1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, wheeled autonomous mobile robots have become widely utilized in factories, shopping malls, and homes to perform various service tasks due to their ability to navigate independently in indoor environments. A key component of this autonomous navigation capability is accurate localization, which enables the robot to determine its position and provides essential input for planning and control processes. Localization is particularly critical among the various capabilities required for effective robot operation. Inaccurate or unreliable localization can lead to navigation failures or even collisions, underscoring its importance in ensuring safe and efficient robot performance.

Global localization is a fundamental problem in mobile robotics that involves determining a robot’s position and orientation within a known environment without prior knowledge of its initial location. This challenge is critical for autonomous navigation, especially in indoor environments where global positioning system (GPS) signals are often unavailable [Reference Alarifi, Alsaleh, Alnafessah, Al-Hadhrami, Al-Ammar, Al-Khalifa and Hend1]. Successful global localization enables a robot to navigate, map, and interact with its surroundings autonomously. It is essential for various applications, from service robots in homes and offices to automated guided vehicles in warehouses. Figure 1 shows how global localization is intricately connected to mobile robots’ navigation, guidance, and control, forming a fundamental aspect of their autonomous operation. Global localization gives the robot an accurate understanding of its position within a global coordinate system, essential for effective navigation and precise waypoint following. It ensures accurate guidance by continuously updating the robot’s position, maintaining the desired trajectory, and avoiding deviations. Additionally, it supplies crucial feedback for control systems, enabling precise adjustments to the robot’s movements based on its current state.

Figure 1. Overview of an autonomous mobile robot system.

The paper broadly classifies the overview of existing methods for global localization into probabilistic-based, learning-based, Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM)-based, and optimization-based approaches.

(i) Probabilistic-based approaches: Bayesian filters, like the extended Kalman filter (EKF) and the particle filter, fall under this category. They use probabilistic models to estimate the robot’s global pose by incorporating sensor measurements and motion models. (ii) Learning-based approaches: Learning-based approaches aim to capture complex relationships between sensor inputs and global poses, reducing reliance on explicit models. (iii) SLAM-based approaches: SLAM methods involve building a map of the environment while simultaneously localizing the robot within the map. SLAM methods can be broadly classified based on the primary sensors they use into three categories: Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR)-based SLAM, Vision-based SLAM (VSLAM), and Hybrid SLAM. Each of these methods leverages different types of sensor data to build maps and localize the robot within an environment. (iv) Optimization-based approaches: Optimization-based approaches for mobile robot localization focus on formulating the localization problem as an optimization problem. The objective is to find the robot’s pose (position and orientation) that minimizes (or maximizes) a certain cost (or reward) function.

Indoor environments often pose unique challenges for global localization, particularly when they are symmetrical or lack distinctive features. These symmetrical environments, as shown in Figure 2, can adversely affect the global localization of mobile robots due to the challenge of observing a large quantity of similar structures with few distinct features in these settings [Reference Amarasinghe, Mann and Gosine2, Reference Beinhofer and Burgard3]. These scenarios intensify the problem of global localization, requiring more sophisticated algorithms to determine the robot’s position reliably. Current solutions depend on approaches such as artificial landmarks [Reference Amarasinghe, Mann and Gosine2], QR codes [Reference Nazemzadeh, Macii and Palopoli4], etc. Furthermore, achieving global localization usually requires more than just a few sensor scans to succeed [Reference Amarasinghe, Mann and Gosine5, Reference Wu, Peng, Tang and Wang6], especially in the case of symmetric environments.

Figure 2. Symmetrical scenarios: (a) office environment, (b) tunnel, (c) industrial warehouse, and (d) long corridors.

Despite significant advancements, several gaps and challenges remain in the field of global localization:

-

• Ambiguity in symmetrical environments: Numerous existing methods [Reference Amarasinghe, Mann and Gosine5–Reference Zeng, Guo, Xu and Zhu10] struggles with accurately localizing the robot in environments with repetitive patterns or symmetrical structures. In these environments, the robot may encounter difficulties distinguishing one location from another due to the repetitive nature of the surroundings. For instance, if a corridor looks identical from one end to the other, the robot’s sensors may provide similar readings in multiple locations, leading to ambiguity about its exact position.

-

• Featureless regions: Regions with few or no distinctive features can lead to poor localization performance due to the lack of reference points.

Examples include empty hallways, large open spaces, or plain walls. In these regions, sensors like cameras or LiDAR may struggle to find enough data points or features to determine the robot’s position accurately. Without adequate reference points, the robot may have trouble accurately understanding its location, leading to potential errors in navigation.

-

• Sensor noise and inaccuracies: Sensor data is often noisy and may lead to incorrect localization, especially in dynamic or cluttered environments.

For instance, a LiDAR sensor might pick up reflections from shiny surfaces or moving objects, leading to false readings. Similarly, cameras can be affected by varying lighting conditions, and inertial measurement units (IMUs) can drift over time.

-

• Computational complexity: The high computational demands of some localization methods limit their real-time applicability on resource-constrained robots.

Global localization algorithms often require complex computations to process sensor data, map the environment, and estimate the robot’s position. The algorithms, such as particle filters, graph-based optimization, or deep learning models, are computationally intensive. Over high computational load can cause delays, reducing the robot’s ability to respond effectively to its environment.

-

• Adaptability: Many algorithms are environment-specific and struggle to generalize across different indoor settings.

Researchers design existing localization algorithms with specific environments in mind. They rely on particular features, sensor configurations, or assumptions about the environment that do not generalize well to different settings. For example, an algorithm optimized for a well-lit office environment might perform poorly in a dimly lit warehouse.

Therefore, this review paper aims to address these gaps and challenges by

-

1. Analyzing state-of-the-art methods in global localization: Providing a comprehensive overview of current global localization techniques like adaptive Monte Carlo localization (AMCL), Hector SLAM, cartographer, and hybrid SLAM, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses in symmetrical environments. The importance of this analysis lies in understanding how these techniques perform under specific conditions of symmetry and what limitations they may have. By critically evaluating these methods, the review highlights which approaches are most effective and where improvements are needed.

-

2. Addressing critical challenges in global localization imposed by symmetrical environment: Discussing the challenges posed by symmetrical indoor environments, such as symmetrical features and a lack of distinct landmarks, which can complicate localization tasks. Understanding these critical challenges is crucial for improving the robustness and reliability of localization systems. Pinpointing where the current methods fall short and exploring possible solutions aims to provide insights into how to address these challenges effectively.

-

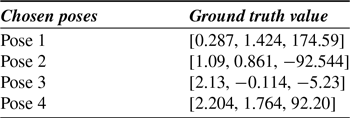

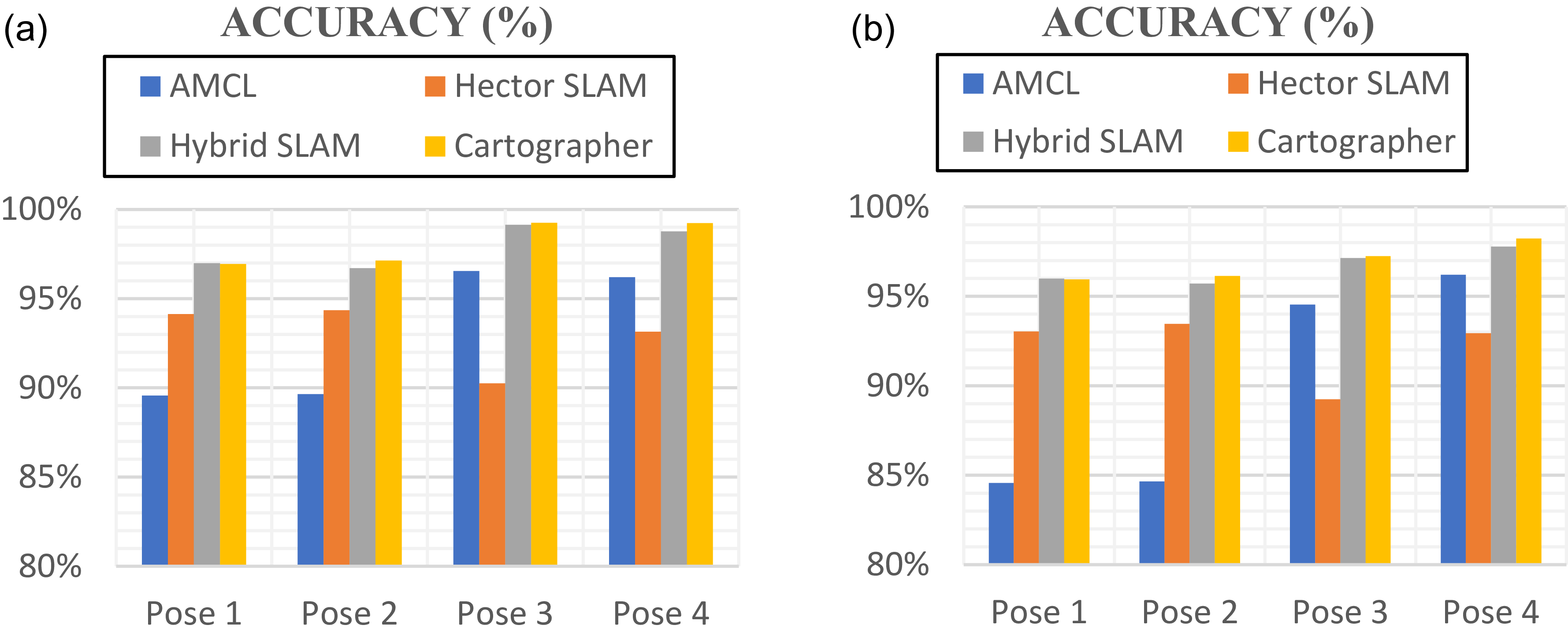

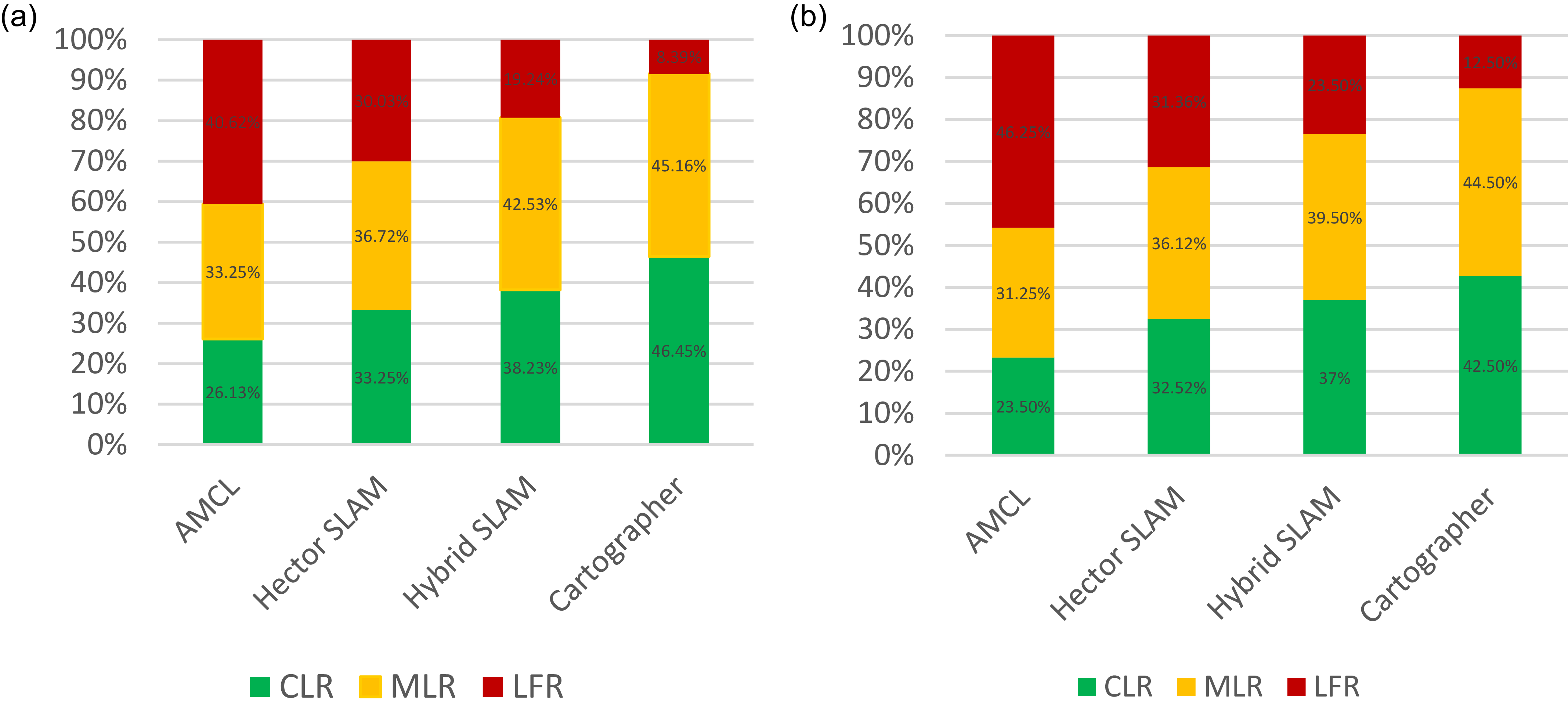

3. Benchmarking performance: Establishing a benchmark scenario by constructing a symmetrical environment to evaluate localization algorithms and presenting a comparative analysis based on these benchmark scenarios. Comparative analysis based on this benchmark scenario clearly shows how different methods perform in controlled conditions. The rationale behind benchmarking is to provide a standardized framework for assessing algorithm performance, which helps identify best practices and improvement areas.

This paper offers several significant contributions to global localization in symmetrical environments. First, it presents a comprehensive review and critical analysis of prominent localization techniques including AMCL, Hector SLAM, Cartographer, and hybrid SLAM highlighting their advantages and limitations when applied in highly symmetrical settings. Second, it systematically identifies the core challenges posed by symmetrical environments, such as the scarcity of distinctive landmarks and the presence of repetitive structural features, and provides informed insights into potential strategies for improving localization robustness under such conditions. Third, the paper introduces a benchmarking framework that involves the design of a controlled, standardized symmetrical environment, enabling consistent evaluation and comparison of localization algorithms. This framework facilitates the identification of best-performing methods and highlights areas requiring further improvement. Collectively, these contributions aim to deepen the understanding of localization in geometrically ambiguous spaces and support the development of more resilient and accurate systems.

While review papers [Reference Abdelgawad11–Reference Eman and Ramdane13] explore localization in robotics, they primarily emphasize theoretical frameworks and general algorithmic categories. They often overlook the practical and critical challenges posed by global localization in symmetrical environments, where repetitive spatial structures introduce pose ambiguity, aliasing, and belief collapse issues that can drastically degrade localization accuracy. Furthermore, existing surveys rarely systematically examine how different algorithms cope with environmental symmetry in real-world scenarios. They also lack benchmark-driven evaluations that explore the computational burden and robustness of these methods under controlled, variable-symmetry conditions. This paper addresses these limitations by narrowing its focus to the global localization problem under symmetry-induced uncertainty. It reviews state-of-the-art techniques including probabilistic-based, learning-based, SLAM-based, and optimization-based approaches. To ground the discussion, the paper introduces two experimental test cases (low and high symmetry) that help reveal practical performance boundaries. These gaps and limitations form the core motivation of this review to provide a practically guided and symmetry-aware perspective that advances the understanding and application of global localization techniques in complex indoor environments.

This review paper begins by categorizing the fundamental challenges of global localization for indoor mobile robots into probabilistic, learning-based, SLAM-based, and optimization-based approaches based on their underlying methodologies and techniques to estimate a robot’s position within an environment. Figure 3 shows a general classification of such methods:

Figure 3. Classification of indoor global localization approaches.

Section 2 presents a detailed examination of the four primary categories for global localization. The discussion thoroughly explores each category, highlighting the specific methodologies and their respective applications in estimating a robot’s position within an environment. This comprehensive analysis aims to elucidate each approach’s distinct characteristics and advantages, offering a nuanced understanding of their roles in advancing localization accuracy and efficiency.

Section 3 delves into the critical issue of global localization when encountering a symmetrical indoor space, a significant challenge in robotics due to these environments’ inherent ambiguities. It also evaluates existing solutions, including integrating visual features with traditional LiDAR-based methods and combining vision sensors with probabilistic localization techniques, to enhance localization accuracy in these environments.

In Section 4, this paper presents a comparative analysis of four algorithms (AMCL, Hector SLAM, hybrid SLAM, and Cartographer) operating in low- and high-symmetry scenarios. It provides corresponding experimental findings and insights. Section 5 presents a comprehensive discussion of our findings, interpreting the results within the context of existing literature and analyzing their implications for the field. Section 6 gives conclusions, emphasizing current challenges and outlining potential directions for future research endeavors.

2. Review of global indoor localization of mobile robots

2.1. Localization principle

The mobile robot utilizes odometry to track its movement while traversing in a familiar environment. However, the inherent uncertainty in odometry measurements can lead to confusion regarding the robot’s precise position. The robot employs localization techniques to mitigate this uncertainty and accurately understand its location relative to the environment. The robot collects observations about its surroundings by incorporating information from its external sensors, including laser, vision, and ultrasonic sensors. These sensory inputs offer valuable data for a more robust understanding of the environment and the robot’s position. The robot enhances its localization capabilities by integrating these sensory observations with the data obtained from odometry. This fusion of information allows the robot to refine its estimate of its current position, effectively reducing the potential for position uncertainty to escalate uncontrollably.

In summary, by leveraging odometry data and information gathered from its exteroceptive sensors, the mobile robot can localize itself within its environment, thereby mitigating the effects of odometry uncertainty and maintaining a reliable understanding of its position.

2.2. Localization approaches

Global localization for mobile robots is classified into four approaches based on underlying methods and techniques used to determine the robot’s location: probabilistic-based, learning-based, SLAM-based, and optimization-based approaches.

2.2.1. Probabilistic-based approaches

Probabilistic approaches in robotics employ probability theory to manage uncertainties inherent in sensor data and robot motion. Two prominent methods within this framework are Kalman filters and particle filters.

Kalman filters: These are optimal estimators for linear systems with Gaussian noise. They maintain a belief about the robot’s state as a Gaussian distribution, updating this belief through a prediction–correction cycle.

Particle filters (Monte Carlo Localization – MCL): These are nonparametric approaches suitable for nonlinear and non-Gaussian systems. They represent the robot’s belief as a set of weighted samples (particles), each hypothesizing a possible state.

Kalman filter

Kalman filter [Reference Abdelgawad11] is widely used for localizing mobile robots because it estimates the state of a dynamic system from a series of noisy measurements. It is one of the most commonly used methods for sensor fusion in mobile robotics applications [Reference Park and Lee12]. This filter frequently combines data from sensors to create a statistically optimal estimate. If a system describes a linear model and models the uncertainties of the sensors and the system as white Gaussian noise, the Kalman filter provides an optimal statistical estimate for the observed data.

Figure 4 represents the schematic diagram of applying the Kalman filter to localize the mobile robot. The algorithm works by a two-phase process with prediction and update phases. (i) In the prediction step, the Kalman filter predicts the current state of the robot based on the mathematical model of its motion (e.g., how it should move given the control input like velocity or steering angle) and the previous state estimate. The filter also predicts the uncertainty associated with its state estimate, which grows over time due to uncertainties in the model and the control inputs. (ii) In the update step, the Kalman filter updates its state estimate once it gets new sensor data. It compares the predicted state to the actual sensor measurements and uses this “innovation” to correct the state estimate. The filter then reduces the uncertainty in the state estimate based on how reliable the sensor data is. Thus, Kalman filter-based localization efficiently and accurately addresses the challenge of tracking a robot’s position. This optimal sensor fusion method is particularly effective when monitoring the robot’s movement from an initially known location. Typically employed in continuous world representation, this localization method encounters limitations when the robot’s uncertainty becomes substantial, such as when the robot’s initial pose is unknown. In such cases, the localization approach fails to capture potential robot positions accurately and irreversibly loses track.

Figure 4. Schematic diagram of Kalman filter-based mobile robot localization.

In the realm of Kalman filter theory, the assumption is that the system is linear and characterized by Gaussian noise. Nevertheless, numerous robotic systems exhibit nonlinear characteristics. This necessity has led to the development of an alternative localization method called the EKF. The EKF is an extension of the Kalman filter tailored for nonlinear systems. In the EKF, the initial step involves linearizing the system and applying the Kalman filter. In [Reference Eman and Ramdane13], the localization of a mobile robot using EKF was presented, which used a nonlinear model to predict the coordinates of a wheeled mobile robot. To improve the localization performance and to reduce accumulated errors while using dead reckoning, a method that uses EKF with an infrared sensor was proposed [Reference Mohammed Faisal, Hedjar, Mathkour, Zuair, Altaheri, Zakariah, Bencherif and Mekhtiche14]. Studies reported in ref. [Reference Lee, Kim and Lee15] and [Reference Brossard and Bonnabel16] employed various sensors like sonar, IMU, and encoders along with EKF for the localization of a mobile robot. Despite the performance improvements in these methods, EKF faced limitations when applied to mobile robot localization, particularly due to its reliance on linearizing nonlinear systems [Reference Xu, Yan and Ji17], which led to significant errors. EKF’s performance was affected by inaccurate covariance propagation and the complexity of computing Jacobians, which were often error-prone [Reference Muhammad Latif Anjum, Hwang, Kwon, Kim, Lee, Kim and Cho18]. Additionally, it assumes Gaussian noise, which may not hold in real-world scenarios.

In ref. [Reference Ullah, Shen, Su, Esposito and Choi19], the authors addressed the above issues with EKF and introduced the Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF), which used the unscented transform to propagate sigma points through the nonlinear system without linearization. UKF resulted in higher accuracy, better handling of nonlinearities, and robustness to non-Gaussian noise, making UKF more suitable for complex mobile robot localization tasks. UKF overcomes EKF linearization errors using a deterministic sampling approach, representing the state distribution as a set of sample points, and achieves better accuracy [Reference Yang, Shi and Chen20]. The study based on real data shows that the performances of the EKF and UKF are nearly identical to those in ref. [Reference D’Alfonso, Lucia, Muraca and Pugliese21]. In the Kalman filter approach, the system requires knowledge of the robot’s initial position with some approximations. As a result, it does not solve the global localization problem. Also, Kalman filters represent uncertainty as a single Gaussian distribution, which is limited when the robot’s belief about its position could have multiple possible solutions (e.g., in environments with symmetry or ambiguity).

Figure 5. Monte Carlo localization for mobile robot localization [Reference Sebastian Thrun and Fox22].

Particle filter

EKF estimation assumes that noise from sensors and the environment follows a Gaussian probability density function. In practice, this assumption may not always hold. Additionally, some sensors have strongly nonlinear measurement models, which leads to increased estimation errors when linearizing the nonlinear equations. When these assumptions are not suitable, the particle filter is a more appropriate algorithm for global localization of mobile robots. It processes raw sensor data directly, eliminating the need to extract features from sensor values. Unlike the EKF, which is bound to a unimodal distribution, particle filters are nonparametric and do not rely on a Gaussian density assumption. The particle filter algorithm also uses increasingly sophisticated methods to represent uncertainty, surpassing the limitations of the standard Kalman filter. We now turn our attention to a popular localization algorithm that describes the belief bel(x t ) by particles. The algorithm is called MCL. The MCL has emerged as one of the most widely adopted localization algorithms in robotics due to its popularity and effectiveness. Its straightforward implementation and versatility make it suitable for addressing various robot localization challenges with generally favorable outcomes.

Figure 5(a–e) illustrates MCL using the one-dimensional hallway example [Reference Sebastian Thrun and Fox22]. Initially, the robot does not know exactly where it is. Therefore, it randomly guesses by placing several possible positions (represented as particles) all over the map. As the robot senses its surroundings, it can refine its position estimate by continuously updating and resampling particles based on sensor data and movement. As the robot gathers more information, it increasingly focuses on the most likely locations, improving its accuracy of localization. This process ensures that the robot’s position estimate converges towards the proper location over time.

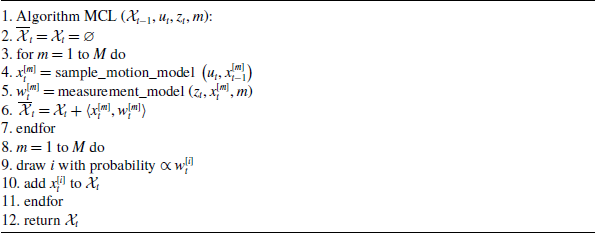

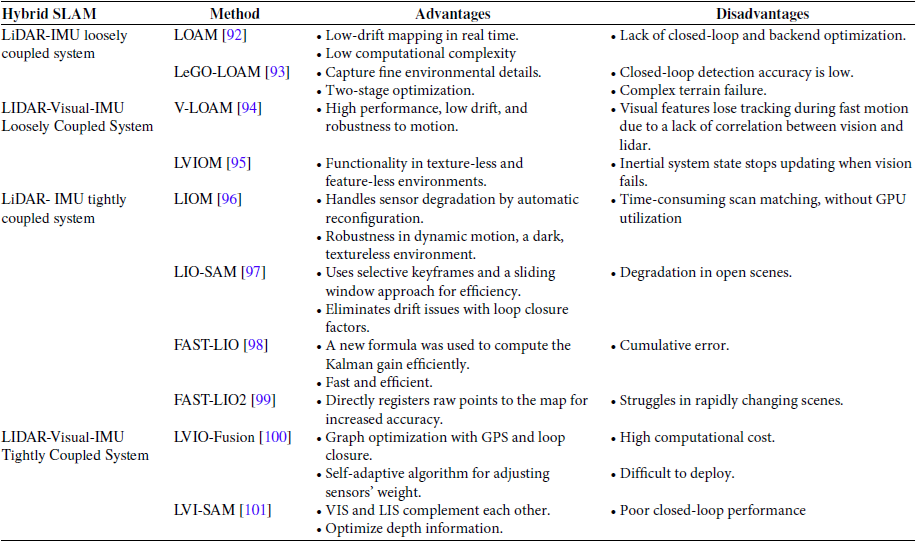

Table I shows the MCL algorithm based on particle filter, obtained by substituting the appropriate probabilistic motion and perceptual models into the particle filter algorithm shown in Table II. The basic MCL algorithm represents the belief

![]() $\mathrm{bel} (x_{t})$

by a set of

$\mathrm{bel} (x_{t})$

by a set of

![]() $M$

particles:

$M$

particles:

Line 4 in the algorithm (Table I) samples from the motion model, using particles from the present belief as starting points. The measurement model is then applied in line 5 to determine the important weight of that particle. The initial belief

![]() $\mathrm{bel} (x_{0})$

is obtained by randomly generating

$\mathrm{bel} (x_{0})$

is obtained by randomly generating

![]() $M$

such particles from the prior distribution

$M$

such particles from the prior distribution

![]() $p(x_{0})$

and assigning the uniform importance factor

$p(x_{0})$

and assigning the uniform importance factor

![]() $M^{-1}$

to each particle. The function’s motion model predicts the next state of particles based on robot dynamics, while the measurement model updates the particle weights by predicted sensor observation with actual sensor data.

$M^{-1}$

to each particle. The function’s motion model predicts the next state of particles based on robot dynamics, while the measurement model updates the particle weights by predicted sensor observation with actual sensor data.

Table I. Monte Carlo localization (MCL) algorithm based on particle filters.

Table II. The particle filter algorithm.

In early works, the MCL algorithm relies on particle filter and uses a large number of weighted particles from the proposed distribution of robot pose and then updates them based on the measurement of sensors. The MCL algorithm always converges to the global optimum, but in large-scale scenes, it may take a lot of particles and a long time to converge [Reference Kucner, Magnusson and Lilienthal23]. To make sampling more efficient, many researchers have improved the MCL algorithm. For instance, the mixture algorithm combines the MCL algorithm with the dual MCL, using the probabilistic mixing ratio. Sometimes, it reduces the error by more than an order of magnitude compared to the original MCL. Self-adaptive Monte Carlo localization (SAMCL) distributes global samples in a similar energy region instead of distributing them randomly on the map, which results in better localization performance [Reference Zhang, Zapata and Lepinay24]. However, they depend on the specific environment, which makes them unreliable, and they are still unable to solve the slow convergence problem in large-scale environments. The MCL method is still the gold standard for robot localization and often uses LiDARs [Reference Du, Chen, Lou and Wu25–Reference Julius Fusic and Sitharthan27], cameras [Reference Hao, Chengju and Qijun28], or Wi-Fi [Reference Olivera, Plaza and Serrano29]. Such MCL methods often use a 2D LiDAR sensor and an occupancy grid map to estimate the robot’s pose, and they are quite robust.

2.2.2. Learning-based approaches

This paper section focuses on learning-based methods for achieving global localization for indoor mobile robots. These methods leverage machine learning algorithms to interpret sensor data and predict the robot’s location. The system can recognize patterns and improve localization accuracy over time by training on large datasets. Learning-based approaches for global localization can be classified into three main categories: supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning (RL) based on the learning process involved.

Supervised learning approaches involve training a model on a labeled dataset, where the input data (e.g., LiDAR scans) are paired with the corresponding output labels (e.g., specific locations or poses). The model learns to map inputs to outputs based on the provided labels.

Unsupervised learning approaches do not rely on labeled data. Instead, they aim to find patterns or structures in the input data without explicit output labels.

RL involves training an agent to make a sequence of decisions by rewarding it for good actions and penalizing it for bad ones. In the context of localization, RL can be used to optimize the robot’s navigation and localization strategies based on its interactions with the environment.

Researchers have recently achieved global localization of mobile robots by incorporating environmental information about the robot’s location, which can be accomplished through semantic place classification. It involves assigning semantic labels or categories to different locations or areas within an environment based on their characteristics or attributes. This classification provides contextual information about the environment, which can be valuable for place recognition. By associating semantic labels with specific places, the robot can better understand the environment and distinguish between locations based on their semantic meaning rather than just raw sensor data. This approach enhances the reliability and accuracy of place recognition, particularly in complex indoor environments where traditional methods may struggle due to similarities in sensor data. Presented in ref. [Reference Alqobali, Alshmrani, Alnasser, Rashidi, Alhmiedat and Alia30], the semantic model of the indoor environment provides the robot with a representation closer to human perception, thereby enhancing the navigation task. Also, incorporating semantic information into the map improves the accuracy of robot navigation, as in ref. [Reference Alqobali, Alnasser, Rashidi, Alshmrani and Alhmiedat31]. The semantic model of the indoor environment provides the robot with a representation closer to human perception, thereby enhancing the navigation task.

“Semantic place labelling” or “semantic place classification” can be performed by making use of data acquired from its sensors [Reference Mozos32]. Classification methods based on visual data captured with a 2D camera [Reference Fazl-Ersi and Tsotsos33] or fused data [Reference Rottmann, Mozos, Stachniss and Burgard34], including the visual and range data acquired from a 2D laser range finder, have been studied previously. In these studies, researchers generally extracted features such as Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) [Reference Burger and Burge35] and Speeded Up Robust Features (SURF) [Reference Bay, Ess, Tuytelaars and Van Gool36] from images or calculated hand-crafted features from laser range data. They then processed these features to classify a robot location. The main drawback of the studies using visual data is the performance dependency on illumination variations corresponding to different lighting conditions.

The paper categorizes the related work on semantic place classification into supervised and unsupervised learning methods based on how the semantic information is learned. This semantic information might sometimes be uncertain, especially in environments with symmetrical or repetitive structures. In such cases, RL-based algorithms can incorporate uncertainty into their decision-making processes, allowing robots to weigh different possibilities and choose actions that reduce ambiguity. Also, RL can learn robust policies for localization in the presence of sensor error, noise, or unexpected environmental changes. Based on this, learning-based approaches are classified into supervised, unsupervised, and RL.

Supervised learning

In recent years, the application of supervised machine learning techniques has significantly advanced the field of robotic place recognition and semantic mapping to improve global localization. Researchers have developed various models and algorithms to enhance a robot’s ability to understand the environment and navigate complex environments.

For instance, a bubble space model presented in ref. [Reference E. and Bozma37] for place representation contained two new variables: varying robot pose and multiple features. These variables were transformed into bubble descriptors and classified by a multi-class support vector machine (SVM) classifier to learn specific places. A Voronoi Random Field (VRF) algorithm [Reference Shi, Kodagoda and Dissanayake38] was proposed, based on Conditional Random Field, and an SVM classifier was used to achieve semantic labeling of Generalized Voronoi Graphs nodes. A low-level image descriptor for addressing the room classification problem was proposed by refs. [Reference Ursic, Kristan, Skocaj and Leonardis39] and [Reference Yeh and Darrell40] using an SVM classifier. A semantic map construction method, which combined place and object recognition using supervised learning, was presented in ref. [Reference Kostavelis and Gasteratos41]. High-dimensional histograms were used to represent an observed scene and achieved the classification of visual places through SVM [Reference Pronobis and Jensfelt42]. Performance was evaluated using the Freiburg University, Buildings 79 and 52 dataset [Reference Kaleci, Turgut and Dutagaci43].

Unsupervised learning

In global localization, supervised learning approaches rely on labeled datasets, requiring human intervention to annotate data for training. In contrast, unsupervised learning methods offer several advantages. They eliminate the dependency on labeled data, allowing models to discover new patterns and relationships in raw, unlabeled data. Unsupervised models can autonomously extract features and find patterns in the data, enabling the robot to learn, classify the places, and adapt to new environments without explicit human intervention. Additionally, these methods can incrementally learn and organize environmental data, allowing robots to update their understanding of surroundings in real time.

Recent advancements in semantic place classification using unsupervised learning have significantly improved global localization by leveraging various sensor modalities and machine learning techniques. Traditional approaches utilized visual cues from video and image streams to detect and categorize “unknown” place labels [Reference Ranganathan44]. Additionally, a Gaussian mixture model was used to form a probability distribution of features extracted by image-preprocessing, while a place detector grouped features into places using odometry data and a hidden Markov model [Reference Chella, Macaluso and Riano45]. The unsupervised method proposed in ref. [Reference Erkent, Hakan and Bozma46], based on the Single-Linkage (SLINK) agglomerative algorithm [Reference Sibson47] and an incremental approach, allows the robot to learn about organizing the observed environment and localizing within it. Finally, the authors in ref. [Reference Guillaume, Dubois, Frenoux and Philippe48] used CENsus TRansform hISTogram (CENTRIST) and GIST descriptors, applying an unsupervised approach with a Self-Organizing Map for classification.

Incorporating semantic place recognition to enhance global localization using unsupervised learning was applied to various sensors, including 2D and 3D LiDARs, red, green, blue (RGB), and red, green, blue-depth (RGB-D) cameras. In ref. [Reference Rottmann, Mozos, Stachniss and Burgard49], AdaBoost features from 2D LiDAR scans were used to infer semantic labels such as office, corridor, and kitchen. They combined the semantic information with an occupancy grid map in an MCL framework. This method required a detailed map and a manually assigned semantic label to every grid cell. According to ref. [Reference Sünderhauf, Dayoub, McMahon, Talbot, Schulz, Corke, Wyeth, Upcroft and Milford50], researchers constructed semantic maps from cameras by assigning a place category to each occupancy grid cell. They used the Places205 ConvNet to recognize places and relied on a LiDAR-based SLAM for building the occupancy grid map. In ref. [Reference Hendrikx, E.Torta, Bruyninckx and van de Molengraft51], available building information models (BIMs) were used to extract and localize geometric and semantic information by matching 2D LiDAR-based features corresponding to walls, corners, and columns. While the automatic extraction of semantic and geometric maps from a BIM was promising, it was not suitable for global localization due to its inability to overcome the challenges of a repetitively structured environment.

Recent works in extracting semantic information with deep learning models showed significant improvement in the performance of mobile robot localization using text spotting. Using textual cues for localization was surprisingly uncommon, with notable works presented in refs. [Reference Cui, chunyan, Huang, Rosendo and Kneip52] and [Reference Zimmerman, Wiesmann, Guadagnino, Läbe, Behley and Stachniss53]. The study in ref. [Reference Cui, chunyan, Huang, Rosendo and Kneip52] presented a novel underground parking localization method using text recognition, employing optical character recognition (OCR) to detect parking slot numbers and combining OCR with a particle filter for localization. In ref. [Reference Zimmerman, Wiesmann, Guadagnino, Läbe, Behley and Stachniss53], an indoor localization system for dynamic environments was presented, using text spotting integrated into an MCL framework, which operated on 2D LiDAR scans and camera data.

Reinforcement learning

Building upon exploring supervised and unsupervised learning approaches in global localization, RL emerges as a pivotal technique in enabling mobile robots to navigate and understand complex environments autonomously. Unlike traditional methods, RL allows an agent to learn optimal behaviors through trial-and-error interactions within its environment, receiving feedback as rewards or penalties [Reference Khelifi and Moussaoui54]. The key idea of RL is to determine the mapping between actions and states to maximize a numerical reward signal. The learner agent interacts with the environment and receives rewards or penalties for the performed actions. Therefore, RL uses rewards and punishments as signals for positive and negative behaviors to optimize agent behavior continuously.

Recent studies have demonstrated the efficacy of RL in addressing challenges associated with continuous state and action spaces noise in reward functions, as well as the integration of particle filters for improved state estimation. In ref. [Reference Sibson47], a novel framework that utilizes a particle filter for learning in real-world situations was presented. This approach dealt with the challenge of expressing continuous states and actions by dividing the continuous state and action space, allowing a more efficient search for solutions with fewer memories and parameters. The study in ref. [Reference Dogru and B.55] addressed deep RL agent performance degradation due to noise in reward functions and proposed a novel filter to mitigate its effect. The proposed algorithm combined optimal filtering and RL concepts to improve the RL policy in the presence of skewed probabilistic distributions in reward functions. The method in [Reference Yoshimura, Maruta, Fujimoto, Sato and Kobayashi56] combined the ideas of particle filters, which are used for state estimation in nonlinear and non-Gaussian systems, with RL. This approach assigned randomness in the system and measurement models to the RL policy, allowing for optimization of various objective functions, such as estimation accuracy, particle variance, likelihood of parameters, and regularization term. This interpretation enabled the particle filter design process to benefit from the RL’s learning capabilities, improving the particle filter’s overall performance and accuracy in estimating a system’s state. These advancements underscore the potential of RL to significantly enhance the performance and robustness of global localization systems for indoor mobile robots.

Recently, deep learning models showed notable advancements in global localization. PoseNet [Reference Kendall and Cipolla57], based on GoogLeNet, was the first work to utilize deep learning for this purpose, demonstrating the effectiveness of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for complex regression tasks. Bayesian PoseNet [Reference Kendall and Cipolla58] extended this approach by leveraging uncertainty measures for estimating re-localization error and scene detection. LSTMNet [Reference Walch, Hazirbas, Leal-Taixé, Sattler, Hilsenbeck and Cremers59] uses LSTM units to reduce the dimensionality of CNN outputs, while Vidloc [Reference Clark, Markham, Trigoni and Wen60] employs video clips as input to improve pose estimation accuracy. HourglassNet [Reference Melekhov, Kannala and Rahtu61] introduced an encoder–decoder CNN architecture with up-convolution layers to preserve fine-grained information. Branch Net [Reference Wu, Ma and Hu62] was a multi-task CNN addressing the coupling of orientation and translation. PoseNet2 [Reference Kendall63] introduced a novel loss function for optimal learning of position and orientation, although its localization precision might decrease with scene scale.

A new approach recently emerged where deep learning was employed for robot localization. In refs. [Reference Jo and Kim64] and [Reference Xu, Chou and Dong65], deep CNNs were utilized for camera pose regression and initializing particles in MCL. In refs. [Reference Yu, Yan, Zhuang, Gu, Xu, Chou and Dong66], a collection of 2D laser data was converted into an RGB image and an occupancy grid map, which were combined into a multi-channel image. A neural network architecture was employed to predict the 3-DOF robot pose, with experiments conducted on an actual mobile robot to validate the efficacy of this approach. The methodology in ref. [Reference Wang, Gao, Zhao, Yin and Wang67] uses a deep hierarchical framework for robot global localization, involving two main components: coarse localization and fine localization. Coarse localization used RGB images and a CNN-LSTM network, while fine localization combines fast branch-and-bound scan matching (FBBS) and MCL using LiDAR point cloud data. The framework achieved faster convergence and more accurate estimation compared to other methods. Deep learning-based object detection has gained the attention of researchers for robot semantic navigation. In ref. [Reference Alotaibi, Alatawi, Binnouh, Duwayriat, Alhmiedat and Alia68], a real-time semantic map production system for indoor robot navigation was proposed, utilizing LiDAR and vision-based systems, achieving 78.86% average map construction accuracy.

2.2.3. SLAM-based approaches

Over the past decades, significant progress has been made in advancing autonomous navigation for mobile robots. The development of SLAM technology is crucial in enhancing robots’ ability to localize themselves and construct detailed maps of their surroundings without prior knowledge of the environment. SLAM technology is the foundation for autonomous decision-making, planning, and control of robots, enabling them to explore unknown environments effectively.

This paper categorizes SLAM approaches based on the sensors employed during the localization process, focusing on three primary categories: LiDAR-SLAM, visual SLAM, and Hybrid SLAM.

LiDAR-SLAM: This approach utilizes LiDAR sensors to generate precise representations of the environment. It is particularly effective in scenarios where accurate distance measurements are crucial, such as autonomous driving and robotics operating in complex terrains.

Visual SLAM: Leveraging cameras, visual SLAM systems capture images to interpret and map surroundings. These systems are advantageous due to their cost-effectiveness and the rich contextual information they provide. However, its performance can be affected by lighting conditions and textured environments.

Hybrid SLAM: To harness the strengths of multiple sensors, Hybrid SLAM integrates data from various sources, such as LiDAR, cameras, and IMUs. This fusion enhances robustness and accuracy, compensating for the limitations inherent in individual sensor modalities. For instance, combining LiDAR’s precise distance measurements with the rich visual context from cameras can improve performance in diverse environmental conditions.

The subsequent sections provide an in-depth review of studies within each of these categories, analyzing their methodologies, applications, and contributions to the advancement of SLAM technologies.

LIDAR-based SLAM

LiDAR-SLAM uses LiDAR sensor data as the primary source of information, enabling it to achieve localization and mapping under diverse environmental conditions. Object information from LiDAR presents a series of scattered points with accurate angular and distance information, known as a point cloud. Generally, LiDAR-SLAM extracts and matches the features of two consecutive point cloud graphs taken at different times, calculates the relative motion, distance, and pose changes through LiDAR odometry, and completes the robot’s self-positioning.

The significant advantage of the LiDAR sensor is its relatively accurate range measurement, simple error model, stable operation in environments without direct glare from intense light, and relatively easy point cloud processing. LiDAR-SLAM is categorized into two types based on the LiDAR sensor: 2D LiDAR-SLAM and 3D LiDAR-SLAM. 2D LiDAR-SLAM is lower in cost and suitable for simple indoor environments. At the same time, 3D LiDAR-SLAM, though more expensive, is ideal for outdoor surveying and mapping and handles larger amounts of information.

A complete 2D LiDAR-SLAM involves a front-end incremental estimation part and a back-end mapping part. The front-end consists of two components: obtaining sensor data and scan matching. The back-end’s main task is to solve a nonlinear optimization problem. The first mainstream approach for the back-end is based on filtering, like the Bayesian estimation process. A representative algorithm was Gmapping [Reference Kok, Solin and Schon69], which only estimated the robot’s position at the current moment, resulting in low computational requirements. However, this method had the disadvantage that errors generated at a previous moment could not be corrected, potentially leading to suboptimal mapping, especially in large environments. The second method was primarily based on nonlinear optimization, with graph optimization widely used in LiDAR-SLAM. In graph-based SLAM, the robot’s pose was represented as a node or vertex, and the relationships between poses formed the edges. Errors accumulated during map building were optimized using the nonlinear least squares method to produce the final map. A typical algorithm employing this method was Cartographer [Reference Hess, Kohler, Rapp and Andor70]. Fast SLAM [Reference Shiguang and Chengdong71], introduced in 2002, was the first system capable of generating real-time, faster maps, but it suffered from high memory usage and significant particle dissipation issues. The Optimal RBPF [Reference Konolige, Grisetti, Kümmerle, Burgard, Limketkai and Vincent72] method was proposed to address these shortcomings, which optimized the Gmapping algorithm to mitigate particle degradation problems. Karto-SLAM [Reference Konolige, Grisetti, Kümmerle, Burgard, Limketkai and Vincent72], an early system, introduced the concept of sparsity in graph-based optimization, laying the groundwork for Cartographer. Cartographer improved accuracy and robustness by leveraging graph optimization techniques while reducing computational requirements, displacing several early filter-based methods.

Over the past several decades, 2D SLAM has been well developed. Still, certain challenging environments, such as fog, smoke, and dust, significantly impact 2D LiDAR SLAM as they cause the laser beams to scatter and reduce the accuracy of scans. With the introduction of Lidar Odometry and Mapping (LOAM), 3D SLAM addressed the influence of many environmental factors. 3D SLAM typically uses 3D LiDAR and odometer data as input data, and 3D point cloud maps, robot trajectory, or pose graph as output. Section 2.2.3(C) will summarize work related to the hybrid SLAM based on 3D LiDAR.

Vision-based SLAM

VSLAM [Reference Cadena, Carlone, Carrillo, Latif, Scaramuzza, Neira, Reid and Leonard73] is a technique that enables a robot to build a map of its environment while simultaneously keeping track of its location within that environment, using visual information from one or more cameras. Unlike LiDAR-based SLAM, which relies on laser sensors, VSLAM primarily uses cameras to capture images of the surroundings. VSLAM can be divided into feature-based and direct-based methods, each differing in processing and utilizing visual data to estimate the camera’s pose and build a map of the environment.

Feature-based VSLAM methods: These methods detect and extract distinct features, such as corners, edges, or blobs, from images. Once extracted features are matched across consecutive frames to estimate the camera’s motion and incrementally build a map of the environment. Feature-based methods are known for their robustness in environments with rich textures and are less sensitive to changes in lighting conditions. However, they may struggle in scenarios with low-texture regions or repetitive patterns, where distinct features are scarce or ambiguous.

Direct-based VSLAM methods: In contrast, direct methods utilize the intensity values of all pixels in the image without prior feature extraction. They aim to minimize the photometric error between consecutive frames by directly aligning images based on pixel intensities. This approach allows for using all available image information, making it effective in environments with low texture where feature-based methods might fail.

Feature-based VSLAM methods

In the realm of VSLAM, algorithms that rely on feature detection and matching have been instrumental in enabling robots to navigate and map their environments effectively. Early stages of feature-based VSLAM, feature extraction primarily relied on corner detection methods such as Harris [Reference Kim74], Features from Accelerated Segment Test (FAST) [Reference Liu, Kao and Delbruck75], and Good Features to Track (GFTT) [Reference Meng, Fu, Huang, Wang, He, Huang and Shi76]. However, their reliability is often insufficient. Consequently, researchers now prefer more stable local image features. Modern VSLAM methods based on point features typically employ feature detection algorithms like SIFT [Reference Burger and Burge35], SURF [Reference Bay, Tuytelaars and Van Gool77], and Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF (ORB) [Reference Rublee, Rabaud, Konolige and Bradski78] to extract key points for matching images and then determined the pose by minimizing reprojection error.

MonoSLAM [Reference Davison, Reid, Molton and Stasse79], introduced in 2007, was recognized as the inaugural real-time monocular VSLAM algorithm. It was the first successful application of the SLAM methodology from mobile robotics to the ‘pure vision’ domain of a single uncontrolled camera, achieving real-time but drift-free performance. The key novel contributions included an active approach to mapping and measurement, using a general motion model for smooth camera movement, and solutions for monocular feature initialization and feature orientation estimation. In the same year, Parallel Tracking and Mapping (PTAM) [Reference Klein and Murray80] improved over MonoSLAM, addressing its instability over extended periods and in diverse environments. It was the first SLAM algorithm to employ nonlinear optimization in the back end, tackling the issue of rapid data growth in filter-based methods.

Additionally, PTAM introduced the separation of tracking and mapping into distinct threads. The front end utilized FAST corner detection to extract features and estimate camera motion, while the back end handled nonlinear optimization and mapping. This approach ensured real-time performance in camera pose calculation and maintained overall SLAM accuracy. However, due to the absence of a loopback detection module, PTAM could accumulate errors during prolonged operation.

In 2015, ORB SLAM [Reference Mur-Artal, Montiel and Tardós81] was proposed and considered a notable advancement over PTAM, as it integrated a loop closure detection module, effectively mitigating cumulative errors. In real time, this monocular visual SLAM system used ORB features to perform SLAM. The loop closure detection thread also used the word bag model named Directed Bag of Words (DBoW) [Reference Galvez-López and Tardos82] for loop closure. The loop closure method based on the BoW model could detect the loop closure quickly by detecting the image similarity and achieve good results in the processing speed and the accuracy of map construction. In subsequent years, ORB-SLAM2 [Reference Mur-Artal and Tardos83] and ORB-SLAM3 [Reference Campos, Elvira, Rodríguez, Montiel and Tardós84] were introduced and became widely utilized visual SLAM solutions due to their real-time CPU performance and robustness. However, the ORB-SLAM series heavily depended on environmental features, which could pose challenges in environments lacking sufficient texture features to extract enough feature points.

The reliance of point feature-based SLAM systems on the quality and quantity of point features presents challenges, particularly in scenes with weak textures like corridors, windows, and white walls, affecting system robustness and accuracy, potentially resulting in tracking failures. Additionally, rapid camera movement, changes in illumination, and other factors can significantly degrade the matching quality and quantity of point features. Growing interest was in integrating line features into SLAM systems to enhance feature-based SLAM algorithms. Two endpoints, represented by lines and line features, were used in the SLAM system to detect and track the two endpoints of lines in small scenes. The system could use line features alone or combined with point-line features, which was groundbreaking in VSLAM research. In ref. [Reference Perdices, López and Cañas85], a line-based monocular SLAM algorithm is proposed, which uses lines as basic features, and the UKF as a tracking algorithm. Due to the absence of loop closure and the representation of line segments as infinite instead of finite, the practical application of the scheme becomes challenging. Both [Reference Gomez-Ojeda, Moreno, Zuñiga-Noël, Scaramuzza and Gonzalez-Jimenez86], which used a monocular camera, and [Reference Pumarola, Vakhitov, Agudo, Sanfeliu and Moreno-Noguer87], which used a stereo camera, adopted the line segment detection (LSD) algorithm to detect line features and then combined the point-line features in SLAM. This approach performed well, even when most point features disappeared. Furthermore, it improved the accuracy, robustness, and stability of the SLAM system, though its real-time performance was lacking.

Direct-based VSLAM methods

In the field of VSLAM, direct methods have emerged as a significant advancement by utilizing pixel intensity information directly, thereby preserving all image details and eliminating the need for feature extraction and matching. This approach enhances computational efficiency and demonstrates strong adaptability to environments with intricate textures.

The Dense Tracking and Mapping (DTAM) algorithm [Reference Newcombe, Lovegrove and Davison88] was proposed as the first practical direct method of VSLAM. DTAM allowed tracking by comparing the input images with those generated by reconstructed maps, enabling precise and detailed reconstruction of the environment. However, it increased the computational cost of storing and processing the data, making it feasible to run in real time on a GPU. Large-Scale Direct (LSD)-SLAM [Reference Engel, Schöps and Cremers89] introduced a direct monocular SLAM algorithm that enabled large-scale, consistent maps construction with accurate pose estimation and real-time 3D environment reconstruction. The algorithm included a novel direct tracking method that detected scale-drift and a probabilistic solution to incorporate noisy depth values into tracking, enabling real-time operation on a CPU. In ref. [Reference Forster, Pizzoli and Scaramuzza90], a semi-direct monocular visual odometry algorithm was introduced, offering precision, robustness, and faster performance compared to current state-of-the-art methods. Semi-Direct Visual Odometry (SVO) combines the advantages of the feature point and direct methods. The algorithm is divided into two main threads: motion estimation and mapping. Motion estimation was carried out by feature point matching, but mapping was performed through a direct method. The research work in ref. [Reference Engel, Koltun and Cremers91] proposed Direct Sparse Odometry (DSO), which effectively utilized image pixels, making it robust even in featureless regions and capable of achieving more accurate results than SVO. DSO calculated accurate camera orientation even when feature point detector performance was poor, improving the robustness in low-texture areas or with blurred images. DSO also employed geometric and photometric camera calibration for high-accuracy estimation. However, DSO only considered local geometric consistency, leading to inevitable cumulative errors, and it was not a complete SLAM system as it lacked loop closure and map reuse.

Both feature-based and direct-based VSLAM methods have their advantages and limitations. Feature-based methods are generally more robust against varying lighting conditions and can handle larger inter-frame motions due to their reliance on distinct features. However, they may require significant computational resources for feature extraction and matching. By leveraging raw pixel intensities, direct methods can perform well in low-texture environments and offer more accurate pose estimation in specific scenarios. Nevertheless, they can be sensitive to changes in lighting and may face challenges with large inter-frame motions.

Hybrid SLAM

The development of single-sensor SLAM systems is relatively mature, with LIDAR, cameras, and IMU being the standard sensors in SLAM systems. 3D LIDAR provides the system with rich structural information about the environment, but the data are often discrete and numerous. Cameras capture color and texture in the environment at high speed but cannot directly perceive depth, and they are often perturbed by light. IMU sensitively perceives weak changes in the system within a very short time, but long-term drift is inevitable. Each of these sensors has distinct characteristics with clear advantages and disadvantages.

Single-sensor SLAM systems are fragile and uncertain, and they cannot handle multiple complex environments, such as high-speed scenes, small spaces, and open and large scenes simultaneously. As a result, hybrid SLAM has become a new trend in SLAM system development. Hybrid SLAM systems use a combination of LIDAR, cameras, and IMUs, which can be categorized into loosely coupled or tightly coupled modes as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Classification of hybrid SLAM based on LiDAR sensor.

Figure 7. An occupancy grid map which shows multiple hypotheses about the robot’s pose due to symmetry in the environment and similar lidar scans.

Loosely coupled systems: In loosely coupled systems, each sensor’s data is processed independently, and the results are later integrated to estimate the robot’s state. This approach simplifies the system architecture and reduces computational load. However, it may not fully exploit the complementary strengths of each sensor, potentially limiting accuracy in complex environments.

Tightly coupled systems: Conversely, tightly coupled systems integrate data from all sensors simultaneously, considering their interdependencies during processing. This method allows for more accurate state estimation, especially in challenging environments. However, it requires more computational resources and a more complex system design.

Recent advancements in hybrid SLAM have led to the development of systems combining LiDAR, cameras, and IMUs in loosely and tightly coupled configurations. In this paper, we categorize these works into LIDAR-IMU loosely coupled systems, Visual-LIDAR-IMU loosely coupled systems, LIDAR-IMU tightly coupled systems, and Visual-LIDAR-IMU tightly coupled systems, based on the coupling method of the system and the types of sensors being fused. The development of SLAM reflects a transition from loose coupling to tight coupling. First, we discuss Hybrid SLAM based on LIDAR, followed by visual SLAM.

Hybrid SLAM loosely coupled system

The emergence of loosely coupled systems has opened up a new stage in developing Hybrid SLAM systems. Until now, its application in low-cost platforms with limited computational power is still widespread.

-

• LiDAR-IMU loosely coupled system

The majority of loosely coupled systems were found in earlier works. The research work on the LOAM [Reference Zhang and Singh92] algorithm was the main reason why LIDAR-based 3D SLAM technology became popular and well-known. The LOAM method enabled real-time 3D mapping by combining high-frequency odometry with precise point cloud registration. LOAM aided in global localization by utilizing odometry algorithms to estimate the velocity of the lidar and correct distortion in the point cloud. By matching and registering point clouds, LOAM created a map that helped determine the position of the lidar in a global coordinate system. This process ensured accurate mapping and localization in real time, contributing to the overall success of the global localization task. Compared to the state-of-the-art LOAM, Lightweight and Ground-Optimized Lidar Odometry and Mapping (LeGO-LOAM) [Reference Shan and Englot93] is designed to be lightweight, allowing it to run efficiently on low-power embedded systems. The design minimizes the computational resources required for processing LiDAR data and performing pose estimation. It leveraged the presence of a ground plane in its segmentation and optimization steps. This ground-optimized strategy helped improve pose estimation accuracy by utilizing planar features extracted from the ground. LeGO-LOAM aided global localization by integrating loop closure detection and correction mechanisms within its SLAM framework.

-

• LiDAR-vision-IMU loosely coupled system

LIDAR odometer degradation occurs in unstructured and repetitive environments. Even with the assistance of an IMU for positioning, it still cannot work correctly for long periods. In contrast, vision sensors that do not require specific structural features, such as edges and planes, but rely on sufficient texture and color information to accomplish localization. However, vision sensors cannot obtain in-depth information intuitively. Therefore, combining a camera with LIDAR provides a complementary solution. The authors of LOAM extended their algorithms by combining feature tracking of monocular cameras with IMU in V-LOAM [Reference Zhang and Singh94]. Subsequently, the authors of V-LOAM released its iterative version, Lidar-Visual-Inertial Odometry and Mapping (LVIOM) [Reference Zhang and Singh95]. The improved method presented a data processing pipeline to estimate ego-motion online and build a map of the traversed environment, leveraging data from a 3D laser scanner, a camera, and an IMU. Unlike traditional methods that used a sequential, multilayer processing pipeline, solving for motion from coarse to fine, the system used visual–inertial coupling methods to estimate motion and perform scan matching to refine motion estimation and mapping further. The resulting system enabled high-frequency, low-latency motion estimation and dense, accurate 3D map registration.

Hybrid SLAM tightly coupled system

-

• LiDAR-IMU tightly coupled system

The study in [Reference Ye, Chen and Liu96] proposed a tightly coupled LIDAR inertial localization and mapping (LIOM) framework, which jointly optimized measurements from LIDAR and IMU. The accuracy of LIOM is better than that of LOAM. However, the proposed method has a limitation as it requires initialization. Also, slow-motion scenarios could lead to drift due to the relatively sparse local map during their runtime. The study in ref. [Reference Gomez-Ojeda, Moreno, Zuñiga-Noël, Scaramuzza and Gonzalez-Jimenez86] released a follow-up work, lidar inertial odometry (LIO) via smoothing and mapping (LIO-SAM) [Reference Shan, Englot, Meyers, Wang, Ratti and Rus97], which utilized a factor graph for multi-sensor fusion and global optimization, and employed local sliding window scan matching for real-time performance enhancement. However, since feature extraction relied on geometric environments, this method still could not work for a long time in open scenes, and LIO degradation persisted during extended movements in such environments. FAST-LIO [Reference Xu and Zhang98] proposed an efficient and robust LIO framework based on tightly coupled iterative Kalman filters for UAV systems to address this. The method fused more than 1200 feature points in real time and achieved reliable navigation results in a fast-motion, noisy, cluttered environment. To prevent the growing time of building a k-d tree of the map, the system could only work in small environments (e.g., hundreds of meters). FAST-LIO2 [Reference Xu, Cai, He, Lin and Zhang99], built on FAST-LIO, addresses the growing computation issue by introducing a new data structure, ikd-Tree, which supports incremental map updates at every step and efficient kNN inquiries. Benefiting from the drastically decreased computation load, the odometry was performed by directly registering raw LiDAR points to the map, improving the accuracy and robustness of odometry and mapping, especially when a new scan contained no prominent features.

-

• LIDAR-Visual-IMU (LVI) tightly coupled system

The advanced framework of the LIO system has facilitated the development of the tightly integrated LVI system by leveraging the optimized LVI technology over the last couple of years. LiDAR and Visual Inertial Odometry Fusion (LVIO-Fusion) [Reference Jia, Luo, Zhao, Jiang, Li, Yan, Jiang and Wang100] was a robust SLAM framework that combined stereo camera, Lidar, IMU, and odometry data through graph-based optimization for accurate localization in urban traffic. The framework utilized a self-adaptive actor-critic method in RL to dynamically adjust sensor weights, enhancing system performance across various environments. Lidar-visual-inertial odometry via smoothing and mapping (LVI-SAM) [Reference Shan, Englot, Ratti and Rus101] consisted of a Visual-Inertial System (VIS) and LIDAR-Inertial System (LIS). VIS can provide a pose prior for LIS, which provides pose estimation and accurate feature point depth for VIS initialization.

In addition, researchers developed a SLAM-based localization and navigation system for social robots, particularly the Pepper robot, to address the challenges of navigating dynamic indoor environments [Reference Alhmiedat, Marei, Messoudi, Albelwi, Bushnag, Bassfar, Alnajjar and Elfaki102]. This system enhanced Pepper’s ability to autonomously navigate and interact with humans using advanced algorithms and sensor integration. Furthermore, researchers applied SLAM using an improved wall-follower approach to an autonomous maze-solving robotic system [Reference Alamri, Alamri, Alshehri, Alshehri, Alaklabi and Alhmiedat103]. They also advanced the SLAM technique by fusing it with visible light positioning to improve robot localization and navigation, as demonstrated in ref. [Reference Guan, Huang, Wen, Yan, Liang, Yang and Liu104].

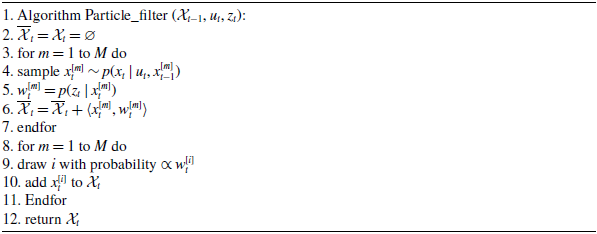

In summary, researchers took a major step forward in hybrid SLAM by developing systems that integrate Lidar, vision, and IMU to work together smoothly, along with additional sensors like wheel/leg odometers and GNSS. Similarly, the increased computational complexity is one of the most challenging problems. In addition, some details need to be optimized, such as dynamic environments, unstructured environments, rain, and snow weather. Table III shows the strengths and weaknesses of each method of hybrid SLAM. The strengths and weaknesses of existing SLAM work are compared in Table III.

Table III. Comparison of existing related work on hybrid SLAM.

2.2.4. Optimization-based approaches

Regarding the final classification, optimization-based approaches formulate localization as an optimization problem, seeking to minimize the discrepancy between predicted and actual sensor measurements. It specifically focuses on pose graph optimization and moving horizon estimation, which optimize over a finite horizon. Optimization-based approaches are divided into post graph-based optimization and moving horizon-based pose estimation for robots.

In graph-based optimization, pose graph techniques use optimization algorithms to refine the robot’s pose estimate by considering constraints and relationships between poses in a graph structure. Moving Horizon Estimation (MHE) is an advanced state estimation technique for localizing mobile robots. MHE solves an optimization problem over a finite time horizon, considering a limited set of past measurements and states, and optimizing within this window to estimate the current state. This approach helps smooth out noise and correct errors. Table IV discusses the advantages and disadvantages of both optimization approaches.

Table IV. Summary of existing methods based on optimization-based approaches.

Pose graph-based optimization

Pose graph-based optimization is a method used in robotics to estimate the robot’s trajectory and pose (position and orientation) within an environment based on sensor measurements and constraints. In this, the environment and the robot’s trajectory are represented as a graph, where each node represents a pose of the robot at a specific point in time, and each edge represents a constraint between two poses. The graph is typically called a “pose graph.” Optimization algorithms, such as Gauss–Newton or Levenberg–Marquardt, adjust the poses in the graph to satisfy all constraints while minimizing overall error. They find the poses that best explain the sensor measurements and constraints.

In ref. [Reference Yin, Carlone, Rosa and Bona105], a graph-based SLAM algorithm was proposed for indoor dynamic scenarios, consisting of local scan matching and global graph-based optimization. Local scan matching involved preprocessing the LIDAR data, detecting line features, and estimating the rotational and translational values. In contrast, global optimization constructed a topological graph using motion constraints and performed batch optimization to assess the global robot trajectory. A novel method of grid map segmentation for mobile robot global localization using a clustering algorithm and graph representation of clusters was presented in ref. [Reference Liu, Zuo, Zhang and Liu106]. The technique recovered from incorrect global localization without prior pose information, addressing the “kidnapped robot problem.” An improved method in ref. [Reference Yao and Li107] enhanced mobile robot localization accuracy by combining visual sensors, an IMU, and an odometer through tight coupling and nonlinear optimization. A monocular visual odometer that combined local and global optimization of point-line features to improve self-positioning accuracy in mobile robots was proposed in ref. [Reference Jia and Leng108]. The limitations of SLAM using a single sensor were addressed in ref. [Reference Li, Li, Tan and Hu109] by combining 2D LiDAR and RGB-D camera data for joint optimization. A grid-based visual localization system was presented in ref. [Reference Li, Zhu, Yu and Wang110], which relied on artificial markers arranged on the ceiling, with the mobile robot capturing images using an up-facing monocular camera. Comparison of two state estimation techniques, particle filters and graph-based localization, was evaluated in the context of automated vehicles [Reference Wilbers, Merfels and Stachniss111]. The study discussed the advantages of both algorithms and their ability to adapt to available computational resources at runtime.

Moving horizon estimation

MHE is mathematically formulated as an optimization problem that minimizes the discrepancy between the predicted state (based on the dynamic model) and the measured state (based on sensor data) over a moving time horizon. By integrating sensor measurements with dynamic modeling, MHE enables the robot to determine its global position within an indoor environment, even starting from an unknown location. It does this by continuously updating the localization estimate with new sensor data, allowing the robot to gradually refine its understanding of the environment and accurately locate itself within the global coordinate system.

In ref. [Reference Wang, Chen, Gu and Hu112], the three-dimensional multi-robot cooperative localization problem was addressed by introducing a novel approach based on MHE integrated with EKF for improved localization accuracy. The proposed method bounded localization error, imposed constraints on states and noises, and utilized previous range measurements for current estimation, outperforming traditional EKF-based methods. An ultra-wideband (UWB) localization algorithm for mobile robots presented in ref. [Reference He, Sun, Zhu and Liu113], which employed a moving horizon optimization, integrating a kinematic model, reference poses, and handling heavy-tailed noise in UWB ranging. Indoor UAV localization is challenging due to the absence of reliable Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) signals, requiring the development of robust sensor fusion algorithms for state estimation. An adaptive MHE implemented in ref. [Reference Sajjadi, Bittick, Janabi-Sharifi and Mantegh114] for indoor UAV localization using ArUco markers, showing improved state estimation performance compared to a high-accuracy motion tracking camera system. According to ref. [Reference Kishimoto, Takaba and Ohashi115], the focus was on distributed multi-robot SLAM using moving horizon estimation. The algorithm involved sharing sensor measurements and past estimates among robots, and it also utilized the Conjugate/Gradient minimal residual (C/GMRES) method for optimization to enhance computational efficiency. An efficient and versatile multi-sensor fusion framework based on MHE was proposed in ref. [Reference Osman, Mehrez, Daoud, Hussein, Jeon and Melek116], emphasizing its capability to handle different sensor characteristics, missing measurements, outliers, and real-time applications. The proposed scheme aimed to improve localization accuracy and robustness, with experimental results demonstrating superior performance compared to the UKF. The accuracy of SLAM using MHE in crowded indoor environments, where measured data may be insufficient, is discussed in ref. [Reference Kasahara, Tsuno, Nonaka and Sekiguchi117]. Researchers applied MHE to SLAM to improve motion model evaluation in scenarios with limited data. They conducted experiments comparing MHE-based SLAM with EKF-based SLAM and demonstrated that Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) reduced computational complexity.

Symmetrical indoor global localization

This section delves into the problem and key challenge of global localization when a mobile robot encounters a symmetrical indoor environment. Global localization in mobile robotics refers to the process by which a robot determines its position and orientation within an environment without prior knowledge of its starting location. This task becomes particularly challenging in indoor settings due to the absence of GPS signals and the prevalence of symmetrical structures. Symmetrical environments can lead to perceptual aliasing, where different locations appear identical to the robot’s sensors, causing ambiguity in position estimation. For instance, long corridors or repetitive architectural features can mislead the robot into believing it is in multiple possible locations simultaneously. This ambiguity complicates the localization process, as traditional sensors like LiDAR or cameras may not provide distinctive information to disambiguate these positions.

Addressing these challenges is crucial for enhancing the autonomy and efficiency of mobile robots across various applications, such as automated delivery systems, indoor surveillance, and service robotics. This section provides an overview of the complexities involved and outlines the existing efforts aimed at overcoming those obstacles.

3.1. Problem formulation

This paper focuses on the 2-D localization problem, meaning that the robot pose

![]() $\mathrm{x}_{t}$

at time step

$\mathrm{x}_{t}$

at time step

![]() $t\in \mathbb{Z}_{\geq 0}$

is a random variable that satisfies

$t\in \mathbb{Z}_{\geq 0}$

is a random variable that satisfies

![]() $\mathrm{x}_{t}=[x,y,\theta ]^{T}\in \mathbb{R}^{2}\times \mathbb{S}$

.

$\mathrm{x}_{t}=[x,y,\theta ]^{T}\in \mathbb{R}^{2}\times \mathbb{S}$

.

Problem 1: Given sensor observations from 2-D laser rangefinder

![]() $\mathrm{z}^{\mathbf{L}}$

, control inputs

$\mathrm{z}^{\mathbf{L}}$

, control inputs

![]() $\mathrm{u}$

, and a pre-built occupancy grid map (OGM)

$\mathrm{u}$

, and a pre-built occupancy grid map (OGM)

![]() $\mathrm{m}^{\mathrm{L}}$

, the problem of localization in ordinary environments can be formulated as the estimation of robot pose

$\mathrm{m}^{\mathrm{L}}$

, the problem of localization in ordinary environments can be formulated as the estimation of robot pose

![]() $\mathrm{x}_{t}$

:

$\mathrm{x}_{t}$

:

However, in symmetrical environments, it is tough to match the observations correctly

![]() $\mathrm{z}^{\mathbf{L}}$

with OGM

$\mathrm{z}^{\mathbf{L}}$

with OGM

![]() $\mathrm{m}^{\mathrm{L}}$

due to the high degree of symmetry in geometric features and low similarity to actual laser measurements. As a result, the robot fails to localize itself in the environment, leading to multiple hypotheses that need to be resolved correctly, as shown in Figure 8. This challenge arises because of symmetry if the environment needs proper attention to improve the localization accuracy of a mobile robot in a symmetrical scenario.

$\mathrm{m}^{\mathrm{L}}$

due to the high degree of symmetry in geometric features and low similarity to actual laser measurements. As a result, the robot fails to localize itself in the environment, leading to multiple hypotheses that need to be resolved correctly, as shown in Figure 8. This challenge arises because of symmetry if the environment needs proper attention to improve the localization accuracy of a mobile robot in a symmetrical scenario.

Figure 8. Turtlebot 3 Burger robot platform.

3.2. Key challenges

Global localization for indoor mobile robots can pose a considerable challenge in a symmetrical environment, where the surroundings exhibit significant similarities or mirror-like features, similar rooms, and long corridors. One key challenge is the ambiguity in distinguishing between such similar or symmetrically arranged features. Here are some specific aspects of this challenge:

-

• Limited discriminative features: Symmetrical structures may result in a scarcity of discriminative features that can be used for accurate localization. Without unique and easily distinguishable features, the robot may rely on less reliable cues, increasing the likelihood of misjudging its position.

-

• Vulnerable to local minima: Symmetrical environments may increase the likelihood of the robot getting stuck in local minima during the global localization process. Ambiguous features may lead the robot to converge on an incorrect position, thinking it has reached the correct location when it has not.

-