Introduction

Concerns are growing about the psychological impact of community crime in older victims (Burnes et al., Reference Burnes, Henderson, Sheppard, Zhao, Pillemer and Lachs2017; Muhammad et al., Reference Muhammad, Meher and Sekher2021; Qin and Yan, Reference Qin and Yan2018). These are crimes committed by strangers or acquaintances (World Health Organisation, 2023), which have been overlooked in research compared with elder abuse and domestic violence (e.g. Knight and Hester, Reference Knight and Hester2016; Roberto and Hoyt, Reference Roberto and Hoyt2021; Yunus et al., Reference Yunus, Hairi and Choo2019). Whilst prevalence data are lacking, an estimated 26,541 community crimes were reported by older victims aged 65 and over in 2022–2023 in London (UK) alone (M.P.S. personal communication, 2023) and, given that 60–70% of crimes go unreported (Buil-Guil et al., Reference Buil-Gil, Medina and Shlomo2021; MacDonald, Reference MacDonald2002), the true figure may be even higher. Whilst many older victims of community crime cope well, the consequences for others can be debilitating (HMICFRS, 2019; Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Hatton, Malone, Fryer, Walker, Cunningham and Durrani2003). An estimated 28% of older victims of different crime types continue to suffer depression and/or anxiety 3 months later (Serfaty et al., Reference Serfaty, Ridgewell, Drennan, Kessel, Brewin, Leavey, Wright, Laycock and Blanchard2016), which is considerably higher than rates of depression (7%) and anxiety (4%) in older people globally (World Health Organisation, 2017). Burglary (odds ratio [OR]: 2.4) and violent crime (OR: 2.1) have been associated with accelerated mortality and increased risk of nursing-home placement (Donaldson, Reference Donaldson2003; Lachs et al., Reference Lachs, Bachman, Williams, Kossack, Bove and O’Leary2006). There are also reports of older victims changing their behaviour after a crime; including avoiding online banking (Tripathi et al., Reference Tripathi, Robertson and Cooper2019), increasing security (Qin and Yang, Reference Qin and Yan2018), and praying for protection (Satchell et al., Reference Satchell, Dalrymple, Leavey and Serfaty2023). It is unclear whether these changes reflect healthy coping or safety-seeking behaviours, which are potentially maladaptive.

Safety-seeking behaviours are unnecessary or dysfunctional overt or covert actions intended to prevent, escape, or reduce risk or severity of potential threats (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1991; Telch and Lancaster, Reference Telch, Lancaster, Neudeck and Wittchen2012). This may range from outright avoidance to subtle behaviours like checking (Hoffman and Chu, Reference Hoffman and Chu2019) and may be cognitive or behavioural (Rachman, Reference Rachman1997). Their presentation varies based on the individual’s specific concerns (Goetz et al., Reference Goetz, Davine, Siwiec and Lee2016).

Safety-seeking behaviours are dysfunctional because they maintain threat perception (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1991). When feared outcomes do not occur, individuals may attribute this to their behaviour instead of the lack of danger (Lovibond et al., Reference Lovibond, Saunders, Weidemann and Mitchell2008). They may make anxiety tolerable, preventing opportunities for habituation (Sharpe et al., Reference Sharpe, Todd, Scott, Gatzounis, Menzies and Meulders2022), and even make feared outcomes more likely (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Sacadura and Clark2008). For example, excessively checking locks when leaving home may draw attention to it being vacated. Of the few crime victim studies, safety-seeking behaviours were significantly associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in middle-aged physical and sexual assault victims (Dunmore et al., Reference Dunmore, Clark and Ehlers1999; Dunmore et al., Reference Dunmore, Clark and Ehlers2001) and student and middle-aged trauma populations, including assault victims (Blakey et al., Reference Blakey, Kirby, McClure, Elbogen, Beckham, Watkins and Clapp2020). However, details on assessment were limited (Dunmore et al., Reference Dunmore, Clark and Ehlers1999; Dunmore et al., Reference Dunmore, Clark and Ehlers2001) or it was unreported whether measures had been pre-tested for suitability in this population (Blakey et al., Reference Blakey, Kirby, McClure, Elbogen, Beckham, Watkins and Clapp2020).

It has long-been recognised that improved assessment of safety-seeking behaviours is needed (Telch and Lancaster, Reference Telch, Lancaster, Neudeck and Wittchen2012). Most measures are for specific disorders, such as social anxiety (e.g. Cuming et al., Reference Cuming, Rapee, Kemp, Abbott, Peters and Gaston2009) or phobias (e.g. Krause et al., Reference Krause, Macdonald, Goodwill, Vorstenbosch and Antony2018), limiting their applicability to other populations. They also list specific behaviours, pre-determined by researchers, which may not apply to that individual. For example, the Post-Traumatic Safety Behaviour Questionnaire (Blakey et al., Reference Blakey, Kirby, McClure, Elbogen, Beckham, Watkins and Clapp2020), which has been used with crime victims, has some items which may be relevant (e.g. ‘Require the presence of a ‘safe person’ in public places’) and some intended for other fears (e.g. ‘Carefully eliminate all distractions while driving’). Even measures specifically for crime victims (Dunmore et al., Reference Dunmore, Clark and Ehlers1999; Dunmore et al., Reference Dunmore, Clark and Ehlers2001) may not fully capture behaviours as some may ‘avoid unfamiliar places’, while others may go to unfamiliar places but only in daytime or avoid going out altogether. These measures also rate behaviours based on how often they are engaged in, rather than how much of a change this is since the crime (or index trauma), making it unclear whether these are new or pre-existing behaviours.

Existing measures therefore have limited content validity, especially in crime victims, and may perpetuate misconceptions that safety-seeking is defined by particular behaviours rather than their underlying functions (e.g. avoidance) (Hoffman and Chu, Reference Hoffman and Chu2019). As safety-seeking is idiosyncratic (Goetz et al., Reference Goetz, Davine, Siwiec and Lee2016), individuals should be asked what they consider to be threatening (Gústavsson et al., Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021). Victims of crime or other adverse events should also be asked whether these behaviours are a change since the incident.

A person-reported approach to measuring safety-seeking behaviours

Mixed-methods assessment tools, such as patient-generated measures, may offer a solution to safety-seeking behaviour assessment as they incorporate personal perspective while generating data that can be compared across participants (Cox and Klinger, Reference Cox and Klinger2021; Regnault et al., Reference Regnault, Willgoss and Barbic2017). They ask respondents to qualitatively describe the problem most affecting them and then rate it on a scale (Paterson, Reference Paterson1996; Ruta et al., Reference Ruta, Garratt, Leng, Russell and MacDonald1994). For example, the Psychological Outcome Profiles (PSYCHLOPS; Ashworth et al., Reference Ashworth, Shepherd, Christey, Matthews, Wright, Parmentier, Robinson and Godfrey2004), asks respondents to: ‘Choose the problem that troubles you most’ (qualitative response) and ‘Score how much has it affected you over the last week’ (0: ‘not at all affected’ to 5: ‘severely affected’). The PSYCHLOPS is person-centred and has been found to have good acceptability amongst patients and therapists (Antunes et al., Reference Antunes, Sales and Elliott2020). It is sensitive to change (Ashworth et al., Reference Ashworth2007), and over two-thirds of reported items were not found on quantitative comparators (Sales et al., Reference Sales, Neves, Alves and Ashworth2018). However, work to establish its reliability and validity remains ongoing (Sales et al., Reference Sales, Faísca, Ashworth and Ayis2023).

Mixed-methods approaches are recommended when measuring experiences uniquely known to the respondent (Black, Reference Black2013). However, questions remain about how best to develop and evaluate them, as not all conventional tests of psychometric quality are appropriate (Lyon et al., Reference Lyon, Connors, Jensen-Doss, Landes, Lewis, McLeod, Rutt, Stanick and Weiner2017; Sales et al., Reference Sales, Neves, Alves and Ashworth2018). For example, inter-rater reliability does not apply, as the measure relies on self-report rather than external observation. Similarly, the focus on subjective perspectives means they cannot be meaningfully compared with objective or independent assessments (Howell et al., Reference Howell, Amir, Guha, Manera and Tong2022). The assumption that they can assess the criterion variable equally well across the entire sample also remain untested. Furthermore, changes in how individuals understand or evaluate their own behaviour – such as during the course of therapy – can lead to response shifts, which may be misinterpreted as unreliability, when in fact they reflect the genuine therapeutic progress (van der Willik et al., Reference van der Willik, Terwee, Bos, Hemmelder, Jager, Zoccali, Dekker and Meuleman2021).

Despite these challenges, mixed-methods tools are well-suited to capturing individual behaviours, and health authorities internationally are increasingly advocating for wider use of experience-centred measures (OECD; 2024). Feasibility research is therefore needed to address this research gap (Ashworth et al., Reference Ashworth, Guerra and Kordowicz2019). Initial guidance recommends establishing content validity as the first critical step, to ensure the measure captures the concept of interest (Food and Drug Administration, 2009). This requires accumulating supportive quantitative and qualitative evidence to demonstrate relevance, clarity, and comprehensiveness (Cappelleri et al., Reference Cappelleri, Jason Lundy and Hays2014; Food and Drug Administration, 2009; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Elsworth and Osborne2018). Once achieved, subsequent evaluation can be considered, involving two phases: (1) feasibility via exploratory analyses and (2) confirmatory psychometrics to establish measurement characteristics (Cappelleri et al., Reference Cappelleri, Jason Lundy and Hays2014).

Aims

We firstly aimed to document safety-seeking behaviours used by older victims of community crime and quantitatively investigate whether these are associated with continued psychological distress at 3 months post-crime. To do this, we secondly aimed to design a novel person-reported safety-seeking behaviour measure (PRSBM) to collect mixed-methods data. As the potential benefits of a person-reported approach may extend beyond this population, we purposefully designed our measure to be broadly applicable to adverse events. Our third aim was therefore to use this sample to begin the first phase of feasibility evaluation by assessing the PRSBM’s content validity, usability and acceptability, and to explore its psychometric properties using a novel statistical technique (unique variable analysis).

Method

Setting

We nested our study within a randomised controlled trial of adapted cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for victims of community crime aged 65 and over in London (UK), in collaboration with the police and a mental health charity (for details, see Serfaty et al., Reference Serfaty, Satchell, Lee, Laycock, Brewin, Buszewicz, Leavey, Drennan, Vickerstaff, Cooke and Kessel2025). Older victims reporting a crime to the police were screened for distress symptoms within 2 months by community support officers using the 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-2) (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2003; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, Monahan and Löwe2007). These officers collected sociodemographic data and obtained consent for data-sharing and contact from university researchers. Distressed older victims were followed up 3 months later and reassessed on the PHQ-2/GAD-2 by researchers and, if still distressed, recruited into the trial. This study utilized the PHQ-2/GAD-2 data from the 3-month follow-up for initially distressed older victims, collected between June 2018 and September 2019.

Measures

We defined continued psychological distress as a score of 2 or more on the GAD-2 and/or 3 or more on the PHQ-2 at 3 months post-crime.

Patient Health Questionnaire-2

The PHQ-2 (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2003) is a rapid and reliable screening tool for depression, which assesses two symptoms over the preceding 2 weeks: (1) Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless and (2) Little interest or pleasure in doing things. Items are scored on 4-point scales (0–3), giving a maximum score of 6, with a score of 3 or more indicating depression. The PHQ-2 is reported to have excellent discriminant validity, and acceptable sensitivity and specificity (Staples et al., Reference Staples, Dear, Gandy, Fogliati, Fogliati, Karin, Nielssen and Titov2019) and internal consistency (α=0.79) (Bisby et al., Reference Bisby, Karin, Scott, Dudeney, Fisher, Gandy, Hathway, Heriseanu, Staples, Titov and Dear2022). It has been validated in older adults (Li et al., Reference Li, Friedman, Conwell and Fiscella2007) and previously used in older victims (Satchell et al., Reference Satchell, Dalrymple, Leavey and Serfaty2023; Serfaty et al., Reference Serfaty, Ridgewell, Drennan, Kessel, Brewin, Leavey, Wright, Laycock and Blanchard2016).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2

The GAD-2 (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, Monahan and Löwe2007), abbreviated from the GAD-7, corresponds with DSM-IV generalized anxiety criteria (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006). It screens two anxiety symptoms over the preceding 2 weeks: (1) Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge and (2) Not being able to stop or control worrying. Items are scored on 4-point scales (0–3), giving a maximum score of 6. A score of 3 or more indicates anxiety in most populations, but a lower cut-off of 2 or more is recommended for older adults (Wild et al., Reference Wild, Eckl, Herzog, Niehoff, Lechner, Maatouk, Schellberg, Brenner, Müller and Löwe2014). Meta-analyses found that the GAD-2 has acceptable psychometric properties (Plummer et al., Reference Plummer, Manea, Trepel and McMillan2016), including internal consistency (α=0.84) (Bisby et al., 2022). It has been validated in older adults (Wild et al., Reference Wild, Eckl, Herzog, Niehoff, Lechner, Maatouk, Schellberg, Brenner, Müller and Löwe2014) and previously used in older victims (Satchell et al., Reference Satchell, Dalrymple, Leavey and Serfaty2023; Serfaty et al., Reference Serfaty, Ridgewell, Drennan, Kessel, Brewin, Leavey, Wright, Laycock and Blanchard2016).

Person-Reported Safety-seeking Behaviour Measure (PRSBM)

Our novel PRSBM (see Supplementary material) enquires about six safety-seeking behaviour functions: (1) Checking (There are things that people may check regularly), (2) Reassurance-Seeking (People may look for information or ask other people for their opinions to help them judge whether they are safe), (3) Rumination (People may go over in their mind how they can prevent a similar situation from happening again), (4) Avoidance (There are certain situations, places, people, or thoughts that people may avoid), (5) Rituals (If people suddenly think about something bad happening to them, there may be little things that they think, say, or do to help them feel better again), and (6) Hypervigilance (Some people may be alert for people or situations that could be a threat to them).

For each behaviour, respondents were asked at 3-month follow-up whether, since the incident: (A) This is something that I do (yes/no) and, if yes: (B) The thing I do the most is … (qualitative response). The qualitative responses are rated by respondents on two 7-point Likert scales: (C) Frequency: I do this (–3: ‘never’ to +3: ‘all the time’), and (D) Change: For me, this is … ((–3: ‘a lot less than before’ to +3: ‘a lot more than before’). The Frequency scale assesses the extent that respondents currently engage in the behaviour whilst the Change scale assesses whether this is a change from before the crime. We sat with participants so they could see the measure and read the questions aloud, writing behaviours as described verbatim by them and marking the scale option they said or pointed to. We sought to minimise socially desirable responding by completing the PRSBM during home visits, providing a confidential and comfortable setting that facilitated rapport-building.

PRSBM development

We aimed to develop a measure broadly applicable to any adverse event so our questions referred to negative ‘situations’ or ‘incidents’ instead of ‘crime’. The questions were informed by the existing literature and our Trial Management Group, including psychologists, psychiatrists, gerontologists, criminologists, statisticians, and two older adults with lived experience of being crime victims. Our lived experience advisors also provided initial guidance on its usability and acceptability (INVOLVE, 2021), before pre-testing in n=31 older victims using cognitive interviewing (Food and Drug Administration, 2009; Willis, Reference Willis1999). Based on their feedback, we refined the measure until the language and instructions were clear and acceptable.

Full details of amendments from pre-testing are available on request. Briefly, we found the PRSBM worked well when researcher assisted. Participants provided conceptually consistent responses to six safety-seeking behaviour functions (checking, reassurance-seeking, rumination, avoidance, rituals, hypervigilance). We tested two further questions (‘Doing things in a different way’ and ‘Any other examples’) but found that participants either repeated responses reported elsewhere or described single incidents which could not be meaningfully rated on the Frequency or Change scales (e.g. installing burglar alarms), so we dropped these from the measure. We tried asking participants to estimate how long they spent on each behaviour, which worked well for some (e.g. checking), but they struggled to meaningfully estimate how long they spent on avoidance, so we also dropped this. We tested different rating scale types and found that Likert scales were the most intuitive. Participants also recommended including ‘opt-out’ questions, so that they could skip behaviours which were irrelevant to them.

Qualitative analysis

We analysed person-reported responses using inductive codebook thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006; Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2022) in NVivo version 12.0 (2020). We read each response and assigned descriptive nodes. For example, ‘checking locks on doors’, and ‘doors are double-locked’ was coded ‘checking locks’ as they were conceptually similar. After describing items, we grouped similar items under parent nodes. For example, ‘checking locks’ and ‘checking lights are on when going out’ were categorised under ‘checking behaviours when leaving home’, while ‘checking windows have not been smashed’ and ‘checking jewellery is still there’ were grouped into ‘checking behaviours when returning home’. We then considered broader themes (e.g. ‘home security’).

Quantitative analysis

We explored the PRSBM’s psychometric structure using unique variable analysis (UVA; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Garrido and Golino2023) in R (R Core Team, 2023). UVA is a type of network analysis, which is useful for examining datasets where it is not yet known how variables relate to each other (Borsboom et al., Reference Borsboom, Deserno, Rhemtulla, Epskamp, Fried, McNally, Robinaugh, Perugini, Dalege, Costantini, Isvoranu, Wysocki, van Borkulo, van Bork and Waldorp2021). Items in a measure providing similar information tend to be highly correlated, so UVA compares every possible pairing of scales and presents these as figures called weighted topographical overlap (wTO). A wTO of 0.25 or over has been used to indicate ‘substantially high overlap’ in recent studies (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Delgadillo and Golino2023).

We tested associations between safety-seeking and continued distress in older victims at 3 months post-crime using logistic regression in SPSS version 27 (IBM Corporation, 2020). Our binary outcome variable was whether they scored as psychologically distressed or not on the PHQ-2/GAD-2 at 3 months post-crime. Our independent variables were the Frequency and Change scales for each behaviour on the PRSBM, which we treated as continuous (Robitzsch, Reference Robitzsch2020). Univariate logistic regression was used to test each item’s association with distress, adjusted for gender, age, and crime type. Variables significantly associated with distress (p<.05) after adjustment were selected for stepwise multi-variable logistic regression, using backwards elimination (p<.05), to compare their strength of association against each other. We tested Frequency and Change scales separately to minimize multi-collinearity.

Missing data

The developed PRSBM included a screening question ‘This is something that I do’ (yes/no) which instructed participants to skip irrelevant sub-items. We did not consider these as missing data as respondents were instructed to omit them. Those who selected ‘no’ were recoded on the frequency scales to –3 (never) and change scales to 0 (no more or no less than before), which was equivalent to not doing the behaviour, thereby preserving our sample size. We considered data missing if participants selected ‘yes’ but left scales blank. As the PRSBM was researcher-assisted, missing data were rare (3%), so we removed these cases through listwise deletion. As the GAD-2/PHQ-2 were also researcher-assisted and the PRSBM only conducted in those who had completed these, no outcome data were missing.

Results

We recruited N=100 initially distressed older victims, sample characteristics for which are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample characteristics (N=100)

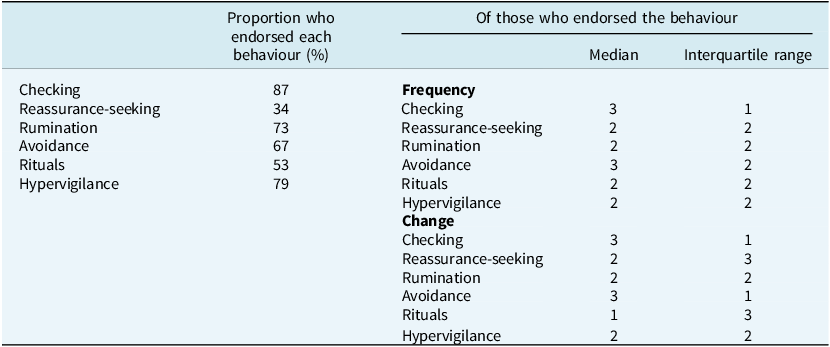

Checking was the most endorsed behaviour (n=87, 87%). Much of the sample also endorsed hypervigilance (83%), rumination (73%), avoidance (67%), and rituals (53%). Reassurance-seeking was the least common but was still endorsed by over a third (34%). As the data were not normally distributed, the averages for each scale are presented as medians and interquartile ranges (Table 2). Not all older victims engaged in all behaviours, but those who did tended to rate the frequency scales as ‘very often’ or ‘all the time’, and the change scales as ‘more than before’ or ‘a lot more than before’ the crime. The exception was rituals, which participants tended to rate that they did ‘very often’, but only ‘a little more’ than before the crime.

Table 2. Proportion who endorsed each behaviour, and distribution on the Frequency and Change scales of those who endorsed (N=100)

Frequency: ‘I do this’: never (–3), very rarely (–2), rarely (–1), half of the time (0), often (1), very often (2), all the time (3).

Change: ‘For me, this is…’: a lot less than before (–3), less than before (–2), a little less than before (–1), no more or no less than before (0), a little more than before (1), more than before (2), a lot more than before (3).

Qualitative findings

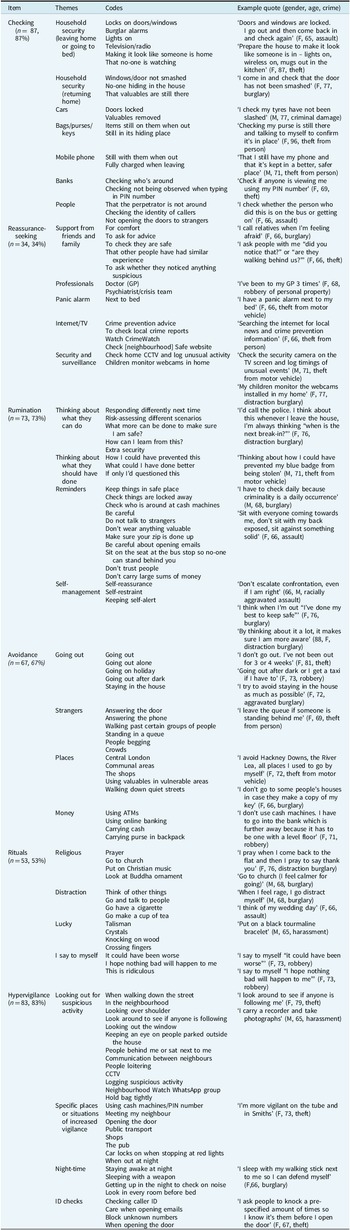

Older victims reported varied behaviours but all appeared conceptually related to the question (e.g. checking behaviours for the checking question) and to the crime they had experienced.

Checking

Participants often reported checking household security including locks, windows, burglar alarms, lights, or leaving televisions on to ‘give the appearance of someone at home’. Some checked when leaving the house or going to bed; others checked on their return for signs of damage, that no-one was hiding, or that valuables were still there. Older victims also checked their cars were locked, tyres ‘were not slashed’, or that mobile phones, keys, or purses were still with them. Some reported checking who was around or the identity of people calling them.

Reassurance-seeking

Older victims sought reassurance from friends, relatives, partners (e.g. ‘I call my family and friends when I cannot find my purse’), although one reported visiting their GP three times. This was to seek comfort, advice, ask whether loved ones were safe, or if others had had similar experiences. Some reported seeking-reassurance from the internet (e.g. crime reports) and another slept next to a panic alarm. One reported spending 6 hours daily watching home CCTV, and another reported her children had installed webcams to remotely monitor her safety.

Rumination

Rumination responses were broadly divided into thinking ‘what they should have done differently’ or ‘could do in the future’ including: risk assessments, imagining different scenarios, or mental reminders (e.g. Be careful opening emails). One older victim reported that keeping the crime on her mind helped her stay alert, while others found it offered self-reassurance (‘I think when I’m out “I’ve done my best to keep safe”’) or self-restraint (‘don’t escalate confrontation even when I’m right’).

Avoidance

Older victims avoided going out alone, after dark, and many reported not going out altogether (‘I haven’t been out for 3 or 4 weeks’). Others avoided staying home ‘in case somebody came’. Some avoided strangers, crowds, queues, certain people, ATMs, online banking, carrying cash, or answering the door or telephone. Others avoided specific places including shops, quiet streets, or high crime areas (e.g. ‘Central London’). Some reported an impact on their quality of life (‘we’ve stopped going on holiday’) or independence: (‘Places I used to go by myself’).

Rituals

Older victims reported faith practices (e.g. praying, attending church), good luck gestures (e.g. crossing fingers, crystals), or habits (e.g. smoking). Some reported cognitive rituals including distraction, thinking of happier times, or repeating messages (‘I tell myself “I’m being ridiculous”’).

Hypervigilance

Hypervigilance included looking for suspicious activity (e.g. ‘Looking out the window’), logging observations (e.g. Taking photographs), or reporting in neighbourhood WhatsApp groups. Some were hypervigilant in specific places (e.g. ‘public transport’) or situations (e.g. ‘When typing my PIN’). Some were hypervigilant at home, especially at night, including: staying awake, sleeping next to weapons, or getting up to check noises. Some reported holding their bags tightly or ‘asking people to knock a pre-specified amount of times so I know who is at the door’.

Quantitative analyses

Unique variable analysis

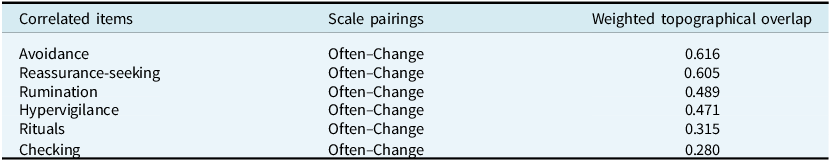

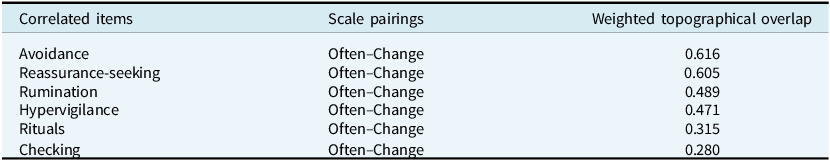

UVA found no overlap on any scale across behaviours (e.g. checking, avoidance), suggesting each contributed distinct information to the measure. However, the Frequency/Change scale pairs within each behaviour were found to have substantial overlap, with a wTO above 0.25 (Table 4). This overlap suggests that older victims who highly rated the Frequency scale for a behaviour also highly rated the corresponding Change scale, supporting that their behaviours were a change from before the crime.

Table 3. Summary overview of qualitative codes and themes in the PRSBM (N=100)

Table 4. Unique variable analysis

Logistic regression

We used variance inflation factor (VIF) to assess for multi-collinearity, which was found to be acceptable. However, as the UVA had identified high overlap on the Frequency/Change pairs for each behaviour, we adopted a cautious approach and tested the Frequency and Change scales separately. Analysis of residuals detected no outliers on the Frequency scales. On the Change scales, there was one for reassurance-seeking (Std. residual=–2.65), two for avoidance (Std. residual=3.23), two for rituals (Std residual=3.40), and one for hypervigilance (Std. residual=2.95). Visual inspections found that the same two participants reported engaging in behaviours a lot more than before the crime but scored negative for continued distress. The qualitative data showed one had lost their purse and now avoided carrying cash. Another had been burgled and reported not going out as much. These cases were removed through listwise deletion.

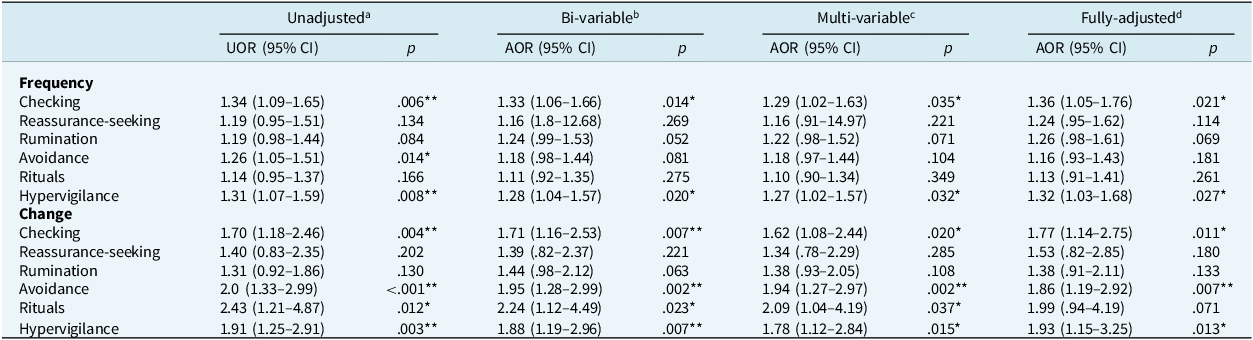

Univariate logistic regression (Table 5) found that reassurance-seeking and rumination were not significantly associated with continued distress on either scale. Rituals were not associated with continued distress on the Frequency scale but were on the Change scale. Checking, avoidance, and hypervigilance were each associated with continued distress on both scales. This suggests that for every point increase on these scales, the odds of continued distress were increased. The Change scales had especially high odds: 2.5 for rituals, 2.0 for avoidance, 1.91 for hypervigilance, and 1.70 for checking. Adjusting for gender, age, and crime type produced broadly similar estimates, suggesting associations were unaltered. The exceptions were avoidance ‘frequency’ (adjusted for gender) and rituals ‘change’ (adjusted for gender, age, and crime type), which became non-significant, so were dropped from further analyses.

Table 5. Univariate logistic regression testing safety-seeking behaviours and psychological distress (n=100)

a Univariable models for each safety-seeking behaviour using Frequency and Change scales; badjusted for gender; cadjusted for gender, age; dadjusted for gender, age, crime type. *Significant (p<.05), **significant (p<.01). UOR, unadjusted odds ratio; AOR, adjusted odds ratio.

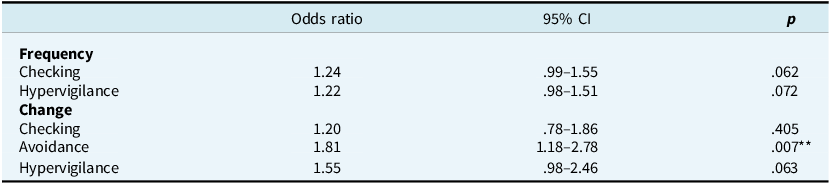

For the multi-variable model, we carried forward variables significant at p<.05 on the fully-adjusted univariable logistic regression: checking (frequency, change), avoidance (change), and hypervigilance (frequency, change) with backwards elimination at p<.05 (Table 6). Backwards elimination removed both scales for checking and hypervigilance, but retained avoidance (change), suggesting a change in avoidance was most strongly associated with continued distress.

Table 6. Multi-variate logistic regression using backwards elimination (p<.05)

** Significant (p<.01).

Discussion

We are the first to develop a person-reported safety-seeking behaviour measure (PRSBM), designed with broad applicability to adverse events, and to test its sensitivity in a preliminary sample of older victims. Using robust mixed-methods, we collected rich participant-derived behaviour data and examined associations with continued psychological distress in older victims.

PRSBM

Older victims’ qualitative responses were wide-ranging but overall, their behaviours conceptually corresponded with the crimes they had experienced. Many suffered property-related crimes, so there were common themes (e.g. lock checking) as well as differences. For example, ‘checking the car’ meant locks for one participant and that tyres had ‘not been slashed’ for another. This reinforces that safety-seeking reflects individuals’ core concerns (Goetz et al., Reference Goetz, Davine, Siwiec and Lee2016; Gústavsson et al., Reference Gústavsson, Salkovskis and Sigurðsson2021) and affirms that qualitative components to safety-seeking behaviour assessment are important. This highlights the limitations of existing measures, which use items prescribed by researchers.

Despite the breadth of responses, behaviours were compatible with the questions (i.e. checking behaviours reported for the checking question). This supports that safety-seeking behaviours are about their underlying function, rather than outward presentation (Hoffman and Chu, Reference Hoffman and Chu2019), and suggests our measure was sensitive to these. Although we pre-tested a version of the PRSBM which asked participants whether they had ‘Any other examples’, we found this did not yield any new information, suggesting that the 6-item version (checking, reassurance-seeking, rumination, avoidance, rituals, hypervigilance) was sufficient. In summary, our 6-item PRSBM appeared able to comprehensively capture nuances and commonalities in safety-seeking behaviours.

Most older victims endorsed engaging in five of the behaviours (checking, rumination, avoidance, rituals, hypervigilance). Reassurance-seeking was least common but still endorsed by over a third. High protective behaviour rates have been reported previously (Qin and Yan, Reference Qin and Yan2018), but it was unclear whether these were specific to older victims or older people generally, or whether these were associated with distress. Whilst our cross-sectional study cannot definitively rule out whether behaviours reported on the PRSBM were pre-existing, we did ask whether they were a change since the crime. Reporting biases are possible as older victims knew they were being assessed for crime-related distress and may have attributed existing behaviours to this. Nonetheless, this is an important first step.

The unique variable analysis did not detect scale overlap across behaviours (e.g. checking, avoidance), suggesting each contributed distinct information to the PRSBM and should be retained. However, it detected substantial overlap for the ‘frequency’/‘change’ scale pairs within each behaviour, suggesting they were contributing similar information. This may indicate item redundancy, suggesting the PRSBM may be improved by removing one set of scales (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Garrido and Golino2023). Alternatively, as our sample had already been identified as initially distressed after the crime, the PRSBM may have been accurately detecting that those who engaged in the behaviours were at the extreme end of the scales. In other words, older victims appear to have been reporting that they engaged in the behaviour ‘frequently’ and that this was a ‘change’ since the crime. Had their behaviours been pre-existing, they might have been expected to score ‘frequency’ highly but not ‘change’. Rituals was the only behaviour which, of those who engaged, tended to be only ‘a little more’ than before, and the qualitative data suggest these may have been pre-existing behaviours (e.g. faith practices, smoking). Taken together, these finding suggest that the behaviours reported across all domains of the PRSBM (apart from rituals) are in response to the crime and are perceived by older victims as impacting their daily routines. The next step is to test the PRSBM in different samples to see whether different patterns of reporting emerge.

Safety-seeking behaviours in older victims

Avoidance change was most strongly associated with continued distress in older victims after adjusting for confounding. Avoidance is a well-established maintenance factor for anxiety, depression, and PTSD (Akbari et al., Reference Akbari, Mohammad, Hosseini, Kraft and Levin2022; Ehlers and Clark, Reference Ehlers and Clark2000; Moorey, Reference Moorey2010). This finding is important because it supports the PRSBM’s ability to capture this construct. Crucially, avoidance must be attributed to a trauma to count towards a PTSD diagnosis (DSM-V-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2022) so finding avoidance ‘change’ was associated but not ‘frequency’ supports this. This expands evidence on safety-seeking behaviours after different crimes, as previous studies focused on student and working-age assault victims (Blakey et al., Reference Blakey, Kirby, McClure, Elbogen, Beckham, Watkins and Clapp2020; Dunmore et al., Reference Dunmore, Clark and Ehlers1999; Dunmore et al., Reference Dunmore, Clark and Ehlers2001).

Avoidance in older victims appeared restrictive and many reported avoiding leaving home entirely. Social isolation is associated with distress in older victims (Krause, Reference Krause1986; Reisig et al., Reference Reisig, Holtfreter and Turanovic2017). As older victims may be at increased risk of nursing home admission (Lachs et al., Reference Lachs, Bachman, Williams, Kossack, Bove and O’Leary2006), post-crime avoidance may also be a pathway for loss of independence. Two outliers from the residual analysis scored highly on avoidance change while scoring negative for continued distress; however, their symptoms may have ceased artificially by preventing anxiety increases (Helbig-Lang and Petermann, Reference Helbig-Lang and Petermann2010). While this might reflect healthy coping (Thwaites and Freeston, Reference Thwaites and Freeston2005), it seems unlikely given avoidance has consistently been associated with psychological sequelae (Akbari et al., Reference Akbari, Mohammad, Hosseini, Kraft and Levin2022).

Checking behaviours appeared consistent with safety-seeking but it was unclear from the qualitative data alone whether they were helpful or dysfunctional (Thwaites and Freeston, Reference Thwaites and Freeston2005). Checking on its own was associated with distress, suggesting behaviours may have been maladaptive, but the association was weaker when compared with avoidance. This may be because checking is considered a subtle form of avoidance (Sharpe et al., Reference Sharpe, Todd, Scott, Gatzounis, Menzies and Meulders2022). It can make anxiety tolerable, so the individual does not engage in complete avoidance, thereby providing opportunities for threat exposure and belief disconfirmation (Rachman et al., Reference Rachman, Radomsky and Shafran2008). For example, excessive lock checking may be unhelpful for older victims in isolation, but if it makes the difference between them leaving home or not, the overall impact may be less detrimental.

Hypervigilance on its own was similarly associated with distress but less than avoidance. Some older victims were avoidant and hypervigilant, such as the participant who spent all day monitoring home CCTV. Others were hypervigilant in places like the bank or public transport, suggesting it helped them not to avoid these situations. Studies suggest that hypervigilant individuals may be high or low in avoidance (Cisler and Koster, Reference Cisler and Koster2010; Kimble and Hyatt, Reference Kimble and Hyatt2019). Some older victims reported intentionally staying awake at night or sleeping next to weapons, suggesting they did not feel safe at home. Crimes like burglary may be especially distressing in older people as it is an invasion of somewhere that should feel secure and comforting (Delisi et al., Reference Delisi, Jones-Johnson, Johnson and Hochstetler2014). This absence of a safe place suggests they may be in constant distress (Golovchanova et al., Reference Golovchanova, Evans, Hellfeldt, Andershed and Boersma2023).

Positive and negative religious coping has previously been reported in older victims (Satchell et al., Reference Satchell, Dalrymple, Leavey and Serfaty2023), but rituals may also include superstition, and habits like smoking. These might be expected to be pre-existing behaviours. It is therefore interesting that the Change scale had even higher odds for continued distress than avoidance. However, the confidence intervals were wide, and the effect did not remain significant when adjusted for crime type. There may have been different patterns of reporting between those who always engaged in rituals and those that considered it a change since the crime, but we may have had insufficient power to detect this. It would be worthwhile replicating this with larger samples given its potentially substantial impact.

Neither reassurance-seeking nor rumination were associated with continued distress on either scale, in contrast with many studies reporting associations with anxious and depressive disorders (Brewin and Ehlers, Reference Brewin, Ehlers, Kahana and Wagnerin press; Halldorsson and Salkovskis, Reference Halldorsson and Salkovskis2023; Manrique-Millones et al., Reference Manrique-Millones, Garcia-Serna, Castillo-Blanco, Fernandez-Rios, Lizarzaburu-Aguinaga, Parihuaman-Quinde and Villarreal-Zegarra2023; Sharpe et al., Reference Sharpe, Todd, Scott, Gatzounis, Menzies and Meulders2022). Genuine associations may have been missed through inadequate power or construct validity, suggesting further testing in larger samples or refinement of the question may be needed.

Implications for policy and practice

Existing research in older victims of community crime has predominantly focused on fraud (Tripathi et al., Reference Tripathi, Robertson and Cooper2019), cybercrime (Havers et al., Reference Havers, Tripathi, Burton, Martin and Cooper2024a; Reference Havers, Tripathi, Burton, McManus and Cooper2024b) or violence (Muhammad et al., Reference Muhammad, Meher and Sekher2021), with relatively little on burglary or ‘high volume, low severity’ crimes like petty theft (Satchell et al., Reference Satchell, Craston, Drennan, Billings and Serfaty2022). We found a range of crimes psychologically impact older victims. This has important implications for criminal justice services, which under-serve older people (Brown and Gordon, Reference Brown and Gordon2022; HMICFRS, 2019). Police in the UK use the Cambridge Crime Harm Index to inform resource allocation (Sherman et al., Reference Sherman, Neyroud and Neyroud2016). This low-cost standardised metric weights how harmful each crime is relative to other crimes based on minimum sentencing guidelines (Van Ruitenburg and Ruiter, Reference Van Ruitenburg and Ruiter2023), which does not consider individual differences in coping in its assessment.

It is important that support is available for older victims, many of whom reported avoiding leaving home, as they appear at risk of losing independence. Maintaining autonomy in older adults is essential for health, quality of life, and preventing cognitive deterioration (Sanchez-Garcia et al., Reference Sanchez-Garcia, Garcia-Pena, Ramirez-Garcia, Moreno-Tamayo and Cantu-Quintanilla2019). It also helps reduce frailty and loneliness, both of which significantly increase risk of nursing home admission (Hoogendijk et al., Reference Hoogendijk, Afilalo, Ensrud, Kowal, Onder and Fried2019). As older victims have previously been found to be at increased risk (Lachs et al., Reference Lachs, Bachman, Williams, Kossack, Bove and O’Leary2006), this suggests a major preventable public health problem. Support is also needed for older victims hypervigilant within their homes, who may have minimal relief from their symptoms.

Disengaging from safety-seeking is a target of CBT, but it is debated whether all behaviours should be eliminated or whether some are beneficial (Rachman et al., Reference Rachman, Radomsky and Shafran2008). Whilst subtle behaviours like checking were individually associated with continued distress, they may be important for maintaining functioning in older victims. A phased approach targeting total avoidance of situations before other behaviours may reduce unintended consequences or attrition from therapy (Rachman et al., Reference Rachman, Radomsky and Shafran2008). Despite widely held concerns about the suitability of CBT in older adults (Frost et al., Reference Frost, Beattie, Bhanu, Walters and Ben-Shlomo2019), there is strong evidence supporting its efficacy (Werson et al., Reference Werson, Meiser-Stedman and Laidlaw2022).

Our PRSBM may aid therapeutic discussions around safety-seeking behaviours in older victims. We also purposely kept the wording general (e.g. ‘situation’ rather than ‘crime’) to widen its applicability to other incidents (e.g. bereavement, injury). Whilst further testing and replication of our findings in other populations is needed, our findings are proof-of-principle that the PRSBM has the potential to be useful in a range of clinical and research settings.

Strengths and limitations

We are the first to examine safety-seeking behaviours in older victims and to attempt a person-reported approach to measurement, with broad applicability. Our researcher-assisted PRSBM appears acceptable, comprehensive, person-centred, and able to capture idiosyncrasies and commonalities in behaviours. Inclusion of qualitative data also aided quantitative interpretation. Our findings on avoidance, checking and hypervigilance suggest good construct validity, and the overall compatibility of qualitative responses suggests good content validity, which is considered the most important patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) psychometric property (Food and Drug Administration, 2009).

The PRSBM’s limitations reflect wider challenges with evaluating PROMs as there are few sources of external validation (Lyon et al., Reference Lyon, Connors, Jensen-Doss, Landes, Lewis, McLeod, Rutt, Stanick and Weiner2017; Sales et al., Reference Sales, Neves, Alves and Ashworth2018). As behaviours were subjective, we could not assess convergent or discriminant validity, test–retest, or inter-rater reliability. We did not evaluate internal consistency as there was no a priori reason to suggest behaviours were correlated, which we considered a separate research question. However, we could have compared the PRSBM with clinician assessments of safety-seeking behaviours, which could be addressed in further research. As PROMs should be evaluated through accumulative evidence (Cappelleri et al., Reference Cappelleri, Jason Lundy and Hays2014; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Elsworth and Osborne2018), further development would be worthwhile.

Embedding our study within a trial collaborating with the police enabled us to recruit older victims within a defined time point. Previous studies have struggled with systematic identification of older victims and assessed the impact of crimes from many years previously (e.g. Acierno et al., Reference Acierno, Lawyer, Rheingold, Kilpatrick, Resnick and Saunders2007; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Reference Fredriksen-Goldsen, Cook-Daniels, Kim, Erosheva, Emlet, Hoy-Ellis, Goldsen and Muraco2014). However, we could not include sexual violence, which may be especially distressing in older victims (Bows, Reference Bows, Horvath and Brown2022), or unreported crimes. As 60–70% of crimes are unreported (Buil-Gil et al., Reference Buil-Gil, Medina and Shlomo2021), especially by victims from ethnic minorities or with complex care needs (Jones and Elliott, Reference Jones and Elliott2018; McCart et al., Reference McCart, Smith and Sawyer2010), our findings may not be representative of all older victims. Our London-based sample may also not be generalisable to older victims from elsewhere in the UK (Gordon and Brown, Reference Gordon, Brown, Newman and Gordon2023).

Cross-sectional designs do not permit inferences around causality or direction of the association. Combining the GAD-2/PHQ-2 also made it unclear whether associations were with depression, anxiety, or both. The screening tools were not diagnostic, although they strongly correlate with the GAD-7 and PHQ-9, which correspond with DSM-IV criteria for anxiety and depression (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006). We did not include PTSD because there is limited empirical data on which crimes may elicit traumatic stress responses in older people, who may differ from younger samples (Brewin et al., Reference Brewin, Andrews and Valentine2000; Jongedijk et al., Reference Jongedijk, van Vreeswijk, Knipscheer, Kleber and Boelen2022). We considered psychological distress more relevant as it encapsulates broader emotional responding after any community crime. Finally, although we adjusted for gender, age and crime type, we could have considered other variables such as previous mental health problems, whether participants lived alone, or whether the perpetrator had been arrested. These are all recommendations for future research.

Further development

A Delphi study on the safety-seeking behaviours currently included in the PRSBM and whether other items (e.g. carefulness) should be added is firstly recommended. Secondly, further testing in both older victims and other adverse event populations across diverse age groups and with larger sample sizes is needed. Factor analysis may help identify whether items can be combined or removed by assessing variable loading patterns. Comparison of the PRSBM with clinical assessment of safety-seeking behaviours may support its validity, and exploring whether different behaviours align to show high internal reliability would be worthwhile. Finally, recall bias could be addressed using alternative methods such as experience sampling methodology, which would facilitate self-evaluation of safety-seeking behaviours as they occur in daily life (Myin-Germeys et al., Reference Myin-Germeys, Kasanova, Vaessen, Vachon, Kirtley, Viechtbauer and Reininghaus2018; Oren-Yagoda et al., Reference Oren-Yagoda, Oren and Aderka2024).

Conclusions

Despite the prominence of safety-seeking behaviours to CBT, valid assessment tools have been lacking. Preliminary evaluation of the PRSBM suggests this is a promising solution. Older victims have been overlooked in safety-seeking behaviour research, yet our findings suggest that post-crime avoidance may have a profound impact on their subsequent functioning. Further research is needed to clarify what support may be helpful. The PRSBM may be a useful screening tool to help therapists target problematic safety-seeking behaviours in older victims and broader populations, and further development is recommended.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465825101197

Data availability statement

The data that support these findings are freely available from the UCL Research Data Repository. Quantitative dataset: https://doi.org/10.5522/04/25189082.v1; qualitative dataset: https://doi.org/10.5522/04/25188935.v1.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the VIP Trial Management Group for their feedback on the PRSBM including Vari Drennan, Gloria Laycock, Marta Buszewicz, Martin Blanchard, Anthony Kessel, and our PPI members. We are also thankful to Gemma Lewis, Vicki Vickerstaff and Rebecca Jones for providing additional statistical advice, and to the participants who pre-tested the PRSBM and took part in the current study.

Author contributions

Jessica Satchell: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (equal), Project administration (lead), Writing - original draft (lead), Writing - review & editing (lead); Gary Brown: Formal analysis (lead), Supervision (supporting), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Chris Brewin: Conceptualization (equal), Funding acquisition (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (supporting), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Jo Billings: Formal analysis (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (equal), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Gerry Leavey: Funding acquisition (supporting), Supervision (supporting), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Marc Antony Serfaty: Conceptualization (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Funding acquisition (lead), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Resources (lead), Supervision (lead), Writing - review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

The VIP Trial is funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (grant: 13/164/32). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The funders had no role other than financial support.

Competing interests

Author Dr Gary Brown was an associate editor for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy but was not involved in the decision whether to accept this manuscript for publication.

Ethical standards

Our study was approved by the University College London Research Ethics Committee (6960/001). We obtained informed consent for all participants and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.