Introduction

Mollusk shells are found on archaeological sites around the world, spanning periods from the palaeolithic to the modern (Allen Reference Allen2017; Bailey Reference Bailey2004; Colonese et al. Reference Colonese, Mannino, Bar-Yosef Mayer, Fa, Finlayson, Lubell and Stiner2011; Erlandson Reference Erlandson1988, Reference Erlandson2001; Gutiérrez-Zugasti et al. Reference Gutiérrez-Zugasti, Andersen, Araújo, Dupont, Milner and Monge-Soares2011; Marean Reference Marean, Bicho, Haws and Davis2011, Reference Marean2014). In Europe and the wider Mediterranean, there is evidence of the use of coastal marine resources, particularly rocky intertidal species, by both Anatomically Modern Humans as well as Neanderthals (Bicho and Haws Reference Bicho and Haws2008; Cortes Sanchez et al. Reference Cortés-Sánchez, Morales-Muñiz, Simón-Vallejo, Lozano-Francisco, Vera-Peláez, Finlayson, Rodríguez-Vidal, Delgado-Huertas, Jiménez-Espejo, Martínez-Ruiz, Martínez-Aguirre, Pascual-Granged, Bergadà-Zapata, Gibaja-Bao, Riquelme-Cantal, López-Sáez, Rodrigo-Gámiz, Sakai, Sugisaki, Finlayson, Fa and Bicho2011; Fa et al. Reference Fa, Finlayson, Finlayson, Giles-Pacheo, Rodríguez-Vidal and Guitérrez-López2016; Ramos-Muñoz et al. Reference Ramos-Muñoz, Cantillo-Duarte, Bernal-Casasola, Barrena-Tocino, Domínguez-Bella, Vijande-Vila and Almisas-Cruz2016). It is well established that rocky intertidal zones offered predictable and renewable food sources such as mollusks and crustaceans (Bailey and Milner Reference Bailey, Milner, Antczak and Cipriani2008), that can be harvested by all members of a group, require no specific skills and are relatively inexpensive energetically (Anderson Reference Anderson1981; Fa Reference Fa2008).

In the Mediterranean, work in this area has confirmed the exploitation of marine mollusks during the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic through to the Mesolithic (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Carrión, Fa, Finlayson, Finlayson and Rodríguez-Vidal2008; Colonese et al. Reference Colonese, Mannino, Bar-Yosef Mayer, Fa, Finlayson, Lubell and Stiner2011; Cortes-Sánchez et al. Reference Cortés-Sánchez, Simón-Vallejo, Jiménez-Espejo, Lozano-Francisco, Vera-Peláez, Maestro-González and Morales-Muñiz2019), although the scale of the exploitation during the earlier stages remains unclear, primarily due to biases generated by glacial sea level changes (Bailey and Flemming Reference Bailey and Flemming2008) as well as compounding factors such as lowered productivity and limited tidal ranges reducing available biomass for harvesting (Fa Reference Fa2008). Based on published data, the rocky shore mollusks most commonly collected for consumption are consistently patellid limpets (mainly Patella spp.), trochid topshells (mainly Phorcus spp.) and mussels (mainly Mytilus spp., Perna spp.) (Cortés-Sánchez et al. Reference Cortés-Sánchez, Morales-Muñiz, Simón-Vallejo, Bergadà-Zapata, Delgado-Huertas, López-García, López-Sáez, Lozano-Francisco, Riquelme-Cantal, Roselló-Izquierdo, Sánchez-Marco and Vera-Peláez2008; Fa et al. Reference Fa, Finlayson, Finlayson, Giles-Pacheo, Rodríguez-Vidal and Guitérrez-López2016; Mannino et al. Reference Mannino, Thomas, Crema and Leng2014; Morales-Muñiz and Roselló-Izquierdo Reference Morales-Muñiz, Roselló-Izquierdo, Rick and Erlandson2008; Steele and Álvarez-Fernández Reference Steele, Álvarez-Fernández, Bicho, Haws and Davis2011; Stiner Reference Stiner1999; Stiner et al. Reference Stiner, Bicho, Lindly and Ferring2003).

The transition from the Palaeolithic to the Mesolithic witnessed a further intensification of marine resource use, likely driven by demographic expansion and environmental changes at the end of the Last Glacial Maximum. Along the Mediterranean and eastern Atlantic coasts, the accumulation of large shell middens in Portugal and northern Spain provides evidence of the important role rocky intertidal resources played in human diets during the Mesolithic, reflecting dietary preferences but also suggesting the development of semi-sedentary lifestyles and increased specialization in marine foraging (Araujo Reference Araujo2016; Fa Reference Fa2008; Gutiérrez-Zugasti et al. Reference Gutiérrez-Zugasti, Andersen, Araújo, Dupont, Milner and Monge-Soares2011). The prevalence of marine mollusk shells in prehistoric coastal sites and the many publications stemming from their study therefore underscores their importance as a resource for academic research, one of these uses being a widely available source of material for radiocarbon dating.

However, the use of shells for radiocarbon dating purposes has generally been avoided due to the uncertainties involved with marine reservoir corrections and the possibility, particularly in some species, of old carbon being incorporated into the shell from carbonate substrates (Dye Reference Dye1994; England et al. Reference England, Dyke, Coulthard, McNeely and Aitken2013). Marine reservoir corrections are continually being refined to enable reliable dating, but shells from areas with carbonate geology require further investigation. A previous study by the author (KA) investigated the possibility of 14C offsets from grazing limpets on Irish limestone coasts. Results from Patella vulgata collected live on limestone and volcanic substrates on the coasts of Ireland indicated that the shells were formed in equilibrium with the seawater, with no significant 14C offsets (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Reimer, Beilman and Crow2019). However, there are reported results of older dates from at least one rocky intertidal species (Patella rustica) collected live from rocky shores in Gibraltar (Ferguson et al. Reference Ferguson, Henderson, Fa, Finlayson and Charnley2011; supplementary material). It is conceivable then, that mollusks from this location are affected by the limestone geology of this region or there could be another explanation. The question is whether these offsets are related to species or habitat.

To investigate this, the authors obtained radiocarbon measurements on a range of grazing mollusks collected from Gibraltar limestone locations with additional filter-feeding species as controls. As a result of these measurements, as described below, it was decided that we should collect more individuals of one of the species, Patella rustica, from another location with varied substrates. The mediterranean island of Sardinia was chosen as a suitable location as it has rocky coastlines composed of carbonate and non-carbonate geology in close proximity, thereby minimising inter-site variability in environmental conditions between sampling locations. In addition, stable isotope analysis can provide more information about the formation of the shell, including environmental and metabolic inputs, which could possibly provide an indication of the origin of the offsets (Lécuyer et al. Reference Lécuyer, Hutzler, Amiot, Daux, Grosheny, Otero, Martineau, Fourel, Balter and Reynard2012).

Location background

Gibraltar

The Rock of Gibraltar is a partly overturned klippe of dolomite and limestone, located at the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula and linked by a sandy isthmus to the adjacent Spanish mainland (Bosence et al. Reference Bosence, Wood, Rose and Qing2000; Rose and Rosenbaum Reference Rose and Rosenbaum1991). It has a Mediterranean climate with mild winters and warm summers, but the frequent presence of a banner-cloud caused by the moisture-laden easterly “Levante” winds can generate a particular microclimate with high humidities that helps to buffer it from climate extremes. Given its location at the westernmost entrance to the Mediterranean, the intertidal organisms inhabiting Gibraltar shores are typical of the Mediterranean rocky coastline with some Atlantic influence (Fa et al. Reference Fa, García-Gómez, García Adiego, Sánchez Moyano, Estacio Gil and García-Gómez2000; Ros et al. Reference Ros, Romero, Ballesteros, Gili and Margalef1985).

Sardinia

The Italian island of Sardinia has a complex geological history (Barca and Cherchi Reference Barca and Cherchi2002; Carmignani et al. Reference Carmignani, Oggiano, Funedda, Conti and Pasci2015; Fancello et al. Reference Fancello, Columbu, Cruciani, Dulcetta and Franceschelli2022), comprising a range of both sedimentary and igneous rock types. Its climate is also Mediterranean, but with greater seasonal variability than Gibraltar, i.e. comparatively hotter summers and cooler winters, and with less rainfall overall. The intertidal fauna occupying its rocky coasts is very similar to that found in Gibraltar, without the Atlantic signal.

Species included in the study

Out of a number of rocky intertidal grazers present on Gibraltar shores the following patellid limpet species were targeted, all of which have been found in archaeological deposits, indicating their collection for consumption by humans:

-

Patella rustica, inhabiting the upper shore and feeding by foraging when wave action is high (Chelazzi et al. Reference Chelazzi, Della Santina and Santini1994);

-

Patella ferruginea (Gmelin 1791), a protected species collected under a license held by University of Gibraltar, inhabiting and feeding within the middle shore;

-

Patella ulyssiponensis (Gmelin 1791), being less tolerant to desiccation and metabolism at high temperature and therefore inhabiting the lower shore and feeding within that zone during immersion (Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Hartnoll, Kain, Norton, John, Hawkins and Price1992), and

-

Cymbula safianai (Lamarck 1819), a large limpet species that has extended into the western Mediterranean from western Africa, which also inhabits and feeds within the lower shore and shallow subtidal.

One species of grazing topshell, the trochid Phorcus turbinatus, which occupies and feeds within the middle to lower shores, was also collected for analysis. For comparison, two species of sessile filter-feeding mytilid mussels were sampled to provide a baseline: Mytilus galloprovincialis Lamarck, 1819, and Perna perna (Linnaeus 1758), both typical inhabitants of the lower shore. A further two non-molluskan filter-feeding species with external shells, the thoracic cirripeds Pollicipes pollicipes (Gmelin 1791 [in Gmelin 1788–1792]) and Perforatus perforatus (Bruguière 1789) (commonly known as a goose and volcano barnacles, respectively), were also collected from the lower shore.

Methods

Sample collection

Gibraltar

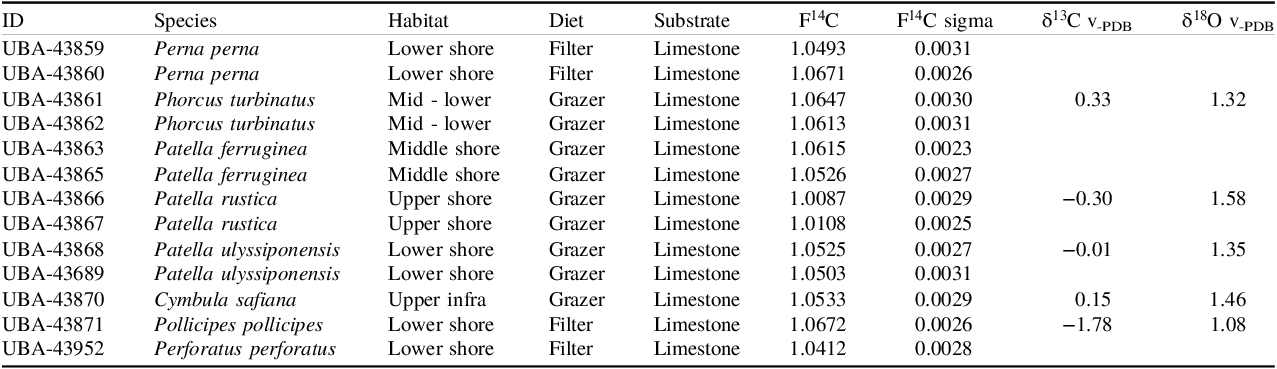

Two individuals each of three species of limpets (P. rustica, P. ferruginea, P. ulyssiponensis), one individual of limpet C. safiana and two individuals each of the topshell P. turbinatus were collected live in June 2020 from intertidal limestone rocks at Rosia Bay, Gibraltar. The location of the sample site is shown in Figure 2. For comparison, samples of mussels (Perna perna) and barnacles (Pollicipes pollicipes, Perforatus perforatus) were also collected, as these are filter-feeding mollusks and should not be affected by substrate type. A full list of samples and corresponding substrate types can be found in Table 1.

Figure 1. Areas of study with respect to the Mediterranean region.

Figure 2. Sampling locations in Gibraltar and Sardinia.

Table 1. Lab ID, Genus and species, habitat, diet, F14C (1 sigma uncertainty), δ13C and δ18O for shells from Gibraltar

Sardinia

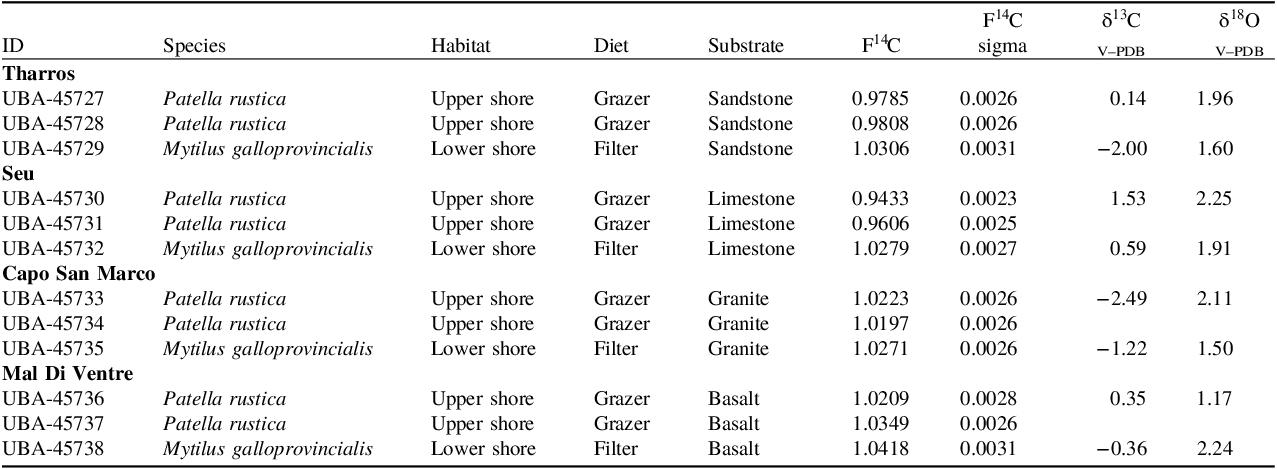

Two individuals each of P. rustica and several individuals of the mussel M. galloprovincialis were collected from four sites with different geological substrates on Sardinia in March 2021. The locations of the sample sites are shown in Figure 2, namely Tharros (carbonate-rich sandstone), Seu (limestone), Capo San Marco (granite), and Mal di Ventre (basalt). A full list of samples and corresponding substrate types can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. Lab ID, Genus and species, habitat, diet, F14C (1 sigma uncertainty), δ13C and δ18O for mollusk shells from Sardinia

Radiocarbon analyses

Mollusks were heated in Milli-Q® water until the flesh easily separated from the shell. The outer layer of the shell was removed mechanically using a diamond wheel on a rotary tool. A subsample (∼100 mg) of each shell, taken from the outer rings, was etched in 1% HCl (2 mL per 100 mg) overnight to remove any remaining surface carbonates, rinsed five times with Milli-Q® water, dried overnight at 70 °C, and coarsely ground with a mortar and pestle. Approximately 12 mg of each pretreated shell was weighed into 4 mL Exetainer® vials (LabCo. Inc.), evacuated, injected with 1.5 mL of concentrated (85%) phosphoric acid to hydrolyze the shell to CO2, and heated at 80 °C for 20 min or until all bubbling ceased.

Samples were converted to graphite on an iron catalyst using the hydrogen reduction method (Vogel et al. Reference Vogel, Southon and Nelson1987) and the 14C/12C ratio and 13C/12C were measured by accelerator mass spectrometry at the 14CHRONO Centre, Queen’s University Belfast, on an Ionplus Mini Carbon Dating System (MICADAS). The radiocarbon age and one standard deviation were calculated using the Libby half-life of 5568 years following the conventions of Stuiver and Polach (Reference Stuiver and Polach1977). The ages were corrected for isotope fractionation using the AMS measured δ13C (not given) which accounts for both natural and machine fractionation. 14C data are reported as F14C (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Brown and Reimer2004).

Stable isotope analyses

Powdered subsamples of a selection of shells from Gibraltar and Sardinia were sent to Iso-Analytical Limited (Crewe, England) for carbon and oxygen stable isotope analysis in September 2021. Iso-Analytical carried out δ13C and δ18O analysis by liberating CO2 from finely ground shell powder using phosphoric acid. The liberated CO2 was then analyzed by Continuous Flow-Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (CF-IRMS) on a Europa Scientific 20-20 IRMS. The subsamples had not been selected from individual growth rings and, therefore, will not represent a specific season or year of growth. Results are given relative to v-PDB standards. Following the method of Szpak et al. (Reference Szpak, Metcalfe and Macdonald2017), the total analytical uncertainty was estimated to be ± 0.15‰ for δ13C and ± 0.19‰ for δ18O.

Results

Radiocarbon analyses

Gibraltar

The F14C results for the Gibraltar samples are shown in Table 1 and Figure 3. While there is some variation between species and individuals of the same species, there is a marked difference in the F14C values for Patella rustica compared to all the other species. Species other than P. rustica, regardless of taxon or feeding strategy, have F14C values of 1.04–1.07, whereas P. rustica exhibits depleted (for modern marine samples) F14C values of 1.01.

Figure 3. Radiocarbon (F14C) measurements on multiple species collected in Gibraltar. Green indicates filter feeding species, yellow indicates grazing species.

Sardinia

The F14C results for the Sardinia samples are shown in Table 2 and Figure 4. Again, there is some variation between individuals but a noticeable depletion in F14C for P. rustica from the limestone and carbonate sandstone sampling locations. The M. gallprovincialis samples from all substrate locations have F14C values of 1.02–1.04, which should reflect the F14C values of the seawater and can, therefore, be a proxy of expected values. P. rustica from the limestone and sandstone locations have F14C values of 0.94–0.98, which is significantly depleted from expected values. P. rustica from the granite sampling locations have F14C values more similar to M. gallprovincialis whereas from the basalt location one of the P. rustica samples is more depleted than both the M. gallprovincialis and the other P. rustica.

Figure 4. Radiocarbon (F14C) measurements on P. rustica and M. galloprovincialis individuals collected in Sardinia from multiple substrates.

Stable isotope analyses

Gibraltar

The δ13C values of the grazing species are all within measurement uncertainty with an average value of 0.09‰, whereas the δ13C value for P. pollicipes has a much lower value of −1.78‰ (Figure 5). The δ18O values of the grazing species are similarly tightly grouped within measurement uncertainty with an average value of 1.39‰ (Figure 5). The δ18O value for P. pollicipes has a lower value of 1.08‰ (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Stable isotope (δ13C and δ18O) measurements on selected species from Gibraltar.

Sardinia

The δ13C values for the P. rustica samples from the four locations are widely scattered (Figure 6). There is no agreement in δ18O values between the two species, P. rustica and M. galloprovincialis, at the same location or between the same species at different locations. In three of the four locations, the δ18O values of P. rustica are somewhat more enriched than that of M. galloprovincialis. Otherwise, there is no visible pattern in the carbon and oxygen stable isotopes of these samples.

Figure 6. Stable isotope (δ13C and δ18O) measurements on P. rustica (grazer G) and M. galloprovincialis (filter feeder F) species from Sardinia.

Discussion

The wider results for the initial Gibraltar survey confirm the results obtained by Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Reimer, Beilman and Crow2019) in that apart from the upper shore limpet Patella rustica (see below), there were no significant F14C offsets for grazing marine mollusks on carbonate shores when compared to filter feeders, and that therefore these mollusks could be suitable for carbon dating of archaeological material provided that the appropriate marine reservoir corrections are applied.

The difference in F14C for P. rustica, compared to the other grazing species in Gibraltar, is evident. This result prompted us to investigate P. rustica further, to establish if the carbonate geology was the reason for the offset in this species. Sardinia was chosen as a location where different types of substrate can be found in close proximity and, therefore, similar environmental conditions. The difference in F14C for P. rustica on carbonate substates in Sardinia is striking, suggesting that there is a pathway for uptake of inorganic carbon originating from the substrate in this species. It has been suggested that grazing limpets can directly ingest substrate particles and absorb the inorganic carbon (Dye Reference Dye1994). However, subsequent research has suggested that this is unlikely (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Reimer, Beilman and Crow2019). It is unlikely that P. rustica has a mechanism for directly ingesting geological carbon, as it has a similar digestive system to the other limpet species in the study (Branch Reference Branch, Trueman and Clarke1985; Newell Reference Newell1970; Prusina Reference Prusina2013).

Significant offsets have been observed in land snails grazing on carbonate substrates (Goodfriend and Stipp Reference Goodfriend and Stipp1983; Hill et al. Reference Hill, Reimer, Hunt, Prendergast and Barker2017), but the mechanisms of shell formation are different to those of marine mollusks. Land snails build their shell mainly from respired CO2 and have δ13C values that reflect the terrestrial plants that are consumed (McConnaughey and Gillikin Reference McConnaughey and Gillikin2008). Marine mollusks build their shell mainly from ambient dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) from seawater. The proportion of metabolic carbon (i.e. carbon from dietary sources) in marine shells varies but is typically up to 10% and is from marine sources (Gillikin et al. Reference Gillikin, Lorrain, Bouillon, Willenz and Dehairs2006). There exists the possibility that a build-up of carbonate precipitates caused by acid rain (see e.g. Huang et al. Reference Huang, Fan, Long and Pang2019; Shammas et al. Reference Shammas, Wang, Wang, Hung, Wang and Shammas2020) in high shore levels (which are occasionally sprayed, but rarely covered by seawater), would facilitate a pathway for old carbon to enter those species occupying and grazing on the upper intertidal in limestone coastlines. The precipitates could be formed by acid rain reacting with calcium carbonate to form calcium bicarbonate (Shammas et al. Reference Shammas, Wang, Wang, Hung, Wang and Shammas2020), a more soluble form of carbonate that could potentially be taken up through metabolic pathways. These same precipitates would be regularly washed away by waves and tides lower down the shore and, therefore not be available to lower-shore species.

In Gibraltar, stable isotope analysis indicates that P. rustica has lower (more negative) δ13C than the other species (except from P. pollicipes). The δ13C values for P. pollicipes, a non-molluskan species which feeds by filtering zooplankton, illustrate stable isotopic deviation of a marine species with a zooplankton feeding regime, where the F14C values are unaffected. P. rustica lives on the upper shore in the splash zone. Consequently, this species must withstand long periods of starvation and desiccation during calm seas. However, P. rustica has a slow metabolism and is able to store glycogen for a longer period than species from lower zones (Prusina et al. Reference Prusina, Sarà, De Pirro, Dong, Han, Glamuzina and Williams2014). Studies have shown that the concentration of metabolic carbon is higher when metabolism is slower (Klein et al. Reference Klein, Kyger and Thayer1996). As metabolically driven CO2 is depleted in 13C, shell δ13C is lower. P. rustica feeds almost exclusively on cyanobacteria, which can take up inorganic carbon from the substrate (Price Reference Price2011; Price et al. Reference Price, Maeda, Omata and Badger2002; Prusina et al. Reference Prusina, Peharda, Ezgeta-Balic, Puljas, Glamuzina and Golubic2015). Soluble inorganic carbon produced by rainwater, as described above, could provide an easier pathway for carbon from the substrate to the cyanobacteria, a potential source of old carbon that can be indirectly taken up by P. rustica. Although other species also include cyanobacteria as part of their diet, the concentration of metabolic carbon in other species’ shells may be much lower due to the metabolic processes discussed above.

However, δ13C can be affected by other mechanisms, such as ageing (Lorrain et al. Reference Lorrain, Paulet, Chauvaud, Dunbar, Mucciarone and Fontugne2004) or freshwater input (Gillikin et al. Reference Gillikin, Lorrain, Bouillon, Willenz and Dehairs2006). It has been observed that the metabolism of mollusks becomes slower as they age (Schöne Reference Schöne2008; Sukhotin et al. Reference Sukhotin, Abele and Pörtner2006), resulting in lower δ13C. Freshwater DIC is isotopically lighter than ocean DIC, so the addition of freshwater to the marine environment will result in lower δ13C values. Oxygen isotopes also reflect the environment in which the mollusks live, with respect to seawater salinity and temperature (Gillikin et al. Reference Gillikin, Lorrain, Bouillon, Willenz and Dehairs2006; Guitérrez-Zugasti et al. Reference Guitérrez-Zugasti, Suárez-Revilla, Clarke, Schöne, Bailey and González-Morales2017). δ18O values decrease with lower salinity or temperature, resulting in possible effects at coastal sites. However, although the δ18O results for the one location in Gibraltar are in agreement and the results for the different locations in Sardinia are not, there is no discernible pattern between locations or species in Sardinia or Gibraltar. Gibraltar does not have any significant freshwater outflow; in fact Gibraltar has a paucity of freshwater in general (Rose et al. Reference Rose, Mather, Perez and Mather2004). This would imply that freshwater influence is not a factor in either location. Consequently, there is nothing to suggest an environmental cause for the differences in the P. rustica offsets.

It is worth noting that the species studied by Dye (Reference Dye1994) included Nerita picea and Cellana exarata, which are also gastropods that inhabit the high intertidal and are subjected to extended periods of desiccation and starvation (Gutierrez 2000). There is, therefore, the potential that Dye’s apparent old dates are a result of the same natural processes as P. rustica in Gibraltar and Sardinia. It is possible that all species from the splash zone will exhibit this difference in carbon uptake, especially on carbonate substrate, and that this is caused by a combination of a slow metabolism, possible incorporation of precipitated carbon and an increased diet of cyanobacteria.

Conclusion

It should be noted that this study is preliminary and, as such, the sample size is small. The results, therefore, are indicative only and further measurements are needed for a more robust investigation. However, these preliminary findings indicate that whereas the majority of the selected grazing species do not have a 14C offset, Patella rustica presents an exception, in that it consistently shows depleted 14C in areas of carbonate geology. P. rustica is a species of grazing mollusk that inhabits the splash zone of the upper shore and exhibits biological traits that are different from grazing species that inhabit the other zones. These traits may enable a pathway for geological carbon to be metabolized in P. rustica, allowing “old” carbon to be incorporated into the shell.

The implication of this is that shells from some upper shore species will have a very large uncertainty in their reservoir age and, therefore, are not suitable for radiocarbon dating, especially if they have come from an area of carbonate geology. This is both species and habitat specific as it relates to species that live in the splash zone in locations that experience lengthy periods of high temperatures and low wave action. Indications are that grazing species from lower shore habitats, which experience daily immersion, may be suitable for dating from any substrate and any location.

Further work is needed to confirm the findings of this paper. It is the authors’ intention to obtain more 14C measurements from P. rustica and other upper shore mollusks, as well as from cyanobacteria or other alga at multiple locations. Stable isotope analysis (δ13C and δ18O of shell, δ13C and δ15N of flesh) from P. rustica will also be carried out to determine the metabolic carbon contribution and, therefore, further investigate the possibility of dietary influences. A further larger study of multiple grazing species from multiple intertidal locations would confirm the suitability of grazing mollusks for radiocarbon dating. This larger study would collect enough data to run statistical tests that could corroborate our preliminary findings and identify possible causes for the 14C offsets, as well as identifying any grouping of individuals that may relate to location or environmental-specific variables. The authors hope that, by gathering as much data as possible from as many locations as possible, a clear pattern will emerge from a more robust analysis.

Acknowledgments

Grateful thanks need to go to the various colleagues at various locations who freely gave of their time to collect samples for us: Igor Gutiérrez-Zugasti (University of Cantabria, Spain), Maite Vasquez Luis (Instituto Español de Oceanografía, Mallorca, Balearic Islands, Spain), Marcos Rubal Garcia (University of Porto, Portugal), Esteban Álvarez-Fernández (University of Salamanca, Spain). Special thanks must go to Stefania Coppa (Istituto per lo studio degli Impatti Antropici e Sostenibilità in ambiente marino and Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Sardinia, Italy) and Stephen Warr (Gibraltar Government Department of the Environment, Sustainability Climate Change and Heritage, and University of Gibraltar, Gibraltar).

Thanks also go to Professor Emeritus Paula Reimer and Dr Alex Menez for proof-reading, comments and advice; and also to the reviewers and Associate Editor of Radiocarbon for additional comments and suggestions.

The radiocarbon and stable isotope measurements in this study were partly funded by a Research Grant (2021) from The Prehistoric Society awarded to Kerry Allen. All other project funding was provided by a research grant from the University of Gibraltar awarded to Darren Fa.

Author allocation

KA 50%, DF 50% (DF identified conceptualized the initial study, KA and DF designed the study, DF collected and coordinated field sampling, KA undertook all the experimental analysis, KA and DF wrote the article).