Introduction

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) increasingly internationalize to access growth opportunities, diversify demand, and overcome domestic market constraints (Lu & Beamish, Reference Lu and Beamish2001; Sui & Baum, Reference Sui and Baum2014). Yet internationalization exposes SMEs and closely related small-firm forms (for example, international new ventures and born globals) to pronounced uncertainty because they often expand with limited resources, limited foreign market experience, and restricted access to high-quality information (Bruneel, Yli-Renko & Clarysse, Reference Bruneel, Yli-Renko and Clarysse2010; Puthusserry, Khan, Knight & Miller, Reference Puthusserry, Khan, Knight and Miller2020; Schwens & Kabst, Reference Schwens and Kabst2009). Learning is therefore central to SME internationalization, not only through firms’ own trial-and-error experience but also through what firms can infer from observing others’ actions and outcomes (Johanson & Vahlne, Reference Johanson and Vahlne1977, Reference Johanson and Vahlne2009). This review focuses on vicarious learning, defined as an indirect learning process through which SMEs update internationalization beliefs and decisions using others’ outcomes, behaviors, or narrated experiences, rather than relying primarily on their own trial and error. Accordingly, the review treats vicarious learning as a knowledge pathway shaping SMEs’ internationalization decisions and outcomes (Baum, Sui & Malhotra, Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2023; Casillas, Barbero & Sapienza, Reference Casillas, Barbero and Sapienza2015; Tsang, Reference Tsang2020).

In organizational learning research, vicarious learning is positioned as a form of knowledge acquisition that complements experiential learning by enabling firms to update beliefs and routines using second-hand information (Huber, Reference Huber1991). This definition includes both observation-based inference (e.g., peer performance cues, imitation of entry choices, diffusion patterns) and socially mediated forms in which advisors, intermediaries, or diaspora and business networks transmit and help interpret others’ internationalization experiences (Coviello & Munro, Reference Coviello and Munro1997). Institutional diffusion and mimetic pressures are treated as vicarious learning when firms infer appropriateness or viability from others’ visible adoption or success (even when legitimacy motives are salient), whereas purely coercive compliance without inference from others is outside the construct boundary. Network and advisor involvement is treated as vicarious learning when it conveys second-hand experience and interpretation, but when network variables capture only access or embeddedness without specifying second-hand informational content, they are treated as enabling conditions rather than a distinct learning mechanism. The definition excludes experiential learning-by-doing (e.g., learning-by-exporting) and formal training contexts.

In SME internationalization, this matters because firms can rarely observe causal mechanisms directly. Instead, they interpret partial signals from competitors, peers, institutions, intermediaries, and network actors, then decide whether and how to translate these signals into commitment decisions. Critically, the value of such learning depends on a firm’s capacity to recognize, assimilate, and apply externally sourced knowledge, which is often discussed through absorptive capacity (Cohen & Levinthal, Reference Cohen and Levinthal1990; Zahra & George, Reference Zahra and George2002). These foundations suggest that vicarious learning should be treated as a mechanism that is both consequential and conditional in resource-constrained internationalizing firms.

Despite its intuitive relevance, research on vicarious learning in SME internationalization remains fragmented in ways that constrain cumulative theory development. The construct space is dispersed across partially overlapping labels and theoretical traditions, including observational learning, learning from others, benchmarking, imitation, and institutional mimicry, often reflecting different assumptions about who is observed and what is learned (Cheng & Yu, Reference Cheng and Yu2008; Li & Ding, Reference Li and Ding2013; Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015; Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey & Elango, Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). Some studies emphasize inference from peers’ performance signals (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2023; Baum, Sui & Malhotra, Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025), whereas others treat learning as imitation of strategic choices such as entry mode or location decisions (Fernhaber & Li, Reference Fernhaber and Li2010; Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). A further stream frames learning as conformity to mimetic pressures, where firms adopt internationalization practices perceived as legitimate or increasingly prevalent within a field (Butkevičienė & Sekliuckienė, Reference Butkevičienė and Sekliuckienė2022; Cheng & Yu, Reference Cheng and Yu2008; Li & Ding, Reference Li and Ding2013). This dispersion makes it difficult to compare findings across studies and to specify mechanisms and boundary conditions with precision.

The literature does not yet offer an integrated account of when vicarious learning is enabling versus constraining. While learning from others can reduce search costs and support decision-making under uncertainty (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2023; Fourné & Zschoche, Reference Fourné and Zschoche2020), it can also generate mixed or adverse outcomes when firms overreact to observed signals or when the informational basis of imitation is weak. This risk is consistent with broader arguments on imitation and herding, where reliance on others’ actions can amplify errors and produce convergence on suboptimal choices (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee1992; Lieberman & Asaba, Reference Lieberman and Asaba2006). In internationalization contexts, imitation may also be driven by legitimacy-seeking as much as efficiency-seeking, aligning with institutional explanations of isomorphism and legitimacy (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Suchman, Reference Suchman1995). The reviewed evidence echoes these concerns: peer performance signals can be associated with different survival outcomes depending on how SMEs translate them into export market entry intensity (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025), and reliance on imitation varies with experience and information-processing capacity (Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). These patterns motivate a synthesis that treats vicarious learning as contingent rather than inherently beneficial.

Substantial heterogeneity in operationalization limits conceptual clarity and cross-study comparability. Some studies capture vicarious learning through peer outcome signals such as performance growth (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2023, Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025), others through diffusion of internationalization modes or entry patterns (Fernhaber & Li, Reference Fernhaber and Li2010; Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015), and others through network-mediated access to external knowledge and spillovers (Aharonson, Bort & Woywode, Reference Aharonson, Bort and Woywode2020; Al-Laham & Souitaris, Reference Al-Laham and Souitaris2008; Fernhaber, McDougall-Covin & Shepherd, Reference Fernhaber, McDougall-Covin and Shepherd2009). Qualitative studies further suggest that what firms describe as vicarious learning is frequently socially enabled through diaspora and business networks, advisors, intermediaries, and ecosystem actors, making the learning process more interactive than the term ‘observation’ may imply (Fletcher & Harris, Reference Fletcher and Harris2012; Fuerst & Zettinig, Reference Fuerst and Zettinig2015; Pellegrino & McNaughton, Reference Pellegrino and McNaughton2015; Stoyanov & Stoyanova, Reference Stoyanov and Stoyanova2021). Together, these inconsistencies signal the need for a mechanism-oriented synthesis that explains how different vicarious learning channels map onto different internationalization decisions and outcomes.

Accordingly, this study asks: How does vicarious learning influence SME internationalization decisions and outcomes, and under what boundary conditions does it enable or constrain internationalization? To address this question, we conducted a PRISMA-guided systematic literature review (SLR) and thematic synthesis of peer-reviewed research on vicarious learning in SME internationalization. Our synthesis organizes the evidence into four recurring mechanisms that clarify who SMEs learn from, what they observe, and how learning is enacted, providing a foundation for more cumulative theorizing.

This review makes three contributions: (1) it consolidates fragmented conceptualizations of vicarious learning in SME internationalization into a coherent set of mechanisms that clarifies who SMEs learn from, what they observe, and how learning is enacted; (2) it synthesizes recurring boundary conditions (for example, experience, interpretive capacity, absorptive capacity, and network position) that explain when learning from others enables versus constrains internationalization decisions and outcomes; and (3) it develops a forward-looking agenda for construct harmonization, measurement, and multi-level designs that can strengthen causal inference and cumulative theorizing in this domain.

The next section outlines the conceptual background and clarifies how vicarious learning relates to neighboring constructs in internationalization research. The Methods section details the PRISMA-based search and screening procedures. The Results section presents a descriptive mapping of the evidence base followed by thematic synthesis. The paper concludes with implications and a future research agenda for advancing cumulative knowledge on vicarious learning in SME internationalization.

Linking the conceptual anchoring to the review’s synthesis logic

Building on these distinctions and theoretical lenses, this review treats vicarious learning as a multi-channel process through which SMEs acquire internationalization-relevant knowledge from external referents, signals, and socially structured contexts. To guide data extraction and coding, we use four broad channels as an organizing framework: inference from peer performance outcomes, imitation of leader or peer strategic choices, responses to institutional mimetic pressures, and network- and advisor-mediated learning through intermediaries, clusters, and diaspora and business networks.

In this review, vicarious learning refers to acquiring internationalization-relevant knowledge by observing and interpreting other actors’ behaviors, strategies, or outcomes, and drawing inferences that shape the focal firm’s decisions. We include evidence only when learning involves (a) an observable external referent and (b) interpretive inference about what to do. On this basis, we exclude:

• Experiential learning and learning-by-exporting, where knowledge is generated primarily from the firm’s own activities, experimentation, or exporting experience.

• General market research or information scanning that is not anchored to others’ behavior, strategies, or outcomes.

• Pure spillovers or diffusion without observation and inference, such as automatic knowledge transfer via labor mobility or technological spillovers.

• Formal training, consultancy, or education that does not involve learning from observed peers, role models, or referent firms.

These boundary rules guided screening decisions and informed the construction of the typology in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual space of vicarious learning in SME internationalization: what is observed and why firms learn from others.

Institutional diffusion and mimetic pressures are treated as vicarious learning mechanisms when firms use others’ adoption and visible success as informational cues about what is appropriate, expected, or viable, even when the underlying motive is legitimacy. Network- and advisor-related processes are treated as vicarious learning when they transmit second-hand experience and provide interpretive support that helps SMEs convert observed cues into decisions. When network variables capture only access or embeddedness without specifying second-hand informational content, they are treated as enabling conditions that shape the visibility, credibility, and interpretability of the other vicarious learning mechanisms rather than a distinct learning mechanism in their own right.

These channels are not assumed to operate in isolation. Rather, the reviewed literature suggests that firms may combine performance benchmarking with network-based learning or mix imitation with legitimacy concerns, depending on context and resource constraints. Importantly, prior studies also imply that vicarious learning can be enabling, neutral, or detrimental depending on contingencies such as competitive intensity, international experience, interpretive capacity, tie strength, absorptive capacity, and network visibility. Consistent with this framing, the Results section first maps how vicarious learning is conceptualized and operationalized across studies and then synthesizes mechanisms and boundary conditions linking learning from others to internationalization decisions and outcomes. Figure 1 summarizes these distinctions and provides an organizing framework for extraction and synthesis.

Method

This study employed an SLR to synthesize evidence on vicarious learning in SME internationalization. The review followed PRISMA 2020 guidance to ensure transparency and replicability across identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion decisions (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald, McGuinness, Stewart, Thomas, Tricco, Welch, Whiting and Moher2021).

Search strategy and information sources

A comprehensive search was conducted up to December 2025 to identify peer-reviewed journal articles and review papers published between 2000 and 2025. Although the earliest study in the final included set was published in 2007, we retained 2000 as the start year to avoid imposing a post hoc cutoff and to ensure that any earlier eligible studies, if present, would be captured systematically under the review’s construct-boundary and population criteria.

Although vicarious learning is inherently interdisciplinary (spanning international business, entrepreneurship, economic geography, and sociology), this review intentionally bounded the search to peer-reviewed journal literature that explicitly connects vicarious or observational learning mechanisms to SME internationalization outcomes within management-relevant indexing coverage. This boundary was set to ensure consistent journal quality control, replicability of retrieval, and relevance to management and internationalization scholarship, while keeping the search feasible and transparent. Three databases were searched: Scopus, EBSCOhost, and ProQuest. The search strategy combined three concept blocks: (1) vicarious and observational learning terms (including Social Learning Theory terms), (2) SME and related small-firm population terms, and (3) internationalization-related outcomes. Exclusion terms were applied to remove irrelevant learning domains (e.g., machine learning, classroom-based contexts). Database-specific filters were used to restrict results to English-language, peer-reviewed journal sources (and management-relevant subject filters where available). The database search strings and filters, along with database-level yields, are summarized in Table 1 (Full strings are available in Appendix A.2). In addition to database searching, backward reference checking was conducted by reviewing the reference lists of prominent and highly relevant articles to identify eligible studies that may not have been captured through keyword searches alone.

Table 1. Search strategy summary and yield by database

Note: Full database-specific search strings are reported in Appendix A1.

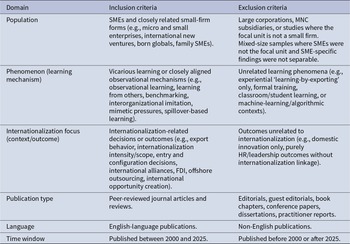

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met all three criteria:

I. Population: Focused on SMEs or closely related small-firm forms (e.g., micro and small enterprises, international new ventures, born globals, family SMEs).

II. Phenomenon of interest: Examined vicarious learning or closely aligned observational mechanisms (e.g., learning from others, benchmarking, interorganizational imitation, mimetic pressures, spillover-based learning).

III. Outcomes: Addressed internationalization outcomes, including export behavior (e.g., export entry intensity, export survival/exit, export performance), internationalization intensity/scope, entry and configuration decisions (e.g., mode/location), international alliances, FDI and follow-up investment, offshore outsourcing, or international opportunity creation.

IV. Mixed-sample rule: Some studies draw on samples that include firms of different sizes. We retained such studies only when SMEs (or closely related small-firm forms such as international new ventures and born globals) were the explicit focal population and/or when SME-relevant findings were clearly interpretable (for example, by reporting SME-only analyses or presenting theory and implications centered on small firms).

Studies were excluded when SME-specific inference was not possible, and the focal unit was effectively ‘firms in general’ or predominantly large firms/MNCs. Studies were excluded if they focused primarily on non-SME populations (e.g., large corporations or MNC subsidiaries as the focal unit), addressed learning phenomena unrelated to vicarious/observational mechanisms, examined outcomes unrelated to internationalization, or were not eligible publication types (e.g., non-peer-reviewed sources). For studies using mixed samples (SMEs alongside larger firms), we retained them only when SMEs or closely related small-firm forms (e.g., born globals, international new ventures, family SMEs) were the explicit focal population and the theory, measures, and implications were clearly interpretable for SMEs, or when SME-specific results were reported separately. Studies were excluded when SME-specific inference was not possible because analyses and conclusions were presented only at an aggregate ‘all firms’ level. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Note: Eligibility was applied during title/abstract screening and full-text assessment, following PRISMA guidance.

Study selection process (screening and PRISMA counts)

The identification stage yielded 76 records from database searches (Scopus = 27; EBSCOhost = 29; ProQuest = 20). An additional 9 records were identified through backward reference checking, resulting in 85 records prior to duplicate removal. Duplicate records were removed using Zotero, eliminating 47 duplicates and leaving 38 unique records. The high number of duplicates reflects substantial overlap in journal coverage across Scopus, EBSCOhost, and ProQuest, meaning the same article was frequently retrieved from multiple databases; the duplicate count refers to duplicate records removed rather than unique studies.

All deduplicated records were screened for relevance, and the full texts of 38 articles were assessed for eligibility. Because the search string and filters were intentionally specific to vicarious learning and SME internationalization, few irrelevant records were retrieved; therefore, exclusions occurred primarily during full-text screening when construct-boundary criteria were applied. During full-text screening, mixed-size samples were assessed using the mixed sample rule outlined in the eligibility criteria. At the full-text stage, 11 articles were excluded for not meeting the eligibility criteria, resulting in a final sample of 27 studies included in the synthesis. Given this modest final yield and uneven distribution of studies across themes, we position the contribution as mechanism clarification rather than field-level consolidation, and we calibrate theme-level claims with particular caution for themes supported by few studies (for example, T3). The study selection process and counts are presented in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 2) (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald, McGuinness, Stewart, Thomas, Tricco, Welch, Whiting and Moher2021).

Figure 2. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram of study identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion for the systematic review of vicarious learning in SME internationalization (2000–2025).

Data extraction and synthesis approach

Data extraction used a structured template designed to support consistent cross-study comparison. For each study, the following information was extracted: bibliographic details (author(s), year, journal), empirical context (country/region and industry), firm type, theoretical lens, terminology and definition of vicarious learning (or neighboring construct), research design and method, operationalization of learning and key variables, internationalization outcome(s), key findings, and boundary conditions/moderators.

The extracted evidence was synthesized using thematic analysis, following an iterative coding and clustering logic to develop higher-order themes (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006; Thomas & Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008). Studies were coded for (1) the learning referent (e.g., peers, leaders, non-peer actors, institutions), (2) the type of signal/cue observed (e.g., outcome-based vs behavior-based), (3) the mechanism through which vicarious learning was enacted, and (4) the internationalization outcome category affected. These coding dimensions are theoretically anchored in established traditions that examine learning-from-others through different explanatory logics, including outcome-based inference in organizational learning (Huber, Reference Huber1991; Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988), behavioral modeling and imitation in social learning theory (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977), legitimacy-seeking diffusion and mimetic isomorphism in institutional theory (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983), and socially embedded learning enabled by network and social capital perspectives (Fletcher & Harris, Reference Fletcher and Harris2012; Puthusserry et al., Reference Puthusserry, Khan, Knight and Miller2020). We use these traditions as complementary, mechanism-relevant lenses that sensitize coding rather than as mutually exclusive or empirically fixed categories.

Two included papers were conceptual contributions rather than empirical studies. These papers were coded using the same template for theoretical lens, terminology, and proposed mechanisms, and were included in theme assignment to support mechanism clarification and agenda-setting. However, they were not treated as empirical evidence when summarizing patterns of outcomes or boundary conditions. Accordingly, statements about observed effects (for example, enabling vs constraining outcomes) and recurring contingencies are grounded in the empirical studies, while conceptual papers are used for framing, triangulation, and identifying future research directions.

Themes were refined through repeated comparison across studies and validated using a theme-by-paper matrix to ensure that each theme was grounded in multiple sources and that each included study was appropriately represented (Appendix A.1). To avoid treating all empirical studies as equivalent evidence, we conducted a structured methodological appraisal of each empirical paper using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT, 2018) as the guiding framework (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Pluye, Fàbregues, Bartlett, Boardman, Cargo and Vedel2018). Consistent with MMAT guidance, we report appraisal patterns narratively to inform evidence-confidence bands rather than presenting criterion-level matrices or numeric quality scores. Each empirical study was first classified into the appropriate MMAT category (qualitative, quantitative non-randomized, or quantitative descriptive) and then appraised through a criterion-based qualitative assessment aligned with the inference demands of this review: (i) design strength for the claims advanced (for example, cross-sectional vs longitudinal), (ii) transparency of sampling and data sources, (iii) clarity and validity of key construct operationalization, (iv) transparency and robustness of analytic procedures, and (v) attention to alternative explanations (for quantitative studies, explicit treatment of endogeneity/identification; for qualitative studies, credibility strategies such as triangulation, reflexivity, and auditability). Studies were then grouped into higher-, moderate-, or lower-confidence evidence bands. This appraisal was not used as an exclusion rule; instead, it informed our evidentiary language (for example, avoiding causal wording where designs do not support causal inference) and the confidence attached to theme-level statements. The methodological appraisal summary and evidence-confidence banding are reported in Appendix A.

Results

Descriptive overview of included studies

Table 3 provides a descriptive profile of the 27 included studies. The evidence base spans 2000–2025, with a clear uptick in publications in recent years (2020–2025: n = 11). The included papers are dispersed across 21 journal outlets (Appendix A.3). International Business Review is the most frequent outlet (n = 4), followed by Global Strategy Journal, Journal of International Business Studies, Management International Review, and Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal (n = 2 each).

Table 3. Descriptive profile of included studies (n = 27)

Note: Two included papers are conceptual contributions. They are retained to support mechanism framing and theme development, but they are not treated as empirical evidence when summarizing outcome patterns or boundary conditions in the thematic synthesis.

Methodologically, the literature is dominated by quantitative designs (n = 19), complemented by qualitative studies (n = 6) and a smaller number of conceptual contributions (n = 2). Data sources range from large-scale administrative records (up to 32,108 SMEs) and secondary datasets to surveys and interview-based qualitative designs (as small as 12 firms and 63 interviews), reflecting substantial variation in empirical granularity and inference. Appendix A.4 (Table A.4) summarizes the methodological appraisal and confidence banding used to calibrate the strength of theme-level claims. We retain the keyword co-occurrence map as a compact descriptive snapshot that contextualizes the thematic synthesis by showing topical clustering and terminology overlap; given the small corpus, we interpret it strictly as triangulating context rather than as a stand-alone bibliometric contribution.

Across studies, the focal firms are most often described as SMEs or small firms, but the sample also includes international new ventures and born globals, family SMEs, and other new-venture forms (e.g., start-ups and young technology-based firms), highlighting the literature’s overlap with entrepreneurship and new-venture internationalization streams.

Empirical settings are concentrated in advanced economies, particularly Germany (n = 5) and the United States (n = 3), with additional evidence from Canada and Italy (n = 2 each) and a long tail of single-country contexts (e.g., the United Kingdom, Spain, France, Taiwan, China, India, Saudi Arabia, New Zealand, Slovenia, and Colombia). Internationalization outcomes are similarly heterogeneous, spanning export outcomes (entry intensity, export intensity, export performance, and export market exit; n = 4), internationalization scale and speed (n = 4), post-entry growth or performance outcomes (n = 4), entry-mode decisions (n = 3), knowledge-oriented outcomes (n = 3), and smaller clusters of work on alliances and FDI (n = 2 each). This diversity supports the need for mechanism-based synthesis to reconcile how vicarious learning is conceptualized and linked to internationalization decisions and outcomes.

Thematic synthesis: mechanisms of vicarious learning in SME internationalization

For transparency and comparability, each theme is presented using a consistent structure covering the mechanism logic, the internationalization outcomes linked to the mechanism, the boundary conditions identified in the evidence, and a brief evidence-strength statement.

Given the modest final corpus (n = 27), evidence support is uneven across themes; therefore, the four themes are treated as interpretive syntheses used to organize how prior studies operationalize vicarious learning, and theme-level claims are calibrated to the depth of contributing evidence, with particular caution where the empirical base is thin (notably T3).

T1: peer performance benchmarking and competitive referencing

T1 positions vicarious learning as inference from comparable firms’ observable performance. Internationalizing SMEs treat peers’ export outcomes, growth signals, and competitive moves as informational cues about market attractiveness and strategy viability, and they use these cues to reduce uncertainty and shortcut search (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee1992; Lieberman & Asaba, Reference Lieberman and Asaba2006; Haunschild & Miner Reference Haunschild and Miner1997). This mechanism is most visible when managers assume peer firms are sufficiently similar for performance comparisons to be meaningful (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2023; Casillas et al., Reference Casillas, Barbero and Sapienza2015; Celec & Globocnik, Reference Celec and Globocnik2017).

Across the included studies, peer benchmarking is linked to variation in export intensity and export entry intensity, and it also helps explain differences in export performance. However, evidence from a small subset of studies suggests that the same performance-referencing may increase the risk of export market exit in specific settings, particularly when firms escalate commitments based on peer cues rather than on their own capability fit (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2023, Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025; Casillas et al., Reference Casillas, Barbero and Sapienza2015; Celec & Globocnik, Reference Celec and Globocnik2017).

T1 is conditioned by the comparability of referent firms, the decision-maker’s interpretive discipline, and the firm’s ability to translate peer performance cues into context-sensitive actions. When firms over-attribute peer outcomes to strategy (rather than context) or chase ‘high-performing’ peers without sufficient analysis, benchmarking can produce overcommitment and adverse outcomes (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025).

Evidence for T1 is based on four quantitative studies. The theme is empirically consistent, but the mechanisms of interpretation and referent selection are not directly observed, which leaves micro-level processes underspecified.

T2: imitation and leader-following in internationalization decisions

T2 captures vicarious learning as modeling observable strategic choices made by other firms, especially firms perceived as leaders. SMEs learn by copying visible decisions such as foreign location selection, mode choice, and expansion patterns, using others’ actions as a template under uncertainty (Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023; Tsang, Reference Tsang2020).

The empirical evidence links imitation to internationalization decisions including international location choice, mode choice, early entry likelihood, and subsequent expansion trajectories such as follow-up FDI growth and performance outcomes after entry (Fernhaber & Li, Reference Fernhaber and Li2010; Fourné & Zschoche, Reference Fourné and Zschoche2020; Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015; Schwens & Kabst, Reference Schwens and Kabst2009; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023).

T2 depends on how decision-makers select referents, attribute success, and judge contextual similarity. Imitation is more likely when information is imperfect, actions are highly visible, and leader firms appear legitimate and successful, but it becomes riskier when copied strategies are not transferable across contexts or when firms imitate without understanding causal drivers (Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023; Tsang, Reference Tsang2020).

Evidence for T2 comes from five quantitative studies across multiple decision contexts (location, mode, entry timing, post-entry outcomes). The pattern is clear, but the literature still lacks strong tests of the cognitive and informational processes that drive leader-following.

T3: institutional mimetic pressures and legitimacy-driven learning

T3 conceptualizes vicarious learning as legitimacy-seeking under institutional uncertainty. SMEs observe which internationalization practices become socially accepted or taken-for-granted and adopt them to gain legitimacy, not only to improve efficiency (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Suchman, Reference Suchman1995). Here, ‘learning from others’ is intertwined with institutional imitation, where conformity becomes a way to manage ambiguity (Butkevičienė & Sekliuckienė, Reference Butkevičienė and Sekliuckienė2022; Canello, Reference Canello2022; Cheng & Yu, Reference Cheng and Yu2008; Li & Ding, Reference Li and Ding2013).

The studies link mimetic pressures to internationalization timing and style, internationalization intensity, and related cross-border strategic choices such as offshore outsourcing entry and duration and strategic responses to institutional demands (Butkevičienė & Sekliuckienė, Reference Butkevičienė and Sekliuckienė2022; Canello, Reference Canello2022; Cheng & Yu, Reference Cheng and Yu2008; Li & Ding, Reference Li and Ding2013).

T3 is most pronounced when uncertainty is high, information is imperfect, and independent evaluation is costly. In such settings, SMEs are more likely to treat prevailing practices as ‘safe’ templates. The mechanism is shaped by institutional pressures and the salience of legitimacy rewards or sanctions in a given environment (Cheng & Yu, Reference Cheng and Yu2008; Li & Ding, Reference Li and Ding2013).

Evidence for T3 draws on three quantitative studies plus one conceptual contribution. The theme is coherent, but empirical operationalizations sometimes blend legitimacy compliance with informational learning, so construct boundaries should be made more explicit in future testing.

T4: network-, cluster-, and advisor-enabled vicarious learning

T4 shows vicarious learning as socially enabled and often mediated through networks, clusters, and intermediaries such as advisors. Rather than passively observing peers, SMEs gain access to others’ experiences through repeated exposure, relational embeddedness, and facilitated interpretation, which makes learning more targeted and context-rich (Fletcher & Harris, Reference Fletcher and Harris2012; Puthusserry et al., Reference Puthusserry, Khan, Knight and Miller2020; Stoyanov & Stoyanova, Reference Stoyanov and Stoyanova2021).

Evidence links network-enabled vicarious learning to a wide set of outcomes including international alliance formation, international market knowledge creation, international opportunity creation, internationalization speed and scope, and post-entry growth patterns (Aharonson et al., Reference Aharonson, Bort and Woywode2020; Fuerst & Zettinig, Reference Fuerst and Zettinig2015; Kauppinen & Juho, Reference Kauppinen and Juho2012; Pellegrino & McNaughton, Reference Pellegrino and McNaughton2015; Puthusserry et al., Reference Puthusserry, Khan, Knight and Miller2020; Stoyanov & Stoyanova, Reference Stoyanov and Stoyanova2021). It also connects to broader innovation and performance outcomes when externally sourced experience can be effectively converted into internal action (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ali, Salam, Bhatti, Arain and Burhan2020).

T4 is shaped by access to high-quality ties, network position and visibility, and the presence of credible intermediaries. Critically, the benefits may depend on absorptive capacity, meaning the firm’s ability to recognize, assimilate, and exploit externally sourced experience (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ali, Salam, Bhatti, Arain and Burhan2020; Cohen & Levinthal, Reference Cohen and Levinthal1990; Zahra & George, Reference Zahra and George2002). This conversion logic is consistent with evidence that externally sourced knowledge yields performance benefits mainly when firms have routines that move from acquisition and assimilation to transformation and exploitation (Perera, Sinha & Gilbert-Saad, Reference Perera, Sinha and Gilbert-Saad2026). However, this contingency is directly tested in only a subset of the included studies, and in other work, it is implied through interpretation rather than explicitly modeled. Weak internal conversion routines can limit performance gains even when exposure is high.

T4 is supported by 14 studies and shows the broadest evidence base, spanning quantitative, qualitative, and conceptual work. The breadth is strong, but causal identification varies across designs, so future work should test these pathways with stronger longitudinal and comparative designs.

Summary of themes and evidence strength

Taken together, the evidence supports organizing prior work on vicarious learning in SME internationalization into four analytically derived themes (or mechanism categories) that summarize how studies operationalize and explain learning-from-others in internationalization settings. T1 and T2 capture outcome- and behavior-based inference from visible peers and leaders, T3 captures legitimacy-seeking diffusion under institutional uncertainty, and T4 captures socially mediated learning through networks, clusters, and intermediaries. Across themes, outcomes depend on boundary conditions that repeatedly involve experience and interpretive capacity, network position and signal visibility, and (where explicitly examined in a subset of studies) absorptive capacity and tie strength. These patterns motivate the theory mapping and keyword mapping below, which contextualize the mechanism-based synthesis and highlight where evidence is most mature versus thin.

Theory mapping

Table 4 presents the theory mapping of vicarious learning in SME internationalization across the 27 included studies. Organizational learning perspectives are the most frequently used (n = 9), typically explaining how learning from others complements or substitutes for experiential learning as firms build routines and interpretive capacity for foreign market decisions (Bruneel et al., Reference Bruneel, Yli-Renko and Clarysse2010; Casillas et al., Reference Casillas, Barbero and Sapienza2015; Fletcher & Harris, Reference Fletcher and Harris2012; Tsang, Reference Tsang2020). Institutional and legitimacy perspectives are the second most prevalent (n = 7), most often framed through mimetic pressures and diffusion under uncertainty, highlighting how legitimacy concerns shape internationalization initiation, style, and intensity (Canello, Reference Canello2022; Cheng & Yu, Reference Cheng and Yu2008; Li & Ding, Reference Li and Ding2013; Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015). A smaller subset explicitly draws on social learning theory/social cognitive perspectives (n = 2), emphasizing modeling, referent selection, and observational processes that are socially mediated (Kauppinen & Juho, Reference Kauppinen and Juho2012; Stoyanov & Stoyanova, Reference Stoyanov and Stoyanova2021). One study anchors its core explanation in competitive response logic, using the Awareness–Motivation–Capability (AMC) framework to explain when peer performance cues translate into aggressive exporting and elevated exit risk (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025). The remaining studies draw on a diverse set of single-use lenses (n = 8), including information-based imitation and board-level microfoundations (Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023), the knowledge-based view (Fernhaber et al., Reference Fernhaber, McDougall-Covin and Shepherd2009), network and social capital perspectives (Al-Laham & Souitaris, Reference Al-Laham and Souitaris2008), ecological theory (Fernhaber, Gilbert & McDougall, Reference Fernhaber, Gilbert and McDougall2008), and resource and capability bundles combining RBV, dynamic capabilities, and international entrepreneurship logic (Celec & Globocnik, Reference Celec and Globocnik2017), as well as effectuation-informed accounts of international knowledge creation (Fuerst & Zettinig, Reference Fuerst and Zettinig2015). Although these lenses all speak to learning-from-others, they rest on different assumptions about agency and motivation, ranging from efficiency-oriented inference (organizational and social learning) to legitimacy-oriented conformity (institutional perspectives). Accordingly, we treat the perspectives as complementary, mechanism-relevant explanations rather than as evidence of full theoretical convergence.

Table 4. Theory mapping of vicarious learning in SME internationalization (n = 27)

*Note: Illustrative studies are examples only; the complete mapping of all 27 studies to theory categories is available in Appendix A (theme-by-paper matrix).

A further mapping insight is that ‘vicarious learning’ appears through multiple conceptualizations and operationalizations rather than a single dominant measurement approach. Outcome-based learning is frequently captured through peer performance or success signals (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2023, Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025; Fourné & Zschoche, Reference Fourné and Zschoche2020). Behavior-based learning is commonly operationalized as imitation of strategic choices such as mode selection or location configuration (Fernhaber & Li, Reference Fernhaber and Li2010; Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). A third stream emphasizes institutional cues and mimetic pressures, where learning is entangled with legitimacy and diffusion dynamics (Canello, Reference Canello2022; Cheng & Yu, Reference Cheng and Yu2008; Li & Ding, Reference Li and Ding2013). A further stream treats vicarious learning as network-enabled access to external knowledge, including cluster spillovers, exposure to internationally connected actors, intermediaries, and advisor channels (Aharonson et al., Reference Aharonson, Bort and Woywode2020; Al-Laham & Souitaris, Reference Al-Laham and Souitaris2008; Fernhaber et al., Reference Fernhaber, McDougall-Covin and Shepherd2009; Fletcher & Harris, Reference Fletcher and Harris2012).

Keyword co-occurrence mapping using VOSviewer (descriptive overview)

To complement the PRISMA-guided thematic synthesis, keyword co-occurrence mapping was used to provide a descriptive overview of how the retrieved literature connects vicarious learning to broader SME internationalization conversations. Given the small corpus, the mapping is interpreted strictly as contextual triangulation rather than as a stand-alone bibliometric contribution. The keyword mapping does not constitute theory testing; rather, it provides descriptive contextual triangulation that helps situate the retrieved literature and supports interpretation of the subsequent thematic synthesis. The maps were generated in VOSviewer using full counting and a customized thesaurus to merge clear synonyms and spelling variants, while reducing non-substantive keyword noise (van Eck & Waltman, Reference van Eck and Waltman2010). Keywords were analyzed using co-occurrence of all keywords (author keywords and index keywords, where available) with full counting. A minimum occurrence threshold of 2 yielded a network of 43 keywords organized into four clusters (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Network visualization (keyword co-occurrence).

The network visualization indicates several closely connected topical groupings. One cluster centers on SMEs, exports, export performance, and international markets, alongside market-facing concerns such as competition and risk reduction, indicating that many studies position learning from others within export engagement and performance-related outcomes. A second cluster is organized around internationalization, learning, and knowledge, within which vicarious learning appears as an embedded mechanism rather than a standalone subfield. A third cluster links entrepreneurship, organizational learning, experiential learning, and knowledge acquisition (including born globals and international new ventures), indicating that vicarious learning is frequently discussed alongside other learning modes in entrepreneurial international growth narratives. Relationship-oriented terms such as alliances and cooperation appear more peripheral but remain connected, signaling an adjoining stream where learning is enabled through inter-firm collaboration and exchange.

The overlay visualization (Fig. 4) suggests a gradual shift from earlier export-performance language toward more recent emphasis on learning and knowledge terms, including vicarious learning, consistent with the increasing use of mechanism-oriented explanations in SME internationalization research. Fig. 5 presents the keyword density visualization, highlighting the concentration and prominence of themes within the SME internationalization and vicarious learning literature. Overall, the mapping provides descriptive context that is consistent with, but does not substitute for, the mechanism-based thematic synthesis reported in the Results section.

Figure 4. Overlay visualization (average publication year).

Figure 5. Density visualization (keyword density).

Discussion, implications, and future research agenda

Given the modest corpus and uneven evidence across themes, our contribution is best understood as mechanism clarification that imposes conceptual order on fragmented constructs, rather than as a comprehensive consolidation of the entire field. Synthesizing 27 peer-reviewed studies published between 2007 and 2025, this systematic review set out to explain how vicarious learning influences SME internationalization and under what boundary conditions it enables or constrains internationalization outcomes. Our synthesis suggests that vicarious learning is not a single, uniform process. Rather, vicarious learning is a multi-channel knowledge process that varies systematically in who SMEs learn from, what they observe, how learning is enacted and converted into action, and which outcomes are affected (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2023, Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025; Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). In doing so, the review directly addresses the fragmentation identified in the Introduction by organizing adjacent labels (learning from others, benchmarking, imitation, mimetic pressures, spillovers) into a coherent set of mechanisms and boundary conditions, enabling more cumulative theorizing and more comparable empirical tests (Huber, Reference Huber1991; Lieberman & Asaba, Reference Lieberman and Asaba2006). Because organizational learning, social learning, and institutional perspectives make different assumptions about agency and motivation, our synthesis treats them as complementary but not fully convergent explanations of the mechanisms identified.

Integrating what the field currently knows

To make the synthesis transparent, the Results were organized around four themes, which are used throughout the Discussion as T1–T4: T1: Peer performance benchmarking and competitive referencing (learning from peers’ outcomes and success cues), T2: Imitation and leader-following in internationalization decisions (modeling observable strategic choices), T3: Institutional mimetic pressures and legitimacy-driven learning (conformity and diffusion under uncertainty) and T4: Network-, cluster-, and advisor-enabled vicarious learning (socially mediated learning through intermediaries and embeddedness).

Across the evidence base, SMEs learn from home and host market peers, salient leaders, institutionally visible referents, network partners, intermediaries (for example, advisors), clusters, and even non-peer actors such as MNCs (Aharonson et al., Reference Aharonson, Bort and Woywode2020; Al-Laham & Souitaris, Reference Al-Laham and Souitaris2008; Fletcher & Harris, Reference Fletcher and Harris2012). They observe outcome signals (peer performance, survival, success cues) and behavioral cues (entry modes, location configurations, investment patterns), and the consequences depend heavily on interpretive capacity, experience, embeddedness, and conversion capability (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ali, Salam, Bhatti, Arain and Burhan2020; Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). Across themes, where it is explicitly examined, absorptive capacity functions as a higher-order conversion condition rather than a discrete learning mechanism, shaping whether observed cues are assimilated and exploited once they enter the firm. This pattern aligns with broader organizational learning arguments that second-hand information only becomes valuable when it is interpreted and incorporated into routines and decision rules (Huber, Reference Huber1991; Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988).

Theoretical implications

Theory choice implies mechanism choice, and the field needs more explicit cross-theory integration. Organizational learning work typically explains vicarious learning as capability-building and as substituting for limited experiential learning, with value depending on interpretation and application (Bruneel et al., Reference Bruneel, Yli-Renko and Clarysse2010; Casillas et al., Reference Casillas, Barbero and Sapienza2015; Fletcher & Harris, Reference Fletcher and Harris2012; Huber, Reference Huber1991). Institutional accounts interpret similar empirical patterns as legitimacy-seeking diffusion under uncertainty (Canello, Reference Canello2022; Cheng & Yu, Reference Cheng and Yu2008; DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Li & Ding, Reference Li and Ding2013). Social learning perspectives emphasize modeling and referent selection in socially embedded settings (Kauppinen & Juho, Reference Kauppinen and Juho2012; Stoyanov & Stoyanova, Reference Stoyanov and Stoyanova2021), while competitive response work shows how peer cues can trigger strategic aggression with adverse consequences when capability and commitment are misaligned (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025). A central implication is that future studies should specify which mechanism is being activated (outcome inference, behavioral imitation, legitimacy conformity, network-enabled interpretation) and why that mechanism dominates in a given context, rather than treating ‘vicarious learning’ as a broad label (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). Two cross-cutting implications follow. One implication is that efficiency and legitimacy motives likely co-exist but are rarely theorized jointly, suggesting the need to model vicarious learning as a dual-motive process. A further implication is that microfoundations of interpretation and selectivity remain underdeveloped despite repeated boundary-condition evidence, indicating that future work should unpack referent selection, attribution, and conversion into routines.

Efficiency and legitimacy motives appear to co-exist but are rarely theorized jointly.Peer benchmarking and advisor-enabled learning imply efficiency-oriented inference (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ali, Salam, Bhatti, Arain and Burhan2020; Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2023; Fletcher & Harris, Reference Fletcher and Harris2012), whereas mimetic pressure and imitation streams foreground legitimacy and prevalence cues (Canello, Reference Canello2022; Cheng & Yu, Reference Cheng and Yu2008; Li & Ding, Reference Li and Ding2013). The synthesis suggests SMEs often operate under both motives at once. A stronger integrative approach is to model vicarious learning as a dual-motive process where firms simultaneously infer informational value and manage legitimacy risk, and where experience, governance, and network position shape which motive dominates (Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015; Oliver, Reference Oliver1991; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023; Suchman, Reference Suchman1995).

Microfoundations of interpretation and selectivity remain underdeveloped, despite repeated boundary-condition evidence. Building on the four analytically derived mechanism categories (T1–T4), outcomes depend on (i) how managerial attention is allocated to external cues, (ii) the accuracy of interpretation and transferability judgments, and (iii) the routines and governance structures used to convert observed signals into action. International experience reduces reliance on imitation (Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). Governance characteristics shape information processing and imitation tendencies (Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). Network structure and embeddedness condition what is visible and credible (Al-Laham & Souitaris, Reference Al-Laham and Souitaris2008; Fernhaber et al., Reference Fernhaber, McDougall-Covin and Shepherd2009), while absorptive capacity and tie strength condition conversion into performance (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ali, Salam, Bhatti, Arain and Burhan2020; Cohen & Levinthal, Reference Cohen and Levinthal1990). These patterns indicate that vicarious learning should be theorized less as a generic ‘input’ and more as an interpretive process shaped by microfoundations and organizational routines (Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). These microfoundations are particularly salient for SMEs because bounded attention, resource scarcity, and informal decision processes amplify both the benefits of selective imitation and the risks of over-commitment when benchmarking outpaces capability development. Accordingly, vicarious learning effects should be interpreted as contingent on SME information-processing capacity, prior experience, and routines that evaluate whether observed outcomes reflect transferable causes rather than idiosyncratic advantages.

Practical and managerial implications

The practical implications map onto the four mechanisms identified in the Results (T1–T4). The central managerial message is that vicarious learning can speed up internationalization decisions, but it also creates predictable risks when firms copy visible successes without verifying capability fit, transferability, and institutional motivation.

Our first theme (T1: peer performance benchmarking) shows that peer performance information can be informative, but translating it into aggressive entry intensity can increase exit risk when commitment outpaces capability (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025). SMEs should separate signal monitoring from commitment escalation by staging commitments and testing whether observed peer outcomes reflect transferable causes rather than idiosyncratic advantages (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2023; Johanson & Vahlne, Reference Johanson and Vahlne1977; Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988).

Our second theme (T2: imitation and leader-following) shows that, when SMEs imitate visible location or mode choices, the safest approach is to treat others’ actions as hypotheses that require local validation, rather than as templates to replicate (Lieberman & Asaba, Reference Lieberman and Asaba2006; Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). Because observable success can be a biased learning base, SMEs should actively look for disconfirming evidence and ‘hidden failures’ before copying, rather than infer best practice from visible winners alone (Denrell, Reference Denrell2003).

Our third theme (T3: institutional mimetic pressure) shows that under institutional uncertainty, firms may adopt internationalization practices to gain legitimacy, not because the practices are efficiency-improving (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Suchman, Reference Suchman1995). SMEs should therefore identify which elements are primarily ‘legitimacy-compliance’ (needed to access resources, approval, or acceptance) versus which elements are genuinely performance-enhancing in their context (Canello, Reference Canello2022; Cheng & Yu, Reference Cheng and Yu2008; Li & Ding, Reference Li and Ding2013).

Our final theme (T4: network-, cluster-, and advisor-enabled learning) shows that networks and advisors can accelerate learning, but benefits depend on the firm’s ability to recognize, assimilate, and exploit second-hand knowledge (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ali, Salam, Bhatti, Arain and Burhan2020; Cohen & Levinthal, Reference Cohen and Levinthal1990; Zahra & George, Reference Zahra and George2002). SMEs should prioritize relationships that provide structured interpretation support, not only exposure, and build internal routines that convert external cues into repeatable internationalization capabilities (Fletcher & Harris, Reference Fletcher and Harris2012; Puthusserry et al., Reference Puthusserry, Khan, Knight and Miller2020).

Building on these themes, we translate the implications into a small set of heuristics (simple, experience-based decision rules) that help decision-makers act under uncertainty (Bingham & Eisenhardt, Reference Bingham and Eisenhardt2011). Such heuristics can be particularly useful for SMEs because they translate learning signals into actionable routines without requiring exhaustive analysis. Evidence also suggests that positively framed heuristics can help decision-makers translate limited cues into practical choices under uncertainty, especially when experience and information-processing capacity are constrained (Gilbert-Saad, McNaughton & Siedlok, Reference Gilbert-Saad, McNaughton and Siedlok2021).

Peer performance information can be informative but translating it into aggressive entry intensity can increase exit risk if commitment outpaces capability (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025). SMEs should therefore separate signal monitoring from commitment escalation and establish routines for testing whether observed outcomes reflect transferable causes rather than idiosyncratic advantages (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2023; Huber, Reference Huber1991).

Experience, governance information processing, and reflective routines reduce over-reliance on imitation and improve selectivity in location and mode decisions (Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). This implies that learning benefits can be improved not only by increasing information access but also by strengthening the organization’s capability to interpret, contextualize, and evaluate the transferability of external cues (Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). Here, a useful heuristic is ‘copy the logic, not the template’, by explicitly checking similarity conditions (industry, institutional context, and resource constraints) before adopting visible strategies (Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023; Tsang, Reference Tsang2020).

Networks and advisors can accelerate internationalization learning, but benefits depend on the ability to convert second-hand knowledge into routines and capabilities (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ali, Salam, Bhatti, Arain and Burhan2020; Fletcher & Harris, Reference Fletcher and Harris2012; Zahra & George, Reference Zahra and George2002). SMEs should prioritize relationships that provide structured interpretation support, not only exposure, and invest in absorptive capacity that enables assimilation and exploitation of external knowledge (Cohen & Levinthal, Reference Cohen and Levinthal1990). A corresponding heuristic is ‘learn through ties, but convert internally’, by ensuring clear roles and routines for assimilating and exploiting externally sourced experience rather than assuming exposure alone generates benefits (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ali, Salam, Bhatti, Arain and Burhan2020; Cohen & Levinthal, Reference Cohen and Levinthal1990; Zahra & George, Reference Zahra and George2002).

Across these implications, the key risk consideration is transferability: observed success is not equivalent to causal success (Huber, Reference Huber1991; Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988). SMEs can reduce downside exposure by using staged commitments, pairing external cues with internal capability checks, and reviewing early post-entry signals before escalating resource commitments (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025; Casillas et al., Reference Casillas, Barbero and Sapienza2015; March, Reference March1991; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023).

Limitations of the study

This review has several limitations. First, the evidence base is constrained by database coverage, search-field choices, and an English-language focus, which may exclude relevant work published in other outlets or languages. In addition, because vicarious learning is dispersed across multiple disciplines, relevant studies may also sit outside the journals and indexing categories most visible to SME internationalization and management searches, or may use neighboring labels (for example, diffusion, peer effects, spillovers, or social comparison) without explicitly framing these as vicarious learning. Second, the final sample is modest (n = 27) and weighted toward advanced economy settings, which limits generalizability to emerging-market internationalization contexts. In addition, the modest number of included studies constrains the strength of synthesis claims when subdividing the literature into four mechanisms, and some themes rest on a thin empirical base (notably T3); accordingly, theme-level statements are framed as interpretive syntheses grounded in the included studies rather than as definitive field-wide regularities. The relative absence of emerging-market studies may reflect several non-mutually exclusive factors: (a) construct-label mismatch, where emerging-market research examines analogous processes (for example, imitation, benchmarking, and peer cueing) but does not label them as vicarious learning; (b) outlet and indexing patterns, where relevant emerging-market work is more likely to appear in regionally focused journals or interdisciplinary outlets that are less consistently captured by the selected database filters; and (c) data constraints, since emerging-market settings often have fewer longitudinal or fine-grained datasets that allow researchers to observe peer cues, visibility, and subsequent internationalization sequences. Third, the keyword co-occurrence mapping is interpreted descriptively, and with a small sample, it serves as contextual triangulation rather than a stand-alone bibliometric contribution. Given the modest sample (n = 27), more advanced bibliometric techniques (e.g., co-citation and coupling-based clustering) were not appropriate. Accordingly, we prioritized mechanism-based synthesis and used bibliometric mapping only as descriptive triangulation. Finally, although we provide evidence-strength statements within themes, we include a structured methodological appraisal of empirical studies guided by the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT, 2018) and use it to calibrate the confidence attached to theme-level statements and the strength of evidentiary language (for example, avoiding causal claims where designs do not support causal inference). Accordingly, the synthesis should be interpreted as a mechanism-based integration with confidence calibrated to study rigor, rather than as an unweighted statement of ‘what the literature shows’ (see Appendix A, Table A.4).

Future research agenda

To advance cumulative knowledge, five research directions follow directly from the mechanisms and boundary conditions identified in this review. Given the interdisciplinary dispersion and labeling variation noted above, future reviews could extend coverage by adding additional synonym families (for example, peer effects, diffusion, spillovers, and social comparison) and by deliberately sampling relevant interdisciplinary outlets where emerging-market internationalization research is often published.

The literature uses overlapping labels and heterogeneous operationalization, ranging from peer outcome signals to behavioral diffusion and network exposure (Al-Laham & Souitaris, Reference Al-Laham and Souitaris2008; Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2023; Cheng & Yu, Reference Cheng and Yu2008; Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015). Future work should develop clearer measurement families that distinguish (a) outcome-based inference, (b) behavioral imitation, (c) legitimacy-driven conformity, and (d) network-enabled interpretation, and test whether these represent distinct dimensions or context-specific manifestations of a higher-order construct (Li & Ding, Reference Li and Ding2013; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). This is essential to address the operationalization gap identified in the Introduction.

Studies consistently show that interpretation capacity matters, but the micro-processes remain thinly specified (Oehme & Bort, Reference Oehme and Bort2015; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023). Research can examine how boards and top management teams identify credible referents, attribute causality to observed outcomes, and evaluate transferability, including how cognitive simplification shapes imitation versus independent evaluation (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023; Tsang, Reference Tsang2020). A promising direction is to connect these microfoundations to organizational learning routines and decision rules (Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988).

The evidence demonstrates that vicarious learning can increase risk when firms respond aggressively to peer cues or when imitation produces misfit (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025; Canello, Reference Canello2022). Future research should explicitly model when learning-from-others produces herding or over-commitment, and how these dynamics vary across competitive intensity, information ambiguity, and capability constraints (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee1992; Cheng & Yu, Reference Cheng and Yu2008; Li & Ding, Reference Li and Ding2013; Lieberman & Asaba, Reference Lieberman and Asaba2006).

Methodologically, these questions are well-suited to longitudinal panel and quasi-experimental designs that address endogeneity in social cue exposure. Future studies could use administrative trade or customs panels and model over-commitment as (i) entry intensity escalation, (ii) hazard of export exit, or (iii) post-entry performance volatility, while exploiting plausibly exogenous shocks to peer signals (e.g., policy changes, sudden demand shocks in the destination market, or abrupt peer exit events) using difference-in-differences or event-study logic.

Qualitative studies suggest learning modes evolve over time, shifting from observation to participation and exploration, and interacting with experiential learning (Pellegrino & McNaughton, Reference Pellegrino and McNaughton2015; Puthusserry et al., Reference Puthusserry, Khan, Knight and Miller2020; Stoyanov & Stoyanova, Reference Stoyanov and Stoyanova2021). Longitudinal designs can test whether vicarious learning substitutes for experiential learning early but complements it later, and whether different channels dominate at different stages (Bruneel et al., Reference Bruneel, Yli-Renko and Clarysse2010; Casillas et al., Reference Casillas, Barbero and Sapienza2015).

Beyond descriptive sequencing, panel designs can test stage-contingent substitution versus complementarity using firm fixed effects, dynamic panel models, or cross-lagged structures that track when vicarious learning cues precede commitment changes (and when experiential learning feeds back to reduce imitation). Where feasible, quasi-experimental variation in information availability (e.g., the introduction of export promotion programs, disclosure requirements, or platform-based visibility changes) can strengthen causal inference about when vicarious learning substitutes for direct experience. The broader organizational learning literature suggests such sequencing is fundamental to how routines form and change over time (Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988; March, Reference March1991).

Cluster and network research indicates learning depends on visibility and exposure structures, including spillovers and intermediaries (Al-Laham & Souitaris, Reference Al-Laham and Souitaris2008; Fernhaber et al., Reference Fernhaber, McDougall-Covin and Shepherd2009). Future research can integrate firm-level learning with ecosystem-level visibility conditions and examine how SMEs learn from non-peer referents, when those referents are credible, and how institutional contexts shape what becomes visible and imitable (Aharonson et al., Reference Aharonson, Bort and Woywode2020; Butkevičienė & Sekliuckienė, Reference Butkevičienė and Sekliuckienė2022; Canello, Reference Canello2022). Methodologically, these arguments can be strengthened using panel network data (or time-varying measures of cluster exposure and intermediary ties) combined with designs that isolate exogenous shifts in visibility, such as changes in trade fair participation rules, regional cluster initiatives, or sudden entry or exit of prominent referents, and then estimating the downstream effects on imitation, escalation, and survival. This extends the ‘who SMEs learn from’ promise in the Introduction and opens more multi-level theorizing.

Overall, this review advances SME internationalization research by showing that vicarious learning is best understood as a multi-channel knowledge pathway linking observed external cues to internationalization decisions and outcomes, and that its effects depend systematically on interpretive capacity, absorptive capacity, relational embeddedness, and how signals are translated into commitments (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ali, Salam, Bhatti, Arain and Burhan2020; Baum et al., Reference Baum, Sui and Malhotra2025; Spadafora et al., Reference Spadafora, Giachetti, Kumodzie-Dussey and Elango2023; Zahra & George, Reference Zahra and George2002). By organizing fragmented constructs into mechanisms and boundary conditions, the review provides a clearer foundation for cumulative theory building and more precise empirical testing.

Conclusion

This systematic review synthesized 27 peer-reviewed studies published between 2007 and 2025 to explain how vicarious learning shapes SME internationalization and the boundary conditions under which it enables or constrains outcomes. The evidence indicates that vicarious learning is not a single capability but a multi-channel process operating through peer performance benchmarking, imitation of strategic choices, legitimacy-driven mimetic pressures, and network- and advisor-enabled learning. Across these channels, vicarious learning can reduce uncertainty and support internationalization decisions, yet it can also heighten risk when firms misread external cues, imitate without fit, or escalate commitments beyond their capabilities. By clarifying how the construct is conceptualized and operationalized across fragmented streams, and by integrating mechanisms with recurring contingencies (experience, interpretive capacity, absorptive capacity, and network position), the review strengthens the basis for cumulative theorizing and more comparable empirical testing in SME internationalization research. Future research would benefit from construct harmonization across learning channels, deeper microfoundations of interpretation and referent selection, and longitudinal designs that capture how learning modes interact and evolve across internationalization phases.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2026.10087

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Declaration

An AI-based tool (ChatGPT) was used only to assist with preliminary keyword generation and the drafting of database search strings for the literature search. No AI tools were used for study screening, quality appraisal, data extraction, synthesis, or interpretation of findings.