In her influential 1988 essay “Feminist Theory, Poststructuralism, and Performance,” American performance theorist Peggy Phelan documented her “most disturbingly interesting” exposure to what she calls “Eastern dance forms” at an international gathering of scholars, performers, and the like.Footnote 1 The conference is said not only to have fostered strenuous discussions of the female role in such traditions as Balinese dance-drama, Indian kathakali, Japanese kabuki, and “Chinese opera,” but also to have featured the performance of a youthful male performer of female roles in the Indian odissi tradition. Astonished, if not disappointed, by the conference’s disengagement with the politics of representing female roles, Phelan asserts that “[s]uch classical female roles played by men or women do not, by definition and design, penetrate the ‘identity’ of any female; they are surface representations whose appeal exists precisely as surface.”Footnote 2 And this “surface femininity” is said to hinge upon “immediate recognition of the comic artifice and reverent idealization of the form,” which “reminds the spectator of the absence of the female (the lack) rather than of her presence.”Footnote 3

Openly “indebted to a Western feminist discourse,” the understanding of the feminine effects produced by performers of the Asian theatrical traditions as “a fetishized image” that “makes her actual presence unnecessary”Footnote 4 offers Phelan the opportunity to scrutinize the role of patriarchy and fetishism involved in the historical making of the female role.Footnote 5 Such hermeneutics of classical Asian theatrical performances seems particularly compelling when one takes into consideration the conventional use of female impersonation in Chinese xiqu,Footnote 6 Japanese kabuki and noh, and various theatrical traditions in South Asia as well as their ostensibly flamboyant mise-en-scène. Yet, by arguing that the female-role player embodies an image/ideal in lieu of the female in actuality, Phelan foregrounds an epistemological division between the “surface femininity” of female-role specialists and some kind of femininity, presumably, of the absent actual female: the latter is believed to be able to penetrate beneath the surface, thus suggesting an inner authenticity/substance, whereas the former signifies only a vacuum. Although the divide between the two forms of femininity authorizes Phelan’s critique of classical Asian performances, such an understanding is a product of modernity and cannot cogently explicate the gender performances of female-role players in various Asian theatres in premodern times.

For instance, in Edo Japan (1603–1868), an affinity between onnagata’s (male actors specializing in female roles in kabuki) femininity and that of biological women was greatly valued as codes of femininity were actively circulated between onnagata and female spectators of kabuki. Footnote 7 Besides, Edo onnagata defied this split between image and the real by behaving like women in everyday life.Footnote 8 Hence, the gender of the female-role players, as Maki Isaka (Morinaga) perceptively suggests, should be understood as the “imitating imitated,”Footnote 9 which makes a precipitous distinction between the real and representational quite unnecessary. Perhaps the interpretive potency of the idea of “surface femininity” is further discounted after Judith Butler triumphantly adapted the linguistic concept of “the performative” into gender theory. After all, if gender is what appears on the surface, isn’t it unfair to refute something already on the surface for lacking depth?Footnote 10

Although ideas such as “surface femininity” fail to explicate cogently the subtlety within the gender politics of female-role performers such as Edo onnagata, it is critical to note that twentieth-century performers in many forms of classical Asian theatre also evoked an epistemological distinction between the femininity of the female-role specialists and that of biological women when interpreting their stagecraft, long prior to the appearance of Phelan’s critique. This essay scrutinizes how a comparable idea of “surface femininity” appeared and prevailed in the reception of Chinese xiqu in its modern context, namely the notion of what I term the “artistic” femininity of nandan Footnote 11 and its discursive formation during China’s Republican era (1912–49). The Republican idea of “artistic” femininity resonates with Phelan’s notion of “surface femininity” in many critical ways: both ideas postulate a “theatrical” form of femininity that not only draws upon but, more important, defines itself against the femininity of a mundane woman; in addition, both notions aver a mimetic gap in the theatre, which, for good or ill, can never be annihilated. However, unlike Phelan, who deploys the notion of “surface femininity” to critique classical Asian performance, critics, aficionados, and oftentimes celebrated nandan masters themselves in Republican China tactfully mobilized the idea of “artistic” femininity to serve an utterly different political agenda. In lieu of regarding it as a deficiency of the stagecraft, they took this mimetic gap as a merit of the dramaturgy so as to valorize their engagement in and with the art in an altered cultural and historical context.

Although the idea of “artistic” femininity has become naturalized and foundational to our perception of the gender of nandan in xiqu since the Republican era, a critical examination of the historicity of such an idea has been long overdue. This essay intends to fill this scholarly vacuum by exploring the discursive formation of the very idea as well as the profound limitations it imposed on our understanding of nandan’s gender and way of life. I contend that although the idea of “artistic” femininity suggests that nandan did not necessarily imitate women, such implications are misleading: various accounts indicate that at least some aspects of nandan’s stage performances involved close observation and imitation of the behaviors of women. Moreover, embracing the idea of “artistic” femininity as a priori has not only restricted the fluidity in interpreting nandan’s stagecraft and their gendered personae but also compromised nandan players’ own agency of positioning themselves on the gender spectrum. As we shall see in the following discussion, identifying the gender of nandan as a fictional entity confined the practice of men playing women to the realm of the theatrical stage, jeopardizing the legitimacy of nandan performers presenting their feminine bodies outside the semiotic system of xiqu.

The Advent of Modern Nandan

In 1930, Mei Lanfang (1894–1961), perhaps China’s greatest nandan performer of the twentieth century, made a triumphant visit to the United States. During Mei’s sojourn in New York City, a section of his troupe’s rendition of a kunqu (or kunju, Kunshan opera) play entitled Cihu was filmed. This play, retitled for American audiences as The Death of the Tiger General or Vengeance on the Bandit-General, delineates the story of a lady-in-waiting at the imperial court seeking revenge against a rebellious general upon the fall of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), and was lauded by the noted literary critic Stark Young as the “most complete and admirable” piece of the company’s program.Footnote 12 The valuable footage, now preserved at the University of South Carolina,Footnote 13 thus offers a glimpse of a pivotal scene from the company’s well-received performances in the United States. Using a magnificent peacock design on a large curtain as the backdrop, the staging of Vengeance on the Bandit-General adopts the conventional one-table, two-chair setting of xiqu, even enhancing it with fine silk cloth, showcasing the extensive effort devoted to reconstructing a xiqu stage on American soil. At the center of the theatrical spectacle is the presence of four Chinese actors, three nandan players included, whose “costumes are handsome enough to gratify the exacting taste of Flo Ziegfeld.”Footnote 14 Two nandan actors portraying imperial maidens are seen preparing rice wine, while the female protagonist Fei Zhen’e, embodied by the virtuoso Mei Lanfang himself, uses alcohol and flattering words to sedate the rebel general.

Aside from the scene itself, the historical footage also includes an introductory section featuring the opening remarks by a Chinese student in the United States known as “Miss Soo Yong,” who was recruited by the Mei troupe to step forward and interpret the stories of Chinese plays and the theatre’s conventions.Footnote 15 As depicted in the footage, Yong explicates the Chinese practice of nandan as follows: “Mr. Mei Lanfang takes the part of women’s characters. But he is not a ‘female impersonator,’ according to the Western sense of the words. He does not attempt to imitate the real women in nature. But through lines and movements, he tries to create an ideal woman.”Footnote 16 Characterizing the Chinese drama as a “riddle,” Charles Collins, a theatre critic for the Chicago Tribune—who watched the company’s offering of four short plays/scenes, including Vengeance on the Bandit-General, at the Princess Theater in Chicago on the night of 6 April 1930—noted that the audience’s understanding of the troupe’s performances relied heavily upon the interpretations provided by Yong as a “mistress of ceremonies.”Footnote 17 In line with expository remarks she made in New York City, Yong during the Chicago performances insisted that Mei Lanfang “does not ‘impersonate’ a woman; but he symbolizes, with delicacy of touch, the oriental ideal of the eternal feminine.”Footnote 18 Apparently convinced by this interpretation, Collins reported to readers of the Chicago Tribune that Mei Lanfang “defeats the prejudice of the western mind against female impersonation.”Footnote 19

Of course, for American theatregoing populations in the early decades of the twentieth century, the sight of a cross-dressed male onstage was by no means an exotic experience. During Mei’s tour of the United States, American critics often compared the nandan virtuoso with the country’s own vaudeville female impersonators such as Bert Savoy and Julian Eltinge.Footnote 20 However, although female impersonation in vaudeville had once been considered as “wholesome amusement,”Footnote 21 the practice could cause legal repercussions if deemed excessive. In October 1928, the New York City vice squad conducted two raids on Mae West’s play Pleasure Man at the Biltmore Theatre on Broadway, resulting in arrests of actors and crew members.Footnote 22 The production’s use of female impersonators was censured for its perceived homoerotic overtones and accused of promoting “male degeneracy.”Footnote 23 This incident set the stage for Mei Lanfang’s appearances on Broadway shortly thereafter. When the Chinese troupe extended its sojourn in New York City into the second month, its performances coincided with the March 1930 trial of The Pleasure Man, a legal case that vehemently debated the legitimacy of female impersonation and garnered significant media attention.Footnote 24 Within this context, by denying that Mei Lanfang engaged in female impersonation, the Chinese troupe strategically distinguished nandan from a homosexual practice, therefore justifying its presence on Broadway and subsequent performances across the country.

Although Mei Lanfang’s triumphant tour of the United States partly hinged upon rejecting nandan as a form of female impersonation, implying that the practice and connoisseurship of nandan were devoid of homoeroticism lacks historical nuance. The actor’s own involvement in Beijing’s siyu Footnote 25 (literally, “private residences [of theatre players]”) business during the Qing era (1644–1911) suggests that his early career may have been supported by the homoerotic bonds between beautiful boys and literati that were prominent in this milieu of entertainment and sex. Known as xianggong (“gentle males”) or xianggu (literally, “resemblance of girls”), the Qing residents of siyu titillated enchanted literati by performing a variety of roles—they not only played onstage as theatrical actors, predominantly female-role specialists, but also served as euphonious singing waiters offstage, in addition to alluring male courtesans. In consequence, nandan players in the siyu business circulated coherent feminine bodies transcending the boundary of the theatrical stage.Footnote 26

However, with the introduction of the scientific conception of sex and gender in fin-de-siècle China,Footnote 27 siyu as a peculiar Chinese site of homoeroticism elicited growing hatred from those who considered its presence a source of national stigma. In 1912, the inaugural year of the Republic of China, authorities in Beijing declared siyu illicit and urged its inhabitants to rectify their ways of living. In the Republican era, former siyu players generally endeavored to downplay their previous ties to the stigmatized institution. This contributed to the fact that, during Mei’s tour of the United States, American critics and the general public were largely unaware of the actor’s former identity as a siyu performer. The 1912 prohibition introduced a fundamental change to the identity of male cross-dressers previously engaged in the siyu business: it redefined the profession by identifying the young boys as solely theatrical actors whereas multiple roles had originally constituted their late Qing personae. Unlike the beautiful boys of siyu, the theatricality of whose performances exceeded the realm of the stage, those males who continued to titillate audiences with their alluring feminine appearances in subsequent eras had to mark the stage as the only space in which such theatricality was legitimate.

Yet, the theatricality that was ascribed to the nandan’s bodies had almost always exceeded the boundary of the stage and perhaps functioned in a more complicated way in Republican China than it had operated prior. The Republican division between onstage and offstage did not simply define the professional space but also fostered a further distinction between female dramatic characters onstage and modern male citizens in the public realm. Hence, it marked the boundary of the stage as a transforming site for a nandan to alter his gendered personae. With the monolithic understanding of the stage as a prerequisite for theatricality, it becomes possible for a modern spectator of nandan to read the “women” onstage as “artistic,” “theatrical,” and thus “fictional,” while comprehending the “gentlemen” offstage as “natural” and “mundane.” The split between “artistic” femininity onstage and “natural” masculinity offstage became increasingly essential to the identity of what I term “modern nandan,” a new generation of cross-dressed males in xiqu, whose offstage masculinity (and heterosexuality) needed to be compellingly performed so as to make their stage portrayals of female roles socially acceptable and aesthetically explicable.

I have argued elsewhere that for Mei Lanfang, his performance of masculinity offstage (e.g., retaining a mustache amid the Second Sino-Japanese War of 1937–45) contributed significantly to his enduring iconicity in China.Footnote 28 However, as Republican nandan’s compelling performances of masculinity offstage safeguarded their profession in the new era, another parallel division was ushered in to proclaim nandan’s superiority to their female rivals, namely nüdan. Footnote 29 Although a distinction between nandan’s femininity and that of women was never rigidly drawn before, Republican nandan and their descendants adeptly employed such a division to encourage the audience to understand their femininity as “artistic” and “illusionary,” while apprehending that of biological women as “natural” and somehow essentially “real” (Fig. 1). This interpretation of the relationship between nandan and women gave rise to arguments, such as those articulated by Soo Yong, suggesting that nandan were not necessarily imitative of women. Moreover, it is presupposed that nandan can break free from their “natural” masculinity of everyday life due to their sustained dedication to the art. In contrast, the “natural” femininity of everyday life is said to hinder nüdan from performing competently on the xiqu stage, as they are deemed as mere newcomers to the art. Hence, the advent of this epistemological split between the two types of femininity enabled the nandan practitioners to defend their dominance on the xiqu stage and to contend that the feminine effects appearing onstage should be appreciated without necessarily referring to everyday reality.

Figure 1. The predominant understanding, since the Republican era, of the relationship between nandan’s femininity and that of biological women.

Thanks in part to this novel understanding of nandan’s stagecraft, the artistry of nandan reached its pinnacle in the Republican era: domestically, along with other epoch-marking performers, famed nandan stars such as Mei Lanfang and Cheng Yanqiu (1904–58) led jingju (or “Beijing/Peking opera”) into a most prevailing age; internationally, it was nandan rather than any other type of roles that helped Chinese theatre garner unprecedented international acclaim through their repeated presences on foreign soil. By scrutinizing several Republican nandan’s own accounts of their métier, I call attention to the impact of the notion of “artistic” femininity on our understanding of nandan’s artistry: on the one hand, such a concept refuted any reading of nandan’s gender plasticity as a threat to social morality by interpreting it as an outcome of their long-term dedication to the art; on the other hand, this idea is also profoundly problematic as the distinction between the two types of femininity can never be clear-cut (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. How the circulation of femininity between the two groups defies the understanding of nandan’s femininity and biological women’s femininity as separate entities.

On the Discourse of Xiqu “Aestheticism”

In April 1933, celebrated nandan Cheng Yanqiu returned to China following a fourteen-month sojourn in Europe. In the preceding year, Cheng had traveled through Europe and visited such countries as the Soviet Union, Germany, France, and Italy. During his time there, he watched extensively contemporary European theatre performances and interacted with leading European artists, including German director Max Reinhardt. And these experiences were characterized by Cheng as “eye-opening.”Footnote 30 In an interview with Cheng Yanqiu shortly after his tour, a journalist representing the Beijing-based Shijie ribao (The world daily) asked the nandan to comment on differences between Chinese and Western theatres that he discerned during his trip. Cheng responded:

While the makeup of European theatre pursues xiangzhen,Footnote 31 that of Chinese theatre zeros in on xieyi. Footnote 32 . . . In European theatre, villains are portrayed without excessive exaggeration. And the makeup of all other types of characters also pursues resemblance to the real. [Hence, onstage] nothing does not correspond to real people and events. . . . On the other hand, Chinese makeup has the advantage of immediately signaling to the audience that it is a theatrical performance. Once spectators see this type of makeup and costuming, they will instantly recognize it as an artistic expression, leading to an aesthetic sensation.Footnote 33

When asked whether European theatre casts men in male roles and women in female roles, Cheng responded that cross-dressing was not feasible for European drama, as if such a practice did not exist in European theatrical traditions:

The pursuit of Chinese theatre is symbolism. Once it enters into the realm of the symbolic, it would be fine to use men to play female roles, and vice versa. . . . The aim of European drama is realism. In addition, the beauty of European women is often associated with the buxomness of the body. It therefore would be burdensome for men to perform female roles, just as it would be difficult for women to portray male characters.Footnote 34

Bracketing off robust traditions of cross-dressing in European theatre history, Cheng Yanqiu claimed that the female sexed Caucasian body presented an obstacle that prevented a male actor from effectively performing female roles in European theatre. Other than his reference to the stated racial differences, much of Cheng Yanqiu’s exegesis of female impersonation made himself an active participant in what I call the “discourse of xiqu ‘aestheticism.’” Coming into being in the early Republican era (1912–37), the discourse of xiqu “aestheticism” sought to explicate xiqu by articulating its idiosyncratic aesthetic traits. This intellectual pursuit was possible owing to a fundamental shift in the study of xiqu. Prior to modernity, Chinese literati produced copious amounts of writings on xiqu musicology, dramaturgy, and connoisseurship, which constituted the main body of the “theory” and criticism of xiqu in the “classical” sense. However, this traditional body of knowledge gradually waned in influence with the advent of a decisively modern episteme in the Republican era. In lieu of studying and evaluating xiqu in a previously self-sufficient tradition, Republican intellectuals began to theorize xiqu in relation to its Western counterparts. Central to these modern theoretical projects was a painstaking attempt to theorize xiqu through its aesthetic attributes. During the New Culture Movement (1915–early 1920s), when prominent May Fourth intellectuals called for abolishing xiqu, citing its perceived lack of literary and artistic value, Zhang Houzai (1895–1955), then a student of Peking University and later a prominent xiqu critic, countered this view. Zhang contended that xiqu possessed “pseudo-imagistic” (jiaxiang) qualities that highlighted its distinct aesthetic merits.Footnote 35 Following Zhang’s lead, from the 1920s to the early 1930s, Yu Shangyuan (1897–1970), Qi Rushan (1877–1962), Xu Muyun (1900–74), Wang Pingling (1898–1964), and other scholars introduced a variety of new terms and concepts, ranging from “symbolic” (xieyi) and “artistic” (meishuhua) to “nonrealistic” (fei xieshi) and “aestheticized” (shenmeihua), to characterize the aesthetics of xiqu. Footnote 36 For the sake of expediency and consistency, I employ the term “aestheticism” in this essay as an overarching concept to describe the discursive practice pertaining to the aesthetics of xiqu. Footnote 37 In addition to exploring xiqu’s unique characteristics, the discourse of xiqu “aestheticism” also facilitated a distinction by essentializing Western theatre as a form of xieshi (literally, “inscribing the real,” realism or mimesis), while theorizing xiqu as an art of xieyi (symbolism or semiosis).

Jason McGrath notes that in the early Republican era, filmmakers and cinema critics mobilized the same dualistic divide between xieshi and xieyi to help film define itself against xiqu, though the making of early Chinese film relied heavily upon the repertories and actors that xiqu generously supplied.Footnote 38 In contrast to xiqu, which was considered an intrinsically “symbolic” art, attesting to a “traditional” Chinese aesthetic, film was said to represent a “realist” and “scientific” medium of modernity. Yet, for McGrath, this very distinction between xieshi and xieyi itself was “a product of modernity.”Footnote 39 He maintains that the assertion that xiqu embodies a rigid form of “traditional formalism” is overstated, if not grossly erroneous. It is not only because various premodern accounts of xiqu acting suggest that “[i]ndigenous Chinese drama did in fact posit a correspondence between the fiction of the theater and the truth of life,”Footnote 40 but also because many xiqu artists in the early twentieth century refashioned xiqu “to reflect the priorities of modern realism such as visual mimesis and ‘interior performance.’”Footnote 41

McGrath’s discussion of the political use of the split between xieshi and xieyi in the circles of early Chinese cinema is useful in looking at how xiqu artists and aficionados deployed the same discursive split to serve a different objective. While early Republican cinephiles manipulated the split to valorize film by distancing it from xiqu, participants in the discourse of xiqu “aestheticism” recruited the distinction to defend xiqu by highlighting its differences from Western theatre. It should be noted that for the cinephiles, the distinction between xieshi and xieyi was as much about temporality as it was about aesthetics, as early Chinese film proclaimed itself a decisively “modern” art by openly denouncing its ties to xiqu, a purportedly “traditional” form. In contrast, defenders of xiqu maintained that this distinction was exclusively aesthetic. By doing so, they not only acknowledged xiqu’s contemporaneity with its Western counterparts but also affirmed its aesthetic merits. Historically speaking, such a stance taken by advocates of xiqu was critical because it embraced a proactive affirmation of indigenous culture to combat Western hegemonic cultural codes. This affirmation was particularly significant during a period when xiqu’s cultural values were questioned or even denied by China’s leading intellectuals and prevailing forms of cultural ideologies (e.g., May Fourth radicalism). Of course, epistemologically speaking, such a distinction had its profound limitations, as this aesthetic binary of Western “realism” versus Chinese “aestheticism” resulted from a reductive take on the rich, diverse, and complicated theatrical traditions of both China and Europe. Consequently, the discourse of xiqu “aestheticism” could simultaneously embrace progressive political agendas while imposing epistemological constraints.

With the aid of the new theoretical terms that postulated some kind of symbolic essence within xiqu, nandan practitioners, by the end of the 1930s, could effectively justify female impersonation as a most pronounced manifestation of xiqu’s idiosyncratic aesthetic. As Cheng Yanqiu’s account suggests, by associating the Chinese practice of cross-dressing with xieyi, which was claimed to be the ultimate artistic pursuit of Chinese theatre, Cheng maintained that nandan was an “artistic expression” and the connoisseurship of nandan was sustained by some kind of “aesthetic sensation,”Footnote 42 implying that the feminine effects appearing onstage should not only be understood as an artifice but also be appreciated in their own right.

If Cheng Yanqiu’s travel experiences in Europe helped the nandan assure Chinese domestic readers of the validity of the Chinese practice of female impersonation, Mei Lanfang’s touring performances in the United States provided the nandan par excellence with a critical opportunity not only to broaden his personal fame but also to acquire a wider international recognition of nandan and Chinese theatre in general. As discussed earlier, the legitimacy of the Mei troupe’s appearances on US stages hinged in part on rejecting the Chinese practice of nandan as a form of female impersonation, in light of the stigma in the immediate aftermath of the Pleasure Man controversy. However, equally significant for the Mei troupe was their effort to dispel any perception of nandan as an eccentric oriental convention among the American public. To counteract this notion, Mei himself fully subscribed to the discourse of xiqu “aestheticism” to draw an essential distinction between biological women and female characters that nandan embodied onstage. In a Los Angeles Times interview with journalist Alma Whitaker, a section entitled “Four Children” begins with the following:

The remarkable young man is 36 years of age, married and has four children. [. . .] When I wanted to know if it was difficult for his wife to live with a man who was so amazingly versed in all the feminine tricks and wiles, he smiled deprecatingly. . . “I am not versed in any individual feminine ways. It would not be possible for me to portray any individual woman . . . and certainly never the American woman.” Besides the drama, he is an artist of great merit [. . .] and a teacher . . . to pass on his art as a patriotic duty to China.Footnote 43

Another Los Angeles Times journalist wrote:

Although Mr. Mei, off stage, is a bright young man like any other who would pass in a crowd as a Chinese student at one of our universities or as an embassy or consular secretary, on the stage he seems a woman in every look, not an everyday, realistic woman, however, but a woman conventionalized and formalized as art, the action and the acting of the plays themselves.Footnote 44

Preexisting studies of Mei Lanfang’s visit to the United States have shown that a self-orientalizing tendency within Mei’s construction of alluring Chinese women onstage was essential to his stunning popularity in the country. For instance, Nancy Yunhwa Rao, in her analysis of Mei’s performances and their reception in the United States, contends that through their captivating ancient Chinese beauties and lavish mise-en-scène, Mei Lanfang’s repertories reinforced the “aesthetics of chinoiserie”—Western crafts styled in a “Chinese style”—and constructed an image of China that is “polished, remote, delicate, and placid.”Footnote 45 In a blunter way, Joshua Goldstein describes Mei’s US tour as “tactical Orientalism,”Footnote 46 attributing Mei’s success in part to an “accentuation of the exotic” and “a historicism that denied Peking opera’s contemporaneity with the modern West.”Footnote 47

While the acknowledgment of the reverse orientalism within Mei’s stagecraft is critical, it is equally important to note that the nandan’s effort to counter the Western orientalist reception of Chinese males by presenting himself as a civilized modern Chinese gentleman offstage contributed significantly to his resounding success abroad. The fact that Mei was then a married man with four children was widely introduced during his tour of the United States, though there was no information given to indicate that Mei was also a polygamist and had married three female spouses by the late 1920s. The introduction of Mei’s offstage identities as a husband and a father was often associated with the acknowledgment of the practice of men playing women as a time-honored Chinese “artistry,” as the two above-quoted passages illustrate. The Los Angeles Times report perceptively noted the dual identities in Mei’s gendered personae: while onstage the nandan played female characters; offstage, he would pass as a (male) Chinese student or a diplomat. By postulating that he did not perform “realistic” or “everyday” women but ones that were “conventionalized” and “formalized,”Footnote 48 Mei unmistakably embraced the supposed aesthetic/symbolic essence of the art and highlighted the fictionality of the female characters onstage.

The Nandan Who Went “Astray”

If, by participating in the discourse of xiqu “aestheticism,” the internationally acclaimed nandan such as Mei Lanfang and Cheng Yanqiu managed to distance their male gender roles offstage from their onstage feminine personae and justify their own practice of female impersonation, that very discourse could also be mobilized to suppress nandan whose offstage gender presentations did not neatly meet social expectations. Although there is a scarcity of sources documenting the private lives of (possibly) closeted nandan, scattered information concerning such men appearing in Republican-era and early PRC sources lays bare a long-neglected dimension of modern nandan.

In a diary entry dated 16 June 1963, Xun Huisheng (1900–68), perhaps the most accomplished twentieth-century huadan (literally, “flowery dan,” a subcategory of the dan that generally portrays youthful, vivacious maids, hilarious prostitutes, or other types of young women from humble roots) of both bangzi (literally, “the clapper,” a popular northern folk genre of xiqu) and jingju, as well as a contemporary of Mei Lanfang and Cheng Yanqiu, provided students of dan roles with some firsthand instruction. This particular entry, which was posthumously published in 1980 and entitled “Yao nuli suzao renwu” [Must make efforts to construct characters], allows us to scrutinize critically Xun’s understanding of how nandan players construct their stage roles. On how to play female characters in xiqu efficiently, Xun instructed as follows (which, due to the significance of the text, I quote at length):

Especially for those who play dan roles, they must present female characteristics at every moment and in every movement. . . . No matter whether you position your lateral body toward the audience or face them squarely, and no matter if you sit or stand, you must constantly radiate allure, creating a coherent image of a woman. . . . In the past, master performers who played female roles were generally men. On the stage, he acted entirely like a woman; [once] paying attention to this, he kept his presentation of female characteristics from beginning to end. . . . Nowadays, most female-role specialists are women. Some individual dan players hence think that [because] they are women themselves, as long as they know the lines and learn a few conventionalized movements, they can do well onstage. As a result, their performances appear lackluster—every finger pointing and every movement all look like what they do in everyday life. While they may think this is acceptable, the audience finds it unengaging. [This is] because they fail to recognize that the customs of women from centuries or even millennia ago differ greatly from those of our female comrades today. Furthermore, performances onstage and movements in life are also considerably different. . . . Xiqu acting has a whole set of expressive means and conventionalized movements for enacting dan characters. . . . No matter whether you are a male player of female roles or a female actor of female roles, you should not present your real persona but need to enact histrionics.Footnote 49

To begin with, this passage, as it seems to me, was partly about the “origins” of the dan performance in xiqu. Xun evidently set his discussion of xiqu’s performance of the dan in a historical context. Although he acknowledged that by the time he wrote the diary women had constituted the majority of dan players, he reminded his readers of the ostensible fact that the artistry of dan roles in xiqu was established and conventionalized by female impersonators of the past, and female actors of female roles were said to arrive on the stage only after their male precursors standardized xiqu’s performances. In other words, nandan were suggested as orthodox and authoritative players of female roles, whereas female actors in xiqu were claimed to be merely trainees of an established tradition, rather than practitioners of a theatrical form that has been constantly renewed. Although the assertion that it was nandan that initiated and standardized the performances of dan roles is fundamental to our understanding of xiqu history today, this understanding appears to be imprecise either when one brings back the oft-neglected female performers before the High Qing era into a larger picture of xiqu history or when one closely examines Xun’s own acting career in the twentieth century.

In fact, the exclusive role that nandan played on legally sanctioned xiqu stages was only a phenomenon of fewer than one hundred and fifty years. Prior to the advent of the Qing prohibitions on female actors, female performers existed in large numbers. In addition, the stagecraft of male actors and that of their female counterparts have been mutually referential since the late nineteenth century.Footnote 50 That is to say, neither bangzi nor jingju, the two theatrical genres in which Xun was versed, developed completely independent of the influence of those female actors. Born in 1900, Xun Huisheng was first trained as a bangzi actor in Tianjin, where all-female troupes prospered in the city’s foreign concessions; by the mid-1910s, when Xun turned to jingju to pursue a more lucrative career, the popular jingju nüdan such as Liu Xikui and Xian Lingzhi had already become fearsome rivals of nandan,Footnote 51 not to mention that superlative nüdan continued to proliferate during the following decades of the Republican era. In other words, during the bulk, if not the entirety, of Xun Huisheng’s career, Xun’s own artistry of dan roles had both influenced and been influenced by those of his rival dan players of both genders. Hence, the assertion that nandan single-handedly initiated and normalized xiqu’s performance of dan roles was a result of the gross negligence of the contribution to xiqu of nüdan from various historical periods.

However, what perhaps deserves more scrutiny than Xun’s underestimation of nüdan’s historical contribution to xiqu is his distinction between female characters on the xiqu stage and women’s “real” personae in everyday life. On the one hand, Xun applauded the master nandan players for consistently acting like women onstage.Footnote 52 On the other hand, Xun complained that some female performers appeared “lackluster” in their embodiment of women onstage.Footnote 53 To clarify his point, Xun stressed the differences between female dramatic characters in xiqu and the “female comrades” he encountered in everyday life, and their differences can be attributed to three crucial factors: first, the customs of women in antiquity are a far cry from those of women living in modern times;Footnote 54 second, theatrical acting, or what he referred to as “enact[ing] histrionics,” and everyday performance are different because xiqu acting is said to rely upon a whole set of performance methods and conventions; and third, a superb dan player must constantly “present female characteristics,” “radiate allure,” and keep their onstage performance of femininity consistent, in order to create “a coherent image of a woman,”Footnote 55 and therefore the consistency and intensity of a skillful dan actor’s performance of femininity also appear to make a well-constructed female dramatic character differentiate itself from a woman in everyday life.

The reasons that Xun gave to uphold his distinction between xiqu’s female characters and women’s “real” personae are worth close scrutiny. It should be noted that trying to make a distinction between the theatrical world and everyday life is one thing, but attempting to distinguish a female role specialist’s performance of femininity onstage from that of a “real” woman in daily life is another. Even if one can always consider the boundary of the stage a material borderline that separates the theatrical from the mundane,Footnote 56 the physical limit of the stage has never been an effective barrier that prevents the circulation of femininity between players of the dan and women in everyday life. For instance, Mei Lanfang’s adoption of the hairdos and clothing that were fashionable among youthful women contributed significantly to his triumphant performances.Footnote 57 According to Fu Zhifang, the second wife of Mei, the nandan often wore the posh clothing of his first wife, Wang Minghua, for his “contemporary-costume new plays” in the 1910s and later tried on her dresses for his other productions after Fu and Mei were married in 1921.Footnote 58 Throughout the years, Mei was said to pay keen attention to women’s fashions and repeatedly refashion his theatrical costume and hairstyles to cater to the tastes of the theatregoing population (which included a heap of women).Footnote 59 While Mei may insist that what he enacted onstage were “conventionalized” and “formalized” women, his enticing enactment of women surely came of his active participation in the circulation of renewed codes of femininity (as partly signified by culturally susceptible forms that decorated the exterior of the female body, such as hairdos, makeup, and clothing).

Despite the dynamic circulation of codes of femininity between players of the dan and biological women, Xun Huisheng nevertheless demanded that a masterful performer of female roles must “present female characteristics at every moment” and enact a coherent, consistent image of a woman, implying that what dan players presented onstage were characteristics and/or images of women rather than “real” women themselves. For Xun, the distinction between image and the real seemed to be of particular importance to the contemporary stage of xiqu, given the fact that most contemporary female-role players were biological women, who may conflate image and the real by extending their “real” femininity onto the stage. While this conflation was thought potentially to make a nüdan’s stage performance less efficient, it was believed to pose a problem for nandan practitioners as well. Xun continued his diary entry by alluding to a fraction of nandan players who went “astray” in their everyday life:

In the past, I observed certain actors (who also played dan roles) not only enacting histrionics onstage but also displaying similar behavior in private; while on the stage he made feminine postures, offstage he was also feminine and effeminate. This is a “pretense,” which is utterly unrelated to the way we [as reputable nandan players] approach theatre.Footnote 60

Once again, by calling a dan player’s construction of female roles “enacting histrionics,” Xun subscribed to the discourse of xiqu “aestheticism” and therefore affirmed the supposed artificial nature within nandan’s performances of femininity. Because of the implications of the idea of “artistic” femininity, Xun was able to further accuse those nandan players who presented socially feminine bodies offstage of blurring the necessary distinction between image and the real. By distancing himself and other reputable female impersonators from those nandan whose offstage gender performances were at odds with social expectations, Xun questioned the respectability of those who conducted a purportedly eccentric style of life. And his dismissal of those actors was predicated upon the belief that their offstage performances of femininity were in essence “a pretense,” a result of concealing the performers’ “real” male gender roles and of suppressing what he took to be their naturally given masculinity.

Although Xun Huisheng’s stance toward the possibly closeted actors was overtly hostile, his account nevertheless disclosed a marginalized group of nandan actors whose existence suggested that modern nandan was by no means a coherent entity/identity. The recent publication of the collection of Xun’s extant Republican-era diary entries helped me to identify some of the nandan players Xun referenced in the passage above. In an entry dated 2 June 1930—the day prior to the burial of Li Shuqing, the deceased wife of nandan player Shang Xiaoyun (1900–76)—Xun documented two nandan players in a deprecating tone. As the family of the deceased woman as well as their relatives and friends burned joss paper and walked through various areas in the southern part of Beijing, Xiao Cuihua and Zhu Qinxin, who were among the people coming to express condolences, “walked side by side and intimately held each other’s hands, causing everyone to look askance.”Footnote 61 Despite this, “the two cheerfully conversed with their acquaintances along the way [as if there was nothing inappropriate].”Footnote 62

While Xiao Cuihua (aka Yu Lianquan, 1900–67) specialized in huadan and was a major rival of Xun, Zhu Qinxin (1901–61) excelled in both qingyi (literally, “the blue robe,” a major subtype of the dan, which generally depicts virtuous and noble women and specializes in singing) and huadan, and they both were highly talented jingju actors of the age. In addition to Xun’s account, other sources from the Republican era also suggested that the two performers had acted against social expectations of how a nandan should behave in everyday life. It is rumored that Zhu Qinxin’s career was greatly advanced by the patronage of Cheng Ke, a bureaucrat who held such important posts as the minister of justice and mayor of Tianjin. Some sources even insinuated that the relationship may have been sexual.Footnote 63 Besides, a Tianjin-based tabloid once reported that a young gentleman strongly resembling Zhu Qinxin was diagnosed with a sexually transmitted disease and alluded that the man’s infection resulted from having receptive anal sex with other men.Footnote 64 This sensational story created quite a media hullabaloo. In response, Zhu categorically denied the tabloid’s claims and filed a defamation lawsuit.Footnote 65

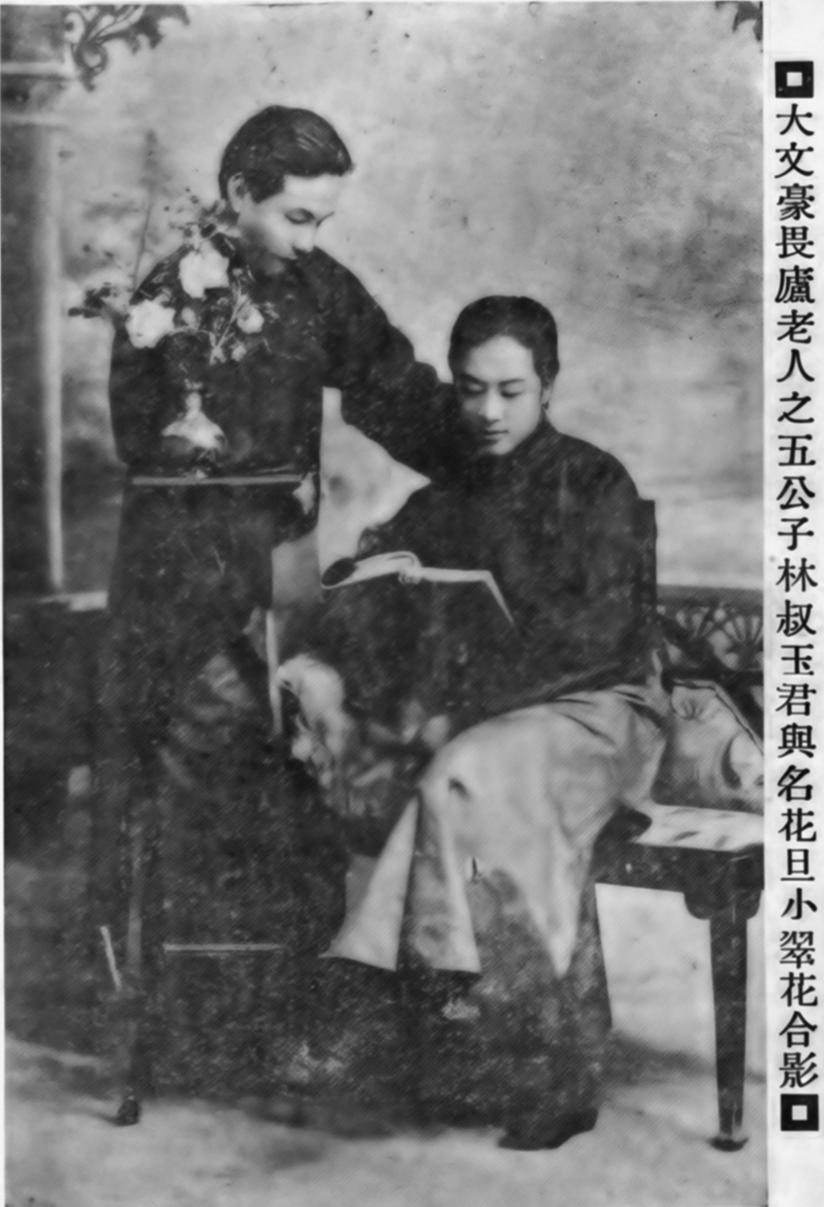

Likewise, other sources documenting the offstage life of Xiao Cuihua also challenged social expectations. For instance, a photographic image (Fig. 3) published in Shanghai huabao [Pictorial Shanghai] foregrounds the intimate relationship between Xiao Cuihua and Lin Shuyu (1899–?), a theatre enthusiast also known as Lin Lu, son of renowned literary figure Lin Shu (1852–1924). Lin Shuyu, in his teenage years, developed a keen interest in watching xiqu performances and interacting with xiqu actors, much to the disapproval of his father, who accused him of neglecting his professional career, wife, and children.Footnote 66 In this particular photograph, Xiao Cuihua leans toward Lin Shuyu, who gazes affectionately at him while embracing the actor from behind, suggesting their close bond. Such a photographic portrayal of nandan in their offstage lives is exceptionally rare during the Republican era. Typically, such photographs portrayed nandan actors primarily as husbands, fathers, and civilized Republican male citizens, often underscoring their masculinity and heterosexuality.Footnote 67 In addition, an author under the pen name “Bai Hutong” reported in Shanghai’s Dongfang ribao [Oriental daily] that Xiao Cuihua assumed a “feminine persona” (nüshen, literally, “the female body”) when interacting offstage. According to the author, the nandan radiated the “aura of the dan” (danqi) even outside of the theatre, dressing in a pink checkered shirt and having an explicit “feminine voice” (niangniang qiang). Describing the actor’s offstage persona as “bizarre,” the author accused Xiao Cuihua of “lacking self-discipline” because “the age of siyu is not comparable to the present day.”Footnote 68

Figure 3. Nandan Xiao Cuihua (right) and theatre enthusiast Lin Shuyu (left). The Chinese caption reads: “Lin Shuyu, fifth child of the great literary figure Weilu Laoren [aka Lin Shu], and the famed huadan Xiao Cuihua took a photograph together.” Shanghai huabao [Pictorial Shanghai], 15 January 1927, 2.

Xun’s account, along with the other early Republican sources, indicated that modern nandan’s ostensibly flexible presentations of gender were a highly regulatory practice. Negative representations, in one way or another, stigmatized those nandan who appeared “bizarre” in their life. Displays of intimacy between men, as shown in Xun’s diary entry, were subjected to derision and ridicule, and the Tianjin tabloid depicted the male same-sex bond as both a lascivious lifestyle and a means of disease transmission. Also, it is noteworthy that both Xun Huisheng and the Dongfang ribao author made accusations against the nandan in question by referring to temporality. For Bai Hutong, the bizarreness of Xiao Cuihua’s gender performance offstage was rooted in the perception that the nandan continued a practice that belonged to a bygone era. Likewise, despite his acknowledgment of their existence, Xun made it clear that his encounters with these (in his view) heretical practitioners occurred only “in the past.” In the context of the Seventeen Years (1949–66), the term “the past” (guoqu) did not simply refer to a previous time but also carried a moral judgment. When a Seventeen Year person spoke of “the past,” he, as an informant for the younger generation, was compelled to assume the role of a poignant social critic. Conventionally, “the past” referred to the period prior to the triumph of the Communist Revolution in 1949, signifying a period of history when something deemed obsolete, corrupt, and reactionary prevailed. Hence, as a species in the “past,” these “aberrant” nandan self-evidently necessitated political correction.

Coda

In his 1962 memoir, Xiao Cuihua narrated a thought-provoking story of how his master Tian Guifeng (1866–1931) perfected his performance of the dan:

All servants in Mr. Tian’s house were women, and each month he hired a new servant after dismissing an old one. Some of his servants were older, while others were extremely young, and they all had distinct backgrounds. I initially did not understand why he changed his servants so frequently. Later, I came to know that by doing so, Mr. Tian could observe the traits of all types of women and incorporate them into his performances (in his daily life, Mr. Tian paid keen attention to women’s behaviors). This inspired me greatly, which taught me to observe closely the everyday from multiple perspectives and absorb various nutrients from the mundane life to enrich my own performances.Footnote 69

Instead of postulating an essential distinction between the “artistic” and the “mundane,” Xiao Cuihua’s words tellingly showed that the nandan Tian Guifeng perfected his performances by closely imitating the behaviors of biological women. Xiao Cuihua’s account suggested that even if some part of nandan’s performances stems from xiqu’s highly trained study of artistic conventions, the other part of their theatre inevitably takes an “imitating imitated”Footnote 70 approach to performing what exists in real life as the feminine. If gender is indeed itself a performance and perpetually enacted as a theatrical demonstration,Footnote 71 the gender of the dan—both male and female players of female roles included—involves at least three layers of performance: learned traits and expressions; artistic symbols and conventions that dictate these behaviors as feminine; and a daily (re)performance of these learned behaviors that ensures a compelling performance both onstage and off. These nuanced gender performances of the dan challenge the conventional Republican understanding of nandan’s femininity as purely “artistic,” acknowledging the potential for closeted nandan players to express their femininity outside the confines of the theatre.