1. Introduction

Providing written corrective feedback (WCF) on second language (L2) learners’ written texts is an integral part of L2 writing pedagogy because L2 learners often need external input to develop both language and writing skills (Manchón, 2011). However, offering timely and effective WCF remains a labor-intensive task for L2 writing teachers, given the individualized attention it requires (Lee, Reference Lee2008).

Advances in educational technologies have made the immediate provision of automated written corrective feedback (AWCF) by automated writing evaluation (AWE) systems possible, thereby alleviating the burden on L2 writing instructors to provide timely WCF. Powered by sophisticated language processing technologies, today’s AWE systems such as Grammarly, Criterion and Pigai have been shown to help L2 writers with their writing in different aspects, including providing immediate and useful feedback, promoting student engagement with feedback and improving their writing quality (e.g. Fu, Zou, Xie & Cheng, Reference Fu, Zou, Xie and Cheng2024; Karatay & Karatay, Reference Karatay and Karatay2024; Shi & Aryadoust, Reference Shi and Aryadoust2024; Zhang & Hyland, Reference Zhang and Hyland2018, Reference Zhang and Hyland2022). Despite these benefits, their suboptimal performance in accuracy and coverage remains a persistent problem (e.g. Bai & Hu, Reference Bai and Hu2017; Dikli & Bleyle, Reference Dikli and Bleyle2014; Karatay & Karatay, Reference Karatay and Karatay2024; Liu & Kunnan, Reference Liu and Kunnan2016; Shi & Aryadoust, Reference Shi and Aryadoust2024). Radical technology innovation is needed to improve their effectiveness.

One possible solution is to use large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT. Hailed as a game changer in language education due to their capabilities, they may surpass those of traditional AWE systems (Kohnke, Reference Kohnke2024; Shi & Aryadoust, Reference Shi and Aryadoust2024). However, existing studies have not clearly substantiated their potential (e.g. Wu, Wang, Wan, Jiao & Lyu, Reference Wu, Wang, Wan, Jiao and Lyu2023; Xu, Polio & Pfau, Reference Xu, Polio, Pfau, Chapelle, Beckett and Ranalli2024). We speculate that this problem may stem from the use of overly simplistic prompts that lack integration of WCF expertise (e.g. Mizumoto, Shintani, Sasaki & Teng, Reference Mizumoto, Shintani, Sasaki and Teng2024; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Wang, Wan, Jiao and Lyu2023), which might have resulted from insufficient artificial intelligence (AI) literacy. Given that effective prompt formulation is a core element of AI literacy in the generative AI era, we draw on the notion of domain-specific AI literacy (Knoth et al., Reference Knoth, Decker, Laupichler, Pinski, Buchholtz, Bata and Schultz2024), framing our domain-specific prompt designs as a practical embodiment of this concept. On this theoretical basis, the current study investigates how different prompt designs, with and without domain-specific expertise, influence ChatGPT’s capacity to generate AWCF.

2. Traditional AWE systems for AWCF

Traditional AWE systems are underpinned by different technologies including statistics, natural language processing, AI and machine learning for different error categories (Cotos, Reference Cotos2014; Leacock, Chodorow, Gamon & Tetreault, Reference Leacock, Chodorow, Gamon and Tetreault2014). Their performance is often evaluated by accuracy and coverage which are respectively measured with precision and recall. Precision is calculated by dividing the number of accurately detected errors (true positives) by the total number of detected errors; recall is calculated by dividing true positives by the total number of errors flagged by human experts in a given corpus (Leacock et al., Reference Leacock, Chodorow, Gamon and Tetreault2014). For example, in an essay with 100 language errors, if an AWE tool detects 40 errors with 30 true positives and 10 false positives (i.e. correct textual segments wrongly marked as errors), the accuracy and coverage measured by precision and recall are 75% (30/40) and 30% (30/100) respectively.

Ideally, both precision and recall should be high for a good AWE tool. However, a trade-off effect exists between the two metrics of traditional AWE systems (Chodorow, Gamon & Tetreault, Reference Chodorow, Gamon and Tetreault2010; Grammarly, 2022). To minimize the notoriously disruptive impact of false positives on users, developers often prioritize precision over recall by trying to enhance the former at the expense of the latter (Burstein, Chodorow & Leacock, Reference Burstein, Chodorow and Leacock2003; Ranalli, Link & Chukharev-Hudilainen, Reference Ranalli, Link and Chukharev-Hudilainen2017). Accordingly, thresholds of 70%, 80% and even 90% are set for precision but not for recall (Burstein et al., Reference Burstein, Chodorow and Leacock2003; Quinlan, Higgins & Wolff, Reference Quinlan, Higgins and Wolff2009; Ranalli et al., Reference Ranalli, Link and Chukharev-Hudilainen2017).

Despite the relentless effort to increase precision, the rate is at best moderately satisfactory. Only Grammarly and Pigai were ever reported to have achieved an overall precision of over 90% (Gao, Reference Gao2021; John & Woll, Reference John and Woll2020) while they were also found to have precision rates as low as 67% and 46% respectively (Bai & Hu, Reference Bai and Hu2017; Guo, Feng & Hua, Reference Guo, Feng and Hua2023). Most studies showed that the precision of different systems only surpassed the minimum acceptable threshold (Dodigovic & Tovmasyan, Reference Dodigovic and Tovmasyan2021; Hoang & Kunnan, Reference Hoang and Kunnan2016; Kloppers, Reference Kloppers2023; Lavolette, Polio & Kahng, Reference Lavolette, Polio and Kahng2015; Ranalli et al., Reference Ranalli, Link and Chukharev-Hudilainen2017; Yao, Reference Yao2021). It is not unusual for commercialized AWE systems like Criterion and WriteToLearn to have precision rates of only 58% and 49% respectively (Dikli & Bleyle, Reference Dikli and Bleyle2014; Liu & Kunnan, Reference Liu and Kunnan2016), far below the lowest threshold of 70% (Ranalli et al., Reference Ranalli, Link and Chukharev-Hudilainen2017).

To make matters worse, the recall of different AWE systems is even much less satisfactory than their precision. Only three studies reported an overall recall rate above 60%, with 72% and 63% for Pigai (Gao, Reference Gao2021; Yao, Reference Yao2021) and 66% for Grammarly (Dodigovic & Tovmasyan, Reference Dodigovic and Tovmasyan2021). Mostly, AWE systems have recall rates below 40%. For example, low recall rates were reported for My Access! (< 40%), Grammarly (30% and 35%) and WriteToLearn (19%) respectively (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Feng and Hua2023; Hoang & Kunnan, Reference Hoang and Kunnan2016; John & Woll, Reference John and Woll2020; Liu & Kunnan, Reference Liu and Kunnan2016). To minimize false positives, many researchers simply ignore recall when evaluating AWE systems (e.g. Bai & Hu, Reference Bai and Hu2017; Dikli & Bleyle, Reference Dikli and Bleyle2014; Lavolette et al., Reference Lavolette, Polio and Kahng2015). However, this can be problematic as “low recall indicates a large proportion of errors are missed by the system” (Ranalli et al., Reference Ranalli, Link and Chukharev-Hudilainen2017: 10–11).

Of all the traditional AWE systems, the most influential is Grammarly. With over 30 million daily users, it serves both individuals and enterprises. Although its free version for individuals offers substantially reduced grammar checking and limited AI writing assistance, the paid version, Grammarly Pro, provides full-capacity grammar checking, plagiarism checking and AI writing assistance (https://www.grammarly.com). Its grammar checker delivers AWCF to users on both language and meaning (Markovsky, Mertens & Mills, Reference Markovsky, Mertens and Mills2021) by combining multiple technologies, including a large sequence-to-sequence transformer-based machine translation model, an error-tagging system and a syntax-pattern system (Grammarly, 2022). Given its unparalleled popularity and impressive performance, Grammarly is almost the default benchmark for researchers evaluating LLMs as AWE tools (e.g. Mizumoto et al., Reference Mizumoto, Shintani, Sasaki and Teng2024; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Wang, Wan, Jiao and Lyu2023).

3. Using ChatGPT to generate AWCF

After the sensational release of ChatGPT-3.5 in 2022, educators immediately realized that LLMs like ChatGPT would reshape education, including language teaching and learning, by offering tutoring, creating educational materials, answering subject-specific questions and providing automated feedback (Baig & Yadegaridehkordi, Reference Baig and Yadegaridehkordi2024). The mechanism of ChatGPT in providing feedback differs greatly from traditional AWE systems like Grammarly. Its core component is the transformer model, a neural network architecture designed for a wide range of sequence-to-sequence tasks (OpenAI, 2023). After extensive pre-training on large datasets, the model generates coherent responses using an attention mechanism that selectively focuses on relevant parts of the input sequence (OpenAI, 2023; Vaswani et al., Reference Vaswani, Shazeer, Parmar, Uszkoreit, Jones, Gomez, Kaiser, Polosukhin, von Luxburg, Guyon, Bengio, Wallach, Fergus, Vishwanathan and Garnett2017).

Researchers have experimented with ChatGPT in educational contexts including using it to provide feedback for student writing (e.g. Su, Lin & Lai, Reference Su, Lin and Lai2023; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Wang, Xu, Shadiev and Li2024). Regardless of some barriers (Chen, Zhu, Lu & Wei, Reference Chen, Zhu, Lu and Wei2024), students perceived ChatGPT as a more reliable feedback source than traditional AWE tools (Kohnke, Reference Kohnke2024). Meanwhile, it has been shown to produce both global and local feedback, to a level comparable to or even better than teacher feedback (Guo & Wang, Reference Guo and Wang2024; Steiss et al., Reference Steiss, Tate, Graham, Cruz, Hebert, Wang, Moon, Tseng, Warschauer and Olson2024), allowing it to critically complement the latter (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Yao, Xiao, Yuan, Wang and Zhu2024). Globally, it is demonstrated to support students with content revision (Su et al., Reference Su, Lin and Lai2023) and provide feedback on students’ argumentative writing with impressive accuracy and coverage (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Wang, Xu, Shadiev and Li2024). Locally, ChatGPT can be used to generate AWCF to help writers improve writing accuracy (Pfau, Polio & Xu, Reference Pfau, Polio and Xu2023).

However, researchers who empirically examined the quality of AWCF generated by ChatGPT have reported conflicting findings. Pfau et al. (Reference Pfau, Polio and Xu2023), studying the AWCF generated by ChatGPT-4, found that ChatGPT was limited in generating AWCF. Despite its high accuracy, it had serious drawbacks, including missing a large proportion of errors and being “egregious” in identifying lexical errors (Pfau et al., Reference Pfau, Polio and Xu2023: 3). Similarly, Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Wang, Wan, Jiao and Lyu2023), in a comparison of ChatGPT-3.5 against two AWE systems including Grammarly in correcting grammatical errors in single sentences, showed that ChatGPT trailed traditional AWE tools in accuracy, but outperformed them in coverage. In contrast, Mizumoto et al. (Reference Mizumoto, Shintani, Sasaki and Teng2024) demonstrated that ChatGPT was superior to Grammarly after comparing the correlation of their respective output with expert annotators. Meanwhile, Coyne, Sakaguchi, Galvan-Sosa, Zock and Inui (Reference Coyne, Sakaguchi, Galvan-Sosa, Zock and Inui2023), using a variety of criteria as benchmarks, reported that both ChatGPT-3.5 and ChatGPT-4 performed well on a sentence-level grammatical error correction task. Building on Pfau et al. (Reference Pfau, Polio and Xu2023), Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Polio, Pfau, Chapelle, Beckett and Ranalli2024) explored the impact of prompt design on the ability of ChatGPT-4 (API-key version) to provide AWCF. They found that providing ChatGPT with error categories alongside definitions or examples or both enabled it to produce outputs that correlated more closely with human coders, compared to models without such prompting.

4. Domain-specific AI literacy, prompt quality and AWCF by ChatGPT

The ability to formulate effective prompts represents a core element of AI literacy in the era of generative AI. While multiple AI literacy frameworks have been proposed (e.g. Ng, Leung, Chu & Qiao, Reference Ng, Leung, Chu and Qiao2021; Wang & Wang, Reference Wang and Wang2025), they mostly focus on the knowledge and skills needed for general AI users without considering their discipline or workplace roles. While such generic frameworks can be useful, they often fail to capture the intricacies of knowledge, skills and attitude related to AI use in professional settings. Noticing this gap, Knoth et al. (Reference Knoth, Decker, Laupichler, Pinski, Buchholtz, Bata and Schultz2024) made a distinction between generic AI literacy and domain-specific AI literacy. Defining domain-specific AI literacy as “the capacity to integrate the knowledge of AI with the comprehension of its application requirements within a particular professional field” (p. 4), these researchers propose that this concept encompasses three aspects: (1) the potential use of AI in a given domain, (2) the data in the domain and (3) the ethical, legal and social implications of using AI in the domain. The present study is theoretically grounded in the concept of domain-specific AI literacy, framing prompt design informed by domain-specific knowledge as a practical embodiment of Knoth et al.’s (Reference Knoth, Decker, Laupichler, Pinski, Buchholtz, Bata and Schultz2024) first dimension: identifying and realizing the potential applications of AI within a specific domain. Drawing on this theoretical basis, we examine how prompts, with and without domain-specific knowledge, shape the AWCF outputs of ChatGPT.

Prompts can be classified differently depending on different criteria. For instance, a prompt is considered contextual if it integrates task-relevant context information (Boonstra, Reference Boonstra2025). Existing prompt strategies prioritize how prompts trigger LLM reasoning, leading to classification mostly based on LLM reasoning modes such as Chain-of-Thought (CoT), Tree-of-Thoughts (ToT), and so on (Sahoo et al., Reference Sahoo, Singh, Saha, Jain, Mondal and Chadha2024).

Meanwhile, the crucial role of domain-specific knowledge in prompt engineering has also been noted across fields. In AI research, Ma, Peng, Shen, Koedinger and Wu (Reference Ma, Peng, Shen, Koedinger and Wu2024) and Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Li, Wang, Bai, Luo, Zhang, Jojic, Xing and Hu2023) emphasized that crafting high-quality prompts requires domain-specific knowledge. In the educational context, Dornburg and Davin (Reference Dornburg and Davin2025) showed that ChatGPT-4 generated lesson plans of higher quality when the prompts included guidelines specific to the lesson design. In the field of writing, Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Chen, Wang, Xu, Shadiev and Li2024), by incorporating argumentation knowledge into prompts, reported that ChatGPT-3.5 yielded feedback with impressive accuracy and coverage for students’ argumentative essays. Similarly, Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Polio, Pfau, Chapelle, Beckett and Ranalli2024), in their study of the capability of ChatGPT-4 (API-key version) for AWCF, found that embedding domain-specific WCF knowledge of error categories with definitions or examples or both substantially improved its performance. However, since the error types, definitions, and/or examples were combined in their study, the distinct contribution of each element in prompting LLMs for AWCF remains unclear.

Furthermore, studies have also shown the importance of examples in prompts unequivocally. Since LLMs demonstrate strong learning capabilities from them, it is advisable to include examples if possible (Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Singh, Zhang, Bohnet, Rosias, Chan, Zhang, Anand, Abbas, Nova, Co-Reyes, Chu, Behbahani, Faust and Larochelle2024; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Mann, Ryder, Subbiah, Kaplan, Dhariwal, Neelakantan, Shyam, Sastry, Askell, Agarwal, Herbert-Voss, Krueger, Henighan, Child, Ramesh, Ziegler, Wu, Winter, Hesse, Chen, Sigler, Litwin, Gray, Chess, Clark, Berner, McCandlish, Radford, Sutskever and Amodei2020). Based on the number of examples included, prompts are called zero-shot (no example), one-shot (one example) or few-shot (multiple examples) (Walter, Reference Walter2024). For instance, Yu, Bondi and Hyland (Reference Yu, Bondi and Hyland2024) reveal that the prompt with eight examples outperformed the one with only two examples by using ChatGPT-4 to annotate rhetorical moves in research article abstracts. While it is believed that the more examples in the prompt, the better the output (Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Singh, Zhang, Bohnet, Rosias, Chan, Zhang, Anand, Abbas, Nova, Co-Reyes, Chu, Behbahani, Faust and Larochelle2024; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Mann, Ryder, Subbiah, Kaplan, Dhariwal, Neelakantan, Shyam, Sastry, Askell, Agarwal, Herbert-Voss, Krueger, Henighan, Child, Ramesh, Ziegler, Wu, Winter, Hesse, Chen, Sigler, Litwin, Gray, Chess, Clark, Berner, McCandlish, Radford, Sutskever and Amodei2020), Coyne et al. (Reference Coyne, Sakaguchi, Galvan-Sosa, Zock and Inui2023), by testing with one to six examples, show that integrating two examples yielded the most accurate AWCF in sentence revision tasks. Therefore, prompts can be categorized as generic or domain-specific based on their inclusion of domain-specific knowledge. Both types can be further divided according to whether they include examples.

With the exceptions of Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Polio, Pfau, Chapelle, Beckett and Ranalli2024) and Coyne et al. (Reference Coyne, Sakaguchi, Galvan-Sosa, Zock and Inui2023), a shared problem in existing studies on ChatGPT as an AWE tool for AWCF is the simplistic prompt design. Most of them failed to consider the impact of either domain-specific knowledge or examples on prompt quality. For instance, the prompt used in Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Wang, Wan, Jiao and Lyu2023) only contains the following sentence: “Do grammatical error correction on all the following sentences I type in the conversation” (p. 3). Admittedly, researchers have reasons for adopting such prompts to “replicate the prompting strategies typical of a practicing L2 language teacher with only minimal training in prompt engineering” (Lin & Crosthwaite, Reference Lin and Crosthwaite2024: 5).

Given that prompt quality crucially influences task performance, oversimplistic prompting has very likely rendered ChatGPT to underperform itself severely in generating AWCF (Jacobsen & Weber, Reference Jacobsen and Weber2023). Since prompt quality is heavily influenced by both domain knowledge and examples (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Mann, Ryder, Subbiah, Kaplan, Dhariwal, Neelakantan, Shyam, Sastry, Askell, Agarwal, Herbert-Voss, Krueger, Henighan, Child, Ramesh, Ziegler, Wu, Winter, Hesse, Chen, Sigler, Litwin, Gray, Chess, Clark, Berner, McCandlish, Radford, Sutskever and Amodei2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Wang, Bai, Luo, Zhang, Jojic, Xing and Hu2023; Yu et al., Reference Yu, Bondi and Hyland2024), in this study, we compared the performance of ChatGPT in generating AWCF by using one generic prompt and two domain-specific prompts (zero-shot and one-shot), and benchmarked their performances against the AWCF generated by Grammarly in flagging errors in L2 English learners’ texts. We asked the following research questions:

-

1. How do the different prompts shape the AWCF of ChatGPT?

-

2. How does ChatGPT with the different prompts perform as an AWE system in comparison to Grammarly?

5. Methodology

5.1 Data collection

The corpus consisted of 30 essays written by non-English-major undergraduates at a university in China for a comprehensive English course taught by the first author. These students demonstrated intermediate English proficiency, having passed CET-4 but not CET-6.Footnote 1 The writing task required the students to write an argumentative essay of 150 to 200 words on why students should be encouraged to develop effective communication skills. We opted for the small corpus because of our intention for in-depth analysis of both accuracy and coverage of the AWCF from both ChatGPT with three different prompts and Grammarly.

The coding scheme involved 15 error categories inductively developed from the corpus. The error categories, their definitions and one concrete example of each category were developed inductively from the corpus by following the procedures in Lee, Luo and Mak (Reference Lee, Luo, Mak, Hamp-Lyons and Jin2022) (see supplementary material). It is worth mentioning that we developed the category of direct translation error as the students were frequently found to produce errors due to direct translation from Chinese into English.

To examine how domain-specific knowledge and examples in the prompt affect ChatGPT’s performance in generating AWCF, we designed three prompts with ascending sophistication: Prompt 1, zero-shot generic; Prompt 2, zero-shot domain-specific with error categories and their definitions; Prompt 3, one-shot domain-specific with error categories, their definitions and one example for each error type (see supplementary material).

After finalizing the prompts, the essays were input into ChatGPT-4 (web-based paid version) and Grammarly (paid version) for AWCF generation (see supplementary material for examples). AWCF generation via ChatGPT-4 was conducted in three independent batches, with each dedicated to one prompt (Prompt 1, Prompt 2 or Prompt 3) to prevent cross-prompt interference. Due to the limited memory functionality of ChatGPT-4 during the time of data collection, the relevant prompt was inserted before each essay. To maintain comparability with Grammarly’s single-pass processing, no regeneration requests were made to ChatGPT. All parameters (e.g. temperature) remained at their default settings as the web version’s configurations are predetermined by the platform.

Then, the same essays were uploaded to Grammarly in a single Word document for AWCF generation since its output consistency is not affected by batch size. The resulting AWCF report was exported for further analysis. Meanwhile, online suggestions for correction were consulted when necessary. The AWCF by ChatGPT with the three prompts and by Grammarly were analyzed based on the same procedures described as follows.

5.2 Data analysis

Data analysis was primarily conducted by the first, fourth and fifth authors. To begin with, the first and fourth authors collaboratively identified all errors in the corpus exhaustively, classifying them into 15 error categories inductively with reference to Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Luo, Mak, Hamp-Lyons and Jin2022). The results established the baseline for analyzing the accuracy and coverage of ChatGPT and Grammarly. Disagreement was resolved by discussion between the first and third authors, both of whom were educated at the same top-tier English-medium university, are currently veteran English language professorial staff members, and have published extensively in English.

Secondly, the errors flagged by both ChatGPT-4 with the three prompts and Grammarly were analyzed for accuracy (precision) and coverage (recall). It is noteworthy that we only took error detection into consideration for two reasons. First, error categorization was excluded because Grammarly has its own categories, which differed vastly from those adopted in this study. Meanwhile, error correction was not included as there are often multiple ways to correct a single error, making the calculation of precision and recall extremely thorny. The fourth and fifth authors, supervised by the first author, collaboratively coded the errors flagged by ChatGPT with the three prompts and Grammarly. They first divided the feedback into three types: (1) true positive (matching a manually coded error), (2) false positive, and (3) correct but unnecessary (CbU). When a flagged error did not match a manually coded error, the related suggestions for revision were carefully read. Subsequently, a tentative revision based on the suggestions was made. The flagging was counted as a false positive if new language errors arose from the revision; otherwise, it was counted as a CbU instance. All CbU items were excluded as they do not involve language errors.

The remaining items were further coded based on the abovementioned scheme by the fourth and fifth authors independently. The interrater reliability was 92.7%. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion with the first author. The results were then benchmarked against the aforementioned manual coding result to calculate the precision and recall rates.

6. Results

6.1 The overall number of flagged errors

For the sake of convenience, ChatGPT with the three prompts and the AWCF they generated are labelled GPT-P1, GPT-P2 and GPT-P3 respectively. They varied considerably in the generated AWCF (see Figure 1). Across all essays, GPT-P1 detected only 35 errors, far fewer than Grammarly which flagged 137 errors. The number of errors identified by GPT-P2 grew considerably to 112, though still lagging behind Grammarly. In contrast, GPT-P3 detected 196 errors, substantially overtaking Grammarly.

Figure 1. The number of errors flagged by ChatGPT with the three prompts and Grammarly. GPT-P1, GPT-P2 and GPT-P3 stand for the AWCF generated by ChatGPT with Prompt 1 (zero-shot generic), Prompt 2 (zero-shot domain-specific) and Prompt 3 (one-shot domain-specific) respectively.

As is shown in Figure 1, GPT-P1 lagged behind Grammarly in almost all the error categories with the only exception being direct translation errors. GPT-P2 appeared comparable to Grammarly regarding the number of errors in five categories, namely errors of pronoun, sentence structure, spelling, subject–verb agreement and word order. The number of errors caught by GPT-P3 was similar to or greater than Grammarly in 10 out of the 15 categories. Noticeably, GPT-P3 saliently surpassed Grammarly in detecting four categories, namely errors of word choice or expression, direct translation, sentence structure and pronoun.

6.2 Performance in detecting specific error categories

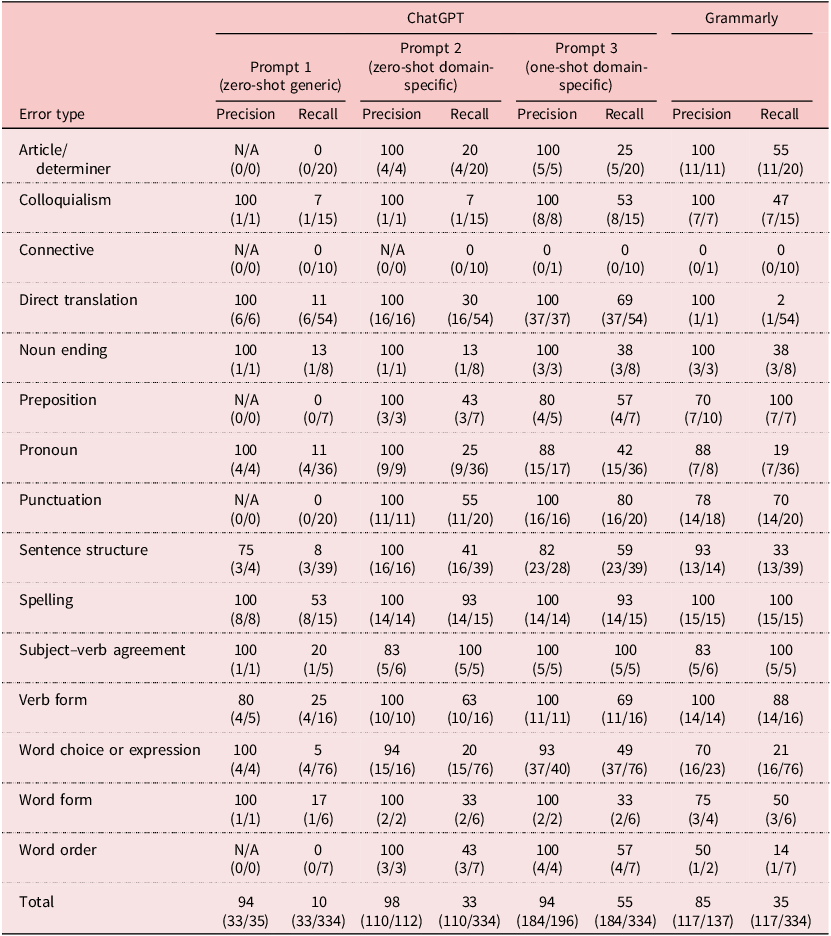

Apart from the number of errors detected, the ascendent performance of ChatGPT in generating AWCF with prompt sophistication is even better reflected by the accuracy and coverage of the errors in terms of precision and recall respectively (see Table 1). To help readers understand the data in Table 1 better, we dichotomized the performance of the tools into good or poor by setting a threshold for both precision (≥ 70%) and recall (≥ 40%). The 70% precision rate was adopted from Ranalli et al. (Reference Ranalli, Link and Chukharev-Hudilainen2017), while the 40% recall rate was provisionally decided according to existing studies on this index.

Table 1. Precision and recall of ChatGPT’s AWCF across prompts compared with that of Grammarly

ChatGPT remained consistently high in precision regardless of prompts, being 94%, 98% and 94% respectively for GPT-P1, GPT-P2 and GPT-P3, higher than Grammarly (85%). In contrast, the recall of ChatGPT considerably improved across prompts, with that of GPT-P1, GPT-P2 and GPT-P3 being 10%, 33% and 55% respectively. Specifically, GPT-P1 only performed well in flagging spelling errors in both precision (100%) and recall (53%). GPT-P2 improved its overall performance in both precision and recall in most error categories except three (errors of connective, colloquialism and noun ending) and pulled four items (errors of preposition, punctuation, subject–verb agreement and verb form) to good performance. Compared with Grammarly, GPT-P2 showed an obvious advantage in direct translation errors and a slight advantage in three other categories (errors of pronoun, sentence structure and word order).

GPT-P3 outperformed Grammarly in most categories. Noticeably, the precision and recall of GPT-P3 greatly increased in six error categories, including errors of colloquialism, direct translation, pronoun, punctuation, sentence structure and word choice or expression. In terms of precision and recall, GPT-P3 surpassed Grammarly in eight categories. Conspicuously, it far outstripped Grammarly in correctly spotting the four categories accounting for most of the errors in the corpus (62%, 206/334), namely errors of direct translation (37/54, 69% for GPT-P3 vs. 1/54, 2% for Grammarly), word choice or expression (37/76, 49% for GPT-P3 vs. 16/76, 21% for Grammarly), sentence structure (23/39, 59% for GPT-P3 vs. 13/39, 33% for Grammarly) and pronoun (15/36, 42% for GPT-P3 vs. 7/36, 19% for Grammarly).

Admittedly, ChatGPT across prompts lagged behind Grammarly in five error categories (1/3 of all categories), namely errors of article/determiner (5/20, 25% for GPT-P3 vs. 11/20, 55% for Grammarly), preposition (4/7, 57% for GPT-P3 vs. 7/7, 100% for Grammarly), spelling (14/15, 93% for GPT-P3 vs. 15/15, 100% for Grammarly), verb form (11/16, 69% for GPT-P3 vs. 14/16, 88% for Grammarly) and word form (2/6, 33% for GPT-P3 vs. 3/6, 50% for Grammarly).

Another problem with ChatGPT was its occasional output inconsistency, an issue well reported in the literature (Mizumoto et al., Reference Mizumoto, Shintani, Sasaki and Teng2024; Pfau et al., Reference Pfau, Polio and Xu2023; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Polio, Pfau, Chapelle, Beckett and Ranalli2024). In this study, although we had expected that errors correctly detected by ChatGPT with a less sophisticated prompt would be flagged by it with a more sophisticated one, this was not always the case. For example, GPT-P2 failed to spot the pronoun error below while GPT-P1 correctly flagged it:

First and foremost, if a student doesn’t master effective communication skills, it is painful for him to communicate with others … if they want to become leaders, having effective communication skills can make them better arrange their work …

GPT-P1: There’s a shift from singular (“a student doesn’t master”) to plural (“they want to become leaders”). Ensure consistency by sticking to one perspective throughout the paragraph, enhancing readability and coherence.

7. Discussion

Drawing on Knoth et al.’s (Reference Knoth, Decker, Laupichler, Pinski, Buchholtz, Bata and Schultz2024) theoretical framework of domain-specific AI literacy, we examined ChatGPT-4’s performance across three different prompts for generating AWCF. By benchmarking its performance with the three prompts against Grammarly, we have shown that prompts grounded in comprehensive WCF knowledge positively influenced ChatGPT’s performance. Overall, our findings revealed a clear improvement in ChatGPT’s performance as prompts became more nuanced and sophisticated. While GPT-P1 detected substantially fewer language errors than Grammarly, GPT-P2 exhibited similar performance and GPT-P3 demonstrated impressive superiority. The progressive enhancement in ChatGPT’s performance across prompts is primarily reflected in its detection of the most common error types, including word choice or expression, direct translation, sentence structure and pronoun. Admittedly, compared with Grammarly, ChatGPT exhibited limitations, including a reliance on complex prompts, lower performance in one-third of the error categories and occasional inconsistencies in output.

7.1 Effects of different prompts on ChatGPT to generate AWCF

ChatGPT’s performance was significantly influenced by prompt sophistication, as evidenced by the increasing number of errors detected by ChatGPT with the more nuanced prompts in our study. Its sensitivity to prompts can be explained by the underlying transformer-based architecture of ChatGPT-4, which relies heavily on the attention mechanism to process input sequences (OpenAI, 2023; Vaswani et al., Reference Vaswani, Shazeer, Parmar, Uszkoreit, Jones, Gomez, Kaiser, Polosukhin, von Luxburg, Guyon, Bengio, Wallach, Fergus, Vishwanathan and Garnett2017). Unlike rule-based task-specific traditional AWE systems including Grammarly, ChatGPT processes language in a way that adapts to the instructions given in the prompt, making it capable of focusing on many error categories simultaneously when guided by domain-specific prompts. This flexible architecture allows ChatGPT to optimize output based on improved prompts (Khurana, Koli, Khatter & Singh, Reference Khurana, Koli, Khatter and Singh2023; Vaswani et al., Reference Vaswani, Shazeer, Parmar, Uszkoreit, Jones, Gomez, Kaiser, Polosukhin, von Luxburg, Guyon, Bengio, Wallach, Fergus, Vishwanathan and Garnett2017), leading to enhanced error detection ability with sophisticated instructions in the domain-specific prompts, echoing AI studies about the importance of adding domain-specific knowledge into prompts (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Peng, Shen, Koedinger and Wu2024; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Wang, Bai, Luo, Zhang, Jojic, Xing and Hu2023).

The significantly higher number of correctly flagged errors by GPT-P2 than by GPT-P1 underscores the importance of including detailed WCF knowledge in prompt engineering when using LLMs like ChatGPT to generate AWCF. While most existing studies used very simple generic prompts (e.g. Mizumoto et al., Reference Mizumoto, Shintani, Sasaki and Teng2024; Pfau et al., Reference Pfau, Polio and Xu2023; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Wang, Wan, Jiao and Lyu2023), the advantage of GPT-P2 over GPT-P1 suggests that integrating detailed WCF knowledge of error categories and their definitions can significantly boost the performance of LLMs like ChatGPT in generating AWCF. This finding is consistent with Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Polio, Pfau, Chapelle, Beckett and Ranalli2024) who compared the AWCF generated by the API-key version of ChatGPT-4 with a simple prompt and a prompt with error categories including either definitions or examples or both. Regardless of multiple differences between this study and Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Polio, Pfau, Chapelle, Beckett and Ranalli2024), such as the versions used (user-interface vs. API-key), focus and error categories, we concurred that prompt sophistication can considerably enhance ChatGPT’s performance as an AWE system to generate AWCF.

Admittedly, some existing studies adopting generic prompts also conclude that ChatGPT can be helpful in providing AWCF (Mizumoto et al., Reference Mizumoto, Shintani, Sasaki and Teng2024; Pfau et al., Reference Pfau, Polio and Xu2023; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Wang, Wan, Jiao and Lyu2023). The salient differences in approaches and criteria in those studies complicated meaningful comparison with our findings. For example, Mizumoto et al. (Reference Mizumoto, Shintani, Sasaki and Teng2024) only considered accuracy measured as correlation with human annotation, whereas we took both accuracy and coverage by using the measures of precision and recall. It is now recognized that accuracy alone is insufficient to gauge the quality of any AWE system as one with high accuracy may still fail to detect a substantial number of errors to be truly effective (Ranalli et al., Reference Ranalli, Link and Chukharev-Hudilainen2017).

Like previous studies, the current study also shows that adding examples to error categories and their definitions can further boost ChatGPT’s performance as an AWE system. AI studies have shown that examples are key to prompt engineering (Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Singh, Zhang, Bohnet, Rosias, Chan, Zhang, Anand, Abbas, Nova, Co-Reyes, Chu, Behbahani, Faust and Larochelle2024; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Mann, Ryder, Subbiah, Kaplan, Dhariwal, Neelakantan, Shyam, Sastry, Askell, Agarwal, Herbert-Voss, Krueger, Henighan, Child, Ramesh, Ziegler, Wu, Winter, Hesse, Chen, Sigler, Litwin, Gray, Chess, Clark, Berner, McCandlish, Radford, Sutskever and Amodei2020). In this study, we show that adding only one example to each error category made a great difference in ChatGPT’s AWCF output. Although it is often assumed that more examples lead to better performance in output quality (Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Singh, Zhang, Bohnet, Rosias, Chan, Zhang, Anand, Abbas, Nova, Co-Reyes, Chu, Behbahani, Faust and Larochelle2024), Coyne et al. (Reference Coyne, Sakaguchi, Galvan-Sosa, Zock and Inui2023) showed that, when using a generic prompt for sentence revision tasks, the inclusion of just two examples resulted in the most accurate AWCF. The optimal number of examples needed for domain-specific prompts like ours remains to be further investigated.

Theoretically, our results support Knoth et al.’s (Reference Knoth, Decker, Laupichler, Pinski, Buchholtz, Bata and Schultz2024) distinction between generic and domain-specific AI literacy and highlight the need for the latter. The ascending performance of ChatGPT across the prompts indicates that the ability of using LLMs like ChatGPT to generate feedback by simple instructions just constitutes generic AI literacy. To leverage their potential as effective AWE systems, L2 writing teachers also need domain-specific AI literacy to craft effective prompts like those adopted in this study. In other words, if users fail to translate domain-specific expertise into prompt structure, LLMs like ChatGPT may fall short of professional criteria.

7.2 ChatGPT with different prompts vs. Grammarly in generating AWCF

Compared with Grammarly, the performance of ChatGPT varied considerably according to prompts. With a generic prompt, it flagged far fewer errors than Grammarly (35 vs. 137). Though the former maintained a higher precision (94% vs. 85%), its recall was much lower (10% vs. 35%), indicating that it missed many more errors than the latter. With a zero-shot domain-specific prompt, GPT-P2 came quite close to Grammarly in the number of errors flagged (112 vs. 137), raising both precision (98%) and recall (33%), particularly the latter. Impressively, with the one-shot domain-specific prompt, GPT-P3 greatly surpassed Grammarly in the number of flagged errors (196 vs. 137), with much higher recall (55%) than Grammarly and persistently high precision (94%).

Our results show that with highly sophisticated prompts like Prompt 3, ChatGPT can dwarf traditional AWE systems represented by Grammarly. This finding contradicts Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Wang, Wan, Jiao and Lyu2023) who showed that ChatGPT as an AWE tool was inferior to Grammarly due to the very low precision rate of only 51% regardless of a high recall rate of 63%. While the difference between our findings and those of Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Wang, Wan, Jiao and Lyu2023) may be explained by the difference in the version of ChatGPT used (ChatGPT-4 in this study vs. ChatGPT-3.5 in their study), another important factor is the great difference in the prompts. With Prompt 1, a generic prompt like the one in Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Wang, Wan, Jiao and Lyu2023), we also show that ChatGPT-4 was much inferior to Grammarly as an AWE system. However, with the domain-specific prompts of Prompts 2 and 3, ChatGPT’s performance became first comparable to and then much better than Grammarly.

Although Mizumoto et al. (Reference Mizumoto, Shintani, Sasaki and Teng2024) also concluded that ChatGPT-4 outperformed Grammarly, their findings should only be compared with GPT-P1 in this study due to the simple prompts they used. By comparing the correlation between the AWCF by ChatGPT-4 and Grammarly with human annotations, they found that ChatGPT was superior to Grammarly in accuracy, echoing our finding that the precision of GPT-P1 was higher than that of Grammarly. Once again, it is difficult to compare their results with ours since they measured accuracy differently and failed to take coverage into consideration.

Another noteworthy finding of this study is the impressive growing ability of ChatGPT to detect errors of certain categories with prompt sophistication. Noticeably, its ability grew fastest in flagging the most frequent error types of word choice or expression, direct translation, sentence structure and pronoun. GPT-P1 only overtook Grammarly in correctly flagging direct translation errors (6 vs. 1) but paled in the three other error types (sentence structure: 3 vs. 13, word choice or expression: 4 vs. 16, pronoun: 0 vs. 14). In addition to its growth in flagging direct translation errors (16), GPT-P2 overtook Grammarly in accurately flagging sentence structure errors (16 vs. 13) and became similar to the latter in spotting errors of word choice or expression (15 vs. 16) and pronoun (11 vs. 14). GPT-P3 overshadowed Grammarly in all the four categories (37 vs. 1 for direct translation errors, 23 vs. 13 for sentence structure errors, 37 vs. 16 for word choice or expression errors, and 16 vs. 14 for pronoun errors). Unexpectedly, most of these errors are highly context-sensitive errors, which can impede text comprehension severely, a phenomenon probed in detail in another paper (Luo, Wang, Zhou & Zhao, under review).

8. Conclusion and implications

By comparing ChatGPT’s performance across different prompt types with Grammarly, we found that prompt sophistication significantly influences LLMs’ ability to generate AWCF. Replacing a generic prompt with a domain-specific one can substantially boost ChatGPT’s ability to generate AWCF; adding an example to the domain-specific prompt further improves both the quantity and quality of the output. ChatGPT, guided by domain-specific prompts with examples, exceeded in flagging the most frequent error categories that significantly hinder comprehension in the corpus.

We acknowledge several limitations in the current study, including the small corpus size, the exclusive focus on error flagging without addressing error categorization or correction, and the use of ChatGPT-4 rather than more recent versions. Moreover, as all essays in the corpus were written by intermediate-level Chinese learners within a single institutional setting, the findings may not be generalized to other proficiency levels, text genres or linguistic backgrounds. Despite these limitations, the contribution of our findings is evident in three important aspects. First, this study directly compared a generic and two domain-specific prompts, benchmarked against Grammarly. Second, it shows that domain-specific prompts could greatly empower LLMs like ChatGPT to serve as AWE systems. Third, it provides empirical support for the notion of domain-specific AI literacy (Knoth et al., Reference Knoth, Decker, Laupichler, Pinski, Buchholtz, Bata and Schultz2024), highlighting that effective use of LLMs as AWE systems hinges upon the user’s ability to translate domain-specific WCF knowledge into prompt structure.

Future research could investigate the capacity of LLMs to generate AWCF by adopting larger corpora with texts of different proficiency levels, from different institutional contexts and linguistic backgrounds. Such studies would be more informative if they examine error categorization and correction as well. Meanwhile, researchers may explore how varying levels of prompt sophistication influence learners’ acquisition of specific linguistic features through LLMs. Additionally, they can also investigate how prompts affect the performance of other LLMs in generating AWCF, perhaps by using other traditional AWE systems (e.g. Criterion and Pigai) as benchmarks for detection of specific error types.

Our study has both pedagogical and technical implications. Pedagogically, we provide insight into how L2 English teachers might guide students to use LLMs like ChatGPT to generate AWCF to complement traditional AWE systems like Grammarly. With sophisticated prompts like Prompt 3 in this study, LLMs can greatly outperform traditional AWE systems. However, in this study, Grammarly is shown to maintain three advantages over ChatGPT: (1) no need for prompt engineering, (2) better performance in one-third of the error categories, and (3) consistent output. These advantages suggest that traditional AWE systems like Grammarly still have value in providing AWCF. For L2 English teachers and writers without access to sophisticated prompts like Prompts 2 and 3 in this study, Grammarly remains the preferable choice. Even for those with access to such sophisticated prompts, we recommend using traditional AWE systems like Grammarly as a complement rather than a replacement, due to their strengths in certain error categories and output consistency.

Obviously, L2 English teachers need training for domain-specific AI literacy in addition to generic AI literacy. While AI literacy programs used to focus on general prompt structure like CoT, ToT and basic AI functionalities based on human–AI interaction (e.g. Woo, Wang, Yung & Guo, Reference Woo, Wang, Yung and Guo2024), the rapid evolution of LLMs, particularly reasoning-oriented models (e.g. ChatGPT-5) can reduce reliance on these prompt strategies in certain tasks. Nonetheless, the role of domain-specific expertise in prompt engineering persists, supporting Knoth et al.’s (Reference Knoth, Decker, Laupichler, Pinski, Buchholtz, Bata and Schultz2024) proposition for domain-specific AI literacy. However, we are aware that it is unrealistic for average teachers to develop profound expertise on all the issues they have to teach by completing one or more domain-specific AI literacy training programs. What they can develop from such programs is perhaps more an awareness of the need for highly domain-specific expertise in prompt engineering than the ability to craft such prompts themselves. To make domain-specific prompts accessible to L2 English teachers, we suggest establishing online prompt libraries that allow users to access and reuse expert-crafted prompts (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Wang, Bai, Luo, Zhang, Jojic, Xing and Hu2023). To our knowledge, such libraries do not exist for L2 English teachers yet. Organizations like the TESOL International Association may consider developing them.

Technically, we would like to offer a suggestion for traditional AWE tool developers. While it is laudable that some AWE tools like Grammarly have attempted to keep pace with technological advances (Grammarly, 2023), developers should consider integrating LLMs directly into their platforms. This approach would help address the reality that LLM evolution often outpaces AWE tool development. For example, Grammarly’s superior performance in certain error categories might have been matched or even overtaken by the newer reasoning-oriented LLMs like ChatGPT-5. By incorporating LLMs like ChatGPT directly, traditional AWE systems can align their development with these rapidly evolving technologies.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S095834402510044X

Data availability statement

Data available on request from the authors.

Authorship contribution statement

Na Luo: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing; Yifan Wang: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing; Zhe (Victor) Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis; Yile Zhou: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology; Rongfu Zhao: Formal analysis.

Funding disclosure statement

The work is financially supported by Lanzhou University through the research project entitled Study on ChatGPT and Doubao as Automated Writing Feedback Tools via the 2024 “GenAI + ” Philosophical & Social Science Funds (Grant ID: LZUAIYJYB10).

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval was not required.

GenAI use disclosure statement

This study examined the impact of prompt sophistication on ChatGPT’s ability to generate automated written corrective feedback. Data collection was conducted using ChatGPT-4 in January 2024. The three prompts and related examples are provided in the supplementary material. During manuscript preparation, ChatGPT was used only for proofreading.

About the authors

Na Luo is a professor of applied linguistics at the School of Foreign Languages and Literatures of Lanzhou University. Her research interests include academic writing, writing feedback, and the application of generative artificial intelligence for writing.

Yifan Wang is a graduate student at the School of Foreign Languages and Literatures of Lanzhou University. Her current research focuses on the application of generative artificial intelligence for writing feedback.

Zhe (Victor) Zhang is an associate professor at the MPU-Bell Centre of English at Macao Polytechnic University. His research focuses on computer-assisted language learning, L2 writing, and language and identity.

Yile Zhou is a freelancer. She was involved in this work as a graduate student at the School of Foreign Languages and Literatures of Lanzhou University.

Rongfu Zhao is a graduate student at the School of Foreign Languages and Literatures of Lanzhou University. Her current research focuses on academic writing and English for research and publication purposes.