-unknown Eugene O’Neill, constituted themselves as the Provincetown Players.Footnote 14 Cook’s ambition to recreate the spirit of Athenian classical drama in America was duly reflected in the Resolutions, which stated unequivocally that the aim of the Players was “to encourage the writing of American plays of real artistic, literary and dramatic merit” (“Minute Book”). Although Susan Glaspell preferred to direct the limelight at her husband, her role was crucial to the smooth working of the Players; she kept Jig focused, took care of all his needs, balanced his frequently manic moods, and acted as his emissary in the conflicts that inevitably arose. Although initially the group had decided that all decisions would be made democratically, it was not long before Glaspell, with their colleague and close friend Edna Kenton, read all the plays that were submitted and decided which should be rejected. Most importantly, she herself submitted eleven plays, among them the modernist, innovative The Verge, where she deals with women’s need for independence and private space to develop as a human being, the politically charged Inheritors (1921), and the feminist comedy Chains of Dew (1922). Glaspell returned to her favorite device, the missing protagonist that she had used so masterfully in Trifles, in many of her plays, most notably in Bernice (1919) and, later on, in Alison’s House (1930).

The seven Provincetown Players years were highly rewarding professionally for Glaspell, albeit far from easy; Cook’s drinking habits and his need to seduce all those around him and to “kindle communal intellectual passion” so giving birth to “an American renaissance of the twentieth century” soon created tensions among the group of amateur actors and playwrights, many of whom had their sights on Broadway (Glaspell, Road 184). Cook’s models were Dionysus and W. B. Yeats, but he lived on a different continent and in a different time, and it fell to Glaspell to keep the peace among the Players and to keep Cook on the path they had chosen, although she too harbored Broadway ambitions, which Eugene O’Neill fostered and supported (Bogard and Bryer 103). It was the success of O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones in 1920 that led to the end of the Provincetown Players as envisaged by Cook.Footnote 15 The internal squabbles that were undermining his authority finally prompted him to follow his dream and leave for Greece in 1922; Glaspell of course went with him, leaving Chains of Dew to be performed in her absence. Kenton, who drafted a history of the group later published as The Provincetown Players and the Playwrights’ Theatre 1915–1922 (2004), makes it clear in her letters to Glaspell that the Players did not honor Glaspell’s wishes as to the casting and staging of her play.Footnote 16 The production was not a success and the play remained unpublished and unrevived till the twenty-first century; the Orange Tree Theatre production in Richmond, London, established the play as a feminist comedy with a disturbing twist that forces the audience to examine preconceived notions of acceptable social behavior.

After a brief stay in Athens, Cook and Glaspell settled in Delphi, where they rented two rooms from the village innkeeper who would become their guide, servant, and friend. Cook enjoyed the company of the local men, drinking with them as he practiced his Greek while Glaspell, knowing herself excluded from this community, explored the ruins of Delphi, spending much time in the reddish-gray cave known as the Castalian spring where those coming to consult the Delphic oracle had once cleansed themselves. They spent the summer of 1922 on the slopes of Parnassos accompanying the villagers and their sheep in search of pasture and cooler temperatures. She based the novel Fugitive’s Return (1929) on her Greek experience, recreating the life of the villagers in this exploration of motherhood, loss, and alienation and the path to a woman’s recovery of her sense of self and power to succor others.Footnote 17

Cook’s grandiose plans to revive the Pythian games in the ruined stadium above Delphi were brusquely interrupted when he fell ill just before Christmas. His health deteriorated rapidly and he died of the glanders, a bacterial infection, on 11 January 1924. He was buried in the village graveyard, with a stone slab from the Temple of Apollo as his headstone. Glaspell returned to America with the mission to mythicize the memory of Jig Cook, or, as she would write to friends, to “make Jig realized by more people” (Susan Glaspell to Lucy Huffaker Goodman, January–February 1924). Her hagiography of the man she had loved and watched over, The Road to the Temple, was published in 1926; it tells as much about Glaspell’s generous nature as about Cook’s cantankerous temperament and flamboyant life. Back in New York she found that her old friends of the Provincetown Players did not cherish Cook’s memory as she did; the Players had been taken over by Eugene O’Neill and Kenneth Macgowan, and Cook’s mission to create a truly American theatre for American playwrights had been brushed aside.

Glaspell, who had hoped to resume her career as a dramatist with the Players, was hurt to the quick. She retired to Cape Cod, to the little cottage in Provincetown to write; Pulitzer Prize–winning Alison’s House was the only play from this period, apart from The Comic Artist (1927), co-written with Norman Matson, with whom she had become intensely involved not long after returning to Provincetown. True to herself, she tried to promote his writing career, taking him with her to Europe in 1931; they lived in London for some months, participating in the literary scene thanks to Glaspell’s renown and contacts. Her plays and novels had been published in England to critical acclaim, and performances of her plays were inevitably successful; she had earned the admiration of Sybil Thorndike and Edith Craig of the Pioneer Players with The Verge, which Craig considered to be a masterpiece (Cummins, “The Verge.”).Footnote 18Trifles went into production at the People’s National Theatre while she was in London.

On returning to America – alone, for Matson had left her for a younger woman – Glaspell settled down in Provincetown to write, finding solace in drink and in the group of friends who rallied round, among them Mary Heaton Vorse, the Hapgoods, Edmund Wilson, and John Dos Passos. In 1936 she was appointed director of the Midwest Play Bureau for the Federal Theatre Project and moved to Chicago.Footnote 19 Glaspell was an obvious choice for such a position; in many ways, the objectives of the Federal Theatre coincided with Cook’s dream of a truly American theatre – a dream that Glaspell had made her own. Hallie Flanagan, director of the Federal Theatre, declared, “If the plays do not exist we shall have to write them” (“Federal Theatre Tomorrow” 6), echoing Cook’s injunction to Glaspell when he told her to write a play back in 1916. In Chicago, Glaspell found her hands tied by red tape and administrative responsibilities, yet she managed to make clear to Flanagan that she was there to encourage the writing of plays about the Midwest by Midwesterners and make them ready for the stage. The task entailed mentoring dramatists during the revision of their work, so took her back to the days when she had sat on the Provincetown dunes with young aspiring writers, among them Eugene O’Neill and Sinclair Lewis, discussing their writing. Among her successes were Theodore Ward’s Big White Fog and Arnold Sundgaard’s Living Newspaper Spirochete. Sickened by the bureaucracy of the Federal Theatre and feeling that she had overcome the writer’s block Matson’s betrayal had brought on, she now wanted to devote herself to the new novel that was asking to be put down on paper; she finally resigned in 1938. The Morning Is Near Us was published in 1939 and selected as Book of the Month by the Literary Guild in April 1940. Later that year, responding to the outbreak of war in Europe, she published a story for children, Cherished and Shared of Old, dedicated to her goddaughter Susan Marie Meyer and her brother Karl. In 1942, she published Norma Ashe.

Glaspell’s restored confidence in herself as a writer led her to write one more play, Springs Eternal (c. 1944), set in the context of World War II. Casting aside her pacifist beliefs, Glaspell allowed her idealism to come to the fore in a discussion of the part American men should play in saving the world. When she failed to find a producer, she turned the play into a novel, Judd Rankin’s Daughter (published in England as Prodigal Giver), which came out in 1945. This was to be her last novel, although she continued writing to the end of her life.

Glaspell spent her last years in Provincetown, writing, enjoying the company of literary friends, and participating in local activities. Her health was deteriorating, however, and, always a private person, with the help of Francelina, her maid, she destroyed papers and correspondence that she did not want the world to see. Glaspell died of viral pneumonia and an embolism on 27 July 1948, taking with her all the details of her private life and emotions that biographers and readers have since struggled to glean from her published writing and from the scant documents she left us.