Despite its authoritarian Islamist stance and history of fostering conservative gender norms, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) of Turkey has increasingly nominated women mayoral candidates in districts dominated by the secular Republican People’s Party (CHP). These candidates, portrayed as modern and secular professionals, contrast with the AKP’s traditional approach to gender roles, raising questions about the motivations behind these nominations. Are these women nominees merely placeholders in unwinnable districts, or is the AKP deliberately leveraging their secular image for electoral gain?

Understanding the significance of these questions necessitates recognizing the symbolic politics surrounding women’s identities in Turkey, particularly within the context of the Islamist-secularist divide. This divide has profoundly shaped voting behavior for decades, with women’s identities and the practice of (non)veiling central to the symbolic contestations between these groups (Bilgin Reference Bilgin2018). The headscarf, notably, has become a potent symbol of religious orientation, laden with partisan symbolism and influencing stereotypes associated with women’s intersecting identities. Today, this deep-seated division overlaps with a broader polarization between democratic and authoritarian-leaning voters, impacting electoral competitions, especially in western Turkey, between the Islamist AKP and the secularist CHP, and placing Turkey third globally in rankings of partisan polarization (Lauka, McCoy, and Firat Reference Lauka, McCoy and Firat2018).

Existing research has shed light on the strategic inclusion of women in politics, particularly within authoritarian regimes, underscoring how such inclusion often cater to the self-serving interests of male elites rather than genuine advancements in gender equality (Bjarnegård and Zetterberg Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2022; Bush and Zetterberg Reference Bush and Zetterberg2024). Furthermore, the literature recognizes the intricate interplay of intersecting identities and (non)veiling in influencing political inclusion, especially within the context of Muslim-minority countries in Europe (Celis and Erzeel Reference Celis and Erzeel2017, Dancygier Reference Dancygier2017; Murray Reference Murray2016). However, much remains unexplored regarding how these dynamics function within authoritarian, Muslim-majority contexts, where the interplay between Islam, secularism, gender, and the symbolic politics of (non)veiling present unique complexities in elections.

To bridge this gap, this study examines whether party elites in Turkey strategically leverage the political symbols associated with women’s (non)veiling to compete in rival party strongholds — a strategy I term “symbolic leverage.” I argue that in electorally challenging districts, particularly those marked by affective polarization where veiling is central to partisan contestations, party elites utilize symbolic leverage to broaden their appeal and enhance their competitiveness. Yet, the strategic use of symbolic leverage differs across parties depending on their ideological/religious orientation and position of power within a given district. Specifically, right-wing and Islamist parties are expected to nominate more nonveiled female candidates in secular strongholds compared to conservative districts, while the secular party is expected to nominate more veiled candidates in conservative districts. Additionally, the number of nonveiled female candidates nominated by the dominant Islamist party is expected to increase as secularist sentiments and negative partisanship increase within a district. To analyze these strategic nominations of veiled and nonveiled women candidates, this study utilizes an original dataset of 1,734 candidates from major parties in Turkey’s 2019 mayoral elections. The study also considers local variations in party affiliations and the influence of partisan polarization on vote choice. Furthermore, to gain deeper insights into the motivations behind this strategy, it draws on 21 in-depth interviews with high-profile party elites, supplemented by an electoral discourse analysis, including campaign speeches and media interviews.

Aligned with the hypotheses, the findings reveal that political parties in Turkey strategically utilize the symbolic value of women’s veiling status to appeal to voters of rival parties and gain a competitive advantage, particularly in highly polarized electoral contexts. All parties, to some extent, use the symbolism of (non)veiling to maximize their electoral gains, especially in districts with deeply entrenched opposition. Right-wing and Islamist parties, particularly the Islamist AKP, strategically field nonveiled women candidates to leverage the symbolic value of their appearance, especially in electoral races where they face strong secularist opposition. As these women project a secular image, this strategy serves multiple objectives: signaling tolerance for secular lifestyles, assuaging concerns about Islamization, attracting swing voters, and projecting a commitment to democracy and gender equality.

Similarly, the CHP employs this strategy by increasing the presence of veiled women both as candidates in conservative districts and within the party organization. This signals a shift away from the party’s past exclusion of religious identity and its strict position on the headscarf ban. By softening its image, the CHP seeks to appeal to conservative voters who may have previously hesitated to support the party due to its perceived secular rigidity. Conversely, the CHP nominates fewer nonveiled women in its strongholds, as the need to visually signal its secularism is reduced since the party label itself conveys that message. Overall, these findings demonstrate how parties strategically utilize symbols attached to women’s bodies to appeal to specific voter groups and maximize their vote share within a deeply polarized political landscape.

This study introduces a novel theory of symbolic leverage to explain how party elites strategically deploy women’s (non)veiling status for electoral gain in highly polarized Muslim-majority context of Turkey. While similar dynamics exist in Western nations with Muslim minorities, this research foregrounds affective polarization and political symbols as the driving force shaping both the strategic inclusion of women in politics and its instrumentalization within broader electoral campaigns. Elites’ decisions regarding female candidate nominations are profoundly shaped by deeply entrenched cultural cleavages, particularly where women’s identities become battlegrounds of symbolic contestation. Party elites strategically utilize women’s intersecting identities as potent political symbols that resonate with specific segments of the electorate. They leverage these symbols to signal their stance on polarizing cultural values and to attract voters across the political divide. These findings show that women candidates are not mere tokens relegated to unwinnable districts; they are strategically selected to compete in challenging districts where their identities offer distinct electoral advantages to party elites. The empirical evidence offers insights into how these mechanisms are operationalized, providing a nuanced understanding of party elites’ motivations for including women under specific electoral competition conditions where leveraging women’s (non)veiling status is a rational tactic. This research contributes to political theory and practice by demonstrating the decisive impact of affective polarization, particularly surrounding cultural issues, on elite candidate selection strategies and the broader trajectory of women’s political inclusion. By illuminating the intricate interplay between gender, political symbols, polarization, and electoral strategies, this research offers a comprehensive understanding of how women’s identities are strategically deployed and actively contested in the political arena. Moreover, it challenges the view of women as passive nominees, highlighting their agency as strategic actors advancing their careers in various political positions by taking on risky candidacies that benefit male elites. This study therefore significantly advances the literature on the strategic inclusion of women in politics, with implications for both democratic and authoritarian contexts.

Elite Strategy Toward Women’s Political Inclusion in Authoritarian Regimes and Politics of Veiling in Elections

While the inclusion of women in politics is frequently portrayed as a progressive advancement toward gender equality, closer scrutiny reveals that such inclusion, particularly within authoritarian regimes, may be driven by the self-serving interests of male elites (Bjarnegård and Zetterberg Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2022). This phenomenon, commonly referred to as “genderwashing,” serves multifaceted purposes for elites, both domestically and internationally. It functions to bolster regime legitimacy; deflect attention from undemocratic practices, corruption, and human rights violations; and construct a facade of inclusivity and democracy, ultimately enhancing the country’s image on the global stage while simultaneously consolidating power domestically (Benstead and Sari-Genc Reference Benstead and Sari-Genc2024; Bjarnegård and Donno Reference Bjarnegård and Donno2024; Bjarnegård and Zetterberg Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2022; Bush and Zetterberg Reference Bush and Zetterberg2024; Tripp Reference Tripp2019, Reference Tripp2024). Furthermore, at the subnational level, autocratic elites may strategically increase women’s representation in districts with progressive electorates to broaden their base of support (Tripp Reference Tripp2024).

However, existing research often examines women as a homogenous group, overlooking the crucial fact that the strategic value of including women in politics can differ significantly based on their intersecting identities other than gender. Although the concept of intersectionality originated in acknowledging the multiple barriers encountered by Black women (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991), it has evolved into a broader research paradigm and analytical tool (Hancock Reference Hancock2007a; Reference Hancock2007b; McCall Reference McCall2005).Footnote 1 By examining the dynamics of intersectionality in political representation, scholars have demonstrated that these intersecting identities can confer strategic advantages, influencing party nominations and access to political office (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2013; Celis and Erzeel Reference Celis and Erzeel2017; Fraga et al. Reference Fraga, Martinez-Ebers, Lopez, Ramírez and Reingold2008; Hughes Reference Hughes2016; Murray Reference Murray2016; Scola Reference Scola2014). For instance, parties may strategically select minority women to fulfill demands for both gender and ethnic diversity (Celis and Erzeel Reference Celis and Erzeel2017; Mügge and Erzeel Reference Mügge and Erzeel2016). This strategic selection extends to Muslim-minority women in Western democracies, where political elites are responsive to the perceived symbolism associated with veiled and nonveiled candidates (Hughes Reference Hughes2016). For example, the inclusion of Muslim women in French politics hinges upon their embrace of secularism and assimilation, often manifested in their choice not to wear the veil. Thus, parties often favor nonveiled Muslim women to project an image of successful integration (Murray Reference Murray2016) while Muslim men are sometimes prioritized for their ability to mobilize bloc votes (Dancygier Reference Dancygier2017).

While existing research has elucidated the strategic inclusion of nonveiled Muslim women in elections within democratic, Western, Muslim-minority contexts, the extent to which such tactical considerations operate within authoritarian, Muslim-majority contexts remains understudied. Turkey’s unique trajectory, marked by a secularist-Islamist divide with veiling holding a pivotal role, and its recent shift to authoritarianism under the Islamist AKP, sets it apart from both European and other Muslim-majority contexts, making Turkey a compelling case study for examining how elites leverage the symbolic value of (non)veiling in elections. The following section delves into the Turkish case, elucidating the significance of the symbolic politics of (non)veiling and the enduring divide between Islamists and secularists in politics.

Secularist-Islamist Polarization, Women’s Representation, and (Non)Veiling in Turkey

Despite Turkey’s geographical location in the Middle East, the trajectory of women’s political participation in the country diverges from the rest of the region. The modernization reforms cultivated a novel ideal of the Turkish woman as modern, secular, and educated (Drechselová Reference Drechselová2020). During this process, Kemalist leaders assigned women a pivotal role, portraying them as Westernized, modern, and well-educated symbols of the emerging nation-state, both domestically and internationally (Aslan Reference Aslan2022; Arat Reference Arat, Bozdoğan and Kasaba1997; Tekeli Reference Tekeli1982; Zihnioglu Reference Zihnioglu2003). Integral to these efforts were the unveiling campaigns (Adak Reference Adak2022). The Kemalists, viewing the veil as a symbol of submissiveness and a relic of the Ottoman era, promoted nonveiled women in educational and professional environments through propaganda posters, lifestyle magazines, and beauty contests (Adak Reference Adak2022; Shissler Reference Shissler2004).

To gain legitimacy from Western nations, the Kemalist regime progressively expanded electoral rights to Turkish women between 1930 and 1935 (Tekeli Reference Tekeli1982). By 1935, women comprised 4.5% of deputies in the Parliament, marking the highest rate of representation in Europe that year. However, following the transition to multiparty elections in 1946, representation plummeted to 0.3% and remained below 5% until 2007 (Drechselová Reference Drechselová2020). Currently, women constitute 19.83% of the Turkish Parliament (Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi n.d.). At the local level, women’s representation is even lower, making up only 7.2% of mayors and 12.2% of councilors after the 2024 local elections (Supreme Election Council 2024).

In Turkey, supply-side factors present significant barriers to women’s involvement in politics (Drechselová Reference Drechselová2020). Traditional gender roles and societal expectations often confine women to domestic spheres, discouraging political aspirations (Sumbas Reference Sumbas2020). Despite increasing female higher education graduation rates, reaching nearly 22% in 2022 (Turkish Statistical Institute n.d.), these norms persist, hindering their political engagement. Economic disparities, including a substantial gender pay gap where college-graduate women earned, on average, 17% less than men in 2022, further impede their ability to fund campaigns (Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu 2025). Moreover, male-dominated political party structures and limited access to political networks restrict women’s opportunities (Drechselová Reference Drechselová2020). Violence and harassment against women in politics create an intimidating environment, further deterring their participation (UN Women 2023). These factors collectively contribute to women’s persistent underrepresentation in Turkish politics.

However, a key constraint lies in the limited demand for women candidates driven by strategic considerations of political parties. In Turkey, candidate selection is highly centralized, with top-level party elites determining party list placements. While some parties occasionally use primary elections, candidate competition primarily occurs in Ankara for both local and national elections (Bayraktar and Altan Reference Bayraktar and Altan2012; Joppien Reference Joppien2019). The pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP) is a notable exception, employing an inclusive selection process involving the entire party, labor unions, leftist groups, and minority associations.Footnote 2

Although legislated gender or minority quotas are absent, most parties have nominal provisions for women’s representation, which are frequently disregarded. Right-wing parties, such as the AKP and MHP, oppose official gender quotas, yet the AKP maintains an informal rule of including at least one woman in electable positions on Proportional Representation lists (Değirmenci Reference Değirmenci2015; Drechselová Reference Drechselová2020). Conversely, left-wing parties, the CHP and HDP, have implemented voluntary party quotas. While the CHP’s 33% voluntary quota has not yet been achieved, the HDP has a 50% gender quota and a cochair system, ensuring joint leadership by a woman and a man. According to the 2023 election results, women constitute 47.37% of the HDP’s Members of Parliament (MP), compared to 18.94% for the AKP and 18.46% for the CHP (Supreme Election Council of Republic of Türkiye n.d.).

Beyond supply and demand-side barriers, Turkey’s political context and historical trajectory significantly influence women’s representation. The secularist-Islamist divide in particular has influenced women’s political participation in Turkey, shaping the landscape of party politics since the transition to competitive elections. In the 1980s, the imposition of a headscarf ban in public institutions politicized veiling, effectively excluding veiled women from public life, including universities (Yavuz Reference Yavuz2003). In the 1990s, Islamist parties assumed ownership of the headscarf ban issue, utilizing the imagery of veiled women as a counter-symbol to challenge the Kemalist ideology. They promoted veiling as a means of self-empowerment for Muslim women (Göle Reference Göle2003; Sawae Reference Sawae2020; Yavuz Reference Yavuz2003). During this period, anti-system Islamist parties achieved significant electoral success, with one joining a coalition government in 1996. However, a 1997 military memorandum, the “postmodern coup,” forced the coalition’s resignation due to perceived anti-secularist threats (Aydın and Taskin Reference Aydın and Taşkin2014). In 1999, the first veiled women elected from an Islamist party was barred from taking her parliamentary oath due to wearing a headscarf in Parliament. Against this historical backdrop, the headscarf has become central to electoral competition between secularist and Islamist parties.

In 2002, the ascension to power of an Islamist party, the AKP, intensified the secularist-Islamist divide. This development sparked concerns among secularists about a potential deviation from the modernization reforms and a shift toward Islamization under the AKP governments (Aydin-Duzgit Reference Aydin-Duzgit and Carothers2019). In 2007, as the parliament was on the verge of electing an Islamist candidate whose wife wears a headscarf as the President of the Republic, mass demonstrations, known as “Republican Rallies,” were held across major cities. The primary objective of the protesters was to deter the government from modifying the secular principles and transforming Turkey into an Islamist state (Aydin and Taskin Reference Aydın and Taşkin2014). Concurrently, the AKP has invoked the headscarf ban in its electoral campaigns over the past two decades (Öztürk, Serdar, and Nygren Reference Öztürk, Serdar and Nygren2022). As a result, the divide between secularists and Islamists has not only deepened but also emerged as one of the dominant cleavages in contemporary Turkey.

As of today, Turkey ranks third globally in mass partisan polarization, characterized by negative partisanship and a societal divide along secularist and conservative lines that significantly influences voting behavior (Lauka, McCoy, and Firat Reference Lauka, McCoy and Firat2018; Somer Reference Somer2022). Secular voters, typically educated, young, urban, middle, and upper-class, tend to oppose the AKP, while conservative voters, often less educated, religious, rural, and lower-to-middle-class, tend to oppose the CHP (Konda 2019). This divide is reflected regionally: the Aegean region is predominantly secular, while East, Southeast, and Central Turkey is predominantly conservative. These regional variations also correlate strongly with attitudes toward veiling. Support for veiling is lowest in the secular Aegean region (20%–30%), and significantly higher in the predominantly conservative East, Southeast, and Central regions: 50% in Central Turkey and up to 70% in the East and Southeast (Nişancı Reference Nişancı2023).

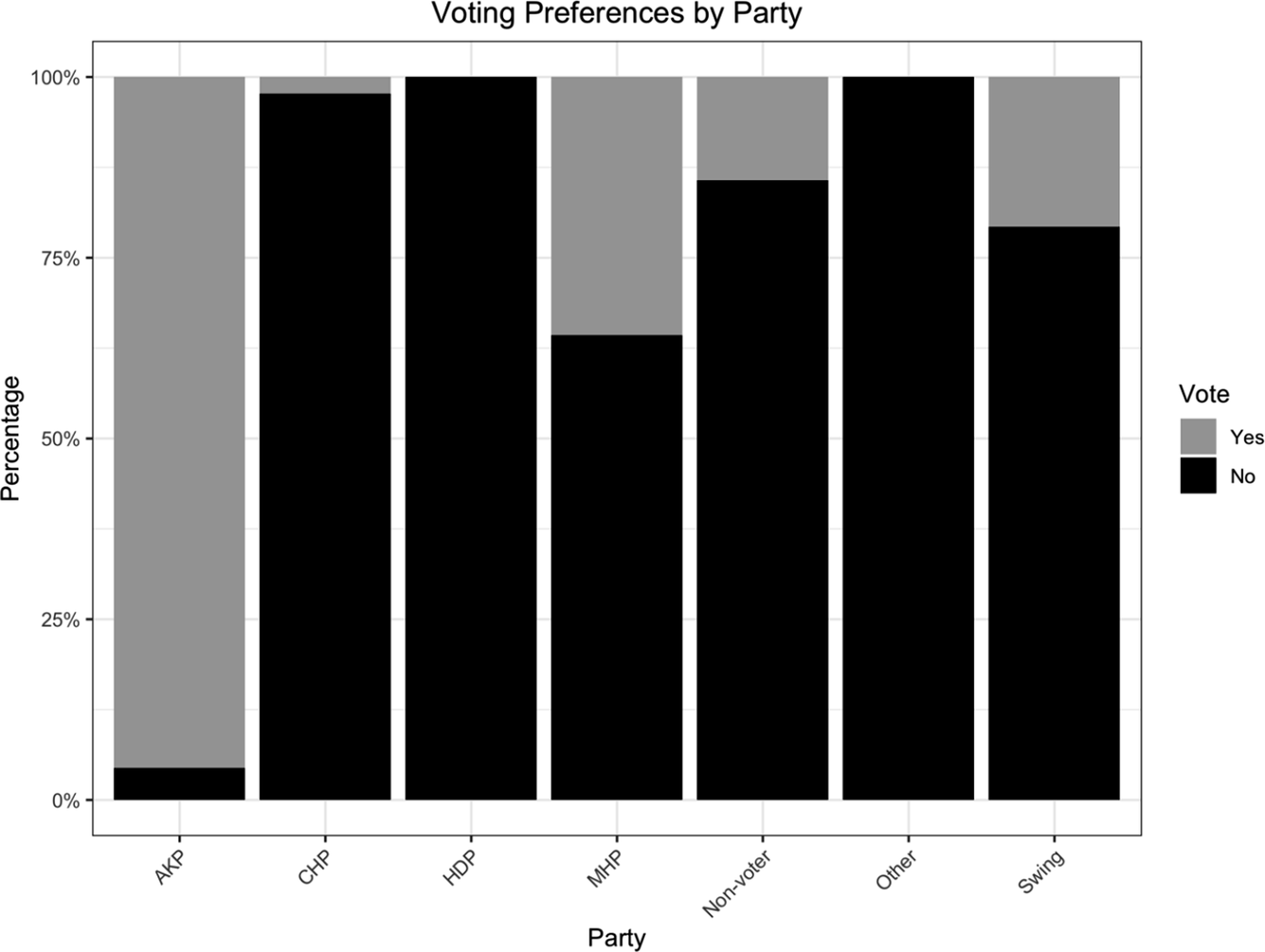

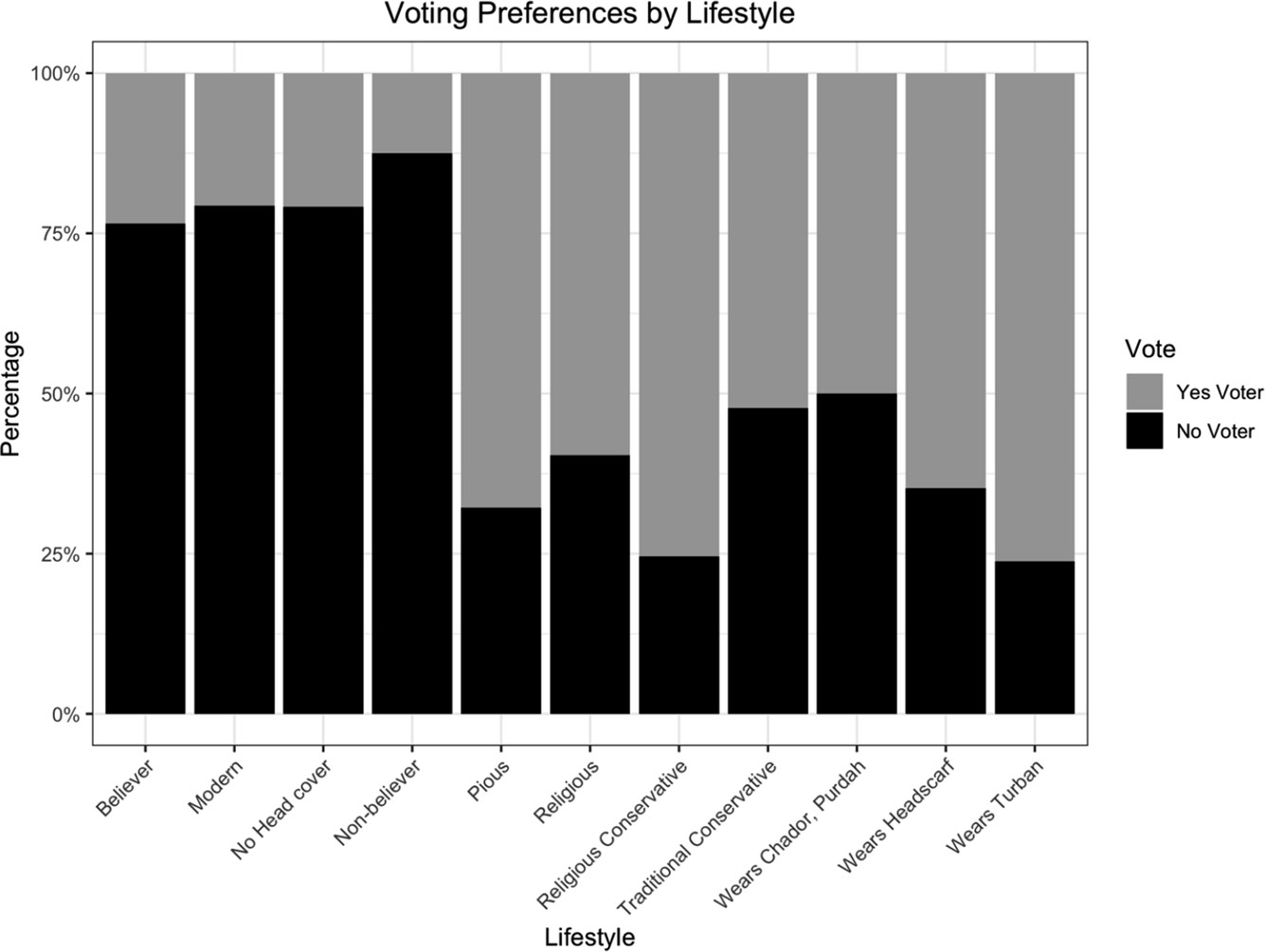

These regional disparities in attitudes toward secularism, conservatism, and veiling have been evident in the election results in the last two decades. Despite the AKP’s national dominance since 2002, its vote share in secular districts remains low. Conversely, the CHP maintains strength in Western and Mediterranean provinces (Tosun Reference Tosun2010). Democratic backsliding under the AKP has deepened the divide, with CHP supporters favoring parliamentary democracy and AKP supporters favoring Erdoğan’s authoritarian governance (Konda 2019; Selçuk and Hekimci Reference Selçuk and Hekimci2020; Somer Reference Somer2022). This dichotomy was obvious in the 2017 Constitutional Referendum results, where regions with CHP strongholds had high turnout rates and “No” votes (Figure 1). These “No” voters, identifying as modern and less religious, opposed the headscarf status, while AKP supporters, who are predominantly conservative, voted “Yes” (Konda 2019; Figures 1 and 2). As demonstrated in the preceding case, the symbolic politics of (non)veiling is central to partisan contestations in Turkey, influencing electoral preferences, and thus, candidate selection.

Figure 1. Yes/no distribution of the 2017 Constitutional Referendum by party preference.

Figure 2. Lifestyle identification of yes/no voters.

A Theoretical Framework of Symbolic Leverage in Electoral Competition

In Turkey, the enduring secularist-Islamist polarization, intertwined with the symbolic politics of veiling, profoundly influences how political parties approach the inclusion of women in their electoral strategies. To illuminate these dynamics within this Muslim-majority authoritarian context, I introduce the concept of “symbolic leverage.” This strategic maneuver involves deploying a female candidate’s veiling status (veiled or nonveiled) as a visual cue to shape voter perceptions and electoral choices. In electorally challenging districts marked by affective polarization in which (non)veiling is central to partisan contestations, party elites utilize this tactic to broaden their appeal. By nominating candidates whose identities resonate with local values — even those diverging from the party’s core ideology — they signal moderation and inclusivity, aiming to attract swing voters and voters from across the ideological spectrum. This calculated strategy allows party elites to signal their ideological stances and policy positions on polarizing issues, thereby enhancing their competitiveness.

Several factors amplify the significance of symbolic leverage as an electoral strategy. Notably, despite benefiting from partisan polarization in their strongholds, parties encounter significant district-level challenges due to geographically clustered opposition voters (Harvey Reference Harvey2016; Tosun Reference Tosun2010). This necessitates the strategic use of political symbols, even for the nationally dominant party, to align with local values and preferences in these contested districts. Furthermore, Turkey’s First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) system for mayoral elections, which incentivizes the cultivation of a Personal Vote (Carey and Shugart Reference Carey and Shugart1995), further intensifies this strategic approach. In these systems, parties prioritize candidate characteristics that resonate with voters, leading them to strategically employ symbolic leverage to maximize their vote share. These factors, combined with the secularist-Islamist polarization and its symbolically charged disputes over veiling, solidify symbolic leverage as a crucial electoral strategy. Given that Turkey’s electorate is deeply divided along secularist-Islamist lines (Laebens and Öztürk Reference Laebens and Öztürk2021; Lauka, McCoy, and Firat Reference Lauka, McCoy and Firat2018), and voters often rely on heuristics (Lau and Redlawsk Reference Lau and Redlawsk2001), a candidate’s appearance serves as a powerful visual cue, prompting elites to employ them as political symbols that resonate emotionally with voters and mobilize them (Brader Reference Brader2005; Marcus et al. Reference Marcus, Neuman, MacKuen and Crigler2007; Sears Reference Sears2001).

Within this framework, I argue that party elites strategically leverage the symbolic value of women’s identities, particularly in challenging competitive conditions exacerbated by high affective polarization. However, the strategic use of symbolic leverage differs across parties depending on their ideological/religious orientation and position of power within a given district. I hypothesize that right-wing and Islamist parties (AKP, SP, MHP, IYIP) are expected to show a pattern of nominating more nonveiled female candidates in secular CHP strongholds than in their own strongholds.

H1: Right-wing and Islamist parties (AKP, SP, MHP, IYIP) will show a pattern of nominating more nonveiled female candidates in secular CHP strongholds than in their own strongholds.

Conversely, the CHP, with its well-established secular identity, is likely to demonstrate a tendency to nominate fewer nonveiled female candidates in its strongholds compared to other parties. This suggests that the need to signal secularism through visual cues is less pronounced for the CHP since its party label sends such a signal. Based on this, I posit that:

H2: The CHP will demonstrate a tendency to nominate fewer nonveiled female candidates in its strongholds compared to other parties.

Yet, despite the overall underrepresentation of veiled women among its nominees, the party strategically deploys veiled female candidates in conservative districts. This strategy is designed to communicate a departure from its past exclusion of religious identity and the headscarf ban. By increasing the overall presence and visibility of veiled women, the CHP seeks to alter its image and signal a more inclusive approach to religious expression, thereby potentially attracting conservative voters who were previously alienated by its perceived secular rigidity. Therefore, I anticipate that:

H3: The CHP will exhibit a pattern of strategically nominating veiled female candidates in conservative districts.

Additionally, district-level factors, such as levels of economic development and education, play a crucial role in shaping electoral strategies and influencing party decisions on candidate selection. Generally, higher levels of female education and socioeconomic development correlate with secular attitudes and support for democracy, while lower levels of these factors indicate greater religiosity and less democratic concerns (Konda 2019). Consequently, negative partisanship against the AKP, due to its Islamist credentials and authoritarian rule, tends to be higher in these developed districts.Footnote 3 These factors incentivize the AKP to nominate more nonveiled women in these challenging areas.Footnote 4 This strategy aims to appeal to secular-leaning voters in districts where the AKP faces increased electoral difficulties. Thus, it is predicted that:

H4: In electoral districts with higher levels of socio-economic development, female educational attainment, and negative partisanship toward the AKP, the party shows a pattern of increasing the number of nonveiled female candidates compared to districts with lower levels of these factors.

These patterns illustrate how parties strategically adapt their use of symbolic leverage based on their ideology (secular vs. religious) and their position of power (opposition vs. ruling) at the local level. Opposition parties, facing greater electoral challenges in a given district, often utilize this tactic more extensively.

This theoretical framework of symbolic leverage illuminates the complex interplay between gender, religiosity, and electoral politics in Turkey, highlighting how parties strategically use women as symbols to navigate a deeply polarized context. The findings from descriptive statistical analyses align with the hypotheses presented earlier. Moreover, interviews with AKP elites, presented later in this study, offer compelling evidence in further support of these hypotheses, and provide rich insights into the strategic motivations behind candidate nominations. The following section details the data and methods employed in this study.

Data and Methods

To test these theoretical implications, I employ a mixed-methods approach, specifically an explanatory sequential design, combining descriptive data analysis and in-depth interviews, and supplemented electoral discourse analysis, including campaign speeches and media interviews of candidates. The process begins with a descriptive analysis of candidate selection trends, utilizing an original district-level dataset of 1,734 mayoral election candidates from 519 districts across 30 metropolitan municipalities in Turkey. These candidates represent six major political parties: AKP, CHP, MHP, HDP, IYIP, and SP. The FPTP system in mayoral elections provides a suitable case for this research, as it tends to foster personal vote cultivation. The unit of analysis is the district municipality. In addition, I incorporate district-level data from the 2014 and 2019 local elections, 2017 Constitutional Referendum results, female high school ratios, and socioeconomic development data, sourced from Turkey’s Supreme Election Council (SEC), the Turkish Statistical Institute, and the Ministry of Industry and Technology. The dataset also includes candidate gender, determined by first names, and veiling status, coded based on headscarf presence in public visuals.

Subsequently, I analyze in-depth interviews to understand party elite motivations for nominating (non)veiled women. I conduct semi-structured interviews with 21 male and female party elites from AKP, CHP, HDP, and IYIP.Footnote 5 Interviewees are selected based on their involvement in candidate selection, proximity to party leaders, election experience, and local party branch roles. A snowball sampling method is used to foster trust and encourage candid discussions about party strategies. Interviews focus on district-level factors influencing candidate selection and the impact of gender and intersecting identities. Data was collected in the summers of 2022 and 2023 in Ankara, Istanbul, Izmir, and Trabzon to ensure representativeness. Interviews are conducted in Turkish, transcribed, translated, and thematically analyzed. To maintain anonymity, identifiers are removed and pseudonyms are used when quoting interviewees. Interview data is further supplemented by an analysis of electoral discourse, including campaign speeches and media interviews.

Descriptive Analysis

Variables

To facilitate descriptive analysis, I construct dichotomous variables for candidates’ gender and veiling status: Nonveiled woman candidate (takes a value of 1 if the candidate did not wear a headscarf, 0 otherwise), Veiled woman candidate (takes a value of 1 if the candidate wore a headscarf, 0 otherwise), and Male Candidate (takes a value of 1 if the candidate is a male, 0 otherwise). I also create dichotomous variables for party strongholds based on election wins, which take a value of 1 if the party won the last two consecutive elections in 2014 and 2019 and 0 otherwise.Footnote 6 Likewise, I code left, right, and swing districts using these election results. The “No” vote rate in the 2017 Constitutional Referendum serves as a proxy for negative partisanship against the AKP (Figures 1 and 2). Additionally, this study incorporates district-level measures of socioeconomic development and female high school graduation ratio, proxies for gender equality and secularist sentiments. Socioeconomic development is represented by the standardized Socio-Economic Development Score (SEGE-2017) (Yilmaz et al. Reference Yilmaz, Gültekiin, Acar, Meydan, Işik, Kazancik and Özsan2017), which I derived by standardizing the raw data provided by the Ministry of Industry and Technology. Female high school graduation ratios are calculated using district-level education data from the Turkish Statistical Institute. My analysis proceeds in three steps: first, examining the number of male and female mayoral candidates across six parties; second, comparing the distribution of veiled and nonveiled female candidates nominated by each party across strongholds; and third, analyzing the distribution of these candidates across left, right, and swing districts. Finally, scatter plot analysis is employed to examine the relationship between the AKP’s nomination strategies and variations in district-level socioeconomic development, female high school graduation ratio, and the 2017 Constitutional Referendum “No” vote rate at the district level.

Results

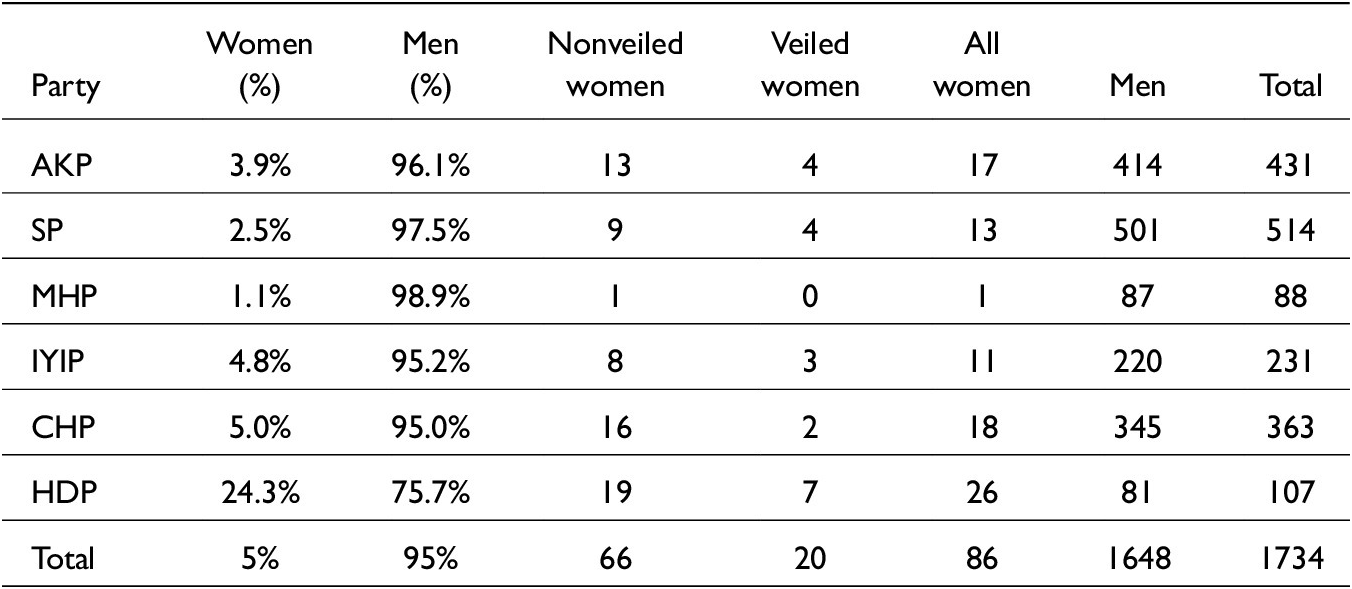

Table 1 displays the gender statistics of candidates who participated in the 2019 mayoral elections, categorized by party. It reveals that only 5% of the candidates were women. The AKP and SP, both Islamist right-wing parties, fielded 3.9% and 2.5% women candidates, respectively. The nationalist MHP, colloquially known as the “party of men,” exhibited the lowest at 1.1%. The IYIP spearheaded the right-wing parties with 4.8% women candidates, while the CHP reached the overall average at 5.0%, a very low percentage for a left-wing party. The HDP distinguished itself with a markedly higher percentage of women candidates at 24.3%, reflecting its commitment to gender equality.Footnote 7 In summary, while the HDP leads in terms of gender representation, the other parties are remarkably lagging in achieving gender parity.

Table 1. Percentage of women and men candidates by party

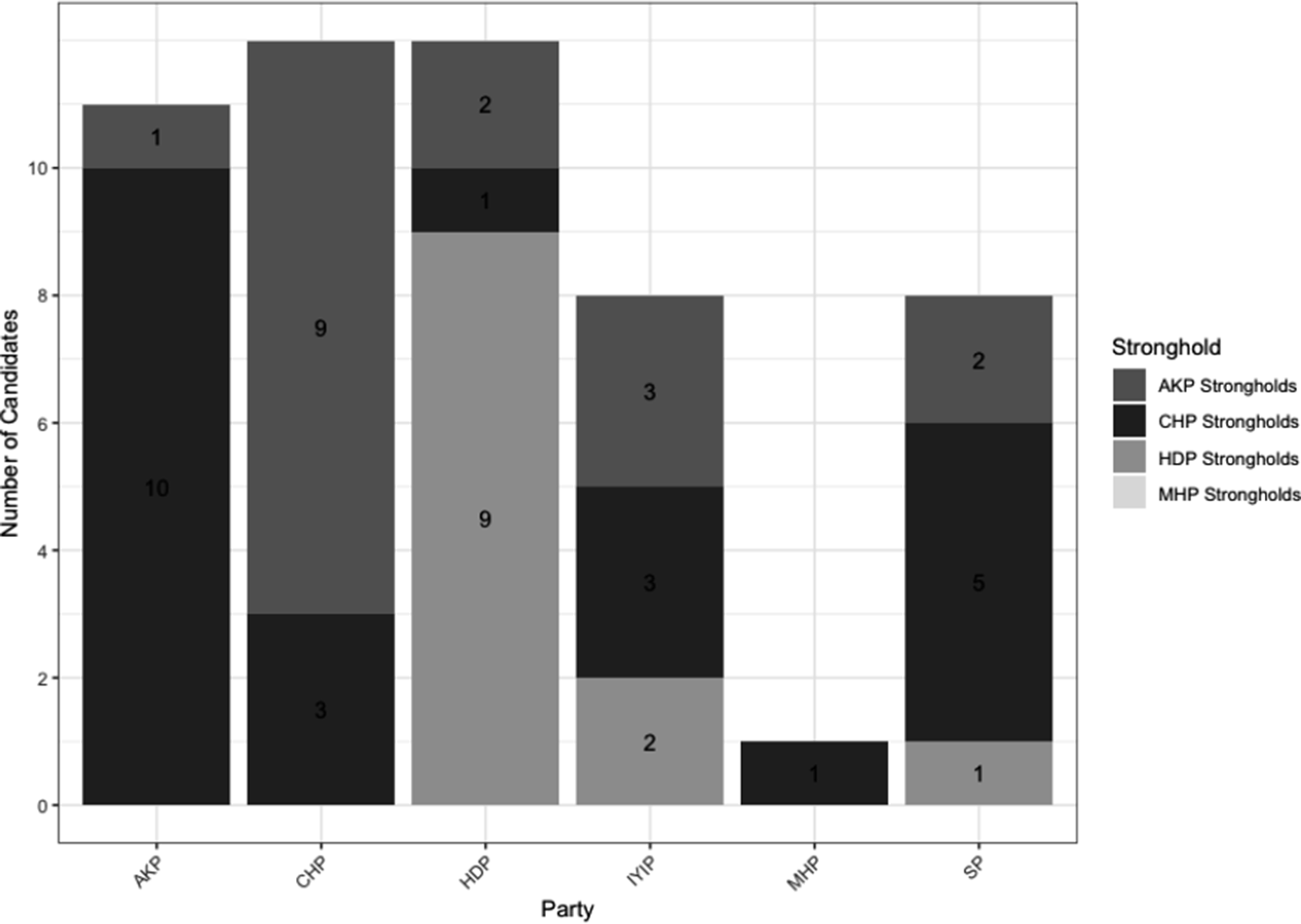

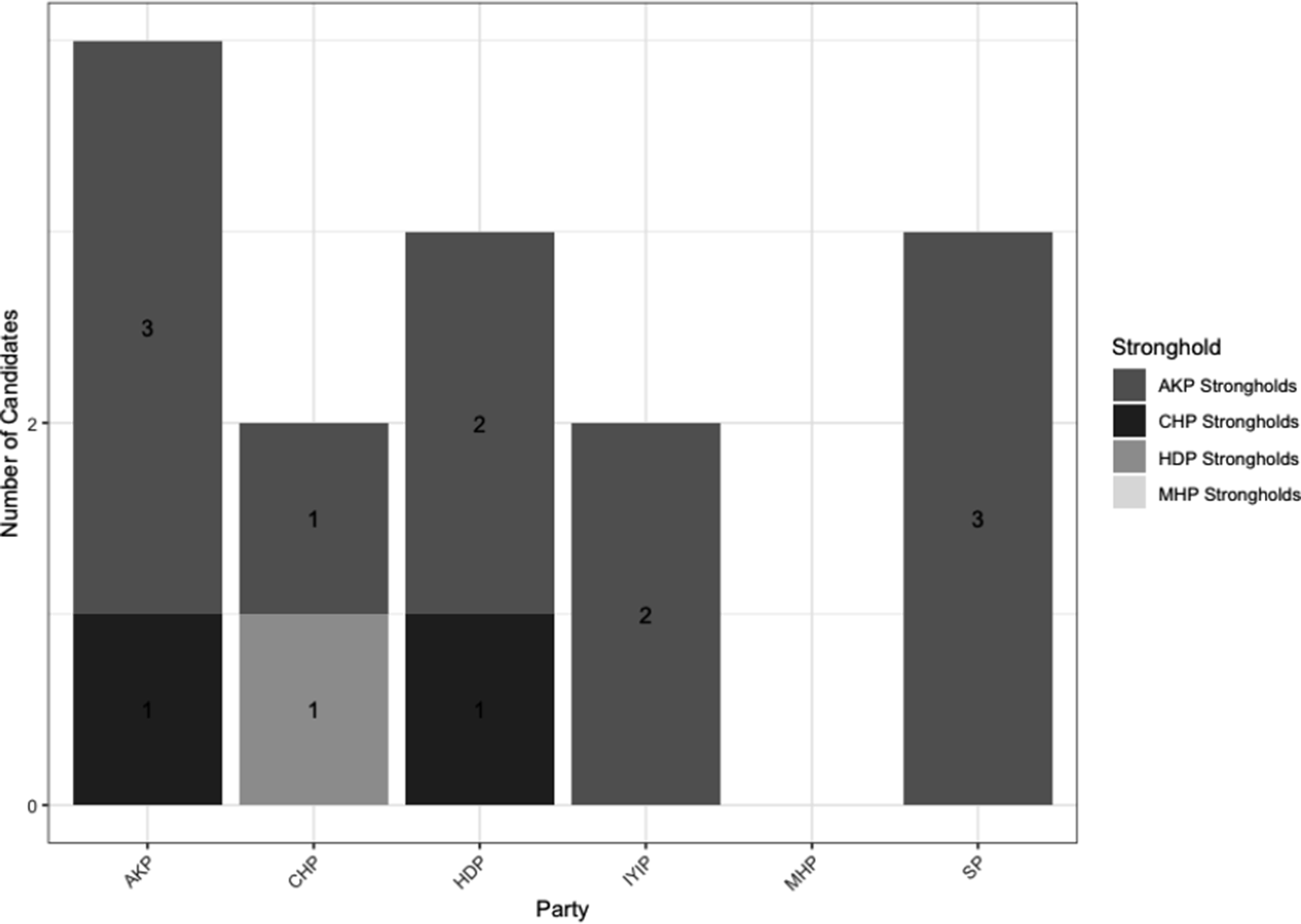

The descriptive analysis in Table 1 reveals that out of 86 female candidates, 66 project a secular appearance. Figures 3 and 4 present the distribution of nonveiled and veiled women candidates, respectively, across different party strongholds.Footnote 8 To begin with, nonveiled candidates were frequently nominated in districts dominated by left-wing parties — the CHP and the HDP — while veiled women were nominated in districts dominated by right-wing and conservative parties, especially in AKP strongholds. Nonveiled women candidates nominated by right-wing parties, including the AKP, SP, MHP, and IYIP, were primarily contested in CHP strongholds. The AKP nominated 13 nonveiled women, with 10 of them contesting in strongholds of the secular party, the CHP. This suggests a potential strategy aimed at appealing to the secular base within these districts. Likewise, the SP, another Islamist party, nominated nonveiled women predominantly in districts dominated by the secular CHP, further supporting this observation. The MHP only nominated one nonveiled woman candidate, and that was in a CHP stronghold. These findings offer support for H1. However, these parties nominated a comparatively low number of nonveiled women in the strongholds of the HDP, the other left-wing party. This is likely attributable to the fact that the HDP, despite being a left-wing party, is an ethnic party representing a Kurdish constituency known for its conservative stance and pronounced gender bias.

Figure 3. Nonveiled women candidates by party across stronghold type.

Figure 4. Veiled women candidates by party across stronghold type.

Conversely, the CHP nominated the majority of its nonveiled women candidates in AKP strongholds (nine), and only three in its own strongholds. This implies that the party assigns women to seats that are challenging to win. Furthermore, as the founding party of secular Turkey, the CHP’s label itself signals secularism. Therefore, the party’s selectorate does not necessarily nominate women who appear secular to appeal to secular voters. In other words, unlike the AKP, there is no strategic incentive for the CHP to nominate secular-appearing women to attract secular voters, indicating support for H2.Footnote 9

In contrast, only 20 of the female candidates who contested in metropolitan districts wore headscarves, signifying a conservative appearance. Figure 4 depicts the distribution of veiled women nominated by each party. The AKP nominated the majority of these veiled women, with most running in its own strongholds. The SP nominated three veiled women candidates in AKP strongholds, while this number was two for the IYIP. Notably, the secular CHP also nominated a woman candidate wearing a headscarf in an AKP stronghold in Konya, a city known as the capital of political Islam in Turkey, marking a significant shift in the party’s stance for the first time in Republican history.Footnote 10 Similarly, the CHP nominated a woman wearing a headscarf in Silvan, a stronghold of the HDP. In this region, the party competed against the AKP, which garners votes from conservative Kurds. During the local elections of 2019, the CHP and the HDP formed a de facto coalition with the aim of mutually supporting each other in their competition against the AKP. The essence of this coalition was that both the CHP and the HDP nominated candidates tactically, in order to appeal to constituents likely to vote for the AKP and thereby divide their vote share.Footnote 11

These initial instances provide compelling evidence that the CHP also strategically leverages the religious orientation of women, suggesting support for H3. The party has indeed accentuated the presence of conservative women in its 2023 election campaign across all its social media platforms. In 2020, Sevgi Kılıç became the first woman member of the CHP party council wearing a headscarf, and she was subsequently nominated as a candidate by the CHP in the 2023 national elections. These endorsements, coupled with direct speeches from the CHP’s then-leader, Kılıçdaroğlu, to conservative women disseminated through his Twitter account during the 2023 national elections campaign, formed a key component of the party’s strategy to appeal to the conservative base of the AKP (Sari-Genc Reference Sari-Genc2025).Footnote 12 These moves elicited criticism from the AKP, which accused the CHP of hypocrisy. Although the number of such instances is small and not suitable for studying with candidate data, these instances suggest that both pillars of the Islamist-secularist divide leverage the (non)veiling of women.

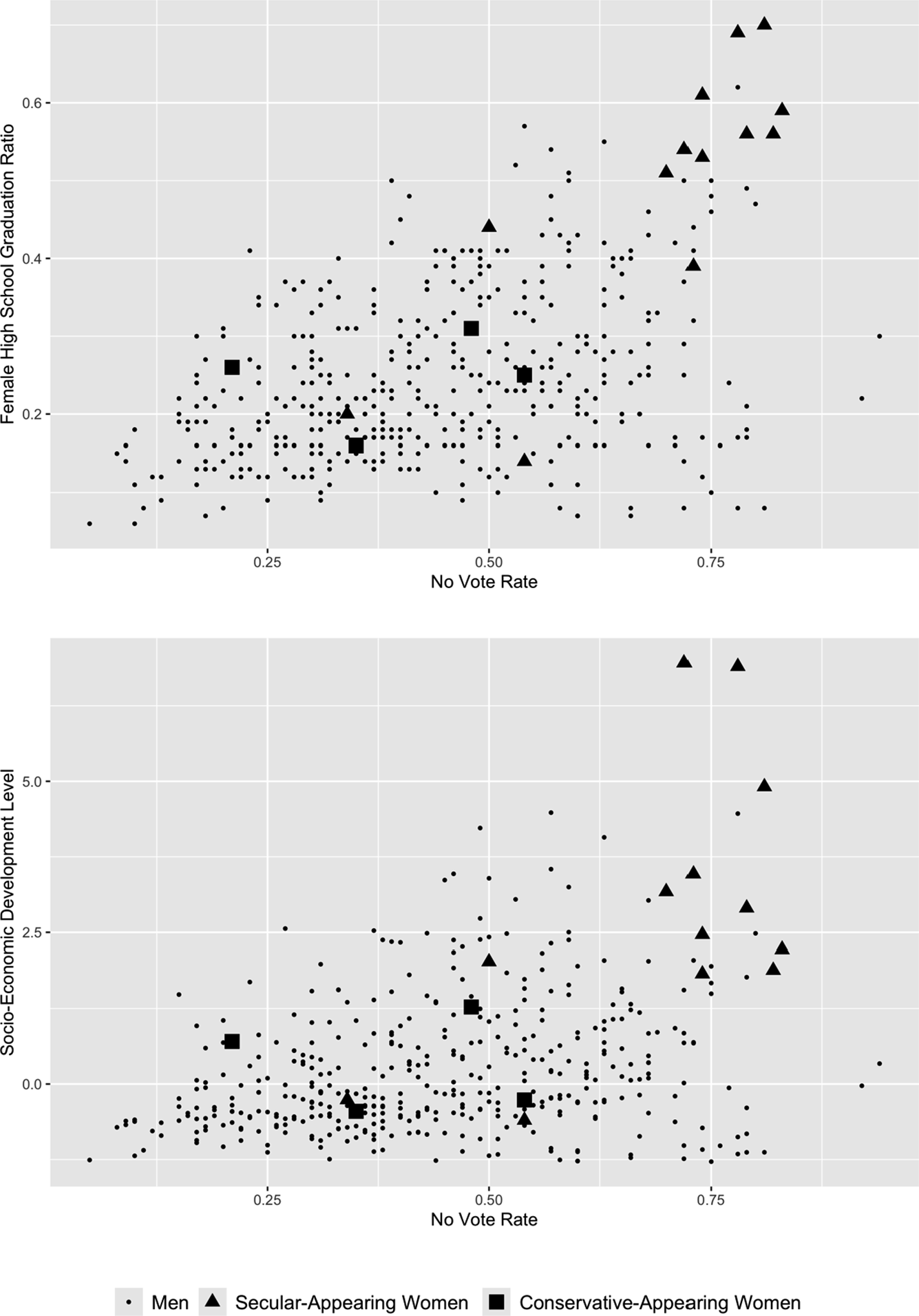

The analysis thus far suggests that the AKP strategically nominates women with secular appearances in districts where the CHP is dominant. To further refine this initial analysis, I consider several key factors at the district level. These include socioeconomic development and the ratio of female high school graduates, as higher levels of these often correlate with stronger secular values. Additionally, to assess the challenges faced by the AKP in these districts, I analyze the extent of negative partisanship directed toward the party. This approach helps elucidate how these factors shape the AKP’s choice between nominating men, veiled or nonveiled women. Two scatter plots in Figure 5 show the distribution of men, nonveiled, and veiled women across districts, segmented by socioeconomic development level, female high school graduation ratio (a proxy for secularist sentiments), and “No” vote rate in the 2017 Constitutional Referendum (a proxy for negative partisanship against these parties). The data in Figure 5 reveals a positive correlation between the number of nonveiled women nominated by the AKP and the level of socioeconomic development, female high school graduation ratio, and negative partisanship against the party. These results are consistent with H4 and suggest that the AKP strategically nominates nonveiled women in economically developed districts with relatively higher female education levels, indicating greater gender equality and secularist sentiments (Konda 2019). These districts also exhibit strong negative partisan attitudes toward the AKP, as evidenced by the 70% or more of voters who voted “No” in the 2017 referendum, a measure I use to gauge partisan dislike against the AKP. Taken together, these findings suggest that the AKP leverages the secular appearance of women candidates as a strategy in electoral races where the party faces significant challenges due to prevailing negative partisan attitudes among CHP voters. To further illuminate the motivations behind this strategy, the following section presents findings from elite interviews, focusing specifically on AKP elites. As the dominant party navigating a polarized political landscape, the AKP’s strategic considerations offer valuable insights into the dynamics of symbolic leverage, with potential implications for other parties navigating similar competition conditions.

Figure 5. Distribution of AKP candidates by category across districts.

The AKP Elites’ Motivations for Nominating Nonveiled Women in the CHP Strongholds

Despite its nationwide electoral dominance over the past two decades, the AKP has encountered significant electoral challenges in the secularist CHP strongholds (Tosun Reference Tosun2010). In these areas, concerns about potential Islamist rule and interference in secular lifestyle choices heavily influence voting behavior and contribute to affective partisan polarization, making the electoral competition challenging for the AKP. Drawing on interviews with party elites and electoral discourse of the AKP, I obtain rich and detailed insights into the candidate selection process in the AKP and elite reasonings behind the decision to nominate nonveiled women in CHP strongholds. Based on the interviewees’ accounts, I identify three key factors that influence this candidate selection strategy: signaling tolerance for secular lifestyles and assuaging fears of Islamization, attracting swing voters, and projecting commitment to democracy and gender equality. However, these motivations do not fully encapsulate the complex dynamics of the candidate selection process within the AKP. Nevertheless, they provide significant insight into why party elites choose to nominate nonveiled women as part of their electoral strategy in highly polarized elections, creating challenging competition conditions.

Candidate Selection and Placement in the AKP

The AKP employs a highly centralized and structured system for candidate selection across all electoral contests. While prospective candidates initially engage in intra-partying, the final decision lies with a commission at the party headquarter. This commission, informed by survey data and elite opinions, interviews potential candidates, assesses localized data, and presents a shortlist to President Erdoğan.Footnote 13 The President then exercises ultimate authority in finalizing candidate lists, their ranking, and district assignments. Notably, President Erdoğan reserves a personal quota for the top position on each list and mayoral seats, often nominating individuals who had not actively sought candidacy.Footnote 14 Additionally, while the party aims to nominate locals, the AKP often nominates individuals with prolonged periods of residence outside their designated districts.Footnote 15 These practices contribute to expanding the party’s pool of potential candidates. Although the availability of women candidates is important for employing symbolic leverage, the AKP’s power and influence facilitates the identification and recruitment of desired female candidates, particularly in mayoral elections where personal appeal is crucial.Footnote 16 Local women’s branches and the party’s access to women civil servants further enhance this recruitment advantage, allowing the AKP to effectively employ symbolic leverage.Footnote 17 The following sections will delve into the strategic rationale behind this approach.

Signaling Tolerance for Secular Lifestyles and Assuaging Fears of Islamization

Secularist-Islamist cleavage has been one of the main determinants of voting behavior in Turkey (Bilgin Reference Bilgin2018; Güneş-Ayata and Ayata Reference Güneş-Ayata, Ayata, Sayarı and Esmer2002). Since coming to power in 2002, the AKP has appealed to diverse social groups, including conservatives, center-right voters, and conservative Kurds. However, it faces opposition from educated, upper-middle-class, and Western-oriented secularists, leading to deep societal divisions along the affective lines of secularism and Islamism (Somer Reference Somer2022). This affective polarization, particularly the dislike against the AKP among the CHP base, manifests itself in AKP elites’ narratives about voters responses to their candidates in secular districts. Kemal, who works in Çankaya AKP Branch in Ankara, described voters in CHP strongholds as fanatic and highly partisans, voting for the CHP regardless of the opposing candidate.Footnote 18 He supported this, claiming, “Even if Atatürk [the founder of secular Turkey] were alive and ran as an AKP candidate, it wouldn’t change the electoral defeat in those places like Izmir [the most secular province of Turkey] or Çankaya [the most secular district of Turkey’s capital city, Ankara].”

Negative partisanship against the AKP appears more disadvantageous to veiled women candidates than to other groups. Seda, who was an MP of the AKP at the time of the interview, shared her experience of bias during an electoral campaign in secularist-dominated districts.Footnote 19 She emphasized nominating secular-appearing women as a necessary and rational electoral strategy to circumvent this immediate bias, as demonstrated:

“For women candidates, the party knows that if we nominate a veiled woman and send her to campaign in CHP strongholds, the voters might not accept this candidate…When some voters see this [pointing at her headscarf], oh my God, they become quite irritated. They dismiss you without even having a word. Therefore, the party prefers to nominate a woman who appears secular, even only to initiate a dialogue with constituents.”

Seda’s account clearly illustrates the CHP base’s bias against the headscarf. This bias is one of the primary reasons for strong affective partisan dislike of the AKP among CHP voters in Western districts, where relatively well-educated, wealthier, westernized, and secular people of Turkey cluster. For instance, all interviewees cited Izmir when discussing the robust electoral challenges the AKP faces due to secularist sentiments. Izmir, the most secular and third-largest city in Turkey, is considered as a secular safe haven for those threatened by the Islamist party rule. Some interviewees described this province as the AKP’s main battleground against the CHP, and thus, where the party extensively employs symbolic leverage. Indeed, the AKP fielded six female district mayoral candidates across Izmir, compared to 11 in the remaining 30 metropolitan provinces of Turkey.

Interviewees unanimously attributed the party’s electoral defeat in Izmir to apprehensions about potential interference in secular lifestyles and the perceived threat of Islamization. Cihan, from the AKP Izmir Branch, encapsulated the difficulties the party encountered in Izmir due to these issues.Footnote 20 Cihan stated that they make daily efforts to communicate their respect for diverse lifestyles and assure constituents that the party has no intention of interfering with their lifestyle choices. However, he acknowledged their failure to effectively convey this message, particularly after the Republican Rallies in 2007, which intensified secularist concerns. The Republican Rallies were a series of mass protests that began after the AKP announced its Presidential Candidate in 2007, whose wife wears a headscarf. The main driving force behind these protests was the desire to protect the secular state from what was perceived as the Islamist rule of the AKP. Protesters were motivated to prevent the government from altering secularism and transforming Turkey into an Islamist state (Aydın and Taskin Reference Aydın and Taşkin2014). This sentiment still resonates with the secularist CHP base and influences their voting behavior.

AKP elites’ efforts to address secularist concerns were evident during the 2019 local election campaign in Izmir. In his Izmir campaign speech, President Erdoğan expressed tolerance for secular lifestyles, asserting that the AKP had not meddled with people’s lifestyle choices during its 17-year tenure.Footnote 21 He contended that fears of an alcohol consumption ban and compulsory hijab were proven untrue, then gestured toward the six nonveiled women mayoral candidates on stage, stating, “My sisters are the best response to them.” Here, “them” referred to those who harbor fears of compulsory hijab and Islamic rule. These remarks indicate that signaling tolerance and addressing secularist concerns were crucial elements of the AKP’s campaign strategy in Izmir.

Similar themes appeared in television interviews with the AKP’s women mayoral candidates in Izmir. Melek Eroğlu, an AKP woman mayoral candidate in Izmir, revealed during a TV interview that her constituents worry about their secular lifestyles.Footnote 22 She assured the audience that the party does not dictate how people should live. Eroglu supported her claim by stating, “I am a member of the AKP, I reside in Izmir, and I am the most prominent example of the party’s stance on lifestyles,” using her secular appearance as proof of the party’s tolerance toward secularism. Some candidates also discussed the controversy surrounding the headscarf issue and its impact on voters’ electoral decisions. Another AKP woman mayoral nominee in Kadıköy — one of the CHP strongholds in Istanbul — Özgül Özkan Yavuz, claimed during a TV interview that voters questioned her if the party would compel them to veil if it won the elections.Footnote 23 Dismissing these concerns as “unfounded,” she accused the CHP of spreading such fears. These accounts indicate strong direct evidence that the AKP tactically selected women candidates who appear secular. This strategy seems to be a deliberate attempt to demonstrate a tolerance for secular lifestyles and alleviate concerns about Islamization and compulsory hijab.

Attracting Swing Voters

Attracting swing voters emerges as another strategic objective of the party’s nomination of nonveiled women in the CHP strongholds. Interview accounts emphasized that the FPTP electoral system, known for fostering personal vote-earning attributes, underscores a candidate’s identity in achieving electoral success in mayoral elections. Interviewees unanimously agreed that in these elections, the electorate tends to favor the candidate over the party. Therefore, party elites are attuned to these electoral system-induced incentives. Fatma, an AKP MP, underscored the propensity for local elections to attract a higher number of swing voters.Footnote 24 These voters, despite their ideological allegiance to a specific party, may vote for an opposing party if they find the candidate appealing, even if it is an isolated instance. Fatma elaborated, “This occurs even if the parties are markedly ideologically distinct, as in the case of the CHP and the AKP, because voters may say, ‘This is our guy, this is our gal.’” She added that she had personally witnessed such instances, particularly between the AKP and the CHP, further explaining that these situations, which tend to occur at local levels, prompt them to reflect the sociological characteristics of districts in their candidate nominations.

As Fatma’s account indicates, district demographics play a key role in this strategy. The party strategically selects candidates capable of appealing to swing voters in specific districts, often choosing candidates whose identity resonates with the local demographics, particularly minority groups or women who may prioritize identity over party loyalty. Seda explained that the party conducts workshops to identify appealing aspirants from diverse identity groups for strategic placement in districts where these groups are concentrated.Footnote 25 Candidates are expected to reflect the prevailing sociopolitical landscape and sentiments of the majority within their respective districts.

Moreover, interviewees highlighted the importance of candidate-district compatibility in the personalized context of mayoral elections. Mehmet, an AKP district mayor in Trabzon, described how voters assess this compatibility, explaining that voters seek candidates who share their values, believing such candidates are more trustworthy.Footnote 26 Similarly, Kemal explained that the primary goal in secular districts is selecting candidates who resonate with the local population, citing Çankaya, a secular district, as an example where their relatively successful candidate was a woman known for her secular lifestyle.Footnote 27 These statements indicate that the decision to nominate nonveiled women is influenced by whether a district is secular or conservative. In secular districts, the strategic importance of nonveiled women increases as they can potentially attract swing voters.

Projecting Commitment to Democracy and Gender Equality

Another motivation of AKP elites to deploy nonveiled female candidates is to project a commitment to democratic principles and gender equality, a strategy rendered particularly salient by Turkey’s recent democratic backlash under their governance. This practice aligns with scholarly findings demonstrating that authoritarian regimes augment female representation to mitigate legitimacy deficit from democratic backsliding (Bjarnegård and Zetterberg Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2022). In the Turkish context, this phenomenon manifests at the subnational level. AKP elites simulate commitment to democracy by nominating secular-appearing, nonveiled women in CHP strongholds, whose very image is historically linked to democratic ideals through the imagery of modern Turkey’s founders. This image strongly resonates with secular CHP voters, who are concerned about authoritarianism, and thus provides strategic advantages for AKP elites.

Interviewees confirmed the party’s intent to signal commitment to democratic principles and gender equality by nominating secular-appearing women. Since voters rely on visual cues to infer party stances on contentious issues, AKP elites strategically leverage the stereotypes associated with nonveiled women to appeal to those concerned with democratic backlash, as illustrated by this quote:

“The party could have run with an educated secular man who received a PhD degree from METU [one of the most progressive universities in Turkey], but this candidate would have needed to explain himself to voters. But, when the party runs with a secular woman, voters automatically see this woman as well-educated and democratic.”Footnote 28

AKP female candidates in CHP strongholds strategically positioned their nominations as symbols of the party’s dedication to democratic principles and gender equality. For instance, Ayda Mac, a candidate in a populous Izmir district, identified herself as a “Republic’s woman” during a televised interview, underscoring the significance of the Republic, democracy, and Atatürk’s principles.Footnote 29 Mac further invoked Atatürk’s legacy of women’s empowerment and highlighted the AKP’s increased female representation in Izmir as tangible evidence of their commitment to democratic and gender-inclusive governance, as demonstrated below:

“If one is to speak of the Republic, democracy, and Atatürk’s principles, then these should be manifested through one’s actions. Atatürk placed great importance on women and initiated his revolutions on this premise, consistently taking measures to empower women. Erdoğan also exemplifies this through his actions. The fact that six of the mayoral candidates in Izmir are women underscores the importance attributed to women by the AKP. Therefore, voters who harbor concerns about a democratic backlash and the principles of Atatürk should support the AKP.”

Expanding on this theme, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of the Republic of Turkey and a pivotal symbol of secularism (Hart Reference Hart1999), became a focal point for women CHP supporters, who, in response to rising Islamism since the 1990s, began identifying as “Atatürk’s woman” or “Republic’s woman” to express appreciation for his reforms. During the 2019 mayoral elections, AKP’s nonveiled female candidates also adopted these terms, with media interviews revealing five out of 13 secular candidates doing so. Candidate Evrim Özen challenged the notion that Atatürkism is exclusive to CHP supporters. She pointed out that voters often assert, “We are Atatürkist, we do not vote [for the AKP],” and argued that this was misleading, highlighting her own admiration for Atatürk.Footnote 30

Additionally, AKP elites aim to boost their electoral appeal among voters who prioritize gender equality. Recognizing the cross-partisan salience of gender issues, these elites strategically seek to attract voters, including those typically aligned with the CHP, who favor female candidates. This strategy is substantiated by the party’s data-driven candidate selection process. Interviewees revealed that the AKP’s Research and Development Office conducts regular public opinion polls to evaluate candidate profiles and gauge voter sentiment, data heavily influencing candidate selection decisions. For instance, Cihan, from the AKP Izmir Branch election office, disclosed that party data indicated a discernible voter demand for female candidates in specific districts, a finding subsequently operationalized in the nomination process.Footnote 31

Campaign speeches further illustrate this data-driven approach. Amber Türkmen, the AKP’s 2019 mayoral candidate in Çankaya, stated in her campaign speeches that she had “heard the cries for a female candidate” from the Çankaya electorate even before her candidacy was announced.Footnote 32 She noted that this demand was not party-specific, but a common call from all voters. Türkmen acknowledged President Erdoğan for responding to this demand, implying his attentiveness to public sentiment.

The preceding evidence gleaned from interviewee accounts, campaign speeches, and media interviews of the candidates indicates that AKP elites’ strategic nomination of nonveiled women is primarily aimed at signaling tolerance for secular lifestyles, assuaging fears of Islamization, appealing to swing voters, and projecting a commitment to democracy and gender equality. However, the efficacy of this strategy warrants careful examination. Although the AKP was unable to secure any mayoral seats in these contests, party elites collectively interpreted the outcomes favorably. Even amidst the loss of key metropolitan municipalities and a general decline in the AKP’s vote share, the party frequently observed either a marginal increase or a stabilization of its vote share in districts where these candidates were fielded.Footnote 33 Despite the absence of immediate electoral gains in mayoral positions, party elites regard this strategy positively, as it aligns with a long-term goal of diminishing the CHP’s support base and cultivating support within these districts. However, a comprehensive evaluation of this strategy’s influence on vote share necessitates further research.

An additional area of inquiry pertains to the motivations of women accepting less-winnable candidacies. Despite the potential setback of electoral defeat, it is crucial to investigate what prompts these women to accept such nominations and whether unsuccessful female mayoral nominees nevertheless derive benefits from their candidacies under the AKP label. Party elites underscored that these women are consistently integrated into the party structure following their candidacies, rather than being sidelined. Interviewees emphasized that these women often possessed preexisting connections with the party prior to their nominations and were subsequently offered positions within party headquarters or at various organizational levels. This assertion is supported by the post-election appointments of some women candidates to prominent bureaucratic positions, while others assumed advisory or administrative roles within local party offices.Footnote 34 Thus, despite the perceived risk of these nominations, they represent a rational strategic choice for the women nominees. These nominations constitute a mutually beneficial exchange: elites gain electoral advantages through symbolic capital, while women nominees, despite the improbability of electoral victory, achieve significant career advancement. This rational calculus employed by women undermines the notion that they are mere placeholders in unwinnable seats, emphasizing their agency as strategic actors.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study explores party elites’ incentives to employ symbolic leverage, nominating (non)veiled women as an electoral strategy in rival party strongholds where partisan polarization is high and women’s identities are central to symbolic contestation. The findings reveal that in Turkey’s polarized political landscape, parties strategically use the symbolism of women’s (non)veiling to gain electoral advantage. Overall, right-wing, Islamist, and secularist parties tailor their candidate selection and utilize women’s image to appeal to specific voter groups. The Islamist AKP strategically fields nonveiled women in secular areas to project a moderate image, while the secularist CHP actively increases the presence of veiled women in conservative districts and party organization to appeal to religious voters. Furthermore, factors associated with secularist sentiments, such as increased socioeconomic development, female education, and negative partisanship against the Islamist ruling party, positively correlate with nominating women candidates who visually represent a secular image. Moreover, these quantitative results are further supported and enriched by the analysis of in-depth interviews with AKP elites and their electoral discourse, as they offer a detailed and rich account of the motivations behind this strategy.

Collectively, the interviewees corroborate that AKP elites tend to nominate nonveiled women in districts marked by strong secularist sentiments and high negative partisanship toward the party. They attribute this strategy to the challenging competitive conditions stemming from concerns about potential interference in secular lifestyles, fear of potential mandatory hijab imposition, and overall Islamization under AKP governance. Thus, by nominating nonveiled women, the AKP aims to connect with secular voters, projecting an image of tolerance toward secularism. The interviewees further elucidate that this strategy primarily targets swing voters. These voters, dissatisfied with the secularist party’s candidate, might contemplate voting for an AKP candidate perceived as “one of their own.” Additionally, by selecting secular-appearing women, the AKP intends to appeal to voters concerned with the recent democratic backlash, as nonveiled women are stereotypically associated with democracy due to the symbolic imagery employed by the founders of modern Turkey. An additional motivation for the AKP elites in nominating these women is to appeal to voters who prioritize gender equality, thereby mobilizing voters more inclined to support a female candidate, regardless of party affiliation. The analysis of the AKP elites’ electoral discourse reinforces these findings, demonstrating that party elites consider the nomination of nonveiled women candidates a strategically astute decision.

This study contributes significantly to the existing body of research on women’s representation. It introduces a novel theoretical framework, symbolic leverage, to understand how party leaders in the highly polarized political environment of Muslim-majority Turkey utilize women’s (non)veiling status for electoral advantage. This research moves beyond observations of similar patterns in Western nations with Muslim minorities, identifying affective polarization and political symbols as intertwined central mechanisms that shape the inclusion of women in politics and how that inclusion is strategically employed within broader electoral competition strategies. The findings indicate that affective polarization, centered on culturally significant issues symbolized by women’s identities, incentivizes party elites to strategically nominate women who embody these identities, aiming to appeal to electorates who place a higher salience on these issues. This strategy involves tailoring the party’s image and message to resonate with a specific constituency, thereby maximizing the likelihood of garnering votes. Furthermore, the findings reveal that elite strategic behavior regarding women’s representation requires a contextual analysis of symbolic politics intertwined with women’s intersecting identities, as the symbols associated with those identities differ across cultural contexts. This study also demonstrated that women with intersecting identities are not randomly assigned to unwinnable seats but are deliberately selected to contest in challenging districts because their identities offer elites strategic benefits, enabling them to send powerful signals to voters of the rival party in highly polarized elections. The empirical evidence offers new insights into how these mechanisms work in practice, considering other district-level factors and providing a nuanced understanding of elites’ motivations for including women under specific electoral competition conditions where leveraging (non)veiling status is a salient strategy.

These findings also open pathways to further research. This article presents a single case study that examines elite behavior toward the political inclusion of women within a specific political context of Turkey. Future studies could potentially validate these findings in other contexts where the apparent ethnic, racial, and religious identities of women, and the political symbols attached to their identities, are strategically leveraged by party elites in polarized electoral competition. While this study focuses on how this strategy has been implemented at the local level, future research could extend this approach to examine national elections under varying electoral systems, social cleavages, and partisan polarization conditions. In conclusion, this study enhances our understanding of strategic elite behavior toward the inclusion of women in politics with implications in both democratic and authoritarian contexts. It pioneers new paths within the existing literature by illustrating the tactics employed by elites to leverage women’s identities as political symbols, thereby enhancing their electoral prospects under challenging conditions.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X25000200

Acknowledgments

I thank Lindsay Benstead, Jill S. Greenlee, Meral Ugur Cinar, Esra Issever-Ekinci, Lucie Drechselová, Orçun Selçuk, Ozlem Tuncel, Boğaç Erozan, and the anonymous reviewers and editorial team of Politics & Gender for their valuable feedback on earlier drafts of this article. I also thank the chairs, discussants, and attendees of the following conferences and workshops for their helpful feedback: American Political Science Association Annual Meeting, Montreal, Canada, September 5–8, 2022; WPSA Annual Conference, San Francisco, April 6–8, 2023; MPSA Annual Conference, Chicago, April 4–7, 2024, PSA Turkish Politics Online Workshop, October 21, 2024.

Financial Support

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article. Entire manuscript was prepared by single author. This article is based on research originally conducted for the author’s dissertation titled “Do Men Strategically Leverage Women’s Intersecting Identities? Intersectional Symbolic Inclusion as an Electoral Competition Strategy in Polarized Turkey.” The dissertation was submitted to Portland State University in 2023 and is published in ProQuest. It is accessible through the provided link. The dissertation is cited in the revised manuscript.Footnote 35

Competing interests

None.