Can American state legislators use social media messages to impact the behavior and attitudes of the public? We know that legislators are on social media (Cook Reference Cook2017; Gainous and Wagner Reference Gainous and Wagner2014; Russell Reference Russell2021), post about political topics (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Nakka, Gopal, Desmarais, Mancinelli, Harden, Ko and Boehmke2022; Payson et al. Reference Payson, Casas, Nagler, Bonneau and Tucker2022), and are influenced by their presence on social media (Gilardi et al. Reference Gilardi, Gessler, Kubli and Müller2022). It is also clear that most Americans regularly use social media (Gottfried Reference Gottfried2024), and the majority of social media users consume news and political information (St. Aubin and Liedke Reference St. Aubin and Liedke2023). When research has examined the impacts of social media posts on individuals, the focus has been on posts from well-known elite actors in traditional survey experiments, such as the impacts of Donald Trump’s tweets on anti-democratic attitudes (Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Davis, Nyhan, Porter, Ryan and Wood2021). To date, there has been little investigation into the discrete effects of individual political posts from other political actors on public attitudes and behaviors, despite the heavy uptake of social media sites from actors at every level of government. For example, 72.8% of state legislators had a Twitter (now X) account as of 2021 (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Nakka, Gopal, Desmarais, Mancinelli, Harden, Ko and Boehmke2022). There are numerous observational claims that social media has affected our political environment (e.g., Sunstein Reference Sunstein2018), but no work focuses on the short-term, individual-level impacts. In this article, I examine whether state legislators’ social media messaging choices directly influence the political attitudes and behavior of their online constituents.

Researchers and the public have expressed concerns that social media use has adverse effects on society, particularly in the realm of politics (Persily and Tucker Reference Persily and Tucker2020). However, past research also suggests that the relationship is more complex at the individual level. I theorize that the impact of legislators’ messaging choices on individuals will be determined by the rhetorical strategies employed, as well as the partisan relationship between the legislator and their online audience.

I find that all three rhetorical strategies (constituent service, policy positions, and partisan politics) employed in my treatments have a direct effect on individuals’ attitudes compared to respondents viewing apolitical posts from state legislators. I demonstrate that legislators’ messaging strategies influence individuals’ evaluations of the legislators in question, and in some cases, trust in government. However, I do not find evidence that these rhetorical strategies are effective in mobilizing individuals to participate in politics. While certain results from this study are substantively small, I expect that organically viewing political posts on social media feeds will compound the effect in individuals over time.

Beyond these substantive findings, I contribute theoretical and methodological advances to the study of politics and social media, the legislative–constituent relationships, and state politics. By focusing specifically on hypothetical posts from state legislators, I limit the preconceived notions individuals bring to posts from elite politicians and focus on the direct impact of the messages themselves, showing that the public can be swayed by political posts, even from accounts they do not recognize. Additionally, my creation of a simulated social media environment embedded within a survey experiment mimics the effects of real state legislators communicating with their constituents while maintaining the internal validity of a traditional survey experiment.

The contributions in this article apply to a variety of additional cases. Theoretically, the finding that messaging choices from unfamiliar state legislators can impact their constituents’ short-term attitudes suggests that political actors may influence public opinion, regardless of their follower count, so long as they are connecting with those who share their areas of interest. This is especially relevant to those who study local politics, political communication, or political organizations, as other political actors, such as mayors, activists, or nonprofits, have the potential for similar effects from strategically crafted online messages. Future research using a simulated social media environment, as I introduced in this study, has even wider potential applications. Observing reactions to misinformation, controversial posts, or political content, for example, could be applied to studies of pressing issues such as affective polarization, political social identities, or political knowledge.

The online legislator–constituent relationship

Legislators’ communications

Legislators work to achieve policy goals, gain prestige, and win re-election (Fenno Reference Fenno1977). To realize these goals, they must effectively communicate their successes and positions to their constituents (Mayhew Reference Mayhew2004). For decades, this need was met through a combination of mailed newsletters, radio or television advertisements, and in-person town hall meetings; however, legislators have consistently adopted new methods as technology becomes viable (Epstein Reference Epstein2018). Although the average American tends to have a concerning lack of political knowledge (Delli Carpini and Keeter Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1997; Rogers Reference Rogers2023b), legislators behave as though their constituents will closely observe their actions (Bianco Reference Bianco1994; Jackson and Kingdon Reference Jackson and Kingdon1992) and believe that missteps could lead to electoral failure (Hutchings Reference Hutchings2005).

Mayhew (Reference Mayhew2004) expected legislators to prioritize three strategic actions: advertising, credit claiming, and position taking. As American parties have become stronger at the federal (Theriault Reference Theriault2008) and state levels (Shor and McCarty Reference Shor and McCarty2022), legislators must be aware not only of their reelections but also of their parties’ power in the legislative chamber (Lee Reference Lee2009). Despite sharing similar incentives at the macro level, individual legislators employ a variety of strategies, depending on their personal goals and the makeup of their constituencies (Grimmer Reference Grimmer2013; Harden Reference Harden2015). These goals inform the manner in which legislators are likely to communicate with their constituents.

The majority of legislators’ communications are focused on at least one of three topics: constituent service, policy preferences, or partisan politics (Russell Reference Russell2021). Legislators have long believed that engaging in constituent service, wherein a legislator acts as a caseworker or helping hand for individuals or small groups of constituents, is well worth the effort (Butler, Karpowitz, and Pope Reference Butler, Karpowitz and Pope2012; Cain, Ferejohn, and Fiorina Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1987). Not only do some constituents expect this behavior (Harden Reference Harden2015), but it may also increase support from otherwise disinterested constituents (Serra and Pinney Reference Serra and Pinney2004). Broadcasting this type of service has the potential to humanize legislators, showing constituents that their representative cares not just for their policy or partisan interests, but that they are willing to help individuals overcome personal difficulties or combat local problems.

Whether discussing future policy or celebrating electoral wins, it is not surprising that many legislators discuss the primary tasks for which their constituents elected them. Legislators are most likely to communicate their policy preferences when they are well aligned with their constituency’s (Grimmer Reference Grimmer2013; Mayhew Reference Mayhew2004). However, they can also successfully explain more controversial voting choices by targeting constituents with specific messaging (Grose, Malhotra, and Van Houweling Reference Grose, Malhotra and Van Houweling2015).

Partisan politics, while not a new topic of political discussion, have become increasingly salient as the parties attempt to broadcast their differences (Lee Reference Lee2016). This third topic of communication, in particular, can use two distinct strategies: copartisan support or outpartisan attacks. Both methods involve explicitly partisan-based messaging that attempts to emphasize differences between the parties, whether through direct insults or implied comparisons.

These categories are not always mutually exclusive, particularly in longer communications. For example, a legislator may explain the advantages of a specific bill (policy preference) that has a particular benefit for the constituents with whom she is communicating (constituent service), while insulting her opposition party for delaying the bill’s passage (partisan politics). However, previous research has shown that individual legislators often create a persona, or a typical style of communication with constituents (Evans, Cordova, and Sipole Reference Evans, Cordova and Sipole2014; Fenno Reference Fenno1977; Grimmer Reference Grimmer2013; Russell Reference Russell2021; Theriault Reference Theriault2013). Any one legislator can engage in every topic of communication, but on average, legislators appear more likely to specialize.

Legislators online

As legislators represent ever-larger constituencies (Bowen Reference Bowen2022), it becomes more logistically challenging to communicate effectively with their target audience. This is especially true for state legislators. First, because there has been a long-term drop in the number of local outlets consistently covering substantive political news (Hayes and Lawless Reference Hayes and Lawless2018), and second, many state legislatures are less professionalized (Bowen and Greene Reference Bowen and Greene2014) and simply do not grant legislators the resources they would need to communicate consistently with their constituents. Rogers (Reference Rogers2023b) documented a significant disparity between the public’s knowledge of state-level information and federal political information, especially regarding state-level institutions and elected officials. The lack of easy information streams, via local news or legislators themselves, may be one leading cause of this disparity.

State legislators seeking to communicate more effectively with their constituents are likely to turn to social media, regardless of the resources at their disposal. Social media is a viable, cost-effective form of communication. If necessary, a legislator could manage their social media presence with no material costs and very little time or effort. Additionally, the majority of the American public is on social media (Sidoti and Dawson Reference Sidoti and Dawson2024), and 72% of Americans report consuming news on social media sites (St. Aubin and Liedke Reference St. Aubin and Liedke2023). With the advent of modern algorithm-based social media feeds, strategic legislators could hypothetically tailor messages toward different communities, discussing the same topic using specific tones or language that is more likely to succeed with sub-groups within their constituency.

Elected officials at every level of government have recognized the utility of social media (Cook Reference Cook2017; Gainous and Wagner Reference Gainous and Wagner2014; Russell Reference Russell2021). While state legislators have not been as quick to adopt social media as Members of Congress, a significant proportion of state legislators have created online accounts, and the number is growing over time. For example, 65% of state legislators used X (then Twitter) in 2015 (Cook Reference Cook2017), while 72.8% of state legislators had an active account by 2021 (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Nakka, Gopal, Desmarais, Mancinelli, Harden, Ko and Boehmke2022).

Impact on constituents

There is evidence that legislators may directly benefit from being on social media. A single “viral” post can significantly increase a legislator’s fundraising success (Kowal Reference Kowal2023). Social media may even be a vehicle for legislators to learn about their constituents’ preferences. Not only do legislators appear to follow the interests and preferences of their online community (Barberá et al. Reference Barberá, Casas, Nagler, Egan, Bonneau, Jost and Tucker2019), but they are also encouraged to vote more in line with the preferences of their offline constituency (Mousavi and Gu Reference Mousavi and Gu2019). However, it is less clear how legislators’ online communications might directly impact their constituents.

In traditional forms of communication, the public is often ready to defer to party elites, whether the information is coming from the party as a whole (Bullock Reference Bullock2011), the sitting president (Barber and Pope Reference Barber and Pope2019), or state legislators (Broockman and Butler Reference Broockman and Butler2017). When strategically approached, individuals can even be persuaded by legislators with whom they disagree on an issue (Grose, Malhotra, and Van Houweling Reference Grose, Malhotra and Van Houweling2015). The impact of political communications is not limited to well-known politicians, and it does not only affect partisan sycophants. Currently, there is no evidence to suggest that social media posts should work differently.

The reality of the American political system is that individuals’ attitudes and voting choices are often informed by small amounts of information. Partisan affiliation, endorsements, and candidate appearance all work as “cognitive heuristics,” which help individuals make a “correct” choice (Lau and Redlawsk Reference Lau and Redlawsk2001). In a political marketplace where individuals have limited political interest, legislators gaining their attention for even short amounts of time can be the path to receiving additional support, donations, or votes from their constituents. Based on candidate choice experiments (i.e., Eshima and Smith Reference Eshima and Smith2022; Kirkland and Coppock Reference Kirkland and Coppock2018), it is clear that individuals are willing to make up their minds about individual political candidates with relatively small amounts of information. Other attitudes, such as support for democratic norms or institutions (Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Davis, Nyhan, Porter, Ryan and Wood2021), can be impacted by short vignettes or social media posts.

Americans, in particular, view social media as having a negative impact on democracy (Wike Reference Wike2022). The public has rated federal, state, and local governments lower than in previous years (Copeland Reference Copeland2024). A consistent lack of trust in government institutions, political actors, and fellow citizens has led members of the public to worry about their ability to solve problems through traditional channels (Rainie, Keeter, and Perrin Reference Rainie, Keeter and Perrin2019). When asked about how to solve these trust-related problems, one of the most consistent answers is to work together in communities to solve local problems. Legislators, especially state legislators, have an opportunity to correct these downward trends by engaging in constituent service and casework (Grimmer Reference Grimmer2013; Harden Reference Harden2015) and broadcasting these actions to as many of their constituents as possible.

Legislator approval

Generally, social media users are impacted by the political information they are exposed to on social media sites (Feezell Reference Feezell2018). In experimental work (i.e., Wolak Reference Wolak2017), the public is willing to punish political missteps, though true accountability is not guaranteed (Rogers Reference Rogers2023a). As local news outlets continue to dwindle in number (Hayes and Lawless Reference Hayes and Lawless2018), social media remains one of the few places where citizens might easily find direct information about state-level elected officials. As early as 2012, Iowa caucus attendees who used social media had distinct views of Republican candidates prior to caucuses (Dimitrova and Bystrom Reference Dimitrova and Bystrom2013), even when accounting for the demographic categories that are predictive of political views. However, it is unclear whether these changes in attitudes are based on posts by politicians themselves or on the general political climate that emerges on social media as elections approach.

Trust in government

While Americans generally associate negative political impacts with social media (Wike Reference Wike2022), this may be attributed to the types of divisive social media posts that often gain traction online (Rathje, Van Bavel, and van der Linden Reference Rathje, Van Bavel and van der Linden2021). Social media use is correlated with polarized trust in government along partisan lines when individuals reside in states with higher levels of political conflict (Klein and Robison Reference Klein and Robison2020). While there is little research on the direct impact of legislators’ communications on individuals’ trust in government, if witnessing political conflict is predictive of polarized trust, it is possible that observing legislators communicate with or without political conflict influences their levels of trust.

Political participation

Contextual factors determine whether or not social media posts can encourage individuals toward political action. The personal networks individuals build online, for example, have successfully worked in get-out-the-vote experiments (Bond et al. Reference Bond, Fariss, Jones, Adam, Marlow, Settle and Fowler2012; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Bond, Bakshy, Eckles and Fowler2017). However, when individuals decide to engage in low-cost, low-commitment online activities, such as buying a political campaign’s merchandise, it reduces their likelihood of engaging in higher-stakes activities, such as voting (Kim, Schneider, and Ghosh Reference Kim, Schneider and Ghosh2025). While it is unlikely that benign political posts about policy or constituent service encourage political participation, based on the power of moral language (Jung Reference Jung2020) and both positive and negative partisanship (Bankert Reference Bankert2021), posts focused on partisan politics have the potential to mobilize individuals.

Theoretical expectations

In a vacuum, individual social media posts from legislators are not substantially different from other forms of political communication. The same quote from a legislator could appear in a newspaper story, campaign advertisement, or newsletter. However, the unique features of social media sites compared to other forms of written communication may impact the effectiveness or divisiveness of individual posts from political figures.

First, many social media sites used for political communication have character limits in the style of “microblogs,” which influence the types of posts on the sites. Even as character limits have been increased over time, advice from social media “gurus” consistently suggests that shorter posts perform better than longer posts. X, Bluesky, Threads, Mastodon, and TruthSocial are a few current examples of social media platforms that operate in a microblog style. Even on Facebook, where longer posts are permitted, individual followers have limited attention spans. Character limits encourage strategic users to be concise with their message and discourage the use of multiple examples or lengthy explanations, resulting in legislators engaging in simplified messaging compared with other forms of communication.

Second, social media, compared to a newsletter or newspaper story, are chaotic in the topics to which an individual is exposed. Skimming newspaper headlines might give readers a broad understanding of the current state of the world, but even online newspapers maintain traditional separations between broad topics such as “Politics” and “Lifestyle.” Social media algorithms are designed to react to both an individual’s actions and the larger social media environment; in other words, continuing to spread “viral moments.” A user might see posts about a wildfire in California followed by a meme about a pop star’s breakup. This whiplash could result in unique reactions by individual social media users to all types of content.

Finally, the physical attributes of social media sites may influence users’ moods, affecting how they react to individual quotes. The emphasis on “reacting” to, “sharing,” or even “reporting” a post has become standard social media language. For example, we “like” and “share” posts because that is what Facebook calls those actions, and a short-term, visual post is a “story” because of Snapchat, regardless of which social media site a person is using. These recent influences on the human psyche are not yet well understood, but the physical components of a typical social media site could have a profound effect.

Americans have come to expect the worst from political posts on social media in recent years (Wike Reference Wike2022). However, there is a growing desire from the public for political leaders from their communities to step up and take action. When state legislators from an individual’s home state are broadcasting constituent service or discussing popular policy proposals, I expect individuals to have a positive response to the posts compared to an apolitical post from state legislators, regardless of whether a copartisan relationship exists. Observing positive messages from state-level officials could increase their trust in government by combating the negative stereotypes surrounding online political posts and the disinterest of politicians. However, as the legislators in question will be in many ways doing what is expected of them (Wolak Reference Wolak2017), I do not expect individuals to be more willing to become more politically involved.

Hypothesis 1: Legislators’ posts highlighting constituent service increase trust in government (a) and support for individual elected officials (b) but do not encourage political participation (c).

Hypothesis 2: Legislators’ posts about popular policy goals increase trust in government (a) and support for individual elected officials (b) but do not encourage political participation (c).

While I expect legislators’ posts about constituent service or popular policies to have positive impacts on their constituents, partisan posts are inherently more divisive. The effect on legislators’ approval will depend on the existence of a copartisan relationship, with copartisans experiencing increased approval compared to viewing apolitical posts from copartisan state legislators, while outpartisans experience a decrease in approval compared to viewing apolitical posts from outpartisan state legislators. By playing into the stereotypes of divisive partisan posts from political actors, I expect both copartisans and outpartisans to experience a decrease in their trust in government relative to those who view apolitical posts from state legislators. Finally, by more directly activating individuals’ negative or positive partisanship, I expect that copartisans and outpartisans who view partisan posts will both be more willing to participate in politics than those who view apolitical posts from state legislators.

Hypothesis 3: For copartisans, legislators’ posts focused on partisan politics decrease trust in government (a) but increase support for individual elected officials (b) and encourage political participation (c).

Hypothesis 4: For out-party members, legislators’ posts focused on partisan politics decrease trust in government (a) and support for individual elected officials (b) and encourage political participation (c).

Research design

To test my hypotheses, I use a preregisteredFootnote 1 survey experiment. The survey was designed using Qualtrics, and the respondents (N = 1511) were recruited via Cloud Connect (Stagnaro et al. Reference Stagnaro, Druckman, Berinsky, Arechar, Willer and Rand2024). The respondents were randomly assigned to a simulated social media environment featuring one of four types of posts from state legislators: constituent service, policy positions, partisan attacks, or a control condition wherein the legislators are not overtly posting about politics.Footnote 2 The respondents were also assigned to one of two political identities: Democratic or Republican state legislators. To limit the impacts of idiosyncratic differences in how similar rhetorical strategies can be written, two treatment posts using the same strategy were included in each social media environment (Table 1). While two different legislators were shown to each respondent, each respondent saw either two outpartisan or two copartisan legislators from their home state.Footnote 3 The two treatment posts were randomly included within a collection of eight completely apolitical posts to mimic the feeling of scrolling through an actual social media platform.

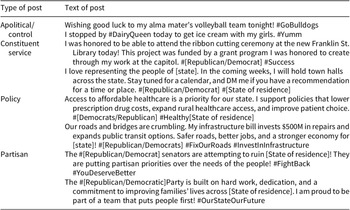

Table 1. Treatment social media posts by type

I analyze results using OLS regression with robust standard errors to measure the effects of treatment on respondents, using the apolitical posts from legislators as the control. I am poweredFootnote 4 to find a moderating impact of copartisanship with the legislators in the treatment posts at small-to-medium effect sizes (d = 0.3). However, I only hypothesize that this relationship will matter when the legislators’ posts focus on partisan politics.

Additional measured covariates include age, political participation, and whether the individual is an intense social media user. I show three models for each outcome variable: one that displays the statistical impact of treatment online, one that includes an interaction term for copartisanship with the treatment, and one that includes additional covariates. To ensure the quality of the data being collected and the reliability of results, I employ an attention check prior to the assignment of treatment and two fact-based manipulation checks prior to asking respondents any outcome variables (Kane Reference Kane2024).

Outcome variables

I test the impact of my treatment conditions on respondents’ approval of individual legislators, their trust in government, and their willingness to be contacted by a group of copartisans from their state of residence. These variables account for the major anticipated goals of legislators in posting on a public social media page. These questions also gauge normatively important outcomes concerning the more general impact of social media on political attitudes and behavior.

Respondents’ approval of individual legislators was assessed using a standard five-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly Approve” to “Strongly Disapprove.” In the main text of this article, the support of both legislators is averaged (with pooled SEs) to maintain clarity, as the results are not sensitive to this choice.Footnote 5 Trust in government is measured using the five American National Election Studies (ANES) questions on trust in government (Macdonald Reference Macdonald2020). These questions capture perceived waste and corruption by the federal government, as well as the general belief that the federal government and court system will “do what is right.” While the legislators displayed in the simulated social media environment are state legislators, the ANES questions ask about the federal government to facilitate comparison with past work.

Measuring behavior, and not just short-term attitudes, can be a valuable test of potential real-world impacts (Krupnikov and Levine Reference Krupnikov and Levine2019). Choosing a behavioral measure of survey respondents’ willingness to participate in politics is complex. Real-world political participation is a significant commitment; showing up to a protest, donating money, or knocking on doors for a candidate all require more effort than a single click. To acknowledge this, I wanted to encourage respondents to consider their willingness to incur a cost before selecting an answer. The survey asks, “Elected officials are always interested in finding engaged members of their constituency. Would you be willing to leave your contact information for [State of residence] [Respondent’s party] to potentially reach out?” The implication of a potential phone call or email mimics the cost of real-life political participation. However, I also wanted to avoid invading respondents’ privacy. For this reason, respondents were never actually prompted to share their contact information on the following pages of the survey; the question remained hypothetical. This is an attempt at a novel question to gauge political participation while emulating surveys that ask respondents to sign a political petition as a behavioral outcome (Sands and de Kadt Reference Sands and de Kadt2020). This question is highly correlated with respondents’ accounts of past political participation.Footnote 6 All outcome variables were rescaled from zero to one to simplify the interpretation of results. In the models and figures, larger, positive numbers are associated with higher approval ratings, greater trust in government, and a higher willingness to participate in politics.

Covariates

In theory, the random assignment of treatment conditions limits the need for the extensive use of covariates in experimental work. However, they can help ensure that the effects of a treatment condition are not the result of unmeasured differences between the control and treatment groups. The variables included in some models of this study are respondents’ age, self-evaluated levels of political participation, and social media use intensity.

Individuals’ experiences with social media reactions to politics vary significantly by age (Gottfried Reference Gottfried2024). Respondents were asked their age using a dropdown box with options from “Under 18”Footnote 7 to “90+.” Gauging respondents’ interest in political participation is crucial when asking a related outcome variable, such as their willingness to be contacted by a local political party organization. Respondents were asked about engaging in 11 different behaviors, including “[Did you] try to convince anyone that they should vote for or against a party or candidate?” and “[Did you] take part in a protest, march, or demonstration?” The format and item wording mimic similar questions on the ANES.Footnote 8 The full range of responses was rescaled from zero to one.

There is less consensus on how best to measure the way individuals behave online. Self-reported time estimates are often inaccurate (i.e., Verbeij et al. Reference Verbeij, Pouwels, Beyens and Valkenburg2021), and they also do not provide insight into the types of behaviors individuals might prefer engaging in online. This survey asks respondents not only how often they use individual social media sites such as Facebook and Reddit, but also the type and frequency of activities they typically take part in on social media: posting their own content, sharing content from others, or reading others’ content. Measuring the type and frequency of different social media activities has been validated as a way to gauge the intensity of individuals’ social media use (Li et al. Reference Li, Joseph, Phoenix, Su, Anise, Tang and Qin2016). The models presented in the main text use this intensity scale as a covariate, rescaled from zero to one.

Treatment posts

The treatment groups in this study were shown four types of posts by state legislators: constituent service, policy positions, partisan attacks, and apolitical/control posts. The types of posts used in the treatments were inspired by pre-existing research on legislators’ social media choices (Hemphill, Culotta, and Heston Reference Hemphill, Culotta and Heston2013; Payson et al. Reference Payson, Casas, Nagler, Bonneau and Tucker2022; Russell Reference Russell2021). Russell (Reference Russell2021) categorized US senators as constituent servants, policy wonks, or partisan warriors and found that legislators tend to specialize in one of the three online personas. These online personas also align with the literature’s general expectations of legislators’ behavior (Fenno Reference Fenno1977; Grimmer Reference Grimmer2013; Hutchings Reference Hutchings2005; Mayhew Reference Mayhew2004).

To emphasize common legislator strategies on social media and not the idiosyncrasies of individual posts, each treatment group was shown two treatment posts using similar strategies (Table 1). To test copartisan and outpartisan reactions, the posts are phrased so that changing only partisan labels results in a realistic post from either Democratic or Republican legislators (Figure 1). To increase respondents’ potential connection with the fictional legislators and maintain the belief that these could be real legislators, each treatment post comes from either a State Senator or State Representative from the respondent’s state of residence. All treatment posts, including the control, make clear that the legislator is from the respondent’s home state, as well as display their partisan affiliation.Footnote 9 This research design takes advantage of the fact that the vast majority of Americans know very little about their state governments, except in the case of the sitting governor (Rogers Reference Rogers2023b). Each respondent viewed one male legislator (Legislator 1) and one female legislator (Legislator 2), both white and in nondescript business casual apparel. Future work should vary visual and identity-based details to investigate changes in reactions among the public.

Figure 1. An example of one possible treatment post.

Note: In this case, the respondent would have been from Iowa, and was assigned the Policy Treatment. This would have been one of 10 posts seen by the respondent, all on the same Qualtrics page. In the case of being assigned Democrat-aligned treatment posts, the only change would be #Democrat instead of #Republican.

The topics of the individual posts are kept as professional and broadly applicable as possible while maintaining a semblance of realism. The control posts mention nothing about politics except the partisan affiliation of the legislators within the names of the posting accounts. The constituent service posts involve the opening of a grant-funded library and planning for local town halls. The policy posts are relatively popular positions: more quality healthcare and increased infrastructure spending, phrased in such a way that either party could feasibly be supporting it (i.e., Republicans and Democrats tend to support plans to “improve patient choice” and have “safer roads, better jobs”). The partisan posts are generic in phrasing but strong in intent: accusing the out-party of attempting to ruin the state and claiming that the in-party is notable for putting people first, implying that the out-party is not.

Social media environment

The treatment portion of the survey was carefully designed to mimic multiple aspects of a real social media environment. First, the two treatment posts are randomly embedded within eight “filler” posts (Supplementary Table 10). The posts intentionally vary in length and complexity, and use emojis along with traditional texts. While all respondents saw the same filler posts, the order of the filler posts was randomized.

The respondents were also able to interact directly with both the treatment and filler posts, and the instructions prior to assignment of treatment encouraged them to do so. My intention was to encourage respondents to be in a similar mindset as when they are logged into their own social media accounts. While the simulated social media environment intentionally mimics the design and user interface of popular microblogging websites such as X, Bluesky, and Threads, I did not directly copy any official sites’ specific details. Aside from copyright concerns, I wanted to avoid any preconceived notions respondents may hold about specific popular sites or their users, as user bases vary significantly in terms of age, race, and gender, among other demographics (Sidoti and Dawson Reference Sidoti and Dawson2024).Footnote 10

Results

Legislator approval

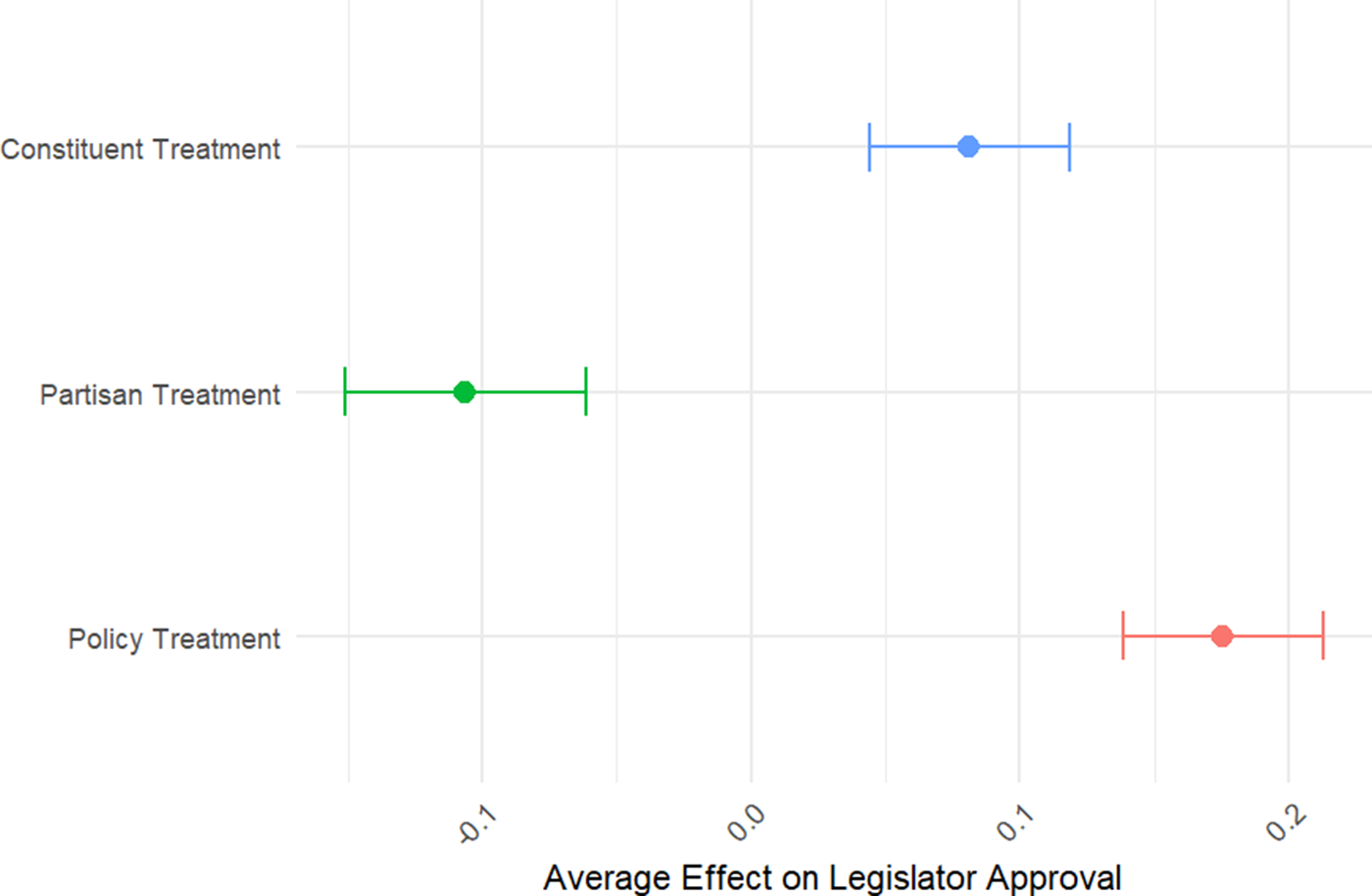

I expected that respondents’ approval of legislators would increase when viewing posts about constituent service or popular policy, while partisan posts would increase approval from copartisans and decrease approval from outpartisans. Compared to the control posts, both mock state legislators experience a statistically significant increase in approval from respondents when posting about policy and constituent service (Figure 2). On average, the policy treatments resulted in a greater increase than the posts engaging in constituent service. Both legislators experienced a statistically significant decrease in approval when they engaged in partisan posts, even before accounting for how the treatment interacts with copartisanship.Footnote 11

Figure 2. Treatment effect on legislator approval.

Note: Compared to viewing legislators’ apolitical posts, legislators engaging in constituent service or discussing popular policy position results in higher approval. Viewing legislators’ partisan posts results in lower approval.

The respondents’ significant increase in legislator approval when respondents are exposed to constituent service posts is especially notable. While the treatment wordings were written with external validity in mind, they were not personalized beyond the respondent’s state of residence. Creating a statistically significant increase in approval despite minimal personalization is a stricter test of the real-world potential.

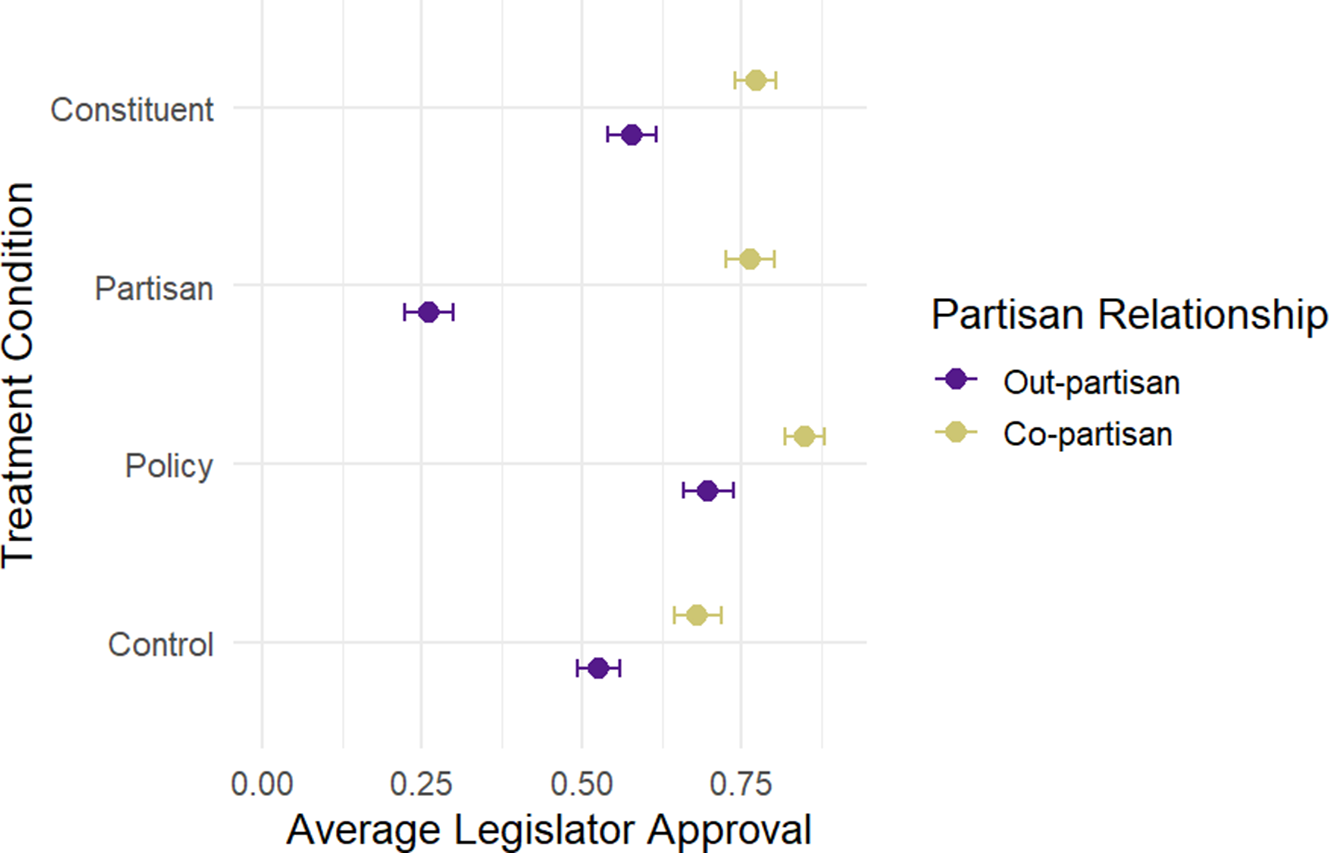

Both copartisan and outpartisan respondents experienced a statistically significant increase in their approval of the state legislators when assigned the constituent service treatment. However, there is a statistically significant gap between copartisans’ average approval and that of outpartisans, in the logical direction (Figure 3). This is despite that there is near-identical phrasing between copartisan and outpartisan posts (Table 1).

Figure 3. Average legislator approval by copartisan relationship.

Note: Copartisans have consistently higher approval of legislators, regardless of treatment condition. However, only the partisan treatment condition results in lower approval from outpartisans.

The treatment posts promoting popular policy positions, affordable healthcare and increased infrastructure spending, resulted in the highest increases in legislators’ approval from the respondents (Figure 2). While copartisanship does moderate the policy posts’ impact, outpartisans still rate the legislators higher than in the control condition (Figure 3). As in the other treatment posts, partisanship was emphasized by using Republican or Democrat hashtags to ensure that respondents were aware of the legislator’s partisan identity (Table 1). These policy positions are broadly supported by the public (Nadeem Reference Nadeem2024; Newport Reference Newport2021), but respondents’ willingness to approve of legislators when only aware of their partisanship and one short statement is a good sign for local or unknown political actors.

Figure 2 shows that the average treatment effect of partisan posts, regardless of the partisanship of the respondent, has a negative impact on the legislators’ approval ratings. I hypothesized that copartisans would have an increased approval of legislators posting partisan content, whereas outpartisans would have a decreased approval compared with the apolitical treatment conditions. In other words, it would be strategic for some legislators to engage in more hyper-partisan posts on social media. Figure 2 does not confirm this expectation. However, Figure 3 shows that the average decrease for outpartisans is dramatic enough to obscure the increase from copartisans. While the average approval from respondents who saw the apolitical control posts from outpartisans was 0.49 (equivalent to “No opinion or indifferent”), respondents who saw partisan posts from outpartisans gave an average approval rating of 0.26 (equivalent to “Slightly disapprove”). Copartisans who saw the partisan posts versus the control posts increased only 0.083 in average approval, a substantially smaller change. These results show that partisan posts only decrease approval in individuals who are not positioned to support legislators prior to viewing the posts, whereas there are potential increases with prospective supporters.

Trust in government

The public has reported a decrease in trust in government for decades. However, individuals tend to be more supportive of their state and local governments than the federal government (Nadeem Reference Nadeem2024; Wolak Reference Wolak2020). Furthermore, some of the distrust expressed by the public is likely a result of the frequent coverage of highly partisan statements, gridlock, and other polarizing issues by both traditional and new media sources. For this reason, I expected the constituent service and policy treatment conditions to have a positive impact on the individual’s trust in government, while I expected the partisan treatments, which reinforce the potential negative stereotypes of government actors, to have a negative impact.

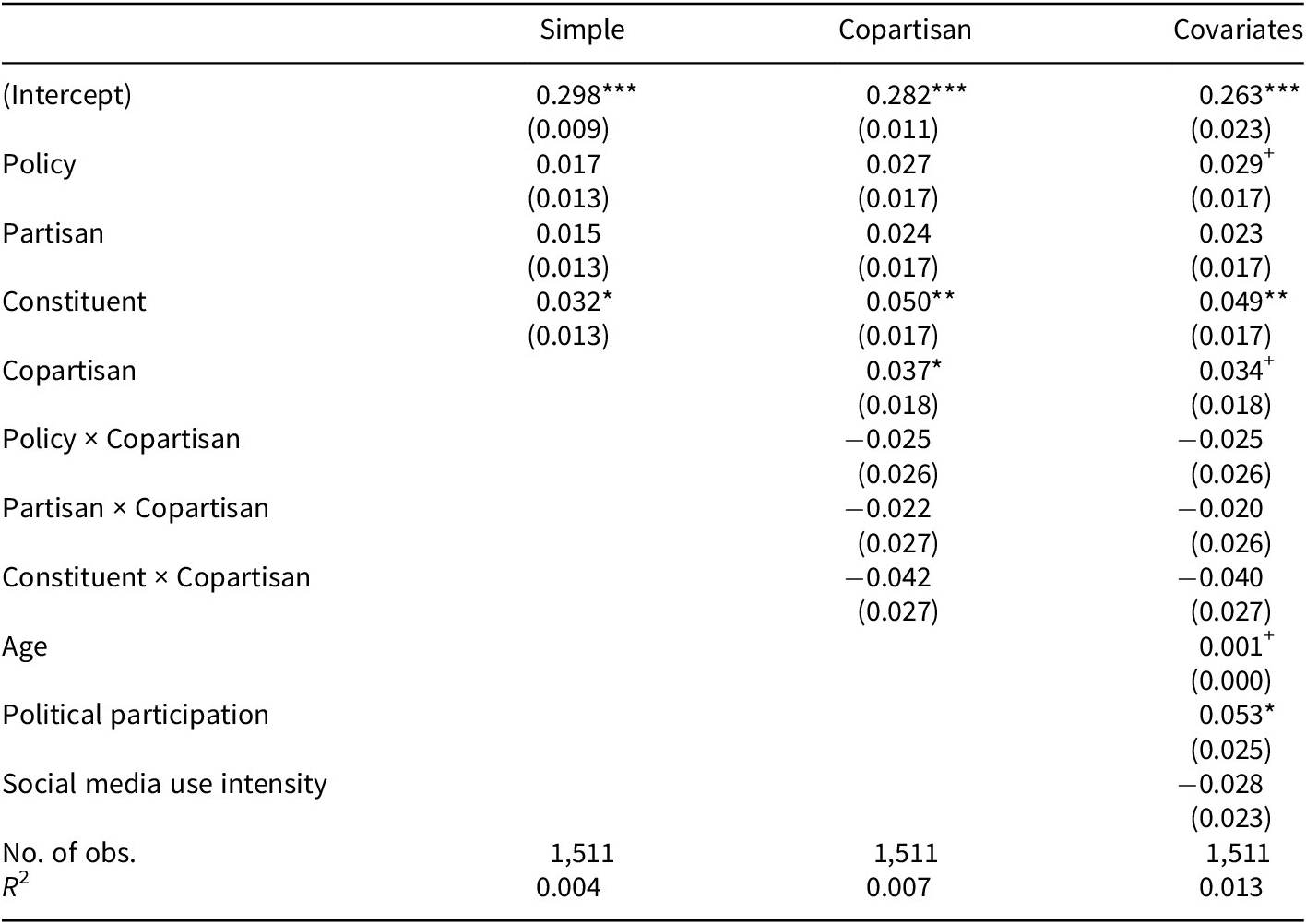

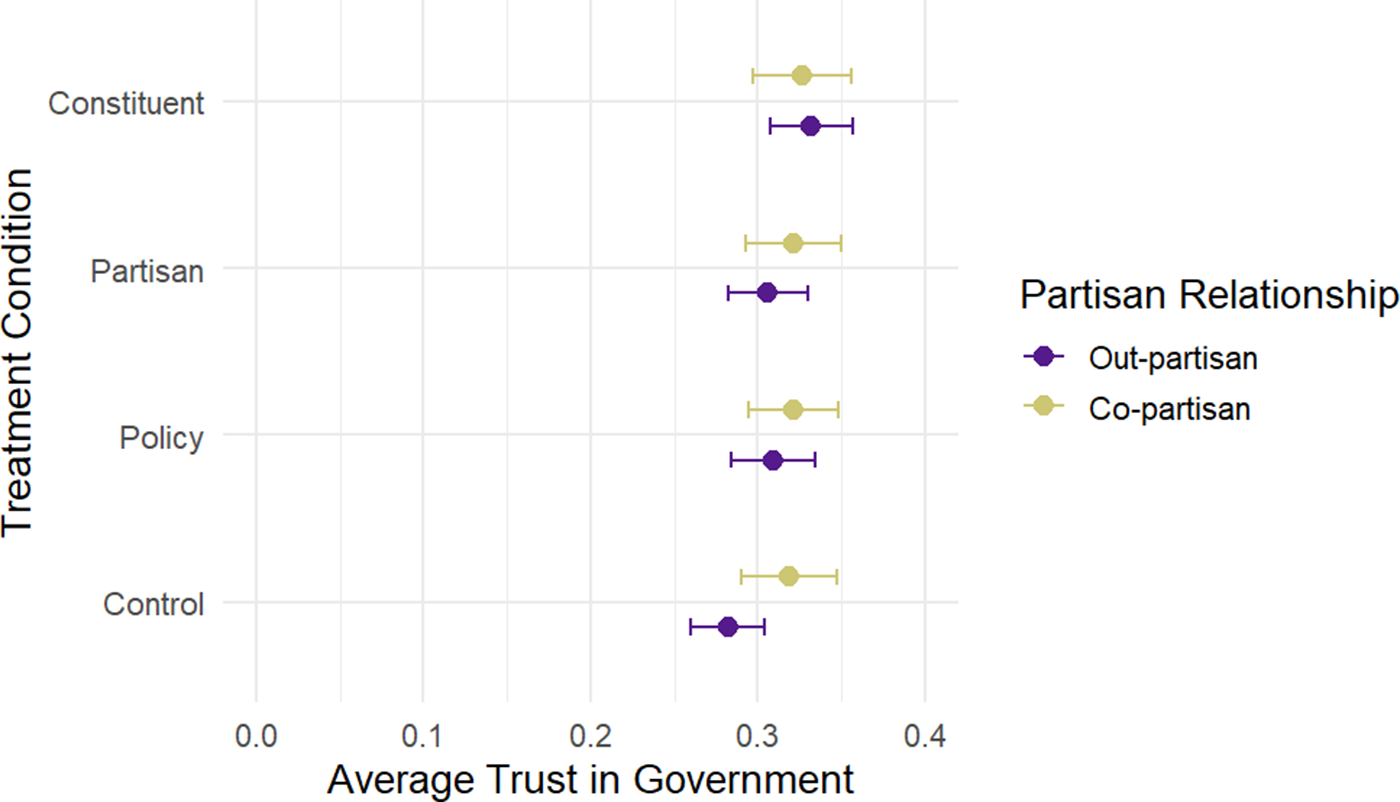

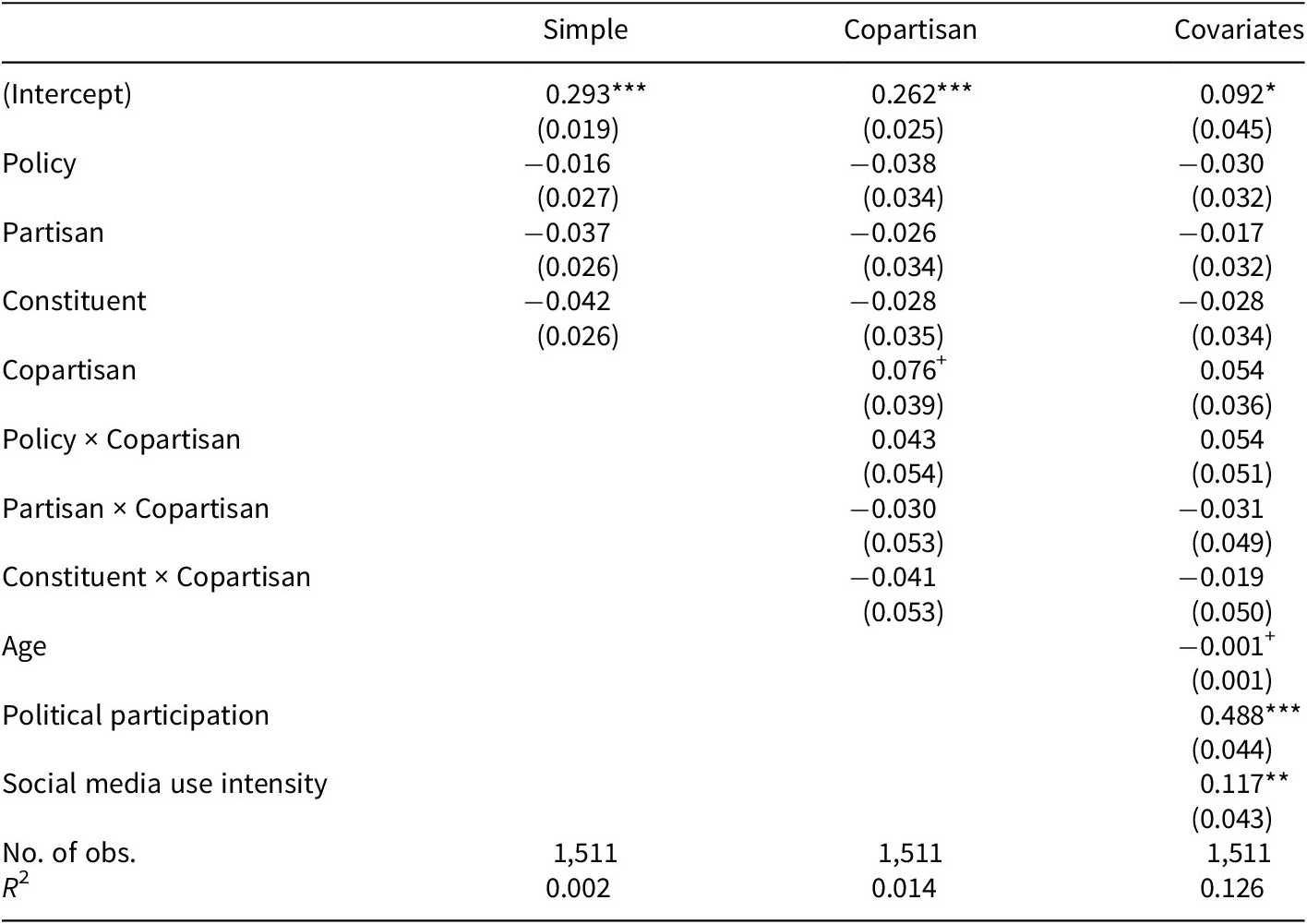

Table 2 displays the results from all three treatment conditions on the respondents’ trust in government. The policy and partisan treatment conditions do not have a statistically significant impact on trust, whereas the constituent service treatment has a small, statistically significant, positive impact on respondents’ trust compared with the apolitical control condition. The small positive impact of the constituent service treatment is stronger for copartisans, but there is no statistically significant interaction between the constituent service treatment and shared partisanship. Both groups experience an increase in their trust relative to the control treatment.

Table 2. Treatment effects on ANES trust in government

+ p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 4 shows that the average values of respondents’ trust are lowest among the control group when they see an out-party member. The control conditions do not emphasize any political action or policy plans, but do label the posters as partisan state legislators (Table 1). As the policy and constituent service treatments, in particular, were written to be widely accepted by Republican and Democratic partisans, it is possible that viewing the apolitical control posts from out-party members reminded respondents of negative stereotypes they associate with the out-party. Outpartisan legislators who are engaging in politics may be more palatable than those who appear to be shirking their responsibilities, though future work would need to investigate this possibility.

Figure 4. Average Trust in Government by Partisan Relationship.

Note: There are no statistically significant effects on respondents’ average trust in government by copartisan relationship.

Potential for participation

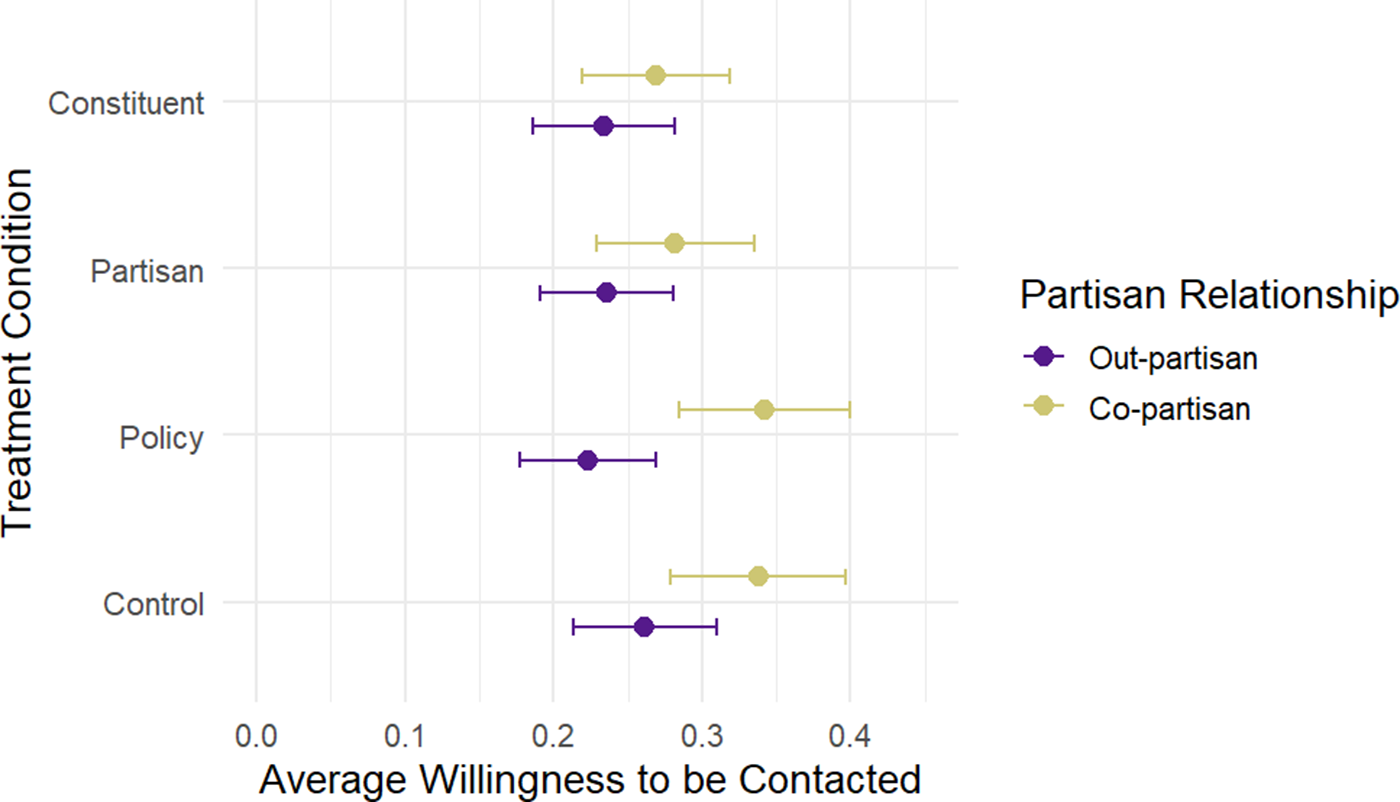

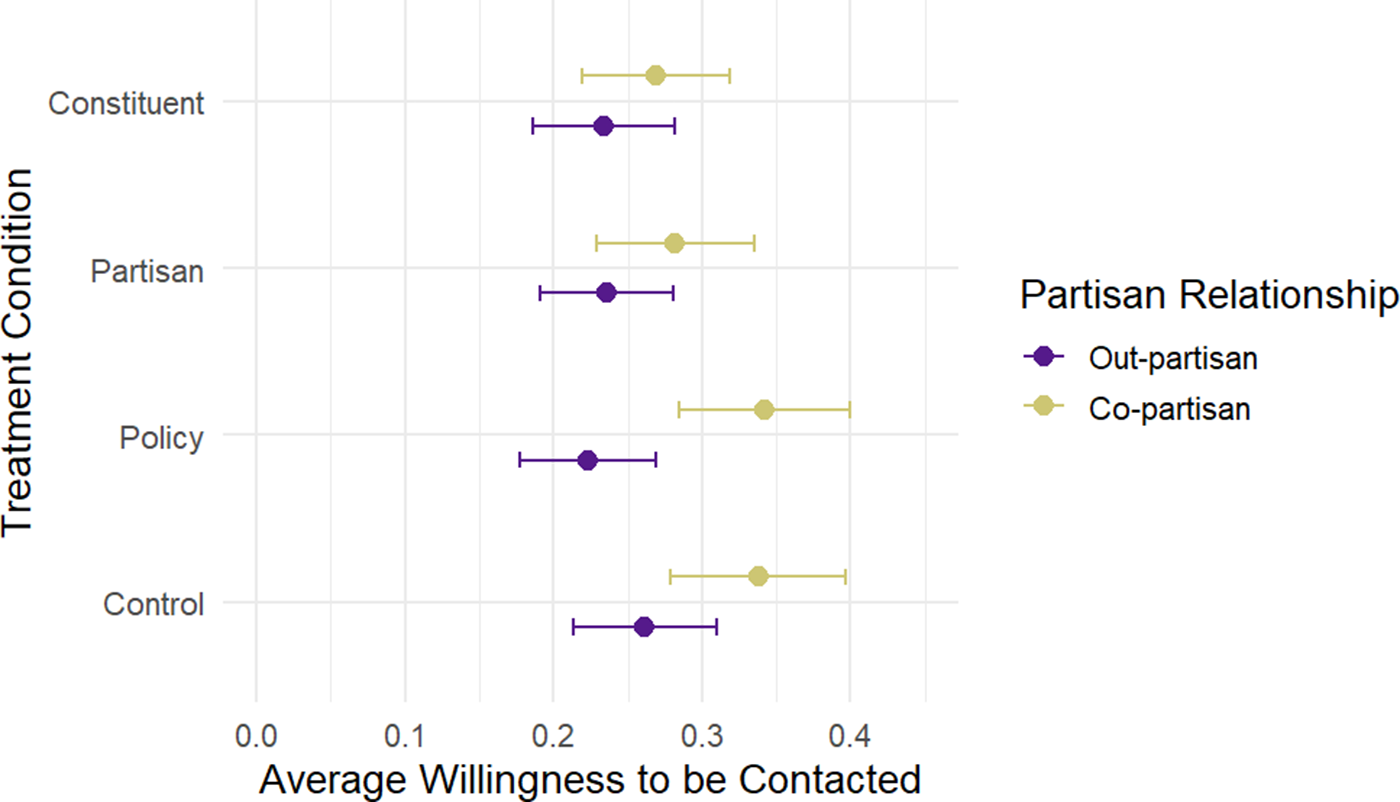

The presence of political actors on social media, in theory, could encourage individuals to engage in politics by increasing their political knowledge or by acting as a venue for constituent casework (Serra and Pinney Reference Serra and Pinney2004). However, a few posts from previously unknown legislators who are seen as successfully doing their job are not enough to move individuals toward political engagement. I expected posts engaging in constituent service or popular policy to have a neutral impact on respondents’ willingness to be contacted by their state-level party organization. However, more divisive partisan posts, whether insulting copartisans or outpartisans, might work to mobilize individuals for their preferred party in a manner similar to how aggressive out-group posts often gain increased attention online (Rathje, Van Bavel, and van der Linden Reference Rathje, Van Bavel and van der Linden2021). For this reason, I expected partisan posts to inspire copartisans and outpartisans to agree more readily to be contacted by their preferred party.

All three treatment conditions resulted in statistically insignificant decreases in respondents’ willingness to be contacted by members of their preferred state party compared to the control condition (Table 3). This remains true even when accounting for additional covariates in the model. Figure 5 demonstrates the average willingness of respondents viewing copartisans’ versus outpartisans’ posts. Despite the outcomes question asking about engaging with their preferred in-state party organization,Footnote 12 respondents who viewed copartisan posts in the social media environment maintain a consistently higher expected willingness to be contacted, though the relationship is not statistically significant (Figure 5). This potential relationship could be explained through an invigorating experience of seeing copartisans online for some respondents, or via a demoralizing impact of seeing outpartisans. In either case, political actors who are invested in party politics could view this as a beneficial effect.

Table 3. Treatment effects on potential political participation

+ p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 5. Average Willingness to be Contacted by Partisan Relationship.

Note: There are no statistically significant treatment effects on willingness to hypothetically participate in politics, regardless of copartisan relationship.

Conclusion

In many ways, social media is just another event in a centuries-old telecommunications revolution (Epstein Reference Epstein2018). However, it has never been this easy for the legislator–constituent relationship to be reciprocal. Legislators who decide to post online can theoretically receive real-time feedback from constituents or even find donors outside of their districts. It is not surprising that so many legislators have adopted social media. Most studies of the political use of social media have, for a variety of reasons, focused on the types of posts which political actors supply (i.e., Russell Reference Russell2021). In the instances where the impact on the public has been the focus, the posts have been from the most elite levels of government, especially Donald Trump (Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Davis, Nyhan, Porter, Ryan and Wood2021). But do the rhetorical or topical choices of legislators online matter?

In this study, I find posts focusing on constituent service, policy positions, and partisan politics can have a direct, if modest, effect on individuals’ attitudes, even when coming from unknown state legislators in a simulated social media environment. These posts influence individuals’ evaluations of the legislators in question, and in some cases, trust in government. However, I do not find evidence that these social media posts are effective in mobilizing individuals to be more directly involved in the political process.

The empirical results of this study can speak only to the short-term impact of three posting strategies that the literature expects from legislators. The survey sample was also representative of the gender, age, racial, ethnic, and partisan trends present in the US population. However, actual state legislators not only have a smaller target audience to consider, but can also repeatedly post similar messages in hopes of a cumulative effect on their constituency. Partisan posts, for example, may work particularly well on highly ideological copartisans, while constituent service might sway moderates with low interest in politics. Observational data may be more applicable in testing the potential of long-term effects in the future.

The American public and political elite are online, and scholars and media pundits alike have posited that this paints a bleak picture for American democracy. However, it is possible that state legislators’ use of social media could not only help them achieve their priorities (Grimmer Reference Grimmer2013; Mayhew Reference Mayhew2004), but could also help to inform citizens on important local issues, working to fill a pressing gap (Hayes and Lawless Reference Hayes and Lawless2018; Rogers Reference Rogers2023b). Past research has shown that legislators can experience direct benefits from participating in social media (Kowal Reference Kowal2023; Mousavi and Gu Reference Mousavi and Gu2019), but this study demonstrates a pathway for the public to benefit as well. Social media is a complex tool, constantly changing. However, the picture may not be as bleak as many make it out to be.

The inherent limitations of survey experiments were combated in as many ways as feasibly possible. Cloud Connect demonstrates high attentiveness relative to many other survey companies (Stagnaro et al. Reference Stagnaro, Druckman, Berinsky, Arechar, Willer and Rand2024), and an attention check was asked prior to random assignment. The majority of respondents passed two fact-based manipulation checks about their assigned treatment.Footnote 13 Additionally, I worked to ground both treatment and filler posts in realism, but was bound by the inherent limitations of survey experiments and sample size. The policy and partisan posts, in particular, could have been written in a much stronger tone if they did not have to be believable coming from both Democratic and Republican legislators with minimal word changes.

Future work could build on this study, most simply by including a durability check. While I used common rhetorical strategies from legislators, I was limited by sample size on the number of topics, and I did not test for different levels of excitement or anger from the legislators. Additionally, this work does not address potential biases that respondents have based on legislators’ race, gender, sexuality, physical appearance, or cross-cutting identities. It would also be worth investigating the different reactions the public has to political posts from elected officials across different levels of government, or comparing the impact of traditional media figures and seemingly random posters on social media. Finally, these political posts do not display comments or other forms of public engagement, which might alter respondents’ perceptions and reactions. There is significant room for further study regarding how social media environments are impacting American politics.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/spq.2025.10011.

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available on SPPQ Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DKPWUB (2025).

Funding statement

The funding for the research in this article was provided by the Rooney Democracy Institute and the Representation and Politics in Legislatures Lab, both affiliated with the University of Notre Dame.

Competing interests

The author declares no potential competing interests with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Abigail Hemmen is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Notre Dame. Her primary research interests are in representation, state politics, and social media.