Introduction

Taxation involves the institutionalisation of the revenue‐raising capacity of a modern state and, at the same time, it can motivate citizens to hold the government accountable and facilitate collective bargaining between the ruler and the ruled (Bräutigam Reference Bräutigam, Bräutigam, Fjeldstad and Moore2008; Levi Reference Levi1988; North Reference North1981). During the state‐building of Western democracies, the revenue production of emerging nation‐states was the focal point of such a bargaining process (Almond & Coleman Reference Almond and Coleman1960; Huntington Reference Huntington1968; Lipset Reference Lipset1959; Tilly Reference Tilly1992). As in the phrase ‘no taxation without representation’, which was a major, public cause of the American Revolution, the imposition of taxation served to increase awareness of the right to representation and promoted collective bargaining with rulers (Bates & Lien Reference Bates and Lien1985). Furthermore, it was a progressive taxation on income that improved state revenue production during early democratisation (Levi Reference Levi1988: Chapters 6 and 7; Lindert Reference Lindert2004; Scheve & Stasavage Reference Scheve and Stasavage2012, Reference Scheve and Stasavage2016; Webber & Wildavsky Reference Webber and Wildavsky1986).Footnote 1

However, contemporary democratisers since the third wave of democratisation have failed to imitate the hallmark measure of revenue of their early counterparts (Genschel & Seelkopf Reference Genschel and Seelkopf2016). Their main source of revenue is now a general tax on consumption (Carnahan Reference Carnahan2015). More specifically, unlike the first and second wave democracies,Footnote 2 the tendency is to adopt a newly innovated system of value‐added tax (VAT), which imposes a flat‐rate levy on general consumption and is thus, by nature, regressive taxation. VAT is also considered to be more effective than progressive income taxation because it can raise revenue without interfering with economic adjustment and development (Bird & Gendron Reference Bird and Gendron2007; Bräutigam Reference Bräutigam, Bräutigam, Fjeldstad and Moore2008; Corbacho et al. Reference Corbacho, Cibils and Lora2013; Ebrill et al. Reference Ebrill, Keen, Bodin and Summers2001; Gordon Reference Gordon2010b; Profeta & Scabrosetti Reference Profeta and Scabrosetti2010; Sandford Reference Sandford2000). Accordingly, most developing economies today prefer to adopt VAT without implementing effective income taxes.Footnote 3

Democratisers since the third wave have faced distinct circumstances compared to the regime transition of the early waves of democratisers (see also Freeman & Quinn Reference Freeman and Quinn2012). Developing countries today are in a globalised world where free trade and capital flight are the market norm, and modern regressive taxation is introduced as a means to adjust to globalised markets. International organisations representing the interests of advanced economies in the stability of developing economies have guided developing economies to implement VAT.Footnote 4 In this sense, modern tax systems in these countries have not evolved from the domestic politics of state revenue production, whereas the turbulence of domestic politics was key for early democratisation. In addition, VAT is an indirect taxation that is generally assumed to be ‘invisible’ and less likely to mobilise taxpayers for collective, domestic bargaining that emulates the process of early democratisation. The apparent lack of domestic contention over the introduction of VAT may suggest that taxation no longer constitutes an important process of political modernisation. This may also explain why the literature largely ignores the role of regressive taxation in regime transition.

In contrast, by revisiting state revenue production, we argue that taxation plays an important role in contemporary democratisation. Once implemented, taxation is inevitably implicated in the collective bargaining between the ruler and the ruled, and motivates the latter to hold the government accountable (Paler Reference Paler2013). VAT in the third wave democratisers is no exception. VAT tends to raise public awareness of tax burdens and politicise the government's tax imposition, which in turn promotes collective bargaining between the ruler and the ruled over fiscal contracts and democratic accountability. The politicisation tends to lead to collective action against ‘taxation without representation’ because contemporary autocrats often fail to provide public goods that are commensurate with the increased burdens of modern, regressive taxation (see also Ross Reference Ross2004, Reference Ross2012). Accordingly, we argue that VAT's coercive imposition and effective extraction tend to result in democratisation in the contemporary world (see also Moore Reference Moore2007).

Using time‐series cross‐national analyses, the present study examines the relevance of the tax–democratisation thesis in the third wave of democratisation. This new taxation–democratisation linkage did not emerge in a vacuum of socioeconomic circumstances. Other contextual and structural factors, such as economic development, trade liberalisation, natural resource endowment and an actual level of inequality may have affected it. To control for these factors, we employ a matching technique called ‘entropy‐balancing’. Although the taxation–democratisation linkage emerged in historical and geopolitical contexts in which many other events intervened, the entropy‐balancing technique enables us to extrapolate from circumstantial conditions. Our analysis demonstrates that the fundamental relationship between taxation and democratisation survives in the contemporary world, even when controlling for factors that may affect both VAT introduction and regime transition. Our analysis also examines and provides evidence for one implication of the argument: collective actions such as riots can induce democratisation after a country introduces VAT through the politicisation of the tax burden.

We make two main contributions to the literature. First, we provide descriptive narratives of tax development in the third wave democratisers. We demonstrate that third wave democratisers historically have distinct tax development; therefore, we need to examine the tax–democratisation linkage in the third wave democratisers separately from the ones in the first and second waves. The discussion also highlights some misperceptions about contemporary taxation. In particular, we clarify that, unlike their predecessors, third wave democratisers tend not to employ effective income taxes and often rely heavily on VAT for their state revenue. Because the literature assumes that progressive income taxation still plays a role in democratisation, clarifying the distinctive tax development in the third wave democratisers should contribute to studies on contemporary democratisation.

The article's second contribution is that, building on a small number of exceptional studies of regressive taxation and democracies (Baskaran Reference Baskaran2014; Timmons Reference Timmons2010a), we explore an under‐examined process of how taxation leads to contemporary democratisation. Specifically, we investigate how the politicisation of VAT's tax burden affects the likelihood of democratisation in the contemporary world.

The view that democratisation can be explained by the level of inequality in a society (Acemoglu & Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006; Boix Reference Boix2003) and rent from natural resources (Aslaksen Reference Aslaksen2010; Beblawi Reference Beblawi and Luciani1990; Herb Reference Herb2005; Jensen & Wantchekon Reference Jensen and Wantchekon2004; Mahdavy Reference Mahdavy1970; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2011; Papaioannou & Siourounis Reference Papaioannou and Siourounis2008; Ramsay Reference Ramsay2011; Ross Reference Ross2001, Reference Ross2012) dominates recent literature. Shedding new light on taxation qualifies these explanations, which pay little attention to the role of taxation in political modernisation. In this sense, this article brings taxation back into the third wave of democratisation and demonstrates that the fundamental premise of the taxation–democratisation thesis has travelled from early to contemporary democratisation.

In the remainder of this article, we first describe how VAT evolved historically and why developing countries adopted it as their main revenue source. The discussion should clarify our contribution and the historical contexts for our argument. We then propose our main argument that regressive taxation leads to democratisation through the politicisation of tax burdens. In the empirical sections, we first introduce our research design and cross‐national times‐series dataset, and then present the main findings. Finally, we discuss the implications of our results for the existing literature and conclude with a summary.

Bringing taxation back into contemporary democratisation

VAT is specific to the third wave democratisation

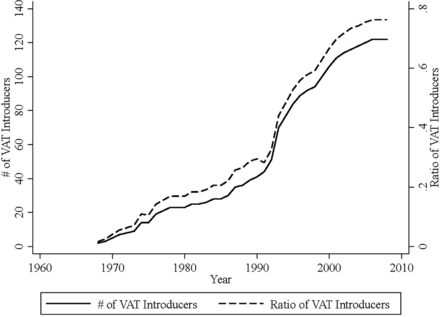

A total of 122 developed and developing countries had introduced VAT by 2006. With its increased diffusion (Figure 1), VAT has attracted scholarly attention regarding its relationship with democracies. Timmons (Reference Timmons2010a) finds that both mature and young democracies tend to raise revenue from regressive taxes on consumption (i.e., VAT) rather than from progressive income taxation and questions whether democracies thus decrease inequality. Baskaran (Reference Baskaran2014) demonstrates that VAT is an important tool to increase government revenue effectively and is more likely found in democracies.Footnote 5 Together, these studies indirectly question the prevailing focus on progressive income taxation in the democratisation literature and shed new light on the relationship between VAT and democracies.

Figure 1. Trends in VAT between 1960 and 2007.

Source: Data are from Bird and Gendron (Reference Bird and Gendron2007).

Building on the growing interest in the relationship between regressive taxation and regime type, the present study explores the effect of VAT on regime transition by distinguishing early democratisers from contemporary ones.Footnote 6 Paying close attention to the historical development of VAT as detailed in the following section, we show that the VAT–democratisation linkage is unique to third wave democratisers. Because the VAT system was not innovated until the 1950s (Sandford Reference Sandford2000; Kato Reference Kato2003), technically only the democratisers since the third wave have had an opportunity to introduce VAT before democratisation. Thus, they constitute appropriate cases for examining the effect of VAT on democratisation. By contrast, their predecessors had no choice but to implement VAT after democratic consolidation (see below for more discussion). We thus focus on the third wave countries and examine how the introduction of VAT affects democratisation.

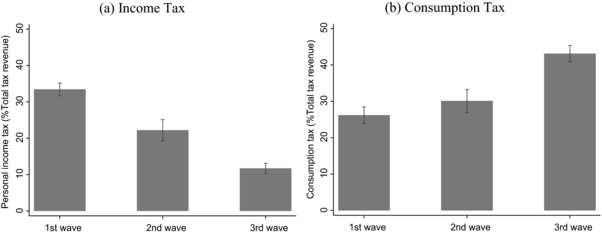

It is important to note that these different tax developments across different waves of democratisation tend to result in variation in revenue reliance (as a proportion of total tax revenue) on income and consumption taxes (Figure 2).Footnote 7 The first wave democratisers still rely heavily on income taxes. The second wave democratisers follow those trends, but, to some extent, they also extract their revenue from consumption taxes.Footnote 8 By contrast, third wave democratisers do not rely much on income taxes for their tax revenue, but instead rely heavily on consumption taxes because they adopted VAT rather than income taxes as a major form of taxation.

Figure 2. Revenue reliance on income and consumption taxes by different waves of democratisation in 2014.

Notes: The figure displays the mean value of revenue production type as a percentage of total government revenue by three different waves as of 2014. ‘3rd wave’ countries include a mix of democratic and autocratic countries. We use Huntington (Reference Huntington1991) for the definition of the waves. The error bars indicate standard errors for each value. The income and consumption tax data come from the OECD Revenue Statistics (https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=REV).

For third wave countries, VAT is thus a major form of taxation that finances the modern state before and/or from the outset of democratisation. Roughly 75 per cent of the sub‐Saharan African and Asia‐Pacific countries, nearly half of the North African and Middle East countries, and one‐third of the small island countries in the Caribbean and the Pacific have introduced VAT (Bird & Gendron Reference Bird and Gendron2007: 17). Unlike their predecessors, third wave democracies have failed to institutionalise income taxes during democratisation. Existing theories of democratisation tend to focus on the distributional consequences of domestic conflicts – namely the expected reduction in inequality to which tax progressivity would contribute after a transition (Boix Reference Boix2003; Acemoglu & Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006). The assumption is, however, more plausible for early democratisers than for third wave ones, and we observe the general tendency to rely more on taxes on consumption than on income taxes in the third wave countries.Footnote 9 Consequently, we claim that it is critical to study the third wave countries separately from the first and second wave countries when one examines the effect of taxation – particularly VAT – on contemporary democratisation.

Why do the third wave countries adopt VAT as a major form of taxation for modernisation?

As mentioned above, developing countries today tend to introduce and rely on VAT for their state revenue. Why then do contemporary democratisers fail to rely on income tax revenue that had once financed the state‐building of early democratisers? Before introducing our argument about the contemporary linkage between taxation and democratisation, this section traces the development of taxation in the contemporary world and clarifies circumstantial conditions that facilitated the adoption of VAT in autocratic states. The historical overview in turn illustrates that developing countries introduce VAT for economic reasons that are largely independent of transition in the political regime. This allows us to focus on how VAT affects democratisation after its introduction. First, it is important to note that the advantage of being late developers permits democratising countries to skip the trials and tribulations of their predecessors to raise state revenue, which leads to collective bargaining between the ruler and the ruled.Footnote 10 In the 1970s, when the third wave countries embarked on regime transition, VAT had already been devised and implemented in developed economies.

Furthermore, in the contemporary world where free trade and capital flight are the norm, tax policy is not only a domestic policy but also a means to comply with trade and financial openness in globalised markets.Footnote 11 Compared with income taxes, VAT is neutral to economic activities without interfering with development and is thus a suitable revenue‐raising measure for developing economies that need to rationalise and stabilise their domestic, economic systems in the globalised economy (Bird & Gendron Reference Bird and Gendron2007; Bräutigam Reference Bräutigam, Bräutigam, Fjeldstad and Moore2008; Corbacho et al. Reference Corbacho, Cibils and Lora2013; Ebrill et al. Reference Ebrill, Keen, Bodin and Summers2001; Gordon Reference Gordon2010b; Profeta & Scabrosetti Reference Profeta and Scabrosetti2010; Sandford Reference Sandford2000).Footnote 12 Consequently, developing countries tend to introduce VAT rather than income tax as a major revenue source because they need to implement a modern form of taxation that helps them to adjust to global markets and develop at the same time.Footnote 13

The tax literature (Bird & Gendron Reference Bird and Gendron2007; Emran & Stiglitz Reference Emran and Stiglitz2005; Tanzi & Zee Reference Tanzi and Zee2000) agrees that the pressure for economic liberalisation facilitates the diffusion of VAT, which subsequently contributes to increasing the total government revenue in developing countries (Aizenman & Jinjarak Reference Aizenman and Jinjarak2009; Bird & Gendron Reference Bird and Gendron2006; Keen & Lockwood Reference Keen and Lockwood2010; Rakner & Gloppen Reference Rakner, Gloppen, Walle, Ball and Ramachandran2003).Footnote 14 VAT constituted a critical part of revenue reform proposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Crivelli & Gupta Reference Crivelli and Gupta2016), and the Fiscal Affairs Department of the IMF was the main agent of the adoption of VAT (Bird & Gendron Reference Bird and Gendron2007: 16; Keen Reference Keen2009: 160). Experts from the World Bank and regional banks also facilitated its adoption and implementation.Footnote 15 Because of advice from international organisations and foreign experts, developing countries could introduce a consistent and standard model of VAT (Bird & Gendron Reference Bird and Gendron2006, Reference Bird and Gendron2007; Tanzi & Zee Reference Tanzi and Zee2000).Footnote 16

In a nutshell, the historical background and tax literature indicate that governments in the third wave countries have failed to implement income taxes because VAT, which has been around since the 1960s, allows them to raise revenue more effectively in a globalised world. The development of taxation clarifies the historical (albeit not necessarily causal) sequence that many countries in the third wave first introduced VAT for economic considerations followed by the experience of democratic transition.Footnote 17 This brings us to our main question about the relationship between taxation and the third wave of democratisation: Is the introduction of VAT more likely to lead to democratic transition and if so, how?

Argument

During the first wave of democratisation, the bargaining over tax revenue production shaped the evolution of modern states that were often required to survive external wars and recurrent financial stresses (Tilly Reference Tilly1975). At the same time, taxation induced collective action, as demonstrated in protests against the autocratic extraction of tax revenue (Levi Reference Levi1988). Based on the experience of early democratisation, Bates and Lien (Reference Bates and Lien1985) proposed a model of collective bargaining between citizens and a revenue‐seeking ruler over the new burden and allocation of public goods.

As mentioned above, unlike the introduction of taxation for the early democratisers, the introduction of VAT was driven by external factors. Yet, contemporary democratisers could not escape the collective bargaining over taxation that their early counterparts experienced. In this sense, VAT is not different from other taxation once rulers impose it as a levy on citizens because it generally motivates citizens to monitor and hold the government accountable as well as leading to increased collective bargaining between leaders and citizens (Bates & Lien Reference Bates and Lien1985; Levi Reference Levi1988). Experimental evidence also confirms that taxation motivates citizens politically and induces collective bargaining with political leaders (Martin Reference Martin2016; Paler Reference Paler2013). Accordingly, the state's extraction of revenue from society through VAT is also expected to contribute to citizens’ increased awareness of the distributional consequences of taxation and motivate them to monitor and hold the government accountable (Bird & Gendron Reference Bird and Gendron2007: 76; Mahon Reference Mahon and Blofield2011).Footnote 18

We thus argue that the introduction of VAT, although externally driven as already demonstrated, results in the politicisation of the government's tax imposition. In this regard, we highlight several unique features of VAT to understand why it raises awareness of tax imposition and fuels political opposition from citizens as well as interest groups. First, VATFootnote 19 makes industries and enterprises comply with new, tax‐filing obligations and government regulations about tax enforcement and compliance. Although industries and enterprises can transfer the tax burden to consumers, they still have to fulfill additional and complicated record‐keeping obligations, which incur significant costs on their tax returns (Pomeranz Reference Pomeranz2015). The tax system thus tends to stir up opposition from trade organisations.Footnote 20

Second, the flat‐rate levy of VAT also affects all of society because of increasing prices (Kosonen Reference Kosonen2015) that threaten the livelihoods of the poor and are counter to the interests of the household.Footnote 21

Third, the regressive nature of the VAT further increases the opposition of citizens to a newly imposed burden. Unlike progressive income taxation, by design, the flat‐rate levy of VAT does not have a direct effect on reducing income inequality; rather, because it imposes the same tax rate on the rich and poor, it is often regarded as a regressive burden with grievances. These effects can easily increase citizens’ awareness of tax burdens and politicise the lack of accountability between citizens and the government. They can lead to collective bargaining and possibly violent protest actions.

In fact, the adoption of VAT ‘considerably increases the potential for collective action’ (Moore Reference Moore2004: 312) and ‘has sometimes led to demonstrations and violent confrontations’ (Anuradha & Ayee Reference Anuradha, Ayee, Bräutigam, Fjeldstad and Moore2008: 189). Several case studies provide firsthand evidence that the introduction and/or the attempt to introduce VAT has led to both violent and non‐violent collective action ranging from street demonstrations and protests to riots in countries such as Ghana (Moore Reference Moore2004; Osei Reference Osei2000; Rakner & Gloppen Reference Rakner, Gloppen, Walle, Ball and Ramachandran2003; Terkper Reference Terkper1996), Venezuela (Kornblith Reference Kornblith, Canache and Kulisheck1998: 5), the Dominican Republic,Footnote 22 Kenya (Prichard Reference Prichard2015: Chapter 6), Bolivia (Bird & Gendron Reference Bird and Gendron2007: 24) and Mexico (Bird & Gendron Reference Bird and Gendron2007: 24).

The case of Ghana illustrates how collective action associated with VAT – sometimes called ‘VAT riots’ – can occur (Moore Reference Moore2004).Footnote 23 The government of Ghana introduced a 17 per cent VAT for the first time in 1995 amid the nation's political development. This development resulted in democratic transition in 2000 when a peaceful change of power occurred.Footnote 24 But the introduction of the VAT provoked several demonstrations and riots within two months of it becoming effective. The riot in the capital of Accra was especially brutal and resulted in several deaths and approximately 40 injuries.Footnote 25 A series of collective actions eventually forced the government to withdraw the newly introduced VAT system. The opposition to VAT in Ghana arose because of the increased costs of the tax returns, grievances against commodity price increases and VAT's regressivity. These effects can typically be observed in similar protests in other countries that have introduced VAT (e.g., see Terkper Reference Terkper1996: 1812). The Ghanaian government then attempted to make the VAT system more politically acceptable to the public, for example, by introducing compensatory measures demanded by taxpayers as well as reducing the costs of tax filing, with the result that the VAT system was eventually restored in 1998.Footnote 26 In this sense, taxpayers in Ghana successfully mobilised when VAT was introduced to make their voices heard. The government responded to the apprehension and opposition of the taxpayers with policy compromises and a public education campaign, which made VAT more acceptable to consumers and organised interests.Footnote 27 Overall, the VAT riots in Ghana indicate that taxation, although adopted based on technical advice from foreign specialists, cannot be insulated from domestic, political bargaining between citizens and the government.

The empirical observation suggests that the imposition of VAT provides an opportunity to increase public awareness of financial expropriation by autocratic states, thereby leading to collective bargaining and actions with rulers for more democratic accountability. Once citizens recognise the exploitation of the state, they are less likely to tolerate the lack of accountability of an autocratic government unless rulers offer them a representative voice in policy making (Bates & Lien Reference Bates and Lien1985; Levi Reference Levi1988; Ross Reference Ross2004).Footnote 28

In the face of collective action elites are unlikely to remove VAT and may accept democratisation relatively easily because the flat‐rate levy does not result in radical redistribution after democratisation. Effective extraction of revenue generally increases the elites’ resistance to democratisation, but, because of the regressive nature of taxation, from the perspectives of the economic cost‐benefit analysis of elites, VAT involves relatively more positive implications for democratisation than income taxes (Albertus & Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2014; see also Boix Reference Boix2003; Acemoglu & Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006). Consequently, with VAT introduction (compared to income taxes), the relative value of autocracy vis‐à‐vis democracy is expected to decrease for elites as well as citizens.Footnote 29

With the complex mechanisms of the VAT–democratisation linkage in mind, we derive two observable implications of our argument: first, the introduction of VAT increases the likelihood of democracy; and second, riots are more likely to lead to democratisation in countries with VAT than their counterparts without it. In the next section, we examine empirically our argument about a tax–democratisation linkage in the contemporary world, particularly the two observable implications stated above.

Quantitative analysis

Data and variables

To explore the tax–democratization linkage that is specific to the contemporary world, we focus on 143 developing countries during the period 1960–2007, excluding countries in the first and second waves of democratisation that introduced VAT after democratic consolidation.Footnote 30 To estimate the effect of VAT on the likelihood of democracy, the analysis employs the regime‐type variable Democracy, based on Cheibub et al. (Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010), which is coded 1 if a country is a democracy and 0 otherwise.Footnote 31 In addition to the binary variable, we use Polity scores vis‐à‐vis these binary categorisations in some of the specifications. The Polity variable is constructed by normalising Polity scores to run from 0 to 1.

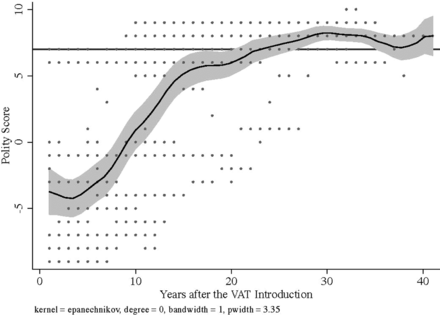

The analysis employs three different measures for VAT as our main independent variable. The level of tax revenue may be an appropriate measure to examine the effect of VAT because it can capture variation in tax burdens. However, consistent and comprehensive data on revenue from VAT are not available among the third wave countries. We thus construct variables other than the revenue one. Because the tax literature concurs that the introduction and continued implementation of VAT generally ensures that its introducers successfully impose levies on citizens and extract increasing revenues (Bird & Gendron Reference Bird and Gendron2007; Gillis Reference Gillis1989; Gordon Reference Gordon2010a),Footnote 32 the variables that represent the presence and duration of the VAT system are also appropriate for examining the role of taxation in democratisation. A uniform effect of VAT introduction is embodied in the VAT introduction variable, which is coded 1 in the subsequent years after the introduction of VAT and 0 otherwise. The ln(VAT cumulative effect) variable is calculated by taking the logarithm of the number of years after the introduction of VAT for each countryFootnote 33 and represents the potential nonlinear effect (see also Figure 3).Footnote 34 Finally, with the above‐mentioned caveat in mind, we use the VAT (%GDP) variable to represent the level of revenue by using the data on consumption taxes as a robustness check.Footnote 35 To examine the effects of other tax variables on democracy, the analysis also includes the IMF income tax and IMF tax revenue variables in some specifications, which represent general revenues from income tax and taxation, respectively, as proportions of gross domestic product (GDP).Footnote 36

Figure 3. Trends in polity score since the introduction of VAT: Kernel‐weighted local polynomial smoothing.

Notes: The figure displays the results of a local polynomial regression of VAT introduction on Polity score (bandwidth = 1.0) with 95per cent upper and lower bands. Each dot represents a country's Polity score at a given year. Taxation data derive from Bird and Gendron (Reference Bird and Gendron2007), and regime data derive from the Polity IV project.

Although our analysis focuses on VAT, we argue that neither its introduction nor its mere presence automatically lead to democratisation without political processes. Instead, we argue that VAT is more likely to result in democratisation when the imposition of the new levy is politicised and increases the possibility of collective action. To take these effects into consideration, we should employ direct measures capturing politicization and collective action against VAT. However, there are no available data to represent the explicit outbreak of collective action against VAT or implicitly associated with it. Thus, to capture VAT's politicisation processes, our quantitative analysis compares the effects of collective action on democratisation with and without the presence of VAT.Footnote 37 We expect that because VAT increases grievances among the public and motivates citizens politically, collective action is more likely to increase the likelihood of democracy with the VAT than without it. Because as already demonstrated, outbreaks of riots have often been observed with the introduction of VAT, for specific measures of collective action we use the widely employed data on riots as a proxy and create a Riot variable which takes the logarithm of the number of riots.Footnote 38 We then construct an interaction term between collective action and our VAT variables and examine the process of politicisation that intervenes in the VAT–democratisation linkage.

The analysis also includes factors that the existing literature considers to facilitate contemporary democratisation and examine whether taxation has its own role in contemporary democratisation after controlling for these other correlates. The Resource variable represents a country's resource rent, which takes the logarithm of the division of the value of a country's annual oil and natural gas production by its population.Footnote 39 The Capital share variable is used to examine the impact of (in‐)equality on democratisation, which estimates the capital share by the proportion of the added value that accrues to capital owners.Footnote 40 Other control variables are: economic growth (Growth); the logarithm of GDP per capita (ln(GDP per capita)); trade openness (Trade openness);Footnote 41 the logarithm of length under autocracy (ln(Years in autocracy)); the mean polity scores of neighbouring countries within 1,000 km of the target country's capital (Polity diffusion effect); and a time‐variant proportion of Muslim population (Islam).Footnote 42 To control for temporal dependence that may affect our inferences, we follow Carter and Signorino's (Reference Carter and Signorino2010) suggestion and include a third order, polynomial time counter, Time, Time 2 and Time 3, which is considered more appropriate than, for example, time dummy variables that may raise problems of inefficiency and/or data separation in employing a binary‐dependent variable. All the independent variables except the time counter are lagged one year. Table B in the Online Appendix shows summary statistics for the variables.

Models

The analysis employs time‐series, cross‐sectional logit regression over a binary categorisation of regimes, Democracy, with random and fixed effect models.Footnote 43 Our main specification model is as follows:

where i denotes each country and t denotes the time period; Democracyit indicates whether a country is a democracy; VATit−1 is our proxy of VAT; Xit−1 is a vector of control variables; μit−1 is between‐country error term; and εit−1 is within‐country error term.

In addition to the baseline model, we employ an entropy‐balancing method to solve a selection bias problem in observational studies (Hainmueller Reference Hainmueller2012). For example, it is possible that countries with abundant natural resources tend not to introduce VAT because the resources allow them to survive without tax revenues. And because natural resources are negatively correlated with democratisation, we may over‐estimate the effect of VAT on the likelihood of democracy. Entropy‐balancing enables one to adjust the imbalances in such observable factors that may intervene in the tax–democratisation linkage and thus to examine it without the interference of these covariant variables.Footnote 44 Specifically, we use the VAT introduction variable as a binary treatment variable and re‐weight based on covariates, so that a treatment group (countries that introduced VAT) and a control group (countries that did not introduce VAT) share the same mean.Footnote 45 The entropy‐balancing analysis also employs the Riot variable and an interaction term between the VAT introduction and Riot variables.

Results

Data exploration

Before we present analyses that control for other factors, an initial exploration provides the first piece of evidence, although preliminary, about the contemporary, taxation–democratisation linkage.Footnote 46 On average, countries that introduced VAT have a Polity score of 5.53 points higher than those that did not introduce it. The positive relationship also holds among VAT introducers, where an increase by 6.61 points on average is observed in the Polity score after the introduction of VAT. This implies that countries are more likely to experience a regime transition toward democracy with VAT than without it. We also show the simple time frame of the positive effect of the VAT on democratisation by a Kernel‐weighted, local polynomial fitting (bandwidth = 1) over Polity scores and the number of years after the VAT introduction (Figure 3). Among 15 developing countries that institutionalised VAT more than 25 years ago, the regimes generally began to diverge from an autocracy towards a transition to a democracy (defined here as an increase in their Polity score above six) after approximately eight years. The democratisation trend continued until nearly 30 years after the introduction of VAT, and every country except one achieved democratic consolidation after 30 years.Footnote 47

Identifying the linkage between taxation and contemporary democratisation

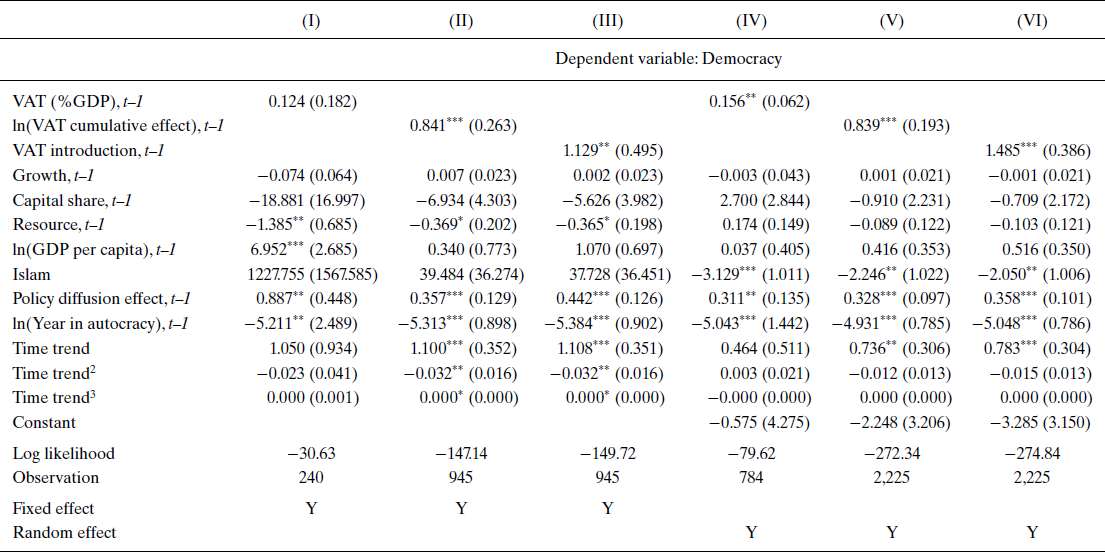

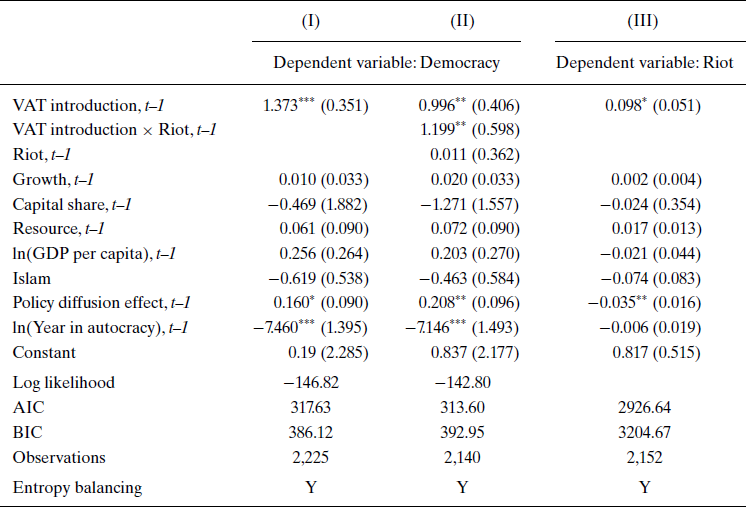

Table 1 presents our baseline analyses where three specifications with different VAT‐related variables (VAT (%GDP), ln(VAT cumulative effect) and VAT introduction) are replicated using fixed effect and random effect models, respectively.Footnote 48

Table 1. Baseline analyses between 1960 and 2007

Note: *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Overall, the analyses confirm both the uniform and cumulative effects of the presence of taxation on democratisation.Footnote 49 Country‐fixed effect models lose significance with the VAT (%GDP) variable (model I),Footnote 50 but the ln(VAT cumulative effect) and VAT introduction variables remain significant at the 5per cent level (models II and III, respectively). This suggests that the findings are not an artifact of omitted variables derived from time‐invariant, unobserved heterogeneity across countries. Further, random effect models find that all the VAT‐related variables are significant with the expected direction (models IV, V and VI). From this, we conclude that two dependent variables of our interest, ln(VAT cumulative effect) and VAT introduction, have positive and statistically significant impacts on the likelihood of democracy.Footnote 51 In substantive terms, we calculate the simulated probability of democracy by drawing samples from the variance‐covariance matrix of the estimates of model V. The calculation suggests that while holding all other covariates at sample means, if the number of years since a country has introduced the VAT increases from ten to twenty years, the probability of democracy in a given year for an observation increases by about 26.6 per cent.

Among factors that are considered important in the existing literature on democratisation, the Resource variable shows significant results in fixed effect models, but it is insignificant in random effect models. The Islam variable, which is correlated with oil countries in the Middle East (Ross Reference Ross2001, Reference Ross2012), is negatively associated with democracy in random effect models. The Capital share variable does not show a significant result in any model, and this is consistent with the no‐findings in the recent literature (Haggard & Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2012; Houle Reference Houle2009). The Polity diffusion effect variable shows a significant, positive result across all the models, indicating a domino effect of democracy. Finally, the ln(Year in autocracy) variable shows a negative result across all the models.

Examination of other tax variables and contextual variables

As a robustness check, we next examine alternative specifications with additional variables that may mitigate the effect of the VAT on democracy. First, we replicate the analysis of Table 1 by including income tax and total tax revenue as a proportion of GDP (see Table F in the Online Appendix).Footnote 52 In particular, because higher total tax revenue enables a state to finance specific social programmes such as education and welfare, this increase in the tax revenue in general may contribute to democratisation. However, although the VAT‐related variables remain positive and significant at the 5 per cent level, no significant result is found for other tax‐related variables, including the total tax revenue variable.

We also examine factors that represent the contexts of the third wave democratisation that may affect a relationship between VAT and democratisation – that is, the fall of communist governments in Europe, economic liberalisation and economic development. Because the historical contingency of the demise of a communist regime accompanied both the transition to democracy and the adoption of VAT (for participation in the EU), the inclusion of these countries may over‐estimate the effect of VAT. To deal with the problem, we dropped the Eastern European countries and conducted an analysis using a truncated sample. However, the VAT variables remain positive and significant at the 5 per cent level (see Table G in the Online Appendix). The taxation–democratisation linkage may also be explained by economic liberalisation in globalised markets, not specifically by VAT. As already discussed, VAT was sometimes introduced as a part of economic liberalisation reform. We examine this possibility using the Trade openness variable that captures the effect of liberalisation reform. However, the VAT variables remain positive and significant at the 1 per cent level, even when we include the Trade openness variable whose coefficients are insignificant (Table H in the Online Appendix). Finally, we examine the effect of economic development that modernisation theory once considered important in Western democratisation (Huntington Reference Huntington1968; Lipset Reference Lipset1959) but has revealed mixed empirical results in recent studies (Boix & Stokes Reference Boix and Stokes2003; Przeworski et al. Reference Przeworski, Alvarez, Cheibub and Limongi2000). In the specification of the model with an interaction term between VAT and GDP per capita, we found no significant effect of their interaction and thus confirm that the effect of VAT is independent of economic development (Table I in the Online Appendix).Footnote 53 Overall, the results confirm that at least these factors do not interfere with the relationship between VAT and democracy, providing more support for our argument.

Entropy‐balancing analysis

Using an entropy‐balancing method, we next control for co‐varied differences that exist between countries with and without VAT. We adjust the imbalances in all the observable variables that may plausibly explain the relationship between VAT and the likelihood of democracy. We confirm that the differences in the means after entropy‐balancing are weighed between countries with and without VAT (Figure A in the Online Appendix).

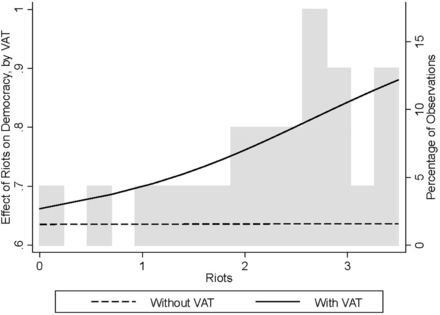

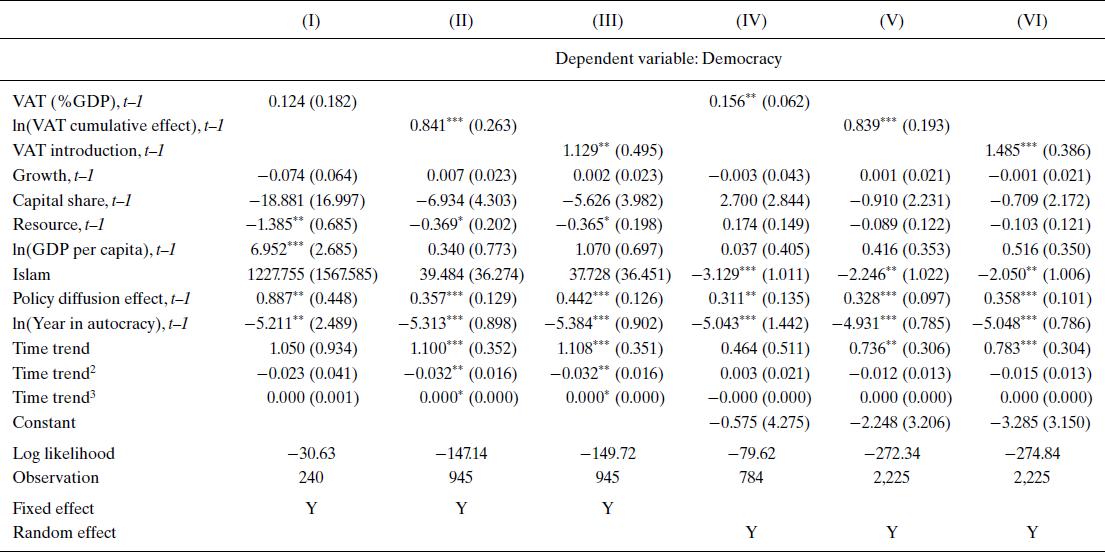

Table 2 reports the full results. The VAT introduction variable remains statistically significant in model I which replicates model VI of Table 1 with the entropy‐balancing method.Footnote 54 In model II, the interaction effect of VAT introduction and the Riot variable is statistically significant when the effect of VAT introduction is also significant. Because the Riot variable is insignificant, the result suggests that riots contribute to the likelihood of democracy only in countries that introduce VAT.

Table 2. Analyses on the linkage between the VAT riot and democracy between 1960 and 2007

Note: *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

To supplement the regression analysis to interpret the interaction effects (Brambor et al. Reference Brambor, Clark and Golder2006), the marginal effects of riots (based on model II of Table 2) are plotted against the VAT introduction variable. Figure 4 shows that the effect of riots on the probability of democracy is conditional on the existence of VAT. More specifically, riots have a positive impact on democracy only with the presence of VAT. The results with the interaction variable themselves do not show that VAT induces riots. However, when combined with the qualitative information (Bond Reference Bond2011; Moore Reference Moore2004; Osei Reference Osei2000; Patel & McMichael Reference Patel and McMichael2009; Rakner & Gloppen Reference Rakner, Gloppen, Walle, Ball and Ramachandran2003; Walton & Ragin Reference Walton and Ragin1990; Walton & Seddon Reference Walton and Seddon1994), they suggest that VAT introduction tends to result in a perceived tax burden and facilitates collective action, such as riots, and increases the likelihood of democracy. To provide further evidence for this point, we report the result of a model with riots as dependent variable in model III. The analysis confirms that riots are more likely to occur in countries with VAT than without. Taken together, the results corroborate our argument about the linkage between VAT and contemporary democratisation.

Figure 4. Marginal effects of riots, by VAT introduction.

Notes: The figure is based on model II of Table 2. The shaded bars indicate the number of observations.

Bringing taxation back into contemporary democratisation

Finally, we highlight our argument about the contemporary taxation–democratisation linkage by demonstrating how it is related to the recent literature. In particular, we believe our finding contributes to the discussion about other correlates of democratisation (i.e., inequality and resource rent) that dominate the recent literature.

Boix (Reference Boix2003) first proposes a negative, linear relationship between inequality and democratisation, whereas an opposing view claims an inverted U‐shaped relationship – the adverse effect of either low or high inequality on democratisation, but the positive effect on it of intermediate levels of inequality (Acemoglu & Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006). These apparently contradictory views share an implicit assumption that elites fear redistributive equality under democracy ex ante. The median voter model posits that if the poor were permitted to vote, they would support policies that would transfer wealth from the rich to them (Meltzer & Richard Reference Meltzer and Richard1981). Thus, elites who are enjoying a high level of wealth under an autocratic system tend to repress the demands of citizens for representation.

However, recent studies do not necessarily endorse the role of distributive conflict over equality in democratisation (Timmons Reference Timmons2010a, Reference Timmons2010b). Houle (Reference Houle2009) confirms the negative effect of the level of inequality on consolidation but not on democratisation per se. The recent literature also goes beyond the conventional explanation that regards the evolution of income taxation as an equalisation process during democratisation. Scheve and Stasavage (Reference Scheve and Stasavage2016) argue that governments tax the rich not only because of high and/or low inequality, but also because they want to compensate the bulk of the people for their unequal sacrifices in warfare. Haggard and Kaufman (Reference Haggard and Kaufman2016) raise doubts about an attempt to apply an overarching theory of equality to different waves of democratisation. A cross‐national comparison in the third wave countries contends that democratisation more likely depends on ‘incentives and capacities for collective action that are not, in fact, given by the level of inequality’ (Haggard & Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2012: 513) between elites and the masses.

More importantly, Ansell and Samuels (Reference Ansell and Samuels2014) shift the focal point of democratisation from mass protests for equal redistribution to resistance to the financial exploitation of the autocratic state by the enfranchised social classes. In this regard, they revisit the state control of revenue production and financial appropriation in the early democratisation literature (Almond & Coleman Reference Almond and Coleman1960; Huntington Reference Huntington1968; Levi Reference Levi1988; Lipset Reference Lipset1959; North Reference North1981; Tilly Reference Tilly1992).Footnote 55 Third wave democratisation is no exception. Ansell and Samuels (Reference Ansell and Samuels2014) argue that autocratic extraction of revenue resulted in resistance for the right of property protection and, thus, the demand for representation. Whereas the previous literature did not directly examine the state's extraction of tax revenue, our study factors in VAT as a modern form of taxation for contemporary democratisers and provides a further exploration for this renewed interest in the financial expropriation of the state.

The availability of non‐tax revenue in the contemporary world may cast doubt on the importance of tax revenue production in contemporary democratisation. Many contemporary, autocratic governments benefit from foreign investments and technological aid to raise non‐tax revenue and exploit rents. The rentier states can afford to finance public spending with resource rents without taxing their citizens (Beblawi Reference Beblawi and Luciani1990; Herb Reference Herb2005; Mahdavy Reference Mahdavy1970). An endowment of natural resources is believed to impede democratisation in developing countries (Andersen & Ross Reference Andersen and Ross2014; Aslaksen Reference Aslaksen2010; Jensen & Wantchekon Reference Jensen and Wantchekon2004; Mitchell Reference Mitchell2011; Papaioannou & Siourounis Reference Papaioannou and Siourounis2008; Ramsay Reference Ramsay2011; Ross Reference Ross2001, Reference Ross2012; Tanaka Reference Tanaka2013).Footnote 56

To counter this straightforward ‘resource‐curse’ thesis, the recent literature considers the effects of resource wealth based on circumstantial conditions. For example, resources may be a blessing for democratisation, conditional on income inequality (Haber & Menaldo Reference Haber and Menaldo2011). Depending on the relative importance of natural resources, resource wealth can also support both authoritarianism and democratisation; it promotes democratisation in large, non‐resource‐dependent economies where elites may use revenue from rents to redistribute income without taxation (Dunning Reference Dunning2008: 100–106).

Our study serves to enhance these arguments about the conditional effects of resource wealth by refuting the trade‐off between non‐tax and tax revenues that the existing literature assumes implicitly. Whereas resource wealth enables rulers to avoid taxation and contributes to stabilising autocracies (Morrison Reference Morrison2014),Footnote 57 democratisation may be facilitated, even in resource‐rich countries, if public spending is financed by tax money (Ross Reference Ross2004, Reference Ross2012). The ultimate effect of non‐tax revenue on democratisation is believed to lie in its use of resource wealth to appease public demand without inflicting costs on elites (Morrison Reference Morrison2014; see also Dunning Reference Dunning2008: 100–106; Tanaka Reference Tanaka2013). But, as we explained above using the tax literature, many developing economies prefer to adopt VAT because it allows them to adjust to global economies but not necessarily to raise revenue. In this regard, the presence of non‐tax revenue from resource rents may not always guarantee contemporary autocracies being able to avoid the imposition of taxes that results in collective bargaining between the ruler and the ruled.

Conclusion

The contemporary taxation–democratisation linkage emerged from external circumstances that are peculiar to the third wave of democratisation. Facing pressure for economic liberalisation from globalised markets, many developing economies have implemented a modern tax system – VAT – which was already devised and implemented in developed countries. Although the introduction of VAT may not have originated from domestic politics in each country, we argue that when introduced, the effective extraction of revenue by modern taxation has the potential to motivate citizens to hold the government more accountable and leads to democratisation.

By using a cross‐national time‐series dataset, this study demonstrates that VAT indeed plays a role in democratisation in the contemporary world. Although concerns about unobservable, omitted variables always exist, the empirical analyses provide consistent evidence that the introduction of VAT increases the chances for democratisation, and that collective action, such as riots that politicise the financial expropriation of the state, intensifies the effect of VAT. If careful attention is paid to distinct tax developments, the fundamental premise of the taxation–democratisation thesis has travelled from early to contemporary democratisation.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions were presented at the Annual General Conference of the European Political Science Association (EPSA) and the American Political Science Association (APSA) Annual Meeting. We would like to thank the followings for their comments: Robert Bates, Matt Clearly, Stephan Haggard, Jon Hanson, Nobuhiro Hiwatari, Yusaku Horiuchi, Christian Houle, Kensuke Okada, Jim Mahon, Anoop Sadanandan, Shiro Sakaiya, Katsumi Shimotsu, Abbey Steele and Teppei Yamamoto. We also thank Christian Houle for sharing his data on capital shares. We appreciate the research assistance of Naoki Egami, Tomoko Matsumoto and Hiroko Nishikawa. This project was funded by research grants from the Nomura Foundation and the Japanese government's grant‐in‐aid for scientific research (15H03310). The authors are listed in alphabetical order, implying equal authorship.

[Correction added on 30 April, 2018, after first online publication: Acknowledgments section is updated.]

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site:

Table A: Countries in the Dataset

Table B: Summary Statistics

Table C: Baseline Analyses without Controls

Table D: Analyses with Polity Scores

Table E: Baseline Analyses with Polity

Table F: Analyses with Other Tax Variables

Table G: Analyses without Former Communist Countries

Table H: Analyses with the Trade Openness Variable

Table I: Analyses with the Interaction with GDP per capita

Table J: Analyses with Entropy Balancing, Including the Trade Openness Variable

Table K: Analyses with Change in Democracy Variable

Table L: Dynamic Probit Analyses

Figure A: Entropy Balancing