Introduction

What factors influence how Europeans think about economic sanctions? Is thinking about it only purely reflecting economic interests, or do Europeans think in terms of geopolitics too? Answering such questions is crucial to understanding public support for sanctions as one of the key instruments of European foreign policy. For at least a decade, scholars have acknowledged the importance of public opinion for formulating the European Union's Common Security and Defense Policy (Faust & Garcia Reference Faust and Garcia2014; Irondelle et al. Reference Irondelle, Mérand and Foucault2015; Oppermann & Höse Reference Oppermann and Höse2007; Oppermann & Viehrig Reference Oppermann and Viehrig2009). Scholars have also noted a growing tendency in the EU (and elsewhere) to use sanctions as a default tool to respond to any kind of adverse development (Giumelli Reference Giumelli2013b). By one account, 57 per cent of all post‐Second World War sanctions were imposed since the 1990s (Morgan et al. Reference Morgan, Bapat and Kobayashi2014). The sanctions became popular even though their effectiveness is debatable (Drezner Reference Drezner2011; Portela Reference Portela2014). The academic debate about the utility of sanctions ranges from those opposing sanctions as a tool of economic statecraft (Pape Reference Pape1998) to those who cautiously argue in their favour (Drezner Reference Drezner1999), and those who proclaim their success (Miller Reference Miller2014).

Every sanctions regime has its opponents and proponents. Existing research has thus far attempted to analyse the pros and cons of each side, or settle the dispute about sanctions’ effectiveness. What is missing in these debates is an attempt to explain the variation in attitudes towards sanctions. Sanctions, as a tool of coercive diplomacy, engage public opinion on different levels. As they are, fundamentally, a coercive tool against the target country, sanctions are related to geopolitics. However, sanctions also influence trade exchange with the target and hence trade interests are relevant too (Drezner Reference Drezner1999, Reference Drezner2003; Drury Reference Drury2001). But sanctions can be also seen as a form of punishment (Nossal Reference Nossal1989), and indeed, previous research has related preferences for the use of the tools of coercive diplomacy to societal norms (Portela Reference Portela2015; Wagner & Onderco Reference Wagner and Onderco2014). However, research has not attempted to engage the variation at the individual level using public opinion data. Existing research has studied either special interests mobilisation in the face of sanctions (McLean & Whang, Reference McLean and Whang2014), or used experimental designs to gauge the effects of perceived effectivity of such tools (McLean & Roblyer Reference McLean and Roblyer2016), but not in the European setting. This article aims to fill this gap by explaining why individual Europeans differ in their approval of sanctioning Russia for its actions in Ukraine. At the same time, the article makes a wider case about European attitudes towards sanctions.

The dispute about how to respond to Russia's actions in Ukraine has divided European countries, and the European population. In particular, the question of whether to use sanctions as a response towards Russia has attracted numerous critics among European leaders, as well as among the European population. In December 2015, Italy opposed the extension of sanctions against Russia in the meeting of the EU ambassadors before the European Council meeting (Burchard & Eder Reference Burchard and Eder2015) and, as Radio Free Europe reported, other countries were in the same camp as Italy (Jozwiak Reference Jozwiak2015). Slovakia's Prime Minister Robert Fico, for example, also called on the removal of the sanctions, claiming that ‘the sooner they are removed, the better’ (Slovak Spectator Reference Spectator2016). The disagreement also runs within the European public: As Pew Research recently reported, European publics are divided about the sanctions against Russia. While 49 per cent of Poles support the sanctions, only about 30 per cent of Italians and less than 25 per cent of Spaniards do (Simmons et al. Reference Simmons, Stokes and Poushter2015). While the sanctions have been widely credited with making a significant dent in Russia's economy, and contributed to the country's economic woes, the debate over whether the sanctions actually influenced (or have a potential to influence) Russia's actions fits well with a wider debate about the utility of sanctions.

This article builds on existing research into drivers of coercive behaviour in international relations at the individual and societal levels to explain the variation. It looks at the importance of geopolitical, economic and ideational factors for explaining attitudes towards sanctions. In particular, the article looks at the relevance of Euroscepticism and anti‐Americanism in explaining the variation in attitudes, controlling for economic situation, partisanship and social norms. While Euroscepticism has been a staple in the study of European integration, looking at Euroscepticism as a determinant of other attitudes not directly related to the EU is novel. The article uses public opinion data from the Transatlantic Trends Survey (TTS) collected in June 2014 in ten European countries. The timing of the collection – after Russia seized Crimea and fomented upheaval in the Eastern Ukraine, but before the downing of the airliner MH17 – allows an analysis of these attitudes before Europeans developed strong emotional positions on the issue. At the time, the EU had only modest sanctions against Russia in place, which included travel bans and asset freezes against 33 individuals, but no other sanctions against Russia were adopted (Council of the European Union 2014). The conclusion offered in this article is that Eurosceptic individuals and those with anti‐American attitudes are more likely to oppose the sanctions against Russia.

Geopolitics, trade and ideas

Sanctions have emerged as the response of choice to foreign policy crises. The EU has at present no less than 40 sanctions regimes, and many of them are applied in cooperation with other partners, chief among them being the United States (Dreyer & Luengo‐Cabrera Reference Dreyer and Luengo‐Cabrera2015). Despite the importance of sanctions for the EU's Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), the determinants of public attitudes on the use of sanctions are yet to be explored in depth. One of the pioneering works in this area is by Clara Portela (Reference Portela2015), who studied why the EU Member States resist sanctions. Building on the theoretical framework of Saurugger and Terpan (Reference Saurugger and Terpan2015), Portela argues that Member States’ resistance is due to two factors: financial and social capacity to resist; and cognitive distance between norms defined at the EU level and those at the level of the national administration. These two factors, she maintains, ‘hold the most explanatory power’ (Portela Reference Portela2015: 60). However, these factors explain what Member States’ national administrations do – they do not look into what the citizens think.

I broadly conceptualise the reasons why individuals can have different attitudes towards sanctions along three lines: (a) geopolitical factors, which capture attitudes towards sanctions based on seeing them as a tool towards advancement of a certain agenda; (b) economic factors, which capture attitudes based on economic calculations and impact; and (c) ideational factors, which capture attitudes based on an understanding of sanctions as a normative response to a certain action.

Geopolitical factors

Russia's dissatisfaction with the status it has been accorded in Europe (particularly in Central and Eastern Europe) has been widely considered to be one of the reasons why it decided to occupy Crimea and stir trouble in Eastern Ukraine (Allison Reference Allison2014; Mearsheimer Reference Mearsheimer2014; Tsygankov Reference Tsygankov2015). The expansion of the EU and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) to the former Soviet sphere of influence, and attempts to include Ukraine in a partnership agreement with the EU, are cited among the reasons. The geopolitical considerations therefore include attitudes towards the EU as well as attitudes towards the United States as NATO's main military muscle.

Within the EU, citizens vary in both their assessment of the EU and in their assessment of the United States. Existing research has noted a drop in popular support for European integration among Europeans, which can be attributed to the financial crisis (Armingeon & Ceka Reference Armingeon and Ceka2014; Hobolt & Wratil Reference Hobolt and Wratil2015; Kuhn & Stoeckel Reference Kuhn and Stoeckel2014; Streeck Reference Streeck2013). It has been argued that the response to the financial crisis in Europe did not benefit the usual benefactors of European integration, who in turn became less supportive of European integration. Historically, those who had the opportunity to benefit the most from European integration – the better educated and individuals with higher socioeconomic status – supported it the most (Gabel Reference Gabel1998; Gabel & Palmer Reference Gabel and Palmer1995; Kuhn & Stoeckel Reference Kuhn and Stoeckel2014). Simultaneously, the EU has, in response to the financial crisis, become more supranational, which has led to a decrease in support among citizens who care about the risk the EU poses to their identity (Kuhn & Stoeckel Reference Kuhn and Stoeckel2014). Armingeon and Ceka (Reference Armingeon and Ceka2014) argue that the crisis increased the proportion of those who are disillusioned with politics in general – whether European or national.

Individual attitudes towards the EU can influence attitudes towards sanctions in general in a number of ways. As sanctions represent a costly policy (exacerbated further by the budgetary squeeze in Member States), individuals who hold a negative view about European integration, because of its costliness, may hold negative views about the sanctions. Similarly, decisions about sanctions are taken at the supranational level and Member States have to comply with them. This places the EU's decision making directly at the heart of a foreign policy dispute. Individuals may oppose the sanctions because they strengthen European foreign policy at the expense of national foreign policies. At the same time, citizens with a positive evaluation of the EU are already more likely to appreciate supranational responses to complex issues abroad, and may be more likely to support multilateral sanctions. Therefore, it is hypothesised:

H1: The higher the individual support for the EU, the higher the support for the sanctions.

The second hypothesised geopolitical factor influencing attitudes towards sanctions is anti‐Americanism. The opposition to American unipolarity, including the expansion of NATO and missile defence, which Vladimir Putin denounced at the Munich Security Conference in 2007 (Putin Reference Putin2007), has been described as Moscow's main source of concern. Indeed, Moscow has positioned itself in opposition to Washington and argued that it is not Russia, but the United States, that has attempted to re‐draw spheres of influence in Europe. Here, Putin's defences tap into anti‐Americanism in Europe, widespread also in the countries that are formally allied with the United States (Katzenstein & Keohane Reference Katzenstein and Keohane2007; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Lobell and Jesse2012). Russia attempts to portray its actions as being opposed to the United States which reshaped unilaterally its own sphere of influence (Allison Reference Allison2014). At the same time, the United States has, at times, also been seen as pushing the EU towards its own sanctions on Russia. European politicians, including the Commission President Juncker, have argued that the EU should develop a different approach from that of the United States, which emphasises sanctions and isolation. ‘We can't let our relationship with Russia be dictated by Washington’, Juncker has said (EurActiv 2015). This would not be the first time that anti‐Americanism has influenced how Europeans feel about world politics. Earlier research demonstrated that anti‐Americanism was a dominant feature responsible for shaping Europeans’ attitudes towards the war in Iraq (Everts & Isernia Reference Everts and Isernia2015; Isernia Reference Isernia and Fabbrini2005). The fiasco in Iraq led to even higher scepticism about American power among the European publics.

One of the main reasons why individuals hold negative views of the United States is because the country is seen as overbearing and hypocritical (Johnston & Stockmann Reference Johnston, Stockmann, Katzenstein and Keohane2007; Katzenstein & Keohane Reference Katzenstein and Keohane2007). Individuals with such views may reject the sanctions because they see them as a predominantly American strategy of dominance to bring another country into the fold. On the other hand, individuals with pro‐American views are more likely to see the benefits of American influence in the world. Seeing Russia as countering that influence (even using military force), individuals may support the use of sanctions.

H2: The more positive the individual view of the United States, the higher the support for sanctions.

Endogeneity concerns

Both Euroscepticism and anti‐Americanism may be due to other variables – in methodological language, they may suffer from endogeneity. Attitudes towards the United States can be conditioned by attitudes towards Russia. Using the old Cold War logic, individuals with a negative view of the United States may hold a positive view of Russia (and vice‐versa). Therefore, one may need to control for attitudes towards Russia.

Similarly, part of the anti‐Americanism in Europe is due to opposition to American militarism. Kagan (Reference Kagan2002: 10) famously argued that Americans are from Mars and Europeans are from Venus, and ‘Europe's military weakness has produced a perfectly understandable aversion to the exercise of military power’. It therefore makes sense to control for militarism among Europeans when studying attitudes towards the United States.

Finally, yet importantly, individuals’ opinion of foreign policy (such as relations with the EU, the United States, Russia, or sanctions) may depend on attitudes the individuals hold towards their own government. Individuals who distrust their government tend to develop views critical of the country's existing foreign policy (Baum & Nau Reference Baum and Nau2012) and be more critical of European integration (Armingeon & Ceka Reference Armingeon and Ceka2014). Similar results were found outside the EU, too: citizens trusting their government tend to have more positive attitudes towards regional cooperation (Schlipphak Reference Schlipphak2014). Trust in national government is therefore potentially endogenous and needs to be taken into account.

Economic factors

The theory of economic liberalism argues that bilateral trade mitigates the propensity of the two states to engage in war (Nye Reference Nye1988; Russett & Oneal Reference Russett and Oneal2001). Particularly in democracies, the fear of loss from trade should prevent the countries from adopting confrontationist policies because they are likely to restrict economic welfare (Gelpi & Grieco Reference Gelpi, Grieco, Mansfield and Pollins2003, Reference Gelpi and Grieco2008; Papayoanou Reference Papayoanou1996). Liberals have argued for a long time that commercial exchange leads to the establishment of security communities through peaceful exchange; social transactions happen, which fosters mutual responsiveness and develops trust (Deutsch et al. Reference Deutsch1957; Russett & Oneal Reference Russett and Oneal2001). As Buzan (Reference Buzan1993: 341) argues, ‘trade automatically creates pressures for codes of conduct that facilitate the process of exchange and protect those engaged in it’. Wendt (Reference Wendt1999) argues that economic interdependence is one of the ways to shape identity and influence state preferences. Given that sanctions function similarly to conflict as they impact bilateral trade flows and decrease general welfare (Hufbauer et al. Reference Hufbauer1997), and that this is more strongly the case as the scope of sanctions increases (Caruso Reference Caruso2003), we can foresee that the influence of trade on sanction attitudes will be similar.

It may be therefore hypothesised that the higher the bilateral trade between Russia and any given country, the less supportive of sanctions the citizens of that country will be. In fact, the estimates made by the Austrian Institute of Economic Research in Vienna put the cost of sanctions at the ballpark figure of €100 billion, and sanctions are expected to threaten 2 million jobs in Europe (Eigendorf et al. Reference Eigendorf2015). Countries with strong relative economic ties with Russia, such as Slovakia and Italy, have been calling on the EU to lift sanctions (Gaffey Reference Gaffey2015).

H3: The larger the bilateral trade between an individual's country and Russia, the less support there is for sanctions.

A secondary way in which economic factors can influence support for sanctions is individual economic well‐being. Among Western Europeans, the financial crisis which started in 2008 and the subsequent crises provided a most costly economic condition. Austerity measures, adopted in the wake of the crises, have squeezed Europeans’ welfare and led to widespread dissatisfaction. It has been argued that expansion of trade is needed for Europe's economic recovery. If the sanctions on Russia are seen as economically damaging (as has been already argued above), then individuals may reject them because the sanctions are seen as further squeezing those already burdened by the impact of the financial crisis.

H4: Individuals in the countries hit by the crisis will be less willing to support financial sanctions.

Ideational factors

A growing body of literature argues that foreign relations have become an aspect of domestic contestation (and hence politicised) and that politics doesn't end ‘at the water's edge’ (Ecker‐Ehrhardt Reference Ecker‐Ehrhardt2012; Kriesi Reference Kriesi2016; Milner & Tingley Reference Milner and Tingley2015; Zürn Reference Zürn2014). Existing work, focusing on the role of political partisanship, has demonstrated that right‐wing governments are more likely to initiate disputes (Arena & Palmer Reference Arena and Palmer2009; Palmer et al. Reference Palmer, London and Regan2004). On the other hand, Mello (Reference Mello2014) has found that left‐wing parties have consistently abstained from the Iraq War.

Rathbun (Reference Rathbun2004) and Schuster and Maier (Reference Schuster and Maier2006) have shown that left‐wing governments prefer non‐violent settlement of disputes and conflict resolution. This can be extended to the study of individual preferences for sanctions. If left‐wing parties are more likely to support non‐violent means of conflict resolution, then individuals with left‐wing beliefs should be more likely to also oppose the use of sanctions, whereas those on the right should be more likely to be in favour of the sanctions.

H5: Individuals with right‐wing views are more likely to support sanctions compared to those with left‐wing views.

At the same time, we should also consider other aspects of national culture beyond partisanship. Early scholars of sanctions have noted that ‘the desire to punish will always be an integral factor in their imposition’ (Nossal Reference Nossal1989: 320). Other scholars have argued that indeed, punishment and isolation are the correct way to interpret the purpose of the EU sanctions (Giumelli Reference Giumelli2013a). This is in line with the criminological literature, which underlines that punishment is a society's way of sharing the victim's suffering and discouraging others from committing similar actions (Banks Reference Banks2013).

Building on insights from liberal constructivism that studies how domestic norms are applied in foreign policy (Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein1978; Risse et al. Reference Risse1999), existing research has shown that domestic ways of dealing with norm‐breaking have an important influence on how states deal with norm‐breaking internationally. Criminologists have argued that countries vary in the way they deal with norm‐breaking. The variation in those responses can be placed on a continuum from rehabilitative to exclusionary cultures (Garland Reference Garland2001). Rehabilitative cultures highlight that social engineering can prevent crime, and that the individual offender needs to be understood (including their motivation) so that future norm‐breaking can be prevented. On the other hand, exclusionary culture originates in understanding that the punishment for crime is just and deserved. Norm‐breakers are seen as different by their very nature, and therefore sympathising with them – as suggested and argued by the proponents of the rehabilitative culture – is seen as inacceptable.

Previous research has shown that countries with punitive domestic criminal systems are more likely to be confrontationist towards countries breaking international norms (Wagner Reference Wagner, Wagner, Werner and Onderco2014; Wagner & Onderco Reference Wagner and Onderco2014), and that democracies still exercising the death penalty are more likely to engage in militarised interstate disputes (Stein Reference Stein2015). Similarly, support for the death penalty has been associated with higher support for war in Iraq or for the torture of terrorism suspects (Liberman Reference Liberman2006, Reference Liberman2007, Reference Liberman2013).

It may therefore be hypothesised that individuals from EU Member States with more punitive domestic cultures of dealing with norm deviance will be more likely to support the imposition of sanctions against Russia; whereas individuals from EU countries with a more rehabilitative culture of dealing with norm deviance will be more likely to oppose the imposition of sanctions.

H6: The more punitive the domestic culture of dealing with norm‐breaking, the higher the likelihood of supporting sanctions against Russia.

Methods and data

A question can be raised whether insights from an inquiry into public opinion on sanctions on Russia are generalisable to the whole population of sanctions cases. In some way, every sanctions episode is a unique one, and questions about whether comparative study of sanctions is possible have been around since the advent of the field (see Eriksson Reference Eriksson2010). As Eckert et al. (Reference Eckert, Biersteker and Tourinho2016: 10) note in the context of the UN, ‘each sanctions case is unique with incomparably complex dynamics’, and over‐generalisations are possible. At the same time, the debate about the utility of sanctions against Russia is not too dissimilar to the debates about the utility of sanctions against Iran, or North Korea, or Belarus. Studying the case of sanctions on Russia provides a mixed blessing in this respect. While sanctions on Russia provide a case with a high enough profile that the public has a chance to make up its mind (which may not be the case when sanctions on Belarus are discussed, for example), an individual's choice may be influenced by other considerations, which is why the model used in this study controls for additional variables.

The data for this article comes from the TTS, conducted by Taylor Nelson Sofres (German Marshall Fund of the United States/Compagnia di San Paolo di Torino 2014). TTS is an annual survey of public opinion in selected countries, and asks respondents a series of questions related to international security. The survey is used widely in academic and policy literature to study public opinion towards issues of international security (Everts & Isernia Reference Everts and Isernia2015; Everts et al. Reference Everts, Isernia and Olmastroni2014; Faust & Garcia Reference Faust and Garcia2014; Isernia Reference Isernia and Fabbrini2005). The data for this article comes from the 2014 wave, completed in June 2014, and covers ten European countries (France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom), with a sample size of approximately 1,000 per country.

Dependent variable

The support for sanctions against Russia is measured by a question asked within a battery of questions about the crisis in Ukraine. The survey asked respondents: ‘There have been a number of proposals for how (the EU/USA) should react to Russian actions on Ukraine. For each of the following, please tell me if you agree or disagree with the proposed actions – Impose stronger economic sanctions on Russia.’Footnote 1 The respondents could answer by choosing from a four‐point Likert scale ranging from ‘Disagree strongly’ to ‘Agree strongly’.Footnote 2 As stated above, the question was asked at a time when the sanctions against Russia were limited in scope and included only travel bans and asset freezes against 33 individuals (Council of the European Union2014). Additional sanctions were not adopted in the EU until July 2014.

The high‐profile case limits the generalisability of insights from the present analysis. Despite controlling for possible endogenous factors, it is possible that the attitudes towards sanctions against Russia stand out from general attitudes towards sanctions. Despite the tests reported in Endnote 1, the present data provides only a limited study to explain more generally individual attitudes towards all (or any) sanctions regimes established by the EU. The highly‐publicised nature may provide a scope condition for the argument. Further research should address this shortcoming.

Independent variables

Geopolitical factors

Measuring Euroscepticism is not easy. In this study, I make use of a survey item asking the respondents to answer the question ‘Please tell me if you have a very favourable, somewhat favourable, somewhat unfavourable or very unfavourable opinion of the European Union?’, with the answers being reversely recoded from ‘Very unfavourable’ to ‘Very favourable’. This question seems to capture directly individual attitudes towards the EU.Footnote 3 With the exception of Greece, in all countries a larger part of the population held a favourable or somewhat favourable view of the EU.

Similarly, anti‐Americanism has been measured by the question ‘Please tell me if you have a very favourable, somewhat favourable, somewhat unfavourable or very unfavourable opinion of the United States?’. Previous research has shown that this wording of a question is a reliable and valid way of capturing attitudes towards the United States and measuring anti‐Americanism in particular (Isernia Reference Isernia and Fabbrini2005). Again, in all countries except for Greece, more than 50 per cent of the population held a (somewhat) favourable view of the United States.

Addressing endogeneityFootnote 4

As discussed above, Euroscepticism and anti‐Americanism may suffer from endogeneity. To address the possible endogeneity, I control for a number of variables. To control for the attitudes towards Russia, I look at the answer to the question ‘Please tell me if you have a very favourable, somewhat favourable, somewhat unfavourable or very unfavourable opinion of Russia?’. The data has been reversely recoded. To capture militarism among Europeans, it is useful to look for readiness to use military power in other situations. Iran's nuclear programme, and the chance of using force against it, has been high on the agenda, as well as many discussions about the utility of such a strike. To capture general militarism, I look at whether the respondent chose ‘favoured using force against Iran’.Footnote 5 To capture the level of trust in national government, I look at the responses to the question ‘Do you approve or disapprove of the way [COUNTRY'S] government is handling international policies?’, which included ‘Approve very much’, ‘Approve somewhat’, ‘Disapprove somewhat’ and ‘Disapprove very much’.

Economic factors

Bilateral trade between each country and Russia is measured as the total of imports and exports between the two countries as a share of each country's total trade. The data is taken for 2013 from UN COMTRADE (2014). Individual economic experience of crisis has been measured with a survey question asking ‘And regarding to the extent to which of you or your family has been personally affected by the current economic crisis, would you say that your family's financial situation has been …’, with answer possibilities including ‘Greatly affected’, ‘Somewhat affected’, ‘Not really affected’ and ‘Not affected at all’.

Ideational factors

Partisanship is measured with the help of a survey item that asked the respondents ‘In politics, people sometimes talk of “left” and “right”. Where would you place yourself on a scale from 1 to 7, where “1” means the extreme left and “7”means the extreme right?’. The domestic culture of dealing with norm‐breaking is measured by prison population per 1,000 inhabitants. A high relative prison population indicates that the country's criminal law privileges exclusion over re‐integration. Prison population is a better measure than, for example, retention of the death penalty. The death penalty is retained only by a few countries (and none in the EU), and is therefore too crude an indicator. As criminologists have argued, prison populations ‘are largely unrelated to victimization rates or to trends in reported crime’ (Lappi‐Seppälä Reference Lappi‐Seppälä2011: 308), and is ‘a matter of political choice’ (Morgan & Liebling Reference Morgan, Liebling, Maguire, Morgan and Reiner2007: 1107). The data has been obtained for the year 2014 from Walmsley (Reference Walmsley2016).

In addition to the variables described above, I control for education, age and gender. Individuals with higher education have been found to be more in favour of free trade, and therefore may be expected to be opposed to sanctions as a tool that limits trade (Hainmueller & Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2006). Women have been found to be more opposed to military action and other confrontationist moves, as well as more ‘sensitive to humanitarian objectives’ (Eichenberg Reference Eichenberg2003: 137).

Model

Four models are estimated using logistic models using both individual‐ and country‐level data, with standard errors clustered at the country level. The data on bilateral trade with Russia and on the domestic culture of dealing with deviance are measured at the national level; all other variables are measured at the individual level. In the analysis, individuals are nested within countries, making the data purely hierarchical.

The first model estimates a logit model using individual‐level variables with country fixed effects to control for country‐level variation. The second model replicates the first, but controlling for the variables discussed above as potentially endogenous. The third model uses a hierarchical logistical model to estimate the effect of trade with Russia; whereas the fourth model uses the same method but estimates the effect of the domestic culture of dealing with deviance. I split these two because the small number of country clusters (only ten) makes it almost impossible to make any statements about country‐level factors if multiple variables are used simultaneously.

Results

Before inspecting the quantitative models, it is worthwhile to look at the distribution of support for stronger sanctions against Russia. As Figure 1 demonstrates, there is a wide variation between individual countries in popular support for sanctions on Russia. The two countries with the lowest support for sanctions on Russia are Greece, where only 35 per cent of the population supports stronger sanctions on Russia; and Germany, where 46 per cent of the population supports further sanctions. On the other hand, in Sweden and Spain, 73 per cent of the population supports further sanctions, while the proportion rises to 83 per cent in Poland.

Figure 1. Agreement with imposition of sanctions on Russia.

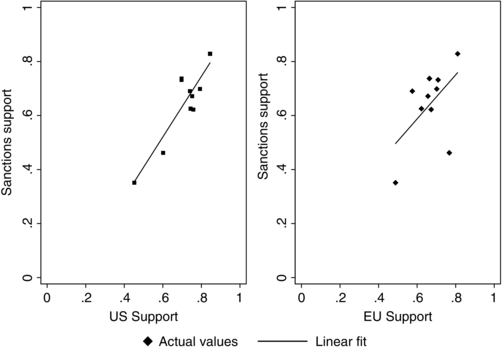

Figure 2 shows the bivariate relationship between the geopolitical variables attitude towards the United States and the EU and support for the sanctions on Russia at the national level. For presentational purposes, I look at dichotomised versions of variables related to the support for sanctions, as well as variables related to opinion about the EU/US. The individual dots represent national shares of supporting sanctions or holding a favourable opinion about the EU/US. As can be seen, there is a very strong bivariate relationship between having a positive view of either the European Union or the United States and supporting sanctions.

Figure 2. Support for United States/European Union and sanctions.

Note: Actual values plotted represent national averages.

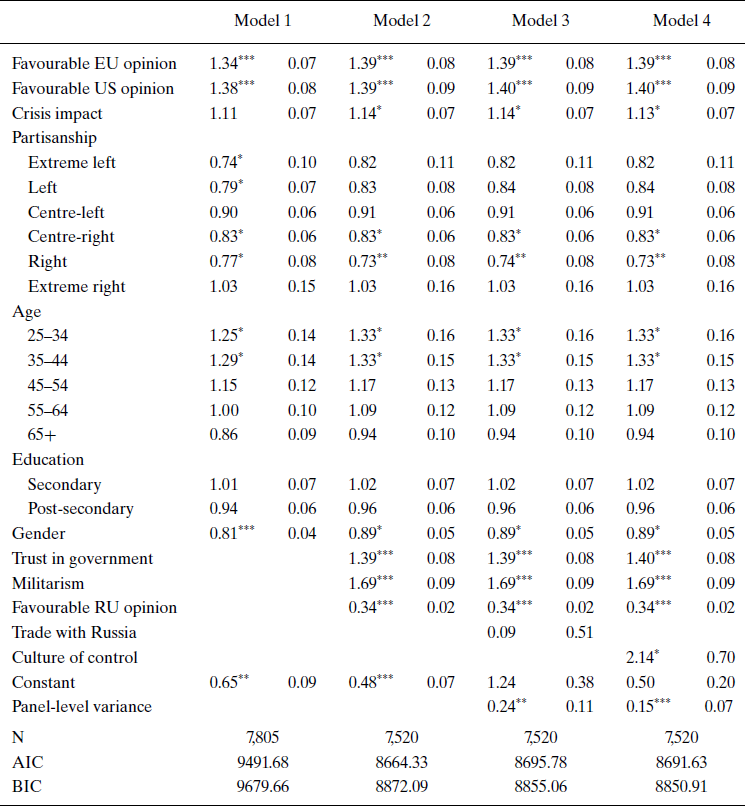

Moving to multivariate statistics, as expected, those with positive views of the EU are more likely to support the sanctions on Russia, confirming thus the first hypothesis (Table 1). Individuals with a positive view of the EU are up to 39 per cent more likely to support sanctions against Russia, ceteris paribus. The second hypothesis is also confirmed: individuals with a positive view of the United States are much more likely to support sanctions. Looking at the tests using all four levels of response (reported in the Online Appendix), an interesting phenomenon emerges: whereas there is no statistically distinguishable difference between individuals with a very negative and somewhat negative view of the EU, in the case of the United States, all three levels of the variable are statistically significant. This suggests that there is a very strong difference between those holding strongly unfavourable, anti‐American views and the rest of the population. Even controlling for other factors that may be endogenous to the relationship between the geopolitical variables and support for sanctions does not diminish the effect. Expectedly, individuals who trust the government with foreign policy are more likely to support the sanctions against Russia. Similarly, individual militarism is related to the support for sanctions. Finally, as expected, individuals with a positive view of Russia are significantly less likely to support the use of sanctions (about 66 percentage points, ceteris paribus).

Table 1. Results of quantitative analysis

Notes: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Standard errors reported in the second column. Reference categories: partisanship (Centre), age (18–24), education (Primary); gender (Female). Country fixed effects not reported for brevity. Exponentiated coefficients reported.

Moving on to the economic factors, the individual experience of the crisis had only a weak effect on the support for sanctioning Russia. This curious result, combined with no statistically significant effect of the trade with Russia, can be interpreted individuals not considering the impact of sanctions on their economic wellbeing as being too strong (or not considering it all all). Individuals may be generally unaware of the trade sensitivity towards other countries, or do not consider it as a limitation on foreign policy.

When it comes to the ideational factors, H5 is only partially and weakly confirmed: compared to those with centrist views, those with left‐wing views and right‐wing views are less likely to support sanctions, but the effect is not statistically distinguishable at all levels and is rather weak. Interestingly enough, individuals who identify themselves as to be on the ‘right’ are rather strongly opposed to sanctions; they are up to 27 percentage points less likely to support sanctions, ceteris paribus. The weak effect on the left may be due to the fact that effect of partisanship is more nuanced than earlier theorised, and needs to be studied further.Footnote 6 Individuals from countries with more punitive domestic cultures are more likely to support sanctions against Russia. This not only confirms the results of the earlier research, but also suggests that the analogous thinking about responses to norm‐breaking domestically and internationally is likely. The result also confirms previous research by Liberman (Reference Liberman2013, Reference Liberman2014) and Onderco and Wagner (Reference Onderco and Wagner2015). Wagner and Onderco (Reference Wagner and Onderco2014) also found that domestic punitivity is related to the likelihood of support for punitive action internationally. While the survey data do not permit further analysis, the result underlines the need for further research into individuals’ drivers of punitivity in Europe, where research is still in its infancy.

As for the other control variables, the results are mixed. Younger individuals aged between 25 and 44 seem to be more in favour of sanctions. The effect of education is not statistically significant, but men tend to be statistically significantly less likely to support sanctions.

Conclusion

This article set out to explain the variation among Europeans’ attitudes towards sanctions on Russia. As sanctions have gradually become the predominant tool in the EU's foreign policy toolbox, exploring public attitudes towards them has become an obvious but overlooked lacuna in the EU foreign relations scholarship. While the earlier scholarship has amply focused on the impact and success of the EU's sanctions (Dreyer & Luengo‐Cabrera Reference Dreyer and Luengo‐Cabrera2015; Giumelli Reference Giumelli2013a; Portela Reference Portela2014), the attitudes of the population towards this tool of foreign policy has been overlooked. This is curious as the existing scholarship studied attitudes towards other tools of the EU's foreign policy, including military cooperation (Irondelle et al. Reference Irondelle, Mérand and Foucault2015) and democracy promotion (Faust & Garcia Reference Faust and Garcia2014).

I have proposed that the attitudes towards sanctions can be shaped by geopolitical, economic and ideational factors. Geopolitical factors under study included Euroscepticism and anti‐Americanism. The result of the multivariate analysis confirms this expectation: individual attitudes towards the EU and the United States do influence support for sanctions. This result is important as it suggests that Europeans, despite the charges of having ‘forgotten’ geopolitics and being focused on their material well‐being, consider the geopolitical actors who promote sanctions. This result also suggests that individuals are more likely to support sanctions if they see the EU or the United States more positively, but sanctions against Russia are opposed by those who hold Eurosceptic or anti‐American views. As the new Eurosceptic parties are distinguished by their rather positive view of the Kremlin, the result is not so surprising. This result also suggests that the impact of Euroscepticism goes beyond the narrow remit of the evaluation of the EU: if the EU is the symbol for supranationalism, then Euroscepticism can be reasonably expected to influence other areas of supranational cooperation.

Economic factors matter, surprisingly, very little; the exposure to economic crisis does not influence the support for sanctions, as is the case with bilateral trade. In the case of the ideational factors, the situation is more mixed: partisanship is not strongly related to any position on sanctions. But the national culture of dealing with deviance matters. Individuals from countries that are more punitive towards norm‐breakers are more likely to support the use of stronger sanctions against Russia.

These findings open new avenues for future research. The case of sanctions against Russia provides a high‐profile sanctions episode, which is a mixed blessing. On the one hand, individuals have an better chance to create an opinion. On the other hand, the factors that shape attitudes towards such a high‐profile case may not explain attitudes towards the whole universe of EU sanctions episodes. Given the increasing politicisation and contestation of foreign policy in Europe (Ecker‐Ehrhardt Reference Ecker‐Ehrhardt2012; Kriesi Reference Kriesi2016; Zürn Reference Zürn2014), studying the structure of underlying conflicts will be important for future research. As economic statecraft tools in Europe (such as the currently negotiated TTIP agreement, or indeed other sanctions regimes) are becoming an object of domestic political struggle, we need to understand more about what motivates individual attitudes. Furthermore, the research also needs to look at the further effects of Euroscepticism and anti‐Americanism in Europe, as well as the dynamics of development of these phenomena. The results of this study suggest that their influence for European politics may be wider than previously thought.

Acknowledgements

The author is thankful to the EJPR’s reviewers, Brian Burgoon, Ursula Daxacker, Philip Everts, Markus Haverland, Falk Ostermann and Paul van Hooft for helpful comments on earlier drafts of the article. Initial thoughts that underpin this article were presented at the workshop ‘National Perspectives on the Ukraine Crisis’ in December 2015 in Kyiv, organised by the DAAD team of the National University of Kyiv‐Mohyla Academy's Political Science Department in cooperation with Friedrich‐Schiller‐Universität Jena. I thank the workshop's attendees, and in particular the discussant André Härtel, for their excellent suggestions. Ashley‐Richard Longman proofread the manuscript with much care. All mistakes remain my own.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site:

Online appendix A: Replication of Models 1–4 with all four levels of response