At the Dawn of History: Original Genius

At the core of the Enlightenment, with its firm belief in the steady, progressive rationalization of human affairs, we also encounter a new preoccupation with the past. What was it that, at the dawn of history, had sparked human civilization, or human civilizations, and launched them on their course of historical progress? Critics such as William Duff (An Essay on Original Geniuses, 1767) and Robert Wood (An Essay on the Original Genius and Writings of Homer, 1776) began to re-read Homer in search of clues, and instead found a conundrum. How could it be that, out of nothing, and without the benefit of having examples to emulate, Homer, primordial poet, could have achieved such an immediate benchmark status from which all classical standards were derived? Where did his ‘original genius’ come from, from whom had he learned his craft? What was there before this literary Big Bang?

In 1720s Naples, an as yet obscure Giambattista Vico had developed a model suggesting that each civilization originated with its own separate ‘Big Bang’. His treatise Scienza nuova argued that, in a concentrated act of self-articulation, societies would burst upon the scene of world history and become civilizations by formulating, all at once, their mythology, legal system and foundational epic texts. The Scienza nuova was an intellectual time bomb: scarcely noticed through most of the eighteenth century, it would became all-important fifty to a hundred years after its appearance. In Vico’s view, the gods of the original mythological pantheon were interchangeable with the mythologized early monarchs of those ancient epics that celebrated their heroic acts at the dawn of recorded history. The idea caught on. In Denmark, for example, the historiographer royal Peter Frederik Suhm approached early Scandinavian history in this way, tracing the descent of medieval rulers from a patriarchal ancestor Odin, raised by his descendants to the ranks of the gods; Suhm saw the Edda (and the sagas of the Edda’s continuation) as the early historical documentation of the Nordic peoples.1

People began to realize, also, that history shows more than one ‘original genius’. After Homer, there were, in modern times, Dante and Shakespeare. This emerging theory of original geniuses, readers will recognize, was a run-up to Hegel’s and Carlyle’s identification of the cultural hero-figure (Chapter 1). But the most important original genius to come to Europe’s attention was discredited by 1800 and is now somewhat obscure: Ossian. It was Ossian who helped detonate Vico’s time bomb. And it was Ossian who allowed every nation in Europe, even peripheral ones, to identify themselves as ancient civilizations, in terms of their own vernacular roots and their own ethnocultural origins.2

An Apparition from the Past

Around 1760, the literate public was dazzled by the rediscovery of Ossian, an original genius now retrieved from oblivion. Ossian, a fourth-century bard who had been active in Caledonia (Scotland) in the darkest Middle Ages, had remembranced the decline of his native heroic society in elegiac dirges in Gaelic (the Celtic language of the Scottish Highlands). These elegies were now scattered across dispersed manuscripts or else remembered orally, as ballads. At the behest of the Edinburgh literati, a fieldworker, James Macpherson, had gathered these scattered oral and manuscript sources and published them in English as Fragments of Ancient Poetry Collected in the Highlands of Scotland (1760). The impact was sensational. Macpherson was charged to inquire further, and in the course of the 1760s he offered his readers the epic cantos he had reconstructed from the fragments into which they had been broken up. The titles were Fingal and Temora. They soon came under a cloud of suspicion and were later dismissed as forgeries; but not until they had enjoyed immense fame for a while as the Northern European counterparts to the Iliad and the Odyssey and had profoundly and lastingly shaken the poetic, the aesthetic and the cultural-historical outlook of literate Europeans.

Ossian was from the outset presented to the reading public as an original genius. The classical mottos on the title pages of the 1760 collection of Fragments of Ancient Poetry and of the 1762 Fingal both highlight the role of the ‘bard’ as the chronicler of the heroic deeds of the nation’s patriarchal ancestors, in the ‘primitive’ Homeric mode.Footnote * Hugh Blair’s Critical Dissertation on the Poems of Ossian, the Son of Fingal (1763) made this the dominant frame in which Ossian was read: Ossian was a voice from the ‘infancy of societies’, like the skaldic bards investigated by Nordic antiquaries. Blair accordingly places him in a northern Celtic/‘Gothic’ tradition. Thenceforth, as Blair’s dissertation was prefixed to every subsequent Ossian edition, Ossian became, proverbially, the ‘Homer of the North’.

This in turn led to a great fission in the self-image of European literature. Madame de Staël’s summation, in her seminal On Literature in its Relations to Social Institutions (1800), is typical: it sees European literature as a dual tradition. One is Mediterranean, classical, rooted in ancient Greece and in the Roman empire; its mainspring is Homer. The other is northern, Romantic, rooted in Ossian. And she extends the dualism further: literature in the Mediterranean–classical tradition is temperamentally sanguine, realistically descriptive, and suited to societies with strong social conventions; whereas literature in the northern–Romantic mode is temperamentally melancholic, metaphysically contemplative, and suited to societies with a strong tradition of individualism. We seen the germ here of that temperamental dualism that later informed Thomas Mann’s ethnotypes, discussed in Chapter 1: the opposition between the superficial French and the contemplative Germans. Ossian is more, then, than a literary curiosity; as a northern Homer, and as figurehead and fountainhead of a non-classical, north European tradition, he triggered a veritable paradigm shift in Europe’s literary and cultural self-awareness.

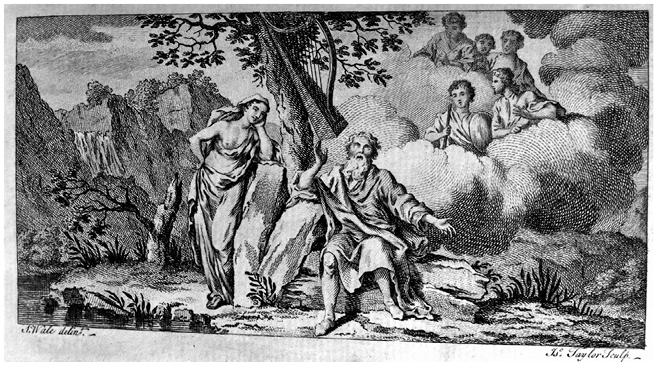

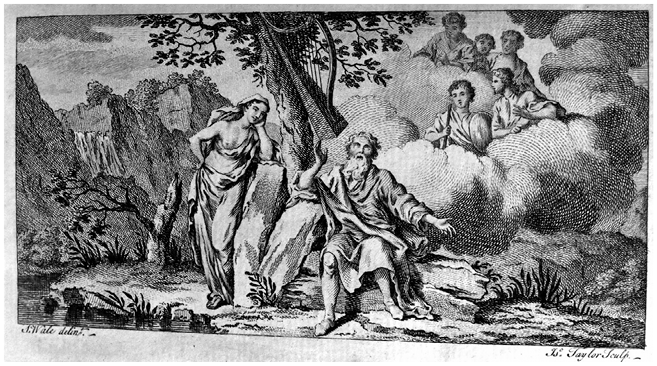

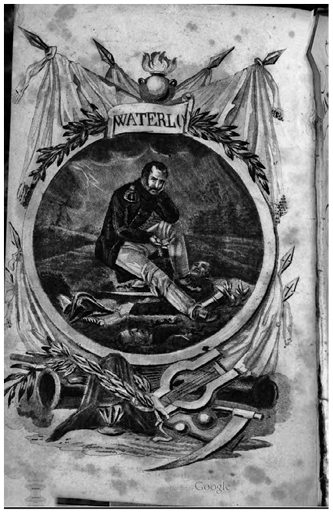

Ossian is even made to look like Homer (or like an Old Testament prophet), in line with his status as a primordial poet-chronicler of the epic Olden Days. His garb from the outset is represented as a crossover between a classical toga and a biblical cloak. His long flowing beard also fits this ‘hoary sage’ role pattern. Indeed, Ossian’s dress code has been iconographically fixed in dozens of paintings and has since then influenced the standard of how we see bards, druids and even wizards: from Merlin to Getafix, Gandalf and Professor Dumbledore. The ‘original genius’ iconography appears as early as the engravings that were used as vignettes for the title page of Fingal (Figure 3.1) and for Melchiorre Cesarotti’s Italian edition of the Poesie di Ossian (1763), itself the source for many other European translations.3

Figure 3.1 Title-page vignette for James Macpherson’s Fingal (2nd ed., 1762, engraving by Wale and Taylor).

What is depicted in Figure 3.1 is the scene of Ossian’s last elegy, the mournful culmination of a doleful series. The ageing bard, close to death, is alone on a windswept heath, with craggy mountains in the background. His harp, hung in a tree in an overt echo of Psalm 137, is set humming by the wind blowing through it. In a reverie he senses the presence of the ghosts of the past playing upon its strings with invisible fingers. He beholds the fair Malvina, daughter of Toscar, and Toscar himself, and all the other dead heroes of the past in a spectral apparition. Ossian addresses them:

I am alone at Lutha: my voice is like the last sound of the wind, when it forsakes the woods. But Ossian shall not be long alone, he sees the mist that shall receive his ghost. He beholds the mist that shall form his robe, when he appears on his hills. … The dark wave of the lake resounds. Bends there not a tree from Mora with its branches bare? It bends, son of Alpin, in the rustling blast. My harp hangs on a blasted branch. The sound of its firings is mournful. – Does the wind touch thee, O harp, or is it some passing ghost! – It is the hand of Malvina! … The aged oak bends over the stream. It sighs with all its moss. The withered fern whistles near, and mixes, as it waves, with Ossian’s hair. … The blast of the north opens thy gates, O king, and I behold thee sitting on mist, dimly gleaming in all thine arms. Thy form now is not the terror of the valiant: but like a watery cloud; when we see the stars behind it with their weeping eyes. … Beside the stone of Mora I shall fall asleep. The winds whistling in my grey hair, shall not waken me. – Depart on thy wings, O wind: thou canst not disturb the rest of the bard. The night is long, but his eyes are heavy; depart, thou rustling blast.4

This fey, spooky scene strongly affected the wig-wearing literati of the 1760s. Goethe translated this piece to include it in his Sorrows of Young Werther (1774), the book that is said to have triggered a wave of copycat suicides; and there are good reasons why this of all scenes was chosen to be the title-page vignette and ‘brand image’ for the entire work.

It is no exaggeration to say that in this fragment, we see the germ of what was to explode across Europe as the Romantic movement. The main effects of Ossian, which we will survey in what follows, were twofold: the idea of visionary inspiration; and the turn towards vernacular, nativist historicism in cultural and national consciousness. As we shall see, both of these made themselves felt, not only in literary culture (‘Romanticism’) and in scholarship, but also in public opinion (‘Romantic nationalism’).

Sublime Liminality and Visionary Inspiration

Ossian’s awesome and oppressive setting is one of the strongest manifestations of a new aesthetic that had been developing in the preceding decades. People no longer appreciated only the Beautiful, the locus amoenus, the park-like landscapes of Tuscany with their gentle, pleasurable aspect; what was now beginning to emerge was an alternative mode of appreciating the world, one well outside the comfort zone of the Beautiful. Austere mountain ranges, thunderstorms at night, battlefields, stormy seas, dark forests and craggy coastlines – places that would be the opposite of pleasant or pleasurable, that impress and awe onlookers with their unforgiving grandeur and render them aware of their vulnerability and mortality. This ‘pleasure mixed with horror’ was now identified as (a neologism) the Sublime. Edmund Burke had juxtaposed the two, the Sublime and the Beautiful, in a youthful essay in 1745, and Ossian – as we can see from the fragment quoted here – laid it on with a trowel.5 The Sublime, thus turbocharged, would dominate the aesthetics of Romanticism and would also inform the nascent genre of the Gothic. When we shiver pleasurably in our cinema seats or on our sofa at the sight of Dracula’s bat-circled castle in the eerie moonlight, we are following a tradition that started in 1760.

It was not just the external setting that proved influential: it was the way in which the setting sets the scene. The sublime landscape is also liminal – by which I mean that we are in a shadow zone between two worlds, a threshold (for that is the Latin root meaning of limen) full of ambiguities both spatial and ontological. The liminality effect, too, is used unstintingly. In space, the setting is between light and darkness (moonlight at night) and between heaven and earth (a mountain top under a lowering sky). Ontologically, we are between the embodied, material world of the living and the ghostly, spectral world of the dead. And it is in this liminal situation that Ossian, himself scarcely alive any more and aware of his impending death, and in a dreamlike reverie between consciousness and unconsciousness, summons from the spirit world the presence of the dead, passing on their memories to future generations who might otherwise forget. The strongest manifestation of that communication between the living and the dead is the ghostly sound of the harp, set vibrating either by the wind or by the spectral fingers of dead heroes.

This, too, was to be a seminal influence on the slowly forming poetics of Romanticism. The Romantic poets saw themselves as highly sensitive souls, attuned to the unspoken emotive charge of the situation, intuiting it and being able to express this intuition and inspiration in words. They saw themselves, their own souls, as Aeolian harps. Hence the constantly reoccurring theme of the breeze or wind that touches the poet or is perceived through waving grass or swaying tree-boughs, and that communicates a sense of transcendence to the sympathetic poet. The word ‘inspiration’ is central to Romanticism, and central to that word is its Latin root, in-spiro, ‘breathing into’, a spir-it infused by blowing air; much as God did when breathing life and a soul into Adam shaped out of clay (Gen. 2:7). And that breeze-borne inspiration would reach the poet very often in liminal situations: on beaches, in moonlight, in mist or fog, at dusk. All that is Ossianic.6

Channelling the Nation

Romantic poets see themselves surrounded by mystery and darkness and use their creative intuition to ‘tune in’ to that. ‘Humanity is surrounded by infinity, by the mystery of divinity and of the world’ – that is how Ludwig Uhland begins his 1807 essay ‘On the Romantic’. This tension-filled juxtaposition of the mundane and the transcendent is one of the most salient and all-pervasive characteristics of the Romantic generation of lyrical poets. Novalis had metaphorically phrased the Romantic oscillation between the humdrum and the sublime as a mathematical operation, analogous to raising a figure’s exponent to a higher power by squaring it (in German: potenzieren, so that 4 becomes 16) or logarithmically bringing it down to its root integer (in German: logarithmisieren, so that 25 becomes 5). As Novalis wrote,

Romanticizing something is to raise it to a higher power. The lower self becomes its higher self, much as we ourselves are such an exponential succession. … If I give the everyday a higher sense, give the well-known a mysterious aspect, vest the familiar with the dignity of the unfamiliar, then I romanticize it; and conversely so, when I logarithmically bring down the higher, unknown, mystical and infinite into a common expression.

The poetics of ‘inspiration’, both in Wordsworth’s Preface to the Lyrical Ballads and among his German contemporaries, are well known as one of the salient features of Romanticism. Poetry (and art in general) can, in this romantic view, electrify the world, potenzieren; enchanting and enrapturing it, as poetry itself results from enchantment and rapturous inspiration.7

This constant habit of potenzieren is the hallmark of Romantic idealism, its tendency towards epiphany: seeing reality in terms of its underlying essential principles, its Platonic ideas. The skylark apostrophized by Shelley is not an actual bird but a manifestation of the spirit of soaring creativity: ‘Hail to thee, blithe spirit! Bird thou never wert.’ When Wordsworth hears a Highland reaping-woman sing, or Keats a nightingale, those songs immediately become transcendent, generalized into a spirit of enchantment far beyond the time and place of the specific setting.

Ossianic manticism feeds into a Romantic revival of Platonic idealism, manifested also in the philosophy of Hegel, which loomed large over the entire following century. Hegel’s influence has been seen as politically pernicious by thinkers as different as Karl Popper (who aligns Plato, Hegel and Marx in his The Open Society and its Enemies, 1945) and Peter Viereck (Metapolitics, 1941). That alignment, while suggestive, is not unproblematic, and in any case it cannot be wholly derived from the after-effects of Ossianic poetics. Nonetheless, Ossian’s poetics of visionary inspiration did leave a specific political legacy. The power Ossian ascribed, in the teeth of Enlightenment rationalism, to poetic intuition and to non-cerebral rapture survived into the nineteenth century.

The poetics of visionary and creative power gave a new collective, ‘national’ authority to poets, artists and those who created from visionary inspiration. Their public personas developed from what Shelley called ‘the unacknowledged legislators of mankind’ into figures who, having the power of being inspired, also had the power to inspire others: the prophetic voices of the nation’s needs and aspirations. Victor Hugo would proclaim ‘The Poet’s Function’ in 1840:

The power to intuit the deeper meaning of things behind their appearance became a Romantic habit of epiphany. Michelet and Carlyle use it constantly. At every turn, concrete historical events or occurrences would be represented in terms of what they really stood for: the spirit of France, the principle of Liberty or Chaos. Michelet defines the French Revolution as ‘the advent of Law, the resurrection of Right, the response of Justice’ (‘l’avènement de la Loi, la résurrection du Droit, la réaction de la Justice’). Carlyle sees ‘The Great Man [as] a Force of Nature’. We also see it applied to the way people begin to see the relationship between state and nation. The state is the material expression, the nation its informing, essential quiddity.

The French Revolution had unleashed a torrent of turgid, swollen political rhetoric and grandstanding upon the world – all the new politicians grandiosely modelling themselves upon the orators and heroes of ancient history; and Napoleon himself, notoriously, carried a pocket edition of Ossian with him on his campaigns. (He also carried a lot of other stuff around with him, including a zinc bathtub, and Ossian’s sonorous dirges may have been used as a night-time soporific.) When Prussia had been reduced to a French puppet state, it was the intellectuals and poets (Arndt, Fichte, the Grimm brothers, Görres) who campaigned for a national resurrection. Typically, the resurrection was initially spiritual (cultural, literary, philosophical, moral: unpolitical) and was only in the second instance state-oriented. Finally, general Gneisenau urged king Friedrich Wilhelm III him to arm his subjects, form militias, and harness the force of public opinion. Friedrich Wilhelm dismissed this as a fictitious pipe dream, ‘mere poetry’, at which Gneisenau retorted that poetry was an indispensable and underrated force in social relations; ‘the future of the throne is based upon poetry’.9

That, in the event, was what ensued. In March 1813 Friedrich Wilhelm issued his manifesto An mein Volk, militias were formed in which the ageing philosopher Fichte and the young poet Theodor Körner volunteered, and at Leipzig in October that year the earlier defeats of Jena and Austerlitz were reversed. Napoleon, weakened by his Russian campaign, was vanquished and sent to Elba. Napoleon himself had intuited something like this, sensing the power of literature, when in 1807 he kept his implacable critic Madame de Staël banned from Paris, telling her to stick to her knitting; because in her salon, she could ‘make politics by talking literature, morality, arts, anything’.10

Prussia’s national mobilization of 1813, driven by poets and literati and accompanied by a great deal of patriotic verse, left its own ‘long tail’ of cultural memory.11 It was celebrated for the next 150 years as the glorious moment of national harmony between intellectuals, monarchs and generals and the active involvement of the Volk in the destiny of the state. Young Theodor Körner died of his wounds; as a martyr-poet, he became a role model for all young poets who would become the saviours of their nation henceforth. A line from his poem was so memorable that it was quoted in Berlin’s sports palace in 1943 when Goebbels declared total war: ‘Then, Volk, arise, and storm, break loose!’12

Pre-1914, Körner had inspired poets everywhere in Europe. His biography, written by his father, was translated into many European languages; the English one (1827, dedicated to Prince Albert) was noticed especially in Ireland. Alessandro Manzoni dedicated an ode to him; Irish Romantics translated him, and Lydia Koidula adapted a play by him into Estonian. The type of the ‘national poet’ emerged in his wake. Many of these are now cherished canonical figures: Petőfi, Mickiewicz, Thomas Davis, even (in the European colonies of Cuba and Bengal) José Martí and Rabindranath Tagore. Poets, dealing lyrically with intimate affects, now became public figures. When Ireland’s poet-critic Thomas Davis died at a young age in 1846, his fellow poet Samuel Ferguson wrote a ‘Lament for Thomas Davis’ (1847) that glorified him as nation-builder, sowing the seeds of a future harvest, and as the nation’s prophet (foreteller, forerunner):

The Voice of the Nation

Lyrical poetry (i.e. emotion-centred and driven by visionary inspiration) became a prominent vehicle for the expression and propagation of national ideals after 1800. The new lyricism was more direct and homelier in its diction than its stately eighteenth-century forerunners: Wordsworth had propagated the use of ‘language really used by men’ as the proper way to express a ‘spontaneous overflow of powerful feeling’ and had turned to the simple, oral-performative metre of the ballad (rum te-tum te-tum te-tum) much as the German poets after Goethe had discovered the simplicity of the Lied. This had the added advantage that such verse could be easily set to music and performed as, indeed, a ballad or a song. Many Romantic ballads and verses in fact owe their popularity not to to the printed page but to vocal performance – as we shall discuss in Chapter 9. Sentimental lyricism became chamber music for domestic use (the Lieder of Schubert, often setting verse by Goethe, or Thomas Moore’s ‘Last Rose of Summer’); while patriotic verse such as Die Wacht am Rhein was performed by choirs as public proclamation.

The long-standing affect of ‘love of the fatherland’ was a popular theme for this generation of poets. Initially it was sentimental, referring merely to the attachment to one’s native place, the pangs of homesickness (or exile, or emigration), and the joy of returning after an absence. Walter Scott’s ‘Breathes There the Man’ set the tone and became a household invocation in the course of the century.

The idea that homesickness is a universal human affect, and that it comes naturally to people to spontaneously love their homeland, meant that an important political conclusion was being drawn from an intimate emotion. In the climate of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars it gained a fresh political edge. Love of the fatherland, from being a general moral virtue, a type of social altruism, now became the stalwart defence of one’s own nation against foreign threats. The poem ‘England and Spain; or, Valour and Patriotism’ (1808) by the seventeen-year-old Felicia Hemans is a case in point, celebrating the two anti-Napoleonic allies and the campaign in which her brother was serving. At the same time, the Romantic climate also meant that poets began to thematize the vernacular diversity of Europe’s cultural geography; ‘national’ in this sense could refer to the local colour specific to different countries. This ‘national’ taste fed the success of Robert Burns in Scotland and inspired the Irish melodies of Thomas Moore. Again, the work of Felicia Hemans, dating largely from the period 1810–1835, is a good example. While some of it is English-patriotic, sometimes in the militaristic and sometimes in the moral mode, her work is equally preoccupied with evocations of the culture of her adopted fatherland of Wales, with Walter-Scott-inspired scenes from Scottish history, with philhellenic celebrations of Greece, and with appreciative solidarity poems about the admirable medieval and modern champions defending the national liberties of Switzerland, Spain and Italy. If a common denominator is to be found here, it lies in the climate of the anti-Napoleonic wars and the post-Napoleonic restoration, linking poetic feeling to the local colour of scenery and historical memories and to the liberation of the nation from tyrants (especially foreign ones). She also wrote verse in praise of Körner; and in her collected works all this was grouped together under the rubric ‘national’.14

In Germany, Ernst Moritz Arndt used the form of the Lied for anti-French propagandistic purposes, militaristic rather than lyrical. Arndt was particularly successful with his song ‘What is the German’s Fatherland?’, which in stanza after stanza asks, rhetorically, whether the German’s fatherland is located here (along the Rhine), there (near the Alps), or somewhere else (the coast). The refrain answers: ‘Nay! That it cannot be, the German’s fatherland is greater than this.’ Finally, the answer is given: it is ‘wherever the German language is spoken. That is must be! That, bold German, you may call yours! That is the German’s fatherland!’ It became Germany’s answer to ‘La Marseillaise’ for a while, and it was particularly popular as a choral anthem; we shall encounter it again in Chapter 6.

No less inspiring across Europe were the songs of Pierre Béranger, who in the restoration climate of the post-Waterloo decades kept a more populist nationalism alive in France. Like the goguettier Émile Debraux, his songs would recall the glorious memories of Napoleon’s great victories, the moments when France stood proud and tall (Figure 3.2). These songs were written in opposition to the oppressive restoration regime of the Bourbons, which demonized the very memory of Napoleon, and both poets spent time in prison over their songs of former national glory. Arndt, too, fell under a political cloud after 1818 as the Metternich regime tightened its censorship and mistrust of ‘demagogues’ grew. But this only enhanced the reputation of Arndt and Béranger as stalwart and courageous defenders of their national glories against the dynastic power of autocratic monarchs.

Figure 3.2 Frontispiece to Emile Debraux’s Chansons nationales (1822).

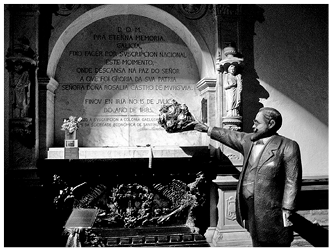

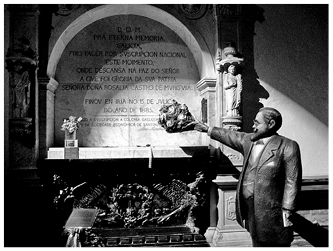

And so the public status of poets could be semi-clandestine, rebellious or state-endorsed (establishment poets such as Tollens in Holland or Oehlenschläger in Denmark). The most ‘Romantic’ ones were those who were persecuted or insurrectionary activists such as the Hungarian Petőfi, the Pole Mickiewicz, the Bulgarian Hristo Botev and the Ukrainian Taras Shevchenko. An in-between category included Felicia Hemans in England, Thomas Davis in Ireland, France Prešeren in Slovenia, Karel Hynek Mácha, Jan Kollár and Ľudovit Štúr in the Czech and Slovak lands, Almeida Garrett in Portugal, Jacint Verdaguer in Catalonia, Guido Gezelle in Flanders, Henrik Wergeland in Norway, Johan Ludvig Runeberg in Finland, Lydia Koidula in Estonia. The topics of their verse could range from the overtly nationalistic, with a deliberate propagandistic intent, to more lyrical effusions whose main nationalistic effect lay in their demonstration that the vernacular language could be used for serious, ambitious literary purposes. Cases in point are the long dramatic poem in Occitan, Mirèio, which earned its author, Frédéric Mistral, the 1904 Nobel Prize (the event depicted in Figure 10.3); and the Galician verse of Rosalía de Castro, whose tomb is shown in Figure 3.3.15

Figure 3.3 Tomb of Rosalía de Castro in the Pantheon of Illustrious Galicians, Santiago de Compostela (sculpture by Jesús Landeira, 1891). The figure offering a bouquet represents her husband, the historian Manuel Murguía.

The Poet as Role Model

Poets themselves adopted a Romantic self-image and became Romantic-nationalist role models. Körner as a soldier-poet was celebrated as a martyr to the national cause both inside and outside Germany, but his type of role model is in fact one of several templates. Three other ‘poetic stances’ besides the soldier-hero-martyr poet (Petőfi, Botev) can be seen, and these may be linked to Byron, Wordsworth and Scott respectively.

Byronism was one of the most pervasive and enduring repercussions of the Romantic movement for European (and indeed global) culture. It was inspired less by Byron’s actual poetry (which is often glibly satirical and if anything classicist in its orientation) than by his poems’ protagonists and indeed his own self-dramatization. The Byronic hero (and Byron himself in his Byronic pose) is a solitary, morose, brooding character, virile but misanthropic, whose capacity for tender feeling has been scarred by bitter experiences. Rick, he of the eponymous café in Casablanca as played by Humphrey Bogart, is probably the most powerful twentieth-century embodiment of a Byronic hero. Haughtily averse to social niceties, he leads a wandering existence and stands apart from the crowd because his ideals are too lofty, his passions too intense and his manners too rough-hewn to fit into modern conventions. Heroes such as Manfred and Childe Harold are of this type, and Byron’s own restless, scandal-ridden wanderings were seen as expressions of this passionate, intriguing (‘Romantic’) character. What appealed especially was that in his anti-bourgeois nonconformism, Byron evinced sympathy for the outlaws and warlords of harsher, non-civic societies and adhered to an honour-and-shame ethos that was disappearing in the modernization process. Thus Byronism glorified the lawless peripheries of Europe, from the Balkans to the Andalusia of Mérimée’s Carmen, and his poetry became the great beacon for a solidarity between the ethos of the cynically Romantic rebel-poet (emulated by the likes of Pushkin, Heine and Prešeren) and the emerging national cultures in Europe’s late-imperial borderlands with their outlaws and brigands (‘klephts’ in Greek, ‘hajduks’ in the Slavic languages). This function was hugely strengthened, of course, by Byron’s active philhellenism and his death in Greece (1824) as a supporter of the anti-Ottoman insurrection there.16

The Wordsworthian stance is that of the inspirational retreat into the idyll of the countryside and proximity to nature. This idyllic lyricism gives a voice to the rural peasantry and creates a conduit from spontaneous folk art into high literature. In national movements whose language was just emerging from the stigmatized register of mere peasant patois into the ambitions of a literate, public-sphere status, such poetry could be a nationalist inspiration (e.g. the Galician verse of Rosalía de Castro or, in the Catalan language, verse by Verdaguer and Teodor Llorente). One lyrical trope that is common to a number of Romantic poets from subaltern cultural communities is that the lost beloved is deified (‘potenziert’) into an inspiring muse-figure or even into a personification of the yearned-for nation: thus with Nikoloz Baratashvili’s conflation of Princess Dadiani and his subjected Georgian homeland, or with Jan Kollár’s Slavy Dcera (‘Daughter of Slava’, 1824), Auguste Brizeux’s Breton Marie (1832) and (through the Kathleen Ní Houlihan trope) W. B. Yeats’s idolatry of the unattainable Maud Gonne.

Walter Scott brought into circulation the role model of the wandering minstrel voicing cultural memories, especially through his popular poem ‘Lay of the Last Minstrel’. It appeared in 1805, just when the cult of Ossian as a ‘bard’ had died out, and provided an alternative Romantic model in its stead (see Chapter 7). It presents an emotional, incident-rich (‘Romantic’) tale of olden days; the frame-setting, however, is that of an Ossianic poet who has outlived the glories of his former days but who can awaken old tales through his rapt inspiration, taking his audience into the fictional world of long-vanished deeds and passions. This, too, was a role model; and the verse of Adam Oehlenschläger and Esaias Tegnér (in Denmark and Sweden) and the cult of ‘troubadours’ and ‘bards’ singing of the nation’s glorious, colourful past cannot be understood without Scott’s post-Ossianic prototype. It also explains why the historical narrative poem maintained great popularity alongside the new genre of the historical novel.17

Thus the register of the Romantic poet is situated between the soldier and the outlaw (Körner and Byron), between the aristocratic past and the contemporary peasant (Scott and Wordsworth). In all cases, the poet enjoys a privileged status as the voice of their nation (or of that nation’s aspirations) and as having, through the power of inspiration, an intuitive understanding of the transcendent principles informing contemporary affairs.

Imagined, Embodied and Affective Communities

Benedict Anderson’s classic Imagined Communities (1983) has given us a powerful template aligning the rise of nationalism (or rather, of the ‘imagined community’ self-defining as a nation) with that of ‘print capitalism’: individuals would, thanks to modern mass-distributed novels and periodicals, become amalgamated into a readership, all readers at the same moment experiencing and being involved in events and narratives that lay far outside their domestic ken. The point stands, but we can add to it. Ann Rigney has shown how mass festivities in numerous Scottish towns around the centenary of Robert Burns (1859) created a sense of national cohesion that was not mediated over long distances by the distribution of printed matter but was experienced in a direct physical co-presence of people: alongside the ‘imagined community’ there was also the ‘embodied community’, and other studies of the festive culture of the nineteenth-century confirm this sense that ‘embodied’ togetherness was as important as its virtual, imagined counterpart. This embodied co-presence specifically appears to have involved the oral or choral performance of lyrical poetry, and often celebrated poets as the common focus of the crowd. The poet could be a cherished historical one, as in the commemorative festivals celebrating Shakespeare, Camões, Dante, Pushkin, Petrarch – the ‘original geniuses’ of their countries’ literary tradition. Or else, specifically in subaltern nations, much more recent memories could be evoked of recent champions of their nation’s literacy and literature: Conscience in Flanders, Mickiewicz in Poland (the statues erected in his honour were torn down by the Nazis and re-erected after the war), Mácha in Prague, Prešeren in Slovenia, Wergeland in Norway, Moore in Ireland, and Schiller in nineteenth-century Germany. In each case, the statues rendered the revered poet a firm presence in the city’s streetscape; but the statue was also a venue for commemorative gatherings, proclamations, cantatas, wreath-layings. That praxis of embodied community-gathering still continues: I saw in pre-COVID Rome how the many Filipino and Filipina domestic workers in that city would gather convivially, on their free Saturday evenings, around the statue of the national hero José Rizal on Piazza Manila, often placing flowers there as a sign of affection and connection. And in the nineteenth century, when freedom of association was not yet the self-evident civil right it is nowadays, the funerals of poets would provide a legitimate occasion for mass demonstrations asserting the nation’s common identity around a shared lyrical core. Such occasions were often redolent with allegorical pathos. At the funeral of the Czech activist writer Karel Havliček Borovský, the poet Božena Němcová laid a wreath in (or on) his coffin; in popular retellings of this event, that wreath was soon mythologized into a crown of thorns, as a mute protest at the dead poet’s prosecution by the Habsburg authorities.18

Such gatherings, and the singing of cherished songs and anthems on public occasions, were a powerful manifestation of a type of literature that did not owe its social outreach to ‘print capitalism’ but that, as Romantic lyric, spoke directly, without mediation, from heart to heart and was performatively reactivated from generation to generation. ‘La Marseillaise’ and ‘Die Wacht am Rhein’ were the tips not of an iceberg but of a sea of heaving and crunching pack ice.