Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common psychiatric disorder with a lifetime prevalence of 20%. Reference Hasin, Sarvet, Meyers, Saha, Ruan and Stohl1,Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2 Despite a wide array of available treatments, approximately a third of patients show insufficient response to standard antidepressant treatments. Reference MacQueen, Santaguida, Keshavarz, Jaworska, Levine and Beyene3 Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an important option for these patients, and is especially effective in older individuals and in those with severe or psychotic depression. Reference MacQueen, Santaguida, Keshavarz, Jaworska, Levine and Beyene3–Reference Loef, Hoogendoorn, Somers, Mocking, Scheepens and Scheepstra6 Reported remission rates generally range from 50 to 80%. Reference Dierckx, Heijnen, van den Broek and Birkenhäger4,Reference Loef, Hoogendoorn, Somers, Mocking, Scheepens and Scheepstra6 Although ECT is often viewed as a last-resort treatment, it is more effective in patients with fewer treatment failures and less chronicity, thereby supporting its consideration as a viable option earlier in the treatment algorithm for MDD. Reference Dierckx, Heijnen, van den Broek and Birkenhäger4,Reference Loef, Hoogendoorn, Somers, Mocking, Scheepens and Scheepstra6–9 Despite its efficacy, approximately 50% of patients experience relapse within the first 12 months following successful ECT, most commonly within the first 6 months. Reference Jelovac, Kolshus and McLoughlin10,Reference Bourgon and Kellner11 This relapsing course imposes a significant burden on patients, their families and society. Reference Kupferberg and Hasler12–Reference Greenberg, Chitnis, Louie, Suthoff, Chen and Maitland14 Notably, similar relapse rates have been reported following successful pharmacotherapy in the STAR*D trial, underscoring the chronic and recurrent nature of MDD. Reference Rush, Trivedi, Wisniewski, Nierenberg, Stewart and Warden15 However, patients receiving ECT typically represent a subgroup with more severe, chronic or otherwise distinct forms of depression. Consequently, relapse prevention in this population may require more intensive or tailored strategies than those recommended for the general MDD population.

Improving long-term outcome following successful ECT is a priority for the field. Reference Kellner16 Studying predictors of relapse, optimising ECT itself and improving relapse-prevention strategies are means to improve the understanding of relapse and optimise long-term outcome. One study found that patients with psychotic features, greater severity and no prior medication resistance had a lower relapse risk following ECT, although this was limited to those receiving nortriptyline and is not generalisable. Reference Pluijms, Vinther, Kamperman and Birkenhäger17 Other, mostly observational, studies examining clinical or treatment factors (e.g. electrode placement, use of medication and comorbidity) have yielded inconsistent results. Reference Yang, Lin and Chen18–Reference Nordenskjöld, von Knorring and Engström21 In the absence of clear evidence identifying which patients are most at risk, relapse prevention remains essential for all individuals who respond to ECT.

In practice, several prevention strategies are available to reduce the risk of relapse in MDD, including pharmacotherapy, neuromodulation, psychotherapy and various combinations of these approaches. Reference Jelovac, Kolshus and McLoughlin10,Reference Youssef and McCall22,23 In a 2013 meta-analysis, Jelovac et al concluded that both continuation pharmacotherapy and continuation ECT (C-ECT), defined as ECT administered regularly during the first 6 months following remission, effectively reduce the risk of relapse, with antidepressant medication shown to reduce relapse rates by approximately 50% compared with placebo. Reference Jelovac, Kolshus and McLoughlin10 A subsequent systematic review by Youssef and McCall, which included three RCTs comparing two or more relapse-prevention strategies, found that the combination of C-ECT and continuation pharmacotherapy was the most effective approach. Reference Youssef and McCall22 Similarly, Brown et al supported the efficacy of C-ECT and maintenance ECT (M-ECT), with M-ECT referring to ECT given beyond 6 months to prevent recurrence, particularly when used in conjunction with antidepressants. Reference Brown, Lee, Scott and Cummings24 More recently, a meta-analysis by Lambrichts et al suggested that the addition of lithium may confer superior relapse prevention compared with regimens without lithium. Reference Lambrichts, Detraux, Vansteelandt, Nordenskjöld, Obbels and Schrijvers25

Despite these findings, the available evidence remains limited in both scope and quality, because previous reviews often excluded non-randomised designs and focused mainly on biological interventions, with little attention being paid to psychological or novel approaches. A comprehensive reassessment, requiring an integrated evaluation, is therefore warranted. Broadening the inclusion criteria to encompass a wider range of study designs will allow for a more complete synthesis of the existing evidence. Moreover, an integrated evaluation of all major relapse-prevention strategies, including pharmacological, neuromodulatory, psychological and combined approaches, within a single review, will provide a consolidated resource for clinicians and researchers alike. Finally, more recent studies may include emerging interventions, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and (es)ketamine which, although commonly viewed as novel avenues in the treatment of difficult-to-treat depression, have not yet been comprehensively assessed in the context of relapse prevention following ECT. Together, these efforts will expand the current evidence base and support more informed clinical decision-making regarding effective relapse prevention following successful ECT for MDD.

Method

This systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman26 A preregistered protocol is available via Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PROSPERO, no. CRD42023392575; registration date 28 January 2023).

Search strategy and study selection

The electronic databases PubMed, Embase, PsychInfo and Cochrane Library were searched up to 1 March 2025. The search strategy was developed by J.J.E.R. under the supervision of an experienced librarian (Supplement 2 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10946). To retrieve as many studies as possible, no limit on publication date was applied. Following the removal of duplicates, titles and abstracts were independently screened by authors J.J.E.R. and N.T.v.Z. using Rayyan (a web-based systematic review software, Rayyan Systems Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA, used on the Windows platform, https://www.rayyan.ai). Articles found to be potentially eligible were selected for full-text screening. Discrepancies in eligibility were discussed between the two reviewers to reach consensus. When consensus could not be reached, a third author (P.F.P.v.E.) was consulted to make the decision. Thereafter, full texts of the selected articles were independently screened by J.J.E.R. and P.F.P.v.E. and discussed until consensus was reached. Initial data extraction from the included studies commenced on 29 April 2025.

Eligibility criteria

We applied the following eligibility criteria:

-

(a) case studies or series (>ten cases), prospective cohort studies, retrospective cohort studies and RCTs;

-

(b) participants 18 years of age or above;

-

(c) diagnosed with unipolar MDD by clinical judgement or formal diagnostic criteria (e.g. DSM-IV, DSM 5);

-

(d) treated with an acute course of ECT for MDD that led to response or remission;

-

(e) relapse was defined on the basis of clinical judgement, formally through the use of depression rating scales (e.g. Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D)) or using formal diagnostic criteria;

-

(f) assessing the efficacy of at least one relapse-prevention strategy following a successful course of ECT for MDD, and with a follow-up of at least 3 months.

The following exclusion criteria were applied:

-

(a) primary diagnoses other than unipolar MDD (e.g. bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, personality disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder);

-

(b) full-text articles published in languages other than English or Dutch;

-

(c) in studies including mixed diagnostic groups (e.g. both unipolar and bipolar depression), only those in which the unipolar subgroup was analysed separately were eligible for inclusion.

Other diagnostic groups, such as bipolar disorder, were excluded, because this differs from unipolar depression in course, pathophysiology and guideline-recommended relapse-prevention strategies, which could confound interpretation of treatment effects.

Risk of bias and quality appraisal

Authors J.J.E.R. and P.F.P.v.E. independently assessed the internal validity of the included RCTs using the Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) assessment tool for randomised controlled trials. Reference Sterne, Savović, Page, Elbers, Blencowe and Boutron27 Appraisal of the methodological quality of all included articles was performed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018. Reference Hong, Pluye, Fàbregues, Bartlett, Boardman and Cargo28 J.J.E.R. and P.F.P.v.E. performed appraisal independently and afterwards reached consensus on the conflicting scores.

Due to the narrative nature of the synthesis, formal assessment of publication bias (e.g. funnel plots or Egger’s test) was not feasible. Instead, we searched clinical trial registries (e.g. ClinicalTrials.gov) and grey literature sources (e.g. ResearchGate, Google Scholar, ProQuest) to identify completed but unpublished studies or relevant trial protocols.

Data extraction

Data were extracted on study design, population characteristics (e.g. age, gender), type and details of the relapse prevention strategy, outcome measures and key results. Because no new RCT data had been identified since the last systematic review by Youssef and McCall, a meta-analysis was not conducted. Instead, the findings were synthesised in a narrative review, structured according to the intervention and level of evidence, in order to provide a comprehensive and integrative overview of the current literature.

Outcomes

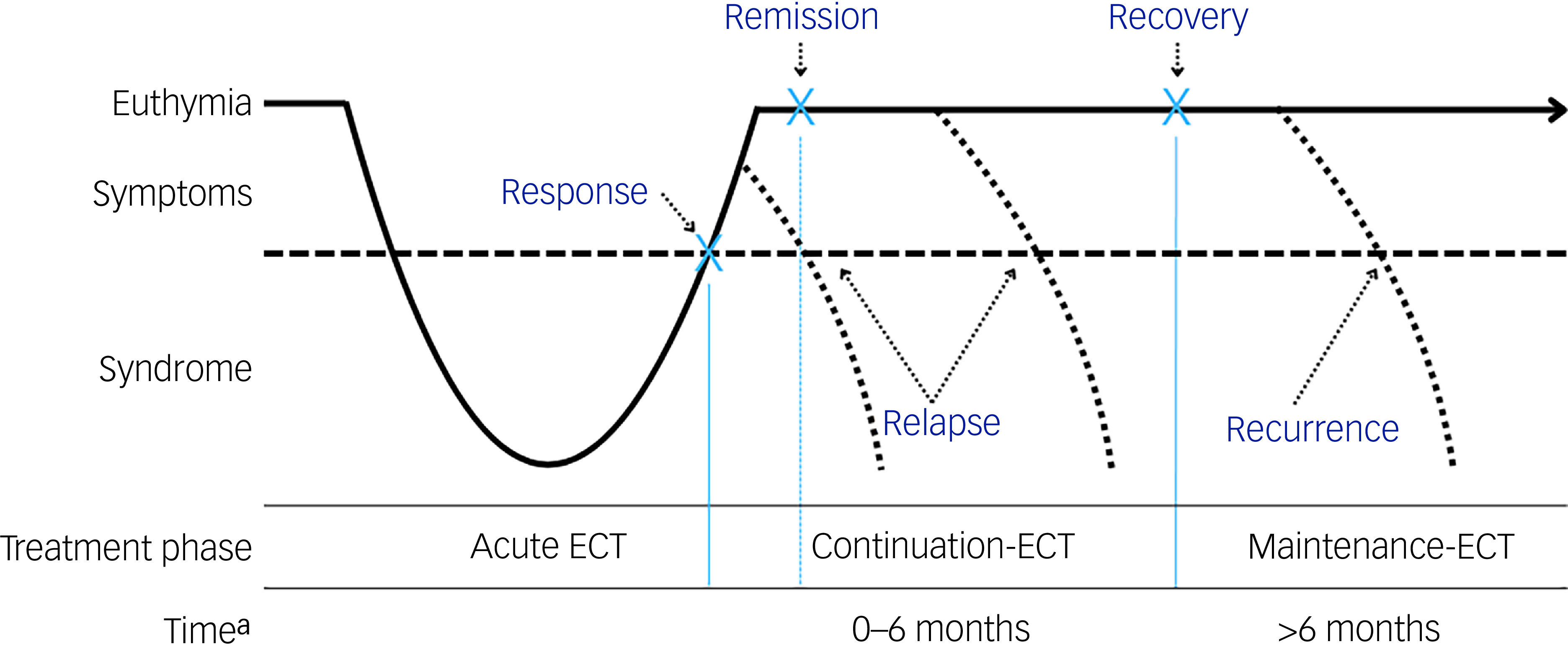

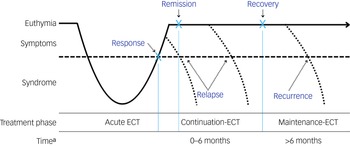

The primary outcome is the relapse rate following a successful (response/remission) course of ECT. Response generally refers to a clinically meaningful reduction in depressive symptoms, whereas remission denotes the virtual absence of symptoms and a return to a euthymic state (Fig. 1). Reference Nierenberg and DeCecco29 Different definitions of relapse and recurrence of depression exist. Relapse is defined by Frank et al as indicating a return to full depressive symptomatology beyond the clinical threshold for a diagnosis, but before the individual has reached a full recovery. Recurrence occurs when an individual experiences a new depressive episode after full recovery has been achieved. Reference Frank, Prien, Jarrett, Keller, Kupfer and Lavori30 In ECT studies, relapse is often heuristically defined as a return to full depressive symptomatology within the first 6 months following response or remission, while recurrence is defined as return of depression after 6 months. Reference Brown, Lee, Scott and Cummings24 However, in most studies, these terms are often used interchangeably. For the purposes of this review, we wanted to cover both relapse and recurrence within the first 12 months following ECT.

Fig. 1 Overview of response, remission, relapse and recurrence in relation to the electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) treatment phase.

a. Time represents time since completion of the acute ECT course.

The operationalisation of relapse varied among studies, such as specific cut-off scores on depression severity rating scales, based on clinical judgement and rehospitalisation and/or suicide. All different outcome measure definitions were extracted and included in this review, to ensure the most comprehensive overview of studies into relapse-prevention strategies. The secondary outcomes were time to relapse, risk of relapse (e.g. hazard ratio) and descriptive results.

Results

Study selection

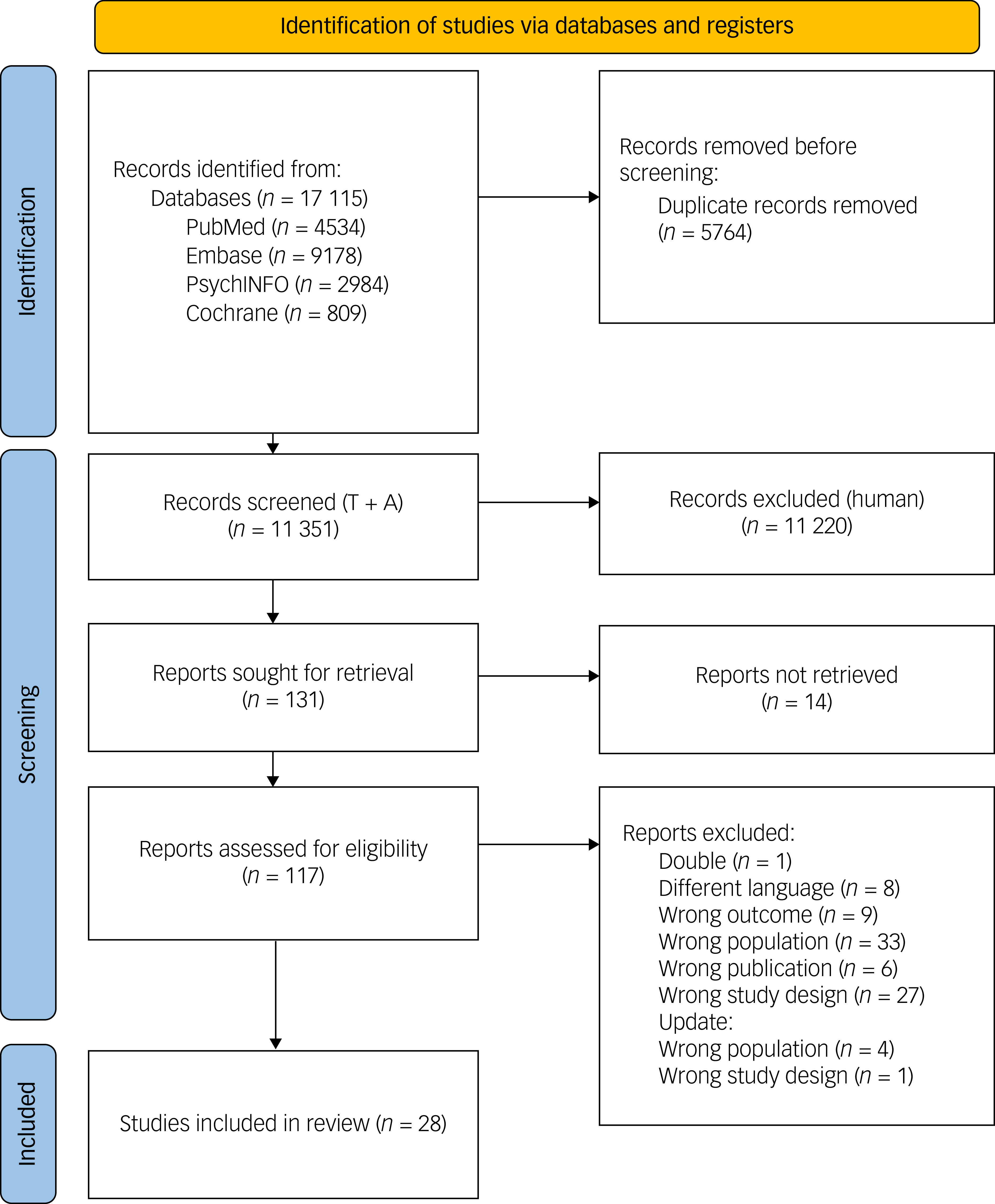

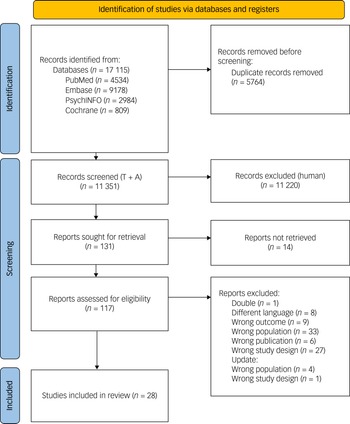

A total of 17 115 records were identified through a literature search up to 1 March 2025. Following removal of duplicates, 11 351 titles and abstracts were screened. Of these, 117 full-text articles were assessed, with 28 meeting the inclusion criteria. The selection process is outlined in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 Flow diagram of the study selection process. T + A, title and abstract.

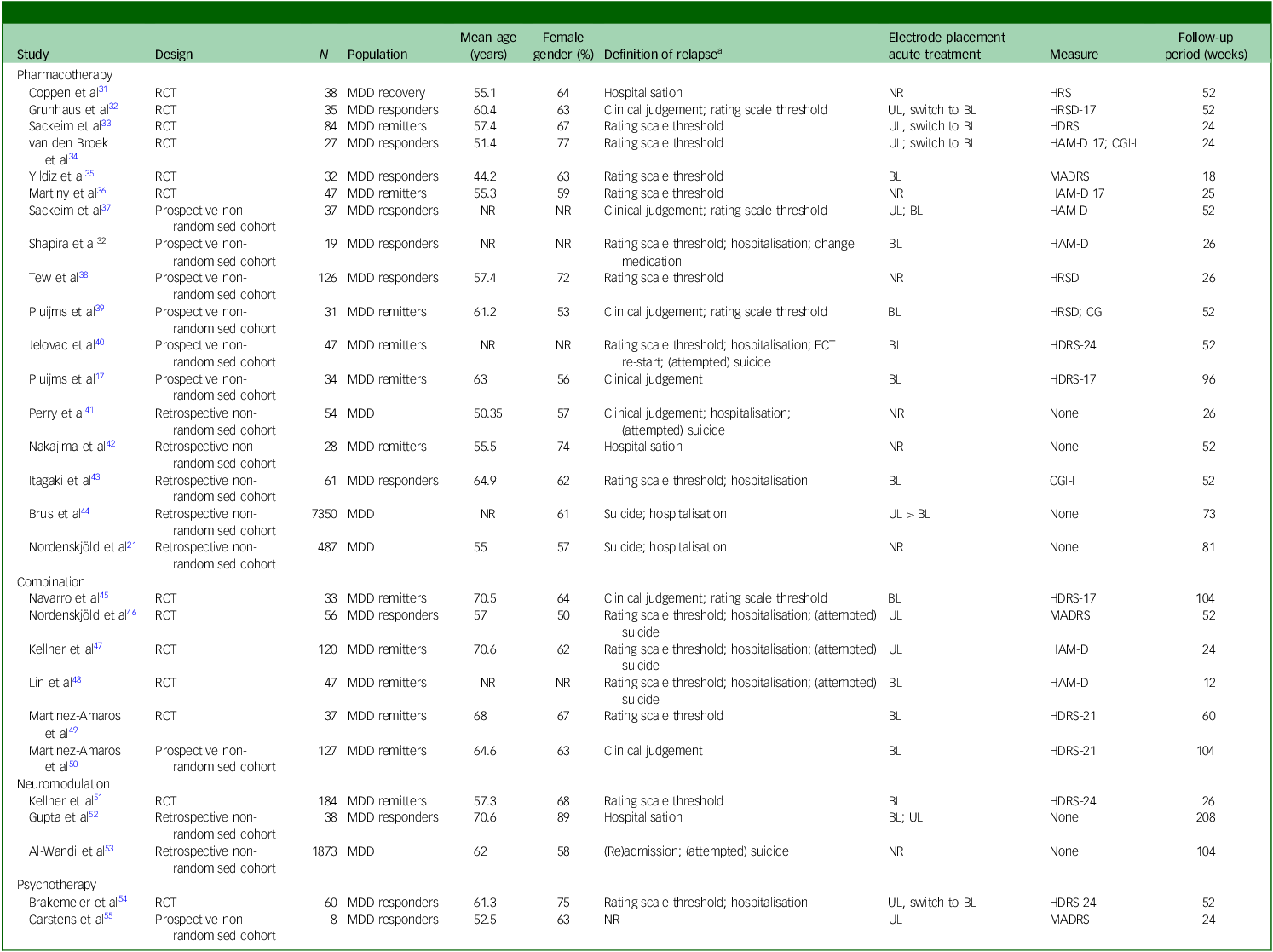

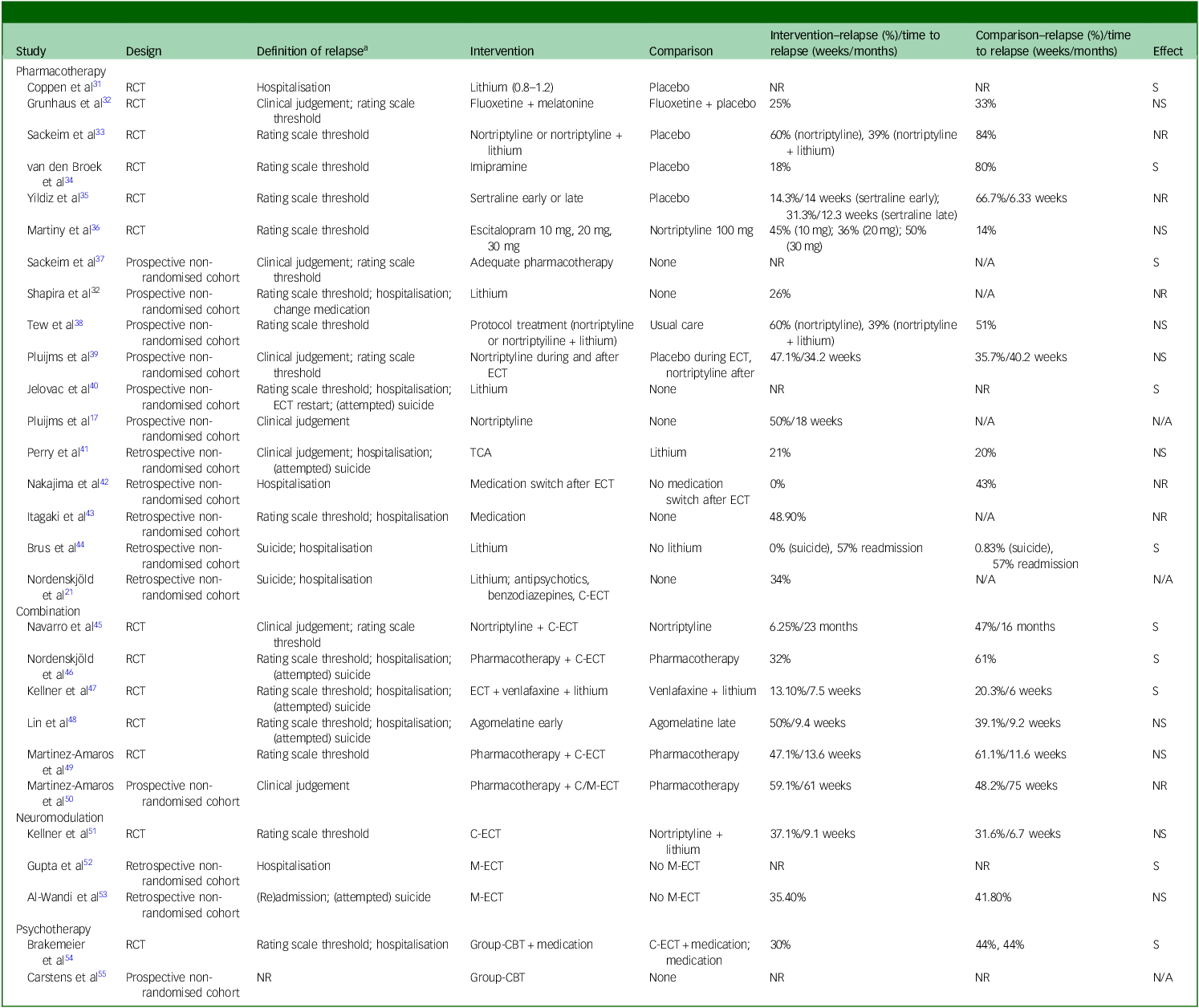

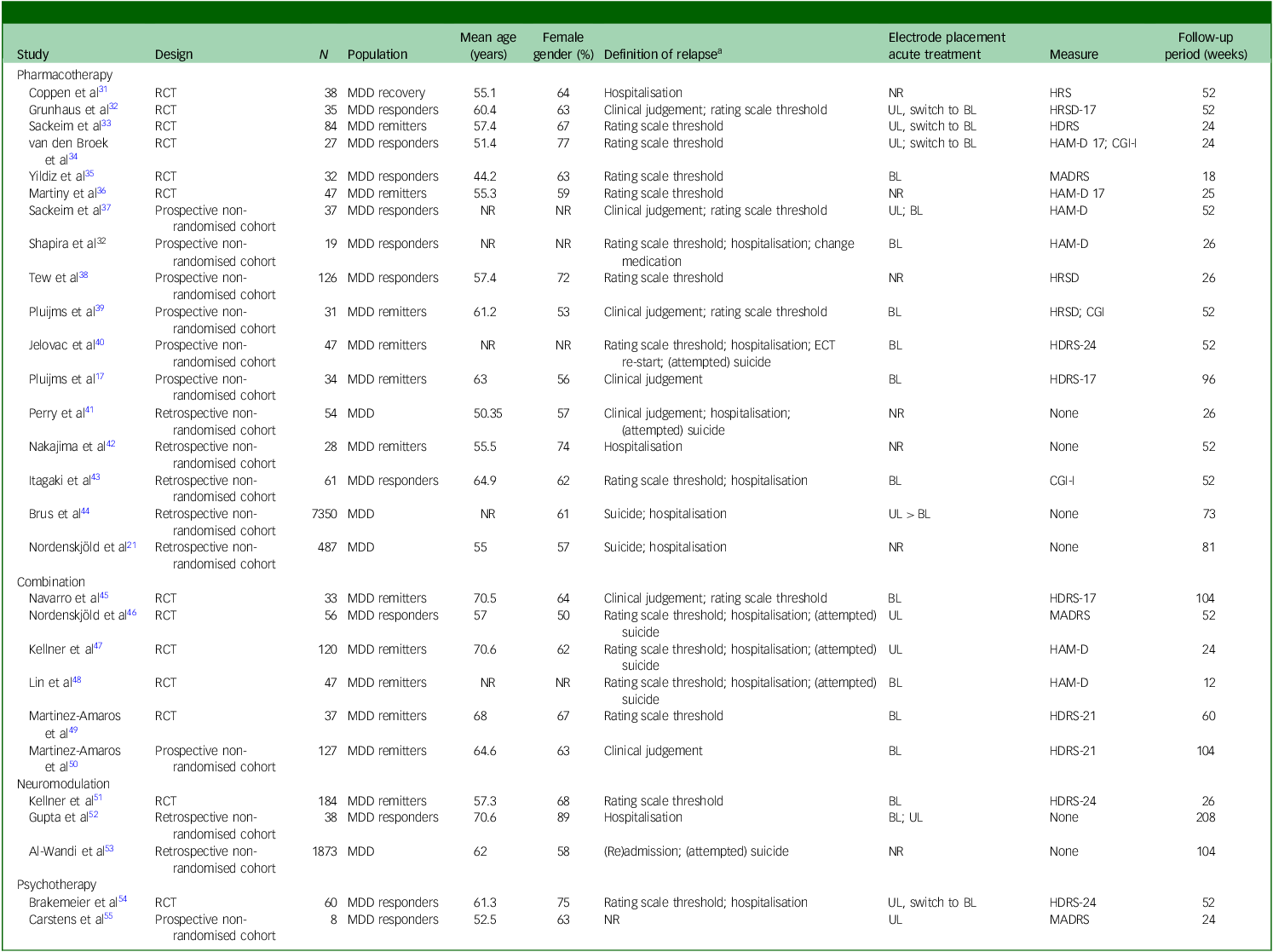

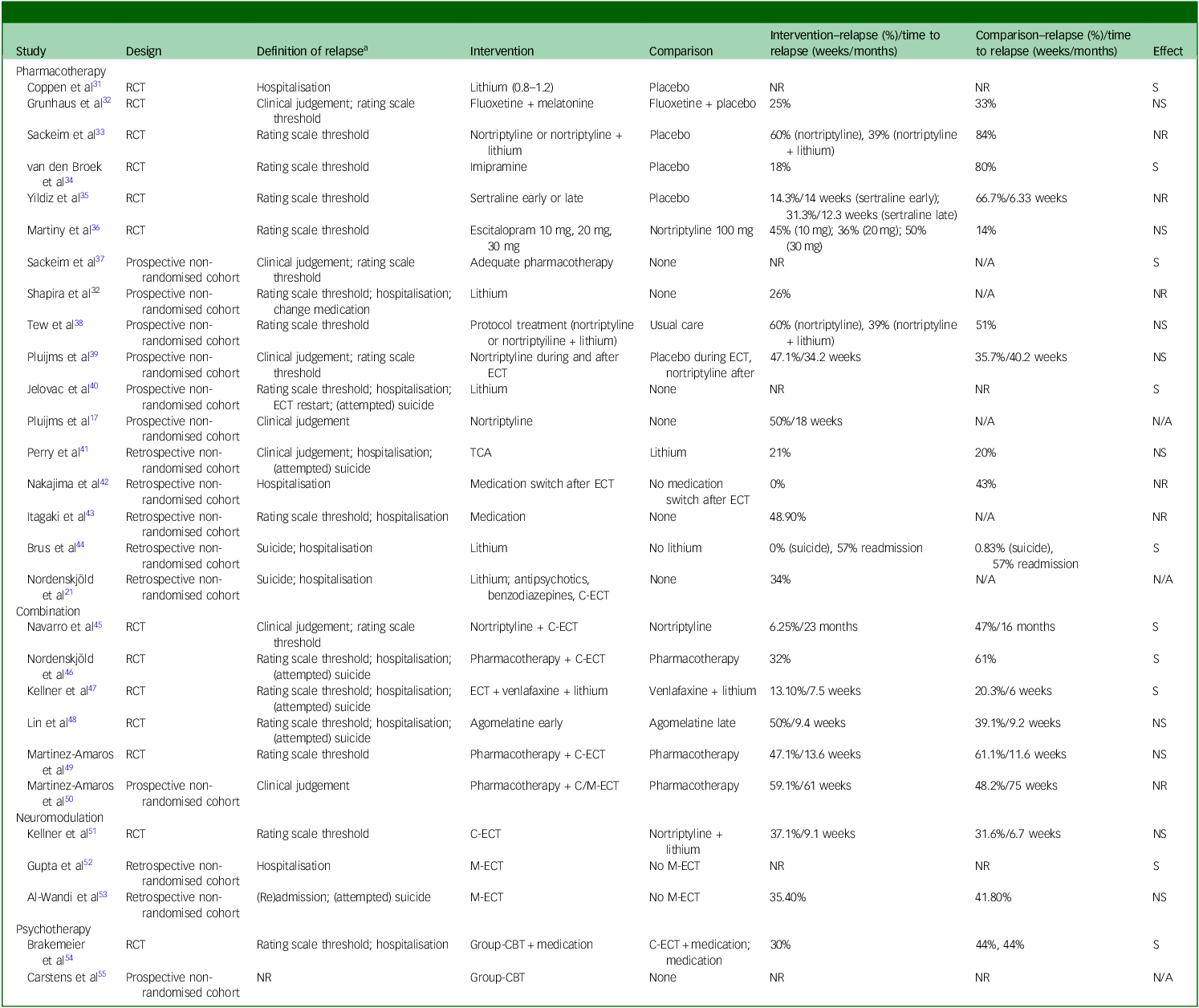

The literature search identified studies examining pharmacotherapy, neuromodulation, psychotherapy and their combinations as relapse-prevention strategies following successful ECT for MDD. A summary of study characteristics and outcomes is presented in Tables 1 and 2 and Supplement 6; key findings are highlighted below.

Table 1 Characteristics of studies on relapse-prevention strategies following successful electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for major depressive disorder (MDD)

RCT, randomised controlled trial; NR, not reported; HRS, Hamilton Rating Scale; UL, unilateral; BL, bilateral; HRSD/HAM-D/HDRS, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression 17, 21 and 24 items versions; CGI-I, Clinical Global Impressions – improvement scale; MADRS, Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

a. Detailed study-specific definitions are provided in Supplementary Table 6.

Table 2 Outcomes of studies on relapse-prevention strategies following successful electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for major depressive disorder (MDD)

RCT, randomised controlled trial; NR, not reported; S, significant; NS, not significant; N/A, not applicable; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; C-ECT, continuation electroconvulsive therapy; M-ECT, maintenance electroconvulsive therapy; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy.

Definition of relapse, study-specific criteria used to operationalise relapse.

Pharmacotherapy

Seventeen studies examined the use of various pharmacological agents for relapse prevention following successful ECT. These included six RCTs, six prospective non-randomised cohort studies and five retrospective cohort studies. The studies compared different pharmacological strategies, either to placebo or among one another. In three RCTs that included a placebo condition, relapse rates ranged from 67 to 84% over follow-up periods of 18–24 weeks in the placebo group.

Lithium

The earliest RCT by Coppen et al showed that 38 responders receiving lithium had lower scores on HAM-D at 1-year follow-up following ECT Reference Coppen, Abou-Saleh, Milln, Bailey, Metcalfe and Burns31 . However, these authors had used a narrow relapse definition (only those episodes requiring admission), initiated randomisation during ECT rather than following remission and reported outcomes as ‘weeks ill’ rather than relapse proportion, which limits comparability with more recent trials. In a landmark RCT, Sackeim et al (n = 84 remitters) demonstrated that a combination of nortriptyline and lithium significantly prolonged time to relapse and reduced relapse rates compared with both placebo and nortriptyline monotherapy over a 24-week follow-up period (39% nortriptyline + lithium, 60% lithium and 84% placebo). Reference Sackeim, Haskett, Mulsant, Thase, Mann and Pettinati33 In this trial, remission at study entry was defined using strict criteria, which might have resulted in a selected remitter sample that differs from typical clinical populations. The frequent follow-up assessments may also have increased the detection of early symptom return across all treatment arms.

Shapira et al prospectively followed ECT responders treated with lithium monotherapy for 6 months post-ECT, and reported a relapse rate of 26% among 19 patients with unipolar depression, lower than rates typically reported in the literature. Reference Shapira, Gorfine and Lerer56 Jelovac et al found that lithium maintenance therapy significantly reduced the risk of relapse following ECT, and that lithium was associated with a lower hazard of relapse despite lower mean lithium blood levels compared with the bipolar group. Reference Jelovac, Kolshus and McLoughlin40 In that study, remitters had been on lithium prior to, during and following ECT (until relapse or up to 12 months), and were allowed to use concurrent antidepressant medication, which complicates the interpretation of the specific effect attributable to lithium.

Brus et al, using Swedish national registry data (n = 7350), found that patients who collected lithium subscriptions, often together with antidepressants, following ECT had a 16% lower risk of hospital readmission, and no suicides occurred in the lithium group. Reference Brus, Cao, Hammar, Landén, Lundberg and Nordanskog44 Perry et al (n = 54) retrospectively compared lithium with tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) for relapse prevention and found no significant difference in relapse rates over 6 months (20% in the lithium group versus 21% in the TCA group), Reference Perry and Tsuang41 but these retrospective data may suffer from ‘bias by indication’ and the study predated standardised diagnostic criteria, which limits comparability with modern RCTs. Using data from a regional Swedish quality register, Nordenskjöld et al (n = 487) reported that lithium was associated with reduced relapse risk, as measured by rehospitalisation and suicide. Reference Nordenskjöld, von Knorring and Engström21 Although their large sample is a clear strength, registry data do not provide information on actual lithium intake, dosage or adherence, and subtle relapse events that do not lead to hospital contact are not captured, which requires cautious interpretation of the observed protective association.

Finally, in a retrospective chart review, Itagaki et al (n = 20 responders) found that lithium may be effective in preventing relapse. Reference Itagaki, Takebayashi, Shibasaki, Kajitani, Abe and Okada-Tsuchioka43 However, the small sample, retrospective design and non-standardised pharmacotherapy substantially limit the interpretability of lithium’s apparent effect. Collectively, these studies support the potential preventive value of lithium, as both monotherapy and an augmenting agent, in reducing relapse following ECT. However, it remains unclear whether lithium is most effective as a stand-alone treatment or in combination with antidepressants, particularly given the methodological limitations of the individual studies.

Antidepressants

Van den Broek et al (n = 27 responders) conducted an RCT comparing imipramine with placebo and found that the former significantly reduced relapse rates following ECT (80% relapsed on placebo versus 15% in the imipramine group). Reference van den Broek, Birkenhäger, Mulder, Bruijn and Moleman34 In this study, post-ECT HAM-D scores were low (mean 4.9–5.9), the total sample size was smaller (n = 27) than intended (n = 74) and assessors of the Global Clinical Impression scale were probably unblinded, because they also conducted the HAM-D ratings. These factors may have contributed to the large difference observed between groups. Pluijms et al (n = 31 remitters) evaluated the timing of nortriptyline initiation in a prospective follow-up study following a RCT, and found no significant difference in relapse rates between patients who started nortriptyline during the ECT course and those who initiated it subsequently. Reference Pluijms, Kamperman, Hoogendijk, van den Broek and Birkenhäger39 In the same cohort, Pluijms et al reported relapse rates of 32% at 6 months, 44% at 12 months and 50% at 24 months, which is considerably higher than in the imipramine trial by van den Broek et al and might be a better representation of current realistic relapse rates. Reference Pluijms, Vinther, Kamperman and Birkenhäger17 In a RCT, Martiny et al (n = 47 remitters) compared nortriptyline with varying doses of escitalopram and found only a marginal, non-significant advantage for nortriptyline, with overall low relapse rates. Reference Martiny, Larsen, Licht, Nielsen, Damkier and Refsgaard36 The enrolment rate was lower than planned, although sample size was eventually similar to that in other continuation studies. The required discontinuation of psychotropic medication following randomisation complicates interpretation of the outcome. The potential preventive effect of initiating sertraline early (during or immediately after ECT) was investigated by Yildiz et al (n = 32 responders), who found it to be superior to both delayed initiation and placebo in time to relapse. Reference Yildiz, Mantar, Simsek, Onur, Gökmen and Fidaner35 However, the sample size was small, resulting in a shortage of statistical power to detect significance between two active treatment arms. Nakajima et al (n = 28 remitters) reported that switching to an antidepressant with a different pharmacological mechanism (e.g. TCA to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)) following successful ECT was associated with lower relapse rates, suggesting that continuing with pre-ECT medication may be suboptimal. Reference Nakajima, Ishida, Akaishi, Takahata, Kitahata and Uchida42 They based their conclusions on a rather small and unbalanced sample, (n = 7 versus n = 21), and the outcomes rely mainly on readmission and a measure of social functioning for schizophrenia. By contrast, Sackeim et al (n = 37) reported no difference in relapse risk between responders with or without prior TCA resistance. Reference Sackeim, Prudic, Devanand, Decina, Kerr and Malitz37 Finally, Tew et al (n = 126 responders), in a naturalistic follow-up study, found no difference in relapse rates between protocol-guided treatment, defined as structured pharmacotherapy with nortriptyline alone, nortriptyline plus lithium or placebo and treatment as usual, suggesting that high relapse rates may not be solely attributable to the so-called efficacy–effectiveness gap (the difference between ideal trial conditions and real-world clinical practice). Reference Tew, Mulsant, Haskett, Joan, Begley and Sackeim38 However, the high loss to follow-up (29%) may have resulted in an underestimation of relapse in the usual-care group.

Other agents

Several studies have investigated alternative pharmacological strategies beyond the commonly recommended TCA–lithium combination for relapse prevention following ECT. In a RCT, Grunhaus et al (n = 35 responders) found no added benefit of melatonin when combined with fluoxetine, compared with fluoxetine plus placebo. Reference Grunhaus, Hirschman, Dolberg, Schreiber and Dannon32 However, they reported relatively low relapse rates in both groups. Although patients were clinically followed for 1 year following ECT, relapse was formally evaluated only at the 3-month time point. This shorter effective assessment window, together with the small sample size, may have contributed to the low observed relapse rates. Using data from a regional Swedish quality register, Nordenskjöld et al (n = 487) reported that antipsychotics and benzodiazepines were not associated with reduced relapse risk, as measured by rehospitalisation and suicide. Reference Nordenskjöld, von Knorring and Engström21 These findings should be interpreted in light of the inherent strengths and limitations of registry data, as discussed above. In a retrospective chart review, Itagaki et al (n = 61 responders) found that valproate may be effective in preventing relapse, while no such benefit was observed for various antidepressants or second-generation antipsychotics, although the small retrospective sample and heterogeneous treatment limit interpretation. Reference Itagaki, Takebayashi, Shibasaki, Kajitani, Abe and Okada-Tsuchioka43 No additional studies on alternative pharmacological agents, such as (es)ketamine, were identified.

Overall, pharmacological relapse-prevention strategies appear to reduce relapse rates following ECT. Among these, lithium, as either monotherapy or an augmenting agent, has the most robust and consistent evidence for efficacy across various study designs. In contrast, evidence for antidepressants remains limited in both quantity and methodological quality.

Neuromodulation

C-ECT/M-ECT

Four studies, one RCT and three retrospective cohort studies, have examined the role of C-ECT and M-ECT in relapse prevention. In a well-designed RCT, Kellner et al (n = 184 remitters) compared C-ECT (10 sessions over 6 months following bilateral-index ECT) with a pharmacological strategy of nortriptyline plus lithium. Reference Kellner, Knapp, Petrides, Rummans, Husain and Rasmussen51 Relapse rates did not differ significantly between the two groups (C-ECT, 37.1%; nortriptyline plus lithium, 31.6%), suggesting comparable efficacy. Notably, both groups showed substantially lower relapse rates than placebo or nortriptyline monotherapy, as seen in studies such as Sackeim et al, supporting the effectiveness of C-ECT and nortriptyline plus lithium as a relapse-prevention strategy. Reference Sackeim, Haskett, Mulsant, Thase, Mann and Pettinati33 However, data from a regional Swedish quality register reported by Nordenskjöld et al (n = 487) found no association between C-ECT (mean 12 ± 15 sessions) and reduced relapse risk, as indexed by psychiatric hospitalisation or suicide, in a more chronically ill subpopulation. Reference Nordenskjöld, von Knorring and Engström21 Similarly, a Swedish population-based register study by Al-Wandi et al (n = 1873) found that M-ECT (defined as receiving ECT withing 14 days following discharge) in patients with psychotic unipolar depression was not significantly associated with reduced risk of readmission or suicide in the full sample. Reference Al-Wandi, Landén and Nordenskjöld53 However, in patients over 65 years of age, M-ECT was associated with a significantly lower risk, suggesting age-dependent benefits. These registry findings should be interpreted with caution, because registry data capture only severe relapse events and do not record actual symptom return, which may mask more subtle differences between treatment strategies and could partly explain the discrepancy with the effects of C-ECT reported in clinical trials. Finally, M-ECT, defined as ECT to prevent recurrence (following 6 months of remission) with no fixed end-point, was suggested to play a role in reducing both the rate and duration of hospital stay in a small retrospective cohort study by Gupta et al (n = 38) in 19 responders, and in a like-wise comparison group receiving other maintenance therapies. Reference Gupta, Tobiansky, Bassett and Warner52 Overall, C-/M-ECT may be effective, especially in older adults.

rTMS

No studies were identified that examined rTMS as a relapse-prevention strategy following ECT for unipolar MDD.

Psychotherapy

Two studies examined psychotherapy as a relapse-prevention strategy following successful ECT for MDD. In a RCT, Brakemeier et al (n = 60 responders) compared group cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) plus pharmacotherapy with C-ECT (weekly for 4 weeks, biweekly for 8 weeks and monthly for 3 months) plus pharmacotherapy and pharmacotherapy alone. Reference Brakemeier, Merkl, Wilbertz, Quante, Regen and Bührsch54 Sustained response at 6 and 12 months was significantly greater in the group-CBT arm, suggesting that adjunctive group-CBT may be an effective and well-tolerated approach to maintaining ECT response. The continuation ECT arm performed unexpectedly poorly. This might be due to a small and highly treatment-resistant sample, fewer C-ECT sessions than other schedules used in studies, substantial dropout in the ECT arm or the absence of standardised nortriptyline–lithium pharmacotherapy, all of which limit interpretability. Carstens et al conducted a small prospective study of eight MDD responders who received group-CBT in addition to individualised pharmacotherapy, C-ECT and supportive psychotherapy. Reference Carstens, Hartling, Aust, Domke, Stippl and Spies55 They observed further reductions in depressive symptoms following group-CBT, indicating a possible benefit in prolonging treatment response. Their sample is, however, too small from which to draw any conclusions. Although the addition of psychotherapy as a relapse-prevention strategy seems a promising and feasible approach, the evidence base is currently insufficient to draw firm conclusions.

Combination of strategies

A total of six studies were included, comprising five RCTs and one prospective non-randomised cohort study. These studies compared the efficacy of a combined approach involving C-/M-ECT and pharmacotherapy, as opposed to sole reliance on pharmacotherapy. In a RCT by Navarro et al (n = 33) involving older remitters with psychotic unipolar depression, the combination of C-ECT (weekly treatment for the first month, every 2 weeks for the following month and then monthly) and nortriptyline was more effective in preventing both relapse and recurrence than nortriptyline monotherapy. Reference Navarro, Gastó, Torres, Masana, Penadés and Guarch45 However, the study sample was limited to older patients with psychotic depression and each group had four drop-outs, substantially reducing the sample size and resulting in imprecise estimates and limited generalisability. Similarly, Nordenskjöld et al (n = 56 responders) conducted a RCT comparing a range of pharmacotherapy strategies with and without C-ECT (weekly for 6 weeks and thereafter every 2 weeks for 46 additional weeks: a total of 29 ECTs for the full year), and found significantly lower relapse rates in the combined treatment group (32 versus 61%). Reference Nordenskjöld, von Knorring, Ljung, Carlborg, Brus and Engström46 Nevertheless, interpretation is limited by early termination of the trial, absence of blinded assessments, heterogeneous pharmacotherapy and broadened inclusion criteria that allowed the entry of patients with Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) scores <15.

Kellner et al (n = 120 remitters) reported favourable outcomes when adding C-ECT to venlafaxine and lithium. Relapse rates at 6 months were lower in the combined group (13.3%) compared with pharmacotherapy alone (20.3%). Reference Kellner, Husain, Knapp, McCall, Petrides and Rudorfer47 In that study, C-ECT was delivered using the symptom-titrated, algorithm-based longitudinal ECT (STABLE)) protocol, starting with four fixed sessions following remission followed by individualised sessions. Due to the complex study scheme used, the authors noted that sampling bias was introduced due to the unwillingness of severely depressed patients to participate. Also, the reported low relapse rates in both groups were probably due to the strictly defined remitter sample, combined venlafaxine–lithium treatment in all patients and intensive STABLE monitoring, which was the primary aim of the study. Nevertheless, it supports the benefit of continuing ECT post-remission rather than abrupt discontinuation. In a smaller RCT by Martínez-Amorós et al (n = 37 remitters), relapse rates were lower in the group given C-ECT (weekly for 4 weeks (4 sessions), every 2 weeks for 2 months (4 sessions), and monthly for 6 months (6 sessions), up to a total of 14 sessions in 9 months) plus pharmacotherapy (35%) than in the pharmacotherapy-only group (61%), although the difference was not statistically significant due to early termination and insufficient power. Reference Martínez-Amorós, Cardoner, Gálvez, de Arriba-Arnau, Soria and Palao49 In another RCT by Lin et al (n = 47 remitters) combining agomelatine with an acute ECT course did not reduce relapse compared with initiation of agomelatine following ECT. Reference Lin, Yang, Chen and Cai48 This finding is somewhat difficult to compare with other continuation studies because the follow up period of 3 months was shorter than the typical 6–12 months used in most trials. Finally, Martínez-Amorós et al (n = 127 remitters) conducted a prospective cohort study with a 2-year follow-up, reporting high relapse rates in both groups: 59.1% with C-/M-ECT (weekly and then monthly (median of 40 weeks and 13 sessions) plus pharmacotherapy, and 48.2% with pharmacotherapy alone. Reference Martínez-Amorós, Cardoner, Soria, Gálvez, Menchón and Urretavizcaya50 This unexpected difference probably reflects selection bias, because C-/M-ECT was preferentially prescribed to patients with more severe illness and greater treatment resistance. These naturalistic outcomes contrast with the lower relapse rates seen in RCTs, and underscore the challenges of long-term relapse prevention in routine care. Overall, the evidence suggests that the addition of C-ECT to pharmacotherapy may enhance relapse prevention compared with pharmacotherapy alone, although variability in study design, power and population size limits definitive conclusions.

Integrated synthesis of relapse-prevention strategies

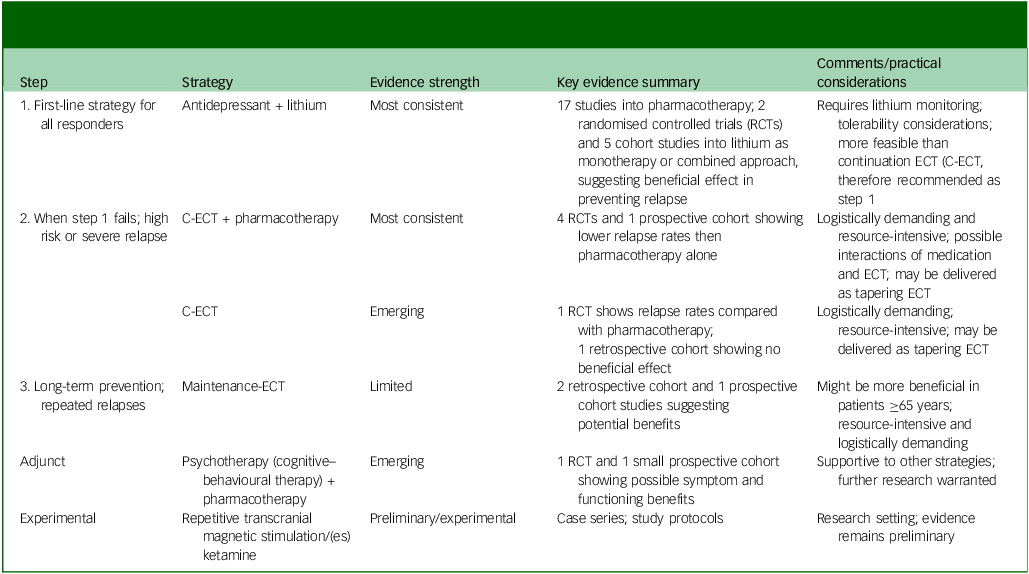

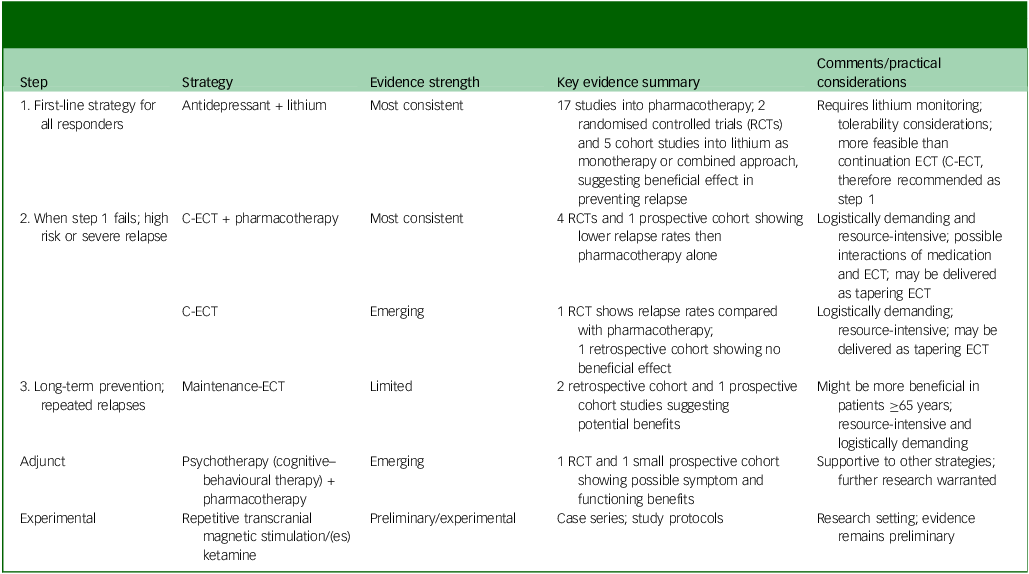

An integrated summary of relapse-prevention strategies, their typical clinical sequencing and qualitative evidence strength is provided in Table 3.

Table 3 Stepwise approach of relapse-prevention strategies following successful electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for unipolar depression, with corresponding qualitative evidence grading

RCT, randomised control trial; C-ECT, continuation ECT.

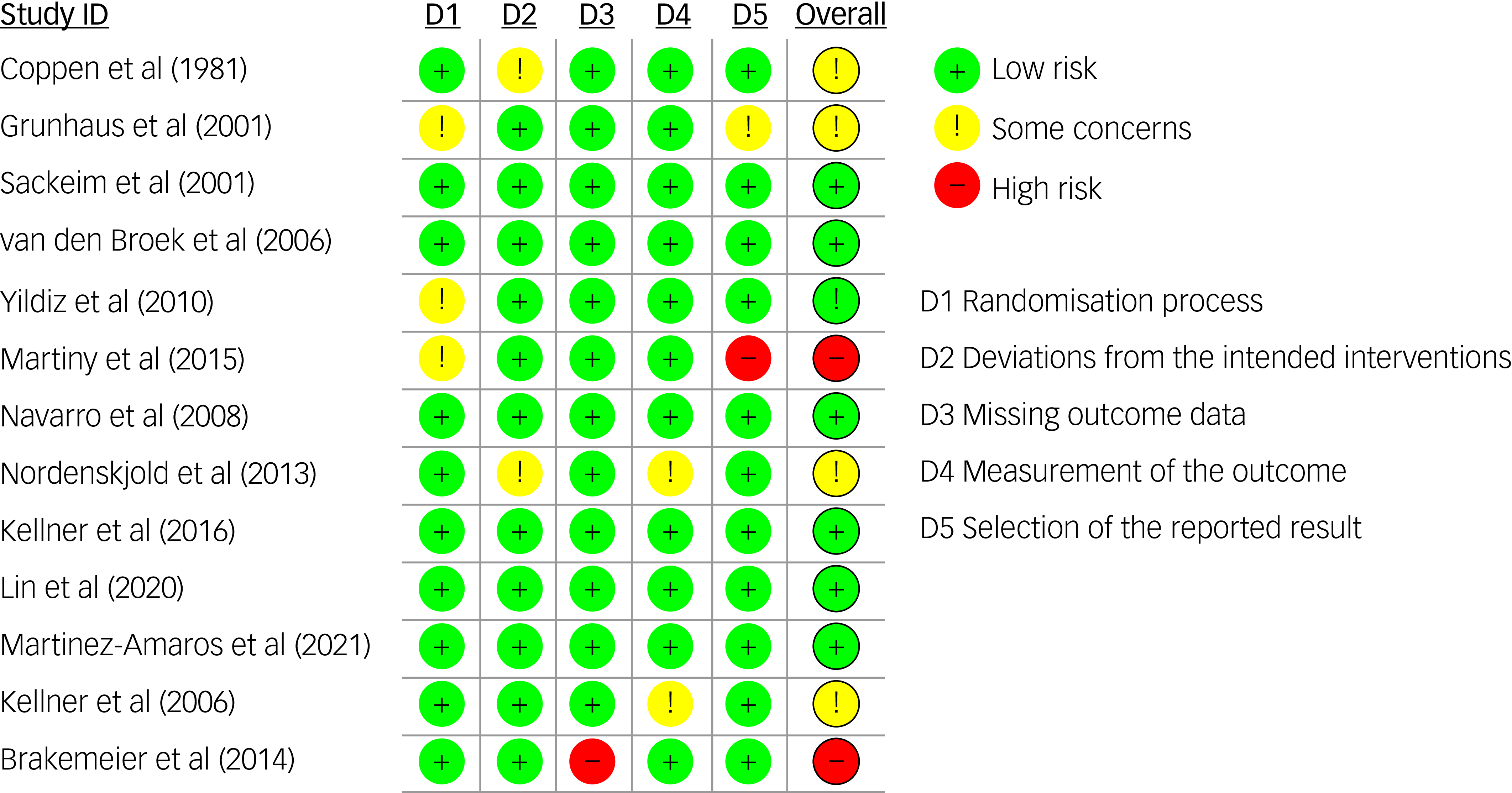

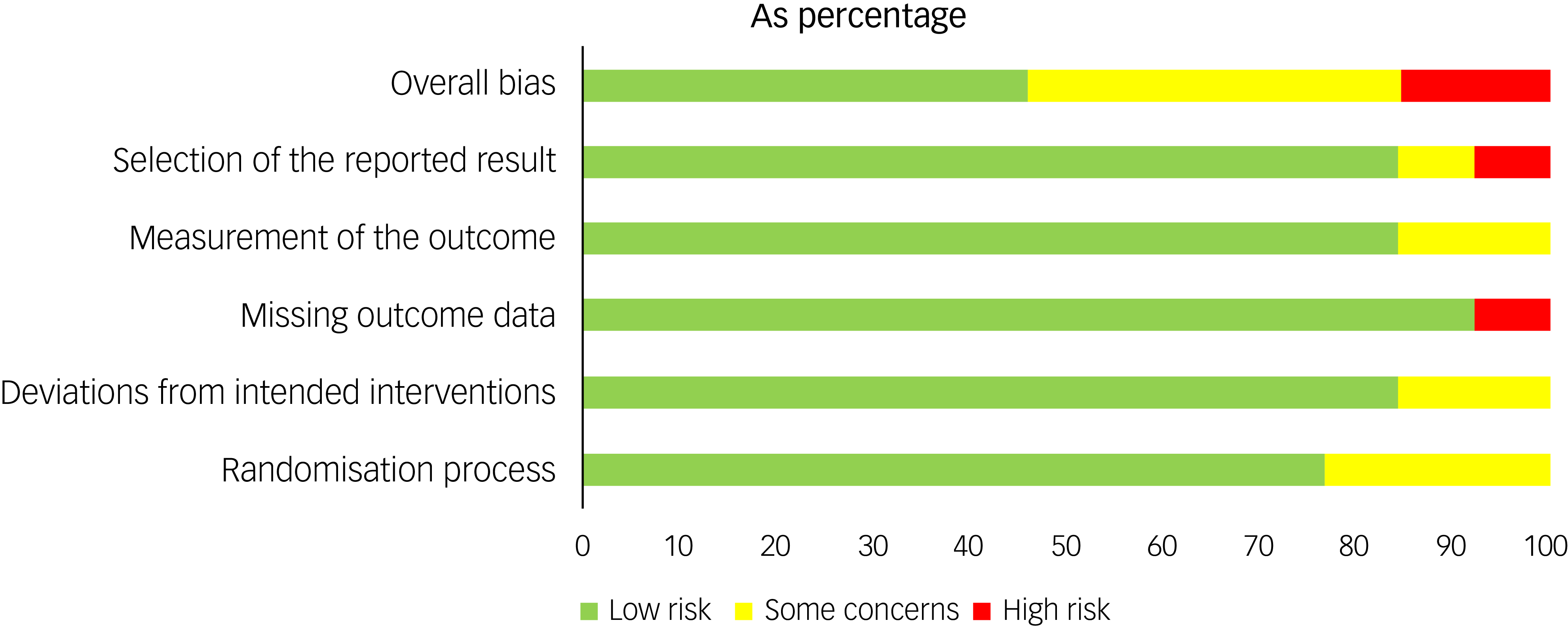

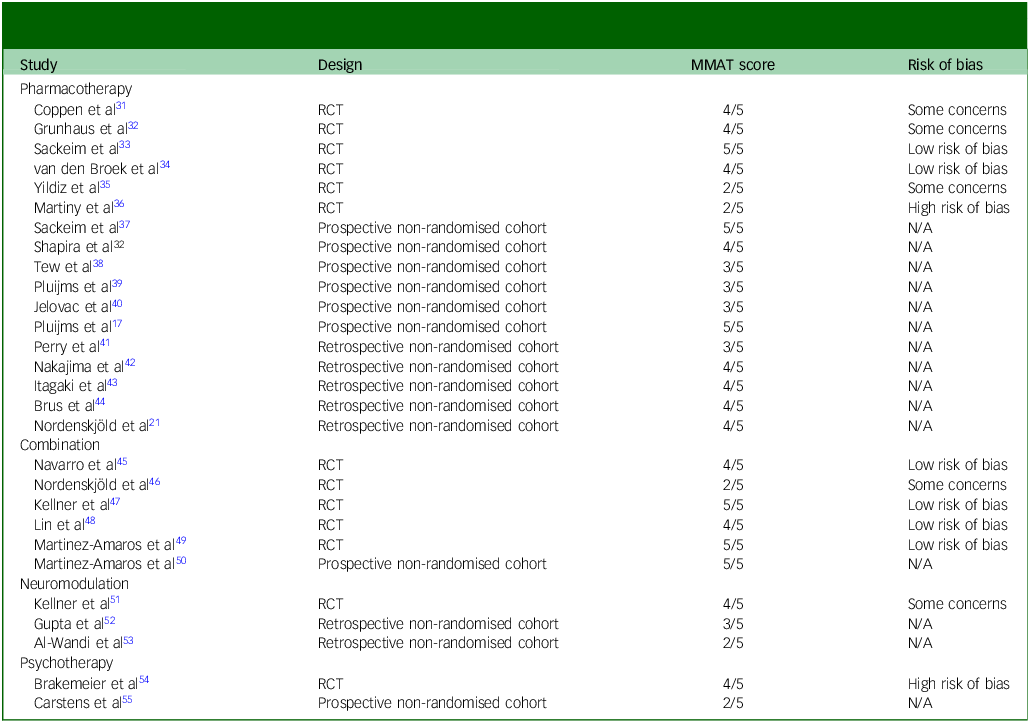

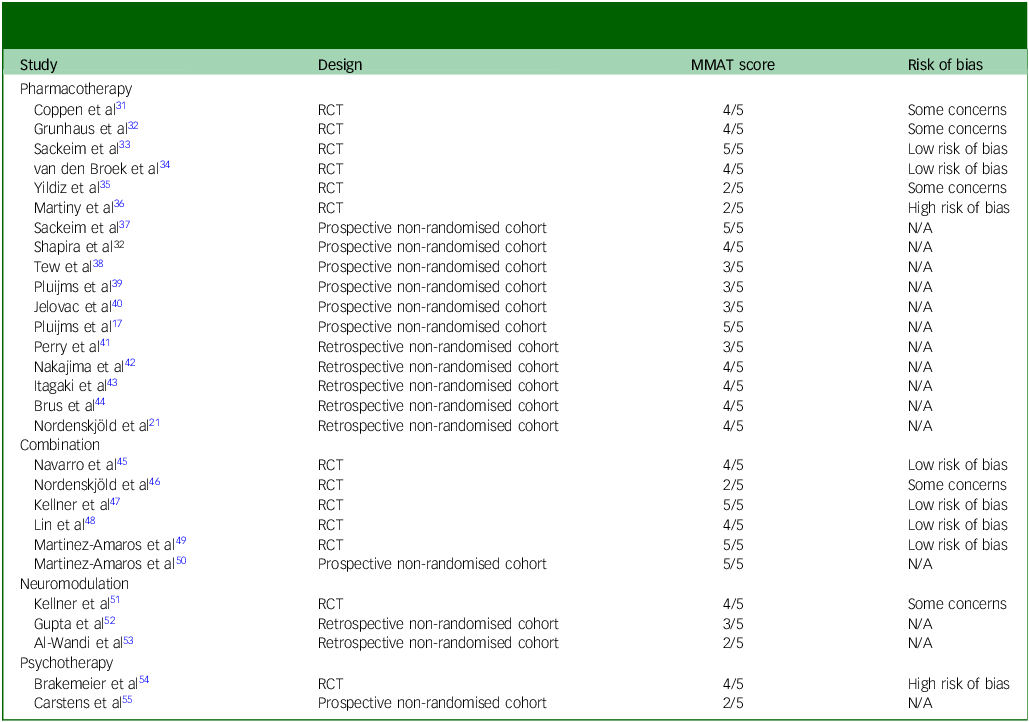

Appraisal of methodological quality

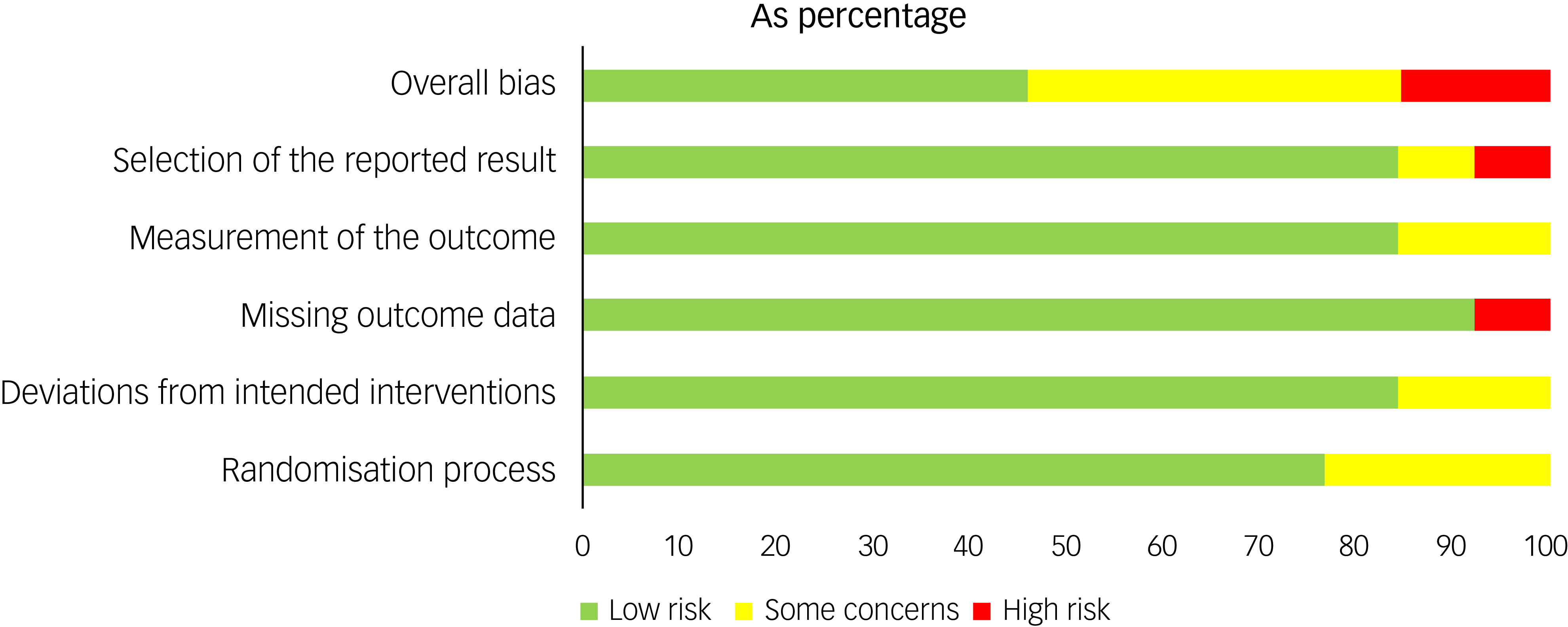

The MMAT scores varied by study and are reported in Table 4 and Supplement 4. The risk of bias assessment for the RCTs showed that 15% were at high risk for bias, 40% showed some concerns and 45% showed low risk (Figs 3 and 4).

Fig. 3 Risk of bias summary (RoB 2) for included randomised controlled trials.

Fig. 4 Risk of bias by domain (RoB 2) across included randomised controlled trials.

Table 4 Quality assessment and risk of bias in studies on relapse-prevention strategies following successful electroconvulsive therapy for major depressive disorder

MMAT, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool; RCT, randomised controlled trial; N/A, not available.

Our search of trial registries identified several relevant studies on relapse prevention following ECT that have not yet been published, including trials investigating ketamine, C-ECT and cognitive remediation (nos NCT02414932, NCT01305707 and NCT04383509). The grey literature revealed no reports of unpublished data contradicting existing literature. Although we found no evidence of large unpublished negative trials, the presence of unreported study outcomes suggests a risk of publication bias, particularly regarding novel interventions.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesised, summarised and evaluated the scientific literature on relapse-prevention strategies following a successful acute course of ECT for MDD. The findings indicate that pharmacotherapy – particularly lithium, either as monotherapy or in combination with antidepressants – has the strongest evidence base and is the most extensively studied. Combination strategies involving C-/M-ECT alongside pharmacotherapy also show promising effects in reducing relapse risk. Psychotherapy, especially CBT, appears to be a feasible and potentially beneficial adjunct, although current evidence remains limited. Novel interventions such as rTMS and ketamine have not yet been (sufficiently) studied in this context. Despite the heterogeneity and methodological limitations of the available studies, the most consistently supported relapse prevention approaches are lithium-based pharmacotherapy and combined pharmacological and C-/M-ECT strategies. There remains a clear need for more rigorous, high-quality research, particularly into novel biological treatments and the role of psychotherapy in sustaining ECT response over the long term.

Current clinical guidelines for relapse prevention in MDD typically recommend a combination of pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy and lifestyle interventions. 57,58 The main difference between relapse-prevention strategies in the general MDD population and in those patients treated with ECT lies in the severity and treatment resistance of depressive episodes. Patients who undergo ECT have often failed multiple previous treatments and tend to have more severe, chronic or psychotic forms of depression. Reference Dierckx, Heijnen, van den Broek and Birkenhäger4,Reference Jelovac, Kolshus and McLoughlin10 As such, relapse-prevention strategies in this population might need to be more intensive and at least include pharmacotherapy or M-/C-ECT. Moreover, as seen in the studies included in this review, not all patients achieved remission: a substantial proportion entered the continuation phase following response (often defined as ≥50% reduction in depressive symptoms) alone. Because responders retain residual symptoms and therefore might remain clinically depressed, relapse in the strict sense cannot occur. Instead, the clinical aim shifts towards sustaining response and supporting further improvement towards remission. Importantly, maintaining response is itself a meaningful and often realistic therapeutic goal in this severely ill, difficult-to-treat population.

While SSRIs and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are strongly recommended in general MDD guidelines for use over at least 6–12 months following remission, their efficacy in the ECT-treated population is unclear, which might be due to the high rates of medication resistance prior to ECT. Reference Rovers, Vissers, Loef, van Waarde, Verdijk and Broekman7,Reference Jelovac, Kolshus and McLoughlin10 This may diminish the utility of antidepressants as monotherapy in relapse prevention, although this hypothesis remains largely untested. By contrast, lithium has been consistently associated with a reduction in relapse risk and is the augmentation agent most studied in this context. The severity and chronicity of illness in ECT recipients further support the rationale for extended pharmacological maintenance and the use of augmentative strategies.

Psychotherapies, such as CBT and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, are frequently recommended in the general guidelines for relapse prevention. 58–Reference Zhou, Zhao, Zhu, Liu, Meng and Shao60 These therapies have been shown to significantly reduce relapse rates, especially when combined with pharmacotherapy. Reference Bockting, Schene, Spinhoven, Koeter, Wouters and Huyser61 In contrast, evidence for the use of psychotherapy in the ECT population is lacking. This might be due to the assumption that peri- and post-ECT cognitive impairment might impede the effectiveness of psychotherapies, and that the ECT population has a high level of psychotherapy resistance. Nevertheless, changes in mood-regulating areas of the brain due to ECT might create a window of opportunity for change in thinking, feeling and behaviour. Reference Bockting, Schene, Spinhoven, Koeter, Wouters and Huyser61 This window of opportunity could be harnessed to address the broad range of predisposing, precipitating and maintaining factors in MDD, including psychological and psychosocial influences that heighten the risk of relapse. Reference Burcusa and Iacono62,Reference Breedvelt, Karyotaki, Warren, Brouwer, Jermann and Hollandare63 When sufficient adaptations to psychotherapy are made, as demonstrated by Brakemeier et al, who modified CBT by increasing the structure, repetition and use of written materials to accommodate post-ECT cognitive difficulties, it may hold potential as a combined relapse prevention strategy for the ECT population. Reference Brakemeier, Merkl, Wilbertz, Quante, Regen and Bührsch54 Further research is needed to explore how strategies from the general MDD population, such as psychotherapy and lifestyle interventions, can be adapted for use in the ECT population to provide more comprehensive and sustainable relapse prevention.

Interestingly, no randomised studies have yet evaluated rTMS or (es)ketamine as relapse-prevention strategies following ECT. This is a significant gap in the literature, given the growing interest in these novel techniques. A single case series Reference Noda, Daskalakis, Ramos and Blumberger64 comprising four patients with unipolar MDD addressed the use of rTMS as a relapse prevention strategy following acute-index ECT. During the follow-up rTMS period, all 4 patients were receiving antidepressant medication and demonstrated sustained responses over a follow-up period of 6–13 months. Although anecdotal, these findings underscore the need for systematic research into novel neuromodulatory or pharmacological maintenance strategies in the post-ECT context.

Implementation barriers

Although relapse prevention is generally recommended, its implementation in clinical practice remains challenging. Access to C-/M-ECT may be limited by logistical constraints, availability and patient preferences. The potential cognitive effects of C-/M-ECT also merit consideration. While acute ECT is known to cause (most often, transient) cognitive side-effects, recent reviews found no consistent evidence of cognitive decline during C-/M-ECT, although data quality is low and results are mixed, particularly in older adults. Reference Loef, van Eijndhoven, van den Munckhof, Hoogendoorn, Manten and Spaans65–Reference van Schaik, Comijs, Sonnenberg, Beekman, Sienaert and Stek67 Evidence is particularly weak, because most studies used the Mini-Mental State Examination to assess potential cognitive decline, which is now regarded as being insufficiently sensitive. Reference Loef, van Eijndhoven, Schouws, Slooter, Janssen and Kok68 For these reasons, potential cognitive outcomes should be carefully considered, explicitly discussed with patients when C-/M-ECT is being considered and, ideally, monitored throughout the course of treatment, as also recommended during an acute course of ECT. Reference Rovers, Schönberger, Loef, van Eijndhoven, Verwijk and Somers69 Adherence to pharmacological continuation treatment and tolerability, particularly for lithium, are additional barriers. Cognitive concerns or fear of ECT may also influence long-term acceptance of ECT or hinder engagement in psychotherapy. Improving outcomes may therefore also require tackling these implementation barriers.

Strengths and limitations

The findings of this systematic review should, therefore, be interpreted in light of several other limitations of the included studies. First, the variability in relapse definitions across studies, with some relying on clinical judgement and others using standardised scales, makes it difficult to compare outcomes directly. This inconsistency could result in either over- or underestimation of relapse rates. Furthermore, many of the included studies were underpowered, as seen in trials that were prematurely terminated or involved small sample sizes. This lack of statistical power diminishes the confidence in findings, particularly in studies investigating newer therapies or combinations. Most included studies involved relatively older patient samples (mean age typically >55 years), probably reflecting the demographic profile of contemporary ECT populations, but should be taken into account when interpreting the conclusions. Another notable limitation is the lack of recent high-quality RCTs, particularly regarding novel pharmacotherapies and neuromodulation techniques. Many studies relied on retrospective data or non-randomised designs, which may have introduced biases such as selection bias or confounding variables that are not adequately controlled. Studies also differed in the timing of study entry: in most, participants were enrolled immediately after meeting response or remission criteria; some required a 1-week period of sustained remission, and one study allowed up to 3 weeks between the last ECT session and entry. Several studies did not report this variable. Such variation may affect relapse rates, because more stable patients are less prone to early symptom return. Follow-up duration also varied considerably, with some studies reporting outcomes over less than 6 months, making it difficult to assess long-term relapse risk reliably. C-/M-ECT protocols varied in frequency and tapering speed, ranging from fixed schedules to symptom-titrated approaches such as STABLE, which may have contributed to differences in relapse outcomes. Reference Kellner, Husain, Knapp, McCall, Petrides and Rudorfer47 Despite its limitations, this review provides a comprehensive overview of available relapse-prevention strategies, including a wide range of study designs. It highlights established strategies, such as lithium-based pharmacotherapy and C-/M-ECT, while also identifying underexplored areas such as psychotherapy and novel biological treatments.

In addition to the limitations of the included studies, several aspects of the review itself warrant consideration. Although we conducted a comprehensive search across multiple databases and pre-registered our protocol, the review relied on a narrative synthesis due to the heterogeneity of study designs and outcome definitions, precluding a formal meta-analysis. Another limitation concerns variation in inclusion criteria, with some studies enrolling remitters and others responders (Table 1). These divergent entry thresholds create fundamentally different clinical starting points: in responder samples, full symptom resolution has not occurred, meaning that relapse in the strict diagnostic sense cannot be established. As a result, studies may use the term ‘relapse’ to describe heterogeneous clinical phenomena, which complicates comparability across trials and limits the interpretability of reported relapse rates. Although we included both remitter (n = 12) and responder (n = 12) samples to reflect real-world ECT practice, this population heterogeneity represents a methodological constraint of both the existing literature and this review. The restriction to English- and Dutch-language publications may have led to the omission of relevant studies. Furthermore, despite dual independent screening and risk-of-bias assessment, subjective judgement cannot be fully excluded. Despite these limitations, strengths of the review include a pre-registered protocol, a comprehensive multi-database search and the inclusion of pharmacological, neuromodulatory and psychological strategies within a single synthesis, offering the most up-to-date overview currently available.

Future directions

Future research should prioritise rigorous, adequately powered trials assessing the efficacy of combined relapse-prevention strategies, especially those integrating psychotherapy with pharmacological or neuromodulatory approaches. Particular attention should be paid to adapting psychotherapies for patients recovering from ECT and exploring the timing, duration and individual tailoring of such interventions. In clinical practice, standardisation of relapse prevention through a combination of pharmacotherapy and C-/M-ECT, specifically gradual tapering of ECT following remission, could optimise long-term outcomes and minimise the risk of relapse. This approach would allow for more individualised treatment plans and better integration of ECT within the broader framework of depression management.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10946

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgement

We thank Alice Tillema, information specialist at Radboud University, for her expert advice on the development and refinement of the literature search strategy.

Author contributions

J.J.E.R., I.T., A.D. and P.F.P.v.E. designed the study, and J.J.E.R. and P.F.P.v.E. the search strategy. J.J.E.R., N.T.v.Z. and P.F.P.v.E. screened the studies and extracted data. J.J.E.R. and P.F.P.v.E. contributed to quality assessment. J.J.E.R. drafted the manuscript, and all authors critically revised it. All authors approved the final version.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Declaration of interest

None.

Transparency declaration

The lead author (J.J.E.R.) affirms that this manuscript is a transparent and accurate account of the study.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.