Introduction

A substantial body of literature now explores the evolution of childcare policy. A closer examination of this expanding field reveals a recurring analytical pattern centred on the dominance of one perspective: the stability and transformation of this policy domain are primarily examined through conflicts and negotiation processes between established policy arrangements and emerging policy approaches, such as work–family reconciliation or social investment (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2018; León, Reference León2007; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Knijn, Martin and Ostner2008; Mahon et al., Reference Mahon, Anttonen, Bergqvist, Brennan and Hobson2012). However, other critical dimensions of policy change remain underexplored.

Firstly, the landscape of any policy domain is frequently marked by tensions between pre-existing policy legacies that co-exist within the domain (‘competing policies’) which significantly shape policy outcomes and the direction of policy development (Pierre & Peters, Reference Pierre and Peters2006). Internal conflicts arise when policies within the same domain overlap in objectives, target similar populations or require shared resources, leading to disagreements over resource allocation and service organisation (Sabatier & Weible, Reference Sabatier and Weible2014). Childcare policy exemplifies such dualism, with contrasting legacies: on one side, limited state involvement manifesting in market-driven services and cash-for-care schemes, and on the other, public investment in early childhood education and care services. The tension between proponents of minimal state intervention and advocates of expanded public provision significantly affects resource distribution and policy development (Daly, Reference Daly2011; Duvander & Ellingsæter, Reference Duvander and Ellingsæter2016; Nyby et al., Reference Nyby, Nygård, Autto and Kuisma2017).

A second, less studied dimension involves tensions within policies themselves. Once established, policies often generate self-reinforcing feedback effects, whereby political support consolidates, making the policy resistant to change (Pierson, Reference Pierson2004). However, recent research suggests that policies can also generate self-undermining feedback effects, whereby poor design or negative unintended consequences foster dissatisfaction and opposition, weakening policy sustainability (Jacobs & Weaver, Reference Jacobs and Weaver2015; Weaver, Reference Weaver2010). Inadequate policy design or unforeseen negative outcomes can increase policy costs, undermining public support for continued implementation (Jacobs & Weaver, Reference Jacobs and Weaver2015; Skogstad, Reference Skogstad2017). The interplay between self-reinforcing and self-undermining feedback is therefore critical in shaping long-term policy stability and change (Weaver, Reference Weaver2010).

Moreover, policy change driven by conflict and negotiation within one dimension can trigger tensions in another. Thus, for instance, tensions within policy can drive demands for reform, often through novel policy approaches that may clash with the self-reinforcing feedback of this policy. If this conflict leads to proposals for policy modification, tensions can arise with other policies in the domain if their interests are threatened. Conversely, tensions between competing policies can lead to the rollback of one policy, creating discontent and renewed demands for change, which may once again trigger conflicts between policies. Consequently, these dimensions are interdependent, and a comprehensive understanding of policy change necessitates examining all three in concert.

This article aims to provide an in-depth empirical analysis of these dimensions and their interactions through the case of South Korea, where childcare policy has experienced significant transformations over the past three decades (Gurín, Reference Gurín2023). Whilst existing studies have identified the influence of these dimensions in South Korea’s policy evolution (Fleckenstein & Lee, Reference Fleckenstein and Lee2017; Lee JS, Reference Lee2017; Kim, Reference Kim2017), their interrelationships remain insufficiently explored. To address this gap, the analysis focusses on the provision of services and cash-for-care allowances. Due to space limitations, the study excludes maternity, paternity and parental leave policies, which merit a separate investigation beyond the scope of this manuscript.

Theoretical perspectives on childcare policy change

The need for policy change has never been more urgent in modern welfare states, as governments navigate the complexities of ageing populations, shifting family dynamics and global economic competition. At the intersection of these forces lies the evolving landscape of childcare policy, where researchers have turned their attention to the balancing act between entrenched policy frameworks and the growing demand for novel solutions, such as work–family reconciliation and social investment (Fleckenstein & Lee, Reference Fleckenstein and Lee2014; Jenson, Reference Jenson2017; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Knijn, Martin and Ostner2008).

Work–family reconciliation policies have gained prominence, particularly in countries with declining birth rates. Governments have increasingly implemented measures such as subsidised childcare, extended parental leave and flexible working arrangements to support parental workforce participation, measures that echo the EU’s and OECD’s call for employment-driven social policy. This shift has led to a significant expansion of childcare infrastructure and professionalisation within the childcare workforce (Fleckenstein & Lee, Reference Fleckenstein and Lee2014; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Knijn, Martin and Ostner2008). Simultaneously, social investment policies have highlighted the importance of early childhood education for human capital development, emphasising both social and economic benefits. As a result, many welfare states have prioritised access to high-quality early childhood education, expanding preschool programs and improving service standards (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2018; Jenson, Reference Jenson2017; Mahon et al., Reference Mahon, Anttonen, Bergqvist, Brennan and Hobson2012; Staab, Reference Staab2010).

However, significant barriers remain. Although these policy approaches have significantly influenced childcare policies across welfare states, pre-existing policy arrangements ‘are not easily dislodged’ by new policy approaches (Mahon et al., Reference Mahon, Anttonen, Bergqvist, Brennan and Hobson2012, p. 427) due to strong, self-reinforcing feedback mechanisms that resist, block or blunt new policy approaches (Duvander & Ellingsæter, Reference Duvander and Ellingsæter2016; Gurín, Reference Gurín2024a; Léon, Reference León2007), resulting in policy changes that maintain the traits or imprints of the old legacies (Gurín, Reference Gurín2023; Morel, Reference Morel2007).

A closer examination of the literature reveals that childcare policy discussions often revolve around tensions between established policies and emerging approaches. However, the dynamics of childcare policy change extend beyond this binary conflict. Policy domains frequently encompass multiple overlapping legacies, giving rise to tensions and negotiations not only between older frameworks and new initiatives, but also amongst co-existing policies within the domain itself. In addition, these complex interactions influence stability and change of policy domains (Sabatier & Weible, Reference Sabatier and Weible2014). In childcare policy, such tensions manifest in two prominent ways. First, childcare regimes often reflect competing visions of family and state roles. On the one hand, cash-for-care allowances provide financial support to parents, particularly mothers, who opt to care for their children at home. This approach emphasises family autonomy and traditional caregiving norms, rooted in the belief that families should have the right to raise children with minimal state interference. However, critics argue that it can inadvertently discourage women’s labour market participation (Duvander & Ellingsæter, Reference Duvander and Ellingsæter2016; Morel, Reference Morel2007). On the other hand, policies aimed at expanding formal childcare services prioritise gender equality, social inclusion and early childhood development. By increasing access to quality early education and care, these measures seek to facilitate women’s employment and promote child development outcomes (Daly, Reference Daly2011; Nyby et al., Reference Nyby, Nygård, Autto and Kuisma2017). The fundamental tension between these two approaches arises from their competing demands on policy resources and divergent policy objectives, sparking ongoing debates over whether public funds should prioritise cash-for-care allowances or the expansion of formal childcare services. In Finland, this tension recently intensified when the government proposed a reform to divide the cash-for-care leave equally between both parents, sparking a fierce debate. The Centre party, having assumed power, rejected this proposal and instead focussed on restricting access to public childcare (Nyby et al., Reference Nyby, Nygård, Autto and Kuisma2017). This clash between competing childcare policies exemplifies how such tensions can lead to political polarisation and partisan gridlock, further complicating the policy landscape.

A second dimension of tension in childcare policy involves the persistent struggle between public and private service providers for limited resources (Daly, Reference Daly2010; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Shah, Quy and Owen2024). Public childcare systems, designed to offer affordable and equitable care, frequently grapple with chronic challenges, including underfunding, long waiting lists and capacity constraints. In contrast, private providers often offer more flexible childcare options but at a cost that remains prohibitive for many low-income families. The central policy debate revolves around resource allocation: whilst public systems require substantial investment to ensure universal access and quality, private providers often advocate for subsidies or vouchers to expand parental choice. Support for these models is polarised, with public services backed by labour unions and welfare advocates prioritising equity, whilst market-oriented actors argue that competition drives quality improvement (Daly, Reference Daly2010). As a result, policymakers face the ongoing challenge of balancing affordability, accessibility and service quality in a context of limited public resources and divergent policy preferences.

Finally, tensions often emerge within policy frameworks themselves, significantly influencing both the stability and transformation of a policy field (Weaver, Reference Weaver2010). The structural design of a policy can generate conflicting pressures, simultaneously fostering its preservation through self-reinforcing feedback and undermining it through self-undermining feedback (Jacobs & Weaver, Reference Jacobs and Weaver2015; Pierson, Reference Pierson2004; Weaver, Reference Weaver2010). As Mettler (Reference Mettler2016, p. 369) notes, ‘policies often develop over time in ways that could not have been foreseen by their creators, due to dynamics they themselves generate, including design effects, unintended consequences, and lateral effects’. These evolving dynamics can introduce costs, inefficiencies and dissatisfaction with policy performance, which may erode public confidence and intensify calls for reform (Weaver, Reference Weaver2010). This, in turn, can trigger the reorientation or even dismantling of pre-existing policy arrangements (Jacobs & Weaver, Reference Jacobs and Weaver2015; Skogstad, Reference Skogstad2017).

Whilst social policies are often associated with self-reinforcing feedback that stabilises their persistence (Campbell, Reference Campbell2012; Pierson, Reference Pierson2004), they are equally susceptible to self-undermining feedback when policy outcomes fail to meet public expectations. For instance, subpar childcare services can diminish public trust and weaken policy legitimacy, creating momentum for reform (Gurín, Reference Gurín2024b). As Skogstad (Reference Skogstad2017) emphasises, monitoring mechanisms play a crucial role in identifying such performance deficits, compelling policymakers to reconsider existing strategies. A prominent example is the marketisation of childcare, which, whilst intended to expand service provision, has often resulted in reduced service quality and unequal access – outcomes that have sparked renewed demands for policy change (Daly, Reference Daly2010; Gurín, Reference Gurín2024b). However, despite the potential for negative feedback to drive policy transformation, such calls for change frequently clash with entrenched self-reinforcing mechanisms that resist modification. This tension between stabilisation and disruption remains insufficiently explored within the childcare policy literature, underscoring significant gaps in our understanding of how feedback dynamics shape the evolution this policy field.

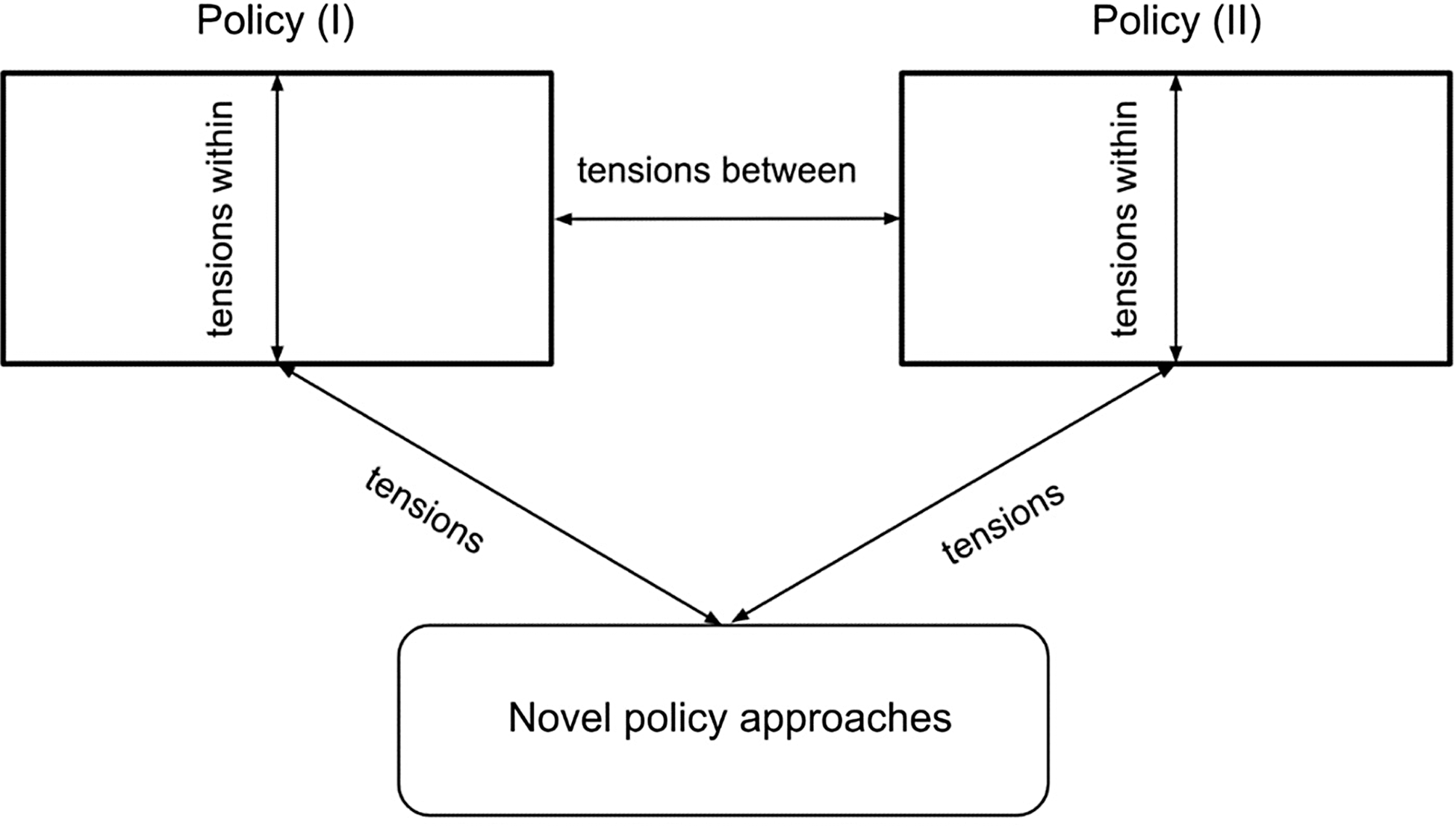

Childcare policy dynamics are thus often shaped by tensions across multiple dimensions simultaneously, rather than being confined to a single point of conflict. Some policies may face challenges from novel policy approaches, whilst others might encounter self-undermining feedback. In certain cases, policies experience simultaneous challenges across all three dimensions, which can significantly increase the likelihood of a ‘dislodging’ of pre-existing policy arrangement (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Multidimensional perspective to policy change.

Conflict and negotiation processes, along with resulting policy changes, not only span multiple dimensions, but also are deeply interrelated. Tensions within policies can generate demands for reform, often through the introduction of novel policy approaches (Jacobs & Weaver, Reference Jacobs and Weaver2015; Gurín, Reference Gurín2024b). Supporters of these new approaches may clash with the self-reinforcing feedback mechanisms of the existing policy. If this conflict leads to a decision to modify the policy, tensions may arise with other policies within the same domain, particularly if the proposed reforms threaten their interests.

Another possible outcome of the clash between self-reinforcing and self-undermining feedback mechanisms is the introduction of a new policy alongside the existing one. When a new policy is added without altering the old policy, even as the old policy experiences self-undermining feedback, this phenomenon can be most precisely termed competitive policy layering. The newly introduced policy competes for resources, public support and legitimacy, not only with the old policy, but also with other policies in the domain, potentially fragmenting the policy landscape.

Conversely, tensions between competing policies can lead to the retrenchment or rollback of one policy, creating losers who may experience dissatisfaction. This feedback can, in turn, generate renewed demands for change. If the government attempts to address these demands, it may once again spark tensions between competing policies, perpetuating a cycle of policy conflict and adjustment.

The complex network of interactions highlights the multi-faceted nature of policy change, showing that tensions across various dimensions are interconnected and influence each other. Understanding these linkages is crucial for grasping policy evolution, as conflicts both within and between policies continuously reshape the policy environment in often unpredictable ways.

Methodology

To investigate the various dimensions of tension and their interconnections driving changes in childcare policy, this study adopted a mixed-methods approach, integrating document analysis and expert interviews. Document analysis served as the primary method, offering a comprehensive understanding of the historical and contemporary landscape of South Korea’s childcare policy. By systematically reviewing government reports, strategic policy documents, media coverage of reforms and academic literature in both English and Korean, the study built a robust empirical foundation, capturing both formal policy developments and subtle shifts in public discourse and institutional priorities over time. Recognised as a key tool in policy change research, document analysis provides a structured framework for identifying patterns and trends in institutional actions and stakeholder interests (Bowen, Reference Bowen2009). The inclusion of diverse document types facilitated data triangulation, strengthening the reliability of the findings and offering deeper insights into competing interests and policy trajectories.

To complement the document analysis, we conducted expert interviews, which provided an interpretive lens to uncover insights not readily accessible in written records, such as the motivations behind policy decisions and the strategies employed during policy negotiations (Aberbach & Rockman, Reference Aberbach and Rockman2002). We chose to interview three scholars with extensive expertise in Korean childcare policy, each bringing a distinctive perspective on the long-term forces influencing policy change, selected for their deep, long-term engagement with the field and/or their active participation in policy discussions. Their insights were invaluable in capturing the underlying dynamics influencing policy change, particularly the long-term ideological shifts and policy tensions not always visible in official records.

Multiple dimensions of tension: The case of Korea’s childcare policy change

Childcare policy arrangements prior to the expansion

This section presents the detailed empirical findings of our Korean case study. Historically, childcare in South Korea was primarily the responsibility of extended families, reflecting deep-rooted cultural norms of familial caregiving (Lee, Reference Lee2018). The emerging welfare state, shaped by the belief that care and welfare should be managed within the family unit, was initially reluctant to assume responsibility for childcare provision. Instead, it relied on intergenerational support structures, leading to the neglect of a comprehensive childcare policy framework. Child benefits were not provided, and access to childcare services was restricted to those deemed most in need – primarily single parents and low-income couples (Fleckenstein & Lee, Reference Fleckenstein and Lee2014).

By the 1980s and 1990s, however, childcare had become an increasingly pressing social issue in South Korea, driven by shifting family structures and mounting concerns over workforce sustainability. In response to rising demands for better childcare support, the government began expanding its childcare policy framework (Baek et al., Reference Baek, Sung and Lee2011). A pivotal moment occurred with the introduction of the Infant Care Act in 1991, which formally recognised both central and local governments’ responsibility for childcare provision. Key policy measures, such as subsidies for low-income families and the launch of the Three-Year Plan for the Expansion of Childcare Centres (1995–1997), marked the initial steps towards a more supportive and state-engaged childcare system (Lee, Reference Lee2018).

Nevertheless, remnants of the earlier policy framework persisted, particularly the continued influence of residual welfare principles that minimised direct cash benefits and limited the state’s direct involvement in childcare service provision. Rather than expanding public childcare infrastructure, the government prioritised market-based solutions, encouraging private sector involvement in service delivery. As a result, the number of private childcare providers steadily increased, whilst public childcare services remained underdeveloped and insufficient to meet demand (Kim, Reference Kim2017).

New policy approaches entering the childcare policy regime and the roots of negative feedback

The Asian financial crisis of 1997–1998 profoundly reshaped South Korea’s social policy landscape, creating a critical window for feminist activists to advocate for reforms addressing women’s interests. They emphasised that achieving gender equality and expanding women’s economic participation required comprehensive policies to support work–family balance (Baek, Reference Baek2009). Whilst the Kim Dae-jung administration (1998–2002) prioritised economic recovery, it also acknowledged the need to reform the welfare state, particularly childcare policies, to ease the burden on working parents and encourage greater female workforce participation.

In response, the government broadened childcare subsidies beyond low-income families to include middle-class and dual-earner households, whilst actively promoting the expansion of private childcare services (An & Peng, Reference An and Peng2016). Deregulation of the childcare sector led to a rapid proliferation of commercial providers, with the number of childcare centres rising from 6,538 in 1997 to 11,046 by 2002 (Fleckenstein & Lee, Reference Fleckenstein and Lee2017). However, direct state involvement remained limited, with the government focussing primarily on financial support and passive administrative oversight rather than direct service provision.

Despite the progressive intent behind these reforms, the policy produced significant unintended consequences and generated negative (self-undermining) feedback. Persistent challenges emerged within the childcare sector, including widespread dissatisfaction and public mistrust linked to inadequate service quality in private childcare centres (Baek, Reference Baek2009). Quality concerns were driven by issues such as high child-to-teacher ratios, minimal regulatory oversight, and the lack of regular supervision to ensure standards were upheld (Na et al., Reference Na, Seo, Yoo and Park2003). Compounding these challenges were the persistently low wages and limited career advancement opportunities for childcare workers, especially within private facilities, which further eroded service quality and staff retention rates. As a result, parental dissatisfaction with private childcare services grew, with many families perceiving public childcare facilities as superior due to their greater affordability and higher service standards (Hwang, Reference Hwang2005). Consequently, the central policy challenge shifted towards reforming private childcare services and expanding public childcare infrastructure to meet rising parental expectations and ensure more equitable access to quality care.

Social investment as the catalyst for tensions between public and private childcare

Roh Moo-hyun’s administration (2003–2007) was driven by a dual commitment to addressing the negative feedback effects from earlier childcare reforms and advancing the principles of the social investment approach. Recognising that prior policies had failed to adequately meet families’ needs, the administration prioritised comprehensive childcare reforms to correct these shortcomings (Baek, Reference Baek2009). At the same time, Roh’s policy direction was influenced by the social investment perspective, emphasising that early childcare and education – particularly for children from low-income families – was not only vital for child development, but also essential for strengthening long-term human capital formation. This dual focus led to the introduction of initiatives such as the Sa-ssak Plan and the Saeromaji Plan, which aimed to improve the affordability, quality and diversity of childcare services. These efforts laid a comprehensive foundation for expanded childcare provision, with a central goal of increasing the percentage of children enrolled in public childcare facilities to 30%. Footnote 1

The government’s initiatives to enhance access to public childcare, however, encountered strong resistance from both local governments and private childcare providers (Lee SH, Reference Lee2017). This opposition was driven by the substantial responsibilities the policy placed on local authorities, requiring them not only to address logistical challenges such as land acquisition and facility management, but also to contribute one-fourth of the budget for the expansion of public childcare services. Simultaneously, private childcare organisations mounted fierce resistance, perceiving the abrupt policy shift as unfair, particularly given their previous collaboration and support from earlier administrations. The rising preference amongst parents for public childcare facilities further intensified these concerns, as private providers feared significant financial losses due to reduced demand.

Given that local politicians often maintained close ties with private childcare providers, their interests became deeply intertwined, resulting in passive attitudes towards the expansion of public facilities (Chang, Reference Chang2011). Faced with escalating objections and even threats from private providers, policymakers grew increasingly concerned that widespread closures in the private sector could lead to significant disruptions in childcare availability. Ultimately, these tensions led the Ministry of Strategy and Finance to terminate the expansion plan by withholding additional funding for public childcare facilities (Lee SH, Reference Lee2017).

As the dominance of private childcare providers persisted – and even resisted the introduction of a new accreditation scheme aimed at improving service quality and regulation (Lee SH, Reference Lee2017) – the government was compelled to adjust its strategy. Shifting towards greater reliance on existing private services, policymakers aimed to reduce the financial burden on families whilst addressing inequalities in access to quality care and encouraging higher female labour force participation. To this end, the government expanded differential childcare subsidies to cover middle-income families and introduced free childcare for children under 5 years of age and children with disabilities (Baek, Reference Baek2009).

Furthering this market-based approach, the Basic Subsidy Scheme was introduced in 2005, providing direct financial support to private childcare providers on behalf of families with children up to the age of 2 years. This policy sought to reduce cost disparities between public and private childcare services, ensuring greater equity amongst families accessing care. However, rather than curbing the dominance of private providers as initially intended, this strategy of ‘private-based publicness’ (Kim, Reference Kim2017) inadvertently fuelled further expansion of the private sector – an outcome long cautioned against by civil society actors (Baek, Reference Baek2009; Lee SH, Reference Lee2017).

The embracement of neoliberalism: the introduction of childcare vouchers

Neoliberal ideology, emphasising minimal government intervention and individual responsibility, profoundly shaped South Korea’s childcare policy during the centre-right Lee Myung-bak administration (2008–2013). Departing from his predecessor’s more interventionist stance, Lee approached childcare as a market commodity, introducing electronic vouchers to stimulate competition amongst providers, expand consumer choice and reduce direct state involvement in service delivery. The voucher system provided financial assistance to families, aiming to empower parents to select childcare services that best suited their preferences and needs, whilst simultaneously fostering a more dynamic and responsive childcare market (Kim & Nam, Reference Kim and Nam2011) and curtailing the supplementation of public services (Kim, Reference Kim2017).

Whilst the voucher system aligned with neoliberal ideals of market efficiency and individual freedom, it also generated significant challenges related to equity, quality and accessibility. Increased market competition amongst providers often prioritised profitability over service standards, leading to disparities in the quality of care available, particularly disadvantaging lower-income families who could not afford premium services. This commercialisation of childcare was widely criticised for contributing to inconsistent service quality, reduced regulatory oversight, and growing public distrust in private childcare providers (Choi, Reference Choi2016). These tensions deepened ideological divides between those advocating for limited state involvement and those calling for greater public investment to ensure equitable access and higher standards of care.

The unintended consequences of childcare bias and the emergence of the cash-for-care

The prevailing childcare policy regime in South Korea has long demonstrated a strong preference for service-based initiatives, whilst largely neglecting the implementation of direct cash benefits. Since the early 2000s, academics, civil society organisations and political parties have consistently called for the introduction of child benefits to provide direct financial support to families. However, this reform was repeatedly deferred, as policymakers framed it as a long-term objective, citing inadequate financial backing from both businesses and the Ministry of Finance as key barriers (Lee JS, Reference Lee2017; Choi, Reference Choi2020). Whilst discussions surrounding child benefits remained stalled, the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family announced during the public hearing for the 1st Basic Family Policy Plan (2006–2010) its consideration of cash-for-care allowances aimed at low-income families unable or unwilling to access the childcare market (Lee JS, Reference Lee2017; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kim and Lee2013).

The expansion of government assistance for families using childcare services – services that many families still did not fully trust – led to questions of social justice and equity. Families who refrained from using private childcare services asserted that they were left unsupported (Min & Jang, Reference Min and Jang2015; Pyo & Kim, Reference Pyo and Kim2021). In response to mounting pressure, the Lee Myung-bak administration introduced a means-tested cash-for-care allowance for children up to age 2 years in 2009. As one expert (I) explained:

The policy emerged during a time when child development experts, critical of formal childcare centres’ effects on children’s well-being, held greater influence in election campaigns and policy decisions than social welfare scholars, who traditionally supported formal childcare systems. (…) In addition, the government prioritized financial assistance for families over expanding public daycare services or improving private daycare quality, viewing cash transfers as a cost-effective approach and a tool for electoral gain. Public opinion polls had shown dissatisfaction among women in their 30s with the lack of home care support, prompting advisors to recommend direct cash payments.

However, the cash-for-care allowance faced considerable criticism from social welfare scholars, civic organisations and childcare advocacy groups. These actors had consistently opposed the policy for more than 15 years, arguing that direct cash transfers should not be introduced without a significant expansion of public childcare services – something families had long demanded but the government had yet to adequately address. Critics also warned that cash-for-care allowances could discourage women’s workforce participation and undermine progress towards gender equality (Lee JS, Reference Lee2017). Despite persistent objections and mounting concerns, the government remained unresponsive, prioritising short-term financial incentives over structural reforms in childcare service policy.

Dilemma: support for public services, private services or cash-for-care?

Efforts to expand cash-for-care benefits have been ongoing since February 2009, with a focus on broadening coverage. However, these attempts were either dismissed or outright rejected by the Ministry of Health and Welfare due to budgetary constraints (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kim and Lee2013). As public awareness and uptake of the policy grew, perspectives within the National Assembly began to shift. The Democratic United Party endorsed expanding cash-for-care to cover all children up to age 5 years, regardless of family income. In contrast, the ruling party, which had originally introduced the policy, opposed this expansion and even proposed budget reductions in December 2010. However, mounting pressure from opposition parties and public opinion forced the withdrawal of the budget cut proposal. Following a series of electoral defeats, Park Geun-hye’s faction within the ruling party successfully convinced both party leadership and the Presidential office of the necessity for policy expansion, leading to a more favourable stance towards increasing cash-for-care coverage (Kim, Reference Kim2016; Lee JS, Reference Lee2017).

Despite the initial popularity of the cash-for-care policy – praised for reducing child rearing costs and supporting child development – proposals to expand the program universally (removing the means-test requirement) sparked considerable controversy. Opposition came primarily from advocates of public childcare services, who argued that such reforms could reinforce intergenerational caregiving pressures and undermine women’s workforce participation. Civic and feminist organisations, including the People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy and the Korean Federation of Women’s Organizations, denounced the expansion as gender-regressive, labelling it ‘anti-equal’ due to its potential to limit women’s economic involvement (Lee JS, Reference Lee2017; Song, Reference Song2014). Instead, these groups championed the introduction of universal child benefits Footnote 2 and prioritised the expansion of public daycare centres and kindergartens, arguing that these structural improvements were essential before considering further cash-for-care reforms (Lee JS, Reference Lee2017).

The cash-for-care policy, however, was never the sole focal point in debates over childcare expansion. Parallel discussions emerged around the expansion of national and public daycare centres and kindergartens, alongside proposals for free universal childcare, championed by the opposition Democratic United Party (Lee, Reference Lee2022). The idea of free childcare had initially surfaced in the late 1990s but was postponed due to the Asian financial crisis. When the debate resurfaced in 2007, then-presidential candidate Lee Myung-bak proposed free childcare for all children aged 0 –5 years. However, after his election, the policy direction shifted towards expanding childcare subsidies rather than providing universal free childcare, with the administration arguing that such a policy would financially destabilise the country (Min & Jang, Reference Min and Jang2015; Kim, Reference Kim2016).

By the early 2010s, mounting public support for universal welfare, exemplified by the free school meals campaign, significantly influenced political dynamics. The Conservative party’s rejection of this initiative had resulted in a major electoral setback in local elections (Lee & Lee, Reference Lee and Lee2013). In response, the ‘pro-welfare’ faction within the Conservative Party, led by Park Geun-hye, revisited the concept of free childcare. This shift led to the phased introduction of universal free childcare – first covering children up to age 2 years in 2012, then expanding to all children up to age 5 years by 2013 (Lee, Reference Lee2022).

Following the implementation of free childcare, which subsidised basic childcare fees for public and accredited private daycare centres through a mix of direct provider subsidies and parental vouchers, daycare utilisation surged. This rapid increase in demand led to capacity shortages and significant financial strain, particularly on local governments. Initially, the Seoul municipal government was expected to cover 80% of childcare costs (with the central government funding the remaining 20%), whilst other local governments were required to shoulder 50% of the costs. Disputes soon arose over the unequal financial burden, eventually leading to a compromise that reduced Seoul’s share to 65% and lowered other local governments’ share to 35% (Baek, Reference Baek2015).

Amid these budgetary pressures, the Ministry of Finance opposed expanding cash-for-care allowances, whilst the Seoul municipal government even considered suspending payments to parents temporarily (Lee JS, Reference Lee2017). However, the Ministry of Health and Welfare successfully argued that increasing cash-for-care benefits could ease the strain by offsetting rising public childcare costs caused by free childcare. This policy shift resulted in the expanded cash-for-care allowance being made available to all children up to age 5 years, with the benefit amount doubling for infants under 1 year old (Song, Reference Song2014). Consequently, cash-for-care increasingly came to be regarded as a substitute rather than a complement to childcare services, marking a significant departure from previous administrations that had prioritised the expansion of childcare services over direct financial allowances. As a result, the number of cash-for-care beneficiaries exceeded 1 million in 2013, whilst the number of public and national daycare centres, as well as the number of children enrolled in them (approximately 155,000 in 2013), remained stagnant (Kim, Reference Kim2017).

The government’s reluctance to invest in national and public daycare centres stemmed largely from concerns about rising public expenditures. Concurrently, however, there was pressure on the government to enact further reforms in childcare services, particularly to address the persistent discrepancy between supply and demand in childcare hours, notably pronounced in private childcare facilities (Kang, Reference Kang2017). To tackle this issue with minimal costs, the government introduced a Customised Childcare Program in 2016. This program differentiated between 12-hour full-time care services for working mothers and abbreviated 6-hour services for mothers not in the labour market. To minimise opposition from private daycare centres, which risked losing revenue, the government allowed them to increase their basic service fees (Choi, Reference Choi2016). To justify the program’s restrictions on service access for stay-at-home mothers, policymakers argued that maternal care was beneficial for children’s emotional development (Hwang, Reference Hwang2016). However, this framing inadvertently stigmatised working mothers, suggesting they were less attentive caregivers. This rhetoric further fuelled tensions between stay-at-home and working mothers, underscoring the ongoing policy conflicts surrounding childcare access and support.

Heightened tensions between public and private services: Public childcare reclaims executive support

Korea’s historically limited emphasis on childcare service quality has led to persistent parental distrust of childcare centres, with incidents of child abuse reported even in public facilities (Cho, Reference Cho2015). This lack of confidence, combined with the expansion of the cash-for-care allowance in 2013, contributed to a decline in the use of childcare services, as more families opted for home-based care supported by the allowance (Kim, Reference Kim2017).

The centre-left Moon Jae-in administration (2017–2022) responded by adopting a policy orientation centred on the socialisation of care, aligning with the broader welfare paradigm shift towards inclusive welfare. This orientation aimed to strengthen public responsibility for childcare and improve service quality, as already attempted during the Roh Moo-hyun. Public support for this direction was evident, with 35.9 per cent of respondents in a nationwide survey by the Ministry of Health and Welfare identifying it as the most desirable childcare strategy (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2018). Unlike previous administrations, which had largely focussed on expanding the availability of childcare services and providing free childcare, the Moon government emphasised improving the quality of care. Key measures included enhancing teacher qualifications, reducing teacher-to-child ratios and institutionalising mandatory daycare evaluations to raise service standards.

As part of this strategy, the 4th Basic Plan for Low Fertility and an Aging Society sought to expand public childcare capacity, setting ambitious goals of raising enrolment in public childcare institutions to 40 per cent by 2022 and 50 per cent by 2025. However, policy implementation faced substantial barriers, particularly from private childcare associations that opposed increased public provision. For example, amendments to the Child Care Act (2017), which would have allowed public childcare facilities to be established in unused primary school classrooms, were postponed due to strong resistance from these associations.

Tensions between the childcare service expansion and the cash-for-care allowance became more pronounced during Moon’s presidency, particularly when the Presidential Committee on Aging Society and Low Fertility sought to incorporate diverse stakeholder perspectives. As one of our experts (I) clarified:

A significant source of resistance emerged from stay-at-home mothers, many of whom had exited the workforce due to job market limitations. These mothers argued that policies disproportionately favoured working parents, as children attending childcare centres received financial support nearly four times greater than infants cared for at home. Some policy experts, perceiving this criticism as inconsistent with broader social investment goals, proposed abolishing the cash-for-care allowance under the 4th Basic Plan for Low Fertility and an Aging Society. However, the Blue House ultimately rejected this proposal, reflecting the continued influence of competing policy priorities and stakeholder interests.

Initially, the government adopted a policy stance of ‘services first, allowances cautiously’, prioritising the expansion of public childcare services over cash-for-care allowances. However, this approach shifted due to two significant developments. First, the early introduction of child benefits – a monthly allowance of 100,000 KRW for children under 6 years from households within the lower 90 per cent income and asset brackets, available to both children attending formal childcare and those being cared for at home – proved highly popular amongst the public, increasing political support for direct financial assistance. Second, mounting concerns over Korea’s persistently low birth rates heightened the pressure to diversify family policy tools, leading to a recalibration of policy priorities.

In response, the Moon administration had to carefully manage tensions between cash-for-care allowances and childcare services, ultimately maintaining a dual policy structure. This approach sought to expand public childcare whilst preserving the cash-for-care allowance, recognising that a full transition towards public childcare could risk alienating a significant portion of the population. By balancing these two strategies, the administration aimed to offer families greater flexibility in their care choices whilst incrementally strengthening public service provision.

Eventually, Moon’s government reformed the cash-for-care allowance in 2022 to better address the needs of families with younger and older children. Following this reform, the cash-for-care policy was restructured into a two-instrument system, each targeting different age groups with distinct benefit amounts whilst continuing to support families whose children do not attend formal childcare services: The first, the ‘infant allowance,’ targets children aged 0–23 months and provides an increased financial benefit of 300,000 won per month, aimed at alleviating the financial burden during the early stages of home-based childcare. The second, retaining the previous naming as the ‘cash-for-care allowance,’ applies to older children aged 2–7 years and maintains the existing benefit amount of 100,000 won per month. This policy shift, however, was not solely motivated by demographic concerns. The government also aimed to appeal to key voter groups, particularly cash-for-care beneficiaries, in anticipation of upcoming elections. By emphasising the appropriateness of maternal caregiving, especially for younger children, the administration reinforced traditional caregiving norms whilst simultaneously working to secure electoral support.

Conclusions

The central aim of this article is to deepen the understanding of childcare policy change by emphasising the importance of examining multiple dimensions of tension and negotiation within policy development. Whilst scholars have extensively investigated conflicts between pre-existing policy arrangements and emerging policy approaches (León, Reference León2007; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Knijn, Martin and Ostner2008; Mahon et al., Reference Mahon, Anttonen, Bergqvist, Brennan and Hobson2012), other critical dimensions – namely tensions within policies and tensions between coexisting policies – remain underexplored in the field of childcare policy research. Our analysis demonstrates that incorporating these overlooked dimensions into the study of policy change can offer a richer, more comprehensive understanding of welfare state transformations.

To illustrate this multidimensional approach, we applied it to the analysis of South Korea’s childcare policy developments from the 1990s to 2022. Our empirical investigation revealed that whilst the policy framework of the earlier childcare regime was repeatedly challenged by emerging policy paradigms – such as work–family balance, social responsibility and universalism – this dynamic represents only part of the broader picture. Korean childcare policy evolution has also been shaped by two other forms of tension. First, internal tensions within policies emerged, particularly in the form of self-reinforcing and self-undermining feedback mechanisms. These dynamics either supported or opposed elements such as private childcare provision and cash-for-care allowances, influencing policy stability and reform. Second, tensions between competing policies further complicated the landscape, as policy networks advocating for cash-for-care allowances, private childcare services and expanded public childcare services often clashed over resource allocation, policy priorities and ideological goals.

Moreover, our analysis demonstrates that policy changes driven by conflict and negotiation within one dimension often trigger tensions across others. For example, government efforts to address external pressures related to work–family balance by expanding childcare services through a weakly regulated private market inadvertently sparked conflicts between supporters and critics of continued private childcare provision, particularly as concerns over service quality emerged (Hwang, Reference Hwang2005). The government’s failure to adequately respond to demands for substantial improvements in private childcare and the expansion of public childcare – coupled with state’s previous reluctance to provide direct financial allowances – intensified dissatisfaction amongst families. Many families did not utilise formal childcare services, either due to concerns over the quality of private providers or because of a shortage of public childcare, leaving them without financial support (Baek, Reference Baek2009). This disparity, wherein only families using formal childcare received public support, heightened perceptions of inequity and ultimately led the government to introduce cash-for-care allowances (Min & Jang, Reference Min and Jang2015; Pyo & Kim, Reference Pyo and Kim2021). An additional policy was thus introduced into the childcare policy domain alongside existing policies without altering them. This new policy competes for resources, public support and legitimacy, a phenomenon we refer to as competitive policy layering.

This intricate web of interactions underscores the complexity of policy change, emphasising that tensions across different dimensions are not isolated but mutually reinforcing. Recognising these interconnections is essential for understanding the dynamics of policy evolution, as conflicts within and between policies shape and reshape the policy landscape in unpredictable ways.

In conclusion, we acknowledge a key limitation of this study. The primary constraint of our analysis lies in its focus on tensions within the childcare policy domain itself, without fully accounting for the influence of external policy areas. Whilst our findings shed light on how existing childcare policies interact, broader patterns of policy stability and change – both within childcare and other domains – are often shaped by cross-sectoral dynamics involving pension, education and labour market policies. These interdependencies can play a critical role in shaping childcare policy trajectories and deserve further scholarly attention.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279425100895

Availability of data and materials

The data used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply thankful to Martina Brandt, Young Jun Choi and Sigrid Leitner for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article, as well as to the anonymous reviewers for their rigorous and detailed feedback. We deeply appreciate the time and expertise offered by the experts involved in the study. Finally, we would like to note that, since July 2024, the corresponding author has been employed at the Collaborative Research Center 1342 “Global Dynamics of Social Policy” (University of Bremen), which is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)-project number 374666841-SFB 1342. The revisions of this paper were therefore carried out at this center.

Competing interest declaration

Competing interests: The authors declare none.

Funding

The authors declare none.