Introduction and contextualisation: a graphic representation of musical decline in England

In recent years, music education within English state-funded secondary schools has seen significant and consistent decline, particularly at advanced levels. In 2019, Whittaker et al. (Reference WHITTAKER, FAUTLEY, KINSELLA and ANDERSON2019) presented a systematic analysis of geographical and social demographic trends for Advanced GCE (A-Level) uptake in music, highlighting how music/music technology had declined in state schools by 35% in eight years. Subsequent figures published by the Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual, 2023a) highlight the slow continuation of this trend (see Figure 1) with only 4,929 pupils taking A-Level Music in state-funded schools in 2022/23, indicating a 41% reduction in 11 years. Meanwhile, overall pupil numbers have increased from around 8.2m to 9.1 million (c. 11%) over the same period (DfE, 2011, 2023a), marking an even larger real-term reduction in A-Level Music numbers. These statistics are echoed for GCSE music (the typical pre-requisite for A-Level study), with an all-time low of 29,730 entrants in 2023, marking a reduction of 27% since 2010 (see Figure 2). Furthermore, Ofsted’s recent Music Subject Report highlighted an erosion of statutory pupil entitlement, stating that ‘the trajectory of music education in recent years has been one in which schools have reduced key stage 3 provision’ (Ofsted, 2023: online). Reports have connected such musical decline in secondary schools to recent neo-liberal governmental policy (e.g. Savage and Barnard, Reference SAVAGE and BARNARD2019; Daubney et al., Reference DAUBNEY, SPRUCE and ANNETTS2019; Underhill, Reference UNDERHILL2022), exemplified by the DfE’s exclusion of music from the English Baccalaureate (EBacc) which, according to Anderson (Reference ANDERSON2022: p. 162), ‘has been a significant contributory factor in maintaining music’s peripheral nature as a school subject’. Ofsted therefore concluded that:

In just under half the schools visited, leaders had not made sure that pupils had enough time to learn the curriculum as planned by the school. This meant that, in these schools, pupils were not adequately prepared for further musical study. (Ofsted, 2023: online)

Figure 1. A-Level entrants in England since 2008 (Ofqual, 2023a).

Figure 2. GCSE entrants in England since 2008 (Ofqual, 2023b).

Whilst such ‘further music study’ at more advanced levels within English schools is not limited to A-Level, which sits amongst a wider suite of vocational qualifications like BTEC Level 3 or graded instrumental exams, Whittaker (Reference WHITTAKER2021) affirms the long-standing place A-Level has had in enabling progression into higher education, and indeed the value in principal of the “broader range of musical skills” (p. 146) it aims to address, including performance, listening/music history and composition. However, set against Ofsted’s summation, the pre-requisite breadth and depth of knowledge and skills needed to engage with this A-Level content, and indeed the ongoing prevalence of a Western European Art Music canon therein (see Whittaker, Reference WHITTAKER2020), makes A-Level Music itself arguably inaccessible and/or exclusionary for many young people, ‘especially amongst those hailing from disadvantaged backgrounds’ (Whittaker, Reference WHITTAKER2021: p. 155). In summary, overall musical provision has seen significant national decline within English state secondary schools and is marked by an inconsistent offer between schools which denies equitable opportunities for progression, calling to mind Darren Henley’s Reference HENLEY2011 criticism that ‘Music Education in England was “good in places, but distinctly patchy”’ (Henley, Reference HENLEY2011: p. 5).

This conclusion connects with Whittaker et al.’s (Reference WHITTAKER, FAUTLEY, KINSELLA and ANDERSON2019) key finding, where areas with higher historical progression rates into higher eEducation (defined as ‘participation of local areas’ or ‘POLAR’ ratings) had better uptake of A-Level Music whilst:

Areas of lower levels of A-level music entry tend to correlate with lower POLAR ratings and greater levels of deprivation. This significant finding has profound implications for equitable access to music education, especially at advanced levels. (Whittaker et al., Reference WHITTAKER, FAUTLEY, KINSELLA and ANDERSON2019; p. 1)

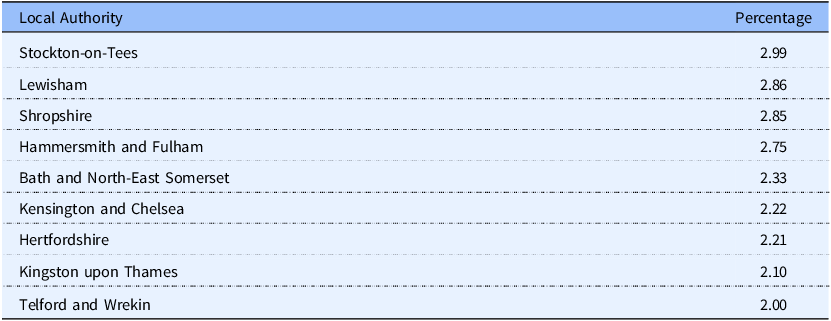

Indeed, Whittaker (Reference WHITTAKER2021) subsequently pointed out that ‘the independent school sector (which is mostly fee-paying) accounts for a disproportionately high number of A-level music entries, and that the overall proportion of entries from the independent sector is growing’ (Whittaker, Reference WHITTAKER2021; p. 146). Low uptake of A-Level Music across England is therefore marked by regional and sociocultural inconsistencies and inequalities, with clusters of relative stability in affluent areas/settings set against larger, more deprived geographical areas hosting fewer and fewer music students. For example, where in 2019 Whitaker et al. identified four local authorities with no state-funded A-Level Music entrants, recent governmental figures (DfE, 2023b) from 2022/23 show how that had increased to 10 local authorities (Middlesburgh, Blackburn with Darwen, Knowsley, Salford, Tameside, Barnsely, Rutland, Thurrock, Portsmouth and Southampton). Moreover, 67 local authorities had fewer than 10 A-Level Music entrants whilst Hertfordshire alone had 168. When local populations are accounted for (Nomis, 2021: online) this means that residents in Hertfordshire were more than four-times as likely to take A-level Music as anyone in the North-East of England, or Yorkshire and the Humber (both areas of high deprivation). Interestingly, when music entrants are compared to their associated A-Level populations within each local authority, the relative ‘health’ of music cohorts shows less extreme variation and less obvious regional inequality. Instead, the healthiest relative cohorts (see Table 1) are spread across England, typically within metropolitan areas (and often more affluent areas therein, like Trafford within Greater Manchester), whilst rural areas and those with high deprivation perform poorly (exemplified by the 10 local authorities with no A-Level entrants). Finally, when A-Level Music numbers are compared to relative pupil populations in preceding years (i.e. compared with high school pupils aged 11–16 years in each local authority), regional progression rates into A-Level Music once again highlight inconsistencies, and when represented on a map (Figure 3) are remarkably consistent with similar graphics pertaining to levels of deprivation (Figure 4), particularly in the North East and West of England, and certain rural areas. In short, A-Level Music uptake is marked by regional inconsistency that echoes social deprivation and poor regional progression rates into post-16 Further Education. Consequently, authorities like Hartlepool and Stockton-on-Tees can have good relative proportions of A-Level students taking music, but nonetheless very poor progression rates into Further Education on the whole, which is echoed (to a lesser extent) across most of the North-East and North-West of England. In other words, the problem is not necessarily with music per se, but broader social inequity.

Table 1. Percentage of A-Level Pupils Taking Music – Top Ten Authorities

Figure 3. Progression rates from KS3/4 to A-Level in each local authority (DfE, 2023b).

Figure 4. Distribution of the index of multiple deprivation by local authority (MHCLG, 2019).

It is important to note that Darren Henley’s advocacy for the National Plan for Music Education (henceforth NPME, or NPME2 for the new National Plan) was ‘to ensure patchiness is replaced by consistency’ (Henley Reference HENLEY2011, p. 15) and that the subsequent distribution of resources through the newly formed ‘Music Education Hubs’ (MEHs) was supposed to provide all children with ‘the opportunity to learn a musical instrument; to make music with others; to learn to sing; and to have the opportunity to progress to the next level of excellence’ (DfE & DCMS, 2011: p. 9). However, despite increases in first-access instrumental tuition (i.e. beginner instrumental lessons, often taught in whole-class settings), Fautley and Whittaker (Reference FAUTLEY and WHITTAKER2017) outlined a marked decrease in advanced pupils, stating that ‘the apparent drop in advanced instrumentalists having tuition through MEHs could cause problems in the future for the world-class music for which the UK is known’ (Fautley & Whittaker, Reference FAUTLEY and WHITTAKER2017: p. 63). Indeed, more recent figures from Arts Council England (2024) detailing the number of pupils within Music Education Hubs (now called ‘Music Hubs’ post NPME2) that are working at different grade levels (i.e. music grades as mapped against the Regulated Qualification Framework (Ofqual, 2015) levels) show a slow continuation of this decline in all areas except first-access provision (see Figure 5), and an extreme drop in all provision immediately post-pandemic (data was not collected between 2019 and 2021). With fewer young people reaching more advanced instrumental levels, the likelihood of taking A-Level Music is further undermined and the DfE is in danger of failing to realise their NPME2 vision that children ‘have the opportunity to progress their musical interests and talents, including professionally’ (DfE, 2022: p. 8).

Figure 5. Standards achieved: pupils receiving small group and instrumental tuition, including WCET (Arts Council England, 2024).

In summary, recent statistics pertaining to state-funded advanced music teaching paint a bleak national picture. With the majority of English Local Authorities facing extremely low A-Level uptake (particularly those with high levels of social-deprivation), according to Whittaker ‘A-level music is under threat at a national level, with this being particularly acute in state-funded schools, and its continued existence is far from guaranteed’ (Whittaker, Reference WHITTAKER2021: p. 158). Moreover, statistics point to low provision, uptake and progression across all stages of state-funded music education, and so I argue there is a profound risk to the entire ecology of music education in England. Consider the image of a tree: beneath the ground, an unseen mass of roots, with countless tiny tendrils, draw water and nutrients into thicker pathways which eventually break the ground in a strong trunk, taking nutrients up to produce leaves and fruit. In the same way, first-access provision should lead into evident pathways throughout communities and schools, and A-Level should function as a supportive intersection between school and higher education (and beyond). With the systematic erosion or removal of any of those key intersections, I suggest this whole eco-system is put under threat.

Sandbach school: a ‘specialist’ A-Level music course

Despite this bleak outlook, certain local authorities seem to resist these trends. One of those is Cheshire-East: in 2022/23, it had 30 A-Level students (DfE, 2023b) which was 1.62% of their general A-Level population and 0.138% of the associated KS3/4 population. This puts Cheshire-East in the top 25 local authorities against all these metrics, far surpassing any other rural authority in the North. Whilst Cheshire-East sits in the middle of the multiple indices of deprivation scale (see Figure 4), the ONS stated that ‘of the 316 local authorities in England, Cheshire-East is ranked 226th most income-deprived’ (ONS, 2021: online) and is marked by profound ‘internal disparity’ with highly affluent areas (e.g. Wilmslow, Alderley Edge and Knutsford) set against larger deprived towns like Macclesfield and Crewe. Sandbach is a small market town neighbouring Crewe and has two state-funded single-gender secondary schools with attached co-educational 6th forms: Sandbach High School (girls) and Sandbach School (boys). Originally founded as a private independent school, Sandbach School became a state-funded independent grammar school in 1955 before becoming one of the first ‘Free Schools’ in England in 2011. ‘Free Schools’ were introduced via the coalition government’s Academies Act (2010) functioning as non-profit-making all-ability schools which are free to attend but are largely independent from local authority governance, instead being run as charitable trusts accountable to independent boards of trustees. The DfE’s claim that Academisation and ‘moving control to the frontline – as close to the classroom as possible – is an effective way of improving performance’ (DfE 2016: p. 8) has been heavily contested, with critics arguing that this resulted in ‘over 70 per cent of those schools having less freedom than they had before’ (West and Wolfe, Reference WEST and WOLFE2018: p. 4). Nonetheless, in principle, it does allow for the possibility of curricular freedoms that are responsive to local demands, and for Sandbach School’s music progression rates this seems to be proving fruitful. In 2023/24, Sandbach School had a mixed cohort of ten A-Level Music students who came to the 6th form from all over Cheshire-East: that number was c. 37% of Cheshire-East’s entire A-level Music populous, and was equal to or better than 70 entire local authorities (DfE, 2024a). Why then is Sandbach School doing so well?

In 2019, Sandbach School launched its ‘Specialist A-Level Music’ programme, building on an established A-Level pathway through partnership with the Love Music Trust (the organisation which is Hub lead for Cheshire-East, henceforth ‘LMT’) and the Royal Northern College of Music (RNCM), a specialist music conservatoire based in Manchester. With recruitment challenges for A-Level (in the words of LMT director John Barber) ‘playing out … before our eyes’, the course aimed to enrich the musical ecology of Sandbach School, and Cheshire-East as a whole. For Grace Barber, Head of Music at Sandbach School, this connects to the aforementioned perceived weaknesses within the framework and content of A-Level Music itself (Whittaker, Reference WHITTAKER2021) where, she argued, ‘there needs to be … filling in the gaps, giving students an opportunity to have that greater understanding and knowledge in depth’. This led to a unique partnership approach where the school provided the core A-Level teaching and associated resources whilst also funding and staffing five timetabled hours for enriched musicianship, including chamber music, chamber choir, musicianship, performances and advanced theory (which is taught by John). Meanwhile the LMT funds termly individual lessons with senior tutors at the RNCM, which included access to RNCM open days, audition guidance and performance opportunities. Importantly, the LMT also helps co-ordinate the school’s extra-curricular instrumental and ensemble teaching as part of its role as Music Hub lead, which includes both school specific teaching (i.e. individual, small group and ensemble lessons for pupils within the school) and opportunities for the wider authority (e.g. regional ensembles rehearsing in the evenings within the school). Since 2011 Sandbach School has maintained fairly consistent A-Level Music numbers despite falling provision across Cheshire-East as a whole (see Figure 6: regional data is inclusive of both Music and Music Technology to ensure consistency with pre-2018 data which only gives a single figure for ‘total music entries’ across both these domains). However, from 2021, which was the first year the Specialist A-Level Music cohort was entered for examination, figures indicate a marked increase over recent years (see Figure 7) which bucks both local and national A-Level trends. Moreover, all students from this programme have progressed into higher education, with many going on to study at conservatoires (including the Royal College of Music, Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, Royal Welsh College of Music, Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Leeds College of Music and four students going to the RNCM itself). As a state-funded secondary school and 6th form, this is a remarkable achievement for Sandbach School given current contextual conditions and ‘a looming issue with the “pipeline” for the next generation of musicians’ (Whittaker, Reference WHITTAKER2021: p. 147). Furthermore, given that there are understood to be ‘inequalities in creative subjects within and after HE’ (Comunian et al., Reference COMUNIAN, DENT, O’BRIEN, READ and WREYFORD2023: p. 25), the mandate to explore alternative pathways that facilitate more equitable access to advanced level music education seems evident. Through critically analysing the Sandbach School Specialist A-Level course, it my intention within the subsequent sections of this article to do just that. Through discerning the key elements that have led to Sandbach School’s successes, I hope to outline how partnership approaches to A-Level provision might enable more equitable musical progression.

Figure 7. Sandbach School A-Level Music entrants 2012–2024 (DfE, 2024c).

Methodology: critical discourse analysis as theory and method

Theory

Discourse analysis involves the interrogation of particular texts (and associated practices) in relation to a broader social, political and/or cultural context, and the acceptance of certain theoretical principles before utilising it as a formal mode of enquiry. ‘Discourse’ here draws on social constructionist principals whereby signification, meaning and understanding are framed by the historical, social and cultural conditions in which they appear (Jørgensen & Phillips, Reference JØRGENSEN and PHILLIPS2002). Laclau and Mouffe (Reference LACLAU and MOUFFE1985: 99) therefore affirm ‘the non-complete character of all discursive fixation and the ‘relational character of every identity, the ambiguous character of the signifier’, such that meaning only ever pertains to a given context, and could be ambiguously defined within other domains. For example, the statement ‘music education is important’ might infer particular meanings for a professional musician, which may resonate or conflict with those of a special education needs teacher, or an economist. There is therefore potential for ‘antagonism’ where meanings are in tension between competing discourses, or ‘objective’ discourse which denotes a state of ‘hegemony [that] reduces distinct moments to the interiority of a closed paradigm’ (ibid: p. 79). For Foucault (Reference FOUCAULT1972), discourse therefore has power, where meaning relationships, antagonisms and hegemonies are historically defined and thus primarily ‘given’ to the subject. Whilst meanings can change through social interactions, hegemonic discourses potentially deny such freedoms, particularly within marginalised or oppressed subject positions (e.g. associated with socio-economic status, or class). Discourse analysis is therefore the interrogation of discursive practices within a particular domain, how the associated meanings may be antagonistic or hegemonic with other discourses and how this in turn infers possibility for flexibility in meaning and practice, or not.

This conclusion leads to ‘critical’ discourse analysis (CDA), which ‘addresses social wrongs in their discursive aspects and possible ways of righting or mitigating them’ (Fairclough, Reference FAIRCLOUGH2010: 11). Here, Fairclough (Reference FAIRCLOUGH1992) considers the subject to be both ideological ‘effect’ and active agent, with the potential to either challenge or uphold dominant discourses. Through drawing on a ‘three-dimensional conception of discourse’, CDA examines the make-up of individual texts in relation to the associated discursive practice (i.e. as a particular contextual act of communication) and broader social practices (including ‘relations of domination’ (ibid: p. 87)). Here, Fairclough affirms the usefulness of observing trends or ‘themes’ (Fairclough, Reference FAIRCLOUGH1992: p. 230), and how these might infer ‘commonalities in the way that [subjects] adopt language (or not) and how this affects or is affected by their particular context’ (GARDINER, Reference GARDINER2021: p. 52). This process therefore allows the analyst to move ‘from description to interpretation to explanation’ (Talbot, Reference TALBOT2010: p. 83). Given that state education typically sits at the intersection between subjects, society, politics and culture, CDA has increasingly been utilised within education research (Rogers et al., Reference ROGERS, SCHAENEN, SCHOTT, BRIEN, TRIGOS-CARRILLO, STARKEY and CHASTEEN2016) but is largely unexplored within the field of music education (Talbot, Reference TALBOT2010). It is the intention of this article to build upon my own analytic work in this area (Gardiner, Reference GARDINER2020; Reference GARDINER2021), drawing on CDA to interrogate discourses associated with Sandbach School’s Specialist A-Level Course, and how these reflect or challenge the broader socio-cultural inequalities outlined previously.

Methods

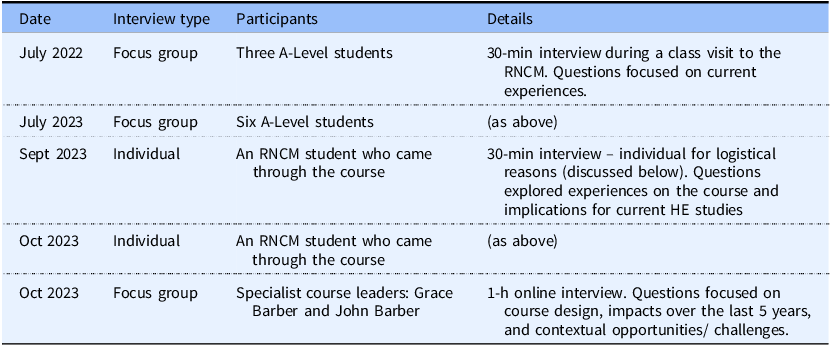

In order to analyse the complex interplay between society, politics and education within the Sandbach specialist course, a series of focus group and individual semi-structured interviews were undertaken with current students, past students and course leaders. In music education research, interviews allow for ‘detailed, individual understandings that are specific to a certain person (or group of people)’ (Williamon et al., Reference WILLIAMON, GINSBORG, PERKINS and WADDELL2021: p. 130) which, with a discourse-analytic lens, can therefore unveil the discourses functioning within that context. Specifically, focus-group interviews enable group discussion, unveiling potential commonalities, assumptions or tensions therein (both with one-another and broader discourses). The interviews were semi-structured with an interview-schedule that focused on the broad topics pertinent to this project, including questions about personal past experiences, reasons for joining/creating the course, connections with School/Music Hub/Conservatoire, personal musical aspirations, outcomes of the course, and the current decline of A-Level. The semi-structured nature allows for spontaneity and for ‘information to emerge from individual voices that may be new or surprising’ (ibid: p. 136). The interviews took place over a 15-month period (see Table 2), were transcribed, and all student responses were anonymised. Given the specificity of the research context, it was not possible nor useful to anonymise responses from the course leaders, and both gave permission as such. The process of transcription formed an initial stage of analysis, facilitating deeper familiarity with the texts in order to highlight initial ‘codes’ or ‘themes’ (Braun & Clarke, Reference BRAUN and CLARKE2006: p. 86) within each interview. The relevant extracts were collated under broader overarching themes, which provided a certain structure for the discourse analysis and a framework to better discern interplay between individual responses and broader socio-cultural conditions. The analytic report has been split into three discreet sections, analysing responses from the current A-Level students (interviews 1 and 2), the graduates now studying at the RNCM (interviews 3 and 4) and finally the course leaders.

Table 2. Interview schedule

Ethics

Before commencing interviews, ethical approval was sought and granted by the RNCM Ethics Committee in June 2022. All participants (and parents for under 18s) were provided with a participant information sheet that outlined the details of the project, the nature of their involvement, how this data would be used and their right to withdraw at any point. In anticipation of the potential personal nature of responses, support services were identified and communicated. Informed consent was obtained for all interviewees. The final report was shared with the course leaders to ensure validity and approval before publication.

A critical discourse analysis of the Sandbach specialist A-Level Music course

Being a student on the course: musical attraction, personal connection and enriched provision

The first group interviews involved two cohorts of year-12 students (16–17 years old) who were currently on the course, interviewed a year apart (July 2022 and 2023) during visits to the RNCM. These pupils had come to Sandbach School 6th Form from a variety of different state-funded schools, including both single-gender schools within Sandbach itself, and from a number of other schools across Cheshire-East, and so they had differing past musical educations and experiences. Both interviews explicitly revealed awareness and personal experience of musical decline in Cheshire-East:

‘I witnessed the decline in my last school. In year 7 it was quite a popular … and gradually it got less and less and less’.

This was particularly the case for A-Level:

‘the people taking the A level has just declined. Like most schools around where I live, don’t even do a music A-Level’.

Various reasons were posited for this, including being ‘too expensive for the school” meaning “it’s not feasible”, and lack of provision for “younger age groups, … especially after the last few years, just be[ing] a lot less …. Covid’. These reasons echo the reports and statistics presented previously (e.g. ACE 2024, Ofsted 2023) and prompted a large proportion of the students (5 from 9) to move to Sandbach School specifically for music:

‘its not very valued I would say … at [previous school] […] not a lot went on there, so why is somebody going to take interest in something that’s just not there’.

In this way, there was both push and pull, with pupils feeling underprovided in past schools and drawn to the Sandbach offer:

‘I always had the idea that Sandbach was a good school. Based [on] they’d won lots of events and stuff’

‘I just thought music was a lot better to be honest, and like obviously the course’.

This draw went beyond the public reputation and often relied on specific personal connections:

‘my mum is a music teacher so she knows quite a lot. She knows John Barber as well. So I had quite a bit of inside knowledge’.

‘past people I knew. Like M*****, and G***** who has gone to the Royal Welsh now. And … like people you’d look up to like in higher years’

A consistent catalyst for this ‘inside knowledge’ was local authority and Hub ensembles, which often take place within the school:

‘as a school we are really lucky in Sandbach … it’s the home of Foden’s, Lions youth brass which got me into music … and we got the Love Music Trust in Sandbach as well’.

That the director of the LMT, John Barber, plays for Foden’s Band (the 2022 ‘Double National Champions of Great Britain’) whilst coordinating (and often leading) Hub partner ensembles (e.g. LMT Senior Big Band) enabled important connections:

‘I’m a percussionist […] and moved over to Sandbach, and that’s where I started getting involved with like the school big band, the orchestra, … and then moved on to the specialist course when I took A-Levels because obviously I knew John, I knew Grace’.

In summary, the push from Cheshire-East and the musical draw of Sandbach, rooted in the vibrant musical activities housed within the school and facilitated through personal musical connections, came through strongly.

This point connects to another important theme, where the students’ focus was on the ‘enriched provision’ more than the core A-Level Music content:

‘I knew that I wanted to do music and I knew that I wanted to do just more than the A level itself’.

Consequently, the elements like chamber music, performance opportunities, aural training, musicianship and theory were often referred to:

‘[the course] helped with like harmonisation and reading different clefs and helping with that … musicianship sort of thing’.

‘performing and doing recitals and stuff. […] and also the chamber music, and working in a group … Like you’re not always going to have someone telling you what to. You need to work on it together’

This reference to the value of playing with others as both enjoyable and nurturing came through particularly strongly:

‘One of the best things is performing together. Playing with different band members’.

‘with this course, you get to play with the different ensembles … not your typical big band or orchestra. … which I just wouldn’t have done if I hadn’t been put in that situation to start with’.

‘It’s exciting what group you are gonna get put with because it can determine whether you do something like pop, jazz, classical’.

Importantly, such provision is only possible with a large enough cohort or ‘critical mass’ from which flexible ensembles and musical communities can flourish. Indeed, this community element seems to be fundamental for nurturing musical skills, interests and aspirations: ‘I think part of it just being around people who have the same goals.”

Furthermore, such a community is also determined by the facilities and resources that can enable it, including both investment in this taught enriched provision (as discussed above) and the physical resource available, which for one student was essential:

‘I came to Sandbach … mainly the percussion instruments as well because my playing is completely improved because I have the instruments that I need to practice on’.

In conclusion, challenging socio-political conditions for A-Level Music certainly prompted pupils to come to Sandbach, but the musical drivers therein were predominantly rooted in the communities they were enmeshed with and how they were ‘supported by co-curricular learning, and musical experiences’ (DfE, 2022: p. 5). In other words, it is through ‘doing more [than] A-Level itself’ that the school supports possibilities for more equitable access to advanced musical learning, and builds ‘a sustainable local “eco-system” for music education’ (ibid).

Going to conservatoire: community bubbles, inside knowledge and applied musicianship

The second set of interviews involved one-to-one discussions with two undergraduate students at the RNCM who had gone through this specialist A-Level course. These discussions highlighted several things that resonated with above themes, particularly the regionally distinct musical community embedded in Sandbach School:

‘there was no other school that had the music department or the facilities as good … I knew that I was where I needed to be for music’

‘it’s well known that Sandbach School’s got such … accredited music, music teachers, music curriculum’.

Again, this awareness was rooted in musical connections formed through school-based ensembles:

‘[I] started playing trombone in the Lions Youth Band. So, I progressed from the beginning band to the junior … then went on to play trombone at the high school … was in the bands there that they did after school and during the lunch times playing trombone again really enjoyed it’.

‘it’s all … all interlinked with the Love Music Trust and the school’.

This prompted one of the students to use a particularly interesting term:

‘I’ve been in … a sort of hub … I’d say that I’m probably … was less aware at high school that it was not normal at all to have a music department as good as the one that I was in’.

The term ‘Hub’ has become synonymous with the NPME’s political restructuration of musical support for schools, with ‘Hub Lead Organisations’ tasked with building support networks (‘interlinking’) across a region, working in addition to, around and/or between that which happens in individual schools. Here, however, the hub is the school, and it is important to note that the LMT (i.e. Hub Lead Organisation for Cheshire East) consider their ‘founding principal’ to be ‘owned, led and managed by schools – “for schools by schools”’ (LMT, n.d.: online). Existing within this ‘Sandbach Hub’ therefore has less to do with structural connections, but personal ones with both staff:

‘obviously the introduction of the course by … John was just quite a really great opportunity’

and peers:

‘So there’s a couple of guys in 3rd year that I know who are now here studying who also went on it … and there was a load of my friends that also auditioned and we were all in this sort of group and playing together’.

Indeed, this connection between the musical ensembles and the communities they build is explicit:

‘the music department was definitely somewhere, that … I just went towards, you know, … I just felt at home there and so they sort of had loads of great ensemble stuff on offer, rock ensembles, wind orchestra’.

Feeling ‘at home’ infers security, rooted in safe personal relationships and environment: ‘It’s just like a nice, nice environment’. For musicians, a sense of belonging extends to particular musical identities, tastes and communities (Dys et al., Reference DYS, SHELLENBERG, MCLEAN, Macdonald, Hargreaves and Miell2017), and importantly the ‘centrality of musical performance activities, and in particular the development of a performer identity, to students’ experience of belonging and achievement’ (Dibben, Reference DIBBEN2006: p. 91). This centrality of musical activity, community and enjoyment is exemplified by the statement:

‘I … went into the big band, which I think was the turning point in it becoming a hobby to something that I seriously considered and to progress … and possibly do A-level …. reading all these charts and playing with these musicians who were at a decent level and just really loving it’.

As before, it was that ‘co-curricular’ offer beyond the A-Level itself which seemed most musically beneficial:

‘the different stuff that we’ve done in chamber choir and in different theory sessions, and actually oral testing as well … doing that every week, funnily enough, really helps your ear’.

‘the oral and dictation stuff, … it does really, really help […] it like just widens your … overall musicianship’.

In these extracts, the focus is less on what Philpott (Reference PHILPOTT, Cooke, Evans, Philpott and Spruce2016: p. 33) describes as ‘knowledge “about” music’ (e.g. factual information) but on how experiences connect to a certain know-how’ and/or ‘knowledge “of” music’ (ibid: p. 34) associated with more procedural, subtle, tacit or intuitive aspects of musical development. Certainly, both students referred to the value of chamber music and certain ‘softer’ skills therein:

‘being put into a small ensemble and then being let loose effectively to find your own music and … train yourselves as a group, and workout things in your group’.

‘you’re in a situation quite a lot of the time in specialist [course] where you have to communicate with other musicians and […] finding out what people’s interests are’.

These extracts affirm the importance of broader musical skills, including musical autonomy (i.e. putting ‘my own sort of twist on’), self-directed learning and communication within group work. Importantly, this enriched provision apparently directly supported current conservatoire studies:

‘a lot of the stuff you do on the course does tie in with what you do here [RNCM] […] for example the keyboard harmony classes really helped with the musicianship stuff in 1st and 2nd year’

‘I got into … a few bands in the first couple months, and session playing, and playing in different people’s stuff. Going through it like that probably helped at the specialist [course]’

‘you need to kind of know how to work things out amongst yourselves. …. specialist course helped with that, it’s, kind of, led on to our [chamber] group being successful’.

Consequently, the students described the course as ‘basically a stepping stone’ to conservatoire, telling ‘you what you need to do. What you need to know’. This essential ‘inside knowledge’ was apparently directly supported through the RNCM termly individual lessons:

‘that [tuition] got me into the sort of RNCM bubble. I had lessons with S*** online …ask him what are the interviews like? What is the audition like? What can I prepare to do this? What’s the course like? What do you play? … try and understand what it’s about before I then apply’.

Much like the discourse of ‘hub’, the term ‘bubble’ here affirms the importance of personal connections and communities, through which the pathways, skills, means and opportunity to progress become evident.

In summary, the apparent value of being on the course extended beyond the taught content to include the community these students were enmeshed with. The discourse is therefore rooted in language elevating personal connections, and how these transferred into musical knowledge that enabled progression, including autonomy, interpersonal skills and musicianship. That image of a hub is again pertinent, where the collection and connection of individual parts builds a particularly enriching ecology: a holistic education rooted in what Barad terms ‘intra-action’ as the ‘mutual constitution of entangled agencies’ (Barad, Reference BARAD2007: p. 33). In other words, the critical mass of engaged musicians (inclusive of both students and staff) and the associated musical activity seemingly support significantly enhanced musical development.

Leading change: building a hub, holistic education, and resisting the status-quo

The final interview was with the course leaders, Grace Barber (Head of Music at Sandbach School) and John Barber (Director of the LMT, and teacher on the course). This raised themes consistent with those above, and the associated professional perspective shed important contextual insights. Firstly, that Sandbach School provides a music education that draws in pupils from across Cheshire-East was again affirmed:

Grace: “We have now a really … even more respected department. […] and that they’ve been drawn from further afield”

John: ‘we can create something that that will draw, … provide an opportunity for these young people who aren’t necessarily going to get it at their school’.

However, John was keen to affirm how this draw is not simply circumstantial, but encouraged through the LMT’s educational strategy:

John: ‘we filled the gaps with our Love Music Trust ensembles, many of which rehearse at Sandbach School because of the relationship we’ve got … it isn’t by circumstance that that Lions Youth Band rehearses there, that the … Love Music Trust Junior big band, and Senior big band, and Junior percussion ensemble, and senior percussion ensemble, all rehearsed there’.

Grace reflected specifically on this inherited culture:

Grace: ‘there’d already been this established culture of … the rooms being a rehearsal venue. […] It’s just a hub. It’s just a hub of music making. It never closes. […] There’s always something going on. And that’s down to years of what John made of … the department, and with the connections with Lions Youth … and launch of the LMT … and Sandbach school became that place’.

That the school is once again categorised as a ‘hub’ marks an instance of ‘intertextuality’ (Fairclough, Reference FAIRCLOUGH1992: p. 75) that echoes the students’ discourse (discussed above) whilst antagonising that of DfE policy, given the LMT is officially Hub-lead for Cheshire-East. Importantly, the essence of this ‘hub’ is (as previously) rooted on personal musical relationshipsFootnote 1 :

John: ‘Music is about communication, it’s about people responding about getting motivated by something … those personal connections are everything, because instrumental tutors become tutors of LMT ensembles. They’re also spreading the message, saying, actually, you could come and have a pathway here because other young people from outside the area have done it’.

It is useful to note that many of these tutors are professional musicians who studied in conservatoires, and for John that connection is key for the students:

John: you’re not aware that it’s a job until somebody who’s doing that job turns up and says I get paid to sing. … I know that’s that might seem alien if you’re working within that organisation. But … many young people are just not aware that you can have a job’.

Thus, the structure of the specialist A-Level from the outset aimed to demystify that pathway:

John: ‘a number of our students … were choosing to explore Conservatoire pathways […] we knew that we wanted to make that provision as … tangible as possible. […] by working in partnership with an HE college, … it just really cements a very clear pathway that … holds the hand onto that …. Unknown’.

Interestingly, the original NPME (DfE & DCMS, 2011: p. 10) specifically required Hubs to facilitate ‘input from professional musicians’, whereas now this is merely suggested as a means by which limited expertise in primary schools ‘could be supported’ (DfE, 2022: p. 24). Similarly, Whittaker notes how ‘applied A-level performing arts used to require students to speak with professional musicians about working in the music industry, but such qualifications were withdrawn in 2017’ (Whittaker, Reference WHITTAKER2021: p. 158).

These assertions connect to a fundamental driver within the Sandbach A-Level course, aiming to better balance “[John] practical music and theoretical music” and address perceived weaknesses in the A-Level syllabus:

Grace: ‘Everything’s very isolated in the [A-Level], and it doesn’t matter which specification you do …. there needs to be, I think, … filling in the gaps, giving students an opportunity to have that greater understanding and knowledge in depth … and eat, live, sleep music’.

It’s interesting to note the intertextuality of ‘filling in the gaps’, used previously by John to describe the LMT’s role, and here A-Level Music teaching itself, denoting an enriched provision of ‘[John] keyboard harmony, chamber music, chamber ensemble, chamber choir, advanced aural training’. For Grace, ‘this enrichment’ has profound musical results:

Grace: ‘it certainly does give them a much better holistic view. … because they do all those things, naturally, those specialist music students do better in their A-level’.

However, as previously, this ‘holistic view’ extends beyond taught content to include the community that is built, as Grace described for one student:

Grace: ‘being surrounded by like-minded individuals, being surrounded by that community, that even though she’s got to stay late and she lives so far away, she knows there’s always someone around she knows as a family, there’s a kitchen’.

This notion of ‘family’ echoes the RNCM students’ previous reflections on ‘feeling at home’, which John explicitly referenced as ‘[a cohort] who want to come to the music department, who have got a place there, who maybe feel more settled, at home’. This environment in turn enables broader musicianship through the associated collaborative music making:

Grace: ‘They’re all together, … it just breeds a community spirit amongst them as well. … They work better. They’ll organise rehearsal. They become more confident. … I think it’s been a fantastic social kind of development for them’.

Again, such broader musicianship was precisely what the RNCM students said facilitated progression into conservatoire, which John is evidently aware of:

John: ‘you’ve got a back catalogue of young people who have gone off to pretty much every Conservatoire in the country that … stand up and say, actually, the course, you know, it helped me achieve those things’.

In summary, the real value of this programme seems to be rooted in the aspiration for enhanced holistic musical experiences, and how this facilitates collaborative learning communities (involving both pupils and staff) whose outcomes extend far beyond the formal taught content. The important thing is in how this creates a “home” for musicians to “eat, live, sleep music”: an inclusive space “[Grace] as musicians and being part of the course, they just kind of accept … adapt.”

Despite the warmth that John and Grace showed for the course, discussions also explored current decline of music provision which John noted ‘was playing out before our eyes’. Here, I questioned the evident risk of further weakening provision elsewhere by drawing pupils in to Sandbach, which Grace acknowledge:

‘we’re in a climate where many departments have been threatened of … stopping courses from happening … unless numbers go up … so it’s kind of survival of the fittest […] that’s something that’s out of our hands, so to speak …. And therefore all we can concentrate on is providing that best provision’.

For Grace, this aspiration is rooted in an ethical imperative to provide equitable access to that ‘best provision’:

‘Traditionally … if you were that sort of musician that … would have had that pathway to conservatoire level … you would go to the Junior RNCM on a Saturday. […] that comes with a cost … [and] an implication on that extra Saturday. And it was kind of like that professional … motivation that it shouldn’t have to be an elitist thing. It shouldn’t have to be the only way that students of any background access that top end tuition and make a pathway possible for them. … we’re opening it up, and I think that motivation to the right of all walks of life [to] access it is really important’.

For Grace, awareness of this inequality demands a constant need to innovate and ‘with the top end and going well, actually, [ask] how can we drive it?’. She stated ‘we want that pathway to try and be engineered throughout’, against which both John and Grace noted the prerequisite for school leadership support, both in principal and in practice. For this specialist course, that strategic support cannot be understated, drawing on a co-funded model between Sandbach School and the LMT to grow a uniquely structured Music Hub that, I would argue, exemplifies the NPME2 mandate ‘to build a sustainable local “eco-system” for music education, through partnerships, with progression, access and inclusion central to their work’ (DfE, 2022: p. 5). Indeed, the LMT’s working relationship with Sandbach School also realises the aspiration that ‘Music Hubs will identify and partner with a small number of Lead Schools’ (p. 5), and that this partnership exhibits a model of music education and progression that could certainly support ‘other schools to improve their music provision’ (p. 53).

Conclusions: A-Level Music in crisis, tending the vine, and Music Education Hubs

The biblical story of Jonah and the big fish is well known, but less so the concluding account of Jonah sitting under a vine in the hot sun. After a worm chews the plant and it dies, Jonah becomes furious in his discomfort, prompting God to respond: ‘You have been concerned about this plant, though you did not tend it or make it grow’ (New International Version, Jonah 4:10). Set against troubling statistics outlined at the start of this article, concern for the future of A-Level Music is justified, but the question is how are we actively tending this pathway? The analogy of a tree presented within the introduction focused on a ground-up perspective on progression, but plants are equally fed by their foliage: the sustainable ecology of that system demands input from all. I therefore suggest that the NPME2’s aspiration for suitable local eco-systems needs to be rooted in partnership. Through a critical discourse analysis of Sandbach School’s specialist A-Level course, I highlighted a particularly effective partnership rooted in the power of musical connections, and how this made progression pathways evident, achievable, and thus attractive. The inextricable interlinking of state-school and Music Hub allowed for far-reaching networks that drew pupils into an enriching musical culture bound to an A-Level programme that is, by design, accessible. The focus on enriched musical provision and high-quality collaborative music making led by professional musicians enabled students to develop an holistic musicianship that supported the A-Level itself and provided stepping-stones to future musical study. I suggest the important conclusion here rests in a necessary rearticulation of the term ‘Music Hub’; more than a political structure supporting schools from outside, the hub here manifests in the inter-personal culture grown within the school itself, and nourished through the LMT’s connections to providers before, after and around that provision. Drawing on the image of a wheel, if Sandbach School functions as the hub, then LMT is more akin to the spokes that make connections with external organisations, who in turn provide cohesion and strength to the entire wheel, and thus a secure and sustainable functionality. However, the integrity of this structure is conditional on all its components: as with the image of the tree, the ecology for music education demands feeding from all sectors. This then speaks to Grace and John’s acute awareness of the risks involved in drawing pupils away from other provision and so potentially weakening the broader regional offer. Here the LMT as Music Hub has a double mandate: to support enriched progression pathways like that at Sandbach School, whilst also (as John put it) ‘being sure about what the reasons are for why they’re not doing [A-Level]’ in other settings, where increases of one or two pupils per year might ensure the sustainability of another regional A-level programme. Such awareness is only possible through continued and deliberate communication and connection with all regional providers and ‘[John] trying to avoid openly, as much as possible, that conflict’, but instead affirm the Hub’s role in supporting the entire region through network and partnership.

From a higher education perspective, it is important to note that the above analysis did not reveal significant perceived value in the course’s formal RNCM partnership beyond the personal connections it afforded. Given the subsequent recruitment of four students to the RNCM, and indeed that all pupils from this course have progressed into higher education, it is helpful to reflect on the NPME2’s expectation that ‘all music educators, including in further and higher education, help young people to understand routes into careers in the music and wider creative industries’ (DfE, 2022: p. 5 p. 9). Considering poor recruitment to music courses across the HE sector (such that both Oxford and Cambridge University now accept ABRSM Music Theory as an alternative entrance requirement), I suggest that those benefitting from pre-tertiary provision need to be more mindful of their responsibility therein: as Žižek puts it, ‘before the subject “actually” intervenes in the world, he must formally grasp himself as responsible for it’ (Žizžek, Reference ŽIžEK1989: 278). I therefore conclude that the whole music sector (inclusive of the profession) needs to provide more strategic input into pre-tertiary pathways, including active political influence, national advocacy, workforce development, student mentorship and teaching, and above all resource. As the NPME2 comes into effect, and hubs formally partner across larger geographical areas, there is now both the mandate and opportunity for meaningful strategic influence and change. Nurturing more far-reaching personal partnerships, inclusive of everything from first-access provision to conservatoires/universities and professional musicians, and ensuring equitable access for all students to this enhanced provision is, I suggest, both pedagogically wise and ethically imperative. Inequal access to music education and ongoing regional ‘patchiness’ (Henley Reference HENLEY2011, p. 15) of provision (especially at advanced levels) might thus be addressed, ensuring a more cohesive musical ecology to subvert declining music education in England.

Robert Gardiner is currently programme lead for music education at the Royal Northern College of Music, leading on education programmes across all degrees. Robert trained as a clarinet player at the RNCM and Zurich University of the Arts, before focusing on music education and completing a Doctorate at Manchester Metropolitan University. He still works as a school music teacher, leading provision in a special educational needs school, a primary school and local ensembles. Current research interests include music teacher education, educational discourse and policy, ideology and education, educational creativity and social equity through music.