Introduction

In medieval scholastic thought, ‘internal’ or ‘spiritual’ senses complemented the ‘external’ bodily senses, enabling humans to perceive the divine and live a devout and righteous life (Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen and Newhauser2014: 112–18; Newhauser Reference Newhauser and Newhauser2014a: 5–6). This is exemplified in a late-twelfth-century illuminated manuscript, wherein a ‘divided’ ladder is depicted as the pathway to heaven or hell (Figure 1). After birth, humans climb this ladder of life by means of their sensory faculties—the rungs are made of the Latin words for vision, hearing, taste, smell and touch—but the “senses alone carry humanity only to the fork in the ladder” (Newhauser Reference Newhauser and Newhauser2014a: 14), where it splits into two pathways: one to Christ in heaven with the cardinal virtues as rungs, the other to Satan with vices as steps to hell. This is what we may refer to as a sensory regime, which is, as this article argues, rendered possible through material culture. Such sensory regimes not only facilitate social, political and religious regimes but can also challenge or oppose them. Here, material culture plays a dual role in supporting or opposing these regimes, which can be analysed within archaeological contexts.

Figure 1. The five senses and Christian medieval thought: the divided ladder to heaven or hell (Universitätsbibliothek Erlangen-Nürnberg, MS 8, fol. 130v, final quarter of the twelfth century; source: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bvb:29-bv045506112-5#0262).

This article explores sensory experience and material culture in medieval and Early Modern archaeology (c. AD 500–1800), focusing on Central and Western Europe, and addresses the following two key questions: How can sensory regimes be identified and analysed through material culture? What are the opportunities and limitations of examining sensory perception in medieval archaeology?

By first entertaining the concept of sensory regimes, I can then examine case studies, with a focus on how material culture (dis)established such regimes, offering new perspectives for the study of the senses in medieval archaeology.

Sensory perspectives in archaeology

Significant studies have emerged within the fields of prehistory and classical archaeology, proposing new frameworks often labelled as ‘sensory archaeology’ or the ‘archaeology of the senses’ (Day Reference Day2013; Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2013; Skeates Reference Skeates2010, Reference Skeates2017; Skeates & Day Reference Skeates and Day2020; Jordan et al. Reference Jordan, Mura and Hamilton2025). Many of these studies stress that sensory archaeology involves neither specific nor established methods or theories and, perhaps most importantly, that it should not. Rather, it is the social, cultural and religious aspects of the senses that warrant investigation in historical scholarship, moving beyond the mere reconstruction or representation of past sensory experiences.

Approaches in European medieval archaeology

European medieval archaeology, particularly German-language scholarship—the perspective from which this article is written—has largely overlooked the senses (Müller Reference Müller2021: 142); medieval art history and literary studies, by contrast, have produced a significant body of literature on the subject (e.g. Newhauser Reference Newhauser2014b; Bagnoli Reference Bagnoli2016; Thomson & Bintley Reference Thomson and Bintley2016; Griffiths & Starkey Reference Griffiths and Starkey2018; Dempsey & Jasperse Reference Dempsey and Jasperse2020). Such studies have traditionally emphasised the five individual senses (Griffiths & Starkey Reference Griffiths and Starkey2021: 103) as both medieval Christian and Islamic philosophical traditions operated on the sensorium derived from Aristotle’s de anima (Jütte Reference Jütte2000: 65–72; Palazzo Reference Palazzo2012; Newhauser Reference Newhauser and Newhauser2014a: 6; Reference Newhauser and Classen2015: 1563–64).

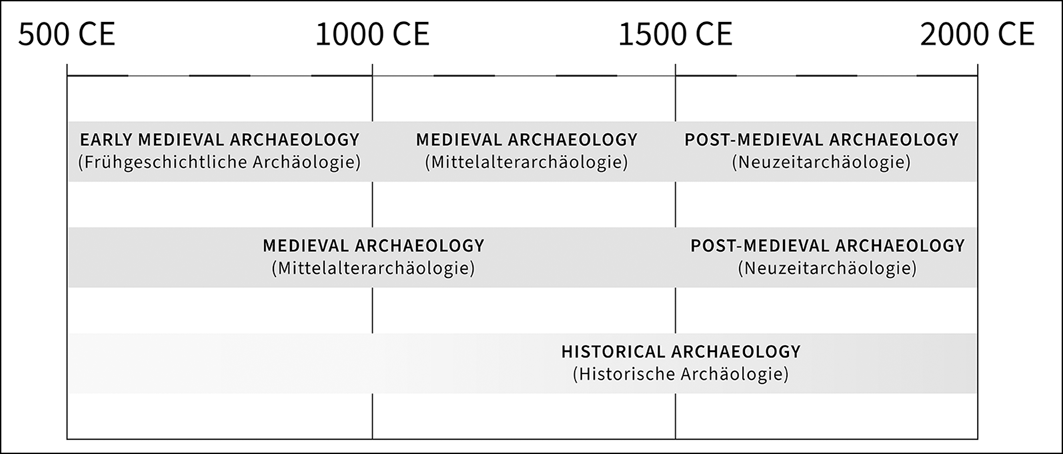

Here, I would like to briefly clarify the disciplinary traditions in German-language medieval and historical archaeology, which sometimes differ from their English-language counterparts (Figure 2). Traditionally, the early medieval period, roughly up to the end of the Carolingian era in the tenth century, falls under Frühgeschichtliche Archäologie (proto-historic archaeology). Medieval and (early) modern archaeology, often combined under the umbrella of Archäologie des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit, emerged primarily after the Second World War, while the term Historische Archäologie is a relatively recent development. Depending on the definition, historical archaeology may relate to the periods following the Roman presence in Western and Central Europe (c. late first century BC and first century AD) or, more commonly, refer to the periods from the later Middle Ages in the fourteenth century to the twentieth and twenty-first centuries (Mehler Reference Mehler and Mehler2013; Müller Reference Müller, Ridder and Patzold2013). For the sake of brevity, I will use the term ‘medieval archaeology’ in this article to refer to both the medieval and Early Modern periods.

Figure 2. The various nomenclatures and chronologies in German-language Archäologie des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit and Historische Archäologie (figure by author, based on Müller Reference Müller, Ridder and Patzold2013: fig. 2 and Mehler Reference Mehler and Mehler2013: tab. 1, with additions).

Within this field of medieval archaeology, few studies have specifically explored the senses. O’Neill and O’Sullivan (Reference O’Neill, O’Sullivan, Skeates and Day2020), for example, investigated sensory experiences through experimental archaeology, focusing on medieval houses and ironworking. For the migration period (c. fourth to sixth centuries AD), Wicker (Reference Wicker2020) explored multisensory aspects of Scandinavian gold bracteates, emphasising their visual brilliance, tactile qualities and their role in creating emotions and memories. More generally, I have investigated aesthetics and early-medieval material culture in my own work (Friedrich Reference Friedrich2023: 132–70).

Theory and method: sensory regimes

Introduced to archaeology by Hamilakis (Reference Hamilakis2013: 17–24), the concept of sensory regime is rooted in his critique of Western sensory regimes, particularly of vision in modern scholarship. Related yet not identical terminology, such as sensory orders, profiles, modalities or sensescapes (Skeates Reference Skeates2010: 3; Skeates & Day Reference Skeates and Day2020: 4–6), generally describe how societies or cultures in specific times and places “translate[d] sensory perceptions and concepts into a particular ‘worldview’” (Classen Reference Classen1997: 402). In contrast, sensory regime is a more narrowly defined term that focuses specifically on the social implications of sensory perceptions, particularly their role in shaping and maintaining structures of power and authority. Put briefly, sensory regimes investigate how the sensorium is established, maintained and eventually challenged.

Therefore, in this article, sensory regimes are defined by the normative and regulatory dimensions of sensory perception. This concept extends beyond the cultural categorisation of sensory practices, often referred to as sensory orders, which emphasise cultural hierarchies; sensory regimes refer to the social regulation and control of the senses within systems of power.

Visual culture and scopic regimes: theory

These subtle yet significant nuances in meaning—the broader cultural focus of sensory orders against the narrower focus of sensory regimes on power and authority—may explain the different theoretical backgrounds of the two closely related concepts. While Hamilakis (Reference Hamilakis2013) refers to the concept of sensory regimes, he does not explicitly elaborate on its history. To contextualise sensory regimes, it is necessary to examine connections with visual culture theory, which provide a foundational framework for the concept. Visual culture is generally defined as the “visual construction of the social”, which includes “everyday practices of seeing and showing” (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2002: 170). Although its scope remains debated, visual culture generally includes practices such as art, media and images (Sandywell & Heywood Reference Sandywell, Heywood and Heywood2012: 31–35); sensory studies expand this definition by explicitly including all forms of sensory perception, not just vision.

More specifically, the concept of sensory regime traces its origins to the term ‘scopic regime’, which is frequently used in visual culture theory. The term is employed by Jay (Reference Jay and Foster1988, Reference Jay and Jay2011), drawing on the work of French film theorist Metz (Reference Metz1982: 61–66). Jay defines scopic regimes as “practices of visuality that include cultural, political, religious, economic and other components [and] a relatively coherent order in which protocols of behaviour are more or less binding” (Jay Reference Jay and Jay2011: 60). Equally important to the term is Rancière’s (Reference Rancière2004) work on the politics of aesthetics, which outline different political aesthetic regimes that connect sensory perception to wider social and political issues.

It is also useful here to explain the term regime. Historically, it is linked to the French Revolution and the opposition to the ancien régime. This association with power and authority persists in later uses, such as the bourgeois regime described by Marx and Engels in their Communist Manifesto (cf. Sellin Reference Sellin, Brunner, Conze and Koselleck1984: 392); in this context, the term is rooted in nineteenth-century class conflicts and eventually made its way into everyday language. Sensory regimes therefore explicitly include issues of dominance, regulation and authority (Geng Reference Geng2019: 102–103).

Investigating sensory regimes through material culture: methods

Much archaeological scholarship is devoted to material culture and its role within society, mostly under the umbrella of object or material agency (cf. Knappett & Malafouris Reference Knappett, Malafouris, Knappett and Malafouris2008). Material culture—such as objects, architecture and landscapes—actively shapes, reinforces or challenges the social, religious and political regimes within which it is embedded through its sensory properties. Although the concept of sensory regimes is rarely explicitly addressed in archaeological studies, certain works, particularly within American historical archaeology, suggest similar ideas without fully engaging with the theoretical framework laid out above.

For instance, Beaudry’s (Reference Beaudry2013) analysis of food and dining practices in late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century New England, USA, interprets dining events as synaesthetic experiences that mediated social status and identity. Similarly, contributions to a 2022 special issue of Historical Archaeology explore related themes. Metheny (Reference Metheny2022: 177) advocates for the need to “contextualize … sensory data associated with archaeological evidence” to “engage with the multisensorial experience of daily life in the past”. Loren’s (Reference Loren2022) study of the sensory aspects of tobacco use at seventeenth-century Harvard College contrasts the sensory pleasures of smoking with Puritanical views that framed excessive smoking as “sinful temptations”, illuminating the tension between sensory pleasure and moral regulation in colonial New England. Likewise, Gaitán Ammann’s (Reference Gaitán Ammann2022: 199) “object-based reenactment of the soundscape of Old Panama’s slave market” highlights the potential of the social analysis of past sensory experiences for modern public understanding and memorialisation.

In contrast, European medieval archaeology has so far overlooked sensory experiences, leaving a significant gap in understanding how the senses shaped, and were shaped by, material culture. This study addresses this gap by integrating interdisciplinary frameworks from visual culture theory, sensory studies and disability studies to interpret the social and political implications of sensory regimes in medieval material culture. The following case studies have been chosen with the aim of addressing the question of how material culture facilitates or opposes sensory regimes.

Material humour, religious regimes and sensory experience

The senses are also linked to other human phenomena, such as memory, emotions and humour. While we tend to think that emotions, affect or humour are immaterial, they can be evoked through and with the material world and sensory perception (Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2013: 124–25; Nugent Reference Nugent, Skeates and Day2020). In the high and late Middle Ages (c. AD 1000–1500), we encounter many everyday artefacts that combine and evoke various sensory responses and emotional states, especially gambling and humour. A vast number of commodities such as rosaries (haptic sensory memory), gaming pieces and dice are found in medieval Central European towns and cities. A salient example of the affective nexus of humour and material culture (Bayless Reference Bayless and Bayless2020: 13–16) is a ‘puzzle jug’ that was made around 1300 in France (Allan Reference Allan, Rippon and Holbrook2021: 491) and found in Exeter, England, in the late nineteenth century (Figure 3). Although commonly referred to as a puzzle jug, the medieval Exeter jug differs from the more elaborate Early Modern versions. These later jugs often featured intricate systems of hollow rims, tubular handles and multiple spouts, designed to challenge the user and cause spillage if not operated correctly. In contrast, the Exeter Puzzle Jug is simpler in its functional design, featuring only a tubular handle that connects the vessel’s neck and body—as Crossley (Reference Crossley1993: 74) observed: “[f]illing [it] was more of a puzzle”.

Figure 3. Exeter Puzzle Jug, c. 1300, showing a ‘naked’ bishop with a crozier (© Royal Albert Memorial Museum).

Yet the decoration, with ambiguous and humorous images and figures, is remarkable. The body of the vessel forms a tower with two naked bishops in its centre, while women and musicians celebrate below. The jug is multicoloured, sporting various ornaments, and the handle and spout transform into human and mythical creatures. Besides the multisensory experience drinking wine from a vessel with various images and figures, the jug ridicules the Church and its hypocrisy towards its own sensory regime through the very pleasure of the senses. The Exeter Puzzle Jug, with its humorous depictions of naked bishops, exemplifies how material culture sensorially critiqued religious regimes through visual (imagery), tactile (object) and gustatory engagement (wine jar).

Stove tiles

In the later Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, the tiled stove or Kachelofen was a major development in the households of urban and rural elites (Roth Heege Reference Roth Heege2012). Its basic function was to provide continuous heat and warmth to the central rooms of the house. Yet, while we may regard heating as the ‘core’ function, this does not do justice to the complex sensory and social implications that accompanied its use; throughout prehistory, the fireplace has served as a central social space (Jones Reference Jones2007: 1–21). In the late medieval and Early Modern household, the stove created a pleasant (heated) environment and by doing so it was also a social space that encouraged interaction.

The tiles of medieval and Early Modern stoves were frequently decorated, ornamented and illustrated with various images, from architectural elements to religious iconography. A small late-sixteenth-century tile fragment from Lüneburg illustrates the multisensory aspects of this everyday material culture of urban and rural elites (Ring Reference Ring2009); it shows the personification of smell (Figure 4), a subject found frequently on tiles and in the emerging print media. Perhaps more striking are the so-called Reformationskacheln (Reformation tiles) that appeared in the mid-sixteenth century. They include representations of protestant reformers and inscriptions, but also anti-Catholic and often humorous images. One example, again from Lüneburg (Figure 5), bears the invertible ‘cardinal and fool’ motif (Ring Reference Ring and Mehler2013).

Figure 4. Stove tile from Lüneburg (left) with the allegory of smell, second half of the sixteenth to early seventeenth century. Identifiable through a copper plate print from Georg Pencz (right) (left photo: © Sammlung des Museums Lüneburg; right photo: © Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum Braunschweig, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

Figure 5. One stove tile from Lüneburg combining a fool (above) and cardinal (below), second half of the sixteenth to early seventeenth century (© Sammlung des Museums Lüneburg).

Like the Exeter Puzzle Jug, the tile taunts the Roman Catholic Church but here in the religious and political context of the Reformation. Stoves sporting Reformation tiles sensorially challenged the Catholic religious regime: together with their visual motifs, the stoves created a social space through the heat they generated and the tactile interactions they invoked. Through the stove, the central room of the Early Modern household became a place of sensory engagement, where religious identities were negotiated and previous regimes contested.

Restoring the bodily senses: prostheses

At first glance, prostheses and orthoses do not appear to have much in common with the senses. In the Middle Ages, however, they were not only used to substitute the loss of limbs or support other physical impairments but also to overcome their exclusionary and marginalising social after-effects. While actual prostheses are scarce in the archaeological record of the Middle Ages (Kahlow Reference Kahlow and Nolte2009), burials can provide more data for analysis (Baumgartner Reference Baumgartner1982; Buchet et al. Reference Buchet, Darton, Legoux, Delattre and Sallem2009; Bohling et al. Reference Bohling, Croucher and Buckberry2023). Disability studies or disability history (Nolte et al. Reference Nolte, Frohne, Halle and Kerth2017), which are increasingly explored in archaeology (Bösl Reference Bösl2022; Evelyn-Wright Reference Evelyn-Wright2024), provide an apt framework for understanding prostheses not just as medical devices but as social and cultural objects. The distinction between impairment as a physical condition and disability as a social construct is particularly important in this context; prostheses can therefore be seen as objects that bridged the gap between the impaired body and the disabling environment, reflecting social views towards inclusion or exclusion (Evelyn-Wright Reference Evelyn-Wright2024: 3–4).

Shoe-shaped vessels from Pleidelsheim

A salient case is the burial of an 18- to 20-year-old female from Pleidelsheim, Germany (Koch Reference Koch2001: 472–74). The burial (grave 140) dates roughly from the mid- to late sixth century and contained two unique shoe-shaped ceramic vessels (Figures 6 & 7). The skeleton was in fact missing both feet and the distal joint of the left tibia. The initial anthropological and archaeological report suggested the female—otherwise “in good health”—had lost both feet perimortem without specifying the exact cause (Koch Reference Koch2001: 251, 472). The shoe-shaped vessels were not, however, placed in the accurate ‘anatomical’ order but adjacent to the missing appendages in the south-east corner of the burial chamber. Koch (Reference Koch2001: 250–51) interprets the vessels as stilts without detailing how the pottery could have withstood the weight of a stationary human, much less the percussive forces generated by moving around on them. Engaging with this critique, Sicherl (Reference Sicherl2011: 34) sees the interment of shoe-shaped vessels as a symbolic act against the undead. Both interpretations miss the point; the prostheses from Pleidelsheim—functional or not—restored the body and its sensory faculties. It did not matter that the shoe-shaped vessels were impractical because they were a means for the bodily and sensorial restoration of the deceased.

Figure 6. View of grave 140 in Pleidelsheim. The shoe-shaped vessels were found in the south-east corner of the burial chamber (© Landesamt für Denkmalpflege im Regierungspräsidium Stuttgart).

Figure 7. Shoe-shaped vessels found in grave 140 in Pleidelsheim, Germany, dating to the mid- to late sixth century (© Landesamt für Denkmalpflege im Regierungspräsidium Stuttgart; drawing: Koch Reference Koch2001: pl. 61).

From this also follows that “to be a good and worthy individual, or … to be considered fully human, one had to have all one’s faculties. Physical disability and sensory impairment were impediments to moral goodness” (Woolgar Reference Woolgar and Newhauser2014: 26). Although notions of and reactions to physical impairments and disabilities differed within medieval societies (McNabb Reference McNabb2020: 14), the exclusion of disabled persons from social and religious participation (Metzler Reference Metzler2006; Wheatley Reference Wheatley2010) was rendered possible through a sensory regime, perhaps in its truest and most literal sense. The burial of the woman in Pleidelsheim illustrates how objects restored bodily and social integrity, supporting the disability studies concept of physical impairment as a social construct.

Spectacles and moral vision

Prostheses are not limited to the substitution of lost extremities but also include bodily and sensory enhancements, particularly in terms of vision. Optics played a significant role in high and late medieval philosophy (Kärkkäinen Reference Kärkkäinen and Newhauser2014: 118–21) and here Peter of Limoges’ Tractatus moralis de oculo, the Moral Treatise on the Eye (Kessler & Newhauser Reference Kessler and Newhauser2018), is a particularly notable example of this tendency: “[i]n these, the site of seeing was literally a mirror, namely, the ‘crystalline humor’ where God’s light, located in the anterior part of the brain, is unified with rays from the eyes into a double vision” (Kessler Reference Kessler2011: 3). But this “hybridization of science and theology” (Kessler Reference Kessler2011: 14) was not only philosophical, it was very much material in its nature: while Kessler rightly points out the significance of mirrors and reflections in medieval art and their ties to optical theories, the same holds true for material culture.

Spectacles—today an everyday object—were invented in northern Italy in the late thirteenth century and spread rapidly across late medieval Europe and beyond (Ilardi Reference Ilardi2007). Examples have been recovered from late medieval sites, such as Wienhausen Abbey, a Cistercian nunnery in northern Germany. At least three pairs of glasses, dating to the mid-fourteenth century (Figure 8), were discovered between the wooden floors of the nuns’ choir (Richter Reference Richter and Biermann2020). These rare finds provide direct evidence of the use of spectacles in a monastic setting, where nuns read bibles, psalms and prayer books during liturgy.

Figure 8. Medieval spectacles found in Wienhausen Abbey, Germany, mid-fourteenth century (© Klosterkammer Hannover, Ulrich Loeper).

In terms of Peter of Limoges’ concept of double vision, which combined visual perception and the cognition of God’s light, medieval spectacles not only corrected presbyopia (age-related long-sightedness) but provided good and moral vision. By enabling the clergy to read and comprehend sacred texts—both externally and internally—glasses as prosthetic objects reinforced the medieval scholastic sensory regime. Their use in ecclesiastical or monastic settings, such as Wienhausen Abbey, demonstrates how prostheses could exceed their technical function, facilitating both sensory and spiritual experience.

Sensory exclusion: Jewish quarters in the later Middle Ages

The case studies discussed so far refer mostly to the positive aspects of sensory perception and the active role of material culture in addressing sensory regulations. However, sensory experiences and practices can also serve to include or exclude and in so doing marginalise individuals and groups based on gender, age or religion. Here, sensory regimes provide a useful framework for analysing how such exclusions were made possible. Sensory regulations of medieval urban space were sometimes used to create and maintain boundaries, for example between Jewish and Christian communities. The case of medieval Vienna is illustrative in this instance.

Medieval Vienna: Judenplatz

During the period of urban growth in the thirteenth century, many Central European towns initially attracted small Jewish groups, which later grew into larger communities. In recent decades, medieval Jewish quarters have been at least partially excavated in several locations, revealing traces of synagogues, mikvahs, cemeteries and residential buildings (Harck Reference Harck2014: 140–216). Evidence for the presence of Jewish individuals and families in Vienna in the twelfth century is scarce, increasing in the thirteenth century. Archaeological excavations, building archaeology and textual evidence permit the reconstruction of the Jewish quarter in medieval Vienna, which was established in the second quarter of the thirteenth century between the duke’s palace in the west and Hoher Markt in the east, with modern-day Wipplingerstraße as its main street. Since the mid-1990s, when work for the Austrian Holocaust Memorial began, excavations have uncovered a synagogue in the centre of the Judenplatz (Figure 9), a hospital close to the synagogue, a bathhouse in the south-east corner of the quarter and a slaughterhouse in the north-west, as well as various stone walls and residential buildings (Mitchell Reference Mitchell and Peterle2021).

Figure 9. The Jewish quarter in medieval Vienna. Black lines show the quarter’s outline and buildings, based on archaeological excavations, building archaeology and textual evidence; the medieval streets are depicted in grey (figure by author, based on Mitchell Reference Mitchell and Peterle2021: 54).

Significant for understanding sensory regimes of exclusion are the boundaries of the Jewish quarter: it was not enclosed by walls but defined and confined by the back walls of buildings and courtyards and, most notably, gates that controlled access to and from the area (Mosser et al. Reference Mosser, Krause and Gaisbauer2013: 4–6; Keil Reference Keil, Zapke and Gruber2021: 327). Currently, six gates have been identified “either through archaeological investigations or from pictorial sources” (Mitchell Reference Mitchell and Peterle2021: 55–57). This includes the main gate at Wipplingerstraße and three archaeologically identified gates located towards the south and south-west of the quarter at Färbergasse, Parisergasse and Kurrentgasse (Figure 10). The gate at Färbergasse can possibly also be linked to a textual source from 1422 that mentions a Türlein—a small door or gate that separated the Jewish quarter from the duke’s palace (Mosser et al. Reference Mosser, Krause and Gaisbauer2013: 6).

Figure 10. Engraving by Jacob Houfnagel, printed in 1609, showing the early modern Judenplatz in Vienna (reproduction: National Library of Sweden).

The material and textual evidence so far indicates that the Jewish quarter in Vienna was at least partially enclosed by the layout of buildings both within and around the quarter, as well as by gates separating it from the rest of the city. This ‘semi-permeability’ was part of a late medieval urban sensory regime, which regulated interactions between the Christian and Jewish communities without entirely isolating them from one another. The quarter’s strategic location within the city, near its most significant marketplace, likely made it impractical to completely close it off but the proximity of Jewish and Christian religious sites necessitated the sensory separation of the two communities during religious activities, such as Shabbat and the many Christian holidays.

The extensive measures taken to separate the Jewish quarter were not merely symbolic but rendered possible through the regulation of sensory practices: visual, auditory and physical isolation established boundaries between the religious communities. When closed, the gates restricted both access to the quarter and sensory experiences, establishing a spatial and bodily separation through sensory regulation. Even when the quarter was accessible through opened gates, its layout likely contributed to a restricted sense of space within the city. Generally, this separation was also intensified by the growing violence against Jews in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The gates may have provided some security but ultimately failed to prevent the violent pogrom of 1420–1421, known as the Vienna Gesera. Jews were exiled, murdered or forced to convert to Christianity; Jewish property was seized, and the synagogue was demolished (Keil Reference Keil, Zapke and Gruber2021: 344–47), resulting in what is today called the Judenplatz (Figure 10)—a new name that emerged only after the pogrom.

Conclusion

European medieval archaeology has yet to fully engage with the sensory approaches put forward in other branches of the discipline. This article takes a first step in integrating the study of the senses into medieval archaeology, while also expanding the broader field through the concept of sensory regimes. Grounded in visual culture theory, the concept describes the norms and regulations of the senses, particularly how power and authority are established, maintained or challenged through material culture and the sensory practices associated with it.

Here, analysis focused on how material culture enabled the negotiation of religious regimes, the integrity of the human body and the exclusion of minorities. The thirteenth-century Exeter Puzzle Jug and Early Modern Reformation stove tiles actively challenged Catholic religious regimes, while prostheses, such as the shoe-shaped vessels from Pleidelsheim and spectacles from Wienhausen Abbey, complemented the sensory regime of the body. The Jewish quarter in late medieval Vienna exemplifies how material and sensory boundaries regulated minorities and reinforced power structures.

These case studies reveal ways in which material culture actively facilitated or challenged dominant sensory regimes and substantiate the analytical potential of this approach for medieval archaeology and the broader field of archaeology more generally—by exploring the interactions of material culture, sensory perception, and power in past societies.

Funding statement

The first draft of this article was written during a membership at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, USA.