Introduction

There is today a growing ecosystem of memory mediation that often goes further than memorialisation and heritage-building. Comics are undoubtedly part of this movement, with their multimodal verbal-visual storytelling form tending to prompt layered responses from reader-viewers, who find themselves surprised, moved, and transformed by that experience. Comics, too, engage in strategic forms of memory-making, including what Armstrong and Crage (Reference Armstrong and Crage2006) have described, in the context of the Stonewall riots, as the active construction of memory by individuals or subgroups in social movements. Indeed, comics can carry strong symbolic notions and emotions and, as a form, have been closely connected to histories of revolts and countercultures. In this article, we aim to explore this memory mediation using the theoretical framework of transformative learning, taking as a case study a one-page comic. This multimodal page is a strong example of transformative learning and its impact on memory. It is not the intention of this article to make broader claims about all comics in general. Instead, we aim to analyse the various ways in which memory mediation works in a specific multimodal context (the one-page comic) using the framework of transformative learning.

The anonymous one-page comic laying out the impact of agriculture’s industrial organisation in France was shared on the communication channels of a French ecologist movement called Les Soulèvements de la Terre (The Earth Uprisings). This umbrella organisation, along with its sister organisation, the Bassines Non Merci collective, has gained significant public visibility in France by coordinating local mobilisation against mega-bassins (open water reservoirs). Both are now widely associated with direct action. As an open coalition of very different groups and actors, including what the website describes as ‘trade unionists, farms, collectives of inhabitants in struggle, autonomous collectives, environmental groups, citizens’ associations’ (our translation), the structure of the movement seems to defy all quick categorisations and understandings of a collective, as it aims to self-organise as a decentralised network of multiple local groups. This is in essence an environmentalist and anti-capitalist coalition. These collectives have served as platforms encouraging political organising and solidarity at the local scale. Les Soulèvements articulate three gestures as: 1) standing against land grabbing, 2) standing against artificialisation of soil, and 3) standing for an ecology without transition periods, for the spontaneous reengagement of civil society in the land attribution process (Soulèvements de la Terre website, 2025). They assert that water is a public good and denounce its subsidised preventive storage by large farms incentivised to tailor their production for export. The comic was circulated via a mailing list arriving directly into Gramond’s inbox and published on the Telegram Channel of Bassines Non Merci three days after the large demonstration where our non-fiction comic page is set. The one-page comic was included in the email from the newsletter of Les Soulèvements de la Terre (23 July 2024). It was also shared earlier that day on the Telegram channel used to inform the participants of the simultaneous week-long gathering called Le Village de l’Eau. The targeted audience for this comic therefore presumably shares a vision of effective political mobilisation supporting a diversity of tactics not limited to civil disobedience. In all likelihood, the intended reader-viewer of the comic page is then someone with first-hand experience and particular memories of demonstrations and peer-learning around these deep-felt social struggles.

The overall structure of the comic studied here (Figure 1 and Figure 3 for the translation) follows a dialogue between two characters (seemingly, a bull and an egret), which progresses from the top left to the bottom right corner of the page. In the top part of the comic, the animals are shown attending a demonstration at the port of La Palice in La Rochelle on 20 July 2024. The central part of the page is occupied by a very large bubble illustrating the ties between the multiplication of mega-bassins and the enlargement of the industrial harbour of La Rochelle. The construction of mega-bassins then appears to feed into a production model favouring the creation of wealth over regional food sovereignty in the context of the climate crisis. This official discourse is questioned by the bull and the egret, who decide, in the last panels, to rebel and take action.

Figure 1. Anonymous, ‘From Sainte-Soline to La Rochelle, Immediate Reflection on a new Step of the Anti-Bassin Mobilisation’ (translated from French), from the newsletter of Les Soulèvements de la Terre (lessoulevementsdelaterre.org).

Note: A full translation of the one-page comic is available at the end of the article (translation by the authors).

The page acts simultaneously in three key ways. First, as the commemoration and memorialisation of a specific event, in this case the protest of 20 July 2024 near the industrial harbour of La Rochelle; second, as an educational contextualisation of that event (a broadening of the issue); and third, as a call for further action. As such, a discussion could be had on whether an umbrella group such as Les Soulèvements de la Terre should be qualified as ‘activist’. The group highlights social issues that are asking for a general mobilisation and a shift in society’s positioning. They share an ambition to bring together as broad a representation from civil society as possible (as detailed above). Their more generalist perspective and the aggregative nature of the composition of the group can put this term of ‘activism’ into question. However, the form of some of their targeted actions, such as occupations and demonstrations, shows that they use the tools of activism. Furthermore, their aim – that is, to bring about political and social change in the relationship with ecology and climate change – brings them in line with academic definitions of activism. As such, it is a good example to address our central questions of how multimodal constructs such as this one-page comic facilitate the process of transformative learning and how such multimodal forms allow one to move from memory-making, crystallising a specific event, to an amplification of engagement that leads to collective action. In short, it allows us to study the specific mechanisms and affordances that multimodal modes of communication, such as comics, possess as tools for transformative learning.

The key basis of our analysis lies in the concept of transformative learning, which has been conceptualised in many ways over recent decades and has often been connected to multimodality. The figure perhaps most associated with the concept, Mezirow (Reference Mezirow, Sutherland and Crowther2006, Reference Mezirow, Mezirow and Taylor2009), defines transformative learning as the transformation of a learner’s frames of reference and habits of mind. In the case of our example, the habitual thinking about mega-bassins as a need for the local agricultural industry is challenged and connected instead to global capitalist structures. Building on Mezirow, professor of lifelong learning Illeris (Reference Illeris2014) proposes a definition of transformative learning that is somewhat broader and links it to matters of identity more firmly. To him, transformative learning changes the individual’s identity (social or individual). By attempting to push the reader into action, our example engages with this shift of identity in the reader-viewer. Professor of continuing education Jarvis (Reference Jarvis and Illeris2009) focusses on the processes that trigger transformative learning and that impact the cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions of an individual. Illeris also broadens the target area of transformative learning beyond the cognitive to the social and emotional dimensions. In doing so, Illeris and Jarvis connect transformative learning to multimodality, emotions, and social aspects, all present in our case study.

Multimodality is another key concept in our analysis. For noted comics theorist Thierry Groensteen, comics is before all a language (Groensteen, Reference Groensteen2007, 19), a relational system of interdependent images and text that combines a ‘collection of codes’ (6). Thus, for him, it is a comic’s ability to circulate between codes that allows its efficiency. Indeed, this is precisely the ability of the one-page comic under scrutiny to circulate between codes and play with multimodal communication that allows it to engage reader-viewers in memory-making processes. Furthermore, Nicole Doerr posits that ‘various mnemonic practices such as story, image, discourse, and performance interact with each other, conditioning social movements’ future’ (2014, 207). That way, she connects memory-making and multimodality, one of the main features of comics as a language. The analysis of our case study is therefore premised on Barthes’ semiotics (Barthes, Reference Barthes and Barthes1977), as it allows us to investigate a multimodal system (text/image). Barthes’ semiotics takes into consideration the denoted content (that is, the literal iconic and linguistic messages) and connoted content (that is, the symbolic iconic and linguistic messages). In doing so, it unveils layers of entangled literal and symbolic codes contained on the comic page. This interpretative blueprint for image analysis is, according to Barthes, especially adapted to frank visual sources such as advertisement images and visual political communication, as their constitutive signs are transparent in their interpretation out of necessity (Reference Barthes1964, 40). To supplement Barthes’ approach and focus more specifically on the impact on the reader-viewer, we looked not to the fields of comics or education, but to the field of exhibition design. Comics as a multimodal form of communication has many common points with exhibition design engaging audiences through various sensory and cognitive channels and playing a role in (collective) memory-making processes. Tiina Roppola, in her 2012 book Designing for the Museum Visitor Experience, presented a framework to analyse exhibition design for impact on visitors, which gives us some tools to analyse the impact of our case study on reader-viewers. Specifically, her analysis of four relational processes – framing, resonating, channelling, and broadening – is particularly relevant to comics design and impacts the potentially transformative nature of comics in narratives of hope and resistance.

Finally, the work of theorist Sara Ahmed on emotions and political struggle offers a central analytical tool for our article, to scrutinise the transformative processes of learning and engagement in the one-page comic about the demonstration of 20 July 2024. In her writings, she highlights how emotions form the basis of shared social identities and proposes recognising such emotions as a valuable common ground for political organising. Ahmed’s work on affect connects to the work of comics studies contextual scholar Mickwitz (Reference Mickwitz2016), who is interested in the potential of comics to go beyond verbal witness accounts to share experiences. She thus sees comics in relation to documentary-making and as having an archival function in relation to collective memory. Comics can then act as a form of affective material connection between ‘imagined communities’ (following Anderson, Reference Anderson2006). Social movements and comics have a long history of connection, allowing for a particular type of emotional impact on reader-viewers and on the activation of memory. Similar to Mickwitz (Reference Mickwitz2016), our article posits a strong connection between individual and collective memory, identity, and comics (61). Comics that focus on the (often emotional) representation of historical events, as well as the building of a collective identity through visual recognition, can serve as a material bridge between memory and social movement. Berger et al. (Reference Berger, Scalmer, Wicke, Berger, Scalmer and Wicke2021) also draw a firm connection between social movement and memory and look at how they impact and shape each other. They suggest that drawing on emotions can be one of the strategies linking memory and activism. Berger et al. (Reference Berger, Scalmer, Wicke, Berger, Scalmer and Wicke2021) further outline five strategies to connect memory and activism: the use of repertoires of contention, the focus on historical events, the use of the concept of generation as well as that of collective identity and the draw on emotions. Also, to them, social movements rely on memory and identity work, work that according to Ahmed is closely connected to the use of emotions.

In the following, we have divided our discussion into three theoretical categories, each providing the starting point for our detailed analysis of the ‘Sainte-Soline to La Rochelle’ comic as a potential multimodal transformative tool. In the first section, we investigate the different types of relational engagement that can lead to transformative learning in comics through the framework created by Roppola (Reference Roppola2012). In doing so, our key example allows us to identify the mechanisms that comics can employ in their function as a multimodal tool for transformative learning such as coexisting (and unstable) frames, resonating through culture-specific references, emotional channelling, or scaling up the issues at hand. The second section then expands the work of Illeris in light of the work of Sara Ahmed to focus more specifically on emotions and their role in transformative learning, looking at the way that this one-page comic engages with emotions as signs of normative societal assessment, constructs emotions as social, and presents them as signs of healing testimony. Finally, we build on Jarvis and Illeris to look at the specific mechanisms supporting transformative learning in our one-page comic, specifically, creating a disjunction, giving meaning to that disjunction, practising real or imaginary resolution, and engaging in identity formation.

A comic’s multimodal types of engagement with the reader-viewer

Although, as mentioned in the introduction, Roppola (Reference Roppola2012) presented a framework to analyse exhibition designs in terms of their impact on visitors, we believe that her distinction and analysis of four interrelated processes – framing, resonating, channelling, and broadening – are particularly relevant to comics design and impact the potentially transformative nature of comics in narratives of hope and resistance. The expository nature of both exhibitions and comics, their multimodal nature merging textual and visual languages, and their communicative use of space mean that Roppola’s framework translates well into comics analysis. We will therefore use her framework here to distinguish between various transformational types of engagement a reader-viewer might have with a comic.

Translated to comics, the first of Roppola’s relational processes, framing, has to do with the overall organisation and expectation negotiation taking place in the pictorial space. It explores and analyses the relationship between the experience of the reader-viewer and their expectation of the form and overarching codes of comics in general. While in a museum space Roppola encourages us to study the framing through the use of spaces, rooms, and concept organisation, in the comics realm we can look at the use of space, linearity, narrative, and conceptual organisation. Roppola’s second relational process, resonating, translates particularly well from the museum space to the comics page. Resonating is a type of engagement that allows displays (in our case, image/text) to ‘mesh’ with the reader-viewer and ‘achieve some level of kinship’ (2012, 124). Such an engagement aims to ignite a close relationship with the reader-viewer and can relate to bodily, emotional, and social engagement. Channelling, Roppola’s third relational process, is a type of engagement that builds a relationship of directedness and cohesion with the visitor-reader-viewer. Roppola states that ‘channels are conduits by which visitors are assisted through the museum, or pathways visitors construct using their own agency’ (2012, 174). In comics, such pathways translate as spatial, visual, and narrative channelling. Roppola’s final type of relational process is broadening. To Roppola, it applies to the ‘content-related meanings’ visitors derive from their visit (2012, 216) and can be experiential, affective, conceptual, and discursive. This type of engagement works particularly well for socially engaged display/comics. Roppola’s four processes will now be employed to consider the comics page under study.

Framing

Several framing devices are competing in the ‘Sainte-Soline to La Rochelle’ comic page. The first is that of the traditional narrative comic, telling the relatable story of the bull and the egret. The second framing device is that of infographic, where data are visualised in an educational manner and for a didactic purpose. Finally, the one-page format also uses the frame of the poster or political flyer. These three coexisting frames – daily adventure, educational, and political – put the reader-viewer in a space that creates and destabilises the reader-viewer’s frames of reference and habits of mind, opening the possibility for transformative processes to take place.

Furthermore, this comic offers a specific overall political positioning (to the left). This is visible in the image with the graffiti ‘Zad partout’ on the mega-bassin itself. Zad stands for the French ‘zone à défendre’, areas to be protected. Such protection zones are illegally occupied by members of the public as a form of opposition to capitalist development. While there is an awareness of the criticism against such actions, the comic page takes a strong political stance. Another such detail is the bird highlighting the ‘cercle infernal’ (infernal circle/cycle) from the mega-bassin to the world food market and back. The materialisation of causality is reinforced by the looping in this central section. The framing of the comic therefore plays on two levels: that of the overall versatile form of the comic using various visual structures to place itself in daily, educative, and political frames; and that of the specifically left-wing political framing using visual signs such as the ‘Zad partout’ graffiti to position itself. Framing in this comic page – through the use of space, linearity, narrative, and conceptual organisation – contributes particularly to the meaning-making process of the reader-viewer’s transformative experience. The framing of this comic supports both the commemoration and memorialisation of the protest as well as the contextualisation of the event.

Resonating

Resonating – that is, meshing bodily, emotionally, and socially with the reader-viewer – is dependent on the culture of the audience. The comic can propose some connections and make offers of engagement, but the success of the resonating process will depend greatly on the reader-viewer themselves. As Barthes highlights, ‘the knowledge on which this sign depends is heavily cultural’ (1977, 35). For example, the egret, or heron, is a relatively familiar bird to French audiences that can evoke the idea of birds flying and hunting freely in wetland areas. Its connoted message can be that of an undomesticated free character. Similarly, the animal characters of the bull and the egret will evoke strongly (again for the French reader-viewer) the idea of the fable, such as the fables of La Fontaine, where both animals appear. The connoted message is then that the imaginary animal characters carry a moral lesson for us to learn. While this message and resonating potential will be clear to a large part of the French audience, another part of the audience may not be able to understand it, and the resonating will not take place.

Similarly, the visual reference at the beginning of the comic to 1968 French political posters, with its anonymous silhouetted crowd and raised fists will resonate in a certain way to reader-viewers who recognise that reference. Indeed, the connoted message here is one of youth and rebellion, of a search for social justice and freedom. Such associations will resonate with the reader-viewer, elicit specific emotions and encourage a certain type of active engagement. Resonating, by creating some level of kinship through a multimodal web of references, allows for an emotional exploration on the part of the reader-viewer. It certainly has a role to play in the identity shift taking place during the reader-viewer’s transformative encounter with the comics. Resonating processes contribute to the amplification of the engagement of the reader-viewer, tapping into individual and collective memory.

Channelling

The channelling in the comic page is carried by its overall structure. The left-to-right reading of the top section on the La Rochelle demonstration is then followed by the circular reading of the middle section, which is strongly directed by visual devices such as the mega-bassin hose, the arrows, and its overall round shape. That section also contains some focussing devices, such as the magnifying glass-shaped panel. The last section, which moves from left to right, from a black zone to a white zone, recentres the gaze on the final panel and the fictional resolution: the passage to action. The reading of the comic is carefully curated to direct the reader-viewer from various emotional states and through various tones and arguments. Through spatial, visual, and narrative channelling, the comic page takes the reader-viewer from memory-making and the crystallisation of the protest to an educational contextualisation of the event, pushing for an amplification of engagement to a call for collective action. Channelling is meant to engage the reader-viewer in a specific way that contributes to meaning-making processes supporting the emotional journey and transformative impact on the reader-viewer.

Broadening

The final type of engagement in Roppola’s model, broadening, is very concretely marked in the comic page. The comic begins from a specific place, date, and demonstration (that is, Port La Palice in La Rochelle) and expands space throughout the comic: with the mention of other specific locations such as Sainte Soline, the map of France, and the world globe. It connects the locations together and shows how the issue at hand manifests itself at different scales. Broadening participates in the processes of transformative learning by expanding the understanding of the reader-viewer beyond the localisation of the issue towards a global understanding of agricultural markets and dependencies. It contributes to meaning-making but also to transformative processes, by scaling up the issue. As such, it encourages an amplification of the engagement that directs the reader-viewer towards collective action.

These relational processes – framing, resonating, channelling, and broadening – create in this comic various forms of multimodal transformational engagements with the reader-viewer that converge towards a shift in identity and set the reader-viewer in motion towards action. Such forms of engagement are supported by the way in which emotions are shared in comics.

Shared emotions in comics

Illeris (Reference Illeris2004) proposes a broadening of the target area of transformative learning to emotional and social dimensions. This shift in the understanding of the relations between cognition, emotions, and social is supported by the foundational works of affect theory. Indeed, in The Cultural Politics of Emotions (2014), first published in 2004, Sara Ahmed offers a new outlook on emotions, identity, and self/other distinction. For Ahmed, and for Brennan (Reference Brennan2004), ‘affects and emotions neither go from the “inside out” nor come from the “outside in”; rather, emotions may be found within the very atmosphere of the social’ (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Willett and Meyers2021). Emotions, as they describe them, are neither generated completely internally nor received from outside. Rather, they take shape along/within the social fabric that surrounds us. This decentring of the subject as the site of the emotional activity comes with a new understanding of emotions as being ‘not only about the “impressions” left by others’ but also as engagements with established social norms (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2014, 196).

In looking at the whole formed by social and emotions, Ahmed also suggests that emotions concern how we relate to each other and how we relate to social norms. She asserts that those who resist established social structures – including queer communities and feminists, and by extension, activists –have ‘a different affective relation to those norms, partly by “feeling” their costs as a collective loss’ (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2014, 196). In other words, the opposition to the social norms upholding the different systems of oppression is always supported by a shared emotional relationship to these social norms. In this relationship, people relate emotionally to each other, to the hardship of others and to the social norms they recognise as the origin of this hardship. Comics can then potentially become the physical trace, the archive of a collective memory of a shared emotional experience. In Ahmed’s framework, injustice is accompanied by emotions that should be recognised as effects or signs of injustice. As Ahmed considers the emotions and suffering that can result from injustice, she is clear that not all instances of negative emotions, affects, bad feelings, or suffering are necessarily the consequences of injustice. She emphasises that emotions are not the ground of the contestation of oppressive social norms but that the ground is the injustice that preceded the emotions. It is this injustice that the one-page comic attempts to put forward through a different lens (memory of an event, contextualisation of that event, and call to action).

In the conclusion of The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Ahmed encourages us to ‘respond to injustice in a way that shows rather than erases the complexity of the relation between violence, power and emotion’ (2014, 196). This can include learning to be attentive to the emotional social relations she describes but also learning to expose ourselves collectively to the emotions via which injustice wounded us. She further calls this political/emotional practice ‘the work of exposure’ and references truth commissions that utilise collective storytelling to process trauma and confront historical injustice. For her, exposure to collective testimony, with the moment of hearing and the following moment, can be healing, and she insists that, while it cannot become the goal of political struggle, ‘feeling better’ is not a superfluous luxury, especially when dealing with structural injustice (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2014, 200–201). Comics, with their work of memory mediation and their capacity to appeal to collective emotions, play a part in this ‘work of exposure’, where we take time to look at the scar, the healing work, as a reminder of how injustice shapes ourselves and our communities (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2014, 202; Davies, Reference Davies, Davies and Rifkind2020).

Emotions as part of a normative societal assessment

The educative central section explaining this state-sponsored organisation of agriculture is a good example of the use of didactic material for transformative learning, as defined by Illeris. In fact, Illeris aims to advance ‘the most advanced kind of human learning’ for ‘working actively and determinedly with liberation and empowerment’, namely ‘understanding the hidden power structures behind the oppression’ (Illeris, Reference Illeris2014, 149). With this large central speech bubble, the reader-viewer is presented with a downward cycle powered by economic growth and running with little consideration for justice. The water of the mega-bassins is shown to predominantly sustain large-scale industrial agriculture, with half of the French cereal production being exported. The cereals are transited through the silos of the industrial harbour, where they acquire commodity status and become subject to market volatility and speculation. The dominant discourse – personified through the Mr Monopoly figure and the anonymous infographic style of that part of the comic – presents this export orientation as unavoidable, thereby advantaging sector actors eager to develop their activities internationally. Interjections such as ‘PRODUCE MORE!’ and ‘GIVE ME MORE!’ reinforce the emotional oppression created by the visual codes through the use of boldface and punctuation. The institutional and private actors represented in the comic show the rigid framework of French agricultural production in which farmers are pushed to increase their productivity, notably by watering their fields more. The comic page explicitly credits ‘free trade’, ‘predatory pricing’, and ‘financial speculation’ for their infringement of the food and water sovereignty of people in France. The comic page, by illustrating the mechanism by which these forces drive the evolution of the industrial organisation of agriculture in France, identifies precise instances of what Illeris calls hidden oppressive power structures – that which Ahmed would call oppressive social norms. The comic page uses a word and image combination to elicit emotions of indignation and expose the injustice of this situation.

On top of denouncing precise capitalist logics, the comic mentions industrial groups – ‘Total’, ‘Lafarge’, and ‘Bolloré’ – and also introduces the reader-viewers to less-known actors, like the company operating the silos at La Rochelle harbour. The explicit mention of the names of those three multinationals triggers in the reader-viewer preexisting (shared) emotions of anger towards these actors. In the bull’s second speech bubble, the cost of the current organisation of agriculture is phrased as ‘the SUBJUGATION of peasants’, ‘the construction of MEGA-BASSINS’, ‘the speculation on food’, and ‘the INTOXICATION of the WOOOOOORLD???’. The four phrases gradually move towards a presentation of the loss as a collective loss. The emotion is conveyed through typographical signs such as the capping of some words, the extension of some letters to emphasise the tone and the punctuation. This way, the matter of the cost of that industrial organisation on people, while being explicitly and pedagogically explained in the bottom part of the loop, is emphasised and personalised as it is voiced in the dialogue between the two animal characters. It creates an emotional personalisation of the issue and fosters empathy. Emotion becomes part of a normative societal assessment and is presented as both individual and collective.

Emotions as social emotions

The animals’ dialogue after the loop, in the third section, arguably has the potential to bring this political topic back into the wider context of our emotional social relations. By showing the toll this structural organisation has on smaller (and bigger) farmers, this comic reasserts that the struggle for water and food sovereignty coincides with the most pressing social questions in the French public debate. The reader-viewer may not relate to the bull’s bewilderment, but the different marks of emotion that were included may serve to legitimise the different affective relation to oppressive social norms mentioned by Ahmed. There is, for instance, the shaking of the bull, the multiplication of punctuation marks, the widespread use of all caps, the sharp-edged screaming bubbles, the duplication of the egret and the use of boldface in the very last scene. The comprehension by the reader-viewer of the animal characters’ emotions is the result of a synthesis of these textual (typography) and graphic codes that nuance each other.

The characters of the bull and the egret react emotionally to a collective/social loss, with the reader-viewers then confronted with a loss that is presented as one they share. For Ahmed, it is certainly those emotional reactions to structural injustice that, shared and experienced collectively, accompany the contestation of the harmful norms at work. The testimony that represents this comic page gives an occasion for those who attended the demonstration to remember the intense stress, exhaustion, and strong emotions that were caused by the especially forceful and violent police assault on the demonstrators. Co-author, Pierre Gramond, attended the demonstration in La Rochelle on Saturday, 20 July 2024, where he witnessed an unprovoked offensive by the riot police with tear gas and batons, after a long moment of kettling demonstrators already suffering from the high temperature. Those painful memories, along with more cheerful ones, could also be part of a discussion with others about this comic, which can easily be sent as a smartphone message. The comic can then act as the catalyst for the sharing of testimonies, extending the exposure work well past the wake of the demonstration. The one-page comic under scrutiny does the ‘work of exposure’ by going beyond the witness account and sharing emotions and contextualising the experience in a multimodal way, as advocated by Mickwitz (Reference Mickwitz2016), and as such connects individual and collective memory.

Emotions in the healing testimony

While the comic does not appear to grant a prominent place to the representation of shared emotions, the lack of colouring can suggest to some reader-viewers the trying nature of the situation depicted. At first sight, the page looks somewhat serious and sober. The black background, possibly representing the density of the crowd, can also be interpreted as the ‘CAPITALIST BLACK TIDE’ referred to in the final scene, the demonstrators surfacing from this ambient capitalism. The spelling of the noun marée is changed with the addition of another r, causing the last r of the following adjective noire to resonate, accentuating the alliteration and potentially leading the phrase to appear more menacing. The choice of this metaphor draws a comparison between the evolution of the organisation of agriculture with a very visible kind of manmade catastrophe that no one could possibly applaud. The metaphor of the catastrophe is also not without a possible sense of optimism; while being tragic, the aftermath is rarely thought of as insurmountable. The comic page here proposes a form of healing testimony by associating a surmountable event with the destruction of capitalism. It proposes an emotional journey through the posture of the bull from anger to action. As proposed by Berger et al. (Reference Berger, Scalmer, Wicke, Berger, Scalmer and Wicke2021), the comic draws on emotions to link memory and activism.

In summary, the ‘Sainte-Soline to La Rochelle’ comic page evidently plays a role in the emotional and political work of exposure through the testimony form and emotional dialogues. It entrenches the La Rochelle demonstration in the collective memory by setting the narration in the context of the protest, it provides didactic material identifying several instances of injustice, and it encourages a move to action that acknowledges the cognitive and the social-emotional dimensions of the reader-viewer’s identity. In this manner, it enriches a particular collective memory/imaginary relative to going to demonstrations and makes public a well-articulated collective understanding of the organisation of agriculture in France. It shows how the multimodal conveying of individual and collective emotions is key to the transformative potential of comics.

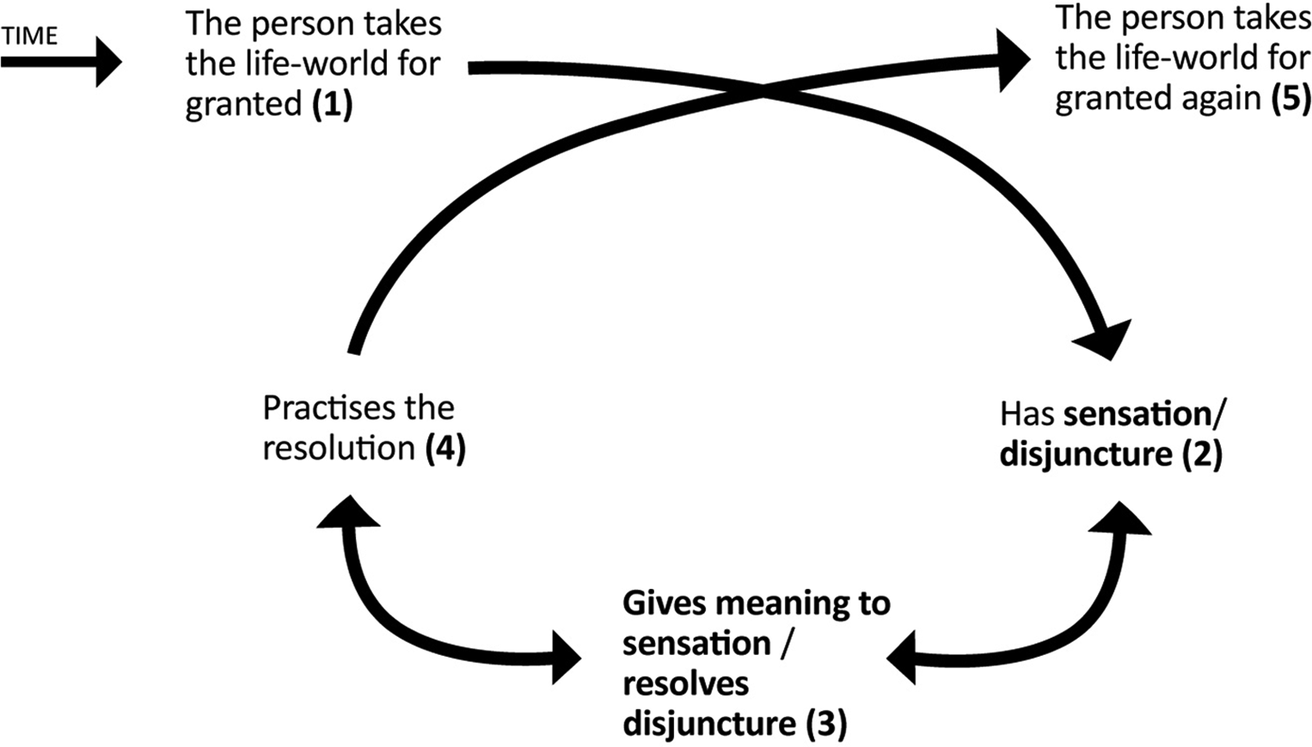

Processes of transformative learning: From disjunction to meaning-making and resolution

For Peter Jarvis, ‘all human learning begins with disjuncture—with either an overt question or with a sense of unknowing’ (2009, 22). He describes transformative learning as a gradual process of engagement. As has been summarised in Figure 2, according to Jarvis, a person takes their life-world for granted until there is a disjuncture. The disjuncture can take many forms; for example, it can be a conversation, an artwork, an experience or reading a comic page. This disjuncture then needs to be given meaning by the learner. This process of meaning-making can be internal or external, but it is always a key step in the process of transformation. Finally, a resolution is practised to allow the individual to readjust their perception of the world and carry on taking their life-world for granted, having integrated new knowledge. In that process, the identity of the learner has been impacted: transformative learning has taken place.

Figure 2. Learning, according to Peter Jarvis, design by Bullitt identity.

Building on Jarvis, Illeris (Reference Illeris2014) conceptualises transformative learning and focusses on disjunction as a tool for transformation and activation. Illeris’s definition of transformative learning links it with matters of identity. He identifies the target area of transformative learning (that which is transformed) as covering ‘the cognitive, the emotional and the social dimensions’ (Illeris, Reference Illeris2014, 151).

We argue that the combination of sensory channels mobilised in the reading of comics creates a layered disjunction, which has an increased impact on the reader-viewer. As such, we want to investigate Doerr’s (Reference Doerr, Baumgarten, Daphi and Ullrich2014, 219) multidimensional perspective on memory and look at how different mnemonic forms (visual and verbal) interact, whether in a complementary or contradictory way, to reinforce the process of transformative learning. Indeed, the verbal-visual storytelling in comics creates stronger dispositives of empathy-building and identification that enhance the role of emotion, creating a memory system where the collective and the individual, as well as the past and present, collide. In the following, we will consider how this plays out in the ‘Sainte-Soline to La Rochelle’ comic.

Disjunction

Comics, because of their ability to create alternative realities and to confront the reader-viewer with such constructed worlds, can create very efficient forms of disjunction. In the comic page under study here, the world presented gradually creates a sense of responsibility in the reader-viewer. This comic page can then act as a disjunction, as a productive activator of the reader-viewer.

The comic starts with rather comfortable and familiar imagery and textual forms: the representation of the demonstration evokes the famous 1968 posters with their simplified silhouettes and raised fists. Moreover, the animal characters are reminiscent of children’s book illustrations and comics, and the traditional dialogue bubbles allow for an easy reading into the scene. The reader-viewer is therefore led to expect entertainment. However, the comic page gradually changes tone for the reader-viewer – a shift in framing as we examined in the first part of the article.

In the second (central) section, the infographic format and information-packed presentation contextualise the La Rochelle demonstration and put the fight in a broader context of mass food production and consumption. The process of convincing the reader-viewer is taken seriously: there are precise statistics, and the exploitation processes from the mega-bassins to the intensive cultivation of cereals are clearly exposed, using a didactic-expository strategy with a step-by-step explanation translated in the structure of the comic itself.

The last section generates responsibility in the reader-viewer by showing a personification of capitalism as Mr Monopoly and drawing the emotional response of the animals, expressed through their faces and accentuated by the punctuation in the text bubbles, where capitalised words and multiple vowels are used to show emphasis – as investigated in the second part of the article. Are we, as reader-viewers, players in this Monopoly game; are we responsible for this capitalist system; and what can we do to stop it? The moral dilemma is resolved in the rather violent final frame, a call to action to kick Mr Monopoly – that is, capitalism – out of the comics grid.

The comic uses the flexibility of its form (iterative discursive) and the versatility of its verbal and visual languages (from poster visuals, to children’s book animal characters, to infographic data, to a board game character) as a trigger to shift and destabilise the existing life-world of the reader-viewer. The connoted message of the overall comic is that the situation is urgent and we are no longer willing to accept this. It aims to create a disjunction in the life-world of the reader-viewer and engages the process of transformative learning. It mobilises the emotional shift (from comfort, to anger, to action, and between individual and collective), the framing shift (from harmless entertainment to educational to action), the broadening, channelling, and resonance to destabilise the existing frames of reference and habits of mind and therefore identity perception of the reader-viewer.

Giving meaning

In her book Graphesis (Drucker, Reference Drucker2014), Johanna Drucker differentiates between images that produce knowledge – images that generate new forms of knowledge – and images that display existing knowledge – images that make visible a specific interpretation. We argue that comics tend to hold both these roles simultaneously and thus give the reader-viewer elements to create meaning, based on both existing knowledge and new knowledge, from that disjunction. In the ‘Sainte-Soline to La Rochelle’ comic, this is particularly apparent in the middle section, which contains statistics and a lot of explanatory information. Its overall circular structure, following the watering hose of the mega-bassin and the black-and-white arrow ribbon through a clockwise path, explains the connection and dependence between the phenomenon of the reservoirs and international food market developments. Two zoomed-in magnifying glass-shaped panels, focussed on the functioning of the port and of mega-corporations, offer even more information.

This section of the comic uses a multimodal and multilayered educational approach to encourage the reader-viewer to read more and to inform themselves, to learn details of the overall capitalist food system, and to give meaning to the disjunction created by the comics – indirectly by the demonstration in La Rochelle. Once again, the comic uses the familiarity of the form – specifically, infographics and ‘did you know’-type panel inserts – to create didactic material. The connoted message of this section is to inform yourself and understand the intricate dependencies. It aims to engage the reader-viewer into a process of meaning-making, going beyond the disjunction created in the reader-viewer’s life-world.

Practising resolution: Taking action

The final frame functions as a call to action, a call to practice resolution. Its text in boldface and all caps completes its symbolically charged image. The bull – shown in profile, with steam coming out of its nose and in a charging position – seems to be kicking Mr Monopoly out of the comics grid. The action is reinforced by the horizontal lines that create movement and imply the violence of the shock between the two characters. The only traces left of Mr Monopoly are the flying hat and money bills scattered in the wind. The connoted message of this last frame is to take action, violently if it needs be, to effect change.

This invitation to action is also connected to the larger social movement ‘engagement machine’ that the comic is part of. This comic was received in the context of a newsletter from Les Soulèvements de la Terre titled ‘From Sainte-Soline to La Rochelle, Immediate Reflection on a New Step of the Anti-Reservoir Mobilisation’ (our translation). This newsletter was received three days after the demonstration in La Rochelle, although the comic was also published (earlier) that day on the Telegram Channel of Bassines Non Merci. This passage from the real-world demonstration to the fictional world in comic form allows for a cognitive development space and the creation of an imaginary around the demonstration. It anchors a real-life event – the La Rochelle demonstration – as foundational; it provides layers of information in an accessible format; and it invites imaginary action along with the bull and sends the reader-viewer back to real life, transformed and ready to act.

Identity

Through engaging the reader-viewer in these processes, the comic form potentially offers a means to engage in a transformation of the reader-viewer’s very identity. Illeris proposes that the ‘target area of transformative learning’ (2014, 153) is identity. While the concept of identity has evolved through the 20th and 21st centuries (Giddens, Reference Giddens1991), it is broadly understood to have two core interlinked components: 1) personal identity, how we perceive and identify ourselves and our individual qualities; and 2) social identity, how we identify with larger social entities or groups (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978; Morales et al., Reference Morales, Huici, Seyle, Swann and Gomez2009). Comics can address both aspects through two systems: one is empathy-building and identification, and the other is the creation of social links and signifiers of togetherness.

Empathy-building and identification systems are about the positioning of the reader-viewer in relation to the ‘voice(s)’ of the comics page. It has to do with the fact that the reader-viewer can recognise themself and thereby empathise with the comic characters. Animalisation (or anthropomorphism) is one of the tools often used in children’s books to foster empathy and give space for reflection. While creating a comfortable distance from the reader-viewer, animalisation of characters encourages care and a comparison with a character clearly placed in the realm of fiction (Sitzia, Reference Sitzia2018). They allow for a projection onto the character while building one’s own identity in regard to that of the ‘other’ (Sitzia, Reference Sitzia2018). In our comic, the bull and the egret stimulate empathy through self-identification or projection while reminding the reader-viewer of other mailing lists and calls to action (to protect animals, for example). The reader-viewers are sent back to themselves, having to identify their own personal identity traits by comparison: Are they like the egret, full of knowledge, or like the bull, eager for action?

A reader-viewer’s social identity is reinforced by the comics’ ability to create social links and signifiers of togetherness. This layer of identity is about the reader-viewer’s relationship to others. Social psychologists have identified a close link between narration and identity formation (Gillis, Reference Gillis and Gillis1994; Holstein and Gubrium, Reference Holstein and Gubrium2000). Comics become a memory system where collective and individual memories/narratives collide. In our comic, there is a duality in the reader-viewers audience: those that were at the La Rochelle demonstration and those that were not. For the former, the comic crystallises a memory, turning it into a foundational event. For the latter, it creates an imaginary of the demonstration. In both cases, the historical event at La Rochelle becomes an identity anchor, an amplifier, and a push to act. As noted by Berger et al. (Reference Berger, Scalmer, Wicke, Berger, Scalmer and Wicke2021), focussing on historical events can be a strategy to connect memory and activism in order to build a collective memory that contributes to a collective social identity. The comic page then becomes the link between memory and the social movement – that is, the bridge between memory, the past and the present – and reading the comic becomes a signifier of togetherness.

In summary, by engaging with processes of transformative learning (creating a disjunction, giving meaning to that disjunction, practising real or imaginary resolution, and impacting identity formation), the multimodal form of comics allows for various senses to interact and to impact on the cognitive, emotional, and social realm of the reader-viewers.

Conclusion: The transformative potential of multimodality

This article identified methodological devices and employed them, through the given example, to analyse the mechanisms of this one-page comic as a potential tool for transformative learning. Our analysis showed how multimodal languages such as this one-page comic can facilitate processes of transformative learning and how they can allow readers/viewers to move from memory-making, to focussing on a specific event, to an (emotional) amplification of engagement that potentially can lead to an identity shift and collective action. As such, we showed that comics can potentially be an integral part of the growing ecosystem of memory mediation in narratives of hope and resistance related to activist practices.

In the first section, we focussed on multimodality and showed how Roppola’s framework allows for a better understanding of the types of relational engagements that can trigger transformative learning in the reader-viewer. Roppola’s distinction between framing, resonating, channelling, and broadening allowed us to define the impact specific elements of the comic have on the reader-viewer and how this contributed to transformative processes. We note that throughout our analysis, all elements converged towards a shift in identity and set in motion the reader-viewer, a movement towards action. In the second section, we showed how theories of affect, Ahmed’s in particular, are complementary to such approaches and how emotions (individual and shared) are an important factor to take into consideration in the transformative potential of comics in memory-making and socially engaged contexts. Finally, we showed the processes of transformative learning that comics can trigger as agents of memorialisation and activation of the reader-viewer. We showed how such processes in comics (disjunction, meaning-making, practising resolution) can lead to a shift in the identity of the reader-viewer.

In this article, we focussed on the impact of comics on reader-viewers, but one could also look further at the author-illustrator and how the process of comic-making becomes part of the transformative processes outlined here. Fisher Davies (Reference Fisher Davies2019), for example, has initiated this investigation by presenting five choices available to the author-illustrator: choice of character design, choice of ‘verb style’, choice of framing, choice of density, and choice of metonymy. Further research on this topic would likely be fruitful.

The article pushed us to question what activism is and what it looks like in comic form. Is activism a specific practice of engagement, or is it more about a collective form of citizen society rather than a tightly driven core of individuals? How is this reflected in the form of the comics? Is this responded to in the kinds of comics narrated: a singular (super) hero vs a collective representation? How are these individual and/or collective memory/ies anchored in the comics grid? What is certain is that the flexibility of comics language allows it to fit the particularity of each social movement, to find a new system to trigger, engage, and activate the reader-viewer.

One important way in which the comic page we looked at sets itself apart is with its choice of scale. Indeed, the illustrator(s) attempted to represent the structure of French agriculture in a single drawing with its main actors and how they influence each other. This ambitious project, associated with the form of comics and its general orientation towards fiction and world-building, allows for a less objective and academic narrative than what could be expected from left-wing political movements. This enables the comic to communicate in a more personal and efficient way with its audience. This anonymous comic page displays the strength of comics: the density of the image/text, the temporal bridges, its ambitious scope contained in a structured single page adapted to sharing knowledge and (digital) distribution. As ‘the boundary between past and present becomes particularly leaky’ (Mickwitz Reference Mickwitz2016, 72), the comic system shows here its efficiency for activist purposes bridging past events, present ‘laws of the market’ or future rebellion. It plays an integral part in lifelong transformative learning.

Figure 3. Anonymous, ‘From Sainte-Soline to La Rochelle, Immediate Reflection on a new Step of the Anti-Bassin Mobilisation’ (translated from French), from the newsletter of Les Soulèvements de la Terre (lessoulevementsdelaterre.org).

Note: This is a full translation of the one-page comic (translation by the authors). Our translation focussed on staying close to the original wording while making the text easy to read for as many English speakers as possible. When the wording chosen deviates from the available literal translation, it is to prioritise the comprehension of the lexicon and overall framework of thought of the French ecologist and anti-capitalist movement. The persuasive approach and tone taken by this instance of political communication also influenced our translation choices.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the article (no specific data were created outside of the analysis presented in the article).

Funding statement

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Open access funding provided by Maastricht University.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Emilie Sitzia (University of Amsterdam/University of Maastricht) is a professor of Illustration – word/image at the UvA and of cultural education at UM. Her research interests include word/image interdisciplinary studies, digital and sensory education, museum participatory practices, polyvocality, storytelling, identity, and multimodality in space, in text, and in images.

Pierre Gramond (University of Amsterdam) is a graduate student in cultural studies. Their research interests include the observation of the visual means of communication used in a context of popular education, and the integration of (shared) emotions in militant outreach.