Introduction

Parliamentary minority rights are a core element of representative democracy but also a double‐edged sword. They are essential for democratic competition because they guarantee that competing views are voiced in the legislative process and can subsequently affect electoral decisions. At the same time, minorities can use these rights to obstruct the majority's policy agenda and thus partly negate the outcome of electoral competition. Accordingly, parliamentary majorities have incentives to curb minority rights if they experience or fear obstruction. The best‐known example of such conflicts over parliamentary minority rights is the century‐long attempt to limit filibusters in the United States Senate (Wawro & Schickler Reference Wawro and Schickler2006; Koger Reference Koger2010). However, similar conflicts and associated institutional reforms exist outside the United States. The British House of Commons witnessed enduring minority obstruction in the late nineteenth century, which was ultimately resolved by restricting minority rights in the chamber (Redlich Reference Redlich1903; Dion Reference Dion1997: Chapter 8; Koß Reference Koß2015; Goet et al. Reference Goet, Fleming and Zubek2019). More recently, the 1958 constitution of the Fifth French Republic massively restricted minority rights to overcome cabinet instability (Huber Reference Huber1996), and the Italian parliament abolished secret voting on legislation in 1988 to curb the power of intra‐party minorities (Hine Reference Hine1993).

These examples, as well as theoretical work in the ‘institutions‐as‐equilibrium’ tradition, suggest that parliamentary actors strategically redesign minority rights in order to achieve their substantive goals and that these reforms can have far‐reaching consequences for the functioning of legislatures and representative democracies more generally (e.g., Riker Reference Riker1980; Calvert Reference Calvert, Knight and Sened1995; Diermeier & Krehbiel Reference Diermeier and Krehbiel2003; Diermeier et al. Reference Diermeier, Prato and Vlaicu2015; Shepsle Reference Shepsle2017). Empirically, the suppression of minority rights in the United States House of Representatives can indeed be explained by the policy interests of the decisive parliamentary actors, be it the majority party (Binder Reference Binder1996; Dion Reference Dion1997; Cox & McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005) or the median legislator (Schickler Reference Schickler2000).

However, do these findings travel to parliaments outside the United States? While minority rights can constrain majorities in any parliament, there are reasons to expect that it is more difficult for majorities in European democracies to redesign rules in their own favour. Most cabinets in European multiparty systems are coalitions or minority cabinets so that rule changes require the consent of multiple actors. The institutional preferences of these actors are not necessarily aligned because coalitions are typically formed based on policy agreement, not agreement on institutional reform, and because some coalition members may anticipate losing majority status whereas others expect to continue as cabinet parties in the future. Thus, the lines of conflict regarding institutional reforms are less clear‐cut in European parliaments than the straightforward confrontation between the majority party and the minority party in Congress. Furthermore, the stock of minority rights varies tremendously across European parliaments and is generally lower than in Congress. This raises the theoretical question of how differences in the institutional status quo affects reform dynamics.

Empirically, we have little systematic evidence on whether and why minority rights are curbed in legislatures outside the United States. The few available comparative studies focus on cross‐sectional variation without analysing change (Taylor Reference Taylor2006), use highly aggregated data including reforms that are not driven by actors’ attempts to gain an advantage over their competitors (Sieberer et al. Reference Sieberer, Müller and Heller2011, Reference Sieberer, Meißner, Keh and Müller2016), or focus on a small number of countries and institutional rules (Koß Reference Koß2015). Single‐country studies are mostly descriptive; if offering inductive explanations, they predominantly stress the functional need for reform and consensual decisions by all actors in parliament rather than the competitive motives highlighted by research on Congress (e.g., Thaysen Reference Thaysen1972; Norton Reference Norton2001; Capano & Giuliani Reference Capano and Giuliani2003; Leston‐Bandeira & Freire Reference Leston‐Bandeira and Freire2003; Murphy Reference Murphy2006; Flinders Reference Flinders2007; but see Goet et al. Reference Goet, Fleming and Zubek2019; Goet Reference Goet2019, for competition‐based arguments similar to ours).

In contrast to much of this case study literature, we claim that reforms of parliamentary minority rights in Europe can also be explained by competitive actor behaviour. The crucial parameters of our explanation are changes in policy conflict between parliamentary majority and minority, on the one hand, and the current level of minority rights in the chamber (i.e., the institutional status quo), on the other.Footnote 1 Parliamentary majorities resort to institutional reforms if they fear or experience that existing minority rights massively hinder them in implementing their policy agenda. Accordingly, a suppression of minority rights should be more likely if the institutional status quo provides the minority with ample institutional powers and opposition parties have strong incentives to obstruct government initiatives. While we build on congressional research with regard to the role of policy conflict (especially Binder Reference Binder1996Reference Binder1997; Wawro & Schickler Reference Wawro and Schickler2006), our claim that this effect is conditional on the institutional status quo is theoretically and empirically novel.

Our quantitative analysis of a unique dataset containing all changes to parliamentary standing orders in 13 European democracies from 1945 until 2010 provides strong support for our theoretical argument. Reforms suppressing minority rights are substantially and significantly more likely if the policy conflict between government and opposition increases and if the government pursues a more ambitious policy agenda. In line with our interactive hypothesis, these effects are considerably stronger if the institutional status quo is more minority‐friendly. Our findings demonstrate the relevance of policy conflict for institutional reforms in European parliaments, provide novel empirical support for theoretical arguments that conceptualise institutional change as the outcome of competition over substantive goals, and extend this argument theoretically by stressing the importance of the institutional status quo for actors’ decisions to seek institutional reform.

How policy conflict ‘goes institutional’: Theory and hypotheses

Institutionalised minority rights are a universal feature of democratic legislatures. From a rational choice perspective, such rights exist because they serve parliamentary actors, including the current majority. For the majority, minority rights are means for credible commitment in policy making and in bargaining with actors outside the chamber (North & Weingast Reference North and Weingast1989; Diermeier & Myerson Reference Diermeier and Myerson1999). Furthermore, they can serve as insurance against a future loss of power if subsequent majorities honour the same rights based on a tit‐for‐tat strategy (Axelrod Reference Axelrod2006). Minority rights also increase the legitimacy of parliamentary decisions among current losers and constitute a necessary basis for democratic competition more broadly (Dahl Reference Dahl1971; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson2005; Christiano Reference Christiano2008). While this system‐level explanation is often framed in normative terms, it can be reconstructed as a long‐term rational strategy of political actors seeking to stabilise the institutional context in which they operate. Given these benefits, it is not surprising that parliamentary majorities generally accept some constraint by minority rights.

However, minority rights can also be used for obstructive purposes (Humphries Reference Humphries1991; Müller & Sieberer Reference Müller, Sieberer, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014; Bell Reference Bell2018) and thus hurt the parliamentary majority, which we assume is policy‐motivated (Laver & Schofield Reference Laver and Schofield1990: Chapter 3). Parliamentary procedures often give minorities influence over various aspects of parliamentary business such as setting the plenary agenda (Döring Reference Döring and Döring1995; Cox & McCubbins Reference Cox, McCubbins, Schickler and Lee2011), introducing bills and amendments (Heller Reference Heller2001), voicing concerns in speeches and questions (Russo & Wiberg Reference Russo and Wiberg2010; Proksch & Slapin Reference Proksch and Slapin2015; Bäck & Debus Reference Bäck and Debus2016), and staffing leadership positions in parliament (Carroll et al. Reference Carroll, Cox and Pachón2006).Footnote 2 Determined minorities can employ these rights to block or delay decisions and to force the government to spend precious time debating issues it would rather avoid. If used fully, minorities can turn generally accepted rights into instruments of obstruction – for example, by flooding the agenda with bills and amendments, engaging in extended speeches (filibusters), or tabling large numbers of questions. Even if such instruments are limited by quotas, the power to delay in combination with the ubiquitous scarcity of plenary time enables the minority to block parts of the majority's agenda or to extract policy concessions in exchange for ending obstruction (Fong & Krehbiel Reference Fong and Krehbiel2018).

Minority rights thus affect legislative processes even without ‘excessive’ use. Impatient and ambitious majorities can try to circumvent established minority rights to speed up business and pass their agenda. In practice, these two scenarios (obstruction by the minority and speedup by the majority) often blur because the threshold where a ‘normal’ use of minority rights turns into obstruction defies an objective definition.Footnote 3 Due to this inherent ambiguity, we sidestep this conceptual distinction. Instead, we argue from the perspective of government parties that typically dominate parliamentary outcomes. We focus on conditions under which the majority perceives minority rights as an obstacle to reaching its substantive goals, but explicitly leave open the question whether an outside observer would classify the behaviour of the minority as obstructive or consider anticipated obstruction plausible.

Given the value and potential dangers of minority rights, parliamentary majorities evaluate whether to pursue their substantive goals within existing parliamentary rules or to alter these rules in their favour. In line with the rational choice notion of institutions as equilibria (Calvert Reference Calvert, Knight and Sened1995; Diermeier & Krehbiel Reference Diermeier and Krehbiel2003), we assume that actors compare the anticipated effects of the institutional status quo and possible alternatives for reaching their substantive goals while taking into account the costs of reform and second‐order institutions that regulate how institutional rules can be changed (see also Sieberer et al. Reference Sieberer, Müller and Heller2011; Sieberer & Müller Reference Sieberer and Müller2015).

Thus, the incentives of a policy‐oriented governing majority to restrict minority rights depend on the interaction of two conditions: the willingness of minorities to use these rights for obstructive purposes (Binder Reference Binder1996Reference Binder1997; Wawro & Schickler Reference Wawro and Schickler2006); and the current level of minority rights. Restricting should be more likely if opposition parties enjoy substantial minority rights and government parties experience or at least fear that these rights are used to obstruct government policy making. Under these circumstances, a curbing of minority rights promises relevant policy gains that could not be realised without it. However, the majority must also consider the costs of institutional reforms, which include transaction costs (i.e., the effort required to develop and implement new rules) (Cox Reference Cox2000), and electoral costs that stem from negative popular reactions to reforms (Norton Reference Norton2001).Footnote 4 Given the importance of parliamentary minority rights for political competition and the legitimacy of parliamentary decisions, the potential costs of curbing minority rights should be high. Thus, the benefits from institutional reform must be substantial to outweigh these costs, which explains why the basic configuration of minority rights as well as differences between countries are relatively stable (Norton Reference Norton2001; Shepsle Reference Shepsle, Weingast and Wittman2006). Our theoretical argument focuses primarily on reform incentives that derive from policy competition and the role of the institutional status quo. Thus, we treat reform costs as factors that have to be controlled for in order to validly assess the impact of reform incentives.

To test this general theoretical argument, we need to identify specific conditions under which majorities suffer or fear obstruction due to minority rights.Footnote 5 We argue that government parties will be more wary of this possibility under two conditions. First, the danger of obstruction increases with growing policy conflict between the government and opposition parties (for a parallel argument on conflict between majority and minority party in Congress, see Binder Reference Binder1996). Opposition parties that pursue very different policies than the government are more likely to use minority rights for obstructive purposes to impede government policies with which they strongly disagree. This danger of obstruction in turn provides governing parties with incentives to curb minority rights. Second, obstruction is more likely if government parties seek larger departures from the policy status quo – that is, pursue a more ambitious policy agenda – which again gives the majority incentives to reform minority rights in pursuit of their substantive policy goals (for a similar argument in the American context, see Wawro & Schickler Reference Wawro and Schickler2006).Footnote 6

In our institutions‐as‐equilibrium argument, institutional change is triggered by changes in these variables, not their absolute level. Thus, increasing conflict with the opposition and an increasingly ambitious policy agenda should give the government incentives to reform parliamentary rules in their favour. By contrast, a high but constant level of conflict and ambition should not trigger reforms because it has been priced into the institutional setting in the past. Government‐opposition conflict and government ambition both capture policy‐incentives of the majority to redesign minority rights; however, they are conceptually and empirically distinct. Policy conflict can change due to variation in the policy positions of any party in parliament (government or opposition). By contrast, changes in government ambition are tied exclusively to government changes (either regarding party composition or the policy positions of cabinet parties) because our measure introduced below equates the policy status quo with the position of the previous cabinet. Thus, the two variables can – and as we show below empirically do – vary independently.

Increased policy conflict between government and opposition and a more ambitious government agenda should positively affect the likelihood that minority rights are suppressed. However, the strength of these effects should be conditioned by the institutional status quo: If opposition parties have few means for obstruction, the government has little to fear even with high policy conflict and an ambitious agenda. Thus, potential benefits of reform are unlikely to outweigh reform costs, especially as further curbing already weak minority rights makes it easy for opposition parties to blame the government for violating democratic fairness norms. By contrast, incentives to engage in institutional reform become stronger the more power current rules grant to minority parties.Footnote 7 This theoretical argument on the conditioning effect of the institutional status quo is novel because the pertinent Congressional literature always assumes a sufficiently high level of minority rights that can hurt the majority (we thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out). Note also that minorities in European parliaments lack formal tools to block the reform of minority rights via obstruction (in contrast to the well‐known situation in the American Senate where minorities can use the filibuster to block restrictions of their rights; see Binder & Smith Reference Binder and Smith1997). Thus, the decision whether or not to curb minority rights is largely one taken by the majority alone.Footnote 8

Our theoretical argument leads to the following core hypotheses:

H1a: An increase in policy conflict between government and opposition parties increases the likelihood that minority rights are suppressed.

H1b: This effect becomes stronger the more minority‐friendly the institutional status quo.

H2a: A more ambitious government policy agenda increases the likelihood that minority rights are suppressed.

H2b: This effect becomes stronger the more minority‐friendly the institutional status quo.

We have derived these hypotheses informally starting from the assumption of parties as unitary actors (Laver & Schofield Reference Laver and Schofield1990). Interestingly, similar expectations follow from a formal model that explains the adoption of anti‐dilatory rules (i.e., a reduction of minorities’ rights to speak in the chamber) based on the cost‐benefit calculations of individual members of parliament (Goet Reference Goet2017). In Goet's theory, an over‐extraction of parliamentary time due to greater demands by a more diverse group of MPs fosters the creation of strong parties (see also Cox Reference Cox1987). These parties provide coordination among their own MPs and favour anti‐dilatory rules to protect their initiatives against filibuster by other parties. Individual MPs prefer anti‐dilatory reforms if they expect that their overall policy gain when their party can contain opposition influence via restrictive rules is larger than the gain from policy concessions they could individually extract by means of filibuster. This condition is most likely met for a majority of MPs when the polarisation between government and opposition increases. Thus, Goet's expectations, while derived very differently, closely match our hypotheses that ideological distance between government and opposition (which is closely related to polarisation) as well as government ambition (which gives the opposition incentives to obstruct) are drivers of restrictive reforms.

Our analysis has to control for potential confounders that relate to the majority's ability to achieve favoured outcomes via institutional change and to reform costs. Both factors can make majorities stick to established rules even though the policy‐based reform incentives we focus on are present. We control for two conditions that impede the ability of the majority to overcome minority obstruction by changing parliamentary rules. First, such reforms are less likely in the presence of extra‐parliamentary veto points (e.g., a second chamber, a powerful head of state, or a constitutional court) because these institutions potentially provide opposition parties with further means to block the majority's agenda. Thus, any benefits drawn from curbing minority rights in parliament could be reversed in other arenas (Sieberer Reference Sieberer2006; Sieberer & Müller Reference Sieberer and Müller2015).Footnote 9 Second, a suppression of minority rights becomes less likely if government parties cannot muster the necessary majority to change the rules without the consent of opposition parties, which depends on the combination of the government's seat share and majority requirement for rule changes.Footnote 10

Furthermore, the likelihood of institutional reforms should decrease with reform costs, which can be divided into transaction costs from the reform process and electoral costs resulting from negative reactions by voters. Unfortunately, we lack direct measures for these costs across time and space and thus have to rely on proxy measures. One proxy for transaction costs is the fragmentation of the parliamentary party system because higher fragmentation leads to a more complex bargaining situation in parliament. A second proxy variable distinguishes between coalition and single‐party cabinets; coalitions face higher reform costs because coalition partners may have different views on minority rights – for example, because they differ in size and their prospects of continued government participation.Footnote 11 Electoral costs are even more difficult to capture because no data is available on voters’ opinions on parliamentary rule changes. However, the electoral costs argument presupposes that voters sanction the government at all, which is approximated by electoral volatility. Thus, we use this variable as (an admittedly imperfect) proxy for electoral costs.Footnote 12

Research design and data

We test our theoretical argument with a novel dataset that comprises all changes in the parliamentary standing orders of the lower houses of 13 parliamentary democracies in Western Europe since 1945 (or the start of the current democratic regime) until 1 January 2010 (for details on the dataset, see Sieberer et al. Reference Sieberer, Meißner, Keh and Müller2016).Footnote 13 The countries covered are: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg (from 1965 due to missing data for earlier periods), the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal (from 1977), Spain (from 1977), Sweden and the United Kingdom. By including parliaments of varying strength (Sieberer Reference Sieberer2011), our case selection avoids imposing strong scope conditions. We focus on parliamentary standing orders because they typically contain the largest share of parliamentary rules and can be reformed by parliamentary actors without the involvement of external actors like heads of state (Sieberer et al. Reference Sieberer, Meißner, Keh and Müller2016). Furthermore, we focus on formal rules (rather than norms and informal practices) because formal rights are enforceable in cases of conflict and can be measured reliably over extended periods of time and across multiple countries (Müller & Sieberer Reference Müller, Sieberer, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014).Footnote 14

Our theoretical argument applies to distributive institutional reforms that improve the position of some actors (in our case, the governing majority) at the expense of others. Thus, our analysis ignores other types of reform such as Pareto‐efficient changes that are in the interest of all actors (on the distinction between efficient and distributive reforms, see Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1990: Chapter 4) and other distributive conflicts such as the centralisation of power between party leaders and backbenchers (Keh Reference Keh2015; Proksch & Slapin Reference Proksch and Slapin2015: Chapter 4). This focus does not deny the existence of efficient reforms that respond to external trends such as an increased need for specialisation via committees (Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel1991; Sieberer et al. Reference Sieberer, Müller and Heller2011) or challenges of parliamentary influence due to Europeanisation (Auel & Benz Reference Auel and Benz2005; Winzen Reference Winzen2017). Furthermore, we acknowledge that single reforms can contain efficient and distributive elements when majorities include changes preferred by all actors or even some specific benefits for the minority to mask the suppression of other minority rights and maybe to gain support from at least some opposition parties (for examples, see Sieberer & Müller Reference Sieberer and Müller2015). Methodologically speaking, such mixed reforms introduce additional variation not associated with our core explanatory variables (‘noise’) and thus work against finding support for our hypotheses.

To measure our dependent variable, we have to identify whether and in what direction each reform changed minority rights. Doing so is complicated by the fact that parliamentary rules vary in institutional details that are crucial for turning instruments such as bills, amendments, speeches or parliamentary questions into means of obstruction. Political actors often show amazing creativity in employing rules in unexpected ways (Shepsle Reference Shepsle2017), and a minority deprived of some rights can use other instruments for the same obstructive purpose. Based on this substitutability, we assume that different minority rights can theoretically be summarised in a single dimension that captures the overall minority‐friendliness of parliamentary rules. Any change of parliamentary rules can be classified qualitatively as suppressing, expanding or not affecting minority rights.Footnote 15 Our argument here deals with the suppression of minority rights only; the extension of minority rights is discussed briefly in the conclusion.

To identify reforms that suppressed minority rights, human coders judged all changes from one version of the standing orders to the next on the sub‐paragraph level as (1) favouring the majority with regard to the distribution of power between majority and minority, (2) being neutral, or (3) favouring the minority. We used a multi‐stage process to ensure reliable and consistent coding across countries and time. In a first step, all changes of the rules were analysed by student assistants with the necessary language skills, usually native speakers, as most standing orders are only available in a country's official language. In a second step, the student assistants explained and discussed all changes that could broadly be interpreted as affecting the relationship between majority and minority with one of the authors. These two persons coded the change as favouring the majority, the minority or as being neutral. Whenever there was uncertainty or disagreement about this choice, the coding was discussed among the original coder and two or three of the authors until they agreed on a decision. Thus, all non‐trivial decisions were made by at least two, and up to four persons. Furthermore, all decisions were documented in detail to ensure consistent application across countries and time.

We aggregate this raw data for each cabinet, which is our basic unit of analysis, because most explanatory variables only change between cabinets. First, we code whether a reform overall suppresses minority rights. For reforms containing both suppression and expansion of minority rights, we code its overall effect based on a detailed reading of all changes and (if available) assessments from secondary literature; reforms that do not deal with minority rights at all are ignored. Second, we aggregate all reforms during a specific cabinet into a single score. For multiple reforms within one cabinet, we code the overall effect based on a detailed reading of all changes and (if available) secondary literature.Footnote 16

Our key explanatory variables on policy conflict are derived from the policy positions of political parties measured on the general left‐right scale of the Comparative Manifestos Project (CMP; Volkens et al. Reference Volkens2013), which was transformed into logged odds‐ratios as suggested by Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe2011).Footnote 17 While other conflict dimensions are clearly relevant in some countries for some time periods, the left‐right dimension provides the best comparative measure for the general level of policy conflict in Western European political systems over time (Müller & Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm2000; Coman Reference Coman2017).Footnote 18 To construct a measure of government−opposition conflict (H1a), we measure the absolute distance between each opposition party's ideal point and the ideal point of the cabinet (operationalised as the seat share‐weighted average of all cabinet parties’ positionsFootnote 19), weigh this distance by the share of opposition seats held by the respective opposition party, and then add up the weighted distances. As our hypothesis refers to changes in policy conflict, we use the change in this measure between the current and the previous cabinet to test H1a. The government's policy ambition (H2a) is measured as the absolute distance between the ideal points of the current cabinet and its predecessor on the left‐right scale. This measure is based on the assumption that the policy status quo at the beginning of a cabinet is roughly in line with the ideal point of its predecessor. Note that this variable is also a change measure because it captures the change in the policy positions between subsequent cabinets. Government parties are identified from the European Representative Democracy Data Archive (ERDDA; Andersson et al. Reference Andersson, Bergman and Ersson2014).

Our interaction hypotheses (H1b, H2b) require a dynamic measure for the majority‐friendliness of the institutional status quo. We use the degree of government agenda control as a proxy for this concept because agenda control allows governments to dominate parliamentary business and limit obstruction (Döring Reference Döring and Döring1995; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002; Cox & McCubbins Reference Cox, McCubbins, Schickler and Lee2011). Using our data on standing order change, we develop a dynamic version of Tsebelis’ (Reference Tsebelis2002: 103–105) time‐invariant government agenda control measure. More specifically, we ascribe the values provided by Tsebelis to the rules in force in each country on 1 January 1985 (the time when his raw data was collected). We then recalculate the score for each subsequent (previous) version by adding (subtracting) a change parameter that is given by the difference between the number of words changed in favour of the majority minus those changed in favour of the minority divided by the total number of words in the standing orders in force in 1985. This procedure is documented in detail in the Online Appendix. The resulting measure is highly correlated (r = –0.79) with Garritzmann's time‐invariant ‘opposition control index’ that includes multiple institutional powers of opposition parties in parliament (Garritzmann Reference Garritzmann2017).Footnote 20 We use the majority‐friendliness score at the beginning of each cabinet for testing our hypotheses. In addition to capturing the theoretically crucial conditioning effect of the institutional status quo, this dynamic measure also helps addressing concerns of endogeneity because it encompasses reform activities by previous cabinets that may affect the likelihood that the current majority pursues changes.

Regarding control variables, extra‐parliamentary veto points are operationalised by Ganghof's veto point index that captures the power of second chambers, constitutional courts, direct democracy and supermajority requirements to constrain the cabinet in policy making on the national level (Ganghof Reference Ganghof2005).Footnote 21 We use a binary variable indicating whether the government parties control the number of seats necessary to change the standing orders. Cabinet seat shares stem from ERDDA, the institutional majority requirement is identified from the standing orders. As proxies for transaction costs of reform, we use the effective number of parliamentary parties and a dummy variable identifying coalitions rather than single‐party cabinets (data from ERDDA). Electoral costs are approximated by the degree of electoral volatility that current governing parties experienced in the most recent election compared to the previous one (data from ERDDA).Footnote 22 Finally, we include cabinet duration as a control variable because longer‐lasting cabinets have more time to pass reforms. We measure cabinet duration in relative terms as percentage of the possible maximum duration to account for different inter‐election periods between countries (data from ERDDA).

The time‐series cross‐section (TSCS) structure of our data requires decisions on how to deal with temporal and spatial dependence. Regarding temporal dependence, we rely on the finding that our binary TSCS data are equivalent to grouped duration data (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Katz and Tucker1998). Thus, we can model temporal dependence via a smoothed hazard function of the time since the last reform. This hazard function picks up potential endogeneity due to the fact that observations at time t could be partly affected by observations at t‐1 (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Katz and Tucker1998).Footnote 23 For reasons discussed in the Online Appendix, we employ natural cubic splines with six knots; this choice does not substantially affect the empirical findings reported below (see the Online Appendix). Furthermore, large parts of the model (the dependent variable and many explanatory variables) are specified in first differences ensuring correct temporal ordering of the variables.

We account for spatial dependence by using clustered standard errors on the country level instead of country fixed effects. This approach allows estimating the effect of the institutional status quo (and its interaction with reform incentives), which is crucial for our theoretical argument and varies mostly between countries. A fixed effect (FE) model as the main alternative would ascribe this variation to theoretically uninformative country dummies. As Bell and Jones (Reference Bell and Jones2015: 134) put it, ‘in controlling out context, FE models effectively cut out much of what is going on – goings‐on that are usually of interest to the researcher, the reader and the policy maker’. The downside of our approach is that variation in the institutional status quo can be partly collinear with other country‐specific factors so that we might wrongly ascribe causality to the status quo. Yet an FE specification yields substantively equivalent results indicating that the use of clustered standard errors does not bias our results (see robustness tests below).

Empirical analysis

The frequency of minority rights suppression in 13 European parliaments

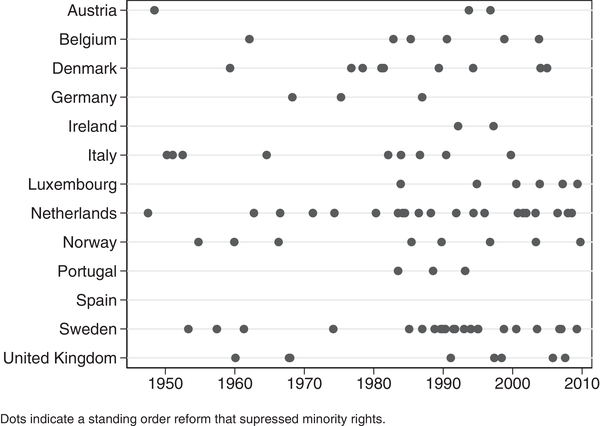

While parliamentary rules are often assumed to be stable, the available data show frequent changes in parliamentary standing orders (Sieberer et al. Reference Sieberer, Meißner, Keh and Müller2016). Even though many of these changes do not affect minority rights, Figure 1 shows that reforms that curb such rights occurred in all countries except Spain. However, their frequency varies considerably. While such changes are very rare in Ireland, Austria and Germany with only two or three instances over a period of more than 60 years, Sweden and the Netherlands witnesses 25 and 21 reforms, respectively.

Figure 1. Institutional reforms suppressing minority rights in 13 European parliaments, 1945−2010.

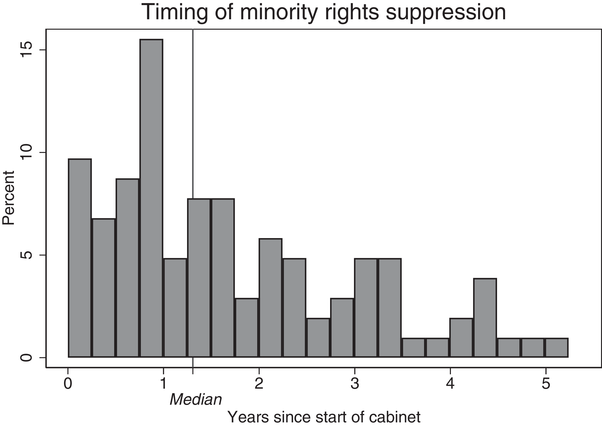

Figure 2 shows that these reforms cluster early in the life of a cabinet. The median time between the start of a cabinet and a reform suppressing minority rights is roughly 16 months (477 days) with about 40 per cent of all reforms occurring within one year after the cabinet took office. This indicates that majorities often suppress minority rights early in the term, which allows them to reap the benefits of such reforms directly.

Figure 2. The timing of reforms suppressing minority rights within legislative periods.

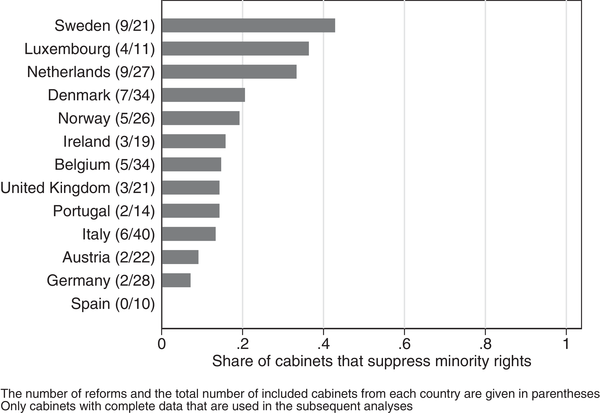

For further analysis, we aggregate these reforms to the cabinet level and code each cabinet as suppressing or not suppressing minority rights. After excluding cabinets with incomplete data on explanatory variables, 57 of 312 cabinets (18.3 per cent) suppressed parliamentary minority rights overall during their tenure.Footnote 24

Figure 3 shows the share of cabinets in the analysis sample that curbed minority rights for each country and (next to the country name) the number of reforms and number of cabinets. Again, we see that the share of cabinets that suppress minority rights is largest in Sweden followed by Luxembourg and the Netherlands and smallest in Spain (no reform), Germany and Austria.

Figure 3. Share of cabinets that suppressed minority rights by country.

Let us illustrate the substantive content of minority rights suppression with two examples. In Austria, a 1996 reform reduced the ability of the biggest opposition party (the right‐wing populist FPÖ) to use a variety of parliamentary instruments and rigorously cut debating time in ways that mostly hurt the largest opposition party (Sieberer & Müller Reference Sieberer and Müller2015). In France, a 1994 reform replaced detailed regulation on oral questions with a summary statement that the details and organisation of the question hour are fixed by the Bureau de l'Assemblée Nationale and the Conférence des Présidents. As both bodies mirror the political composition of the chamber, the reform enabled a determined majority to change the procedures of oral questions according to its wishes. Even without using this opportunity, the mere anticipation of this possibility should keep opposition parties from systematically using questions as a means of obstruction.

Explanatory analysis

Following the methodological discussion above, we use logistic regression models with standard errors clustered by country and a smooth baseline hazard function estimated via natural cubic splines to test our hypotheses. The variables measuring change in policy conflict between government and opposition, the change in policy conflict within the opposition and the majority‐friendliness of the institutional status quo are mean‐centred in order to allow for a meaningful interpretation. Descriptive statistics for all variables in the model are provided in Table SI‐2 in the Online Appendix.Footnote 25

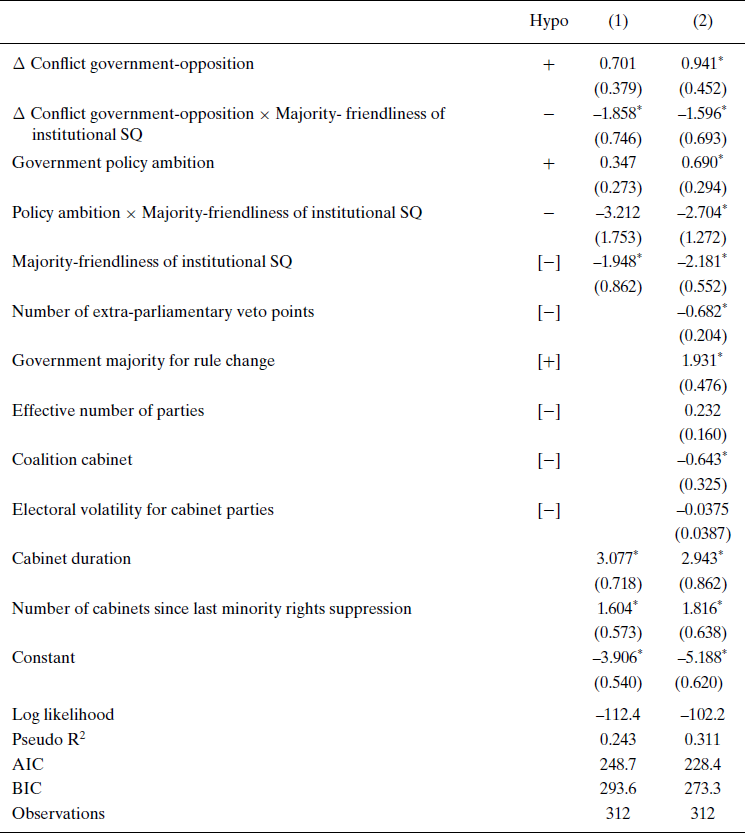

We test two different model specifications. Model 1 contains only our core explanatory variables – the two policy‐related measures, the institutional status quo and their interactions – as well as the variables that capture the baseline hazard of reform (cabinet duration, time since the last suppression of minority rights and the natural cubic splines). Model 2 also controls for the decisiveness of the parliamentary arena, the government's control of the necessary majority for rule changes and the three proxy measures for reform costs.

Table 1 displays the estimation results along with different measures of model fit and the theoretically expected signs of the coefficients. The overall model fit is good with a McFadden pseudo‐R2 of 0.24 for model 1 and 0.31 for model 2. AIC and BIC measures indicate that the full model is statistically superior. Thus, our subsequent discussion is based on model 2. This decision does not affect our substantive interpretations because both specifications produce qualitatively equivalent estimates.

Table 1 Logistic regression models of minority rights suppression

Notes: Logit coefficients with standard errors clustered by country in parentheses. *p < 0.05. Both models contain a smoothed hazard function based on six natural cubic splines. The second column contains the theoretically expected sign of the coefficient [in square brackets for those variables on which we did not formulate formal hypotheses].

The statistical analysis lends strong support to our theoretical argument. Increasing policy conflict between government and opposition (H1a) and a more ambitious government agenda (H2a) both have statistically significant effects in the theoretically expected direction. Note that due to the mean‐centring of the institutional status quo variable, these coefficients can be interpreted as the effect for a parliament with an average level of minority rights. As expected by H1b and H2b, these effects become significantly weaker when the institutional status quo is more majority‐friendly (or, equivalently, become stronger when the institutional status quo is more minority‐friendly).

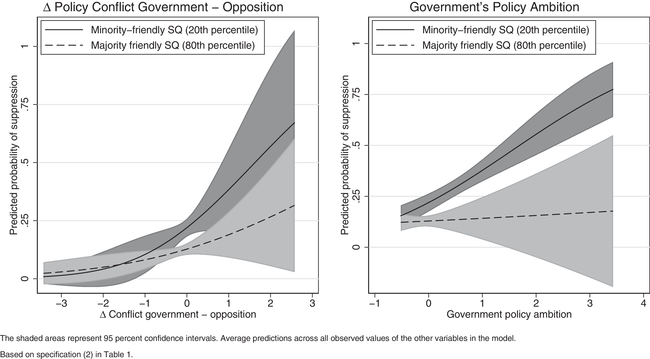

To assess substantive effect sizes, Figure 4 plots the average predicted probability of minority rights suppression according to model 2 for different values of change in policy conflict between government and opposition (left panel) and government policy ambition (right panel). Each panel contains separate predictions for a majority‐friendly and minority‐friendly institutional status quo (defined as 80th and 20th percentile of the variable, respectively), along with 95 per cent confidence intervals. We use the empirically observed values of the other variables in the model and report average predictions across all cases (Hanmer & Kalkan Reference Hanmer and Kalkan2013).

Figure 4. Predicted probabilities of minority suppression depending on policy‐related reform incentives and the institutional status quo.

Figure 4 demonstrates that both policy variables have substantively important effects that are clearly conditional on the institutional status quo. Minority rights are much more likely to be curbed for high increases of policy conflict between government and opposition (left panel), and this effect is stronger if the government faces a minority‐friendly institutional status quo (solid line). The effect of the government's policy ambition (right panel) depends even more strongly on the institutional status quo: Under strong minority rights (solid line), the likelihood that these rights are suppressed increases massively the more ambitious the government is, whereas policy ambition has hardly any effect if the majority already faces a favourable institutional status quo (dashed line).

Three of the control variables have statistically significant effects that are in line with expectations (even though we did not formulate formal hypotheses on these variables). Governments are more likely to suppress minority rights if they can change the standing orders without support by an opposition party; if they consist of a single party rather than a governing coalition; and if parliament is the decisive arena for policy making (i.e., if there are fewer extra‐parliamentary veto points). By contrast, parliamentary fragmentation (as a proxy for transaction costs) and electoral volatility of cabinet parties (as a proxy for electoral costs) have no systematic impact. Finally, the model picks up temporal dynamics as the likelihood of reforms increases with longer cabinet duration (i.e., longer exposure to risk in the parlance of duration data) and longer time having passed since the previous reform.Footnote 26

Robustness tests

We test the robustness of our findings with regard to several alternative model specifications and changes in the estimation sample. All robustness tests refer to model 2 in Table 1. We only summarise the results of these tests here; details on the rationale behind the additional specifications, the variables used and full estimation results are provided in the Online Appendix.

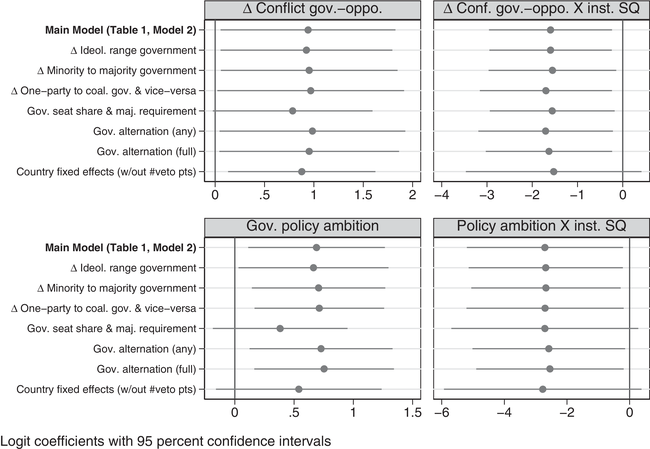

With regard to alternative specifications, we control for: (1) changes in policy conflict within the governing majority; (2) switches from minority to majority cabinets; and (3) changes from single‐party to coalition cabinets and vice‐versa. We also (4) replace the variable ‘own government majority’ with separate variables on government seat share and the majority requirement for rule changes;Footnote 27 (5) control for the types of government alternation experienced in the recent past (the share of the last three cabinets that consisted partly or fully of previous opposition parties); and (6) include country fixed effects.

Figure 5 shows that the coefficients of the two reform incentives variables and their interaction with the institutional status quo reported in Table 1 are very robust. The same is true for the other coefficients in the model (see Table SI‐2 in the Online Appendix). As expected, the confidence intervals increase in the fixed‐effects specification, but the point estimates are similar. Thus, using country fixed effects decreases the efficiency with which we can estimate the effects of substantive interest (because cross‐country variation is ascribed to country dummies rather than systematic variables) but does not reveal bias in the main models. All additional control variables added to the model are statistically insignificant.

Figure 5. Robustness tests with alternative model specifications.

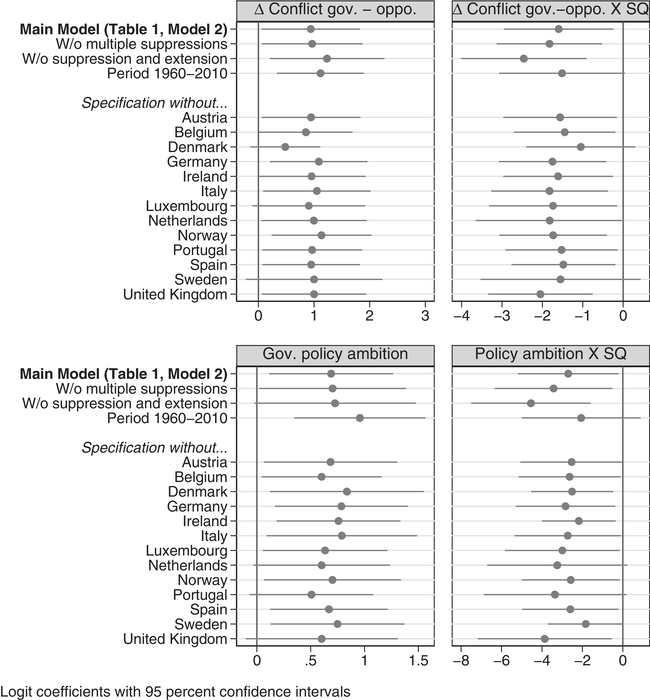

Regarding alternative samples, we estimate specifications that exclude: cabinets with multiple reforms suppressing minority rights during its tenure; cabinets that witnessed reforms in both directions (suppression and extension of minority rights); and cabinets that came into office before 1960 to test whether our findings are driven by potentially exceptional conditions in the early postwar period. Furthermore, we assess the degree to which individual countries drive our findings by excluding one country at a time from the analysis.

Figure 6 again demonstrates the robustness of our core findings (results for the other variables are provided in Tables SI‐3a and SI‐3b in the Online Appendix). The specifications that drop cabinets with unusual patterns of reforms or cabinets from the early postwar period yield very similar results. Excluding individual countries leads to minor changes in the estimated coefficients, but does not indicate that the overall results are driven by individual countries. Overall, the tests show that our findings do not depend on a specific model specification or analysis sample.

Figure 6. Robustness tests with alternative analysis samples.

Conclusion and discussion

Rational choice institutionalist research in the institutions‐as‐equilibrium tradition argues that political actors reform institutions if they expect new rules to yield higher substantive net payoffs than the institutional status quo (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1990; Diermeier & Krehbiel Reference Diermeier and Krehbiel2003). While this argument was originally developed in legislative studies (Riker Reference Riker1980; Shepsle Reference Shepsle, Weingast and Wittman2006) and has been demonstrated empirically in congressional research (Binder , Reference Binder2006; Schickler Reference Schickler2000), it has not been tested systematically in parliaments outside the United States. Even more, many case studies in Europe reject this logic and instead emphasise consensual patterns of reform based on functional needs.

This article demonstrates that actors in European parliaments, just as their American counterparts, reform institutional rules to serve their substantive goals. In particular, government parties curb minority rights if they fear that opposition parties will use existing minority rights to obstruct the government's policy agenda. Our statistical analysis of more than 300 cabinets in 13 Western European parliaments over a period of 65 years shows that minority rights are significantly and substantially more likely to be suppressed if policy conflict between government and opposition increases and if the government seeks larger deviations from the policy status quo. Both effects are conditional on the institutional status quo – that is, they are stronger the more rights minority parties currently enjoy. Our analyses establish the robustness of these findings towards controlling for reform costs, alternative model specifications and other analysis samples.

Future work could extend the present analysis in at least three directions. First, our large‐n design had to treat all reforms the same even though the substantive importance of rule changes clearly differs. Studies using qualitative methods could investigate these differences in detail and test additional implications of our theoretical claim for the size of reforms. For example, one could hypothesise that extreme changes in policy conflict or government ambition combined with a minority‐friendly status quo lead to particularly radical reforms. Second, reform costs should be studied in more detail because they could explain why changes in minority rights occur less often than a strict equilibrium view might suggest. In this article, we relied on proxy measures that only served as control variables. Studying costs in more detail and developing direct measures for different types of reform costs would be a challenging but worthwhile endeavour. Third, this article did not seek to explain under what conditions minority rights are expanded. Based on the theoretical logic advanced here, such reforms should occur if parts of the current majority fear to be in minority in the future and thus have incentives to accept an immediate constraint on power in expectation of higher payoffs after a change in government. Qualitative case studies provide some evidence for such an insurance strategy in contexts of high uncertainty regarding future government composition (Thaysen Reference Thaysen1972; Sieberer & Müller Reference Sieberer and Müller2015). Testing this claim statistically would be a logical next step, notwithstanding the difficulty of measuring actors’ expectations about their future government status.

In closing, let us point out the broader relevance of our findings for the study of legislative politics as well as institutional design more generally. In legislative studies, our results refute case study claims that parliamentary reforms in Europe follow a consensual logic and demonstrate instead that majorities in European parliaments do redesign parliamentary rules to serve their substantive policy interests. These findings are consistent with theoretical work in the institutions‐as‐equilibrium tradition (Riker Reference Riker1980; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1990; Calvert Reference Calvert, Knight and Sened1995; Diermeier & Krehbiel Reference Diermeier and Krehbiel2003; Shepsle Reference Shepsle, Weingast and Wittman2006) as well as empirical work on the United States Congress (Binder ; Dion Reference Dion1997; Schickler Reference Schickler2000). As such, this study demonstrates once more how arguments from the Congressional literature can be adapted and applied successfully in comparative legislative research (Gamm & Huber Reference Gamm, Huber, Katznelson and Milner2002).

Regarding the study of institutional change in general, our findings stress the importance of the institutional status quo for actors’ reform incentives. Institutional change always involves costs, and these costs are particularly relevant for distributive reforms that produce not only transaction costs, but also political costs due to reactions by other political actors and the public. Actors will only pursue high‐cost reforms if current rules are clearly disadvantageous for them and a reform would yield a major improvement. Accordingly, the same disturbance in the system (e.g., the same increase in conflict between different actors) should lead to reform in some cases and to institutional stability in others. This insight is particularly important for comparative studies of institutional reform, in which the institutional status quo can differ vastly across cases. Theoretically, the importance of the status quo provides a direct link to historical institutionalist arguments on path dependence in institutional development. Scholars in this tradition argue that institutional reforms are conditioned by previous reforms producing different institutional trajectories that in turn affect the likelihood and direction of future institutional change even under otherwise equal conditions (e.g., Mahoney Reference Mahoney2000; Pierson Reference Pierson2004; Mahoney & Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010). Starting from a rational‐choice institutionalist argument, we arrive at a very similar conclusion, which reinforces the compatibility of rationalist and historical institutionalist arguments in explaining institutional change over time (Hall Reference Hall, Mahoney and Thelen2010).

With regard to minority rights, the impact of the institutional status quo should be studied more thoroughly in future work that analyses both their suppression and their extension. This article demonstrated a ceiling effect in the sense that majorities do not curb minority rights further once the institutional status quo provides them with a strong position. Theoretically, it is plausible to expect that a majority‐friendly status quo provides minority actors with some leverage to campaign for extending minority rights with reference to fairness arguments (Sieberer & Müller Reference Sieberer and Müller2015). In consequence, actors’ rational self‐interest combined with public pressure and (anticipated) electoral sanctions could create a self‐enforcing mechanism of ceiling and floor effects that keeps the institutional distribution of power between government and opposition parties in parliament within a limited and, normatively speaking, healthy balance.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG, grant number SI 1470/2‐1) and the Zukunftskolleg at the University of Konstanz. The authors gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contribution of more than 30 student assistants working on the project over the years and the extraordinary input by Michael Becher and Maiko I. Heller during the early stages of the project. Earlier versions of this article were presented at APSA in 2014, ECPR Joint Sessions in 2012, ECPR Standing Group on Parliaments in 2016, MPSA in 2013, 2014 and 2017, and talks and workshops at the Universities of Konstanz, Mannheim and Heidelberg. We thank the various discussants and participants for many insightful comments. We gratefully acknowledge valuable suggestions by three anonymous reviewers for the EJPR.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table SI‐1: Descriptive statistics for the variables in the statistical model

Figure SI‐1: Model fit measures for different specifications for temporal dependence (log likelihood)

Figure SI‐2: Robustness of the main model vis‐à‐vis alternative ways to account for temporal dependence

Table SI‐2: Detailed results of the robustness tests displayed in Figure 5

Table SI‐3a: Detailed results of robustness tests displayed in Figure 6 (first four models)

Table SI‐3b: Detailed results of robustness tests displayed in Figure 6 (models dropping individual countries)

Table SI‐4: Correlations between change in policy conflict and government policy ambition

Figure SI‐3: Robustness of the main model vis‐à‐vis excluding Luxembourg and Spain