Introduction

In 2016 and 2017, more than 465 000 refugees attempted to reach European borders by crossing the Mediterranean Sea (United Nations Refugee Agency, 2019). In response to such events, over the years European governments have taken severe measures to address immigration. This includes encouraging civil society organizations, such as community sport organizations, to contribute to solve the refugee crisis. Voluntary sport organizations and community sport clubs are increasingly expected to work towards implementing political objectives (e.g. Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Eime and Westerbeek2019; Spaaij et al., Reference Spaaij, Magee, Farquharson, Gorman, Jeanes, Lusher and Storr2018).

In the Nordic context, integration has traditionally been viewed as a public responsibility (Sveen et al., Reference Sveen, Anthun, Batt-Rawden and Tingvold2022). However in recent years, governments have increasingly commissioned voluntary stakeholders, such as national sport confederations, to direct their activities towards underrepresented and underprivileged groups based on the assumption that sport activity can ameliorate integration and health (e.g. Aggestål & Fahlén, Reference Aggestål and Fahlén2015). Several studies (e.g. Skille, Reference Skille2010, Reference Skille2011; Stenling & Fahlén, Reference Stenling and Fahlén2009) have aimed to explore how sport clubs respond to implementing public health policies, and a common theme running through this literature is that of institutional conflicts between contrasting logics framing the structures and actions of clubs. For example, Stenling and Fahlén (Reference Stenling and Fahlén2009) showed how sport clubs in Sweden find themselves in a struggle between logics of mass sport participation (known as sport-for-all), competitive elite sport, and commercial sport. The stated aims of the clubs were often in accordance with the sport-for-all logic, but there were few organizational measures directed towards accomplishing this. However, what they did find were sports committees, talent programmes, and marketing and sponsorship groups informed by logics of competition or commercialism. Similarly, Skille (Reference Skille2010, Reference Skille2011) maintains that competitiveness is the overriding convention in Scandinavian club sport and that sport-for-all ambitions are hard to realize because competitiveness requires the opposite: elitism, selection and exclusion. Such conventions may in turn lead to increased professionalization (e.g. Gammelsæter et al., Reference Gammelsæter, Herskedal and Egilsson2023; Nagel et al., Reference Nagel, Schlesinger, Bayle and Giauque2015; Seippel, Reference Seippel2019).

Based on a study of Norwegian voluntary sport clubs (VSC) and some local stakeholders (schools, refugee reception centres, city authorities) they cooperate with, this paper explores whether VSCs are a convenient measure for including refugees in society. The clubs in the study were either voluntary football clubs or the football section of multi-sport clubs. The paper is informed by the following two research questions: what expectations of refugee inclusion initiatives do local public stakeholders hold towards VSCs and, how do the clubs grapple with pursuing non-sport and sport objectives and systems simultaneously? Based on a unique data set, comprising both sport clubs and public refugee services, the paper adds to a growing critical research body questioning the role of VSCs as executors of public inclusion policies (e.g. Dowling, Reference Dowling2020; Nesse & Hovden, Reference Nesse and Hovden2023; Spaaij et al., Reference Spaaij, Magee, Farquharson, Gorman, Jeanes, Lusher and Storr2018). Conceptually, it contributes to our understanding of how appealing and compatible logics at the ideational (and political) level may run into mismatching practices. The paper is structured as follows. First, we provide an understanding of the context of Norwegian sport and refugee policies before we review the literature regarding inclusion of refugees in voluntary sport organizations. We then embark on the theoretical framework of institutional logics that guides the analysis of the data. Third, we outline the methods utilized before moving on to the results and discussion sections. Lastly, we conclude with suggestions for future research.

Context and Terms

Norwegian sport is organized under the Norwegian Olympic and Paralympic Committee and Confederation of Sports (NIF). NIF has the sole responsibility for organized sport in Norway, and in 2019, at the time of the study, NIF consisted of 55 national sports federations and 17 district confederations, altogether consisting of almost 8 000 sports clubs and about 1,9 million memberships (Norges idrettsforbund, 2019). Norway had 5,3 million inhabitants.

The Football Association of Norway (NFF) is the biggest sport federation in Norway. NFF is organized in 18 districts. In 2019 it comprised more than 370 000 members representing approximately 1700 clubs that varied greatly in terms of location, size, number of hired staff and financial state (Norges Fotballforbund, 2019). Although it can be argued that Scandinavian football is an amalgam of voluntarism and commercialism (Andersson & Carlsson, Reference Andersson and Carlsson2009), all clubs affiliated with NFF are voluntary entities, meaning that they are democratic associations formed by people with a mutual interest in football (Gammelsæter & Jakobsen, Reference Gammelsæter and Jakobsen2008). Besides engaging in the sport activities, a substantial amount of energy is spent on building and maintaining club facilities, often the property of the club. The recruitment and organization of volunteer members as well as securing economic funding and access to facilities are crucial (Seippel, Reference Seippel2019). The clubs must conform to the goals and values of NIF and NFF, the main vision of NFF being “the joy of football, possibilities and challenges for all” (Norges Fotballforbund, 2016).

Whereas the clubs are open for all, refugees and asylum seekers are, for language, cultural, economic, and legal reasons, often not in a position to engage with the clubs (Mohammadi, Reference Mohammadi2019; Nesse & Hovden, Reference Nesse and Hovden2023; Spaaij, Reference Spaaij2013). This means that the clubs must reach out to these groups in specific ways and develop an understanding of their status and rights, and of the support system and roles of public and voluntary sector stakeholders.Footnote 1

The status of asylum seeker is given to persons that has applied for protection in Norway while waiting for the application to be finally decided. Meanwhile, the person lives in a reception centre under the auspices of the Norwegian Directorate for Immigration (UDI). An asylum seeker whose application receives a positive answer gets a residence permit as refugee. The person will then move from the reception centre to a municipality that has agreed to settle her/him for the next five years. The newly settled refugee now has certain rights and obligations, for example a mandatory two-year introductory programme (three years in special occasions). Whilst participating in the introductory programme, economic support is provided by a variety of municipal and state bodies. Sport clubs that respond to invitations to working on inclusion and integration are required to navigate this system of public policies, politics, and priorities and to collaborate with the other stakeholders involved.

Literature Review

A growing body of publications have investigated the use of sport for the inclusion of refugees and forced migrants (Spaaij et al., Reference Spaaij, Broerse, Oxford, Luguetti, McLachlan, McDonald, Klepac, Lymbery, Bishara and Pankowiak2019). Perhaps as a reflection of the 2015–2017 migration crisis, and parallel to political and policy concerns, published research on the use of sport for the inclusion of refugees and forced migrants has surged, whereas the literature on refugees tended to focus on health and social and judicial matters (Amara et al., Reference Amara, Aquilina, Argent, Betzer-Tayar, Coalter, Green and Taylor2005), the main themes in the current literature are integration, social inclusion, and barriers and facilitators to participation (Spaaij et al., Reference Spaaij, Broerse, Oxford, Luguetti, McLachlan, McDonald, Klepac, Lymbery, Bishara and Pankowiak2019).

Several studies have investigated how sport clubs are engaged to facilitate community inclusion among refugees. Many of these address sport clubs set up with the specific aim of targeting refugees (Baker-Lewton et al., Reference Baker-Lewton, Sonn, Vincent and Curnow2017; Doidge et al., Reference Doidge, Keech and Sandri2020; Dukic et al., Reference Dukic, McDonald and Spaaij2017; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Spaaij and Dukic2019; Michelini et al., Reference Michelini, Burrmann, Nobis, Tuchel and Schlesinger2018; Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Eime and Westerbeek2019; Stone, Reference Stone2018), while others study how ordinary VSCs respond to initiatives to integrate sport for refugees into their portfolio, alongside their regular activities (e.g. Burrmann et al., Reference Burrmann, Brandmann, Mutz and Zender2017; Dowling, Reference Dowling2020; Michelini et al., Reference Michelini, Burrmann, Nobis, Tuchel and Schlesinger2018; Stura, Reference Stura2019). Thus, one of the grand questions in this research is whether VSCs are convenient means to achieve refugee integration or if integration requires specific proactive club initiatives or special clubs set up for the purpose. VSCs have long attracted policy makers and sport associations and clubs have responded positively to authorities’ initiatives to set up integration programs, thus taking on the role of implementing political objectives (Stenling & Fahlén, Reference Stenling and Fahlén2016). The question is if this works, and if not, if it may work.

Based on a Delphi-study among Australian sport management academics and national sport organization managers, Robertson et al. (Reference Robertson, Eime and Westerbeek2019) concluded that as “most community sports organizations are primarily volunteer-based, they cannot be expected to extend beyond their core responsibilities and deliver on a range of other social issues outside the scope and resource capacity of the organization”. (p. 229). Van Haaften (Reference van Haaften2019), studying integration/segregation across diverse ethnic groups, concluded that voluntary football clubs, despite its broad outreach, have difficulties linking people with different ethnic backgrounds. Stura (Reference Stura2019), when studying inclusion of refugees into 15 Bavarian football clubs, found that a minority of clubs approached the refugees on their own, despite acknowledging their obligation to contribute to integration. When refugees happened to get inside the clubs, a decisive precondition for becoming part of the football team was meeting the team’s level of performance. Michelini et al. (Reference Michelini, Burrmann, Nobis, Tuchel and Schlesinger2018) set out to explore whether “organizational conditions of VSCs promote or hinder the implementation of sport activities for refugees?” (p. 23). Facing the migration crisis in 2015, the clubs in their study proved to quickly develop special offers, collaborating with reception centres, refugee camps, the Red Cross, municipalities and so on. The decision and implementation of the special offers were personalized. Individuals or small groups of influential club members took charge, however with board approval, acting in accordance with the club ethos of inclusion and integration. While Michelini et al. (Reference Michelini, Burrmann, Nobis, Tuchel and Schlesinger2018) say nothing about the persistence of the club offers they studied, Spaaij et al. (Reference Spaaij, Magee, Farquharson, Gorman, Jeanes, Lusher and Storr2018) found that in migrant clubs that demonstrated support for diversity work, the work was often haphazard and accidental. The clubs often failed to “systematically embed diversity into the fabric of the organization” (p. 293) because the initiatives relied on specific individuals, hardly surviving the service of these individuals. Nesse and Hovden (Reference Nesse and Hovden2023), interviewing top managers and board directors in 10 Norwegian football clubs found that integration effort was seen as extra work that required different and additional resources such as competence and organizational infrastructure: “most clubs translated their integration mandate as an additional mission for a football club. The responsibility to promote the integration of migrants was perceived as an external task put on them by the civil society.” (p. 362).

The Competing Logics Perspective

The reviewed body of literature highlights that while voluntary sport clubs are ascribed prominent social roles by the public and public authorities (e.g. Waardenburg & Nagel, Reference Waardenburg and Nagel2019), the empirical research pinpoints that fulfilling this role, at least regarding migration and refugee integration, does not happen automatically. On the contrary, special initiatives seem necessary and these tend to threaten or conflict with the core activities of the clubs. The voluntary clubs’ concern for their image, that is the expectations directed towards them from the outside, clashes with their cultures, “the tacit organizational understandings (e.g. assumptions, beliefs and values)” (Hatch & Schultz, Reference Hatch and Schultz2002, p. 996). In organizational institutionalism “the tacit organizational understandings” may be referred to as the institutional logic, which in Thornton and Ocasio’s (Reference Thornton and Ocasio2008) is “the socially constructed, historical patterns of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs and rules by which individuals produce and reproduce their material subsistence, organize time and space, and provide meaning to their social reality” (Thornton & Ocasio, Reference Thornton and Ocasio2008, p. 101). These patterns underpin social entities, such as VSCs which descriptively are independent organizations, formed on the basis of members’ sport interests, goals, ideas and engagement, and kept going by the members themselves while undertaking the necessary services, as they define them, to meet their goals, under the auspices of a democratically elected board (Thiel & Mayer, Reference Thiel and Mayer2009). However, the competing logics perspective holds that organizations, despite being rooted in its original raison d’être and historical patterns (Stinchcombe, Reference Stinchcombe1965), frequently face multiple logics that compete in guiding the action of key members in the organization (Lounsbury, Reference Lounsbury2007; Reay & Hinings, Reference Reay and Hinings2009). Hence, organizations, VSCs included, differ in their goals, identity and logic of procedures (e.g. Stenling & Fahlén, Reference Stenling and Fahlén2009) and frequently come to combine one or more institutional logics (e.g. Nowy et al., Reference Nowy, Feiler and Breuer2020).

The idea of institutional logics (cf. Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011; Lounsbury, Reference Lounsbury2007; Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012) emanates from a conception of society (Friedland & Alford, Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991, p. 240) as composed of interdependent institutions, all of which entail a specific institutionalized logic of what is good, right, and rational (Friedland & Alford, Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991, p. 240). Organizations are seen as embedded in this inter-institutional system, and as such exposed to sets of institutional logics, networks of actors, and flows of resources. For Friedland and Alford (Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991) the “potentially contradictory interinstitutional system” of “the capitalist West” (p. 232) comprised the bureaucratic state, democracy, the market, the nuclear family, and the Christian religion. Thornton et al. (Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012) added community to the system. Whilst surely community based, (Gammelsæter, Reference Gammelsæter2020) proposes sport can meaningfully be conceptualized as an institution too. Its pyramidal structure, membership model, tournaments, trophies, awards, the autonomy of its organizations, etc., have not been imposed on it from the outside, but is developed historically bottom-up from the community club level to the international federation. (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta and Lounsbury2011, p. 317).

Simultaneously, sport’s institutional environment exerts conflicting pressures on how sport should shape their organizational structure, how they should act, and what to believe (in) (Thiel & Mayer, Reference Thiel and Mayer2009). These pressures emanate among others from commercial and state logics (Gammelsæter, Reference Gammelsæter2020). The refugee crisis poses an example of the latter: VSCs are expected to deliver services that ameliorate refugees’ integration into society. Arguably, integration services may differ from offering sport participation or sport competition at elite level or in the local community. Furthermore, it is an example of how sport is valued for its many assumed positive externalities, counting inclusion/integration among keywords such as health, education, economic and community developments. Such imagined benefits translate into institutional logics that prescribe sport to shape its organization and actions to political outcomes (Stenling & Fahlén, Reference Stenling and Fahlén2016). Since sport depends much on the public purse, ignoring political expectation about what sport clubs should achieve is difficult, even if these prescriptions challenge the institutional logic of the sport club. The conflict is exacerbated by the fact that conflicting prescriptions shape the availability, value, and use of organizational resources (Bertels & Lawrence, Reference Bertels and Lawrence2016). If providing sport for its members and running special offers for refugees possibly accommodate conflicting logics, epitomized in how revenues and personnel are achieved and used, it is relevant to ask how sport clubs incorporate non-sport aims into their daily activities. Do their members mobilize around public policy issues, such as bettering cultural integration, within the club context, notwithstanding the club’s roots and performance logic?

Research Methods

The data presented in this paper were collected from the “Inclusion of Refugees in Norwegian Football Clubs” research project, running between 2017 and 2019. The aim of the project was to investigate how Norwegian football clubs dealt with the increased demand of working with inclusion of refugees. The project sought information concerning the impact of football club-driven sport activities for refugees in host communities; the strengths and weaknesses in the relation between relevant stakeholders; the institutional determinants for success; and the ‘best practices’, methodologies, and/or instruments that could be replicated.

Data Collection

The researchers selected three NFF district confederations in which to collect data. Districts were selected in cooperation with NFF, who provided contact details of district representatives. All case districts had experienced an increase in refugees and were thus familiar with issues relating to inclusion of this group.

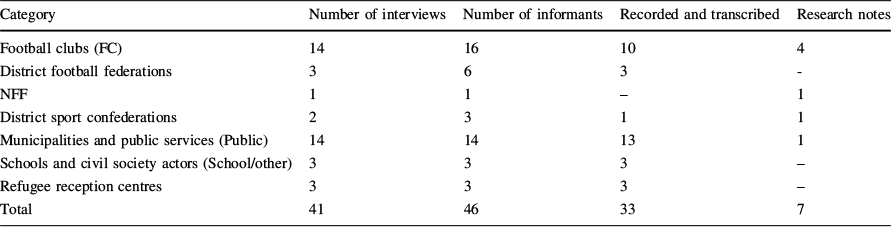

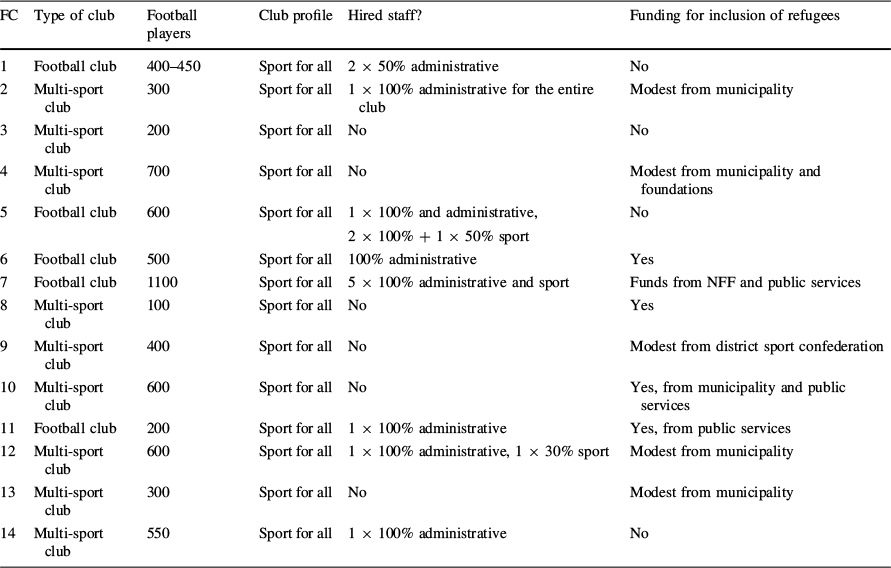

The study draws on data from 41 semi-structured in-depth interviews. As outlined in Table 1, interviews were conducted with representatives from the sport sector (clubs, NFF districts, the central administration of NFF and NIF districts), the public sector (municipalities and public refugee services, primary schools), and other civil society actors. Baseline data about the clubs participating in the study are found in Table 2. The informants in all three case regions were identified both through purposive and snowball sampling. A team of researchers travelled to the case districts to collect the data. Most of the interviews were with one informant, but in a few cases, there were two, typically when in a club or a municipality office two people were equally interested in taking part of the study. We are aware of the risk that one colleague might influence the other, skewing the replies in a positive way, but compared to the others we did not find these interviews peculiar. Twenty of the interviews were conducted by two researchers, one asking the questions, the other taking notes. Twenty-one interviews were conducted by one researcher alone. The reason for this was pragmatic, adapting the schedule to the availability of the interviewees. Upon ensuring consent from the informants, 33 of the interviews where recorded and thereafter transcribed. Again, for pragmatic reasons, eight interviews had to be conducted via telephone by one researcher. Data from these come in the form of research notes. The interviews lasted between 40 and 90 min.

Table 1 Overview of interviews and informants

|

Category |

Number of interviews |

Number of informants |

Recorded and transcribed |

Research notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Football clubs (FC) |

14 |

16 |

10 |

4 |

|

District football federations |

3 |

6 |

3 |

- |

|

NFF |

1 |

1 |

– |

1 |

|

District sport confederations |

2 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

Municipalities and public services (Public) |

14 |

14 |

13 |

1 |

|

Schools and civil society actors (School/other) |

3 |

3 |

3 |

– |

|

Refugee reception centres |

3 |

3 |

3 |

– |

|

Total |

41 |

46 |

33 |

7 |

Table 2 Baseline information about the clubs in the study

|

FC |

Type of club |

Football players |

Club profile |

Hired staff? |

Funding for inclusion of refugees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Football club |

400–450 |

Sport for all |

2 × 50% administrative |

No |

|

2 |

Multi-sport club |

300 |

Sport for all |

1 × 100% administrative for the entire club |

Modest from municipality |

|

3 |

Multi-sport club |

200 |

Sport for all |

No |

No |

|

4 |

Multi-sport club |

700 |

Sport for all |

No |

Modest from municipality and foundations |

|

5 |

Football club |

600 |

Sport for all |

1 × 100% and administrative, 2 × 100% + 1 × 50% sport |

No |

|

6 |

Football club |

500 |

Sport for all |

100% administrative |

Yes |

|

7 |

Football club |

1100 |

Sport for all |

5 × 100% administrative and sport |

Funds from NFF and public services |

|

8 |

Multi-sport club |

100 |

Sport for all |

No |

Yes |

|

9 |

Multi-sport club |

400 |

Sport for all |

No |

Modest from district sport confederation |

|

10 |

Multi-sport club |

600 |

Sport for all |

No |

Yes, from municipality and public services |

|

11 |

Football club |

200 |

Sport for all |

1 × 100% administrative |

Yes, from public services |

|

12 |

Multi-sport club |

600 |

Sport for all |

1 × 100% administrative, 1 × 30% sport |

Modest from municipality |

|

13 |

Multi-sport club |

300 |

Sport for all |

No |

Modest from municipality |

|

14 |

Multi-sport club |

550 |

Sport for all |

1 × 100% administrative |

No |

Three different interview guides were developed, adapted to the institution the informant represented, allowing for flexibility regarding the informant’s background, experience, and status (Denzin & Lincoln, Reference Denzin and Lincoln2011). The semi-structured interview questions were designed by the research group to elicit data regarding how, from the perspectives of the institution they represented, the informants dealt with inclusion and what they saw as challenges and opportunities. Five focus areas of the interview guides were identified, based on a review of previous research literature: systems and strategies for inclusion; cooperation between stakeholders; challenges related to inclusion of refugees; actions and activities initiated by the club; and what was seen to be good inclusion practices.

Data Analyses

The interview data were transferred and coded in Excel. In the analysis of the qualitative data, systematic text condensation was applied (Malterud, Reference Malterud2012). The analytical procedure of systematic text condensation consists of four steps: total impression of all answers and identifying preliminary themes; identifying and sorting meaning units (the words and sentences that holds the same meaning); condensation into code groups; and synthesizing the condensed data into descriptions and concepts (Malterud, Reference Malterud2012). In this study, each member of the research team first studied the written transcripts of the interviews individually to get an overview of the data material and to identify preliminary themes. Thereafter, the researchers discussed the preliminary themes before identifying and sorting meaning units that were further classified into themes and code groups. The following themes were identified: systems and strategies for inclusion; barriers for inclusion of refugees in the football club; funding of refugee inclusion projects in the clubs; and cooperation between stakeholders. In subsequent meetings, the researchers synthesized the data material and identified illustrative quotations and descriptions. As a delivery from the project, a final report was produced for NFF (anonymised for review). In the process of writing this paper, the data were revisited, re-coded by the first author, and meanings discussed between the authors.

Research Ethics

In the presentation of the data material all identifiable features such as organizations and locations are anonymised. We reveal the job position of the interviewee where relevant. Illustrative quotes were identified and translated from the Norwegian transcripts to English by the first author. The study procedures were reported and approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data.

Findings

The aim of the paper was to 1) explore what expectations in terms of refugee inclusion local stakeholders directed towards voluntary football clubs, and 2) how clubs grapple with pursuing non-sport and sport objectives simultaneously.

Expectations from Local Stakeholders

In general, there is an understanding from local stakeholders surrounding the football clubs (FC) that the clubs represent opportunities and therefore responsibilities in engaging in refugee inclusion. In the interviews with representatives from municipalities this was evident, as the following examples show:

We expect the FCs to be open in receiving the refugees. We expect a will and an interest in cooperating. And we expect them to be open to feedback from those who work with refugees daily (Refugee service representative)

We do have expectations to the FCs. They do an important job in terms of proving liveable conditions for children and youth in the municipality (Municipality representative)

There is an expectation that the FCs work with inclusion because it can help to fill the gap between those who have resources and those who do not (Primary school introductory class teacher)

The expectations were also linked to practical issues. Several municipality representatives pointed out that since many sport activities took place in the evening and their own office hours ended at 4 pm they were depending on help from sport clubs and other voluntary organizations. Furthermore, expectations were particularly high when linked to grant support, which voluntary organizations could apply for through municipalities or other state agencies:

We set the terms for grant support, and for FCs or other stakeholders to receive these grants. ‘Inclusion’ as well as ‘prevention of radicalization’ must be emphasized. That is an expectation. (Refugee service representative)

Representatives from the refugee reception centres were less outspoken about the expectations towards the voluntary sector, although they acknowledged FCs could be important actors in refugee inclusion.

The FC representatives accepted the expectations provided by local stakeholders and NFF. This was especially evident in FCs in municipalities with refugee reception centres, as these statements show:

We are experiencing greater 'pressure' from NFF than from the district (...)NFF wants us to take responsibility for the integration [of refugees]. The expectations towards us are perhaps greater than towards others. I think that football has a special responsibility because it is the biggest sport—for both boys and girls. NFF’s strategy is that football should be open to everyone, and in a way, it is up to us to take care of that (leader, FC1)

We feel that it is expected that we should work on this topic, both from the local community and from parts of the club. It is not problematic for us. We understand it (leader, FC5)

If there are expectations [from local stakeholders] I think they are related to what we do [in terms of refugee inclusion]. So, there are expectations connected to the success of the projects we take on. To us, it seems like it is more a wish than an expectation from the municipality that we shall focus on refugee inclusion (leader, FC11)

The interviewees representing FCs frequently stated that they believed that sport in general and football in particular had a unique potential to unite people and therefore was considered an appropriate tool in refugee inclusion. Most of the clubs stated that an overall aim, in accordance with the vision of NFF, was to be a club for all. As one football club leader stated: “our goal is to be a club for everyone, and then everyone must be welcome. This includes these groups.” (FC1).

FCs Grappling with Pursuing Non-Sport and Sport Objectives and Systems Simultaneously

While club representatives seemed to accept that their football clubs’ aims were consistent with the anticipations directed at them, it also appeared that there was an amalgam of conflicts or challenges that emerged when the clubs set out to substantiate the claims. One of these regarded the clubs’ financial resource capabilities of prioritizing refugee inclusion and the lack of financial support for this work. As disclosed in the following three interviews with FCs of relatively similar size and administrative resources:

The most challenging thing about the expectations is that the refugee services and the municipal apparatus become overwhelmed with excitement when they see that the projects are working, and they expect us to do more and more. And then we apply for funds, but we don't get any money (leader, FC5)

The public sector should listen to our needs, so that they get an insight into our daily operations. The municipality expects us to provide an arena for refugee inclusion, and then they pass the ball on to the voluntary sector without providing any funds (leader, FC1)

The expectations that the FC should contribute with its own funds are a bit too high. This work should not be added to the club's budget but be something that the FCs received subsidies for (leader, FC14)

The frustrations of the FCs aligned with what other stakeholders experienced. In the interviews it became clear that it was challenging to facilitate for inter-organizational cooperation as different actors were scattered across different areas of refugee inclusion. As the head of a municipal activity and inclusion department (M1) stated:

It is not clear who is responsible for what. Many public actors are working with the same groups—minor refugees, refugee reception centres etc.—but there is a lack of coordination regarding who does what. Maybe it is difficult because there is so much diversity within the target group?

Despite challenges in coordinating inclusion work, the public stakeholders in our study seemed eager to cooperate with sport clubs in general and FCs in particular, as they considered sport activities to be an arena for integrating refugees. In particular, the representatives from the refugee reception centres were emphasizing the importance of cooperating with the sport clubs as refugees scattered across reception centres are in a particularly vulnerable position and thus in need of distractions and alternative activities. However, some FC representatives nurtured a feeling of being somewhat “exploited” by the local refugee reception centres as they had experienced that the centres were sending refugees to organized training sessions without further backing. Occasionally, players were abruptly returned or relocated to different municipalities and therefore the FCs did not consider focussing on the inclusion of these players as a sustainable solution for the club. The representatives from the refugee reception centres understood and acknowledged the frustrations of the FCs regarding this uncertainty but nevertheless underlined the importance of providing opportunities within the voluntary sport system for people in asylum, and especially for unaccompanied minors. As one staff member working with social environment and activities at a reception centre (RC2) said:

It is difficult for the sport club to relate to these boys [unaccompanied minors] because they are so unstable. The boys do not understand that if they are not there regularly during practice, they can't play matches. They don't understand how organised this is. In addition, they are struggling. Their days are so different from that of a Norwegian youth. They can have bad days when it is difficult to be part of a team (…) The clubs are trying to facilitate, but essentially it is challenging to facilitate for these boys.

A general finding is that clubs lack knowledge about and experiences from inclusion of refugees. This was evident in the interviews with the FC representatives where many did not reflect upon what characterized refugees as a target group. This was especially true for FCs that did not have refugee reception centres in their proximity. Several FC representatives stated that there seemed to be little interest in this part of inclusion work within the football community in general. Consequently, refugee inclusion very often became a ‘privatized’ service conducted by devoted individuals and most of the interviewees expressed that there were no formal systems for inclusion in the club. Taken together, the lack of club systems and the dependency on individuals made the inclusion work in the FCs ad hoc.

Discussion

It seems quite clear from the interviewees that clubs are faced by a powerful logic in their political surroundings saying that voluntary sport clubs represent an obvious opportunity for inclusion of refugees, for several reasons: they espouse non-discriminatory access to sport activities; their activities are after-office hours for most public administrators, and therefore a cheap alternative to public service 24/7; and lastly, they offer activities that may distract refugees experiencing an otherwise dull lifeworld characterized by much waiting and inactivity. Club managers in part associate with this logic, they “understand” it, notably because their clubs “are open to everyone”. However, they do it with concerns that there are many costs involved that are not covered by the authorities and that developing offers for refugees threatens to encroach on the clubs’ ordinary sport activities.

The latter concerns the core institutional logic of the clubs and sometimes leads to frustration, bordering on a feeling of being “exploited”. The practice of offering welcome distraction to refugee youth turns out to represent unwelcome distraction for coaches working to put together stable teams and training conditions. The tacit in-club understanding is that the clubs’ primary concern is to serve those members that voluntarily come to the club to practice football, often with a sporting development and performance ambition. Unless refugees meet this functional logic where “open to everyone” means “formal equal access” (cf. Nesse & Hovden, Reference Nesse and Hovden2023, p. 362) and regular training and games, the clubs find integration work difficult. Clubs do normally not campaign to reach out to new members, hence the few individuals that happen to devote to refugee inclusion are special. In short, clubs expect to go on with their ordinary business seeing refugee work as a side activity that is premised on excess voluntary engagement, and capacities and resources provided by the authorities. In the light that even the public stakeholders experience huge inter-organizational coordination costs it makes sense that voluntary clubs find inclusion and integration costly in terms of time and competence.

Two logics of inclusion seemingly do link up around the idea of “open for everyone”. One is functional, passively welcoming everyone that are keen and resourced to play football, the other is moral and proactive (Nesse & Hovden, Reference Nesse and Hovden2023), expecting clubs to reach out to groups of people that lack resources and cultural capabilities in their new context. However, the link is fragile. Most clubs are formed around a mission that is unconnected to irregular waves of migrants and consists of volunteers who contribute to the club in their spare time, engaging in sport themselves or in their children’s sport (for instance demonstrated in Einolf, Reference Einolf2018). Following Breuer et al. (Reference Breuer, Feiler, Llopis-Goig, Elmose-Østerlund, Bürgi, Claes, Gebert, Gocłowska, Ibsen and Lamprecht2017), sports clubs in Europe have relatively small revenues, and their main challenges are the financial situation, the recruitment and retainment of members/volunteers and availability of facilities (Meijeren et al., Reference Meijeren, Lubbers and Scheepers2023). Against this background, it is reasonable to believe that often their capacity to act is limited, whilst at the same time they face expectations from political authorities, which, at the end of the day, is the hand that feeds them. The link over “open to everyone” is veiling competing logics that is hard to unite, unless they are structurally separated. It shines through the responses from many club representatives that they find it unreasonable that the public sector expects volunteers to be responsible for making integration happen through their ordinary activities. Accordingly, to enable the clubs to build systematic club-driven structures (as opposed to driven by devoted volunteers) for the purpose, many club representatives request increased involvement from the public sector. However, as Seippel and Belbo (Reference Seippel and Belbo2021) point out about the Norwegian sport system at club level; despite advocating more grassroots-orientation than other European countries (Breuer et al., Reference Breuer, Feiler, Llopis-Goig, Elmose-Østerlund, Bürgi, Claes, Gebert, Gocłowska, Ibsen and Lamprecht2017), it is not designed for targeting special social groups with their needs and interests.

Our findings corroborate the findings of Nesse and Hovden (Reference Nesse and Hovden2023) on another sample of Norwegian clubs and lend support to the research of Spaaij et al. (Reference Spaaij, Magee, Farquharson, Gorman, Jeanes, Lusher and Storr2018) and Robertson et al. (Reference Robertson, Eime and Westerbeek2019) on Australian samples. Despite political expectation, ordinary voluntary sport clubs set up to facilitate sport in native communities are not fast-tracks to refugee integration. The logic sustaining their existence is different and at odds with the logic prescribing refugee integration through sport. However, this conclusion does not preclude pursuing a slow track: the initiation of temporary projects or own sections under the club’s ceiling, nor entire clubs directed towards animating refugee youth. For example, in this study, some clubs pursued such projects, relying heavily on competent individual volunteers that saw it as their primary task to facilitate activities for refugees. Nesse and Hovden (Reference Nesse and Hovden2023) also report on one club in which integration is the centre of attention, and similarly Doidge et al. (Reference Doidge, Keech and Sandri2020) studied a UK sports club that used table tennis to promote the active integration of refugees. In these cases, the participants seemingly do not carry a compatible sporting capital (experiences with organized sport), rather sport participation is a means for social inclusion and hence their primary aim, and therefore conflicting logics is less of an issue. However, these practices come with a caveat. If measures are set up outside the activities of the native community, how can they incorporate integration in the same native community? We think there is a real political dilemma here, between funding the clubs to employ or educate coaches/social workers with a specific liability to engage with refugees (and success being uncertain) and keeping public spending to a minimum in times when the reception of refugees is a contended political issue. A more apt response is perhaps to accept that the fast-track is unrealistic and that differentiation between services for youth refugees (own training groups) and native players is a slower but still more realistic track. Notably, this solution depends on adequate numbers of refugees with balanced age distribution so that meaningful training groups can be organized.

In terms of theoretical contribution, we think our findings show how organizations in the face of external pressure may express the compatibility of multiple logics but that they simultaneously struggle to combine them at the operational level. In our case we have no indication that this de-coupling (Meyer & Rowan, Reference Meyer and Rowan1977) is rooted in ill will, rather that these logics are hard or perhaps impossible to combine unless certain premises are circumvented. For example, real integration of refugees will be exceptional in football clubs that value and are keen to improve its sporting performance, simply because in practice few youth refugees enjoy the sporting capital and the life situation where they can participate and compete on equal terms with native or naturalized youth. Research on organizational hybridity focus on how organizations incorporate multiplicity of logics (Besharov & Smith, Reference Besharov and Smith2014). Besharov and Mitzinneck (Reference Besharov and Mitzinneck2020) suggest that logics at the same time may be both compatible and incompatible. In their example they explain how a business that provided valuable working experience for low-income youth ran into trouble because it also increased their training cost. In our case we would rather suggest that the logics of youth refugee integration, on the one hand, and sporting competition, on the other are compatible at the ideational level but not at a practical level. The fast-track in the ideational world is pretty much blocked in the practical world. In accord with our suggestion above, the most obvious solution to this situation is structural differentiation, which means keeping the activities separate.

Conclusion

This paper adds to a growing critical research body questioning the role of voluntary sport clubs as executors of public inclusion policies (e.g. Dowling, Reference Dowling2020; Nesse & Hovden, Reference Nesse and Hovden2023; Spaaij et al., Reference Spaaij, Magee, Farquharson, Gorman, Jeanes, Lusher and Storr2018). It expands previous research by drawing from a unique stakeholder data set, comprising not only the voluntary football clubs but also public stakeholders. Despite this rich supply of data, the study lends support to other critical studies from as diverse countries as Norway and Australia (e.g. Nesse & Hovden, Reference Nesse and Hovden2023; Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Eime and Westerbeek2019) which conclude that organizations set up for a particular aim, and being embedded in institutions with long traditions, are not easily malleable for implementation of political policies that require mobilization of additional resources and competencies. In more conceptual terms, the paper contributes to understanding how logics that appear compatible at the ideational level may turn out to be ill-sorted at the practical level. When this happens, structural differentiation may be a better solution than structural integration, notwithstanding the fast-track appeal of the latter.

It must be noted that this conclusion does not rule out that sport and football can be used both to activate refugees, thereby providing them with a more meaningful life, and provided different conditions, more substantial integration (e.g. Burrmann et al., Reference Burrmann, Brandmann, Mutz and Zender2017; Mohammadi, Reference Mohammadi2019). Add-on activities directed particularly towards refugees, provided the clubs are equipped with financing and competence, do not necessarily run counter to the logics entrenched in voluntary sport clubs. But such efforts do not by itself promote speedy integration, unless they also activate native youth. Similarly, sport clubs with the aim of sport participation rather than sport competition and selection criteria based on merit and persistence, may render refugees’ better conditions for integration.

Although we argue that ordinary voluntary sport clubs are not fast-tracks to refugee integration, the current political situation implies that this is a topic that will have to be dealt with for sport managers in many years to come. One important issue, that is largely ignored in the literature, our study included, is the relationship between the seeming hybridization of VSCs due to political pressure for refugee integration, and volunteer recruitment and retention. Consequently, we call for future research that continues to unpack how stakeholders in and outside of sport cooperate in innovative ways to address the challenges of refugee inclusion and integration.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the research group involved in carrying out this project: Kari Bachmann, Guri Kaurstad Skrove, Kristin Røvik and Sunniva Nerbøvik. They also thank all interviewees, and the anonymous reviewers for their through and constructive feedback.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Molde University College - Specialized University in Logistics. The data presented in this paper were collected through research project “Inclusion of Refugees in Norwegian Football Clubs”, funded by the Norwegian Football Association.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics Approval

The study procedures were reported and approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (SIKT).