Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused a global disease burden and introduced unprecedented societal and mental health challenges. Meta-analytic studies have indicated an increased prevalence of psychological distress across the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic [Reference Cénat, Farahi, Dalexis, Darius, Bekarkhanechi and Poisson1, Reference Necho, Tsehay, Birkie, Biset and Tadesse2]. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, concerns were raised about vulnerable groups, such as individuals with severe mental illness (SMI) [Reference Holmes, O’Connor, Perry, Tracey, Wessely and Arseneault3]. According to Delespaul et al., SMI is defined as a psychiatric disorder requiring care, and characterized by profound social and societal constraints, which can be both antecedents and consequences of the psychiatric disorder [4]. SMI typically persists over an extended period (at least several years). In terms of mental health classification, the majority of individuals with SMI are diagnosed with chronic psychotic illness, often alongside substance use disorders [4, 5]. Other common diagnoses include bipolar disorders, post-traumatic stress disorders, major depressive disorders, personality disorders, and autism spectrum disorders [5]. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals with SMI faced significant somatic health disparities compared to the general population, including higher rates of obesity, asthma, diabetes, and stroke [Reference De Hert, Correll, Bobes, Cetkovich-Bakmas, Cohen and Asai6]. These disparities increased their vulnerability to COVID-19 infections, complications, hospitalization, and prolonged illness [Reference Nemani, Li, Olfson, Blessing, Razavian and Chen7].

In addition to the physical health risks associated with the COVID-19 virus, numerous studies have investigated changes in psychiatric symptoms in individuals with preexisting psychiatric conditions and SMI [Reference Cénat, Farahi, Dalexis, Darius, Bekarkhanechi and Poisson1, Reference Ahmed, Barnett, Greenburgh, Pemovska, Stefanidou and Lyons8]. However, findings of these studies have been inconsistent. While some studies indicate improvements in depressive symptoms, the effects on anxiety and eating disorders remain mixed, and overall psychopathology showed minimal changes [Reference Ahmed, Barnett, Greenburgh, Pemovska, Stefanidou and Lyons8]. This suggests that the short- and medium-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on this population varies depending on individual differences and contextual factors, including health care organization. Moreover, most studies on mental health impact in patients with preexisting psychiatric conditions mainly focused on psychiatric symptoms, ignoring psychosocial functioning, quality of life (QoL) and societal and personal recovery, as meaningful outcome measures in individuals with SMI. These outcomes encompass physical health, psychological well-being, social relationships, and environmental factors, all contributing to an individual’s overall well-being and leading a fulfilled life [Reference Dell, Long and Mancini9–Reference Slade11]. Assessing psychosocial functioning, societal and personal recovery, and QoL offers a more comprehensive understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on individuals with SMI.

Only a few studies explored psychosocial outcomes, including social participation [Reference Pan, Kok, Eikelenboom, Horsfall, Jörg and Luteijn12], psychosocial burden [Reference Seethaler, Just, Stötzner, Bermpohl and Brandl13], and loneliness [Reference Orhan, Korten, Paans, de Walle, Kupka and van Oppen14] with heterogeneous findings – ranging from negative impacts [Reference Seethaler, Just, Stötzner, Bermpohl and Brandl13, Reference Luciano, Carmassi, Sampogna, Bertelloni, Abbate-Daga and Albert15–Reference Penington, Lennox, Geulayov, Hawton and Tsiachristas17] to no observable changes [Reference Orhan, Korten, Paans, de Walle, Kupka and van Oppen14, Reference Hennigan, McGovern, Plunkett, Costello, McDonald and Hallahan18–Reference Machado, Pinto-Bastos, Ramos, Rodrigues, Louro and Gonçalves20]. These studies, however, were often limited by small sample sizes and focused primarily on the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (up until December 2021), providing limited insight into the broader SMI population. Many studies also targeted specific subgroups, such as individuals with depression and/or anxiety [Reference Pan, Kok, Eikelenboom, Horsfall, Jörg and Luteijn12, Reference Hennigan, McGovern, Plunkett, Costello, McDonald and Hallahan18], older adults with SMI [Reference Seethaler, Just, Stötzner, Bermpohl and Brandl13] or bipolar disorder [Reference Orhan, Korten, Paans, de Walle, Kupka and van Oppen14], and those with eating disorders [Reference Machado, Pinto-Bastos, Ramos, Rodrigues, Louro and Gonçalves20] without considering the diversity within the SMI population. Thus, understanding how factors like age, gender, comorbidities, and treatment histories influenced the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact remains unclear. To bridge this research gap and to enhance our understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic’s long-term effects on individuals with SMI, the current study had two primary research objectives. The first objective was to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental and psychosocial functioning, QoL, and societal and personal recovery during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The second objective was to explore characteristics within the SMI population associated with differences in outcomes across various pandemic periods. To address these research questions, a longitudinal design was employed using data from two distinct Dutch cohorts of individuals with SMI.

Methods

Study design and participants

This naturalistic longitudinal observational cohort study examined adults with SMI across two cohorts from regional mental health care institutions in the Netherlands: Cohort 1 (Altrecht) and Cohort 2 (GGz Breburg). Both institutions collect data as part of routine outcome monitoring (ROM). In Cohort 1, data were collected using the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS) [Reference Wing, Beevor, Curtis, Park, Hadden and Burns21] (Cohort 1A) and the Manchester Short Assessment of QoL (MANSA) [Reference Priebe, Huxley, Knight and Evans22] (Cohort 1B), while Cohort 2 used the Individual Recovery Outcomes Counter (I.ROC) [Reference Monger, Hardie, Ion, Cumming and Henderson23]. Participation in ROM was not mandatory in Cohort 1, with most patients providing HoNOS data through their mental health care provider and a subset completing the MANSA self-assessment, forming two overlapping subgroups (1A and 1B).

Data were extracted from patient records for individuals who met the following eligibility criteria: (a) diagnosis of one or more psychiatric disorders (DSM-5); (b) age ≥ 18 years; (c) chronic symptoms (Cohort 1: long-term mental health care for enduring psychiatric symptoms with problems in daily life functioning; Cohort 2: at least 2 years of treatment); and (d) receiving inpatient or outpatient care between January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2023. The Medical Ethics Committee of East Netherlands confirmed that the study did not fall under the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (Reference number: 2022-16087). Participants consented to the use of their clinical data for research and/or did not object under the opt-out procedure. In Cohort 2, the consent procedure within the participating mental health care institution was modified midway through the study period (2020), shifting from an opt-out approach to an explicit consent requirement. Before 2020, individuals who did not explicitly object to participation in research were included, whereas from 2020 onward, only those who provided explicit consent were enrolled.

Measures

Sociodemographic information

We collected sociodemographic information, including age (at the time of questionnaire administration) and gender. Additional information included the presence of a psychotic spectrum disorder according to DSM-5. Furthermore, we collected treatment duration data at the time of measurement. For Cohort 1, only the current treatment duration was available, while for Cohort 2, we included both current and previous treatment durations. For Cohort 1, additional information included educational attainment (low, middle, and high); employment status (engagement in paid or volunteer work); relationship status (presence or absence of a life partner); migration background (whether the individual originates from a Western or non-Western country); and living arrangements (whether the individual resided in supported housing). For Cohort 2, additional information included the presence of a substance use disorder according to DSM-5 and the number of comorbidities. In addition, some variables (migration background, employment status, and living arrangements) were unavailable in Cohort 2, while others (educational attainment and relationship status) were only available at first treatment enrollment. This limited data prevented their inclusion in the longitudinal analysis. These variables were included in descriptive data but excluded from further analysis.

Mental and psychosocial functioning

The HoNOS assesses mental and psychosocial functioning based on trained clinician ratings (e.g., mental health care nurse, social worker, psychiatrist, or other mental health care staff). It includes 12 items grouped into four subscales: behavioral problems (Items 1–3), impairment (Items 4–5), symptomatology (Items 6–8), and social problems (items 9–12) [Reference Bech, Bille, Schütze, Søndergaard, Waarst and Wiese24]. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale from 0 (no problem) to 4 (severe problem) [Reference Wing, Beevor, Curtis, Park, Hadden and Burns21]. Total scores range from 0 to 48, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity and functional impairment. The HoNOS total score has demonstrated good psychometric properties and is widely used in psychiatric populations (α = 0.59–0.76) [Reference Pirkis, Burgess, Kirk, Dodson, Coombs and Williamson25, Reference Orrell, Yard, Handysides and Schapira26].

Quality of life

The MANSA is a self-assessment tool for measuring QoL in individuals with mental health conditions [Reference Priebe, Huxley, Knight and Evans22]. It includes 12 questions assessing overall QoL and satisfaction across specific domains, such as accommodation; daily activities; health (physical and mental); personal safety; relationships (social, family, and partner); sex life; finances; and life overall. Responses are rated on a 7-point scale from 1 (could not be worse) to 7 (could not be better) [Reference Priebe, Huxley, Knight and Evans22]. Four additional dichotomous items assess close friendships, social contact in the past week, and experiences of being accused or victimized in the past year. The total MANSA score (range: 0–84) reflects overall QoL, with higher scores indicating better outcomes. The MANSA has demonstrated satisfactory construct validity and strong internal consistency (α = 0.81) [Reference Björkman and Svensson27].

Recovery

The I.ROC measures personal and societal recovery through 12 questions spanning four domains: home, opportunities, people, and empowerment. Responses are gathered via clinician-participant dialogue, using illustrated pages with 8–12 keywords for clarity and a 6-point Likert scale. The I.ROC includes two subscales: empowerment (Subscale 1: items 1, 3, 6, 7, 9–12, α [in this population] = 0.90) and vitality and activity (Subscale 2: items 2, 4, 5, 8, α [in this population] = 0.71) [28]. Topics such as life skills, safety, relationships, and self-worth align with the CHIME framework (connectedness, hope, identity, meaning, and empowerment) [Reference Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams and Slade10]. The I.ROC has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including high internal consistency (α= 0.92), test–retest reliability (Intraclass Correlation Coefficient= 0.857), and concurrent validity, correlating significantly with measures of recovery, self-esteem, symptoms, and functioning [Reference Sportel, Aardema, Boonstra, Arends, Rudd and Metz29–Reference Beckers, Koekkoek, Hutschemaekers, Rudd and Tiemens31]. The total I.ROC score (range: 12–72) was used in analyses, with higher scores indicating better recovery outcomes in mental health, societal participation, and personal well-being.

Subgroups used in the analyses

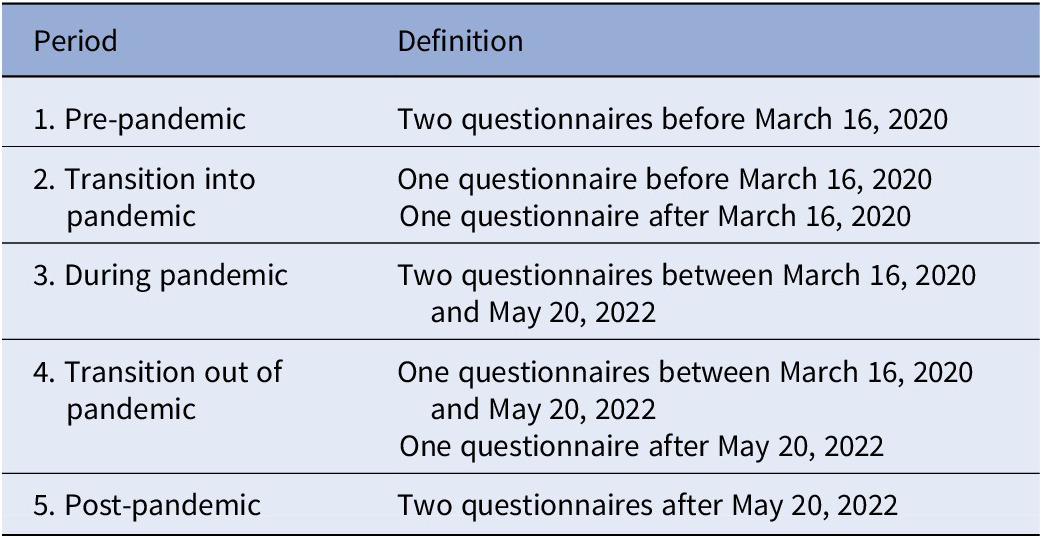

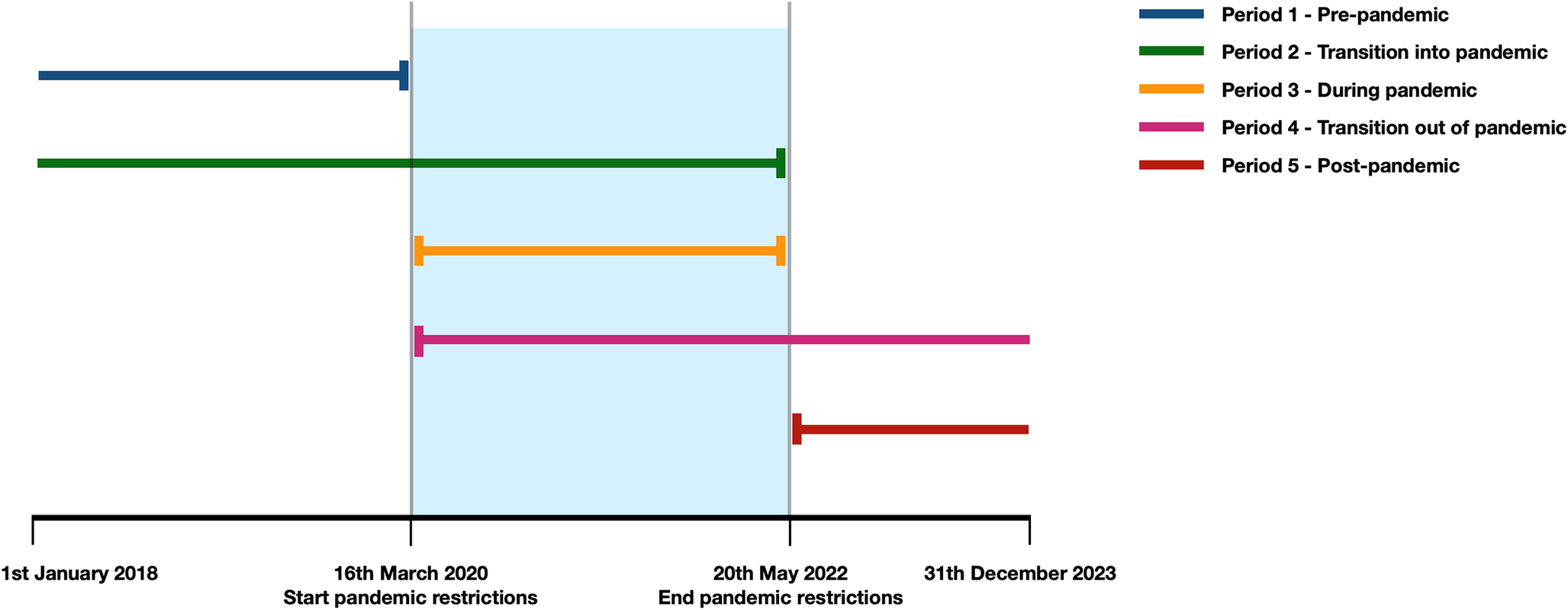

We compared changes in mental and psychosocial functioning (HoNOS, Cohort 1A), QoL (MANSA, Cohort 1B), and societal and personal recovery (I.ROC, Cohort 2) across five COVID-19 pandemic periods: (1) pre-pandemic, (2) transition into the pandemic, (3) during the pandemic, (4) transition out of the pandemic, and (5) post-pandemic (see Table 1 for the definitions of the pandemic periods and Figure 1 for a visual overview of these periods). Data from the questionnaires were included only if there was a minimum 90-day interval between assessments.

Table 1. Overview of definitions of pandemic periods

Figure 1. Visual overview of subgroups used in the analyses. Pre-pandemic = two measurements between January 1, 2018 and March 16, 2020; transition into pandemic = one measurement before March 16, 2020, and one measurement between March 16, 2020 and May 20, 2022; during pandemic = two measurements between March 16, 2020 and May 20, 2020; transition out of pandemic = one measurement between March 16, 2020 and May 20, 2022, and one measurement after May 20, 2022; post-pandemic = two measurements after May 20, 2022.

Statistical analyses

We conducted descriptive analyses for all variables, reporting continuous variables as means and standard deviations (SDs) and categorical variables as percentages. To assess changes over time, we used linear mixed models (LMMs), with separate models for each outcome measure (HoNOS, MANSA, and I.ROC). Delta scores, calculated as the difference between consecutive total scores and representing the improvements in these clinical outcomes, served as the dependent variable. Pandemic period, defined in the “subgroups used in the analyses” section, was included as a fixed effect, while participant was treated as a random effect. Covariates included age, gender, the interval between assessments (in days), and baseline scores. Results were presented as estimated marginal means (EMMs), and outcomes for each pandemic period were compared with the pre-pandemic period (Period 1). For significant findings, post hoc analyses were conducted using separate LMMs for each subscale, employing the same model structure. To explore factors influencing score differences across periods, we performed additional LMMs, incorporating interaction terms between pandemic period and specific demographic or clinical variables (e.g., period × variable of interest). Variables of interest included treatment duration, psychotic spectrum disorder status (Cohorts 1 and 2), and factors such as educational level, relationship status, migration background, employment status, and living arrangements (Cohort 1) or substance use disorder status (Cohort 2). In total, six models (and variations) were analyzed (Supplementary Table 1). Total questionnaire scores were calculated by multiplying the mean score of completed items by the total number of items, excluding measurements with >20% missing data. Missing data in the LMMs were addressed using full information maximum likelihood estimation. Unadjusted p-values were reported, with statistical significance set at 5%. For the primary question, identical analyses were performed on partially overlapping datasets (Cohorts 1A and 1B), with p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons using false discovery rate (FDR) correction. For Cohort 2, no FDR correction was needed due to the single outcome measure. For the secondary question, which examined multiple interaction outcomes, FDR correction was applied to analyses within Cohorts 1A, 1B, and 2. Descriptive analyses were performed in SPSS (version 29.0), and LMMs were analyzed in R (version 4.0) using the “nlme” and “emmeans” packages.

Results

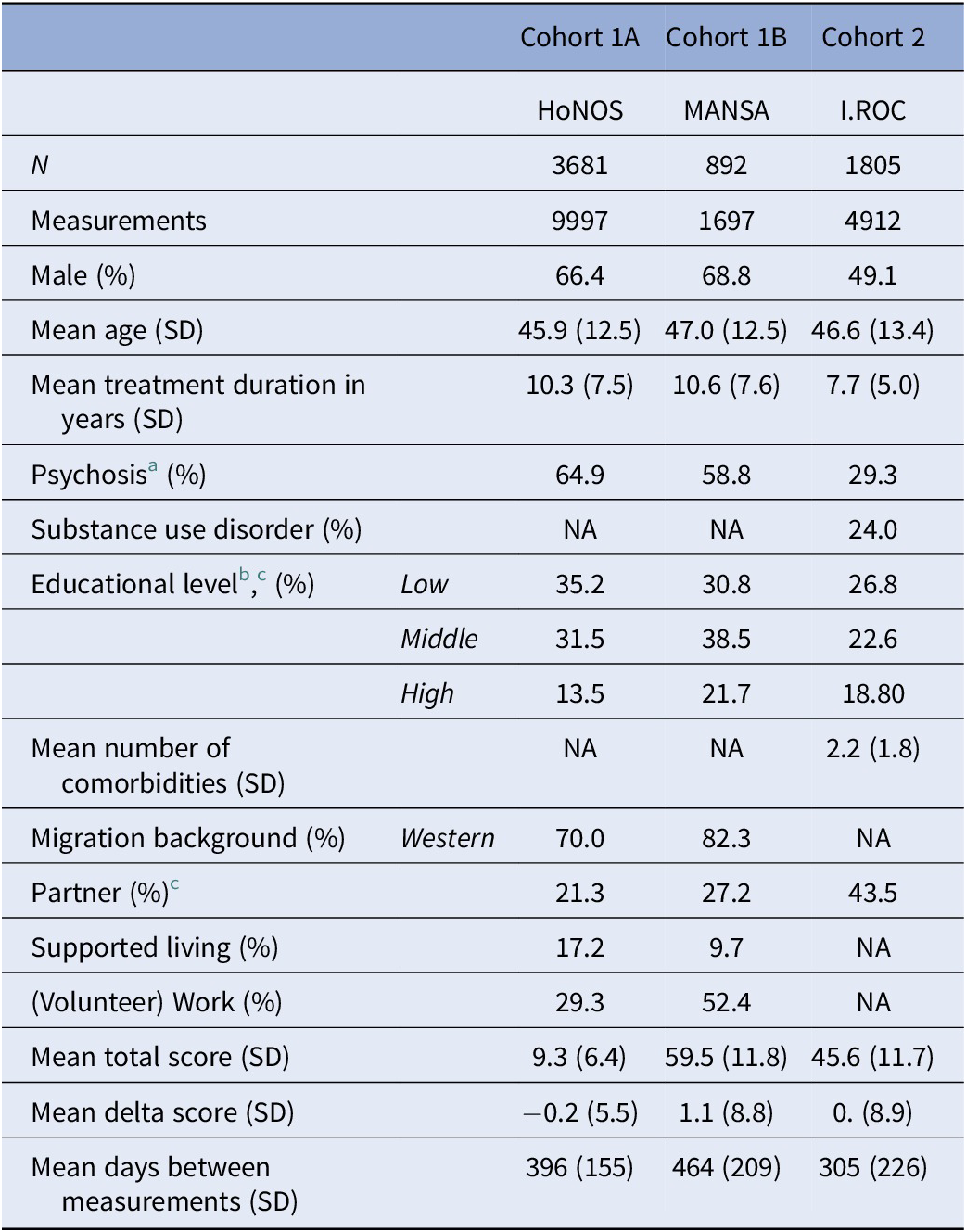

A total of 3681 participants were included in Cohort 1A (HoNOS) (mean age: 45.9, SD = 12.5); 892 in Cohort 1B (MANSA) (mean age: 47.0, SD = 12.5); and 1805 in Cohort 2 (mean age: 46.6, SD = 13.4). In Cohort 1A, 6 individuals (0.2%) opted not to participate, whereas in Cohort 1B, 127 individuals (12.5%) declined to provide consent. In Cohort 2, 2486 individuals (48.56%) did not provide consent. The majority of participants in Cohorts 1A (HoNOS) (66.4%) and 1B (MANSA) (68.8%) were male, while Cohort 2 had a lower male percentage (49.1%). Cohorts 1A and 1B had longer treatment durations, averaging 10.3 years (SD = 7.5) and 10.6 years (SD = 7.6), respectively, compared to Cohort 2 (6.0 years, SD = 7.1). Cohorts 1A and 1B also had higher rates of psychosis spectrum disorders (64.9 and 58.8%, respectively) compared to Cohort 2 (26.2%). Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 2, with further details across pandemic periods in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 2. Study characteristics

Abbreviations: HoNOS; Health of the Nation Outcome Scales, MANSA; Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life, I.ROC; Individual Recovery Outcomes Counter, N;number of participants, NA; not available, SD; standard deviation.

Note: A positive delta score on the MANSA/I.ROC signifies improvement, while a negative delta score on the HoNOS assessment indicates improvement.

a Including schizoid personality disorder, delusional disorder, other specified psychotic disorders, schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, psychotic disorder due to a medical condition with hallucinations, or/and with delusions unspecified psychotic disorder.

b Categorized according to the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics; low: no education to lower secondary education; middle: upper secondary education to vocational training; high: higher education and above [Reference Schneider32].

c Data were only available at the time of first treatment enrollment.

Overall impact

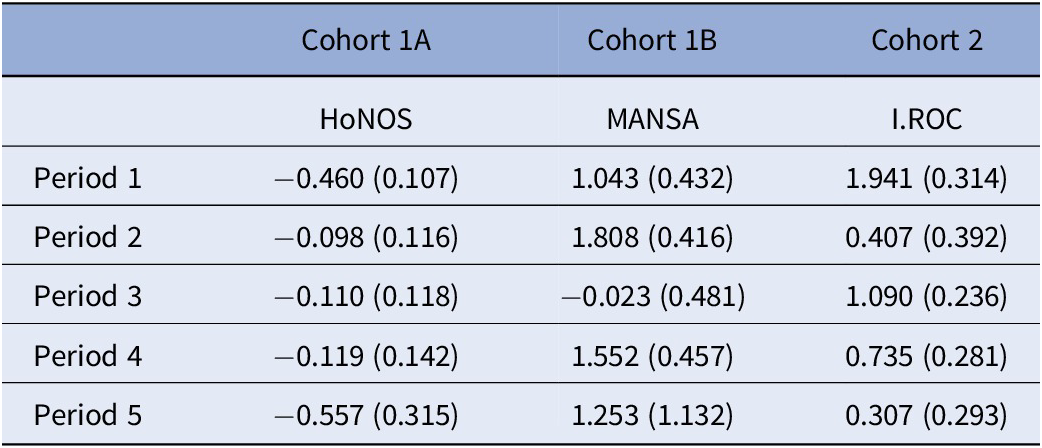

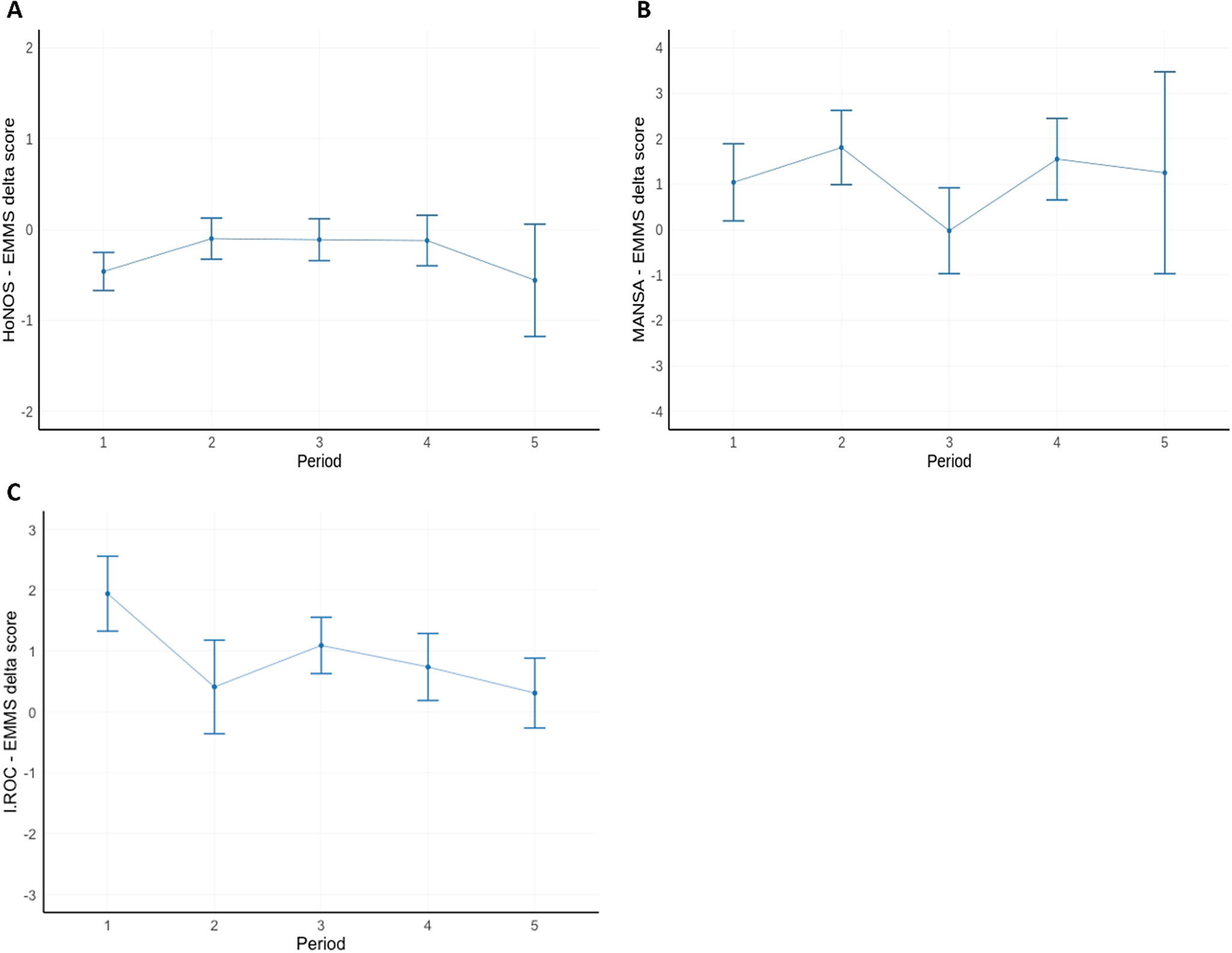

The LMM analyses demonstrated overall improvement in mental and psychosocial functioning, QoL, and societal and personal recovery over time (see Table 3). This trend is reflected in the EMMs, with negative EMMs for HoNOS and positive EMMs for MANSA and I.ROC. After correcting for multiple comparisons, no significant differences were observed on HoNOS or MANSA between Period 1 and subsequent periods. For I.ROC, all periods (Periods 2–5) significantly differed from Period 1 (Period 2: P = 0.002; Period 3: P = 0.034; Period 4: P = 0.004; Period 5: P < 0.001), where Period 1 exhibited the highest levels of personal and societal recovery. Figure 2 visualizes the EMMs across periods. EMMs and SDs for each outcome are available in Table 3, and all detailed statistics are reported in Supplementary Table 3.

Table 3. Change in psychosocial outcomes per period indexed as standardized estimated marginal mean (EMM) change score and standard errors

Note: A positive delta score on the MANSA/I.ROC signifies improvement, while a negative delta score on the HoNOS assessment indicates improvement.

Period 1 = pre-pandemic, Period 2 = transition into pandemic, Period 3 = during pandemic, Period 4 = transition out of pandemic, Period 5 = post-pandemic. HoNOS, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales; I.ROC, Individual Recovery Outcome Counter; MANSA, Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life.

Figure 2. Overview graph of changes in outcome per period indexed as standardized estimated marginal mean (EMM) change score. (A) HoNOS EMMs delta score across pandemic period, (B) MANSA EMMs delta score across pandemic period, and (C) I.ROC EMMs delta scores across pandemic period. A positive delta score on the MANSA/I.ROC signifies improvement, while a negative delta score on the HoNOS assessment indicates improvement. Period 1 = pre-pandemic, Period 2 = transition into pandemic, Period 3 = during pandemic, Period 4 = transition out of pandemic, Period 5 = post-pandemic. HoNOS; Health of the Nation Outcome Scales, I.ROC; Individual Recovery Outcomes Counter, MANSA; Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life.

Transition into the COVID-19 pandemic

During the transition into the COVID-19 pandemic (Period 2), compared to the pre-pandemic period (Period 1) there was a significantly smaller personal and societal recovery (i.e., smaller mean delta score), as measured with the I.ROC (P = 0.002). The mean I.ROC delta score fell from 1.941 points in Period 1 to 0.407 points in Period 2 (on a 12- to 72-point scale). A smaller improvement in mental and psychosocial functioning was noted in the HoNOS (from −0.460 to −0.089 points on a 48-point scale), although this result did not survive corrections for multiple testing (P = 0.023, P adjusted = 0.059). The MANSA showed no significant effects.

During the COVID-19 pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic (Period 3), compared to the pre-pandemic period (Period 1) there was a significantly smaller personal and societal recovery (i.e., smaller mean delta score) as measured with the I.ROC (P = 0.034). The mean I.ROC delta score fell from 1.941 points in Period 1 to 1.090 points in Period 3 (on a 12- to 72-point scale). A smaller improvement in mental and psychosocial functioning was noted using the HoNOS (from −0.460 [Period 1] to −0.110 points [Period 3]), although this did not survive multiple testing corrections (P = 0.022, P adjusted = 0.059). The MANSA showed no significant effects.

Transition out of the COVID-19 pandemic

During the transition out of the pandemic (Period 4), compared to the pre-pandemic period (Period 1) there was a significantly smaller personal and societal recovery (i.e., smaller mean delta score) as measured with the I.ROC (P = 0.004). The mean I.ROC delta score fell from 1.941 points in Period 1 to 0.735 points in Period 4 (on a 12- to 72-point scale). The HoNOS and the MANSA showed no significant effects.

Post-pandemic period

During the post-pandemic period (Period 5), compared to the pre-pandemic period (Period 1) there was a significantly smaller personal and societal recovery (i.e., smaller mean delta score) as measured with the I.ROC (P < 0.001). The mean I.ROC delta score fell from 1.941 points in Period 1 to 0.307 points in Period 5 (on a 12- to 72-point scale). The HoNOS and MANSA showed no significant effects.

Post hoc analyses

Fluctuations in the I.ROC delta score were closely linked to changes in empowerment (Subscale 1) and, to a lesser extent, with vitality and activity (Subscale 2). EMMs for empowerment were 0.612 (P = 0.012) during the transition into the pandemic (Period 2), 0.783 (P = 0.013) during the pandemic (Period 3), 0.408 (P < 0.001) during the transition out of the pandemic (Period 4), and 0.275 (P < 0.001) post pandemic (Period 5). For the HoNOS, impairments (Subscale 2) and social problems (Subscale 4) showed significant deterioration during the transition into the pandemic (Subscale 2: EMM = 0.036, P < 0.001; Subscale 4: EMM = 0.025, P = 0.026). Impairments continued to worsen during the pandemic (EMM = 0.079, P < 0.001) and the transition out of the pandemic (EMM = 0.113, P < 0.001). Detailed statistics and visual representations of the subscale EMMs across pandemic periods are available in Supplementary Tables4a, b and 5a, b, and Figures 2 and 3.

Characteristics linked to outcome scores across time periods

We identified three significant interactions, two between period and psychosis (MANSA, Period 5: P = 0.016, P adjusted = 0.078; I.ROC, Period 2, P = 0.032, P adjusted = 0.105) and one between period and migration background (MANSA, Period 5: P = 0.005, P adjusted = 0.031). After correcting for multiple comparisons, only the interaction between period and migration background retained statistical significance (see Supplementary Tables 6 and 7a–c).

Discussion

This large-scale longitudinal study, conducted in two Dutch cohorts, assessed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental and psychosocial functioning, QoL, and societal and personal recovery in individuals with SMI. Our findings indicate that individuals with SMI demonstrated a trend of improvement across outcome measures despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the rate of improvement was slower during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period, this effect was modest. After correction for multiple comparisons, no significant effects were found for two of the three outcomes.

Societal and personal recovery showed significant but limited changes, with mean delta score improvements decreasing from 1.904 pre-pandemic to a range of 0.307–1.090 (on a 12- to 72-point scale) across other periods. Our secondary objective was to identify characteristics associated with changes in outcomes across the COVID-19 pandemic. While psychosis appeared to influence changes in societal and personal recovery during the transition into the COVID-19 pandemic and QoL during the post-pandemic period, these associations did not remain significant after correcting for multiple comparisons. Similarly, migration background appeared to influence changes in QoL post-pandemic; however, the sample size in Period 5 was too small (N = 8) to draw any conclusions.

Overall, the results suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative but marginal impact on improvements in mental and psychosocial functioning during treatment, as assessed by professionals, as well as on self-reported QoL and societal and personal recovery in individuals with SMI. It is important to note that these findings reflect average effects and do not apply uniformly to all individuals. Considerable individual variability was observed, with some individuals experiencing more pronounced changes than others.

Our finding that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacted psychosocial outcomes in individuals with SMI is consistent with prior research, although the effects vary. Studies comparing pre- and during-pandemic outcomes reported declines in social functioning [Reference Pan, Kok, Eikelenboom, Horsfall, Jörg and Luteijn12, Reference Orhan, Korten, Paans, de Walle, Kupka and van Oppen14], including increased loneliness in adults with depression, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders [Reference Orhan, Korten, Paans, de Walle, Kupka and van Oppen14], and reduced social participation in older individuals with bipolar disorder [Reference Pan, Kok, Eikelenboom, Horsfall, Jörg and Luteijn12].

In contrast, our results showed a slower rate of improvement rather than a decline, likely due to differences in timing and outcome measures. Previous studies, conducted early in the COVID-19 pandemic, primarily captured acute anxiety during a period of heightened anxiety and depression in the general population [Reference van Rijn, Metz, van der Velden, Mathijsen, Swildens and Schellekens33, Reference Simblett, Wilson, Morris, Evans and Mutepua34]. Our study assessed outcomes throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and into the post-pandemic period. Notably, we observed a consistent negative impact across all outcome measures during the transition into the COVID-19 pandemic, aligning with general-population studies that reported increased anxiety and depression in the early phase. In addition, while prior studies focused on immediate impacts like loneliness, our study used long-term indicators of well-being and recovery, which may take more time to change.

The continued improvement, albeit at a slower pace, raises questions about the factors supporting well-being in individuals with SMI during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous qualitative studies among individuals with SMI reported on potential protective factors [Reference van Rijn, Metz, van der Velden, Mathijsen, Swildens and Schellekens33–Reference Burton, McKinlay, Aughterson and Fancourt35]. First, many individuals demonstrated psychological resilience, adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic with adequate coping strategies [Reference van Rijn, Metz, van der Velden, Mathijsen, Swildens and Schellekens33]. Data from quantitative studies further suggest that positive coping mechanisms were associated with reduced negative mental health outcomes in an outpatient cohort during the COVID-19 pandemic [Reference Jones, Ko, Gatto, Kablinger, Sharp and Cooper36]. Second, for some, the COVID-19 pandemic’s societal restrictions had little impact on daily functioning, as low social engagement was already common [Reference van Rijn, Metz, van der Velden, Mathijsen, Swildens and Schellekens33–Reference Burton, McKinlay, Aughterson and Fancourt35]. Finally, the presence of a stable support network – comprising a combination of family, peers, and mental health care professionals – provided continuity and trust in the care system [Reference van Rijn, Metz, van der Velden, Mathijsen, Swildens and Schellekens33–Reference Burton, McKinlay, Aughterson and Fancourt35]. Our current quantitative analysis supports these qualitative findings, particularly concerning the role of stable professional support. Our findings demonstrate that individuals with SMI in treatment showed improvement over a 6-year period, suggesting that care models were sufficient in maintaining positive outcomes during a global pandemic. These findings must be considered in the context of the Dutch healthcare system, where Flexible Assertive Community Treatment teams deliver continuous and multidisciplinary care [Reference Westen, Boyle and Kroon37]. This integrated model may have contributed to the stability observed, distinguishing it from less cohesive systems in some other countries. Future international comparisons should account for these structural differences to better understand how care models facilitate recovery. In addition, further research is necessary to understand the impact of treatment and the factors driving long-term improvements, to better evaluate the effectiveness of care models.

None of the individual characteristics examined in our study – including psychosis and treatment duration (both cohorts), educational level, migration background, partnership status, supported living, and employment (Cohorts 1A and 1B), as well as substance use disorder and comorbidities (Cohort 2) – were significant predictors of recovery outcomes during the pandemic. While migration background initially appeared to influence QoL in the post-pandemic period, this association was not observed in other pandemic periods, and the small sample size of people with a non-Western migration background in Period 5 limited the ability to conclude. The remaining findings were consistent across different cohorts and pandemic periods, clinically suggesting that the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on individuals with SMI was generally marginal, rather than affecting specific subgroups within this population. A possible explanation is that protective factors, such as resilience and support networks, overshadowed the influence of subgroup characteristics. Furthermore, the individual characteristics analyzed at the subgroup level may not fully account for the observed variation, suggesting that the heterogeneity likely arises at the individual rather than the subgroup level. These findings align with prior research, which also did not identify any moderating variables in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic among other psychiatric populations [Reference Zijlmans, Broek, Tieskens, Cahn, Bird and Buitelaar38].

Although the overall stability of outcomes was maintained, our post hoc analyses of the subscales identified specific areas where further refinement of care could potentially contribute to improving long-term outcomes during future crises. Notably, reductions in empowerment were linked to a slower recovery pace, suggesting that interventions promoting autonomy and self-management may be beneficial. In addition, declines in cognitive and physical functioning observed in HoNOS subscales indicate that targeted strategies, such as cognitive rehabilitation and physical therapy, may enhance recovery.

Strengths and limitations

A notable strength of this study is its naturalistic longitudinal design spanning 6 years, enabling a thorough comparison of outcomes for individuals with SMI before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Outcomes were assessed from both clinician (HoNOS) and patient (MANSA and I.ROC) perspectives, providing a comprehensive evaluation. The large sample of clinical data ensures that the findings accurately reflect the natural course of SMI and are highly generalizable to real-world settings. Furthermore, the inclusion of data from multiple institutions enhances the external validity, broadening the applicability of the results across diverse clinical contexts.

This study has several limitations. First, participants with only a single assessment were excluded from the analyses to ensure that changes over time could be evaluated using delta scores. While this strengthened the validity of the longitudinal analyses, it may have introduced selection bias by excluding individuals who dropped out after a single measurement or entered the study later, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings to those with more consistent engagement in care. Second, selection bias may also arise from the voluntary nature of participation in the MANSA assessments. Participants who chose to complete these measures may differ from those who did not, in terms of motivation, engagement with care, or symptom severity, which may limit the representativeness of the sample. In addition, selection bias may have arisen from the mid-study shift in Cohort 2’s consent procedure (2020), from opt-out to explicit consent, potentially altering cohort composition over time. Third, our approach was determined by the availability of specific characteristics and outcome measures within different cohorts, which limited our ability to investigate the same interactions in all cohorts and interrelationships between the various outcome measures (HoNOS, MANSA, and I.ROC). This methodological constraint reflects the pragmatic nature of our data collection in a real-world clinical setting. Fourth, our sample comprised individuals with diverse severe mental disorders without differentiation by specific diagnoses. While this aligns with a recovery-oriented perspective focusing on functional recovery and QoL regardless of diagnosis, we were unable to conduct subgroup analyses by diagnostic categories due to insufficient sample sizes per period. Finally, while multiple comparisons were adjusted, residual confounding cannot be excluded. Factors such as somatic status, variations in care intensity, access to social support, or changes in treatment regimens were not explicitly captured in this study and may have influenced the outcomes observed.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals with SMI continued to show improvements in mental and psychosocial functioning, QoL, and societal and personal recovery during treatment. However, the rate of improvement was slower during the COVID-19 pandemic period than in the years before the pandemic. No particular individual characteristics could be linked to changes in outcomes across time periods. An explanation for these findings may be that the COVID-19 pandemic had a marginal negative impact on mental and psychosocial functioning, QoL, and societal and personal recovery among individuals with SMI; and/or that the COVID-19 pandemic impact was mitigated by stabilizing effects of current Dutch care models.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2025.10039.

Data availability statement

Due to data protection regulations, the raw data from the Routine Outcome Monitoring system are not available for public sharing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the researchers and staff who contributed to data collection and processing, especially J. Luijsterburg, K. Mens, and M. Moerbeek. In addition, the authors extend their gratitude to the following experts-by-lived-experience: M. van Noort and P. Mathijsen for their valuable input during funding applications and their contributions to discussions in research meetings.

Financial support

This study was funded by ZonMW, project number 05-16048-2130001.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.