Introduction

The concept of political markets has been a staple of political science since the 1950s, even as it remained somewhat disjointed from the mainstream of party system and electoral reform research. At least two different streams made use of the notion of political markets as core concepts of their theoretical framework: the Downsian and the Schumpeterian traditions. Followers of the former tradition define the political arena as a market determining which party will take control of government (for an overview, see, e.g., Wohlgemuth Reference Wohlgemuth, Marciano and Josselin2005: 24; Strøm Reference Strøm1992; Körösényi Reference Körösényi2012). Followers of the latter tradition, by contrast, describe the top‐level competition in question as a bidding process for the ‘natural monopoly’ of government (Tullock Reference Tullock1965; Wohlgemuth Reference Wohlgemuth2000: 274; Wohlgemuth Reference Wohlgemuth, Marciano and Josselin2005: 24–25).

Recent studies of electoral reforms make use – if only in a limited manner – of this analogy of the party system and economic markets. Núñez and Jacobs (Reference Núñez and Jacobs2016) mapped the circumstances that influence the likelihood of electoral reforms and made a reference to entry barriers. Birch et al. (Reference Birch, Millard, Popescu and Williams2002: 187) discussed the strategic behaviour of newcomers in the party system. Yet these discussions are rarely built on an explicit theory of political markets and are not directly aimed at investigating the relationship between the electoral system understood as rules for market access and party system change defined as a change in market structure.

We offer a twofold contribution to the extant literature, both theoretical and empirical. While existing research on parties and elections makes use of concepts related to market structure and strategy, such as ‘competition’, ‘market’, ‘rules’ or – in a few cases – ‘entry barriers’, it does not rely on a coherent theory of political markets. Our theoretical argument addresses this gap in the literature by proposing the framework of an interrelated system of not one, but three markets. We also put forth a further theoretical implication of this complex market structure: majority party strategy may be aimed at exploiting the interdependent nature of political markets for gaining political advantages.Footnote 1

As for our empirical contributions, it is notable that the few authors who contemplated an explicit theory of political markets did not conduct empirical research to explore its relevance. We provide a new operationalisation of the concepts related to market structure that lends itself to the study of political phenomena. We also develop an empirically testable hypothesis that is directly derived from theory. Finally, we present empirical results for four countries for which the study of political entry barriers remains uncharted territory.

Our theory of political entry barriers relies on a notion of interconnected political markets with their respective entry barriers. The resulting hypothesis states that the modification of the entry barriers in the market for parties leads to changes in the concentration of the aggregated popular vote for national or regional party lists, whichever is applicable. An observable implication of this relationship would occur if an electoral reform that raises entry barriers led to subsequent increases in the Herfindahl index (a measure of market concentration), and vice versa.

We provide an empirical test of this proposition with a comparative analysis of a new database covering Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia. The research design of our study follows the standards of small‐n qualitative comparative analyses. For the dependent variable, we use the standard approach of the Herfindahl index for measuring market concentration. On the independent variable side, we focus on the barriers related to the creation and operation of political organisations. We developed an index of entry barriers that consists of five main indicators in order to gauge their effects on party system concentration. Based on this operationalisation of entry barriers, we gathered data on the monetary or other costs related to the creation and operation of political legal entities. In our analysis, this qualitative data on institutional changes and reforms is juxtaposed against quantitative data on market share in the market for parties.

Our analysis offers support for our hypothesis: in most cases the changes in the entry barriers led to a corresponding adjustment of concentration in the market for parties. Our results show that out of 12 substantive entry barrier changes in the four countries, ten reforms led to a significant (more than 5 per cent) change in party vote concentration. Among the ten cases of substantial (over 5 per cent) concentration change, we confirmed the hypothesis for eight observations, which is an 80 per cent success rate.

Literature review

In this section we consider the conceptual sources of a unified theory of political markets. We start out by recognising that despite sporadic references to market structure and entry barriers, a coherent theory of political markets is still elusive. Next, we move on to discuss two potential conceptual sources for such a framework: public choice theory, Downsian and Schumpeterian alike, and the theory of industrial organisation – both of which make extensive use of the notion of entry barriers.

The elusive theory of political markets

As previously mentioned, at least two different streams have made use of the notion of ‘political markets’ as a core concept in their theoretical framework: the Downsian and the Schumpeterian traditions. In the Downsian tradition, actors strive to match their ‘product’ to exogenous electoral preferences in order to obtain ex ante authorisation for the execution of a specific set of public policies. Followers of the Schumpeterian tradition, by contrast, emphasise ex post accountability as, according to their view, voters lack well‐defined preferences that could serve as the basis for ex ante accountability. In this context, the policy agenda, as well as public policies, are set by incumbent parties (Wohlgemuth Reference Wohlgemuth, Marciano and Josselin2005: 24–25).

Theories of the political market may also be distinguished based on the level of political competition on which they focus. The competition for government authority – generally involving only a handful of oligopolistic actors, see Downs (Reference Downs1957: 137) – is positioned at the highest level. Despite the dominance of the Downsian framework, a similarly compelling analogy has been put forth by Tullock and his peers. This describes the top‐level competition in question as a bidding process for the ‘natural monopoly’ of government (Tullock Reference Tullock1965; Wohlgemuth Reference Wohlgemuth2000: 274). Applied to parliamentary systems, this logic derives legislative and, therefore, executive power from the Weberian monopoly on violence. Taking a cue from microeconomics, elections are defined here as auctions dispersed over time that allow for the markets to ‘clear’ (Wohlgemuth Reference Wohlgemuth2000: 277).

The concept of political markets has not been at the forefront of the scholarly debates surrounding the development of party and electoral systems. It is revealing that a recent monograph on electoral reform (i.e., Renwick Reference Renwick2010) does not include a reference to the notion of political markets. The same holds true for studies explicitly focusing on the party systems of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), even as they consider elements of electoral reform that are very much compatible with the political markets approach.

This is not to say that the relationship of parties and their regulators in post‐communist party systems has not attracted any recent scholarly attention. Kopecký (Reference Kopecký2006) highlighted the symbiosis between political parties and the state in CEE, pointing out a strong state involvement in internal party affairs and party financing. Grzymała‐Busse (Reference Grzymała‐Busse2007) investigated the way parties both reconstructed and exploited the state in a post‐communist setting. A number of works focused on party funding, emphasising the strong role of the state in the region (e.g., Van Biezen & Kopecký Reference Biezen and Kopecký2001, Reference Biezen and Kopecký2007; Smilov & Toplak Reference Smilov and Toplak2007; Roper & Ikstens Reference Roper and Ikstens2008). The conclusions of these studies are not always congruent: while Van Biezen and Kopecký (Reference Biezen and Kopecký2001: 401) argue that the ‘predominance of state money may act to freeze the status quo of the party system’, Roper (Reference Roper, Roper and Ikstens2008: 2) claims that ‘public finance does not have a determinative effect on party competition’. Finally, Casal Bértoa and Van Biezen (Reference Casal Bértoa and Biezen2014) note that party regulation has had an uneven impact on party system development in the post‐communist part of Europe.

Our contribution is in direct conversation with this line of research in that it investigates the impact of the changes of the regulatory framework – understood here as electoral reforms and reforms of public funding – on party competition. The general theme of the ‘modifying effects’ (Clark & Golder Reference Clark and Golder2006) of the electoral system on the ‘number of parties’ (see, e.g., Moser Reference Moser1999; Lago & Martinez Reference Lago and Martínez2007; Reuchamps et al. Reference Reuchamps, Onclin, Caluwaerts and Baudewyns2014) also crops up from time to time in the literature. Yet only few studies go so far as to directly reference strategic entry and the costs of entry (Tavits Reference Tavits2006, Reference Tavits2008) or to mention the role of barriers to entry in this context (Doron & Maor Reference Doron and Maor1991; Van Biezen & Rashkova Reference Biezen and Rashkova2014).

More recently, Núñez and Jacobs (Reference Núñez and Jacobs2016) mapped the circumstances which influence the likelihood of electoral reforms. The authors made an attempt to gauge the effect of various barriers that may hinder the change of electoral institutions in Western Europe. However, the presumed link between electoral reforms and the party market structure was beyond the scope of their research. In a similar study analysing the electoral reforms of eight post‐communist states in the first decade after the transition, Birch et al. (Reference Birch, Millard, Popescu and Williams2002: 187) pointed out that ‘the learning process both enabled them to engage in increasingly strategic behavior and at the same time it widened the range of design elements that were seriously considered’. Furthermore, ‘over time there was an increase in barriers to entry for newcomers and advantages to existing political actors which worked to entrench their positions’ (Birch et al. Reference Birch, Millard, Popescu and Williams2002: 180).

The results of Chytilek and Šedo's (Reference Chytilek and Šedo2007) study are in line with the findings of Birch et al. (Reference Birch, Millard, Popescu and Williams2002): using a sample of 40 electoral events in 15 post‐communist countries, they concluded that the electoral reforms carried out in the post‐transition period favoured larger and more established parties. In contrast, Bielasiak and Hulsey (Reference Bielasiak and Hulsey2013), investigating a more extensive set of post‐communist party systems on a broader time scale, claimed that with respect to major reforms in election formula and district magnitude, electoral rules have become more permissive.

While these articles provide some insights with regard to the potential of the empirical application of a coherent theory of political markets, they refrain from directly applying the market analogy, as a paradigm, and the corresponding instruments of market structure analysis, such as market concentration measures. They are rarely built on an explicit theory of political markets and are not directly aimed at the relationship between the electoral system, understood here as the rules for market access, and party system change, understood here as market structure change. Therefore, in this article we examine not only individual concepts, such as the costs of entry, but political market structure in general, which is a novel approach in the literature.

Downsian perspectives

Public choice literature offers some useful clues for formulating a coherent theory of political markets (in plural). Authors aligned with this paradigm mostly examined the highest level of political competition, one that is populated by parties and candidates vying for executive power. The studies in question often build on the models of Hotelling, Downs and Duncan Black (Enelow & Hinich Reference Enelow and Hinich1984; Merrill & Grofman Reference Merrill and Grofman1999; Adams et al. Reference Adams, Merill and Grofman2005). In more recent party systems research, the topic was mainly discussed as a ‘competition for government’, including features such as being ‘open to all parties or closed’ (Mair Reference Mair, Katz and Crotty2006: 68; Wolinetz Reference Wolinetz, Katz and Crotty2006: 52–53, though the latter also claims that using the notion of ‘open or closed’ in systems research has a potential that ‘has not yet been explored’).

The middle level of political competition for seats and groups in the legislature is also extensively theorised in the literature. It is either treated as an arena for office‐seeking and policy‐seeking parties as opposed to vote‐seeking parties (Strøm Reference Strøm1990; Wolinetz Reference Wolinetz, Gunther, Montero and Linz2002: 150), or ‘New Politics’, niche and single‐issue parties (for the former, see Poguntke Reference Poguntke, Katz and Crotty2006: 401; Meguid Reference Meguid2005; for the latter, see Meyer & Miller Reference Meyer and Miller2015; Taggart Reference Taggart1998; Mudde Reference Mudde1999). In contrast, the lowest level of political competition, one that is not aimed at government power or parliamentary seats, is theorised as the domain of grassroots movements, civil society and interest groups, and the external relations of the party system with these entities (Poguntke Reference Poguntke, Katz and Crotty2006) − very much apart from any notion of a political market.

Finally, the interaction between the various levels of political competition is rarely addressed directly in a political market framework – some studies on redistricting/gerrymandering (e.g., Handley & Grofman Reference Handley and Grofman2008) and, especially for American scholars, issues of voter registration (Highton Reference Highton2004: 510) notwithstanding.

One major take‐away from this brief discussion of the literature is that a full‐fledged model of the structure of political markets is still elusive. On the other hand, the so‐called ‘unified theories’ (Merrill & Grofman Reference Merrill and Grofman1999; Adams et al. Reference Adams, Merill and Grofman2005) compress all aspects of political markets into a spatial ‘model of party competition’ based on vote‐maximising parties. While they allow for ‘a full range of possible political market conditions’ (Bergman & DeSouza Reference Bergman and DeSouza2012: 6), they in fact exclude the possibility of numerous and mutually interacting political markets.

Schumpeterian perspectives

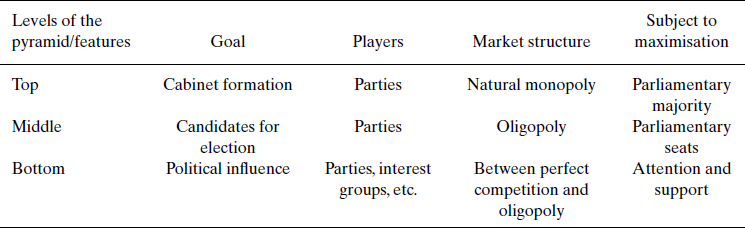

It is important to note that some authors associated with public choice in fact move beyond interpreting politics through the single‐market analogy. Following Chadwick (Reference Chadwick1859), they talk explicitly about the competition in the market (or in/within the field) and for the market (Demsetz Reference Demsetz1968: 57; Galeotti Reference Galeotti, Breton, Galeotti, Salmon and Wintrobe1991). These interrelated concepts effectively correspond to the notions of the market for parties and of the market for government. If we break the concept of ‘competition for the market’ down further, we end up with a three‐level political pyramid as presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Features of political markets

At the base of the pyramid, we find the market for political participation. This is a competition for ‘political attention’ and support. Unlike the periodicity of the market for government, contest in this market is continuous. The market for parties, at the middle level of the pyramid, creates a connection between the market for government and the market for participation. Successful players may enter at the lowest level, as was the case with green grassroots organisations evolving into full‐fledged political parties in various European countries, and over time they may even compete in the market for government. Players in the market for parties contend for parliamentary seats and the concomitant resources. Their success is evaluated based on criteria that are independent of a position in government, as is the case with most single‐issue parties.

The second major theme that deserves a more detailed discussion relates to the structure of each of these markets. The introduction of the idea of democracy as a natural monopoly by Tullock (Reference Tullock1965: 458) opened up the question of the market structure of political markets. Wohlgemuth (Reference Wohlgemuth2000: 281) writes about entry barriers to the ‘participation in the auction’, and an almost automatic logical conclusion from this is the recognition that the market for parties is not another market's ‘anteroom’, but rather a standalone market with its own structure. Schleicher (Reference Schleicher2006) refers to this insight explicitly when he talks about the ‘pre‐election market’ as a ‘downstream market’ compared to the election market.

If we accept the conceptualisation of the three interrelated markets as a model of representative democracy, we also have to acknowledge the possibility of a dense web of strategic interactions of the stakeholders in these markets. This leads to our third theoretical pillar: entry deterrence as a political strategy. Entry deterrence has, in fact, been occasionally modeled in sequential games as a tool for limiting competition (Mulligan & Tsui Reference Mulligan and Tsui2008: 3). Issacharoff and Pildes (Reference Issacharoff and Pildes1998) analysed the duopoly collision of Democrats and Republicans in the United States in passing laws that limit the entry of third‐party candidates into political markets. But this is not the whole picture. Entry barriers play different roles in different markets: low entry barriers may be beneficial for the incumbent in one market and detrimental to the incumbent in the other. In order to fully understand strategic behaviour in political markets, we have to depict each of these markets in line with their own logic and characteristic market structure.

The theory of industrial organisation and entry barriers

Rather than submerging all aspects of political markets into an overly complex hybrid model, an alternative strategy would unpack them into different political markets. Political scientists could borrow concepts from industrial organisation theory (Tirole Reference Tirole1988; Cabral Reference Cabral2000) for such an exercise. A good example of this approach is provided by Crain (Reference Crain1977: 829), who defines the ‘political market’ as a marketplace for buyers and sellers of ‘public‐policy outcomes’. This theoretical framework emphatically stresses the relevance of the ‘institutional structure’ of this market, as well as the potential restrictions on market entry. These barriers to entry are often treated as a means of rent‐seeking (Mueller Reference Mueller2003: 335–337), such as in the case of interest group lobbying (Anderson Reference Anderson1980). Soft barriers such as brand names and advertising are also considered in this context (Netter Reference Netter1983; Lott Reference Lott1986). Nevertheless, a complete categorisation of entry barriers in political markets remains an unfinished exercise. Fortunately, microeconomics offers useful analogies with its widely discussed typologies of economic entry barriers (Bain Reference Bain1954; Demsetz Reference Demsetz1982; Shepherd & Shepherd Reference Shepherd and Shepherd2003: 74–75; for a comprehensive review, see Table 1 in Lutz et al. Reference Lutz, Kemp and Dijkstra2010).

The first important distinction is between exogenous and endogenous entry barriers. The former ‘are embedded in the underlying conditions of the market’, while the latter refer to actions ‘within the dominant firm's own discretion’ (Shepherd & Shepherd Reference Shepherd and Shepherd2003: 191–195). This distinction, however, obscures the difference between strategic actions commonly referred to as ‘endogenous’, such as predatory pricing, and those aimed at changing the ‘underlying conditions of the market’ (Shepherd & Shepherd Reference Shepherd and Shepherd2003: 191).

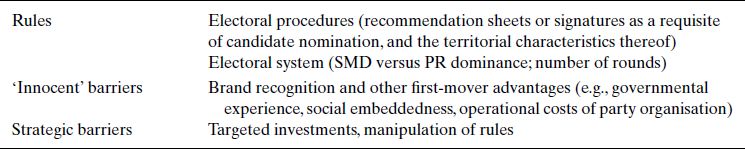

While these distinctions are crucial for any analysis of political entry barriers, a more nuanced classification is needed in order to account for their unique nature. With his three‐tier classification, Wohlgemuth (Reference Wohlgemuth1999: 182) offers a good example for such a framework applied to political markets (see Table 2).

Table 2. Entry barriers on the market for parties

Source: Adapted from Wohlgemuth (Reference Wohlgemuth1999: 182; Reference Wohlgemuth2000: 280–281).

Constitutional regulations are a principal reason for the absence of perfect competition in political markets. Limitations to ballot access are just one form of aligning electoral choices with the interests of rationally ignorant voters. An important restriction of this kind is related to party lists: actors with geographically uneven support may be disadvantaged. Similarly, the precise rules for recommendation slips (e.g., recommendations limited to a single candidate as opposed to multiple candidates) may cause entry barriers to vary significantly.

Innocent barriers are the direct products of the ‘underlying market conditions’ for parties and are thus unrelated to the strategic actions of the actors involved. Investments in propping up market share, such as advertising purchases, may be independent of legal regulations but still pose challenges to new actors. Incumbency also brings advantages, including name recognition or databases from previous campaigns.

Finally, strategic barriers arise from the actions of actors attempting to shape the political landscape. These strategic barriers include schemes of deterrence (e.g. negative campaigns), or the political analogies of predatory pricing. The latter refers to incumbents incurring a loss in exchange for driving competitors out of the market. Tinkering with electoral rules often produces such outcomes. It is also important to note that these are not mutually exclusive categories, as various types of behaviour may spill over into other areas: new strategic choices emerging in the wake of electoral reforms are just one example of this effect.

Theory and hypothesis

The studies discussed above provide useful insights into the problems of theorising political markets. Nonetheless, this literature largely ignores three salient themes: the multiplicity of political markets; the possibility of different market structures in each of these markets; and the role of strategic agency in modifying their structures. The answers to these problems will serve as the main theoretical pillars for our hypothesis with regard to the role of entry barriers in shaping the market structure.

With these three additions to a basic understanding of political markets, we are now in a position to formulate a preliminary theory of the complex, vertically integrated structure of political markets in representative democracies. In the market for participation, actors maximise citizens’ attention and support (see Table 1). As attention is a scarce resource (Falkinger Reference Falkinger2008), political organisations and ‘celebrities’ compete with non‐political actors in a multilayered market consisting of media and participatory arenas. ‘Garnering attention’ is defined as the ability to access the political agenda, whereas ‘support’ refers to the general favourability ratings in the voting age population. In stark contrast to the market for government, the notion of market share is paramount.

Due to legal obstacles, civic organisations and interest groups usually cannot compete in the market for parties. In the latter market, parties compete with one another in a closed club for resources that are exclusively associated with party politics, as opposed to, say, resources linked to governing positions. This closed club is established by hard (mostly legal) entry barriers, which include campaign subsidies, allowances for party foundations and office space granted by the state, but also soft ones such as media access (see again Table 1). Market share is crucial as well, and it is measured by the respective party's share of parliamentary seats or other public offices (e.g. municipalities).

On the two lower levels of the pyramid, market structure may oscillate between near perfect competition and a duopoly. Nevertheless, perfect competition is never achieved, not even at the lowest level: directly or indirectly, the activities of parties spill over from the second level through their allies, such as American‐style political action committees. Furthermore, huge disparities persist due to unevenly distributed resources. These overlaps are an inevitable feature of the pyramid of political markets since party interests, in one legal form or another, are present at all three levels, integrating specific markets into the general political sphere. This allows for, and also necessitates, coherent strategies by the actors who are active on all three levels.Footnote 2

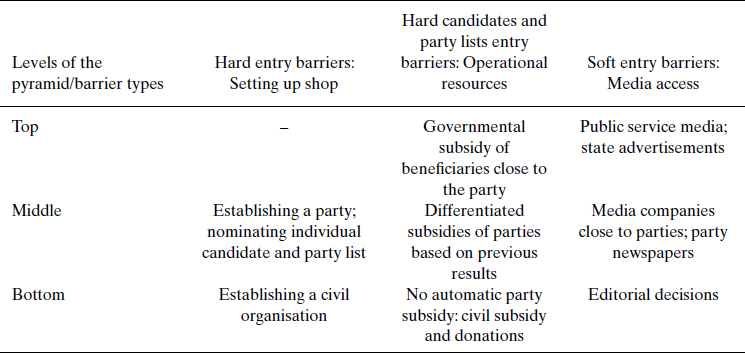

It is important to emphasise that not all markets are created equal: incumbents of the monopoly for government determine the operational rules of the other two levels. One of the most important institutional forms of these rules is entry barriers (see Table 3). As a general rule, entry barriers are lower as we approach the base of the pyramid, but their exact ‘height’ and respective positions at each level fundamentally determine the nature of the given polity.

Table 3. Examples of entry barriers by political markets

We rely on this understanding of interconnected political markets with their respective entry barriers in developing a proposition concerning electoral reforms and other changes in the rules of democracy that have a bearing on the structure of the market for parties. The resulting hypothesis states that the modification of entry barriers in the market for parties leads to changes in the concentration of the aggregated popular vote for national or regional party lists, whichever is applicable. An observable implication of this relationship would occur if an electoral reform that raises entry barriers led to subsequent increases in the Herfindahl index, and vice versa.

Data and methods

The remainder of this article offers an empirical test of the theory of political markets and the related hypothesis regarding the effect of entry barriers on market structure. Our research design is based on a comparative analysis of a new database covering Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia from 1990 to 2016. We analyse the political development of these countries in order to test whether changes in entry barriers led to corresponding changes in the structure of the market for parties.

Our case selection was motivated by two considerations. First, the design of the electoral systems in these countries is sufficiently similar to allow for isolation of the effects of the explanatory variable (institutional change) on the dependent variable (market structure) from background factors such as geographical impacts or historical development. In addition to their geographical proximity and cultural similarities, all four countries made the transition from communism to post‐communism during the period in question.

The second motivation relates to transition and the trial and error process of creating a stable and functioning institutional structure for representative democracy. When it comes to shaping entry barriers in political markets, these countries presumably show greater variation on the independent variable side than countries with better‐developed formal rules and informal traditions (see Núñez and Jacobs (Reference Núñez and Jacobs2016), who claim that electoral reforms occur only rarely in established democracies). This provides a better testing ground for a hypothesis that relies on institutional change as an explanatory factor.

The research design of our study follows the standards of small‐n qualitative comparative analyses. An ideal methodological approach would take advantage of an entry barrier index encompassing all accessible information regarding substantive barriers. Unfortunately, such a holistic approach was unfeasible for this project due to a lack of data and the inherent problems of quantifying qualitative information. Hence, in the context of barriers to entry, two elements were selected for further inquiry: the respective barriers concerning the creation and the operation of political organisations. In our view, taken together, they provide a fair, if incomplete, representation of some major hurdles to entry at any given time.

We developed an index of entry barriers made up of five main indicators in order to gauge its effect on party system concentration. First, we considered the requirements for establishing a party list and standing as a candidate in elections. Such requirements include electoral deposits and the collection of a certain number of signatures. The second indicator is the electoral threshold, the proportion of votes cast for a party list that are required for acquiring seats in parliament by party lists. Third, we considered changes in the electoral system that have an effect on district magnitude. Fourth, we examined modifications to the electoral formula as different formulas benefit different types of parties. Finally, the fifth indicator concerns changes in the rules on subsidies provided to parties by the state.

In our analysis, we marked increased entry barriers with ‘+’ or ‘++’ (depending on ‘significance’), and lowered barriers with ‘–ʼ or ‘– –ʼ (minor changes were signaled with a ‘0’). The two marks of ‘+’ and ‘–ʼ indicate a change with limited, albeit still discernible impact, whereas the marks ‘++’ and its opposite number ‘– –ʼ denote a more significant impact. To obtain the aggregate results, we used the average of the changes in each of these dimensions for the given country‐year observation. The ‘significance’ of the changes and our final evaluation has also been double‐checked by experts from each country in the sample.

Changes in the electoral system were considered to be associated with a higher entry barrier if they favoured the established and/or bigger parties at the expense of newcomers and/or smaller parties. Tightened rules for candidate or party registration, a raised electoral threshold and decreased district magnitudes were seen as indicative of such changes, along with modifications of the electoral formula that led to a reduced proportionality. In the case of public party funding, entry barriers were considered to be raised if the changes favoured the parties subsidised by the state, at the expense of parties without state subsidies, either by a tightening of the eligibility criteria or by an increase in the amount of funding. Changes in the opposite direction for any of these factors were indicative of lower entry barriers according to this framework.

Based on this operationalisation of entry barriers, we gathered data on the monetary or other costs related to the creation and operation of legal entities. This qualitative data on institutional changes and reforms was juxtaposed against quantitative data on market share within the market for parties where market share was defined as votes for ‘party lists’, either national or regional.

In three out of the four countries analysed, party‐list proportional representation is used to elect the legislature (except the upper houses, which are beyond the scope of this article). In Czechia, regional lists were used during the entire period. In Slovakia, regional lists were replaced by a single nationwide list in 1998. Poland is a more complicated case, since it used regional lists and a national list until 2001, when the latter was abolished. However, voters only choose from regional lists. In the case of Hungary, which has a mixed electoral system, for the sake of comparability, only the votes cast for regional lists were taken into account (for further details, see the Online Appendix).

For calculating market concentration based on party list votes, we utilised a metric that is widely used in measuring market structure: the Herfindahl index. This is calculated as follows:

where si is the vote share of party i in the market for parties (share of the votes for the given party list), and n is the number of parties with a party list for the given election. The indicator can take a value between 0 and 10,000, where the former indicates perfect competition and the latter complete monopoly. This index, or its variants (mainly: the effective number of parties), have been used in a number of empirical studies on party systems (e.g., Rae Reference Rae1971; Laakso & Taagepera Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979, or more recently, Golosov Reference Golosov2010; Grofman & Selb Reference Grofman and Selb2011). We can adapt the Herfindahl index to party systems by interpreting lower values as indicators of less concentrated, more fragmented markets (i.e., several small or medium‐sized parties compete for votes). High values, by contrast, indicate a more concentrated, less fragmented structure, where typically two large parties dominate the party system.Footnote 3

Based on these indicators, we provide a qualitative analysis of the impact of entry barrier changes on party market structure after the parliamentary election when the change first took effect. When the barriers are raised, we expect the concentration of votes in the given market to increase and vice versa. While a regression analysis based on dummy variables for the direction of institutional change in any given electoral period would be feasible, we opted for a qualitative analysis due to the small number of observations, although we provide the results for such a quantitative analysis for reasons of transparency.

Analysis

In this section we first provide a description of each of the four country cases. Only major developments and summary results are discussed, but we present more information on institutional changes for each country in the Online Appendix. Next, we conduct a comparative analysis of the cases and evaluate the hypothesis.

A comparative analysis of four CEE cases

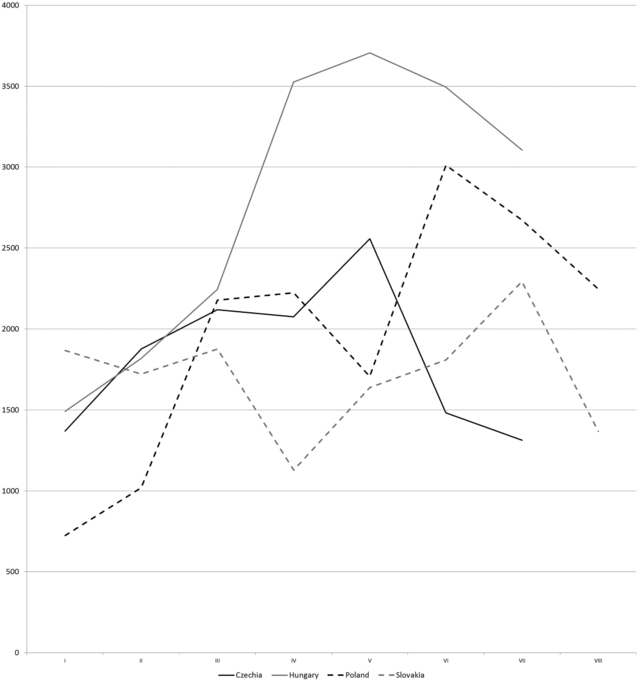

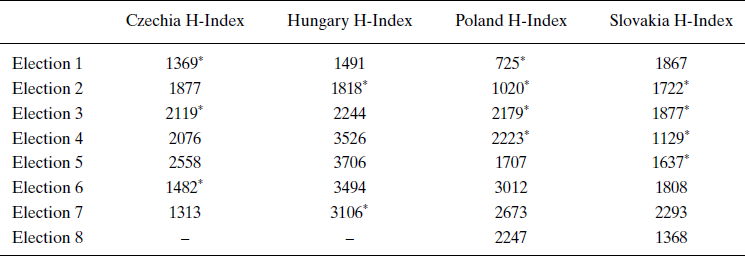

Figure 1 shows the time‐series of value changes in the country‐specific Herfindahl indices; since we do not posit any causal relationship between country‐level trends in the region, for the sake of simplicity the X axis shows the rank order of the respective elections in each country. Table 4 provides values for the Herfindahl indices of vote shares in each examined country.

Figure 1. Time‐series of value changes in the country‐specific Herfindahl indices.

Note: The X axis denotes the rank order of elections between 1990 and 2016 in each country. The conversions are as follows: Czechia: I: 1992, II: 1996, III: 1998, IV: 2002, V: 2006, VI: 2010, VII: 2013. Hungary: I: 1990, II: 1994, III: 1998, IV: 2002, V: 2006, VI: 2010, VII: 2014. Poland: I: 1991, II: 1993, III: 1997, IV: 2001, V. 2005, VI: 2007, VII: 2011, VIII: 2015. Slovakia: I: 1992, II: 1994, III: 1998, IV: 2002, V: 2006, VI: 2010, VII: 2012, VIII: 2016.

Table 4. Vote concentration in sample countries

Note: *Indicates that changes of entry barriers can be observed before the actual elections.

Czechia

In the Czech Republic, concentration in the market for parties (i.e., our dependent variable) changed in two major waves. The first wave started in 1992 and lasted until the third election in 1998. The 1996 election was the first during which two major parties competed for seats – the centre‐right ODS (Civic Democratic Party) and the centre‐left ČSSD (Czech Social Democratic Party). The party system became even more concentrated by the time of the next election in 1998. In the second wave from 2006 to 2013, the concentration index decreased – first drastically, then moderately.

As for our explanatory variables, entry barriers in the market for parties were changed on three occasions. First, the amendments adopted in 1994 and first applied during the 1996 elections were aimed at amending the rules concerning the establishment of party lists and party funding by the state (the electoral system remained unchanged during this reform). A new condition to establish a party list was introduced: a CZK200,000 electoral deposit was payable per electoral district. In effect, this required a CZK1.6 million deposit for each party that wanted to nominate a list in each of the eight electoral districts. This deposit was only refundable for parties that received at least 5 per cent of the votes in the general election.

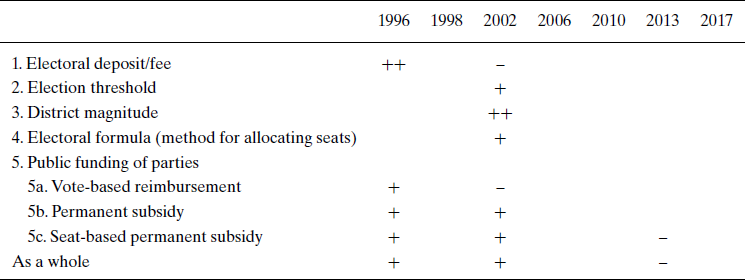

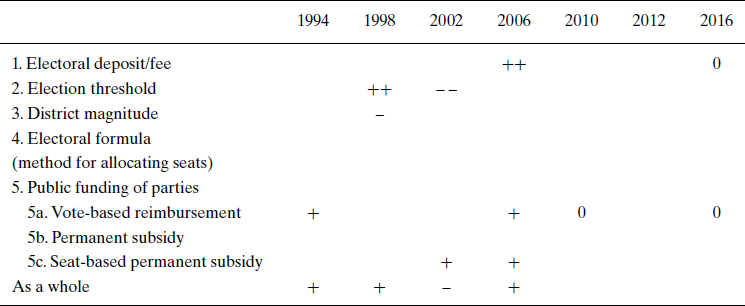

The package of funding rule amendments was aimed at meeting three objectives. It increased both the threshold of eligibility for state funding and the overall level of party funding, while introducing a brand‐new form of funding as well. For the reimbursement of electoral expenses based on the share of the votes received, the threshold for eligibility was increased from 2 to 3 per cent of votes. At the same time, the amount of funding available to this end was increased sixfold. The sum of the vote‐based permanent subsidy increased decisively as well, and a new seat‐based permanent subsidy was introduced. Table 5 provides an overview of the rule changes prior to 1996 and for all other elections in the period investigated.

Table 5. Pre‐election entry barrier changes in Czechia

Note: + and – indicate a change with limited, albeit still discernible impact. ++ denotes a more significant impact.

Another slew of changes was initiated during the 1998–2002 parliamentary cycle with a view towards resolving a brewing political crisis. After the impasse following the 1996 elections, the 1998 elections once again resulted in a political deadlock. Neither winner of the elections (the ODS in 1996 and the ČSSD in 1998) was able to form a majority government. The resolution came in the form of a pact according to which the social democrats established a single‐party minority government in 1998. This option was put on the table leading up to the so‐called ‘opposition agreement’. The minority government was supported by the opposition ODS in exchange for concessions by the new governing party (Roberts Reference Roberts2003). As a result, the amendments of the electoral law adopted by the two major parties in 2000 contained rules that benefited them. Even though it retained the proportional electoral system, it also introduced rules for the allocation of seats which disadvantaged smaller parties.

The law was eventually annulled by the Constitutional Court and was replaced by a watered‐down version. The actual amendments that entered into force in 2002 did not introduce radical changes, but they still contained elements that favoured big parties and decreased the level of fragmentation in order to help the creation of stable majority governments (for more details, see Birch et al. Reference Birch, Millard, Popescu and Williams2002: 85–86; Nikolenyi Reference Nikolenyi2003: 327–328). First, district magnitudes were decreased: in the previous electoral system, 25 seats were allocated in an average electoral district, which decreased to 14.3 as a result of the reform. At the same time, the electoral threshold regarding electoral coalitions was increased. A third element referred to the electoral system: the electoral formula changed from a two‐tier Hagenbach‐Bischoff method to the d'Hondt method, which slightly favours larger parties.

The rules concerning the state funding of parties also changed. The threshold for the one‐time vote‐based reimbursement was decreased from 3 to 1.5 per cent. Nevertheless, other reforms benefitted incumbent parties in the market for parties. Even as the vote‐based reimbursement increased moderately, the sum of the vote‐based permanent subsidy, which had been first introduced in 1994, showed a twofold increase. A similar rise applied to the seat‐based permanent subsidy. The issue of electoral deposits was a mixed bag from the perspective of our proposition concerning entry barriers. While the district‐level deposit was lowered, the fee was no longer refundable. In sum, the amendments preceding the 2002 elections led to higher entry barriers.

Hungary

Here we only provide a brief overview of major changes to the entry barriers in Hungary. We will discuss some developments in the Hungarian political system in more detail later in the article. Based on the analysis of the Herfindahl index, the period between 1990 and 2006 showed increasing concentration in the Hungarian party system.Footnote 4 Two alternating parties dominated the party system until 2010, the left‐wing Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) and the right‐wing Fidesz. Then, with the weakening of MSZP and the rise of Jobbik, a party positioned on the radical right, a new, trifurcated system emerged. Having said that, in view of the fact that an H‐index value of over 1800 indicates a concentrated market, the market for parties was still highly concentrated in terms of party list votes. The 2010 and 2014 elections did not lead to drastic changes in the established market structure. The concentration of seats held by each party practically stagnated, while the list‐based concentration indicator decreased, mainly because of the approximately 400,000 votes lost by Fidesz. Minority lists, a new element in the institutional setting, did not have a significant bearing on this state of affairs.

As for our explanatory variables, entry barriers in the Hungarian electoral system were changed on only two occasions. The first modification, enacted before the 1994 election, involved raising the threshold for party lists from 4 to 5 per cent of votes. With respect to the requirements for establishing party lists and nominating candidates, electoral regulations remained unchanged until 2010. Entry barriers were first set at a lower level before the 2014 elections: the number of required signatures that were to be collected in single‐member districts (SMDs) was reduced and voters now had the choice to recommend multiple candidates. Even with changes regarding the national list – for which more signatures were required as compared to the previous period – the net impact of entry condition changes pointed clearly towards lower barriers. Other than the aforementioned instances, the rules of nomination for regional and national compensation lists, winning seats in parliament and receiving a state subsidy were more or less stable throughout the period in question. Table 6 provides an overview of these rule changes.

Table 6. Pre‐election entry barrier changes in Hungary

Note: + and – indicate a change with limited, albeit still discernible impact.

Source: Own research, with additional data from Birch (2003: 134).

Poland

In Poland, the concentration of votes progressively increased between the first election in 1991 and the fourth in 2001. The 2005 election was an outlier in this trend, which continued until 2007. The last two elections showed a gradual decrease from the peak value in the sixth election. Along with Hungary, Poland also showed higher spreads between the minimum and maximum values of the Herfindahl index vis‐á‐vis the other two countries in the sample.

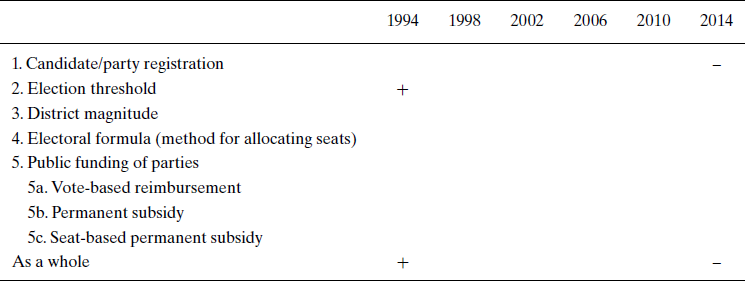

On the explanatory variable side, the Polish regulatory environment showed remarkable instability (Benoit & Hayden Reference Benoit and Hayden2004; Millard Reference Millard2010). It is useful to consider the rules preceding the 1991 elections when evaluating subsequent institutional changes. One characteristic of the ‘legacy’ regulation was the lack of an explicit parliamentary threshold: the 5 per cent threshold limited only the allocation of mandates from the national lists. This feature of the electoral system had a decisive impact: 29 different formations acquired at least one mandate in the Sejm and the party with the most votes received only 12.3 per cent of the votes cast. A string of government crises ensued resulting in early elections. The institutional changes that followed were almost exclusively aimed at increasing entry barriers in the market for parties.

The relevant rule changes are presented in Table 7. First, the 5 per cent threshold was extended to regional lists, and the threshold concerning the national list was increased to 7 per cent. Second, the number of electoral districts was increased, leading to smaller district magnitudes. The third amendment changed the electoral formula to the d'Hondt method, which, as we previously pointed out, slightly favours larger parties. Regarding state funding, a one‐off election refund was introduced, which exclusively benefitted parliamentary parties. There was only one aspect of these reforms that led to a lowering of entry barriers: the number of signatures required for registration was decreased to 3,000 from the former 5,000 per regional district.

Table 7. Pre‐election entry barrier changes in Poland

Note: + and – indicate a change with limited, albeit still discernible impact. ++ and – – denote a more significant impact. Minor changes are signaled with a 0.

A comprehensive system of government funding for parties was only established before the 1997 elections. The sum of the one‐off election refund provided to parliamentary parties was decisively increased. At the same time, a vote‐based permanent subsidy was introduced for parties that received at least 3 per cent of the votes. The electoral system was modified again before the 2001 elections. One of the arguments for amending the system was the ongoing administrative reform of Poland. Political developments also played a role: by early 2001, the left‐wing opposition party the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD) was a clear front‐runner in the upcoming elections. All other parties had a vested interest in making sure that the electoral system became more proportional so that the SLD did not win too overwhelmingly.

The electoral reforms that followed decreased the number of districts and also introduced a new formula which favoured smaller parties. The national list was also abolished. Furthermore, new rules applied to the government funding for parties. The one‐off refund was maximised at the level of actual expenditures and the vote‐based subsidy was changed to a tiered degressive schedule. In an interesting twist, the number of signatures required for registration of electoral committees was once again set at 5,000 per electoral district. The rules of 1993 were restored with regard to the electoral formula, which means that mandates were allocated on territorial lists according to the d'Hondt method preferring larger parties.

Slovakia

Slovakia stands out among the four countries with its relative stability in terms of the Herfindahl index. The spread between its highest and lowest values is around half of the same indicator for Poland or Hungary. The only longer wave of unidirectional value changes occurred between the fourth and seventh elections in 2002 and 2012, respectively.

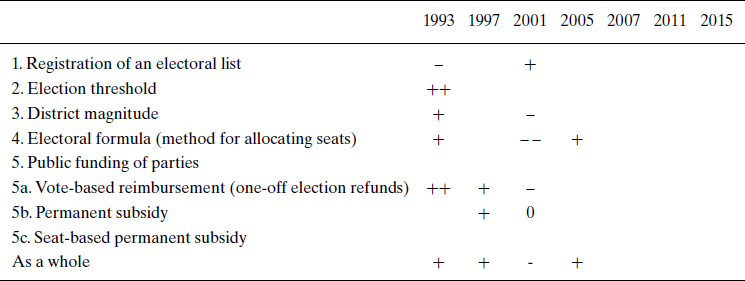

However, no similar stability was detectable on the explanatory variable side. In fact, the 2012 election was the only one during the examined period that was not associated with a preceding amendment of the relevant rules. The first changes, adopted before the 1994 elections, concerned the voter‐based reimbursement. In terms of their general approach, the amendments were similar to those in the Czech case: both the threshold for eligibility and the sum of the subsidy were increased. The next institutional change was enacted a few months before the 1998 elections. It radically increased the threshold requirements for establishing a joint list by multiple parties. The aim of this amendment was to hinder the efforts of anti‐Mečiar democratic forces and the parties of ethnic Hungarians living in Slovakia in setting‐up a competitive opposition list (Lebovič Reference Lebovič, Bútora, Mesežnikov, Bútorová and Fisher1999). The rule changes prior to 1994 and all other elections in the period are summarised in Table 8.

Table 8. Pre‐election entry barrier changes in Slovakia

Note: + and – indicate a change with limited, albeit still discernible impact. ++ and – – denote a more significant impact. Minor changes are signaled with a 0.

A second modification concerned district magnitude. Slovakia was divided into four territorial districts up until the 1998 election and the rule changes of the time created a single electoral district. Although in theory a larger district magnitude ensures a more proportional allocation of mandates, it needs to be emphasised that the district in Slovakia had been fairly large to start with. In all, 12 seats were allocated in the smallest electoral district and a further 40–50 seats was available in each of the other three districts. As a consequence, the single, national‐level electoral district did not significantly increase the chance for small parties to gain parliamentary seats. All in all, the 1998 reforms resulted in higher entry barriers for parties.

During the 1998–2002 parliamentary cycle the institutional variables changed in two respects. The rules from before 1998 concerning electoral coalitions were restored, which made it easier for smaller parties to enter parliament. A seat‐based permanent subsidy was also introduced. Finally, the reforms adopted in 2004 led to a comprehensive increase of entry barriers. First, a relatively high electoral deposit of SKK500,000 was introduced, which was refundable for parties that acquired at least 3 per cent of the votes (this eligibility threshold was lowered before the 2006 elections). Second, the vote‐based reimbursement was tied to nominal average salary, which is a decisive increase. Third, both the seat‐based permanent subsidy and the vote‐based reimbursement were tied to nominal average salary.

Summary of comparative results

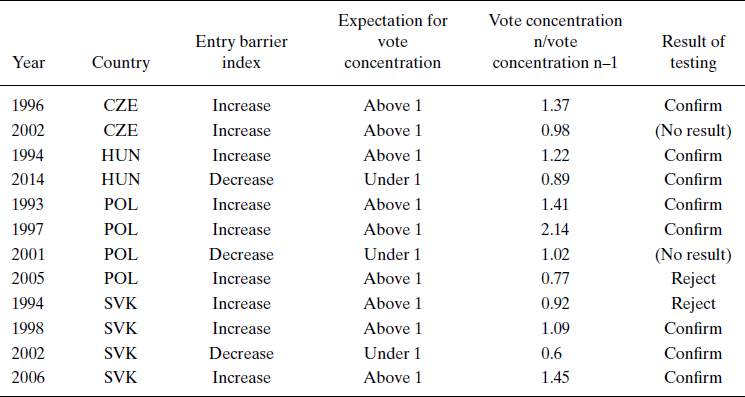

Our hypothesis posited that the modification of entry barriers in the market for parties leads to changes in the concentration of the popular vote for party lists. Table 9 provides an overview of our results with respect to this hypothesis.

Table 9. Party vote concentration change in four countries

From the ten instances when the change in concentration exceeded 5 per cent, we confirmed the hypothesis for eight observations. This is an 80 per cent success rate, which drops to 67 per cent if the ‘no results’ are also included. A basic linear regression of the institutional change dummy on the H‐index associated with these cases yielded a strong but non‐significant result (r = 0.511 with a standard error of 1.76). Nevertheless, the usual cautionary notes apply: only a larger sample could yield sufficiently valid results with respect to the hypothesis and the given region/period.

Similarly, country‐specific results should be treated with even greater caution due to the low number of observations. On the one hand, Hungary is the best‐behaved in this respect with a 100 per cent confirmation rate. On the other hand, the hypothesis did not have a clear‐cut predictive value for Poland, where two confirms are set against one reject and an excluded case. Results for Czechia and Slovakia are mostly positive, but only if we exclude value changes under 5 per cent for the former.

One of the most important contingencies of this analysis is that party vote concentration as indicated by Herfindahl index values may be affected by variables other than entry barriers. Under ideal conditions this qualification would not interfere with our test of the hypothesis since we only contend that, ceteris paribus, entry barrier changes should have an impact on party vote concentration. A further analysis of ‘reject’ cases could shed a light on factors that upset the ceteris paribus condition. By including these control variables in the analysis, and by increasing the number of observations, we could arrive at a more precise picture of the causal mechanism linking entry barriers and the structure of party markets.

Discussion

The logic of strategic entry barrier changesFootnote 5

Our comparative analysis lends support to our hypothesis regarding the effect of entry barrier changes on political market structure. Nevertheless, it only describes a correlation between the observed variables and our causal inferences are mainly based on the element of time: changes in market structure followed entry barrier changes. In order to better understand the causal logic linking institutional and market structure change, we have to look under the hood of our theory of political markets.

In our view, the strategic behaviour of incumbent parties offers insights concerning the logic of entry barrier changes. By ‘incumbent parties’ we mean (1) a single‐party majority government, or (2) a coalition party majority government at the time when the rule changes were enacted. The incumbent parties have both the incentives (a necessary condition) and the parliamentary majority (a sufficient condition) for acting on those incentives. One such case was the electoral reform in Slovakia before 1998. The reform proposal was supported by three coalition parties while the opposition and new parties outside parliament were opposed. Provided that the interests of the parties forming the coalition are aligned, the logic of entry barrier changes prescribes the lowering of entry barriers in the market for parties and increasing the level of entry barriers on the market for government. This may be achieved, inter alia, by a loosening of the rules of candidacy, on the one hand, and the introduction of a majority compensation system, on the other.

Needless to say, many special cases pose a challenge to this generic description of strategic incumbent behaviour. First, the natural alignment of interests between coalition partners is generally far from automatic. Second, a separate large party‐small party dynamic may also come into play when major government and opposition parties form an alliance to pass legislation that manipulates entry barriers to the detriment of smaller parties and out‐of‐parliament challengers. We presented the case of the post‐1998 electoral reforms in Czechia. These reforms were the result of an ‘opposition agreement’ between the ČSSD and the opposition party ODS. Other, smaller parties in parliament opposed this compact, which clearly shows that the dynamic that was at play here was different from a standard government‐opposition scenario.

Finally, institutional changes may also have unintended consequences that interfere with how the posited relationship between entry barrier modifications and market structure changes play out in real‐life politics. Many other factors may have a bearing on the market concentration in the market for parties besides institutional changes concerning entry barriers. Having said that, our aim was not to explain the causes of market structure change but to explore the proposed relationship between one type of institutional change (entry barrier change) and market structure change. These special cases notwithstanding, the logic of multi‐market entry barrier changes may provide an explanation for the causal relationship between institutional change and market structure change. The mechanism of strategic entry barrier change would be best illustrated by in‐depth descriptions of individual cases. Here, we offer one such example: the effects of the electoral rule changes in Hungary in 2011.

A case study of strategic entry barrier changes

For 20 years, Hungary showed remarkable stability in CEE in terms of its electoral rules. This created a favourable setting for a quasi‐experiment regarding the effects of entry barriers on political markets. The Hungarian case also offers a clear‐cut implementation of the strategic behaviour that is a corollary of our underlying hypothesis. Ágh (Reference Ágh1995) considered the Hungarian party system ‘stable’, while Toole (Reference Toole2000) emphasised how it stabilised ‘much more quickly than expected’ and how it was ‘already nearly as stable as more mature party systems’. Toole also went on to suggest that stabilisation is partly ‘the product of … electoral system design’.

Even as Kitschelt et al. (Reference Kitschelt, Mansfeldová, Markowski and Tóka1999: 118) portray the Hungarian party system as one combining ‘volatility and stability’, they highlight the fact that there was a ‘drop’ in both electoral and legislative fragmentation over time. Enyedi (Reference Enyedi, Katz and Crotty2006: 231) confirms this tendency by noting that only one new parliamentary party emerged over a decade of political development. Enyedi and Tóka (Reference Enyedi, Tóka, Webb and White2007: 172) go as far as to claim that this consolidated nature of the Hungarian party system poses a ‘puzzle’ in light of the social and economic turbulence in the surrounding region during this period.

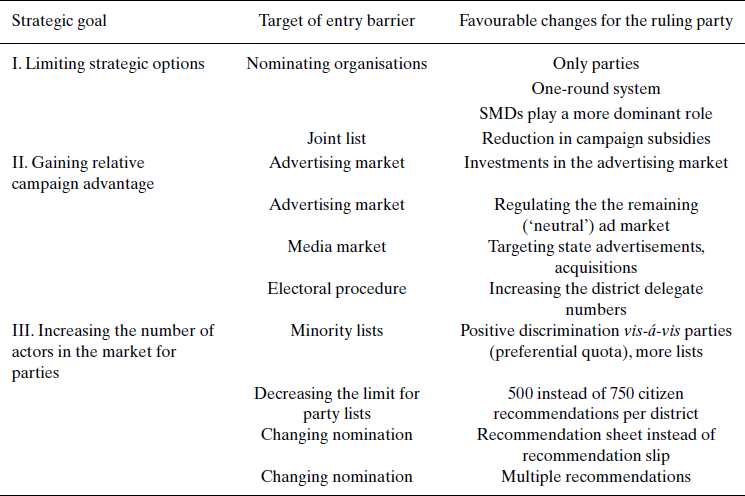

After its election victory in 2010 the governing Fidesz party began to radically reshape the country's constitutional arrangements. One important element in the changes adopted was the promise to reduce the size of the Hungarian parliament, the National Assembly, which provided the majority with legitimate grounds for rewriting the electoral and parliamentary rules. The changes included many components that were not closely connected to entry barriers but affected the ‘auction’ in the market for government: an important example is the redrawing of the SMD boundaries. Competition in the market for government, therefore, was highly affected by the changes in the regulations for the market for parties.

In the competition for a natural monopoly, the incumbent's short‐term goal was to limit the strategic options of major competitors; to gain a relative campaign advantage (in terms of finances, in‐kind contributions, media); and to increase the number of the actors in the market for parties without significantly decreasing the concentration, as the fragmentation of the opposition was also an important goal. Table 10 provides a summary of these developments.

Table 10. Strategic decisions influencing the market for parties and government

Note: SMDs = Single‐member districts.

The first and most important tool of limiting strategic options was to change the two‐round election system (with a run‐off) into a one‐round system. This effect was reinforced by changing the ratio of list‐based and SMD seats, and as a result the majority of MPs were now elected in single‐member constituencies. The strategic options of the opposition narrowed because the election campaign, which was based on joint candidates in the SMDs but separate national party lists, caused a cacophony and several strategic U‐turns on the opposition side. Though this particular outcome could not have been predicted at the time when the corresponding rules were amended, the targeted change of the incentives pertaining to entry barriers was certainly a conscious decision on the part of Fidesz. A specific example was the newly raised threshold for parties which nominated a joint national list, which applied to the case of the Together party (Együtt‐PM) in its capacity as a competitor of MSZP: in a more proportional two‐round system, fewer voters would have had to split their votes in the first round, and the result might have been a clearer and thus more successful strategy for the challengers (also see the example of the Alliance of Free Democrats [SZDSZ] between 1998 and 2006). Third, the regulation of campaign costs hedged the risk of a joint left‐wing list by giving the actors significantly diminished resources as compared to what they would have received had they competed separately.

These and other strategic moves by Fidesz present a classic case of incumbent strategy in political markets: decreasing the entry barriers at the middle level of the pyramid while increasing them at the top. A series of other measures meant to buttress this strategy, which eventually resulted in an explosion in the number of party lists, with as many as 18 national party lists were registered in 2014, as opposed to only six in 2010. This was the result of a deliberate decision to open up the market for parties. In so doing, Fidesz exploited its incumbent position in the market for government in order to create a vertically integrated political venture at all three levels of the political market.

Although the Hungarian example offers the most clear‐cut case for the incumbent strategy described above, many other electoral reforms can be traced back to one version or the other of the generic strategy of exploiting the possibilities of entry barrier manipulation. The 1998 amendments of the electoral law in Slovakia, which raised the threshold for pre‐electoral coalitions and restricted parties’ access to the media, was a reflection of a similar strategy on the part of the then‐ruling People's Party (HZDS).

Conclusion

In this article we have investigated the impact of electoral reforms on entry barriers in political markets. We presented a theory of political markets which made use of the concept of three different political markets: the markets for participation, parties and government. Based on this theoretical framework, we analysed a hypothesis which posited that the modification of the entry barriers in the market for parties leads to changes in the concentration of the popular vote for party lists. This proposition was empirically tested by a comparative analysis of a new database covering Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia. Our analysis found empirical support for the proposition: in most cases the changes in the entry barriers led to a corresponding adjustment of concentration in the market for parties.

In conclusion, we would like to discuss how our study adds to the existing literature and also briefly evaluate its generalisability. Our contributions are twofold: theoretical and empirical. As for theory, the notion of political markets has not been used as a core concept in recent party systems literature. Explicit discussions of entry barriers in their original economic sense are also few and far between in this field of research in general, and the same holds for the CEE region as well.

Nevertheless, the concepts of ‘political markets’ and ‘entry barriers’ offer a simple yet powerful analytical framework for understanding political developments in the countries in question. Therefore, we proposed a theoretical framework that both draws on and moves beyond existing accounts of political markets in formulating the notion of the political pyramid consisting of three levels of political markets. A typology of entry barriers is also provided, along with its operationalisation for empirical political research.

Our main empirical contributions are a new database of electoral reforms related to entry barriers in the Visegrad countries and the comparative analysis of this database. The database, which is described in part in the main text and also in the Online Appendix, offers a standardised way of examining market structure and entry barrier changes. In our research design, we opted for a qualitative analysis of these variations due to the small number of observations in our four‐country sample spanning over two decades.

Nevertheless, there are no obvious obstacles to the generalisation of the empirical research design to extend to other advanced democracies, for large‐N studies and the corresponding application of quantitative methods. A weighted index of the different types of rule changes for any given electoral cycle would be a straightforward solution for generalising the explanatory variable for such a quantitative design. Similarly, on the dependent variable side, results of the Herfindahl index are also ready‐made for regression analysis.

Similarly, the theoretical framework itself is not specific to the region investigated in this article. Thus, the external validity of our proposition lends itself to replication – indeed, this may be an easier task in the context of regions and countries where entry barriers have been more extensively scrutinised. This summary of the pros and cons of our approach also highlights two issues in the literature that would deserve a more detailed treatment in the context of our empirical framework. First, no universal tendency regarding the concentration/fragmentation of the Visegrad party systems is discernible from available data. As several scholars noted in the past decade, the related indicators show substantial variations on a country‐by‐country basis (Bielasiak Reference Bielasiak2002: 202–206; Krupavičius Reference Krupavičius2005: 41; Rose & Munro Reference Rose and Munro2009: 24–29).Footnote 6 From a methodological perspective we also argued above that, while it offers simple and useful metrics for our present purposes, the Herfindahl index is not able to capture every relevant aspect of a given party constellation. For instance, it is striking that the concrete list of parties contesting elections in our sample countries has seen a radical rearrangement over the decades.Footnote 7 Applying the weighted party age index – an indicator developed by Kreuzer and Pettai (Reference Kreuzer and Petai2011) – to the party systems of CEE, Haughton and Deegan‐Krause (Reference Haughton and Deegan‐Krause2015: 62–64) pointed out that the Hungarian and Czech party systems proved to be quite ‘mature’, while Poland and Slovakia have been characterised by constant replacement and reinvention. These results show that further methodological refinements in accounting for party system structure are very much in order beyond the basic method applied in this study.

Second, our topic is strongly related to a widespread discussion on the erosion of democracy and the so‐called ‘democratic backsliding’ in our examined region (Ágh Reference Ágh2013; Greskovits Reference Greskovits2015; Hanley et al. Reference Hanley, Dawson and Cianetti2018; Sedelmeier Reference Sedelmeier2014; Hanley & Vachudova Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018). Sadurski (Reference Sadurski2018) provides an overview of recent developments in the Polish constitutional crisis (see also Halász Reference Halász2017), while Stumpf (Reference Stumpf2017) investigated whether we can observe a democratic backsliding or a paradigm shift in Poland and Hungary from the perspective of constitutionalism, the separation of powers and judicial independence.Footnote 8

Many authors link the general notion of democratic backsliding to the manipulation of electoral rules as a major component. Bermeo (Reference Bermeo2016: 6) provides an historical overview of the forms of democratic backsliding and emphasises that nowadays ‘longer‐term strategic harassment and manipulation’ is found more often than vote frauds carried out on election day. Waldner and Lust (Reference Waldner and Lust2018: 1) proxies democratic backsliding with the undermining of competitive elections, with less accountable governments and less powerful citizens. They define electoral procedures as the main area of changes in times of democratic backsliding besides civil and political liberties and accountability, and they claim that the concept of ‘backsliding’ means changes affecting these three factors negatively (Waldner & Lust Reference Waldner and Lust2018: 2–3). Further to our point, Ekiert (Reference Ekiert2017: 6) mentions amendments of certain electoral rules in a similar context. In light of this evolving literature, we re‐emphasise that the only purpose of our investigation is to highlight the causal mechanism connecting electoral rules and party system concentration. Having said that, if this mechanism is confirmed, our analysis may offer added value to this more general – and from a normative aspect: more consequential – conversation.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Anne Küppers, Vlastimil Havlík, Kamil Marcinkiewicz, Peter Spáč and Janne Tukiainen for their comments on a previous draft. We thank the three anonymous reviewers for their useful comments. We take responsibility for all remaining errors.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Online Appendix.