Introduction

In Yemen, local nongovernmental organizations (LNGOs) are crucial in delivering essential services, especially in areas where governmental capacities have been weakened by the ongoing conflict since 2015 (Elayah et al., Reference Elayah, Gaber and Fenttiman2022). Their importance lies in their alignment with grassroots needs (AbouAssi & Trent, Reference AbouAssi and Trent2016). However, their financial sustainability and therewith their effectiveness is limited by financial constraints (Elayah et al., Reference Elayah, Gaber and Fenttiman2022). Global crises have worsened this funding crisis, with donor support from advanced economies to Yemen significantly reduced (Dautriat, Reference Dautriat2022), while demand for funds continues to increase, especially in conflict zones where conditions are deteriorating (Pack, Reference Pack2022). Reports from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) indicate a sharp decline in funding for Yemeni NGOs, dropping from $436.7 million in 2021 to $167.8 million in 2022 (Elkahlout et al., Reference Elkahlout, Milton, Yaseen and Raweh2022). Besides, although LNGOs now receive a larger portion of these vastly reduced funds, INGOs often act as intermediaries. Despite partnerships and training efforts, donor funding for INGOs still triples that allocated to local and national NGOs, endangering the financial sustainability of LNGOs (ICVA, 2021; OCHA, 2022). This limits LNGOs' direct donor relationships and growth which is further impacted by certain dominant LNGOs, termed ‘Sheikh’ organizations here, controlling much of the available funding. Yet, research on the financial sustainability of LNGOs in conflict-affected regions is limited. Studies by Tran and AbouAssi (Reference Tran and AbouAssi2021), Suárez and Marshall (Reference Suárez and Marshall2014), Stiles (Reference Stiles2002), and Bebbington (Reference Bebbington2004) have explored aspects of this topic, yet gaps remain, particularly concerning the role of influential ‘Sheikh’ LNGOs—large, well-funded local organizations backed by powerful individuals. Little research has examined how these ‘Sheikh’ organizations affect the financial sustainability and autonomy of other NGOs in conflict zones. Bridging this gap is essential to understand how ‘Sheikh’ LNGOs leverage resources and connections to secure funding and shape decision-making, impacting other local and international NGOs. Further research on this power dynamic is crucial for developing policies and interventions that promote financial equity within the NGO sector in conflict-affected regions (Bebbington, Reference Bebbington2004; Stiles, Reference Stiles2002; Suárez & Marshall, Reference Suárez and Marshall2014; Tran & AbouAssi, Reference Tran and AbouAssi2021). This study focuses on Yemen's conflict zones, investigating how ‘Sheikh’ LNGOs influence the financial sustainability and autonomy of smaller NGOs. The main research question is: To what extent do ‘Sheikh’ organizations impact LNGO financial sustainability in Yemen, and what are the broader implications for equitable donor funding? By analyzing power imbalances and funding disparities, this study aims to propose strategies for a more equitable NGO sector, contributing to policy discussions on the need for direct funding mechanisms that support smaller NGOs' autonomy and sustainability.

This research uses a qualitative exploratory approach, drawing on two data sources. Primary data were collected through interviews with 45 administrative staff from a United Nations agency and various NGOs, supplemented by a thorough review of relevant literature and publicly available reports. The study is organized into five interconnected sections. The first section reviews the relevant literature and theoretical frameworks on NGO financial sustainability, introducing the concept of ‘Sheikh’ organizations and analyzing their influence on local entities. The second section provides a contextual overview of Yemen’s NGO landscape, focusing on the unique financial sustainability challenges faced in this setting. The third section outlines the research methodology, followed by an in-depth analysis of the interview findings in the fourth section. Finally, the fifth section concludes with a discussion of key observations and practical recommendations, synthesizing the study’s insights and implications.

Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

This study’s theoretical and conceptual framework draws on various perspectives to address the financial sustainability challenges NGOs face in conflict-affected regions. Financial sustainability, as defined by Lewis (Reference Lewis2011), refers to an NGO’s capacity to consistently secure resources or funding to sustain operations. Stable funding is essential for NGOs to meet community needs and achieve development goals (Bowman, Reference Bowman2011). Scholars like Shava (Reference Shava2021), Karanja and Karuti (Reference Karanja and Karuti2014), and Omeri (Reference Omeri2014) emphasize that NGOs must diversify funding sources to ensure long-term impact and resilience. In regions affected by conflict and economic instability, financial sustainability is even harder to achieve due to heightened security risks, disrupted infrastructure, and shifting donor priorities (Elayah & Verkoren, Reference Elayah and Verkoren2020). These NGOs operate in volatile funding environments that necessitate adaptive strategies, resilience, and innovative fundraising to stay viable. Traditional funding models often fail in such settings, forcing NGOs to seek alternative resources and local partnerships to manage resource constraints effectively (Bowman, Reference Bowman2011). Understanding these dynamics is crucial for creating strategies that allow NGOs to survive financial instability while fulfilling their social objectives.

In conflict zones, NGOs often rely heavily on foreign aid, which significantly impacts their financial stability. Dependency on external funding leaves NGOs vulnerable to donor priority shifts and external shocks (Lewis, Reference Lewis2011). Donors frequently prefer well-established organizations, seen as more reliable and accountable, which centralizes funding within a select group of influential ‘Sheikh’ NGOs—large, powerful local entities with established donor networks and connections. This preference allows ‘Sheikh’ NGOs to capture most foreign aid, leaving smaller NGOs with limited access and increasing their dependency on these intermediaries (Gedeon, Reference Gedeon2021). The gatekeeping role of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs worsens this dependency. These organizations determine which smaller NGOs receive funding and under what conditions, wielding significant control over resource distribution. This intermediary function mirrors larger power dynamics in the NGO sector, where well-established organizations dominate resource flows, restricting smaller NGOs’ autonomy (ICVA, 2021; OCHA, 2022). The gatekeeping perpetuates a dependency cycle, inhibiting smaller NGOs from developing direct donor relationships and weakening their financial independence (Waiganjo et al., Reference Waiganjo, Ngethe and Mugambi2012).

This centralization of funding among a few dominant players creates substantial obstacles for smaller LNGOs. Limited funding restricts their autonomy and capacity to address specific community needs, forcing many to operate as subcontractors under larger NGOs, whose programs may not fully align with local priorities (Elayah et al., Reference Elayah, Al-Sameai, Khodr and Gamar2024). Without direct funding, smaller LNGOs struggle to establish sustainable financial models, retain skilled personnel, or expand their capacity to address Yemen’s growing humanitarian crisis.

The funding imbalance perpetuates a cycle of dependency, with smaller LNGOs reliant on intermediaries to access resources. This reliance limits their autonomy and undermines the goal of aid localization—a central aim of global humanitarian frameworks seeking to empower local actors to lead relief efforts. Without equitable funding, Yemen’s NGO sector risks continued domination by a select few, hindering the diversity, innovation, and resilience needed to address the country’s complex humanitarian challenges. Established international NGOs, which benefit from longstanding donor relationships, capture a disproportionate share of funding, overshadowing local organizations (Tamdeen Youth Foundation, 2022). Additionally, donors favor NGOs with six to ten years of establishment, further disadvantaging newer organizations that lack the resources to navigate complex application processes (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Zainol and Mokhtar2022; Alqatabry & Butcher, Reference Alqatabry and Butcher2020). Despite global initiatives to direct resources to LNGOs, intermediaries often manage these funds, distancing LNGOs from direct donor support and reinforcing dependency on established gatekeepers (ICVA, 2021).

Research shows that ‘Sheikh’ NGOs dominate aid distribution in conflict zones, putting smaller organizations at a disadvantage. Elkahlout et al. (Reference Elkahlout, Milton, Yaseen and Raweh2022) observe that international donors prefer ‘Sheikh’ NGOs for their established grant management systems and risk mitigation capacities, relegating smaller NGOs to subcontractor roles that limit their agency. These smaller NGOs often end up working on projects set by ‘Sheikh’ NGOs rather than initiating their own (Davis & Swiss Reference Davis and Swiss2020; Saungweme, Reference Saungweme2014). The competitive imbalance between ‘Sheikh’ NGOs and smaller organizations has substantial implications for the latter’s financial sustainability. Without resources to meet operational standards set by larger entities, smaller NGOs struggle to qualify for direct funding. Davis (Reference Davis2019) highlights stark disparities in compensation and resources between ‘Sheikh’ NGOs and smaller local entities, which exacerbates inequalities in the sector. These disparities reduce smaller NGOs’ capacity to attract skilled personnel and develop the internal infrastructure needed to secure independent funding.

The reliance on ‘Sheikh’ NGOs and foreign aid severely impacts smaller NGOs' financial independence. Most LNGOs cannot secure independent funding, forcing them to operate within the frameworks of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs and align their objectives with those of larger organizations. This alignment restricts smaller NGOs’ capacity to address community-specific needs, marginalizing their role in local development (Lewis, Reference Lewis2011). Furthermore, the concentration of resources among a few large organizations reinforces power imbalances, making it challenging for smaller NGOs to compete for funding and limiting the potential for aid localization and equitable resource distribution (OCHA, 2022). Studies indicate that the gatekeeping role of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs presents risks to the diversity and adaptability of the NGO sector. When resources are concentrated in a few organizations, grassroots initiatives and innovative approaches often remain underfunded, limiting the sector’s responsiveness to community needs. In conflict-affected regions, where localized responses are essential for addressing pressing humanitarian challenges, the dominance of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs stifles the emergence of a diversified, resilient NGO ecosystem. This centralization limits the sector’s capacity to adapt and respond effectively to local issues (Elkahlout et al., Reference Elkahlout, Milton, Yaseen and Raweh2022; Adem et al., Reference Adem, Childerhouse, Egbelakin and Wang2018).

The structural inequalities created by the dominance of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs resemble the authority held by traditional tribal leaders, where influential NGOs leverage their reputation to attract donor support and act as intermediaries (Elayah et al., Reference Elayah, Abu-Osba and Al-Majdhoub2018). However, this dominance marginalizes smaller NGOs, as resources predominantly flow to entities with robust financial and managerial systems (Amegboh, Reference Amegboh2021). This setup creates an environment where a few organizations control donor funding, restricting equitable sectoral growth and diversity. Donor biases in favor of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs and international organizations disadvantage LNGOs due to differences in capacity and reputation (Davis & Swiss, Reference Davis and Swiss2020); Zuka, Reference Zuka2022). Addressing these imbalances requires strategies that support the financial sustainability of smaller NGOs, enabling them to operate as equal partners rather than subcontractors (Waiganjo et al., Reference Waiganjo, Ngethe and Mugambi2012). This shift would involve creating pathways for LNGOs to access direct funding, build capacity, and become competitive players in the NGO sector.

This theoretical and conceptual framework provides insights into the financial sustainability challenges of LNGOs in conflict-affected regions, focusing on the role of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs as gatekeepers. This study shows how the dominance of larger organizations perpetuates dependency, limiting smaller NGOs’ financial autonomy and stifling innovation. In integrating dependency theory and collective impact theory, this study calls for a reconfiguration of roles in the NGO sector, advocating for a shift from gatekeeping to collaboration. To foster a more equitable and resilient NGO landscape, donor strategies should prioritize direct funding and capacity-building initiatives that empower local organizations, allowing them to effectively address complex challenges in conflict-affected regions like Yemen.

Setting the Context: Yemeni NGO Landscape

Since the conflict erupted in 2015, Yemen has witnessed a transformation in its NGO landscape, marked by a significant increase in national and local organizations aiming to address escalating humanitarian needs (Elayah & Verkoren, Reference Elayah and Verkoren2020; SIDA, 2018). Prior to the conflict, Yemen had a limited NGO presence, primarily consisting of eight UN agencies and around 34 international NGOs. Following the conflict, over 98 local organizations emerged to meet the urgent demands of affected communities (SIDA, 2018). However, despite this growth, funding remains heavily skewed toward international NGOs and a few powerful local ‘Sheikh’ organizations. According to OCHA (2022), less than 2% of total humanitarian aid in 2022 was allocated directly to LNGOs, with over 75% of that limited pool directed to just four prominent ‘Sheikh’ organizations. Consequently, most LNGOs operate with minimal support, even though they are often closer to communities and better equipped to provide rapid, localized aid.

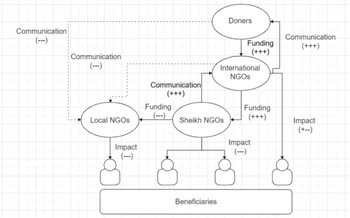

A shift toward remote management has strained collaborations with LNGOs, favoring international organizations (Alhakimi & Olyan, Reference Alhakimi and Olyan2022). Figure 1 illustrates the power imbalance in financial decision-making, highlighting the challenges to participatory engagement (ICVA, 2021). Most LNGOs depend on donor funds for stability (Elayah, Reference Elayah2023), and although some secure funding from the private sector, their operational stability and capacity heavily rely on external support, making them vulnerable (Elayah & Schulpen, Reference Elayah and Schulpen2016). Addressing these imbalances requires fundamental changes in donor strategies to ensure direct support for smaller LNGOs, reducing reliance on intermediaries. This shift should not only increase direct funding, but also emphasize capacity-building, accountability, and an environment that nurtures long-term growth and autonomy for LNGOs. Empowering Yemen’s LNGOs to manage resources independently and establish direct donor relationships is crucial for their transformation from dependent aid recipients to proactive agents of sustainable change.

Fig. 1 Conceptual framework of financial sustainability and impact dynamics.

The conceptual framework emphasizes the financial disparities among post-2015 Yemeni NGOs. ‘Sheikh’ NGOs, with significant financial resources, often dominate the funding landscape, raising questions about fund allocation and the broader implications for the NGO sector (AbouAssi, Reference AbouAssi2013). In contrast, LNGOs face considerable funding constraints, highlighting the need to explore the financial sustainability challenges unique to each category (Schulpen & van Kempen, Reference Schulpen and van Kempen2020). In Yemen’s conflict-affected environment, these disparities underscore the critical need to understand the structural and systemic factors influencing financial resource distribution and sustainability (Alqatabry & Butcher, Reference Alqatabry and Butcher2020).

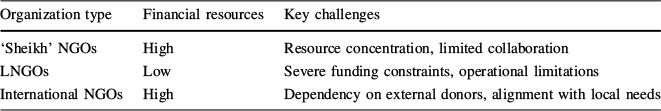

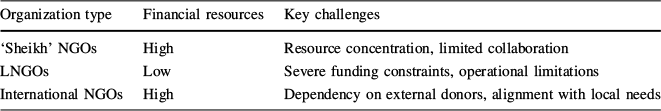

As Table 1 illustrates, the framework focuses on financial capacity as a determinant of operational challenges and strategic priorities for NGOs in Yemen. A nuanced understanding of these dynamics can inform strategies to address financial inequities and strengthen the overall resilience of Yemen’s NGO sector.

Table 1 Elements of the asymmetry in funding

Organization type |

Financial resources |

Key challenges |

|---|---|---|

‘Sheikh’ NGOs |

High |

Resource concentration, limited collaboration |

LNGOs |

Low |

Severe funding constraints, operational limitations |

International NGOs |

High |

Dependency on external donors, alignment with local needs |

Source: The authors

The table illustrates the financial dynamics and key challenges faced by different types of NGOs operating in Yemen. ‘Sheikh’ NGOs possess high financial resources, which often result in resource concentration and limited collaboration with smaller entities. LNGOs, on the other hand, face severe funding constraints that restrict their operational capabilities. International NGOs, despite their high funding levels, encounter challenges related to dependency on external donors and difficulties in aligning their resources with local needs. This framework emphasizes the need to address financial disparities and foster collaborative strategies among different NGO types. Strengthening partnerships and creating mechanisms for equitable resource distribution are critical steps toward building a resilient and sustainable NGO sector in Yemen.

In fostering partnerships between local and international NGOs, donors can create a more sustainable NGO ecosystem that leverages collective resources and expertise to address post-conflict challenges comprehensively. Collaborative efforts lay a foundation for long-term resilience and positive change, transcending immediate project goals to foster inclusive development. Such partnerships are critical for creating a self-sufficient and resilient NGO landscape in Yemen, promoting enduring progress beyond individual initiatives (Elayah, Reference Elayah2023).

Methodology

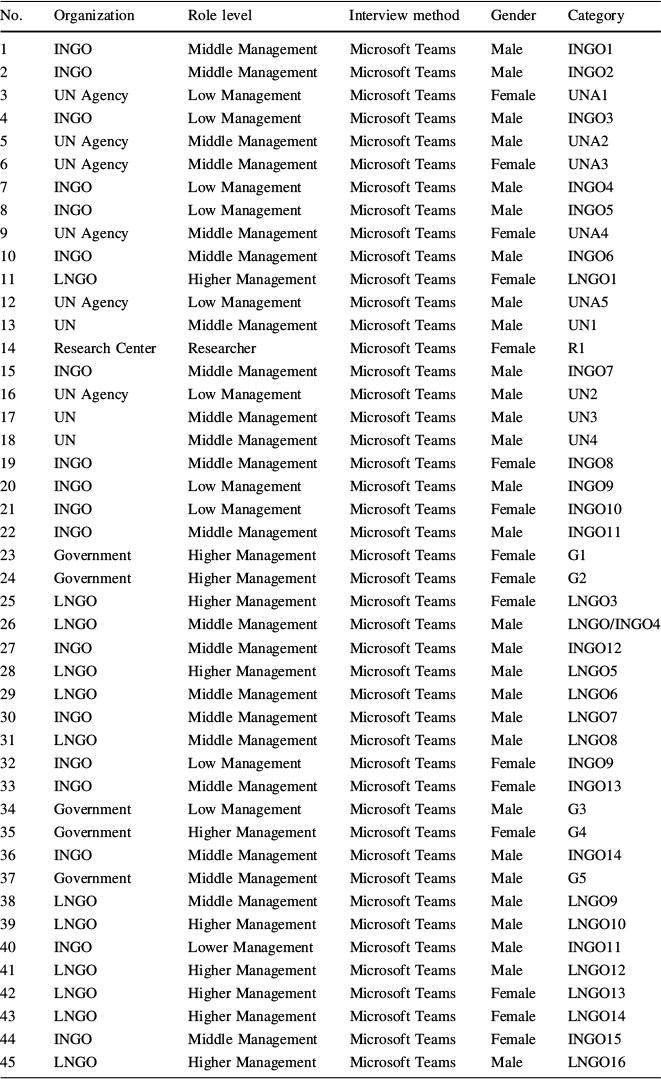

This study adopts a qualitative research design to explore the financial sustainability challenges facing Yemeni NGOs and the influence of ‘Sheikh’ organizations as financial gatekeepers. Data were collected through 45 semi-structured interviews conducted from April 20, 2023, to March 27, 2023. Participants included administrative staff from UN agencies, international and local Yemeni NGOs, government officials, and researchers. A purposeful sampling method was used to select individuals with expertise in donor relations, funding allocation, and partnership dynamics, allowing for a range of perspectives on the impact of larger NGOs on the financial stability of local organizations. To provide a comprehensive analysis, data collection was complemented by a review of literature, donor funding reports, and other relevant documents, allowing for an in-depth exploration of sustainability factors affecting Yemeni NGOs (Simons, Reference Simons2009; Rivera, Reference Rivera2020).

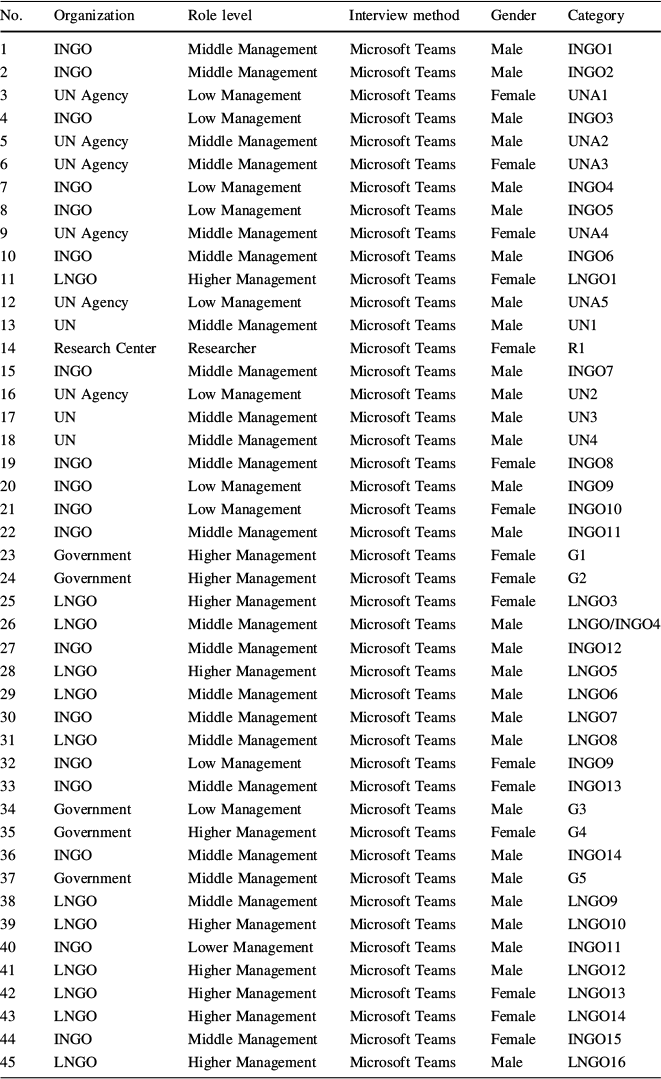

Based on Table 2 participants were categorized by organization type, role, interview method, gender, and organization affiliation (e.g., INGO, LNGO, UN Agency, and Government). This categorization ensured a diverse range of perspectives, capturing insights from both international and LNGOs, as well as UN agencies and government representatives. Such diversity in participant roles reflects the complex landscape of Yemen’s NGO sector, providing a wide array of perspectives on funding, management, and partnership practices in the region. Purposeful sampling was employed to focus on participants with roles in financial sustainability, partnership development, and donor relations. Out of an initial pool of 119 potential interviewees, 45 were selected to ensure diverse representation across local and international NGOs, United Nations agencies, and government bodies. This approach captured a variety of perspectives from key stakeholders in Yemen’s NGO sector, ensuring that insights were drawn from individuals with a deep understanding of financial sustainability and partnership development within NGOs.

Table 2 Overview of the key informants

No. |

Organization |

Role level |

Interview method |

Gender |

Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

INGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

INGO1 |

2 |

INGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

INGO2 |

3 |

UN Agency |

Low Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

UNA1 |

4 |

INGO |

Low Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

INGO3 |

5 |

UN Agency |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

UNA2 |

6 |

UN Agency |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

UNA3 |

7 |

INGO |

Low Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

INGO4 |

8 |

INGO |

Low Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

INGO5 |

9 |

UN Agency |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

UNA4 |

10 |

INGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

INGO6 |

11 |

LNGO |

Higher Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

LNGO1 |

12 |

UN Agency |

Low Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

UNA5 |

13 |

UN |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

UN1 |

14 |

Research Center |

Researcher |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

R1 |

15 |

INGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

INGO7 |

16 |

UN Agency |

Low Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

UN2 |

17 |

UN |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

UN3 |

18 |

UN |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

UN4 |

19 |

INGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

INGO8 |

20 |

INGO |

Low Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

INGO9 |

21 |

INGO |

Low Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

INGO10 |

22 |

INGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

INGO11 |

23 |

Government |

Higher Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

G1 |

24 |

Government |

Higher Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

G2 |

25 |

LNGO |

Higher Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

LNGO3 |

26 |

LNGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

LNGO/INGO4 |

27 |

INGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

INGO12 |

28 |

LNGO |

Higher Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

LNGO5 |

29 |

LNGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

LNGO6 |

30 |

INGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

LNGO7 |

31 |

LNGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

LNGO8 |

32 |

INGO |

Low Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

INGO9 |

33 |

INGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

INGO13 |

34 |

Government |

Low Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

G3 |

35 |

Government |

Higher Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

G4 |

36 |

INGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

INGO14 |

37 |

Government |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

G5 |

38 |

LNGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

LNGO9 |

39 |

LNGO |

Higher Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

LNGO10 |

40 |

INGO |

Lower Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

INGO11 |

41 |

LNGO |

Higher Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

LNGO12 |

42 |

LNGO |

Higher Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

LNGO13 |

43 |

LNGO |

Higher Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

LNGO14 |

44 |

INGO |

Middle Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Female |

INGO15 |

45 |

LNGO |

Higher Management |

Microsoft Teams |

Male |

LNGO16 |

INGO international nongovernmental organization, LNGO local nongovernmental organization, UNA United Nations Agency, R research center, G governmental agency

The semi-structured interviews were designed to balance flexibility with a structured approach to core themes. Interview questions centered on three main areas: the financial sustainability of LNGOs, the influence of international NGOs on LNGO funding, and the role of partnerships in achieving sustainability. To enhance data reliability, participants were invited to review their interview transcripts through a member-checking process, ensuring the accuracy of their perspectives. Pilot interviews with a small group of NGO administrators further refined the interview questions, ensuring clarity and relevance for the main data collection (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Zainol and Mokhtar2022; Alqatabry & Butcher, Reference Alqatabry and Butcher2020; Tamdeen Youth Foundation, 2022).

For data analysis, a thematic analysis approach based on Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2019) six-stage process was utilized. The process began with familiarization, where interview transcripts were read thoroughly, and initial observations were noted. Next, recurring patterns related to financial sustainability, donor dependency, and the influence of ‘Sheikh’ organizations were identified and coded systematically. These initial codes were organized into broader themes, including “Funding Disparities,” “Dependency on Donors,” and “Opportunities for Partnerships.” Each theme was then reviewed and refined to ensure alignment with the study’s objectives, with overlapping themes merged or removed where necessary.

In the subsequent stages, themes were clearly defined, and subthemes were developed to capture specific insights. For example, under the theme “Funding Disparities,” subthemes like “‘Sheikh’ Organizations’ Dominance” and “Donor Prioritization” emerged. Finally, the results of the thematic analysis were synthesized and linked to the study’s research questions and theoretical frameworks, particularly dependency theory and collective impact theory, to provide a structured analysis of the findings (Gedeon, Reference Gedeon2021; ICVA, 2021).

NVivo software was used for systematic coding, organizing data into primary themes and subthemes. Interview transcripts were reviewed meticulously, with key quotes highlighted to illustrate important points. Multiple rounds of coding were conducted to ensure consistency, and any discrepancies were resolved through team discussions. This coding process was grounded in the study’s theoretical framework, rigorously examining themes associated with dependency theory, collective impact theory, and the role of ‘Sheikh’ organizations as gatekeepers (Elayah & Verkoren, Reference Elayah and Verkoren2020; OCHA, 2022).

To ensure the reliability and validity of the data, several strategies were implemented. Triangulation was applied by cross-referencing interview data with findings from reports, literature, and document analysis, which helped validate the results and reduce bias. Reflexivity was maintained throughout the process, with researchers regularly reflecting on their potential biases to mitigate their influence on data interpretation. Peer debriefing sessions were also conducted, allowing the research team to review coding decisions and interpretations to maintain an objective, data-driven analysis (Bowman, Reference Bowman2011; Shava, Reference Shava2021). Despite the study’s methodological rigor, certain limitations are acknowledged. The sample size of 45 respondents, out of 119 contacted, may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, Yemen’s complex political environment posed challenges in accessing some stakeholders, especially in politically fragmented regions. Nevertheless, the study’s carefully designed methodology and validation processes contribute to the reliability of the findings, enriching the discourse on financial sustainability within Yemen’s NGO sector (Rivera, Reference Rivera2019; Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Zainol and Mokhtar2022; Amegboh, Reference Amegboh2021; Zuka, Reference Zuka2022).

Analysis and Findings

This study’s findings center on three key themes: the financial sustainability challenges and the gatekeeping role of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs, the asymmetry of funding distribution and its implications, and the potential for transformative partnerships to foster collective impact and resilience among Yemeni NGOs. Despite their reliance on ‘Sheikh’ NGOs, some local organizations are working toward self-sufficiency, though these efforts often require first proving reliability under ‘Sheikh’ NGO guidance. Establishing direct donor relationships is gradual and challenging, as smaller NGOs must build credibility through ‘Sheikh’ NGO partnerships before independently approaching donors. "The process mirrors Dependency Theory," explained one respondent…"We start by relying on ‘Sheikh’ NGOs but hope to eventually establish direct ties with donors" (LNGO3). Few LNGOs manage to shift from dependency to self-sufficiency, typically by demonstrating impact within ‘Sheikh’ NGO-funded projects. "The ‘Sheikh’ NGOs give us credibility with donors," shared a respondent, …"but that dependency also keeps us tied to them." (LNGO5). Another added, "It’s a Catch-22Footnote 1: working with ‘Sheikh’ NGOs opens doors, but also binds us to their approval." This delicate balance reflects a gradual shift toward independence, as observed in Marley’s (Reference Marley2015) study on conflict-area NGOs, where credibility is a key to autonomy. However, breaking the dependency cycle remains challenging, as smaller NGOs are continually pulled back into reliance on ‘Sheikh’ NGOs.

For most LNGOs, true autonomy remains elusive as dependency on ‘Sheikh’ NGOs continues to dominate their operations. “If it weren’t for ‘Sheikh’ NGOs, we wouldn’t survive,” one respondent admitted, adding, “but the cost of that survival is our independence” (LNGO2). This reliance not only ensures financial support, but also cements a hierarchy that prevents smaller NGOs from becoming self-reliant entities capable of meeting local needs without external control. “The dependency system keeps us in their shadow, unable to establish ourselves as independent players,” remarked one participant (LNGO3). This entrenched hierarchy centralizes resources and influence among a few dominant ‘Sheikh’ NGOs, limiting smaller organizations’ growth and impact. The journey to self-sufficiency for LNGOs remains a complex balancing act. While dependency on ‘Sheikh’ NGOs provides short-term stability, it constrains long-term development, leaving most smaller NGOs as subordinates rather than independent agents of change. This highlights the need for donor strategies that support direct funding and capacity-building, enabling LNGOs to build resilience and reduce dependency. Without such shifts, the structural reliance on ‘Sheikh’ NGOs will likely persist, reinforcing a system where only a few achieve financial sustainability, while the majority remain tied to larger entities' agendas.

Financial Sustainability Challenges and the Role of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs as Gatekeepers

The financial landscape for Yemeni NGOs is shaped by conflict, economic instability, and declining donor support. Despite high demand for services, LNGOs struggle to secure sustainable funding. Many participants highlighted ongoing challenges to maintain operations amid shrinking resources. “LNGOs are constantly struggling to make ends meet, with economic conditions and political instability making sustainability a near-impossible task,” noted one respondent (LNGO9). Another added, “Our programs are at the mercy of the next grant; if that funding doesn’t come through, everything falls apart” (LNGO11). This aligns with Bowman’s (Reference Bowman2011) findings that NGOs in crisis zones are especially vulnerable to funding disruptions. Most Yemeni NGOs rely on self-funding, small donations, and local business contributions, restricting them to short-term, small-scale projects. “The lack of reliable funding sources leaves us constantly on edge, just trying to keep our programs running day-to-day,” said one participant. This funding instability hampers long-term planning and sustainable development. Another respondent added, “Without a diversified funding, base, it’s like we’re on a lifeline, dependent on occasional donor support” (LNGO13). This reliance on sporadic funding echoes Lewis (Reference Lewis2011) and Marley (Reference Marley2015), who emphasize that diversified funding, is crucial but remains out of reach for many Yemeni NGOs.

International aid, though essential, is also unstable. “International aid is not guaranteed, and in Yemen’s situation, it can be cut off with little notice due to geopolitical shifts,” explained one respondent (UNA5). The withdrawal of international donors exacerbates financial insecurity, forcing NGOs to scale back or halt operations. “When international donors pull out, we’re left with nothing,” Yemen’s economic challenges, including inflation and currency depreciation, further limit local donations…added, “Even if we wanted to rely more on local donations, people are just too poor to give” (LNGO6). This dependency on external funding limits NGOs to addressing urgent needs rather than systemic, long-term issues. “We’re always putting out fires,” said one respondent (LNGO1), highlighting how funding uncertainty prevents capacity-building and keeps NGOs dependent on external support.

LNGOs also face significant competition from INGOs for scarce resources. Many participants expressed frustration over donors’ preference for INGOs, often viewed as more reliable or capable. “It feels like INGOs get the priority because they’re seen as more reliable,” (UN2). Unlike INGOs, LNGOs lack global visibility and established donor networks, putting them at a disadvantage. “We are the ones on the ground, with direct relationships and understanding of the people we serve, but it’s the INGOs that secure the funds” (LNGO7). This marginalization reinforces LNGOs’ dependency on INGOs as intermediaries, limiting both their financial sustainability and autonomy.

Administrative demands and reporting standards from international donors impose additional burdens on smaller NGOs. Many participants noted these complex requirements are difficult to meet without robust administrative infrastructure. “The reporting standards required by some donors are just beyond our capacity,” …added, “It’s hard to compete for international funds when you lack resources to manage bureaucratic requirement” (LNGO2). This capacity gap, coupled with limited resources, creates a paradox: NGOs best positioned to address local issues are often least likely to secure funding. “If we had the funding, we could build capacity, but without capacity, we can't access funding” (LNGO8), underscoring a cycle of dependency and fragility. This situation mirrors Davis (Reference Davis2019), who highlights that NGOs in fragile states often face barriers to funding due to limited internal capacity.

Financial challenges also impact human resources, as unstable funding makes it difficult to retain skilled staff. "We lose our best people to INGOs or other sectors that can pay more"(LNGO13). This turnover disrupts institutional knowledge and forces NGOs to continuously train new staff, impacting program continuity and effectiveness. “Every time we lose staff, we lose valuable experience, and our programs suffer” (LNGO11). The inability to retain experienced personnel also impacts donor perceptions, with high turnover raising concerns about NGOs’ management capacity, potentially limiting future funding opportunities (Davis, Reference Davis2019).

The Role of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs and the Asymmetry of Funding Distribution

The study reveals a notable asymmetry in funding distribution within Yemen’s NGO sector, with ‘Sheikh’ NGOs in control of most of the foreign aid. These larger, well-established organizations hold significant influence due to their stable networks and reputation, effectively monopolizing resources. "Funding is essentially monopolized by ‘Sheikh’ NGOs, and smaller organizations like ours are left to survive on whatever trickles down"(LNGO9). This structure creates a significant barrier for smaller NGOs trying to achieve financial sustainability, as they are forced to rely on whatever limited resources are available after larger organizations are funded.

‘Sheikh’ NGOs’ dominance extends beyond funding control, shaping the operational framework for smaller NGOs. "They don’t just control the funds—they control how we operate," one participant shared, highlighting the lack of autonomy (LNGO7). "If we want any funding, we have to align our goals with theirs." Another respondent echoed, "It’s like we’re subcontractors rather than independent NGOs, forced to work on their terms, not ours" (LNGO3). This dynamic mirrors dependency theory’s financial gatekeeping concept, where reliance on powerful intermediaries reinforces hierarchies and restricts autonomy (Elayah & Verkoren, Reference Elayah and Verkoren2020). This dependency limits smaller NGOs' capacity to address specific community needs, as they must prioritize ‘Sheikh’ NGOs’ agendas over their own missions. "To secure funding, we sacrifice our objectives and adopt those set by ‘Sheikh’ NGOs," noted one respondent, underscoring the constrained agency within the sector. Another added, "We’re forced to fit our objectives to the ‘Sheikh’ NGOs’ agenda, even if it means neglecting essential community needs." This alignment limits smaller NGOs’ innovation and ability to address local issues independently, hindering financial resilience and effective community impact.

‘Sheikh’ NGOs further constrain smaller NGOs by acting as gatekeepers to foreign aid through established donor networks. “‘Sheikh’ NGOs hold the purse strings, and if we don’t align with them, we’re out of luck” (LNGO16). This dependency reduces smaller NGOs' ability to establish independent credibility with donors, perpetuating reliance on intermediaries even when they have skilled teams and impactful projects. ‘Sheikh’ NGOs’ role as gatekeepers reinforces dependency theory, where powerful intermediaries maintain hierarchies that constrain dependent entities (Elayah & Verkoren, Reference Elayah and Verkoren2020). Many participants viewed ‘Sheikh’ NGOs not just as intermediaries but as gatekeepers, whose influence is difficult to bypass. “Our success depends on whether a ‘Sheikh’ NGO lets us lead or prefers to control” (LNGO11), underscoring how this reliance restricts smaller NGOs’ autonomy and growth potential.

Balancing Influence and Financial Sustainability in ‘Sheikh’ NGO Partnerships

While ‘Sheikh’ NGOs often restrict the autonomy of smaller NGOs, respondents acknowledged that these larger entities provide stability and resources. Many suggested that ‘Sheikh’ NGOs should shift from controlling roles to becoming collaborators, helping smaller NGOs build capacity for independent operation. "‘Sheikh’ NGOs need to help smaller organizations grow, not just keep them dependent," noted one participant (LNGO5), underscoring the importance of reorienting ‘Sheikh’ NGOs as facilitators of financial sustainability. Examples of successful partnerships exist, such as the Youth Leadership Development Foundation’s work with "Girls of Hodeida," which helped connect them directly to international donors. Described as "a breakthrough," this collaboration enabled smaller NGOs to showcase their capabilities without intermediaries. Such partnerships align with collective impact theory, which emphasizes that shared objectives and resources between larger and smaller organizations enhance the capacity and impact of the NGO sector (Francois, Reference Francois2014).

However, successful collaborations are rare. For many LNGOs, dependency on ‘Sheikh’ NGOs persists, with the larger entities prioritizing control over empowerment. "If ‘Sheikh’ NGOs prioritized empowerment, the whole sector could benefit," noted one participant, … added "We need ‘Sheikh’ NGOs to see us as partners, not subcontractors" (LNGO14). This shift would require ‘Sheikh’ NGOs to adopt a facilitative role, providing tools and support for smaller NGOs to build direct donor relationships, enhance internal capacity, and pursue projects aligned with local needs. By transitioning from gatekeepers to collaborators, ‘Sheikh’ NGOs could help establish a more balanced and resilient NGO ecosystem in Yemen, empowering smaller organizations to address the country’s complex humanitarian challenges effectively.

The Competitive Landscape of Foreign NGOs and its Impact on LNGOs

The strong presence of international NGOs (INGOs) in Yemen significantly impacts the financial landscape for LNGOs, creating a competitive environment that challenges their sustainability. Many respondents highlighted a donor preference for INGOs, perceived as more capable due to their size and reputation. “There’s a clear bias toward INGOs,” … “Donors assume they’re more capable because of their size and reputation” (UNA4). This perception skews resource distribution, limiting LNGOs’ access to essential funding. “Our deep understanding of local needs is often overlooked because donors think INGOs are better equipped, even when we’re the ones who truly know the community” (LNGO12). This tendency to prioritize INGOs creates a disadvantage for LNGOs, despite their firsthand knowledge and community connections. “We’re always competing for the same funds, but INGOs have the advantage of established donor networks” (INGO3), noting the competitive edge INGOs hold through these relationships. Marley (Reference Marley2015) documents this common trend in conflict regions, where INGOs benefit from scale, resources, and recognition that LNGOs lack.

Many LNGO representatives expressed frustration that their deep community insights are often undervalued compared to the perceived professionalism of INGOs. “We know the specific needs of our communities, but donors tend to prioritize INGOs, assuming they’re better just because they’re bigger”, one participant explained (LNGO2). Another added, “We work closely with communities daily, but that doesn’t seem to matter as much to donors as the INGOs’ track record” (LNGO6). This competition not only limits LNGOs’ funding, but also their ability to lead projects addressing local needs, often reducing them to subcontractor roles. “We’re asked to partner with INGOs because donors feel more comfortable funding through them, but this often means we end up supporting their projects instead of our own priorities” (LNGO13), a respondent noted, describing how INGOs dominate project agendas. Additionally, international donors’ stringent administrative requirements further disadvantage smaller NGOs lacking resources to fulfill these demands. “The reporting standards required by some donors are beyond our capacity, …. “We don’t have the staff or systems to meet those demands, so we’re often disqualified from funding opportunities from the outset” (LNGO8). INGOs’ administrative capacity and donor networks create an environment where LNGOs are overshadowed, even if more attuned to community needs. As one respondent noted, “If donors valued local knowledge and impact as much as they value size and reputation, the funding landscape would look very different” (INGO6).

Potential for Transformative Partnerships: Collective Impact in Action

In Yemen's challenging NGO landscape, successful partnerships demonstrate the potential of collaboration when ‘Sheikh’ NGOs and INGOs shift from controllers to facilitators. The partnership between the Youth Leadership Development Foundation and “Girls of Hodeida” exemplifies this approach, showing how strategic support can empower LNGOs to operate independently. “Through this partnership, we were able to showcase our capabilities to international donors directly,” shared one participant, highlighting ‘Sheikh’ NGOs’ ability to enhance local organizations’ visibility and credibility (LNGO1). These partnerships align with collective impact theory, which stresses the strength of joint efforts toward shared goals. Support from the Youth Leadership Development Foundation helped smaller NGOs build credibility, access resources, and establish direct relationships with international donors. “If more ‘Sheikh’ NGOs acted like the Youth Leadership Foundation, we could see real change in the sector,” noted one participant, suggesting that such partnerships foster resilience and enable smaller NGOs to achieve financial sustainability.

A key factor in these successful partnerships is the mutual recognition of strengths. ‘Sheikh’ NGOs provide established networks and donor relations, while LNGOs bring deep community knowledge. “When ‘Sheikh’ NGOs trust us to lead, we can implement projects that truly address community needs rather than following someone else’s agenda” (INGO3). This model allows LNGOs to focus on their strengths and community engagement while ‘Sheikh’ NGOs handle administrative challenges. Another participant shared, “Having the backing of a ‘Sheikh’ NGO allows us to focus on what we do best—serving our community—while they handle the bureaucratic side” (INGO5). This division of roles not only increases efficiency, but also enables LNGOs to build capacity sustainably. However, these transformative partnerships remain exceptions. Many ‘Sheikh’ NGOs still act as gatekeepers, limiting LNGOs’ opportunities and reinforcing dependency. “Too often, ‘Sheikh’ NGOs still act as gatekeepers, limiting our opportunities” (R1). A paradigm shift is essential, with ‘Sheikh’ NGOs moving from gatekeeping to empowering roles. Embracing collective impact theory can foster a more equitable and resilient NGO sector, empowering local organizations to address Yemen’s urgent needs effectively. In creating an environment where LNGOs can grow independently yet with collaborative support, the sector can advance toward sustainable growth and greater self-reliance.

Discussion and Theoretical Reflection

The findings of this study highlight the critical role of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs as financial gatekeepers in Yemen’s NGO sector, showing how their control over aid distribution reinforces dependency and limits the autonomy of LNGOs. This mirrors global trends in conflict-affected regions, where established organizations dominate funding landscapes, often sidelining smaller, local entities. As one participant observed, “Funding is essentially monopolized by ‘Sheikh’ NGOs, leaving smaller organizations like ours to survive on whatever trickles down” (R1). This statement underscores the barriers LNGOs face in building their own identities and capacities within the broader humanitarian ecosystem. These dynamics align with dependency theory, which suggests that reliance on intermediaries perpetuates power imbalances and dependency among less powerful entities (Elayah & Verkoren, Reference Elayah and Verkoren2020; Lewis, Reference Lewis2011). ‘Sheikh’ NGOs, with their established networks, dominate foreign aid distribution, effectively deciding which organizations receive funding and under what conditions. This gatekeeping restricts LNGOs’ operational flexibility and stifles innovation and responsiveness to community needs. “To secure funding, we have to sacrifice our own mission objectives and adopt the priorities set by ‘Sheikh’ NGOs,” one respondent noted (LNGO9), reflecting how dependency forces LNGOs to align with funders’ goals at the expense of their core missions. This reliance perpetuates financial instability, as many LNGOs struggle to form direct donor relationships, depending instead on ‘Sheikh’ NGOs as intermediaries. “We are almost invisible to international donors unless a ‘Sheikh’ NGO vouches for us,” shared one participant (LNGO3), highlighting how this reliance limits their credibility and autonomy. As a result, local organizations remain trapped in a cycle of dependency, where their survival hinges on ‘Sheikh’ NGOs, reinforcing a power structure that marginalizes their contributions and restricts their growth potential.

For Yemen’s NGO sector to thrive, a fundamental reconfiguration of roles is essential. ‘Sheikh’ NGOs need to transition from gatekeepers to facilitators, actively supporting smaller NGOs in capacity-building and establishing direct donor relationships. As one participant proposed, “‘Sheikh’ NGOs need to help smaller organizations grow, not just keep them dependent” (R1). This shift is critical for fostering a resilient, diverse sector capable of addressing Yemen’s complex humanitarian needs.

The successful partnership between the Youth Leadership Development Foundation and smaller NGOs, such as “Girls of Hodeida,” illustrates the potential of this collaborative approach. “Through this partnership, we were able to showcase our capabilities to international donors directly,” a participant noted (LNGO4), underscoring the impact of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs adopting an empowering stance. Such partnerships reflect collective impact theory, which emphasizes the potential of organizations working together toward shared objectives (Kania & Kramer, Reference Kania and Kramer2011). Through the Foundation’s support, smaller NGOs gained credibility, resources, and direct donor access, demonstrating how a shift from gatekeeping to facilitation could transform Yemen’s NGO sector.

However, these collaborative partnerships are still rare. Many respondents voiced frustration over the continuing dominance of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs, which often prioritize control over empowerment. “If ‘Sheikh’ NGOs were more focused on empowerment rather than control, the whole sector could benefit,” remarked one participant …added, “The NGO sector in Yemen could be much stronger if ‘Sheikh’ NGOs shifted from gatekeepers to partners in development” (LNGO5). This sentiment highlights the need for a role shift where ‘Sheikh’ NGOs adopt a collaborative, supportive approach to strengthen the sector’s resilience and autonomy.

Addressing these structural challenges requires coordinated efforts from all stakeholders. Donors need to reconsider funding strategies to emphasize direct funding and capacity-building initiatives that promote LNGOs’ autonomy. Studies show that fostering local capacity and reducing reliance on international aid are essential for NGO sustainability in fragile contexts (Lewis, Reference Lewis2011; Marley, Reference Marley2015). Empowering local organizations and ensuring equitable access to resources can significantly strengthen the NGO sector’s resilience. Increased collaboration and resource-sharing among NGOs is also essential. “The NGO sector can achieve so much more if we work together instead of competing for the same limited funds,” noted one respondent (LNGO1), echoing collective impact theory, which supports collaborative frameworks to achieve greater outcomes (Francois, Reference Francois2014). ‘Sheikh’ NGOs, by adopting these principles, could transform Yemen’s NGO landscape into a more equitable and effective sector. The future sustainability of Yemen’s NGO sector hinges on shifting from dependency to partnership. Moving from gatekeeping to collaboration would empower local organizations to address Yemen’s complex challenges more effectively, supported by dependency and collective impact theories, which emphasize the importance of collaboration in building a resilient, impactful NGO sector.

This study contributes to NGO discourse in conflict regions by examining the complex relationships among LNGOs, ‘Sheikh’ NGOs, and INGOs. It expands dependency theory, showing how financial intermediaries influence not only funding, but also the operational scope of LNGOs, underscoring the need to reevaluate dependency’s impact on local agency. Additionally, it challenges traditional NGO sustainability models by highlighting the value of collaborative partnerships and shared power, as emphasized in collective impact theory. The study advocates for donor practices that empower LNGOs to lead and innovate within their communities, urging a shift in ‘Sheikh’ and INGOs’ roles in Yemen’s NGO sector. Fostering collaboration, empowerment, and sustainability would create a more resilient framework that enhances LNGOs’ capacity and better meets community needs. Integrating dependency and collective impact theories provide insight into NGO dynamics in conflict settings, suggesting pathways for more effective and sustainable humanitarian action.

Conclusion

This study highlights the significant challenges faced by LNGOs in Yemen, particularly the restrictive role of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs as financial gatekeepers. This dynamic perpetuates dependency, limits the autonomy of smaller organizations, and hinders their ability to address local needs. By examining dependency theory and collective impact theory, this study underscores the need to reconfigure relationships within the NGO sector to foster collaboration, empowerment, and sustainability. Yemen's ongoing humanitarian crisis demands that the sector evolve to meet its communities' needs. For this to happen, ‘Sheikh’ NGOs must shift from gatekeepers to facilitators, actively supporting local organizations in building capacity and establishing direct donor relationships rather than controlling access to resources. Successful partnerships, like those between the Youth Leadership Development Foundation and NGOs such as “Girls of Hodeida,” demonstrate the potential of collaborative models. These partnerships illustrate that empowering LNGOs leads to more effective humanitarian responses. To promote a balanced and resilient NGO framework, stakeholders should prioritize direct funding, capacity-building initiatives, and equitable access to resources. Donors should simplify application processes and offer multiyear funding commitments, providing LNGOs with financial stability for long-term planning. Training in financial management and reporting will further enhance LNGOs’ competitiveness and credibility with international donors.

The role of ‘Sheikh’ NGOs as intermediaries remains essential. While they control resource distribution, their potential to facilitate LNGO growth can be transformative. By providing mentorship in project management and strategic planning, ‘Sheikh’ NGOs can help local organizations develop the necessary infrastructure to thrive. Additionally, creating an environment that values LNGOs’ strengths—such as community knowledge and engagement—can lead to a fairer distribution of resources. As one respondent noted, “When we work together as equals, we can achieve so much more.” ‘Sheikh’ NGOs have an opportunity to reshape their role in Yemen’s NGO sector by fostering local capacity instead of enforcing dependency. This shift requires moving from a gatekeeping mentality to actively supporting LNGOs in building relationships with donors. By assisting smaller organizations with funding applications and providing mentorship, ‘Sheikh’ NGOs can enhance LNGOs’ abilities to secure essential resources. Transparency in funding allocation is another crucial step, as clear criteria enable smaller NGOs to understand the process, compete for resources, and build trust within the sector.

Investing in capacity-building initiatives is vital for strengthening Yemen’s NGO sector. By prioritizing training in project management, financial reporting, and donor relations, ‘Sheikh’ NGOs can build a resilient network of NGOs capable of meeting diverse needs. Promoting collaboration among LNGOs through networking and collective problem-solving can amplify their impact, increase their visibility, and improve funding outcomes. Furthermore, ‘Sheikh’ NGOs should advocate for the recognition of LNGOs, highlighting their unique contributions to ensure donor appreciation of their capacities in addressing community needs. In implementing these strategies, ‘Sheikh’ NGOs can help foster a more equitable and effective NGO sector in Yemen, ultimately leading to sustainable development and resilience for communities across the country.

Future research should examine how shifting ‘Sheikh’ NGOs from gatekeepers to facilitators impacts LNGOs’ autonomy and sustainability. Case studies on successful collaborations could offer insights into sustainable partnership models. Additionally, exploring international donors' perspectives on funding strategies and barriers in conflict zones may reveal ways to simplify funding access for LNGOs. Comparative studies across conflict-affected regions could identify best practices for building resilient NGO sectors in fragile contexts, supporting Yemen’s move toward a more robust, independent NGO landscape.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Data Availability

Due to the nature of the research, supporting data are not available.