Climate change is leading to increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events worldwide.Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai and Pirani 1 California is experiencing higher temperatures and altered rainfall patterns related to climate change that are contributing to more severe and widespread wildfires in recent years.Reference Bedsworth, Cayan and Guido 2 Population vulnerability has also increased as more people settle at the wildland-urban interface.Reference Syphard, Radeloff and Keeley 3 , Reference Radeloff, Helmers and Kramer 4 Wildfires threaten health through both the direct exposures to the fire and associated smoke, as well as through secondary effects including critical utility disruptions, widespread evacuations, and resultant interruptions in access to health care.Reference Ebi, Vanos and Baldwin 5 Preparedness efforts must therefore pre-empt potential health care disruptions to mitigate adverse health impacts. This community-based, mixed-methods survey assessed the preparedness, information-needs, and self-reported impacts on health and health care access of a medically at-risk population during one wildfire event, the Oak Fire, in Mariposa County, California. This study sought how to best improve preparedness and minimize health impacts for medically vulnerable populations during wildfires.

Infrastructure disruptions and population displacements during extreme events can lead to protracted morbidity and mortality in affected populations.Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai and Pirani 1 , Reference Cissé, McLeman, Adams, Pörtner, Roberts and Fischlin 6 , Reference Kishore, Marqués and Mahmud 7 Interruptions in critical utilities such as power shut-offs can result in lack of refrigeration leading to medication and food spoilage, as well as the inability to power electricity dependent medical equipment such as home nebulizers and assist devices.Reference Casey, Fukurai and Hernández 8 Acute displacement after a disaster can also be problematic for those who depend on social services and home health services, such as meal delivery and home nursing care. Health systems and communities are poorly prepared to plan for or respond to the growing disruptions in critical utilities and forced displacement resulting from extreme events such as wildfires.Reference Kishore, Marqués and Mahmud 7 , Reference Balsari, Kiang and Buckee 9

At-risk populations, including lower income individuals and those with chronic medical conditions, tend to be most impacted by extreme weather events, including wildfires.Reference Casey, Fukurai and Hernández 8 , Reference Raker, Arcaya and Lowe 10 , Reference Flores, McBrien and Do 11 People with chronic medical conditions often require outpatient services or home health care such as dialysis, cancer treatment, infusions, or home nursing that may be compromised by evacuations or utility interruptions. Others use durable medical equipment and are affected by power disruptions at home or during evacuations. In California alone, over 230 000 Medicare beneficiaries (most of whom are over 65 years old) rely on electricity dependent medical devices, increasing their vulnerability to disasters. 12 – 14

Since the most destructive wildfire season on record in California in 2018, with nearly 2 million acres burned and over 24 000 structures destroyed, 15 an array of programs have been implemented to protect communities from wildfires. These programs range from fuel reduction activities and increased volunteer fire capacity to community outreach during smoke events. 16 , 17 This study was led by a team from CrisisReady.io, a research-response initiative at Harvard University and Direct Relief that provides decision-support tools to local communities and response agencies during wildfires. To be better attuned to community needs, in collaboration and consultation with local response agencies, this study was designed to better understand the information needs and health impacts of the medically vulnerable – did they have the information they needed to make informed decisions about their health care in preparation of, during, and after wildfire events?

To answer this question, Mariposa County local officials advised interviewing a subset of Mariposa County residents enrolled in the Support and Aid For Everyone (SAFE) program - a voluntary, county run program that assists those with special needs during an emergency, and comprises older adults and those with mobility needs. 18 Mariposa County, California, where this study was conducted, is a rural county with 90% of those 65 years and older covered by Medicare insurance. 19 Medicare is a US federal health insurance program for those over 65 years old and certain people with disabilities, providing care for over 67 million people in the United States. 12 , 13

This study evaluated the impacts of the Oak Fire that occurred in Mariposa County in 2022 on the medically at-risk SAFE population. The Oak Fire placed over a third of Mariposa County residents under evacuation orders and was the fourth largest of over 7,400 wildfires in California that year. The Oak Fire began on July 22, 2022, and was fully contained by August 6, 2022, spreading over 19,000 acres and destroying 193 structures. 20 –Reference Somasundaram 23

There is limited published information on the preparedness, information needs, and health care access of medically at-risk communities during and after wildfires. This study evaluates self-identified community members in Mariposa County with long term medical and mobility needs after the 2022 California Oak Fire to understand their preparedness, information needs, and response to this wildfire and the resultant impacts on their health and health care access.

Methods

Study Design

Study population

This study is a descriptive cross-sectional mixed-methods survey of participants in the Support and Aid For Everyone (SAFE) program of Mariposa County Health and Human Services Agency (MC). 18 The SAFE program, into which participants select to enroll voluntarily, is run by MC to identify and assist people with special needs in an emergency, including the need for mobility assistance or use of electricity dependent durable medical equipment (DME). Mariposa county is a rural county, with an estimated population of 17 126, with more people over the age of 65 (31.0% vs. 16.2%), a lower median household income ($60,021 vs. $91,905), and a higher percentage of high school graduates (91.9% vs. 84.4%) than California as a whole. The majority of the population speaks English at home (89.5%), and 75.6% of the population identify as White and not Hispanic or Latino. 24

Survey instrument

The survey instrument was designed collaboratively via structured consultation with Mariposa County health officials and the SAFE program, balancing survey length with utility of information for all stakeholders. Due to COVID-19 pandemic-related limitations on conducting in-person interviews with this population – most of whom were elderly – we were advised by MC and SAFE officials to conduct the study remotely via a questionnaire. All participants were offered the option of a phone interview or a self-administered survey. Video interviews were deemed not feasible in this study population.

The survey instrument was finalized through a wide structured consultation process with officials from the California Department of Public Health and MC, in addition to subject matter experts on the CrisisReady.io research team. The survey instrument was informed by a review of similar instruments used in prior studies on wildfires and hurricanes as well as PG&E’s lists of medical conditions and electricity dependent medical devices.Reference Kirsch, Feldt and Zane 25 – 27 The consultation process was iterative and consensus based, centering on the needs of the local agencies and the SAFE program. Finally, the instrument was tested by local members of the study team familiar with the survey population and revised for clarity and flow. The instrument was not formally validated before administering to the survey population.

Survey questions included demographic and baseline information on medical conditions and mobility needs, the impact of the Oak Fire on medical appointments, and perceived harm to health. It also included questions on wildfire preparedness and information needs in relation to Oak Fire evacuation and health care disruptions. The total survey was 34 questions long and took approximately 45 minutes to complete. The majority of questions (31 of 34) were nominal categorical questions. Three qualitative short-answer questions explored what participants would do differently in a future fire, what information they would have liked but did not get during the Oak Fire, and how the actual evacuation was different from their preparation. The questionnaire is included in the supplementary material.

The survey was mailed to all 239 SAFE participants in April of 2023. Only 1 participant requested a phone interview, and 52 responded via mail by July of 2023. There was no direct incentive for completing the survey.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed in Microsoft Excel Version 2310. Surveys with missing data were analyzed based on questions with complete responses. For each question, the total number and percentage of respondents were reported. Comparison of the survey subset population to the overall SAFE population was performed via t tests given the embedded survey population. Hypothesis testing to evaluate whether a greater number of medical conditions or use of medical devices were associated with medical harm, possibly from delay of care, missed appointments, or evacuations, was done using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for nonparametric data (medical devices) and t tests for parametric data (medical conditions). The variable of medical harm associated with delay of care was dichotomized into either no harm (for none, or not really) and harm (for somewhat or significant). All hypothesis testing was performed using Stata Version 18. 28

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative short answer responses to information respondents would have liked during the Oak Fire, and how the actual evacuation was different from their preparation were reproduced verbatim in quotation marks as distinct supplemental statements to support findings. The research team conducted a descriptive content analysis to the qualitative responses to what respondents would do differently in a future fire; responses were separated into 2 distinct content areas. Representative responses by content area are presented in the results. Other categorical responses were not transformed in the analysis and are included here as the response category “other.”

Ethics Approval

This human subject research was approved by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Institutional Review Board, Protocol # IRB21-1581. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Informed consent was obtained verbally prior to telephone interviews and was implied for returned mail surveys with a cover letter provided asking for participation that detailed the purpose of the survey, voluntary nature, confidentiality, and potential risks and benefits as per the guidelines for informed consent.

Results

Demographic and Baseline Medical Information

The survey was sent to all 239 SAFE participants; 10 were returned to the sender due to incorrect addresses. A total of 53 surveys were completed, 1 of which was completed via phone interview. The response rate was 23.1% of the SAFE population. Per question, the median number of missed responses was 1 (Interquartile range = 2), with a maximum of 7 responses missing for the question listing medical devices.

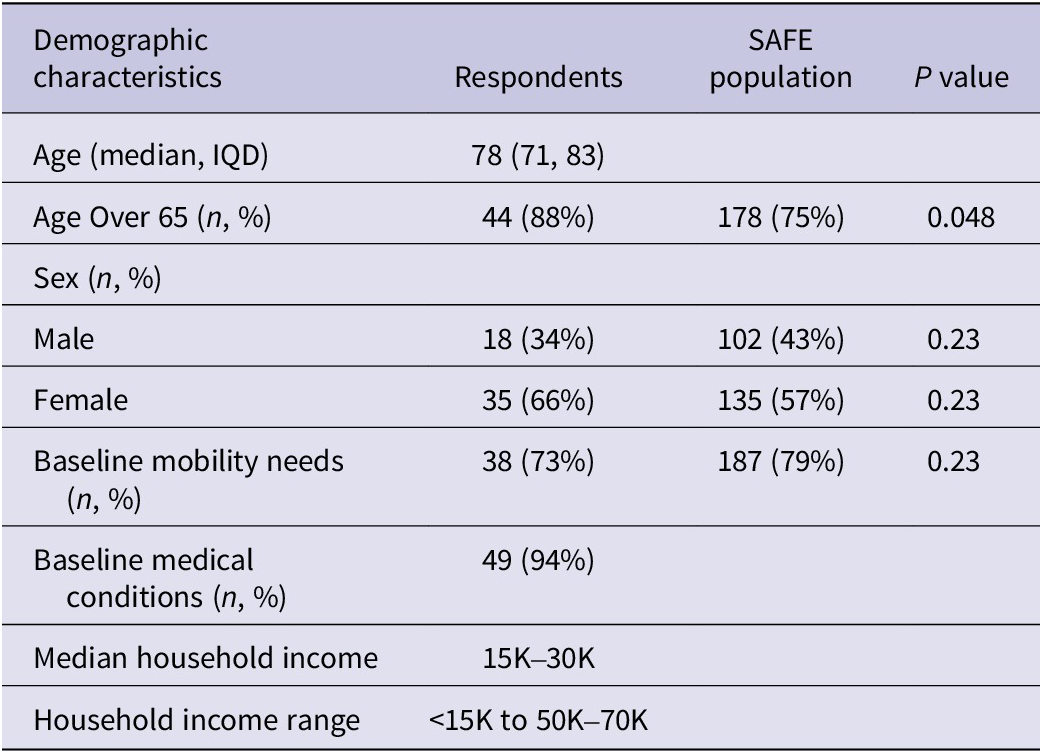

Most respondents were female (66%; N = 35/53), with median age of 78 years and median household income range of $15,000-$30,000. Demographic and medical information from the respondents was compared to all available information from the SAFE population. There was no significant difference in sex or baseline mobility needs in the survey respondents compared to the entire SAFE population, although there were more survey respondents over the age of 65 years (Table 1).

Table 1. Respondent demographic characteristics in comparison to overall SAFE population

Nearly ¾ (73%; N = 38/52) of respondents had mobility issues and 94% (N = 49/52) had baseline medical conditions. An additional 83% (N = 38/46) of respondents reported using medical devices; however, 7 did not provide a response. Approximately half (47%; N = 23/49) needed help with activities of daily living. The list of reported medical conditions and devices is included in the appendix (Tables 1a and 2a).

Of those who used medical devices, 53% (N = 20/38) were not part of Pacific Gas & Electric’s (PG&E) medical baseline program, an assistance program for PG&E customers who have certain electricity dependent medical conditions. 27

Ninety-four percent of respondents (N = 48/51) took medications every day prior to the Oak Fire. Twenty-two percent (N = 11/51) took medications that needed refrigeration. Approximately 81% (N = 42/52) kept their medication list on paper, 15% (N = 8/52) on a phone or computer, and only 12% (N = 6/52) did not have a copy of their medication list.

Impact of the Oak Fire on Medical Appointments

One-fifth (21%; N = 11/53) of respondents reported missed or delayed medical appointments due to the Oak Fire. All those who missed an appointment reported missed routine follow up appointments; in addition, 18% (N = 2/11) also missed a physical therapy appointment, and another 18% (N = 2/11) missed other types of appointments. Of those that missed appointments, the majority experienced long delays in care: 45% (N = 5/11) reported months-long delays, another 45% (N = 5/11) reported weeks-long delays, and only 9% (N = 1/11) reported a delay in days. The Oak Fire did not permanently change the location of medical care for any respondents.

Self-Reported Health Harms from the Oak Fire

Twenty-one percent of respondents (N = 10/48) reported harm to their health from delays in medical care related to the Oak Fire. Another 29% (N = 14/48) reported delays that did not really harm them, nearly half (48%; N = 23/48) of respondents reported that they didn’t experience delays in their medical care, and 1 respondent (2%; N = 1/48) could not recall.

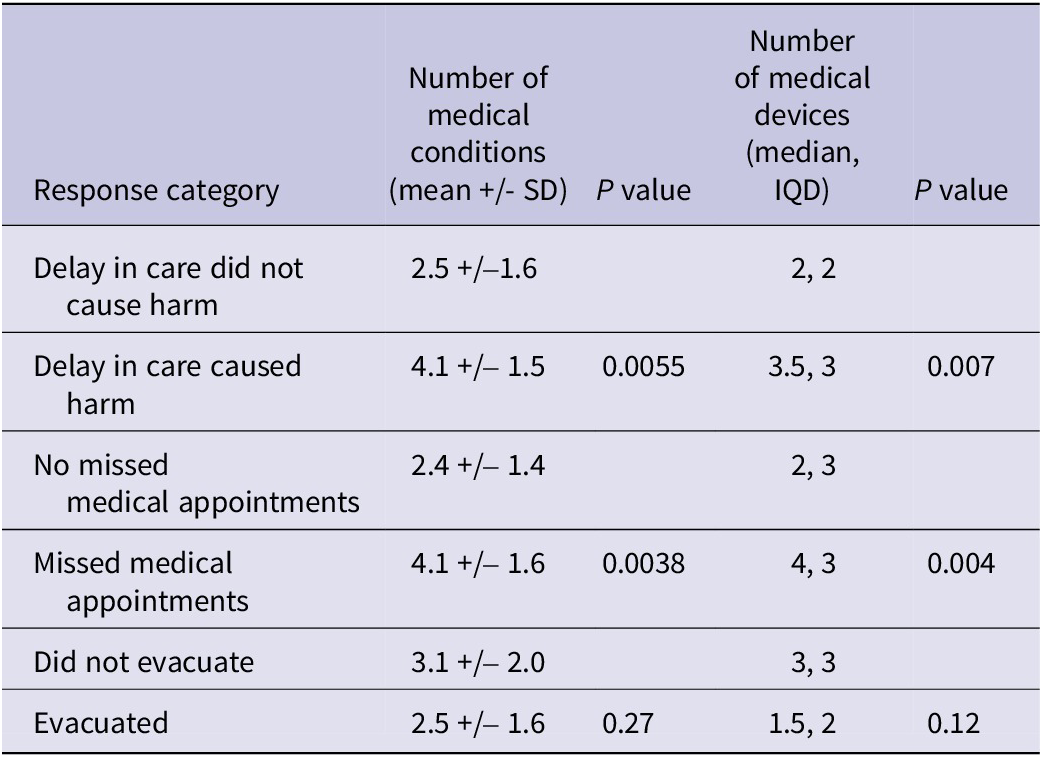

The group that self-reported missed medical appointments had significantly more medical conditions (mean 4.1 vs. 2.4, P = 0.0038) and used more medical devices (median 4 vs. 2, P = 0.004) than the group who did not report missed medical appointments. The group that self-reported harm from delayed care also had significantly more medical problems than the group that did not report harm (mean 4.1 vs. 2.5, P = 0.0055). The group that self-reported harm also used significantly more medical devices (median 3.5 vs 2, P = 0.007); Table 2.

Table 2. Association between number of medical conditions and number of medical devices on health and evacuations

Wildfire Preparedness

Most respondents (75%; N = 38/51) reported evacuating from a fire previously, with 33% (N = 17/51) reporting multiple prior evacuations. A California Department of Public Health household assessment found a similar number of households (63%) in Mariposa County that reported prior evacuations from extreme weather in the past 10 years.Reference Choudhury 29 Seventy-three percent of respondents (N = 37/51) routinely store water during wildfire season and 54% (N = 28/52) of respondents have a working backup generator or other backup source of electricity. The Oak Fire led to 38% (N = 19/50) of respondents reporting losing at least part of their food supply (Appendix Table 3a).

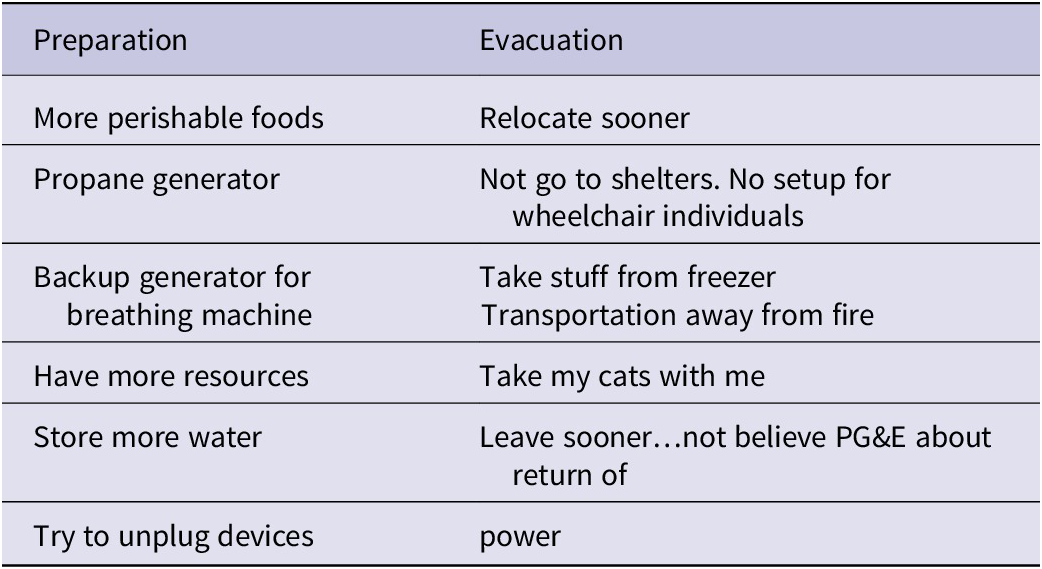

Overall, approximately half of respondents (52%; N = 26/50) would not do anything differently in a future fire after living through the Oak Fire. Respondents provided free text responses about future strategies; 2 major content areas of preparedness and evacuation emerged with representative responses listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Representative responses of what participants would do differently in a future fire separated into distinct content areas of preparation and evacuation

Wildfire Information Needs

The most common stated sources of information about the Oak Fire were friends and family (67%; N = 34/51), news agencies (59%; N = 30/51), and neighbors (37%; N = 19/51), followed by utility companies (35%; N = 18/51) and community organizations (35%; N = 18/51). For information needs about wildfires overall, respondents reported most trusted information sources were county officials (77%; N = 41/53), local city agencies (66%; N = 35/53), state officials (57%; N = 30/53), friends and family (45%; N = 24/53), and neighbors (43%; N = 23/53); full lists provided in Appendix Table 4a.

The most common way respondents reported learning about the Oak Fire was when they saw the fire plumes or smelled the smoke (59%; N = 30/51). Respondents also reported learning about the fire from television (43%; N = 22/51) or were notified via landline phones (39%; N = 20/51) and in-person visits by friends or family (37%; N = 19/51). Our survey also elucidated that many devices, including landline phones, TVs, and radios, could not be used during the Oak Fire (Appendix Table 6a).

Information perceived to be most useful included fire location and progress (92%; N = 46/50), road closures (62%; N = 31/50), risk to the household (40%; N = 20/50), shelter locations (38%; N = 19/50), and evacuation routes (34%; N = 17/50); full lists provided in Appendix Table 5a.

Free-text short answer responses of desired information included: “in person checks,” “safe locations for seniors on medications and in wheelchairs,” “food and toilet facilities,” “how the fire started,” “timing of power losses,” “where to go if leaving outside evacuation areas,” and “expected wind direction.”

Evacuation Response

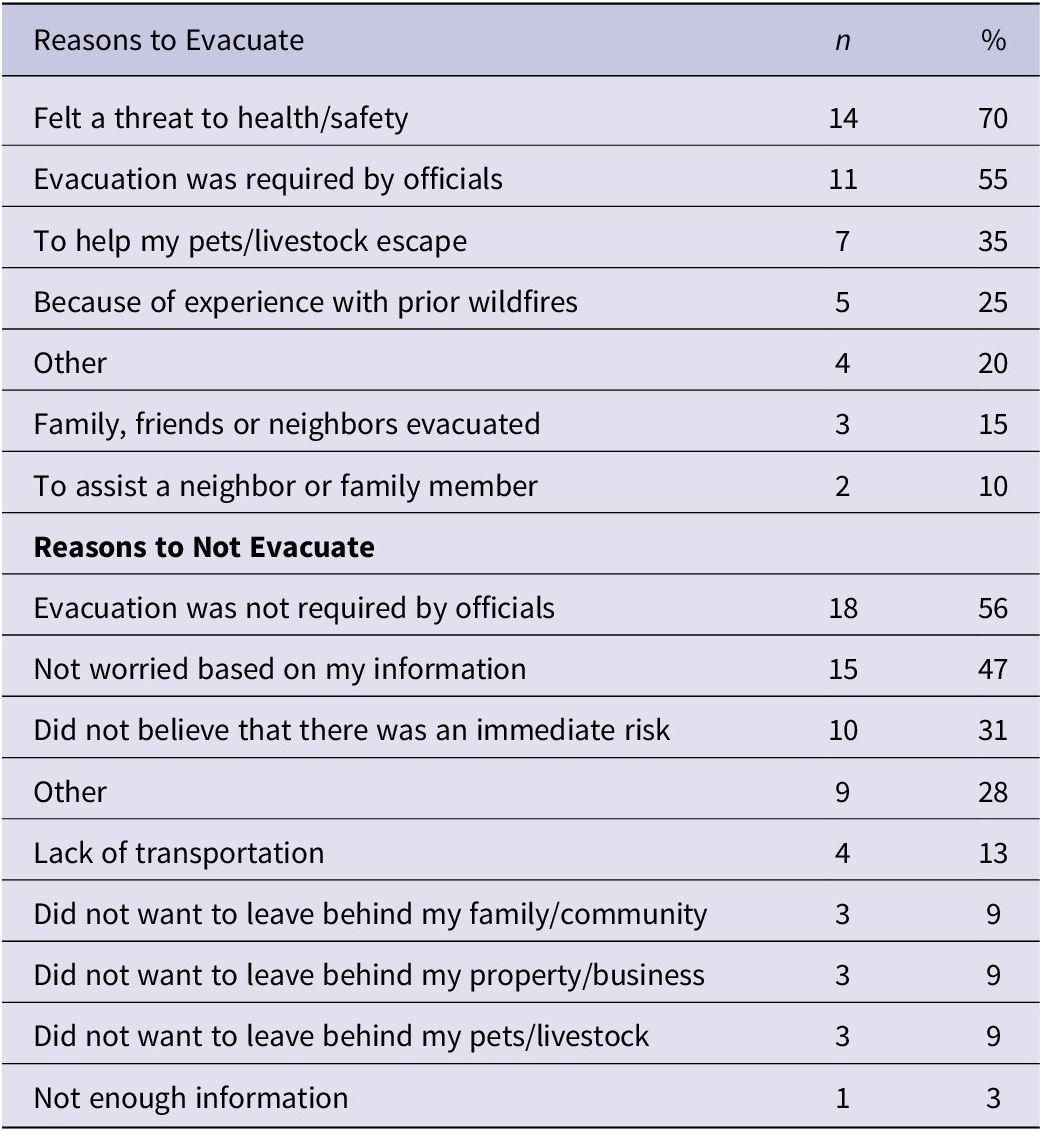

Between July 22 and August 4, 2022, mandatory evacuation orders were issued by government officials from CAL FIRE, the Sierra National Forest, and the Mariposa County Sheriff’s Department. 22 Forty percent (N = 21/53) of respondents evacuated from the Oak Fire, similar to official reports of 40% evacuation rates of the total population of Mariposa County. 20 , 24 The most common reasons stated for evacuation were threat to health and safety (70%; N = 14/20) and an evacuation mandate (55%; N = 11/20). Additional reasons for evacuation are listed in Table 4.

Table 4. Reasons to evacuate or to not evacuate from the Oak Fire a

a Respondents could select more than 1 choice.

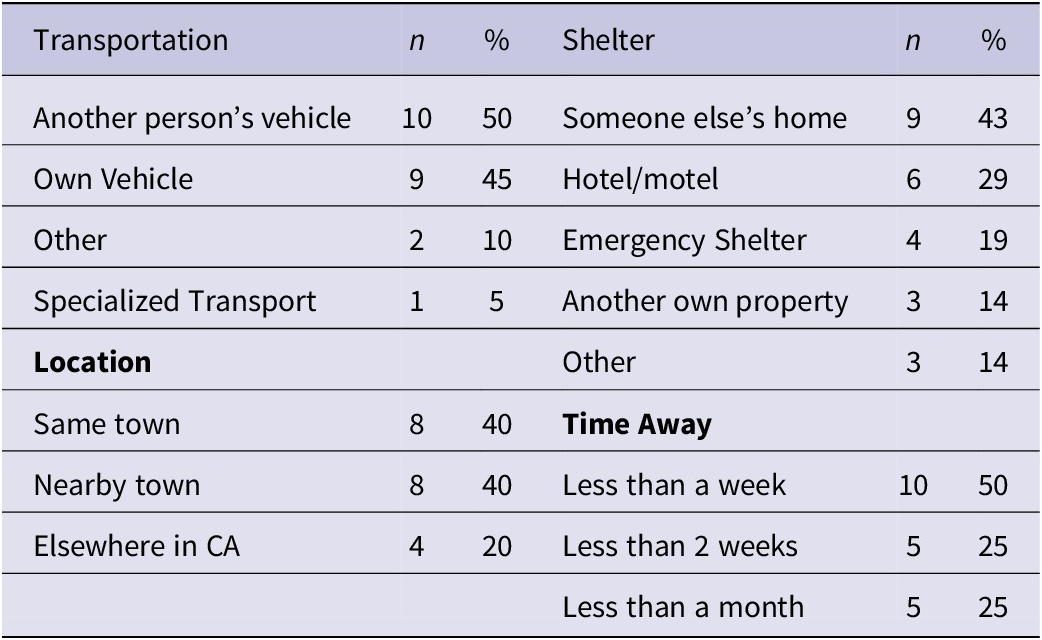

Respondents evacuated in other’s vehicles (50%; N = 10/20) or used their own vehicle (45%; N = 9/20). Forty percent of the evacuees stayed in town (N = 8/20), and an equal number (40%; N = 8/20) evacuated to a town nearby. Respondents evacuated to someone else’s home (43%; N = 9/21), a hotel/motel (29%; N = 6/21), or to emergency shelters (19%; N = 4/21). All evacuated for less than a month (Table 5). These observations are consistent with official evacuation reports of local or nearby evacuation centers.Reference Ayestas 30

Table 5. Evacuation characteristics for respondents

The majority (74%; N = 14/19) of respondents that evacuated with pets and livestock brought them with them. This is consistent with reports during the Oak Fire of people evacuating with pets and available areas for animals and livestock at shelters. 21 , Reference Ayestas 30 Half (50%; N = 10/20) of respondents stated the evacuation was similar to their preparation, 20% (N = 4/20) stated it was very different from their preparation, and 30% (N = 6/20) stated they had not prepared at all.

Those that thought the evacuation was different than expected provided free-text short answer responses of “it moved very quickly,” or that “you cannot bring belongings,” or that they “never had direct orders.” Others commented on “the stress of uncertainty of return,” and the “danger to home and lack of medications.”

Sixty percent (N = 32/53) of respondents reported they did not evacuate from the Oak Fire. The 2 most common reasons for not evacuating were that it was not mandated (56%; N = 18/32), and that they were not worried (47%; N = 15/32); other reasons are provided in Table 4.

For those respondents that did not evacuate, most (74%; N = 23/31) still knew which routes to take if they needed to evacuate and 72% (N = 23/32) knew where the shelters were located. There was no statistically significant association between the number of medical conditions or devices and the decision to evacuate (Table 2).

Discussion

Understanding the preparedness efforts, information needs, and health care access of medically at-risk populations during wildfires is increasingly important as evacuations and utility interruptions continue to be a key feature of natural disasters. Disruptions in health care access, and in critical utilities, including power, transportation, communication, and water, directly and indirectly impact health, even resulting in persistent morbidity and mortality after all types of natural disasters in the US.Reference Kishore, Marqués and Mahmud 7 , Reference Balsari, Kiang and Buckee 9 , Reference Raker, Arcaya and Lowe 10 , Reference Kirsch, Feldt and Zane 25 , Reference McBrien, Rowland and Benmarhnia 31 , Reference Lin, Zhang and Sheridan 32

This study surveyed older persons with baseline medical and mobility needs, a population known to be at increased risk during extreme weather events,Reference Casey, Fukurai and Hernández 8 , Reference Balsari, Kiang and Buckee 9 and sought to identify opportunities to improve preparedness and information access to mitigate harms. Though a small sample size, given the demographic the respondents represented, this study underscores the worrisome disruptions in health care access faced by medically vulnerable populations across the US during disasters. That 1/5 missed routine appointments, and that the vast majority could not re-establish care for weeks or months deserves urgent attention – attention that has been called for after Hurricanes Maria, Sandy, and Harvey, as well. Reference Kishore, Marqués and Mahmud 7 , Reference Balsari, Kiang and Buckee 9 , Reference Ruskin, Rasul and Schneider 33 , Reference Hamel, Wu and Brodie 34 That those with multiple co-morbidities and more dependence on durable medical equipment (DME) experienced more interruptions warrants urgent course correction. Delays in care were likely multifactorial - comprising individual factors, such as the use of DME, as well as systematic factors, such as mandatory evacuations and interruptions in transportation and critical utilities. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the root causes.

Power outages, especially during wildfire season, are not limited to disruptions in transmission lines. Public safety power shut offs, although designed to keep communities safe from fires by turning off power in the setting of dangerous weather, 35 also result in power interruptions.Reference Casey, Fukurai and Hernández 8 , Reference Ho 36 Many respondents stated they would ideally prepare with back-up electricity and supplies for future events, however, respondents also reported lack of affordability as a barrier. While PG&E’s medical baseline program is intended to help address this need by reducing costs for electricity for those with medical devices, it was notable that only approximately half (47%) of the respondents who reported the use of qualifying medical devices were enrolled. This may represent an opportunity for improvement in outreach and engagement around this program or other similar programs. 27

As with power outages, it is time for disaster preparedness and response programs to account for other interruptions in care – appointments, home visits, medication refills – and plan to mitigate them. To date, disaster planning at hospitals is focused on mass casualty events and does not preemptively risk stratify patients. Outreach and communication for evacuation orders have gotten better – but should also include information on how to resume care if disrupted during a disaster. In recent years, for example, dialysis centers have implemented programs to redirect patients to alternate facilities or provide earlier dialysis, representing proactive interventions to minimize potentially fatal disruptions in care.Reference Smith 37 –Reference Alasfar, Koubar and Gautam 39

During the pandemic, telemedicine platforms proliferated, not only due to the ingenuity of health care systems, but also because of new insurance industry support. Similar regulatory and financial support is needed to allow for proactive measures across the health system to mitigate the impact of potential evacuations, road closures, and infrastructure damage. Telemedicine and mobile clinics have been used successfully in the aftermaths of disasters, including during wildfires in California and Canada, representing a potential model for continuity of care.Reference Litvak, Miller and Boyle 40 –Reference McGowan, Baxter and Deola 42

Beyond health care facility-based preparedness, community and home-preparedness has the potential to mitigate the impact of disasters by investing in back-up power, back-up plans for health care services, and back-up communications. During critical times in wildfire response, communications have often failed, as seen with the failure of the CodeRED alert system during the Camp Fire in Paradise, CA 43 or the landlines during the Oak Fire, as reported in this survey – a surprising finding as the copper wire landlines should have remained functioning. The California Public Utilities Commission recently passed a mandate requiring 72 hours of backup power for telephone communications; 44 , 45 similar measures are needed to improve resilience of communications during disasters, especially in hard-to-reach rural areas.

Respondents often waited until seeing or smelling the wildfire in this study, despite articulating high levels of trust in official sources of information, as has been observed elsewhere.Reference Choudhury 29 , Reference Burger, Gochfeld and Jeitner 46 –Reference Hoshiko, Buckman and Jones 48 Community interventions that further understand and address these barriers requires a multifaceted approach, as when and why people evacuate is highly context specific.Reference Diaz, Acero and Behr 49 –Reference Deng, Aldrich and Danziger 52 Previous studies have elucidated evacuation patterns based on race, wealth, and pet and livestock ownership among other factors, although there is limited evidence on how medical conditions effect evacuation decisions.Reference Diaz, Acero and Behr 49 –Reference Chadwin 53 Further research is needed on how dependence on medical devices and how chronic health care needs at shelters and target destinations impact evacuation decisions in a wide range of disasters across the US.

Limitations

This study was a sample of a specific sub-population in one county of persons with a self-identified need for additional assistance during disasters. Although the study sample size was small, potentially limiting generalizability, this study sample representing older and low-income adults who were demographically similar to the overall SAFE population and constitute some of the most medically vulnerable populations in disasters. The response rate of 23.1%, though not high, with potential for non-response bias, is consistent with similar response rates in hard-to-reach populations, and did include the most vulnerable, with a median age of 78 and low-income households.Reference Nota, Strooker and Ring 54 , Reference Sinclair, O’Toole, Malawaraarachchi and Leder 55 Though some questions had missing responses, there was no systematic or significant missingness, except for the categorical question listing medical devices, left unanswered by 7, likely non-users of durable medical equipment.

The survey was administered in English on the recommendation of local officials; no survey recipient requested another language and English is spoken by the vast majority of Mariposa residents. 24 The survey was sent out approximately 8 months after the Oak Fire, in part because of other ongoing emergencies in Mariposa County, introducing the risk of recall bias. This was mitigated through careful and deliberate selection of questions minimizing distortion as well as allowing for open-ended short-answer responses.

Conclusions

This study affirms the growing recognition that interruptions to health care access during and in the aftermath of disasters impact health long after the initial insult. Preparedness must focus not only on response to disasters but preempting health care disruptions at home through improved outreach and communication, facilitating access to back up power and supplies and creating pathways to efficiently reinstate health services.

Lessons learned from the SAFE program are likely generalizable, as victims of major disasters globally experience direct and indirect disruptions in health care access and downstream impacts on health. Preparing health systems for the acute impacts of disasters necessitates moving preparedness planning into homes and communities, following the lead of several counties, health departments, and even utility companies in California. 16 , 17 , 27 , 56 –Reference Chi, Williams and Chandra 58

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2025.10063.

Author contribution

TW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing- Original Draft, Writing- Review & Editing. CD: Conceptualization, Survey & Methodology Development, Writing- Review & Editing. ES: Conceptualization, Survey & Methodology Development. KK: Conceptualization, Survey & Methodology Development. AS: Conceptualization, Writing- Review & Editing, Resource Support, Supervision. SB: Conceptualization, Survey & Methodology Development, Writing- Review & Editing, Resource Support, Supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Funding statement

This work was made possible in part by funding received through the organization CrisisReady.