1 Introduction

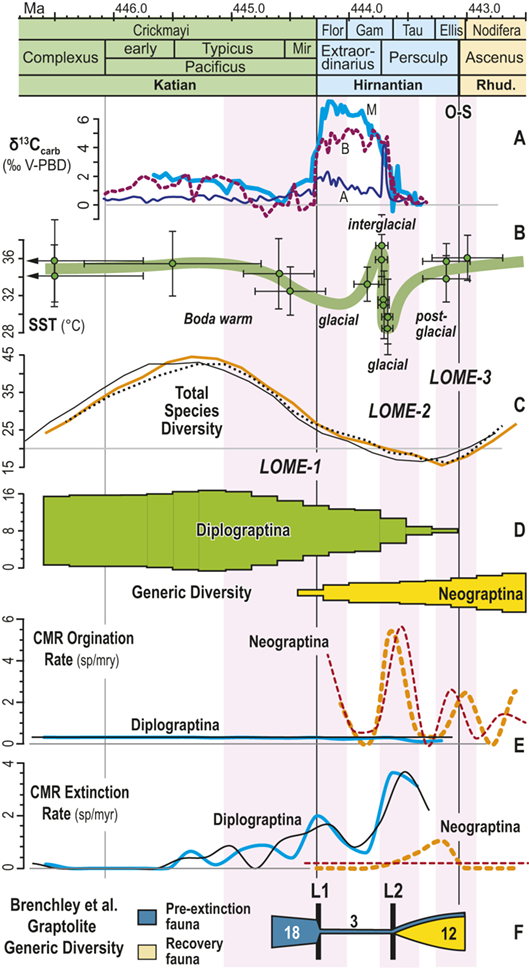

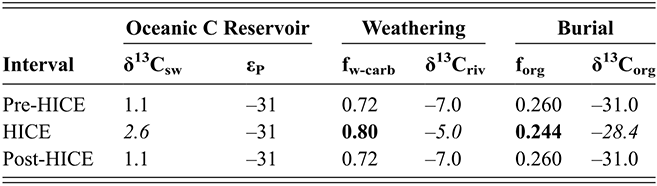

Recent geochemical studies suggest that large environmental changes took place during the Late Ordovician in the interval leading up to and during the Late Ordovician mass extinction (LOME). These changes include a secular decline in global temperatures, most likely in response to reduced atmospheric pCO2, possibly related to ultramafic weathering or enhanced carbon burial (possibly due in part to land plant and marine green algal biomass expansion; see the recent review by Algeo & Shen Jun 2023) or some combination of those factors, which culminated in continental-scale glaciation. In addition, some recent work suggests that Late Ordovician cooling may have been interrupted by warming episodes created by the catastrophic outpouring of CO2 and H2S from massive volcanicity, although this remains controversial (e.g., Bond & Grasby Reference Bond and Grasby2017, Dahl et al. Reference Dahl, Hammarlund, Rasmussen, Bond and Canfield2021, Zhou Yu-ping et al. Reference Yu-ping, Yong and Wang2024). The Late Ordovician also apparently experienced large changes in sea level as well as changes in nutrient cycling, carbon burial, and phytoplankton community composition, among other possible effects. These oceanographic and nutrient cycling effects are manifest in pronounced facies changes, stable isotopic excursions, including the widely documented Hirnantian isotopic carbon excursion (HICE), as well as reported perturbations in nitrogen, sulfur, uranium, and others (e.g., Melchin et al. Reference Melchin, Mitchell, Holmden and Štorch2013, Harper Reference Harper2023, Young et al. Reference Young, Edwards, Ainsaar, Lindskog and Saltzman2023).

Testing alternative hypotheses about the direct cause (or causes) of the LOME requires a clear and precise understanding of the timing, rate, and selectivity of the extinctions. As the current, regionally heterogeneous response to global warming demonstrates, however, no single section or region can provide an adequate proxy for global change. Thus, a full assessment of mass extinction dynamics must include a global analysis that integrates the individual paths of biotic response to the local facies and habitat manifestations of global environmental change, while also compensating as much as possible for the artifacts that arise from sequence stratigraphic effects on the preserved record (Holland & Patzkowsky Reference Holland and Patzkowsky2015, Holland Reference Holland2016, Zimmt et al. Reference Zimmt, Holland, Finnegan and Marshall2021, Holland Reference Holland2023). Yet many recent papers regarding the LOME have nonetheless extrapolated from small regional studies or even single sections to global-scale conclusions about Late Ordovician climate and mass extinctions while taking little or no account of local-scale basin dynamics or potential sequence stratigraphic effects on the record. It is not surprising, then, that the literature is now replete with conflicting explanations for this momentous episode in Earth history.

The specific goals of the present research are, first, to use the paleotropical synthesis of graptolite species occurrence data employed by Melchin et al. (Reference Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Fan2017) to assess the rate, timing, and selectivity of graptolite species turnover within a global, high-resolution, sample-based composite timescale; and secondly, to apply that sample-based composite timescale to make a precise set of comparisons between the resulting global history and the patterns of environmental change in local sections across the paleotropics and thereby test the principal alternative hypotheses about the drivers of mass extinction during the Late Ordovician.

1.1 Background

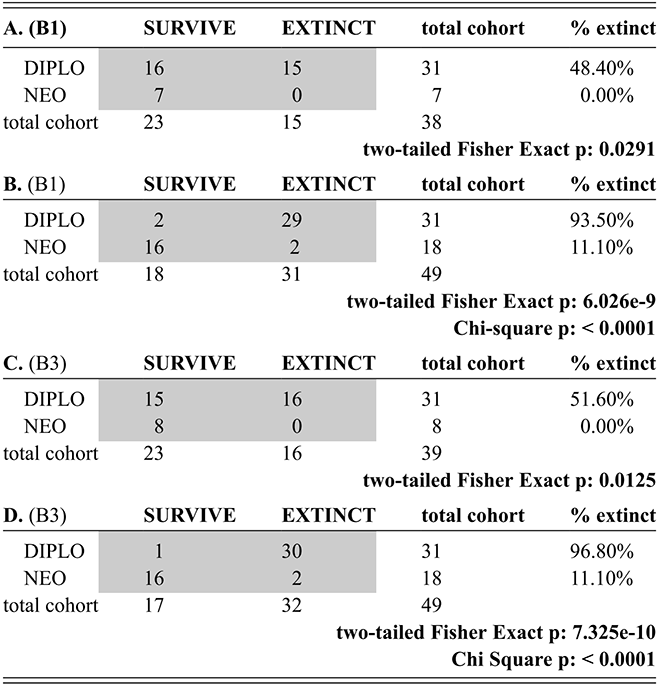

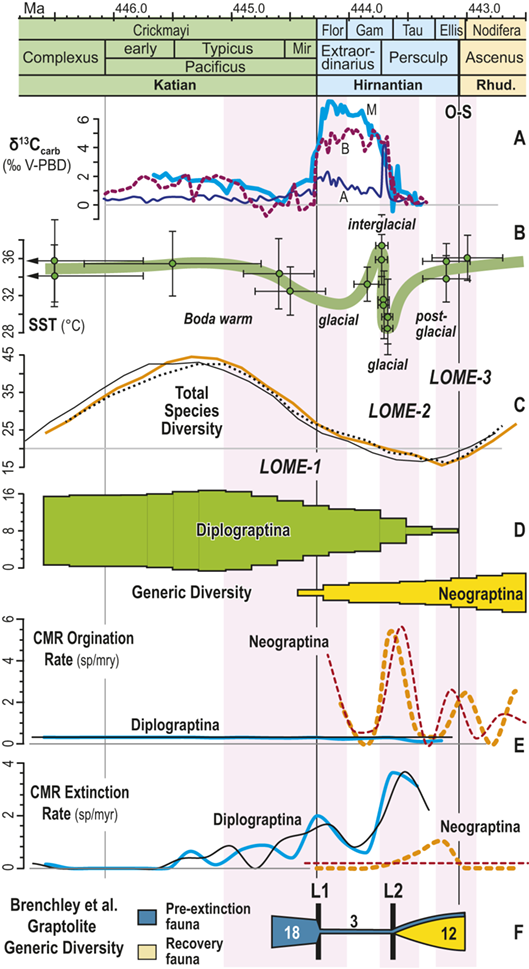

From their analysis of the Late Ordovician record, Brenchley et al. (Reference Brenchley, Marshall and Carden1994, Reference Brenchley, Marshall and Underwood2001, Reference Brenchley, Carden and Hints2003) suggested that the Late Ordovician mass extinction comprised two pulses, and this interpretation has been widely (if somewhat imprecisely) adopted in studies of the LOME (e.g. Sheehan Reference Sheehan2001, Finnegan et al. Reference Finnegan, Heim, Peters and Fischer2012b, Melchin et al. Reference Melchin, Mitchell, Holmden and Štorch2013, Harper et al. Reference Harper, Hammarlund and Rasmussen2014, Luo Gen-ming et al. Reference Gen-ming, Algeo and Ren-bin2016, Zou Cai-neng et al. Reference Cai-neng, Zhen and Poulton2018a, Bond & Grasby Reference Bond and Grasby2020, Hu Dong-ping et al. Reference Dong-ping, Meng-han and Xiao-lin2020, Chen Yan et al. Reference Yan, Chun-fang, Zhen and Wei2021, Kozik et al. Reference Kozik, Gill, Owens, Lyons and Young2022a, Harper Reference Harper2023, Hu Rui-ning et al. Reference Rui-ning, Jing-qiang and Wen-hui2024, among many others). Not coincidentally, the Late Ordovician glacial interval, although part of a long-term and gradually increasingly severe glacial epoch, is now widely regarded as having culminated in two major glacial advance cycles within the Hirnantian itself separated by a brief warm period that took place early in the interval of the Metabolograptus persculptus Biozone (reviewed in Ghienne et al. Reference Ghienne, Desrochers and Vandenbroucke2014; see Fig. 1). Nonetheless, Chen Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Jun-xuan2005b), based on species occurrence data from a set of four sections in South China, found that graptolite extinction in this interval was dominated by a single early Hirnantian pulse. Likewise, Wang Guang-xu et al. (Reference Guang-xu, Ren-bin and Percival2019) concluded from their global review of Late Ordovician faunas that turnover among brachiopods during the LOME was dominated by a pulsed, although somewhat diachronous, extinction around the beginning of the Hirnantian that was then followed by an extended period of turnover as the newly evolved faunas tracked the changing Hirnantian and early Rhuddanian environments. These results reinforce the concerns, highlighted by Holland and Patzkowsky (Reference Holland and Patzkowsky2015), that we should have about the degree to which the “two pulse” model is a real feature of the LOME rather than an artifact generated by the effects of glaciation on the rock record itself.

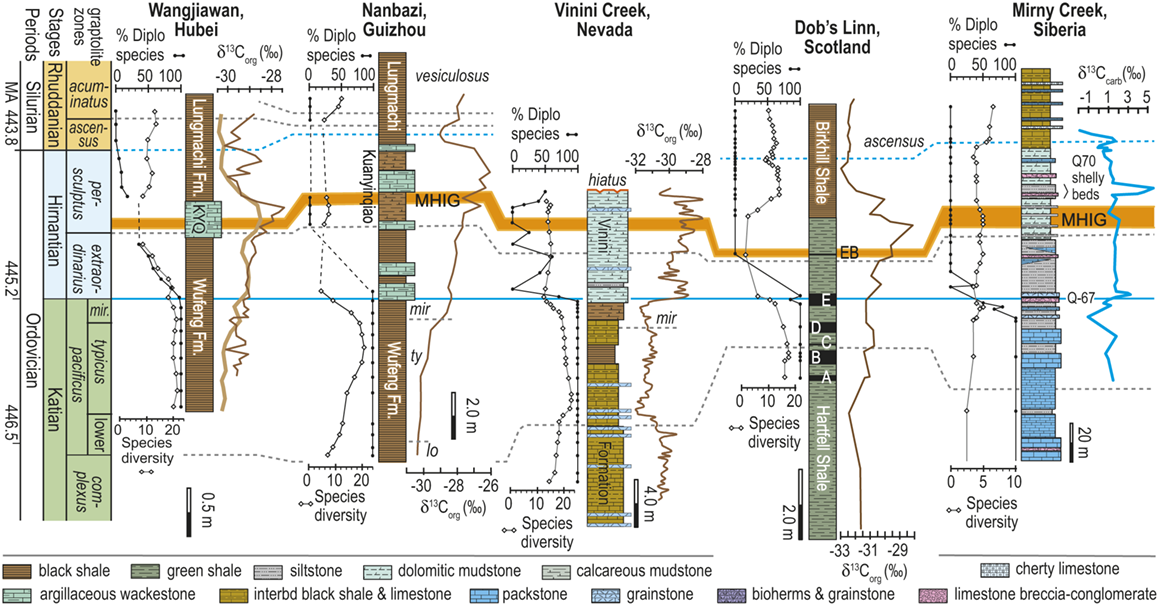

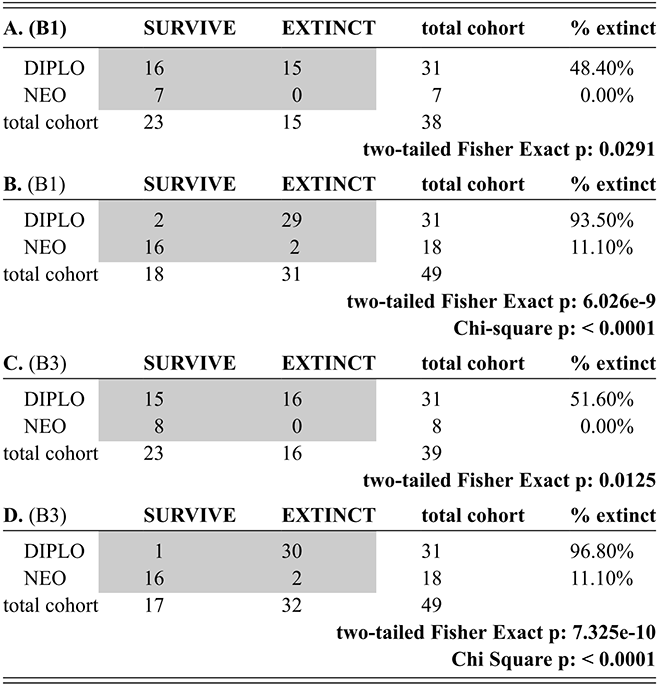

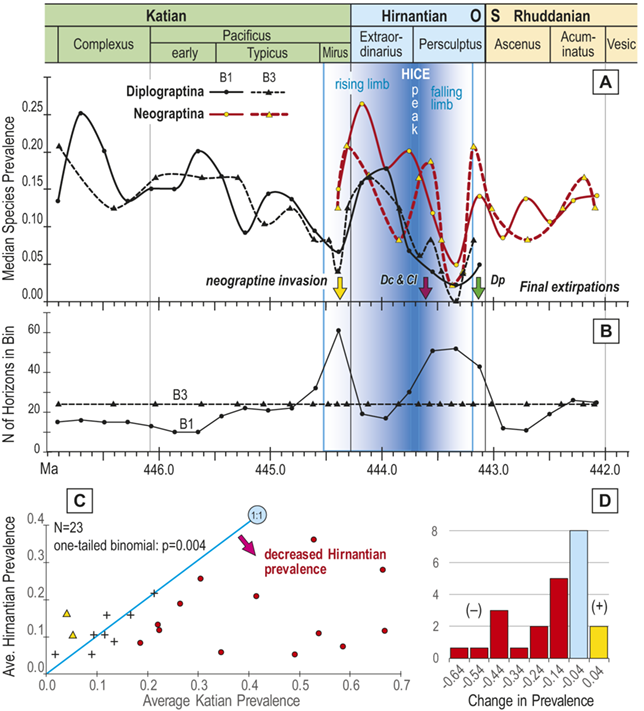

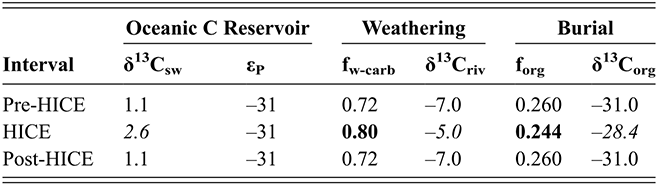

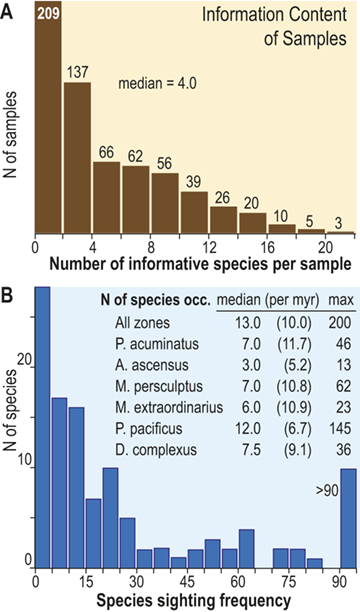

Figure 1 Observed trajectories in graptolite species diversity and turnover in clade composition relative to lithostratigraphy and the Hirnantian carbon isotopic excursion (HICE) at five intensively studied sections from across the paleotropics (see Fig. 2 for site locations). Sections exhibit distinctly different patterns of graptolite faunal turnover relative to lithological change and the trajectory of the C-isotopic excursion, as described later in the Element. Sections shown, from left to right: Wangjiawan (25) and Honghuayuan/Nanbazi (12) in South China; Vinini Creek (24) and Dob’s Linn (6) on opposite sides of Laurentia; and Mirny Creek (19) in Kolyma. Full names of graptolite biozones (in descending order, including abbreviations): Cystograptus vesiculosus Biozone, Parakidograptus acuminatus Biozone, Akidograptus ascensus Biozone, Metabolograptus persculptus Biozone, Metabolograptus extraordinarius Biozone, Paraorthograptus pacificus Biozone, Diceratograptus mirus Subzone, Tangyagraptus typicus Subzone (ty); lower unnamed subzone of P. pacificus Biozone (lo), Dicellograptus complexus Biozone. Other abbreviations: A,B,C,D,E, Anceps Bands A–E; EB, Extraordinarius Band; KYQ, Kuanyinqiao Beds; MHIG, mid-Hirnantian interglacial episode. Placement of the MHIG is based on a combination of geochemical and faunal data; see Appendix A for additional information about the occurrence of Metabolograptus persculptus in the EB at Dob’s Linn and Appendix B for data sources.

1.1.1 Graptolites and the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction

Although meaningful analyses of faunal dynamics have been conducted using genera, it is obvious that species-level data are preferable when the record is sufficiently complete. The graptolite fossil record is such a case (see, for example, Sadler et al. Reference Sadler, Cooper and Melchin2011). Based on their analysis of a global compilation of graptolite species ranges, Foote et al. (Reference Foote, Sadler, Cooper and Crampton2019, p. 1049) estimated that for the species that dwelt within the region of preserved Ordovician and Silurian strata, approximately “75% of Ordovician–Silurian graptoloid species have been sampled and that, of those known from more than one resolvable stratigraphic level, c. 85% of their original durations are represented by their composite stratigraphic ranges.” Foote et al. concluded that relative to other studied animal groups, graptolites have one of the most completely sampled fossil records.

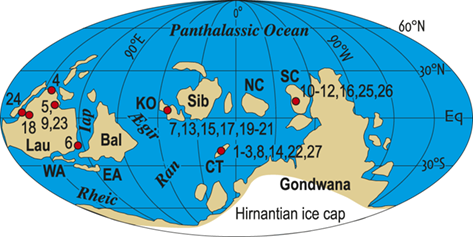

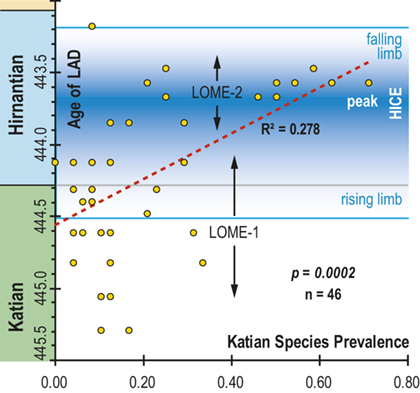

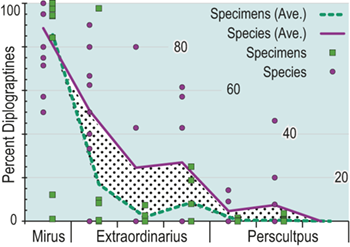

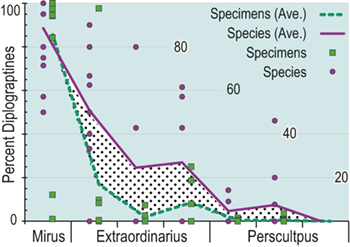

Additionally, as macrozooplankton, graptolites offer a unique perspective on environmental dynamics within the surface regions of the world’s oceans. Individual species are known to have been widely distributed across the paleotropics (Chen Xu et al. Reference Xu, Melchin, Jun-xuan and Mitchell2003, Boyle et al. Reference Boyle, Sheets and Wu2017) (Fig. 2) and, as such, their fates were likely to have been intimately intertwined with similarly global features of the Late Ordovician environment (Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Rigby, Loydell and Bates2012, Reference Cooper, Sadler, Munnecke and Crampton2014, Crampton et al. Reference Crampton, Cooper, Sadler and Foote2016, Crampton et al. Reference Crampton, Meyers and Cooper2018). Observed graptolite species diversity in the paleotropics declined dramatically through the LOME from a peak of about 80 species known in mid Katian time (~ 446 Ma) to a Hirnantian nadir of about 20 species, barely 1.5 Myr later (Sadler et al. Reference Sadler, Cooper and Melchin2011). The composition of the faunas changed dramatically as well. Late Ordovician graptolite faunas were populated by species from two major clades: the Diplograptina and the Neograptina, which had diverged during the Darriwilian, approximately 15 Myr prior to the LOME events (Mitchell et al. Reference 74Mitchell, Goldman and Klosterman2007a, Reference Mitchell, Maletz and Goldman2009, Štorch et al. Reference Štorch, Mitchell, Finney and Melchin2011, Maletz Reference Maletz2023). In the late Katian, prior to the mass extinction, the Diplograptina were diverse and common throughout the paleotropics, where they comprised some 16 genera and were the only planktic graptolites present (Chen Xu et al. Reference Xu, Melchin, Jun-xuan and Mitchell2003, Goldman et al. Reference Goldman, Mitchell and Melchin2011, Melchin et al. Reference Melchin, Mitchell, Naczk-Cameron, Junxuan and Loxton2011, Goldman et al. Reference Goldman, Maletz, Melchin, Jun-xuan, Harper and Servais2014). The Late Ordovician Neograptina, in contrast, have a sparse fossil record and are only known from about ten species within two genera that were entirely confined to mid-high paleolatitude regions. However, coincident with the onset of the LOME in the latest Katian (i.e., within the Diceratograptus mirus Subzone of the P. pacificus Biozone), the Neograptina invaded the paleotropics and rapidly became the dominant graptolites (Chen Xu et al. Reference Chen, Jun-xuan, Melchin and Mitchell2005a, Goldman et al. Reference Goldman, Maletz, Melchin, Jun-xuan, Harper and Servais2014, Sheets et al. Reference Sheets, Mitchell and Melchin2016). By the end of the Hirnantian, the Diplograptina were entirely extinct (Melchin & Mitchell Reference Melchin, Mitchell, Barnes and Williams1991, Melchin Reference Melchin1998, Chen Xu et al. Reference Chen, Yuan-dong and Jun-xuan2006b, Finney et al. Reference Finney, Berry and Cooper2007, Goldman et al. Reference Goldman, Mitchell and Melchin2011, Bapst et al. Reference Bapst, Bullock, Melchin, Sheets and Mitchell2012).

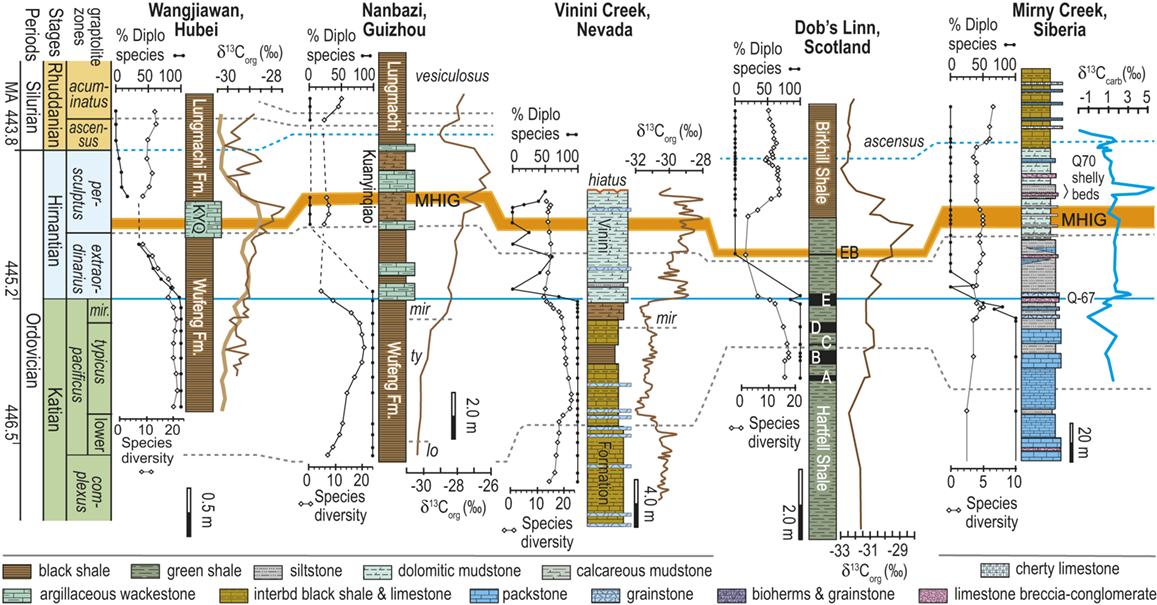

Figure 2 Location map of 27 Late Ordovician to early Silurian graptolite-bearing sections studied here. Paleoplates from which data were used in the present study are labeled with the following abbreviations: Bal, Baltica; CT, Chu Ili-Tien Shan terrane; EA, East Avalon terrane; Iap, Iapetus Ocean; KO, Kolyma-Omolon terrane, Lau, Laurentia; NC, North China; SC, South China; WA, West Avalon terrane. Sites numbered as in Melchin et al. (Reference Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Fan2017); see Appendix 2 for data sources and sample-by-sample species occurrence data from these sites.

1.1.2 Distinguishing the Local and the Global

In general it appears that the macroevolutionary rates and clade turnover in graptolite faunas exhibit long-term rhythms that are comparable in duration with global Milankovitch-driven climate cycles (Crampton et al. Reference Crampton, Meyers and Cooper2018). Graptolite species turnover rates shifted to higher values during the LOME, in synchrony with the HICE and Hirnantian glaciation, and those elevated rates then persisted for the remainder of the clade’s history (Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Sadler, Munnecke and Crampton2014, Crampton et al. Reference Crampton, Cooper, Sadler and Foote2016). Those results clearly implicate climate oscillations as a major driving force in graptolite extinction and several prior studies have proposed specific ties between graptolite ecology and the likely effects of Hirnantian climate change that could account for their extinction during the LOME (Melchin & Mitchell Reference Melchin, Mitchell, Barnes and Williams1991, Chen Xu et al. Reference Xu, Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Jun-xuan2005b, Finney et al. Reference Finney, Berry and Cooper2007). Nevertheless, the precise global pattern of timing and rate of turnover in graptolite faunas relative to Late Ordovician environmental change has not been well characterized at a temporal resolution sufficient to assess the degree of synchrony with the Hirnantian glacial advance and retreat cycles or other paleoenvironmental changes through that interval. Furthermore, regional and local-scale environmental effects (including but not limited to those associated with preserved facies shifts or hiatuses) have overprinted the record of global climate change. For instance, detailed local records of graptolite species turnover relative to the HICE and the mid-Hirnantian interglacial episode (which may provide approximate, independent measures of synchroneity among sections – see Holmden et al. Reference Holmden, Mitchell and LaPorte2013, Melchin et al. Reference Melchin, Mitchell, Holmden and Štorch2013, Ghienne et al. Reference Ghienne, Desrochers and Vandenbroucke2014) reveal disparate patterns of change in species diversity and faunal composition. These patterns may be grouped broadly into three sets (Figs. 1, 2):

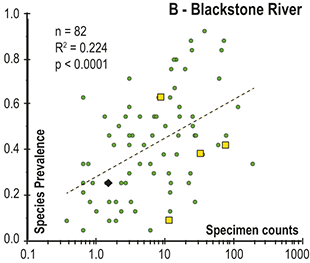

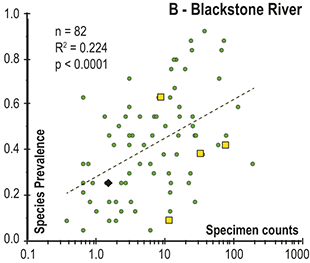

Abrupt loss of all graptolites coincident with early Hirnantian facies change; examples include sections at Blackstone River, Laurentia [site 4], Ojsu Spring, Kazakhstan [22] and Ludiping, South China [16].

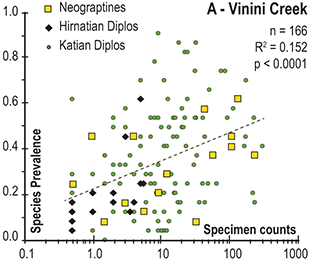

Graptolites remain common in the Hirnantian strata but faunas undergo a rapid loss of diversity and abrupt replacement of diplograptines by neograptines through the Katian-Hirnantian transition interval (ex: Vinini Creek, Laurentia [24], Mirny Creek, Siberia [19], Durben well, Kazakhstan [8], Honghuayan, South China [12]).

Faunas show an extended period of species diversity decline and clade replacement over the course of the latest Katian to mid-Hirnantian – namely through the entire first Hirnantian glacial megacycle (ex: Wangjiawan, South China [36], Dob’s Linn, Laurentia [6]).

In all of these cases diversity decline commences in the mid to upper part of the uppermost Katian Paraorthograptus pacificus Biozone; roughly in step with the onset of the HICE, however, the disappearance of species is earlier and more rapid in the more on-shore sites and latest in the more oceanic sites (see Sheets et al. Reference Sheets, Mitchell and Melchin2016, figs. S4, S5). Nonetheless, species losses are present in the deep sites that do not appear to be purely a result of facies and habitat displacement (e.g., at Vinini Creek, Sheets et al. Reference Sheets, Mitchell and Melchin2016), and at several of these sites species that appeared to go extinct in this initial pulse reappear as Lazarus taxa in the Metabolograptus persculptus Biozone in association with the falling limb of the HICE in the upper Hirnantian (Štorch et al. Reference Štorch, Mitchell, Finney and Melchin2011). Thus, many of the apparent early Hirnantian losses may be artifacts of sampling or habitat displacement or both (Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Sheets and Belscher2007b) rather than true extinctions, consistent with sequence stratigraphic considerations (Holland & Patzkowsky Reference Holland and Patzkowsky2015, Holland Reference Holland2016, Reference Holland2023).

This ambiguity about the timing of extinctions is amplified by the individual failures of even these well-studied sections. Two examples will suffice here. The Mirny Creek section (the most complete and most fossiliferous of the seven Omulev Uplift sections studied in detail by Koren et al. Reference Koren, Oradovskaya, Pylma, Sobolevskaya and Chugaeva1983) is orders of magnitude thicker than the other principal graptolite-bearing Late Ordovician sections, and graptolites are rare in the Mirny Creek strata (Fig. 1). Most species are represented in each of the Omulev region collections by one to five specimens (Koren et al. Reference Koren, Oradovskaya, Pylma, Sobolevskaya and Chugaeva1983), despite a cumulative collection effort amounting to 20 person-months (T. Koren’ personal communication to CEM, 2005). Thus, it is likely that only the most common species were recovered, and that if some diplograptine species persisted into the Hirnantian there as rare individuals (see Koren’ & Sobolevskaya Reference Koren’ and Sobolevskaya2008), as we know they did elsewhere, these relict species almost certainly would not have been recovered.

The late Katian and early Hirnantian record at the Dob’s Linn section, which contains the global stratotype for the base of the Silurian System and has figured prominently in discussions of the LOME, is even more highly incomplete. Graptolite faunas of the late Katian P. pacificus Biozone, although reasonably diverse (Fig. 1), are recoverable from only two relatively thin black shale intervals (Anceps Band C and D; Williams Reference Williams1982). This zone has an estimated duration of some 1.8–3.38 My in the GTS 2012 and 2020 timescales, respectively (Cooper & Sadler Reference Cooper, Sadler, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012, Goldman et al. Reference Goldman, Sadler, Leslie, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020). The base of the Hirnantian is not recorded precisely, but most likely lies somewhere between Band D and Band E, which contains the first record of Metabolograptus extraordinarius, and thus probably corresponds to a level within the early Hirnantian M. extraordinarius Biozone (Williams Reference Williams1982, Melchin et al. Reference Melchin, Holmden, Williams, Albanesi, Beresi and Peralta2003, Chen Xu et al. Reference Xu, Jia-yu and Jun-xuan2006a). Restudy of the very small fauna preserved within the overlying, ~ 2 cm-thick Extraordinarius Band indicates that it contains Metabolograptus persculptus and is thus of late Hirnantian, M. persculptus Biozone age (Melchin et al. Reference Melchin, Holmden, Williams, Albanesi, Beresi and Peralta2003; see also Appendix A of this Element for further details). Accordingly, Band E is the only level from which early Hirnantian graptolites may be recovered at Dob’s Linn. It is thick enough to be subsampled (Fig. 1) but nonetheless represents only a small portion of the total duration of this biozone. Furthermore, sedimentological evidence suggests that Band E was deposited during an interglacial episode (Armstrong & Coe Reference Armstrong and Coe1997), and is thus atypical of the glacial conditions that prevailed during the early Hirnantian. Thus, the critical late Katian to mid Hirnantian LOME interval is represented at this site by five samples, none of which appear to sample the first main glacial advance. Since resolving the order of a set of events requires at least as many samples as events, the record at Dob’s Linn is grossly insufficient to resolve the extinction history of the 17 species present in the P. pacificus interval there. It is surprising, therefore, to see graptolite diversity data from this section cited as evidence that a spike in Hg abundance at this site indicated that the mass extinction was caused by an abrupt pulse in volcanic activity (Bond & Grasby Reference Bond and Grasby2020). Such a causal relationship simply cannot be determined from those data.

From the foregoing it is clear that no single section, not even the best, can serve adequately as a proxy for the full environmental and evolutionary history that we seek to understand. Accordingly, we have compiled a global composite based upon the full record of graptolite species sightings, occurrence by occurrence, through 27 sections from across the paleotropics (Melchin et al. Reference Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Fan2017) and herein report on the pattern of graptolite turnover extracted from that composite. As we discuss more fully later, this high-resolution composite overcomes some of the failures of the record imposed by local sections and permits a close, and precisely timescaled comparison between geochemical environmental proxies from those sections and the composite macroevolutionary history of graptolites.

1.1.3 Sample-Based Graptolite Occurrence Dataset

The dataset that we employed for this study of graptolite species dynamics through the LOME is the same dataset employed in Melchin et al. (Reference Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Fan2017). It comprises 3,508 presence-absence records for 105 species from 633 collections distributed among 27 measured sections. The selected sections are those that exhibit relatively continuous sedimentation through the LOME interval, are rich in graptolites, and have been documented via detailed systematic study of those faunas. We have compiled this dataset from the published record of species occurrences; in several cases, however, we have augmented that record by additional collections from the sections (especially at Dob’s Linn) and, for most of these collections, by direct restudy of the original graptolite material. We have applied a uniform taxonomy to the species occurrences insofar as this is possible based on the published record and our ability to restudy those collections. The study sites occur within the region ~ 20° north and south of the paleoequator and encompass approximately 210° in paleolongitude. Data from higher-latitude regions are available from very few sites and include too few species in common with the paleotropical faunas to be reliably integrated by the automated sequencing approach that we employed to form a unified composite of species occurrences (see the “Methods” section later in the Element). Thus, although conceptually of value in the present context, these occurrences are not treated quantitatively herein.

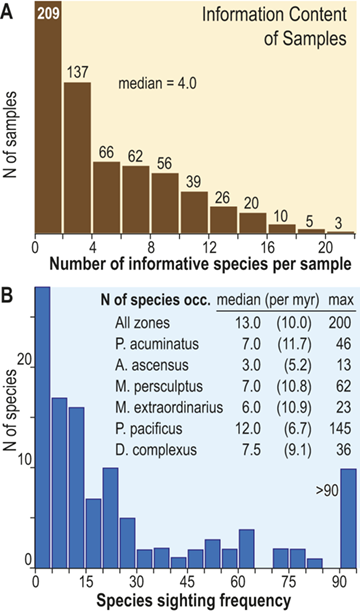

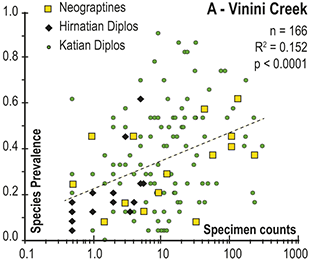

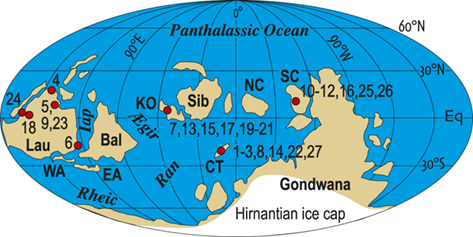

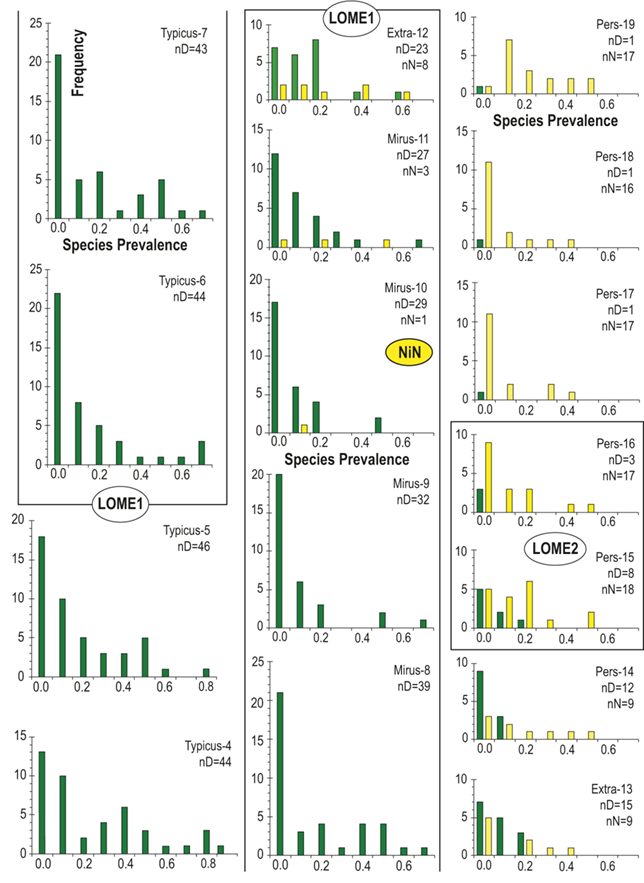

The number of species that cooccur within individual samples varies considerably among the samples employed for this study and most samples contain few species (Fig. 3), some of which are confined to single sections. Such species are not stratigraphically informative and the age of the samples in which they occur is constrained only by the presence of other, more widely shared species – either in those samples or in other samples in the same section. In the present study we employ the occurrences of stratigraphically informative species to form an ordered sequence of samples by the methods described later in the Element. The ranked frequency distribution of informative species diversity per sample follows the expected negative log-normal distribution for sampled species diversity more generally, with an R2 of 0.9627 between informative species diversity and the log of the number of samples. The median per-sample diversity of stratigraphically informative species is 4.0 (Fig. 3A). Similarly, histograms of species sighting frequency (Fig. 3B) indicate that most stratigraphically informative species occur in few samples (Fig. 3B), consistent with the findings of Foote et al. (Reference Foote, Sadler, Cooper and Crampton2019); however, Fig. 3B also shows a second mode of species that are moderately to widely occurring with 50 or more occurrences in the sampled sections. The median number of occurrences per species ranges from three to 12 among biozones in the latest Ordovician and earliest Silurian, which, although somewhat variable, shows no obvious trend through the study interval, particularly when treated as sightings per million years (Fig. 3B; we describe the sources of the zone durations in Section 2.2). Furthermore, the number of sightings per million years for individual species during the Hirnantian are similar to the overall median for the dataset. Accordingly, the available data appears to be sufficient to warrant the analyses described in the following sections.

Figure 3 A Histogram of the number of stratigraphically informative species per sample (ordinate). Thirty-five samples contain only species that are not shared with samples from other sections (i.e., species that are unique to single localities) and thus have zero informative species. The position in the ordinal composite of such samples is constrained only by samples above or below them that do contain stratigraphically informative species. The ordinal position of 67 percent of samples is constrained by the joint occurrence in those samples of three or more species and that of slightly less than half is constrained by five or more. B, Histogram of the sighting frequency (i.e., the number of recorded occurrences) for each species through its full range within the dataset, together with tabulated median, median/myr, and maximum sighting frequencies within individual biozone intervals and the study interval as a whole; for example, Appendispinograptus supernus (which is the most widely reported species in the set) is reported in 200 samples within the full dataset and in 145 samples within the P. pacificus Biozone.

Figure 3Long description

A. The upper panel presents a histogram of the number of species within samples as a documentation of the diversity values recorded are counts of the number of stratigraphically informative species, i.e., species at occur in more than one stratigraphic section. The histogram contains 11 bins, each with an interval width of 2, and they exhibit a monotonically decreasing frequency value as sample diversity increases from one to a maximum of 22. Thus, the left-most is also the highest column and represents the number of samples that contain 1 or 2 stratigraphically informative species, and the last (eleventh) represents samples with 23 or 24 species. The number of samples for each of these cohorts is 209, 137, 66, 62, 56, 39, 26, 20, 10, 5, and 3. The median number of informative species per sample is 4.0.

B. The lower panel also contains a histogram of the number of occurrences per species (species sighting frequency) for the data set as a whole, as well as a small table of statistics about the number of occurrences per species within each graptolite biozone. The histogram contains 19 bins, each with an interval width of 5. The largest number of species (28) have one or two occurrences, and the number of species with increasing sighing frequency falls rapidly to a low of one species that has 41 to 45 occurrences. This is followed by a slight increase in the number of species with yet higher sightings to a secondary mode of four with 61 to 65 occurrences, following which species with higher sightings again become fewer, with none that have 86 to 90 occurrences. The overflow bin of species with greater than 90 occurrences includes 10 species, the most common of which, Appendispinograptus supernus, is recorded in 200 samples within the full dataset. Inset within the area of the figure is a table that reports three measures of the species sighting frequency distribution: median, median/myr, and maximum observed values. Values are given for the whole data set and for each biozone, from youngest to oldest: all zones 13.0 10.0 200 P. acuminatus 7.0 11.7 46 A. ascensus 3.0 5.2 13 M. persculptus 7.0 10.8 62 M. extraordinarius 6.0 10.9 23 P. pacificus 12.0 6.7 145 D. complexus 7.5 9.1 36

2 Methods

2.1 Determining Species Ranges

We determined graptolite species ranges by use of an automated sequencing approach called Horizon Annealing (Sheets et al. Reference Sheets, Mitchell and Izard2012, Melchin et al. Reference Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Fan2017). Horizon Annealing (HA) is a modification of the more widely used constrained optimization (CONOP) approach developed by P. M. Sadler and colleagues (Kemple et al. Reference Kemple, Sadler, Strauss, Mann and Lane1995, Sadler & Kemple Reference Sadler, Kemple, Cooper, Droser and Finney1995, Sadler et al. Reference Sadler, Kemple, Kooser and Harries2003). These automated sequencing approaches are based on the contention that the first and most fundamental task for measuring species durations in the fossil record is to determine the order of those events – the species’ global first and last appearance events (FAD and LAD, respectively). That set of ordered events is then scaled relative to a convenient timescale – generally one measured in millions of years and derived from geochronologically dated samples that can also be placed within the ordinal sequence of events (see the discussion in Goldman et al. Reference Goldman, Sadler, Leslie, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020 and references cited therein).

Detailed descriptions of the HA ordination process are given in Sheets et al. (Reference Sheets, Mitchell and Izard2012) and Melchin et al. (Reference Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Fan2017), but briefly, both the HA and CONOP automated sequencing techniques seek to determine the global ordinal sequence of a set of species’ FADs and LADs in such a way that the ordination minimizes the sum of all the species ranges while also accounting for the observed overlaps among the species ranges. CONOP does this by explicitly ordering species’ FADs and LADs based on the order of these events within individual sections. HA, in contrast, orders all available samples (not just range ends) based on the species contents of the samples (constrained by stratigraphic position within sections) and the implications of those occurrences for the overlap of species ranges, seeking to minimize the number of range overlaps while again accounting for all observed within-sample co-occurrences and range overlaps. The ordinal position of 67 percent of samples is constrained by the joint occurrence in those samples of three or more species and that of slightly less than half is constrained by five or more species (Fig. 3A).

For the purpose of sample ordination in HA, we may define the term “taxa” broadly to include not only species occurrences but also any other observable event that appears to have regional or global chronostratigraphic significance, such as volcanic ash layers, unique lithostratigraphic markers (such as sequence boundaries or other distinctive event beds), or chemostratigraphic events, among other possibilities. In the process of constructing the ordination employed here, Melchin et al. (Reference Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Fan2017) included the Kuanyinchiao Bed, which is a lithostratigraphically distinctive unit that is widely distributed in the mid-Hirnantian succession of South China (Chen Xu et al. Reference Chen, Jia-yu, Yue and Boucot2004, Chen Qing et al. Reference Qing, Jun-xuan, Melchin and Lin-na2014) as well as the rising and falling limbs of the HICE, each treated as discrete taxa (see Melchin et al. Reference Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Fan2017 for further discussion).

For this analysis all of the samples and taxa (whether graptolite species or other event types) were weighted equally. This approach did not privilege ‘key’ or zonal index taxa and did not assume that the FAD of M. extraordinarius (or of any taxon) is everywhere the same age. Thus, the ordination employed here is an unbiased maximization of all the available information in the dataset about the sequence of graptolite FADs and LADs and does not rely upon any particular assumption about the correspondence of species appearances or disappearances to Late Ordovician glacial or other events (such as the HICE) or to the timing of those events. Each is allowed to find its own level, as it is best fit by the data overall. The resulting ordination integrates species occurrences across regional facies gradients and paleoplates within a sequential framework that maximizes the fit of all the available data to the modeled species durations. It is this relaxation of the assumption of synchroneity among species range ends and the integration of occurrences across regional facies gradients (from on-shore sites to outer shelf and slope sites) that maximizes the likelihood of overcoming taxon range truncations imposed by eustatic changes in sea level and the resulting incompleteness of the geological record (Holland Reference Holland2020, Zimmt et al. Reference Zimmt, Holland, Finnegan and Marshall2021).

The Horizon Annealing composite employed here has three additional features that are noteworthy in the present analyses. Firstly, the HA composite is amenable to jackknife analysis, in which sections are removed from the dataset, one section at a time, and the ordination solution is then recalculated. The standard deviation of the variation in the placement of each sample across the set of jackknife replicates may serve as a measure of uncertainty in the position of that sample in the ordination (Melchin et al. Reference Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Fan2017). This uncertainty naturally differs among samples based on the faunal content of the sample and its stratigraphic context. In the present case, the median standard deviation in horizon placements (omitting the lowest and highest 16 percent of ordinal positions, where variance in position appears to be constrained by edge effects) is 8.14 ordinals. This jackknife uncertainty value provides a useful gauge of the reliable resolution of the ordination and thus served as a guide to selecting a minimum temporal bin duration for our turnover analysis.

Secondly, because the analyzed sample set retains all occurrences of each of the graptolite taxa in the studied sections, rather than only their FADs and LADs, the final ordination includes information about the frequency with which taxa occur through the succession and among sites. That information, then, can be used to assess the likelihood of encountering an extant taxon in an observational interval. This is a key piece of information needed to refine estimates of species origination and extinction rates and to assess their interdependency with changes in completeness of the dataset through the glacial interval (Foote Reference Foote2001). We will return to this topic later in our discussion of Capture-Mark-Recapture analysis.

Thirdly, because HA orders samples rather than taxa, and because all samples from a given section must remain in their observed stratigraphic order, HA can carry any sample through the ordination process, irrespective of whether that sample contains species or other properties that are informative about their position in the ordinal sequence. Thus, the HA composite can include occurrences of species that are unique to single samples or sections in so far as these horizons are constrained by other horizons in the same sections. More importantly, this property of HA allows ordinal placement of samples that bear locally unique chemostratigraphic, paleoenvironmental, or lithostratigraphic information of value to the interpretation of the geological and evolutionary history of the species of concern. We make use of this feature in our discussion of the possible environmental causes of the observed graptolite species turnover. Taken together these features provide a well-grounded evidentiary basis from which to assess species turnover dynamics and facilitate discrimination between local and global patterns of turnover and their relationships to paleoenvironmental change.

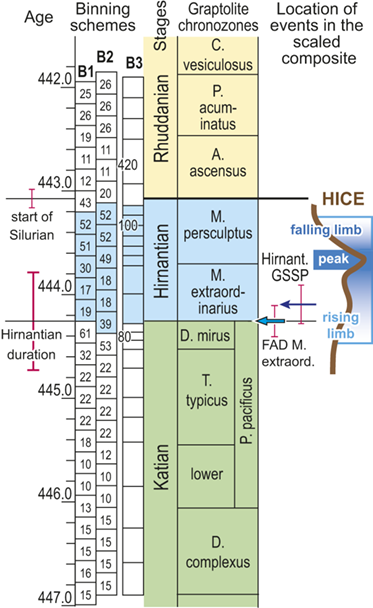

2.2 Temporal Scaling of the Ordinal Composite

In the HA composite, each sample occupies a unique position in the ordered sequence of samples. In order to provide species ranges in millions of years, we must convert that ordinal sequence to a timescaled succession. We estimated median durations (in Myr) for D. complexus through C. vesiculosus biozones based on those given in GTS2012 (Cooper & Sadler Reference Cooper, Sadler, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012, Melchin et al. Reference Melchin, Sadler, Cramer, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012) and combined those estimates with additional estimates of zone duration. These latter include estimates derived from geochronological age dates (Ling Ming-xing et al. Reference Ming-xing, Ren-bin and Guang-xu2019, Du Xue-bin et al. Reference Xue-bin, Yong-chao and Dan2020) and astrochronological interval durations (Lu Yang-bo et al. Reference Yang-bo, Chun-ju and Shu2019, Jin Si-ding et al. Reference Si-ding, Hu-cheng and Xing2020, Zhong Yang-yang et al. Reference Yang-yang, Huai-chun and Jun-xuan2020). The 3.38 Myr duration of the P. pacificus Biozone in the GTS2020 timescale (Goldman et al. Reference Goldman, Sadler, Leslie, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020) is unusually long compared to that in the GTS2012 and to other estimates of the duration of this zone. Consequently, we did not use the GTS2020 zone durations in our timescaling process although we did adopt 443.07 Ma as the current best estimate of the age of the beginning of the Silurian. After determining the median duration of each zone, we placed the position of zone boundaries in the composite based on the ordinal position of the FAD of the key index taxon for each zone. Working from the GTS2020 estimated age of the beginning of the Silurian (i.e., the start of the A. ascensus Biozone; 443.07 Ma), we used the median durations to provide estimates of the geochronological age of each of the other zonal boundaries. Finally, we used linear interpolation to convert the ordinal positions of all horizons within each of the biozones to a corresponding geochronological age. The resulting intervals in the scaled composite that encompass the set of samples from each of the graptolite biozones or subzones are chronostratigraphic units – that is, they are our best estimate of the particular intervals of geological time during which the strata of the biozones were deposited. Following the standard terminology of the International Commission on Stratigraphy, we refer to these intervals in our scaled composite as chrons and subchrons and label them by the trivial epithet of the eponymous species of the corresponding biozone (e.g., “Extraordinarius Chron,” and so on).

We divided the resulting temporally scaled composite into twenty-four analytical intervals (referred to herein as bins), each with a duration of 210,000 years.Footnote 1 These temporal bins contain an average of 24 horizons and a range of 10 and 61 horizons per bin. Thus, all bins are longer than the jackknife uncertainty in the ordinal position of horizons and most are several times longer. Most of the biostratigraphic units recognized through the latest Ordovician and early Silurian formed during intervals on the order of 0.6 Myr and are represented in the dataset by two or three bins. The relatively long P. pacificus Chron (with its three subchrons), which has a median estimated duration of 1.8 Myr in the datasets we employed, is represented by eight or nine bins. The temporal resolution of our chosen binning is comparable to that which Chen Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Jun-xuan2005b) employed in their analysis of graptolite species turnover in the Yangtze Platform region of China and similar to the duration of the moving window that Copper et al. (Reference Cooper, Sadler, Munnecke and Crampton2014) and Crampton et al. (Reference Crampton, Cooper, Sadler and Foote2016, Reference Crampton, Meyers and Cooper2018) employed in their analyses of graptolite species diversity and turnover.

Recognizing that uncertainty in the ordinal location of events in the Melchin et al. (Reference Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Fan2017) HA composite is substantial relative to the resolution in our binning scheme, we constructed two alternative placements of the 24 equal-duration bins relative to the composite sequence: binning schemes, B1 and B2 (Fig. 4). We also employed a third, substantially different binning scheme, B3, that we describe further later. These alternatives provide an indication of the effects of bin boundary placement on the estimated rates and timing of species turnover. In the first binning scheme, B1, we placed the bin boundaries such that the first bin spans the beginning of the Complexus Chron and the start of the 14th bin coincides with the global FAD of Metabolograptus extraordinarius (i.e., to the start of the Extraordinarius Chron). That level in the composite is equivalent, within error, to the position of the Hirnantian GSSP at Wangjiawan, South China, which also lies within B1 bin-14. Thus, bin B1-14 represents the beginning of the Hirnantian Age as formally defined (see Melchin et al. Reference Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Fan2017). In B2, we offset the bins upward by approximately one-half a bin so that the start of the first bin coincides with the FAD of D. complexus (= the beginning of the Complexus Chron) and the FAD of M. extraordinarius falls within B2-13. This bin placement retains the Hirnantian GSSP level within B2-14, and thus, does not impose synchroneity between the global first appearance of M. extraordinarius and the start of the Hirnantian Age.

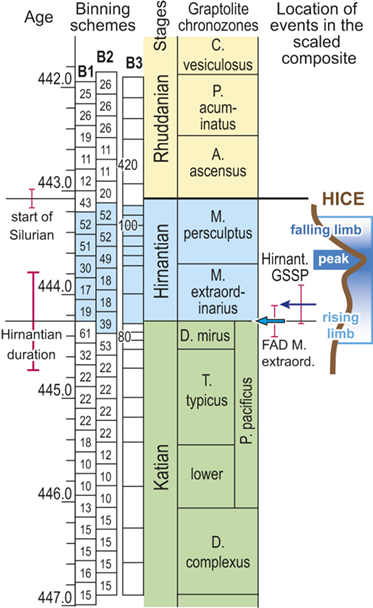

Figure 4 Timescale employed for the analysis of graptolite species diversity and turnover during the late Katian and Hirnantian ages (Late Ordovician Epoch) to early Rhuddanian Age (Llandovery Epoch, Silurian Period). Geochronological ages (in Ma) and chronozone durations employed herein based on the GTS2020 timescale (Goldman et al. Reference Goldman, Sadler, Leslie, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020) and data from the literature (see Table 1 and text for discussion). Uncertainty error bars (±2σ) shown for the geochronological age of the beginning of the Silurian, duration of the Hirnantian (based on calculations herein), the first appearance datum (FAD) of Metabolograptus extraordinarius and the Hirnantian GSSP in the timescale, along with the location of the rising limb, peak, and falling limb of the widespread Hirnantian d13C isotopic excursion (HICE), all based on the ordinal position of global events, including the FADs and LADs of the rising and falling limbs of the HICE, in the Melchin et al. (Reference Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Fan2017; see also Appendix B) composite. Also shown is the temporal alignment of the three sets of 24 analytical bins (B1-B3) employed for the diversity analysis. All bins in B1 and B2 are 210 Kyr in duration but encompass different numbers of horizons (N from 10–52); those of B3 are variable in duration (80–420 Kyr) but each includes 24 horizons. Hirnantian bins are shaded and the beginning of the first Hirnantian-aged bin in the B1 set (B1-14) is aligned with the beginning of M. extraordinarius Chron, whereas the beginning of the first bin in B2 and B3 is aligned with the beginning of the D. complexus Chron. Based on the placement of samples marking the LAD of the rising limb and FAD of the falling limb of the HICE (see Melchin et al., Reference Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Fan2017 for discussion of the coding of the segments of the HICE) the late HICE peak displayed at Wangjiawan (site 25) and Dob’s Linn (site 6) and shown in Fig. 1, occupies an interval from about 443.73 ± 0.19 Ma, coeval with the start of the Persculptus Chron, to about 443.62 ± 0.10 Ma at the beginning of the falling limb of the HICE in mid Persculptus Chron time. At other sites, such as Vinini Creek (site 24) and Blackstone River (site 4), the broader HICE peak commences near the beginning of the Hirnantian

The offset between the B1 and B2 schemes results in differences in the total number of bins that incorporate Hirnantian samples (six in B1 and seven in B2) and changes the extent to which the 24 bins extend into the early Silurian (Fig. 4). They also shift slightly the overlap between the Mirus Subchron and our bins. This is noteworthy because previous work on the LOME indicates that both the turnover events and related environmental changes that are associated with the LOME (including disruptions of the carbon system reflected in the HICE) accelerated during the Mirus Subchron. That upsurge in the pace of LOME-related change will thus appear in slightly different places among the three binning schemes; it occupies the 12th and 13th bins in B1, only the 12th bin in B2, and the 9th–11th bins in B3 (more on this last scheme later).

Foote (Reference Foote, Erwin and Wing2000) demonstrated that short-term changes in sampling intensity or probabilities of taxon recovery affect estimates of rates of origination and extinction. As we noted earlier, the number of samples included in each bin differs among bins and it also differs among binning schemes for similar points in the time series (Fig. 4). This arises because the biozones that we used to scale the composite themselves differ in duration and because the number of samples within each biozone differs substantially among biozones independently of their duration (Table 1). Consequently, the temporal spacing of the ordinal horizons differs through the time series. We have used two different approaches to assess the impact of the differing levels of sampling among bins. First, by shifting bin boundaries to form the B1–B2 sets we not only altered the placement of environmental events relative to those boundaries (concentrating or spreading episodes), we also shifted the density of data within bins (Fig. 4) relative to those events. For instance, the four bins that span the beginning of the Hirnantian in B1 contain 32, 61,19 and 17 horizons, whereas those in B2 contain 22, 53, 39, and 18. We also constructed the B3 binning, in which each of the 24 bins contains exactly 24 horizons. Those bins also average 210 Kyr, as in the other two bin sets, but range in duration from 80 to 420 Kyr. This clearly shifts the density of data in a dramatically different way, equalizing sampling per bin at the cost of equal duration bins. Features of the turnover history of graptolites shared among these three different bin sets must necessarily be largely independent of related sampling effects, at least at the ~ 210 Kyr resolution of the dataset. An obvious alternative is to analyze the data via a method, such as capture-mark-recapture analysis, that directly addresses uneven rates of taxon recovery, which we describe in the following section.

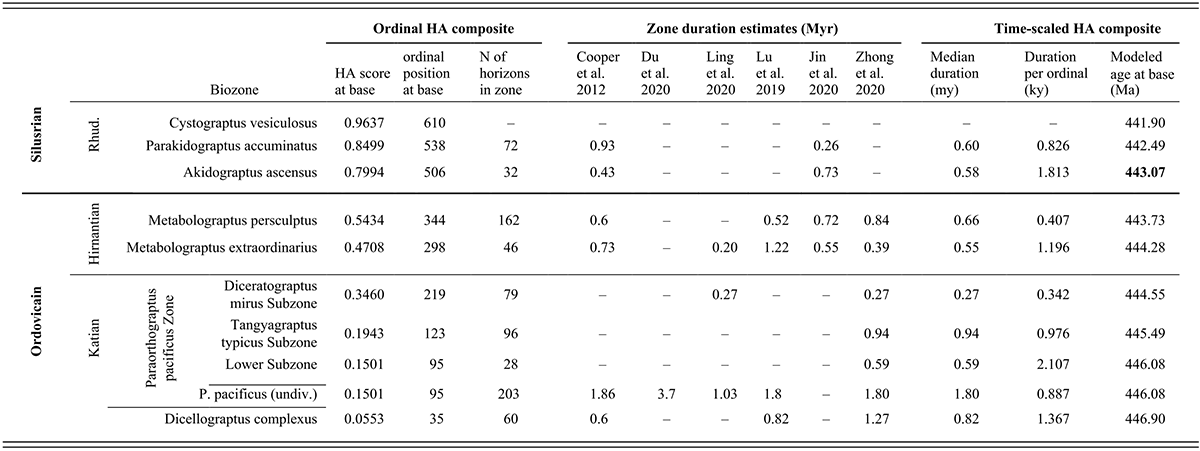

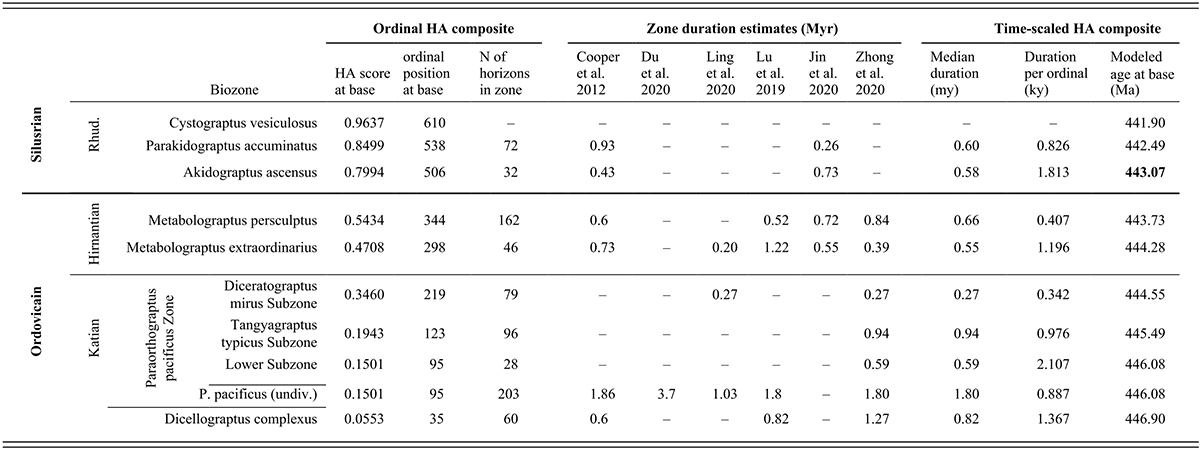

Table 1Long description

This table presents data about the temporal duration and geochronological age of the stratigraphic intervals examined in this study. The chronostratigraphic interval examined is divided in the table into three sets of rows, highest (also the youngest) at the top and the lowest (oldest) at the bottom, and these intervals are labeled along the left side of the table. The highest of the three intervals considered here is the lower part of the Rhuddanian Stage, which is the basal part of the Silurian System. This interval contains three graptolite biozones that, also from highest to lowest, are the Cystograptus vesiculosus, Parakidograptus acuminatus, and Akidograptus ascensus biozones. The next oldest interval is the Hirnantian Stage, which is the highest of the Upper Ordovician Series, and consists of two biozones, the Metabolograptus persculptus and M. extraordinarius biozones, in descending order. The lower of the three examined intervals is the uppermost part of the Katian Stage, also part of the Upper Ordovician. That interval includes two biozones, the Paraorthograptus pacificus and Dicellograptus ornatus biozones, in descending order. The P. pacificus Biozone consists of three subzones, which, from highest to lowest, are the Diceratograptus mirus, Tangyagraptus typicus, and an unnamed lower subzone. Data for the P. pacificus Biozone are presented first for each subzone and then for the full biozone, undivided, which is then followed by data for the underlying D. ornatus Biozone.

The rest of the table consists of three blocks of information, all arranged in columns with a datum (or dash when data are missing) in each biostratigraphically labeled row. In the following description, the rows are identified for simplicity only by the trivial epithet of the biozone or subzone’s species name. Since the beginning of the Vesiculosus Biozone forms the top end of our analyzed time series, we present information only for that datum level.

The left-most data block consists of three columns that present information about the location of the biozones within the ordinal composite constructed by Horizon Annealing (H A). The first two columns (left to right) are, respectively, H A scores and H A ordinal positions. Both values reflect the location of individual samples (horizons) in that sequence, which has a total of 633 horizons and a set of scores that range from zero at the beginning of the ordination to 1.00 at its top. The ordinal position of the base of each biozone corresponds to the first appearance datum (F A D) of the eponymous species in the ordinal sequence. Since Tangyagraptus typicus and many associated species occur only in South China, the base of that sub-biozone and the succeeding Diceratograptus mirus subzone are determined only by the South China samples. Also listed in the third column, following the H A score and ordinal position, is the number of individual horizons (samples) included in each biozone. The data in this block of the table is as follows: vesiculosus 0.963665 610 (blank) acuminatus 0.8499 538 72 ascensus 0.7994 506 32 persculptus 0.5434 344 162 extraordinarius 0.4708 298 46 mirus subzone 0.3460 219 79 typicus subzone 0.1943 123 96 lower pacificus subzone 0.1501 95 28 pacificus undivided 0.1501 95 203 complexus 0.0553 35 60 Thus, the F A D of Dicellograptus complexus has an H A score of 0.0553, occurs as the thirty-fifth sample in the ordinated set, and the biozone includes 60 samples between this F A D and that of P. pacificus at the ninety-fifth ordinal position.

The next (central) block of the table presents estimates of the duration of each of the biostratigraphic units from six published sources that are here organized in six columns from left to right: Cooper et al. (2012), Du et al. (2020), Ling et al. (2020), Lu et al. (2019), Jin et al. (2020), and Zhong et al. (2020). The relatively sparse elements in this section of the table are as follows: vesiculosus (blank) (blank) (blank) (blank) (blank) (blank) acuminatus 0.93 (blank) (blank) (blank) 0.26 (blank) ascensus 0.43 (blank) (blank) (blank) 0.73 (blank) persculptus 0.6 (blank) (blank) 0.52 0.72 0.84 extraordinarius 0.73 (blank) 0.20 1.22 0.55 0.39 mirus (blank) (blank) 0.27 (blank) (blank) 0.27 typicus (blank) (blank) (blank) (blank) (blank) 0.94 lower pacificus subzone (blank) (blank) (blank) (blank) (blank) 0.59 pacificus undivided 1.86 3.7 1.03 1.8 (blank) 1.80 complexus 0.6 (blank) (blank) 0.82 (blank) 1.27

The final data block in this table presents three columns of calculated values for the time-scaled composite. From left to right, they are the median duration in millions of years of the geochronological interval occupied by each of the biostratigraphic units in the time-scaled composite, the average duration (in thousands of years) per ordinal within those intervals, and finally, the modeled age of the beginning of the intervals (in millions of years ago). These calculated values are vesiculosus (blank) (blank) 441.90 acuminatus 0.60 0.826 442.49 ascensus 0.58 1.813 443.07 persculptus 0.66 0.407 443.73 extraordinarius 0.55 1.196 444.28 mirus 0.27 0.342 444.55 typicus 0.94 0.976 445.49 lower pacificus subzone 0.59 2.107 446.08 pacificus undivided 1.80 0.887 446.08 complexus 0.82 1.367 446.90

In the text, we refer to these chronostratigraphic intervals as chrons, again labeled by the eponymous species’ trivial epithet. The quoted average duration per ordinal (interval length divided by number of ordinals in the interval) is then the temporal spacing applied to samples within those intervals prior to grouping (binning) horizons into the sets of 24 analytical intervals (bins), and so also quantifies the temporally variable information density through the sampled time series. Thus, the Complexus Chron has an estimated duration of 0.82 million years, a sample spacing of 1.367 kiloyears, and commences at 446.90 M a. The modeled starting dates of the intervals are simple additive combinations of the median estimated durations for the intervals, aligned in time with the beginning of the Silurian Period (443.07 M a), given in G T S 2020 (Goldman et al., 2020).

2.3 Estimation of Species Turnover Dynamics and Capture-Mark-Recapture Analysis

We employed two related approaches to quantifying species diversity, origination, and extinction rates. The first is the set of metrics (referred to as “face-value metrics” in the following text) advocated by Foote (Reference Foote, Erwin and Wing2000). These metrics are simple to calculate from presence-absence data and provide a relatively unbiased basis for the comparison of macroevolutionary rates and taxonomic diversity based on the fossil record. In this scheme, the chosen occurrence record is taken at face-value (hence the descriptor) and taxa are censused in a bin-by-bin scheme according to which of the bins’ boundaries they cross, as follows. Of the number of taxa that occur within a bin, some are bottom crossers (i.e., are known from older bins) and are symbolized as Nb; of those some will go extinct within the bin (= NbL, for bottom crosser and Last occurrence) and the remainder will pass into younger bins (cross the top boundary, =Nbt). Some of these latter may only be known from bins above and below but are treated as range-through taxa and included in the quantity Nbt. Additionally, some taxa within a bin cross (or are inferred to have crossed) the top of the bin (Nt), and these include species that first appeared (F) within that bin (NFt). Taxa that occur only within one bin (‘singletons’) cross neither bin boundary (NFL). Their number strongly depends upon bin duration and sampling completeness and thus increase the vulnerability of taxonomic diversity and evolutionary rate metrics to sampling artifacts (among other problematic effects; see Foote, Reference Foote, Erwin and Wing2000). Accordingly, we follow Foote’s practice and exclude singletons from our diversity and evolutionary rate calculations. Given these notations, estimated mean standing diversity is calculated as (NbL+NFt+2Nbt)/2 and estimated per capita origination (p̂) and extinction (q̂) rates (respectively) are –ln(Nbt/Nt)/ΔT and –ln(Nbt/Nb)/ΔT, where ΔT is the bin duration. For the sake of convenience, we plot the estimated diversity, origination, and extinction rate values at bin midpoints.

The Diplograptina went extinct in the late Hirnantian and we are unable to report an extinction rate for the bin in which the last known species occurs just as one cannot calculate an extinction rate for the final bin in a set of bins: it requires information that does not exist. Similarly, the Neograptina invaded the paleotropics in the latest Katian (Goldman et al. Reference Goldman, Mitchell and Melchin2011) and we therefore are unable to report an origination rate at that appearance or to distinguish in situ origination from immigration during this early segment of Neograptine resurgence in the paleotropics. Thus, the p̂ and q̂ time series reported from the face-value and CMR analyses for these clades are one bin shorter at both ends than the time series of species diversity with which they are associated in our figures and do not fully capture the timing of their initial immigration or final extirpation due to the logical limitations of binning and the calculations involved.

We calculated mean standing species diversity and per capita rates separately for each of the Late Ordovician to early Silurian graptolite clades (the Diplograptina and the Neograptina) following the systematic treatment of these graptolites given by Štorch et al. (Reference Štorch, Mitchell, Finney and Melchin2011) and Melchin et al. (Reference Melchin, Mitchell, Naczk-Cameron, Junxuan and Loxton2011) as well as for the full set of planktic graptolite species present in this interval. In order to provide additional phylogenetic context for the LOME events, we also counted the number of species appearances and disappearances in each bin for the three constituent subclades of the Diplograptina (the Dicranograptoidea, Diplograptoidea, and Climacograptoidea). We also separated the Neograptina into the clade Retiolitoidea and its subtending stem group, which we refer to as ‘stem-group neograptines,’ namely the Normalograptidae including species of the genus Normalograptus, and all other taxa that root below the common ancestor of the Retiolitoidea sensu Melchin et al. (Reference Melchin, Mitchell, Naczk-Cameron, Junxuan and Loxton2011). The Retiolitoidea is a diverse clade that in the LOME interval was represented overwhelmingly by M. extraordinarius and related species of the paraphyletic Neodiplograptidae (Metabolograptus, Neodiplograptus, Korenograptus, and Paraclimacograptus).

We have calculated the face-value metrics described earlier for each of the three different binning schemes as a rough gauge of the turnover history of graptolites through the LOME and also as a means to assess the role of binning (and its effect on sampling) on the calculated time series. These face-value metrics have a number of shortcomings, however. Most significantly for our present purposes, they do not incorporate information about the probability of sampling taxa through the study interval (Foote Reference Foote2003). If sighting probabilities are very unequal over time or space, or differ among taxa, then the face-value metrics will not capture the macroevolutionary dynamics accurately (Foote Reference Foote, Erwin and Wing2000, Reference Foote2001, Reference Foote2003). For instance, the omission of sighting information from the analyses forces one to assume that observed first and last occurrences represent the actual time of origin or extinction of the taxa. Considering the global sea level fall and related facies changes that are known to have occurred during the Late Ordovician (summarized in the introduction), it is likely that sighting probability was variable through this interval and that this incompleteness may have distorted the record of species losses through the Late Ordovician (Finnegan et al. Reference Finnegan, Heim, Peters and Fischer2012b, Holland & Patzkowsky Reference Holland and Patzkowsky2015, Zimmt et al. Reference Zimmt, Holland, Finnegan and Marshall2021). We consider this effect on the record of graptolite turnover during the LOME in greater detail in the discussion section of the paper.

Capture-Mark-Recapture (CMR) analysis provides a model-based approach that offers a more nuanced reading of the original presence-absence data (reviewed in Liow & Nichols Reference Liow and Nichols2010). CMR was developed for wildlife population assessment and adapts readily to the study of species-level biodiversity. It makes use of maximum likelihood to simultaneously estimate likelihoods of species sighting (pi) as well as parameters known as survival and seniority. Survival (φi) is the probability that a taxon extant in the i-th interval is still extant in the following interval (i+1). Seniority (γi) is the probability that a taxon extant in the i-th interval was also extant in the preceding interval (i–1). Per-interval, per-taxon probabilities of extinction and origination may be derived from these parameters: the probability of extinction is 1–φ, and that of origination is calculated as 1/(1+ γi+1)–1 (Connolly & Miller Reference Connolly and Miller2001). To facilitate their comparison with the estimated per capita origination (p̂) and extinction (q̂) rates described earlier, we divide (or rescale) the per-interval probabilities obtained from our CMR analyses by the same Δt (interval duration for bins) used in those calculations. The resulting values are not rates in the same sense as Foote’s (Reference Foote, Erwin and Wing2000) metrics. The rates p̂ and q̂ are derived based on a continuous process whereas CMR models births and deaths as discrete events, and the two variables do not scale with interval in the same manner. Nonetheless, rescaling the CMR probabilities by interval duration is useful as a means to directly compare the relative magnitudes of extinction and origination determined by these different approaches.

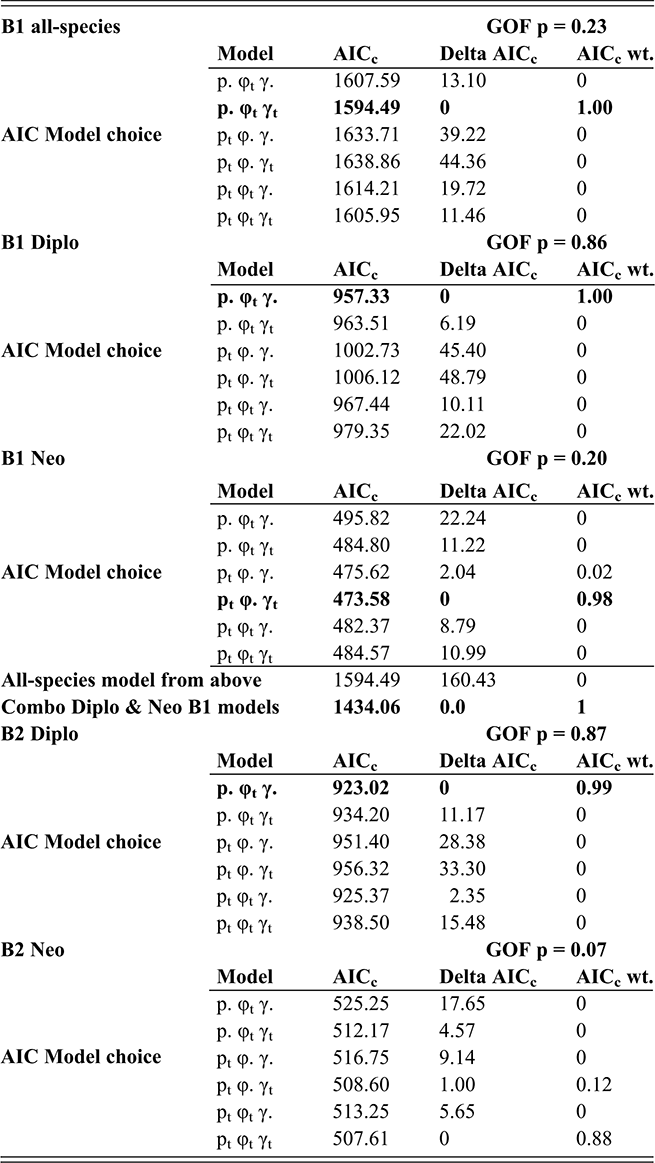

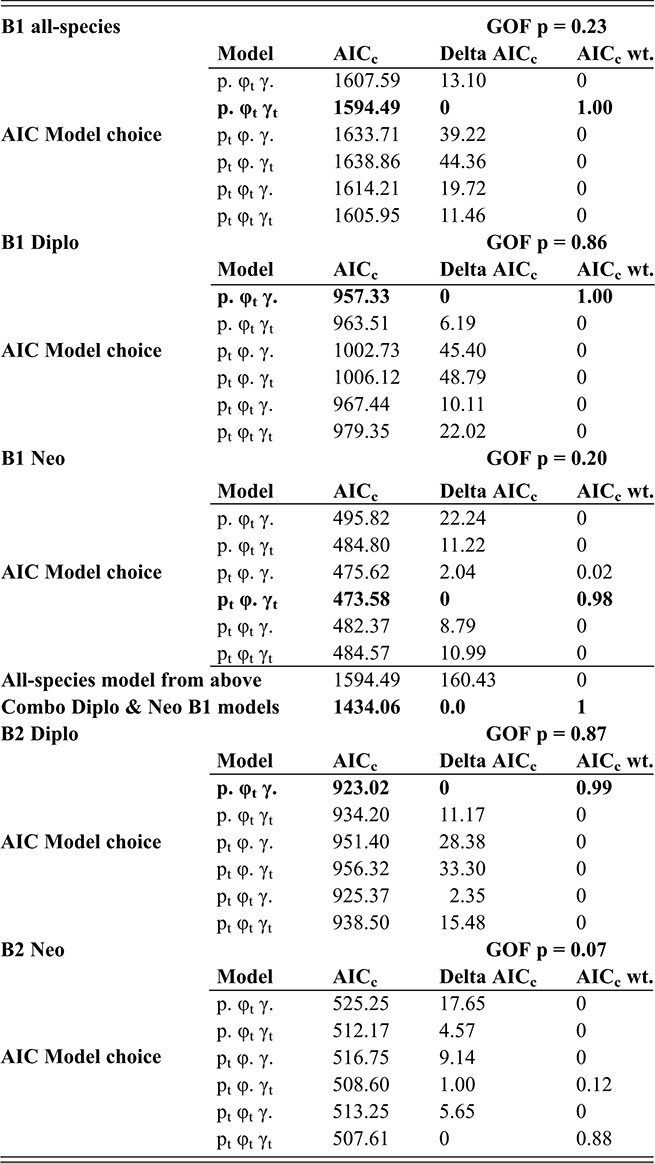

In the present context, it is important to note that the values of p, φ and γ are jointly and simultaneously estimated, using a likelihood function that incorporates all three parameters for each bin; variations in sighting (p) affect estimates of φ and γ for the same interval. Accordingly, CMR takes into consideration evidence for changes in sighting as part of the model fitting process. We employed the program FITMAN, written by one of us (HDS), to carry out the CMR analyses. A full accounting of the behavior and application of this method is given in Chen Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Melchin, Sheets, Mitchell and Jun-xuan2005b) and in Liow and Nichols (Reference Liow and Nichols2010). Like the program MARK (Cooch & White Reference Cooch and White2019), FITMAN generates a series of models that are ranked based on Akaike’s Information Criterion (Akaike Reference Akaike, Petrov and Csaki1973, Burnham & Anderson Reference Burnham and Anderson1998), which balances data fit and model simplicity. Model ranking is expressed as the “relative AIC weight,” and sums to 1.00 over the set of models compared. We utilized a set of models that range from maximally simple (p, φ, and γ are fixed over all intervals) to the maximally complex (all three parameters vary throughout the time series), as well as various intermediate combinations of parameters that were fixed or fully variable over time. Thus, we test explicitly whether the data indicate that sighting probability varied significantly through the interval of the LOME and affected estimates of E and O. Finally, because the species diversity in our dataset is relatively small, we employ the more appropriate, sample-size-adjusted version of AIC (AICc) (see Burnham & Anderson, Reference Burnham and Anderson1998).

An additional feature of FITMAN is that it allows us to conduct a goodness-of-fit (GOF) test to ascertain whether the most complex model under consideration adequately describes the observed data. The observed deviance in the fitted model is compared to the distribution of the deviance values obtained from a series of Monte Carlo simulations in which the fitted model is used as a generating model. While this process is not perfect, it does allow detection of situations in which the model is missing substantial features of the original dataset, a method described by Pradel (1996). Among the critical model expectations is the requirement that all taxa have similar dynamical properties, which is essential since CMR employs the entire dataset to obtain singular estimates of pi, φi, and γi for each interval. In the present case, we expected a priori (as described in the Introduction section) that the dynamical histories of the Diplograptina and Neograptina were distinctly different and therefore we conducted CMR modeling for each clade separately as well as in combination. We examined these three CMR models (all species combined, and the two species sets separated by clade) for the B1 and B2 binning schemes. Because CMR models require equal duration sampling intervals, the B3 set was inappropriate for this method and so we did not conduct CMR analyses of that dataset.

FITMAN employs nonparametric bootstrapping to numerically determine 95 percent confidence intervals (CI) around the parameter estimates for each bin. These CIs were estimated from parameter distributions obtained by resampling the original distribution of extinctions and originations within intervals to form 100 bootstrap sets.

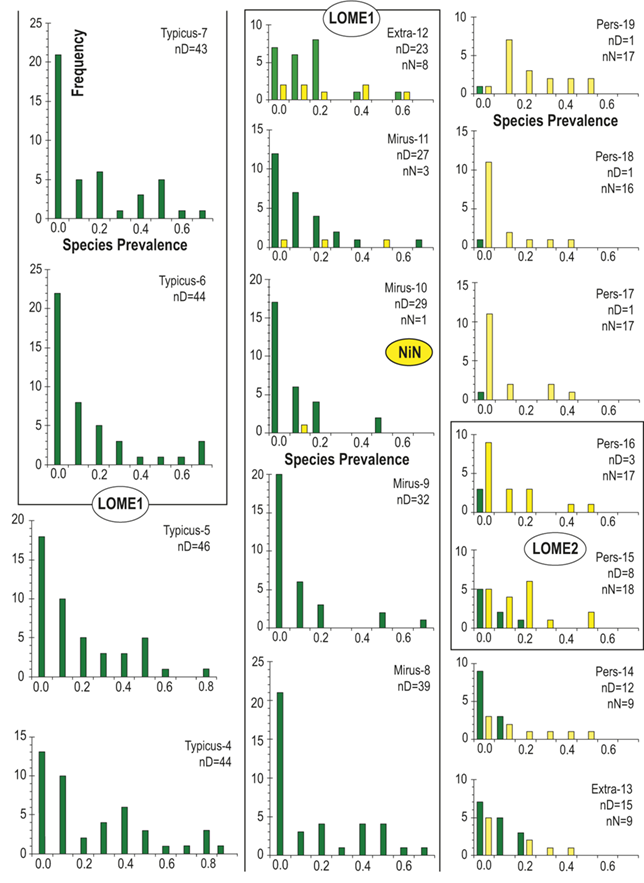

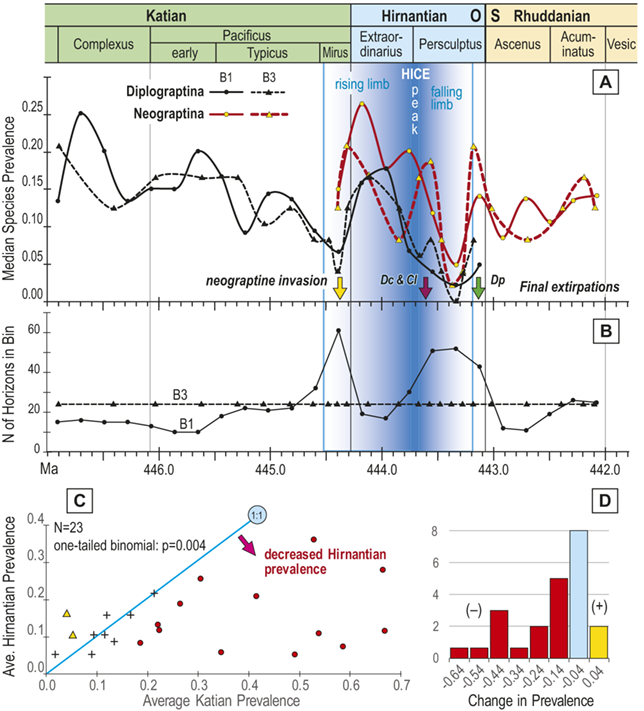

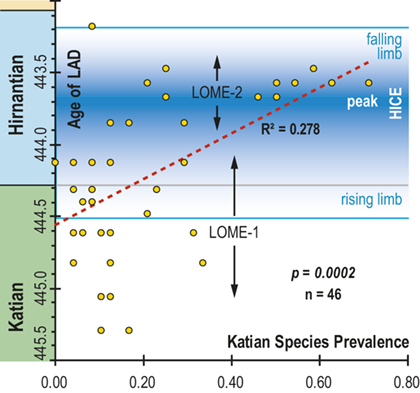

2.4 Species Prevalence

Lastly, in addition to the per-bin estimates of sighting probability (pi) obtained from FITMAN, we made use of the fact that the binned horizons in our HA composite retain a record of all the occurrences of each individual species through the study interval. This feature allows us to assess the prevalence of each species in each bin, bin by bin. By species prevalence (sp) we mean the proportion of horizons in a bin that contain a record of the species. We calculate a value of this metric for each species during every one of the bins within the species’ inferred temporal range. Thus, for each species there is a time series of sp values that correspond to the interval in which it was extant. Similarly, for each bin there is a set of sp values representing the set of species that were extant during that time interval. As with the boundary-crosser metrics, we omitted from this analysis species that are confined to single bins.

Previous work has demonstrated that graptolite communities experienced substantial changes in community structure and species’ relative abundances in the interval leading into the LOME (Sheets et al. Reference Sheets, Mitchell and Melchin2016) and suggest that such changes may have presaged the mass extinction itself. Species prevalence offers a related measure, in this case gathered from the present global dataset, which we compared to species turnover and sighting rates to gain additional insights into the driving forces behind the LOME.

3 Results

3.1 Face-Value Turnover Metrics

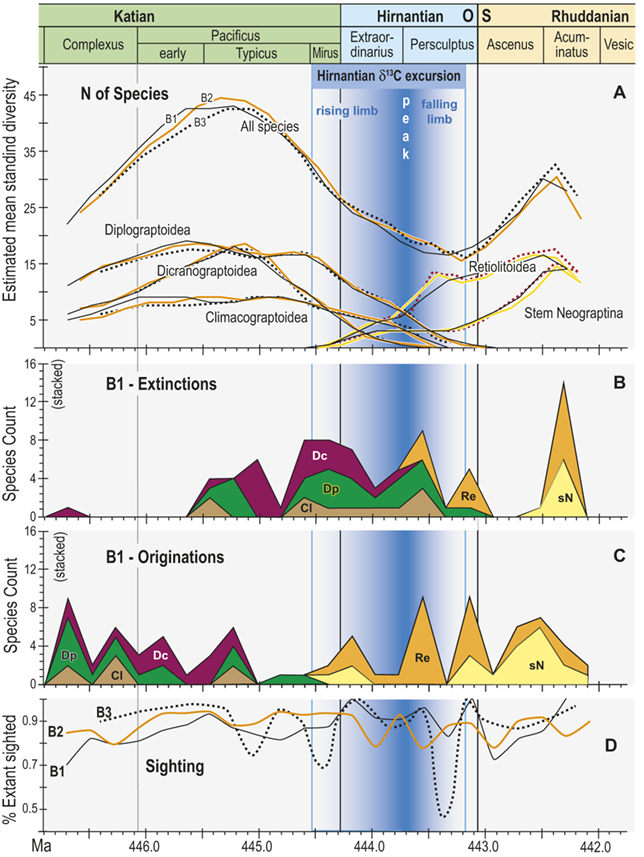

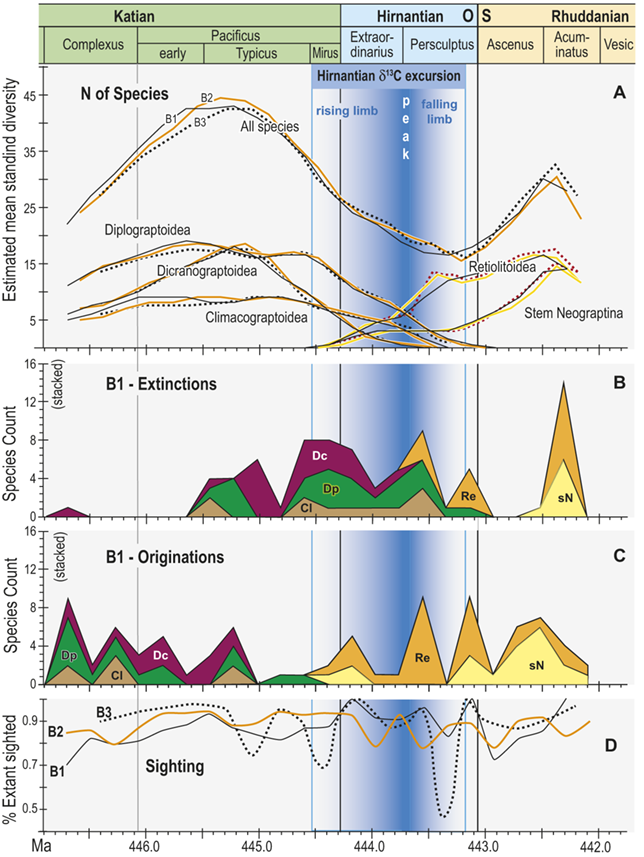

Trajectories of species richness (estimated mean standing diversity, EMSD) obtained by the face-value boundary crosser metrics from three binning schemes are each very similar to one another (Fig. 5A) and differ greatly between the Diplograptina and Neograptina as well as among their subclades (Fig. 5B). Consistent with the finding of Goldman et al. (Reference Goldman, Mitchell and Melchin2011), the Neograptina are entirely absent from our samples prior to their appearance in the paleotropics during the Mirus Subchron near the end of the Katian Age. The peak in graptolite diversity that occurred during the Typicus Subchron within the Pacificus Chron consisted entirely of diplograptines (EMSD = 42.5 – 44.5, depending on the binning treatment); predominantly species of the Diplograptiodea and the Dicranograptiodea (see also Sadler et al. Reference Sadler, Cooper and Melchin2011, Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Sadler, Munnecke and Crampton2014, Crampton et al. Reference Crampton, Cooper, Sadler and Foote2016). Climacograptoids had a relatively low and steady diversity (7.5–9 species) until late in the Pacificus Chron when they and the other two subclades began their decline toward final extinction. Crampton et al. (Reference Crampton, Cooper, Sadler and Foote2016) noted that the LOME preferentially affected long-lived species to a greater degree than was the case during other times in the Ordovician, and this feature is reflected in our analysis as well: almost no diplograptines went extinct during the > 2 myr-long Complexus to early Pacificus interval that preceded the onset of the LOME (Fig. 5B). Similarly, except for a brief surge in the number of dicranograptoid species originations during the early Pacificus and Typicus subchrons, the number of diplograptine originations (Fig. 5 C) peaked early in the same pre-LOME interval in which there were nearly no observed extinctions. Diplograptine originations declined to zero by the start of the HICE in the latest Katian, just as the number of extinctions began to rise and the neograptines appeared in the paleotropics.

Figure 5 Observed diversity dynamics of planktic graptolite species through late Katian to early Rhuddanian chronozones and relative to the span of the HICE (as in Fig. 4). A, Estimated mean standing diversity in binning schemes B1–B3 for all graptolite species present through the study interval taken together, alongside those of the three constituent subclades within the Diplograptina: the Dicranograptoidea (Dc), Diplograptoidea (Dp) and Climacograptoidea (Cl), and two subgroups within the Neograptina: stem-group Neograptina (sN) and Retiolitoidea (Re). Note that variation among results from B1–B3 is small relative to the large changes in species diversity and to the differences in those changes in diplograptine versus neograptine subclades. B, Stacked plot of the number of species extinctions within B1 bins by subclade. C, as in B but for species originations. High numbers of diplograptine species extinctions preceded the beginning of the HICE and the invasion of the paleotropics by neograptine species, which subsequently diversified while diplograptines went extinct over the course of the Hirnantian and earliest Rhuddanian. D, Time series of approximate per species sighting probabilities (proportion of observed, extant species recovered in bin) for each binning scheme; values are somewhat variable but are similar among binning schemes. Values show no long-term trend and those in the mass extinction interval (Mirus + Hirnantian bins) are not significantly different from nonextinction interval values; overall the sighting probabilities average 0.88 ± 0.22 (95 percent CI). Cl: Climacograptoidea; Dc: Dicranograptoidea; Di: Diplograptoidea; sN: stem neograptines; Re: Retiolitoidea.

Figure 5Long description

A. Estimated mean standing diversity in binning schemes B1 to B3 for all graptolite species present through the study interval taken together, alongside those of the three constituent subclades within the Diplograptina: the Dicranograptoidea (D c), Diplograptoidea (D p), and Climacograptoidea (C l), and two subgroups within the Neograptina: stem-group Neograptina (s N) and Retiolitoidea (R e). Variation among results from B1 to B3 is small relative to the large changes in species diversity and to the differences in those changes in diplograptine versus neograptine subclades. Diversity of the diplograptine clade and subclades all peaked during the early part of the Typicus Subchron, irrespective of binning scheme, following which they decline monotonically to final extirpation in the early to mid Persculptus Chron. The Dicranograptoidea increased sharply to a peak of about 19 species in the early part of the study interval and also declined quickly with final extinction at about 444.45 M a whereas the Diplograptoidea (also with about 19 species) and Climacograptoidea (peak diversity: 10 species) declined more slowly with the latter going extinct at about the same time as the Dicranograptoidea and the former persisting to a final extinction late in the Persculptus Chron, at about 444.0 M a. At the same time as the Diplograptina show extended diversity decline, the Neograptina exhibit a steady increase in diversity beginning with their immigration late in the Mirus Subchron synchronously with the early part of the HICE rising limb,

B. Stacked plot of the number of species extinctions within B1 bins by subclade. Species extinctions among the Diplograptina are strongly concentrated in the interval from early Typicus Subchron through the early part of the Extraordinarius Chron, with a second concentration of losses among Climacograptoidea and Diplograptoidea in the mid Persculptus Chron, contemporaneous with the falling limb of the H I C E. There are nearly no extinctions among this clade in the earlier part of the study interval, and species loss among the Neograptina is concentrated in the mid to late Persculptus Chron. A large peak in apparent losses in the Neo clade in the Acuminatus Chron is an artifact of incomplete sampling at the end of the time series.

C. Stacked plot of the number of species originations within B1 bins by subclade. Diplograptine clades show numerous species originations in the Complexus Chron and early in the Pacificus Chron, and none thereafter except for a very few continuing among the Dicranograptoidea into the Mirus Subchron when the Neograptina appear and add many species through the course of the Hirnantian, returning total graptolite diversity to values nearly equal those prior to the mass extinction.

D. Time series of approximate per species sighting probabilities (proportion of observed, extant species recovered in bin) for each binning scheme; values are somewhat variable but are similar among binning schemes, show no long-term trend and values in the mass extinction interval (Mirus plus Hirnantian) are not significantly different from non-extinction interval values; overall the sighting probabilities average 0.88 plusminus 0.22 (95% C I).

The appearance of neograptines during the Mirus Subchron slightly precedes the onset of the HICE in our scaled ordination and manifests as a pulse of species appearances among both the stem-neograptines and the Retiolitoidea within the latest Katian and early Hirnantian. Previous biogeographic analyses suggest that the appearance of Neograptina in the paleotropics at this moment represents an immigration event from mid- to high-latitude regions (Goldman et al. Reference Goldman, Mitchell and Melchin2011). This immigration event coincides in our analyses with the largest number of diplograptine species extinctions recorded during the Late Ordovician (Fig. 5B,C). It is this dramatic disappearance of diplograptine species (and the consequent change in the composition of graptolite and other species assemblages) around the start of the Hirnantian Age that is commonly identified as the first pulse of the LOME. We will return to a discussion of the nature of that event later.

The mean standing diversity values for the graptolite clade as a whole fell to 17.5–15.5 species near the end of the Persculptus Chron; an approximately 62 percent loss of species diversity. The Neograptina diversified during the LOME and became the most specious clade concomitantly with the onset of the postglacial flooding event early in the Persculptus Chron, only some 600 kyr after their initial invasion of the paleotropics. By the early Silurian, in the Acuminatus Chron approximately 1.2 Myr from its nadir, graptolite EMSD had nearly recovered to Katian peak values.

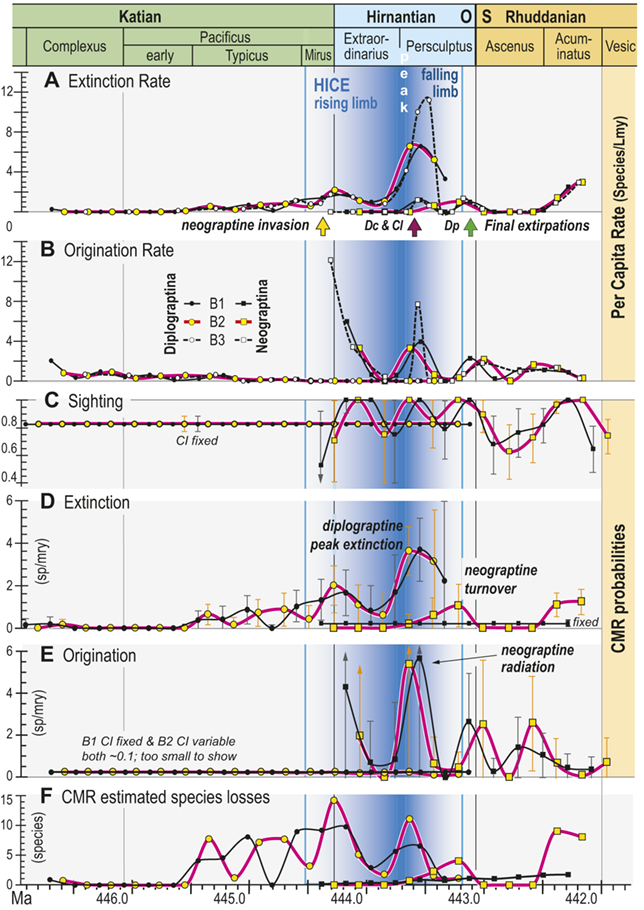

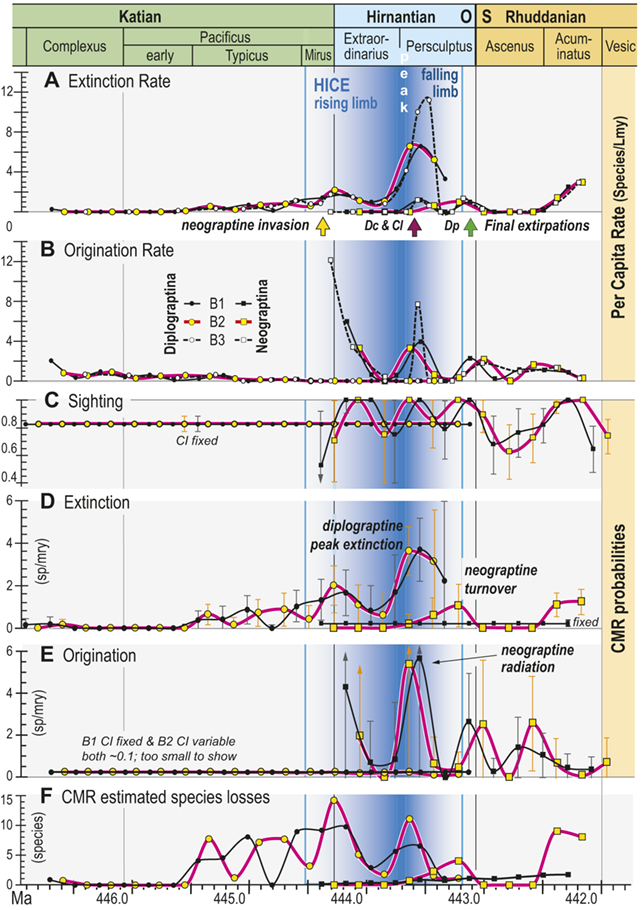

All three of our binning schemes produce essentially the same pattern of change in estimated per capita extinction and origination rates (Fig. 6A,B). Among the Diplograptina rates of origination fall to near zero values by the end of the Typicus Chron while extinction rates slowly rise to a modest peak at the start of the Hirnantian, irrespective of bin boundary placement or whether the bins equalize sampling interval length or the number of horizons in each interval. This general similarity continues through the LOME, with the exception that the very short bin durations in the B3 set through the Katian–Hirnantian transition interval and the postglacial late Persculptus Chron interval produce exceptionally high p̂ values among the Neograptina during both of those intervals (Fig. 6B) as well as an exceptionally high q̂ among the Diplograptina in the late Persculptus Chron (Fig. 6A). The longer durations of the B1 and B2 bins recover similar peaks in the per capita rates but tend to spread them over a broader interval and in some cases shift their timing earlier or later by a half bin. In any case the two clades display strikingly different dynamical histories. This is most notable in the case of the late Persculptus peak rates: Diplograptines experienced high rates of extinction at precisely the same time that Neograptines speciated at high rates.

Figure 6 Time series of per capita and Capture-Mark-Recapture (CMR) model-based estimates of graptolite species turnover dynamics. Species of the clades Diplograptina and Neograptina analyzed separately based on the B1–B3 occurrence records for the per capita rates and the B1 and B2 records for CMR. Timing of neograptine invasion and diplograptine subclade final extinctions shown by arrows along the timeline below A (abbreviations as in Fig. 5). A, Per capita extinction rate (q̂) from B1–B3 data treatments. B, Per capita origination rate (p̂) from B1–B3 data treatments. C, CMR modeled species sighting probabilities (±95 percent bootstrapped CI); sighting rates and CI fixed for both of the highest ranked models of the Diplograptina record and variable for both Neograptina models. D, Extinction rates (±95 percent CI) derived from the highest ranked CMR models; rates time-variant for the Diplograptina in both models and only slightly variable or fixed for the Neograptina. E, Origination rates (±95 percent CI) derived from the highest ranked CMR models; rates fixed or minimally time-variant for the Diplograptina and highly variable for the Neograptina in both models. F, Number of species extinctions in the two clades inferred from the highest ranked B1 and B2 CMR models.

Figure 6Long description

The values identified in the figure explanation as being plotted in the six panels are all provided in Appendix 2, and the general temporal patterns of species turnover illustrated herein are described in the Results and Discussion portions of the text.

In general, the data plotted in this figure show that extinction risk among the Diplograptina as measured by both approaches and in all three binning schemes was near zero during the Complexus and Lower Subzone intervals and then began a slow climb to moderately a value of about 2 species per m y at the beginning of the Hirnantian, which was followed by a brief decline into the later part of the Extraordinarius Chron before climbing again to a yet higher peak of about 4 s p per m y early in the Persculptus Chron, based on the C M R analyses. The per-capita, face value metrics yield a slightly higher peak of nearly 6 s p per m y at that same point in time. Diplograptines went extinct shortly after that peak, following a partial decline. Taking variation in sighting probability into account, C M R estimates that substantial species losses began abruptly during the Typicus Subchron and grew in number only slightly into the early Hirnantian, but as those losses became a larger fraction of the declining diversity, estimated per-species extinction risk increased. The Neograptina exhibit several peaks in origination and extinction, and these peaks correspond in time with those exhibited by the Diplograptina: the largest neograptine probabilities of origination (greater than 5 s p per m y) occurred in the early Persculptus Chron at the same time as the highest peak in risk of extinction among the Diplograptina.

3.2 Capture-Mark-Recapture Models