1. Introduction

Let

![]() $\Gamma$

be a finite subgroup of

$\Gamma$

be a finite subgroup of

![]() $SL_2(\mathbb{C})$

and let

$SL_2(\mathbb{C})$

and let

![]() $X=\mathbb{C}^2/\Gamma$

be the corresponding Kleinian surface singularity. The McKay correspondence famously relates the representation theory of

$X=\mathbb{C}^2/\Gamma$

be the corresponding Kleinian surface singularity. The McKay correspondence famously relates the representation theory of

![]() $\Gamma$

to the geometry of the minimal resolution

$\Gamma$

to the geometry of the minimal resolution

![]() $\widetilde {X}\to X$

. Initially a combinatorial observation [Reference McKayMcK80], it is now understood that we should consider the orbifold

$\widetilde {X}\to X$

. Initially a combinatorial observation [Reference McKayMcK80], it is now understood that we should consider the orbifold

as another possible crepant resolution of

![]() $X$

, and then other formulations of the correspondence should follow. For example, there is an equivalence of derived categories

$X$

, and then other formulations of the correspondence should follow. For example, there is an equivalence of derived categories

![]() $D^b(\widetilde {X}) \cong D^b(\mathcal{X})$

[Reference Kapranov and VasserotKV00, Reference Bridgeland, King and ReidBKR01], which is an instance of the general prediction that all crepant resolutions of a given singularity should be derived equivalent. There are also results relating Gromov–Witten invariants of

$D^b(\widetilde {X}) \cong D^b(\mathcal{X})$

[Reference Kapranov and VasserotKV00, Reference Bridgeland, King and ReidBKR01], which is an instance of the general prediction that all crepant resolutions of a given singularity should be derived equivalent. There are also results relating Gromov–Witten invariants of

![]() $X$

and of

$X$

and of

![]() $\mathcal{X}$

[Reference Bryan and GholampourBG09, Reference RuanRua06].

$\mathcal{X}$

[Reference Bryan and GholampourBG09, Reference RuanRua06].

One may also ask whether this birational equivalence

can be realised via variation of geometric invariant theory (VGIT). This means looking for some larger variety

![]() $Z$

, with an action of a reductive group

$Z$

, with an action of a reductive group

![]() $G$

, such that both

$G$

, such that both

![]() $X$

and

$X$

and

![]() $\mathcal{X}$

appear as possible geometric invariant theory (GIT) quotients

$\mathcal{X}$

appear as possible geometric invariant theory (GIT) quotients

![]() $Z{/\!/}_\theta G$

for different choices of stability condition

$Z{/\!/}_\theta G$

for different choices of stability condition

![]() $\theta$

.

$\theta$

.

For type

![]() $A$

this question is easy. All the spaces involved are toric, and standard toric geometry techniques produce the requested construction immediately, with

$A$

this question is easy. All the spaces involved are toric, and standard toric geometry techniques produce the requested construction immediately, with

![]() $G$

a torus and

$G$

a torus and

![]() $Z$

a vector space (see Example 2.2). But for types D and

$Z$

a vector space (see Example 2.2). But for types D and

![]() $E$

where

$E$

where

![]() $\Gamma$

is non-abelian it is much less obvious how to proceed.

$\Gamma$

is non-abelian it is much less obvious how to proceed.

In this paper we write down an explicit

![]() $Z$

and

$Z$

and

![]() $G$

which answer the question above for the simplest non-abelian case,

$G$

which answer the question above for the simplest non-abelian case,

![]() $D_4$

. Here,

$D_4$

. Here,

![]() $\Gamma$

is the quaternion group

$\Gamma$

is the quaternion group

![]() $Q$

, aka the binary dihedral group

$Q$

, aka the binary dihedral group

![]() $BD_2$

. It sits in

$BD_2$

. It sits in

![]() $SL_2$

as the double cover of the dihedral group

$SL_2$

as the double cover of the dihedral group

![]() $D_2 \cong (\mathbb{Z}_2)^2\subset SO_3$

.

$D_2 \cong (\mathbb{Z}_2)^2\subset SO_3$

.

Our construction of

![]() $Z$

, presented in Section 3, is a little involved. It is the vanishing locus of an explicit set of equations in a 13-dimensional vector space, carrying a natural action of the group

$Z$

, presented in Section 3, is a little involved. It is the vanishing locus of an explicit set of equations in a 13-dimensional vector space, carrying a natural action of the group

![]() $G=(\mathbb{C}^*)^3\times GL_2$

. Moreover, our proof that both

$G=(\mathbb{C}^*)^3\times GL_2$

. Moreover, our proof that both

![]() $X$

and

$X$

and

![]() $\mathcal{X}$

do arise as GIT quotients of

$\mathcal{X}$

do arise as GIT quotients of

![]() $Z$

by

$Z$

by

![]() $G$

requires quite of lot of hands-on verification.

$G$

requires quite of lot of hands-on verification.

But behind the messy details there lies a general ansatz, outlined by the first author and Chan in [Reference Abdelgadir and ChanAC23] and reviewed in our Section 2. Furthermore this ansatz applies in principle to any finite quotient singularity. So it would be a worthwhile goal to replace our hands-on proof with a more abstract and elegant one, which might then work in greater generality.

Remark 1.1. It is perhaps surprising, given the extensive literature on the McKay correspondence, that such a construction has not appeared before. The reason is that most previous approaches have focused on constructing the minimal resolution

![]() $X$

as a moduli space of modules (or sheaves, or quiver representations or

$X$

as a moduli space of modules (or sheaves, or quiver representations or

![]() $G$

-clusters). And since modules never have finite non-trivial stabilizer groups this approach can never produce the orbifold resolution.

$G$

-clusters). And since modules never have finite non-trivial stabilizer groups this approach can never produce the orbifold resolution.

Remark 1.2. In this paper, when we discuss ‘GIT quotients’ what we really mean is the stack-theoretic quotient of the semistable locus. Over the stable locus this just means taking the quotient as a Deligne-Mumford stack rather than as a variety with finite quotient singularities, which is obviously essential for our purposes.

If there were any strictly semistable points then the quotient stack would differ more radically from the quotient variety, since it is an Artin stack, and S-equivalent orbits are not identified. But we shall show that are no strictly semistable points in our construction.

Remark 1.3. Ideally, our construction would have brought the type

![]() $D_4$

McKay correspondence into the framework of Gauged Linear Sigma Models, with all the accompanying string-theoretic techniques [Reference WittenWit93]. Unfortunately, since our

$D_4$

McKay correspondence into the framework of Gauged Linear Sigma Models, with all the accompanying string-theoretic techniques [Reference WittenWit93]. Unfortunately, since our

![]() $Z$

is not a complete intersection (see Remarks 3.4 and 3.15) it is not clear that we have achieved this.

$Z$

is not a complete intersection (see Remarks 3.4 and 3.15) it is not clear that we have achieved this.

2. The Tannakian approach

Suppose we have a finite group

![]() $\Gamma$

acting linearly on a vector space

$\Gamma$

acting linearly on a vector space

![]() $V$

, and a corresponding orbifold

$V$

, and a corresponding orbifold

![]() $\mathcal{X}=[V/\Gamma ]$

. How can we produce

$\mathcal{X}=[V/\Gamma ]$

. How can we produce

![]() $\mathcal{X}$

as a GIT quotient?

$\mathcal{X}$

as a GIT quotient?

As stated, this question is trivial since

![]() $\mathcal{X}$

is the GIT quotient of

$\mathcal{X}$

is the GIT quotient of

![]() $V$

by

$V$

by

![]() $\Gamma$

. But what if we ask for a construction in which

$\Gamma$

. But what if we ask for a construction in which

![]() $\mathcal{X}$

is one of several possible quotients? Or we can simplify by ignoring

$\mathcal{X}$

is one of several possible quotients? Or we can simplify by ignoring

![]() $V$

. Then the question becomes something like: How can we produce the stack

$V$

. Then the question becomes something like: How can we produce the stack

![]() $B\Gamma$

as a GIT quotient

$B\Gamma$

as a GIT quotient

![]() $Z{/\!/}_\theta G$

, where the group

$Z{/\!/}_\theta G$

, where the group

![]() $G$

is some reductive group with a character lattice of positive rank?

$G$

is some reductive group with a character lattice of positive rank?

Tannakian duality gives us a heuristic way to approach this problem. What we need is a presentation of the representation category

![]() $\textrm {Rep}\Gamma$

. By this we mean something like the following data.

$\textrm {Rep}\Gamma$

. By this we mean something like the following data.

-

(i) A finite list of irreps

$U_1,\ldots , U_k$

which generate all

$U_1,\ldots , U_k$

which generate all

$\Gamma$

-representations under tensor products.

$\Gamma$

-representations under tensor products. -

(ii) A finite list of isomorphisms

where \begin{align*}B_t : {\mathcal{U}}_t \stackrel {\sim }{\longrightarrow } \mathcal{V}_t, \end{align*}

\begin{align*}B_t : {\mathcal{U}}_t \stackrel {\sim }{\longrightarrow } \mathcal{V}_t, \end{align*}

${\mathcal{U}}_t$

and

${\mathcal{U}}_t$

and

$\mathcal{V}_t$

are some given combinations of the

$\mathcal{V}_t$

are some given combinations of the

$U_i$

values, formed by sums, products and images of Schur functors. Composites of these

$U_i$

values, formed by sums, products and images of Schur functors. Composites of these

$B_t$

values should generate all isomorphisms in

$B_t$

values should generate all isomorphisms in

$\textrm {Rep}\Gamma$

in some appropriate sense. In particular, they should give isomorphisms of

$\textrm {Rep}\Gamma$

in some appropriate sense. In particular, they should give isomorphisms of

$U_i \otimes U_j$

with direct sums of irreps of

$U_i \otimes U_j$

with direct sums of irreps of

$\Gamma$

.

$\Gamma$

.

-

(iii) A finite list of relations that hold between the

$B_t$

values, generating all such relations.

$B_t$

values, generating all such relations.

From these data we can build a GIT problem, as follows. Treat the

![]() $U_i$

values just as a list of vector spaces, of dimensions

$U_i$

values just as a list of vector spaces, of dimensions

![]() $d_1,\ldots , d_k$

. Then the

$d_1,\ldots , d_k$

. Then the

![]() $B_t$

values collectively form an element of the vector space

$B_t$

values collectively form an element of the vector space

\begin{align*}H = \bigoplus _{t=1}^s \textrm {Hom}({\mathcal{U}}_t, \mathcal{V}_t), \end{align*}

\begin{align*}H = \bigoplus _{t=1}^s \textrm {Hom}({\mathcal{U}}_t, \mathcal{V}_t), \end{align*}

which carries a natural action of the group

and the relations (iii) cut out a

![]() $G$

-invariant subvariety

$G$

-invariant subvariety

![]() $Z\subset H$

. There is an open set

$Z\subset H$

. There is an open set

![]() $H^o\subset H$

where each

$H^o\subset H$

where each

![]() $B_t$

is an isomorphism and a corresponding open set

$B_t$

is an isomorphism and a corresponding open set

Tannakian duality guarantees that the stabilizer group of any point in

![]() $Z^o$

is our finite group

$Z^o$

is our finite group

![]() $\Gamma$

, so at the very least we have a point in the GIT quotient stack that has the correct isotropy. What we would still have to check is that:

$\Gamma$

, so at the very least we have a point in the GIT quotient stack that has the correct isotropy. What we would still have to check is that:

-

•

$Z^o$

is the semistable locus for some stability condition

$Z^o$

is the semistable locus for some stability condition

$\theta$

; and

$\theta$

; and -

•

$G$

acts transitively on

$G$

acts transitively on

$Z^o$

.

$Z^o$

.

If these two conditions hold then the GIT quotient

![]() $Z{/\!/}_\theta G$

is

$Z{/\!/}_\theta G$

is

![]() $B\Gamma$

.

$B\Gamma$

.

Let us suppose that we have solved this problem, and return to our original problem of constructing

![]() $[V/\Gamma ]$

. The vector space

$[V/\Gamma ]$

. The vector space

![]() $V$

is a

$V$

is a

![]() $\Gamma$

-representation, so some combination of the irreps

$\Gamma$

-representation, so some combination of the irreps

![]() $U_1,\ldots , U_k$

, and there is a corresponding

$U_1,\ldots , U_k$

, and there is a corresponding

![]() $G$

-representation which we could also denote by

$G$

-representation which we could also denote by

![]() $V$

. The obvious candidate solution to our problem is to take the variety

$V$

. The obvious candidate solution to our problem is to take the variety

![]() $Z\times V$

with its action of

$Z\times V$

with its action of

![]() $G$

. If we can find a stability condition

$G$

. If we can find a stability condition

![]() $\theta$

such that the

$\theta$

such that the

![]() $\theta$

-semistable locus is

$\theta$

-semistable locus is

![]() $Z^o\times V$

, and

$Z^o\times V$

, and

![]() $G$

acts transitively on

$G$

acts transitively on

![]() $Z^o$

, then

$Z^o$

, then

And there are certainly other possible GIT quotients since the character lattice of

![]() $G$

has rank

$G$

has rank

![]() $k$

. We can hope to find geometric resolutions of

$k$

. We can hope to find geometric resolutions of

![]() $V/\Gamma$

amongst these other possible quotients.

$V/\Gamma$

amongst these other possible quotients.

Remark 2.1. If

![]() $\Gamma$

lies in

$\Gamma$

lies in

![]() $SL(V)$

then the singularity

$SL(V)$

then the singularity

![]() $V/\Gamma$

is Gorenstein and the orbifold

$V/\Gamma$

is Gorenstein and the orbifold

![]() $[V/\Gamma ]$

is a crepant resolution, so we could hope to get crepant geometric resolutions amongst the other resolutions. In our main example

$[V/\Gamma ]$

is a crepant resolution, so we could hope to get crepant geometric resolutions amongst the other resolutions. In our main example

![]() $\Gamma =Q$

(Section 3) this does indeed happen. But we have not been able to find an a priori reason why these other quotients, even if they are resolutions, should be crepant.

$\Gamma =Q$

(Section 3) this does indeed happen. But we have not been able to find an a priori reason why these other quotients, even if they are resolutions, should be crepant.

Example 2.2. Let

![]() $\Gamma$

be the cyclic group

$\Gamma$

be the cyclic group

![]() $C_n$

. Then

$C_n$

. Then

![]() $\textrm {Rep} \Gamma$

is generated by a single 1-dimensional irrep

$\textrm {Rep} \Gamma$

is generated by a single 1-dimensional irrep

![]() $U$

, subject to the single isomorphism:

$U$

, subject to the single isomorphism:

There are no relations to impose on

![]() $B$

.

$B$

.

Now we can build our GIT problem. The group

![]() $G$

is

$G$

is

![]() $\textrm {GL}(U)\cong \mathbb{C}^*$

, acting on the vector space

$\textrm {GL}(U)\cong \mathbb{C}^*$

, acting on the vector space

![]() $H=\textrm {Hom}(U^{\otimes n}, \mathbb{C})$

. So

$H=\textrm {Hom}(U^{\otimes n}, \mathbb{C})$

. So

![]() $H$

is 1-dimensional with a

$H$

is 1-dimensional with a

![]() $\mathbb{C}^*$

action of weight

$\mathbb{C}^*$

action of weight

![]() $-n$

, and

$-n$

, and

![]() $Z=H$

. For one of the two possible stability conditions it is indeed true that the semistable locus is

$Z=H$

. For one of the two possible stability conditions it is indeed true that the semistable locus is

![]() $Z^0\cong \mathbb{C}^*$

, and the

$Z^0\cong \mathbb{C}^*$

, and the

![]() $G$

-action on this is transitive, so

$G$

-action on this is transitive, so

(the other GIT quotient is empty).

Now consider the type

![]() $A_{n-1}$

Kleinian singularity

$A_{n-1}$

Kleinian singularity

![]() $X = V/C_n$

, where

$X = V/C_n$

, where

Our candidate for constructing resolution of this singularity is the larger GIT problem

![]() $Z\times V$

, which is simply

$Z\times V$

, which is simply

![]() $\mathbb{C}^3$

carrying a

$\mathbb{C}^3$

carrying a

![]() $\mathbb{C}^*$

action of weights

$\mathbb{C}^*$

action of weights

![]() $(-n, 1, n-1)$

. We see that one of the GIT quotients is indeed the orbifold resolution

$(-n, 1, n-1)$

. We see that one of the GIT quotients is indeed the orbifold resolution

![]() $[V/C_n]$

.

$[V/C_n]$

.

The other generic GIT quotient is a non-affine orbifold given by the total space of the canonical bundle on the weighted projective line

![]() $\mathbb{P}^1_{1:n-1}$

. This is another crepant resolution of the singularity

$\mathbb{P}^1_{1:n-1}$

. This is another crepant resolution of the singularity

![]() $X$

.

$X$

.

If we want the fully geometric (i.e. non-orbifold) resolution we need a more redundant presentation of

![]() $\textrm {Rep} C_n$

. We take all the non-trivial characters

$\textrm {Rep} C_n$

. We take all the non-trivial characters

![]() $U_1,\ldots , U_{n-1}$

, and isomorphisms

$U_1,\ldots , U_{n-1}$

, and isomorphisms

There are still no relations. This leads us to a GIT problem

with an action of the torus

![]() $\prod _i GL(U_i)\cong (\mathbb{C}^*)^{n-1}$

. All GIT quotients will be toric surfaces, and indeed this is just the standard construction of the surface

$\prod _i GL(U_i)\cong (\mathbb{C}^*)^{n-1}$

. All GIT quotients will be toric surfaces, and indeed this is just the standard construction of the surface

![]() $\widetilde {X}$

which minimally resolves the

$\widetilde {X}$

which minimally resolves the

![]() $A_n$

singularity. The orbifold

$A_n$

singularity. The orbifold

![]() $[V/C_n]$

appears as another of the possible quotients.

$[V/C_n]$

appears as another of the possible quotients.

In the previous example we avoided having relations on the

![]() $B_t$

values. But when we move to non-abelian cases the relations are essential, and in practice are the hardest part of implementing our ansatz.

$B_t$

values. But when we move to non-abelian cases the relations are essential, and in practice are the hardest part of implementing our ansatz.

Example 2.3. Let

![]() $\Gamma = S_3$

. We present this case both because it is the smallest non-abelian group but also because it shares some similarities with the group

$\Gamma = S_3$

. We present this case both because it is the smallest non-abelian group but also because it shares some similarities with the group

![]() $Q$

which is the focus of Section 3.

$Q$

which is the focus of Section 3.

The irreps of

![]() $S_3$

can be generated from the single 2d irrep

$S_3$

can be generated from the single 2d irrep

![]() $U$

, and there is an isomorphism

$U$

, and there is an isomorphism

The second component of

![]() $B$

gives an inner product

$B$

gives an inner product

which extends to an inner product on

![]() $U\oplus \mathbb{C}$

. But the space

$U\oplus \mathbb{C}$

. But the space

![]() $\textrm {Sym}^2 U$

also carries something close to an inner product, namely the canonical isomorphism

$\textrm {Sym}^2 U$

also carries something close to an inner product, namely the canonical isomorphism

The map

![]() $B$

is, roughly speaking, an isometry with respect to these inner products. The precise statement is that the following relation holds:

$B$

is, roughly speaking, an isometry with respect to these inner products. The precise statement is that the following relation holds:

Note that

![]() $\det B\in (\det U)^{-2}$

.

$\det B\in (\det U)^{-2}$

.

We believe that the data of

![]() $U, B$

and the relation (2.1) are a presentation of the category

$U, B$

and the relation (2.1) are a presentation of the category

![]() $S_3$

-rep. If we accept this claim, then our ansatz leads us to consider the 9-dimensional vector space

$S_3$

-rep. If we accept this claim, then our ansatz leads us to consider the 9-dimensional vector space

with its action of

![]() $G=GL(U)\cong GL_2$

, and the

$G=GL(U)\cong GL_2$

, and the

![]() $G$

-invariant subvariety

$G$

-invariant subvariety

![]() $Z\subset H$

cut out by (2.1). It is not hard to check directly that

$Z\subset H$

cut out by (2.1). It is not hard to check directly that

![]() $G$

does indeed act transitively on the open set

$G$

does indeed act transitively on the open set

![]() $Z^o$

, with stabilizer

$Z^o$

, with stabilizer

![]() $S_3$

, so the quotient is

$S_3$

, so the quotient is

But we have not attempted the stability analysis. Also note that (2.1) can be interpreted as either nine equations or six (since it is an equality of two symmetric matrices) but either way the equations are not independent, since

![]() $\dim Z=4$

.

$\dim Z=4$

.

If one wanted to pursue this example further it would be interesting to set

![]() $V=U\oplus U$

since the quotient

$V=U\oplus U$

since the quotient

![]() $V/S_3$

is very close to being the third symmetric product of

$V/S_3$

is very close to being the third symmetric product of

![]() $\mathbb{C}^2$

. Indeed as

$\mathbb{C}^2$

. Indeed as

![]() $S_3$

representations we have

$S_3$

representations we have

where

![]() $S_3$

acts by the obvious permutations on the left-hand side, and trivially on the second factor of the right-hand side. Thus one might hope to realise the birational transformation

$S_3$

acts by the obvious permutations on the left-hand side, and trivially on the second factor of the right-hand side. Thus one might hope to realise the birational transformation

via VGIT.

3. The construction

In this section we apply the heuristics of Section 2 to the quaternion group

![]() $Q$

and the corresponding

$Q$

and the corresponding

![]() $D_4$

Kleinian singularity

$D_4$

Kleinian singularity

![]() $V/Q$

.

$V/Q$

.

First we note that

![]() $Q$

has four non-trivial irreps of dimensions 1,1,1 and 2. So we take four vector spaces

$Q$

has four non-trivial irreps of dimensions 1,1,1 and 2. So we take four vector spaces

![]() $L_1, L_2, L_3$

and

$L_1, L_2, L_3$

and

![]() $V$

, where

$V$

, where

![]() $\dim L_i=1$

for each

$\dim L_i=1$

for each

![]() $i$

and

$i$

and

![]() $\dim V=2$

. Then, guided by isomorphisms that hold in the representation ring, we form the vector space

$\dim V=2$

. Then, guided by isomorphisms that hold in the representation ring, we form the vector space

where

\begin{align*} &\alpha _i \in \textrm {Hom}(L_i^{2},\, \det V), \\ &\beta \in \textrm {Hom}\big ((\det V)^2,\, L_1 L_2 L_3 \big ),\\ &B \in \textrm {Hom}\big ( \textrm {Sym}^2 V, \; \bigoplus _i L_i \big ) .\end{align*}

\begin{align*} &\alpha _i \in \textrm {Hom}(L_i^{2},\, \det V), \\ &\beta \in \textrm {Hom}\big ((\det V)^2,\, L_1 L_2 L_3 \big ),\\ &B \in \textrm {Hom}\big ( \textrm {Sym}^2 V, \; \bigoplus _i L_i \big ) .\end{align*}

Note that

![]() $\dim H=1+1+1+1+9=13$

and it carries a natural action of the group

$\dim H=1+1+1+1+9=13$

and it carries a natural action of the group

Remark 3.1. Perhaps a more natural construction would include a 1-dimensional vector space

![]() $L_0$

corresponding to the trivial representation. This would introduce a factor

$L_0$

corresponding to the trivial representation. This would introduce a factor

![]() $\textrm {GL}(L_0)$

to

$\textrm {GL}(L_0)$

to

![]() $G$

and the usual global stabilizer

$G$

and the usual global stabilizer

![]() $\Delta \cong \mathbb{C}^*$

. We would then choose an isomorphism of

$\Delta \cong \mathbb{C}^*$

. We would then choose an isomorphism of

![]() $G/\Delta$

with a subgroup of

$G/\Delta$

with a subgroup of

![]() $G$

using a trivialising section

$G$

using a trivialising section

![]() $\mathbb{C} \cong L_0$

. We employ the same tactic when considering the moduli space of representations of the preprojective algebra later on.

$\mathbb{C} \cong L_0$

. We employ the same tactic when considering the moduli space of representations of the preprojective algebra later on.

Next we need to identify the relations that hold between these isomorphisms in the category

![]() $\textrm {Rep} Q$

, so we can specify our invariant subvariety

$\textrm {Rep} Q$

, so we can specify our invariant subvariety

![]() $Z\subset H$

. For this we need to introduce a little more notation.

$Z\subset H$

. For this we need to introduce a little more notation.

Let

![]() $J$

denote the canonical isomorphism

$J$

denote the canonical isomorphism

as in Example 2.3. We observe that the

![]() $\alpha _i$

values give us a similar structure on the space

$\alpha _i$

values give us a similar structure on the space

![]() $\bigoplus _i L_i$

, since we can assemble them into a linear map

$\bigoplus _i L_i$

, since we can assemble them into a linear map

\begin{align*}A =\left(\begin{array}{c@{\quad}c@{\quad}c} \alpha _1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \alpha _2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \alpha _3 \end{array}\right) \!:\; \bigoplus _i L_i \longrightarrow \bigoplus _i L_i^\vee \otimes \det V .\end{align*}

\begin{align*}A =\left(\begin{array}{c@{\quad}c@{\quad}c} \alpha _1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \alpha _2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \alpha _3 \end{array}\right) \!:\; \bigoplus _i L_i \longrightarrow \bigoplus _i L_i^\vee \otimes \det V .\end{align*}

The equations we want to write are, approximately, the statement that

![]() $B$

is an isometry with respect to these two inner products. In fact in the open set

$B$

is an isometry with respect to these two inner products. In fact in the open set

that is exactly the condition we want. But to extend over the whole of

![]() $H$

we need the following three equations, which are the key ingredients in our construction

$H$

we need the following three equations, which are the key ingredients in our construction

In the second equation

![]() $I$

denotes the identity map on

$I$

denotes the identity map on

![]() $\oplus _i L_i$

. Implicit in third equation is the canonical isomorphism between

$\oplus _i L_i$

. Implicit in third equation is the canonical isomorphism between

![]() ${\wedge }^2 (\textrm {Sym}^2 V)$

and

${\wedge }^2 (\textrm {Sym}^2 V)$

and

![]() $\textrm {Sym}^2 V^\vee \otimes (\det V)^3$

, which means we can read

$\textrm {Sym}^2 V^\vee \otimes (\det V)^3$

, which means we can read

![]() ${\wedge }^2 B$

as a map

${\wedge }^2 B$

as a map

Remark 3.3. We can write our equations more concisely by denoting

so (E1), (E2), (E3) become simply

Remark 3.4. The subvariety

![]() $Z$

is unfortunately quite far from being a complete intersection. Indeed, in the open set

$Z$

is unfortunately quite far from being a complete intersection. Indeed, in the open set

![]() $H^o$

(3.1) taking the determinant of (E3) shows that

$H^o$

(3.1) taking the determinant of (E3) shows that

But if

![]() $B$

is invertible then

$B$

is invertible then

automatically, so (E1) and (E2) follow immediately from (E3).

However, outside

![]() $H^o$

the first two equations are independent of the third, and our construction really does require all of them. See Remark 3.15 for a full justification of this claim.

$H^o$

the first two equations are independent of the third, and our construction really does require all of them. See Remark 3.15 for a full justification of this claim.

Our VGIT construction is the affine variety

![]() $Z\times V$

, with the action of the group

$Z\times V$

, with the action of the group

![]() $G$

. Note that a character of

$G$

. Note that a character of

![]() $G$

must be of the form

$G$

must be of the form

![]() $L_1^{\theta _1}L_2^{\theta _2}L_3^{\theta _3}(\det V)^{\theta _4}$

so is specified by four integers. The main result of this paper is as follows.

$L_1^{\theta _1}L_2^{\theta _2}L_3^{\theta _3}(\det V)^{\theta _4}$

so is specified by four integers. The main result of this paper is as follows.

Theorem 3.5.

Let

![]() $\vartheta$

be the character

$\vartheta$

be the character

![]() $(1,1,1,1)$

.

$(1,1,1,1)$

.

-

(i) The GIT quotient

$(Z\times V) {/\!/}_{-\vartheta }\, G$

is the orbifold

$(Z\times V) {/\!/}_{-\vartheta }\, G$

is the orbifold

$[V/ Q]$

.

$[V/ Q]$

. -

(ii) The GIT quotient

$(Z\times V) {/\!/}_\vartheta \, G$

is the minimal resolution of

$(Z\times V) {/\!/}_\vartheta \, G$

is the minimal resolution of

$V/ Q$

.

$V/ Q$

.

We split the proof of this theorem into the following five lemmas.

Let

![]() $Z^o\subset Z$

be the intersection of

$Z^o\subset Z$

be the intersection of

![]() $Z$

with

$Z$

with

![]() $H^o$

. This is the locus in

$H^o$

. This is the locus in

![]() $Z$

where

$Z$

where

![]() $B$

is invertible or equivalently where

$B$

is invertible or equivalently where

![]() $\alpha _1\alpha _2\alpha _3\beta \neq 0$

.

$\alpha _1\alpha _2\alpha _3\beta \neq 0$

.

Lemma 3.6.

The stack

![]() $[Z^o/G]$

is equivalent to

$[Z^o/G]$

is equivalent to

![]() $BQ$

.

$BQ$

.

Of course this is exactly what our Tannakian approach was supposed to achieve, but we need to check it since we have not proven (and will not prove) that our chosen data really do give a presentation of

![]() $\textrm {Rep}(Q)$

.

$\textrm {Rep}(Q)$

.

Proof. The subgroup

![]() $GL_2\subset G$

acts on

$GL_2\subset G$

acts on

![]() $Z^o$

via the usual homomorphism

$Z^o$

via the usual homomorphism

![]() $GL_2 \to SO_3\rtimes \mathbb{C}^*$

. Since this is a surjection it is clear that the action of

$GL_2 \to SO_3\rtimes \mathbb{C}^*$

. Since this is a surjection it is clear that the action of

![]() $G$

is transitive (note that in

$G$

is transitive (note that in

![]() $Z^o$

the value of

$Z^o$

the value of

![]() $\beta$

is determined from the other variables by E3).

$\beta$

is determined from the other variables by E3).

Let us examine the isotropy in the quotient group

The subgroup fixing the values of

![]() $(\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3, B)$

is the group

$(\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3, B)$

is the group

![]() $(\mathbb{Z}_2)^3$

, embedded diagonally in

$(\mathbb{Z}_2)^3$

, embedded diagonally in

![]() $(\mathbb{C}^*)^3\times O_3$

, and to also fix

$(\mathbb{C}^*)^3\times O_3$

, and to also fix

![]() $\beta$

we must lie in the index-two subgroup

$\beta$

we must lie in the index-two subgroup

![]() $(\mathbb{Z}_2)^2\subset SO_3$

. Hence, the isotropy group in

$(\mathbb{Z}_2)^2\subset SO_3$

. Hence, the isotropy group in

![]() $G$

is the double cover of this in

$G$

is the double cover of this in

![]() $GL_2$

, which is

$GL_2$

, which is

![]() $Q$

.

$Q$

.

Lemma 3.7.

The

![]() $(-\vartheta )$

-stable locus in

$(-\vartheta )$

-stable locus in

![]() $Z\times V$

is

$Z\times V$

is

![]() $Z^o\times V$

and there are no strictly semistable points.

$Z^o\times V$

and there are no strictly semistable points.

Proof. A point with

![]() $\alpha _i=0$

is destabilized by the action of the 1-parameter subgroup

$\alpha _i=0$

is destabilized by the action of the 1-parameter subgroup

![]() $GL(L_i)$

. Now suppose that all the

$GL(L_i)$

. Now suppose that all the

![]() $\alpha _i$

values are non-zero but

$\alpha _i$

values are non-zero but

![]() $\beta=0$

. Then (E2) implies that the image of

$\beta=0$

. Then (E2) implies that the image of

![]() $B^\vee$

is an isotropic line in

$B^\vee$

is an isotropic line in

![]() $\textrm {Sym}^2 V^\vee$

, i.e. it lies in a line spanned by some degenerate quadratic form. It follows that we can find a 1-parameter subgroup of

$\textrm {Sym}^2 V^\vee$

, i.e. it lies in a line spanned by some degenerate quadratic form. It follows that we can find a 1-parameter subgroup of

![]() $GL(V)$

which fixes

$GL(V)$

which fixes

![]() $B$

and destabilizes the point.Footnote

1

So all points outside

$B$

and destabilizes the point.Footnote

1

So all points outside

![]() $Z^o\times V$

are unstable.

$Z^o\times V$

are unstable.

The function

is

![]() $(-\vartheta )$

-semi-invariant and does not vanish in

$(-\vartheta )$

-semi-invariant and does not vanish in

![]() $Z^o\times V$

, so all these points are semistable. And by Lemma 3.6 all these points have finite isotropy groups so there cannot be any strictly semistable points.

$Z^o\times V$

, so all these points are semistable. And by Lemma 3.6 all these points have finite isotropy groups so there cannot be any strictly semistable points.

This completes the proof of Theorem 3.5 (i). Now we turn our attention to the opposite stability condition

![]() $\vartheta$

.

$\vartheta$

.

To prove part (ii) of the theorem we will utilize the standard construction of the minimal resolution as a moduli space of representations of a preprojective algebra, so we take a moment to review the relevant details of that construction (see e.g. [Reference GinzburgGin12] for more background).

The preprojective algebra is the basic algebra which is Morita equivalent to the skew-group ring

![]() $\textrm {Sym}^\bullet V^\vee \rtimes Q$

, so its representations are equivalent to sheaves on the orbifold

$\textrm {Sym}^\bullet V^\vee \rtimes Q$

, so its representations are equivalent to sheaves on the orbifold

![]() $[V/Q]$

. We consider representations of the following form.

$[V/Q]$

. We consider representations of the following form.

Here,

![]() $V, L_1, L_2, L_3$

are the same vector spaces of dimensions 2,1,1,1 which we’ve used above, and each

$V, L_1, L_2, L_3$

are the same vector spaces of dimensions 2,1,1,1 which we’ve used above, and each

![]() $D_i, E_i$

is a linear map. The relations in the algebra are that

$D_i, E_i$

is a linear map. The relations in the algebra are that

![]() $D_iE_i=0$

for each

$D_iE_i=0$

for each

![]() $i$

, and

$i$

, and

\begin{align*}\sum _{i=1}^3 E_iD_i - E_0D_0=0\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum _{i=1}^3 E_iD_i - E_0D_0=0\end{align*}

(the minus sign is an optional convention that is convenient for us). We will use

![]() $\mathcal{S}$

to denote the affine space of representations of (3.2) and

$\mathcal{S}$

to denote the affine space of representations of (3.2) and

![]() $\mathcal{R}$

to denote the subvariety of

$\mathcal{R}$

to denote the subvariety of

![]() $\mathcal{R}$

satisfying the preprojective relations. To consider isomorphism classes of representations of the preprojective algebra we act by change of basis using the group

$\mathcal{R}$

satisfying the preprojective relations. To consider isomorphism classes of representations of the preprojective algebra we act by change of basis using the group

![]() $G$

. The parameter

$G$

. The parameter

![]() $\vartheta$

then gives a stability condition on

$\vartheta$

then gives a stability condition on

![]() $\mathcal{S}$

. An elegant observation of King (explicitly stated in [Reference CrawCra01, Proposition 5.9]) is that a representation is stable for this character iff it is generated from vertex 0 (the vertex decorated with

$\mathcal{S}$

. An elegant observation of King (explicitly stated in [Reference CrawCra01, Proposition 5.9]) is that a representation is stable for this character iff it is generated from vertex 0 (the vertex decorated with

![]() $\mathbb{C}$

), which means the following two conditions hold:

$\mathbb{C}$

), which means the following two conditions hold:

-

•

$D_i\neq 0$

for each

$D_i\neq 0$

for each

$i=1,2,3$

;

$i=1,2,3$

; -

• for some

$i\in \{1,2,3\}$

,

$i\in \{1,2,3\}$

,

$V$

is spanned by

$V$

is spanned by

$E_0$

and the image of

$E_0$

and the image of

$E_i$

.

$E_i$

.

There are no strictly semistable representations.

The moduli space of stable representations

![]() ${\mathcal{R}}^\vartheta / G$

is isomorphic to the minimal resolution

${\mathcal{R}}^\vartheta / G$

is isomorphic to the minimal resolution

![]() $X$

of

$X$

of

![]() $V/Q$

[Reference KronheimerKro86]. Our claim is that the variety

$V/Q$

[Reference KronheimerKro86]. Our claim is that the variety

![]() $Z$

contains enough information about the representation theory of

$Z$

contains enough information about the representation theory of

![]() $Q$

to capture

$Q$

to capture

![]() ${\mathcal{R}}^\vartheta / G$

and in turn

${\mathcal{R}}^\vartheta / G$

and in turn

![]() $X$

.

$X$

.

First we need a little more notation. For each

![]() $i$

we have a component

$i$

we have a component

of

![]() $B$

. We denote

$B$

. We denote

and recall that

![]() $\omega$

denotes the two-form:

$\omega$

denotes the two-form:

Then for each point

![]() $(\alpha _1,\alpha _2,\alpha _3,\beta , B,x)\in H\times V$

we associate a representation of the quiver (3.2) by setting

$(\alpha _1,\alpha _2,\alpha _3,\beta , B,x)\in H\times V$

we associate a representation of the quiver (3.2) by setting

\begin{align*} E_0 =x :& \;\;\mathbb{C} \to V,\\ D_0 = \omega (x, -) :&\;\; V \to \mathbb{C},\\ D_i = B_i^x :& \; \;V \to L_i, \\ E_i = \alpha _i (B_i^x)^\vee :& \;\; L_i \to V .\end{align*}

\begin{align*} E_0 =x :& \;\;\mathbb{C} \to V,\\ D_0 = \omega (x, -) :&\;\; V \to \mathbb{C},\\ D_i = B_i^x :& \; \;V \to L_i, \\ E_i = \alpha _i (B_i^x)^\vee :& \;\; L_i \to V .\end{align*}

Thus we have a

![]() $G$

-equivariant map

$G$

-equivariant map

![]() $g \colon H\times V \longrightarrow {\mathcal{S}}$

.

$g \colon H\times V \longrightarrow {\mathcal{S}}$

.

Lemma 3.9.

If

![]() $(\alpha _1,\alpha _2,\alpha _3,\beta , B,x)$

lies in

$(\alpha _1,\alpha _2,\alpha _3,\beta , B,x)$

lies in

![]() $Z\times V$

then the associated representation satisfies the preprojective algebra relations. That is,

$Z\times V$

then the associated representation satisfies the preprojective algebra relations. That is,

![]() $g$

restricts to

$g$

restricts to

![]() $G$

-equivariant morphism

$G$

-equivariant morphism

![]() $f \colon Z \times V \longrightarrow {\mathcal{R}}$

.

$f \colon Z \times V \longrightarrow {\mathcal{R}}$

.

Proof. At the four external vertices the relation is essentially automatic; if

![]() $L$

is a 1-dimensional vector space and

$L$

is a 1-dimensional vector space and

![]() $E: L \to V$

is any linear map then the composition

$E: L \to V$

is any linear map then the composition

is zero. At the central vertex the required relation is

By construction this is a trace-free endomorphism of

![]() $V$

, and the space of such endomorphisms can be canonically identified with

$V$

, and the space of such endomorphisms can be canonically identified with

![]() $\textrm {Sym}^2 V\otimes (\det V)^{-1}$

. The relation is (E1) evaluated at the point

$\textrm {Sym}^2 V\otimes (\det V)^{-1}$

. The relation is (E1) evaluated at the point

![]() $x^2\in \textrm {Sym}^2 V$

.

$x^2\in \textrm {Sym}^2 V$

.

Since

![]() $f$

is

$f$

is

![]() $G$

-equivariant if descends a rational map

$G$

-equivariant if descends a rational map

Remark 3.10. Not every preprojective representation is the image of a point on

![]() $Z \times V$

. For example, a representation where

$Z \times V$

. For example, a representation where

![]() $E_0=0$

and any other

$E_0=0$

and any other

![]() $E_i \neq 0$

cannotbe in the image of

$E_i \neq 0$

cannotbe in the image of

![]() $f$

.

$f$

.

Lemma 3.11. Given a point

the following are equivalent.

-

(i) The point

$(z,x)$

is

$(z,x)$

is

$\vartheta$

-semistable.

$\vartheta$

-semistable.

-

(ii) The associated representation

$f(z,x)$

is

$f(z,x)$

is

$\vartheta$

-stable.

$\vartheta$

-stable.

-

(iii) We have

$B_i^x\neq 0$

for each

$B_i^x\neq 0$

for each

$i$

, and for some

$i$

, and for some

$i$

the space

$i$

the space

$V$

is spanned by

$V$

is spanned by

$x$

and the image of

$x$

and the image of

$\alpha _i (B_i^x)^\vee$

.

$\alpha _i (B_i^x)^\vee$

.

Proof. That (iii)

![]() $\Rightarrow$

(ii) is immediate from our discussion of

$\Rightarrow$

(ii) is immediate from our discussion of

![]() $\vartheta$

-stability above. To see that (ii)

$\vartheta$

-stability above. To see that (ii)

![]() $\Rightarrow$

(i) we just note that if a representation is stable then there is a

$\Rightarrow$

(i) we just note that if a representation is stable then there is a

![]() $\vartheta$

-semi-invariant function on the moduli stack which does not vanish at this point. Pulling this function back shows that

$\vartheta$

-semi-invariant function on the moduli stack which does not vanish at this point. Pulling this function back shows that

![]() $(z,x)$

is

$(z,x)$

is

![]() $\vartheta$

-semistable.

$\vartheta$

-semistable.

It remains to prove that if

![]() $(z,x)$

does not satisfy the condition (iii) then it is unstable. We prove this by some slightly tedious analysis of the action of 1-parameter subgroups in

$(z,x)$

does not satisfy the condition (iii) then it is unstable. We prove this by some slightly tedious analysis of the action of 1-parameter subgroups in

![]() $G$

.

$G$

.

First note that the 1-parameter subgroup

destabilizes points with

![]() $x=0$

, so we can assume

$x=0$

, so we can assume

![]() $x\neq 0$

, and then extend it arbitrarily to a basis

$x\neq 0$

, and then extend it arbitrarily to a basis

![]() $x,y\in V$

. This basis induces co-ordinates on each space

$x,y\in V$

. This basis induces co-ordinates on each space

![]() $\textrm {Sym}^2 V^\vee \otimes L_i$

, i.e. it splits each quadratic form

$\textrm {Sym}^2 V^\vee \otimes L_i$

, i.e. it splits each quadratic form

![]() $B_i$

into

$B_i$

into

For brevity we write

![]() $\lambda _i = GL(L_i)$

and we let

$\lambda _i = GL(L_i)$

and we let

![]() $\mu \subset G$

be the 1-parameter subgroup defined by

$\mu \subset G$

be the 1-parameter subgroup defined by

These four 1-parameter subgroups all pair positively with

![]() $\vartheta$

, and generate a torus which acts on

$\vartheta$

, and generate a torus which acts on

![]() $H\times V$

but fixes

$H\times V$

but fixes

![]() $x\in V$

. To show that

$x\in V$

. To show that

![]() $(z,x)$

is

$(z,x)$

is

![]() $\vartheta$

-unstable it is sufficient to show that

$\vartheta$

-unstable it is sufficient to show that

![]() $z$

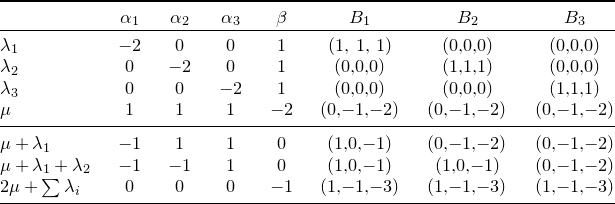

is destabilized by some 1-parameter subgroup in this torus. For convenience we present the weights of this torus action in Table 1 together with the weights of some particular 1-parameter subgroups. Note that the three columns of entries under each

$z$

is destabilized by some 1-parameter subgroup in this torus. For convenience we present the weights of this torus action in Table 1 together with the weights of some particular 1-parameter subgroups. Note that the three columns of entries under each

![]() $B_i$

are the weights of

$B_i$

are the weights of

![]() $(p_i, q_i, r_i)$

, respectively.

$(p_i, q_i, r_i)$

, respectively.

Table 1. Weights of torus action on

![]() $H$

.

$H$

.

A point is destabilized by one of these 1-parameter subgroups if all co-ordinates carrying positive weights are zero. By inspection, the following subsets are unstable:

\begin{align*} &\{\beta=0, \; B_i=0\} \quad \mbox{for any }i ,\\[4pt] &\{\alpha _1=0, \; \alpha _2=0, \; \alpha _3=0\},\\[4pt] &\{\alpha _2=0,\;\alpha _3=0,\; p_1=0\} \quad {\textit {(and permutations thereof)}} ,\\[4pt] &\{\alpha _3=0,\;p_1=0,\; p_2=0\} \quad {\textit {(and permutations thereof)}}, \\[4pt] &\{p_1=0,\; p_2=0,\; p_3=0\}. \end{align*}

\begin{align*} &\{\beta=0, \; B_i=0\} \quad \mbox{for any }i ,\\[4pt] &\{\alpha _1=0, \; \alpha _2=0, \; \alpha _3=0\},\\[4pt] &\{\alpha _2=0,\;\alpha _3=0,\; p_1=0\} \quad {\textit {(and permutations thereof)}} ,\\[4pt] &\{\alpha _3=0,\;p_1=0,\; p_2=0\} \quad {\textit {(and permutations thereof)}}, \\[4pt] &\{p_1=0,\; p_2=0,\; p_3=0\}. \end{align*}

Now suppose that for each

![]() $i$

, the image of

$i$

, the image of

![]() $\alpha _i(B_i^x)^\vee$

lies in the span of

$\alpha _i(B_i^x)^\vee$

lies in the span of

![]() $x$

. This is equivalent to

$x$

. This is equivalent to

![]() $\alpha _ip_i=0$

for each

$\alpha _ip_i=0$

for each

![]() $i$

. It follows that

$i$

. It follows that

![]() $(z,x)$

lies in one of the unstable subsets in the list above.

$(z,x)$

lies in one of the unstable subsets in the list above.

It remains to show that if

![]() $B_i^x=0$

for any

$B_i^x=0$

for any

![]() $i$

then

$i$

then

![]() $(z,x)$

is unstable, and for concreteness let us suppose

$(z,x)$

is unstable, and for concreteness let us suppose

![]() $B_1^x=0$

, i.e. that

$B_1^x=0$

, i.e. that

![]() $p_1=q_1=0$

. We consider two cases.

$p_1=q_1=0$

. We consider two cases.

Firstly suppose that

![]() $B_1=0$

, i.e. that

$B_1=0$

, i.e. that

![]() $r_1=0$

too. Then (E3) implies that

$r_1=0$

too. Then (E3) implies that

so in particular

from which it follows again that

![]() $(z,x)$

lies in one of the unstable subsets listed above.

$(z,x)$

lies in one of the unstable subsets listed above.

Secondly, suppose that

![]() $B_1\neq 0$

, i.e. that

$B_1\neq 0$

, i.e. that

![]() $r_1\neq 0$

. Then since (E2) implies that

$r_1\neq 0$

. Then since (E2) implies that

we must have

It follows again that

![]() $(z,x)$

must lie in one of the unstable subsets listed above.

$(z,x)$

must lie in one of the unstable subsets listed above.

Lemma 3.12.

There are no strictly

![]() $\vartheta$

-semistable points in

$\vartheta$

-semistable points in

![]() $Z\times V$

, and the GIT quotient

$Z\times V$

, and the GIT quotient

![]() $(Z\times V){/\!/}_\vartheta G$

is isomorphic to the moduli space of

$(Z\times V){/\!/}_\vartheta G$

is isomorphic to the moduli space of

![]() $\vartheta$

-stable representations of the preprojective algebra as in (

3.2

).

$\vartheta$

-stable representations of the preprojective algebra as in (

3.2

).

Proof. From our previous lemmas we know that the restriction of

![]() $f$

to the semistable locus in

$f$

to the semistable locus in

![]() $Z\times V$

lands in the space of stable representations of the preprojective algebra. We also know (Lemma 3.11(iii)) that the semistable locus has a Zariski-open cover

$Z\times V$

lands in the space of stable representations of the preprojective algebra. We also know (Lemma 3.11(iii)) that the semistable locus has a Zariski-open cover

![]() ${\mathcal{A}}_1\cup \, {\mathcal{A}}_2\cup {\mathcal{A}}_3$

, mapping to a corresponding open cover

${\mathcal{A}}_1\cup \, {\mathcal{A}}_2\cup {\mathcal{A}}_3$

, mapping to a corresponding open cover

![]() ${\mathcal{B}}_1\cup {\mathcal{B}}_2\cup {\mathcal{B}}_3$

of the target. We will show by direct inspection that each map

${\mathcal{B}}_1\cup {\mathcal{B}}_2\cup {\mathcal{B}}_3$

of the target. We will show by direct inspection that each map

![]() $f|_{{\mathcal{A}}_i} \colon {\mathcal{A}}_i\to {\mathcal{B}}_i$

is an isomorphism. This proves the lemma, in particular there cannot be any strictly

$f|_{{\mathcal{A}}_i} \colon {\mathcal{A}}_i\to {\mathcal{B}}_i$

is an isomorphism. This proves the lemma, in particular there cannot be any strictly

![]() $\vartheta$

-semistable points since there are no strictly semistable representations and the morphism is an injection.

$\vartheta$

-semistable points since there are no strictly semistable representations and the morphism is an injection.

For concreteness we show that

![]() $f|_{{\mathcal{A}}_1} \colon {\mathcal{A}}_1\to {\mathcal{B}}_1$

is an isomorphism. In the locus

$f|_{{\mathcal{A}}_1} \colon {\mathcal{A}}_1\to {\mathcal{B}}_1$

is an isomorphism. In the locus

![]() ${\mathcal{A}}_1$

we have

${\mathcal{A}}_1$

we have

![]() $\alpha _1\neq 0$

and we know that

$\alpha _1\neq 0$

and we know that

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $(\alpha _1(B_1^x)^\vee \circ B_1)(x^2)$

from a basis for

$(\alpha _1(B_1^x)^\vee \circ B_1)(x^2)$

from a basis for

![]() $V$

at all points. So if we identify

$V$

at all points. So if we identify

![]() $V$

with

$V$

with

![]() $\mathbb{C}^2$

, and

$\mathbb{C}^2$

, and

![]() $L_1$

with

$L_1$

with

![]() $\mathbb{C}$

, then up to a unique element of

$\mathbb{C}$

, then up to a unique element of

![]() $GL(L_1)\times GL(V)$

we can set

$GL(L_1)\times GL(V)$

we can set

for some

![]() $r_1\in \mathbb{C}$

. So

$r_1\in \mathbb{C}$

. So

![]() $B_1(x^2)=1$

and

$B_1(x^2)=1$

and

![]() $\alpha _1(B_1^x)^\vee (1)=(0,1)$

. If we also pick basis vectors for

$\alpha _1(B_1^x)^\vee (1)=(0,1)$

. If we also pick basis vectors for

![]() $L_2$

and

$L_2$

and

![]() $L_3$

then our remaining variables are

$L_3$

then our remaining variables are

and the only group acting is the torus

![]() $GL(L_2)\times GL(L_3) \cong (\mathbb{C}^*)^2$

. Semistability is the condition that

$GL(L_2)\times GL(L_3) \cong (\mathbb{C}^*)^2$

. Semistability is the condition that

![]() $(p_2, q_2)\neq (0,0)$

and

$(p_2, q_2)\neq (0,0)$

and

![]() $(p_3, q_3)\neq (0,0)$

.

$(p_3, q_3)\neq (0,0)$

.

By (E2) we have

\begin{align*} B_1J^{-1}B_1 &=2r_1 = \beta^2\alpha _2\alpha _3 = \omega ,\\ B_1J^{-1}B_2 &=r_2+r_1p_2=0,\\ B_1J^{-1}B_2 &=r_3+r_1p_3=0, \end{align*}

\begin{align*} B_1J^{-1}B_1 &=2r_1 = \beta^2\alpha _2\alpha _3 = \omega ,\\ B_1J^{-1}B_2 &=r_2+r_1p_2=0,\\ B_1J^{-1}B_2 &=r_3+r_1p_3=0, \end{align*}

so all the

![]() $r_i$

variables are redundant. And by (E3) we have

$r_i$

variables are redundant. And by (E3) we have

hence

Finally by Equation (E1) we have

One can verify that these Equations (3.3) and (3.4), together with the equations for the

![]() $r_i$

’s above, imply all the remaining components of (E1), (E2) and (E3).

$r_i$

’s above, imply all the remaining components of (E1), (E2) and (E3).

Now consider our open set

![]() ${\mathcal{A}}_1$

in the space of stable representations. We can similarly fix

${\mathcal{A}}_1$

in the space of stable representations. We can similarly fix

leaving only

![]() $(\mathbb{C}^*)^2$

acting. We have

$(\mathbb{C}^*)^2$

acting. We have

![]() $D_i\neq 0$

for

$D_i\neq 0$

for

![]() $i=2,3$

, and we know

$i=2,3$

, and we know

![]() $D_i\circ E_i=0$

. So if we write

$D_i\circ E_i=0$

. So if we write

![]() $D_i = (\hat {p}_i, \hat {q}_i)^\top$

for

$D_i = (\hat {p}_i, \hat {q}_i)^\top$

for

![]() $i=2,3$

then we must have

$i=2,3$

then we must have

for some

![]() $\hat {\omega }, \hat {\alpha }_2, \hat {\alpha }_3$

. Moreover the relation at the central vertex implies three equations

$\hat {\omega }, \hat {\alpha }_2, \hat {\alpha }_3$

. Moreover the relation at the central vertex implies three equations

\begin{align*} \hat {\alpha }_2\hat {p}_2^2 + \hat {\alpha }_3\hat {p}_3^2+1 & = 0 ,\\ \hat {\alpha }_2\hat {p}_2\hat {q}_2 + \hat {\alpha }_3\hat {p}_3\hat {q}_3 & = 0,\\ \hat {\alpha }_2\hat {q}_2^2 + \hat {\alpha }_3\hat {q}_3^2 - \hat {\omega } &=0. \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \hat {\alpha }_2\hat {p}_2^2 + \hat {\alpha }_3\hat {p}_3^2+1 & = 0 ,\\ \hat {\alpha }_2\hat {p}_2\hat {q}_2 + \hat {\alpha }_3\hat {p}_3\hat {q}_3 & = 0,\\ \hat {\alpha }_2\hat {q}_2^2 + \hat {\alpha }_3\hat {q}_3^2 - \hat {\omega } &=0. \end{align*}

The first implies that

![]() $(\hat {\alpha }_2\hat {p}_2, \hat {\alpha }_3\hat {p}_3)\neq (0,0)$

, then the second implies that

$(\hat {\alpha }_2\hat {p}_2, \hat {\alpha }_3\hat {p}_3)\neq (0,0)$

, then the second implies that

for some

![]() $\hat {\beta }$

, and then the third becomes equivalent to

$\hat {\beta }$

, and then the third becomes equivalent to

![]() $\hat {\omega } = \hat {\beta }^2\hat {\alpha }_2\hat {\alpha }_3$

. Comparing with (3.3), (3.4) above it is evident that

$\hat {\omega } = \hat {\beta }^2\hat {\alpha }_2\hat {\alpha }_3$

. Comparing with (3.3), (3.4) above it is evident that

![]() ${\mathcal{B}}_1$

is isomorphic to

${\mathcal{B}}_1$

is isomorphic to

![]() ${\mathcal{A}}_1$

.

${\mathcal{A}}_1$

.

Remark 3.15. Let us conclude by justifying the necessity of all three Equations (E1), (E2) and (E3), as promised in Remark 3.4.

Firstly, Equation (E3) is clearly necessary since without it the variety

![]() $Z$

would have (at least) two irreducible components related by

$Z$

would have (at least) two irreducible components related by

![]() $\beta \mapsto -\beta$

.

$\beta \mapsto -\beta$

.

Now consider the subset

In this subset:

-

E1 says that the image of

$B$

is isotropic in

$B$

is isotropic in

$\bigoplus L_i$

;

$\bigoplus L_i$

; -

E2 says that the image of

$B^\vee$

is isotropic in

$B^\vee$

is isotropic in

$\textrm {Sym}^2 V^\vee$

;

$\textrm {Sym}^2 V^\vee$

; -

E3 says that

$B$

has rank 1.

$B$

has rank 1.

The first two are independent, but either of them implies the third.

Take a generic point

![]() $(u, v)\in H'\times V$

where (E2) holds but (E1) fails. Then the associated quiver representation will not satisfy the preprojective algebra relations, but will still be generated from vertex 0 and hence King stable. So

$(u, v)\in H'\times V$

where (E2) holds but (E1) fails. Then the associated quiver representation will not satisfy the preprojective algebra relations, but will still be generated from vertex 0 and hence King stable. So

![]() $(u,v)$

is

$(u,v)$

is

![]() $\vartheta$

-semistable. This shows that Equation (E1) is necessary for our construction.

$\vartheta$

-semistable. This shows that Equation (E1) is necessary for our construction.

Now instead take a point

![]() $(u, v)$

where (E1) holds but (E2) fails. Using the functions

$(u, v)$

where (E1) holds but (E2) fails. Using the functions

together with

![]() $\alpha _1,\alpha _2,\alpha _3$

it is easy to find a non-vanishing function which is semi-invariant for some power of

$\alpha _1,\alpha _2,\alpha _3$

it is easy to find a non-vanishing function which is semi-invariant for some power of

![]() $-\vartheta$

. So

$-\vartheta$

. So

![]() $(u,v)$

is

$(u,v)$

is

![]() $(-\vartheta )$

-semistable (strictly, since the stabilizer is infinite). Thus Lemma 3.7 would fail without Equation (E2).

$(-\vartheta )$

-semistable (strictly, since the stabilizer is infinite). Thus Lemma 3.7 would fail without Equation (E2).

Acknowledgements

The first author would like to thank Daniel Chan for enlightening discussions relating to this article. This article was initiated at the ICTP, the authors would like to thank them for the hospitable environment they provided.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Journal Information

Moduli is published as a joint venture of the Foundation Compositio Mathematica and the London Mathematical Society. As not-for-profit organisations, the Foundation and Society reinvest

![]() $100\%$

of any surplus generated from their publications back into mathematics through their charitable activities.

$100\%$

of any surplus generated from their publications back into mathematics through their charitable activities.