Introduction

The political year 2021 was the most tumultuous period in the Netherlands since 2002. The year started with the government handing in its resignation over a major policy scandal. This was followed by a comparatively uneventful general election with historically low levels of volatility, which resulted in the most fractionalized Parliament in Dutch political history. The ensuing political events essentially made elite cooperation grind to a halt. The lack of political cooperation stands in stark contrast to the consensual political culture in the Netherlands. The lower house adopted a censure motion against the sitting Prime Minister, which he ignored. As a result, the Cabinet formation period was extremely long. Parallel to these events, the sitting Cabinet Rutte III gradually decomposed: in 2021, 11 Cabinet members left their posts for political, personal or medical reasons. By the end of the year, no new Cabinet had been installed, although the four parties that had formed the Rutte III Cabinet had reached a new coalition agreement.

Election report

The 2021 general election was held under special circumstances. The second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic had just hit the country. The elections took place during a four-month-long lockdown and special measures were taken to allow the elderly and the vulnerable to participate in the elections without risking their health: the elections were held on three days (15–17 March), and people aged 70 and older could vote by mail. The turnout was only three percentage points lower than in 2017. The campaign mostly took place via traditional and social media. Only the populist radical right party Forum For Democracy/Forum Voor Democratie (FVD) campaigned in person despite the Covid-19 restrictions. This fitted with its profile as the anti-lockdown party. The three televised debates between the party leaders therefore were the crucial arena for determining the electoral outcome.

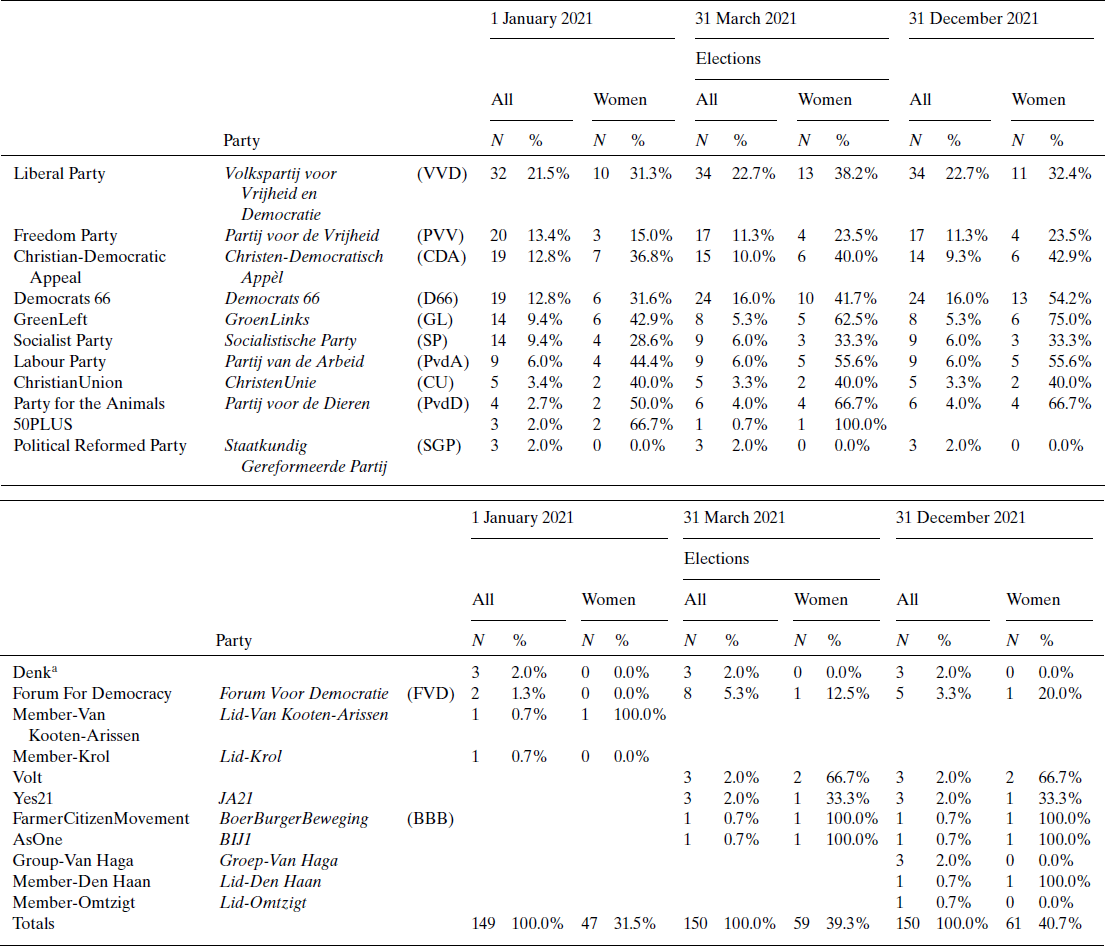

In the elections, the coalition expanded its majority with two seats (see Table 1). This was the first time since 2003 that the parties supporting the government had retained their majority in the elections, and the first time since 1998 that they expanded it. The Liberal Party/Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD) remained the largest party and won one seat more than in 2017. Prime Minister Mark Rutte was rewarded for his leadership in the crisis. Democrats 66/Democraten 66 (D66) became the second largest party with 24 seats. This was five seats more than in 2017. The polls at the beginning of the year indicated D66 would lose seats, but Sigrid Kaag showed herself to be a formidable debater, in particular when debating against Freedom Party/Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV) leader Geert Wilders. When Wilders said that Kaag had betrayed the Netherlands by wearing a headscarf during her visit to Iran, she argued powerfully that she had done so as a representative of the Netherlands, serving the country's interest by advocating for peace in the region. With her strong performance, Kaag became the only credible progressive challenger of Rutte for the position of Prime Minister. She promised new leadership. The Christian-Democratic Appeal/Christen-Democratisch Appèl (CDA) lost four seats. The party had hoped that a late-in-the-race leadership change in December 2020 (with the Minister of Finance, Wopke Hoekstra, taking up the top spot) (Otjes & Hansma Reference Otjes and Hansma2021) would benefit the party. But their campaign was characterized by smaller and bigger mistakes, including Hoekstra not knowing the financial details of his own plans when questioned in a debate, as well as Hoekstra skating on camera in the legendary skating rink Thialf when nobody was allowed to skate inside. The ChristianUnion/ChristenUnie (CU) retained its five seats. The party relies on loyal Protestant voters.

Table 1. Elections to the lower house of the Dutch Parliament (Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal) in 2021

Notes: aDenk means ‘think’ in Dutch and ‘equal’ in Turkish.

Source: Kiesraad (2021).

The right-wing opposition was fragmented. The FVD, which had been plagued by internal struggles related to anti-Semitism in its youth organization in 2020 (Otjes & Hansma Reference Otjes and Hansma2021), reinvented itself as an anti-lockdown party. The party got eight seats. A ‘moderate’ split from the FVD, Yes21/JA21, won three seats. A new party, the FarmersCitizensMovement/BoerBurgerBeweging (BBB), which aimed to represent rural areas and agrarian interests, won a single seat, reflecting the political controversy surrounding the future of farming from 2019 (Otjes & Voerman Reference Otjes and Voerman2020). The largest opposition party, the radical right-wing Freedom Party, lost three seats.

The traditional parties of the left lost 11 seats out of 39. The Socialist Party/Socialistische Partij (SP) and the GreenLeft/GroenLinks (GL) both lost more than a third of their seats. The Labour Party/Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA) did not profit from their loss. The PvdA retained nine seats, repeating the worst result in the party's history. In the last months, progressive voters switched to D66. At the same time, two new progressive parties entered Parliament: the pan-European federalists of Volt, a pan-European party which also has seats in the European Parliament (from the German constituency); and the intersectional feminist party AsOne/BIJ1, which focused strongly on anti-racism. The PvdD won an additional seat (from five to six). The pensioners’ party 50PLUS lost all but one seat due to infighting.

The elections saw only limited volatility. The most recent election with lower volatility was in 1989. These elections did lead to a very fractionalized Parliament. The House had 17 parliamentary party groups – the most it had ever had. The effective number of parliamentary parties expanded to 8.5 – more than it had ever seen.

Cabinet report

On 15 January, the Dutch Cabinet handed in its resignation. The reason for this was the childcare benefit scandal. On 17 December 2020, a ‘parliamentary interrogation committee’ had presented a critical report, Unprecedent Injustice, showing evidence of an overzealous persecution of fraud, discriminatory practices and misinforming Parliament. The Cabinet agreed with all the points made by the commission, with one exception: that the Cabinet claimed that it had never withheld information from Parliament on this matter on political grounds. It took the Cabinet almost a month to decide to hand in their resignation. The reason for this was the Cabinet wanted to be sure that on matters related to Covid-19, it could operate with a full mandate and not merely as a caretaker Cabinet. One minister, Eric Wiebes (VVD), stepped down. He had been State Secretary of Finance in the period 2012–2017, when the overzealous prosecution actually occurred. Between 2017 and 2021, he was responsible for a different, unrelated portfolio, Economic Affairs and Climate. On 20 January, Bas van ‘t Wout (VVD), State Secretary for Social Affairs and Employment, replaced him. The Minister of Social Affairs and Employment (Wouter Koolmees, D66) took over the portfolio of Van ‘t Wout.

After the 17 March elections, the process of coalition formation started. Given the fragmented Parliament, it was generally expected to be a complex formation. After a meeting with the leaders of the new parliamentary parties, chaired by outgoing Speaker of the House, Khadija Arib, two persons were appointed to serve as ‘scout’: the chair of the VVD Senate party group, Annemarie Jorritsma, and the sitting Minister of Home Affairs and Kingdom Relations, Kajsa Ollongren (D66). After just more than a week of exploratory talks with all parties in Parliament, Ollongren, diagnosed with Covid-19, left a meeting with Jorritsma in a hurry. When rushing out, she was photographed holding a piece of paper with notes on an earlier meeting. The paper read, among other things, ‘Pieter Omtzigt function elsewhere’. This referred to Pieter Omtzigt, the CDA MP who had brought the childcare benefit scandal to light together with SP MP Renske Leijten. It was evidence that in these early exploratory talks, at least one political leader had discussed removing this critical MP from Parliament. This led to a controversy and both scouts stepped down. They were immediately replaced by two sitting ministers, Tamara van Ark (VVD; Medical Care and Sport) and Wouter Koolmees (D66; Social Affairs and Employment).

Every participant denied knowledge of the plans to give Omzigt a function elsewhere. When the minutes of the first round of meetings were made public, these showed that Mark Rutte had discussed this possibility. On 1 April, after the installation of a new Parliament, Parliament debated this incident. All the opposition parties supported a motion of no confidence in Rutte, initiated by Geert Wilders (PVV), because he had discussed removing a critical MP from Parliament and lied about it. Given, however, that the sitting coalition retained its majority, Rutte survived the vote. A parliamentary majority did adopt a motion of censure against Rutte, which was introduced by Sigrid Kaag, the leader of D66 and the sitting Minister of Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, and Wopke Hoekstra, the leader of the CDA and the sitting Minister of Finance. In addition to the entire opposition, the CU, CDA and D66 also supported the motion of censure. Rutte, however, ignored the motion. The House also adopted a motion to make a new start with the Cabinet formation talks under the leadership of a new informateur. Subsequently, Van Ark and Koolmees, who had not yet talked to anyone in their official capacity of scout, stepped down.

Herman Tjeenk Willink, a Minister of State who had been involved in some capacity in every coalition formation since 1972, was appointed as informateur on 6 April. He is a member of the Labour Party. He went through a new round of talks with PPG chairs and with representatives of political and social institutions, such as the chair of the Social–Economic Council, Mariëtte Hamer. On 30 April, he handed in his advice to Parliament: the substantial negotiations should start. These should not focus on which parties should govern, but on the substance of a new coalition agreement.

Meanwhile the position of Mark Rutte deteriorated further. As discussed above, Rutte had always argued that information on the childcare benefit scandal had not been withheld from Parliament on political grounds. In April 2021, snippets from the minutes of Cabinet were leaked which showed that political arguments had been used. A no-confidence motion was tabled by Farid Azarkan (DENK) but now the coalition and PvdA and GL voted against it.

A new informateur was appointed on 12 May, Mariëtte Hamer, the chair of the Social–Economic Council but also a member of the Labour Party. She held substantive talks with both the parties and a broad range of societal actors (such as the chairs of the largest trade union and employers’ organization). She identified six parties that would be able to start coalition talks in some constellation: the VVD, D66, CDA, PvdA, GL and CU. The problem, however, was that several parties vetoed specific coalitions: the VVD and CDA did not want to join talks with both the PvdA and GL, while the GL and PvdA refused to join talks without each other. The D66 refused to join talks with both the CDA and CU, while the VVD refused to join talks without the CDA. In order to reach a substantial agreement, Hamer asked the leaders of the two largest parties, Rutte and Kaag, to draft a coalition agreement. In late August, after this document was drafted and the PvdA, GL and CDA noted that this draft would be a good start for the coalition agreement, substantive talks still did not start because of the enduring vetoes. On 3 September, Hamer stepped down as informateur. She was succeeded by Johan Remkes, the interim governor of Limburg and a former VVD minister. On 26 September, the D66 ended their veto of a coalition with the CDA and CU. This allowed for the formation of a VVD–D66–CDA–CU coalition. On 5 October, Wouter Koolmees was appointed informateur in addition to Remkes to lead negotiations between these parties. He formally continued as minister, but his portfolio was overseen by the State Secretary of Social Affairs and Employment. On 15 December, the negotiators presented an agreement, but no new Cabinet was installed before the end of the year.

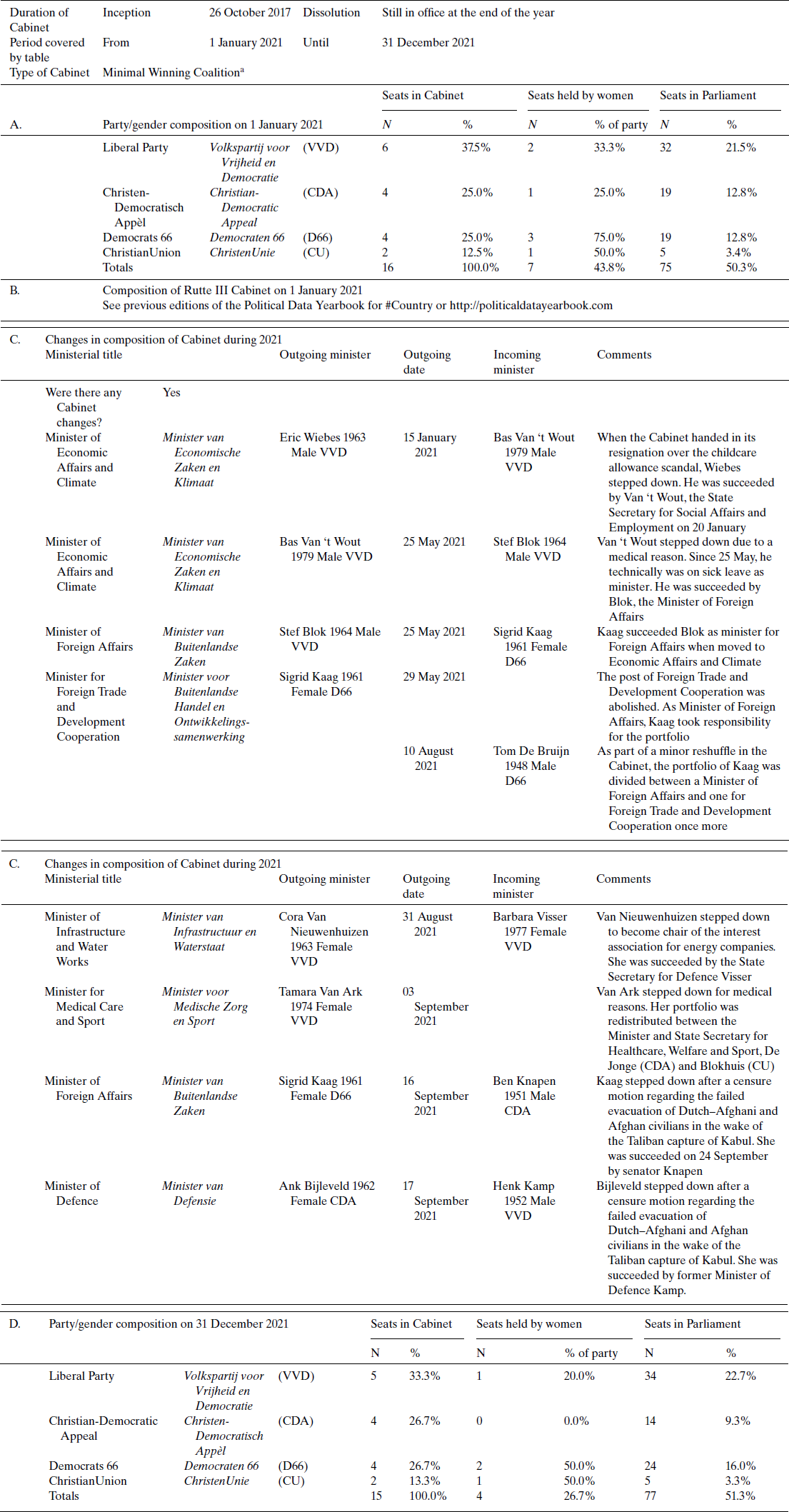

After the elections, there was an unusually high turnover in the Cabinet (see Table 2). Seven Cabinet officials left the Cabinet; three changed positions; and six new Cabinet members were added.

Table 2. Cabinet composition of Rutte III in 2021

Note: aBefore the election, as the FvD seat left vacant by the departure of Theo Hiddema was not filled, Parliament effectively had 149 seats, and the 75 seats of the coalition mathematically had a minimal winning majority, but it functioned as a minority Cabinet.

Source: Parlementair Documentatiecentrum (2021).

On 24 May, Van ‘t Wout stood down as Minister of Economic Affairs and Climate for health reasons. He was replaced by Stef Blok (VVD), the sitting Minister of Foreign Affairs. Blok's portfolio was taken on by Sigrid Kaag (D66), the Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation and political leader of the D66. The VVD appointed a new junior minister to the Cabinet, Dilan Yeşilgöz, responsible for climate and energy policy.

On 10 August, three new Cabinet members were added: Tom de Bruijn (D66) became Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, relieving Kaag. The VVD MP Dennis Wiersma became State Secretary for Social Affairs and Employment, filling the vacancy left by Van ‘t Wout in January. The D66 MP Steven van Weyenberg became State Secretary for Infrastructure and Water Works, replacing Stientje van Veldhoven, who left the Cabinet to join the World Resources Institute. The appointment of these new ministers was in part recognition that the coalition formation would not be quickly resolved. After the appointment of Wiersma and Van Weyenberg, concerns rose among opposition politicians and constitutional scholars about whether these MPs could be a member of Cabinet and an MP at the same time. On 3 September, Wiersma, Van Weyenberg and Yeşilgöz left Parliament.

On 31 August, Cora van Nieuwenhuizen (VVD), Minister of Infrastructure and Water Management, left the Cabinet to become chair of the interest group of energy production companies. She was replaced by Barbara Visser, State Secretary for Defense. On 3 September, Tamara van Ark, Minister of Medical Care and Sport, stepped down for medical reasons. Her portfolio was redistributed between the Minister of Healthcare, Welfare and Sport, Hugo de Jonge (CDA), and the state secretary at that department, Paul Blokhuis (CU).

On 16 September, the lower house adopted two motions of censure concerning the late and failed evacuation of Dutch–Afghani civilians and Afghan civilians who had assisted the Dutch military in Afghanistan, in the wake of the Taliban capture of Kabul. One concerned the Minister of Defense (Ank Bijleveld, CDA) and the other the Minister of Foreign Affairs (Sigrid Kaag, D66). The CU, still formally part of the coalition, voted in favour of both motions. Kaag immediately announced her resignation. One day later, Bijleveld stepped down over the same matter. On 24 September, Ben Knapen, who had been CDA State Secretary of Foreign Affairs between 2010 and 2012, and who was chair of the CDA Senate party group, became the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Henk Kamp, who had been VVD Minister of Defense between 2003 and 2007 (and had served in various other Cabinet functions before and after), became Minister of Defense.

On 25 September 25, Mona Keijzer (CDA), State Secretary for Economic Affairs and Climate, was sacked by Prime Minister Rutte because she had spoken out publicly against the plans of the government to introduce a Covid-19 passport. Her portfolio was taken over by the Minister of Economic Affairs and Climate, Stef Blok.

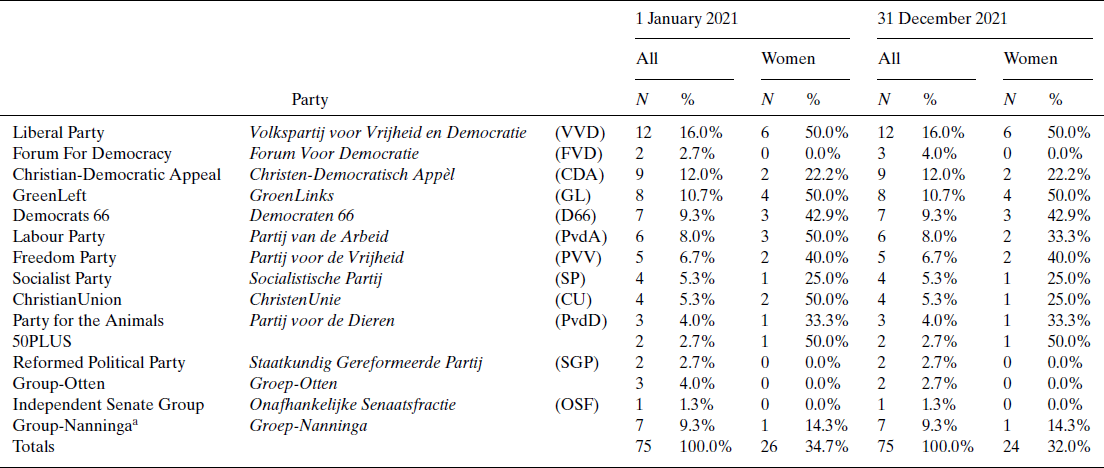

Parliament report

On the first day of the new Parliament, a new speaker was elected. Parliament elected Vera Bergkamp (D66). She beat the sitting speaker Khadija Arib (PvdA) and second vice-speaker Martin Bosma (PVV) with 74 to 38 and 27 votes. Bergkamp is the first D66 speaker of Parliament.

On 6 May, Liane Den Haan, the only 50PLUS MP, announced that she had left the party due to ongoing conflicts with the party board. She continued as an independent MP. On 13 May, three FVD MPs led by Wybren van Haga left the party's PPG to form an independent group, the Group-Van Haga. The reason for this was an internal conflict over a poster posted online by FVD leader Thierry Baudet linking the Covid-19 measures to the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands during Second World War.

On 25 May, Pieter Omtzigt, one of the two MPs who had investigated the child benefit scandal, which had led to the fall of the Cabinet Rutte III, and who had been the focus of the scandal that stopped the formation talks in its tracks, took a temporary leave of absence from Parliament. On 12 June, after a long, critical memo that he had written about the CDA campaign was leaked, he announced that he would continue as an independent MP when he returned from his leave of absence. He returned to Parliament on 16 September. This increased the number of parliamentary party groups to an unprecedented 19 (see Table 3 and 4).

Table 3. Party and gender composition of the lower house of the Dutch Parliament (Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal) in 2021

Source: Parlementair Documentatiecentrum (2021).

Table 4. Party and gender composition of the upper house of the Dutch Parliament (Eerste Kamer der Staten-Generaal) in 2021

Note: aThis group was called (and chaired by) Van Pareren until 15 February.

Source: Parlementair Documentatiecentrum (2021).

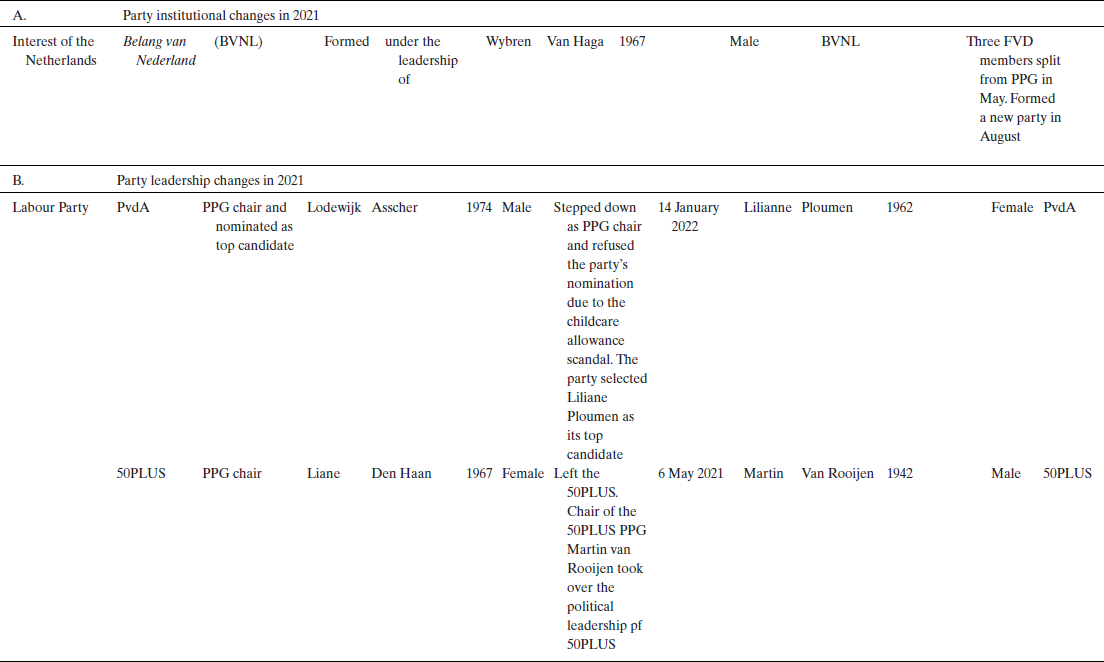

Political party report

Just before the elections two parties had to formally appoint their top candidates (see Table 5). The CDA held a virtual congress to appoint Wopke Hoekstra as leader on 9 January. On 14 January, Lodewijk Asscher stood down as party leader. He had been Minister of Social Affairs and Employment in the Cabinet Rutte II and he felt responsible for the childcare benefit scandal. Lilianne Ploumen, the third on the party list, took the top spot on 23 January.

Table 5. Changes in political parties in the Netherlands in 2021

During the coalition negotiations, the PvdA and GreenLeft cooperated intensively. They operated with a joint negotiation team. This was the most intense cooperation between progressive parties in nearly 40 years. After they left the coalition negotiations, the two parties signed an opposition agreement.

On 7 August, the three MPs who had left the FVD PPG registered a new political party: Belang van Nederland/Interest of the Netherlands (BVNL). This new party combined neoliberal economic positions, Euroscepticism and resistance to anti-coronavirus measures. It was led by Wybren van Haga.

Institutional change report

The coalition agreement committed the government to pursuing a constitutional revision to allow for judicial review. This was in response to the childcare allowance scandal where citizens had been victimized by overzealous persecution that was based on the law but infringed their basic rights.

Issues in national politics

The main substantive issue on the political agenda was Covid-19. The Netherlands continued the lockdown that was initiated in December 2020 until 3 March 2021 (Otjes & Hansma Reference Otjes and Hansma2020). On 14 September, the Netherlands retracted all general Covid-19 regulations. A certificate showing that people had either been vaccinated against, tested negative for or had recovered from Covid-19 was required for visiting restaurants, bars, hotels and cultural institutions from 25 September. The Cabinet considered limiting this to requiring vaccination or recovery for such services, but resistance from the CU and CDA prevented the coalition from pursuing this. In November and December, Covid-19 regulations returned again to fight the rising infection rates, ending with a general lockdown on 18 December. This was followed by a re-introduction of support measures for businesses. The measures against Covid-19 led to public riots, with Eindhoven (25 January) and Rotterdam (23 November) as extreme cases.