Introduction

Normative theories of participatory democracy envision deeply participatory societies, in which every sphere of life is infused with democratic principles and practices (Pateman, Reference Pateman1970; Barber, Reference Barber2003 [Reference De Certeau1984]). Beyond institutionalized participatory processes such as participatory budgeting, a participatory democracy entails an engaged civic culture that engenders bottom-up initiatives, community organizing and social movement action (Dzur, Reference Dzur2019; Bua and Bussu, Reference Bua and Bussu2023). Participatory democrats go even further when they claim that “democratic ideals and politics have to be put into practice in the kitchen, the nursery and the bedroom” (Pateman, Reference Pateman1989: 222). Participation itself is understood as a normative ideal (Dacombe, Reference Dacombe2018). This ideal is rooted in and driven by a broader vision of social justice, as the pursuit of an equitable society ensuring equal rights and opportunities, as well as positive freedoms underpinned by social and economic resources. Thus, participatory democracy requires approaching socio-economic equality as a prerequisite for meaningful democratic participation (Pateman, Reference Pateman2004; Torres, Reference Torres, O’Donnell, Pryin and Chavez-Chavez2004).

However, despite a particular focus on participation in the workplace and in educational settings, participatory democrats have rarely confronted the question of how democratic principles can be realized in their research and knowledge creation processes. This has led to neglecting or overlooking how knowledge hierarchies in participatory democrats’ everyday research, design and theorizing practices might exclude or silence marginalized groups’ diverse understandings of what an inclusive society entails. In other words, while participatory democrats aim to realize social justice, epistemic justice (Fricker, Reference Fricker2007), which recognizes the equal value and credibility of different, and in particular marginalized, sources of knowledge, is seldom addressed. Although participatory democracy research does indeed propose to empower citizens, it does not always understand them as equal knowledge creators and credible knowers.

The field of participatory research, in contrast, underscores epistemic justice. It has developed a wide range of research approaches and methods that help center participants’ experience and foster their knowledge creation capacity (Fals Borda, Reference Fals Borda1987; Bergold and Thomas, Reference Bergold and Thomas2012; Aldridge, Reference Aldridge2017). Participants are active agents in the research process, which becomes a democratic space for knowledge co-creation, whether using traditional or more creative methods, such as empathy mapping, storyboarding and photo reporting, as well as artistic expressions through poetry, music and theater (Boal, Reference Boal1998; Crockett Thomas et al., Reference Crockett Thomas, Collinson Scott, McNeill, Escobar, Cathcart Frödén and Urie2020; Mullally et al., Reference Mullally2022).

While participatory research strives to realize democratic principles within a specific research project, its emancipatory reach often remains restricted by funding cycles and research protocols that can curb genuine democratic experimentation. Particularly within the Global North, where it has sometimes been rebranded as “co-production of knowledge,” participatory research has become entangled in the logics of market economies and the neoliberal university (Bell and Pahl, Reference Bell and Kate2018). In this respect, participatory research might need to rekindle its normative democratic underpinning of social justice to move from one-off micro-projects towards a broader transformative vision of a participatory society, strengthening connectivity and collective action within a participatory polity.

Recent studies bringing together participatory democracy with participatory research have focused on individual cases such as, participatory research on participatory budgeting in New York City (Kasdan and Markman, Reference Kasdan and Markman2017), participatory research on a global participatory democracy-promoting civil society organization (Hagelskamp et al., Reference Hagelskamp, Celina, Karla and Tarson2022), and participatory democratic theorizing with the Black Lives Matter movement (Asenbaum et al., Reference Asenbaum, Chenault, Harris, Hassan, Hierro, Houldsworth, Mack, Martin, Newsome, Reed, Rice, Torres and II, Terry J.2023). Our paper contributes to this debate by setting a broader agenda. We advocate for bringing the normative debates of participatory democracy, underpinned by an ideal of social justice and the methodological practices of participatory research orientated toward epistemic justice, in closer dialogue to strengthen and deepen democratic renewal.

We are four participatory democracy scholars at different academic institutions in the Global North. In our respective work, we aim, each in a different way, to combine normative ideals of participatory democracy with participatory research methods. In this paper, we draw together our experiences from three participatory research projects that attempt and struggle to realize participatory democratic ideals within the neoliberal contexts of Global North academia. We reflect on strategies to navigate some of these structural barriers to realize social and epistemic justice. We acknowledge that the gap we identify is particularly evident in Global North academia, while debates in the Majority World have been ongoing for several decades (e.g., Boal, Reference Boal1998; Fals Borda, Reference Fals Borda1987).

In what follows, we first bring into dialogue normative theories of participatory democracy with a focus on social justice and participatory research practice with a focus on epistemic justice, reflecting on their affordances and limitations, and on what each field can learn from the other. Next we illustrate this intersection by presenting three projects that attempt to reconcile participatory democracy and participatory research. These projects, in which some of the authors were involved, illustrate how social justice and epistemic justice are both intrinsic to inclusive visions of democracy and how they can be realized by generating societal rooting, societal impact and societal vision. We then reflect on the opportunities and challenges facing participatory research that supports participatory democracy through alliances between scholars, practitioners, activists and citizens working within, against and beyond the neoliberal order (Bell and Pahl, Reference Bell and Kate2018) that has already partly co-opted ideals of participatory research and democratic innovation (Lee, Reference Lee2014).

Participatory democracy and participatory research: Sharing learnings across two perspectives

Participatory democracy: toward social justice

Theories of participatory democracy that emerged in the 1960s are experiencing a revival today (Hilmer, Reference Hilmer2010; Polletta, Reference Polletta2014; Dacombe, Reference Dacombe2018; Dzur, Reference Dzur2019; Wojciechowska, Reference Wojciechowska2019; Holdo, Reference Holdo2024). In the pursuit of a larger vision of social justice, they situate the intrinsic value of participation at their core. With contemporary roots in Dewey’s work (Reference Dewey1927) inspiring a vision of democracy that strives for deep structural transformations, participatory democrats aim to realize democracy’s unfulfilled promise of popular self-government. In contrast to elite-driven conceptions of liberal democracy confined to institutional arrangements, in participatory democracy political engagement becomes an everyday practice in a variety of participatory spaces including worker-own businesses and self-managed workplaces (Dahl, Reference Dahl1986; Gould, Reference Gould1988), neighborhood associations (Barber, Reference Barber2003 [Reference De Certeau1984]), participatory parties (Macpherson, Reference Macpherson1977), social movements (Polletta, Reference Polletta2002; della Porta, Reference della Porta2020), educational facilities and public services (Hirst, Reference Hirst1994; Smith and Teasdale, Reference Smith and Teasdale.2012), and the criminal justice system (Dzur, Reference Dzur2019). These participatory spaces function as “schools of democracy” that afford empowerment and personal development (Pateman, Reference Pateman1970).

A rich and growing field of democratic innovation (Elstub and Escobar, Reference Elstub and Escobar2019) has developed over the last three decades bridging participatory and deliberative democracy (Floridia, Reference Floridia2017). Democratic innovations have the ambition to strengthen citizens’ role in governing and often advancing social justice through a more equitable resource distribution (Wampler and Touchton, Reference Wampler and Touchton2018). Recent literature and practice stress the structural nature of inequalities and the systemic form a participatory response needs to take to further social justice (Bussu, Reference Bussu, Elstub and Escobar2019). Citizen participation, according to this argument, requires institutionalization to tackle structural oppression in a sustainable manner (Pateman, Reference Pateman2012).

Theories of participatory democracy increasingly recognize the limits of focusing inordinately on institutional design, at the expense of paying sufficient attention to how new participatory institutions, such as citizens’ assemblies or participatory budgets, function within existing political and socio-economic contexts. Participatory institutions can sometimes have a limited impact on policy change. They can be prone to cooptation, or bypass and even alienate civil society and grassroots action, and in so doing depoliticize participation (Lee, Reference Lee2014; Johnson, Reference Johnson2015; Asenbaum and Hanusch, Reference Asenbaum and Hanusch2021; Hammond, Reference Hammond2021; Holdo, Reference Holdo2024).

Bussu, Bua, Dean and Smith (Reference Bussu, Bua, Dean and Smith2022: 141) propose the concept of embeddedness to assess to which degree participatory processes work productively with other state and non-state institutions. Embeddedness encourages scholars and practitioners to move beyond participatory initiatives as mere add-on institutional designs that serve to support and/or legitimize liberal democracy. Instead, embedding participation requires greater attention to ways of fostering a participatory culture in policymaking in wider society that can open space for challenging rather than reinforcing the status quo. In this respect, social movements and civil society actors can play a crucial role in reclaiming a more ambitious role for participatory democracy as a way of furthering social justice (Bua and Bussu, Reference Bua and Bussu2023).

Reflecting on the participatory ideal articulated in her work four decades earlier, Pateman (Reference Pateman2012) critically distanced participatory democracy from deliberative democracy, arguing that the latter often overlooks structural socio-economic barriers to participation. She stressed the need for socio-economic equality as a precondition for democratic participation (Pateman, Reference Pateman1970: 43), for instance, through universal basic income (Pateman, Reference Pateman2004), and an extensive, multi-layered institutional infrastructure that secures participation as an ongoing experience of everyday life (Pateman, Reference Pateman2012). Pateman claims that this would mark a substantive structural alteration of capitalist power relations based on power sharing between citizens and elites (Pateman & Smith, Reference Pateman and Smith.2019).

Thus, participatory democracy’s ambition of furthering social justice is actualized not through static institutions, but through everyday democratic practice across different spaces – political arenas, as much as workplaces, schools, public squares and digital platforms – forming complex democratic ecologies embedded in everyday life (Escobar, Reference Escobar2017; Bussu, Reference Bussu, Elstub and Escobar2019; Asenbaum, Reference Asenbaum2022). Dzur (Reference Dzur2019) describes this as “civic Umwelt,” employing the German term for environment. Participatory democracy is not only a political but also a social activity of developing interpersonal relationships as “[c]ommunity grows out of participation and at the same time makes participation possible” (Barber, Reference Barber2003 [Reference De Certeau1984]: 152).

The focus on the structural nature of inequalities and the deep societal transformations needed to respond to these challenges engenders a substantive normative orientation toward social justice. However, participatory democracy often neglects epistemic justice. Participatory democrats aim to empower everyday citizens, but they do not necessarily recognize them as equal knowledge creators. Indeed, participatory processes are understood as a school of democracy in which citizens develop civic skills and acquire political knowledge (Pateman, Reference Pateman1970; Dacombe, Reference Dacombe2018), but this does not necessarily translate into the democratization of the conduct of academic research. This can result in the marginalization and suppression of diverse knowledges and ultimately in epistemic injustice (Fricker, Reference Fricker2007).

Participatory research: toward epistemic justice

Participatory research, in contrast, places emphasis on epistemic justice as the inclusion of marginalized or silenced knowledges. In participatory research, participation is a political as well as an epistemological imperative which affirms the basic human right of a person to contribute not only to decisions affecting them but also to knowledge concerning them (Reason and Torbert, Reference Reason and Torbert2001: 8). The focus on solving practical problems has the potential to produce social change, as well as personal development and learning for those involved, who can gain agency to affect and transform their own reality (Bussu et al., Reference Bussu, Lalani, Pattison and Marshall2021).

The literature has identified two main strands of participatory research, the “northern tradition” emerging in North America and the “southern tradition” emerging in South America. The former builds on the work of Kurt Lewin’s (1946) action research (AR). Epistemologically, AR is concerned with acting upon the world, as well as describing and explaining it (Reason & Bradbury, Reference Reason and Bradbury2008). Researchers’ and participants’ experiences and views inform an iterative cycle of (a) planning, (b) action and (c) evaluation, leading to further planning and so on (Reason & Torbert, Reference Reason and Torbert2001; McNiff & Whitehead, Reference McNiff and Whitehead.2011). Members of the community or group under study participate actively in this cyclical process of action and reflection, practice and theory (Greenwood and Levin, Reference Greenwood and Levin2007).

The “southern tradition,” based on conscientization and emancipatory education, was advanced by the work of Paulo Freire (Reference Freire1970) and Orlando Fals Borda (Reference Fals Borda1987). Building on Gramscian and Marxian theories, it emphasizes transformative learning and the empowering effects that participants experience through their engagement in the research process. Freire’s emancipatory focus underpins research approaches including Participatory Action Research (PAR), Empowerment Evaluation, Community-led Participatory Research, and decolonizing methodologies (Bozalek, Reference Bozalek2011). By challenging the very values informing research and education, emancipatory theory and practice question existing political power configurations and forms of oppression. In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire (Reference Freire1970) shifts the focus from an understanding of individuals as objects of inquiry to agentic participants in inquiry who can determine their own individual and collective needs, in order to transform their social context. Freire (Reference Freire1998) employs the concept of praxis to mean reflection and action on the world to transform it. Reflection without action is sheer verbalism or “armchair revolution” and action without reflection is action for action’s sake. For participatory research scholars following the Freirian tradition, the process of knowledge creation has profound repercussions on how we conceptualize our own selves and our place in the world, and how we understand our agency in processes of change. The democratization of knowledge creation through participatory research is therefore a crucial component of any democratization process and has genuine potential for radical transformation, as it provides a space to deconstruct and challenge existing societal hierarchies and the knowledge underpinning them, to realize epistemic justice.

However, participatory research is as important as it is challenging. A rich literature on its ethical dilemmas reflects on how established hierarchies of expertise and knowledge can be hard to subvert (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Armstrong, Carter, Graham, Hayward, Henry, Holland, Holmes, Lee, McNulty, Moore, Naylingk, Stokoe and Strachan.2013; Bussu et al., Reference Bussu, Lalani, Pattison and Marshall2021). Prioritizing community needs that do not align with academic career pressures and incentives can raise important challenges (Bell and Pahl, Reference Bell and Kate2018). There are concerns about ownership of the research process and results, whereby participants might feel exploited or stigmatized; boundaries between researchers and participants can become blurred, while pressures and aspirations of researchers and participants can still differ profoundly (Maiter et al., Reference Maiter, Simich, Jacobson and Wise2008).

Furthermore, participatory research is too often initiated by researchers with a predefined, rather than co-produced, epistemic agenda and this can lead to extractive practices. Participatory research projects thus might end up having a very specific output focus, missing the opportunity of allowing for longer-term community-led processes of knowledge (re)making that can unveil and address deep-seated and systemic injustices. Short term funding cycles can place stress on community resources, without providing sufficient space to build stable social capital. Bell and Pahl (Reference Bell and Kate2018: 107) warn of “neoliberalism’s attempts to capture and domesticate co-production’s utopian potential; and to the harms this will cause academia and the communities from which co-producers are drawn.”

Participatory research can draw learning from normative theories of participatory democracy and its grounding in social justice. Some of the more radical and resilient empirical cases, such as the Indian Gram Sabhas (Parthasarathy et al., Reference Parthasarathy, Rao and Palaniswamy.2019) or participatory budgeting (Baiocchi, Reference Baiocchi2005; Escobar, Reference Escobar, Loeffler and Bovaird2020), provide inspiration on how to address some of these dilemmas. Instead of being coopted by the neoliberal university and focusing on realizing democracy in small, discrete projects, participatory research can benefit from participatory democracy’s transformative orientation. Participatory democracy’s ambitious vision of structural transformation and embeddedness can encourage participatory researchers to link their practice more explicitly to wider projects that advance structural analysis and aim for systemic change to engender sustainable community-led change, as part of democratic transformations (Bussu, Reference Bussu, Elstub and Escobar2019; Asenbaum, Reference Asenbaum2023: Ch.7).

Participatory research meets participatory democracy: Three examples

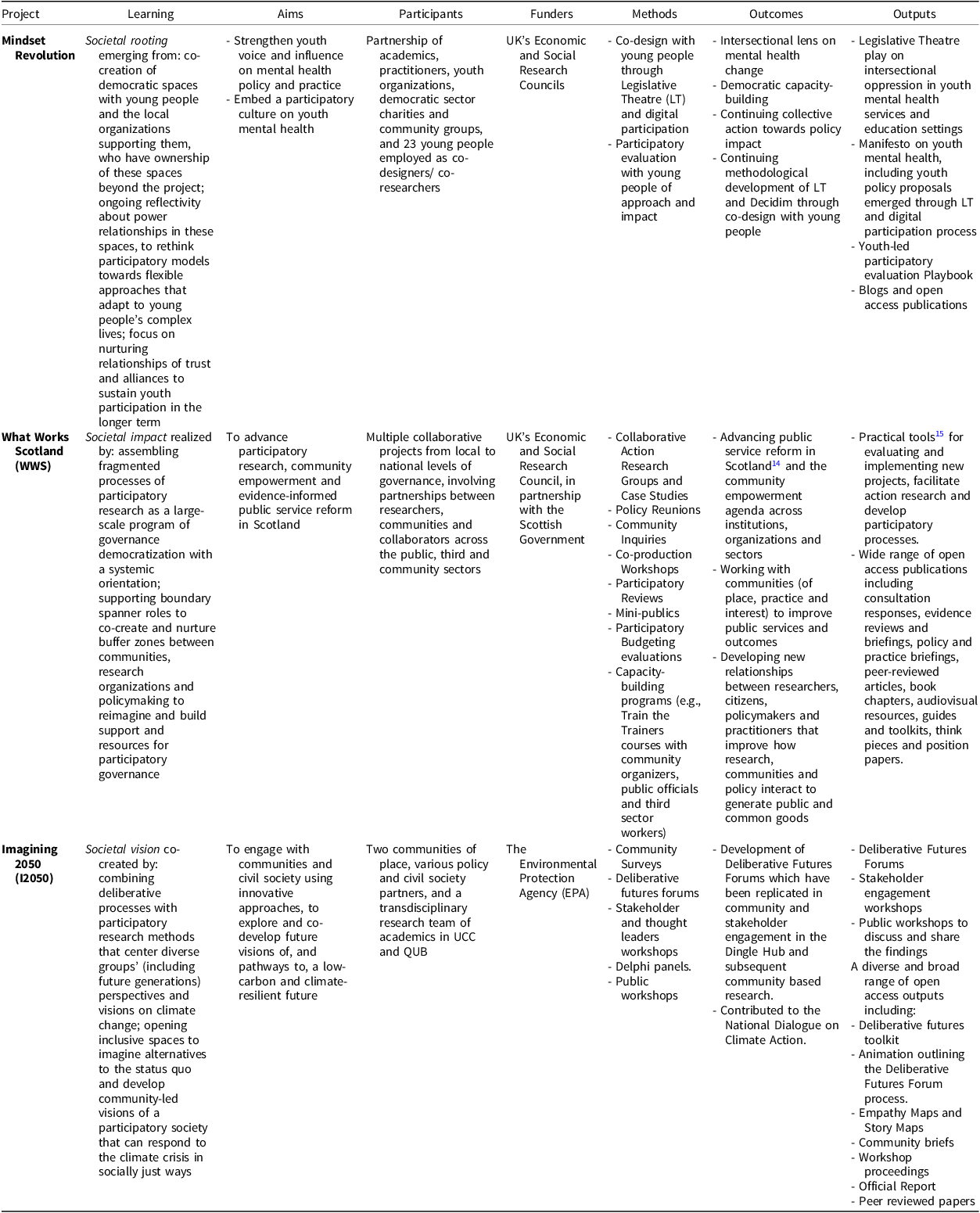

We now turn to three participatory research projects conducted by participatory democracy scholars in England, Scotland and Ireland (see Table 1 for an overview). These projects differ in terms of objectives, participants, outcomes and scale (local, regional and national). We draw on these examples not as empirical case studies but as vignettesFootnote 1 that illustrate how participatory democracy scholars can pursue participatory ambitions within their own research practice and enhance the epistemic justice underpinning their social justice projects. They also show how participatory research can embed itself within a broader vision of a participatory society.

Sonia Bussu was involved in “Mindset Revolution,” a participatory theater project aiming to strengthen youth voice on mental health in Greater Manchester; Oliver Escobar was involved in “What Works Scotland,” an action research project for participatory public service reform; and Clodagh Harris was involved in “Imagining 2050,” a community-led project developing visions and pathways for a climate-resilient society in Ireland.

Each example develops a different insight on how participatory democracy’s social justice agenda can be fruitfully combined with participatory research’s epistemic justice agenda: (a) societal rooting, (b) societal impact, and (c) societal vision.

Mindset revolution: societal rooting of youth voice on mental health in greater Manchester

Mindset Revolution (2022-23), funded by UK Research and Innovation and the Royal Society of Arts, rethinks youth participation by co-designing and co-evaluating participatory spaces with participants to better youth mental health. The project illustrates how, guided by ideals of participatory democracy, participatory research can create and foster societal rooting. By societal rooting we refer to practices of anchoring participatory processes in participants’ lived experiences, embedding them at the grassroots of societal networks and enhancing their bottom-up quality and sustainability. The project was led by a partnership including 23 young people (16–25 years old)Footnote 2 , who were paid as co-designers and co-researchers, academics, charities and community groups working on youth democracy and/or youth mental health. All young people had experience of mental illness and several lived complex lives as care leavers, single parents, unemployed, and/or immigrants. They formed three groups working on either creating a play on their experience of mental health using Legislative Theatre (Boal, Reference Boal1998)Footnote 3 ; designing and running a digital participatory process using the civic tech platform DecidimFootnote 4 ; evaluating their own and their peers’ experience of participation and social impact through participatory research and creative methods, including poetry, blogs and a podcast series (Bussu et al., Reference Bussu, Senabre Hidalgo, Schulbaum and Eve.2024; Bussu et al., Reference Bussu, Rubin, Carroll and Eve2025).

The ambition was to move away from participation as an ad hoc event and root it as a process anchored in the community through networks of local charities and grassroots groups. The aim was to incorporate youth voice into day-to-day policymaking and service delivery, fostering multiple opportunities for young people to participate in an open-ended dialogue with institutions and public services, but also their own communities.

Enabling participants’ agency in the process of co-design meant that participatory spaces were continuously reshaped to accommodate their different experiences and capacities for participation, whether in-person, online or hybrid. This approach to participation as an ecology of different spaces enhanced flexibility and inclusivity, as it ensured young people could participate in different ways and to different degrees at different points in the process, depending on their circumstances.

The young people were supported to co-design the participatory process on mental health, but also the measures to evaluate their own social impact and how learning from the project should influence future youth participation for social change. By embedding the participatory evaluation into the project from the start, through reflective group sessions, peer interviews, as well as creative methods such as spoken word poetry, drawing, blogs and anonymized podcast conversations, participants shared and examined their own experience of engagement. This developmental and participatory approach to evaluation helped the partnership to trace how the process changed and adapted to young people’s capacity for participation, while also drawing attention to individual and structural barriers to meaningful engagement and encouraging ongoing reflectivity on how to navigate them.

Democratic agency emerged through the relationships of trust among young people and between them and the adults in the partnership. These relationships generated new affordances that could potentially catalyze more meaningful and sustainable change than traditional top-down public dialogue formats. The participatory activities became opportunities for peer support, as young people reflected together on shared experiences of intersectional oppression and exclusion. This intersectional perspective informed the policy proposals to better youth mental health support co-created throughout the project.

The commitment to social and epistemic justice contributed to strengthening societal rooting, as it supported more stable alliances beyond the confines of one project. As the process now enters a new phase, several partners and young people continue to work together, using new funding tools to campaign for and monitor implementation of young people’s policy proposals. The young people are leading on the development of international alliances with other youth groups to strengthen intersectional inclusion and epistemic justice in mental health. This is also opening opportunities for further reflection with young people on approaches to youth participation to co-create ethical and non-extractive models.

What works Scotland: societal impact through participatory public service reform

What Works Scotland (WWS) (2014-2019) was a large program that included participatory action research to inform and advance public service reform in Scotland through “co-production, partnership and evidence-informed change” (Brunner et al., Reference Brunner, Bennett, Bynner and Henderson2018: 2). The project illustrates how participatory research, as part of participatory democracy scholarship, can generate concrete societal impact. Funded by the Economic and Social Research Council and the Scottish Government, the program generated dozens of projects, studies, training courses, resources and participatory processes, documented in over 100 open access publicationsFootnote 5 . WWS brought together scholars and practitioners in public policy, disabilities, politics, housing, education, participatory democracy, participatory action research, and critical evaluation. They developed a Collaborative Action Research program defined as “a flexible research methodology that integrates […] collaboration and participation, research and inquiry, action and change” (Brunner et al., Reference Brunner, Bennett, Bynner and Henderson2018: 3). It was coordinated by researchers from the Universities of Glasgow and Edinburgh and developed in partnership with over 40 public, third and community sector organizations.

WWS offers a rare example of programmatic participatory research that goes beyond single participatory spaces and generates various societal impacts across the democratic system. WWS developed a decentralized approach, with researchers joining various sites of action research emerging throughout the program. Four researchers were placed in local authorities as facilitators of collaborative inquiry alongside officials and community partners working on local policy challenges (see Bennett and Brunner, Reference Bennett and Brunner2020). Other researchers undertook itinerant roles in dozens of projects across communities and institutions working on social, economic and governance issues. Here we share three examples to illustrate range.

One project focused on the transformative role of Community Anchor Organizations in advancing local democracy through the commons. As collectively governed and shared resources and practices, the commons directly speak to participatory democracy’s call for structural solutions and socio-economic equality, as discussed above (Henderson and Escobar, 2024; Kioupkiolis, Reference Kioupkiolis2017). Scotland has a long tradition of commoning, with myriad community-owned initiatives, for example in housing, land management, energy generation and economic development. WWS community partners emphasized the need to focus on the role of the community sector in public governance, policy action and socio-economic change. Working with national community networks (i.e., Scottish Communities Alliance, Development Trusts Association Scotland), WWS sought to better understand, support and advocate for the commons. Part of this work entailed collaborating with six Community Anchor Organizations that were exemplary in local economic development, climate action, and services for disadvantaged communities (see Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Revell and Escobar2018). The findings were mobilized to support peer learning in the community sector through national events and to advocate for stronger policy support for the commons across Scotland (e.g. Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Revell and Escobar2020)).

The societal impacts WWS generated were geared towards fostering more participatory democracy and rethink and deepen its scope through collective reflection and research, with the aim to promote more inclusive and participatory approaches to goverrnance and policymaking. WWS undertook a review of the Scottish national policy on Community Planning, which coordinates participatory governance across public, third and community sectors. Research findings from ethnographic shadowing with frontline community workers was followed by participatory workshops and a two-wave survey of community planning practitioners (see Weakley and Escobar Reference Weakley and Escobar2018). These insights informed a training program to build capacity within public institutions and civil society organizations. Researchers collaborated with officials and community workers to develop a two-day course on public participation, process design and facilitation practices to support ongoing democratic innovation (e.g., community-led projects, digital engagement, participatory budgeting, mini-publics). This was a “Train the Trainers” course, so that participants could then cascade the training across their organizations and communities. Learning from this project supported changes in Community Planning Partnerships and informed a parliamentary enquiry in 2023 to assess how community empowerment legislation is advancing participatory governance in Scotland.

Community partners also wanted WWS to inform change at policy level to support practices on the ground. WWS collaborated with the Scottish Community Development Centre (SCDC) in carrying out research with community organizers to redevelop the National Standards for Community Engagement, which guide participatory practices across public, third and community sectors in Scotland. This entailed a Policy ReunionFootnote 6 , local and sectoral participatory workshops, and a survey co-designed to revise the Standards. The Policy Reunion gathered people involved in the first iteration of the National Standards in 2006, alongside people who sought to redevelop them in 2016. The subsequent workshops and survey generated insights from community organizers before opening a broader public consultation. The Standards became a widely used framework for the implementation of the 2015 Community Empowerment Act (Weakley and Escobar, Reference Weakley and Escobar2018: 65). They also became the foundation for the “Principles for Community Empowerment” (Audit Scotland, 2019) developed by the Auditor General to guide and scrutinize the work of over 200 public institutions across Scotland.

Imagining 2050 (I2050): societal visions of climate resilience in Ireland

Imagining2050Footnote 7 , a transdisciplinary research project that included participatory democracy and participatory research scholars, worked with two local communitiesFootnote 8 to co-construct visions of and pathways towards a low-carbon and climate-resilient society in Ireland by 2050. It explored how participatory processes could be used to engage communities in the development of future-oriented climate action measures at the local level with a view to informing the work of the National Dialogue on Climate Action (NDCA)Footnote 9 , a participatory initiative of the Irish Government, led by the Department of Environment, Climate and Communications.

The I2050 research team worked with each of the communities across three phases to imagine alternative visions for the future and develop pathways to get there. These phases included: (a) recruiting community members for the futures forums and conducting community surveys (in-person and online) to help identify core community concerns on climate action in the area; (b) running futures forums that involved brief accessible expert presentations (providing context and evidence on the impact of climate change), critical analysis, visioning, and scenario building using visual and interactive methods; and (c) co-producing and sharing the outputs. Two online StoryMap briefs were compiled to present key visions and recommendations from the forums. These were shared with the participants, wider community stakeholders, and government agenciesFootnote 10 . Additionally, the scenarios, visions and recommendations developed by each of the communities informed a Delphi panelFootnote 11 of policymakers and academic experts leading to an action plan; all output fed into the NDCA (see Revez et al., Reference Revez, Dunphy, Harris, Mullally, Lennon and Gaffney2020 and Mullally et al., Reference Mullally2022). Sitting at the intersection between participatory democracy and participatory research, the project brought together an original combination of participatory research methods and democratic participation processes to explore participatory and deliberative community engagement processes for co-creating societal visions. It drew on participatory democracy’s normative principles of inclusion, empowerment and social justice across multiple sites of participation in an iterative, closed out loop that inputted to the NDCA. Each forum’s outputs were shared through seminars and workshops organized with the wider community, civil society organizations, state agency officials, stakeholders and experts to gather further insight on the process and build on the recommendations.

It also embedded participatory research’s epistemic premise that diverse understandings, views and lived experiences exist across multiple places and spaces and that individuals and communities can be experts in their own lives. Blending futures thinking and participatory research methods it used sense making, empathy mapping, story boarding and community mapping to facilitate the sharing of local knowledge and experience and their inclusion in each community’s co-created futures visions, scenarios and pathways to climate resilienceFootnote 12 .

Adopting a critical approach that questioned the status quo and facilitated the co-creation of new forms of knowledge, and the development of imaginative visions and future pathways, I2050 sought to capture each community’s own expertise and experience of climate change and their wishes and imaginings for the future. By co-creating societal visions of what they wished for their community in 2050, participants identified pathways to achieving those visions. Participatory research methods supported them in their reflections on what it would be like for different groups to live there at that time. Empathy mapping, doodles and storyboards enabled participants to step into the shoes of residents of the future, highlighting how visions of a socially just world need to start from diverse knowledges and experiences.

Thus, employing participatory action research processes embedded in participatory democratic norms, I2050 emphasized inclusion and critique in an iterative, evaluative process. In this way, it also sought through the NDCA to inform and impact practice beyond the local, contributing to wider societal visions.

Table 1. Overview of the three projects

Cross-fertilization: mutual learnings and critical reflections

These three projects are examples of how the normative values and social justice ambitions of participatory democracy can enrich and widen the scope of participatory research, while the latter’s practice driven by epistemic justice can help advance an inclusive participatory society. These participatory democracy processes – e.g., youth-led Legislative Theater and digital participation (Mindset Revolution), commoning and participatory governance (WWS) and Deliberative Future Forums (I2050) – aimed to realize ambitious visions of rooted and impactful participatory democracy. By acknowledging participants as equal and agentic knowledge creators, these projects of democratic renewal emerged from a deep commitment to combine social and epistemic justice. They actively generated societal rooting, societal impact and societal vision by bridging participatory democracy and participatory research and, in this way, they navigated, more or less successfully, the constraints of universities situated within a wider neoliberal order. In this section we examine the strategies used to this end and reflect critically on their shortcomings.

Neoliberalism is understood here as a globally hegemonic political rationality permeating not just state policies but our ways of living in capitalist societies (Harvey, Reference Harvey2007). It is not simply about markets or social class but an imaginary of social reproduction where economic rationality is applied to all forms of human activity and forms the basis of a style of political governance (Brown, Reference Brown2015). The growing rhetoric on “co-production of knowledge” through participatory research and community engagement, in particular targeting “marginalized groups” are easily added to “business-as-usual development policies,” and they risk offering cover for dominant ideologies of commodification, marketization and gentrification (Peck and Theodore, Reference Peck and Theodore2019). Similarly, the increasing popularity of democratic innovations often fails to challenge the neoliberal status quo, as it tends to encourage citizen mobilization around short-term, often individualized action, premised on fragmented participation (Lee, Reference Lee2014).

Nevertheless, neoliberal rationality does not have to be the totalizing force that is sometimes assumed to be in contemporary capitalism – agency and change are possible (Wright, Reference Wright2010). The neoliberal university may be the playing field, but not necessarily the game we play. While navigating structural barriers, researchers can carve up spaces for emancipatory work and everyday resistance (De Certeau, Reference De Certeau1984), as they build alliances with the communities they work with to reclaim their own autonomy from all-pervasive forces of commerce, politics, and culture within neoliberal societies. By bringing the normative principles of participatory democracy oriented toward social justice into participatory research underpinned by epistemic justice, the projects presented here contribute to broader efforts to sketch a roadmap to work within, against and beyond neoliberalism (Bell and Pahl, Reference Bell and Kate2018; see also Wright, Reference Wright2010).

Clashing with neoliberal rationality

Participatory democratic ambitions realized in participatory research projects are threatened by neoliberal rationality in university structures (Münch, Reference Münch2014). The problem often starts with research proposal requirements, which tend to leave limited room for experimentation and genuine co-production of the research process (Bussu et al., Reference Bussu, Lalani, Pattison and Marshall2021). Funders tend to incentivize short term outcomes and impact, and this, combined with limited funding, can constrain deeper aspirations to create a civic Umwelt. Short funding cycles, without investment in post-project institutional leadership that can help root learning and impact, often mean that the newly built social capital rapidly dissipates as researchers may struggle to maintain connections and relationships with communities and partners when the funding streams cease. There is also a lack of acknowledgement of the importance of failure as crucial for learning and capacity-building in democratic processes.

The diversity in epistemological, axiological and methodological approaches to knowledge creation, mobilization and action that these projects entail, is illustrative of the rich praxis more broadly available to advance participatory democracy. However, it also raises challenges to building shared visions. Developing facilitation skills is crucial to create pluralistic spaces where multiple values and ways of knowing can be brought together productively. Diverse partnerships also force researchers to acknowledge relations of power between different actors. The denial of these differences does indeed exacerbate inequalities; it is only when all involved recognize themselves as equal partners (and perceive relational dynamics to be on an equal level) that genuine co-creation can occur, and new democratic structures and relationships are formed. This requires time to build relationships of trust, mobilize resources and foster mutual understanding and shared purpose. However, funders hardly ever recognize the benefits of investing in relationships (as opposed to outputs). Relationships are the building blocks of co-created visions for democratic futures, but it takes time and resources to build mutual trust and understanding. In the case of I2050, the research team applied for funding and then later sought out the communities and the partners, but recruiting partners and residents in the absence of an existing relationship proved challenging. In Mindset Revolution, the young people recognized this issue in their participatory evaluation: “More time at the start to bond as a group and across groups would have helped.”Footnote 13

Research institutions are often unprepared for (or even inhospitable to) the collaborative, participatory and relational approaches that drive projects like those presented here. The official policies and statements of universities in support of co-production with citizens and non-academic stakeholders are seldom matched with governance and bureaucratic reform of universities. Although many higher education institutions’ research strategies advocate participatory research, and a few have established administrative units with dedicated roles to foster civic and community engagement and engaged research, large university bureaucracies often lack the flexibility and resources to support partnerships that involve grassroots actors and communities in a sustained capacity. Research institutions are not generally set up to collaborate on an egalitarian basis with “external” non-academic partners in communities and public institutions. This often transpires in the way research funders prioritize leadership and management of projects by universities, rather than co-productive approaches in collaboration with partners. Particularly in Mindset Revolution and WWS, the rigidities of structures and procedures had to be constantly navigated to shift mindsets and practices from command and control to networked collaboration.

Furthermore, researchers belonging to different departments, schools and universities can encounter challenges in working together because of hierarchical norms, disciplinary boundaries, managerial constraints and diverse lines of accountability. In the case of WWS, a great deal of time and energy was spent addressing such intra-organizational challenges. By the same token, research institutions are not always ready to genuinely collaborate with each other, despite abundant rhetoric about inter-institutional and transdisciplinary collaboration. WWS required considerable “backstage work” to reconcile disparate approaches to program management, staff recruitment and project resourcing amongst the different actors involved.

Participatory research can pose a challenge in academic contexts, where research is often framed in commodified and hierarchical ways. Funding and research processes are defined by the neoliberal political economy in which they function. Bell and Pahl (Reference Bell and Kate2018: 108) warn against neoliberalism’s ability to co-opt participatory practices “so that forms of knowledge co-production are diluted, repressed, or turned against those who produce them.”

By the same token, within a growing sector of democratic entrepreneurship, participatory democracy is oftentimes being promoted as easily implementable blueprint processes, sponsored by governments and international organizations, and comfortably incorporated into the neoliberal jargon of “open government” and “good governance,” without meaningfully challenging existing power imbalances (Bua and Bussu, Reference Bua and Bussu2023).

Fostering social and epistemic justice in neoliberal times: societal rooting, impact and vision

The three projects illustrate how meaningful participation in research and public governance cannot only exist but also be sustained within and despite the neoliberal order, working beyond neoliberal appropriations of participatory research and participatory democracy. By rooting participation in a community (geographical, of practice or interest), generating real-world impacts and connecting the projects to an inclusive vision of social justice, these projects navigated barriers, with mixed results and yet producing important learning for future work.

Partnerships furthered societal rooting, impact and vision through their use of a layered approach across multiple participatory spaces, namely the wider community, civil society, grassroots activism, state institutions, stakeholders and academia, to inform and impact practice beyond a defined project. Mindset Revolution is steadily developing from a small participatory project on youth mental health into a youth-led process of culture change on mental health and youth participation, as young people build democratic skills but also relationships throughout the project. For all the structural barriers to youth participation, funding constraints and conflicts within the partnership on objectives and outcomes at different points, a strategy of societal rooting, based on multiple and flexible spaces that were reshaped to adapt to young people’s complex lives, resulted in sustained involvement in related projects. Young people feel ownership of the process and are committed to seeing their recommendations implemented. At the time of writing, several partner organizations continue to work to identify new funding opportunities, while new collaborations are slowly being built with researchers and youth groups in other regions and countries to recast youth mental health as a global commons. By embedding the participatory evaluation into the project, young people and adults were able to continuously reflect on their positionality and democratic agency, their social impact and their relationships, inevitably imbued with power differentials and at times unacknowledged adult privileges. The participatory research helped bring to the forefront young people’s own epistemic vision of what youth mental health means from an intersectional standpoint. By the same token, the participatory democracy principles underpinning the project gave it a broader scope, beyond its policy focus on mental health, placing the emphasis on strengthening youth democracy.

WWS aimed to connect the numerous fragmented participatory efforts in Scotland, both from the top-down and bottom-up, into a cohesive vision of a participatory state and society. Societal impact was realized through decentered research activities on governance and public service reform by creating local partnerships involving different sectors and institutional, civic and community actors. The research approach was grounded in the everyday democracy of the commons, building on their activities and demands to open up public services’ reform and delivery. Through an emerging research agenda shaped through dozens of interconnected collaborative projects, WWS sought to nurture a critical mass for research-informed change in policy and practice. This was predicated on a multi-sited, multi-layered, and action-oriented approach to co-inquiry, with a dynamic link between research, capacity-building and policy work. The example of WWS illustrates that participatory research is not limited to specific sites but can be developed as a large-scale, systemically-oriented program (see What Works Scotland, 2019). Despite pitfalls and challenges (see Bennet and Brunner, Reference Bennett and Brunner2020; Brunner et al., Reference Brunner, Bennett, Bynner and Henderson2018), WWS demonstrates how an adaptive ecology of participatory research practices can underpin and support a transition towards a participatory culture in policymaking and wider society.

Finally, I2050 engaged with diverse actors (community residents, stakeholders, civil society, policymakers, and academics) in a range of participatory processes to inform a national-level process on key climate action concerns. Within the Deliberative Futures Forums, a variety of participatory research and visual tools such as doodles, maps and audience polls helped frame the deliberation based on participants’ lived experience, enabling them to imagine, vision and critique climate futures. Societal visions and scenarios emerged from this reflective process and translated into a range of co-created outputs. These informed community-led policy recommendations for a socially just future that the community could feel ownership of, as it recognized and reflected its diverse knowledges, experiences and concerns.

Conclusion

This article has undertaken the task of bringing normative theories of participatory democracy and practical experiences of participatory research together, addressing a gap in Global North academia. It demonstrates what the two fields can learn from each other. Drawing on the epistemic justice underpinning of participatory research, participatory democracy scholars can employ participatory research approaches to realize their normative ideals within their own academic practice. Drawing on the social justice orientation of participatory democracy, participatory researchers can expand their participatory ambitions by connecting their practical work to a transformative vision of a participatory society, while situating their projects within participatory ecologies that challenge neoliberal technologies of power. In this paper, we drew on three examples in which participatory democracy scholars engage in participatory research and generate societal rooting, impact and vision, as strategies to carve out zones of resistance to neoliberalism and promote social and epistemic justice.

This work contributes to the debate on the challenges of realizing participatory research and participatory democracy within the neoliberal knowledge and political economy. Epistemic and social justice commitments need to be necessarily intertwined as part of a project of substantive democratic renewal. While neoliberal university structures can sharply limit democratic ambitions in practice (while promoting them in rhetoric), our projects demonstrate that the neoliberal logic can be gamed, helping to open up space for genuine and meaningful participation that enables societal rooting, impact and vision. Even in difficult contexts, researchers can use the “engagement/impact/co-production” discourses of funders and research institutions’ vision documents to carve out space despite the discrepancy between those discourses and everyday practices. De Certeau (Reference De Certeau1984) points to the double edge of discourse: it can be used to subvert the intentions of those who peddle it (perhaps) with co-optative intentions. By committing to work with the same communities over the long-term, investing in relationships of trust, beyond the confines and constraints of small projects, researchers can contribute to building a participatory culture, bridging across different epistemological worlds and helping to situate their projects within a broader vision of democratic renewal.

Scholars, universities, and disciplinary communities can also learn to reclaim the value of failure in an environment conducive to ongoing learning, and where participants are supported to experiment with different ways of practicing democracy and participate in knowledge co-creation. This requires investment in the roles of boundary spanners across policy, services, communities and academia to create safe buffer zones (Bennett and Brunner, Reference Bennett and Brunner2020) where we can develop shared languages and modes of working – e.g., learning to walk in each other’s shoes and understanding each other’s pressures. Funding for community-research hubs that can foster and support different participatory approaches, or science shops and innovation labs based in the community rather than academic institutions, can play an important role in creating and protecting these buffer zones and thus support a stronger “civic Umwelt.”

Our contribution illustrates that participatory research on and for participatory democracy can carve up interstitial spaces to support change in neoliberal contexts (Wright, Reference Wright2010). We hope this article rekindles debate about how democratic ideals and participatory practices can be not just objects of research, but its modus operandi. This matters because social and epistemic justice are inextricable for critical social research worthy of its name, and for participatory democracies worthy of a future.

Acknowledgements

Bussu’s research was funded by the RSA/ UKRI. Bussu is indebted to partners and young people for their continuing work on the project.

Escobar’s research was supported by the What Works Scotland program (2014–2019), funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council and the Scottish Government under Grant ES/ M003922/1. Escobar thanks partners across research, policy and practice in Scotland for their collaboration in the program.

Harris’s research was funded under the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Research Program 2014–2020 and co-funded by Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI). The EPA Research Programme is a Government of Ireland initiative funded by the Department of Communications, Climate Action and Environment. Harris thanks all the Imagining 2050 research participants, for their time, commitment and collaboration.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and project leadership: HA, SB

Writing coordination: HA, SB

Research fieldwork: SB, OE, CH

Research analysis: HA, SB, OE, CH

Writing sections: HA, SB, OE, CH

Editing and re-writing: HA, SB, OE, CH