Jaubert’s Hypothesis and the Last Supper

In the early 1950s, the French scholar Annie Jaubert (1912–1980) revived the subject of biblical calendars to account for the discrepancies between the Synoptic gospels and John’s gospel on the chronology of the last days of Passion Week. In the Synoptics, the Last Supper is the Passover meal on Thursday night and Jesus is crucified the next day, Friday, on the Feast of Unleavened Bread. In the fourth gospel, the Last Supper, which takes place on Thursday night, is not a Passover meal. Jesus is crucified the following day, Friday, and the Passover meal takes place that night, coinciding with the sabbath. To explain these different timescales, Jaubert proposed that the Synoptics and John followed two separate Jewish calendars. The Synoptics followed a fixed 364-day year sectarian calendar, which she named the “Jubilees-Qumran” calendar (see below), whereas the authors of John described the sequence of events from the final meal to the crucifixion according to the Jewish lunisolar calendar.Footnote 1

Jaubert’s theory that a Jewish sectarian calendar was used in the Synoptic gospels was criticized on historical and internal literary grounds by Christian scholars working on the then-unpublished Dead Sea Scrolls, Pierre Benoit and J. T. Milik.Footnote 2 Since then, the “Jubilees-Qumran” calendar has been confirmed in published original source documents found at Qumran. These also contain the priestly courses (Heb: mišmarot) which explicitly state that Passover took place on the third day of the week (Tuesday).Footnote 3 Therefore, since Tuesday night is not relevant in the timeline of Passion Week in the Synoptic gospels it is accepted by most modern scholars that the New Testament element of her theory cannot be sustained.Footnote 4 Notwithstanding the reception to her hypothesis of the different chronologies of Passion Week, Jaubert’s theory that the 364-day year calendar is an ancient priestly calendar that is present in the Hebrew Bible is still discussed in the field of biblical calendars.

Benoit regarded the possible early antiquity of the 364-day year calendar as plausible.Footnote 5 His open conclusion is relevant to the subject today, albeit involving unresolved scholarly arguments of a historical, theological, or technical nature.Footnote 6 In contrast to these discussions, the criticism of Jaubert’s theory by Ben Zion Wacholder and Sholom Wacholder, focusing on the days of the week, has been one of the most influential in opposing her calendrical hypothesis.Footnote 7

In this article, I first explain Jaubert’s thesis regarding what she claimed is an ancient biblical calendar structured around the sabbath. I then turn to Wacholder and Wacholder’s article alleging that Annie Jaubert’s calendrical hypothesis is a “fallacy,” and I critique their arguments. The study attempts to move the conversation forward with a different approach. I take a new look at the Flood calendar of Genesis 7–8 as it appears in the Dead Sea Scrolls, and I compare it to Jaubert’s theory. The Qumran text painstakingly applied a 364-day year calendar and the days of the week to the biblical Flood narrative. Jaubert had also superimposed the 364-day year calendar and the days of the week on the chronology of the Genesis text of the deluge in her methodology to prove her hypothesis, without any knowledge of the Qumran manuscript.

The “Jubilees-Qumran” Calendar

Jaubert followed a hypothesis by Dominique Barthélémy that the 364-day year calendar in the Ethiopic Book of Jubilees (Jub. 6.17–38) began the year on the fourth day of the week, (Wednesday), when the sun, moon and stars were created (Gen 1:14–18).Footnote 8 Based on this calendar, she tracked the days of the month in Jubilees when the patriarchs travelled (see Table 1, below).Footnote 9

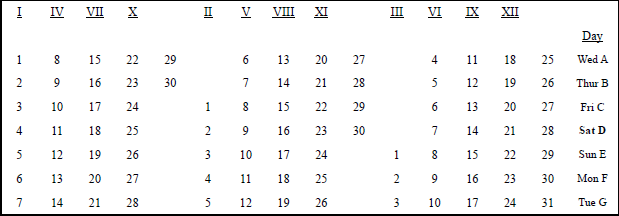

Table I. The 364-day Jubilees-Qumran calendar beginning 1/I (Wednesday). The days of the week are numeric. The months are presented in Roman numerals

The fixed 364-day year calendar is divisible by seven, comprising exactly 52 weeks in the year: it is divided into 91-day quarters, each consisting of two months of 30 days and one month of 31 days months (Months III, VI, IX, XII). Jaubert found that in Jubilees activities occurred on Wednesday, Friday and Sunday. She referred to these days of the week as “liturgical” days as she found that the festivals, Passover, Shavuot (Weeks/Pentecost), Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement) and Succot (Tabernacles) occurred on these days.Footnote 10 She also found that the first day of the month in each 91-day quarter, occurs on the same day of the week every year on Wednesday, Friday and Sunday, respectively.Footnote 11 She represented the days of the week by the letters A to G: the sabbath is marked as D, when no journey took place; and A, is the first day of the year, in Month I, Wednesday.Footnote 12

From an unpublished private communication from J. T. Milik she understood (but had not seen herself) that a calendar similar to that in the Book of Jubilees had been found in Qumran.Footnote 13 Jaubert was also aware, from Milik, of what she termed a “modified calendar”: a form of the 364-day year calendar, that “had been adapted to the phases of the moon, yet still preserved the same numerical days of the week for liturgical feasts.”Footnote 14

Since the Hebrew calendrical texts from Qumran contained the numerical days of the week in contrast to Jubilees, which does not contain the days of the week, Jaubert referred to the fixed date 364-day year calendar as the Jubilees-Qumran calendar.Footnote 15

From her reconstruction of the Jubilees calendar, first published in 1953, she argued that the Jubilees-Qumran calendar is confirmed by events in the Hexateuch. When she applied the 364-day year calendar to these biblical books, she found that activities took place on Wednesday, Friday and Sunday, and that no movement took place on the sabbath.Footnote 16 Jaubert applied her findings to the Hexateuch because the calendrical dates in these six books are numerical. Other biblical books (within the remaining Former Prophets, the Latter Prophets, and Writings) also contain references to non-Israelite calendars, accession years, the Babylonian month names, and other calendrical formulas which may reflect different calendrical systems.

Jaubert assigned the scheme to the Priestly stratum of the Documentary Hypothesis,Footnote 17 variously describing the Jubilees-Qumran calendar as “substantially the same as that of the priestly school,”Footnote 18 and the “priestly calendar.”Footnote 19 In separate comments on the proposed “history of the ancient priestly calendar” (Jaubert’s italics),Footnote 20 she postulated that at a later period the 364-day calendar introduced the “Babylonian style names” as an “intermediary calendar.Footnote 21 There was “a gradual modification of the ancient priestly system. . . at first under Babylonian influence, then, during the course of the third century, under the growing influence of Hellenism.”Footnote 22 By this, Jaubert meant the introduction of the Seleucid calendar in Judea, which was lunisolar.Footnote 23

She conjectured that the Hasmonean uprising was, in part, due to the imposition of the Seleucid calendar, which the Maccabees would have resisted, but that their descendants accepted. “The ‘conservatives’—whose views are voiced in the Book of Jubilees—would then have returned to the integral calendar which God had revealed and which ‘the whole of Israel’ had abandoned.”Footnote 24 She supported this thesis by arguing that the lunisolar calendar may have already been in existence when Ben Sira was written (second century BCE), as the book gives a role to the moon in relation to the festivals (Sir 43:6–8; 50:6), in contrast to the anti-lunar polemics in Jubilees (Jub. 6:34).Footnote 25

A central plank of Jaubert’s hypothesis was that the 364-day calendar fell out of use in later, mainstream Judaism, if it had ever been used in practice. Jaubert refined her thesis by proposing that after the Babylonian exile the Babylonian lunisolar calendar would have been used as the civil calendar, and the older “priestly calendar” for liturgical purposes only, and furthermore, that towards the fourth or third centuries BCE both calendars co-existed for the purposes of Temple liturgy.Footnote 26

In the late mid-twentieth century, scholarship on the Jubilees calendar and the early Jewish lunisolar calendar generally supported Jaubert’s theory. The consensus view was that the writers of Jubilees polemicized against the lunisolar calendar and that they saw it as a threat to the more ancient 364-day calendar. J. B. Segal latterly expressed the view that the 364-day year Jubilees calendar was the dominant Jewish calendar prior to the wider establishment of the lunisolar calendar. Consequently, the displacement of the 364-day calendar gave rise to the polemical tone in Jubilees.Footnote 27

Similar ideas on the reaction of the Maccabees to the Seleucid calendar had also been presented by Milik,Footnote 28 and Talmon,Footnote 29 and later expanded upon by VanderKam.Footnote 30 VanderKam’s thesis that there was a schism created by mainstream Jewish groups who used the Seleucid calendar, and a sectarian group, or groups, who rejected it in favour of the 364-day year calendar was challenged by Philip Davies. Davies argued that not only was the 364-day year calendar possibly ancient, but that the Babylonian lunisolar calendar had been used by Jews from an earlier date than Seleucid rule in the Levant in the second century BCE.Footnote 31

Countering the Arguments Against Jaubert’s Hypothesis

Wacholder and Wacholder’s central rebuttal of Jaubert’s thesis concerned her theory of liturgical days and sabbath avoidance. They contended that the days of the month found in the Bible for the dating of events could be accounted for by probability. They drew up a list of 60 dated events, which they numbered (Table II in their article),Footnote 32 and they posited that the dates could be explained by “biblical numerology.” This is a “preference” in the Bible for certain days of the month, rather than a fixed-date calendar with events taking place on particular days of the week to avoid the sabbath.Footnote 33 The authors gave as examples the first, tenth, fifteenth and the twenty-fourth of the month, as the “most popular.”Footnote 34 They argued that this predilection explains the proposed calendrical phenomenon described by Jaubert, stating: “Her reasoning was fallacious because most of the favoured biblical dates when translated into sectarian reckoning are excluded by arithmetic definition from occurring on the Sabbath. Jaubert had assigned a religious bias to an arithmetic rule.”Footnote 35 Wacholder and Wacholder presented the Hebrew Bible as a single document rather than as a work of ancient literature written, changed and compiled over several hundred years. Their contention that the “biblical chroniclers’ preference for certain days of the month over others” presupposes a natural mathematical bias towards certain numbers without any chronological context. The authors’ “arithmetic rule” proposal intimates that the “biblical chroniclers’ ” apparent preferences for certain dates were not chosen deliberately.

Furthermore, Wacholder and Wacholder’s list of dated biblical events includes dates outside the Hexateuch. Although the authors acknowledged this, they still included “not only. . . all the dates analyzed by Jaubert, but also those from Jeremiah, Haggai, and Esther [and also 2 Kings, Ezekiel, Ezra, Nehemiah, Zechariah, Daniel and 2 Chronicles] that Jaubert disqualified because they followed foreign reckoning.”Footnote 36 It is extremely methodologically problematic, when attempting to disprove a scholarly thesis that explicitly excludes certain material from its data and explains why it is doing so, to include these data, and then to argue against them.

Beckwith also included all the biblical books with dated events and reached a somewhat different conclusion. His data showed that the biblical narratives precluded activities that took place on the weekly sabbath, except for five events in Esther 9, discussed below. He found that Wednesdays, Fridays and Sundays were favoured days; however, he did not break down his final tally of results into dates in the Hexateuch and those from the other books.Footnote 37 Before discussing the issue of probability and its validity in the context defined by Wacholder and Wacholder, we need to look at the material that Jaubert disregarded in some detail.

The Case of the Exceptions to the Jubilees-Qumran Calendar

Jaubert herself highlighted different calendrical references in the Bible because she found that different textual layers contained dates with features other than those of the 364-day year. These were, specifically, 1 Kings, which employs “very ancient names of the month used in Israel: Ziv, [1 Kgs 6:1, 37] Ethanim [1 Kgs 8:2] and Bul [1 Kgs: 6:37]”Footnote 38 (these texts were not included in Wacholder and Wacholder’s Table II), and the books written in the Persian period that wholly or partly contained dates with the Babylonian month-names. These dates were included in Wacholder and Wacholder’s Table II, and they were equated to the numerical months of the 364-day year calendar. One such date, in Esth 9:15, troubled Jaubert because the fourteenth day of Adar, the twelfth month, would be a sabbath if all the dates containing Babylonian month names were equated with the corresponding numerical months in the 364-day year calendar.Footnote 39

Intriguingly, Jaubert wrote that the dates in Zech 1:7 [the twenty-fourth day of the eleventh month, Shebat] and 7:1 [the fourth day of the ninth month, Kislev] “are fully in harmony” with the calendar [respectively, Sunday and Wednesday in the 364-day year calendar].Footnote 40 Jaubert also excluded 2 Chr 3:2 because it interprets the insecure date in the month of Ziv, in 1 Kgs 6:1, discussed below.Footnote 41 Although Wacholder and Wacholder acknowledged the points to which Jaubert drew attention, they stated in their Tables II A–B: “. . . the intention of these tables is not to determine the biblical calendars that lie behind the biblical dates, but only to show that the dates of Scripture cannot be harmonised with Jaubert’s hypothesis.”Footnote 42

Several scholars, including Davies, Beckwith and Jacobus, have argued that the dates in the Book of Esther cannot belong to the 364-day year calendar.Footnote 43 Beckwith suggested that the different calendar in Esther may have been the reason that the book was possibly rejected at Qumran.Footnote 44 While some scholars are of the opinion that the Book of Esther was, in fact, known at Qumran,Footnote 45 its absence does not constitute conclusive evidence either that it was not accepted, or that it was not accepted because it had a different calendar. The argument that the calendar in Esther does not adhere to the 364-day year calendar is part of a separate study; it is not a basis from which to invalidate Jaubert’s hypothesis.

With regards to 2 Chr 3:2, the problem was discussed further by Jaubert herself, but not in any great depth. She wrote: “Only one date might weaken our hypothesis. In II Par., 3,2, Solomon begins the construction of the Temple on 2/II, [in the Masoretic Text] which is a sabbath day [in the 364-day year calendar]. However, though the mention of Month II is certain, the ‘second day’ is missing in three Hebrew [sic] manuscripts, LXX, the Vulgate and the Syriac.”Footnote 46

Wacholder and Wacholder commented: “Jaubert notes but qualifies this exception.”Footnote 47 However, the qualification is factually valid, rather than part of a hypothesis. The problem is partially complicated because the commonly constructed date of the “second day,” in the MT is the grammatically unusual, or incorrect, “on the second” (![]() ) with the word “day” missing (instead of

) with the word “day” missing (instead of ![]() [on the second day]). Neither Jaubert, nor Wacholder and Wacholder comment on the implications of the use of the phrase

[on the second day]). Neither Jaubert, nor Wacholder and Wacholder comment on the implications of the use of the phrase ![]() (on the second).Footnote 48 Furthermore, and possibly connected to this scribal enigma, they do not mention that this passage appears to be based on 1 Kgs 6:1, which dates the reconstruction of the Temple to the month of Ziv (the second month) without a day of the month.

(on the second).Footnote 48 Furthermore, and possibly connected to this scribal enigma, they do not mention that this passage appears to be based on 1 Kgs 6:1, which dates the reconstruction of the Temple to the month of Ziv (the second month) without a day of the month.

Since the day of the month does not exist in 1 Kgs 6:1, the second day of the month of Ziv may not equate to the second day of the second month in the 364-day year calendar. Therefore, the date, the second day of the second month (abbreviated to 2/II by Jaubert, see above), in MT 2 Chr 3:2 is misleading. It is, therefore, insecure to use MT 2 Chr 3:2 as an example of a valid exception because, 1) The date is not extant in all manuscripts; 2) it is grammatically anomalous; 3) the month name, Ziv, the second month, is not a numerical month; therefore, the date, the second day of the month (a possible gloss), should not be taken as equivalent to 2/II, which is a sabbath in the 364-day year calendar.

As well as including different dating systems, Wacholder and Wacholder directly converted the Babylonian month-names into numerical months without always clearly stating that these months were not numerical in the biblical text.Footnote 49 Beckwith also included dates in the prophetical books and the Writings in his surveys of the extent of the 364-day year calendar. However, he does not discuss the dated events in books with the Babylonian month-names, other than Esther. (In his tables he included the months in Esther as numerical months).Footnote 50

The Problem of Probability

Wacholder and Wacholder’s probability argument is inherently methodologically problematic, especially when applied to the number of possible dates from unknown and diverse types of source texts. The authors do not specify or distinguish the different literary and chronological strata in the Hebrew Bible, nor do they mention the various kinds of dating formulas that may suggest alternatives to the 364-day year calendar.

Neither does Wacholder and Wacholder’s thesis on biblical numerology include any contextual explanations. They did not advance a hypothesis of why “biblical numerology” exists, nor offer any comparative cultural or historical background to support this theory. They simply presented data as fact even though their tables do not unequivocally support their case.

Examples include the twenty-fourth of the month which belongs with the books that were not included in Jaubert’s thesis.Footnote 51 The most popular biblical date is the first of the month.Footnote 52 However, the first of the month may begin on the new waxing lunar phase in a lunisolar calendar, an early 365-day solar calendar, or a 364-day year calendar where the first day of the month need not coincide with the new crescent moon.Footnote 53 Using their own statistics, Martin G. Abegg points out that Wacholder and Wacholder’s data did not prove what they set out to show:

In an extensive review of Jaubert’s theory, B. Z. Wacholder suggests that the lack of sabbatical dates is to be explained by the Bible’s preference for certain days of the month over others rather than an avoidance of the Sabbath. However, his own figures (pp. 22–23 [Table II]) reveal that whereas it is possible for 43 per cent of numbers 1–31 to fall on a Sabbath in the 364-day calendar, only 18 per cent of the dated events occur on these dates. This phenomenon still suggests rather strongly that the preference is not only for certain numbered days of the month but particularly those that could never occur on Sabbath.Footnote 54

Hence, notwithstanding the precarious methodology itself and the fact that the authors examined most of the dates that they found in the Hebrew Bible, even though Jaubert did not include many of these dates in her hypothesis for reasons described above, Wacholder and Wacholder statistically failed to demonstrate that sabbaths were not avoided when events took place in the Bible. However, Abegg’s finding has not been used to the effect that perhaps it should have been.Footnote 55

The Ancient Calendars of Wacholder and Wacholder

In rejecting Jaubert’s theory that the Jubilees-Qumran calendar may be found in the Hebrew Bible, Wacholder and Wacholder proposed their own biblical calendar, or calendars. These were solar (365 days), and/or lunar (354 days consisting of twelve lunar months), or lunisolar (354 days of twelve lunar months with the addition of eleven days for a solar year of 365 days).Footnote 56

The second string of Wacholder and Wacholder’s argument harks back to their disagreement with SegalFootnote 57 as well as Jaubert, a position which held that the calendar in the Book of Jubilees was an ancient Jewish calendar that was displaced after the Exile (c. 598–538 BCE) by the lunisolar calendar. To concede the antiquity of the 364-day calendar would be a step against their rival theory that there were alternative calendars, or another calendar, in the Bible.

Their argument in favour of a solar and/or lunar calendar (or a lunisolar) in the Bible is based on three “indications”: The first is Gen 1:14–17, the role of the two great luminaries to regulate days, seasons and years: “As read by the Pharisees and their rabbinic successors, this directive [Gen 1:14–17] required a reckoning that combined the orbits of the two luminaries, that is, the lunisolar reckoning of the Mesopotamian and Jewish calendar.”Footnote 58 In contrast to the rabbinical interpretation, in the authors’ view, the “sectarian paraphrases” [this probably refers to Jub. 2:8–9] of the biblical fourth day of Creation “associate the sun and the moon with the beginning of time qualified by the apparent proviso that makes the orbit of the sun paramount over that of the moon.”Footnote 59

Yet this argument does not refute Jaubert’s hypothesis: she made the same point, observing: “. . . it seems very likely that Jubilees represents an extremist reaction advocating a return to strict orthodoxy in the face of a fairly general lunar practice.”Footnote 60 She suggested that Gen 1:14 in not mentioning lunar months was not incompatible with the 364-day year calendar for time-reckoning in Jub. 2:8–9.Footnote 61

Leviticus 23:32: The Day of Atonement

Their third observation in this section of Wacholder and Wacholder’s essay is the case of Lev 23:32. Here, the authors interpret the “Sabbath of rest” of the Day of Atonement (“on the ninth of the month at evening, from evening to evening you shall observe your Sabbath”) to necessarily mean any day of the week. Applied to the 364-day year calendar, the Day of Atonement on the tenth of the seventh month, in a sunset-to-sunset reckoning, would begin on Thursday at twilight and end on Friday at twilight. Wacholder and Wacholder attempt to rule out the fixed 364-day year calendar in this passage on the basis that it would be unlikely that Yom Kippur would be permanently adjacent to the sabbath, that is, on Friday.Footnote 62

The situation of the Day of Atonement occurring on a Friday or Sunday in the calendar is prevented in rabbinical Judaism through a system of calendrical “postponements,”Footnote 63 but these did not exist in the first century CE. The Talmud is clear that in the first centuries CE the festival could occur on a Friday or a Sunday (thereby having two days of rest together) because the rabbinical authorities were concerned about it.Footnote 64 Jewish legal discussions in the late third century and early fourth century show that they were aware that this had the potential to cause hardshipFootnote 65 as well as the accidental desecration of the weekly sabbath.Footnote 66 Contrary to Wacholder and Wacholder’s point, if the Day of Atonement fell on a Friday, the weekly sabbath would commence as usual with specific sabbath rituals and sabbath laws.Footnote 67 The Day of Atonement and the weekly sabbath were not merged into a single continuous sabbath when they occurred consecutively (in a presumed lunisolar calendar), as Wacholder and Wacholder assert.

Intercalation and the Sectarian Utopian Calendar

A central problem with the 364-day year calendar is that it falls short of the tropical year of just over 365 days by about 1.24 days annually. No method of making up this shortfall by intercalating a leap month every three years, for example, is indicated in the Qumran texts. Jaubert observed that due to the unsolved problem of whether the 364-day year calendar was intercalated, the festivals would go out of alignment with the seasons.Footnote 68 She commented, “as regards the intercalations in this calendar we are reduced to conjecture. The difficulty has not yet been solved.”Footnote 69

The issue remains a focus of discussion in Qumran calendrical studies. Uwe Glessmer, for one, suggested two mathematically possible methods of intercalation; however, despite further publications in the field no textual evidence for any kind of intercalary procedure has been found.Footnote 70 Wacholder and Wacholder concluded that the fixed 364-day year calendar must be sectarian because it was unlikely to have been intercalated.Footnote 71 They and other scholars have argued that the 364-day year calendar was ideal or utopian.Footnote 72 Drawing on Jub. 6:32, which is generally interpreted as a statement against any form of intercalation, the Wacholder and Wacholder case was that calendrical correction would “irremediably disturb the constant refrain of the sabbatical and seasonal divisions of time.. . . what made the sectarian calendar sectarian was precisely its utopian pattern.”Footnote 73 The utopian argument is not new; Barthélémy anticipated it and argued in favour of an intercalated model prior to the development of Jaubert’s thesis.Footnote 74 Moreover, Jub. 6:32 has not been found among the Hebrew fragments of Jubilees at Qumran; it is only known in the Ethiopic manuscripts. The possible evidence for a 364-day year calendar in Jubilees, Jub. 2:8–10, does not preclude a system of leap days or weeks.

The date range of the calendrical texts from Qumran containing the 364-day year calendar is extensive. The earliest of the calendars of the priestly courses pre-date the proposed settlement at Qumran—4Q320 is dated paleographically to the end of the second century BCE.Footnote 75 Not all of the texts containing the calendar have “sectarian” features. These include the Commentary on Genesis A (4Q252), which has the only full reference in the Dead Sea Scrolls to a complete year of 364 days (4Q252 1 ii 3) (discussed below) and is dated to the first century CE.Footnote 76 A copy of the liturgical composition, the Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice known from copies in Cave 4 (4Q400–4Q407) and Cave 11 (11Q17), which employs a 364-day calendar template, was also found in Masada (Mas 1K), dated to the mid-first century.Footnote 77 This textual chronology suggests that there may have been a broad, long-lived use, or preserved knowledge, of this calendar within late Second Temple Judaism. If the 364-day fixed calendar had been employed as a liturgical calendar for more than 100 to 150 years, its users would have noticed that after 70 years Passover was occurring in the winter, and then 70 years later, in the summer.Footnote 78

In sum, the authors’ conclusion that the 364-day calendar is sectarian, and therefore, not, as Jaubert maintained, an ancient Jewish calendar designed for avoiding activities on the sabbath, is not demonstrated. They do not explain the reason for the occurrence of, or the comparative background of “biblical numerology.” Nor do they prove by invoking the theory of probability that particular days would not fall on the sabbath due to their arithmetic predisposition not to do so. Their argument that Lev 23:32 presupposes that the Day of Atonement could fall on any day of the week, thereby ruling out the 364-day year calendar, is not unequivocally proved by later rabbinical texts which presupposes that Yom Kippur can occur on Friday.

The refutation of Jaubert’s alleged “fallacy” about the days of the month and hence the days of the week and sabbath avoidance is based on different poles of argumentation: 1) all events occurring on biblical dates can be accounted for by the theory of probability (using different data to Jaubert’s), and therefore, biblical sabbath avoidance (if it existed), is an arithmetical given, not related to the 364-day calendar; and, 2) the 364-day calendar is a late sectarian creation that is utopian and not intercalated (as opposed to the astronomical biblical calendars unspecified by the authors). Evidence for 1) focusing on the Hexateuch only, as per Jaubert’s theory, has not been produced; and 2) the assertion that the 364-day calendar (whether ancient or sectarian) was utopian and not used in practice has not been proved either way.

The Flood Calendar Discussion

Wacholder and Wacholder discussed the biblical Flood calendar of Gen 7:6–8:14 in relation to Jaubert’s thesis, Jubilees, and 4Q252.Footnote 79 The authors argued that according to early rabbinical commentatorsFootnote 80 the composer of the biblical text reckoned that the chronology of the deluge was 365 days, and, furthermore, that this year-length was understood by the composers of Jubilees and the 4Q252 Flood calendar. Their reasoning was that the seventeenth of the second month in the 600th year of Noah’s life when the Flood began (Gen 7:11) to the twenty-seventh of the second month when the earth was dry (Gen 8:14) comprised 12 lunar months. This consisted of one year of 354 days with the addition of 11 days to adjust to a solar year, counting exclusively (that is, not including the first day of the Flood).Footnote 81 Some other commentators state that the duration of the Flood is 12 lunar months, plus 10 days (counting inclusively), equivalent to a solar year of 364 days.Footnote 82

For Wacholder and Wacholder the author of the Flood calendar in Jubilees polemicized against the 365-day year, by making the Flood year one day less in the 364-day calendar (in Gen 8:14 the earth is dry on the twenty seventh of the second month).Footnote 83 In Jub. 5:31 the earth dries on 17/II but the egress from the ark has a different date from the drying of the earth on 27/II in Jub. 5:32.Footnote 84 Arguably, this does not prove that there was a polemic or that the biblical chronographer used a 365-day year since only the date, not the year-length, is specified in Gen 8:14. Much of this section of Wacholder and Wacholder’s article is a counterargument to VanderKam’s interpretation that the editor of Jubilees and the Flood calendar in Gen 7–8 “quite transparently intends a solar year of 364 days, not 365.. . . If the source used by P utilized lunar months [a 354-day year], then the period from II/17 to II/27 indicates a year of 364 days.”Footnote 85

Wacholder and Wacholder illustrated their point by appealing to 4Q252 which they claimed “dated the beginning of the flood as in Jubilees, but specified the sixteenth of month two as its end.”Footnote 86 This date would fall on the sabbath in the Jubilees calendar.Footnote 87 Wacholder and Wacholder’s reckoning of 17/II/600 to 16/II/601 in an inclusive count (364 days) is a possibility, but it is not certain that that is what the text does in this case. The Qumran text 4Q252 1 i 3b–4 agrees with Jub. 5.23 and Gen 7:11 on the beginning of the Flood on 17/II. However, the text does not mention 16/II at all (this date seems to be an error by Wacholder and Wacholder), one year later, but 17/II (4Q252 1 ii 1–3) as the date that the earth dried, apparently the same date as the disembarkation from the ark.

Wacholder and Wacholder’s incorrect contention that the Qumran text states that the Flood ended on 16/II is curious; as noted above, no referenced source for this manuscript is given. Counting exclusively from the dates given in 4Q252, 17/II/600 to 17/II/601 constitutes 364 days.Footnote 88 Counting inclusively from the beginning of the Flood to 17/II/601 is 365 days, but the Qumran calendar specifies that the duration of the deluge is 364 days (see below).Footnote 89

The Qumran Flood Calendar

Moving onto the 4QCommGen A itself, it shall now be argued that no conclusions about the method of reckoning its calendar can be drawn from using either a system of inclusive or exclusive counting in 4Q252 as both methods are represented in the text. In the only unbroken reference to the 364-day “complete year” (4Q252 1 ii 3) in the Qumran manuscript (and in all the Dead Sea Scrolls, as mentioned), the text states that the earth dried on the first day of the week (Sunday), on 17/II/601, and that Noah disembarked on the same day. The text, thus, has a different view to MT Gen 8:14–15 in which the earth dried on 27/II, while the date that Noah disembarked is not stated. (In contrast, in Jub. 5.30, the earth dried on 17/II; in Jub. 5.32, the animals left the ark on 27/II; and in Jub. 6.1, Noah disembarked on 1/III).

The translation and a commentary to the calendar of 4Q252 is as follows:

1. in the six hundred and first year of Noah’s life, and on the seventeenth day of the second month

2. the earth dried up, on the first (day) of the week [Sunday]. On that day, Noah went forth from the ark, at the end of a

3. complete year of 364 days, on the first (day) of the week.. . . (4Q252 1 col ii)Footnote 90

The Flood calendar in 4Q Commentary on Genesis A (4Q252) 1 i 3b–ii, 5 clarifies the dates and the number of the days between dated events with the numerical days of the week. The chronology of the Flood with the dates and days of the week in 4Q252 in relation to the dates in the biblical text (where there are no days of the week) is given below (see also Appendix: Noah’s Flood Calendar, 4Q252, for the tabular form). It will now be shown that, in addition to the days of the week, the author of the Qumran text reckoned the chronology of the deluge text using both inclusive and exclusive counting between the different calendrical points.Footnote 91 The copyist counted the days of the month inclusively (except 14–17/II/600) between the stated events up until Noah opens the window of the ark; thereafter, the days between the events are counted exclusively. (The chronology of the Flood differs in the Septuagint and is not represented in the 4Q252 Flood calendar).Footnote 92

Days of the Week and the Calculated Calendar in 4QCommGen A (4Q252)

17/II/600 (“On the first [day] of the week.” [Sunday]): The rains begin for 40 days and 40 nights (4Q252 1 i 3b–6 from 17/II/600; the date is the same as Gen 7:11–12).

26/III/600 (“On the fifth day of the week.” [Thursday]): The end of 40 days. This is inclusive counting from 17/II until 26/III/600 (4Q252 1 i 6–7a).Footnote 93 The date for the rains to finish falling after 40 days and 40 nights is not given in Genesis. In Gen 7:24 (4Q252 1 i 7) the waters prevailed upon the earth for 150 days. The Qumran dates subsume the 40 days into the 150 days, rather than treating the time periods consecutively. It thereby exegetes the ambiguity in the biblical text.Footnote 94

14/VII/600 (“The third [day] of the week.” [Tuesday]): The waters were mighty on the earth for 150 days until 14/VII (4Q252 1 i 7–8). This represents inclusive counting from 17/II/600. The date 14/VII for the beginning of the diminishing waters is not given in Gen 8:3.

17/VII/600 (“Sixth Day” [Friday]): The ark comes to rest. There is explicit exclusive counting from 14/II: “two days, Day Four and Day Five, and on the Sixth Day the ark came to rest on the mountains of Hurarat” (4Q252 1 i 9b–10; compare, Gen 7:24, 8:3–4). The date of 17/VII for the ark coming rest on the mountains of Ararat is also given in Gen 8:4.Footnote 95

1/X/600 (“Fourth day of the week.” [Wednesday]): the tops of the mountains appeared (4Q252 1 i 11–12). The date of 1/X/600 is the same as that in Gen 8:5 (cf. LXX Gen 8:5, this date is 1/XIFootnote 96). The number of days from 17/VII is not specified in 4Q252, or in Genesis.

10/XI/600 (“First day of the week.” [Sunday]): Noah opened the window of the ark at the end of 40 days. This is inclusive counting of 40 days after the mountain peaks appeared on 1/X/600 (4Q252 1 i 12–14b; no date is given in Gen 8:6). This is a numeric mirror-image, or “palistrophic literary structure” to the inclusive count of 40 days and nights of rain from 17/II–26/III in a year beginning in Month I and ending in Month XII.Footnote 97 It is the last inclusive count.

(17/XI/600) (No date given. [Sunday]): the first flight of the dove. There is exclusive counting of seven days from the opening of the ark window on 10/XI (4Q252 1 i 14b–15a); no date or timescale is specified in 4Q252, following Gen 8:8–9. The Qumran text has interpreted the biblical text to mean that the first flight of the dove did not take place on the same day that Noah opened the window of the ark. The ancient author has reached this date by calculating backwards. The author has separated by one month the third flight of the dove on 1/XII/600 from Noah removing the cover of the ark on 1/I 601, see below.

24/XI/600 (“The first [day] of the week.” [Sunday]): the second flight of the dove. There is exclusive counting of seven days from the first flight (4Q252 1 i 15b–17a) (“And he again waited a[nother] seven days”). Following Gen 8:10, which does not contain a date, 4Q252 interprets the date of the first flight of the dove as 17/XI.

1/XII/600 (“The first day of the week.” [Sunday]): the third flight of the dove. This constitutes exclusive counting of seven days from the second flight (4Q252 1 i 18–20). Gen 8:12: “he again waited yet another seven days.” No date for the third flight of the dove is given in Genesis.

1/I/601 (“Fourth day of the week.” [Wednesday]): At the end of 3[1] daysFootnote 98 following the third flight of the dove Noah removes the cover of the ark, and the land surface is dry (4Q252 1 i 20b–ii 1a). This constitutes exclusive counting of 3[1] days from the no-return flight of the dove.Footnote 99 The date of 1/I/601 is given in Gen 8:13 when the earth began to dry and Noah removed the ark’s covering.

17/II/601 (“The first day of the week.” [Sunday]): The dried earth and the disembarkation from the ark. The date of 27/II/601 (Wednesday) is given in Gen 8:14 for the dried earth; no biblical date is given for leaving the ark. As mentioned, 4Q252 interprets the two events as occurring on the same day, 10 days earlier, at the end of a complete year of 364 days (4Q252 1 ii 1–3) by counting exclusively from 17/II/600.

At first glance, the remarkable Flood calendar from Qumran apparently supports Jaubert’s hypothesis that activities take place on Sunday, Wednesday and Friday, and that no events take place on the sabbath, in the biblical text.Footnote 100 Although Jaubert had no knowledge of 4Q252, she clarified the days of the week in the Flood calendar in Genesis in a similar manner to the Qumran text, albeit not as thoroughly as the ancient authors (that is, a reconstruction day, by day). Counting exclusively, Jaubert interpreted the end of 150 days of receding waters (Gen 8:3) on 15/VII, Wednesday, and the ark coming to rest on the mountains of Ararat (Gen 8:4) on 17/VII, Friday, “two days later.”Footnote 101

In contrast, the Qumran text counts inclusively from the beginning of the deluge up until and including Noah opening the window of the ark (on 10/XI, the sixth day of the week, Friday [Gen 8:6]). Hence, in 4Q252, the waters diminish on 14/VII, on the third day of the week, Tuesday (see above), counting inclusively.Footnote 102 However, according to both Jaubert and the author of the Qumran Flood calendar, the ark balances on receding waters on Wednesday and Thursday at the end of the 150 days, which is not in the biblical text, and it comes to rest on the sixth day of the week, Friday (Gen 8:3–4).

The mixture of inclusive and exclusive counting in the Qumran Flood narrative means that, ironically, the 364-day year calendar cannot be applied to the biblical narrative in exactly the way that Jaubert had calculated. On the other hand, while modern Western scholars may use exclusive counting in a consistent manner, the same may not have been true in antiquity. As argued by VanderKam in his reassessment of Jaubert’ hypothesis regarding rival theories of the year-length in the biblical Flood chronology, “To say that he [the biblical author] means 365 is to misunderstand the manner in which such dates are expressed in a literary text of this sort; it is to expect of it a precision that it lacks.”Footnote 103

The Theory of the Antiquity of the 364-Day Year Calendar Revisited

In summary, Wacholder and Wacholder’s arguments, with our counterarguments in parentheses, are as follows.

1) Activities do not take occur on Wednesday, Friday and Sunday in every biblical Book. (Jaubert applied her hypothesis to the Hexateuch only, and she, arguably, supported her case for the “liturgical days,” albeit, unknowingly, without modern arithmetical precision).

2) There are other biblical calendars which are solar, lunar, or lunisolar. (The authors neither clarified nor demonstrated this point).

3) All the dates in the Hebrew Bible can be replicated by probability. (This argument does not consider the chronological layers of biblical textual strata, nor the possible calendrical variety).

4) The 364-day calendar is sectarian and utopian and not ancient, or biblical; they conclude the article by stating that the sectarians made “the ultimate miscalculation.”Footnote 104 (If the calendar was utopian then the sectarians would not have been troubled by the “miscalculation” because they did not put it into practice. As shown by the Qumran manuscripts to which they refer, this conclusion does not match the longevity of the 364-day year calendar in Jewish circles and the variety of texts in which it occurs).

5) Finally, Wacholder and Wacholder argued that the Flood calendar in Gen 7–8 conformed to the 365-day calendar and that this was understood by the authors of Jubilees and 4Q252, in agreement with rabbinical interpretations.Footnote 105 (As noted above, they used a date for the exit from the ark, 16/II/601, that did not exist in the Qumran text, for which no source was given, and they assumed that there was consistent exclusive counting).

The Qumran deluge chronology limits the start of movements and actions to Wednesday, Friday and Sunday according to the 364-day year calendar, in keeping with Jaubert’s hypothesis. Yet, Jaubert’s interpretation of the Flood calendar did not provide evidence of a biblical calendar in terms that we understand. Despite the Jaubertian closeness to 4Q252, the Qumran text’s arithmetical template is based on a mixture of inclusive and exclusive counting of the number of days between events. One may concur with VanderKam that we should not apply a consistent mathematical mindset to the compilers of the Qumran deluge chronology. Hence, the question of Jaubert’s biblical liturgical days, since they corresponded to the calculations in 4Q252, and the data given in Gen 7–8, should not be dismissed.

In conclusion, Wacholder and Wacholder did not prove that Jaubert’s hypothesis is a “fallacy” as they claim, and that description in the article’s title is unwarranted. As outlined above, many of their arguments are problematic. Although they did not offer any evidence for any astronomical calendars in the Bible, nor did they demonstrate whether the sabbath was avoided for activities according to any of these alleged calendars, the authors may have had a possible case to support their suggestion that there are such calendars in the Hebrew Bible.

The question of the extent and the nature of biblical calendars remains open on the scholarly table. This would include Jaubert’s hypothesis that an ancient calendar structured around the abstinence of travel on the sabbath was preserved by a priestly group, or groups, until the late Second Temple period. Wacholder and Wacholder did not provide the data or evidence to support their contention that the 364-day year calendar was a late Second Temple sectarian innovation.

Appendix: Noah’s Flood Calendar, 4Q252

Noah’s 600th year 601st year