In January of 1838, as the Second US–Seminole War dragged on in Florida, a Seminole woman led a mixed detachment of US soldiers, sailors, and marines into a devastating ambush. The troops had emerged from the Everglades near Jupiter inlet, the Loxahatchee River’s coastal mouth on the southeastern coast of Florida, to find a “fresh trail” that led to her as she watched over a herd of livestock. She agreed to guide them to the Seminole groups camped several miles away and took them down a wide trail through the open country until they reached the edge of a cypress swamp, full of vegetation that offered ample cover and concealment for her waiting compatriots. From here, the Seminole party could attack from the relative safety of the trees, while the troops remained easy targets, unprotected in the open. Afterward, the Seminole fighters knew they could retreat into the swamp, where their enemy would be disinclined to follow. Here, at the border of field and forest, they sprang their ambush and inflicted heavy casualties. US Navy Lieutenant Levi Powell, the officer in command, reported that his losses amounted to twenty-seven, with twenty-two wounded and five killed, including most of the officers, out of the eighty or more men he brought. Yet none of these embarrassing details, least of all the woman’s successful deception, appeared in the army’s final report.Footnote 1

In fact, the official report erased her from the historical record. General Thomas Jesup, the officer in command of US troops, submitted it to the Secretary of War, Joel R. Poinsett. In his letter, Jesup observed that Powell’s detachment

landed at the head of one of the branches of Jupiter River; fell in with and attacked a body of Indians, and after a most gallant effort, was overpowered by their numbers, and compelled to retreat with the loss of several officers and men killed and wounded. He killed three Indians and a negro [a Black Seminole] and made one prisoner.

Jesup had sent Powell to lead a special joint force consisting of eighty-five sailors, two artillery companies operating as infantry, and one company of volunteer infantry. Their mission was to penetrate the Everglades and expel the Seminole people.Footnote 2 Jesup’s report cast Powell as the primary actor. It was Powell, according to Jesup, who found the Seminole warriors and initiated an attack. To conjure a battle out of an ambush, Jesup had to erase the woman.

When General Jesup wrote his report to the Secretary of War, he rewrote history – her victory became Powell’s Battle.Footnote 3 Jesup penned his account from the perspective of a general seeking to prove that his campaign was a successful one. While he may not have convinced posterity of his military brilliance, he successfully removed the woman from history and the ambush from the war. Until now, no other account of this incident in the more than 180 years has characterized what happened to Powell’s detachment on 15 January 1838 as a deliberate ambush. That is partly because it was one short moment in a long and chronically understudied war. But it is also true that military historians of the Jacksonian era have given short shrift to Indigenous women’s wartime activities and have treated reports like Jesup’s as accepted fact rather than constructed narratives framed by army culture’s assumptions and intents.

Powell’s initial report to his superior included more of the truth. While he noted the woman’s presence, he failed to consider her motives or potential to act as an enemy. To Powell, she was a “guide,” an asset. He wrote that after landing,

we found a fresh trail, which, in following, led us to a herd of cattle and horses; amongst these, we captured a squaw. The woman, on being questioned, told us of several parties of Indians camped in the neighborhood, we took her as a guide, and after a march of five miles struck a large beaten trail at the head of a cypress swamp; at the same instant we heard the war-whoop before us.

He later said, “the enemy was in greater force than we expected and outnumbered our party so much as to cover our flanks, the squaw whom we brought off says one hundred” and “the officers were all shot at the head of their divisions.”Footnote 4

The versions of the event published in early 1838, initially in the Savannah Georgian and quickly reprinted in publications like Niles National Register and the Army and Navy Chronicle, described how Powell

with about eighty men, including regulars, landed at Jupiter Inlet and took a squaw; she told them she would carry them where the Indians were encamped, which was about seven miles off. Lieutenant P. attacked them, the Indians returned the fire with a great deal of spirit, when the sailors ran, and had it not been for the artillery, they would all have been cut to pieces. All the officers were wounded.

A fellow officer noted that after the marines fled, the artillerymen covered their retreat. He concluded that the engagement “was a complete defeat” for Powell. In addition to taking heavy casualties, the troops left behind two boats, including one containing a keg of powder and a box of cartridges, giving the Seminole group valuable resources to continue the fight. Though Seminole warriors attacked in strength, struck down Powell’s detachment in droves, and nearly surrounded the US servicemen, these authors categorically insisted that the officers led a charge “across a deep swamp in a handsome manner,” and gallantly “attacked” the enemy. Their writings reveal a “production of specific narratives” that shaped the making of history, a process that at once silenced women and amplified officers’ pens.Footnote 5

Methodologically, this book delineates the hazy outlines of women like this one, whom army officers only ever hastily sketched. Doing so begins to clarify not only the historical subject but also the writers themselves, the men who wrote army history. The ways officers and enlisted men wrote about women, understood or failed to understand women’s combatancy, and described how they believed men and women should act, mattered because they gave form to army culture. In reading army records, one must find the author’s hand. Army discourse about women did more than describe women. It gave form to military men.

The officers caught in the ambush had all the pieces of the story, but none could admit that they were a woman’s enemy, or that a woman led them into harm. Authors of reports clung to the belief that she freely offered her services. They wanted to believe that Seminole women wanted to help. Historians of the war, like John Mahon, did caveat that she may not have done so willingly. He argued that she was “captured and forced to act as guide.” Still, Mahon remained blind to her potential combatancy. Men who interpreted this event came, always, to one of two conclusions. Either the US forced her to guide them, or she “offered to guide [Powell] to the place where the Indians were.”Footnote 6 But there was a third prospect: she led them into a trap. Why were neither the participants then nor the historians since able to recognize that possibility?

This project focuses on the US Army and enemy women’s interactions in the Second US–Seminole War of 1835–1842 and the US–Mexican War of 1846–1848 to explore how men’s beliefs about women in war shaped army culture. Military histories of this era and these conflicts that exclude source material about women give the impression that there exist insufficient primary sources to tell women’s stories. This is not so. Although there are significant silences in the archive – evidence of Black women’s experiences in these conflicts is exceedingly rare – and while Seminole women are certainly more challenging archival subjects than, for instance, officers’ wives, there exists a substantial body of primary sources, especially material written by soldiers (often officers though sometimes enlisted men) that addresses them.Footnote 7 This approach seeks a nuanced portrayal of army culture by beginning with the assumption that what soldiers had to say about enemy women was important – not ornamental or sentimental, but elemental. This type of scholarly attention to discourse about women, the prototypical outsiders in histories of war, can help historians consider the discursive processes at work in army documents.

Even though soldiers often erased women from official narratives, such encounters prompted them to confront their beliefs about women and war. It was easy for them to label white US women on the home front as innocent and ignorant of war. But the women of a non-white, non-US enemy people encountered during wartime forced the army to reckon with the complex and contradictory category of enemy women. To understand that population, army officers first sought formal answers in the laws of war as written by eighteenth-century jurist Emerich de Vattel, whom the army regulations crafted by General Winfield Scott closely followed.Footnote 8 When applied to militaries and warfare, Euro-American jurists labeled these doctrines not as international law but as a specific subset, the laws of war. Rather than binding laws, the term referred to an evolving set of Euro-American conventions derived from a predominantly European body of writing. As historian Deborah Rosen shows, the US emerged from the First US–Seminole War of 1816–1818 with new ideas, asserting “a selectively applicable international law” that conferred rights to white people, while limiting those of Indigenous and Black persons. This “blatant legal line-drawing based on race and culture helped solidify an exclusionary vision” in the laws of war.Footnote 9 Within this climate of changing US norms, Scott’s guidelines attempted to answer the thorny question of who could be made a prisoner of war, who was a combatant, whether (or when) an army could target civilians and civilian property, and when an army may pursue an exemption to the established laws of war.

Women’s separation from war was foundational to all of these because of the embedded assumption that even if a woman was an enemy, she remained “the essential noncombatant.”Footnote 10 Years before he wrote the massively influential Lieber’s Code during the Civil War, Francis Lieber formulated perhaps the most straightforward explanation for why women’s incapacity to make war must hold. During the Second US–Seminole War in 1838, he wrote that “the woman cannot defend the state: if she were physically able to do it, she would necessarily lose her peculiar character as woman, and thus a necessary element of civilization would be extinguished.” For Lieber, women’s innocence was a foundational aspect of society. He continued, “here, too, emergencies may make exceptions – exceptions of the noblest and proudest kind; but should they cease to form exceptions, a subversion of the whole moral order of things would be the consequence.”Footnote 11 Lieber insisted on women’s separation from war.

Much as the laws of war allowed arbiters of army culture in this era to claim that they were building their institution on the purportedly stable terrain of law, discourse about women provided “a reliable foundation of other hierarchies allegedly based on natural and bodily difference,” especially hierarchies of military masculinity. Yet, as Elena Schneider reminds us, “neither empires nor imperial subjects were stable categories.” Interactions with enemy women shaped imperialist policies crafted by US political leaders and wielded against Florida and Mexico. Such interactions also shaped a kind of internal imperialism within the army. In the Jacksonian era, army discourse about, and interactions with, enemy women molded a paternalistic hierarchy that also affirmed officers’ naturalized dominance over their soldiers. Studying the experiences of those whom the military deemed enemy women, including in the context of intimate relationships, can illuminate the “structures of domination” that produced and changed army culture.Footnote 12

Paternalism, a system where those with power claimed to control and care for those without it, came to pervade army culture partly because of its broad utility. Eugene Genovese notes that there are different variants of paternalism in different “historical settings,” each distinct even as each “defines relations of superordination and subordination,” a “prevailing ethos” that “increases as the members of the community accept – or feel compelled to accept – these relations as legitimate.” Army paternalism was not synonymous with Genovese’s Old South variant, which primarily shaped relations between enslavers and the enslaved (rather than relations between free persons of different military ranks, as in the army), but it unfolded from within the same slaveholding republic. Like Southern paternalism, army paternalism “grew out of the necessity to discipline and morally justify a system of exploitation.” While it encouraged “kindness and affection,” it also “encouraged cruelty and hatred.”Footnote 13 Moreover, most officers had some direct experience of commanding enslaved labor.

Leveraging a random sampling technique, Historian Yoav Hamdani’s analysis of military pay records shows that between 1816 and 1861, over three-quarters of officers held enslaved servants at some point in their careers. The Military Peace Establishment Act of 1802 which created the military academy at West Point and institutionalized the presence of army laundresses also allotted one additional ration to officers for “one servant, not a soldier of the line.” Then in 1816, major postwar reforms prohibited officers from using soldiers as servants, authorizing additional subsidies so that officers could hire civilian servants instead. Many officers chose to maximize their profits by hiring enslaved labor and keeping the additional funds. This bureaucratic process racialized servitude, carving out a distinct identity for soldiers as white men while also equating Black with servant, a term that became a euphemism for slavery. Within the US “slaveholding republic,” the regular army was a “slaveholding institution” that incentivized officers to participate in slavery. Also, US politicians who controlled the US Army consistently used it against Native groups. Army culture thus emerged from a uniquely Jacksonian context characterized by rapid territorial conquest, expelling Indigenous societies, and expanding slavery.Footnote 14

Within the army, although soldiering was exclusively for white men, army officers used the tools of enslavers – including physical punishment and religious instruction – to control enlisted men. Officers appealed to Christianity to pacify soldiers and naturalize submission to patriarchal officers, as children obey fathers and enslaved people obey masters. More frequently, they punished. Enslavers, often through white overseers, imposed horrific violence on enslaved people. They whipped, beat, confined, chained, tortured, and hanged. Officers sentenced soldiers to punishments including lashes, imprisonment, extended periods in stressful positions, months of hard labor with a ball and chain, branding with the letter “D” for a deserter, and hanging. They often directed sergeants to administer this violence. It is difficult to imagine these punishments imposed on another group of white men in Jacksonian America.Footnote 15

Punishment supported a hierarchical order that brought order to the complex realities of wartime Florida. Historian Stephanie McCurry notes that in the South Carolina Low Country, households were spatial and social units, “organizing the majority of the population – slaves of both sexes and all ages and free women and children – in relations of legal and customary dependency” to a male head.Footnote 16 Army officers, too, leveraged race and gender-based notions of dependency, not to define autonomous households but to assert power over their army family. An officer’s army family encompassed all those they controlled. For a captain in Florida, that meant his wife and children, his lieutenants, his soldiers, his company’s laundress, any other family members that accompanied his unit, his servants (free and enslaved), and any Indigenous guides or auxiliaries assigned to him. Each officer led his own army family as a father, and each member’s position in the family shaped their obligations.

In an addition that complemented this US context, regular officers also sometimes understood themselves as inheritors of British and Continental military traditions. General Winfield Scott, author of the army’s General Regulations and its Commanding General from 1841 to 1861, maintained deep ties across the Atlantic. He toured Europe in 1815, arriving in England soon after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo and hastening across the channel to see the great allied armies occupying France. Scott met many leading European military thinkers, and throughout this career drew on European precedents to shape the emerging US Army.Footnote 17

In his study of English paternalism in the Victorian Era’s early years, David Roberts characterizes an outlook that matched the worldview of officers like Scott. Roberts argues that “in any definition of the paternalist social outlook three aspects must be considered: paternalism’s basic assumption about the framework of society; its doctrines concerning the duties of the wealthy, privileged, and powerful; and the many and various attitudes which, while not essential to the paternalist outlook, are often associated with it.” Robert emphasizes that “at the heart of a paternalist’s hierarchical outlook is a strong sense of the value of dependency, a sense that could not exist without those who are dependent having an unquestioned respect for their betters.” Benevolence could be a prominent trapping of paternalism, but at its center stood the “obligation to rule firmly and to guide and superintend.”Footnote 18

Officers combined these elements – a preference for a rigid and almost aristocratic hierarchy of officers over enlisted men, alongside the notion that harsh paternalistic discipline was an expression of loving care. Indeed, paternalistic officers claimed an ethic of care to justify immense authority over the lives of enlisted men. Moreover, when it came to interactions with Native and Mexican women, paternalism offered a vocabulary through which all members of the army, officers or enlisted, could claim authority over local peoples. In this, paternalism offered both a measure of institutional cohesion to army culture and a way to stabilize the army’s hierarchical power structure.

Most officers considered themselves – primarily native-born, middle-class Protestants – superior to enlisted men, often foreign-born, working-class, and Catholic. Where officers believed themselves to be collectively disciplined, intelligent, and authoritative, they cast themselves in relief against the purported tendencies of soldiers toward indiscipline, vulgarity, and unbridled passions. Therefore, to ensure women’s safety and US military honor, officers leveraged discourses about protecting women to control the perceived sexual threat posed by potentially dangerous enlisted men. The army as a whole protected enemy women from non-army men, like white settlers in Florida, Native men, and Mexican men. But army officers protected enemy women from enlisted men.

The Genre of Army Writing

A feminist approach to military history considers how army leaders constructed women’s presence in, and absence from, military records in specific, deliberate ways. It does so through close readings of army documents and the excavation of source material related to discourse about women and women’s war experiences. The field of postcolonial studies closely informs this approach. Both seek to decolonize the Indigenous and Mexican women who appear in army archives and contribute to the “sustained assault on the politics of knowledge” that “orients the postcolonial field.”Footnote 19 Through the “study of imperialism and culture,” as Edward Said argues, “we can better understand the persistence and durability of saturating hegemonic systems like culture when we realize that their internal constraints upon writers and thinkers were productive, not unilaterally inhibiting.” Army officers shaped the archive by failing to see, or excluding, women’s combatancy from official documents, and by adding narratives describing the army’s protection of women. These “internal constraints” produced vital cultural elements. The field of military history has just begun to consider the Mexican War’s imperial character and generally exists apart from postcolonial approaches.Footnote 20

On balance, scholarship on the US Army in Florida and Mexico bolsters the “still resilient paradigm” that there is no American Empire. To deconstruct that paradigm, Amy Kaplan argues that one must connect culture to US imperialism.Footnote 21 Studying army culture at war in the aggressively expansionist climate of the 1830s and 1840s makes exactly that connection. Exploring the relationships between soldiers and colonized women makes it even more pointedly because US officers and enlisted men often treated women as subjects of military protection and thus sources of potential legitimacy for US occupation.

This book explores how gender shaped the army’s cultural assumptions and therefore the army’s policies and behaviors.Footnote 22 Isabel Hull’s study of the wartime Imperial German military offers a model. Drawing on insights from anthropology and social science, Hull examines German military culture using Edgar Schein’s three levels of organizational culture – visible behaviors and artifacts, professed beliefs and values, and the foundational but often unseen assumptions that motivate members to act. This study follows Hull’s conclusion that “basic assumptions tend to coalesce into a pattern. The resulting constellation of mutually supporting assumptions lends stability and consistency to the whole.”Footnote 23

Hull emphasizes the importance of studying military cultures in times of conflict. In this, she shares a concern with military historian John Keegan’s classic study, The Face of Battle. Keegan found that just as war “compromises the purity of doctrines, it damages the integrity of structures, upsets the balance of relationships, interrupts the network of communication which the institutional historian struggles to identity and, having identified, to crystallize.” War is, rather, “the institutional military historian’s irritant,” causing such scholars to hold a “preference, paradoxically, for the study of the armed forces in peacetime.”Footnote 24 It remains difficult to work out which peacetime assumptions an army adheres to in the crucible of war, and Keegan famously grappled with this question to reveal the battlefield experiences of ordinary soldiers. Even compared to the challenges of researching enlisted men, it is harder still to resurrect women’s experiences, but it is possible. And it is no less necessary.

Hull describes how German military culture incentivized sexual violence as an expression of male dominance rooted in the right of the conquerors to dominate the conquered and enhanced by the myth of hyper-sexualized women in “uncivilized” societies. Hull reminds us that military culture is a way to understand that which is “habitual and unquestioned,” the norms and instincts that shape actions in war. In regulations and practice, norms operated on hidden assumptions, creating “systematic but unintentional results.” In the case of the US Army, one such hidden assumption was an internal logic that they protected helpless women.Footnote 25

It was a claim well fitted to the needs of army leaders who sought to accomplish their assigned expansionist missions. Shelley Streeby’s work on “the production of popular culture” encapsulates an approach applied here to the production of army culture, whose development is easily oversimplified to a professionalizing officer corps. She argues, “an understanding of the U.S.–Mexican War (1846–1848) and mid-nineteenth-century empire building is required in order to understand the histories of race, nativism, labor, politics, and popular and mass culture in the United States.” To go further, where the US war on Mexico “crucially shaped US politics and culture,” mass cultures also shaped the US Army. Streeby contends that mass culture was “inextricable from scenes of empire-building” in Mexico and elsewhere. Her book, in turn, draws on classic works like Robert Johannsen’s To the Halls of Montezuma. Both emphasize cultural experiences of the US–Mexican War, and this project builds on theirs.Footnote 26 It demonstrates how the war shaped US and army culture in a formative era, and argues that historians must understand army culture in Mexico in the context of wartime experience gained in Florida.

Earlier studies of army culture often focus on the army while in garrison – yet, as John Keegan would remind us, one cannot understand the development of a military culture without studying war. Edward Coffman’s social history of the nineteenth-century army during peacetime emphasizes how officers’ wives, romantic partners, and children experienced life in the frontier army. He situates the army as a part of US society. Coffman’s regulars, with their social worlds full of officers, enlisted men, women, and children remains a model of scholarship, as does his call for further scholarship on the topic of army women and children, and his valuable insight into army wives’ peacetime lives. There is much room to build on his work. The Old Army offers “a portrait of the American Army in peacetime,” while interactions between regulars and women in times of war exist beyond its scope.Footnote 27

The field of postcolonial studies offers a way to extend such a study past the army’s peacetime domestic space. The army participated in “the domesticating strategies of empire,” and interactions between soldiers and enemy women shaped the contours of imperial domestication.Footnote 28 Taming Florida and later Mexico meant gaining local women’s support and willing submission. Yet, when officers enforced norms regarding how enlisted men were to treat local women, they not only domesticated local populations to US rule – they also domesticated soldiers to officers’ authority.

Like the nation, the regular army underwent a significant transformation in the years leading up to 1848. Thus, scholars of imperialism such as Shelley Streeby, Amy Greenberg, and Paul Foos have located the US–Mexican War as a formative moment where the US became an empire.Footnote 29 In Cultures of United States Imperialism, Amy Kaplan argues that the US nation and empire-building were “historically coterminous and mutually defining.” She relates “internal categories of gender, race, and ethnicity to the global dynamics of empire-building” and, in doing so, challenges the opposition between men who perform public actions internationally and women whose experiences remain bounded by the domestic nation and private activities. Studying the unique subculture of the US state’s most-used instrument of empire-building produces an improved understanding of the mutually constitutive and understudied relationships between empire, gender, and culture.Footnote 30

Accounts of the antebellum army of “the kind with the women still in it” enrich our historical understanding.Footnote 31 Indeed, US military policy changed when Seminole women’s resistance to forced removal met a US strategy increasingly premised on their capture. When Mexican women sold goods and services to the US, it produced an archetypal view in US minds of such women as affectionate allies. Those views matched stronger but narrower noncombatant protections in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Scholars have not recognized these effects of women’s wartime activities on military and national policy. Ann Stoler writes in Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power that much of the work “on gender and empire has tacked tentatively between a feminist concern that focuses on women, their daring and despair, and one that focuses on how a wider domain was shaped by gendered sensibilities and sexual politics.” While the “first tends to stop at the threshold of women’s direct agency and direct presence; the latter does not.” Although “tacking back and forth is not a problem in itself,” Stoler believes that “a broader gendered history may offer more than women’s history tout court.” In US military history, even traditional women’s history remains underdeveloped. John Belohlavek’s Patriots, Prostitutes, and Spies is the sole monograph by a US military historian about women and the War on Mexico.Footnote 32 He writes of women from different nationalities and backgrounds but narrates women’s experiences without connecting them to military policy, imperialism, or army culture. Of the broader gendered approach that Stoler describes, there is still less. Amy Greenberg’s Manifest Manhood and the Antebellum Empire and Laurel Clark Shire’s Threshold of Manifest Destiny are exceptions, although neither focuses on the regular army, as is Peter Guardino’s The Dead March, which draws on gender, race, and religion to tell the history of war between the US and Mexico.Footnote 33

In this underdeveloped field, Stephanie McCurry’s question remains emphatically relevant: “Why, given all the potent evidence of their significance, have women been rendered invisible in histories of war?” McCurry locates a process of erasure following the Civil War in a postwar need to return to the comforting fiction of women’s innocence. She notes that after the war, “on matters of gender, Thermidor set in.”Footnote 34 This study of army culture in Florida and Mexico demonstrates how that erasure can happen not just after war, but during it. As when General Jesup turned an ambush into a battle, from the first moment army officers touched pen to paper to make a report they transformed the present into recorded history. In doing so, they often eliminated records of women’s participation. Instead of recording women’s wartime activities, report writers preserved a sentimental army fiction of female harmlessness and submission. It was Thermidor in Brumaire.

A point made by Susan Lee Johnson in her study of the California Gold Rush’s Southern Mines offers a related way to understand women’s historiographic disappearance. Johnson writes, “Our failure to consider such scenes and ask such questions is part of a larger problem of collective memory.” Johnson argues that the Gold Rush came to be “remembered as the historical property of Anglo Americans” and men. Similarly, the antebellum US Army’s military history remains a story populated almost entirely by white men, mostly high-ranking ones.Footnote 35 Much as the ideologies of conquest that produced Manifest Destiny have “masked the long history of Native peoples,” the histories of Indigenous and Mexican women at war have been subject to a process of erasure that left them doubly concealed.Footnote 36

Leaving these women out misses how paternalism shaped army culture; naturalized officers’ authority over enlisted men; and provided a cultural foundation for military law, policy, and strategy. This project begins to expose the “circuits of knowledge production” that erased women from army records and military history.Footnote 37 Seeing army documents – like reports of battles, casualty lists, correspondence, journals, and drawings – as a genre shaped by army culture and individual (white male) authors allows one to uncover new perspectives and insights.

This project locates points of connection by drawing on material written by soldiers of all ranks. It traces how and why facts and interpretations changed as information moved up or down the chain of command. While this approach reveals points of difference, it also reveals specific areas of unity – those assumptions and beliefs held by most military men. The view that soldiers should protect women was one such potential source of agreement. It sometimes served as a common language between officers and enlisted men, sometimes as a path for enlisted men to challenge officers’ claims to moral superiority, and sometimes as a justification for changes in military policy and strategy. By 1848, these workings cohered into an engine of army paternalism, a deep-seated logic whose machinations were sometimes overt, sometimes submerged, and underlay the army’s choices. I call this the logic of protection.Footnote 38

This logic of protection stretched and adapted to accommodate use by the many groups of men within the army. For all that changeability, its core remained static – it was always about the soldiers, not the women the army claimed to protect. Like Edward Said’s Orientalism, it “responded more to the culture that produced it,” army culture, “than to its putative object,” women.Footnote 39 It expressed individual and institutional male identities as protectors. It always needed a subject but did not require universal applicability. Instead, the logic attached to the best available subjects for protection. Typically, this was whatever group of women over whom the army held direct power and came the closest to white women.

In Florida, the army captured and thus had power over Seminole women, who became its subjects. In Mexico, under US occupation, Mexican women became the army’s preferred subject population. Perceived proximity to “civilization” as opposed to “savagery” established a spectrum of preference, where the army leveraged the logic of protection in accordance with proximity to an idealized recipient of chivalric masculinity. The logic of protection was situational, never absolute, because it was always about upholding the military belief of the soldier-protector. Paternalism was a malleable ideology that the army could use in many ways. There remained the potential for tension, even dissonance, between a self-perception of protecting women and a reality of wartime violence.

The Army Culture of Paternalism

Army use of the logic of protection could be sincere or insincere, performative or personal, and reached freely across the boundaries between military and popular cultures. Although descriptions of a unique army culture often rest on officers’ distance from civilian life, US society profoundly influenced the army. Army culture was, as historian Kristin Hoganson writes of late nineteenth-century US culture, a “framework from within which individuals perceived and responded to the wider world,” and cultural borrowing strengthened that framework.Footnote 40 One popular source of importance to the army in the 1830s was American Romanticism. The Romantic movement – a collection of ideas, and creators, which produced various cultural products – began in the late eighteenth century in England. In the US, it took flight in the 1830s and 1840s, just as a professional US Army with a distinct culture developed. Romantics embraced the heady combination of a love for nature, commitment to nationalism, and interest in folklore to produce fiction, often focused on an Indigenous figure. Army Romantics embraced “Indian plays” and novels and added to this mix an interest in chivalry and heroism.

Army use of popular culture changed over time, but consistently located a particular place for itself within the broader cultural landscape, one that encircled and elevated it based on chivalric ideals of protecting the weak and doing one’s duty. Mass culture in the 1830s offered powerful support for increasingly distinct racial and gendered hierarchies. In the army, that enabled stricter distinctions within and without its ranks. This included a ban on recruiting Black and Indigenous men, a prohibition that bolstered the otherwise questionable whiteness of recent immigrants. Much as a gendered logic of soldierly protection softened officers’ power, so did an increasingly monolithic construction of race-based identity. Indeed, much of that logic’s usefulness came from its potential to knit together a sense of institutional superiority based on shared whiteness. Naturalized differences helped officers draw a line around soldiers and all others and let them elevate the officer corps more rigidly above enlisted men. Protection amplified similarities, smoothed out differences, and domesticated enlisted responses to officers’ authoritarian power.

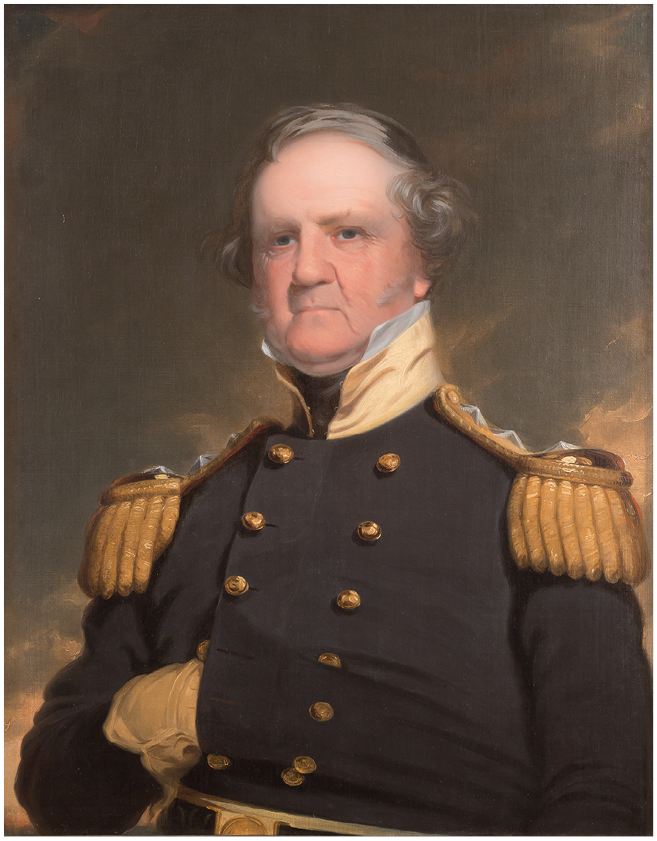

No one embodied the logic of protection’s cultural and literary roots quite like Alexander Macomb: playwright, author, and commanding general. He had been the army’s senior leader before the Second US–Seminole War and remained so until he died in 1841. Winfield Scott replaced him. During his career, Macomb published, among other works, an “Indian play” entitled Pontiac: The Siege of Detroit and a popular guide called The Practice of Courts Martial. With his interest in writing “Indian plays” and regulating courts-martial, that is, with his commitment to sentiment and discipline, Macomb represented the warp and woof of regular army paternalism (Figures 0.1 and 0.2).

Figure 0.1 Portrait of Alexander Macomb, painting by Thomas Sully, 1829.

Figure 0.1Long description

Macomb crosses his arms over his chest and his dark blue eyes gaze slightly to the viewer’s right, conveying focus on a distant point. His loose, light brown curls are moving in a faint breeze, giving a windswept, romantic feel heightened by the gold and rose toned background of a softly lit, stylized landscape.

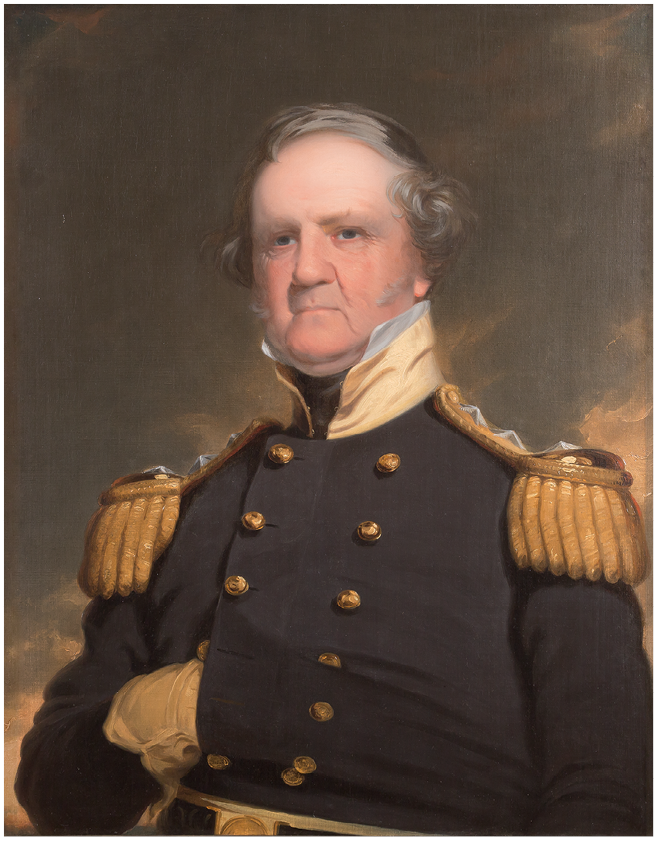

Figure 0.2 Portrait of Winfield Scott, painting by Robert Weir, 1856.

Figure 0.2Long description

Scott tucks his right hand inside his coat. His sleeves are golden silk, like his collar. A cinched belt is just visible at the painting’s bottom edge. His blue eyes gaze to the viewer’s left, and his lips are set in a neutral, determined position. His sandy hair mixed with white curls slightly above his ears. The background is stylized clouds at sunset.

Macomb’s foray into theater involved high and low-ranking affiliates of the army, from Secretary of War Lewis Cass, the “faithful and affectionate friend” and former territorial governor of Michigan to whom he dedicated Pontiac, to the US Marines who starred in a staging of the play in 1838 Washington. His efforts reflected a lifelong embrace of the theater of war. While commanding Detroit’s military garrison in 1816, “the officers under his command had organized and conducted the first known theatre activity in that city.” Though sentimentality was a “national project” in antebellum US society, scholars of the army have not previously applied such insights to analyses of military culture.Footnote 41 The wartime setting of these plays exemplified this entanglement. The best known, Metamora, drew on the distant King Philip’s War. Pontiac fictionalized the 1763 Pontiac’s Rebellion. Military and civilian audiences alike found meaning from within these narratives.Footnote 42

“Indian plays” did the cultural work of paternalism through an “emphasis on indigenous traditions, folk customs, and the glorification of the national past” that “dovetailed with the drive towards cultural nationalism in the newly independent nation.”Footnote 43 That work dealt with the essential question of how, in a republican democracy, an authoritarian institution like the army could justify its control over citizens. In response to this question, officers and enlisted men used sentimental culture to give different answers.

Enlisted men used the era’s rugged individualism to emphasize that they were men of action. One anonymous writer who published a collection of stories glorifying enlisted men and pillorying the officer corps asserted that he wrote while serving in the regular army. This veteran dedicated his book to “the rank and file” and endowed his soldier-heroes with “handsome forms” and “expressive features” showing they were “God’s noblest works.” This beauty betokened manly virtues. Corporal Mannerly was “a man of feeling” and “one of undaunted courage, firm resolution, and who would sooner lose his life than be dishonored.” The author delivered harsh judgment on officers: “scorn and degradation has been heaped upon me by pitiful apologies for men,” who were usually West Point graduates. Cruel and cowardly officers endowed with charactonyms such as “Lieutenant Hardcase” and “Captain Meanman” abused their power and “degraded” Mannerly.Footnote 44 The message was unequivocal – although soldiers were inferior to officers in rank, they were the superior men. They made a civilization out of the wilderness and killed those Indigenous people who resisted, all with their own hands. Officers, aristocratic and weak by comparison, just gave the orders.

Officers experienced mass culture in another way entirely. Macomb’s Pontiac drew on the themes of “civilization” extinguishing “savagery” to imbue the US Army with purpose. Writing on the British army, Daniel Ussishkin argues in Morale: A Modern British History that “the notion of morale has been inherently linked to understandings of, and expectations from, the exercise of power in modern mass-democracy.” He describes how managing collective morale assumes that modern citizens cannot and should not “be brought to submission by coercive forces alone. In a liberal-democratic polity, coercion would be impractical, inefficient, and undesirable.” To leverage morale to produce discipline requires the “harmonization of subjective freedom and collective goals (however defined).” Officers’ dilemma was how to impose military discipline – conceived as absolute obedience to one’s superiors – on white men, members of a democratizing and slaveholding society that increasingly rejected physical punishment as fit only for the enslaved. The question of how the US Army navigated this process of internalizing discipline and domesticating enlisted men has yet to be pursued, and this study of army culture makes a start. Part of the answer was the shared paternalistic, civilizational project that writers like Macomb described.Footnote 45

While the army implemented Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act and fought Seminole groups in Florida, authors drew on “both the noble and the savage Indian” to evoke feeling in readers and audiences and connect them to the nation’s contested frontiers. They used the “nostalgia and pity aroused” by the purportedly “dying race” of a monolithically constructed “Indian” to leave an “impression of the Indian as rapidly passing away before the onslaught of civilization.”Footnote 46 Popular writers had a different impact a few years later in Mexico. Rather than emphasizing the “noble savage” they embraced depictions of the US Army as chivalric rescuers of Mexican women, the willing partners of superior US soldiers. Shifting modes of thought about enemy women marked cultural change. Unlike “Indian plays,” the war stories from the US–Mexican War a decade later emphasized how US rescues of Mexican women underscored Anglo-American superiority, a narrative officers used to bolster their power and the regular army’s institutional legitimacy.Footnote 47

Beyond literature, another type of army writing – courts-martial records – marked the institution’s development over the same period. In his study of antebellum soldiers, Dale Steinhauer demonstrates that “irregularities in courts-martial became so common during the years of the Seminole War” that at the behest of the Secretary of War, Macomb published The Practice of Courts-Martial in 1840 to remedy the problem.Footnote 48 He sought “the introduction of a regular system of procedure in Courts-Martial” in response to wide discrepancies in how army officers assigned to courts-martial duty carried out their responsibilities.Footnote 49 Discrepancies often involved breaches of protocol concerning rank, the very stuff that formed officers’ power.

Macomb wrote from personal experience. In 1837, he refused to approve the results of a court-martial in Fort Marks, Florida, for inattention to rank. The appointed officers had improperly convicted a soldier of mutiny, Macomb declared, because mutiny by its legal definition referred to violence against officers. The soldier had attempted to shoot a non-commissioned officer – a sergeant. Macomb vented his frustration, writing that “in every instance where the word officer is used in the Articles of War, without qualification, it means Commissioned Officer: a Non-Commissioned Officer is, technically, not considered an officer, the classification being officer, non-commissioned officer, and private.” Because of this discrepancy, Macomb ruled that the prisoner must be released from confinement and would therefore escape “a just punishment for one of the most dangerous crimes of which a soldier can be guilty.”Footnote 50 He sought to guard the legal gates around officership and systematize how officers disciplined enlisted men. Where officers like Macomb wanted during the Second US–Seminole War to give form to a limited concept of military justice, Macomb’s successor Winfield Scott would drastically expand the scope of military justice in the Mexican War with the advent of military commissions. During these years, a changing army culture grew in tandem with a remarkable expansion and bureaucratization of military power.

Macomb’s conception of discipline had much to do with what many scholars have termed an era of professionalization. Between 1835 and 1848, from the early years fighting the Seminole people in Florida to its final months in Mexico, the army gained considerable legitimacy in the US public’s eyes thanks largely to its increasingly West Point educated, middling officer corps. During these years, it enacted the policy of Indian Removal, fought a seven-year war to forcibly relocate the Seminole from Florida, and later conquered and occupied much of Mexico at the behest of President James Polk – a long decade full of wartime crucibles. William Skelton’s An American Profession of Arms defines professionalism as “a regular system of recruitment and professional education, a well-defined area of responsibility, a considerable degree of continuity in its membership, and permanent institutions to maintain internal cohesion and military expertise.”Footnote 51 Skelton reveals those traits in the regular officer corps decades before the Civil War. In the 1830s, the army systematically recruited men through a consolidated recruitment service, educated its officers at the military academy, accepted civilian authority, and developed regulations to govern conduct.

For these reasons, recent histories have established the Jacksonian era as formative for the US Army. While historians have increasingly understood these years as necessary to a rapidly professionalizing institution, such scholarship has focused on army officers commissioned out of West Point and educated by a standardized curriculum for the “profession of arms.” But this focus on the officer corps is just one (important) part of a significant demographic shift. While West Pointers came to dominate the officer corps, foreign-born recruits came to numerically dominate the enlisted force. Just as the 1840s saw an emergent middle-class, to include increasingly respectable army officers, within the same decade, immigration, especially from Ireland, remade the white working-class and thus the army’s recruiting pool.Footnote 52 Irish recruits were not only different from native-born officers in terms of their birth country, but were often Catholic, religiously distinct from the overwhelmingly Protestant officer corps. It was yet another source of difference-making and thus of control even though officers and US politicians made little effort to develop official Protestantism in the army. Officers and enlisted men were strikingly dissimilar, but little scholarship considers what it meant for the army to be increasingly led by West Pointers and manned by foreign-born soldiers.

Simultaneously, the Jacksonian era’s political climate featured a growing belief in the political equality of white men alongside a strain of sputtering nativism that ebbed and flowed with the nation’s economic fortunes and rates of immigration. Although officers and enlisted men were different in many ways, the Jacksonian period’s dramatic shift to universal white male suffrage promised (or, for officers, threatened) a leveling sameness.Footnote 53 The complex interplay – of officer and enlisted, of middle-class Protestant academy graduates and poor, recent Catholic immigrants, of equality and exclusion – merits closer attention. Untangling these many dynamics suggests how officers were not just part of a cohort of middle-class men joining professions. They were leaders of the most authoritarian organization of their time within the United States.

An army-specific version of chivalry served as both a source of officers’ power and a binding agent for a broader army culture. This iteration of chivalry was a smaller and shallower system of ideas than the medieval original – a sentimental copy. It focused on protecting innocent women from villainous men and fighting for women’s love. Although such declarations seemed to belong to an imagined past of gallant knights, the army’s use of chivalric discourse spoke clearly to the profession of arms. Gendered discourse about women channeled and narrowed the public service ideal that animated professionalization in US society. Where doctors’ public service ethic bound them to help all and harm none, the army preferred a more particular set of ethical restraints: to help (in theory) those who were supposedly harmless – women and children – and to destroy male combatants as dictated by the civilian government.

In this fashion, professionalization bureaucratized the separation of supposedly harmless women from war and its histories. Women’s absence from records of war and the chivalric positioning of women as outsiders, victims, and subjects of rescue emphasized masculine mastery of professional military knowledge because “the social role and status of professionals is legitimated by their esoteric expertise.”Footnote 54 Military men’s claims to the unique skills and abilities necessary to protect women (incapable, by definition, of defending themselves) elevated soldiers even as it submerged women’s wartime activities.

One can begin to interrogate how claims to professionalization obscured relations of power between men and women, and among soldiers with the paternalistic notion of the army family. Officers brought the disciplinary mechanisms of the state and the family to bear on enlisted men.Footnote 55 When scholars begin within an officer’s army family of subordinates, and works outward to the army as an institution, paternalism displaces professionalism as the dominant paradigm. As paternalists, officers bolstered their authority with a father’s naturalized power over his family, within which he disciplined his soldiers, servants, and enslaved people – his permanent children – and protected his women. In officers’ estimations, some soldiers were good children, but most were prone to misbehavior and required a firm hand. The fact that most enlisted men were young and unmarried made it even easier for officers to sustain this outlook. Fatherly authority cloaked and naturalized power.

Officers smoothed out the rough edges of their authority in part by using the genre of army writing, with its reports, regulations, courts-martial, and correspondence, perpetuating officers as the army’s “voice of authority.” Mary Beard maintains that one must consider how such authority is constructed, and officers used discourse emphasizing the army’s obligation toward women to bind enlisted men to their officers. Such language offered a potential point of agreement between the different cultures of middling officers and poor, immigrant soldiers of varying nationalities and ethnicities. Like other architects of professionalization, antebellum regular army officers became “if not exactly administrators of ‘discipline,’ certainly its handmaidens and accessories.” If power produces truth, officers’ power made officers’ truths, and therefore officers’ military histories.Footnote 56 Rather than simple repositories of information, army archives were artful constructions.

Enemy Women and Army Policy

When enemy women resisted the US Army, they forced soldiers to confront contradictions between an idealized female and the real threat such women posed.Footnote 57 It was paternalism in extremis. During the formative, institution-building years that followed West Point’s rise to prominence, the regular army fought two wars – the Second US–Seminole War and the US–Mexican War. Cultural change, born of war, shaped military and foreign policy.

The same decades that witnessed the development of a coherent army culture also saw fierce competition between different ideals of manhood in US society. Skelton and Watson argue that army professionalization happened before the Civil War and not in the late nineteenth century. In those same decades, Amy Greenberg argues for the importance of competing masculinities that prefaced the late century rise of hegemonic “primitive” masculinity based on physical prowess. Her work encompasses sites of masculinity, from urban volunteer fire departments to the Mexican War-era army to filibustering expeditions.Footnote 58 Greenberg draws to an extent on Anthony Rotundo, whose work on northern middle-class manhood in the long nineteenth century argued for a shift from communal manhood, to self-made manhood, to passionate manhood defined in stark contrast to womanliness. In Manifest Manhood, Greenberg departs from Rotundo’s progression to argue that antebellum debates over manhood debates coalesced by 1848 into “two preeminent and dueling mid-century masculinities: restrained manhood and martial manhood.” The latter draws on McCurry’s “martial manhood,” which was “grounded in the household and in the prerogatives of masters.” While other varieties of masculine identity remained available, these gained preeminence and “competed for hegemony” in different arenas, for instance, in the US–Mexican War, where martial men strongly supported “aggressive expansionism.”Footnote 59

Yet, the regular soldiers who were the actual instruments of this discourse – who performed aggressive expansion rather than expressed aggressive expansionism – straddled both schools of masculinity. The regulars and the society they served had an uneasy relationship. Although the US public generally accepted regular officers, they disdained poor, immigrant enlisted men. Moreover, many Jacksonians remained uncomfortable with the idea of a standing US Army. Popular society preferred the volunteers, citizen-soldiers who performed temporary military service and returned home. In contrast to “aggressive, violent” volunteers who adhered to martial masculinity and believed that Indigenous and Mexican noncombatants were “racial inferiors” they could attack with impunity, regulars insisted they were professionals, more competent than undisciplined, ineffective volunteer soldiers.Footnote 60 Officers, like Greenberg’s martial men, elided class both to support “territorial expansionism grounded in masculine privilege,” and to create a sense of unity that included enlisted men. Yet, those officers also “grounded their identities” in their army families, “valued expertise,” and endeavored to promote temperance among soldiers.Footnote 61 The US Army combined elements of the leading restrained and martial modes in a developing army culture.

After his Indian Removal Act passed in May 1830, Andrew Jackson’s annual message to Congress in December of that year lauded his “benevolent policy” to affect the “speedy removal” of Indigenous tribes from the nation’s southeastern slave states. He claimed that this “not only liberal, but generous” program would allow US settlements to grow, separating “the Indians from immediate contact” with white settlers so Native groups could be free “in their own way,” causing “them gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits” and form “civilized” communities.Footnote 62 The regulars reshaped this imperial message to fit their needs.

Their subset of the masculine ideal combined elements of the predominant restrained and martial modes into a self-conception of regulars as the arbiters of government protection. Moreover, because regulars considered themselves superior to volunteers and viewed white settler men with contempt, they often justified their participation in forcing Seminole people out of Florida much as Jackson did – by claiming that moving them away from white settlers would benefit Native peoples. This paternal strain in army culture continued to gain adherents in Mexico, where regulars expressed an institutional identity in contrast to the extreme kind of martial manhood (marked by atrocity) that regulars attributed to volunteers. As a result, even as the army patently invaded Mexican territory, its members claimed that they came to protect Mexicans. By 1848, the logic of protection animated and expressed an increasingly dominant army culture of paternalism.

The officer corps’ claims to professionalization sped this process along. Simultaneously, officers rationalized their authoritarian power over subordinates by pointing to increased immigration, which justified parental control over supposedly child-like foreign-born soldiers. Officers also drew on mass cultural currents to naturalize hierarchies of difference and validate their efforts to position all soldiers, regardless of rank, above non-white men and in front of all women as their chivalric protectors. The logic of protection – the set of ideas related to the deeply held belief that the soldier as an individual and the regular army as an organization protected women (who in return remained thankful and sometimes helpful noncombatants) – enables one to map changes to army culture in its formative period. Based on shifting army experiences with enemy women – Seminole and Creek women in Florida, Mexican, and Indigenous women in Mexico – soldiers changed the logic of protection, altered how the army acted on that logic, and generated violent consequences for the women they claimed to protect.Footnote 63

Taking seriously the available source material on women illuminates the gendered history of army culture. Feminist scholarship on the “interlocking of sexual, racial patterns of dominance that crisscross historical fields” has the potential to open new areas of research in the field of military history.Footnote 64 This approach provides a method to critically interpret army writing as a genre – one as formulaic and purposeful as any “Indian play” or penny press paper. Straightforward readings of army writing miss the discursive process that sought to resolve war’s complex realities into the simple, bureaucratically digestible report formats. Grasping that process matters because it operated as an engine of legitimization for the profession of arms.Footnote 65 Army leaders from Alexander Macomb to Winfield Scott were part of a lineage of officers who produced army culture and who attempted throughout their careers to write their way into their desired future, using the specific cultural forms that comprised official army correspondence.

Moreover, the genre of army writing was not static, even if elements like authors’ need to promote their bravery and successes remained. The army’s wartime experiences in Florida from 1835 to 1842, compared to those in Mexico from 1846 to 1848, straddled massive changes to transportation and print technologies. These years, so formative for the army, also transformed the nation. Cities sprung up, the army conquered new territories and expelled more Indigenous communities, immigration changed the country’s demographic character, slavery grew, and technology integrated “this vast and varied empire through dramatic and sudden improvements in communications.” Popular culture responded to these multiple changes through new popular media, which Shelley Streeby calls the “culture of sensation.”Footnote 66 Army culture also responded by changing. Before the Second US–Seminole War, commanding general Alexander Macomb authored a guide to courts-martial and a well-known “Indian play.” After the Mexican War, Macomb’s successor Winfield Scott issued a flurry of grand proclamations and courts-martial proceedings that immediately went into print by the many soldier-operated newspapers along the army’s path. Soon after, his words reached national periodicals through the pens of US war correspondents. Like the nation, the army found itself remade by the print revolution.

This project is in part a story of what the early regular army, and generations of military historians, wanted to believe: that “civilized” norms of warfare protected noncombatants; that innocent women deserved military protection; and that US officers and enlisted men were willing and able to give that protection. Upon these beliefs, an army culture of paternalism grew, including a professionalizing officer corps and a bureaucratized system of discipline to control enlisted men. Breaking up the “policy fiction” that women existed separately from war allows one to see how army culture developed between 1835 and 1848.Footnote 67 It also illuminates how that culture ultimately shaped, rather than removed, violence against women.