How might we learn from history in ways that help us imagine a better future? And what role might academic institutions play in making those futures imaginable? These questions animated Rosine Association 2.0, a socially engaged art project out of Swarthmore College (a Quaker-founded liberal arts college located eight miles outside of Philadelphia) that was active from 2021 to 2023. Inspired by a nineteenth-century social project in Philadelphia, an interdisciplinary collective of artists, harm reduction organizers, archivists, and activists formed Rosine 2.0 to co-imagine how harm reduction and mutual aid reduce stigma and increase social structures of community care in Philadelphia, particularly among women and non-binary people involved in street activities such as sex work and drug use.

What started as a meeting of women in 1847 to lobby for the end of capital punishment in Pennsylvania turned into a different and more local project: the Rosine Association. At least one attendee, likely self-identified Quaker Mira Sharpless Townsend, called for attention from the 500 women at the public meeting, proposing a project to address the issues of women in legal and personal peril more directly. Her idea was “the formation of a society to open a house for the reformation, employment, and instruction of females, who had led immoral lives,” or “who have wandered from the paths of virtue.” Out of a “[c]onsciousness of responsibility” for those with whom they shared community, Townsend wrote, “we are responsible in a great degree for the well- or ill-doing of those around us.” Townsend’s proposal “arrested the attention of the ladies” at the event, inspiring a “willingness to unite and give their aid.”Footnote 1 The original Rosine Association managers met with and provided housing for various women in Philadelphia at 3216 Germantown Avenue, recording their stories and those of other non-resident women in two surviving casebooks. The managers’ language evoked judgment and moral scrutiny, but, at the same time, included the view that the “customs and prejudices of society” harmed women. These competing legacies of both collective care and moral judgment thread through the contents of the Mira Sharpless Townsend Papers, held by the Friends Historical Library (FHL).

Taking inspiration from the Townsend papers and the stories of women found in the Rosine Association casebooks, the Rosine 2.0 Collective facilitated harm reduction through the development of new artistic works grounded in the activation and analysis of historical materials and contemporary conditions. Artists were key members of collaborative teams that developed two interdisciplinary public art projects—one focused on harm reduction (Mad Ecologies) and one on community healing (Circle Keepers). The project culminated in March 2023 with a multi-site exhibition presenting public art activations in a variety of media. Based on feminist and anti-racist practices, Rosine 2.0 addressed vital urban social issues—cultivating communities of care through building connections across geographies, identities, and disciplines. The Collective consisted of 20+ people, including commissioned artists, harm reductionists from grassroots groups and human services organizations, archivists, and the core management team.Footnote 2

In 2019, the core management team began planning for Rosine 2.0 around how we might build upon this historic experiment in today’s context and in ways that were informed by cultural and critical shifts prompted in part by feminist theory and Black Studies. The project was enabled by a $300,000 project grant from The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, with substantial funding from several other sources.Footnote 3 In the end, the total project costs hovered around $500,000. Now-retired Swarthmore College librarian Peggy Seiden brought folks together to ideate the project, including local activists with lived experience related to sex work and/or harm reduction. The stated goals of the project included: (1) cultivating communities of care through building connections across geographies, identities, and disciplines; (2) increasing equity and agency for our collaborators throughout the project in our decision-making, participatory practices, and a community-based archive; and (3) evolving documentation and archive practices that make visible the nuance when employing socially engaged art in an expanded field and its efficacy in creating transformative justice through harm reduction. Bringing individuals with embodied knowledge into conversation with topic experts and practitioners at the ideation stage was crucial to the success of Rosine 2.0. Too often projects bring in community members as an after thought. Conversations continued through the pandemic lockdown over Zoom, and the group considered what collective care might look like under changing social conditions. In October 2021 due to Peggy Seiden’s retirement, community engagement professional Katie Price stepped in as project director alongside project co-director and librarian Jordan Landes just in time to run Rosine School—Weekend Two, Rosine 2.0’s first in-person event.

After a year of consultations and project refinement, we held Rosine School in September and October 2021. This multi-weekend and multi-day convening was, in many ways, the beginning of our work as a collective. The event focused on community building, shared learning, and co-ideation of projects that the collective wanted to pursue over the next two years. Carol Stakenas, the project’s artistic director, shaped the processes by which the collective would work together. Zissel Aronow, the project manager of Rosine 2.0, played a pivotal role in connecting the Rosine 2.0 Collective to projects, movements, and community members in the Philadelphia area. Further on in the project, community liaison Yema Rosado helped the Collective more deeply connect with individuals and community organizations connected to pleasure activism and harm reduction. Professor Vivian Truong involved students at Swarthmore College in Rosine 2.0 through a class assignment. We also hired student research assistants who worked to connect the project with faculty and students on campus. Ultimately, Rosine 2.0 resulted in six constituent projects engaging Philadelphia community members; a major publication (that includes several smaller publications); an exhibition at Swarthmore College curated by Stakenas; and a highly successful installation event in Philadelphia curated by Aronow and Rosado that included public workshops, organizational tabling, and interactive artwork.

Rosine 2.0 exemplifies the possibilities of public humanities projects that are truly collaborative and transformative. Employing the notion of “emergent strategy” from adrienne maree brown, we saw the project as a way “for humans to practice complexity and grow the future through relatively simple interactions.”Footnote 4 These interactions are what we call “social structures of collective care.” The building of a Collective—itself committed to the creation of collaborative projects that created social networks and engaged communities—allowed the project to have ripple effects in Philadelphia more broadly. Creating social structures of care across institutional and disciplinary divides required us to pivot away from capitalist, individualist, and institutional frameworks. Shawn A. Ginwright’s notion of “four pivots” was helpful in this regard, as we conscientiously worked toward shifting from lens to mirror, transaction to transformation, problem to possibility, and hustle to flow.Footnote 5 The project went beyond interdisciplinarity by bringing together individuals with lived experience, practical expertise, and academic training through a socially engaged art practice that sought to disrupt traditional social hierarchies. The project also took inspiration from Saidiya Hartman’s concept of “critical fabulation,” which encourages us to do reparative work through imagination, and this project sought to put into action.Footnote 6 While Swarthmore College was the organizing institution, the project existed outside of traditional academic frameworks, and our commitments to each other as a Collective took precedence over external expectations. While we believe that Rosine 2.0 was exemplary in many ways, living into the values of having community partners as true co-creators is challenging, and these types of projects are still largely illegible to institutions. For example, academic institutions might ask why so much time and effort is being put into outcomes that impact external constituencies, while external collaborators and audiences might struggle to understand the role of research and teaching connected to the project.

1. The role of the archives: New audiences, paths of access, and communities

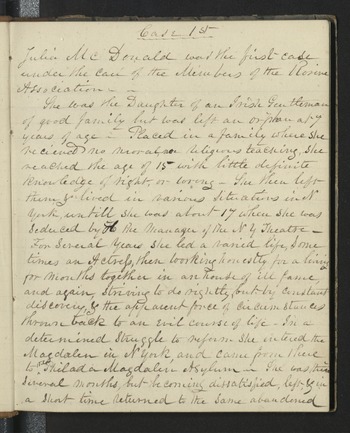

When the Mira Sharpless Townsend Papers became available for acquisition in 2019, Curator Jordan Landes, with the support of the staff of the FHL of Swarthmore College, jumped at the chance. Because we collect books, manuscripts, and archives by, about, and for members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and because we’re located in a college founded by Quaker activists, we didn’t think twice about purchasing the papers of a nineteenth-century self-identified Quaker activist. When we processed Townsend’s papers, we learned that correspondence and writings made up the bulk of the collection, giving us insight into her work/life balance and close relationship with her daughters. Amidst the papers, however, were two casebooks dated 1848–1851 and 1851–1858 (Figure 1). While her personal papers provide a snapshot of the life of a Quaker woman in the middle of the nineteenth century, these casebooks offer something much rarer: brief biographies of women whose names appear in few other sources. These women—some who had been incarcerated, unhoused, or survived abuse—told their stories to the managers of the Rosine Association, who recorded their versions of the stories into the casebooks.

Figure 1. Front cover of Rosine Association Casebook, 1848–1851, Mira Sharpless Townsend Papers. Courtesy of Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College.

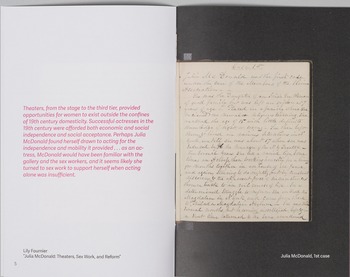

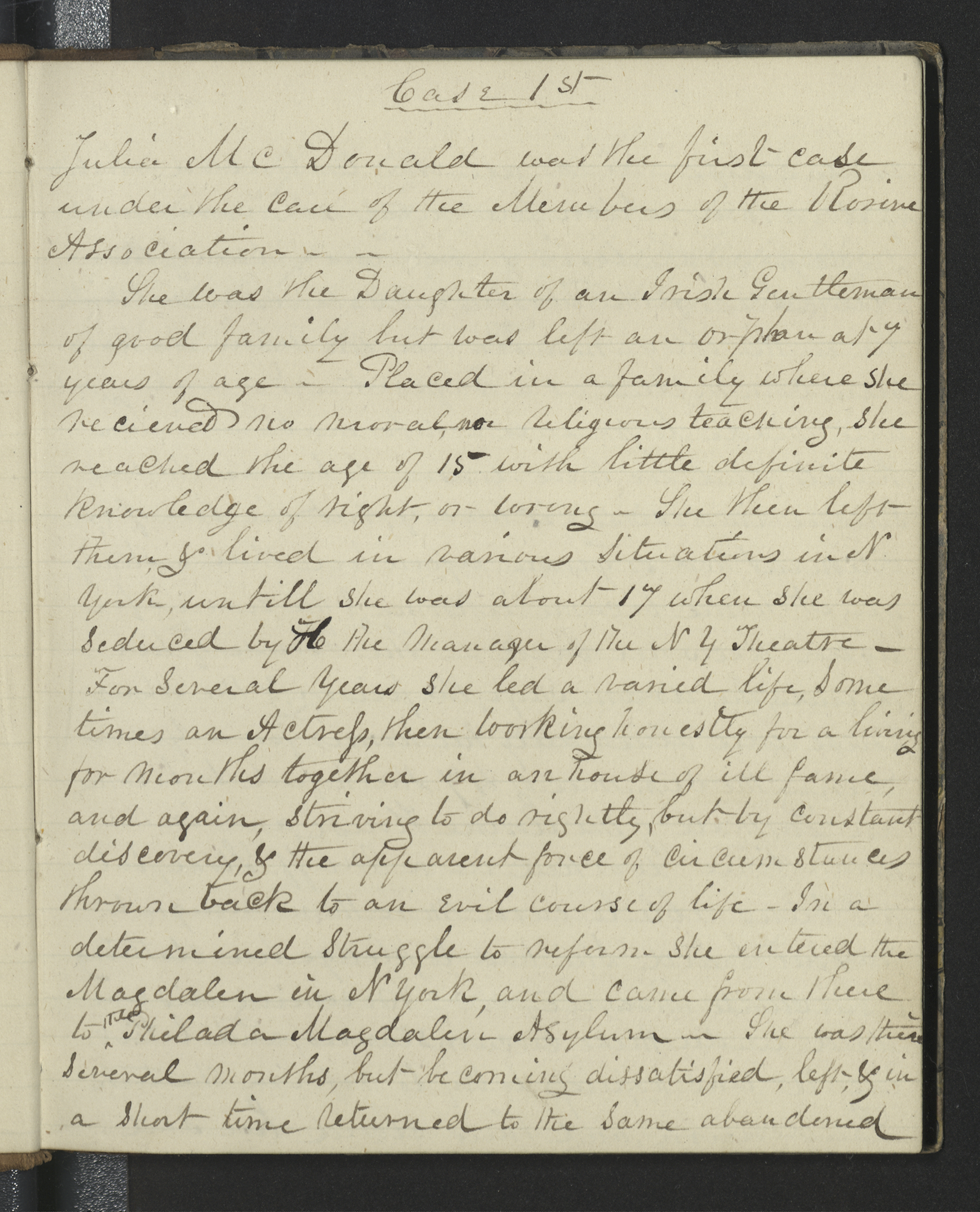

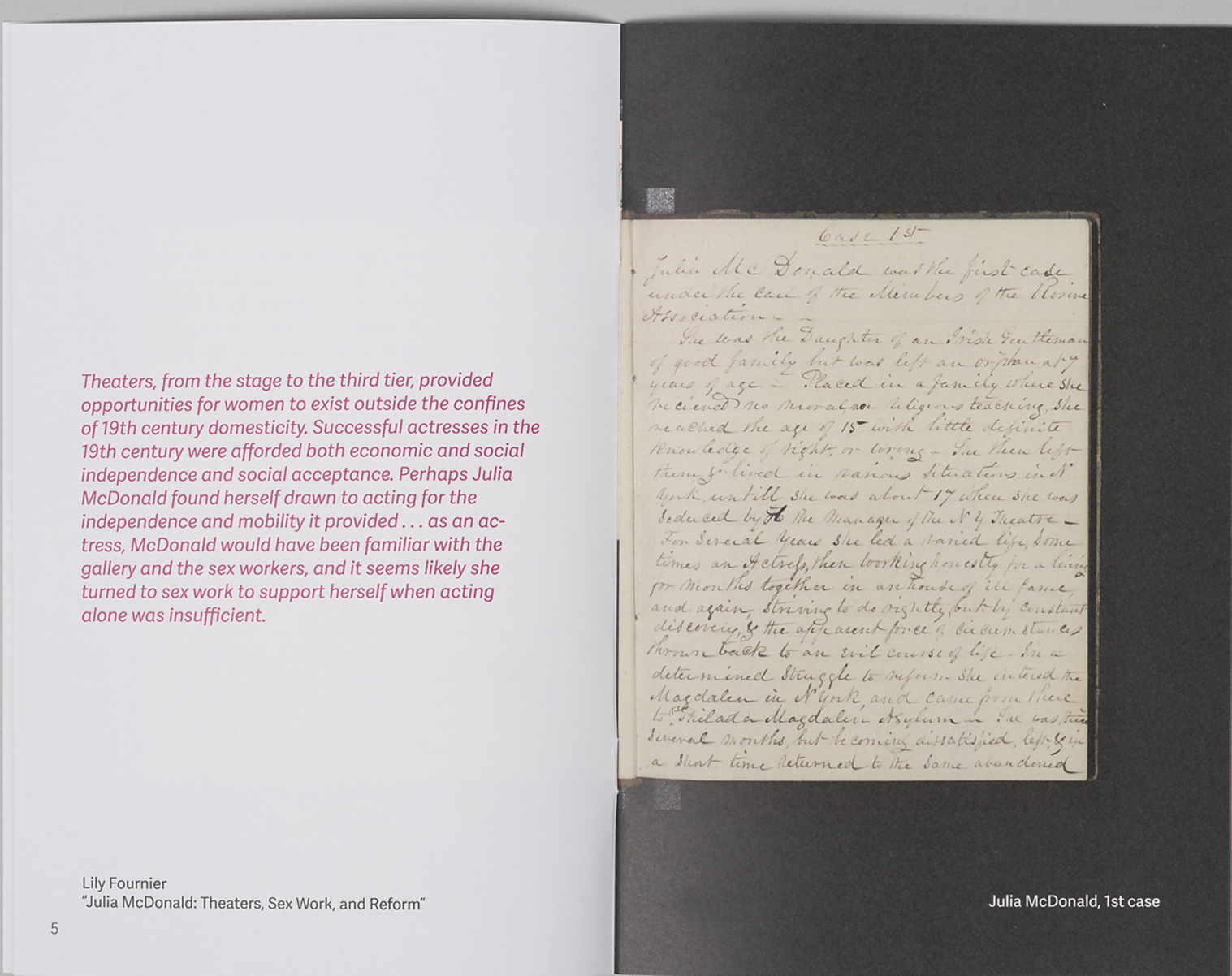

The casebooks were an inspiration for a larger project. “Julia McDonald was the first case under the care of the Members of the Rosine Association” (Figure 2).Footnote 7 McDonald arrived at Rosine House from New York in 1847. Her previous life was recorded in the casebook, which reported that she was orphaned at seven, moved to New York as a teen, and that she spent time with other aid associations and in Moyamensing Prison in Philadelphia. Townsend noted that “we have reason to believe she was Sincere in desiring it herself, but the love of excitement had so grown upon her that a steady, quiet home became irksome.” Ultimately, McDonald became “discouraged under these circumstances, and believing it was hopeless to try to reform” she took Laudanum. As Townsend wrote, this “closed her sad and eventful life,” and as she died, “a person asked her if she was going to sleep—She replied Yes! I am going to sleep now, but I shall awake in Hell.” McDonald’s case fills just over two pages of the first Rosine Association book, but, amidst language of judgment, provides us with a glimpse of a life otherwise unrecorded.

Figure 2. Rosine Association Casebook, 1848–1851, Mira Sharpless Townsend Papers, FHL-RG5-320, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, p. 7.

Wanting to make these stories available to the world, we faced the initial challenge of a project that relies on historical records: ready access to the materials. Step one: making the collection findable on Archives and Manuscripts, our archives catalog.Footnote 8 But that only allowed researchers to learn about the papers. To make the contents readable, we needed to digitize them and put them online. This is normally a difficult step for archives, but, in our case, the undertaking was made possible by FHL’s participation in a project of the Philadelphia Area Consortium of Special Collections Libraries called In Her Own Right the year of acquisition.Footnote 9 The project, with funding from various sources, including the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Council on Library and Information Resources, sought to highlight the activism of women in the Greater Philadelphia region between 1820 and 1920. This funding supported the labor involved in making the archival materials accessible through digitization and transcription, which can be a burden on staff in the absence of funding. We were lucky for In Her Own Right, as well as for the labor of FHL staff, and the result was having Townsend’s papers and the Rosine Society casebooks available freely on our digital platform within a year.

With the papers findable and accessible, we felt a responsibility to open doors into the contents of the casebooks. FHL’s Associate Curator proposed creating a dataset, inspired by the writings of Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren Klein in their book, Data Feminism. Footnote 10 Klein and D’Ignazio wrote that, because of the close relationship between data and power, creating datasets can contribute to efforts to “dismantle oppression and work towards justice, equity, and co-liberation.”Footnote 11 Inspired by the idea, a team of FHL staff and volunteers drew data from the casebooks with the main goal of increasing access by creating new entry points. Additionally, the dataset allowed us, and ultimately the larger Rosine 2.0 community, to work toward some of D’Ignazio and Klein’s goals, especially that of making women normally excluded from the record more visible.Footnote 12

Processing, transcribing, and creating the dataset made us fully aware of the biases and beliefs of their creators and reminded us that we needed to proceed with care. For example, the Rosine Association was managed by white Protestant middle-class women and sought to help white, cisgender women. The stories of the women who were interviewed by Rosine managers are mediated by the managers themselves, with moral judgments and harmful language in the text. We knew that Rosine 2.0 would need to reduce the harm in the manuscripts by including general content and specific trigger warnings and by working with a consulting historian who was embedded in the subject, Carolyn Levy. Levy, now Instructional Consultant in the Center for Teaching and Learning, UW Seattle, was the first researcher to consult the papers after they were cataloged.Footnote 13 Her research on reform efforts in the U.S. women’s prison system from the revolutionary era through the 1870s gave her the expertise needed to place the papers in their historical context for Rosine 2.0.

We felt confident about the work we did to open content to the project team and the world. But we quickly learned that digitization and transcription, and even creating the dataset, disseminated information in one direction. The Rosine 2.0 projects, students, and community members would add other directions, with information and knowledge flowing back and forth and in conversation.

2. Public humanities pedagogy: Reimagining historical methods

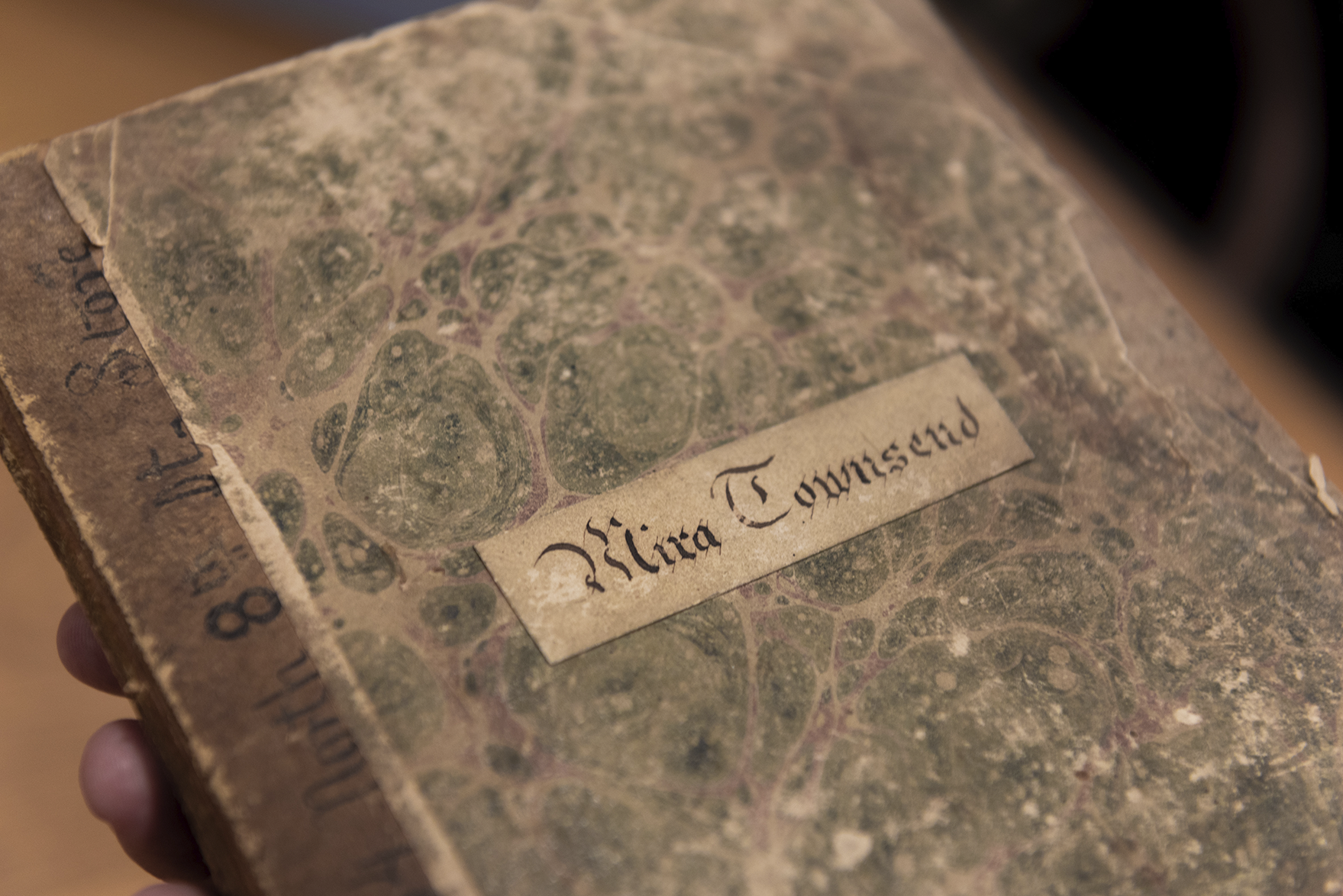

In the fall of 2021, Project Director Katie Price and Professor Vivian Truong met to discuss possibilities for incorporating students into the Rosine 2.0 project. Now that FHL staff and volunteers had digitized and transcribed 282 biographies of marginalized women in the Rosine Association casebooks, we wanted to involve students in interpreting the case files. It was Vivian’s first year teaching at Swarthmore, and the process of incorporating the project into her new “Police, Prisons, and Protest” class was one of experimentation and uncertainty—but also excitement. We discussed shaping a class assignment around the Rosine casebooks and explored how students’ work might engage in a broader conversation beyond the classroom. Given the rarity of life histories of nineteenth-century women who experienced incarceration, violence, and substance use, we decided that each student would choose one case file of a woman who passed through the Rosine Association. Students either wrote an analytical essay or developed a creative piece that brought her experiences to life (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A page of the zine Reimagining Histories, featuring an excerpt of student work alongside an image of a Rosine Association case file.

Rosine 2.0 became a pedagogical tool for students to understand and rethink historical methodology. Through the assignment, they experienced firsthand how archival silences can shape the kinds of historical narratives that can be told, especially about the lives of criminalized women. Beyond the primary source analysis and scholarly research that might be found in a traditional history course, students were also able to reimagine approaches to telling the stories of marginalized historical subjects and had the opportunity to share their work with in-person and online audiences. We displayed student writing and creative work in two exhibitions in Swarthmore’s McCabe Library, published a zine, Reimagining Histories: Rosine Association Casebook Discoveries, and featured selected writings on the Rosine 2.0 website.

Students benefited from reading scholarly work that modeled critical and creative engagements with archives. As students pored over the Rosine Association case files, they also engaged with the work of scholars who have taken a Black feminist approach to writing about the lives of criminalized women. We discussed what it meant to understand historical figures as whole, complex people, or in the words of historian Kali Gross, to “resist casting these women either as martyrs or as inherently deviant.”Footnote 14 We also discussed how existing records might limit historians’ ability to engage with the full humanity of their subjects. To understand how scholars have responded to these archival limitations, we read Sarah Haley’s No Mercy Here, which included a “speculative accounting” of an intimate friendship between two Black women who were imprisoned in a convict camp in nineteenth-century Georgia. Based on what was documented and left unsaid in archival documents, Haley writes that her speculative account “enables a historical musing upon the emotions, ambivalences, and intimacies that might have marked their experiences in the context of overwhelming violence.”Footnote 15 Students drew from Gross, Haley, and others to write and create their own narratives of the women at the Rosine Association.

Rosine 2.0 enabled students to take imaginative approaches to historical practice. Vivian prompted students to consider: What does the case file tell you about this woman’s life? About the broader context of the policing and criminalization of gender and sexuality in the mid-nineteenth century? What is captured in the biography, and what is not captured? One student chose to write about Julia McDonald as the first woman whose story was documented in the Rosine Association casebook. She analyzed McDonald’s work as an actress in the nineteenth-century theater and used scholarly sources to analyze its stigmatization as a site of sex work. The student discovered McDonald’s admission and discharge records at another women’s reform institution, the Magdalen Society. Given McDonald’s shuffling from one institution to the next—the Rosine Association, Magdalen Society, Moyamensing Prison—ultimately ending in her suicide, the student reflected on the meaning of “reform” for women who fell outside the bounds of respectable femininity. Other students, inspired by Haley, wrote their own speculative accounts in prose and poetry, grounded in their primary and secondary source research on their chosen case files. Still others wrote more traditional academic essays on topics mentioned in the individual case files, ranging from the policing of sex work to the experiences of incarcerated women in nineteenth-century Philadelphia.

For students living in a suburban residential college campus that facilitates their removal from surrounding communities, the assignment grounded students in a sense of place. Students learned about nearby Philadelphia, accessible by a half-hour ride from a train station located on campus. Many students took the assignment as an opportunity to retrace the steps of the women in their chosen case files across the city. One student photographed the sites mentioned in the biography of twenty-three-year-old Mary Ann Colton, noting the ways in which the contemporary urban landscape reflected or obscured the histories discussed in her file.

The students’ writing and creative pieces were featured in one of the first public events of Rosine 2.0: a “Reimagining Histories” exhibition hosted at Swarthmore’s McCabe Library in March 2022. The exhibition displayed student work beside archival materials from the Mira Sharpless Townsend papers and engaged participants through button making, tabling with recommended readings, and student-focused workshops on the topics of pleasure activism, housing, and sex work. The event helped the project team gauge interest in Rosine 2.0 and begin launching it to a broader audience. For students who stood by their work and conversed with attendees about what they had learned from the assignment, the event helped them understand their work as accountable to and engaged with an audience beyond their professor. They learned to care for the real women about whom they were writing, the Philadelphia community members whose experiences resonated with the women of the Rosine over one hundred fifty years later, and the growing network of people who had come together to imagine a different future.

The assignment itself relied on a structure of care that was developing within the project team. Among the lessons learned in the students’ engagement with Rosine 2.0 was the need for both support and flexibility in an assignment that expanded the boundaries of the classroom. Given the sensitive nature of the material, including discussions of students’ own experiences with gender-based violence, we also considered students’ right to privacy in the public-facing aspects of the project. We allowed students to opt in to and opt out of having their work featured in the exhibitions, website, and zine, and remain anonymous if they wished. The assignment relied heavily on the expertise of librarians and archivists to guide students through the research process—they helped students find relevant scholarly sources, access nineteenth-century maps of Philadelphia and other primary source materials, and, in some cases, locate the women of the Rosine in the records of other institutions. Project staff took on the lion’s share of the work of curating the student exhibitions and producing the Reimagining Histories zine. Ultimately, the successes of the assignment, especially the public-facing components, depended on collaboration with librarians and project staff and a willingness to experiment with the boundaries and potential of a class assignment.

3. Community engagement in institutional projects

Swarthmore College is unique among institutions of higher education in that it is dedicated to educating students in the context of peace, equity, and social responsibility—values that come from its founding as a co-educational Quaker school, even though the College is no longer directly affiliated. Endowed in 2001, the Eugene M. Lang Center for Civic and Social Responsibility plays a key role in supporting that aspect of the College’s mission. The Lang Center works closely with organizations and individuals in Philadelphia and Chester—two cities both less than 10 miles from the College—to provide learning opportunities that contribute to addressing issues of public concern. The Lang Center was a natural partner for Rosine 2.0 given its connections to Philadelphia and expertise in community engagement best practices. Katie Price, currently Director of Community Engaged Learning and Special Projects at the Lang Center, had shifted away from a traditional academic path about ten years prior to this project, seeking opportunities that allowed her to apply her humanities training in ways that made tangible differences to communities. The expertise she had gained in humanities research and teaching, the field of community engagement, and having previously co-directed a socially engaged art project positioned her to support Rosine 2.0.

The question was always at the forefront of our minds: How can Rosine 2.0 amplify community voices and perspectives and care for people beyond the College? We were committed to not repeating the sins of the past. While the group that ran the original association called themselves “managers,” we saw ourselves as “facilitators,” implementing the values of shared decision-making and responsibility crucial to collective practice. As a socially engaged art project, we strove to be an actual (as opposed to symbolic) creative social project, as artist and author Pablo Helguera puts it.Footnote 16 This meant thinking critically about how we did everything—focusing on the relationships between individuals and how they came together socially. We sought to bring shared responsibility into the project management space as well. But how do you balance the ideals of community engagement (decision-making by most impacted communities at every step, shared responsibility, etc.) with the practicalities of project implementation within a specific timeline? One particularly telling meeting occurred about a year in, when we realized that we had “Core Team” being responsible for making too many decisions jointly. We would never get anything done! So we met to re-balance roles, ensuring that different parties had responsibilities equal to the time they were able to devote to the project, that no one person was taking on too much, and that others were consulted at every stage of the project.

An important first step in including community voices and providing tangible support is hiring from within those communities. While the project did involve artists from outside of Philadelphia, the vast majority of our personnel budget went to supporting Philadelphians. This included Collective members who were active artists and activists in the City from organizations such as ProjectSAFE (a “by us, for us” sex worker and drug user cooperative) and Precious Jewels Prevention Program (a mentoring and healing program led by fifth-generation Folklore Healing Artist Folami Irvine) and our project manager and community liaison, who both have deep ties to queer and feminist movement building in Philadelphia. Another way in which we worked to increase community autonomy was through the creation of constituent project groups that had self-determination over how their funds would be used and how their project would unfold. Full-time project staff served as supports, offering a scaffolding, timeline, and designing a public programming platform onto which the autonomous projects would be linked and shared with the public. In project management meetings, we often invoked the metaphor of an umbrella: it was our job to create a safe and coherent structure under which independent projects could come together to form something greater than the sum of their parts.

We ran a Rosine School to provide a shared vocabulary and basic understanding of Philadelphia, with a particular focus on connecting the history of Philadelphia to contemporary conditions and challenges. We also built in ample opportunities to build relationships as a Collective. This was crucial in establishing shared texts and values and establishing genuine bonds. Rosine School took place over two intensive weekends. The first, held virtually in September 2021, focused on shared learning in three main areas: harm reduction, Townsend’s papers and the history of the original Association, and important Philadelphia contexts such as existing policies, systems, and movements that related to the Collective’s work. Over 20 people were involved, including project facilitators, outside experts, and Collective members who participated both as speakers and listeners. The second weekend, held in-person, began with a group reading and discussion of select casebook entries that set the tone for the day and grounded us in Philadelphia history.

Collective members who had direct experience with sex work often noticed things about the text that were quite different from those noticed by those trained in academia. Having individuals with different perspectives speak to the material enriched our understanding of the archives in profound ways. For example, during a discussion of Julia MacDonald’s case, we came to the difficult final lines, “When the Laudenum was taking effect upon her, a person asked her if she was going to sleep—She replied Yes! I am going to sleep now, but I shall awake in Hell.” While those with academic training tended to interpret that final line (and implied death by suicide) as Julia feeling that her actions would condemn her to an afterlife of suffering, community members tended to read the last line as a condemnation of the circumstances of life itself—as Julia’s reclamation of independence and a final statement that her life on earth was worse than any hell could possibly be. The remainder of the weekend focused on members of the Collective having time together in smaller workgroups to ideate their projects in the context of their learning from the first weekend. Smaller groups then came together to share with the Collective and receive feedback and consider how the different projects might complement each other.

A year later, we reflected on Rosine School and felt that it would be beneficial to have a public-facing version in anticipation of our major exhibitions in the Spring. We discussed this and imagined it as a way to take learning outside of the classroom and into the public sphere, purposely pushing against the notion that academia is the only place where knowledge is produced and circulated, and also to build an audience for our project. In 2022, we ran Rosine School—Summer Sessions, which broadened the conversation to the public and allowed a student researcher to learn more about and implement public humanities programming. Each of the six sessions occurred via Zoom and focused on a different topic: future histories, speaking truth to power, healing and community, gender justice, pleasure activism, and harm reduction. While each session looked a bit different, they generally focused on considering different texts and ideas, making connections between them, and co-ideating better futures. Each session included a provocative quote from an influential thinker such as Grace Lee Boggs or Bayard Rustin, excerpts from the Rosine Association casebooks or other relevant historical material, and quotes from members of the Collective that had emerged from our work together. In this way, the sessions became a place for us to practice one of the aims of the project: to connect Philadelphia’s past to its present and future.

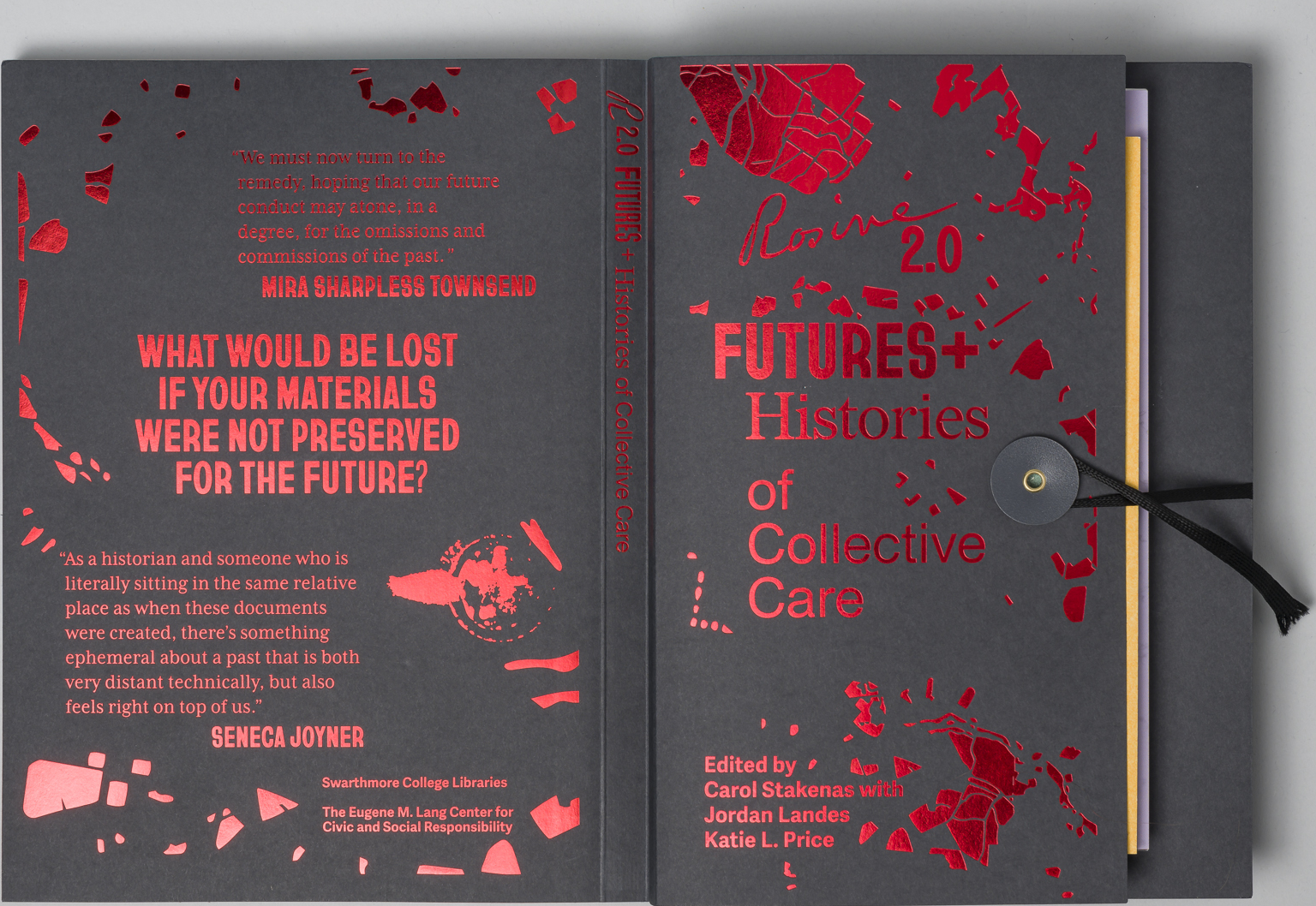

The publication that resulted from the project exemplifies the project’s commitment to both including humanities scholarship and honoring community voices. The publication consists of two main parts: a bound book and a cover that acts as a pocket to hold community-based publications related to the project (Figure 4). The pocket’s design was inspired by archival folders, acknowledging the project’s grounding in primary materials from Townsend’s papers, while gesturing to the need to save important documentation for future readers. The design of Futures and Histories of Collective Care formally supports the idea of community autonomy within an institutional framework. Because the community-based publications are not materially bound to the book, they can (and do!) circulate independently. Creators retain copyright to all of their work and are encouraged to think about how the publications might help sustain their projects. In this vein, we also arranged to have proceeds from the sale of the full publication go directly to our two primary community partners: ProjectSAFE and Precious Jewels Prevention Program. The bound portion includes the more academic and institutional representations of the project. An unexpected benefit to this design was that it also allowed for different timelines. Our community partners were expressing the need to have more time, to “move at the speed of trust,” while the designers and printers we were working with needed material earlier. When we came up with the idea for the pocket, it felt like a stroke of genius! We could get the printers the material they needed in time for production before our major public programming, and community partners could have more time to work on their contributions. Everything came together just in time, and the night before the exhibition opened, the core project team stayed late to hand-collate over 2000 books. By putting engaged scholarship and more academic conversations together with the primary texts that emerged from the project itself, the publication formally illustrates the tensions that exist between them while emphasizing their connection to each other.

Figure 4. Front and back covers of Rosine 2.0: Futures and Histories of Collective Care.

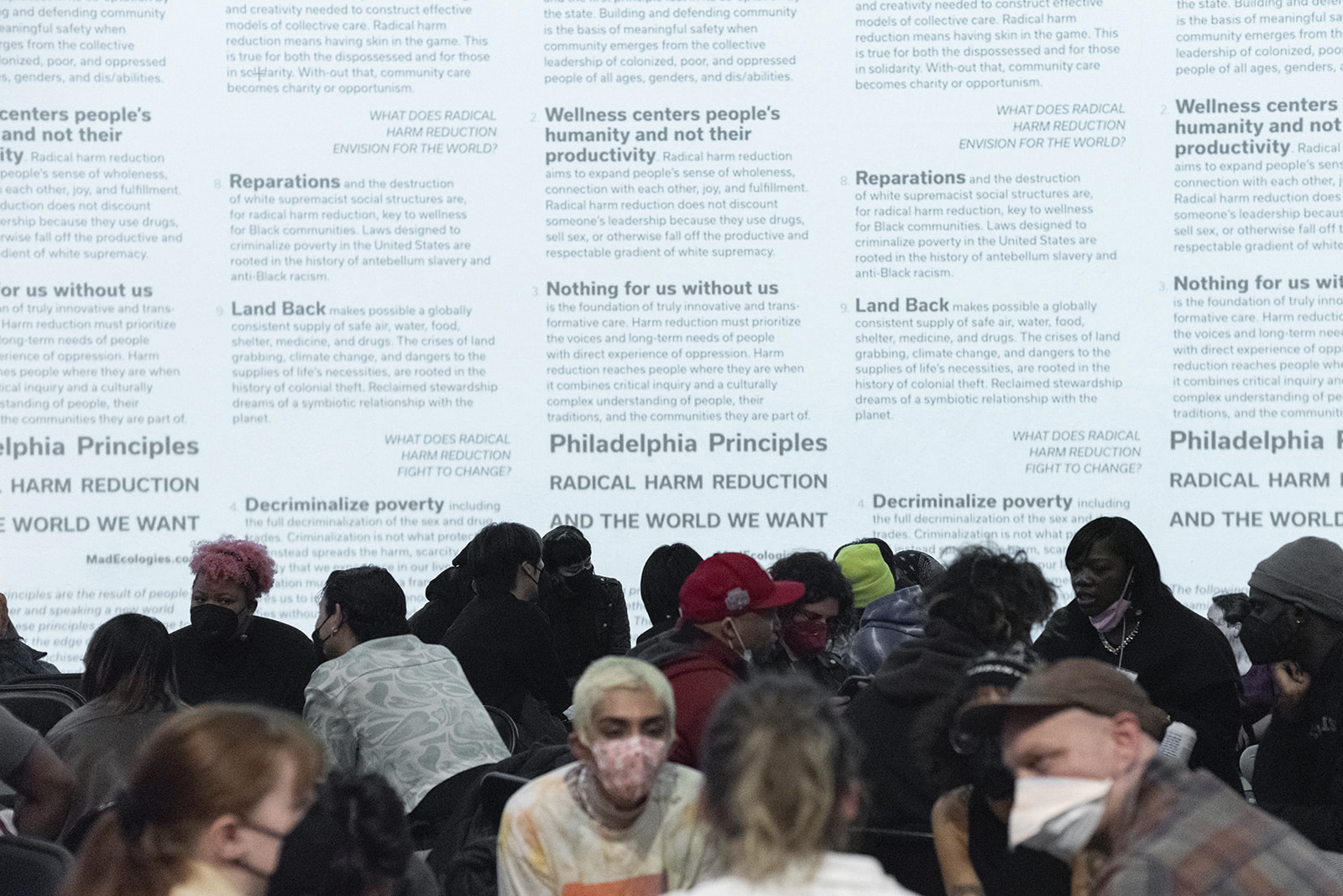

An exciting outcome of our project was how many people in the community were interested and became involved. Over 500 people attended our culminating installation, Rosine 2.0 in Practice, which featured workshops on grassroots healing, environmental justice, and radical harm reduction (Figure 5). The event featured free professional photos, interactive projects, a celebration of Philadelphia-based organizers, and free publications related to community action. We attribute this event’s success to the project’s ability to remain adaptable and committed to prioritizing community autonomy, desire, and care. For example, while two major constituent projects (Circle Keepers and Mad Ecologies) emerged from the original Rosine School, as Rosine 2.0 progressed, we saw the desire to expand and welcome other projects in. In addition to supporting three smaller projects (What Heals You?; Chat & Chew—Sex Work & You; and Nightshade Collective: Bound Together), we also offered microgrants that provided a platform for pre-existing social projects to collectively create a community-engaged artwork or participatory event for Rosine 2.0 in Practice. One attendee shared, “I thought the Icebox installation was magical. The feeling in the room was just what you want in a community space. People sharing, listening, learning, connecting. Amazing!” Another shared, “Seeing members of community have a stake in the projects about them was so beautiful usually this is only from a savior le[ns].” The level of public engagement the project received at this event was inspiring and, in our experience, rare for public humanities projects.

Figure 5. Community members participate in small group discussions during Rosine 2.0 in Practice. Icebox Project Space, Philadelphia, PA. March 18, 2023. Photographer: Devon Dadoly.

While the project’s design consciously adopted many best practices in the field of community engagement—such as including community members in the proposal and initial design of the project; opportunities for critical reflection on our own practice; and mechanisms for continual feedback and adjustment based on community desires—several challenges still arose. One of the main tensions throughout the project was that there was still a fundamental distrust of institutions among Collective members. This is not surprising, given the particularly fraught relationship between policed communities and institutions of power that have often caused them harm. Implementing a project that is inherently institutional (funded by The Pew Center and granted to Swarthmore College) while allowing for critiques of those institutions was certainly challenging. Our approach was to be as transparent as possible, discuss issues head-on, and let unresolved tensions sit with us. In a closing event for the project, Collective members and others who had become involved with the project came together for an exercise informed by Ripple Effect Mapping, a tool we discovered while reading through Imagining America’s paper on democratically engaged assessment.Footnote 17 While the exercise revealed that tensions between institutions and communities went largely unresolved, it also showed that strong relationships of trust across those divides had been built. We were overall very pleased with the feedback we received regarding the project overall, in which not a single respondent selected “disagree” or “strongly disagree” with any of our six core indicators of project success (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Data showing responses from an anonymous survey sent after the culminating events of Rosine 2.0. No question garnered responses that included the survey options “disagree” or “strongly disagree,” which is why we have excluded them here.

Another challenge common to projects such as these is that they are not immediately legible to different audiences—Is the project socially engaged art? Public humanities? Applied history? Complex and interdisciplinary projects, such as Rosine 2.0, have difficulty being legible equally to academic institutions, art worlds, and community partners. But it is also this complex situatedness in which the excitement lies. The project necessitated acknowledging different types of expertise; some discomfort and ultimately compromise by all parties; and a nimbleness to navigate different disciplines.

4. Conclusion

Working in partnership with communities from America’s “poorest big city,” one that has become representative of the nation’s opioid crisis, Rosine 2.0 did not pretend to have the answer to the problems facing Philadelphia in the twenty-first century.Footnote 18 Nor did the project seek to rescue or reform women who engaged in substance use or sex work, as the original Rosine Association did. Instead, the project aided in the creation of collective structures of community care and mutual understanding using art and archives as a point of connection.

The process of building Rosine 2.0 was as important as its outcomes. While the managers of the nineteenth-century Rosine Association aimed to reform women who “wandered from the path of virtue,” Rosine 2.0 valued the agency of sex workers, harm reductionists, and community healers as collaborators.Footnote 19 Borrowing from Eve Tuck, we took a desire-centered (as opposed to damage-centered) approach to community engagement.Footnote 20 The project challenged the “vertical” or top-down public humanities model, which often involves individual academics as the central agents in creating knowledge and sharing it with a broader audience. Rather, Rosine 2.0 reflected the public humanities’ shift toward co-creating knowledge through partnerships across and beyond campus: staff, faculty, students, and community members were all actively engaged in shaping the project.Footnote 21 Each contributed a vital set of skills and perspectives in a networked series of collaborations from libraries and archives to community partners to the classroom and back. The project allowed for rethinking relationships between past and present; between the college and community partners; and among faculty, staff, and students in the building of social structures of community care.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: J.L., K. P., V.T.

Funding statement

Major support for Rosine 2.0 was provided by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, with additional support from The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the William J. Cooper Foundation, and the Sager Fund. More information about the project can be found at rosine2.org.

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare none.