Introduction

Today, most authoritarian regimes have established elected legislatures and endowed them with lawmaking power, or the ability to approve or reject legislation. These institutions are theorized to play an important role in inducing conformity and cooperation among members of the political elite (Gandhi and Przeworski Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2006; Stacher Reference Stacher2012). But it is less clear how the process of cooptation plays out within these institutions. Policymaking is an important political process, and delegating this authority to legislators establishes a potentially costly constraint on the ruling coalition. A key puzzle thus remains: once the regime has established a legislature and granted it lawmaking power, how does it ensure that those elected cooperate with its policy agenda?

In this paper, we propose a theory of legislative cooptation, which we define as the intentional exchange of economic rents and policy concessions for within-legislature cooperation with the regime’s policy agenda – in short, voting with the regime on proposed legislation. Though the phenomenon of legislative vote-buying has been studied in democratic settings, a number of empirical challenges have hindered its exploration in autocratic contexts. These include data limitations (measures of legislative behaviour are often absent or available only in rare cases),Footnote 1 the inherent difficulty in benchmarking regime preferences and measuring cooperation, and the private nature of elite exchange. And yet, this same lack of transparency makes autocratic legislatures especially plausible settings for this type of preferential exchange to take place.

We test our theoretical propositions using a novel dataset of legislator behaviour in the Kuwait National Assembly (KNA). We overcome the problem of data scarcity by collecting systematic data on roll call votes on all successful legislation in Kuwaiti history, totalling more than 150,000 individual votes across over 3,000 laws passed from 1963 to 2016. Our data cover sixteen legislative terms and represent one of the first and most comprehensive datasets of this kind from within an authoritarian regime.Footnote 2 Like a majority of autocracies today, the ruling family of Kuwait rules jointly with a legislature with lawmaking power, or the ability to approve or reject laws. According to the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, in 2020, legislative approval was required to pass laws in 66 per cent of all autocracies: on this metric, Kuwait falls near the median level of legislative influence among regimes (see Figure 1 below). Kuwait also offers useful leverage on the issue of identifying regime preferences: members of the ruling coalition (the Council of Ministers, or cabinet) serve as ex officio voting members of the legislature. We exploit this institutional feature to identify the regime’s preference for each policy under review and create a novel measure of policy cooperation: whether legislators vote with or against the Council of Ministers or the ruling coalition.

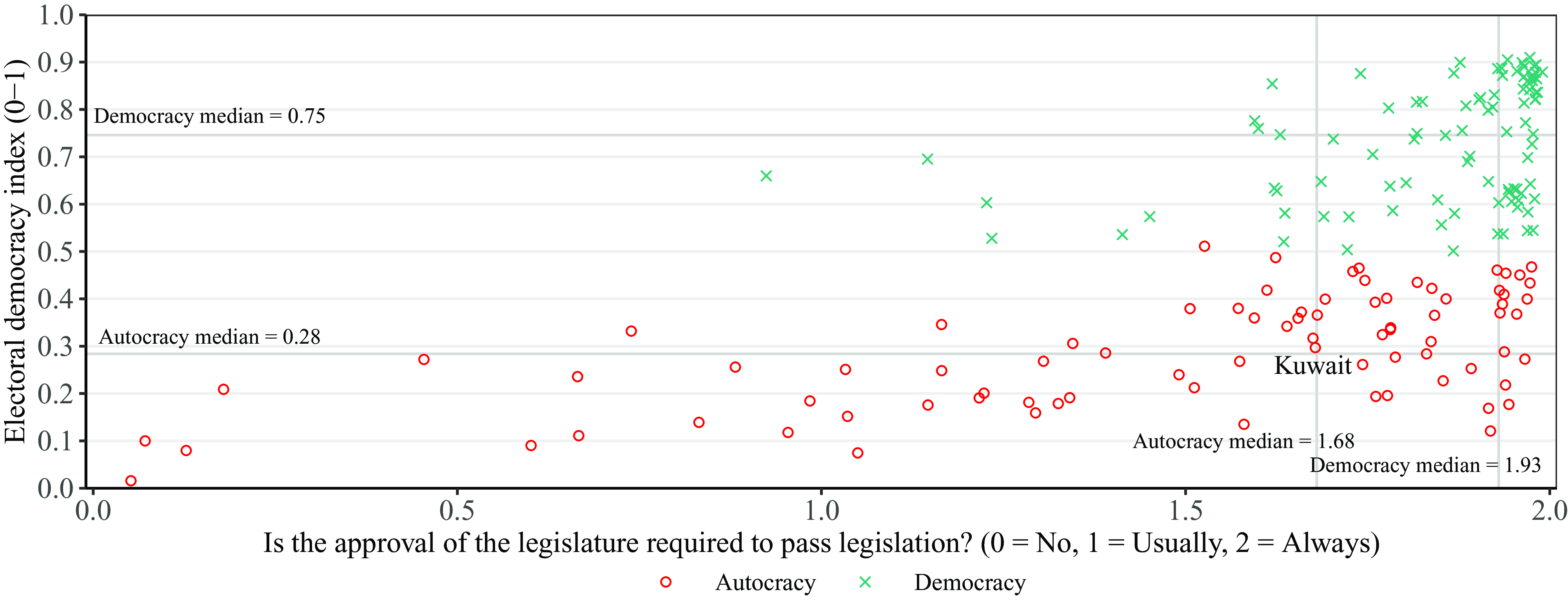

Figure 1. Democracy, autocracy, and legislative approval in contemporary regimes (2020).

Note: The figure plots countries according to the degree of legislative approval (x-axis) and the degree of electoral democracy (y-axis). Points represent countries in 2020. Source: Varieties of Democracy Project.

We take advantage of the Kuwaiti regime’s dependence on oil and the ruling family’s discretionary power over ministerial appointments to generate distinct measures of rents and policy concessions, respectively. We use exogenous fluctuations in oil prices (as well as government revenues) to assess whether or not economic rents predict policy cooperation with the ruling coalition on individual legislation within fifteen distinct legislative terms starting from 1963. For policy concessions, we gather data on within-term variation in the appointment of representatives of ideological groups to the Council of Ministers and examine the effect on cooperation among group members within the legislature.

Our results document the extent and predictors of opposition to the Council of Ministers’ legislative agenda in the KNA. Substantively, we find that elected legislators vote against the Council of Ministers in 10 per cent of all votes, leading, on occasion, to the KNA passing legislation against the ruling coalition’s wishes. But, much more often, the Council of Ministers secures a supermajority of support.

We attribute this to the regime’s ability to use economic rents and policy concessions to elicit policy cooperation: we find evidence that both rents and policy concessions are effective in facilitating legislative cooptation. A standard deviation increase in oil revenues is associated with a 2 percentage point increase in policy cooperation. A single ministerial appointment has a similarly positive effect among legislators affiliated with the respective ideological group. This latter result is of particular interest, as it represents intriguing evidence that policy concessions are, in fact, offered to elites outside the ruling coalition. Both qualitative evidence, as well as additional empirical analyses, confirm that ministerial portfolios are important opportunities for ideological groups to influence policy. And we find fascinating signs that the regime uses ministerial appointments strategically, with the effect that institutions become more representative of electoral outcomes: there is no legal requirement that the Council of Ministers reflect legislative composition, yet the regime appoints ideological representatives at rates that reflect their prevalence in the legislature.

This research serves as an innovative and systematic test of cooptation on policy voting within an authoritarian legislature and adds to a growing body of work investigating behaviour within these institutions (Gandhi et al. Reference Gandhi, Noble and Svolik2020). Though previous scholarship often describes authoritarian legislatures as ‘rubber stamp’ bodies that serve the personal whims of incumbents (Brancati Reference Brancati2014), researchers are increasingly recognizing the importance of these institutions in responding to citizen needs (Truex Reference Truex2016; Distelhorst and Hou Reference Distelhorst and Hou2017), resolving factional disputes within the regime itself (Lü et al. Reference Lü, Liu and Li2020; Noble Reference Noble2020), and moderating protest and dissent (Reuter and Robertson Reference Reuter and Robertson2015). Yet the particular dynamic we study here – substantive cooperation with the ruling coalition’s policy agenda – is novel both for the comprehensiveness of the data used, covering the entirety of Kuwaiti legislative history and the unique level of insight into the micrologic of legislative cooptation. This offers a new and highly precise look into the internal workings of legislatures in authoritarian contexts. It also allows us to incorporate both legislators aligned with the regime and the ideological opposition within the same theoretical framework – and to document the dispensation of policy concessions to the latter.

We also provide evidence of a possible mechanism linking oil wealth and the durability of autocratic regimes (Ross Reference Ross2012). Other studies have argued that resource wealth allows regimes to provide patronage and public goods without the citizen demands for accountability incurred by taxation (Crystal Reference Crystal1995; Ross Reference Ross2001). Here, we suggest rents facilitate the cooperation not only of the public but also of those elected to represent their interests – the political elite. The finding that legislative support varies with the amount of oil revenues also reveals the limitations of a rentier state based on such a volatile commodity.

The core scope condition required for our argument to apply is that the legislature be endowed with lawmaking power, a threshold met by a majority of autocratic regimes today. However, we expect significant variation in patterns of legislative cooptation on the basis of other institutional and regime attributes. These include the composition of the legislature and degree of outsider representation, the ability of the regime to deploy ‘sticks’ rather than carrots to elicit compliance, and the nature of rents and policy concessions available to the regime. For example, though oil’s value and fungibility make it especially useful to a regime, states without such reserves can draw on an array of other sources for rents, including other natural resources or preferential business arrangements (Szakonyi Reference Szakonyi2018). A regime without any such resources may rely more heavily on policy concessions, while one with more coercive influence over legislative participants may turn to negative incentives for compliance (Desposato Reference Desposato2001). And dominant party regimes may rely on the party apparatus to ensure compliance (albeit through comparable behavioural incentives), while monarchies with fragmented legislatures (Lust-Okar and Jamal Reference Lust-Okar and Jamal2002) may require broader and more direct legislative cooptation. Further research might help to clarify the circumstances under which legislative cooptation is more prevalent or operates via one mechanism or another. Yet the basic premise – that elected legislators extract benefits from the regime in exchange for their policy cooperation – is, we argue, consistent with the theorized role of cooptative legislative institutions in general, and thus one we expect to travel to a diverse range of authoritarian contexts in which the legislature is endowed with an authority that the autocrat values.

Cooptation Theory and Legislative Institutions

In response to the growing number of hybrid regimes globally, scholars have generated several explanations for why autocrats establish legislative institutions. These include arguments that such institutions allow autocrats to share power among members of the ruling coalition (Boix and Svolik Reference Boix and Svolik2013), ‘rubber stamp’ initiatives that provide domestic and international legitimacy, and coopt members of the potential opposition. Most prominent among these arguments is the last: cooptation theory. Broadly, cooptation is a process through which incumbent autocrats induce conformity toward the consensus of a ruling coalition’s executive elites (Stacher Reference Stacher2012, 112). In the remainder of this section, we review the literature on cooptation theory, address a key shortcoming of existing studies, and present a set of hypotheses subsequent sections will evaluate.

Legislative institutions in autocracies allow autocrats to share power and credibly commit to rule jointly with rival elites (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2008; Boix and Svolik Reference Boix and Svolik2013; Meng Reference Meng2019). But once incumbent autocrats establish these institutions, another challenge emerges: how do autocrats ensure elected legislators cooperate with the ruling coalition and support its policy agenda? In a seminal study, Gandhi and Przeworski (Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2006) propose two distinct mechanisms through which rulers induce cooperation: rents (direct payments to rival elites) and policy concessions. Though they offer clear theoretical predictions, Gandhi and Przeworski lack a strong empirical test of their argument. In particular, they treat the mere existence of political parties in legislatures as evidence of cooptation.Footnote 3 We expect that the regime seeks to control legislators outside the ruling coalition. But we know less about why these particular legislators cooperate once they are elected and acquire the authority of their office. This is not a trivial issue; by delegating lawmaking power, the regime allocates an authority of consequence to legislators. It must thus take steps to ensure that this power is not deployed in opposition to its interests.

We propose a more fine-grained approach to understanding cooptation that allows us to address how and why this process takes place within legislative institutions. We acknowledge that the representation of political parties outside the ruling coalition in the legislature is suggestive evidence of cooptation. But it is within these institutions where our more narrowly defined process of legislative cooptation takes place. That is to say, first, a regime establishes legislative institutions and holds elections. Then, members of the ruling coalition engage in legislative cooptation with these elected legislators by offering benefits in exchange for their cooperation in the policymaking process.

The logic of legislative cooptation

Electoral malfeasance is a common feature of contemporary autocracies. Efforts to undermine elections include restrictions on candidacy, gerrymandering, the manipulation of district boundaries, and vote buying, among others. These measures ensure that elected legislators are as friendly as possible to the ruling coalition. But once elections have been held at the beginning of a legislative term, the set of players in the legislative bargaining game is established and granted policymaking authority. At this point, the ruling coalition must find a way to induce cooperation among individual participants in the legislature.

We argue that the ruling coalition solves this problem using legislative cooptation, which we define as the intentional exchange of economic rents or policy concessions to legislators in exchange for compliance with the regime’s policy agenda.Footnote 4 Though the logic and dynamics of cooptation can be extended to a range of settings in autocracies,Footnote 5 it is within the legislature that policy – including important decisions about redistribution, electoral laws, and the penal code, among other issues – is determined. Hence we expect the core objective of legislative cooptation is to ensure individual legislator support for the regime’s policy proposals.

The regime has both carrots and sticks at its disposal to induce conformity with its policy agenda vis-a-vis the legislature. Among the latter, we would include executive authorities such as the ability to dissolve a legislature or declare a state of emergency as well as vetoes and executive orders that may supersede laws passed.Footnote 6 But, in practice, these ‘sticks’ are costly and risky to employ. If overly public or repressive, they may threaten the regime both domestically and internationally. The use of sticks may also disincentivize participation in legislative institutions, thereby undermining their role in the broader process of cooptation. Hence it may often be preferable for the regime to use preferential benefits to ensure legislators cooperate with the ruling coalition.

We propose that the regime distributes both rents and policy concessions in exchange for legislative votes, conditional on its own preferences and those of elected legislators. Some legislators may be interested merely in the personal perks associated with proximity to the ruling coalition. Others participate because they value opportunities to extract policy concessions from the ruling coalition.Footnote 7 We are not the first to point out that rents are distributed to legislators; as others argue, candidates in autocratic elections compete for access to a variety of perks exclusive to elected positions, including business opportunities and personal payments (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2011; Reuter and Robertson Reference Reuter and Robertson2015). These may be allocated individually or at the group level. Likewise, policy concessions have been theorized as a key objective of opposition actors (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008). Yet this project is innovative in arguing that these incentives are traded explicitly for a cornerstone aspect of governance: legislative votes.

We note here that the phenomenon we investigate – how rulers induce conformity in legislative voting – is in some ways analogous to the process of building legislative coalitions in democratic contexts, something that has been explored far more extensively. Among these studies, scholars have explored the processes by which elected presidents build support in legislatures that their party does not dominate (Chaisty et al. Reference Chaisty, Cheeseman and Power2018), the means by which party leaders elicit policy support through distributive allocations (Evans Reference Evans2004), and the significance of lobbying and vote-buying in determining legislative outcomes (Wiseman Reference Wiseman2004). There are, of course, key differences between the institutional circumstances in autocratic and democratic legislatures. Most notable is the increased degree of executive autonomy (from both legislative and electoral oversight) and authority. For example, whereas in parliamentary democracies, the legislature typically has a direct role in the selection and survival of the government that forms;Footnote 8 in the case we study, and most other autocracies, the head of state has considerable discretion over the formation of the government and the nature of ministerial appointments. Still, the mechanisms of legislative cooptation we explore here have clear analogues in democratic institutions.

In the real world of authoritarian policymaking, it is difficult to assess the centrality of economic rents and policy concessions to legislative voting for several reasons. First, data from these legislatures are rarely made public and often difficult to obtain. Few autocracies publish data on the activities of individual legislators and their behaviour in office. Even where data on legislator activities are available, there is a second challenge to the empirical assessment of cooptation: uncertainty about the underlying preferences of legislators and the absence of visibility into offers (economic rents or policy concessions) from the ruling coalition. Due to the sensitive nature of these exchanges, both autocrats and legislators have incentives to conceal their preferences and the nature of their interactions from the public. Legislators and autocrats do not publicly disclose when rents or concessions have been exchanged for cooperation. In practice, we may only observe whether a legislator supports the ruling coalition’s agenda (cooptation success) or opposes it (cooptation failure).

Though we cannot observe legislators’ private preferences or the processes that precede their public behaviours, we instead propose that changes in the ruling coalition’s use of economic rents and policy concessions provide an opportunity to empirically assess the efficacy of legislative cooptation. To do so, we focus on the use and effect of these mechanisms on legislator cooperation with the ruling coalition within a legislature. Our first two hypotheses spell out the purported efficacy of these two mechanisms. First, we consider the effect of economic rents on cooperation with the autocrat’s policy agenda. We expect that as the regime’s access to rents increases, its assessment of the marginal value of expenditures declines and it will increase its rent distribution. Our hypothesis thus focuses on the availability of cash to the regime, rather than the actual distribution or provision of economic rents to individual legislators:

H1: More rents available to the regime will be associated with greater cooperation with the autocrat and [the] ruling coalition’s policy agenda.

Second, we consider the effect of policy concessions on cooperation. Similar to H1, we expect that, for legislators representing ideological movements, the incorporation of their political and ideological interests into the regime’s policy agenda will elicit greater cooperation:

H2: Evidence of policy concessions granted to legislators will be associated with greater cooperation with the autocrat and ruling coalition’s policy agenda.

These two hypotheses link mechanisms of legislative cooptation to legislator behaviour. We further argue that legislator ‘type’ influences the marginal effectiveness of these strategies. That is, these two mechanisms will be differentially effective in inducing cooperation among legislators that differentially value economic rents and policy concessions. For rent-seeking legislators, we expect that policy concessions are of little interest. Correspondingly, we expect that for policy-seeking legislators, rents are of lower marginal utility. We thus expect policy-seeking legislators to exhibit greater levels of cooperation when the ruling coalition makes greater use of policy concessions vis-a-vis economic rents (and vice versa).

H3: When more (fewer) rents are available, less (more) ideological politicians will be most likely to be co-opted.

Context

We test these hypotheses in the context of Kuwait but we expect them to apply more broadly to settings where at least some degree of legislative approval is required to pass laws. Though there is considerable cross-national variation in the institutional strength and autonomy of legislatures across political regimes, lawmaking power is a persistent feature of contemporary authoritarian legislatures. According to data from the Varieties of Democracy Project, in 2020, eighty-seven regimes were classified as authoritarian (including both ‘electoral’ and ‘closed’ autocracies). Among these cases, 5 (6 per cent) do not require legislative approval to pass laws, 23 (26 per cent) usually require legislative approval, and 55 (63 per cent) always require legislative approval. Figure 1 categorizes all regimes in the V-Dem data and plots them by whether legislative approval is required to pass legislation (x-axis) and V-Dem’s electoral democracy index (y-axis). In Kuwait, legislative approval is required to pass laws; it falls near the median for autocracies on both axes (electoral democracy index = 0.32; legislative approval = 1.68).

Background: Kuwait national assembly

Scholars of the Middle East view the Kuwait National Assembly (KNA) as the strongest legislative institution among the autocratic Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, if not the entire Arab World (Zaccara Reference Zaccara2013; Shalaby Reference Shalaby2015; Freer Reference Freer2018). The 1962 Constitution establishes a political system described as ‘a hereditary Emirate held in succession in the descendants of Mubarak Al-Sabah’ (Article 4) with a ‘separation and cooperation of powers’ between the executive and legislative branches (Article 50). Executive power is vested in the Emir, who appoints the prime minister and Council of Ministers (cabinet). Legislative power is vested in both the Emir and the National Assembly (Article 51). Kuwait resembles other hybrid regimes with elected legislatures and unelected, or hereditary, executives, with one key exception. After the investiture of a new Emir, the National Assembly must, by majority vote, approve his choice of Crown Prince.

The KNA is a unicameral body with fifty members elected by secret ballot every four years across five electoral districts. In addition to the fifty legislators, ministers (members of the Council of Ministers) serve as ex officio voting members of the legislature. Ministers may include members of the ruling Al-Sabah family, elected members of the KNA, and others outside government. The total number of ministers may not exceed one-third the number of elected members of the KNA, or sixteen.Footnote 9 After appointing a prime minister, the Emir retains discretionary power to appoint ministers and relieve them of their posts. At any time, the Emir can dissolve the Assembly, provided new elections are held within 60 days. Since the restoration of the Assembly in 1992, only two assemblies have run out their full four-year terms. In the past two decades, there have been eleven elections. Yet, as noted above, the KNA has lawmaking authority, or the ability to approve or reject legislation. The legislature is also constitutionally empowered to investigate and oversee the activities of the executive branch, which provides the legislature with a set of institutional mechanisms that can be used to constrain the regime’s policy options. These legislative functions indicate that the legislature possesses a degree of authority that similar countries among the Arab Gulf States – and other authoritarian regimes more broadly – do not have. However, the legislature still has far fewer options to constrain the executive than legislatures in democratic settings; for example, the legislature cannot select or influence the selection of ministers.

Political cleavages in Kuwait

Kuwait is a communally diverse autocracy, and electoral competition occurs between discrete groups. Communal attachments are defined by sect (Sunni and Shia) and origin, including both familial and tribal linkages dating back to the establishment of modern Kuwait (Ghabra Reference Ghabra1997; Al-Nakib Reference Al-Nakib2016). These groupings organize social and electoral life in Kuwait. But ideological forces are also critical political cleavages. National-liberal and Islamist political associations proliferated in Kuwait even before independence. In many ways, the strength and resilience of the KNA is itself a product of the diversity of civic and associational life. As a result, Kuwait boasts ‘the most vociferous and powerful system of political participation among the six Gulf States’ (Baaklini et al. Reference Baaklini, Denoeux and Springborg1999, 216). Institutionalized political parties do not exist, yet these ideological groups have developed into what Kraetzschmar (Reference Kraetzschmar, Cavatorta and Storm2018) describes as ‘proto-parties’ that participate in elections and win seats in the KNA.Footnote 10

In general, the KNA includes a diverse (though not necessarily representative) range of individuals (see Table A.2 in the Supplementary Materials for complete descriptive statistics on legislators and appointed ministers). Notably, members of the Al-Sabah family do not participate in competitive elections and are, therefore, represented in the cabinet but not among elected legislators. Both legislators and ministers are relatively well-educated, with a majority attaining undergraduate or post-graduate degrees. Tribal and ideological groups are well-represented in the KNA (and, to a lesser extent, the cabinet). Women, however, are nearly absent from both bodies.Footnote 11 Unsurprisingly, given Kuwaiti employment patterns, public sector careers are the most common. Yet both legislators and ministers represent a range of occupational backgrounds: around half of the elected legislators came to the KNA from the private sector, academia, or other careers, including medicine and the media. Collectively, these statistics confirm that the KNA is a relatively diverse institution incorporating ideologically oriented individuals as well as a range of other business and occupational sectors.

Kuwait is a hereditary emirate that bears a family resemblance to other constitutional monarchies. Previous scholars have found that monarchical regimes are uniquely resilient (Geddes et al. Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014), owing to a tendency of these rulers to use ‘divide and rule’ tactics that result in fewer concessions (Lust-Okar and Jamal Reference Lust-Okar and Jamal2002), manage succession crises more effectively (Herb Reference Herb1999), and create stable distributional arrangements and limits on executive authority (Menaldo Reference Menaldo2012). In the analysis that follows, we show that the Kuwait case complicates these empirical generalizations. Despite the presence of a powerful (but fragmented) opposition, the KNA exhibits significant cohesion, which is comparable to consensual voting patterns other scholars have uncovered in presidential regimes (Hummel Reference Hummel2020). In this respect, Kuwait exhibits both similarities and differences with other monarchical regimes. These features of the case, we argue, allow us to broaden our scope to regimes that do not rely exclusively on dominant parties to mitigate elite and distributive conflict.

Data and Approach

To test our hypotheses about strategies of cooptation and their effectiveness, we develop a dataset of historical roll call voting in the KNA.Footnote 12 Roll call votes have been used extensively in the US and other democratic contexts to estimate voters’ spatial preferences.Footnote 13 Rather than modelling legislative preferences along a latent ideological dimension, we are interested in the degree to which their behaviour conforms with regime preferences. We conceive of this behavioural outcome as resulting in part from a strategic interaction with the regime.Footnote 14

The Kuwait National Assembly Roll Call Votes (KNA-RCV) dataset includes individual roll call votes for successful legislation passed by the KNA from 1963 to 2016. To collect these data, we first downloaded digitized .pdf files of legislative transcripts from the KNA Archive.Footnote 15 A total of 3,595 laws were passed by the KNA from 1963 to 2016. With support from a team of research assistants, we then identified the roll call voting record for a given law in the transcripts and hand-coded each minister and elected legislator’s vote. Globally, the use of the recorded roll call vote in passing legislation is sometimes discretionary and thus subject to possible selection effects, such as more controversial legislation being more likely to appear in the data (Ainsley et al. Reference Ainsley, Carrubba, Crisp, Demirkaya, Gabel and Hadzic2020); this is not the case in Kuwait, where roll call votes are a requisite part of the process for passing legislation. Accordingly, we successfully identified records for 3,337 laws (93 per cent). Multiple laws are occasionally bundled and voted as one; our dataset thus includes 2,693 final votes. We describe the data collection process in greater detail in Section S.1 in the Supplementary Materials appendix.

We limit our focus to final roll call votes for both practical and substantive reasons. First, record-keeping in the KNA makes it logistically impossible to track a single piece of legislation through all stages of the legislative process: draft laws are not assigned unique identifiers, and, for laws that pass, only the date of the final vote is documented. Additionally, there are substantive reasons to focus on final votes (or ‘second deliberations’, described in greater detail in Section S.1) rather than including all procedural and amendment votes, for which legislator behaviour may be driven by a wider range of concerns. In Kuwait, it is rare for a final vote to fail; as in other legislative institutions, agenda-setting power (held by the Speaker of the Assembly) is paramount in initiating a final vote (Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005). In most cases, the speaker will avoid the public embarrassment associated with a failed vote by never bringing such a bill to the floor. Finally, we note that this empirical approach is consistent with that used in a large literature on policy preferences and legislative vote-buying in democratic contexts (Snyder and Groseclose Reference Snyder and Groseclose2000; Wiseman Reference Wiseman2004).

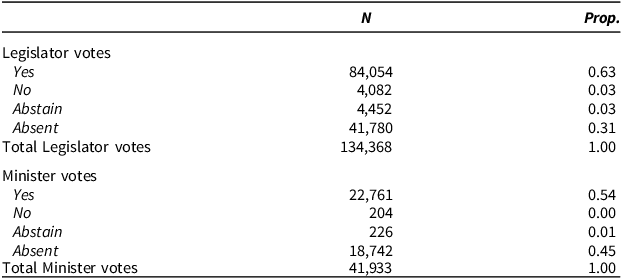

Table 1 displays basic descriptive statistics in voting patterns, summarizing the number of yes, no, and abstain votes by legislators and ministers. In total, the dataset includes 168,476 observations. At first glance, a few patterns are clear. First, absences are relatively common, and ministers are absent more often than elected legislators (45 per cent of the time compared to 31 per cent).Footnote 16 Amongst legislators, absences are distributed unevenly: legislators in the top 10 per cent of overall absenteeism account for 50 per cent of total legislator absences. We interpret legislator absences as evidence of shirking duty, more so than as a form of protest for two reasons. First, we find that low attendance rates are negatively correlated with other confrontational actions such as minister queries (Malesky and Schuler Reference Malesky and Schuler2010) and interpellations. Additionally, legislators with an ideological affiliation are less frequently absent than those without one, suggesting that members with stronger policy positions prefer to voice their opposition in person rather than by boycotting a vote. Minister attendance, by contrast, is likely at least in part a strategic action related to the competitiveness of a given vote. A closer vote margin among legislators is associated with a higher number of ministers present, suggesting the regime sends ministers to participate when it needs the additional votes to ensure legislation is successful.

Table 1. Kuwait National Assembly Roll Call Votes dataset, 1963-2016

Note: The table displays the number and proportion of yes, no, abstain, and absent votes among legislators and ministers. The total number of roll call votes in the dataset is 168,476. This number does not equal the sum of legislator and minister roll call votes separately, as elected legislators can serve as ministers as well. Source: KNA-RCV dataset.

Second, the legislature demonstrates a great deal of consensus: the vast majority of votes submitted are in favour of legislation. Noes and abstentions constitute only 10 per cent of votes cast by legislators.Footnote 17 Yet there is substantial variation in these quantities at both the term and legislator level.Footnote 18 And, as scholars have shown in other contexts, a high degree of conformity (whether to regime or party preferences) does not necessarily signify a lack of legislative influence (Russell and Cowley Reference Russell and Cowley2016); instead, it may reflect the fact that concessions are allocated in advance of legislative votes. In the next section, we examine voting patterns among ministers more closely and define our primary outcome variable.

Dependent variable: Voting with ministers

To test H

![]() $_1$

and H

$_1$

and H

![]() $_2$

, we first identify whether an elected legislator voted with or against the ruling coalition – in this case, the Council of Ministers – on each law passed. One might identify the regime’s position on a given policy in a number of different ways; by examining the origin of the legislation through media reporting, or through the votes of elected representatives close to the ruling coalition. Here, we take advantage of the distinctive institutional feature outlined above: the ability of ministers appointed by the Emir to vote alongside elected legislators. Because ministerial appointments are discretionary, the Emir may remove or replace a minister for any reason and does so with relative frequency. The average term saw five cabinet changes, typically involving the replacement of a single minister.

$_2$

, we first identify whether an elected legislator voted with or against the ruling coalition – in this case, the Council of Ministers – on each law passed. One might identify the regime’s position on a given policy in a number of different ways; by examining the origin of the legislation through media reporting, or through the votes of elected representatives close to the ruling coalition. Here, we take advantage of the distinctive institutional feature outlined above: the ability of ministers appointed by the Emir to vote alongside elected legislators. Because ministerial appointments are discretionary, the Emir may remove or replace a minister for any reason and does so with relative frequency. The average term saw five cabinet changes, typically involving the replacement of a single minister.

As a result, we expect ministers to vote as a bloc in accordance with the ruling coalition’s policy preferences, as the Emir could immediately remove and replace a minister who refused to support his preferred policies within the legislature. We use the KNA-RCV dataset to examine this anticipated voting cohesion across the entire history of successful legislation and find that it is very much the rule: across the 2,693 unique final votes in our dataset, there were only five instances (all in 1963) in which active ministers submitted a mix of yes and no votes on a single law. Since then, there has not been a single instance of vote-splitting among the Council of Ministers on these final votes.

This near-perfect voting cohesion corroborates our expectation that ministers are bound in practice to uphold the position of the Emir and ruling coalition on a given piece of legislation, or at least not openly oppose it.Footnote 19 We therefore use minister votes to benchmark regime preference on a policy, assuming that the regime supports the legislation if at least one minister votes in favour and none vote against, and opposes it if at least one minister votes against and none vote in favour.Footnote 20 Cooperation with the regime is a binary variable defined as 1 if an elected legislator votes yes on a policy ministers support or no on a policy they oppose, and 0 otherwise. Abstentions and absences can generate complications in roll call vote analysis given the ambiguity over whether they represent apathy or moderate opposition, or some form of within-party dissent (Rosas et al. Reference Rosas, Shomer and Haptonstahl2015). Here, because they are procedurally equivalent to ‘no’ votes following the rule change in April 2007, we code abstentions as ‘noes’ for deliberations that took place after this date. For interpretive clarity, we drop legislator abstentions prior to April 2007 for the analysis in the main text but we conduct a robustness check where we test whether our results are sensitive to this choice or other interpretations of abstentions (see Table A7 in the Supplementary Materials). Likewise, we drop legislator absences (scenarios where they are not present for a second deliberation vote) in most analyses. In Table A.8, we conduct a robustness check to validate whether our results are sensitive to this choice. Our core results are robust to both the abstention and absence robustness checks.

Independent variable: Oil Rents

In H

![]() $_1$

, we predict that more economic rents available to the regime will be associated with increased cooperation with the regime’s policy agenda. We seek to test this on a within-law basis, using oil prices and revenues at the time of the vote as a proxy for regime funds. Rent distribution may take a variety of forms, including both under-the-table direct payments to active legislators as well as institutionalized transfers incorporated into legislation. There is ample reason to expect that both occur in the Kuwaiti context. Though comprehensive evidence of illicit, direct transfers are not available, qualitative evidence suggests they occur. For example, in 2011, the revelation that millions of dollars had been transferred into the bank accounts of two elected legislators (and the subsequent investigation into the finances of an additional seven legislators) led to broad public outrage and contributed to the dissolution of the 2009 assembly.Footnote

21

Other institutionalized forms of rent distribution can be embedded in budget proposals; legislators coopted in this manner may be incentivized to support legislation because of personal benefits or benefits allocated to their constituents.

$_1$

, we predict that more economic rents available to the regime will be associated with increased cooperation with the regime’s policy agenda. We seek to test this on a within-law basis, using oil prices and revenues at the time of the vote as a proxy for regime funds. Rent distribution may take a variety of forms, including both under-the-table direct payments to active legislators as well as institutionalized transfers incorporated into legislation. There is ample reason to expect that both occur in the Kuwaiti context. Though comprehensive evidence of illicit, direct transfers are not available, qualitative evidence suggests they occur. For example, in 2011, the revelation that millions of dollars had been transferred into the bank accounts of two elected legislators (and the subsequent investigation into the finances of an additional seven legislators) led to broad public outrage and contributed to the dissolution of the 2009 assembly.Footnote

21

Other institutionalized forms of rent distribution can be embedded in budget proposals; legislators coopted in this manner may be incentivized to support legislation because of personal benefits or benefits allocated to their constituents.

Regardless of how rents are distributed within the legislature, we expect that their usage will increase with regime revenues. And oil rents plausibly serve as a measure of these revenues. Kuwait has the fourth largest oil reserves in the world and derives the majority of its wealth from this resource. There is a long history of oil revenues financing the ruling family’s activities, beginning with remittances received from the Kuwait Oil Company in 1935 (Crystal Reference Crystal1992, 18) and continuing more directly when that company was nationalized in 1976. The state remains heavily dependent on oil: between 1993 and 2015, oil rents comprised, on average, 91 per cent of total government revenues.Footnote 22

Oil has made Kuwait a wealthy nation, but other challenges have accompanied the accumulation of this wealth (Ross Reference Ross2012). Oil is one of the most volatile commodities in existence (see Figure 2, left panel). Kuwait has some influence over oil prices due to its high total output (roughly 6 per cent of global production) and membership in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which has sought to control prices through production scaling with mixed results. But to a large degree, government revenues are dependent on and thus vulnerable to global demand for this critical commodity. As a result, Kuwaiti government revenues – tied directly to prices following the nationalization of the oil industry – go through abrupt, largely exogenous boom and bust periods. Between 2014 and 2015, for example, Kuwaiti oil revenues fell by nearly half – from 26.5 billion to 13.6 billion dinars – and, correspondingly, government revenues dropped from 29 billion to 15.1 billion dinars.Footnote 23 In theory, the government could mitigate the high risk of its oil-based portfolio by managing expenditures and banking the surplus. In practice, Kuwait has constructed a welfare state with a large amount of social spending and subsidies, spending an average of 84 per cent of oil revenues in a given year (and running a budget deficit in 2015, following the drop in oil prices).

Figure 2. Oil prices and Kuwaiti oil rents over time.

Note: Left panel plots changing oil prices from 1963–2016, estimated using monthly spot crude oil prices for West Texas Intermediate and shown in constant 2016 USD. The right panel plots the annual Kuwait GDP (solid line) and oil rents (dotted line) from 1970–2016, estimated using data from the World Bank and shown in constant 2016 USD.

We therefore use oil as our primary measure of available rents – essentially as a proxy for the marginal value of cash to the regime. We measure this in two ways: first, through monthly crude oil prices in constant dollars (WTI Price),Footnote 24 and, second, by calculating oil revenues on a monthly basis using the price of oil and Kuwait’s estimated daily production (Oil Revenues).Footnote 25 The former metric has the advantage of a wider data range covering the entirety of KNA history and a greater claim to exogeneity. The latter is somewhat endogenous to government decision-making (the regime might, for example, increase production to help offset losses from falling oil prices or when it faces more parliamentary opposition) but more directly captures the rents available to the regime in a given period. We lag each measure by one month to account for time delays between oil sales and government access to (and ability to disburse) the resulting funds. We standardize these continuous variables in the regression models that follow for ease of interpretation of the resulting coefficients.

Independent variable: Cabinet positions

We next operationalize policy concessions granted to elected legislators. Again, this poses measurement challenges: identifying specific modifications to proposed laws and the legislators that would benefit from them is extremely challenging in this context. Even if we could track the individual concessions included in each law, we have no way of establishing a basis for comparison to the regime’s ideal policy. We instead use an indicator of policy influence in parliamentary settings: the appointment of ideological faction members to cabinet positions.

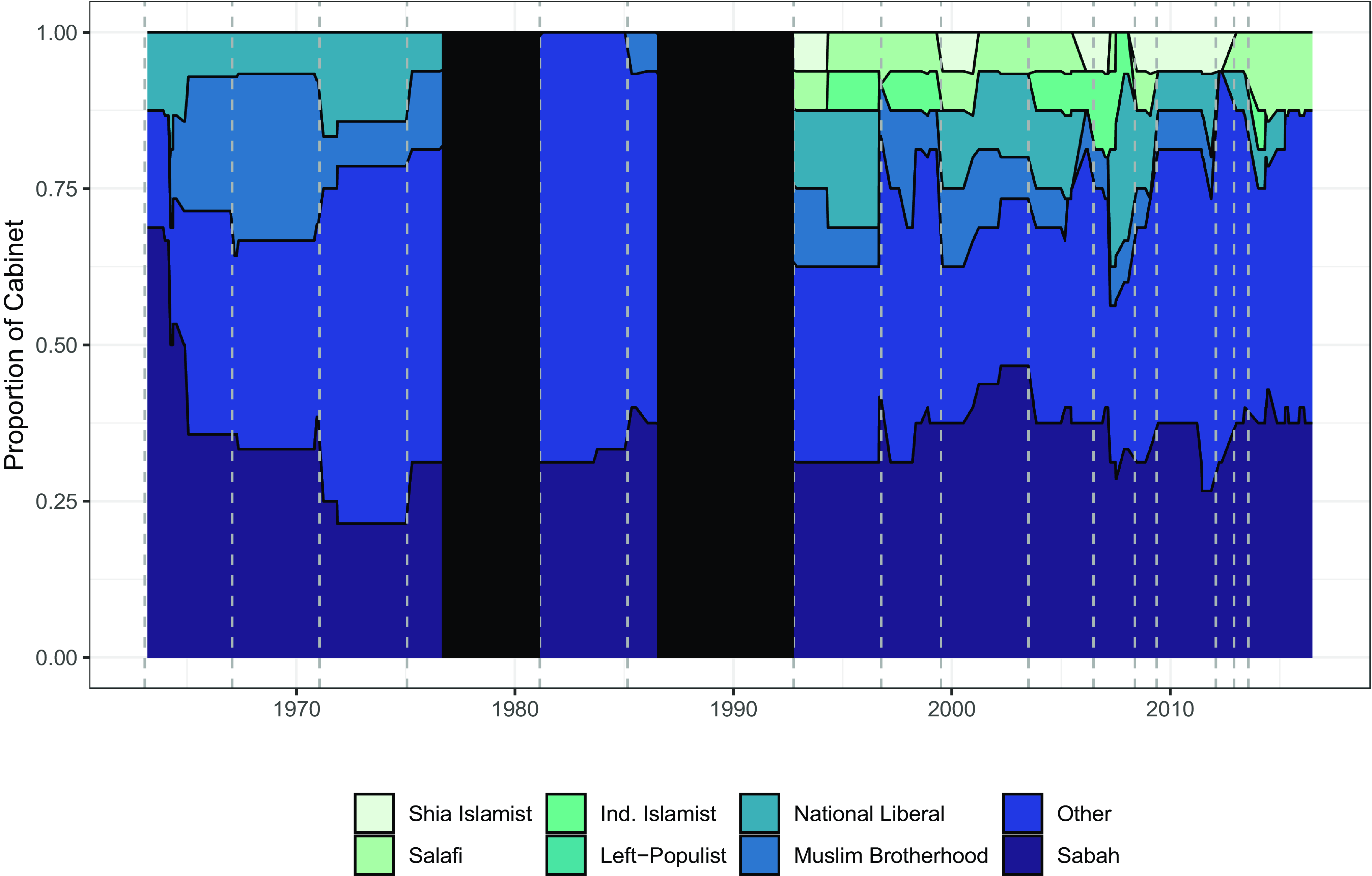

As in other parliamentary systems, most laws in Kuwait originate within and are initiated by the cabinet. Ministers design and shape draft legislation, giving them the opportunity to influence policy before it hits the legislative floor – a distinct bargaining advantage (Baron and Ferejohn Reference Baron and Ferejohn1989). For legislators representing ideological groups, having a copartisan in the Council of Ministers means that key laws such as the annual budget are more likely to preemptively incorporate their political and ideological interests; without such an advantage, their only recourse is to lobby individually for amendments in committees or on the legislative floor. The Emir has historically distributed cabinet appointments across a range of ideological groups. Figure 3 depicts cabinet composition over time with respect to the six proto-parties as well as the participation of the Al-Sabah family.Footnote

26

Consistent with H

![]() $_2$

, we predict that when the ruling coalition provides an ideological group with representation in the cabinet, elected legislators belonging to that group will be more likely to vote with the Council of Ministers – effectively because they have already had an opportunity to extract policy concessions on a given piece of legislation. Simply put, the draft policy that emerges from a cabinet with ideological group representation represents the result of preemptive deliberative bargaining between that ideological group and the regime.

$_2$

, we predict that when the ruling coalition provides an ideological group with representation in the cabinet, elected legislators belonging to that group will be more likely to vote with the Council of Ministers – effectively because they have already had an opportunity to extract policy concessions on a given piece of legislation. Simply put, the draft policy that emerges from a cabinet with ideological group representation represents the result of preemptive deliberative bargaining between that ideological group and the regime.

Figure 3. Cabinet composition over time.

Note: The figure depicts the historical proportion of cabinet members representing different groups, including the ruling Al-Sabah family as well as six ideological proto-parties. Dotted lines indicate the start of a new term (when a cabinet is formed), and the dark grey space represents the time when the legislature was dissolved for an extended period.

To capture affiliations and policy influence, we code whether a given elected legislator has one or more ideological affiliates on the Council of Ministers. As with oil price, we lag this measure by one month to allow time for new cabinet members to negotiate policy deals and for this government-drafted policy to pass to the final deliberation stage.Footnote 27 We create Cabinet Affiliate, a discrete variable measuring the number of ministers affiliated with a deputy’s ideological group in the month preceding each vote. We also code a binary indicator for whether or not the legislator in question is a member of an ideological bloc (that is, whether or not s/he is eligible for this treatment). Among all votes of active legislators in our dataset, 20 per cent were registered while the legislator in question had an ideological representative in the Council of Ministers. A total of 42 per cent of votes were cast by elected legislators with an ideological affiliation.

Approach

We first seek to understand the extent to which observable measures of legislative cooptation (oil rents and ministerial appointments) are linked to the actual voting behaviour of elected legislators (H

![]() $_1$

and H

$_1$

and H

![]() $_2$

). We therefore model voting with the regime as a function of these independent variables (WTI Price/Oil Revenues and Cabinet Affiliate).

$_2$

). We therefore model voting with the regime as a function of these independent variables (WTI Price/Oil Revenues and Cabinet Affiliate).

There are, of course, a number of potential confounders in establishing a linkage between economic rents, policy concessions, and legislator behaviour. Specifically, the ruling coalition’s use of these two mechanisms is likely the result of a strategic interaction between the regime and elected legislators. To account for temporal, political, and compositional attributes of each legislature, we include term fixed effects in all models. We therefore estimate the effect of within-term variation in oil price and cabinet composition. Additionally, we expect the regime to respond to the specific legislators elected – ideological or not – and their interest in different types of concessions. We thus estimate models with controls for legislator characteristics (including age, gender, education, occupation, sect, and tribal affiliation), or with legislator fixed effects.

We also expect legislator behaviour to vary with the legislation under consideration. Though this may involve multiple attributes of a given law proposal, we control for two aspects. The first is the action being taken: whether the proposed legislation represents a new law, an amendment to existing legislation, or the repeal of existing legislation. The second is the type of law, using a coding scheme adopted by the KNA itself. The law types classified by the KNA include budget laws, final accounts (reconciling an existing budget), treaties and conventions, and general laws (all other legislation). Different categories of laws elicit differing levels of cooperation; treaties and final accounts rarely provoke much opposition, while budget and general laws have lower levels of cooperation on average (Figure A.4 in the Supplementary Materials). We therefore include binary indicators for each law type as well as the law action (referred to collectively as Law controls) in the specifications to follow.

Finally, because oil prices and rents in Kuwait are linked closely to the state of the overall economy (Figure 2), this approach risks bundling the effect of general economic satisfaction with the effect of resource distribution because both occur in times of positive economic growth. Citizens are often more satisfied with the government when the economy is doing well, and, correspondingly, may be more cooperative – and the same principle may hold at the elite level. In other words, better economic performance may reduce opposition to the regime for reasons other than the cooptation mechanism hypothesized above. To address this possibility, we include a control for inflation in all models, using data from the World Bank.Footnote 28 Inflation is among the most visible and salient economic metrics for citizens and has been shown to be closely associated with their sense of economic well-being (Di Tella et al. Reference Di Tella, MacCulloch and Oswald2001). By controlling for this alternative metric, we seek to strengthen the degree to which the measures of oil wealth in our model address rent availability to the regime rather than economic health in the eyes of the public.

Results

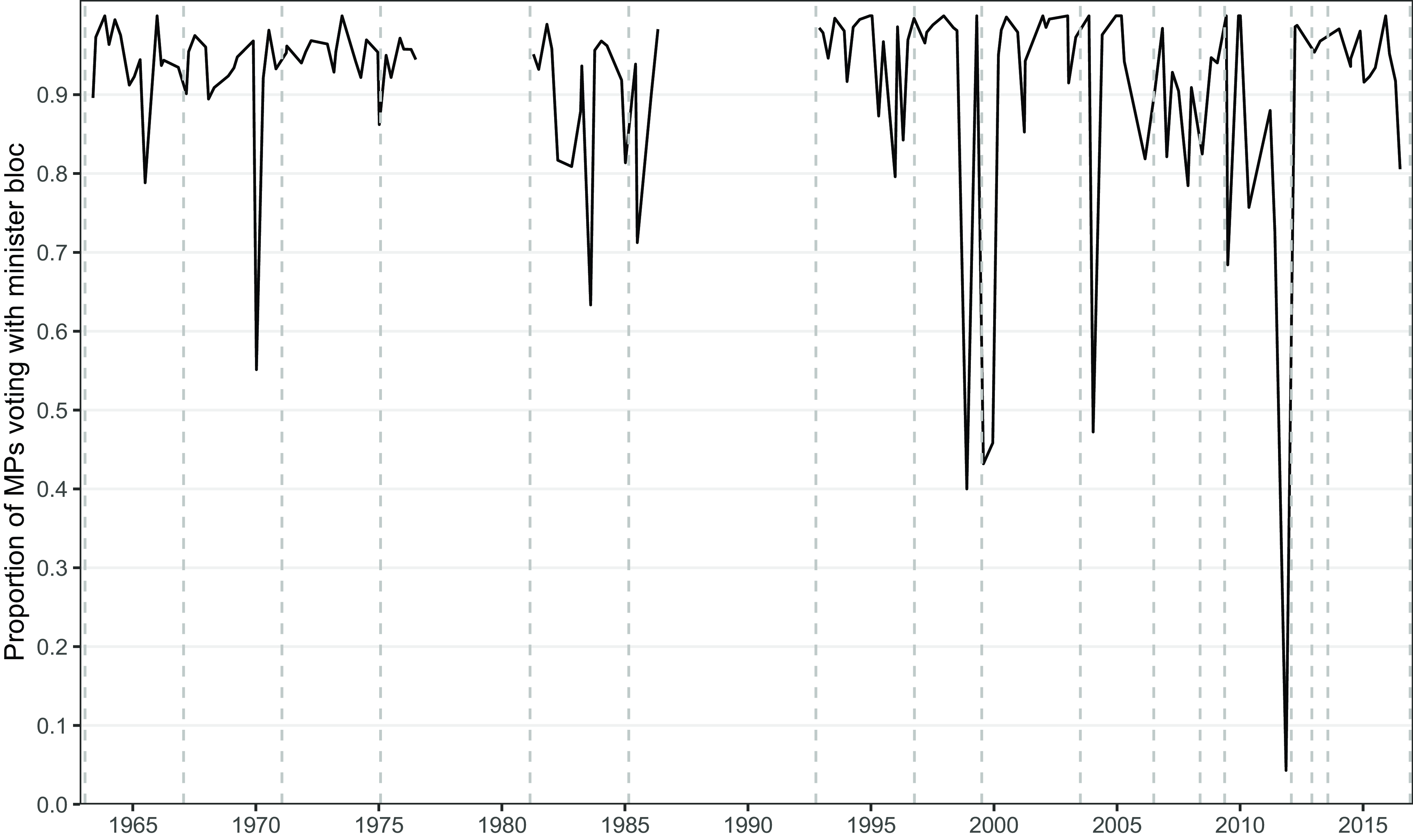

We begin by depicting general patterns of legislator cooperation in the KNA. Though legislators vote with the regime in the vast majority of cases (92 per cent of votes cast by legislators aligned with the minister bloc), this belies considerable variation on a per law and per legislator basis. Figure 4 plots our primary outcome variable over time, grouped into quarterly intervals. It is interesting to note that cooperation with the regime was often at its lowest level toward the end of a term. In some cases, a decline in cooperation directly preceded an early dissolution of the assembly by the Emir – evidence that, occasionally, the regime fails to effectively coopt elected legislators.

Figure 4. Cooperation in the Kuwait National Assembly, 1963-2016.

Note: The plot displays the average rate of elected legislators with the cabinet bloc in the KNA in quarterly intervals. The line indicates the average proportion of roll call votes in support of the minister’s consensus across laws passed in the interval. Dashed vertical lines signify elections. The legislature was suspended during two periods (1976–1981 and 1986–1992). Source: KNA-RCV dataset.

Most laws voted in the KNA pass by a wide margin: 30 per cent were enacted unanimously, and three-quarters achieved 90 per cent cooperation from elected legislators.Footnote 29 Yet there is evidence of substantial opposition in the remaining 25 per cent of votes. In many cases, a sizable bloc of legislators voted against the Council of Ministers: some laws were only successful because of the regime’s built-in advantage. And, over the history of the KNA, twenty-six laws were passed despite ministerial opposition – that is, the presumed regime preference was explicitly overruled in roughly 1 per cent of second deliberation votes.Footnote 30 These cases are distributed widely across terms, and most legislatures had at least one law passed despite ministerial opposition. The laws involved address a wide range of issues, including judicial affairs, pollution, and the proceedings of the KNA, though the modal topic is some form of welfare or social spending, broadly construed. In the majority of cases (88 per cent), the passage of the law was not closely followed by the dissolution of the legislature.Footnote 31 More detail on these 26 laws is reported in Table A.3.

Rents, policy concessions, and cooperation

We next turn to our proxies for cooptation and examine whether they predict legislator behaviour. Table 2 reports outputs from OLS models at the legislator-vote level on voting with the Council of Ministers.Footnote

32

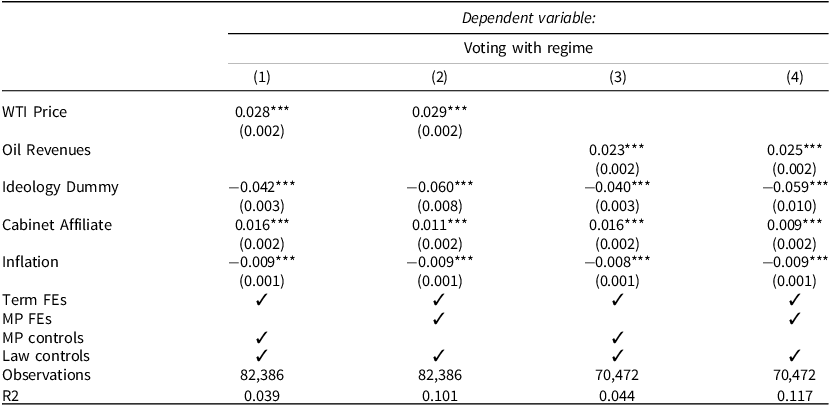

We first consider whether oil prices (models 1 and 2) and government revenues (models 3 and 4) are instruments of legislative cooptation. Consistent with H

![]() $_1$

, we find that both are positively associated with cooperation; a standard deviation increase in oil price or revenues is associated with a predicted 2.8 or 2.3 percentage point increase, respectively, in voting with the regime. These effects are significant at the

$_1$

, we find that both are positively associated with cooperation; a standard deviation increase in oil price or revenues is associated with a predicted 2.8 or 2.3 percentage point increase, respectively, in voting with the regime. These effects are significant at the

![]() $\alpha \,=\,0.001$

level and are largely unchanged with the inclusion of legislator fixed effects.

$\alpha \,=\,0.001$

level and are largely unchanged with the inclusion of legislator fixed effects.

Table 2. Cooptation strategy and voting with the regime. The table reports coefficients from OLS models of voting consistent with the minister bloc at the legislator-vote level. All models include term fixed effects and controls for law type. Models alternately include controls for legislator attributes (age, gender, education, sect, occupation, tribal affiliation, and electoral performance) or legislator fixed effects. WTI price and oil revenues are standardized continuous variables. Full results are printed in Table A.4

Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

How should we interpret this effect? A stronger economy is expected to increase government approval and electoral support among citizens – might this extend to policy voting behaviour among the elite? The health of the Kuwaiti economy is indeed closely tied to oil price – yet we find that this effect is present even when controlling for inflation, another measure of economic health that may be even more salient to consumers.Footnote 33 Qualitative evidence makes clear that corruption (in particular, misuse or embezzlement of state funds) is a serious problem in Kuwait, and public accounts frequently implicate members of the royal familyFootnote 34 as well as elected officials. Additionally, these accusations of corruption have been linked to oil itself, with multiple former Ministers of Oil (including members of the al-Sabah family) investigated for involvement in graft.Footnote 35 In 2011, a Kuwaiti newspaper reported that 17 million Kuwaiti dinars ($61 million USD) were deposited into a legislator’s bank account, leading to a major investigation into legislative corruption.Footnote 36 Ultimately, though the surreptitious nature of corruption means that extracting systematic evidence of oil money being funnelled to elected lawmakers is not possible, we argue that the findings here are consistent with our argument that oil revenues can be used by the regime to elicit elite policy cooperation.

To test H

![]() $_2$

, each model also includes the ideological dummy and our measure of cabinet affiliation. Ideological legislators are, on average, less likely to vote with the regime, suggesting that participation in a political bloc is an indicator of policy opposition. Yet, as predicted, we find that these legislators increase their level of cooperation when they have an affiliate on the cabinet. The addition of one affiliated cabinet member is associated with an expected 1.6 percentage point increase in cooperation with the Council of Ministers. The coefficient on cabinet affiliation is positive and significant in all specifications, though the magnitude is somewhat smaller in models with legislator fixed effects. We discuss the implications of this finding and possible mechanisms in more detail in the next section.

$_2$

, each model also includes the ideological dummy and our measure of cabinet affiliation. Ideological legislators are, on average, less likely to vote with the regime, suggesting that participation in a political bloc is an indicator of policy opposition. Yet, as predicted, we find that these legislators increase their level of cooperation when they have an affiliate on the cabinet. The addition of one affiliated cabinet member is associated with an expected 1.6 percentage point increase in cooperation with the Council of Ministers. The coefficient on cabinet affiliation is positive and significant in all specifications, though the magnitude is somewhat smaller in models with legislator fixed effects. We discuss the implications of this finding and possible mechanisms in more detail in the next section.

Cabinet appointments and policy concessions

The analysis in Table 2 demonstrates that both oil rents and cabinet positions are associated with increased policy cooperation within legislative terms and for individual legislators. We argue that these serve as plausible proxies for the marginal value (and availability) of rents to the regime, and for the regime’s distribution of policy concessions to ideological groups represented in the legislature. The idea that cabinet appointments serve as observable indicators that policy concessions are likely occurring is of particular interest since it is challenging to empirically document examples of regimes engaging in policy compromise with ideological opposition in the legislature.Footnote 37 In this case, our interpretation of this measure is derived from the institutional role of the Council of Ministers in formulating draft policy. We assume that ideological affiliates on the cabinet are able to influence legislative proposals in ways that reflect their legislator colleagues’ policy preferences. But is this interpretation warranted?

Historical evidence suggests that opposition groups in the legislature are indeed able to extract policy concessions. After the Iraqi invasion and occupation of Kuwait and the 1992 election, the ruling family invited six elected legislators representing different ideological groups to participate in the Cabinet. According to Ghabra (Reference Ghabra1993, 19), ‘The raison d’etre of the opposition members of the government was the initiation of reform programs in and through their ministries, to put into practice the ideals and slogans of the campaign.’ The practice of incorporating ministers into the cabinet predates the 1992 election. But widespread criticism of the government’s conduct during the invasion and subsequent occupation compelled the ruling family to incorporate a broader set of actors into the policymaking process more seriously. The government typically informally invites individuals to participate in government by direct invitation. In other words, ideological movements do not nominate a minister to participate in the Council of Ministers. In a few instances, ideological movements have even censured individuals for joining the Cabinet or supporting laws at the Cabinet’s request. In sum, there is neither a prior period of ideological cooptation that takes place prior to the formation of a Cabinet, nor is there an expectation or requirement that ideologically aligned legislators vote with the government in instances where the government has included an ideological affiliate in the Cabinet.

The informality of the Cabinet formation process has created a dynamic whereby both the government and ideological movements can jointly claim credit for the passage of specific laws. For example, in 1996, Islamist political groups in the legislature worked with the Council of Ministers to pass a law ending co-education at Kuwait University. Though the government had repeatedly opposed efforts to enforce gender segregation, it eventually caved. Similarly, in 2008, the government appointed a member of the National Islamic Coalition, a Shia Islamist group, as Minister of Public Works and Minister of State for Municipal Affairs. Analysts and observers speculated that the appointment would allow the new minister to expand permits and licenses for hussainiyat, or congregation halls, for Shia religious ceremonies. In exchange, the group’s elected legislators were expected to support the Council of Ministers in the legislature. We discuss these groups in greater detail and provide additional examples of policy concessions in Section S.3 in the Supplementary Materials appendix. To complement these examples, we further probe the Cabinet Affiliate effect identified using the roll call vote data. Though this variable is associated with cooperative votes, there are competing explanations that might underlie this finding. First is our presumption that cabinet members are able to influence draft legislation in ways conforming to their ideological group’s preferences. In the main analysis, we bundle all cabinet portfolios together to show that having an affiliate – in any position – on the Council of Ministers is associated with policy cooperation in general. But a minister’s influence is most plausible in the context of policy related to his/her assigned portfolio. We therefore construct the variable Topical Portfolio, coded as 1 if the legislator’s cabinet affiliate held a portfolio that was topically relevant to the legislation being voted on.Footnote 38

However, it is also possible that cabinet affiliates simply help to rally votes for the regime, in a role akin to party whips. Ideological ministers can vote on legislation themselves; their presence during a policy vote might pressure their compatriots in the legislature to comply with the regime’s wishes or serve as a signal of which way to vote to uninformed legislators. While interesting, this explanation does not necessarily require that policy concessions be granted. To test whether the significance of cabinet affiliates is transmitted through their presence in the legislature, we introduce the variable Affiliates Present, coded as 1 for any vote where at least one affiliated cabinet member was present and voted along with the rest of the minister bloc.

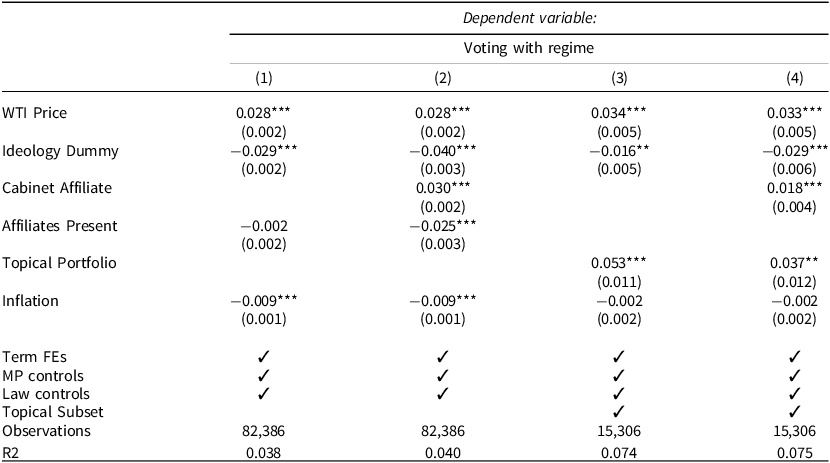

In Table 3, we report specifications, including these indicators, on their own or alongside the Cabinet Affiliate measure. Specifications include term FEs, law controls, and legislator controls.Footnote 39 For specifications with the Topical Portfolio variable, we subset to include only votes that concerned at least one of the four law topics (that is, votes that were eligible for treatment). We find that the presence of an affiliated cabinet member during a vote is not associated with policy cooperation; Affiliates Present has a null effect alone and becomes negative in combination with the Cabinet Affiliate variable.Footnote 40 We interpret this as evidence that the effectiveness of cabinet ministers is not transmitted primarily through their visibility during second deliberation votes. Turning to the analysis of topically relevant portfolios, we find that holding a portfolio related to the topic in question is associated with a substantively larger, positive effect on policy cooperation: Topical Portfolio is associated with a 5.3 percentage point increase in voting with the regime. This remains positive even when the general Cabinet Affiliate measure is included, implying that legislative cooperation is especially strong in scenarios where policy concessions are most likely to have been granted. This analysis should be seen as suggestive, but it is consistent with our claim that cabinet positions offered to ideological groups are evidence of policy concessions.

Table 3. Cabinet portfolios – possible mechanisms. The table reports coefficients from OLS models of voting consistent with the minister bloc at the legislator-vote level, including metrics of minister attendance (Affiliates Present) and portfolio relevance to the issue being voted on (Topical Portfolio). All models include term fixed effects and controls for law type and legislator attributes

Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Ideological representation and regime strategy

We argue that rents and policy concessions are exchanged for policy cooperation through the process of legislative cooptation. In the preceding sections, we find empirical support for our hypotheses that observable measures of these mechanisms are, in fact, associated with voting in accordance with regime preferences. Yet we posit that these mechanisms are not entirely interchangeable: individual legislators will value the two mechanisms differently. In H

![]() $_3$

, we predict that policy-seeking legislators (proxied here as legislators with an ideological affiliation) prefer policy concessions to rents, and will therefore be less responsive to the oil rent indicator.

$_3$

, we predict that policy-seeking legislators (proxied here as legislators with an ideological affiliation) prefer policy concessions to rents, and will therefore be less responsive to the oil rent indicator.

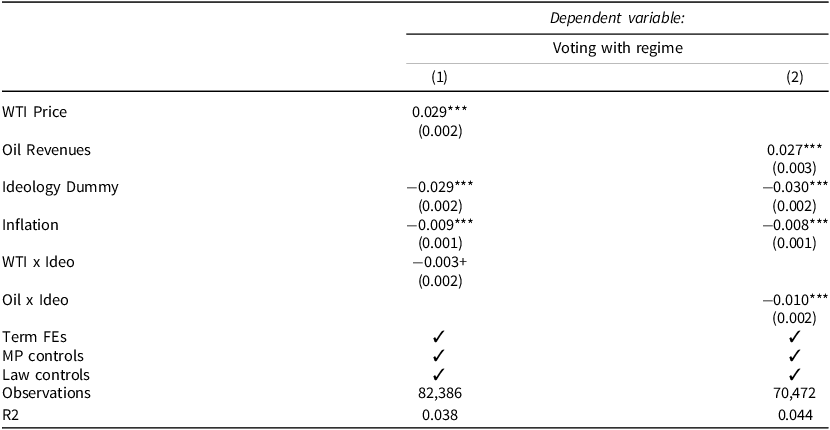

To test this, we interact oil metrics with a measure of legislator ideology in Table 4. The interaction coefficient is negative in both specifications, though it is substantively larger and significant at the 0.001 level in the specification including actual Kuwaiti oil revenues. Though an increase in oil revenues still predicts policy cooperation for ideological legislators, the predicted increase is less than half of that of a non-ideological deputy. There are limitations to this test: ideological affiliations may not fully capture legislators’ relative interest in policy concessions. However, we interpret this as evidence that policy-oriented legislators are less moved by oil rents than other legislators.

Table 4. Table reports coefficients from OLS models of voting consistent with the minister bloc at the legislator-vote level. Models include fixed effects and controls for the type of law as indicated. Full results are printed in Table A.5

Note: +p

![]() $ \lt $

0.1; *p

$ \lt $

0.1; *p

![]() $ \lt $

0.05; **p

$ \lt $

0.05; **p

![]() $ \lt $

0.01; ***p

$ \lt $

0.01; ***p

![]() $ \lt $

0.001

$ \lt $

0.001

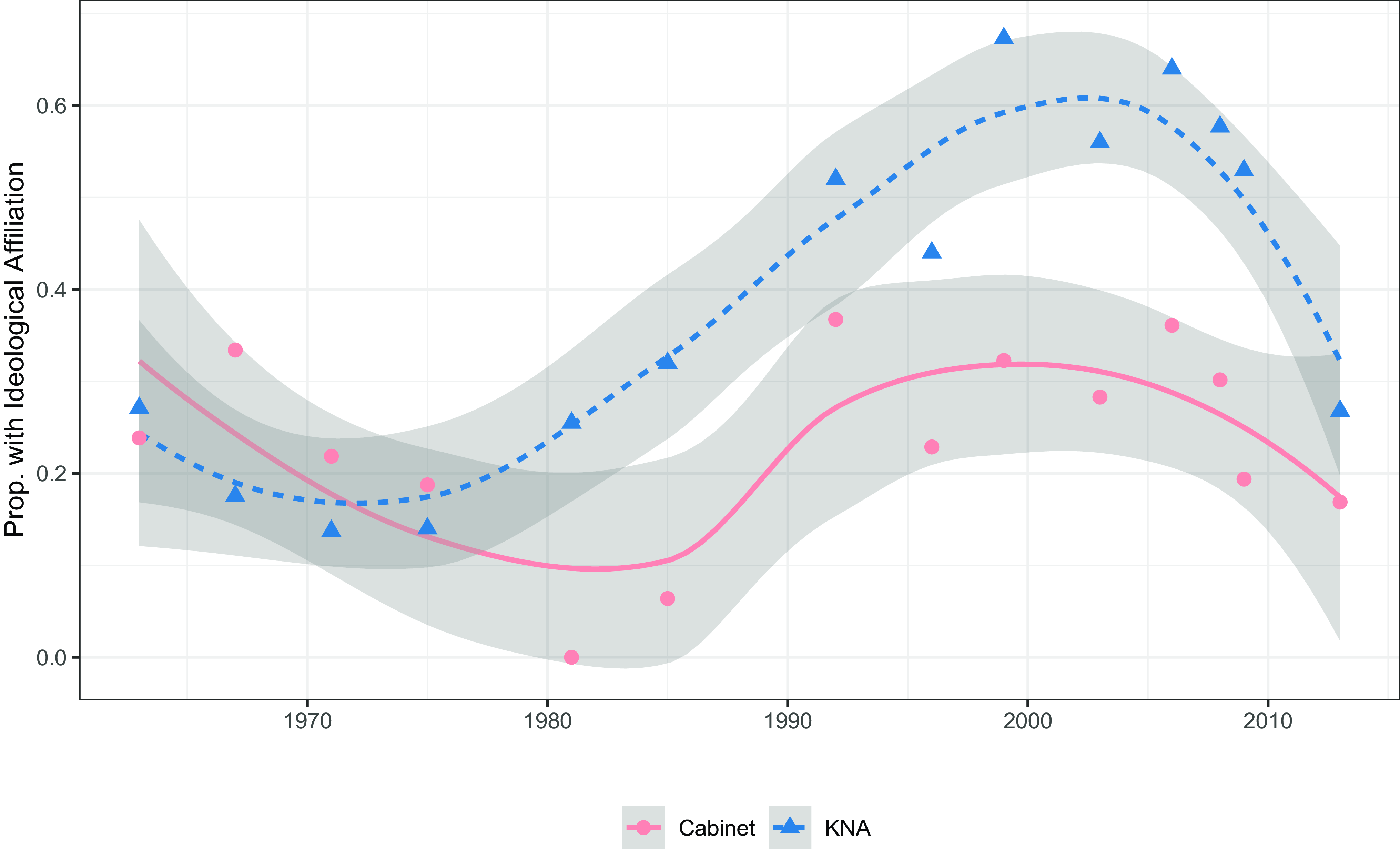

If legislators of different types respond differently to these two mechanisms, then the regime cannot use them entirely interchangeably. We finally consider the regime’s use of the mechanisms as a response to legislative composition. In particular, we consider the regime’s decision to include ideological movements in the Council of Ministers. Figure 5 plots the proportion, by term, of ideological legislators and cabinet members. The two measures are positively correlated (

![]() $r\,=\,0.5$

).Footnote

41

$r\,=\,0.5$

).Footnote

41

Figure 5. Ideological Representation in the Kuwaiti Cabinet and National Assembly.

Note: The plot depicts the proportion of KNA legislators (dark blue) and cabinet members (light blue) with ideological affiliations by term, 1963–2013 (excludes the two short-lived assemblies elected in 2012). Source: KNA-RCV dataset.

In a democracy with parliamentary institutions, this pattern would be unremarkable: the government formed is institutionally required to reflect the characteristics of the elected legislature.Footnote 42 Yet this is not the case in this authoritarian setting. The Emir has sole discretion over cabinet appointments; he is in no way bound to select ministers based on the outcome of national elections. The finding that the proportion of ideologically linked cabinet ministers is predicted by ideological representation in the legislature is fascinating evidence of responsiveness to legislative composition. This does not follow institutional rules; we propose that it demonstrates strategic behaviour by the regime. In light of the preceding evidence that cabinet positions do, in fact, represent policy concessions to ideological movements in the legislature, this suggests that authoritarian elections have consequences for policymaking. Some form of policy representation is present even in this setting where legislators seem to consistently support regime policy in a majority of cases.

Conclusion

In this article, we systematically examine voting behaviour across the entire history of an authoritarian legislature and directly measure cooperation with and opposition to regime policy preferences. Substantively, we find that 10 per cent of final roll call votes in the KNA are in opposition to regime preferences. The regime does, on occasion, lose a policy vote – but, much more often, the regime wins with a supermajority of support. The high degree of cooperation, even when many opposition legislators are present, suggests the regime seeks more than a minimum winning coalition. There are a number of possible explanations for this emphasis on consensus – as with dominant showings in national electoral contests, a legislative supermajority offers a show of strength that might deter individual opposition (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006). Yet this descriptive observation could be built on with further theoretical and empirical research.

We argue that policy cooperation is the result of a strategic interaction between the regime and elected legislators. We empirically test our theory of legislative cooptation – the intentional exchange of economic rents or policy concessions to rival elites for compliance with the autocrat’s policy agenda. We find that a standard deviation increase in the availability of economic rents is associated with a 2.3 percentage point increase in cooperation with the regime – and that a similarly positive effect (1.6 percentage points) is produced with the addition of an ideologically affiliated cabinet member.

Though these findings suggest both economic rents and policy concessions facilitate cooperation with the regime on policy votes, there are distinct normative implications for the two mechanisms. The former mechanism suggests resource wealth allows leaders to buy off the political elite within the legislative arena (Ross Reference Ross2015). However, the latter, along with the data on cabinet composition over time, evokes a political environment that functions in a manner closer to a stylized version of democratic polities; ideological groups attract votes, succeed in office, and are granted policy influence related to their degree of popular support.Footnote 43 The distinction is that, here, cabinet representation occurs not because institutional rules require it but, rather, because the regime is incentivized to offer it in order to secure legislative cooperation on policy votes. This is novel evidence that legislative composition – and hence, electoral outcomes – can influence policymaking in an authoritarian setting.

This article is not the first to explore the inner workings of legislatures in authoritarian contexts. A growing body of empirical work has found that authoritarian institutions respond to citizen needs (Distelhorst and Hou Reference Distelhorst and Hou2017), reflect citizen interests on non-sensitive issues (Truex Reference Truex2016), and resolve internal disputes within the regime (Lü et al. Reference Lü, Liu and Li2020; Noble Reference Noble2020). But despite these important advances, less attention has been given to the question of how the regime manages potential opposition in office.Footnote 44 Data availability has long hampered efforts to study the internal operation of these institutions. With this project, we bring a rich new data source to bear on the question of policy opposition in authoritarian regimes. Our findings underscore that legislator behaviour is not entirely sycophantic. In addition to showing that a subset of laws pass in these contexts against the regime’s wishes, we find substantial variation in voting patterns at the individual level. Most importantly, we find evidence that cooptative exchanges are effective in buying support from elected representatives on their policy agenda.

To what extent do our findings generalize beyond Kuwait? Our analysis of roll call votes spans the entirety of Kuwait’s legislative history, but, as we describe above, Kuwait is not the only authoritarian institution to make meeting minutes publicly available.Footnote 45 In fact, similar data analyzing legislative behaviour has been presented in a variety of authoritarian regimes that span both more open and closed systems. Our focus on a legislature endowed with lawmaking power draws attention to a core scope condition of our findings. It may be that unique features of the case explain these findings, though we cannot easily test whether this might be the case. Though popular and press accounts of Kuwait describe the legislature as unruly, we still find a significant degree of consensus that mirrors policymaking in more closed systems. Therefore, we believe that the legislature’s ability to approve or pass laws – its lawmaking authority – can be used to generate a set of ‘most plausible’ cases from the global landscape of authoritarian regimes (Berman Reference Berman2021). Similar cases where this condition is met include Iran, Iraq, Jordan, and Morocco in the Middle East and North Africa, and Kenya, Tanzania, Thailand, and Singapore outside the region.

We see two promising pathways for further study that can build on these findings. First, a critical debate among scholars of authoritarian institutions revolves around whether these institutions function analogously to their democratic counterparts or whether they represent a wholly different form of politics (Gandhi et al. Reference Gandhi, Noble and Svolik2020). Our findings suggest that both conceptions can be true within the same body. We find that executive coalition-building and related policy inclusion leads political outsiders to cooperate on policy: exactly the kind of compromise we would expect in a robust, representative legislature. Yet we also find evidence that the regime uses less aboveboard means – its vast fiscal resources – to generate the same cooperative spirit. This latter activity (with its presumed dependence on individual transfers in exchange for support) is wholly distinct from normative conceptions of democratic representation. This raises intriguing questions about the circumstances under which one or another mechanism of legislative cooptation is more prevalent: resource-poor states or those facing economic contraction may be forced to offer more policy concessions; for example, while those with high economic control and limited legislative autonomy may have more discretion over cooptation strategy. If representation in these contexts is a real possibility, future research should aim to evaluate both its limits and the conditions under which authoritarian regimes will tolerate it. It would also be constructive to explore variation in the forms and prevalence of legislative cooptation across varying institutional circumstances.

Second, it remains an open question whether legislative opposition actually matters in authoritarian regimes with permissive institutions with lawmaking authority. In our study, we use a novel measure of cooperation to provide evidence that it does: autocrats go to great (and costly) lengths to minimize their public presence in the legislature – even when proposals are not at risk of legislative failure. Our findings indicate that positive inducements such as economic rents and policy concessions can facilitate the legislative cooperation autocrats require to achieve their policy goals and demonstrate their strength. But more work is needed to understand the reverse, or the kinds of inducements that can effectively counter these tactics and encourage the development of robust opposition.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123424000371

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/E6YVYQ

Acknowledgements