Introduction

The family Lecideaceae Chevall. (Chevallier Reference Chevallier1826; as ‘Lecideae’) was originally erected for all crustose genera with apothecia lacking a thalline margin but now includes only those crustose genera with simple hyaline ascospores and a Lecidea- or Porpidia-type ascus structure. Porpidioid Lecideaceae include those genera of Lecideaceae that have an ascus with an amyloid tube structure (Porpidia-type), generally halonate ascospores, and branched and anastomosing paraphyses. In contrast, lecideoid Lecideaceae have an ascus lacking an amyloid tube structure but with an amyloid apical crescent (Lecidea-type), non-halonate ascospores and ±simple paraphyses. The porpidioid Lecideaceae were previously included in the separate family Porpidiaceae Hertel & Hafellner (Hafellner Reference Hafellner1984) but Buschbom & Mueller (Reference Buschbom and Mueller2004) showed that Porpidiaceae was not monophyletic unless Lecideaceae was also included. This synonymy was confirmed by Miadlikowska et al. (Reference Miadlikowska, Kauff, Hofstetter, Fraker, Grube, Hafellner, Reeb, Hodkinson, Kukwa and Lücking2006), who also demonstrated that Lecideaceae should be removed from Lecanorales Nannf. and included in Lecanoromycetidae P. M. Kirk et al. without being assigned to an order. Schmull et al. (Reference Schmull, Miadlikowska, Pelzer, Stocker-Wörgôtter, Hofstetter, Fraker, Hodkinson, Reeb, Kukwa and Lumbsch2011) resurrected the order Lecideales Vain. within the Lecanoromycetidae for the family and this has been accepted by subsequent authors (Miadlikowska et al. Reference Miadlikowska, Kauff, Högnabba, Oliver, Molnár, Fraker, Gaya, Hafellner, Hofstetter and Gueidan2014; Lücking et al. Reference Lücking, Hodkinson and Leavitt2017; Hyde et al. Reference Hyde, Noorabadi, Thiyagaraja, He, Johnston, Wijesinghe, Armand, Biketova, Chethana and Erdoğdu2024). More recently, Ruprecht et al. (Reference Ruprecht, Fernández-Mendoza, Türk and Fryday2020) demonstrated that the majority of species of Lecidea Ach., including the type species L. fuscoatra (L.) Ach., formed a clade sibling to most porpidioid genera of the family. However, two lecideoid species, Lecidea auriculata Th. Fr. and L. tessellata Flörke, clustered with the porpidioid genera. Fryday et al. (Reference Fryday, Götz and Ruprecht2024) confirmed the anomalous position of the L. auriculata-L. tessellata group, showed that Porpidia as currently circumscribed was paraphyletic, and also recovered two porpidioid genera, Poeltiaria Hertel and Xenolecia Hertel, clustering with Lecidea. Because their tree was constructed using only two loci (nrITS and mtSSU) and the backbone was poorly supported, all porpidioid genera were retained in Lecideaceae pending further research.

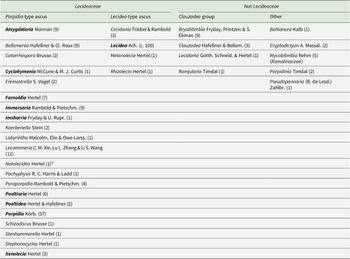

Lecideaceae as circumscribed by Lücking at al. (Reference Lücking, Hodkinson and Leavitt2017) and Hyde et al. (Reference Hyde, Noorabadi, Thiyagaraja, He, Johnston, Wijesinghe, Armand, Biketova, Chethana and Erdoğdu2024) is heterogeneous because it includes several genera that have been shown by molecular analyses to belong outside the family, whereas others have characters that make their inclusion in Lecideaceae extremely dubious (Table 1). In particular, the Clauzadea group, although having Porpidia-type asci and other characters consistent with the family (simple, hyaline ascospores with a thin perispore, a dark pigmented hypothecium, etc.), has been repeatedly recovered outside Lecideaceae in molecular analyses (e.g. Schmull et al. Reference Schmull, Miadlikowska, Pelzer, Stocker-Wörgôtter, Hofstetter, Fraker, Hodkinson, Reeb, Kukwa and Lumbsch2011; Kantvilas et al. Reference Kantvilas, Wedin and Svensson2021). The systematic position of this group is currently unclear and it would be better placed as Lecanoromycetidae incertae sedis.

Table 1. Genera included in Lecideaceae by Lücking et al. (Reference Lücking, Hodkinson and Leavitt2017) and/or Hyde et al. (Reference Hyde, Noorabadi, Thiyagaraja, He, Johnston, Wijesinghe, Armand, Biketova, Chethana and Erdoğdu2024). Those in the ‘Not Lecideaceae’ columns are genera that have subsequently been shown to belong in other families or have morphological characters inconsistent with the family. Numbers in parentheses are the reported number of species in that genus. Genera in bold are included in the current study.

* Notolecidea was considered to be a synonym of Poeltiaria by Fryday & Hertel (Reference Fryday and Hertel2014) and was not included in Lecideaceae by either Lücking et al. (Reference Lücking, Hodkinson and Leavitt2017) or Hyde et al. (Reference Hyde, Noorabadi, Thiyagaraja, He, Johnston, Wijesinghe, Armand, Biketova, Chethana and Erdoğdu2024) but is most probably a distinct genus.

Lecideaceae has been widely studied in the Northern Hemisphere (e.g. Hertel Reference Hertel1975, Reference Hertel1977a, Reference Hertelb , Reference Hertel1981, Reference Hertel1991, Reference Hertel1995, Reference Hertel2009; Inoue Reference Inoue1982, Reference Inoue1983; Brodo & Hertel Reference Brodo and Hertel1987; Gowan Reference Gowan1989; Gowan & Ahti Reference Gowan and Ahti1993; Andreev et al. Reference Andreev, Kotlov and Makarova1998; Buschbom & Mueller Reference Buschbom and Mueller2004; Hertel & Printzen Reference Hertel, Printzen, Nash, Ryan, Diederich, Gries and Bungartz2004; Fryday Reference Fryday2005; Schmull et al. Reference Schmull, Miadlikowska, Pelzer, Stocker-Wörgôtter, Hofstetter, Fraker, Hodkinson, Reeb, Kukwa and Lumbsch2011), but less so in the Southern Hemisphere (e.g. Hertel Reference Hertel1984, Reference Hertel1997, Reference Hertel2007; Rambold Reference Rambold1989; Inoue Reference Inoue1991; Ruprecht et al. Reference Ruprecht, Lumbsch, Brunauer, Green and Türk2010, Reference Ruprecht, Fernández-Mendoza, Türk and Fryday2020; Fryday & Hertel Reference Fryday and Hertel2014; Fryday et al. Reference Fryday, Götz and Ruprecht2024). Lecideoid (including porpidioid) lichens were revised in Australia by Rambold (Reference Rambold1989) but the island of Tasmania was specifically excluded from that study.

The current paper is concerned solely with porpidioid Lecideaceae found in Tasmania. Fieldwork there by the last author over a period of four decades has assembled an extensive array of porpidioid Lecideaceae collections representative of most of Tasmania’s major habitats. Previously, the first author has described Poeltiaria tasmanica Fryday (Fryday & Hertel Reference Fryday and Hertel2014) from these collections. Here we propose two genera as new to science: one for P. tasmanica and a newly described species, the other for a single, newly described species. We also describe a new species of Poeltiaria and a new species and variety of Porpidia, report Porpidia albocaerulescens var. polycarpiza (Vain.) Hertel & Rambold and P. hydrophila (Fr.) Hertel & A. J. Schwab as new to Tasmania, and confirm the presence of P. umbonifera (Müll. Arg.) Rambold on the island. However, a large number of collections still require critical examination and further additions to the porpidioid lichen biota of the island are confidently predicted.

Materials and Methods

Site description

The diversity of lichen habitats in Tasmania belies its relatively small size of just 68 400 km2. The island has a complex geology and rugged topography, with steep ecological gradients and sharp vegetation boundaries, some strongly influenced by fire. As well as being a fragment of the former supercontinent of Gondwana, it is also the southernmost extremity of a more or less continuous land mass (at least in geological time) that extends from the tropics southward to cool temperate latitudes in the Southern Ocean. These factors contribute to Tasmania supporting a truly remarkable lichen biota, of which the crustose lecideoid lichens form a significant component. Whereas porpidioid lichens occur throughout all vegetation formations, they tend to be particularly diverse at high elevations. These taxa form the focus of the present study.

Morphological methods

Gross morphology was examined under a dissecting microscope, and apothecial characteristics by light microscopy (compound microscope) on hand-cut sections mounted in water, 10% KOH (K), 50% HNO3 (N) or Lugol’s reagent (1.5% aqueous solution; IKI). Thallus sections were investigated in water, commercial bleach (C), K, N and concentrated Lugol’s reagent (6% aqueous solution; IKIconc). The presence of light-refractive crystals was detected using polarized light (POL). Ascospore measurements of the new taxa were measured in water and are given as (minimum value–)mean ± standard deviation(–maximum value), with ‘n’ indicating the number of ascospores measured. Thallus chemistry was investigated by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) following the methods of Orange et al. (Reference Orange, James and White2001).

Molecular methods

Taxon sampling

The new genera and species were phylogenetically distinguished by adding sequences from other species of porpidioid Lecideaceae where these were available for at least two of the three loci used in the analysis (nrITS, mtSSU and RPB1). These were species of the genera Amygdalaria, Cyclohymenia, Farnoldia, Imsharria, Lecidea, Poeltiaria, Poeltidea, Porpidia and Xenolecia. Unfortunately, for some ‘porpidioid’ genera sequences from only one locus were available (e.g. Stenhammarella, Schizodiscus), whereas for others, no relevant sequences were available (e.g. Notolecidea and Pachyphysis, for which only nrLSU and β-tubulin were available). We tried including these single sequences in our analysis but this had a significant negative effect on the support values of the phylogeny and so they were removed for the final analysis. Although suitable sequences from the genera Eremastrella and Lecaimmeria were available, they were not included in our analysis (see ‘Discussion’ for justification). All genera, with the exception of Poeltiaria and Porpidia (see below), were represented by their type species. The analysis further augmented that of Fryday et al. (Reference Fryday, Götz and Ruprecht2024) by adding the marker RPB1 and the taxa Immersaria athroocarpa (Ach.) Rambold & Pietschm., Lecidea terrena Nyl., Lecidea sp. (Falkland Islands), Porpidia albocaerulescens var. polycarpiza, P. umbonifera var. umbonifera, cf. Stephanocyclos sp. and the new species described below.

The phylogeny was rooted with an Antarctic collection of Carbonea vorticosa (Flörke) Hertel as an outgroup. Ideally, a species from a genus outside of Lecideaceae but within Lecideales would have been chosen as outgroup but the only other family included in Lecideales by Lücking et al. (Reference Lücking, Hodkinson and Leavitt2017) and Hyde et al. (Reference Hyde, Noorabadi, Thiyagaraja, He, Johnston, Wijesinghe, Armand, Biketova, Chethana and Erdoğdu2024) is Lopadiaceae Hafellner, which includes the single genus Lopadium Körb. However, sequences from all three of the markers we used were not available for a single collection of this genus and so we chose a representative from Lecanorales, Carbonea vorticosa, because sequences from all three markers were available.

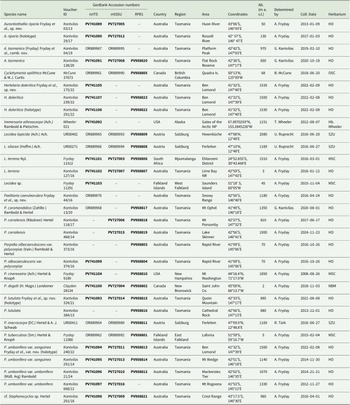

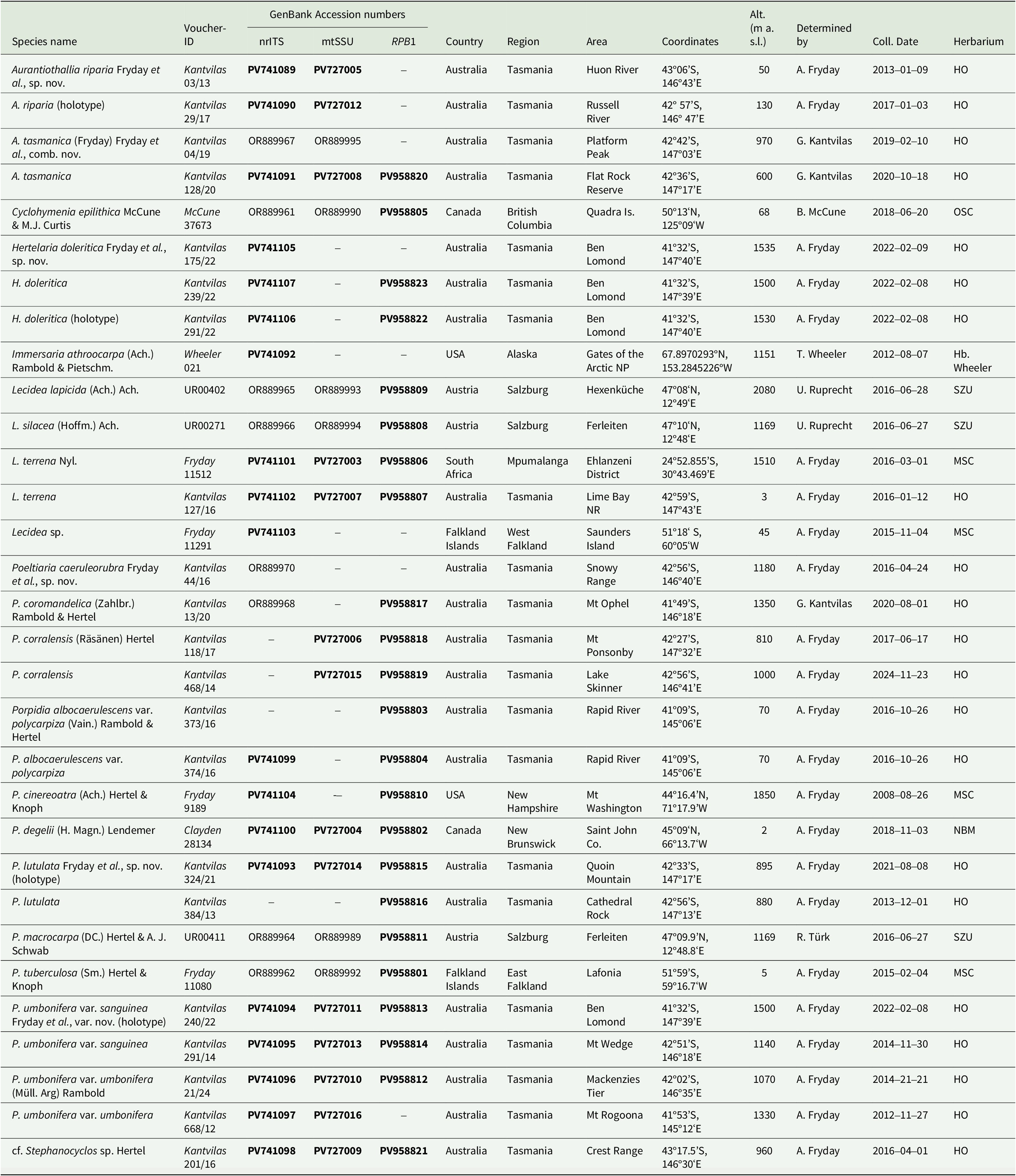

Details of collections for which new sequences were obtained are given in Table 2, whereas sequences downloaded from GenBank are provided in Supplementary Material Table S1 (available online).

Table 2. Voucher information of taxa in Lecideaceae for the markers nrITS, mtSSU and RPB1 that were newly generated for this study or previously published under a different name. Sequences of Aurantiothallia tasmanica (Kantvilas 04/19) and Poeltiaria caeruleorubra (Kantvilas 44/16) are also included because these were previously published under different species names, Poeltiaria tasmanica and Poeltiaria sp. respectively, by Fryday et al. (Reference Fryday, Götz and Ruprecht2024).

DNA-amplification, sequencing and phylogenetic analyses

Total DNA was extracted from individual thalli using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Lichen material (c. 2–4 mm2) was scraped off with a sterilized scalpel from the centre of the thallus, with apothecia included.

The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the mycobionts’ nuclear ribosomal DNA (nrITS), the mitochondrial small subunit (mtSSU) and the large subunit of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II (RPB1) were amplified and sequenced using the following primers: ITS1F (Gardes & Bruns Reference Gardes and Bruns1993), ITS1 and ITS4 (White et al. Reference White, Bruns, Lee, Taylor, Innis, Gelfand, Sninsky and White1990) for ITS; CU6 (https://nature.berkeley.edu/brunslab/tour/primers.html), mrSSU1 (Zoller et al. Reference Zoller, Scheidegger and Sperisen1999), mtSSU for2 and mtSSU rev2 (Ruprecht et al. Reference Ruprecht, Lumbsch, Brunauer, Green and Türk2010) for mtSSU; fRPB1-C rev, gRPB1-A for (Matheny et al. Reference Matheny, Liu, Ammirati and Hall2002) and RPB1_for_Lec (Ruprecht et al. Reference Ruprecht, Fernández-Mendoza, Türk and Fryday2020) for RPB1. PCR conditions followed Ruprecht et al. (Reference Ruprecht, Fernández-Mendoza, Türk and Fryday2020). The unpurified PCR products were sent to Eurofins Genomics, Germany, for sequencing.

The sequences of the three regions were edited using Geneious Pro v. 6.1.8 (www.geneious.com) and separately aligned with MAFFT v. 7.017 (Katoh et al. Reference Katoh, Misawa, Kuma and Miyata2002) using preset settings (algorithm, auto select, scoring matrix, 200PAM/k = 2; gap open penalty, 1.34–0.123) on the most recent available alignments used by Ruprecht et al. (Reference Ruprecht, Fernández-Mendoza, Türk and Fryday2020) and Fryday et al. (Reference Fryday, Götz and Ruprecht2024). The final data matrix of the phylogeny comprised 72 concatenated sequences of the markers ITS (68 sequences, 573 characters), mtSSU (47 seq., 821 char.) and RPB1 (41 seq., 790 char.), with a total length of 2184 characters. The single ITS, mtSSU and RPB1 trees were visually checked for incongruency using a bootstrap value of > 85%.

The maximum likelihood analysis (ML) was performed using the IQ-TREE web server (Trifinopoulos et al. Reference Trifinopoulos, Nguyen, von Haeseler and Minh2016) with default settings (ultrafast bootstrap analyses (Hoang et al. Reference Hoang, Chermomor, von Haeseler, Minh and Vinh2018), 10 000 BT alignments, 1000 max. iterations, min. correlation coefficient: 0.99, SH-aLRT branch test with 1000 replicates). The analysis was performed with three partitions (Chernomor et al. Reference Chernomor, von Haeseler and Minh2016) and the best-fit models for the single trees were selected with the implemented model finder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al. Reference Kalyaanamoorthy, Minh, Wong, von Haeseler and Jermiin2017) of the program IQ-TREE: TIM2 + F + I + G4 (for ITS), HKY + F + I + G4 (mtSSU) and TIM2e + I + G4 (RPB1). Bayesian phylogenies were inferred using the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) procedure as implemented in the program MrBayes v. 3.2. (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck Reference Ronquist and Huelsenbeck2003). The analysis was also performed in three partitions assuming the general time reversible model of nucleotide substitution, including estimation of invariant sites and a discrete gamma distribution with six rate categories (GTR + I + Γ; Rodriguez et al. Reference Rodriguez, Oliver, Marin and Medina1990) for each partition. We applied the GTR + I + G model, which is the most general time-reversible substitution model and encompasses all simpler reversible models. In a Bayesian framework, the use of GTR + I + G is generally recommended, as priors help mitigate overparameterization. Two runs with 7 million generations (average standard deviation of split frequencies: 0.00374), each starting with a random tree and employing four simultaneous chains, were executed. Every 1000th tree was saved into a file. Subsequently, the first 25% of trees was deleted as the ‘burn-in’ of the chain. A majority-rule consensus tree with posterior probabilities for each clade was calculated from the remaining 10 502 post-burn-in trees (5251 per run).

Both phylogenies were visualized with the program FigTree v. 1.4.3 (Rambaut Reference Rambaut2014).

Results

Phylogenetic analyses

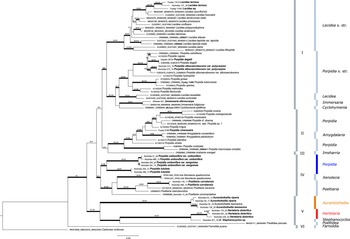

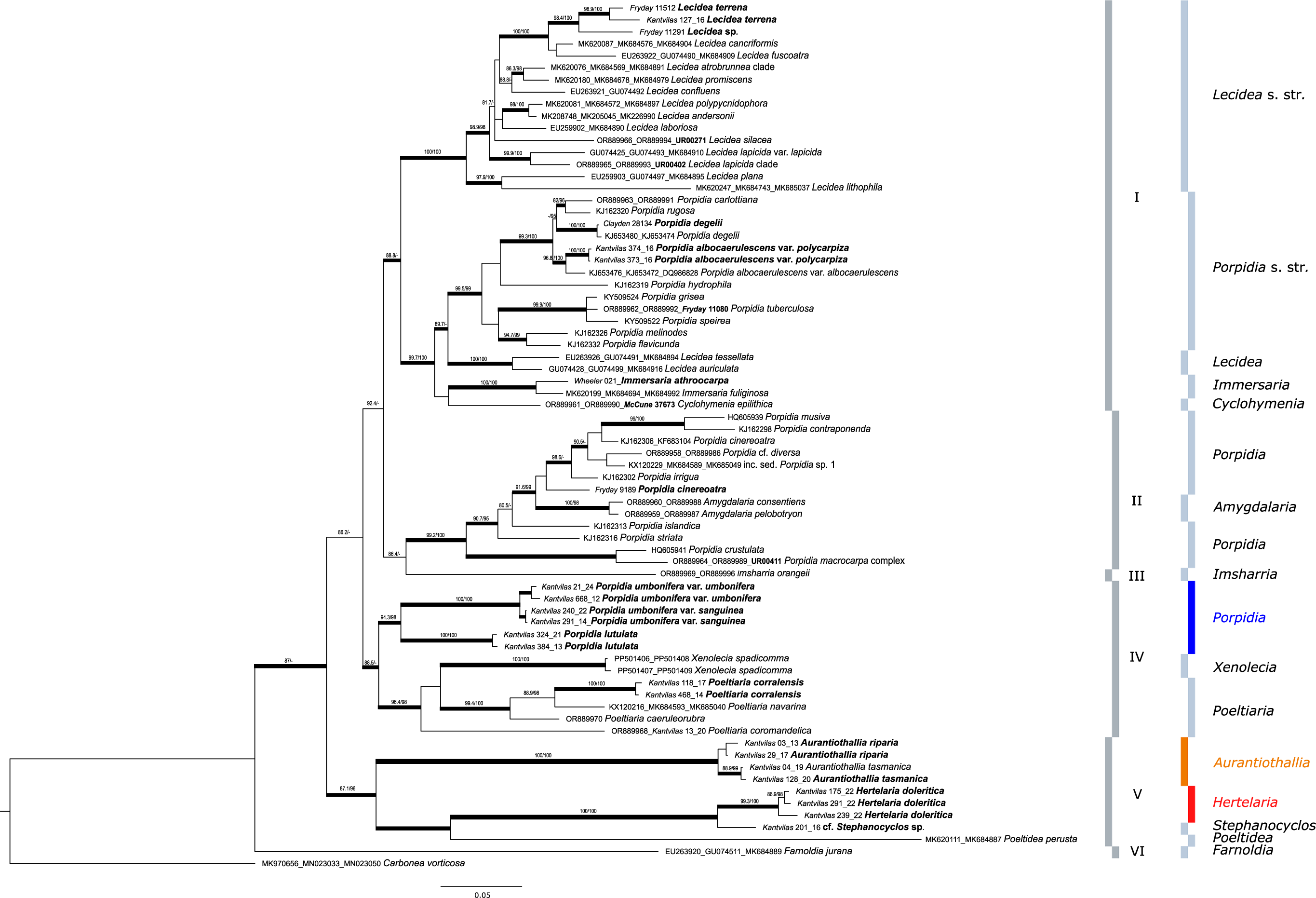

The resulting phylogenetic tree is shown in Fig. 1. The phylogeny consists of six strongly supported main clades. Clade I is further subdivided into two, highly supported subclades. The first consists of the genus Lecidea, including the newly added Southern Hemisphere species L. terrena and a hitherto unnamed Lecidea species from the Falkland Islands that are sibling to the type species L. fuscoatra and L. cancriformis C. W. Dodge & G. E. Baker. The second consists of species of Porpidia s. str. that are sibling to Lecidea auriculata and L. tessellata, with these in turn being sibling to Cyclohymenia epilithica McCune & M. J. Curtis and Immersaria fuliginosa Fryday, and the newly added type species I. athroocarpa. The former subclade includes the newly added variety Porpidia albocaerulescens var. polycarpiza that is clearly distinguished from P. albocaerulescens var. albocaerulescens (Wulfen) Hertel & Knoph.

Figure 1. Phylogeny of concatenated ITS, mtSSU and RPB1 sequences including the genera Amygdalaria, Cyclohymenia, Farnoldia, Immersaria, Imsharria, Lecidea, Poeltiaria, Poeltidea and Porpidia (Lecideaceae), with the newly described species Porpidia umbonifera and P. lutulata indicated in blue. The newly described genera Aurantiothallia and Hertelaria appear in orange and red respectively. Voucher numbers in bold are from specimens of previous studies with additional sequences provided in the present study. Bootstrap values (ML analyses: SH-aLRT ≥ 80%/UFboot ≥ 95%) were directly mapped on the Bayesian tree with ≤ 0.95 support posterior probability values (branches in bold). In colour online.

Clade II comprises the heterogeneous group of Porpidia s. lat., including the P. macrocarpa (DC.) Hertel & A. J. Schwab and P. cinereoatra (Ach.) Hertel & Knoph groups, along with two species of the genus Amygdalaria that includes the type species, A. pelobotryon (Ach.) Hertel & Brodo.

Clades III, IV and V are composed exclusively of Southern Hemisphere genera. Clade III is represented by a single accession, Imsharria orangei Fryday & U. Rupr. Clade IV consists of two varieties of the species Porpidia umbonifera (var. umbonifera and the newly described var. sanguinea Fryday et al.) and the newly described P. lutulata Fryday et al. These two species form a strongly supported subclade sibling to the one containing the genera Xenolecia, represented by the type species X. spadicomma (Nyl.) Hertel, and Poeltiaria, including the newly described Poeltiaria caeruleorubra Fryday et al.

Clade V is formed by the two newly described, Southern Hemisphere genera, Aurantiothallia Fryday et al. and Hertelaria Fryday et al., the species cf. Stephanocyclos sp. and Poeltidea, with Poeltidea sibling to cf. Stephanocyclos sp. and Hertelaria, which are in turn sibling to Aurantiothallia

Clade VI is formed by the genus Farnoldia, represented by the type species F. jurana (Schaer.) Hertel.

Taxonomy

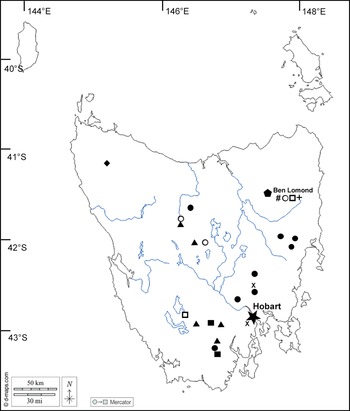

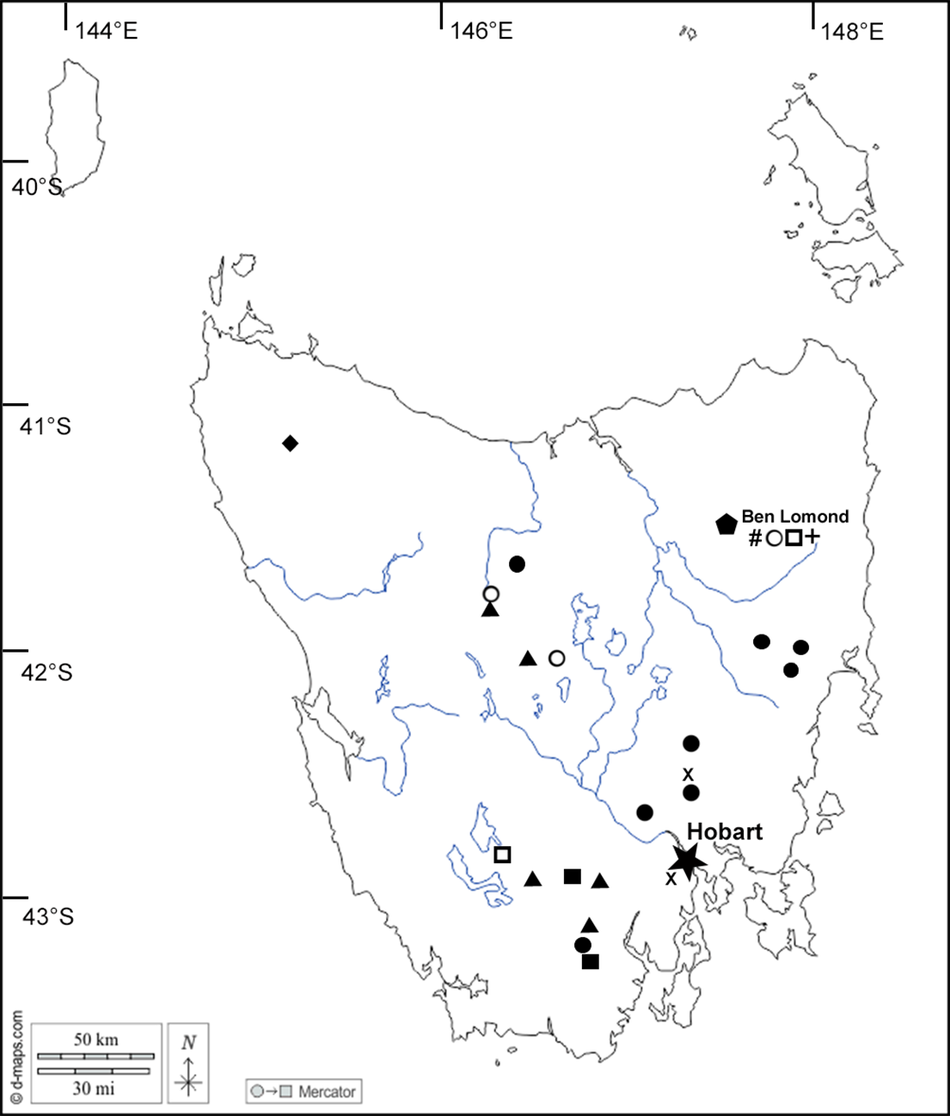

The morphological and molecular investigations indicate the presence of several novel taxa. These are described below and their known distributions are mapped in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Map of Tasmania showing location of taxa featured in this paper. Aurantiothallia riparia (![]() ), Aurantiothallia tasmanica (

), Aurantiothallia tasmanica (![]() ), Hertelaria doleritica (

), Hertelaria doleritica (![]() ), Poeltiaria caeruleorubra (

), Poeltiaria caeruleorubra (![]() ), Porpidia lutulata (

), Porpidia lutulata (![]() ), Porpidia umbonifera var. sanguinea (

), Porpidia umbonifera var. sanguinea (![]() ), Porpidia albocaerulescens var. polycarpiza (

), Porpidia albocaerulescens var. polycarpiza (![]() ), Porpidia hydrophila (#), Porpidia umbonifera var. umbonifera (

), Porpidia hydrophila (#), Porpidia umbonifera var. umbonifera (![]() ). In colour online.

). In colour online.

Aurantiothallia Fryday, U. Rupr. & Kantvilas gen. nov

MycoBank No.: MB 861061

Distinguished from other porpidioid genera of Lecideaceae by its orange thallus lacking secondary lichen compounds but with an amyloid (I+ violet) medulla, black apothecia with only brown pigments internally, and by its distinct, isolated phylogenetic position (ITS, mtSSU and RPB1).

Type species: Aurantiothallia tasmanica (Fryday) Fryday, U. Rupr. & Kantvilas

Etymology

The generic name is composed arbitrarily from the Latin aurantius (= orange), and the Greek θάλλος (thállos), and alludes to the orange thallus of both known species.

Aurantiothallia riparia Fryday, U. Rupr. & Kantvilas sp. nov

MycoBank No.: MB 861066

Similar to A. tasmanica but with ±orbicular (not angular) apothecia that have a smoother disc and a much less well-developed proper exciple, and with longer conidia, 11–17 μm (5–8.5 μm long in A. tasmanica); further separated by its molecular sequence data.

Type: Australia, Tasmania, Russell River at bridge on Russell Road, 42°57′S, 146°47′E, 130 m, on rocks along riverbank (probably occasionally inundated), 3 January 2017, G. Kantvilas 29/17 (HO 585692—holotype).

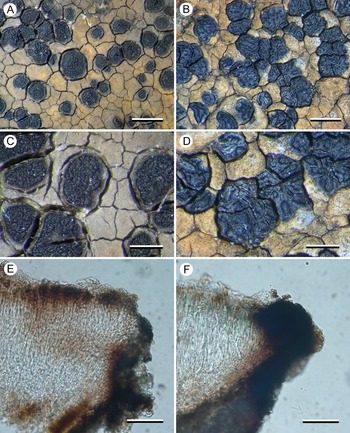

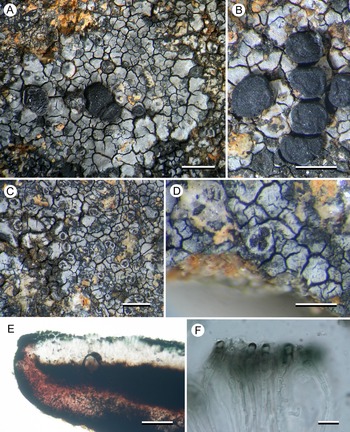

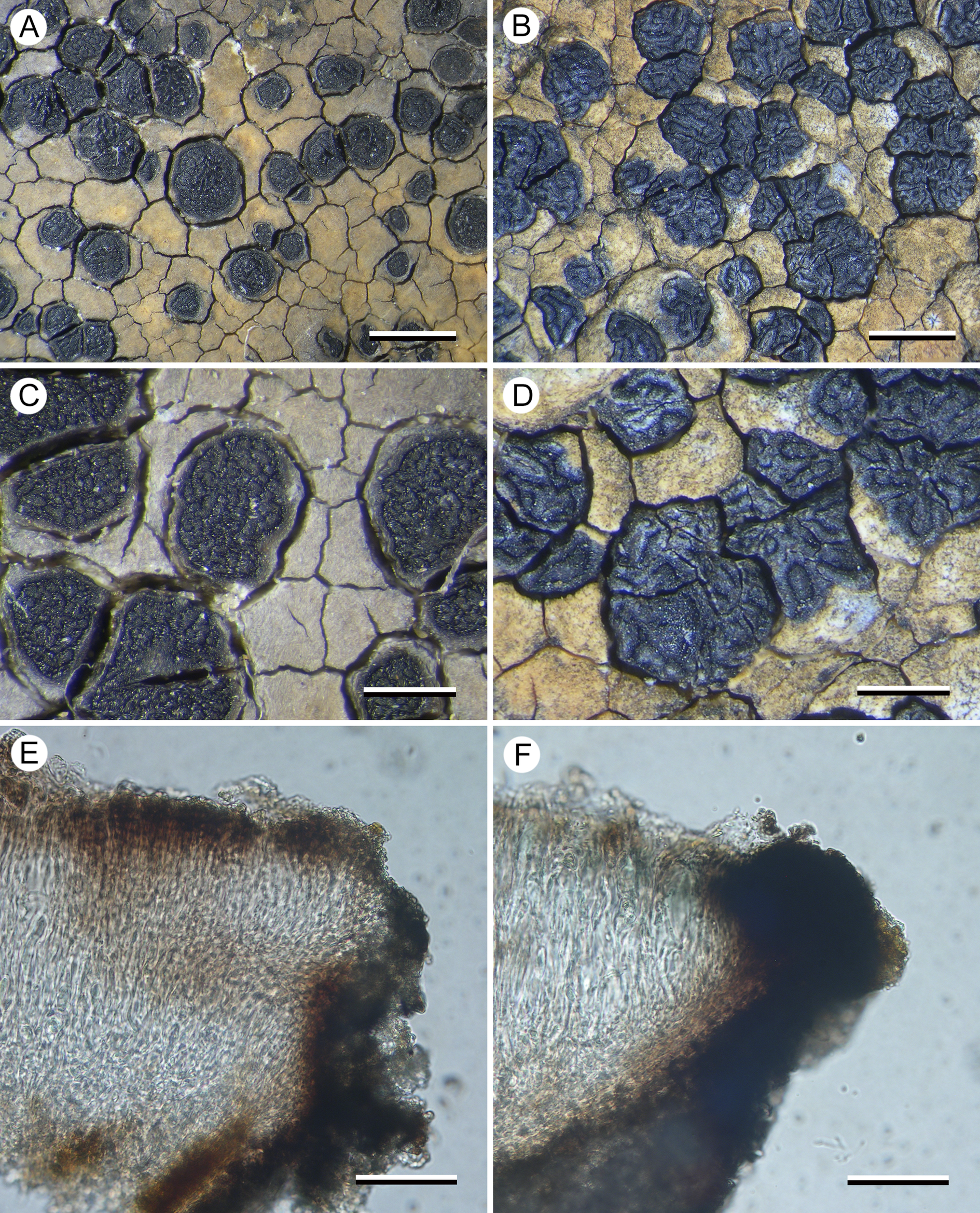

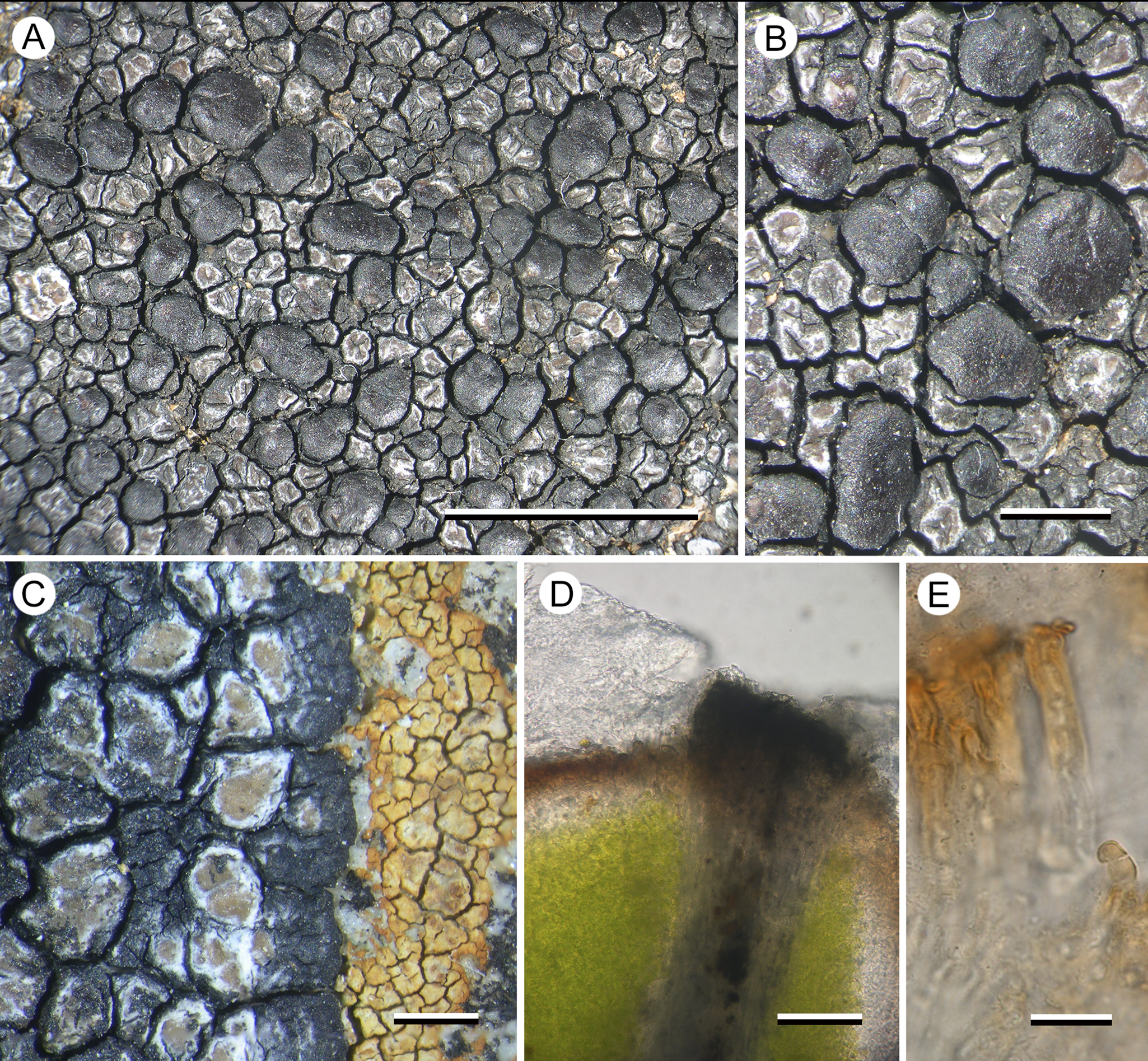

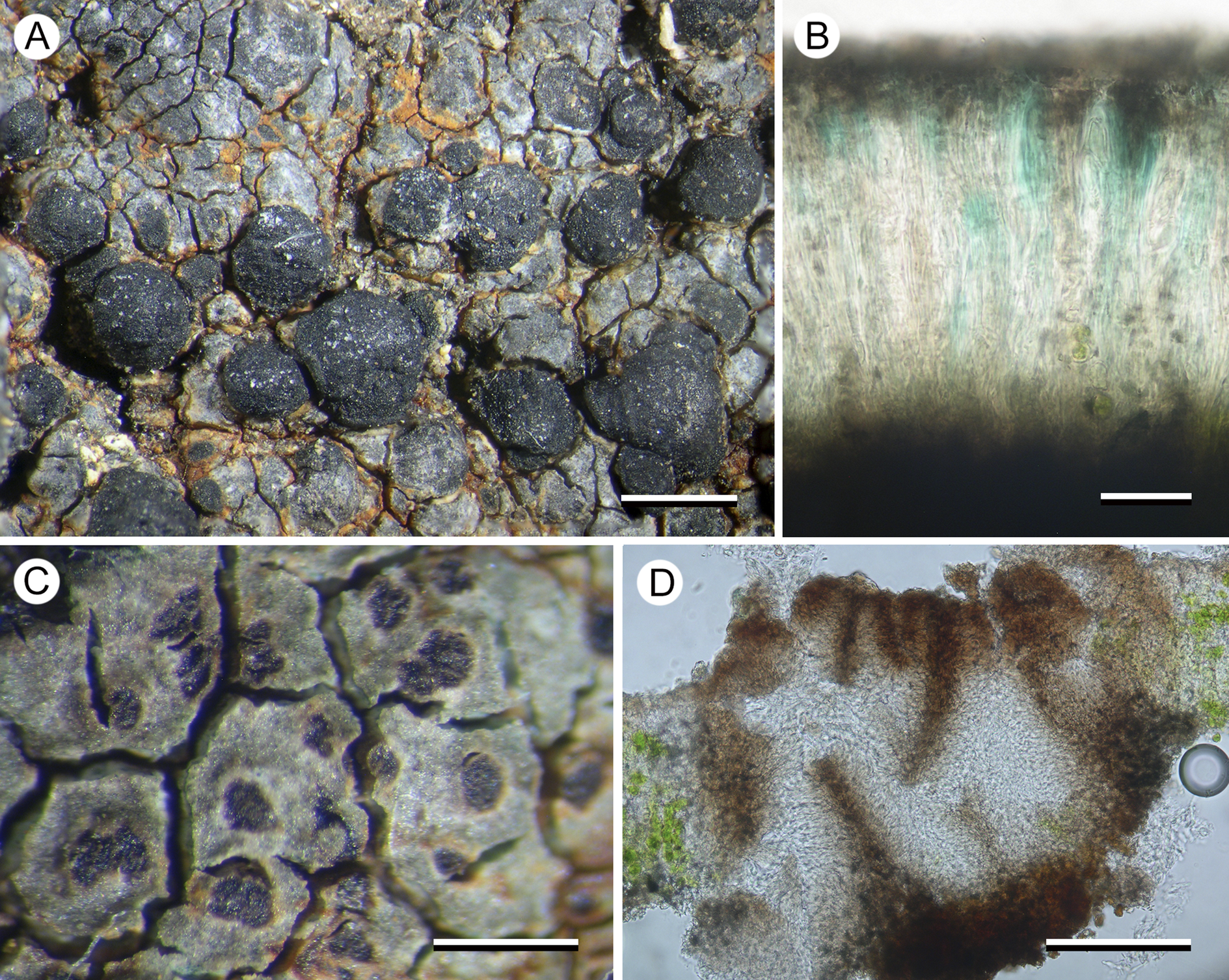

(Fig. 3)

Figure 3. Comparison between Aurantiothallia riparia (A, C & E, Kantvilas 29/17) and A. tasmanica (B, D & F, Kantvilas 4/19). A & B, thallus with apothecia. C & D, apothecia. E & F, section of proper exciple. Scales: A & B = 1.0 mm; C & D = 0.5 mm; E & F = 25 μm. In colour online.

Thallus widespreading up to 5 cm or more across, distinctly marginate, creamy yellow to orange but often with grey patches that sometimes dominate, 0.3–0.8 mm thick, smooth to rimose-areolate; areoles plane to slightly convex, rhomboid, 0.4–1.2 mm across; prothallus only visible when in contact with other lichen species and then thin (0.05–0.1 mm) and black, when adjoining another thallus of the same species apparent only in section. In section: with a thin, poorly differentiated, orange-brown cortical layer 10–15 μm thick, composed of the upper cells of vertically aligned hyphae c. 5 μm wide, elsewhere hyaline and inspersed with numerous crystals, mostly < 10 μm across but sometimes to 30 × 20 μm, unchanged in K but becoming brighter in N and finally dissolving, POL+, overlain by a very thin (up to 2 μm thick) epinecral layer of hyaline cells, and subtended by a thin hyaline layer (5–15 μm thick; IKIconc+ violet); photobiont layer 150–200 μm thick, interrupted by narrow bands of hyaline hyphae 20–25 μm wide; photobiont chlorococcoid, with cells thin-walled, 8–12 μm diam.; medulla 100–150 μm thick, hyaline above, becoming pale brown where in contact with the substratum, IKIconc+ violet, with the violet colour extending in columns up through the photobiont layer, indicating that the latter is interrupted by medullary tissue.

Apothecia lecideine, black even when wet, plane to slightly concave when young, ±immersed in the thallus, ±orbicular (0.4–)0.6–0.8(–1.0) mm diam.; disc smooth when young, becoming lumpy when mature; proper margin thin (0.05 mm wide), dark grey to black, slightly raised. In section: proper exciple annular, very poorly developed and often barely discernible, 5–10 μm wide, composed of very pale brown to hyaline, rhomboid cells c. 5 μm across, but with c. 50 μm of adjoining thallus overlain by a dark chestnut brown extension of the epihymenium. Hymenium 80–120 μm thick; paraphyses strongly conglutinated even in K and N, septate, sparingly branched and anastomosing, 1.5–3.0 μm thick, slightly widening to 3–4 μm in the upper 25 μm, the apical cell with a narrow, brown-pigmented cap or hood; epihymenium 10–15 μm thick, pale chestnut brown (K−, N−), but often with thicker (40–50 μm), darker brown areas 75–80 μm wide that sometimes extend down through the hymenium to the hypothecium and correspond to the ‘lumps’ on the surface of the disc; subhymenium hyaline, 10–25 μm thick, composed of randomly aligned hyphae, POL−; hymenium, subhymenium and hypothecium merging into one another so it is often unclear where one ends and the other begins. Asci rarely well developed, Porpidia-type, cylindrical, c. 60 × 15 μm; ascospores simple, hyaline, (12–)14.7 ± 1.87(–20) × (5–)6.1 ± 0.89(–8) μm, l/w ratio (1.86–)2.44 ± 0.43(–3.40) (n = 20); perispore sometimes apparent, usually thin, rarely up to 5 μm thick. Hypothecium chestnut brown, pale brown above, darker below, 100–150 μm thick but often with a deep ‘root’ extending down to the base of the thallus, composed of randomly aligned hyphae, POL−.

Conidiomata abundant, most often in lines along the edge of adjoining thalli but also scattered over the thallus surface, ±immersed, elongate to fleck-like, glossy red-brown with the adjacent thallus white, 0.06–0.15 × 0.02–0.05 mm (excluding white border); conidia straight, shortly filiform, c. 11–17 × 1 μm.

Chemistry

All spot tests negative. No substances detected by TLC.

Etymology

The specific epithet is the feminine adjective derived from the Latin noun ripa (= riverbank) meaning ‘of riverbanks’ and referring to the habitat of the species.

Remarks

The new species closely resembles A. tasmanica, with which it shares a mostly orange thallus lacking lichen substances, black, often immersed apothecia, only brown apothecial pigments, an amyloid medulla and similar-sized ascospores. Species of Xenolecia also share many of these characters but differ in having a generally paler, cream-coloured thallus that contains lichen substances (e.g. confluentic acid, norstictic acid), apothecia with a smooth disc that becomes brown when wet, and generally larger ascospores. We considered the possibility that A. riparia and A. tasmanica are conspecific and that some of the morphological differences, notably the thicker thallus, angular apothecia with a markedly thicker proper exciple, and the markedly lumpy-gyrose apothecial disc in A. tasmanica, are related to habitat ecology. Thus, whereas A. riparia tends to grow on semi-inundated rocks in streams, often submerged in fast-flowing water, A. tasmanica occurs on rock plates that are, at most, subject to shallow water-seepage, dependent on intermittent, seasonal conditions. However, we recognize the two taxa as distinct, not only because of molecular results but also due to the consistent difference in conidial size: whereas those of A. riparia are 11–17 μm long, those of A. tasmanica are only 5–8.5 μm. We also doubt that the difference in apothecial shape and the more irregularly contorted disc of A. tasmanica are environmentally induced.

In the field, A. riparia can be distinguished from A. tasmanica by its orbicular apothecia with a smoother disc and less pronounced proper margin. Microscopically, in addition to the conidia, it differs in having a much less well-developed proper exciple (c. 50 μm wide in A. tasmanica), and a usually more intensely pigmented hypothecium (hyaline but filled with minute crystals and appearing grey in A. tasmanica).

The new species is mostly found on semi-inundated dolerite rocks in fast-flowing streams and rivers, although one collection is from alpine limestone. The orange thalli of both Aurantiothallia species often have grey patches that when viewed in microscopic section can be seen to correspond to areas in which the pale orange-brown cortical cells have a thin covering of hyaline cells. It is unclear whether these cells are necrotic thallus material or some kind of pruina, but it is perhaps significant that the single collection of A. riparia from alpine limestone is completely grey.

Aurantiothallia riparia and A. tasmanica form a genus-level group near the base of our phylogeny, where they cluster together with the new genus Hertelaria, Poeltidea (another Southern Hemisphere genus), and an apparently undescribed species treated here as cf. Stephanocyclos sp. They are clearly separated from the other sequenced species of Poeltiaria. Unfortunately, fresh material of the type species of Poeltiaria, P. turgescens (Körb.) Hertel, was not available for this study but P. turgescens morphologically resembles the Poeltiaria species in Clade IV (Fig. 1) and so we are convinced that this clade represents Poeltiaria s. str. Although molecular data are not available for several other genera of porpidioid Lecideaceae, notes on these genera detailing how they differ from Aurantiothallia are included in the ‘Discussion’ section below. Consequently, we have no hesitation in erecting a new genus for the P. tasmanica group.

Additional specimens examined (paratypes)

Australia: Tasmania: Dunnys Creek, 42°13′S, 146°24′E, 640 m, 1984, G. Kantvilas 472/94 & P. W. James (HO 598575); Downie Plains, c. 0.5 km E of Double Lagoon, 41°53′S, 146°34′E, 1160 m, 2005, G. Kantvilas 161/05 (HO 532038); Arve River above the Falls, 43°13′S, 146°46′E, 770 m, 2007, G. Kantvilas 284/07 (HO 544937); Clarke Falls, 41°55′S, 146°11′E, 930 m, 2012, G. Kantvilas 639/12 (HO567849); Huon River below confluence with Picton River, 43°06′S, 146°43′E, 50 m, 2013, G. Kantvilas 3/13 (HO 48601); Gowan Brae, Nive River, 42°02′S, 146°25′E, 810 m, 2014, G. Kantvilas 110/14 (HO572348); North-East Ridge, Mt Anne, at the western rim of the Annakananda sinkhole, 42°55′57.2″S, 146°26′29.3″E, 1050 m, 2016, G. Kantvilas 99/16 (HO 583168).

Aurantiothallia tasmanica (Fryday) Fryday, U. Rupr. & Kantvilas comb. nov

MycoBank No.: MB 861063

Poeltiaria tasmanica Fryday, in Fryday & Hertel, Lichenologist 46, 396 (2014); type: Australia, Tasmania, Bisdee Tier, 42°26′S, 147°17′E, 640 m, on moist dolerite seepage rocks in rough pasture, 17 June 2009, G. Kantvilas 302/09 (HO—holotype!; MSC—isotype!).

(Fig. 3)

Remarks

This species was reported by Fryday & Hertel (Reference Fryday and Hertel2014) from the type collection only, but subsequent fieldwork has shown it to be widespread on moist dolerite rocks on the island. It also occurs on scattered pebbles on flat, exposed summits.

The apothecia of A. tasmanica somewhat resemble those of Stephanocyclos henssenianus Hertel but that species has a grey thallus with a non-amyloid medulla (I−) and sessile apothecia with a more exposed disc and an olivaceous epihymenium.

Additional collections examined

Australia: Tasmania: Lost Falls Reserve, 42°03′S, 147°53′E, 540 m, 2015, G. Kantvilas 273/15 (HO); Little Swanport River, 42°20′S, 147°53′E, 10 m, 1993, G. Kantvilas 38/93 (HO); Platform Peak, c. 0.5 km S of summit, 42°42′S, 147°03′E, 970 m, 2019, G. Kantvilas 4/19 (HO 595955); Flat Rock Reserve, Eastern Lookout, 42°36′S, 147°17′E, 600 m, 2020, G Kantvilas 182/20 (HO 601357); Western Lookout, 42°36′S, 147°17′E, 500 m, 2021, G. Kantvilas 205/21 (HO 603945); Mike Howes Lookout, 42°15′S, 117°15′E, 740 m, 2022, G. Kantvilas 508/22 (HO); M-Road, 42°08′S, 147°52′E, 540 m, 2023, G. Kantvilas 277/23 (HO); Lake Perry, 43°12′S, 146°45′E, 920 m, 2025, G. Kantvilas 44/25 (HO); eastern slopes of Turrana Heights, 41°45′35″S, 146°23′24″E, 1290 m, 2025, G. Kantvilas 29/25 (HO); Hobgoblin summit, 42°02′S, 147°44′E, 769 m, 2025, G. Kantvilas 65/95 (HO).

Hertelaria Fryday, U. Rupr. & Kantvilas gen. nov

MycoBank No.: MB 861062

Distinguished from other porpidioid genera of Lecideaceae by its atrobrunnea-type thallus, hyaline hypothecium, large, shallowly convex, red-brown apothecia, and by its distinct, isolated phylogenetic position (ITS and RPB1).

Type species: Hertelaria doleritica Fryday, U. Rupr. & Kantvilas.

Etymology

The new genus honours Prof. Dr Hannes Hertel for his lifetime’s dedication to elucidating and describing the systematic diversity of lecideoid lichens, especially the numerous new genera he erected for Southern Hemisphere species groups in Lecideaceae. The suffix ‘aria’ is derived from the morphological resemblance of the type species to the genus Immersaria.

Hertelaria doleritica Fryday, U. Rupr. & Kantvilas sp. nov

MycoBank No.: MB 861068

See generic diagnosis.

Type: Australia, Tasmania, Ben Lomond, c. 750 m SE of Giblin Peak, 41°32′S, 147°40′E, 1530 m, on alpine dolerite boulders, 8 February 2022, G. Kantvilas 291/22 (HO 607772—holotype; MSC—isotype).

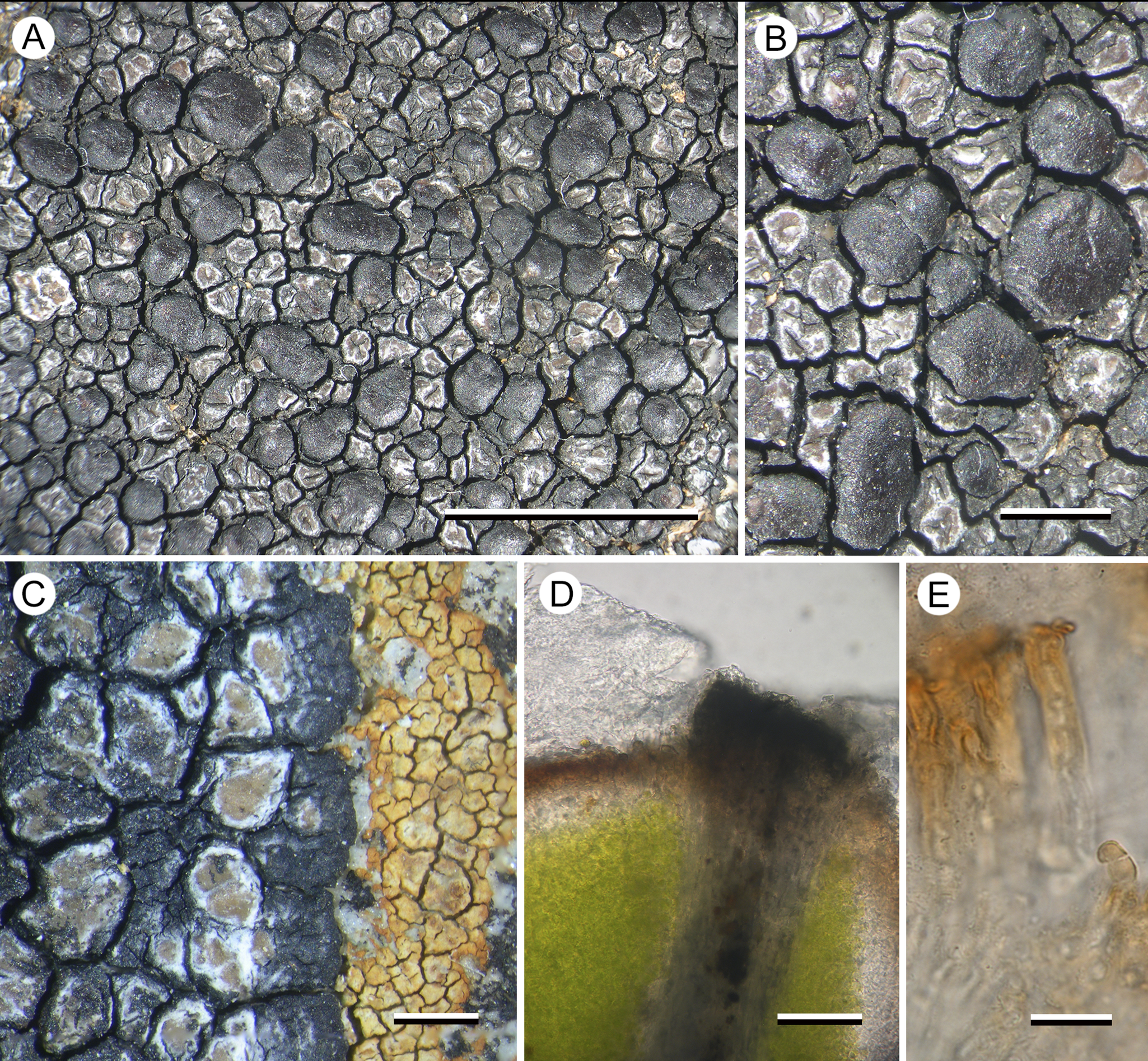

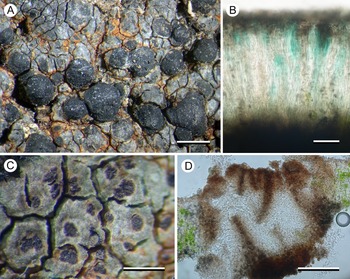

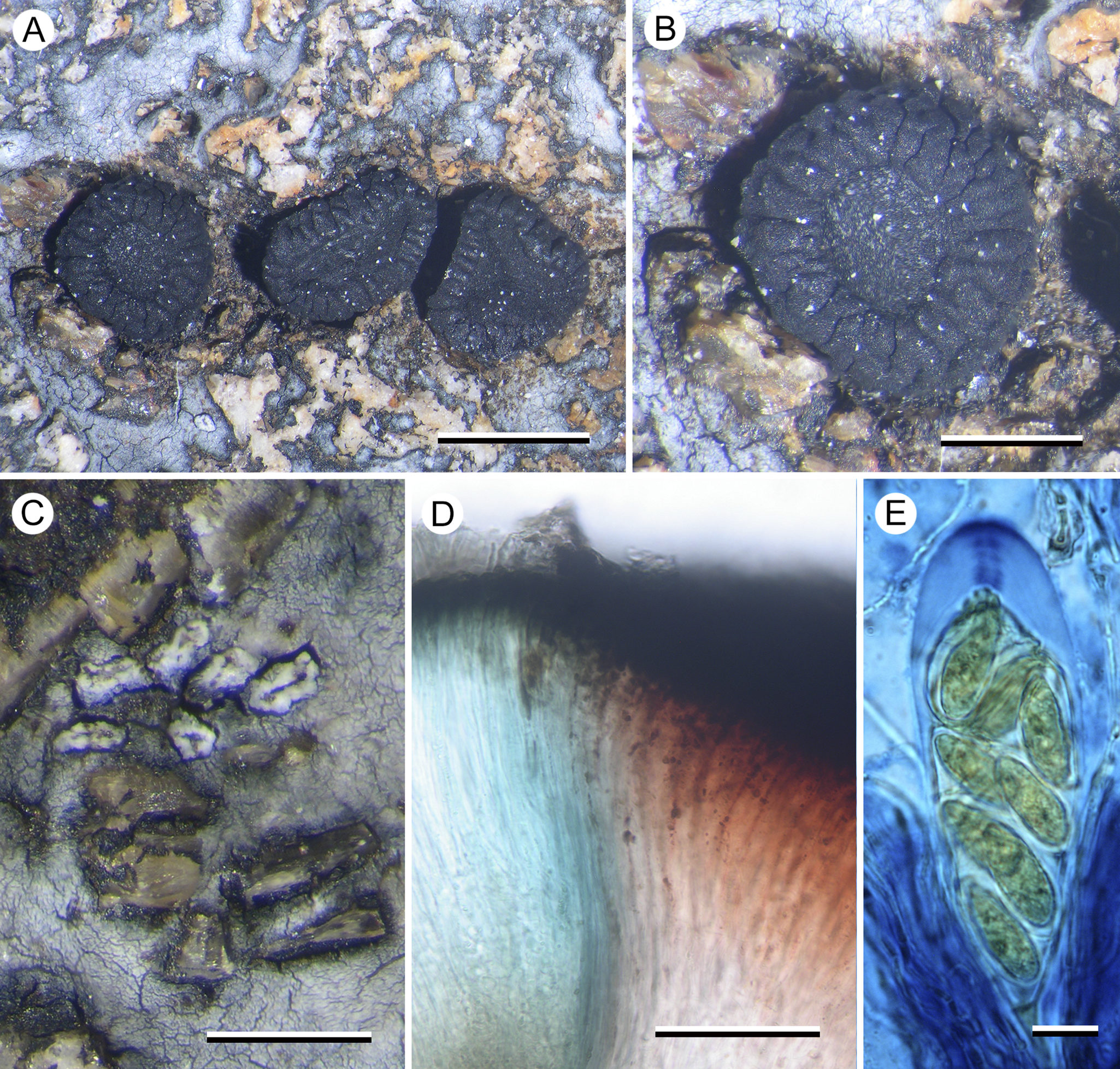

(Fig. 4)

Figure 4. Hertelaria doleritica (A & B, Kantvilas 238/22; C, Kantvilas 291/22—holotype; D & E, Kantvilas 491/21). A, thallus with apothecia. B, apothecia. C, thallus edge showing black prothallus and Hymenelia gyalectoidea. D, thallus section showing thick epinecral layer (upper left) and dark areole edge (center). E, paraphyses showing thick gelatinous coat. Scales: A = 5.0 mm; B & C = 1.0 mm; D = 25 μm; E = 10 μm. In colour online.

Thallus widespreading, to 10–15 cm across, often dying away at the centre, atrobrunnea-type, with a black, delimiting, marginal prothallus 0.6–0.8 mm wide; marginal areoles ±orbicular to angular, 0.4–1.2 mm across, ±contiguous on the prothallus, concave to plane, glossy, pale brown with a thick whitish margin that often becomes dominant and thus gives the thallus margin a distinctly paler coloration than the rest of the thallus; areoles elsewhere darker, reddish brown and often with black-sided slits and cracks, separated by narrow cracks, with the black prothallus becoming more prominent and also forming the walls of the areoles, adding to the overall darker coloration of more central areas of the thallus. In section: epinecral layer 40–45(–70) μm thick in young areoles, c. 25 μm in older central ones, composed of periclinal hyphae; upper cortex consisting of two layers of columns of rhomboidal cells c. 5 μm wide, an upper brown-pigmented layer 10–15 μm thick with surface cells rounded, 3–5 μm wide with a darker brown cap, and a lower hyaline layer 10–50 μm thick; areole walls 30–40 μm wide, greyish, but black at the surface with cells c. 5 μm diam. (K+ blue-black), lower part POL+, surface and rest of areole except medulla POL−; photobiont layer 100–120 μm thick, ±continuous, with individual cells 5–7(–9) μm diam., filled with numerous aplanospores; medulla hyaline but filled with minute crystals and appearing grey (POL+), >150 μm thick, I−.

Apothecia numerous, lecideine, chestnut brown, glossy, adnate to sessile, not constricted basally, flat to slightly convex, typically orbicular, 0.8–1.6 mm diam., but with larger apothecia sometimes becoming elongated and up to 2.4 mm long; proper margin usually not apparent but, when visible, thin, slightly raised and darker than the disc. In section: proper exciple dark red-brown, c. 60–100 μm wide, upper edge K+ blue-black, composed of radiating short-celled, branched and anastomosing hyphae 4–6 μm thick, hyaline in the inner part and brown-pigmented and slightly expanded to 5–7 μm towards the outer edge. Hymenium 85–100 μm thick; paraphyses simple, 3–4 μm wide, apical cells 5–7 μm wide; epihymenium red-brown, 20–50 μm thick. Asci Porpidia-type, 50–60 × 15–20 μm; ascospores simple, hyaline, without a distinct perispore, (15–)16.6 ± 2.0(–21) × (6.5–)7.5 ± 0.8(–9.0) μm, l/w ratio (1.9–)2.2 ± 0.3(–2.6) (n = 20). Hypothecium hyaline, 150–175 μm thick, composed of ±vertically aligned hyphae 3–4 μm thick, (POL−), at the base subtended by loosely arranged ascogenous hyphae c. 5 μm wide arranged in groups c. 50 across, 50–70 μm thick and interspersed with narrow ±hyaline/pale brown bands of hyphae derived from the exciple (POL+).

Conidiomata not observed.

Chemistry

All spot tests negative. TLC (solvent C) indicated faint spots consistent with stictic acid in all five specimens tested and norstictic acid in two. Mass spectrometry, however, detected only ‘possible analogs of muronic acid in low concentrations’ (E. Lacey, personal communication).

Etymology

The specific epithet is derived from ‘dolerite’, the Jurassic-age rock type that dominates the eastern and central parts of Tasmania, and which is the substratum for all known collections of the species.

Distribution and ecology

The new species is known only from the summit plateau of Ben Lomond in north-eastern Tasmania, a region representing the largest, continuous extent of land over 1500 m elevation on the island. It occurs on dolerite boulders and outcrops and is part of a highly diverse lichen association, particularly rich in crustose lichens. Some of its associates include Aspicilia epiglypta (Norrl. ex Nyl.) Hue, Buellia bogongensis Elix, Calvitimela armeniaca (DC.) Hafellner, Cameronia pertusarioides Kantvilas, Carbonea vorticosa, Frutidella caesioatra (Schaer.) Kalb, Hymenelia gyalectoidea Kantvilas, Immersaria athroocarpa, Lambiella psephota (Tuck.) Hertel, Lecanora demersa (Kremp.) Hertel & Rambold, L. marginata (Schaer.) Hertel & Rambold, Lecidea lygomma Nyl., Schaereria australis Kantvilas, S. fuscocinerea (Nyl.) Clauzade & Cl. Roux and Tremolecia atrata (Ach.) Hertel. The Tasmanian distribution of several of these species is likewise limited to the Ben Lomond Plateau. Whereas a large number of the species cited above occur as tiny thalli within a complex mosaic of species, and can therefore be easily overlooked, Hertelaria doleritica occurs in extensive patches and is easily recognized. As well as occurring on the tops of boulders, it can also colonize vertical rock faces where it is sometimes the sole lichen present. All the collections of H. doleritica are associated with the orange thallus of Hymenelia gyalectoidea and it is possible that the new species is initially lichenicolous on that species.

Remarks

The new lichen is characterized by a glossy, pale brown areolate thallus and large, chestnut brown, slightly convex, lecideine apothecia. In thin section, the cortical cells can be seen to be overlain by a thick epinecral layer of dead hyaline cells (atrobrunnea-type). The atrobrunnea-type thallus gives this species a superficial resemblance to a species of Immersaria or Poeltidea, but the apothecia of both of these genera are black and immersed in the thallus.

The photobiont cells of H. doleritica are 5–7(–9) μm diam., filled with numerous aplanospores, and are, therefore, considerably smaller than those of most species of the family. We obtained photobiont sequences from three collections: Trebouxia sp. A02. from Kantvilas 175/22, Vulcanochloris aff. canariensis (96–97% similarity) from Kantvilas 291/22 (holotype), and both the above species from Kantvilas 239/22, but it is unclear if the primary photobiont is either of these species. Vulcanochloris was described by Vančurová et al. (Reference Vančurová, Peksa, Němcová and Škaloud2015) who recognized three species that had cells 18–21 μm diam.

Systematic position

In our phylogeny, Hertelaria doleritica resolves in a clade with another Tasmanian collection that resembles Stephanocyclos henssenianus except that its apothecia are initially ±orbicular and the thallus has an amyloid (I+ violet) medulla. These two species are sibling to two collections of Poeltidea perusta (Nyl.) Hertel & Hafellner from southern South America, which are all sibling to Aurantiothallia. Hertelaria doleritica resembles P. perusta in having an atrobrunnea-type thallus but differs from that genus in the emergent red-brown apothecia (black and innate in P. perusta) and the smaller, hyaline ascospores (24–36 ×11–18 μm and pigmented in P. perusta). It is difficult to perceive any morphological similarities between Hertelaria and either Stephanocyclos Hertel or Aurantiothallia. Hertelaria has a thick brown atrobunnea-type thallus with ±innate, flat to slightly convex apothecia with a thin, barely apparent thalline margin, whereas the thalli of both Stephanocyclos and Aurantiothallia are not atrobunnea-type, and the apothecia are black, with a prominent, cracked ±carbonaceous proper margin. The differences between Aurantiothallia and Stephanocyclos are discussed above under the former genus.

Additional specimens examined (paratypes)

Australia: Tasmania: Ben Lomond, Stacks Bluff, 41°38′S, 147°41′E, 1510 m, 1996, G. Kantvilas 104/96 (HO); ibid., Plains of Heaven, 41°32′S, 147°39′E, 1500 m, 2021, G. Kantvilas 491/21 (HO 605812); ibid., 2022, G. Kantvilas 239/22 (HO 607448); ibid., Legges Tor, 41°32′S, 147°39′E, 1560 m, 2022, G. Kantvilas 110/21 (HO 606806); ibid., Stonjek’s Lookout, 41°32′S, 147°40′E, 1535 m, 2022, G. Kantvilas 175/22 (HO 607099); ibid., unnamed summit, c. 500 m S of Little Hell, 41°32′S, 147°40′E, 1530 m, 2022, G. Kantvilas 554/22 (HO 611727).

Poeltiaria caeruleorubra Fryday, U. Rupr. & Kantvilas sp. nov

MycoBank No.: MB 861070

Distinguished from other species of the genus by the thin, silver-grey thallus, the large sessile apothecia with a thick, radially striate proper margin, and the red pigment in the inner exciple.

Type: Australia, Tasmania, Hartz Mtns NP, summit of small knoll overlooking Emily Tarn, 43°15′S, 146°46′E, 1070 m, on alpine dolerite boulders, January 2019, G. Kantvilas 11/19 (HO 595962—holotype).

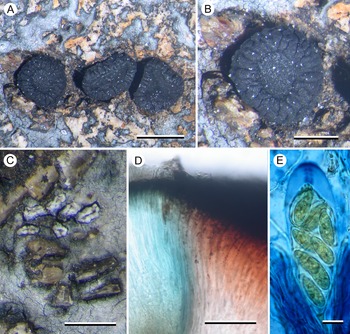

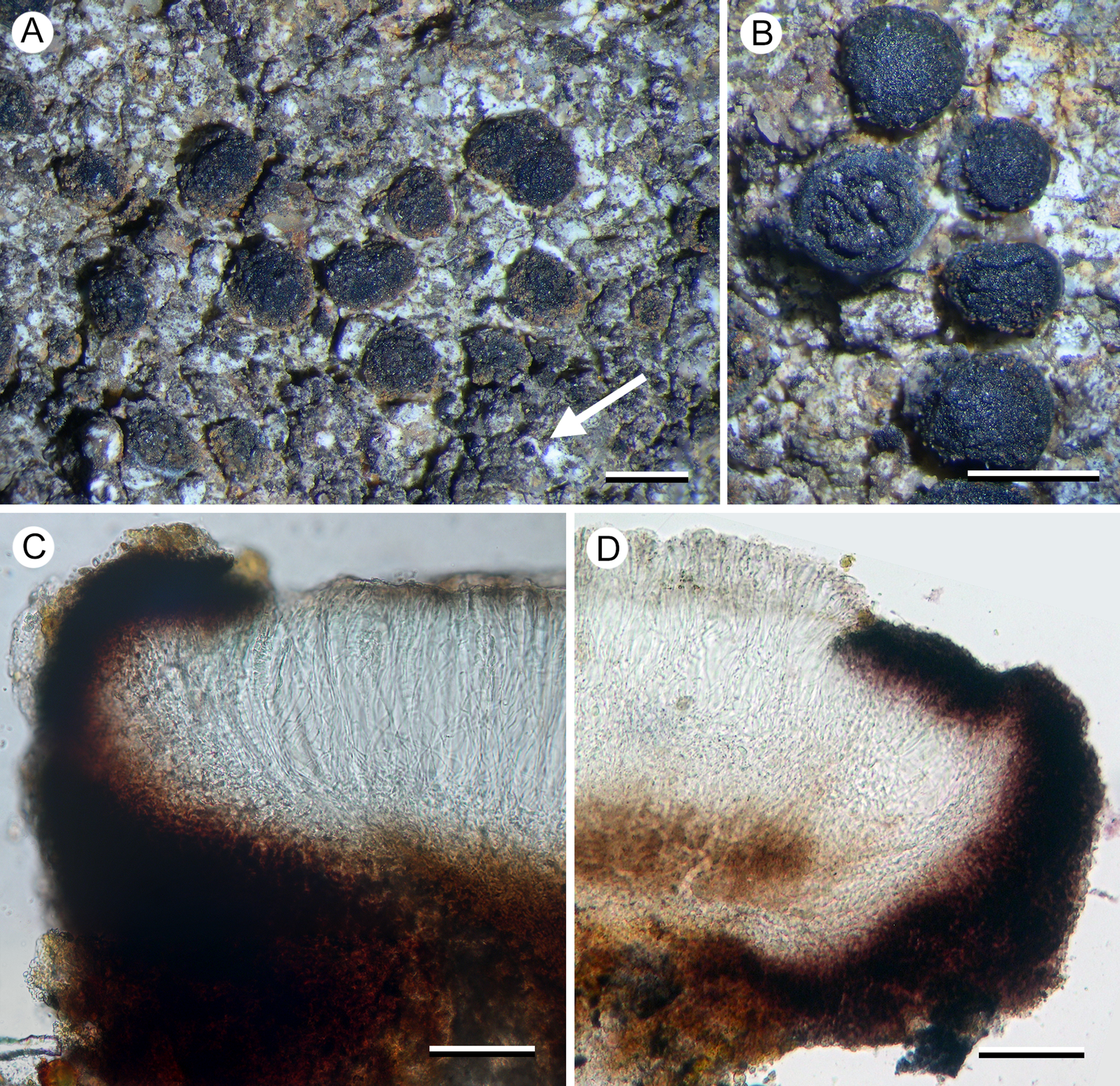

(Fig. 5)

Figure 5. Poeltiaria caeruleorubra (A, B & C, Kantvilas 44/16 D & E, Kantvilas 11/19—holotype). A, thallus with apothecia. B, apothecium. C, lirellate conidiomata with raised white border. D, interface of hymenium (left) and exciple (right) showing abrupt pigmentation change. E, ascus and ascospores in 6% IKI. Scales: A = 1.0 mm; B & C = 0.5 mm; D = 50 μm; E = 10 μm. In colour online.

Thallus effuse, silver-grey, continuous to cracked-rimose, mostly in small patches filling in the gaps between the rock granules of the dolerite substratum, usually very thin but becoming thicker (0.1–0.15 mm) in deeper gaps. In section: upper cortex poorly differentiated, c. 10 μm thick, grey (K−, N+ brown), composed of vertically aligned hyphae c. 2–3 μm thick, coated with a grey pigment (K−, N+ brown), swelling at the surface to 4–5 μm wide with a darker grey cap (K−, N+ brown), overlain by an epinecral layer up to 5 μm thick, and subtended by a hyaline layer 50–60 μm thick, composed of a mixture of hyphae and rhomboid cells c. 10 μm across; photobiont layer c. 100 μm thick, interspersed with narrow bands of medullary tissue; photobiont cells 6–12 μm diam., with a hyaline wall and containing numerous aplanospores; medulla very thin or absent, I−; all parts POL+, especially the photobiont layer, but all becoming POL− in K.

Apothecia lecideine, black, scattered, rarely in small groups of 2–3, plane with a thick but barely raised proper margin, strongly constricted at the base, orbicular except where compressed by the structure of the rock, 1.2–2.0(–3.0) mm diam.; disc plane; proper margin c. 0.3 mm wide, with shallow, radial striations, becoming excluded in larger apothecia. In section: proper exciple massive, c. 600 μm wide, extending under the hymenium, composed of radiating hyphae 3–4 μm thick; cortex carbonaceous, 35–50 μm thick, cracked at the outer margin, together with the adjacent medulla strongly red-pigmented (K−, N−), progressively less pigmented inwards and becoming hyaline adjacent to the hypothecium. Hymenium c. 150 μm thick, mostly hyaline but blue-pigmented (K−, N+ red; Cinereorufa-green) adjacent to the exciple; epihymenium 25 μm thick, dark olivaceous (K−, N+ brownish red); paraphyses extremely slender, c. 1 μm wide, ±simple, slightly swollen to 1.5–2 μm wide at the apex, mostly unpigmented but occasionally with an indistinct cap or hood. Asci Porpidia-type, poorly developed, cylindrical, 75–90 × 20–25 μm; ascospores hyaline, (16–)19.6 ± 2.5(–25) × (7–)8.2 ± 0.6(–9) μm, l/w ratio (2.0–)2.4 ± 0.3(–3.1) (n = 20), with a thin perispore c. 1 μm wide (2–3 μm in N). Hypothecium c. 150 μm thick, hyaline to very pale brown, composed of vertically aligned hyphae merging imperceptibly into the hymenium, inspersed with granular inclusions c. 10 μm wide. All parts POL− except the hypothecium which is POL+ dull grey.

Conidiomata occasional to frequent, black with a glossy brown, gaping ‘ostiole’ when well developed, surrounded by a thick white margin, initially orbicular and 0.1–0.15 mm diam., becoming elongate to 0.3 mm, rarely lirelliform or shortly stellate. Conidia filiform, curved, hooked or sinuous, 20–25 μm long.

Chemistry

All spot tests negative. Confluentic acid chemosyndrome detected by TLC.

Etymology

The specific epithet (Latin: caeruleum = blue, ruber = red) refers to the distinctive contrast between the blue-pigmented hymenium and the red-pigmented inner exciple.

Distribution and ecology

Poeltiaria caeruleorubra is currently known from only two localities in Tasmania’s southern ranges, where it occurs on emergent dolerite boulders in alpine heathland. This habitat is typically very rich in lichens, especially crustose species.

Remarks

The new species has morphological characters typical of the genus Poeltiaria (i.e. Porpidia-type asci and a hyaline to pale brown hypothecium) and shares the distinctive, radially cracked, proper apothecial margin displayed by some other species of that genus, including the type species, P. turgescens. However, it differs from all other species of Poeltiaria in the distinctive reddish pigmentation of the inner exciple and the blue colour of the adjacent hymenium. Molecular data also place the new species in a clade with other species of Poeltiaria. Unfortunately, fresh material of P. turgescens was not available for sequencing so it cannot be stated categorically that the two species are congeneric.

The pigment in the epihymenium and the cortical cells of the thallus is initially dark olivaceous and unchanged in K but, after flushing with water, becomes red-brown with the addition of N and returns to olivaceous brown upon further flushing and the addition of K. It is unclear whether this pigment is Cinereorufa-green, which is present in the hymenium adjacent to the exciple, because at no stage is a bluish colour produced with K.

Additional specimen examined (paratype)

Australia: Tasmania: Snowy Range, plateau above Lake Skinner, 42°56′S, 146°40′E, 1180 m, 2016, G. Kantvilas 44/16 (HO 582933).

Porpidia lutulata Fryday, U. Rupr. & Kantvilas sp. nov

MycoBank No.: MB 8610730

Distinguished from other species of the genus by the lumpy granular thallus, the small apothecia with an internally red-brown proper exciple, the amyloid (I+ violet) medulla, and its phylogenetic position sibling to P. umbonifera and distant from other members of the genus (ITS, mtSSU and RPB1).

Type: Australia, Tasmania, Quoin Mountain, at the trig beacon, 42°33′S, 147°17′E, 895 m, on exposed vertical dolerite tors, 8 August 2021, G. Kantvilas 324/21 (HO 604564—holotype; MSC—isotype).

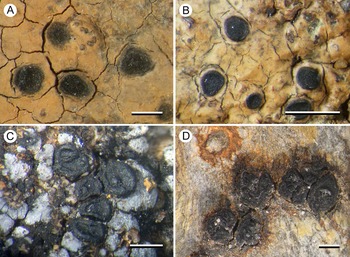

(Fig. 6)

Figure 6. Porpidia lutulata (Kantvilas 324/21—holotype). A, thallus with apothecia (arrow indicates conidioma). B, apothecia. C & D, apothecia; sections showing exciple with reddish brown cortex and hyaline medulla, and unconnected pale brown hypothecium. Scales: A & B = 1.0 mm; C & D = 50 μm. In colour online.

Thallus widespreading, covering several centimetres, effuse, 0.05–0.1 mm thick, composed of ±contiguous, irregular, ±convex, whitish grey to fawnish brown areoles 0.2–0.4(–0.8) mm across, with a rough, almost granular surface; prothallus absent. In section: sometimes with a thin, poorly differentiated, grey cortical layer (POL+) 10–20 μm thick above a hyaline layer 5–25 μm thick, subtended by a thick photobiont layer c. 150 μm; medulla to 25–50 μm thick, hyaline, IKIconc+ violet; all parts except the grey cortical layer POL−. Photobiont chlorococcoid, with individual cells thin-walled, 6–12 μm diam.

Apothecia numerous, black, lecideine, (0.4–)0.6–0.8(–1.0) mm diam.; disc flat and smooth when wet, often becoming convex, immarginate and gnarled when dry, often with a central umbo or ±gyrose; proper margin barely raised, 0.1 mm thick. In section: proper exciple well developed, with a thick (10–30 μm wide), heavily pigmented but not carbonaceous cortex that becomes red-brown at its inner edge (K+ intensifying), and a ±hyaline inner section with crystalline inclusions c. 10 μm across, composed of radiating hyphae 2–3 μm wide that become wider in the pigmented outer zone and reach 4 μm wide at the surface. Hymenium c. 110–130 μm thick; paraphyses sparingly branched and anastomosing over most of their length, becoming more branched and anastomosing in the upper 50 μm, 1–1.5 μm thick, not or only slightly capitate (to 2 μm), with the pigmented cap rarely apparent; epihymenium 15–20 μm thick with diffuse, olivaceous brown pigment (K−, N+ red), becoming bluish towards the exciple (K−, N+ red); subhymenium hyaline, 25–30 μm thick, composed of ±randomly aligned hyphae, POL−. Asci rarely well developed, Porpidia-type, cylindrical, c. 70 × 20 μm; ascospores simple, hyaline, thin-walled, (15–)16.2 ± 1.5(–19) × (–7)7.7 ± 1.1(–10) μm, l/w ratio (1.8–)2.1 ± 0.2(–2.4) (n = 10), with a thin perispore sometimes apparent. Hypothecium pale brown above, darker below, lacking the reddish coloration of the exciple, 75–100 μm thick, composed of ±randomly aligned hyphae, becoming ±horizontally aligned towards the exciple, POL−, continuous with the hyaline medulla of the exciple.

Conidiomata black, orbicular to slightly ovoid, 0.08–0.1 mm across, with a gnarled, shiny surface and a thick, white border 0.05 mm wide; conidia bacilliform, c. 5–6 × 1 μm.

Chemistry

All spot tests negative. No substances detected by TLC.

Etymology

From the Latin lutulatus (= muddy), referring to the predominant colour and appearance of the lichen.

Distribution and ecology

Known only from two localities in southern Tasmania where it occurs on alpine dolerite boulders, typically in sheltered crevices.

Remarks

This species clusters with Porpidia umbonifera in our phylogeny, and these two species are similar in that their thalli have an amyloid (I+ violet) medulla but lack secondary metabolites. In porpidioid Lecideaceae, this combination of characters is otherwise known only in Aurantiothallia, which differs in a number of morphological characters (innate apothecia, poorly developed exciple, only brown pigments present, etc.) and molecular data do not suggest a close relationship between them.

Porpidia lutulata and P. umbonifera cluster together in a clade sibling to Poeltiara/Xenolecia. They are separated from other species currently included in Porpidia and probably represent another distinct, genus-level group. However, because our tree is poorly supported in critical areas and one of the species has already been described in Porpidia, we choose to describe P. lutulata in Porpidia rather than erect a new genus that may prove to be superfluous. Morphologically, both species resemble species of the P. macrocarpa group in having black, sessile apothecia with a heavily pigmented hypothecium and an exciple with a dark cortex and paler medulla.

Additional specimen examined (paratype)

Australia: Tasmania: summit of Cathedral Rock, 42°56′S, 147°11′E, 880 m, 2013, G. Kantvilas 384/13 (HO 571507).

Porpidia umbonifera var. sanguinea Fryday, U. Rupr. & Kantvilas var. nov

MycoBank No.: MB 861074

Differing from the typical variety in having a red-pigmented inner exciple and also separated from P. umbonifera var. umbonifera by its DNA sequence data.

Type: Australia, Tasmania, Ben Lomond, Plains of Heaven, 41°32′S, 147°39′E, 1500 m, on alpine dolerite boulder, 8 February 2022, G. Kantvilas 240/22 (HO 607449—holotype).

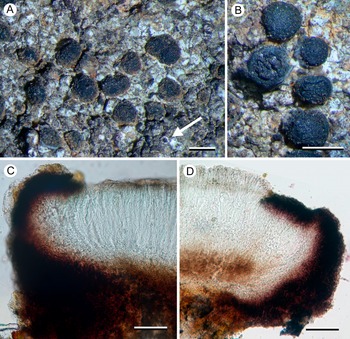

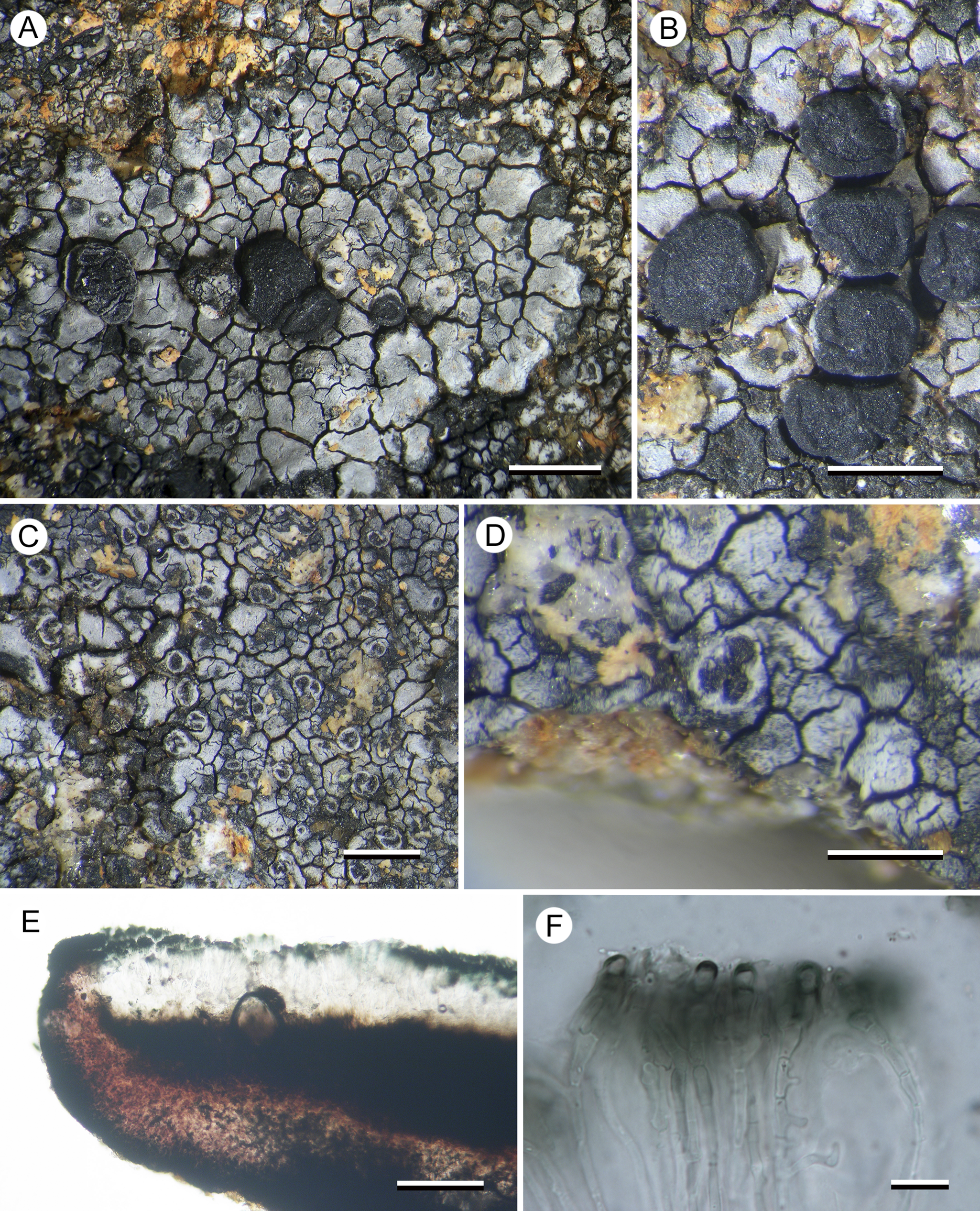

(Fig. 7)

Figure 7. Porpidia umbonifera var. sanguinea (Kantvilas 240/22—holotype). A, thallus with apothecia. B, apothecia. C, orbicular conidiomata. D, multilocular conidioma. E, apothecial section showing red-pigmented inner exciple. F, paraphyses, showing swollen apices with pigmented caps. Scales: A = 2.0 mm; B & C = 1.0 mm; D = 0.5 mm; E = 100 μm; F = 10 μm. In colour online.

Thallus effuse, silver-grey pruinose, sometimes without pruina and then rusty red, areolate, usually occurring in a mosaic with other crustose species, but often several centimetres across; areoles angular, 0.2–0.5 mm wide, 0.15–0.2 mm thick, usually slightly concave but sometimes flat or even slightly convex. In section: upper cortex composed of brown-pigmented (K−, N−) globose cells c. 5 μm diam., sometimes shortly elongated to 10 μm, overlain by a hyaline layer 3–5 μm thick, subtended by a narrow band c. 10 μm thick of hyaline, angular, rhomboid cells 5–10 μm across, with the bulk of the thallus taken up by a thick photobiont layer (150–170 μm); photobiont cells thin-walled, 8–15 μm diam.; medulla narrow to absent, intermixed with rock crystals from the substratum, I+ violet. All parts POL−.

Apothecia frequent, black, lecideine, sessile, basally constricted, ±orbicular, 0.8–1.6 mm diam., flat, with a thick (0.1–0.2 mm), slightly raised proper margin; disc sometimes pruinose, becoming convex and the margin then excluded. In section: proper exciple 80–100 μm wide laterally, up to 150 μm wide below the hypothecium, with a dark red-brown (K+ dark blue-green, N+ red) cortex 10–20 μm thick and a paler, red-pigmented (K−, N+ brown) medulla, composed of radiating hyphae c. 3 μm wide, widening to 5 μm at the cortex. Hymenium c. 100 μm thick, composed of sparingly branched and anastomosing paraphyses 1.5–2 μm wide, septate in the upper 10–15 μm and swelling to 3–5 μm at the apex, with a thin, blue-pigmented (K+ olivaceous, N+ red) hood; epihymenium 25–30 μm thick, dark blue-green (K+ olivaceous, N+ red); subhymenium c. 20 μm thick, composed of randomly aligned hyphae, hyaline in the upper part, pale brown below. Asci Porpidia-type, cylindrical to slightly clavate, 60–70 × 20–25 μm; ascospores hyaline, broadly ellipsoid, thick-walled, (13–)14.8 ± 0.9(–16) × (7–)8.0 ± 1.1(–10) μm, l/w ratio (1.6–)1.9 ± 0.2(–2.1) (n = 10), with a thin perispore that often swells to 5 μm thick in N. Hypothecium c. 150 μm thick, dark brown above and merging into the subhymenium, becoming red-brown below where it meets the exciple.

Conidiomata frequent, black, usually ±orbicular, rarely becoming linear, often in small groups, surrounded by a white thalline margin, 0.15–0.3 mm wide; conidia c. 5–6 × 1 μm.

Chemistry

All spot tests negative. No substances detected by TLC.

Etymology

The varietal epithet refers to the red pigmentation of the inner exciple (Latin: sanguinea = bloody), which is the only obvious morphological difference from the typical variety.

Distribution and ecology

Known from the Ben Lomond Plateau in north-eastern Tasmania and from Mt Wedge in the South-West, where it occurs on alpine dolerite boulders. These geographically widely separated localities suggest this taxon could be more widespread.

Remarks

This variety differs from the typical variety only in having a red-pigmented excipular medulla, but this distinction is supported by molecular data. The systematic position of P. umbonifera is discussed under P. lutulata. Sequences of the photobiont Asterochloris sp. were recovered from one collection (Kantvilas 491/14).

Additional specimens examined (paratypes)

Australia: Tasmania: Ben Lomond, Legges Tor, 41°32′S, 147°39′E, 1560 m, 2022, G. Kantvilas 115/22 (HO 606811); Mt Wedge summit, 42°51′S, 146°18′E, 1140 m, 2014, G. Kantvilas 491/14 (HO 576039).

New Reports for Tasmania

Porpidia albocaerulescens var. polycarpiza (Vain.) Rambold & Hertel

This taxon was previously reported from Queensland, Australia, by Rambold (Reference Rambold1989), who suggested that it may have a more northerly distribution in Australia than the typical variety. This is refuted by this report from Tasmania, where it occurred on rocks along a riverbank within cool temperate rainforest.

This variety apparently differs from P. albocaerulescens var. albocaerulescens only in the thallus containing norstictic acid rather than stictic acid, but our phylogeny shows the two taxa as siblings separated by a considerable genetic distance. However, the var. albocaerulescens sequence was obtained from a North American collection and sequences from sympatric specimens should be compared before considering changes to the status of var. polycarpiza.

Specimen examined

Australia: Tasmania: Rapid River, near bridge on Tarkine Drive, 41°09′S, 145°06′E, 70 m, 2016, G. Kantvilas 373/16, 374/16 (HO 585131, 585132).

Porpidia hydrophila (Fr.) Hertel & A. J. Schwab

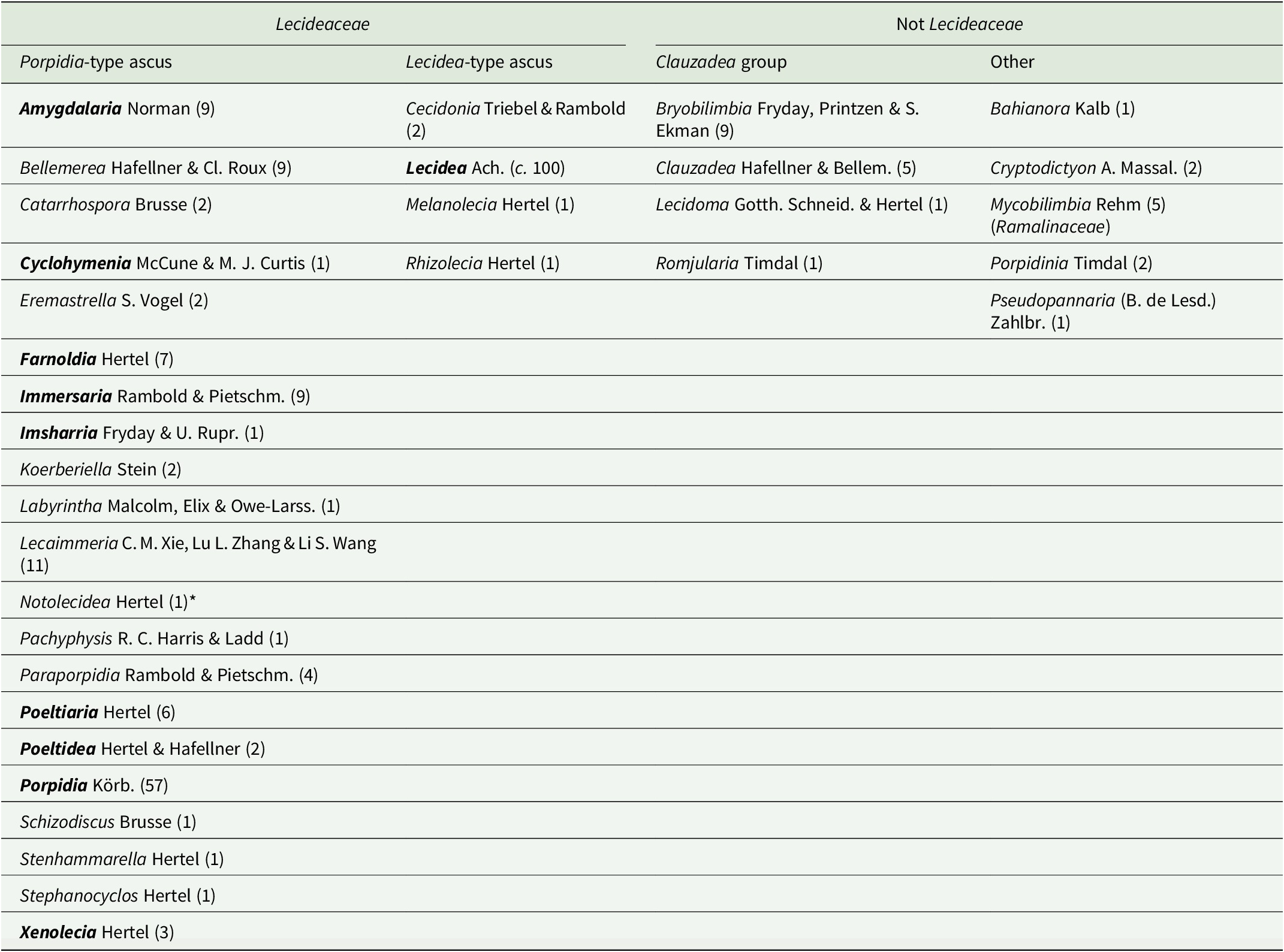

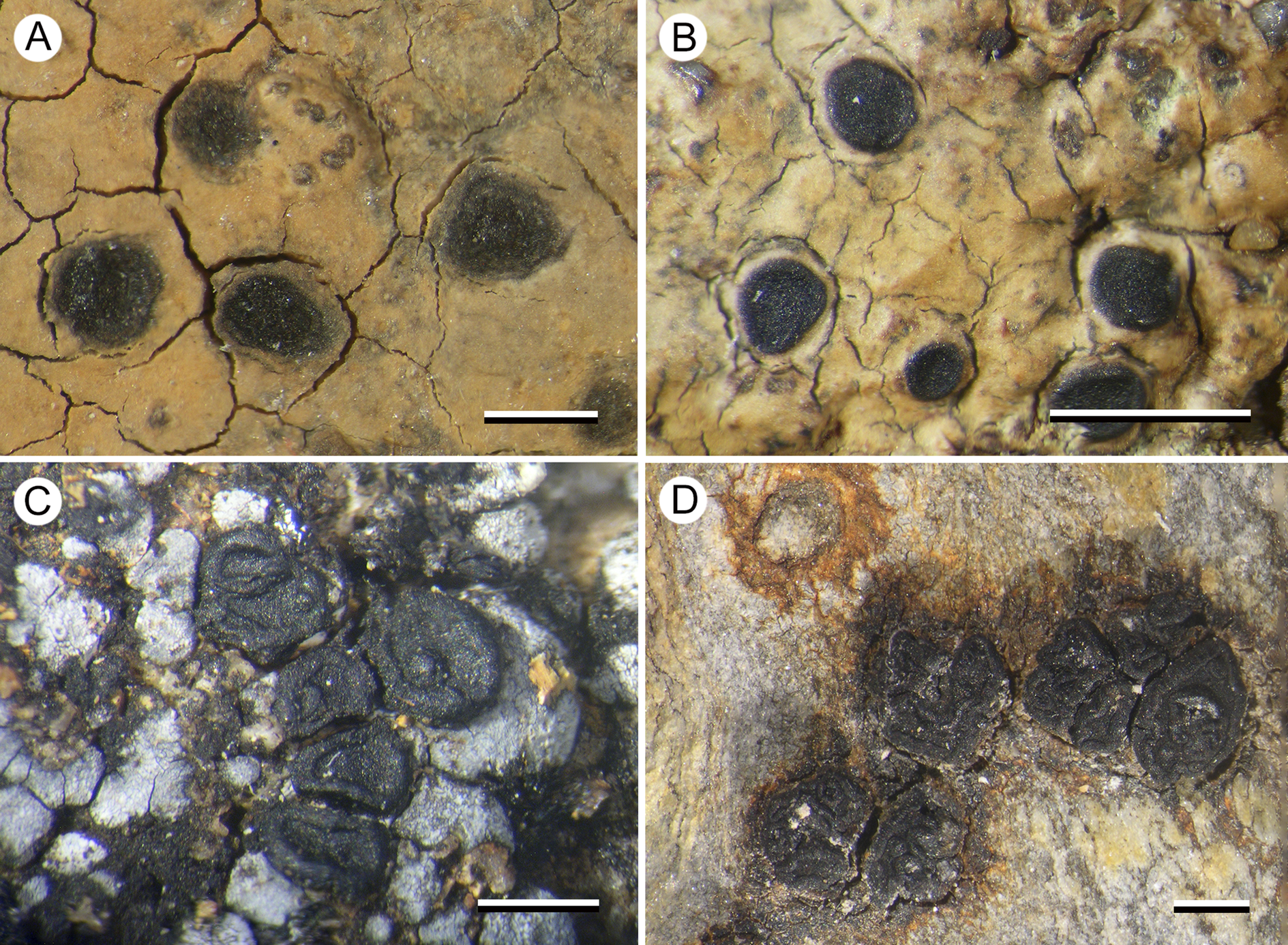

(Fig. 8)

Figure 8. Porpidia hydrophila (Kantvilas 259/22). A, thallus with apothecia. B, section through apothecium. C, thallus with conidiomata. D, multilocular conidioma. Scales: A = 1 mm: B = 25 μm; C = 0.5 mm; D = 100 μm. In colour online.

This species is included in the Australian lichen checklist (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2023) but not attributed to any jurisdiction and was not treated by Rambold (Reference Rambold1989). It is distinguished from all other species of Porpidia by its bright blue epihymenium and from species of Lecidea by its large halonate ascospores and Porpidia-type asci.

The Tasmanian collection, from dolerite pebbles in a shallow, intermittent, seasonal puddle in alpine heathland, supports numerous conidiomata that are unusual in that they resemble neither normal pycnidia nor the elongate conidiomata of other porpidioid Lecideaceae. They are described here:

Conidiomata dark brown to black (brown when wet), flat to slightly concave, 0.1–0.4 mm diam., ±flush with the surface of the thallus or slightly raised, mostly orbicular but becoming ovoid or irregular in outline and sometimes even elongate, initially smooth but becoming rugose when larger, with an indistinct, white margin apparently caused by decoloration of the surrounding thallus, internally with brown walls and surface layer, initially with a single opening 0.1–0.15 mm across, becoming multilocular in larger conidiomata; conidia straight, c. 12–15 × 1 μm.

Specimen examined

Australia: Tasmania: Ben Lomond, Plains of Heaven, 41°32′S, 147°39′E, 1500 m, 2022, G. Kantvilas 259/22 (HO 607530).

Porpidia umbonifera var. umbonifera (Müll. Arg.) Rambold

McCarthy (Reference McCarthy2023) reported this taxon only from mainland Australia (New South Wales and Victoria). It is identical to P. umbonifera var. sanguinea in morphology and chemistry except for its ±hyaline to brown excipular medulla. The systematic position of P. umbonifera is discussed under P. lutulata. Sequences of the photobiont Vulcanochloris aff. caneriensis were recovered from Kantvilas 668/12 and Kantvilas 21/14, and Asterochloris sp. from Kantvilas 257/22, which differed from the other two collections in having a rust red-coloured thallus. The collections seen are from widely separated alpine localities where the species occurred on alpine boulders as well as on small, loose pebbles. Further field studies may show it to be widespread in Tasmania.

Another collection (Kantvilas 47/20) is similar to P. umbonifera in having a silver-grey thallus lacking secondary metabolites and with an amyloid (I+ violet) medulla, but it differs in the thallus consisting of ±discrete areoles with a distinct edge and in having larger apothecia with a ±striate proper margin that is carbonaceous in section.

Specimens examined

Australia: Tasmania: northern summit of Mt Rogoona, 41°53′S, 146°12′E, 1330 m, 2012, G. Kantvilas 668/12 (HO 567887); Mackenzies Tier, Roscarborough, 42°02′S, 146°35′E, 1070 m, 2014, G. Kantvilas 21/14 (HO 572162); Ben Lomond, Plains of Heaven, 41°32′S, 147°39′E, 1500 m, 2022, G. Kantvilas 257/22 (HO 607528 – rusty thallus); summit of Milligans Peak, 42°14′S, 146°08′E, 1250 m, 2025, G. Kantvilas 47/25 (HO).

Discussion

The revised Lecideaceae phylogeny presented here (Fig. 1) is developed from that of Fryday et al. (Reference Fryday, Götz and Ruprecht2024), which used the markers ITS and mtSSU. By adding the marker RPB1 and the new taxa, several branches are now better supported. However, the backbone is still not supported and, therefore, introducing any major taxonomic changes on this basis would be premature. Several species/genera have shifted topology from their positions in the phylogeny of Fryday et al. (Reference Fryday, Götz and Ruprecht2024) and two new clades (IV, V) with exclusively Southern Hemisphere species have been recovered. The genus Lecidea still forms a strongly supported subclade and, together with the heterogenous subclade that includes Porpidia s. str., Lecidea auriculata/L. tessellata, Cyclohymenia epilithica and Immersaria, constitutes Clade I. The heterogenous group of Porpidia s. lat. and Amygdalaria species now form the very well-supported and separate Clade II, and the species/genus Imsharria forms a distinct lineage between Clades II and IV. Xenolecia and Poeltiaria, previously placed in the large main clade, have moved and, with the newly added species Porpidia umbonifera and P. lutulata, form the distinct and well-supported Clade IV. The two newly described genera Aurantiothallia and Hertelaria, with the species cf. Stephanocyclos sibling to Hertelaria, are placed together with Poeltidea in Clade V. The genus Farnoldia, represented by the type species F. jurana, appears as basal to Lecideaceae (Clade VI).

Genera not included in our phylogeny

Unfortunately, molecular data are either unavailable for several genera of porpidioid Lecideaceae, available only for markers not used in this study, or not available for the type species of the genus (Table 1). Specifically, the study of porpidioid Lecideaceae by Buschbom & Mueller (Reference Buschbom and Mueller2004), which included the genera Bellemerea, Koerberiella, Notolecidea, Pachyphysis, Stenhammarella and Stephanocyclos, used the different markers nrLSU and β-tubulin. We provide notes on these genera here, but further details can be found in Fryday & Hertel (Reference Fryday and Hertel2014).

Bellemerea, Lecaimmeria and Koerberiella all have apothecia with a thalline margin and were shown by Buschbom & Mueller (Reference Buschbom and Mueller2004) and Xie et al. (Reference Xie, Wang, Zhao, Zhang, Wang and Zhang2022) to form a separate clade distinct from the rest of the family. Koerberiella and Lecaimmeria are also known only from the Northern Hemisphere, whereas Bellemerea has been reported only rarely from the Southern Hemisphere. We could locate only two Tasmanian collections that had been identified as species of Bellemerea, but both had been wrongly identified. Catarrhospora has 3-septate to submuriform ascospores, a character unique in Lecideaceae, and is known only from South Africa; there are no recent collections suitable for obtaining molecular data. Eremastrella is a terricolous genus of arid environments with a distinctive thallus morphology (the so-called ‘window lichens’; Vogel Reference Vogel1955). Only mtSSU and RPB1 sequences are available but it was recovered as sibling to Porpidia cinereoatra by Fryday et al. (Reference Fryday, Printzen and Ekman2014). Labyrintha is endemic to New Zealand; it has large (60–70 × 30–35 μm), pigmented ascospores and was placed in the synonymy of Poeltidea by Fryday & Hertel (Reference Fryday and Hertel2014). Notolecidea has apothecia with a thalline margin and is known only from Îles Kerguelen in the southern Indian Ocean. In the phylogeny of Buschbom & Mueller (Reference Buschbom and Mueller2004), it resolved as sibling to the clade containing Pachyphysis, Farnoldia and Melanolecia. Pachyphysis is known only from North America and has thick paraphyses (up to c. 10 μm), a purple-pigmented hymenium and was shown by Bushbom & Mueller (Reference Buschbom and Mueller2004) to cluster with Farnoldia and Melanolecia at the base of their phylogeny. Paraporpidia is characterized by having non-halonate spores, filiform conidia, a dark-pigmented hypothecium and apothecia with a non-gyrose disc. The type species, P. aboriginum Rambold, is known from only a handful of sites in the arid regions of central Australia with no recent records. Schizodiscus Brusse is known only from high altitudes in South Africa and has immersed apothecia with a cracked disc and a reduced exciple. Stenhammarella is known only from Central Europe and China and was shown by Bushbom & Mueller (Reference Buschbom and Mueller2004) to cluster with the Porpidia macrocarpa group. Stephanocyclos is scattered throughout the southern subpolar region (including Tasmania) and is characterized by having apothecia with a prominent, segmented, angular proper margin, a carbonaceaous exciple, and filiform conidia.

Identification of Porpidia s. str.

Our phylogeny indicates that the genus Porpidia as currently circumscribed is polyphyletic, being split into four groups spread across three of the clades identified above. It is, therefore, necessary to ascertain which group represents Porpidia s. str. The genus Porpidia was erected by Koerber (Reference Koerber1855) based on the single species P. trullisata (Kremp.) Körb. Unfortunately, P. trullisata is a rare species from Central Europe for which sequence data is not currently available. However, P. trullisata closely resembles P. speirea (Ach.) Kremp, apparently differing only in having larger pruinose apothecia, and has often been recognized as a form or variety of it (e.g. Stein Reference Stein and Cohn1879; Arnold Reference Arnold1889; Clauzade & Roux Reference Clauzade and Roux1985), and so it is widely accepted that Porpidia s. str. is the group containing P. speirea. Unfortunately, there are problems surrounding the typification and delimitation of this taxon, which were explored and described in detail by Hertel (Reference Hertel1975). Acharius (Reference Acharius1798) gave only ‘ad rupes marinas’ for the locality in his protologue of Lichen speireus, and the neotype selected by Hertel (Reference Hertel1975) is from lowland, lakeshore granite in southern Sweden. However, most collections referred to Porpidia speirea are from calcareous rocks at higher altitudes, and so it is likely that this entity is distinct from P. speirea s. str. (as defined by the neotype). It is also possible that the correct name for this taxon may be P. trullisata. The reports of stictic acid in P. trullisata are based on confusion of this taxon with P. macrocarpa f. trullisata Zahlbr., a synonym of P. zeoroides (Anzi) Knoph & Hertel, which does contain stictic acid.

Intra-family groups

In addition to the new genera Aurantiothallia and Hertelaria proposed in this paper, several other groups occur in an anomalous position in our phylogeny. In many cases, there are names at genus-rank available for these groups (e.g. Haplocarpon M. Choisy for the P. macrocarpa group), and other groups may be congeneric with genera for which sequences are currently unavailable (e.g. Notolecidea, Paraporpidia, Stephanocyclos). The correct phylogenetic position, circumscription and nomenclature for these groups will be treated in a separate publication currently in preparation.

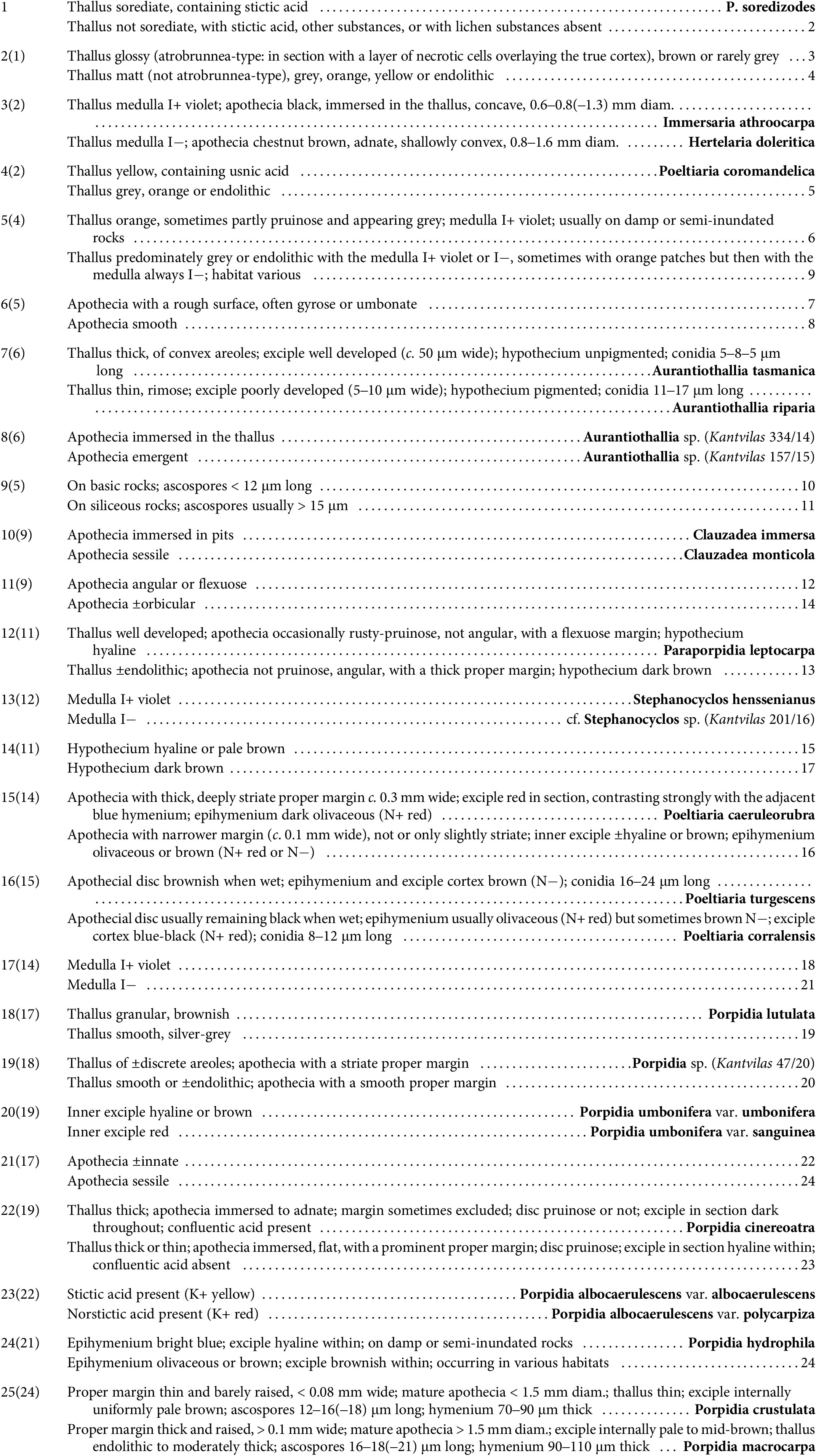

Provisional key to porpidioid lichen species occurring in Tasmania

When using this key it is important to remember that many collections of porpidioid lichens from Tasmania remain unidentified, and provisional identifications should be confirmed by checking against full descriptions of the species.

Conclusion

In this study, we have identified and proposed as new to science two genera, four species and one variety of porpidioid Lecideaceae from Tasmania, in addition to further refining the phylogenetic relationships within this group. However, a large number of collections from Tasmania remain unidentified, and many are currently unidentifiable because no recent collections are available for molecular analysis. These include the species included in Fig. 9 and the identification key, as well as many more for which the significance of their morphological characters remains unclear. The phylogenetic tree is also still a work in progress because of the lack of support in critical areas and the lack of molecular data from some porpidioid Lecideaceae (e.g. Notolecidea, Paraporpidia, Stephanocyclos). For this reason, we decline to make too many genus-level changes until we can be certain that names for these groups do not already exist. We continue to work on this group of lichenized fungi and are optimistic of being able to present a better supported phylogeny in the near future.

Figure 9. Known unknowns. A, Aurantiothallia sp. A (Kantvilas 334/14). B, Aurantiothallia sp. B (Kantvilas 157/15). C, Porpidia cf. umbonifera (Kantvilas 47/20). D, cf. Stephanocyclos sp. (Kantvilas 201/16). Scales = 1 mm. In colour online.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0024282925101333.

Acknowledgements

We thank Tim Wheeler, Måns Svensson and Bruce McCune for providing sequences of Immersaria, Amygdalaria and Cyclohymenia respectively, and Damien Ertz for useful discussion concerning the phylogenetic position of Notolecidea subcontinua. We are also grateful to Matthias Affenzeller for helping with sequence annotations. The curators of F, CANL and COLO are also thanked for the loan of collections in their care. Molecular analyses were financially supported in whole or in part by the Austrian Sciences Fund (FWF) 10.55776/P35512. For open access purposes, the authors have applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any author-accepted manuscript version arising from this submission. Much of the material studied, especially from Ben Lomond, Tasmania, was collected in the course of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery’s Expeditions of Discovery programme. GK thanks Penny Clive (Detached cultural organisation) and the Friends of TMAG for their support of this initiative. We also thank Dr Ernest Lacey for his investigation of the chemistry of Hertelaria, Linda in Arcadia for advice concerning Latin names and nomenclature, and Måns Svensson and an anonymous reviewer for their careful and insightful reviews that greatly improved this contribution.

Author ORCIDs

Alan Fryday, 0000-0002-5310-9232; Ulrike Ruprecht, 0000-0002-0898-7677; Gintaras Kantvilas 0000-0002-3788-4562.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.