At the July 2023 Ethereum Community ConferenceFootnote 1 reporter Camila Russo gave a talk titled “Crypto Is a Theatre Right Now” ([EthCC] Livestream 4 2023). Her argument, revolving around the various “theatres” of the crypto ecosystem—practices of “Decentralization theatre,” “Governance theatre,” and “Community theatre”—was not so much concerned with theatricality per se as much as the vague assertion that “people in crypto [are] putting on a show. A façade” (Russo Reference Russo2023b). In Russo’s explanation, “theatre” is the shorthand that encapsulates “why crypto sucks right now” (Russo Reference Russo2023a). In conjuring theatre to argue that crypto projects are devoid of substance, just putting on a show, and without “real” effects, Russo joins a long line of Western antitheatricalists.Footnote 2 Imagining the theatrical site and theatrical practice as hollow, Russo uses “theatre” to connote a surface without substance. For a technology alleging to remake all socio-political-economic relations, there can be no greater crime.

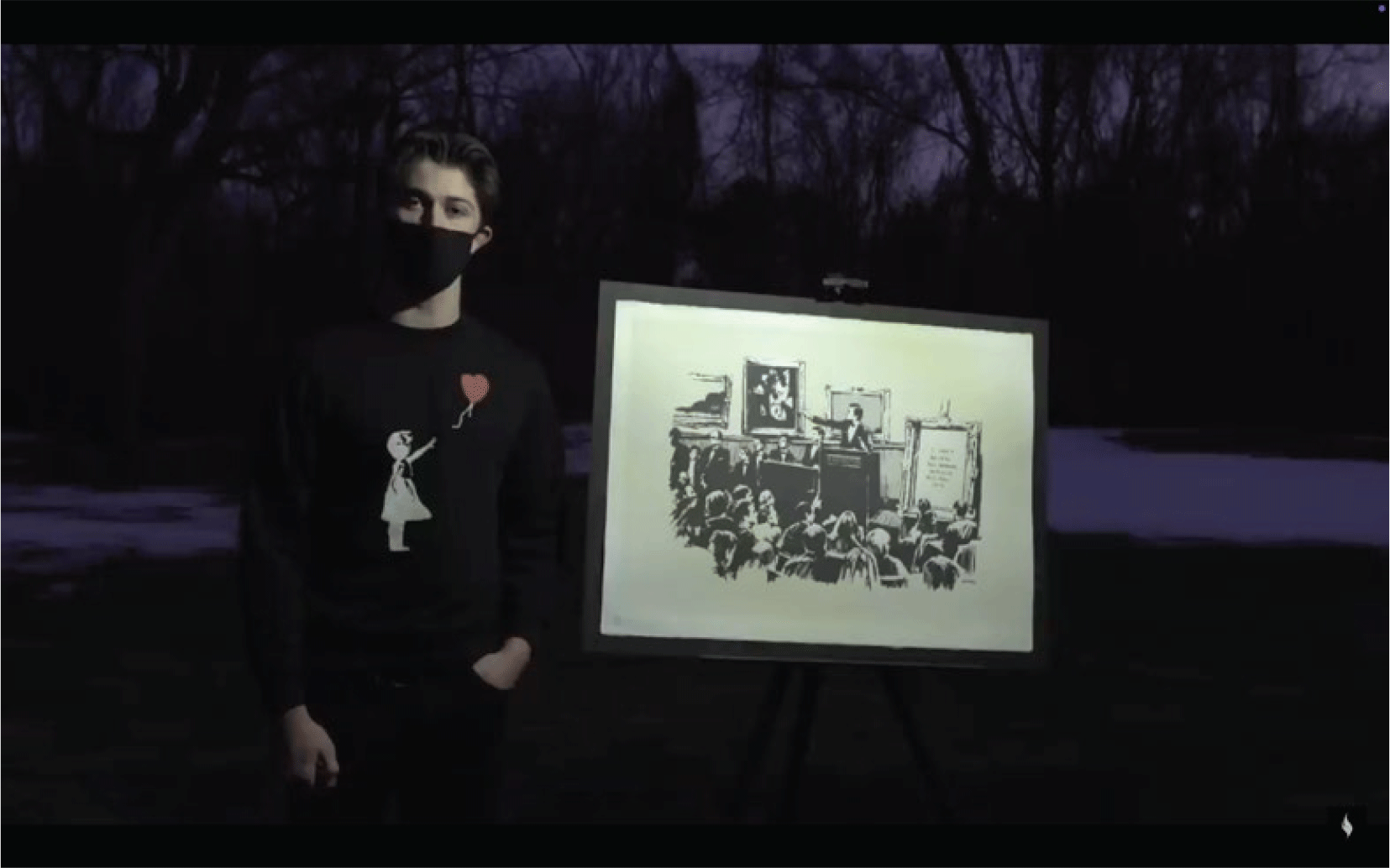

Figure 1. In a livestream from an undisclosed location, Burnt Banksy stands beside the Morons print. “Authentic Banksy Art Burning Ceremony (NFT)” YouTube, 3 March 2021. (www.youtube.com/watch?v&C4wm-p_VFh0; screenshot by Ilana Khanin)

Russo’s criticism of vacuousness is not the first time crypto endeavors have been condemned as empty promises, though her use of the language of theatre in doing so is distinctive. The visual art market, for instance, is often the reference for criticisms of non-fungible tokens (NFTs)—blockchain digital assets—since, as Amelia Winger-Bearskin notes, “almost every mainstream critique leveled against NFTs applies just as easily to art markets” (2022).Footnote 3

Russo is onto something in identifying the intersections between blockchain-based outputs and antitheatrical anxieties, a comparison that is especially apt for thinking through NFTs at the height of their proliferation in 2021. Rather than classifying NFTs as art objects, they might better be understood as theatrical practices that evince antitheatrical reflexes. The theatricality of NFTs is on display and at issue, such as in Burnt Banksy’s livestreamed burning of Banksy’s Morons print to transform it into an NFT (XIONFootnote 4 2021). Theatricality constructs the narratives, shapes the presentations, and hides the mechanisms while simultaneously highlighting the form. In response, antitheatrical anxieties emerge as the primary avenue of critique, creating an environment of digital antitheatricality. I extrapolateFootnote 5 on the symbiosis of theatrical and antitheatrical exchanges in Western, mainstream blockchain culture at its peak, for a recounting of the NFT ecosystem that accounts for the manifestations of these anxieties and considers their history.

Setting the Stage

The NFT hype was characterized by several surprising sales, and so Burnt Banksy is just one instance of a non-NFT image becoming an NFT under the public gaze. The period is marked mainly by digital artist Mike Winkelmann’s (aka Beeple) sale of his mosaic jpeg Everydays: The First 5000 Days at a Christie’s auction for US $69 million, in what the auction house dubbed “monumental” (Christie’s 2021). The hype, however, was more widespread. The “Charlie Bit My Finger” YouTube video sold for over $760,000. The “Disaster Girl” meme sold for $500,000. “Grumpy Cat,” “Nyan Cat,” “Doge,” and “Pepe the Frog” also took on NFT forms that sold for more money than was imaginable even a few years prior. For collectible PFP NFTs,Footnote 6 such as CryptoPunks and Bored Ape Yacht Club, people paid multiple millions of dollars for ownership of a single image. Everything was changing so fast that in August 2021, Paris Hilton was explaining to Jimmy Fallon the basic premise of an NFT—“a digital contract that’s on the blockchain so you can […] sell anything from art to music to experiences [to] physical objects” (Hilton Reference Hilton2021)—and a few months later, by January 2022, Fallon had already purchased a Bored Ape NFT for over $200,000 (Contreras Reference Contreras2022).

These purchases took place against the backdrop of “crypto” infiltrating life beyond niche Twitter (now X) and Discord communities. The 2022 Superbowl was dubbed the “Crypto Bowl” for its sheer number of crypto commercials, the most memorable of which was a time-traveling Larry David as a skeptic of wheels, forks, toilets, coffee, and space travel (FTX Reference Commercial2022).Footnote 7 Matt Damon’s ad for Crypto.com rehearsed a world where “fortune favors the brave” and that fortune is cryptocurrency (Crypto.com 2021).Footnote 8 Other celebrities threw their names in behind various crypto coins, NFTs, and other blockchain schemes: Lindsay Lohan, Gwyneth Paltrow, Snoop Dogg, Serena Williams, Kim Kardashian, Paris Hilton, and Reese Witherspoon are only a small fraction of the cohort (Kelley Reference Kelley2023). Somewhere between actuality and symbolism, this period encapsulated the greater possibilities of NFTs as a part of public life. It’s not that it brought new developments to the technology per se; rather, these accumulating events theatricalized a present where the technology was always already and forevermore embedded in the landscape of everyday life, as both the means and the end of transactional exchange.

Yet, NFTs were never the limit of crypto’s promise; they were part of the aspirational landscape encapsulated by “Web3.”Footnote 9 Web3 proponents made many promises, but the overarching goal was to create a blockchain-based internet. In this system, NFTs would be central in facilitating digital transactions.

However, Web3’s implementation always remained hazy. Evgeny Morozov, in his “Web3: A Map in Search of Territory” (2022), notes that Web3’s capacity to incite the imagination prevails over its technical capabilities. He argues that the way crypto is described, narrated, and understood has no basis in reality; instead, some are “talking it into existence” via a “narrative” that proclaims the technology’s future to be all but decided. Morozov understands this to have dire political stakes, since the battle by venture capitalists to “privatize the future” ultimately “forestall[s] any alternative conceptions of [Web3’s] institutional and political make-up.” He articulates how the future, in no uncertain terms, is described as one where, among other things, “more objects, from books to films, will turn into NFTs.” The process of crypto entering everyday life is the proof-of-concept for a larger takeover.

Morozov’s argument turns theoretical when he conjures the term performative. “We are finally talking about performativity,” he writes, “with new realities being born out of the very language itself” (Morozov Reference Morozov2022).Footnote 10 Later he defines that term as “the idea that language creates realities rather than merely reflects them.” Yet, key to his argument is the contention that Web3 does not exist—“there is no ‘there’ there.” Reality is, at once, being actively created by language while simultaneously being nonexistent despite language. So, as far as the Austinian speech act goes, Web3 fails to qualify.

Tellingly, there is a parallel here to Austin’s example of disqualified speech: the moment of theatre. Austin specifies that the “performative utterance will […] be in a peculiar way hollow or void if said by an actor on the stage” (1962:22). The theatrical event is explicitly excluded because it is the something else: the actor’s words might affect the audience, but they are not performative in that they do not alter the composition of social realities. The moment of performance fails to move into the performative, marking the distinction between the two oft-conflated terms. Web3 rhetoric, by Morozov’s account, falls short too. It is unable to overcome the hurdles of physics and time, unable to conjure the technology into existence, even as it imagines the technology and its effects as already decided. Morozov, in critiquing the machinations of Web3 and its advocates, betrays the contradictions of antitheatrical anxiety.Footnote 11 He fears that language theatricalized might come to have performative effects, and thereby conflates description and intention with certain outcomes. It is not performativity, then, that would explain what is going on in the ecosystem Morozov describes, but rather theatricality.

Theatricalizing NFTs

While surfacing productive questions about authenticity, excess, mechanics, and (in)efficiencies, “theatricality” retains its ambiguity tied to its contradictions—efficacious and void, real and inauthentic—often summoned to invalidate its theoretical and practical usefulness. In the only reference to the theatricality of NFTs I can locate, A.V. Marraccini writes that a subset of NFTs referencing their own medium specificity—where the NFT becomes a “theatre of exchange” and “performance of exchange”—underlines the NFT’s status as “an inherently financial instrument” (2022). Arriving at this analysis via Michael Fried, Marraccini argues that the theatricality of the exchange becomes wrapped into the value of the NFT-as-object. Fried’s narration of objects as theatrical stems from a preoccupation with the art-goers presence in the museum space, so that the object is superseded by the event of spectatorship, the “actual circumstances in which the beholder encounters literalist work” (1967:15). In Marraccini’s view, the NFT is not about the image connected to the proof-of-ownership metadata, but the experience of the NFT market within which these encounters take place.

But here I am interested in a different strain of theatricality, and its antitheatrical anxieties, aligned to theatre and performance and not necessitated by the exchange mechanism. I understand the NFT not to be an art object that has been expanded toward theatricality through the experience of its circulation; rather, it is first a practice and second its documented digital object. I turn to Diana Taylor’s definition of theatricality in The Archive and the Repertoire, where she notes:

Theatricality […] sustains a scenario, a paradigmatic set up that relies on supposedly live participants, structured around a schematic plot, with an intended (though adaptable) end […] It differs from spectacle in that theatricality highlights the mechanics of spectacle. (2003:13)

More than the language of just for show, theatricality underlines that which is left undetected in the NFT transaction and its subsequent popular narrations: that which does not make it onto the blockchain. In the blockchain’s devotion to eternal documentation of transactions, immutable records, and permanent collections, the collateral damage is the ephemera of these practices.

By accounting for the theatricality of these transactions, I go beyond the financial consequences of these purchases, clarifying their stakes as crafted events that leave traces and can disappear. Antitheatricality offers a way of understanding critiques of popular presentations in a purposefully opaque apparatus. I’m thinking here of Martin Puchner’s exploration of the relationship between the two terms (via Jonas Barish [Reference Barish1981]), where “theatre and anti-theatricality suddenly no longer appear as opposing forces […] but as deeply intertwined systems, enabling one another and propelling one another forward in history” (2001:355). Digital antitheatricality is a more apt way to understand the crypto cultural moment that emerged in mainstream Western thought as NFT hype, accounting both for the proliferation of NFTs as practice, and the assumptions behind its criticisms.Footnote 12

NFTs, Antitheatricalized

“Right now, I’m going to burn this Banksy,” says the masked individual in the Twitter livestream (XION 2021). If this was a theatrical production, I might critique it for its overburdened foreshadowing: the pseudonym Burnt Banksy; the “Girl with Balloon”—infamously shredded upon purchase—print on his sweater; the irony of the sacrificial artwork’s title—Morons. Burnt BanksyFootnote 13 takes out his lighter and, with difficulty, ignites the work. The livestream audience waits. He waits. When the artwork disappears, he leaves.

Burnt Banksy refers both to the individual appearing in the video and to the group of investors behind the purchase of the certified Banksy print from Taglialatella Galleries in New York, with the purpose of turning it into an NFT through Banksy’s artwork arson.Footnote 14 Banksy, the artist, was not involved in the Burnt Banksy project, but Burnt Banksy’s statement to CoinDesk speculates that Banksy “would appreciate what we are doing since he also promotes creativity and iconoclastic ideas” (in Crawley Reference Crawley2021). Curiously, this event sat at a crucial turning point for non-fungible tokens: between the day Christie’s opened bidding for Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days (25 February 2021) and the day of its sale for a record-breaking price (11 March 2021). The 3 March 2021 livestream on Twitter brought in nearly 300,000 viewers, some of whom shared their reactions to the event in real time (XION 2021).Footnote 15 These casual comments encapsulate the microcosm of competing viewpoints running the gamut from utopian idealism to dystopian dread, and summarizing both attitudes toward this theatrical NFT DIY demonstration in particular and blockchain technology in general.

Many viewers of the livestream shared concerns about the execution of the print burning, highlighting theatricality as realized through the “mechanics of spectacle” (Taylor Reference Taylor2003:13). “His painting burning skills need some work,” comments one user. “So digital that he didn’t even hear of gasoline,” another jokes. “I don’t care that he burnt the artwork. I just care that he clearly didn’t know how to freaking burn it,” proclaims a telling comment that accepts the premise of the event’s theatricality but dwells on its subpar craft. Revealingly, three other comments make chilling comparisons: “Like a poorly made hostage video,” says one. “This is like watching ISIS destroy Palmyra. With a dessert fork,” offers another.Footnote 16 And the more extreme: “This has the feel of a cartel or isis execution video.” The position of the camera, the masked individual, the way he stands to the side of the item of destruction, the poor video quality, the nighttime scene in a nondescript location, the matter-of-fact delivery—all comfortably add up to a theatrical depiction of an aesthetics of criminality.

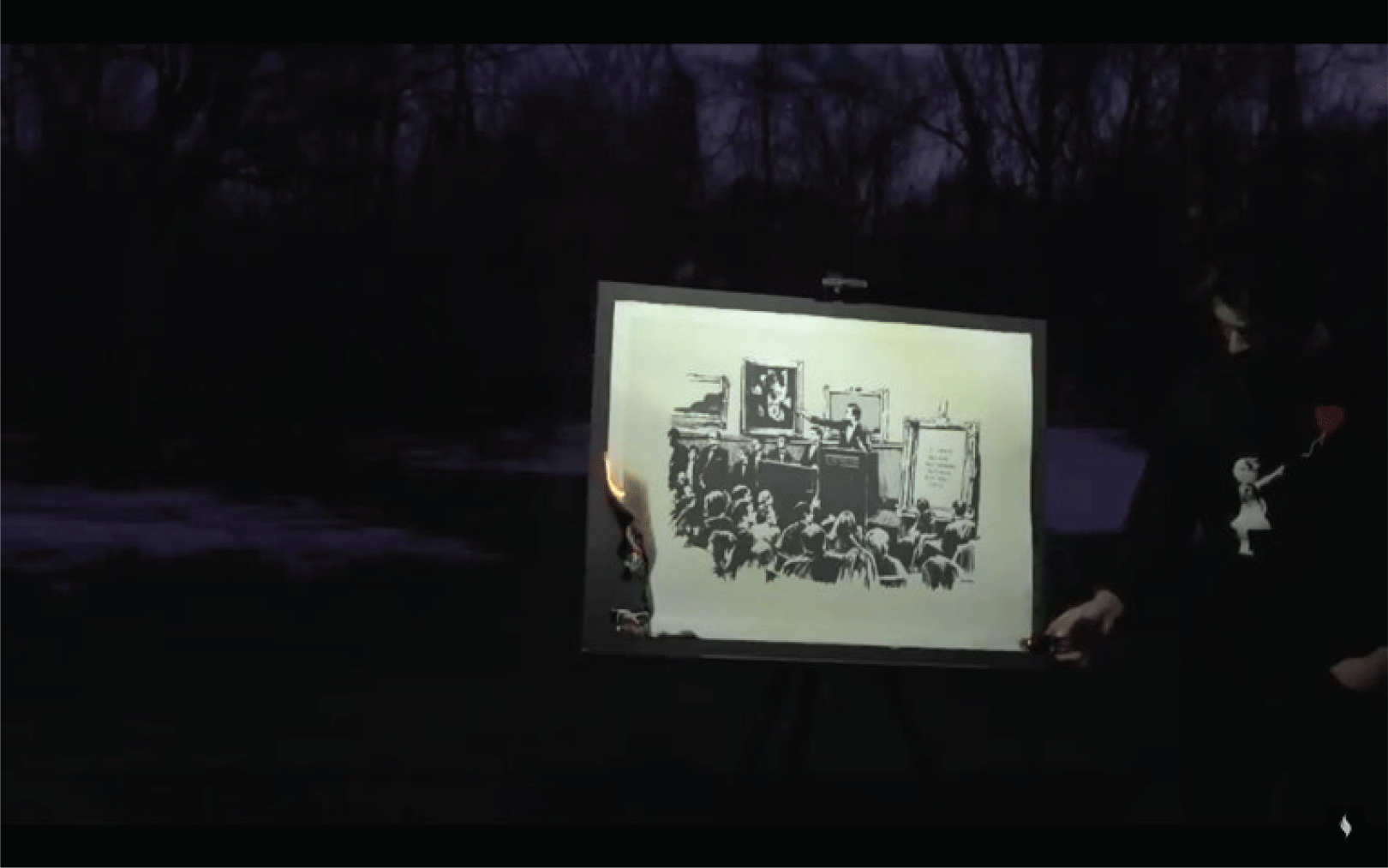

Figure 2. Struggling with the lighter, Burnt Banksy finally manages to ignite the work. “Authentic Banksy Art Burning Ceremony (NFT)” YouTube, 3 March 2021. (www.youtube.com/watch?v&C4wm-p_VFh0; screenshot by Ilana Khanin)

Others offer suggestions: a magnifying glass, a blender, lighter fluid, a better lighter. In fact, the majority of the comments are caught up in these mechanics, as they imagine the version of the video that it could but fails to be. It is an inadequate, but by no means inconsequential, realization of its staging. As one user comments: “Theatrics are lacking bro.” It is in these proposals that the awareness of the theatricality of the event comes through. “If you had used a boring company flamethrower, this would have broke the internet. Showmanship showmanship showmanship.” A Molotov cocktail thrown onto the work would have made the event “more expressive.” Another offers that “mastery of using Lighter” would have itself yielded a performance worth paying for. Someone else suggests a cinematic revision, where “Guy finishes his speech, and steps back, as he steps back, and keeps stepping back, the camera pulls back, centered on the Banksy, but keeping him in-frame. As the frame expands, another tech/artist appears. With a flame thrower. […] Whooosh.” The writing of alternate scenes speaks to the dramatic potential of the video if it were to be re-rehearsed. In the comments, these invested viewers, critical of the execution, restage the production as it happens in front of them. Despite differing opinions on the creative direction, there is a consensus that the video is a theatrical event.

Some commenters read the events as pure exhibitionism: “This was a marketing stunt. If they had not burned it nobody would even be talking about this,” says one user, offering that the financial motivations dictate the meaning of the event. Another sees it as a show of elitism, where the NFT is a “pointless product for people with so much money, they don’t know what to do with it.” In the same way that Barish notes that the “theatrical” is associated with the inauthentic, artificial, and formulaic, these viewers understand the money-making function of the livestream as its only end. In their critiques, viewers respond not to the NFT itself, but to the theatricalization as represented through this process. It is theatrical because the “stunt” is set up either “merely to amuse [the] audience” or set up just to “feed his own narcissism” (Barish Reference Barish1969:2), without having any constitutive effect. The commenters’ reactions are aligned with clear-cut antitheatrical views.

The theatrical, in antitheatricalist terms, exists in an enclosed system that seeks only to promote itself, as a commenter criticizes: “Well if crypto world is that great why don’t you go live there? Oh well it’s because it’s not real,” resonates with Barish’s description of the antitheatrical sentiments that take theatre to be an “artifice that struts in pampered self-approval and seeks no correspondence with the realities of […] the external world” (1969:3). Burnt Banksy’s theatrical presentation is, at best, merely fun, and, at worst, a demonstration of the stupidity of crypto culture. In any case, the theatrical has no real effect.

The comments are, importantly, contextualized by the speech Burnt Banksy gives prior to the controversial burning:

If we were to have the NFT and the physical piece, the value would be primarily in the physical piece. By removing the physical piece from existence and only having the NFT, we can ensure that the NFT, due to the smart contract ability of the blockchain,Footnote 17 will ensure that no one can alter the piece and it is the true piece that exists in the world. By doing this the value of the piece will then be moved onto the NFT being the only way you can have this piece anymore. (XION 2021)

In my first viewing, I was shocked by this explanation’s lack of specificity, a seeming attempt to hide Burnt Banksy’s absence of a basic understanding of the blockchain. He uses these terms hesitantly, unsure of the causes and effects of particular technologies. “The smart contract ability of the blockchain” is a confusing way to convey that the NFT will make the work unique (a controversial oversimplification but a more accurate one often used colloquially). The NFT as a “true piece” seems moralistic without a clear understanding of what those morals are. Talk of burning as “removing the physical piece from existence” is an excessively dramatic explanation of what is to come. The way value “will be moved” in the passive voice gives the sense of processes happening by themselves, conveying an overtone of magical “value” without regard to market conditions and the decisive whims of buyers.

In any case, the event of the print’s destruction is presented not as merely promotional but as the ontological prerequisite to the NFT. In a productive misreading of Peggy Phelan’s famous phrase, the Burnt Banksy NFT literally “becomes itself through disappearance” (1993:146). The lack of specificity to the way the becoming-NFT process is pre-narrated is not an oversight, but a determining feature. It mirrors a wider approach to describing crypto-technologies in ambiguous terms. In a 2018 episode of Last Week Tonight, John Oliver pinpointed this feature by describing cryptocurrency as “everything you don’t understand about money combined with everything you don’t understand about computers” (Oliver Reference Oliver2018). Ben McKenzie, in his 2023 book Easy Money, points out that even the most dedicated blockchain users struggle to describe the technical processes that take place during transactions (2023:11). This opacity, too, is key to the way blockchain-as-magic manifests in this video. Arthur C. Clarke’s famous “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” is the goal here (1973:39).Footnote 18 It is consistent with the larger dedication of crypto-discourse to the magical quality of the virtual world.

The way that this event harnesses and evokes the theatrical imaginations of its viewers through magical means is not a coincidence. And the resistance to such displays is not unique either. As Laura Levine writes in Men in Women’s Clothing, her book about the antitheatrical anxieties of the Renaissance,Footnote 19 discourses around antitheatricality and magic are tightly bound. Antitheatrical tracts are preoccupied with magic and its potential power. Inversely, texts dealing with magic and witchcraft frame their anxieties in antitheatrical terms, where magic is “‘mere’ theatricality,” not capable of performative efficacy, even as the same texts betray the fear that theatricality is “capable of radical, constitutive change” (Levine Reference Levine1994:118). The contradiction between these two positions—theatricality as simultaneously powerless and powerful—reveals the preoccupation with forces that have the power to transform objects and bodies.

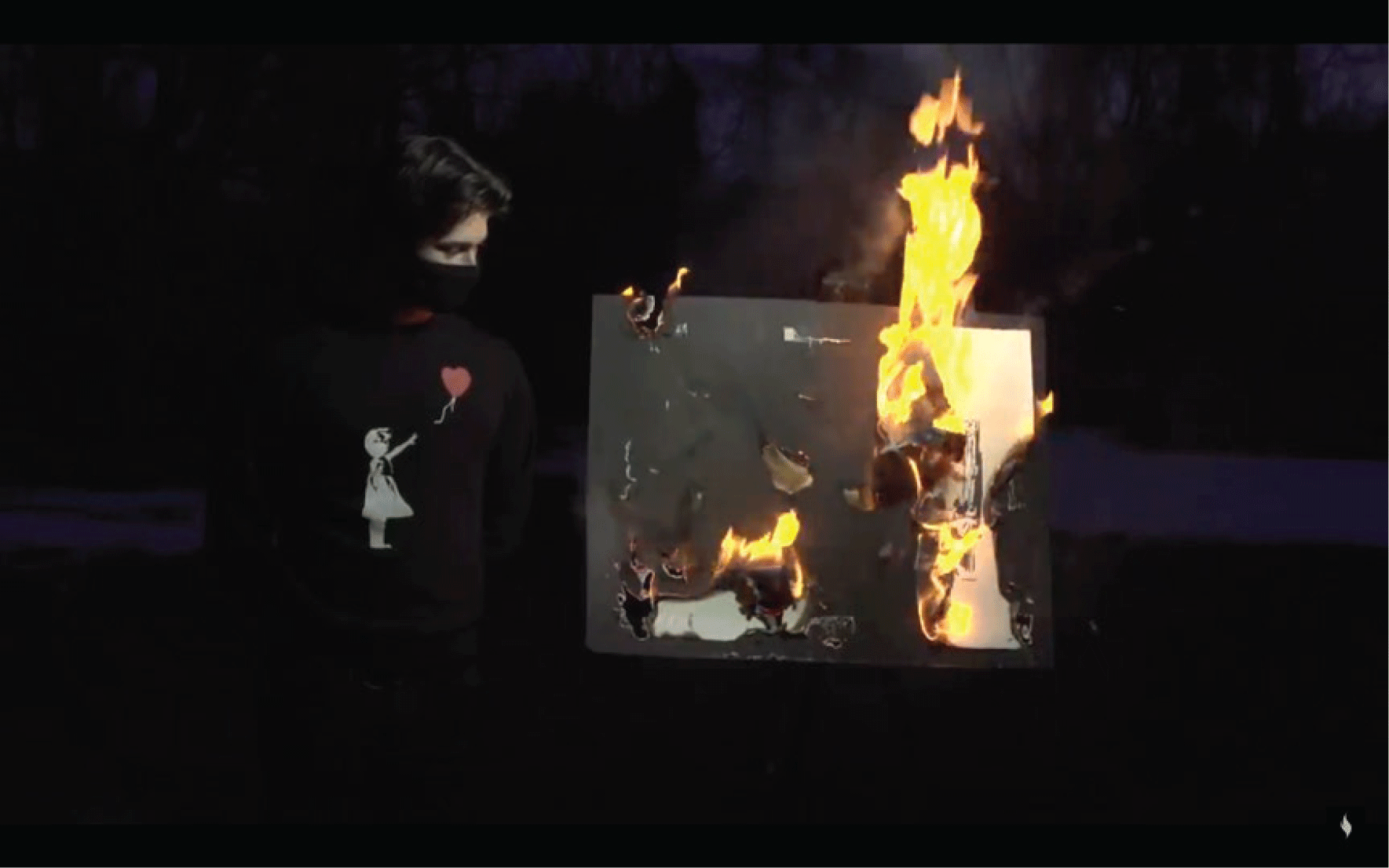

Figure 3. Morons, engulfed in flames as Burnt Banksy watches. “Authentic Banksy Art Burning Ceremony (NFT)” YouTube, 3 March 2021. (www.youtube.com/watch?v&C4wm-p_VFh0; screenshot by Ilana Khanin)

These anxieties emerge in the Burnt Banksy livestream as well. On the one hand, the theatrical presentation is received as just a show, which, though a waste of time and resources, will pass with no significant outcome. On the other hand, its audience perceives the potential of the NFT to remake the very fabric of the world—a possibility that manifests sometimes as optimism and sometimes as anxiety. This world-remaking potentiality figures the NFT as not limited to its blockchain transactions but as the instigator of more far-reaching change, creating the opportunity to joke about the “mechanics of [the] spectacle” (Taylor Reference Taylor2003:13)—the lighter, the Molotov cocktails, the parallels to hostage tapes—while not abandoning the potential impacts of the livestream’s (theatrical) displays.

A statement by @tryingtocrying198 subtly reveals what makes the comparison between Renaissance and 2021 antitheatricality possible: “Great way to build value through hype.” By defining hype as the process of creating value, @tryingtocrying198 proposes hype as its own form of modern magic, with its theatrical presentation “capable,” to echo Levine, “of radical, constitutive change” (1994:118) through effects that emanate beyond the digital domain. In conjuring hype—a word that carries heavy connotations for technology discourse in general, and blockchain discourse in particular—@tryingtocrying198 enters into a complex web of implications, none of them defined because of the frequent yet unspecific uses of the term.Footnote 20 Hype diagnoses, describes, and creates the conditions for its uptake. While it references complex cultural attitudes towards a technology—a structure of feeling in shorthand—its definition grows increasingly less defined. In fact, while it produces these meanings, it simultaneously seeks to invalidate them. Some ask, “Hype or Reality?” (Mutunkei Reference Mutunkei2023), contrasting the emotional high of hype’s hold with a sober groundedness. Others question, “Is It Hype?” (Ovide Reference Ovide2021), implying that an answer in the affirmative would point to this technology’s uselessness. Similarly, “Hype or Hope?” (Renno Reference Renno2021) sets up a mutually exclusive paradigm where hype’s euphoria can’t exist alongside hope’s forward-thinking optimism. Some wonder what is “Beyond the Hype” (Exmundo Reference Exmundo2022), calling hype a phase to get past. Hype is the opposite of reality, hope, utility, the present, and the future. These opposites evidence a skepticism toward hype, while still acknowledging it as a force capable of instigating change. Even if hype is “mere theatricality” according to @tryingtocrying198, it nevertheless, the same commenter concedes, exerts influence through shaping economic conditions, social interactions, political ideologies, and cultural imaginings.Footnote 21 Hype has the very real power to draw attention. It’s not, as these headlines imply, the opposite of reality. Rather, hype creates its own logic and reality. Hype’s “magical” effects come out of theatrical means.Footnote 22

Yet, a dictionary definition of hype offers an opportunity for a critique. “Hype” dates back only to the 1920s according to the Oxford English Dictionary and is synonymous with “deception, cheating; a confidence trick.” As @tryingtocrying198 continues: “I wonder if there is a way to prove that was in fact a real Banksy. Without proof, the ritual is empty and the value created is done so by the gullible.” In not speculating about the market value of the abstracted hyperobject (Morton Reference Morton2013) but focusing on the livestream video itself, this viewer suggests that the impact of the presentation is contingent upon whether or not the print is real. If the authenticated print is burned, as the video’s protagonist claims, then the NFT is “real.” If the print is a copy, then the NFT is illegitimate. These options, set up as mutually exclusive by the livestream spectators, reveal the anxiety underpinning an ill-defined understanding of authenticity in relation to NFTs. If the print is merely a copy, what does that mean for the NFT and the movement of value from physical to digital? The question excavates the antitheatrical “fear that copies can alter things they are merely supposed to represent” (Levine Reference Levine1994:108). Ironically, the NFT as the mechanism supposed to provide verifiable authenticity to the digital image is doomed before it is minted. Its status—copy or “real”?—is in question from the beginning.

Some commenters take this idea of NFT-as-copy further, pointing to the NFT as being itself inherently a copy regardless of whether the Banksy Morons print is certified or not. “Stupid burning someone’s hard work to make it digital I don’t want a digital copy I want something physical I can touch and feel,” writes one user, equating sensorial experiences to authenticity: “To me the nft is nothing but a fake digital copy.” “We’re all able to watch it burn [fire emoji] for free here now…so hmm…why would I want a digital copy???lol,” says another. The “magic” process of burning the NFT as a transfer of value does not satisfy the desire for tangibility and therefore the NFT can only ever be a copy of the “real” thing, the commenters argue. As Levine notes, “It is in its incapacity to produce new life that magic is most profoundly a copy” (1994:117)—and the magic of the NFT process can only ever yield an imitation. Here “magic” and “digital” seem like equivocations. This is a purposeful construction where the complexity of the technology, per Clarke’s “sufficiently advanced technology,” obscures technical processes and seems to come about as if by magic. If this magic moves the physical into the digital, the physical is still figured as original, and the digital as inherently copy.

Yet, the magic of the ashes-to-NFT shown in the six-minute video lies in its financial trick: the image quadrupled in cost in its move from tangible to intangible asset. A $95,000 certified print became a $380,000 NFT.Footnote 23 For the viewers who assert that a magical transformation had literally taken place, the Banksy artwork is not only “transcending the physical form into a virtual space” but even “anticipating the new world” (XION 2021). The burning of the Banksy becomes a transmogrification of both form and value. This kind of magic creates real effects with great consequences, imagining the near future as a struggle “between the virtual and physical worlds” (XION 2021). The NFT is not an object in itself, so much as it is a representation of larger transformations to come.

This understanding of literal transformation, though it presents itself at odds with the conception of NFT-as-copy, is actually at the core of antitheatrical discourse that has long “fear[ed] that representations can actually alter the things they are merely supposed to represent” (Levine Reference Levine1994:108). Even if we are to understand the livestream of art-to-ash—where Burnt Banksy explicitly claims that “removing” the physical print literally and fully encapsulates the process of the “value of the piece [being] moved onto the NFT” (XION 2021)—as only the theatricalization of a different process (minting, on a computer screen and among a distributed network of machines), it is no less effective at rousing anxieties specific to digital systems. If the anxieties at the heart of the antitheatrical pamphlets of Renaissance England are about the stability of the subject, and quite literally in the body—“fears that magic has a constitutive power over the body,” which Levine attributes to gender anxiety (1994:109)—here it is a panic about the public body. It is a spatial anxiety.

Decentralization, Theatricalized

In probing the “place or role of ‘theatricality’ in an age increasingly dominated by media,” Samuel Weber writes of the theatre in spatial terms (2004:97). Theatre and theatricality are integrally tied to a “‘Euclidean’ experience of space-time,” with an emphasis on the “proximity and distance in the situating of bodies,” a spatial understanding that digital media problematizes (99). Lisa Freeman, in Antitheatricality and the Body Public, also takes the gathering of bodies—what Weber calls “groupings” (2004:110)—as primary to understanding what makes theatre, which “has long been distinguished from other representational media […] by its capacity to conduct a kind of sociological survey as it gathers together in a public space, both onstage and in the audience, persons from a cross-section of society to compose […] a site of imaginary affiliation” (Freeman Reference Freeman2019:3). In the emphasis on the body, and the space of gathering those bodies, theatricality in the age of digitality anchors to age-old assumptions. In fact, it is not an overreach to say that NFTs share similar concerns about “proximity and distance” among public groupings within “site[s] of imaginary affiliation.” Far from conceptions of the internet as placeless (see Halstead Reference Halstead2021), blockchain technologies are fundamentally preoccupied with spatial relationships—both the distribution of “nodes” and their ongoing interactions. It seems inadequate to talk about the theatricality of the NFT without considering how that NFT is distributed among a distributed network. Or, more accurately, how that distribution is imagined through decentralization.

On a literal level, blockchain’s decentralization refers to the various nodes of the network—a global system of computers—that validate transactions. They do the minting and the mining, creating a system of checks without a centralized authority. Therefore, as proponents often say, to own cryptocurrency you don’t need a bank and to buy an NFT artwork you don’t need galleries or dealers. If hype can be conceived as modern magic, decentralization is the magic word that underpins blockchain’s social conception. Decentralization makes many promises,Footnote 24 conjuring in imaginations sprawling rhizomes, an aesthetic (and thereby political) proposal that finds comfort in the “proliferation of daydreams: lateral, experimental and situated within […] localities” (Zhexi Zhang Reference Zhang2018:10). A better world can come about only if everything is decentralized, and so “popes, anarchists, economists, hackers, revolutionaries, engineers, and bankers” summon the “occult” power of an undefinable something (Schneider Reference Schneider2019:272). The way that “decentralization” appears as an explanation for any situation and in any context is not much different from the elusive, noncommittal explanation that Burnt Banksy provides.

Ethereum, the blockchain that introduced smart contracts, and thereby made NFTs possible, was built on wanting to be more than financial—it hoped to be everything (Russo Reference Russo2020:xiii). Vitalik Buterin writes that his project is to create “a cryptocurrency network […] for almost any purpose imaginable” (2022:26).Footnote 25 All transactions, any exchange of anything could be made into a smart contract, recorded on the blockchain, immortalized in the immutable digital ledger, to be publicly available forevermore (Buterin Reference Buterin2014). Fantasies of decentralization take root in NFTs as fantasies of totalization—the desire for a universal network, a “technology and discourse that possess a totalizing view of social transformation” (Jutel Reference Jutel2021:4), a “totalizing vision […] applicable to any domain of life” (Schneider Reference Schneider2019:272). While crypto might succeed in seceding from state and financial institutions, the network (the global web of computers that execute transactions and form the basis of blockchain consensus) can’t shed its ambitions as a “control technology” with the potential to “deliver totalizing power […] to the market” (Bassett Reference Bassett2021:19, 20),Footnote 26 remaking everything into smart contract form, immutable and irrefutable. Advocates of this new system imagine nothing short of a new world order. The buyers of Beeple’s $69 million work Everydays: The First 5000 Days in a record-breaking auction, for example, understand their purchase within the context of “experiments and opportunities” that “coalesce into one big world: a Neal Stephenson–like Metaverse, built on virtual reality, virtual currency, and NFTs” (Metapurse 2021).Footnote 27 The result is that blockchain decentralization becomes nothing less than a Gesamtkunstwerk,Footnote 28 continuing a lineage dominated by an “imaginary for the way digital code operates—not only aesthetically but also as worldview” based on a “synthesizing the various elements” and transferring them to the public sphere (Munster Reference Munster2013:160).

As it turns out, this “irresistible power of decentralization” is not despite the lack of clarity, but because of it (Bastiat Reference Bastiat1849:59 in Schneider Reference Schneider2019:268). In this, it aligns with a theatrical opacity. Already, the NFT is abstracted across a global system. The Morons print, aflame, was a particular thing in a particular place, while the NFT reaches across geographic boundaries, simultaneously a mere entry on a ledger, and also a globally significant actor. As the latter, the NFT seems to be present on the stage of everywhere and for all time, implicating everyone—whether participants or not—in its performance. The anxieties expressed in the livestream chat are not so much about the NFT itself, but how it fits into the larger project, the greater ambition. NFTs are part of a larger agenda to remake the system. Burnt Banksy’s explanation about the movement of value is incorrect—the removal of the physical work is not what generates the value of the NFT; value depends on the social agreement that inscribes proof-of-ownership via non-fungible tokens within the political economy of blockchain.

@TheTruth-cz4zc, a particularly concerned Burnt Banksy livestream viewer, extrapolates the implications of the NFT burning:

This inspiration between canceling the physical goods for digital ones, is very dangerous. If this becomes something that takes over, this will make our physical world dull, all the art and excitements moving to digital and virtual realities. (XION 2021)

The virtual world is here conceived of as a copy of the physical reality, but nevertheless one to be feared. @TheTruth-cz4zc is not so much exaggerating as tuning into the wide-ranging promises blockchain technologies were making in the midst of the NFT hype.

Decentralization made it possible, arguably technically, but primarily philosophically, to advocate for a new infrastructure to support relations between people, between bodies. Decentralization becomes a way to encapsulate the complexity of these viewpoints, all fitting neatly under the same umbrella. This configuration—where the whole is necessarily ambiguously situated relative to the individual, and yet the individual is always in relation to the whole, with no center—creates problems for critique.

Materializing Antitheatricality

“Anti-theatricalism always emerges in response to a specific theatre,” write Alan Ackerman and Martin Puchner (2006:2). Digital antitheatricalism, too, is tied to the specifics of the blockchain. The Burnt Banksy NFT, stored on the Ethereum blockchain, is inseparable from the proof-of-work consensus mechanism that created it. The energy-intensive process—while opaque to many participants in the NFT ecosystem (McKenzie Reference McKenzie2023:11)—nevertheless exerts constitutive force on what the NFT is and what it means. Jeffrey Kirkwood’s “From Work to Proof of Work: Meaning and Value after Blockchain” goes so far as to say that proof-of-work, in its reliance on excess, rewrites notions of labor previously rooted in industrial capitalism:

In place of efficiency, it relies on increased work; in place of simplification, it substitutes complexity. This is a situation […] that stands to invert prevailing notions of value in the digital economy. (2022:361)

This new configuration has significant consequences for restructuring our reality; rather than “extraction,” it relies on “invention” through “black box processes [that] often occlude rather than clarify” (362, 361). The process of becoming-NFT mirrors the opacity of theatrical systems that reveal the mechanics without explaining its procedures.

Performance, guided by ephemerality and ephemera, is, too, a form of inefficiency, requiring—and often reveling in—its own excesses. It is in this very quality that artists and theorists often locate its subversive potential. In not subscribing to capitalist imperatives to efficient production, performance can posit alternative relationalities.

Yet, such imaginations don’t seem to be at play for the viewers of the Burnt Banksy burning, nor even now in my attempt to generate a generous reading after the fact. Instead, reinvention carries unexplored risks “whose ills may yet to have been fully realized” (Kirkwood Reference Kirkwood2022:365), and, sensing these dangers, in place of possibility, a strain of antitheatricalism specific to the NFT hype emerges.

While a reactionary impulse, digital antitheatricality proceeds cautiously, heeding Leo Marx’s warning against conceptualizing technology as “an ostensibly discrete entity—one capable of becoming a virtually autonomous, all-encompassing agent of change” ([1997] 2010:564), and rather pays attention to the “changing technics by which [the proof-of-work process] invents its excesses” (Kirkwood Reference Kirkwood2022:380). Antitheatrical impulses, like those of the livestream viewers, allow a perspective that is often missing: an awareness of, and skepticism toward, the apparatus. Digital antitheatricality invites an understanding of the blockchain, and of NFTs, as processes and codes, constructed by people with ideological convictions, financial investments, and personal goals, and built with material hardware. These are virtual realities coded on keyboards, powered by electricity generated on real lands. The magic of the blockchain is not magic at all.

Digital antitheatrical anxiety is the fear of being remade by a technology many do not (yet) understand, a technology that, perhaps, remains opaque on purpose. The NFT is not the image but its proof of ownership. Decentralization is an ideology; its technical apparatus is the distributed network of consensus protocols. The blockchain’s promises are not its own, but that of its developers. Someone scanned the Banksy print on a hardware scanner and uploaded it to a computer. Clicked a mouse, typed on a keyboard. A website triggered processes along a network of various hardware computers, sitting in real spaces, set up by people hoping to make a profit. The theatricality of this infrastructure is anything but pure surface; it is networks of real people and real stuff.

And yet…

Digital antitheatricality, unexpectedly, asks us to think theatrically, imagining the new world not as a “graft” (Hu Reference Hu2015), but in the way Elinor Fuchs describes a play: “another world passing before [us] in time and space” (2004:6). Before we can fully understand and process—not only intellectually, but viscerally—the implications of such a reconfiguration, we need to imagine it. And we can do so in theatrical terms. This is a world in which hype is a modern magic. “Decentralization” is whispered in conference rooms and digital spaces, bringing to life new geographies through its conjuring. Under its spell, this new world remakes conceptions of authenticity. Data is information encoded in code, and code is law (the only law).

Everything is scarce, yet all of it is excess. New world. New rules. New possibilities.