Introduction

In the 2024 U.S. presidential election, 43-46% of Latinos voted for Donald Trump (Sanders Reference Sanders2024). Not only was this an increase from 2020, it is also a disruption from the historical norm, where around two-thirds of Latinos vote Democrat and one-third vote Republican, a division typically explained by national origin group: Mexicans and Puerto Ricans usually vote Democrat, and Cubans usually vote Republican (Alvarez and Garcia Bedolla Reference Alvarez and Bedolla2003; de la Garza and Cortina Reference de la Garza and Cortina2007; DeSipio, de la Garza, and Setzler Reference DeSipio, De la Garza, Setzler, De la Garza and DeSipio1999; Bowler and Segura Reference Bowler and Segura2011; Uhlaner and Garcia Reference Uhlaner, Garcia, Segura and Shaun2005). Further, at the precinct level, some of Trump’s biggest gains were in heavily Latino counties that have supported Democrats for decades (Datar et al. Reference Datar, Lemonides, Marcus, Murrey, Singer and Zhang2025), following a trend that began in 2020 (Fraga, Velez, and West Reference Fraga, Velez and West2025) and suggests a more durable Latino partisan realignment than what some have downplayed (Dominguez-Villegas et al. Reference Dominguez-Villegas, Gonzalez, Gutierrez, Hernández, Herndon, Oaxaca, Rios, Roman, Rush and Vera2021; Sanchez and Barreto Reference Sanchez and Barreto2016; Sanchez and Gomez-Aguinaga Reference Sanchez and Gomez-Aguinaga2017). In short, what the results of the 2024 presidential election highlight is that, like some political scientists have previously argued (Cisneros Reference Cisneros2016; Hajnal and Lee Reference Hajnal and Lee2011), Latino partisanship cannot be fully explained by traditional theories of party identification. Although analyzing Latino voting behavior towards Trump is informative, Latino Republicanism more broadly remains relatively understudied (exceptions include Alvarez and Casellas Reference Alvarez and Casellas2025; Basler Reference Basler2008; Cadava Reference Cadava2020); there is little understanding of the political reconciliations made by Latinos currently engaging in Republican politics (Cadena Reference Cadena2023), and much of this scholarship lacks a rigorous examination of gender in its analysis.

I argue that making sense of the 2024 election and its implications necessitates an examination of Latino Republicanism beyond what can be accounted for by voting behavior. The results of the 2024 election are less surprising, for example, considering that Latinos have been increasingly willing to engage with the GOP since 2016, including running for office. In fact, the 2022 midterms saw a record number of Latinos running for Congressional office under the Republican ticket, with the sharpest increase among Latinas, to the point some news outlets titled 2022 the “Year of the Latina Republican” (Zhou Reference Zhou2022). The increase in Latina Republican candidates is of particular interest considering Latinas are consistently more ideologically liberal than Latino men (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2014; Bejarano et al. Reference Bejarano, Manzano and Montoya2011; Donato and Perez Reference Donato and Perez2016), are less likely to identify with the Republican Party (Brischetto and de la Garza Reference Brischetto and de la Garza1983; Montoya, Hardy-Fanta, and Garcia Reference Montoya, Hardy-Fanta and Garcia2000), and indeed, Latina Republicans have been so few that scholarship on Latina candidates has largely focused on Latina Democrats (Gutierrez, Melendez, and Noyola Reference Gutiérrez, Meléndez and Noyola2007; Navarro et al. Reference Navarro, Jaramillo, Garcia, Martinez-Ebers and Coronado2008).

How can Latina Republican candidates reconcile appeals to Latinos, who largely support comprehensive immigration reform (Latino Decisions 2014; Krogstad and Lopez Reference Krogstad and Lopez2021) with a Republican platform that associates migrants with criminality and advocates for penal immigration policy? What role, if any, do their identities as Latinas play in their ability to campaign for themselves, their party, and represent their Latino constituents? Utilizing four border-district Texan candidates as case studies, this paper examines how Latina Republican candidates in the U.S. frame themselves as embodying and representing the “real Latino electorate,” who they claim have been ignored by the U.S. political arena. Through an in-depth analysis of their campaigns — including content analyses of their public interviews, speeches, advertisements, websites, newspaper coverage, and social media presences — I find that these candidates utilize an intersectional vision of Latinidad to grant themselves the political legitimacy and rhetorical flexibility to support comprehensive immigration reform and utilize the Latino threat narrative (Chavez Reference Chavez2008) to justify punitive border policies. These candidates’ race-gender-consciousness articulates Latinidad as an explicitly brown identity, highlights Latino immigrant women and children as victims, Latino immigrant men as criminals, and themselves as authorities on immigration. This further allows these candidates to express political anger, which has been generally denied to women of color in the GOP (Sparks Reference Sparks2015; Wineinger Reference Wineinger2021) and make a pointed critique towards the political parties: these candidates’ rhetoric is fundamentally tied to a claim that Latinos have become a captured group. This research contributes an intersectional, gendered analysis to the growing literature on Latino Republicans, problematizes scholarship on Latino identity, candidates, conservative women, and illuminates some of the ongoing discussions Latinos are having about the political parties and our place in American politics. This research suggests that, despite histories of exclusion, the political spaciousness for Latinas engaging in Republican politics is growing, and anti-immigrant sentiment is not the only way the most politically engaged Latinos can seek political empowerment within the political parties.

Latina/o Partisanship, Candidates, and Identity in the GOP

In the past few years, there has been a growing literature on Latinos’ identification with Republicanism (Cadena Reference Cadena2023; Cisneros Reference Cisneros2016) with a particular focus placed on examining Latinos who have voted for Donald Trump (Dominguez-Villegas et al. Reference Dominguez-Villegas, Gonzalez, Gutierrez, Hernández, Herndon, Oaxaca, Rios, Roman, Rush and Vera2021; Fraga, Velez, and West Reference Fraga, Velez and West2025; Hickel, Oskooii, and Collingwood Reference Hickel, Oskoii and Collingwood2024). However, there is far more limited research examining Latinos’ experiences navigating Republican circles and the party infrastructure more broadly (Cadava, Reference Cadava2020) such as through running for office (Alvarez and Casellas Reference Alvarez and Casellas2025), and overall, Latino Republicans remain relatively understudied. Within this scholarship is the finding that, despite a long history of pro-immigrant movements (Haney Lopez Reference Haney and Ian2004; Zepeda-Millan Reference Zepeda-Millán2017) there is an increasing segment of Latinos, including working-class Latinos and Latinos in areas with large immigrant populations (Fraga, Velez, and West Reference Fraga, Velez and West2025), who are anti-immigrant and voting for Trump (Hickel and Bredbenner Reference Hickel and Bredbenner2020; Hickel, Oskoii, and Collingwood Reference Hickel, Oskoii and Collingwood2024) and may even be so to embrace political whiteness (Basler Reference Basler2008). Increasing anti-immigrant segment among Latinos may even explain why some majority-Latino districts have shifted in support for Trump in recent elections. However, insight from scholarship on Black Republicans, Republican women, and Latinas suggests that for the Latinos who are most entrenched in Republican party politics, there may be a more nuanced dynamic at play.

Despite the GOP’s attempts to reject identity politics in their political rhetoric (Grossmann and Hopkins Reference Grossmann and Hopkins2016), identity nevertheless plays a significant role for Republicans of color. Fields (Reference Fields2016) finds that for Black Republicans, conservatism is not inherently tied to the denial of Black identity. Instead, some Black Republicans’ self-identity and their articulated views of Black people are “a defining feature of their experiences within the Republican party” (26). Similarly, Cadava (Reference Cadava2020) finds that one of the most critical aspects of Latino Republican politics has been “their opposition to discrimination against immigrants and Hispanics in general” (68) and Latino Republicans do not necessarily emphasize an association to whiteness but rather an ideological disassociation from certain co-ethnics (Cadena Reference Cadena2023; Hickel, Oskoii, and Collingwood Reference Hickel, Oskoii and Collingwood2024). Furthermore, although Black and Latino Republicans have historically received institutional support from segments of the party caucus, many of their recommendations on appealing to their respective groups have been largely ignored, leaving both Black and Latino Republicans frustrated with Republican leadership (Cadava Reference Cadava2020; Farrington Reference Farrington2016; Wright Rigeur Reference Wright Rigeur2016). In other words, this scholarship suggests an embrace of whiteness among Latino Republicans is not necessarily the principal mode for reconciling their ethnic- and partisan-identities.

This matter of identity and party navigation is further problematized by scholarship on Republican women. Similarly to Latinas, Republican women are on average more moderate than their male co-partisans (Barnes and Cassese Reference Barnes and Cassese2017), which results in fewer Republican women choosing to run for office (Carroll and Sanbonmatsu Reference Carroll and Sanbonmatsu2013; Thomsen Reference Thomsen2015; Reference Thomsen2017). As a result of this self-removal from candidacy, Republican women Congressional candidates tend to hold further right-wing ideological stances than those typically held by women in their party, becoming “ideologically indistinguishable” from their male Republican counterparts (Frederick Reference Frederick2009).Footnote 1 However, this does not mean Republican women are powerless to pursue more moderate policies. Republican women strategically navigate their roles as party messengers to elevate their voices and advocate for their interests, which may not always be in step with party leadership (Wineinger Reference Wineinger2022). In this way, the candidates in this study would appear to align with previous research on conservative women.

However, as Latinas advocating for far-right policies, these candidates problematize how conservative women of color navigate the party. While some white Republican women can utilize anger in their campaigning through the invocation of “mama grizzlies” imagery (Sparks Reference Sparks2015), and Tea Party women activists have foreground motherhood in their rhetorical appeals for far-right policies (Deckman Reference Deckman2016), conservative women of color have not been granted those same liberties. Unlike white conservative women, their anger is “very rarely legible as political anger worthy of sustained attention” and has not achieved the careful acceptance conservative men of color have attained within the party (Sparks Reference Sparks2015, 45; Wineinger Reference Wineinger2021). In fact, previous attempts to analyze Republicans of color have demonstrated how such actors must rely on careful adherence to traditional gender roles, almost never going as far as their white counterparts and even reshaping the narratives of their communities in their own conservative image to fit the party narrative (Dawson Reference Dawson2001; Dillard Reference Dillard2002; Wineinger Reference Wineinger2021).

Yet not only can these candidates utilize political anger, but their rhetoric is fundamentally rooted in an explicit articulation of Latinidad, which is a significant departure from Republican Party culture. The Republican Party’s rejection of identity politics has meant even Republican candidates from minority groups have avoided explicit group-based appeals or courting specific social groups (Grossmann and Hopkins Reference Grossmann and Hopkins2016). This culture is so strong that advocacy groups who seek to increase women’s representation in political office have significantly less sway on Republican elites or Republican donors compared to Democrats — regardless of Republican elites’ personal views on gender (Crowder-Meyer and Cooperman Reference Crowder-Meyer and Cooperman2018). Indeed, the articulation of Latinidad in political discourse has been almost exclusively driven by Latino Democrats. Drawing upon a history of progressive Chicano and Puerto Rican movements, Latino elites have strategically presented Latinos as a “politically cohesive national minority group” to pursue liberal policy reform, though their efforts have been interrupted by the reality that Latinos in office are not always ideologically aligned (Beltran Reference Beltrán2010, 100–101). Latino candidates have also tended to use what Barreto (Reference Barreto2010) titles a “nuestra comunidad” campaign approach, where they highlight their Latino ethnicity, make claims on shared ethnic — and often geographic — space, and argue they are “either from la comunidad” or were “part of la comunidad” (63).Footnote 2 The candidates in this study employ similar tactics to articulate their vision of Latinidad, which demonstrates the magnitude of the change they present to the political norm of appropriate Republican candidate behavior and highlights the diffuse, political construction of Latinidad.

I agree with Beltran (Reference Beltrán2010) that Latinidad must be considered as an ongoing political project more than a static ethnic group. Given the gender divides in Latino political engagement, I further argue that examinations of Latino Republicanism would greatly benefit from incorporating gender analysis. In addition to being more ideologically liberal (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2013; Reference Bejarano2014; Bejarano et al. Reference Bejarano, Manzano and Montoya2011) and politically participating more than Latino men (Garcia Bedolla Reference Garcia Bedolla2005), Latinas are also significantly less likely to identify as Republicans than their male counterparts (Brischetto and de la Garza Reference Brischetto and de la Garza1983; Montoya, Hardy-Fanta, and Garcia Reference Montoya, Hardy-Fanta and Garcia2000), and Latina immigrants, who are more ideologically conservative than their male counterparts upon arrival to the U.S. (Donato and Perez Reference Donato and Perez2016) and might therefore be included in groups of Latino immigrants who voted for Trump (Fraga, Velez and West Reference Fraga, Velez and West2025) are more likely to prioritize U.S. electoral politics than Latino men (Jones-Correa Reference Jones-Correa1998). This scholarship suggests Latina Republicans may have fundamentally different reconciliations of Latinidad and their partisan identities than their male counterparts. In fact, ignoring the role of gender within an already understudied scholarship such as Latino Republicanism may even risk obfuscating just as much as it may enlighten. Therefore, although gender politics is not synonymous with women’s politics, I argue that the literature’s dearth of knowledge regarding Latina Republicans demonstrates that one of the most pressing first steps in incorporating gender analysis into this scholarship is to examine Latina Republicans.

I argue the candidates in this study outline an intersectional, race-gender-conscious politic, which 1) articulates Latinidad as a distinctly brown, racial identity, 2) utilizes a gendered framing of Latino immigrant women and children as victims, Latino immigrant men as criminals, and themselves as unique authorities on immigration given their status as border patrol wives, and 3) grants them the legitimacy as Latinas to express political anger and navigate politically disadvantageous terrain. This research thus helps problematize scholarship of Latino identity, contributes to scholarship on Republican women and Latina candidates, illuminates dynamics within Latino Republican circles, and highlights the intellectual necessity of incorporating gender analysis to study Latino Republicans in the United States. To draw out the full nuances of this phenomenon, a case study approach is both methodologically appropriate and essential.

Data and Research Design

The candidates in this study were identified through a 2022 report from the UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Institute. This list was supplemented with U.S. Census data to narrow down the case studies to only candidates who ran in supermajority-Latino districts. Of the 16 Latina Republican House Candidates who ran in 2022, only five met these criteria. Of those five, four were concentrated in different border districts in Texas, and it is those four Texan candidates whom I analyze in this study.Footnote 3 These candidates are: Irene Armendariz-Jackson (TX-16), Cassy Garcia (TX-28), former Congresswoman Mayra Flores (TX-34), and current Congresswoman Monica de la Cruz (TX-15).Footnote 4

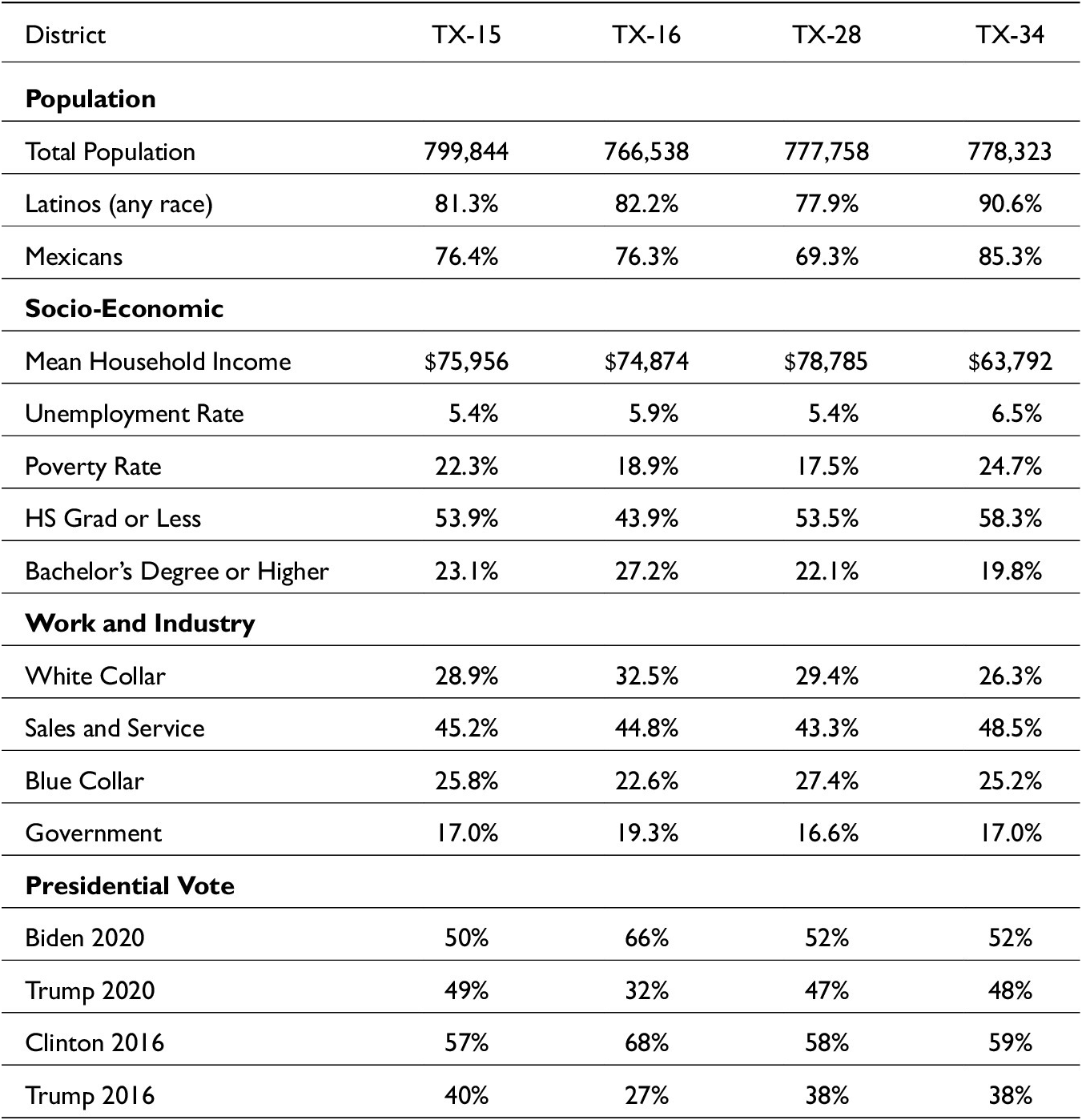

The cases in this study fall under what Seawright and Gerring (Reference Seawright and Gerring2008) classify as most similar cases. As demonstrated by Table 1, the four districts included in this study share significant overlap in terms of region, Latino — and specifically Mexican — composition, educational attainment, economic status, and even presidential vote history.Footnote 5

Table 1. District demographics

All four candidates are women of Mexican descent running for office in super-majority Latino districts in Texas along the U.S.-Mexico border. The percentage of Latinos in their districts ranges from 77.9 to 90.6% and, prior to the 2022 midterms, had been represented by Democrats for over fifty years. Additionally, three of the districts in the case studies — the districts where candidates Garcia, Flores, and de la Cruz ran — are direct neighbors. In other words, the largest difference between the case studies is not the district, but the candidate.

One might argue that similarity across case studies may reflect selection bias, thereby limiting this project’s theoretical contributions (Geddes Reference Geddes1990; King, Keohane, and Verba Reference King, Keohane and Verba2021). However, I contend that the similarity across the case studies is to this paper’s advantage. The border is a lightning rod for all discourse on immigration and Latino politics, a feat further complemented by the candidates’ identities as women of Mexican heritage. Given Mexican’s status as the face of undocumented immigration (Chavez Reference Chavez2008; De Genova Reference De Genova2004), the border as a site of such contention, and these districts’ histories as Democratic strongholds, the ways these candidates navigate this political terrain reflect a nuance that may otherwise be absent in alternate case studies. Given the numerical scarcity of Latina Republican candidates compared to Latino Republican men, the wide berth of tools and data sources utilized by a case study approach is particularly apt for producing a holistic view of these candidates’ rhetorical strategies (Flick Reference Flick2009; Flyvberg Reference Flyvberg, Denzin and Lincoln2011). In short, the selection of candidates Garcia, Flores, de la Cruz, and Armendariz-Jackson as the case studies for this project is both methodologically justified and methodologically necessary to examine this paper’s questions.

To analyze these four cases, this study examines 76 public interviews of the candidates from various English and Spanish news sites, radio stations, and podcasts from November 2020 to November 2022.Footnote 6 These interviews are supplemented with candidate speeches and statements at rallies, marches, and other public events posted across their social media and campaign-affiliated sites. I also collected and analyzed bilingual newspaper articles, opinion pieces penned by the candidates, the candidates’ campaign websites, campaign ads, and their social media presences across Facebook, Instagram, X, YouTube, and TikTok.Footnote 7 This combination of highly scripted and casual candidate materials thus provides a holistic analysis of how these candidates frame themselves, their appeals, and the “real Latino electorate” they claim to represent.

Who Is the “Real Latino Electorate”?

At the core of these candidates’ appeals is the political construction of Latinidad and what they call the “real Latino electorate,” whom they argue have been misunderstood by the U.S. political arena. Garcia claims “[Latinos] are conservatives! We are conservatives on education, social issues, we are pro-gun and pro-life. Hispanics want lower taxes, religious freedom, and school choice” (Fox News, 6/19/22). “Real Latinos” are entrepreneurial spirits who care about economic stability, social mobility, and achieving the American Dream. They care about “how much gas is, how much food is, and the shortage on medication” (Armendariz-Jackson, ABC7, 10/22/22). These values, the candidates allege, are deeply rooted in Latino culture. According to these candidates,

[Conservative] is who we are, that is who we have always been. People tell me, ‘Mayra, why are you a Republican, weren’t you born in Mexico?’ It is because I was born in Mexico that I am Republican, because I was raised with strong conservative values. (Flores, Fox News, 6/22/22)

These candidates also construct their version of Latinidad by articulating what “real Latinos” are allegedly not. Several of the candidates utilize Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who they claim is a stand-in for the future of the Democratic Party, as a proverbial litmus test. In an interview with Fox News, Garcia states, “Do not AOC our South Texas or our Texas. We are not a progressive socialist community, our party is all about faith, family, and freedom” (3/14/22).Footnote 8 In a separate interview, she claims she “can’t wait to have a security clearing with AOC” and vet the “radical leftist candidate” (Heritage Action for America, 9/28/22). In an opinion piece for Fox News, de la Cruz writes, “The Democrats are the party of extremists, like AOC, who demand ideological uniformity” (11/2/22). Rep. Ocasio-Cortez’s support of policies such as Medicare for All and the Green New Deal is characterized by the candidates in this study as socialist handouts that prioritize white coastal elites. Flores states: “The Democratic party has abandoned the Hispanic community. They’re focused on white liberals, they’re not focused on the Hispanic community, they can care less! They are just not representing our values” (Fox News, 6/23/22). Real Latinos are not preoccupied with “becoming woke” or accepting “cultural radicalism” via the use of pronouns or the gender-neutral term “Latinx” as prioritized by Democrats (de la Cruz, Fox News, 10/5/22). The candidates argue these views are supported by Latinos’ ties to immigration.

What the Democrats don’t get is that we have lots of immigrants – recent immigrants, legal immigrants, and first- [and] second-generation [Americans] – that fled countries where there is socialism: Where they are persecuted, where they don’t have their gun rights, where they don’t have their freedom of speech [or] freedom of religion rights. These things that the Democrats are putting out there – promoting socialism, taking away our religious freedoms, putting that second amendment at risk – those things just simply do not reflect the Hispanic community and what we believe in. (de la Cruz, Hispanic Republicans of Texas, 9/30/21)

In other words, the “real Latinos” residing in these districts are “actually Republican, they just don’t know it” (Armendariz-Jackson, Real American, 7/6/21). Latinos’ loyalty to Democrats is not due to ideological alignment, but a matter of habit. Armendariz-Jackson claims

Being Democrat in the border cities is like a religion. ‘¡Soy Demócrata!’ I get people that call me and can’t stand the incumbent. They voted for me in 2020 and are gonna vote for me again [in 2022]. ‘¡Pero soy Demócrata!’ Ándale pues, ‘soy Demócrata’ (Hispanic Republicans of Texas, 8/31/21).

These candidates’ reconceptualization of Latinidad is also fundamentally tied to their own self-characterization of “real Latina” representatives and solutions to political misrepresentation.

“Real Latina Representatives”

Unlike other Republican candidates who reject the use of identity politics in their campaigns (Grossmann and Hopkins Reference Grossmann and Hopkins2016), these candidates utilize their conceptualization of Latinidad to characterize themselves as the “real Latinas” who can represent their constituencies.Footnote 9 A key aspect of their self-framing as “real Latina” candidates is an attachment to their Mexican heritage and the immigrant experience. Garcia and de la Cruz are 3rd generation Americans whose grandparents immigrated from Mexico. Both appeal to their Mexican heritage in their speeches, public appearances, social media posts, and campaign websites. In her victory speech, de la Cruz compares herself and her constituency to Mexican cultural icons Luis Miguel and Selena Quintanilla. On their Instagram and Twitter pages, both make posts about Dia de los Muertos, Hispanic Heritage Month, and emphasize their grandparent’s migration histories on their campaign websites. Their grandparent’s history of migrating to the U.S. and serving in the military, they claim, has fundamentally shaped their values. This love of Mexican culture is so present that on her campaign website, de la Cruz states she attended La Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México to further her Spanish language studies and get closer to her heritage. On the Texas Latino Conservatives podcast, Garcia details being raised by a tough Latina mom, stating “[Latina] mothers are the strongholds of the family” who will readily reach for “la chancla” (the slipper) as the host added, or “the belt” when it comes time to discipline their children (6/22/22). The immigrant experience may be a generation removed from theirs, but their ties to their families and their heritage are living parts of their connection to Latinidad.

Flores and Armendariz-Jackson have more recent immigration histories and living ties to Mexico which they utilize in their campaigns. Armendariz-Jackson is a 2nd generation American. Although she was born in the U.S., her childhood was spent in Mexico. She recounts a story of her father coming home from work to find her sister and her “hiding under the covers because we had lost the gas in our home – because that’s what happens in Mexico.” She says it was at that point her dad said, “What are we doing here? We will have a better life in the United States” (Fox News, 11/9/22). Flores is a 1st generation American, and after winning a special election on June 14, 2022, became the first Mexican-born Congresswoman in U.S. history, a point which was highlighted in her campaign website, interviews, and social media platforms. She frequently references growing up in Tamaulipas and bringing her children to visit their great-grandparents in Mexico to maintain that living connection to their heritage (Instagram, 8/9/22). Similarly, Armendariz-Jackson states her parents still attend church in Ciudad Juarez. To these candidates, and allegedly many of the Latinos in their districts, the border and its enforcement are not an oppressive structure, but a part of daily life. In fact, many immigration enforcement agents are members of their families — something which is further elaborated later in this article.

These candidates’ attachment to their vision of Latinidad shapes every other policy position, including the economy, inflation, and healthcare, which they highlight has been particularly devastating for Latinos. “Four out of the nine counties in my community do not even have doctors,” Garcia writes, adding, “Women should never have to go to Mexico for OGBYN appointments or mammograms” (10/31/22). de la Cruz points to how “the average income for Hispanic families is $54,000 per year. Hispanics tend to have larger families which means more mouths to feed and less money to do that” especially with the surge in price for gas and groceries (Binder 2022). Regarding abortion, Flores argues:

* If we have so much pride in our community, in our people, we should defend life. They only put these abortion clinics in our communities, they don’t put them in rich people’s communities, as if their life was worth more. They don’t put the clinics in majority-white areas, they put them in our community … as if they want to get rid of us. (24 Horas, 7/6/22)Footnote 10

Importantly, these candidate’s conceptualization and embodiment of Latinidad is not a white conceptualization. In addition to Flores’ above distinction between majority-white and majority-Latino communities, Armendariz-Jackson says:

How can Beto O’Rourke come in and say he can represent people of color, Hispanics, especially Mexican people that are currently opposed to [his] stances that go against our values? … The Left is constantly sending the message of “mi gente, mi pueblo,” telling people, telling Hispanics “You’re brown? You’re a Democrat! Because every Republican is old white rich racist males.” Do I look like that? (Real American, 7/6/21)

Thus, unlike arguments regarding Latino Republican aspirations towards whiteness (Basler Reference Basler2008) or some circles of Black conservative politics rooted in colorblindness (Dawson Reference Dawson2001), these candidates openly articulate Latinidad as a brown, racial identity.Footnote 11 Like “race-conscious” Black conservatives, these candidates “fram[e] conservative values as the ones best suited to create solutions” for the larger group (Fields Reference Fields2016, 118).

However, this framing of Latinidad is also gender-conscious. These candidates frame Latinidad and their roles as “real Latinas” through the lens of what are traditionally understood as “women’s issues,” such as when Garcia emphasizes the role of mothers in Latino households and Latina’s access to mammograms, or when Flores and Armendariz Jackson discuss abortion. These candidates highlight these “Latina’s issues” and claim conservative values are best equipped to resolve them, thereby granting themselves the political legitimacy necessary to address them (Bauer Reference Bauer2020; Dolan Reference Dolan2005; Reference Dolan2014; King and Matland Reference King and Matland2003). Yet this is only a small segment of these candidate’s gendered frames. Strikingly, these candidates’ race-gender-consciousness has a complex impact on how they conceptualize immigration and the border, allowing them to reconcile appeals for both comprehensive reform and punitive immigration stances. It is not just a border crisis. It is a humanitarian border crisis.

The Humanitarian Border Crisis

In announcing his bid for the 2016 presidential election, Donald Trump received backlash for his description of Mexican migrants as drug addicts, criminals, and rapists (TIME Magazine, 2015). This is not a novel characterization. Coined by Leo Chavez (Reference Chavez2008), the “Latino threat narrative” presents Latin American immigrants as threats to the nation, utilizing associations with criminality and terms such as “waves” and “invasions” of migrants. This narrative utilized against Latino immigrants — and in some cases, all Latinos, irrespective of citizenship status — strips Latinos’ humanity and transforms us into political scapegoats for societal ills. Yet unlike other far-right co-partisans, these candidates’ race-gender-consciousness allows them to problematize narratives of the border by explicitly framing immigration as a humanitarian crisis. According to this framework, migrants are not simply potential threats but victims of horrific abuse. de la Cruz says,

[Democrats have] taken a crisis situation and made it into a catastrophe. Not only on a humanitarian basis – by taking the most vulnerable, young women and children and infants, [and] putting them in the hands of cartels for human trafficking, sex trafficking … Young ladies are coming in who have been raped and sexually assaulted several times. We hear their stories from the border patrol agents, we actually see on the local basis children and infants being abused … It is absolutely horrific. (Hispanic Republicans of Texas, 9/30/21)

Garcia describes her constituents witnessing widespread violence towards migrants and migrant death, stating:

Biden wants people to think his border policies are compassionate, but there’s nothing compassionate about open borders … We’re seeing migrants [who are] suffocating to death. They’re being kidnapped by drug cartels and migrant women and children are being raped (Newsmax, 9/23/22).

Similarly to both Garcia and de la Cruz, Flores also emphasizes the sexual and physical assault suffered by migrants. These candidates want to improve the legal process because, they argue, it is not the fault of the migrant they have been abused in their pursuit of entering the U.S., but rather the fault of failed immigration policies.

* There hasn’t been a woman that hasn’t told me she’s been abused. I do not wish that on anyone. I do not blame the immigrant, I blame this government because this government is the one telling them … with its laws to come, to put themselves at risk, knowing that the criminal organizations have taken ownership of the border. (Flores, El Show de Piolin, 9/29/22)

Armendariz-Jackson is the least sympathetic to undocumented immigration among the candidates in this study. However, even she is willing to condemn violence against migrants, stating that the immigration system does not go far enough to protect immigrants escaping persecution. In her view, “illegal immigration harms everybody, including the illegal immigrant” and after recounting the harrowing experience of an undocumented family who attend her sister’s church, she concludes, “they didn’t call the police because they were illegally here. This is what the Democrat agenda does. It victimizes people over and over again” (Hispanic Republicans of Texas, 8/31/22).

Like in the previous section, these articulations of humanitarian victims are gender-conscious. In emphasizing sexual abuse, which is already understood in political discourse as gendered violence towards women (Berns Reference Berns2001),Footnote 12 and specifying the victims are “young ladies,” and “women and children,” they transform immigration discourse in a way distinct from other far-right co-partisans. The term “victim” of humanitarian abuse becomes synonymous with “woman” and “child,” thereby removing from their political rhetoric the reality that migrant men also experience sexual abuse (Foster-Frau and Herrero Reference Foster-Frau and Herrero2025; Human Rights Watch Reference Watch2021). Within this is also the conflation of migrant men with criminals. “Women and children” are contrasted with cartels and gangs, and it is thus Latino migrant men who exploit migrant women. These candidates’ race-gender-consciousness transforms immigration into a “women’s issue,” thereby granting them leverage to discuss immigration and national security, which are typically understood as “masculine” issues within an already “masculine” political party, without the backlash that discussing such issues as women could potentially inspire (Bauer Reference Bauer2020; Dolan Reference Dolan2005; King and Matland Reference King and Matland2003; Winter Reference Winter2010).

Specifically, this gendered rhetoric grants these candidates the legitimacy as “real Latinas” to, unlike other Republicans, advocate for very similar visions of seemingly progressive immigration reform. For example, all the candidates in this study advocate for increasing pathways towards residency for new immigrants and passing the DREAM Act. Garcia says:

We need to transform [and] streamline the legal process. I can’t wait to serve in Congress so we can work on those reforms, on immigration so people who want to come to this country the legal way can do so, and it won’t have to take years for them to become a citizen (Newsmax 9/23/22).

Continuing this emphasis on the backlog of immigration claims and pointing to specific non-militarization policies as important parts of the solution, Flores states: “It takes 15-20 years to be able to come to the United States … We need to improve the legal process. We need to hire more immigration judges, more asylum officers so we can process these claims” (Fox News, 9/27/22). These candidates support DACA recipients who “came at no fault of their own” and “deserve a legislative solution” (de la Cruz, CBS, 11/9/22), which would provide a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children. Armendariz-Jackson even criticizes the Democratic Party for not passing DACA, stating, “Why did Pelosi and Schumer refuse to discuss DACA with Trump? What reform have the Democrats proposed, don’t they have the WH, the House, and the Senate?” (Twitter, 9/22/22). In one of the singular points of deviation, Flores goes a step further than the other candidates and advocates providing a path to citizenship for all undocumented immigrants in the U.S.

* And once [DACA] passes, then we can think about the people who have, like you say, who have been here 20-30 years working, paying taxes, who have a clean record. I am ready to speak with both parties, but I think the first priority should be DACA and securing the border. (El Show de Piolín 9/29/22).

These candidates’ race-gender-consciousness thereby problematizes immigration narratives in a way noticeably distinct from other Republicans, and doing so even on platforms such as Newsmax, Breitbart, and Fox News, whose audiences are arguably the least sympathetic to immigrants.

One could argue these policy stances are to be expected if they want to compete in historically Democratic and supermajority-Latino districts. After all, public opinion suggests many Latinos want comprehensive immigration reform like what these candidates outline (Krogstad, Manuel, and Lopez Reference Krogstad and Lopez2021; Latino Decisions 2014). However, these sympathetic narratives are not the end of the political story these candidates present. Although they critique migrant suffering and advocate for immigration reform to prevent continued harm, these candidates simultaneously champion border militarization and readily engage in the same Latino threat narrative employed by other members of their party. How can this be so? The answer is tied to these candidates’ conceptualization of Latinidad, which lets them highlight CBP agents as key members of the Latino community they seek to represent.

Race-Gender-Conscious Visions of Immigration Enforcement

Contradictory on its face to the sympathetic rhetoric extended to undocumented immigrants, these candidates employ similar anti-immigrant rhetoric as other far-right Republicans. To put it succinctly, these candidates’ view is: “We’re all for immigrants. But what’s happening right now is clearly an invasion” (Flores, Newsmax, 6/16/22). Although these candidates problematize immigration narratives, they do not view all Latino immigrants as community members. Comparing her own parent’s immigration history, Armendariz-Jackson says, “First of all, let’s call them what they are, they’re illegal aliens, they’re not immigrants. My parents are immigrants, they came into this country legally and they’re appalled they’re calling these people immigrants” (Newsmax, 4/7/22). These candidates also critique the end of Title 42, a Trump-era policy which allows the U.S. to deny migrants their legal right to request asylum by deporting them to Mexico without formal processing. According to Garcia, Title 42s termination “will be catastrophic for all the Hispanic communities that are already dealing with the Biden border crisis firsthand” (Garcia, Fox News, 4/5/22), adding, “it’s not fair to the Hispanic communities that are having to bear the burden of using taxpayer dollars to bus these migrants out of the area” (Heritage Action for America, 9/28/22). Even migrant death is recognized through its impact on U.S. citizens. In a visit to the Rio Grande Valley, de la Cruz states:

The people responsible for picking up these bodies [of deceased migrants] are the landowners, or the county or city. They’re footing the bill and the federal government is not helping them. It’s costing local taxpayer’s money. This is a big burden to shoulder … Our Border Patrol men and women have been abandoned by the Biden administration. (Facebook Live, 8/30/22)

On its face, these stances seem inherently contradictory. How can these candidates simultaneously condemn migrant suffering and advocate for seemingly progressive immigration policies while also championing border militarization and dismissing migrants as invaders?

These candidates can employ the Latino threat narrative when discussing penal immigration policies, not despite their embrace of Latinidad, but precisely because of it. The same race-gender-consciousness which allows them to advocate for immigration reform also allows them to push for draconian border policies. Notably, these candidates do not reference women or children when describing the U.S.’s alleged invasion. Rather, the cartels, gangs, and “invading force” of “illegal aliens” is composed of migrant men who harm migrant women and children. Their ability to center immigration enforcement in their campaigns and circumvent the limitations placed on women politicians who are perceived as less competent on “masculine” issues (Bauer Reference Bauer2020; Dolan Reference Dolan2005; King and Matland Reference King and Matland2003) and gain legitimacy within a “masculine” political party (Winter Reference Winter2010) is fundamentally tied to their self-characterization as “real Latina” candidates. They can navigate this politically disadvantageous terrain because the communities they claim to represent not only constitute Latino U.S. citizens and Latina migrants, but also the CBP agents they married.

Garcia, Flores, and Armendariz-Jackson are married to CBP agents. Their marriage to immigration enforcement is something they claim to be foundational for how they frame and understand immigration. In a campaign ad, Flores states,

Democrats say border security is racist. That is a lie. Border security is compassionate, humane, and necessary. It’s simply common sense. My husband is a border patrol agent. I see the burden that is placed on our border patrol by irrational policies introduced by Democrats. (2/17/22).

Garcia takes her husband on the campaign trail to meet members in her district, claiming her experiences with her husband and his colleagues grants her intimate knowledge about the difficulties agents face, how it “takes a toll on the agent and their families as well” because “they didn’t sign up to do this. They didn’t sign up to allow people to come into our country” or address abused women at the border (Heritage Action for America, 9/28/22). This insight gained from being a border patrol wife, Garcia claims, is why she is endorsed by the National Border Patrol Council, which she underscores in most interviews and campaign ads. Like Flores, Armendariz-Jackson critiques the characterization of CBP agents as oppressors. “Growing up on the border you would always hear the jokes of ‘Ay viene la migra,’ and that meant something bad. Like Border Patrol was gonna come and deport us all.” She claims it was only after her marriage that her family “saw the humanity of the Border Patrol agents” (Fox News, 11/9/22). These candidates’ ties to CBP cannot be divorced from their campaigns. On Fox News, Flores states, “a lot of people tell me to not take [the news coverage] personal, but how can I not? Our border patrol agents, just like my husband, they’re our family! And every attack against them is very personal. It’s against our familia” (6/16/22). Therefore, like Republican congresswomen who utilize their husband’s military service to grant themselves legitimacy and override their perceived lack of competence in traditionally “masculine” issues like national security (Bauer Reference Bauer2020; Dolan 2005; Wineinger Reference Wineinger2022), these candidates utilize their status as border patrol wives to further cast themselves as unique authorities on immigration.

It is not only a matter of their spouses being CBP agents, but also these candidate’s inclusion of immigration enforcement agents as key members of their communities. “We house the largest border patrol sector in the entire nation. Border Patrol agents – they’re our friends, they’re our families, they’re our neighbors,” de la Cruz states, succinctly demonstrating this inclusion of immigration enforcement is not limited to agents directly related to them (CBS, 11/9/22). There is a high concentration of Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) Field Offices within these districts — there are three ICE-ERO Field Offices in El Paso, Harlingen, and San Antonio and two CBP-ERO Field Offices in El Paso and Laredo — which suggests immigration enforcement agents make up a notable proportion of these districts’ population. However, what is particularly notable about these candidates’ support of immigration enforcement is how they directly tie these agents to the Latino community. The vilification of immigration enforcement is particularly heinous because, as these candidates point out, half of all CBP agents are Latino (U.S. Office of Personnel Management 2018). These candidates’ race-gender-consciousness thus not only presents migrant women as victims and migrant men as criminals, but it also highlights immigration enforcement as a key issue of the Latino community they seek to represent.

This support of CBP agents makes perfect sense when paired with these candidates’ conceptualization of Latinidad. If “real Latinos” are conservative by nature and primarily concerned with economics rather than virtue signaling, it makes sense why Latino CBP agents would be revered. Cortez (Reference Cortez2021) finds that Latino ICE agents claim their employment is not borne from self-hatred, but in pursuit of economic stability, which is the exact kind of “hard work” ethic these candidates reference as a central tenet of Latinidad. In other words, to represent the “real Latino electorate,” these candidates must also represent immigration enforcement. When they discuss the harms migrants experience, notably absent are the conditions in detention centers, where migrants experience overcrowding, medical neglect, solitary confinement, and assault at the hands of their guards (Baumgaertner Reference Baumgaertner2024; Moore Reference Moore2020; Salam Reference Salam2024). To discuss these harms would necessitate the condemnation of these “real Latinos,” their vision of Latinidad reveres. By upholding CBP agents as family and community members, these candidates remove from the political narrative the possibility of characterizing these state actors as agents of exploitation. The actions these state agents take, and by extension immigration enforcement policies writ large, cannot be oppressive. In other words, and as Beltran (Reference Beltrán2020) argues, Latinos’ presence as “both police and population” legitimates the bombastic rhetoric and violence enacted against migrants, ultimately “justifying and obscuring the supremacist logics at play” (98). These candidates’ attachment to CBP does not threaten their narrative of the humanitarian border crisis and articulation of Latinidad; it is an extension and confirmation of both. Their race-gender-consciousness grants them the ability to, as “real Latinas,” reconcile seemingly contradictory stances on immigration. It also allows them to navigate Republican circles in ways previously denied to women of color, particularly by allowing them to express political outrage and engage in the same far-right politics as their most ideologically extreme co-partisans.

How Far Is Far Right? Election Denials, Motherhood, and Political Anger

In a New York Times article, Garcia, Flores, and de la Cruz were all named as exemplifying the rise of the “far right Latina” (Medina Reference Medina2022). The candidates have varying responses to the title, with Garcia and Flores being the most vocal opponents. “I don’t care for the far left just as much as I don’t care about the far right. It’s just not who we are,” Flores claims. “No disrespect, but [far right] is just not who we are as a Hispanic community. We’re conservative, we’re a lot more moderate” (The Megyn Kelly Show, 8/9/22). They claim the far-right label is an overreaction from white mainstream media. Garcia claims high school classmates expressed that if she was considered far-right, that meant they were too. Although Flores has previously referenced the Qanon conspiracy theory in social media posts, she claims doing so was a tactic to attain a broader audience rather than a reflection of her personal beliefs. Additionally, when prompted, de la Cruz has carefully admitted Biden was “the duly elected president.” However, there is more to the far-right claims than these candidates downplay.

All candidates hold a variety of political stances that align with the Trumpian politics that encompass the farthest wing of their party. Both Flores and Armendariz-Jackson are staunchly against the COVID vaccine mandates. Their views range from Flores opposing the idea of requiring CBP agents to take the vaccines to Armendariz-Jackson claiming the government is threatening and silencing doctors who critique the vaccine. They are election deniers who publicly support the January 6th insurrection. Garcia attends Trump rallies where he condemns the January 6th committee investigating the insurrection. In her own political rally she calls for the firing of then-Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (Truth and Courage Rally, 11/4/22). In an interview with Jorge Ramos, Armendariz-Jackson cites the conspiracy documentary 2000 Mules as evidence that the 2020 election was stolen. de la Cruz posted two videos on her official congressional Facebook page where she repeats claims of election fraud. In the first, she instructs the county elections commissioner to “answer to your people,” and “fix” the fraudulent election (11/17/20). In the second, she claims to be a victim of voter fraud, having lost in 2020 against Democratic incumbent Rep. Vicente Gonzalez.

What I wanna know from my haters is: how does it feel? How does it feel to cheat the system so badly and still barely win? I mean that must feel really bad inside, right? Like “Man, we cheated so big and we barely won! We should’ve won bigger!” I feel really bad for you guys because I’m sure y’all put in a lot of hard work into this and I only lose by 6500 – probably fraudulent – mail in ballots. (Facebook Live, 11/10/20)

Later in the video, de la Cruz calls for medical professionals in the feed to check Rep. Gonzalez’s medication because she suspects he “may be bipolar.” All candidates take firm pro-life stances, though Armendariz-Jackson is the strongest proponent by far, calling Planned Parenthood a “satanic temple” and arguing “the separation of church and state [is] a thought from the pit of hell” (Power and Counsel with Pastor Salazar, 1/6/21). In short, the “far right” label and accompanying brand of outrage politics are a fitting aspect of these candidates’ politics.

Through an allegiance to far-right claims and rhetorical strategies, the case studies in this analysis depart from research on the Latino gender gap (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2014) and problematize research on Republican women. Contrary to the analysis of Republicans like Mia Love, the first Black Republican woman elected to Congress, who was unable to utilize the same outrage politics as white Republican women (Wineinger Reference Wineinger2021), the candidates in this study display anger in ways that sometimes tap into but ultimately break from maternalistic roles. While these candidates’ anger at the suffering of migrant children or concern over children overdosing on fentanyl are arguably maternal stances, the outrage they display toward immigration, vaccines, and the 2020 election is not. de la Cruz and Armendariz-Jackson’s indignation at the 2020 election is not rooted in maternal ideals about protecting children’s welfare. Armendariz-Jackson’s choice to post videos of herself following migrants being deported out of El Paso (Vice, 7/29/22) is not tied to her identity as a mother. Flores and Garcia’s outrage against the requirement of their spouses’ vaccination against COVID has no ties to an argument for protecting children. An interesting manifestation of these candidates’ political outrage is a pointed critique of the political parties: these candidates claim Latinos have become a captured group.

Evading Group Capture

Coined by Frymer (Reference Frymer1999), “electoral capture” occurs when a group which

votes overwhelmingly for one of the major political parties…subsequently finds the primary opposition party making little or no effort to appeal to its interests or attract its votes…The party leadership, then, can take the group for granted because it recognizes that…the group has nowhere else to go. Placed in this position by the party system, a captured group will often find its interests neglected by their own party leaders. (8).

This, Frymer argues, is how Democrats have simultaneously relied on Black voters for electoral success while also pushing aside their interests. This argument has been articulated by both Black Republicans (Farrington Reference Farrington2016; Fields Reference Fields2016; Wright Rigeur Reference Wright Rigeur2016) and some Latino Republicans in prior historical contexts (Cadava Reference Cadava2020).

One of the clearest examples of political abandonment, these candidates argue, is the Democratic Party’s failure to provide comprehensive immigration reform. In the clearest articulation of this argument, Flores states,

Where is the immigration reform that the Biden administration promised within his first 100 days? You know Obama also promised immigration reform within 100 days – no immigration reform. Promises, promises, promises, and it’ll never happen. [Democrats] do not care about the Hispanic community, they don’t care about immigrants, they just use us to get our vote. Then once they get our vote, they forget about us. That’s what’s been happening. (CBS, 11/8/22)

Taking advantage of Latinos’ vote while not representing Latinos’ interests is a common explanation for why these candidates frame themselves as former Democrats. de la Cruz shares, “I am a former Democrat who walked away from the Democratic party because the Democratic party is far removed from the values that are important to Hispanics.” (Fox News, 6/15/22). A lack of policy output is a reason why these candidates claim Latinos will inevitably join the GOP. In a rally of supporters, Garcia yells into the crowd, “Democrats do not own our vote! They’ve taken the Hispanic community for granted and people are waking up!” (Truth and Courage Rally, 11/4/22).

Another layer of these candidates’ use of this framework is reflected in critiques towards the GOP for having permitted Latinos to become captured. As the most vocal critic, Armendariz-Jackson says,

I wish Republicans would wake up and invest in my community because what Republicans are telling my community in El Paso is, “You don’t matter. Border Patrol agents that work in El Paso, you don’t matter” … We have no help from the Republican party and to be honest with you, Steve, I am sick and tired – of course I expect it from the Democrats, but when it’s your own party and those that are supposed to be on your side, I feel like a salmon swimming against the current … I wish the Republicans would wake up. (Lindell TV, 10/10/22)

The other candidates in this study are less forthcoming in their critiques toward Republicans. de la Cruz admits “few Republicans outside of Florida took Hispanic outreach seriously” (Fox News, 11/2/2022) and a common reminder throughout Flores’ campaign is the statement that she is “not loyal to any political party,” emphasizing that though she views the GOP as currently investing in Latinos and aligning with their values, ultimately both parties must work to not only attain, but to keep the Latino vote. Garcia, who began her political career working for Senator Ted Cruz, is silent on this front.

Not only is this argument openly articulated in their appeals, but it is also welded into their vision of Latinidad. These candidates buck against the use of Latinx because to them, “Latinx” exemplifies Democrats’ disinterest in providing substantive representation. On social media, Garcia writes: “The radical left can’t handle that no one ‘owns’ Hispanic voters, so they call us ‘Latinx,’ ‘tacos,’ and ‘frijoles’ to denigrate us. It won’t work. Our movement is growing!” (Twitter, 7/21/22). Similarly, de la Cruz claims “the average abuelita out in the Hispanic communities, they don’t know what Latinx is, nor does it even make sense, and them continuing to push this cultural radicalism on us … is just one of the many reasons why the people who were once with the Democrat Party are now walking away” (Fox News, 10/5/22). This apparent focus on what these candidates view as cultural issues, they argue, comes at the direct cost of addressing more pressing concerns, such as the economy and healthcare. According to these candidates, Democrats’ emphasis on cultural issues has led to a state where “after 119 years of one-party control, we still have entire counties without a single doctor” (de la Cruz Victory Speech, 11/8/22). Armendariz-Jackson also juxtaposes this rhetoric with a lack of substantive results. “You [Democrats] tell us you’re gonna do better, that you’re gonna fix all these problems … but what we’re seeing is the shortages in food” (Real America’s Voice, 3/29/22). Thus, similarly to some Black Republicans (Dawson Reference Dawson2001; Fields Reference Fields2016; Wright Rigeur Reference Wright Rigeur2016), these candidates use the authenticity garnered from their race-gender-consciousness to provide the political legroom necessary to levy this critique towards the political parties, further exemplifying their ability to navigate politically disadvantageous terrain.

It is very possible that this group capture argument may be a product of candidate strategy to convince Latinos to cross partisan lines rather than reflect these candidates’ genuine beliefs. Even if that is the case, this claim nevertheless demonstrates a shift in how women of color can navigate the GOP. It demonstrates women of color can express political anger in ways untethered to their status as mothers and yet still, in the cases of Flores, Garcia, and de la Cruz, attaining mainstream Republican party financial support for their elections, thereby demonstrating there is additional potential than previously understood regarding Latina political empowerment within the GOP.

Conclusions and Implications

In closing, candidates Armendariz-Jackson, Flores, Garcia, and Rep. de la Cruz paint a rich picture of Latino Republicanism with numerous contributions to the study of Latino politics, immigration politics, and scholarship on conservative women in the U.S. Through their race-gender-consciousness, these candidates offer complexity to scholarship on the Latino gender gap (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2014) and their existence as candidates deviates from prior generations of Latina and Republican politicians, who have been overwhelmingly Democrat and Cuban, respectively (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2013; Navarro et al. Reference Navarro, Jaramillo, Garcia, Martinez-Ebers and Coronado2008), thus enriching this scholarship. Further, these case studies expand our previous understanding of the usage of the “Latino threat narrative” in immigration debates (Chavez Reference Chavez2008) and aid in understanding dynamics within Latino Republicans, which remains an area of limited scholarship. These candidates demonstrate how Latino Republicanism can manifest as a brown racial identity which highlights Latinos’ presence as, and complicated relationship to, immigration enforcement (Cortez Reference Cortez2021), thereby underscoring the importance of further scholarship on this front. Their race-gender-consciousness also allows them to circumvent some of the limitations placed on women of color seeking Republican support (Bauer Reference Bauer2020; Dolan Reference Dolan2005) and utilize political anger, which has been previously denied to women of color in the GOP (Sparks Reference Sparks2015; Wineinger Reference Wineinger2021) and in ways untethered to motherhood such as has been required for white conservative women (Deckman Reference Deckman2016; Sparks Reference Sparks2015), thus enriching this scholarship. Additionally, the candidates’ ability to wield the strategic argument of Latino group capture due to the legitimacy they attain through their race-gender-consciousness signals that more should be done to examine this claim, which may inform future discussions about Latinos’ power within the American political landscape. This research also informs us that although the Republican Party culture espouses identity-blind rhetoric, the ways Latino elites navigate the GOP are neither color- nor gender-blind. Indeed, gender politics is not synonymous with women’s politics; ergo future scholarship of Latino Republicanism necessitates an intersectional, gender-conscious lens to reveal that which might be otherwise obscured in gender-blind analyses.

Finally, this scholarship illuminates dynamics within Latino Republican circles that can aid in understanding the results of the 2024 presidential election. I do not claim the rhetoric employed by these candidates is generalizable to other racial groups, or all Latinos, or even all Latina Republicans from Texas. What this study does reveal, however, is a snapshot of the ongoing conversation Latinos are having regarding our relationships to the political parties and role in American politics. Yes, some segments of the Latino electorate are anti-immigrant (Hickel and Bredbenner Reference Hickel and Bredbenner2020; Hickel et al. Reference Hickel, Alamillo, Oskooii and Collingwood2021), but as these candidates demonstrate, even Latinos most entrenched in Republican politics are not required to claim whiteness or discard Latinidad. Even Latinas, who face additional barriers to entry in Republican politics by residing at the intersections of race, ethnicity, and gender, need not abandon ties to immigrants. Indeed, if Latinos’ engagement with the GOP could be explained by an increase in anti-immigrant sentiment, these candidates would not so repeatedly and consistently center narratives of a humanitarian crisis while discussing immigration. They would not advocate for increased pathways toward citizenship, protecting DREAMers, or hiring immigration judges. In short, this project demonstrates Latinos’ engagement with the political parties is far more complex than what can be accounted for in presidential vote choice. These candidates’ campaigns also suggest Latinas have far more flexibility than previously understood regarding our ability to run for office and navigate political parties that have historically restricted our inclusion as viable candidates. In an era of Congressional gridlock and Latinos’ overwhelming support for policies such as the DREAM Act (UnidosUS 2025), the findings of these case studies suggest groups interested in passing immigration reform might find opportunities to pass such legislation by supporting Latina candidates across the political aisle. Therefore, organizations interested in increasing Latinos’ and women’s representation in U.S. political office would be wise to engage Latinos across all ideological and intersectional spectrums rather than being concentrated in Democratic politics, as Latinos continue to demonstrate their increasing opportunities for political empowerment in American politics.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X25100470.

Competing interests

The author is unaware of any affiliation, membership, funding, or financial holdings that may be perceived as a competing interest in the completion of this project.

Funding declaration

There was no funding body utilized in the design or execution of this project.