Introduction

Risks and vulnerabilities are being shaped by events such as climate shocks, health emergencies, and prolonged conflicts, as these events are expected to increase in frequency and severity (Fejerskov, Clausen & Seddig, Reference Fejerskov, Clausen and Seddig2024; Walker & Brown, Reference Walker and Brown2019; Yan, Xu, Feng & Chen, Reference Yan, Xu, Feng and Chen2021). More than 4,000 recorded disaster events have affected hundreds of millions of people over the past decade. These events expose systemic weaknesses in humanitarian logistics (HLs) and supply chain infrastructures (Centre for Research on Epidemiology of Disasters, 2025). Consequently, HLs have become a core capability rather than a mere support function (Chin, Cheng, Wang & Huang, Reference Chin, Cheng, Wang and Huang2024). Organisations still rely on traditional logistics systems, which remain fragmented, slow to adapt, and under-resourced (Al-Natoor, Kovács, Lakner & Vizvári, Reference Al-Natoor, Kovács, Lakner and Vizvári2025; Apte, Reference Apte2009). Because humanitarian events occur in such high-stakes environments, the strategic adoption of emerging digital technologies associated with the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) has been increasingly framed to improve the agility, reach, and resilience of humanitarian supply chains (HSCs) (Chakrabarty, Das, Kushwaha & Churi, Reference Chakrabarty, Das, Kushwaha and Churi2022).

Despite the growing scholarly interest in digitalisation in HSCs, the literature neglects how this phenomenon is theorised, operationalised, and systematically mapped to humanitarian and community resilience outcomes. While increasing in scope and technical sophistication, the literature is fragmented across disaster management phases, technology types, and regional contexts. Discrete tools or isolated phases are often the primary focus rather than the disaster management lifecycle as a whole and as an integrated system (Altay, Kayadelen & Kara, Reference Altay, Kayadelen and Kara2024; De Boeck et al., Reference De Boeck, Besiou, Decouttere, Rafter, Vandaele, Van Wassenhove and Yadav2023; Prasad, Zakaria & Altay, Reference Prasad, Zakaria and Altay2018). Consequently, Givoni (Reference Givoni2016) and Tetteh, Owusu Kwateng and Tani (Reference Tetteh, Owusu Kwateng and Tani2024) have argued that a unified conceptual understanding of how digital technologies function across this full lifecycle is lacking. Current disaster response research focuses heavily on utilising and applying emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), including drones, and decision-support systems (Alam, Imran & Ofli, Reference Alam, Imran, Ofli, Franco, Gonzalez and Canos2019; Alam, Ofli & Imran, Reference Alam, Ofli and Imran2020). In contrast, the preparedness, recovery, and resilience-building phases are still comparatively underexplored in terms of the theoretical modelling and practical deployment of digitalisation (Knoble, Fabolude, Vu & Yu, Reference Knoble, Fabolude, Vu and Yu2024). This imbalance is highlighted by De Boeck et al. (Reference De Boeck, Besiou, Decouttere, Rafter, Vandaele, Van Wassenhove and Yadav2023) and Madianou (Reference Madianou2019), who assert that there is a significant emphasis on short-term operational efficiency, while system-wide learning, feedback loops, and long-term adaptability are still neglected. In addition, relatively few studies explain the adoption, adaptation, and resistance of digital tools and technologies in humanitarian settings through humanitarian theoretical lenses such as social capital, community resilience, and the behavioural aspects of technology usage (Aldrich, Kolade, McMahon & Smith, Reference Aldrich, Kolade, McMahon and Smith2021; Tacheva & Simpson, Reference Tacheva and Simpson2019; Travers, Reference Travers2024). Although widely applied in organisational technology adoption research (Kruger & Steyn, Reference Kruger and Steyn2023; Tornatzky & Fleischer, Reference Tornatzky and Fleischer1990), frameworks such as the Technology–Organisation–Environment (TOE) model have seldom been used to examine associated conditions and how they jointly shape digital humanitarian innovation, especially in low-resource and Global South settings and environments. The lack of theory-driven analysis limits the comparison of findings across studies and the understanding of organisational and contextual dynamics through which digital technologies enable, or constrain, HSCs and community resilience outcomes (Prasad et al., Reference Prasad, Zakaria and Altay2018).

This study examines global patterns of digital innovation in HSCs. The aim was to derive transferable insights for a contextualised digitalisation framework oriented towards humanitarian and community resilience in developing and emerging economy settings. We conducted a systematic quantitative literature review and bibliometric analysis to identify thematic clusters, technological concentrations, and chronological patterns across the various phases of disaster management. Building on this mapping, we undertook a targeted qualitative synthesis of key publications within major clusters and developed a conceptual framework grounded in the TOE model to explain how 4IR-related digital technologies are positioned within HSCs. Furthermore, we identified the conditions under which humanitarian resilience is supported. In contrast to previous studies that examine discrete tools or contexts, this study provides a field-level evidence base to inform scalable and context-sensitive digital adoption strategies in HSCs, which can inform digitalisation strategies in developing economy contexts.

To do so, the analysis was guided by three research questions:

RQ1. How has the global scholarly landscapexs evolved in examining digitalisation within HSCs over the past decade?

RQ2. Which digital technologies, disaster phases, and implementation contexts are most frequently associated with effective HSC practices?

RQ3. What global patterns of digital innovation in HSCs offer transferable insights for developing a contextualised digitalisation framework for developing economies?

This article contributes in several ways. Theoretically, it extends the TOE-based technology adoption research into the humanitarian domain by integrating insights from community resilience perspectives. Micro-level mechanisms from social capital and behavioural views of technology adoption are used to conceptualise a digital humanitarian supply chain resilience framework (DHSCRF) focused on dynamic resilience capabilities in low-resource environments. Methodologically, it advances HLs’ scholarship by combining large-scale bibliometric analysis with a targeted qualitative synthesis of cluster-defining publications. This moves beyond descriptive mapping towards theory-oriented field structuring. Practically, it offers guidance for humanitarian organisations and their partners on where and how to prioritise digital investments across disaster phases.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Literature review examines the literature on HSCs, digital humanitarianism, humanitarian theory, and TOE-based technology adoption. Methodology outlines the methodological approach, detailing the systematic quantitative literature review, bibliometric procedures, and qualitative synthesis. Findings provide an overview of the key findings from the bibliometric analysis and qualitative synthesis, while also presenting the proposed DHSCRF and interpreting it through the lens of the TOE. Discussion examines the theoretical, methodological, practical, and ethical implications of this study. Conclusion concludes with a discussion on the study’s limitations and future research directions.

Literature review

Studies show that HSCs and HLs differ from traditional commercial supply chains because HLs operate under significant time pressures, high demand uncertainty, unpredictability, and varying financial resource availability (Van Wassenhove, Reference Van Wassenhove2006). Consequently, the performance of HSCs is assessed based on speed, fairness, and accountability, whereas the performance of commercial supply chains is measured through a cost reduction lens. Al-Natoor et al. (Reference Al-Natoor, Kovács, Lakner and Vizvári2025) and Kovács and Spens (Reference Kovács and Spens2007) highlight that HSCs span various disaster phases, involving different HSC actors, such as international agencies, local non-governmental and non-profit organisations, governments, and private organisations. Ajith, Lux, Bentley and Striepe (Reference Ajith, Lux, Bentley and Striepe2024) and Apte (Reference Apte2009) further argue that HLs form a separate domain that requires specialised theories and instruments that address the chaotic and disorganised characteristics of disaster contexts. Building on this foundation, a growing body of work examines how digital and 4IR technologies can address information and coordination challenges across the disaster management lifecycle (Chakrabarty et al., Reference Chakrabarty, Das, Kushwaha and Churi2022; Chin et al., Reference Chin, Cheng, Wang and Huang2024). Simultaneously, to understand how organisations and communities respond to humanitarian crises, humanitarian and resilience research has developed key theoretical perspectives, such as social capital, community resilience, and behavioural technology adoption (Aldrich et al., Reference Aldrich, Kolade, McMahon and Smith2021). The next sections review digitalisation work before integrating these with humanitarian perspectives and contextual adoption theories.

Digital humanitarianism

Machine learning, the Internet of Things (IoT), remote sensing, and blockchain are increasingly used to address critical HSC challenges. These technological advancement applications include flood forecasting, response coordination, monitoring and tracking of relief aid, and managing HSC risks and uncertainties (Dubey, Gunasekaran, Bryde, Dwivedi & Papadopoulos, Reference Dubey, Gunasekaran, Bryde, Dwivedi and Papadopoulos2020; Islam et al., Reference Islam, Akter, Hossain, Faruk Hossain, Mahedy Hasan and Yakin Srizon2024). However, the adoption and integration of these technologies are not uniform. Most applications focus primarily on the response and relief phases, whereas preparedness, prevention, recovery, and resilience-building phases receive significantly less attention (Al-Natoor et al., Reference Al-Natoor, Kovács, Lakner and Vizvári2025; He, Shirowzhan & Pettit, Reference He, Shirowzhan and Pettit2022; Knoble et al., Reference Knoble, Fabolude, Vu and Yu2024; Muniandy, Maidin, Batumalay, Dhandapani & Prakash, Reference Muniandy, Maidin, Batumalay, Dhandapani and Prakash2025).

Furthermore, the potential of digitalisation in HSCs remains largely untapped in low-resource settings, particularly in parts of the Global South. The adoption and expansion of technology are limited by institutional weaknesses, infrastructural gaps and shortcomings, resource limitations, and scarce data availability (De Boeck et al., Reference De Boeck, Besiou, Decouttere, Rafter, Vandaele, Van Wassenhove and Yadav2023; Prasad et al., Reference Prasad, Zakaria and Altay2018). Concerns have been raised about the potential of digital innovation and data practices that reinforce and exacerbate power imbalances and inequality, rather than enhancing efficiency or accountability (Madianou, Reference Madianou2019). These trends underscore the need for a comprehensive global perspective on the digitalisation of HSCs, as well as the integration of humanitarian theories with relevant technological frameworks, such as the TOE. This approach can help direct context-sensitive digital transformation initiatives designed to support managers working within these critical supply chains.

Digitalisation across disaster management

The integration and adoption of digital and emerging 4IR technologies across disaster management phases and HSCs are increasingly receiving academic and scholarly attention, as these technologies not only improve visibility and responsiveness during disasters but also provide coordination in complex and multidimensional humanitarian disasters and crises (Romano & Albrecht, Reference Romano and Albrecht2023). Literature shows varying levels of technological, organisational, and environmental maturity and readiness across disaster management phases, thereby supporting the relevance and validity of applying and discussing the dimensions of the TOE framework in Humanitarian lenses for digitalising supply chains.

In the preparedness phase, key elements centred around digitalisation include inventory prepositioning, early warning systems, and risk modelling (Ghorbankhani, Mousavian, Shahriari Mohammadi & Salehi, Reference Ghorbankhani, Mousavian, Shahriari Mohammadi and Salehi2024; Gunawan, Reference Gunawan2024; Leo, Laud & Chou, Reference Leo, Laud and Chou2023). The collection and processing of environmental, social, and infrastructural data are possible through technologies such as IoT, which includes remote sensors for flood and weather monitoring, and big data analytics tools that are often used to inform HSC risk strategies (Chamola, Hassija, Gupta & Guizani, Reference Chamola, Hassija, Gupta and Guizani2020). Data-driven platforms are also used by some humanitarian organisations to optimise warehouse locations and predict demand surges. The application of AI in climate prediction and disease outbreak modelling is also emerging (Bhowmick, Barman & Kumar Roy, Reference Bhowmick, Barman and Kumar Roy2025; Congès, Fertier, Salatgé, Rebière & Benaben, Reference Congès, Fertier, Salatgé, Rebière and Benaben2024). However, many of these systems remain restricted to donor-supported organisations that possess the necessary technical expertise, highlighting the shortage of skilled personnel and underdeveloped information frameworks within humanitarian organisations. From an environmental perspective, these organisations have insufficient and inadequate data policies, limited internet access, and poor coordination with the public sector, which may hinder the wider adoption and implementation of these technologies (Lee, Lu & Jin, Reference Lee, Lu and Jin2021; Madianou, Reference Madianou2019).

The response phase is receiving significant academic attention relating to digital innovation and transformation, with many examples. For instance, tools powered by AI are used for immediate damage evaluation, text mining from social media, and assisting in prioritising logistics decisions (Alam, Imran & Ofli, Reference Alam, Imran, Ofli, Diesner, Ferrari and Xu2017; Imran, Mitra & Castillo, Reference Imran, Mitra, Castillo, Calzolari, Choukri, Mazo, Moreno, Declerck, Goggi and Mariani2016; Zahra, Imran & Ostermann, Reference Zahra, Imran and Ostermann2020). The use of UAVs, such as drones, facilitates the delivery of medical supplies, maps previously inaccessible areas, and enhances situational awareness. Larger humanitarian organisations tend to be better equipped and prepared due to their operational mandates, which originate from well-documented managerial insights. These organisations frequently establish emergency coordination platforms and dedicated response teams. Nonetheless, smaller local organisations often face exclusion due to regulatory limitations and financial challenges (Gabay, Reychav & Jonathan, Reference Gabay, Reychav and Jonathan2025). The environmental circumstances, however, present a mixed picture. Although donors support technology pilot projects, the regulation of UAVs varies greatly from one country to another, and AI models frequently rely on data that is not relevant to local conditions (Steenbergen & Mes, Reference Steenbergen, Mes, K.-H, Feng, Kim, Lazarova-Molnar, Zheng, Roeder and Thiesing2020; Xia, Fattah & Babar, Reference Xia, Fattah and Babar2024). Despite this, the integration of decision-support systems, cloud-based logistics software, and automated delivery continues to grow (Jiang & Wang, Reference Jiang, Wang, Ye and Zhang2024).

In the recovery phase, digitalisation provides support in the pre-recovery process after disasters and crises occur by facilitating and monitoring the tracking of beneficiaries and ensuring transparency for donors. Various blockchain applications have been pilot-tested for various uses, including cash transfers, supply chain traceability, and fraud prevention. Building Blocks initiatives also demonstrate the effectiveness of distributed ledgers in camp-based environments, reducing administrative expenses and improving accountability (Ahmed, Fumimoto, Nakano & Tran, Reference Ahmed, Fumimoto, Nakano and Tran2024; Bhat, Pranaav, Mini & Tosh, Reference Bhat, Pranaav, Mini and Tosh2021). The current state of blockchain technology is advanced enough to support controlled pilot projects; however, its adoption and integration into existing humanitarian information systems (IS) remain quite limited. From an organisational perspective, implementation has largely been confined to well-funded and well-resourced international organisations with internal digital governance capabilities. However, various challenges exist, including technical entry barriers, insufficient knowledge of blockchain, and a fragmented donor and regulatory landscape (Bhat et al., Reference Bhat, Pranaav, Mini and Tosh2021; Bhattacharjee, Chattopadhyay, Paul & Bhattacharya, Reference Bhattacharjee, Chattopadhyay, Paul, Bhattacharya, Chaki, Cortesi, DasGupta and Saha2025). On the environmental side, blockchain-based recovery tools face limitations due to poor and inadequate digital infrastructure, uncertainty regarding data ownership laws, and a lack of trust in technology among partner organisations (Hanna, Xu, Wang & Hossain, Reference Hanna, Xu, Wang and Hossain2022).

The resilience-building phase involves developing systems and communities that can adapt to emerging threats, risks, and uncertainties while integrating learning processes to enhance their effectiveness and return to a state of normalcy following the occurrence of risks, threats, and vulnerabilities. Digital tools in resilience building include simulation environments, e-learning platforms, digital twins, and mobile training apps. Simulation platforms enable organisations to simulate cascading risks, while field personnel receive just-in-time logistics training through mobile-based systems (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lu and Jin2021). Technologically, many resilience tools are accessible and scalable. However, organisational capacity to deploy these tools varies significantly (Dinh & O’Leary, Reference Dinh and O’Leary2025; Kruger & Steyn, Reference Kruger and Steyn2023). Larger agencies may have embedded feedback systems, while smaller actors may rely on manual or paper-based tracking (De Boeck et al., Reference De Boeck, Besiou, Decouttere, Rafter, Vandaele, Van Wassenhove and Yadav2023). Environmental conditions are critical to success, and yet in many low- to middle-income contexts, there is a lack of regulatory frameworks for resilience-focused technologies. Short funding cycles and inadequate national-level planning further limit adoption (Madianou, Reference Madianou2019). Across phases, the literature is dominated by technical descriptions of tools and pilots, with comparatively less attention to how digitalisation interacts with organisational capabilities and communities in wider, environmentally constrained settings. This gap calls for in-depth qualitative and action research approaches.

Humanitarian lenses for digitalising supply chains

Current literature features HSCs that are predominantly led by technology and operations. Studies on crisis mapping, social media analytics, UAVs, blockchain and optimisation models emphasise technical performance, information flows and logistics efficiency (Ali & Abraham, Reference Ali and Abraham2022; Biswas & Gupta, Reference Biswas and Gupta2020; Feng & Cui, Reference Feng and Cui2021; Golan, Jernegan & Linkov, Reference Golan, Jernegan and Linkov2020; Imran et al., Reference Imran, Mitra, Castillo, Calzolari, Choukri, Mazo, Moreno, Declerck, Goggi and Mariani2016; Le Roux, Reference Le Roux2021; Zhang, Kumar & Yao, Reference Zhang, Kumar and Yao2020). This literature confirms that digital tools can extend reach and agility, particularly in climate-affected and fragile settings. However, it is comparatively thin on how digitalisation interacts with humanitarian principles, power relations, and community-level capacities, especially in the Global South. To address this gap, the present study employs a humanitarian lens in conjunction with the TOE framework to analyse digitalisation patterns in HSCs.

Social capital theory emphasises that HSCs are embedded in networks of relationships, norms, and trust, rather than being neutral technical systems. This theory argues that sharing information among stakeholders enhances coordination and collaboration, enabling them to achieve collective goals (Amelia, Wirjodirdjo & Dewi, Reference Amelia, Wirjodirdjo and Dewi2024; Bourdieu & Richardson, Reference Bourdieu and Richardson1986). Likewise, Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998) distinguish between structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions of social capital, showing how these underpin information sharing and joint problem-solving between organisations. Krishnappa, Saraswathi and Chelliah (Reference Krishnappa, Saraswathi and Chelliah2024) demonstrate that in disaster contexts, communities with dense and diverse social ties recover more quickly than those with fragmented networks, indicating that social capital can be as decisive as physical resources in recovery trajectories. For digital HSCs, these insights imply that platforms, data standards, and decision-support tools actively reshape who is connected, who is visible in data, and whose knowledge counts in coordination processes. Social capital, therefore, primarily maps onto the organisational and environmental dimensions of TOE, where inter-organisational networks, trust in digital systems, and the presence of local intermediaries condition whether new tools are adopted in ways that strengthen or weaken collaboration (Marutschke, Nurdin & Hirono, Reference Marutschke, Nurdin and Hirono2024).

Scholarship on community resilience shifts the focus from individual organisations to the adaptive capacities of communities as complex systems. Norris, Stevens, Pfefferbaum, Wyche and Pfefferbaum (Reference Norris, Stevens, Pfefferbaum, Wyche and Pfefferbaum2008) conceptualise community resilience as interdependent economic, social, information/communication, and competence capacities that enable adaptation after disturbance. Their study adopts community resilience as its primary humanitarian lens because the core question in digitalising HSCs is whether investments in data and technology enhance or erode these capacities, particularly in low-resource, politically constrained settings where institutional fragility and inequality are pronounced (Abdel-Mooty, Yosri, El-Dakhakhni & Coulibaly, Reference Abdel-Mooty, Yosri, El-Dakhakhni and Coulibaly2021). Furthermore, combining community resilience with TOE allows analysis to move beyond tool-level performance towards system-level adaptive capacity.

Behavioural perspectives on technology adoption add a micro-level lens to these system-oriented views. Diffusion of innovation (DOI) theory (Rogers, Reference Rogers2003), widely applied in IS and increasingly in humanitarian technologies (Stratu-Strelet, Gil-Gómez, Oltra-Badenes & Guerola-Navarro, Reference Stratu-Strelet, Gil-Gómez, Oltra-Badenes and Guerola-Navarro2023), identifies perceived relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability as central determinants of adoption. These perceptions are mediated by social networks and communication channels rather than technical features alone. In HSCs, staff and volunteers operate under pressure, uncertainty, and moral stress, which can dampen their willingness to experiment with unfamiliar systems, even when these promise efficiency gains. Meanwhile, communications impacted by disasters might not always trust digital systems that collect sensitive data or help provide access to relief aid. The principles of DOI primarily correspond to the technological and organisational aspects of the TOE framework, where factors such as design, usability, training, and leadership support influence how digital tools and technologies are adopted to enhance community resilience.

The TOE framework, as proposed by Tornatzky and Fleischer (Reference Tornatzky and Fleischer1990), consists of three dimensions. In the HSC, the technological context refers to the maturity, interoperability, and appropriateness of digital tools deployed in HSCs. Meanwhile, the organisational context encompasses resources, structures, culture, prior IS sophistication, and top management support among humanitarian actors. Environmental contexts include regulatory regimes, donor and partner pressures, infrastructure, and the political economy of crisis-affected regions (Karinshak, Reference Karinshak2024). Despite this relevance, existing humanitarian applications of TOE remain rare and often focus on national disaster management systems rather than supply chains. Even where TOE is used, it is typically operationalised as a checklist of determinants rather than integrated with humanitarian theory (AlHinai, Reference AlHinai2020). This study departs from this use of the framework by explicitly integrating TOE with community resilience, social capital, and behavioural adoption perspectives. Community resilience is used as the primary outcome lens, while social capital and behavioural adoption specify the social and behavioural mechanisms through which TOE contexts shape digitalisation.

Methodology

This study follows a systematic quantitative literature review design, guided by bibliometric methods, to examine how digital technologies have been conceptualised, adopted, and applied across HSCs between 2015 and 2025. Systematic quantitative literature reviews are used to ensure the transparent and reproducible screening and coding of the large body of peer-reviewed publications. Bibliometric techniques facilitate the analysis of performance and science mapping of the field’s intellectual structure (Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey & Lim, Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021; Lim, Kumar & Donthu, Reference Lim, Kumar and Donthu2024). The review is theoretically grounded in the TOE, which informed the subsequent interpretation of digitalisation patterns in terms of technological maturity, organisational capacity, and environmental conditions. The methodological process follows the SPAR-4-SLR protocol by Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani (Reference Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani2021) to enhance replicability and rigour. This was considered as HSCs integrate interdisciplinary fields such as supply chain management, disaster studies, and IS (Mukherjee, Lim, Kumar & Donthu, Reference Mukherjee, Lim, Kumar and Donthu2022). Figure 1 shows the SPAR-4-SLR protocol overview for this study.

Figure 1. SPAR-4-SLR applied to this study.

Data source, search strategy, and screening

Scopus was chosen due to its extensive academic coverage and in-depth bibliometric information. Web of Science was evaluated using the same keywords, revealing significant overlap, which suggests that very few papers would be missed within the parameters of this study. The search string incorporated Boolean operators to merge key terms related to HSCs and digital technologies associated with the 4IR. The final search string can be found in Appendix A.

The assembling stage limited the results to include peer-reviewed articles and conference papers published between 2015 and 2025, written in English, and indexed in relevant subject areas, including business, social sciences, decision sciences, environmental sciences, computer science, engineering, and multidisciplinary studies. The initial query returned 7,948 documents. Applying the publication year filter reduced the count to 6,963 records, and subject area filters further reduced it to 6,105. Document type limitations were applied, resulting in 4,909 eligible records. The decision to include conference papers was deliberate, as this often shows emerging digital applications and prototypes in humanitarian contexts.

During the arranging stage, data was exported to BibTex and CSV formats and cleaned using OpenRefine 3.8.2. Duplicate records were identified and removed, and key metadata (author names, affiliations, and keywords) were standardised through fuzzy matching. This yielded a final clean corpus of 4,780 documents for analysis. This cleaning process was necessary to avoid inflation of authors and to obtain a coherent network for cluster identification and science mapping (Aria & Cuccurullo, Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017). As with bibliometric studies, the corpus excludes non-indexed and non-English outputs and does not capture grey literature or internal agency reports. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as mapping the formal academic knowledge base rather than the full practice landscape.

Bibliometric analysis

Bibliometric analysis was conducted using Bibliometrix (via the RStudio IDE version 2025.05.0+496) and VOSviewer. These tools were selected for their complementary strengths, where Bibliometrix was used for detailed performance metrics and thematic evolution mapping, and VOSviewer for advanced visualisation of bibliographic networks. Performance analysis described the evolution of digital HSC research in terms of annual publication and citation trends, as well as the leading journals, prolific authors, and contributing institutions. This step provided an overview of the field’s growth trajectory.

Science mapping techniques were employed to uncover the conceptual and intellectual structures of the field across three key areas:

i. Keyword co-occurrence analysis was used to identify recurring thematic clusters, such as the use of AI for disaster response or blockchain for aid transparency. Co-word networks were developed based on the author keywords, employing full counting and setting a minimum co-occurrence threshold of five occurrences per keyword. This approach helps to include emerging topics while minimising the influence of unique terms, aligning with principles of science mapping (Aria & Cuccurullo, Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017). Sensitivity analyses with thresholds ranging from 3 to 10 revealed similar overarching cluster structures, indicating the robustness of the identified themes.

ii. Bibliographic coupling was applied to identify common citation patterns and behaviours among articles, assisting the organisation of related documents and identifying contemporary research communities within the discipline. The strength of coupling was calculated at the document level using full counting, including only document pairs that had at least 12 shared references. To prevent unstable similarity assessments and informative link structures, documents with fewer than 10 references were excluded.

iii. Co-citation analysis was conducted to outline the intellectual underpinnings of digital HSC research. Co-citation networks were created at the source level for the most frequently cited references, with a minimum of 50 citations to ensure significant groupings. Standard clustering algorithms and minimum frequency restrictions were employed to form interpretable clusters, thereby preventing network fragmentation.

These techniques enabled triangulation of thematic patterns, contemporary research communities, and intellectual foundations, reducing the risk that the subsequent framework is driven by artefacts from a single mapping technique.

Targeted qualitative synthesis and framework development

A targeted qualitative synthesis was conducted on key cluster publications to move beyond generic descriptive mapping. For each bibliographic coupling cluster, the most representative articles were selected. Their texts were examined to identify (i) types of digital technologies considered, (ii) disaster management phase or phases addressed, (iii) the HSC functions involved, and (iv) theoretical lenses employed. Qualitative insights were then interpreted through the lens of the TOE. For each cluster, digital applications were coded based on technological facets, including data intensity, interoperability, and maturity. For the organisational context, governance structures, capabilities, leadership, and inter-organisational coordination were considered. For environmental contexts, regulatory regimes, infrastructure, donor and policy pressures, conditions were considered. On this basis, we developed the DHSCRF, which links digital technology families and disaster phases to TOE conditions and to resilience-related capabilities in HSCs. The assessing stage of SPAR-4-SLR combined (i) quantitative indicators of domain structure and evolution with (ii) theory-oriented synthesis of cluster content to derive propositions and gaps for future research, specifying contingencies and mechanisms that can be empirically validated and refined through subsequent case-based and action research studies in humanitarian settings.

Findings

The final dataset comprised 2,107 unique sources, encompassing 2,493 journal articles and 2,287 conference proceedings, offering a well-rounded combination of peer-reviewed studies and emerging practice-focused insights. The average age of the documents was 3.17 years, reflecting the recent nature of the field and its responsiveness to evolving and ongoing crises, such as COVID-19 and climate-related disasters. The collection shows a compound annual growth rate of 25.85% in publication, indicating a significant academic growth rate in response to the increasing importance of digitalisation in disaster contexts. A total of 14,231 authors contributed to this body of literature, with an average of 4.12 co-authors per document, highlighting a highly collaborative research environment. There were 274 single-authored documents. The average citation count was 12.23 per article, reflecting a growing interest among scholars, especially given the field’s relative novelty. The 176,512 cited references demonstrate considerable engagement with foundational and adjacent literatures. The presence of 11,684 author-assigned keywords and 19,417 Keywords Plus points signifies a thematically and semantically rich knowledge base, with technology-related terms such as ‘blockchain’, ‘IoT’, ‘real-time analytics’, and ‘last-mile delivery’ commonly found across document clusters.

Performance analysis: evolution of the field (RQ1)

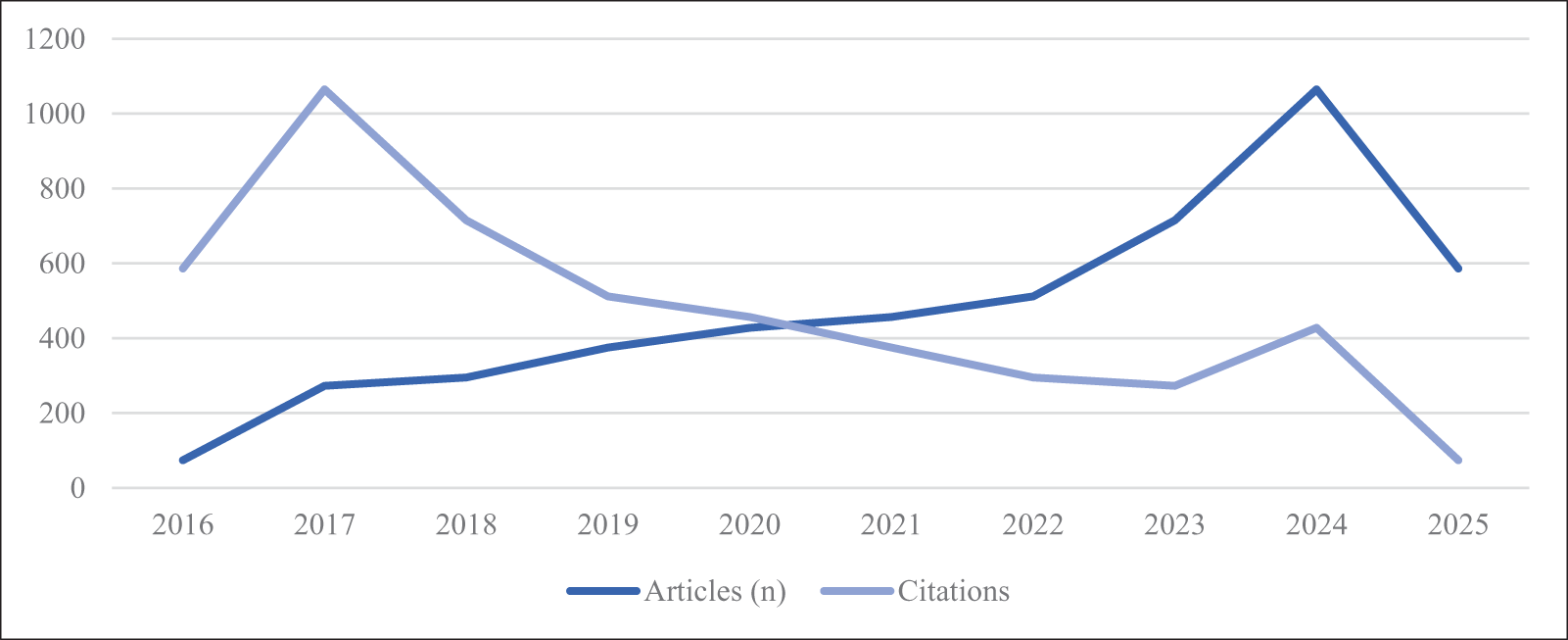

Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of the scholarly output within the field, directly corresponding to RQ1. From 2015 to 2025, the yearly number of publications (n) grew from 17 documents in 2015 to a high of 349 in 2024, demonstrating a continued growth pattern in digital HSC research. This trend aligns with other emerging areas, where digital technologies are gaining attention in operation and supply chain management. Conversely, the average total citation per article metric, which indicates the typical number of citations each article received, follows a reverse trajectory. Early publications (2016–2019) maintained relatively high citation averages, reaching a peak of 36.47 citations per article in 2019. In contrast, more recent publications, particularly from 2022 onwards, exhibit declining citation averages, dropping to 0.62 in 2025. This is expected, given the shorter citation window for recent publications. These trends suggest a field that is expanding in volume and beginning to consolidate its intellectual core, with early foundational contributions attaining disproportionate attention in the increasing volume of new work, much of which has not yet fully diffused through citation networks.

Figure 2. Citations and number of articles per year.

Science mapping (RQ2 and RQ3)

In relation to RQ2 and RQ3, this section presents the keyword co-occurrence and thematic mapping results from the corpus. In addition to network metrics, we conducted a targeted qualitative reading of key articles in each cluster to interpret the dominant technologies, disaster phases, and their alignment with TOE conditions and resilience-related capacities.

Keyword co-occurrence clusters: technologies, disaster phases, and TOE

The co-word network analysis was conducted on author keywords using full counting and a minimum co-occurrence threshold of five, with clusters identified through VOSviewer’s clustering algorithm. The resulting network in Figure 3 presents a structured, multidimensional landscape of digital HSC research. Six thematic clusters were identified, with this study focusing on four central clusters, which together contain the most high-frequency, digitalisation-related terms. They represent distinct but partially overlapping bodies of literature, providing insight into leading technological paradigms, disaster phases, and TOE-related conditions addressed in the field.

Figure 3. Keyword co-occurrence.

The first cluster (i), involving machine learning and disaster forecasting (red), is characterised by terms such as ‘disaster management’, ‘machine learning’, and ‘remote sensing’. This indicates a significant concentration of research that applies AI and statistical learning to model and predict environmental hazards and disasters, including floods, cyclones, and landslides. The presence of ‘learning systems’, ‘climate change’, and ‘floods’ further emphasises the community’s focus on processing environmental data and algorithmic forecasting in light of increased climate-related risks (Akinboyewa, Ning, Lessani & Li, Reference Akinboyewa, Ning, Lessani and Li2024). Abdelaziz, Mesbah and Kholief (Reference Abdelaziz, Mesbah and Kholief2025) represent this domain through their introduction of an artificial neural network model that leverages historical disaster data to enhance cloud infrastructure resilience, thereby merging predictive analytics with geospatial optimisation for improved forecast accuracy and shorter lead times in warnings. Comparative work by Bhowmick et al. (Reference Bhowmick, Barman and Kumar Roy2025), Congès et al. (Reference Congès, Fertier, Salatgé, Rebière and Benaben2024), Ghorbankhani et al. (Reference Ghorbankhani, Mousavian, Shahriari Mohammadi and Salehi2024), Gunawan (Reference Gunawan2024), Leo et al. (Reference Leo, Laud and Chou2023) illustrates the use of machine learning, IoT, and big data for flood, landslide, and disease outbreak prediction, consolidating this cluster as the core of data-intensive environmental forecasting in humanitarian contexts. Similarly, the cluster focuses on preparedness and early response, primarily linking digitalisation to TOE conditions (data availability, model performance, and sensor coverage). This was demonstrated in the work by Rahman, Fahim Faisal, Mondal and Mahfuzur Rahman (Reference Rahman, Fahim Faisal, Mondal and Mahfuzur Rahman2025), who show the superior performance of long short-term memory networks in cyclone track prediction. In TOE terms, the technological context is specified in detail, while organisational capacity and environmental constraints, such as local data governance, public-sector capacity, and connectivity, are rarely theorised. The integration of HSC decision-making is often assumed rather than examined. This limits explicit analysis on how improved information and communication capacities translate into community resilience in low-resource settings.

The second cluster (ii) emergency services and disaster logistics (purple) is defined by keywords such as ‘disaster relief’, ‘emergency services’, ‘resource allocation’, and ‘natural disasters’. It is strongly response-phase orientated and combines operations research, simulation, and optimisation models to design and evaluate relief distribution strategies, often with limited emphasis on specific digital technologies beyond IS or decision-support systems (Chang, Wu & Ke, Reference Chang, Wu and Ke2022; Karinshak, Reference Karinshak2024; Sermet & Demir, Reference Sermet and Demir2022). Recent work on green and robust HLs (Abbasi, Damavandi, RadmanKian, Zeinolabedinzadeh & Kazancoglu, Reference Abbasi, Damavandi, RadmanKian, Zeinolabedinzadeh and Kazancoglu2025; Jiang & Wang, Reference Jiang, Wang, Ye and Zhang2024) and multi-phase disaster logistics planning (Ghorbankhani et al., Reference Ghorbankhani, Mousavian, Shahriari Mohammadi and Salehi2024) aligns with this cluster, reinforcing its focus on routing, facility location, and fleet management under disruption. This cluster largely foregrounds technological and operational performance (delivery times, fill rates) and, to a lesser extent, organisational constraints (fleet size, depot capacity). Environmental TOE factors (regulation, infrastructure, donor policies) and humanitarian theory are usually implicit rather than explicit constructs (Madianou, Reference Madianou2019), which restricts the transferability of these models to low-resource and highly politicised contexts.

The third cluster (iii) robotics UAVs and remote operations (blue) is distinguished by terms such as ‘drones’, ‘UAVs’, ‘robotics’, and ‘aerial vehicles’, which reflect a technology-led approach to overcoming last-mile and terrain-based constraints in HLs. Studies in this area often highlight the experimental deployment of UAVs for medical deliveries, terrain mapping, and earthquake assessment (Abbas, Abu Talib, Ahmed & Belal, Reference Abbas, Abu Talib, Ahmed and Belal2024; Afridi et al., Reference Afridi, Minallah, Sami, Allah, Ali and Ullah2019; Javaid, Fahim, He & Saeed, Reference Javaid, Fahim, He and Saeed2024; Krupakar, Sankeerth, Akash, Velamala & Valiveti, Reference Krupakar, Sankeerth, Akash, Velamala and Valiveti2024; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Xu, Feng and Chen2021). However, their regulatory feasibility and long-term adoption remain fragmented, raising broader concerns about techno-solutions in development and humanitarian contexts, as well as the risk of creating parallel systems that bypass local health and logistics infrastructures (Madianou, Reference Madianou2019). In TOE terms, the technological context (platform capabilities, range, payload, navigation systems) is detailed, whereas organisational factors (integration with existing logistics processes, workforce skills, safety protocols) and environmental conditions (airspace regulation, community acceptance, liability regimes, insurance) are noted but under-theorised. As a result, the conditions under which UAV-based solutions contribute to or undermine local adaptive capacity and community trust are rarely specified, despite their potential to alter information, communication, and mobility capacities in crisis-affected areas.

The fourth cluster (iv) data analytics, IS, and crisis decision-making (green) was found to centre around ‘big data’, ‘information management’, ‘data mining’, ‘decision support systems’, and ‘crisis management’. This cluster reflects the convergence of data science and humanitarian coordination. Studies by Ahmed et al. (Reference Ahmed, Fumimoto, Nakano and Tran2024), Bhat et al. (Reference Bhat, Pranaav, Mini and Tosh2021), and Papadopoulos et al. (Reference Papadopoulos, Gunasekaran, Dubey, Altay, Childe and Fosso-Wamba2017) show applications ranging from logistics dashboarding and demand forecasting to blockchain-based traceability and accountability mechanisms. Empirical work on digital platforms, social media analytics, and supply chain visibility in humanitarian and development settings (Dubey et al., Reference Dubey, Gunasekaran, Bryde, Dwivedi and Papadopoulos2020; Islam et al., Reference Islam, Akter, Hossain, Faruk Hossain, Mahedy Hasan and Yakin Srizon2024; Jiang & Wang, Reference Jiang, Wang, Ye and Zhang2024) also falls within this cluster, highlighting efforts to build integrated information architectures across procurement, warehousing, and last-mile distribution. Unlike the first cluster, which is dominated by environmental forecasting, this cluster emphasises organisational-level information flows and coordination across procurement, warehousing, and distribution. However, the contributions treat digital architectures as technical enablers. There is limited engagement with culture, inter-organisational power relations, or community participation, which are central to organisational and environmental TOE dimensions. There is also limited engagement with perspectives on social capital and community resilience. Consequently, while IS capacities are strengthened, the distribution of control, trust, and inclusion in these systems remains weakly theorised, and concerns about adverse digital incorporation and data justice are only intermittently acknowledged (Madianou, Reference Madianou2019).

The co-word network confirms that digital HSC research is interdisciplinary, combining environmental science, computer science, and IS. From an RQ2 perspective, the quantitative mapping and qualitative cluster readings show that AI, machine learning, UAVs and robotics, and data analytics platforms direct the current digitalisation agenda and are most frequently associated with preparedness and response activities, whereas recovery and long-term resilience remain weakly represented (Al-Natoor et al., Reference Al-Natoor, Kovács, Lakner and Vizvári2025; He et al., Reference He, Shirowzhan and Pettit2022; Knoble et al., Reference Knoble, Fabolude, Vu and Yu2024; Muniandy et al., Reference Muniandy, Maidin, Batumalay, Dhandapani and Prakash2025). Across clusters, technological TOE conditions and operational performance are key, while organisational and environmental contexts, as well as humanitarian theory lenses, are rarely explicitly considered (Altay & Green, Reference Altay and Green2006; Kovács & Spens, Reference Kovács and Spens2007; Van Wassenhove, Reference Van Wassenhove2006). In resilience terms, current research focuses on developing information and sensing capacities, with far less attention paid to institutional, competence, and economic capacities that underpin community resilience in low-resource settings (De Boeck et al., Reference De Boeck, Besiou, Decouttere, Rafter, Vandaele, Van Wassenhove and Yadav2023; Norris et al., Reference Norris, Stevens, Pfefferbaum, Wyche and Pfefferbaum2008). These combined patterns motivate the DHSCRF developed later in the paper, which links digital technology families and disaster phases to TOE configurations and resilience-related capabilities in developing and resource-constrained contexts.

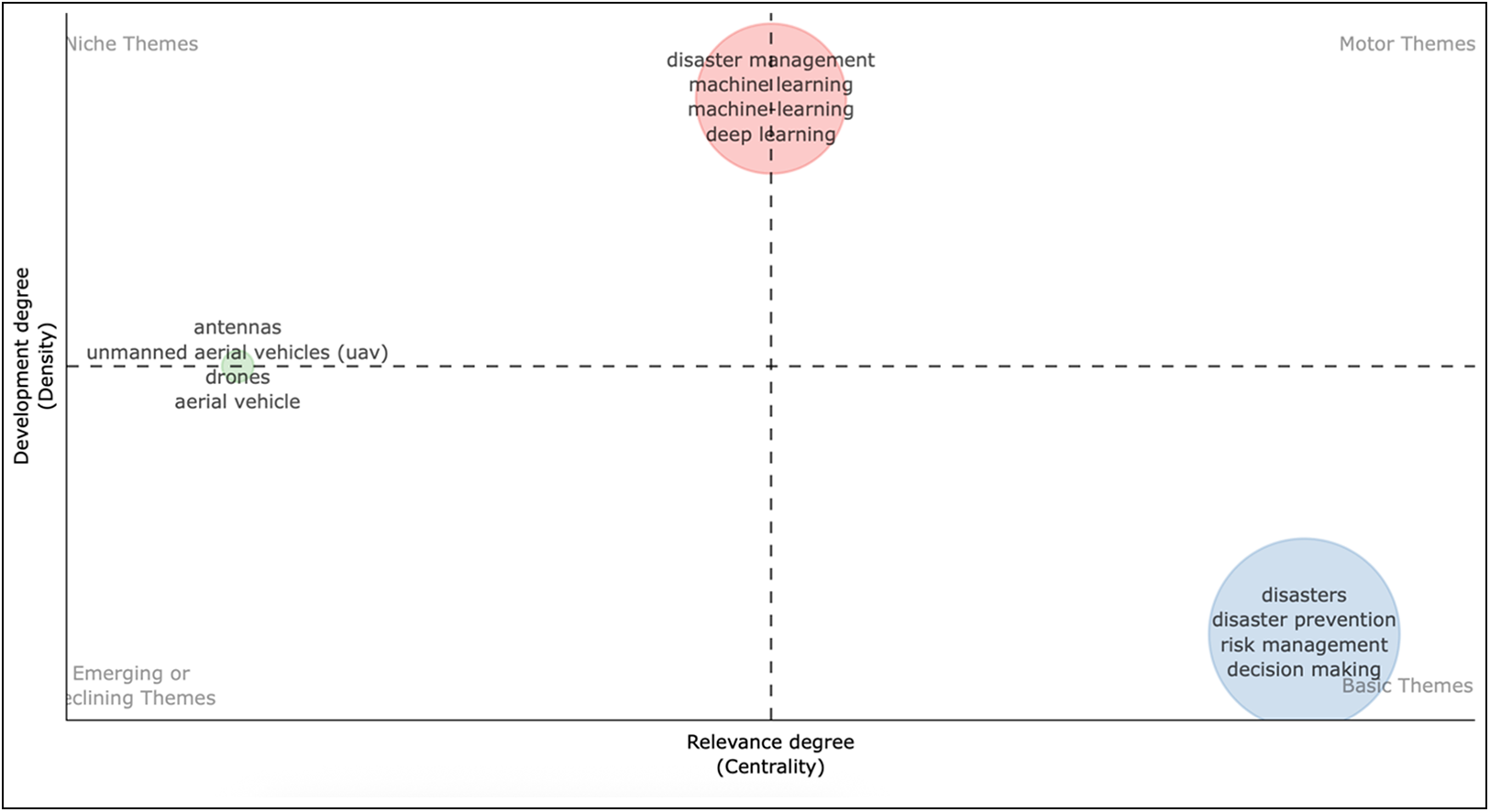

Thematic map: maturity gaps

Thematic mapping evaluates the intellectual architecture of a field by positioning themes on a two-dimensional plane defined by centrality (relevance to the field) and density (internal development). Motor themes combine high centrality and density; niche themes are internally developed but peripheral; basic themes are central but underdeveloped; and emerging themes have been neglected in past research (Chebo & Dhliwayo, Reference Chebo and Dhliwayo2024). This approach enables the specification of domain structures and trajectories. The thematic structure observed in the digitalisation of HSCs reveals a dynamic yet stratified field, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Thematic map of digital humanitarian supply chain (HSC) research (2015–2025).

The ‘disaster management’ cluster, located in the motor themes quadrant, constitutes the core domain. It incorporates concepts like ‘machine learning’, ‘deep learning’, and ‘risk assessment’, highlighting a developed area where predictive analytics and AI-based operational approaches intersect. Studies such as those by Rahman et al. (Reference Rahman, Fahim Faisal, Mondal and Mahfuzur Rahman2025) demonstrate how deep learning and ensemble techniques improve cyclone tracking, flood forecasting, and multi-hazard risk assessment. Similarly, Abdelaziz et al. (Reference Abdelaziz, Mesbah and Kholief2025) have developed AI-supported decision models for cloud-centric disaster recovery, integrating resilience directly into the infrastructure design. Sreedevi (Reference Sreedevi2020) further strengthens this domain through their interpretable machine learning framework for fragility modelling, promoting the trend towards transparent and actionable AI in humanitarian engineering. The cluster demonstrates a high level of methodological complexity, marked by robust technological performance. However, the connections to HSC decisions (such as prepositioning, stock distribution, and routing) and the organisational factors of the TOE are not clearly defined.

The ‘disasters’ cluster emphasises the importance of environmental disruption as the primary issue within the field. It combines terms related to various types of hazards and real-world case scenarios. For instance, Abbasi et al. (Reference Abbasi, Damavandi, RadmanKian, Zeinolabedinzadeh and Kazancoglu2025) contribute to this area by developing green logistics systems that consider both forward and reverse flows during disasters, thereby linking environmental sustainability with disaster management. This shows that a hazard-focused perspective takes precedence over supply chain governance or community-centred viewpoints.

Conversely, the ‘antennas’ cluster is located in the niche themes quadrant, indicating it as a technically specialised field with limited integration into wider humanitarian discourses. Research conducted by authors such as Wuyun et al. (Reference Wuyun, Sun, Chen, Li, Han, Shi and Zhao2025), which explores remote sensing and high-resolution terrain mapping, highlights the complexities of geospatial analytics and signal-based monitoring. However, these technological findings are typically restricted to specific uses and seldom address factors such as institutional preparedness, localisation dynamics, or resilience outcomes, leaving their systemic relevance under-theorised.

Topics such as blockchain, IS infrastructure, or platform governance, which are occasionally mentioned within the larger dataset, may emerge as essential but underdeveloped themes in upcoming analyses. These areas, particularly when connected to donor coordination and data integrity, hold promise for future conceptual work, especially in African humanitarian contexts where policy alignment and digital infrastructure remain pressing concerns.

The emerging quadrant also lacks stable clusters; however, the distribution of low-centrality, low-density keywords suggest that neglected lines of inquiry are present. Terms related to trust in digital systems, gendered access, local innovation ecosystems, and community participation appear sporadically without forming coherent themes. From a humanitarian theory perspective, these gaps are notable. They correspond closely to the social capital, community resilience, and behavioural adoption constructs identified earlier in the review, as well as to the ethical concerns highlighted in the critical digital humanitarianism literature. Their marginal position in the thematic map reinforces the conclusion that digital HSC research remains strongly technology-led and hazard – or operations-focused, with limited explicit attention to social, behavioural, and justice dimensions.

Intellectual structure (RQ3)

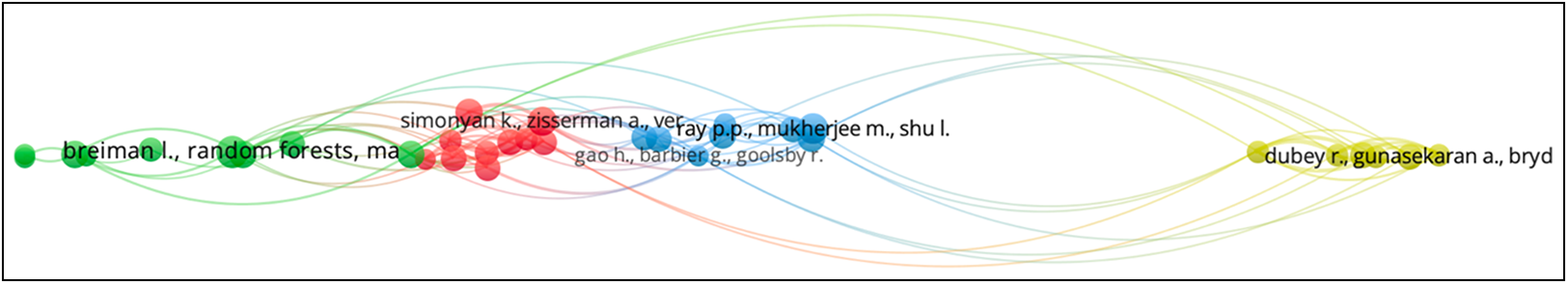

To further address RQ3, bibliographic coupling was used to identify contemporary research communities based on shared reference lists, while co-citation analysis mapped the foundational works that were most frequently cited together. For each major coupling cluster, model articles were examined qualitatively to characterise dominant digital technologies, disaster phases, HSC functions, and TOE-related conditions and resilience implications.

Bibliographic coupling: research communities

Based on the bibliographic coupling results and visualisation in Figure 5, the field of digital HSCs demonstrates a thematically convergent but methodologically diverse structure. The clusters represent distinct research communities that together structure HSC digitalisation scholarship.

Figure 5. Bibliographic coupling network of digital humanitarian supply chain research (2015–2025).

The (i) predictive modelling and applied AI in crisis contexts (red) cluster, which includes authors such as Ragini, Anand and Bhaskar (Reference Ragini, Anand and Bhaskar2018) and Fan, Zhang, Yahja and Mostafavi (Reference Fan, Zhang, Yahja and Mostafavi2021), reflects a technologically mature sub-community focused on machine learning, deep learning, and disaster risk reduction. The inclusion of Paul and Sosale (Reference Paul and Sosale2020) and Devaraj, Murthy and Dontula (Reference Devaraj, Murthy and Dontula2020) highlights a methodological shift towards explainable AI, particularly in early warning and fragility assessment systems. Representative applications, such as those by Rahman et al. (Reference Rahman, Fahim Faisal, Mondal and Mahfuzur Rahman2025) and Abdelaziz et al. (Reference Abdelaziz, Mesbah and Kholief2025), demonstrate the use of recurrent and ensemble models for cyclone tracking, flood prediction, and infrastructure recovery planning. Theoretical contributions in this cluster align with operational readiness, forecasting accuracy, and simulation modelling, reinforcing the AI-dominated focus of the ‘disaster management’ motor cluster from the thematic map. In TOE terms, this work supports preparedness and early response and is strongly oriented to the technological context (data intensity, model performance, sensor coverage). In contrast, organisational and environmental conditions, such as responsibilities for maintaining models, embedding forecasts into pre-positioning or routing decisions, and the institutional capacity of public authorities and communities, are rarely theorised in depth. This leaves the pathways from improved prediction to community resilience only partially specified, highlighting a key area for future case-based and action research.

The (ii) environmental monitoring, geographic information system (GIS), and remote sensing (green) cluster centres around Yao et al. (Reference Yao, Liu, Li, Zhang, Liang, Mai and Zhang2017), Tien Bui et al. (Reference Tien Bui, Ho, Pradhan, Pham, Nhu and Revhaug2016), and Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Zhou, Huang, Bi, Ge and Li2016), where it consolidates the geospatial and environmental science orientation of HSC literature. These works often rely on remote sensing data, terrain modelling, and flood detection using satellite and UAV-derived inputs. The scholarly focus here is mainly ecological and spatial, often employing advanced mapping technologies for hazard and disaster assessment and terrain classification. These contributions have clear potential relevance for facility location, access planning, and vulnerability analysis in HSCs. However, they are often framed primarily as environmental or geospatial studies and only occasionally as supply chain research. Organisational and environmental TOE aspects, such as capacity to acquire and process remote sensing data, regulatory access to imagery, and infrastructure constraints, are usually treated as contextual background rather than analytical focal points. This restricts the integration of these tools into decision-making processes in settings with limited resources, thereby clouding their role in enhancing resilience capabilities, such as situational awareness and redundancy.

The (iii) decision-support systems and organisational intelligence (blue) cluster highlighted by Sit et al. (Reference Sit, Demiray, Xiang, Ewing, Sermet and Demir2020) and Tan, Guo, Mohanarajah and Zhou (Reference Tan, Guo, Mohanarajah and Zhou2021) encompasses research related to decision-making algorithms, system interoperability, and ICT-facilitated humanitarian coordination. These studies often utilise system dynamics, multi-criteria decision analysis, or integrated information platforms to enhance the efficiency of responses. Research by Papadopoulos et al. (Reference Papadopoulos, Gunasekaran, Dubey, Altay, Childe and Fosso-Wamba2017), Ahmed et al. (Reference Ahmed, Fumimoto, Nakano and Tran2024), and Bhat et al. (Reference Bhat, Pranaav, Mini and Tosh2021) illustrates this area by creating dashboards, platform architectures, and blockchain-based traceability systems for procurement, warehousing, and distribution.

The (iv) digital humanitarian innovation and sustainability (yellow) cluster is underpinned by Muhammad, Ahmad and Baik (Reference Muhammad, Ahmad and Baik2018), who explored how digital innovation intersects with sustainability-focused humanitarian approaches. This area of research encompasses topics such as blockchain, mobile logistics platforms, and environmentally friendly supply chains, typically discussed in the context of circularity and low-carbon logistics. These studies provide a systems-oriented perspective on digital transformation, bridging technology and sustainability frameworks. However, co-citation links to governance, resilience, and humanitarian theory remain relatively weak, and empirical applications in developing economy contexts are limited. The potential of these technologies to support resilience and justice in resource-constrained humanitarian settings is acknowledged conceptually, rather than examined empirically, indicating an opportunity for longitudinal case studies and action research that follow how TOE configurations, such as those involving blockchain and platform governance, shape local adaptive capacities.

The (v) policy, institutional framing, and governance mechanisms (purple) cluster includes works by authors such as Dubey (Reference Dubey2023), Govindan (Reference Govindan2025), and Papadopoulos et al. (Reference Papadopoulos, Gunasekaran, Dubey, Altay, Childe and Fosso-Wamba2017), who offer a macro-level view of HSC disruption, digital maturity, and crisis responsiveness within institutional and policy logics. These works employ theoretical perspectives such as the resource-based view, institutional theory, and, in some cases, the TOE framework. They provide a macro-level perspective on how digitalisation interacts with organisational capabilities, regulations, and stakeholder expectations. Simultaneously, they are rarely linked in detail to specific HSC technologies or phases, which means that the connection between high-level governance and concrete digital practices remains underdeveloped.

A smaller (teal) cluster covers (vi) emerging AI tools, explainability, and interdisciplinary extensions. It includes recent contributions by authors such as Rieskamp, Mirbabaie and Zander (Reference Rieskamp, Mirbabaie and Zander2023) and Goyal (Reference Goyal2021), who engage with explainable AI, ethics in automation, and interdisciplinary risk forecasting models. These contributions signal growing concern with transparency, fairness, and interpretability in data-driven humanitarian systems. However, they are weakly connected to the main HSC clusters and are seldom applied to full supply chain processes or to the organisational and community contexts in which they are adopted.

Co-citation: intellectual foundations and humanitarian theory

Based on the co-citation analysis shown in Figure 6, a structured intellectual foundation for the digital HSC field emerges, offering distinct but interconnected scholarly communities. These communities, visualised through colour-coded clusters, capture how frequently authors are co-cited together, indicating shared theoretical contributions or methodological alignment. The resulting map highlights the epistemological architecture of the field and identifies its most influential conceptual anchors, which are organised across four clusters.

Figure 6. Co-citation analysis of leading authors in digital humanitarian supply chain research (2015–2025).

The first (i) machine learning foundations and predictive analytics (green) cluster centres around Breiman (2001). Authors are frequently cited in studies using predictive models for disaster risk reduction and early warning systems. The methodological relevance of this cluster is evident in studies by authors such as Rahman et al. (Reference Rahman, Fahim Faisal, Mondal and Mahfuzur Rahman2025), who applied long short-term memory and deep learning to cyclone tracking, and Sreedevi (Reference Sreedevi2020), who modelled tsunami bridge fragility using interpretable machine learning. Conceptually, this cluster strengthens the technological strand of the TOE by offering tools for quantifying uncertainty and improving prediction. It does not, however, address the organisational and environmental conditions under which such models are adopted and used.

The second (ii) deep learning and computer vision for crisis intelligence (red) cluster reflects a growing fusion between HSCs and visual data analytics, with a strong methodological focus on accuracy, transfer learning, and crisis informatics. Co-cited authors in this cluster include Simonyan and Zisserman (Reference Simonyan and Zisserman2014), whose work on convolutional neural networks has shaped computer vision applications in disaster management, such as UAV imaging and situational awareness tools. These methods support remote sensing and real-time mapping as seen in Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Zhou, Huang, Bi, Ge and Li2016) and Wuyun et al. (Reference Wuyun, Sun, Chen, Li, Han, Shi and Zhao2025). The emphasis of this cluster is methodological and technological, with limited explicit engagement with humanitarian theory or with the organisational and political environments in which these systems operate.

The third (iii) social media, big crisis data, and public IS (blue) cluster are linked to the authors of bidirectional encoder representations from transformers, such as Castillo, Diaz, Lin and Yin (Reference Castillo, Diaz, Lin and Yin2016), and highlights a literature trend that employs social media and natural language processing for detecting disasters, filtering misinformation and facilitating communication between humanitarian actors. The strength of co-citation here reflects a transition in the field towards utilising unstructured data and user-generated content. The methodological influences are evident in research that incorporates sentiment analysis and social signal extraction into systems for emergency decision-making, as noted by Krishnappa et al. (Reference Krishnappa, Saraswathi and Chelliah2024) and Lever and Arcucci (Reference Lever and Arcucci2022). This cluster highlights the role of information and communication capacities and begins to touch on behavioural issues such as misinformation and trust. However, connections to HSC decision-making, social capital, and community resilience are rarely developed beyond descriptive analysis.

Finally, the fourth (iv) humanitarian operations, logistics systems, and resilience (yellow) cluster includes seminal works by authors such as Altay and Green (Reference Altay and Green2006), Kovács and Spens (Reference Kovács and Spens2007), and Van Wassenhove (Reference Van Wassenhove2006). The work provides foundational knowledge on HSC for structuring normative and operational dimensions. Recent studies by authors such as Abbasi et al. (Reference Abbasi, Damavandi, RadmanKian, Zeinolabedinzadeh and Kazancoglu2025) build on these principles to model green logistics and resilient distribution under uncertainty. These authors define core concepts, disaster phases, and performance criteria in HLs and have become standard references for structuring HSC research. They provide the main conceptual bridge between the digitalisation-oriented clusters and humanitarian theory. The co-citation analysis, however, indicates that these foundational works are often cited as general background rather than being systematically integrated into the design of digital systems or into the analysis of technology adoption dynamics.

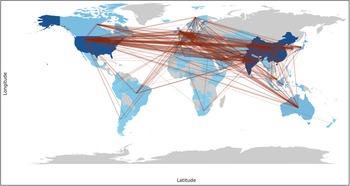

Global collaboration

The global collaboration landscape in digital HSC research shows a structurally core and periphery configuration, characterised by concentrated scientific production and dense collaborative linkages among dominant knowledge economies (Fig. 7). The United States, China, Western Europe, and Australia emerge as central hubs, each exhibiting both high research output and extensive international partnerships. The collaborative ties between the United States and Europe, as well as between the United States and China, form the backbone of global scientific exchange, with visible extensions into Australia and select parts of East and South Asia. These patterns are consistent with broader scientometric trends that emphasise the rise of China as a leading contributor to research in crisis and disaster management, alongside a continued tradition of transatlantic cooperation in this domain.

Figure 7. Collaboration analysis of the corpus on HSCs and emerging technology.

Countries in the Global South generally exhibit lower publication volumes, but the rising contributions from areas such as South Africa, Algeria, and Lebanon indicate a shift towards greater decentralisation in scholarly engagement. While peripheral in terms of output, these regions are becoming increasingly integrated into global research networks. Examples include collaborative links between countries, such as those between Algeria and South Africa, or between Angola and Costa Rica, which, although less frequent, suggest the gradual emergence of South-to-South scientific partnerships. This shift is supported by recent empirical contributions by authors such as Abdelaziz et al. (Reference Abdelaziz, Mesbah and Kholief2025), whose work on disaster risk reduction in North African contexts demonstrates applied relevance beyond dominant geographies, and Rahman et al. (Reference Rahman, Fahim Faisal, Mondal and Mahfuzur Rahman2025), who explored the operationalisation of AI for humanitarian response in climate-affected zones. The dominance of institutions in high-income countries implies that the empirical base for current digital HSC models is heavily shaped by Global North contexts, reinforcing the need for the DHSCRF.

Synthesis of HSC and resilience pathways

Table 1 presents the main digital technology families in keyword co-occurrence, co-citation, and bibliographic coupling. Each row reflects a thematic cluster that recurs across the different bibliometric techniques. The table also clarifies how they interlink with the disaster phases, prevailing TOE, and indicative resilience outcomes.

Table 1. Summary of mapped cluster analysis

Drawing on the preceding bibliometric and theoretical analyses, the proposed conceptual model aims to capture how digital technologies interface with HSCs across the various phases of disaster management under TOE conditions. To capture a multi-phase process of digitalisation in HSCs and align it with resilience-related capabilities, the model is structured around three interdependent domains (as shown in Fig. 8):

i. The technological layer maps digital innovations, such as AI, IoT, blockchain, and simulation tools, to the disaster management phases. It identifies both established and emerging technologies, considering the varied levels of adoption dependent on the phases and geographic areas. From a resilience perspective, it influences communication abilities.

ii. The organisational layer attempts to explore how HSC actors interact with digitalisation, focusing on their internal resources, strategic objectives, and governance frameworks. Engagement methods include investing in digital infrastructure, partnering with technology suppliers, and fostering organisational learning through pilot initiatives. The difference between international organisations and local humanitarian actors highlights the importance of absorptive capacity, training, and institutional memory. This mainly relates to skills and institutional abilities within frameworks for community resilience.

iii. The environmental layer situates the concept of digitalisation within broader ecosystem factors, including regulatory structures, the availability and accessibility of infrastructure, priorities and interests of donors, and the stability of the socio-political environment. Furthermore, digital adoption is influenced and defined by supportive and restrictive factors, where resilience is reliant not only on technology but also on effective systemic coordination and legitimacy.

Source: Authors’ own work underpinned by Kruger and Steyn (Reference Kruger and Steyn2023) and Tornatzky and Fleischer (Reference Tornatzky and Fleischer1990).

Figure 8. The conceptual digital humanitarian supply chain resilience framework (DHSCRF).

Discussion

This study explores how digital technologies are conceptualised and utilised within HSCs in the context of disaster management. It specifically highlights both theoretical and practical trends that may inform digital transformation in vulnerable and resource-constrained settings, which are often found in countries in the Global South. Consequently, a DHSCRF has been developed, based on a comprehensive bibliometric analysis and interpreted through the TOE framework. This framework offers an integrated model that combines disaster management processes, technological clusters, and conditions for adoption into a well-structured system-level structure.

The bibliometric analysis shows that current research predominantly emphasises disaster response, with a significant focus on AI, drones, and real-time decision-support systems (Imran et al., Reference Imran, Castillo, Diaz and Vieweg2015; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Kumar and Yao2020). However, the disaster management phases: preparedness, recovery, and resilience-building remain underexplored. This is especially concerning, as the systemic transformation relies on developing adaptive capacities that extend beyond the immediate responses to disasters (Altay et al., Reference Altay, Kayadelen and Kara2024; Madianou, Reference Madianou2019). The proposed DHSCRF aims to shift the focus back to often-neglected disaster management phases by introducing a phased interaction model that links digital adoption to specific capabilities and limitations across the disaster management lifecycle phases. In line with Dubey et al. (Reference Dubey, Gunasekaran, Bryde, Dwivedi and Papadopoulos2020) and Akter and Wamba (Reference Akter and Wamba2019), the findings highlight the significance of technological maturity (interoperability, data availability), organisational capability (skills, digital governance), and environmental readiness (policy support, infrastructure access). This triangulation affirms the relevance of the TOE framework, utilising 4IR technologies as outlined by Kruger and Steyn (Reference Kruger and Steyn2023), in explaining the variability in digital adoption, especially in the Global South and among African and low-income settings, where digital adoption faces challenges due to infrastructure fragmentation and insufficient institutional coordination.

This conceptual model further extends the literature by explicitly mapping disaster management phases to their most prominent technologies and adoption conditions. For example, blockchain was primarily associated with the recovery phase, used for fraud mitigation and beneficiary tracking (Biswas & Gupta, Reference Biswas and Gupta2020), whereas simulation tools and mobile-based learning featured in the resilience phase (Golan et al., Reference Golan, Jernegan and Linkov2020). These phase-specific configurations provide a more detailed understanding of how digitalisation functions as a system-wide enabler rather than a single-point intervention.

Theoretical contribution

Theoretically, this study contributes to HSCs, disaster management, and digitalisation in several ways. First, a conceptual lifecycle framework is provided that situates digital technologies within a multi-phase and multi-actor HSC environment, addressing the prevailing bias towards response-centric research. Second, a holistic view of the knowledge structures within the HSC field is offered through the application of bibliometric triangulation, which helps a data-driven synthesis of thematic clusters (Aria & Cuccurullo, Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017). Third, the DHSCRF conceptual model emphasises the importance of integrating organisational dynamics, such as digital governance, internal capability development, and inter-agency collaboration, into technology adoption frameworks, which expands a behavioural and relational layer to the original TOE model. Lastly, environmental constraints, such as policy incoherence and infrastructure gaps, are explicitly integrated into the framework, which encourages scholars to account for institutional and regulatory contexts, addressing calls by Altay et al. (Reference Altay, Kayadelen and Kara2024) and He et al. (Reference He, Shirowzhan and Pettit2022) for more context-sensitive theorisation. In addition, the bridge between digital adoption theories and humanitarian outcomes is strengthened by prioritising community resilience and drawing from other humanitarian theories, as well as connecting the DHSCRF with TOE contexts to specific resilience-related capabilities.

Practical implications

This study provides several actionable insights to HSC practitioners and actors, technology developers, and policymakers concerned with digitalisation in low-resource settings. Practical guidance is provided through the various innovative digital tools that have been identified, which can be implemented in HSCs. Managers are further assisted not only in deciding on the specific tools that can be adopted, but also in determining the sequence and under which organisational and environmental conditions, through the DHSCRF framework, these tools are translated into phase-specific configurations. When these technologies are adopted, HSC actors can enhance overall coordination, transparency, and decision-making efforts in resource-constrained contexts. This framework provides donor organisations and multilateral organisations with a diagnostic tool to assess digital readiness across the various phases of disaster management. Interventions can be customised according to the type of technology and unique organisational and environmental factors that support or obstruct adoption, such as those in Africa.

For example, blockchain technology is suited for secure, well-funded settings with robust digital governance. Simultaneously, mobile simulation platforms provide scalable options in resource-constrained settings, specifically after a disaster has occurred. It is further possible to use low-fidelity blockchains, but they necessitate context-specific application examples. By implementing these innovative tools and strategies, HSC actors can improve their disaster management preparedness, facilitate and promote the sharing of real-time information that will enhance humanitarian response efforts, and ultimately enable these actors to achieve their common goal of alleviating the suffering of disaster victims, preserving lives, and fostering a more resilient HSC. When the DHSCRF is applied, it can assist humanitarian organisations in overcoming digital adoption challenges and barriers by outlining the organisational skills that need to be developed, the partnerships that need to be established, and the obstacles that must be addressed to effectively translate specific technologies into improved humanitarian outcomes.

This framework also suggests that resilience-building should be a fundamental aspect of HSC strategies. Rather than primarily focusing on the immediate efficiencies in logistics performance, humanitarian actors should allocate resources to invest in creating feedback mechanisms, establishing data-sharing infrastructure, and supporting long-term capacity development. The initiatives may target local communities, which often face exclusion from advanced technological solutions due to various financial, regulatory, or a lack of adequate skills and knowledge. In African settings, where notable disparities in educational and infrastructure resources exist, this framework emphasises the necessity of customising digital solutions to meet local needs and address their limitations. This includes developing low-bandwidth technologies, decentralised governance models, and hybrid digital–analogue systems that support both formal and informal actors. This can enable HSCs to be both digitally ready and human-centric.

Ethical considerations

Digitalising HSCs raises ethical concerns that go beyond data protection and operational risk. Authors warn that the convergence of digital innovation with existing humanitarian and market structures can reproduce colonial patterns of dependency and control, a process that Madianou (Reference Madianou2019) terms ‘technocolonialism’ (the use of biometrics, platforms, and data infrastructures in ways that extend surveillance and experiment on refugee populations). From a digital justice perspective, Heeks (Reference Heeks2021, Reference Heeks2022) argues that the central risk in many Global South contexts is not exclusion from digital systems but ‘adverse digital incorporation’, where more powerful actors disproportionately extract value from the data and digital labour of less advantaged groups. In HSCs, this implies that digital platforms for beneficiary registration, tracking, and coordination can entrench power asymmetries if they are designed and governed without meaningful participation from crisis-affected communities and local organisations. Recent analyses of digital humanitarian data practices similarly highlight how decisions about what constitutes data, who can access it, and how it is interpreted are often made by international actors, producing ‘humanitarian ignorance’ about local priorities and lived realities (Fejerskov et al., Reference Fejerskov, Clausen and Seddig2024). For managers and policymakers, the ethical challenge is therefore to treat digitalisation not merely as a technical efficiency project but as a governance issue: ensuring that digital tools in HSCs are embedded in accountable data-governance arrangements, minimise harm and unequal extraction, and support rather than displace local agency and community resilience.

Conclusion

This study framed how digital technologies are being integrated into HSCs across the disaster management lifecycle. By analysing 4,780 peer-reviewed publications from 2015 to 2025, the study maps the intellectual terrain and thematic evolution of this rapidly developing field. The findings highlight a predominant focus on response-phase technologies, particularly AI, drones, and decision-support systems. It also exposes underexplored areas in preparedness, recovery, and resilience-building.