1 Introduction

How do women experience war? Two distinct threads of scholarship have developed exploring this question. First – women’s standing in society and the occurrence of violence are related. Early feminist IR scholars like Enloe (Reference Enloe1990, Reference Enloe1993) and Tickner et al. (Reference Tickner1992) theorized the nature of this relationship and more quantitative scholars have provided empirical evidence. Melander (Reference Melander, Mason and Mitchell2016, p. 197) suggested that “the strongest pattern in civil war is probably the gendered nature,” and Bakken and Buhaug (Reference Bakken and Buhaug2021, p. 984) highlights the “near consensus finding that gender inequality is associated with increased risk of civil war.”

Secondly, the consequences of war are also gendered. Civil conflict has significant, negative effects on maternal health (e.g., Kotsadam & Østby, Reference Kotsadam and Østby2019; Kottegoda, Samuel, & Emmanuel, Reference Kottegoda, Samuel and Emmanuel2008; Tamura et al., Reference Tamura, Hinderaker, Manzi, Van Den Bergh and Zachariah2012; Urdal & Che, Reference Urdal and Che2013).Footnote 1 Going a step further, public health scholars have explored the role that women’s autonomy or empowerment plays in conflict outcomes related to maternal and infant health (e.g., Adjiwanou & LeGrand, Reference Adjiwanou and LeGrand2014; Banda et al., Reference Banda, Odimegwu, Ntoimo and Muchiri2017; Bloom, Wypij, & Gupta, Reference Bloom, Wypij and Gupta2001; Stephenson, Bartel, & Rubardt, Reference Stephenson, Bartel and Rubardt2012).

Far less attention has been paid to the interrelationship between these two processes. If gender affects both the occurrence of violence and the consequences of that violence, then it is essential for them to be considered together. Skeptics of gender equality as an important determinant of war and peace have expressed concern about endogeneity but rather than exploring the meaning of this inter-relationship, they have dismissed it. Our approach is different – as we put the connection front and center, both theoretically and methodologically. We place the focus on how gender inequality greatly increases the likelihood that states will experience armed conflict and the fact that women will suffer greater consequences in those conflicts that do occur. This is more an issue of sample selection rather than endogeneity. Women in Finland are less likely to experience harsh health conflict consequences. The comparatively small gender gap there makes it less likely that they will experience a war and make it more likely that women will receive excellent care should a conflict occur.

Gender is the most basic hierarchy in the human experience. Failure to recognize it as a power structure has implications for politics and, of course, our understanding of politics. Peterson (Reference Peterson1992, p. 197) notes that we cannot fully understand real-world events based on solely on male-focused accounts that “render women and gender invisible.” Moreover, as Sjoberg (Reference Sjoberg2010) notes, representing the state as non-gendered does not make it so. Decisions about when to use force and as well as the decisions about how to invest in public good goods (for example, how much money should we allocate toward women’s health programs) are a reflection of the gender attitudes and hierarchies in society.

In this Element, we discuss the research on the gender and war. Scholars have demonstrated that in societies where gender inequality is greater, armed conflict is more likely to occur (Caprioli, Reference Caprioli2000, Reference Caprioli2003). Once conflict has begun, women have a different, more indirect experience of armed conflict. After drawing this conclusion, we take the analysis an important step further. Where women’s equality is low, conflict is more likely and women experience more negative consequences. If gender inequality affects both the causes and the consequences of war, then we need to consider the inherent connection between the two processes. If causes and consequences are clearly linked to each other as well as to gender political inequality, then efforts to prevent conflict as well as the humanitarian response to the consequences of war need to take gender into account.

Feminist View of Security

As a foundation of feminist security, it important to recognize that the word gender does not mean the biological differences between men and women because gender is culturally defined. Gender is a social construction and that social construction is one that denotes inequalities based on perceived differences between men and women (Scott, Reference Scott1986; Tickner et al., Reference Tickner1992). All over the world, men are privileged and in a position of dominion over women (Tickner et al., Reference Tickner1992). Our understandings of gender create hierarchies based on perceptions of masculine and feminine characteristics (Sjoberg, Reference Sjoberg2010).

To fully understand the gendered causes and consequences of war, a feminist security lens is essential. Both the prosecution and study of armed conflict continue to be dominated by men (Sjoberg, Reference Sjoberg2010). Without a gendered lens, we miss the critical insights found in the feminist security literature. From this perspective, war is part of continuum of the violence experienced in everyday life rather than a separate and distinct event (Sjoberg, Reference Sjoberg2013). When militarized masculinity is widespread in society, any conflict is more likely to be met with violence (Enloe, Reference Enloe1993).

Using gender as a lens allows us to focus on power dynamics within a society. Taking the idea of gender hierarchy into consideration when we think about the causes and consequences of armed conflict, we must consider what Sjoberg (Reference Sjoberg2013) terms “relative vulnerabilities.” In unequal societies where violence is already viewed as more acceptable, when conflict inevitably begins women are more vulnerable to its impacts because of their preexisting subordinate position in society. From this perspective, conflict encompasses violence in the household, and in society, as well as between states or rebel groups and governments. Violence has economic, social, and political consequences that are gendered because these consequences are filtered through the institutions and structures of society. A gendered approach enables scholars to focus on women’s experiences and the ways in which those experiences reflect an unequal social position.

Gendered Causes of War

Mainstream scholarship on the causes of civil conflict has often highlighted greed and grievance (Collier & Hoeffler, Reference Collier and Hoeffler2004). Rebels are either victims fighting against religious or ethnic oppression, or they are brigands looking to seize loot like natural resources or other sources of wealth. While the greed versus grievance dichotomy is an oversimplification (Berdal, Reference Berdal2005), much of the popular discourse about civil wars focuses on these two explanations.

Traditional research on the causes of war fails to acknowledge that gender influences the occurrence of violence. Recent work on gender-blind approaches in political science (Forman-Rabinovici & Mandel, Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Mandel2022; Paxton, Reference Paxton2000) demonstrates how not taking gender into account creates gaps in our understanding of political phenomena. For our purposes we wish to highlight the fact violence is a highly gendered practice.

Men and women play different roles in conflict. Who fights in wars is gendered as is how individuals are affected by the fighting (Bjarnegård et al., Reference Bjarnegård, Melander and Bardall2015). According to Goldstein (Reference Goldstein2001), less than 1% of warriors throughout history have been women, but biology alone cannot explain this imbalance. Under some circumstances, women perpetrate violence and can be highly effective fighters (Darden, Henshaw, & Szekely, Reference Darden, Henshaw and Szekely2019; Sjoberg & Gentry, Reference Sjoberg and Gentry2011; Thomas & Bond, Reference Thomas and Bond2015; Wood & Thomas, Reference Wood and Thomas2017). The predominance of men in war is rooted in societal constructions and traditional gender norms that dictate that men defend the homeland and women maintain the home front. If anything, these gender role norms tend to be strengthen during wartime (Sjoberg, Reference Sjoberg2013).

Feminist scholars point out that gender is an essential aspect of violence in all societies because gender inequality exists in all societies (Caprioli, Reference Caprioli2005). There are two primary explanations for why gender inequality might cause conflict. First is the essentialist argument – women are more peaceful by their natures. From this point of view, there are inherent differences in the attitudes of biological men and women (Goldstein, Reference Goldstein2001; Melander, Reference Melander2005). Given their preference for peaceful means of conflict resolution and their role as mothers, women are believed to be more averse to violence. In societies where political equality is greater, these peaceful tendencies of women have more influence on foreign policy decision-making. This preference for nonviolence may be born of upbringing or genetics (Bjarnegård & Melander, Reference Bjarnegård and Melander2011; Melander, Reference Melander, Mason and Mitchell2016).

In order to lessen violence in a society (or the international system or a household), the essentialist prescription would be to empower women. Women are less likely to use violence in daily interactions (Dahlum & Wig, Reference Dahlum and Wig2020). Many studies of individual attitudes demonstrate that women prefer nonviolent methods of conflict resolution. When women are elected to public office, they can turn those preferences into policies that put fewer resources toward the military or increasing attention on social ills relating to underlying grievances that could turn violent (Melander, Reference Melander2005).

This essentialist logic does not go unchallenged, however. By suggesting that all women, by their nature, prefer nonviolent methods of conflict resolution or are less likely to use force, many see this as reinforcing gender stereotypes (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge2005). Women vary in their political preferences as do men, and thus attributing gender as a cause of war seems at best incomplete.

The second explanation is more of a constructivist argument – meaning socially constructed norms about gender and gender roles influence how a society responds to conflict. Ideas about what is feminine and what is masculine affect attitudes toward violence. Men are expected to be warriors while women are caregivers, and in many cases, their upbringings reflect these differences (Melander, Reference Melander2005). Men and boys are taught to be tough while women and girls are taught to be nurturing. Such stereotypes also highlight women’s subordinate position in the societal hierarchy (Goldstein, Reference Goldstein2001; Tickner et al., Reference Tickner1992). Boys who do not act tough and warlike are accused of being weak or girly, which is perceived as less than being manly and lessens social status.

Not only do traditional gender roles cement societal hierarchy, but they also legitimize violence as a man must do whatever it takes to defend the home and the honor of the women under his care. When men and women are more equal, violent and intolerant (masculine) methods of dealing with conflict are less dominant. From a constructivist point of view, the prescription for lessening violence would be to change the minds and perceptions of both men and women and thus shift societal norms.

These two explanations do not run counter to each other, and both may help us to understand the relationship between gender inequality and conflict (Caprioli, Reference Caprioli2000, Reference Caprioli2005; Goldstein, Reference Goldstein2001; Melander, Reference Melander2005; Tickner, Reference Tickner1997; Tickner et al., Reference Tickner1992). Both evolution and socio-economic conditions help us to understand why women tend to value peaceful solutions more than men (Melander, Reference Melander, Mason and Mitchell2016). In egalitarian societies where women’s preferences for interdependence and egalitarianism over pure competition are taken seriously (Welch & Hibbing, Reference Welch and Hibbing1992), resources and health care are more likely to be available to all. Societies’ constructed ideas about gender and gender roles also influence decision-making over how resources are allocated. Women’s political empowerment and representation influences well-being outcomes for women and children, as well as for society as a whole (Bhalotra & Clots-Figueras, Reference Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras2014). Without gender equality, national political cultures will be characterized by norms of violence. Those norms will, in turn, influence foreign policy and the way that the government responds to internal challenges. When inequality is high, the likelihood of violence will be too.

What Kind of Inequality?

Gender inequality exists everywhere, reflecting the gender hierarchies that exist in all societies (Webster, Chen, and Beardsley, Reference Webster, Chen and Beardsley2019). Rich and poor countries, democracies as well as autocracies are all similar in this regard. What is less obvious is the fact that gender inequality can be a matter of life and death. Inequality has been linked to violence, ranging from domestic violence to war – both international wars (Caprioli, Reference Caprioli2000, Reference Caprioli2003; Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Caprioli, Ballif-Spanvill, McDermott and Emmett2009; Regan & Paskeviciute, Reference Regan and Paskeviciute2003) and civil wars (Caprioli, Reference Caprioli2005; Melander, Reference Melander2005). Focusing on the causes of conflict, where gender inequality is high, tolerance for violence will be high, enhancing the ability of violent groups to mobilize support. How inequality has been conceptualized and measured, however, has varied.

Gender inequality can take several forms – economic, social, and political. Economic gender inequality includes unequal labor force participation and the existence of systematic pay gaps between men and women. The exclusion of women from financial decision-making in the household and unequal laws regarding property ownership and inheritance are additional examples. Social gender inequality make take the form of unequal access to education, forced marriages (often at young ages), lack of access to family planning services, and the absence of the right to divorce.

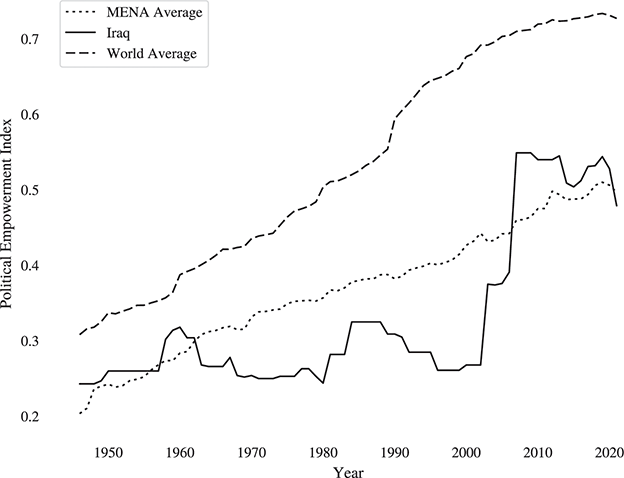

In this Element, we focus on political inequality. When women lack the right to vote or are under represented in government or lack standing in the judicial system, this is gendered political inequality. According to the World Economic Forum, political empowerment (or the degree to which women have influence in political and social spaces) is where the greatest gap exists worldwide between men and women, compared to educational attainment, economic opportunity, and health & survival (Zahidi, Reference Zahidi2023). In their 2023 Global Gender Gap report, they posit that it will take 162 years for women to obtain political parity with men if the current rate of progress continues (Zahidi, Reference Zahidi2023).

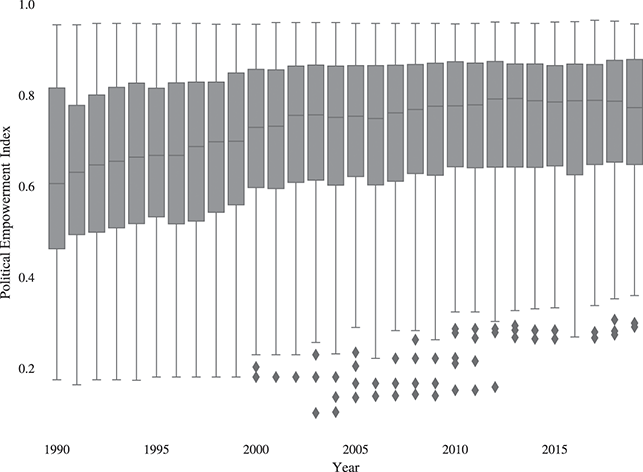

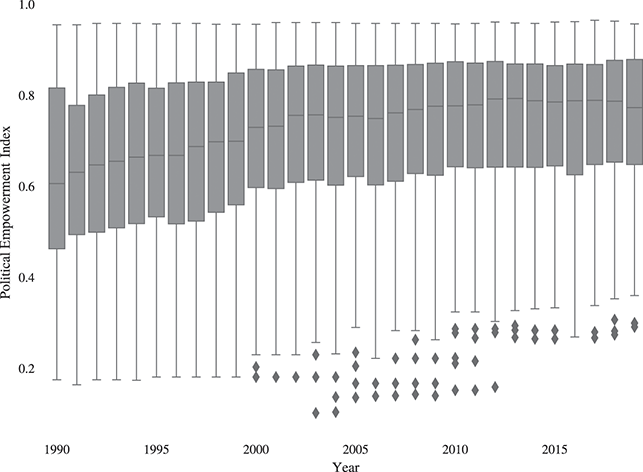

Figure 1 plots the Political Empowerment Index (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2023b; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt and Tzelgov2023) in 146 countries between 1990 and 2019. Political empowerment is defined as “a process of increasing capacity for women, leading to greater choice, agency, and participation in societal decision-making” (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2023a, p. 302).Footnote 2

Figure 1 Political Empowerment Index, 1990–2019

Figure 1 reveals several important patterns in women’s political equality over time. First, the yearly median of the Political Empowerment Index has increased steadily over time, indicating that global empowerment has improved. Yet, the figure also reveals significant variation in the level of women’s political empowerment. While equality maybe increasing globally, there remain a significant number of countries in which women maintain very limited political power. Thus, while the general record of women’s political inequality has improved, we do see wide variation globally as well.

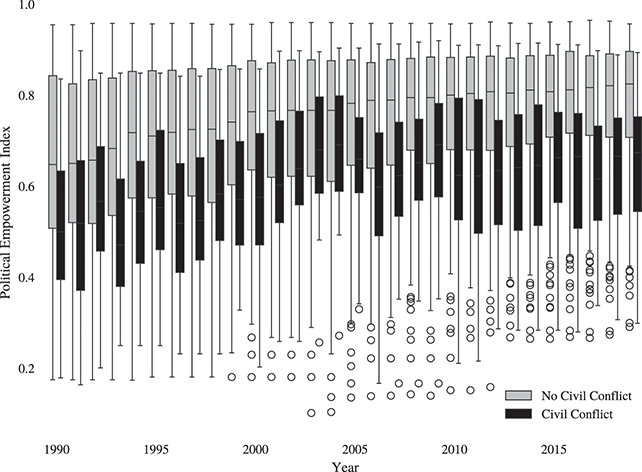

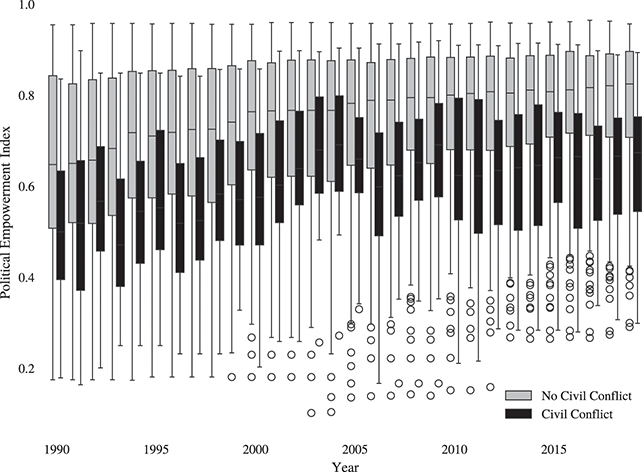

Because we are interested in the relationship between conflict and women’s political empowerment, we next turn to see whether there’s variation among those countries experiencing civil conflict. The conflict variable indicates whether an intrastate conflict occurred in the country in a given year (Davies, Pettersson, & Öberg, Reference Davies, Pettersson and Öberg2022; Gleditsch et al., Reference Gleditsch, Wallensteen, Eriksson, Sollenberg and Strand2002). Figure 2 plots the Political Empowerment Index over time for countries with a civil conflict and those without. While, on average, women’s political equality is lower in conflict countries, we still see significant variation in the level of inequality in conflict cases.

Figure 2 Political Empowerment Index by Conflict, 1990–2019

Previous studies have found that states with higher levels of political inequality are more likely to engage in both interstate (Caprioli, Reference Caprioli2000, Reference Caprioli2003; Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Caprioli, Ballif-Spanvill, McDermott and Emmett2009; Regan & Paskeviciute, Reference Regan and Paskeviciute2003) and intrastate wars (Caprioli, Reference Caprioli2005; Melander, Reference Melander2005). Focusing on civil war, these states also experience greater rates of conflict recurrence (Demeritt, Nichols, & Kelly, Reference Demeritt, Nichols and Kelly2014). In international conflicts, less equal states are more likely to escalate to violence (Caprioli & Boyer, Reference Caprioli and Boyer2001).

States with higher levels of women’s political empowerment are less likely to employ violence than those with lower levels of gender equality at home. Violence toward women is a better predictor of a state’s likelihood of participating in conflict than democracy, wealth, or prevalence of Islam (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Caprioli, Ballif-Spanvill, McDermott and Emmett2009).

Given the empirical pattern shown in Figure 2 as well as the previous scholarship linking political inequality to violence, we believe that understanding how women’s political inequality impacts health outcomes during times of conflict requires taking into account the fact that conflict is more likely in those countries with weak gender equality. The ways that women experience conflict are in part explained by the conditions in their home countries prior to the beginning of the conflict.

Gendered Consequences of War

Not only are the causes of conflict gendered, but the consequences of war are gendered as well. Less research has been done on this side of the coin, but as was the case with the research on gender and conflict onset, the work on gender and consequences has been done in isolation. The connection between the two has been under appreciated.

The mechanisms linking gender and the consequences of war are less clear. Scholars have identified a range of ways that conflict may affect women differently than men (discussed in detail in this Element), but there has been less consideration of how inequality – particularly political inequality – influences the degree of those impacts. Where women are already in a subordinate position in society, the effects of war will come down harder upon them.

The economic, health, and social consequences that occur beyond the battlefield are felt first by women and children (Sjoberg, Reference Sjoberg2012) and are not gender-neutral (Minoiu & Shemyakina, Reference Minoiu and Shemyakina2012). Women’s well-being may be affected by three different mechanisms according to the conflict literature: the economic damage effect, the displacement effect, and the sexual violence effect. All three of these can be understood with greater clarity when we combine them with gender inequality.

Gendered Health Outcomes

Economic Effects

In the countries where wars are fought, productive members of society are killed, infrastructure is damaged or destroyed, and long-term damage is done to the economic, educational, and public health systems (Allen & Lektzian, Reference Allen and Lektzian2013; Ghobarah, Huth, & Russett, Reference Ghobarah, Huth and Russett2004; Iqbal, Reference Iqbal2006; Lai & Thyne, Reference Lai and Thyne2007). Critically, resources are diverted way from public programs that help women and children. This shift will be more dramatic in societies where women’s representation is limited and masculine values prioritizing violence are reflected in policy choices.

The diminished quality of social programs in gender unequal societies will be magnified as the destruction associated with war degrades economies and economic potential going forward. These indirect costs can negatively impact a country’s standard of health for many years following the termination of fighting. When the electrical grid is damaged, water purification and safety will deteriorate. Without clean water, healthy food, proper health care, or access to care, the health and well-being of women can quickly degrade. This is especially problematic in societies that failed to invest in women’s health prior to the war.

Infrastructure is often targeted by combatants. By blowing up bridges and roads, combatants may hinder the movements of their adversaries, which has strategic benefits. Without roads and bridges, however, economic exchange is also hindered. Bringing goods to market becomes much more difficult. Hospitals may be blown up, and the roads and bridges needed to get to those hospitals destroyed. Fighting can decimate crops and agricultural land, compromising the food supply. In times of food scarcity, women and girls may be discriminated against in the distribution of food and medicine.

As fighting continues, resources that are needed to fund armed conflict are drawn disproportionately from public goods programs like health services, education, and policing many of which are highly beneficial to women. This is true for all societies, but where investment in public goods was lagging prior to the fighting, the impact will be greater. During civil war, states divert resources from productive sectors to violence, which causes society to lose twice over (Collier et al., Reference Collier, Elliott and Hegre2003). Societies that fear attacks or violence typically prioritize security and de-prioritize policies that benefit women and their welfare (Tir & Bailey, Reference Tir and Bailey2017).

Where war spending is high in relation to state resources, the indirect social costs can become very large (Stewart & Fitzgerald Reference Stewart and Fitzgerald2000). Civil wars reduce the productivity of the entire economy, damaging and disrupting the administrative and economic resources necessary to maintain previous levels of health expenditure (Ghobarah, Huth, and Russett, Reference Ghobarah, Huth and Russett2003, Reference Ghobarah, Huth and Russett2004). Diminished and diverted resources from public program negatively influence health outcomes over time.

When the shooting stops and combatants return home, these indirect effects of conflict often remain. Damage to croplands leads to food shortages, wrecked infrastructure curtails the transportation of goods and labor, a degraded health sector cannot tend to all the needs of the population – the list could go on. Underdevelopment is a frequent consequence of war. Resources are seldom immediately restored to their previous levels causing civilians to continue to suffer negative consequences during and after the fighting (Collier et al., Reference Collier, Elliott and Hegre2003). Economic growth may be slowed, making it difficult to return to status quo public spending (Rehn & Sirleaf, Reference Rehn and Sirleaf2002), particularly because governmental institutions are also weakened by conflict. Not only has money been allocated away from social programs during the conflict, even after the war ends it is clear that civil wars disrupt the state’s ability to provide basic social services (Lai & Thyne, Reference Lai and Thyne2007).

The economic effects of conflict are also often indirect as resources needed to fund armed conflicts are drawn disproportionately from public goods programs like health services, education, and policing many of which are highly beneficial to women. These women face increased challenges of survival as clean water, food, fuel, electricity, and medicine are likely to be scarce (Ashford, Reference Ashford, Levy and Sidel2008). In societies where women lack political rights and voice, these challenges are magnified. When women are in political leadership, they have the ability to advocate for funding for programs that benefit women and children. When they are absent, their priorities may fail to be considered. For example, child and maternal health initiatives may not be a legislative priority in a time of economic scarcity if there are no women to champion these programs.

Below the societal level, the costs of war can also be understood at the individual level. Women may be called upon to take on new roles in the household as men are called away to fight, required not only to provide domestic labor for the household but also to seek employment outside of the house in order to make ends meet. Women may also prioritize the health of their children under these circumstances, providing scarce medicine and food to young people rather than themselves.

Many women struggle with poverty (or deeper poverty) during war as husbands and sons who have been traditional breadwinners leave to fight. These women face increased challenges as clean water, food, fuel, electricity, and medicine are likely to be scarce (Ashford, Reference Ashford, Levy and Sidel2008). Add to that diminished income, and women in many situations struggle to meet the basic survival needs of their families and themselves. In societies where women lack political rights or legal protections for basic rights like property ownership, this loss of income can be devastating. Poverty plays a tremendous role in shaping the lives that women lead and the rights and freedoms that they enjoy. Armed conflict increases poverty and worsens conditions behind the front lines.

Another way that gender inequality can affect the degree to which these indirect economic consequences has to do with the laws governing property rights. Engels (Reference Engels2010) acknowledges that women’s subordinate position in society was driven in part by women’s economic reliance on men as male-owned private property increased in the nineteenth century. Even today women lag behind in their rights to control property and to inherit. While the income associated with property is important, the issue is deeper.

Laws guaranteeing women’s property rights consistently lag behind respect for men’s property rights (World Bank, 2023). Without respect for property rights, women are unable to inherit or own land and remain entirely dependent on their relationships with male relatives, which further exacerbates vulnerabilities for domestic violence.

When husbands and fathers are killed in the fight, women may experience a diminished social position in some societies. The death of men in civil conflict also increases the percentage of female-headed households, which can introduce new challenges. Women may be unable to inherit land owned by their husbands and forced out of their homes.

The damage to social capital and social networks is often under appreciated as families are separated or destroyed. In developing countries, where families often constitute the primary form of insurance, the death of workers and displacement of individuals away from other family members and family land can have an adverse effect on health and security in the society even after the conflict ends (Blattman & Miguel, Reference Blattman and Miguel2010). Thus, the effects of conflict may extend far into the future, well after armed conflict ceases.

When an economy experiences a major shock like a war or natural disaster, women are in a more vulnerable position as a result of their comparative poverty (True, Reference True2012) and weaker legal protections (World Bank, 2023). The economic consequences of war hit women harder and more quickly, especially when political inequality is high. These are the countries where we observe wars happening – states that enact policies that encourage gender equality (and enforce them) are less likely to engage in conflict (Hudson, et al., Reference Hudson, Ballif-Spanvill, Caprioli and Emmett2012). War exacerbates the negative societal impacts due to gender political inequality.

Displacement Effects

Building on the previous discussion about how conflict creates vulnerability for women, especially when gender inequality is high, we now consider the way armed conflict displaces populations. The people most likely to need to flee their homes in search of safety are women and children.

In recent decades, most of the conflict driven displacement has been caused by civil rather than international wars (Lischer, Reference Lischer2007). Much like the stories of every woman in a war zone, every story of displacement is different but fear, persecution, scarcity, and human suffering are often hallmarks of these tales. The lucky among them are able to seek refuge with family or friends, but many others make their ways to camps looking for food, shelter, and a modicum of security (Norwegian Refugee Council, 2002). Others may take shelter in isolated countryside, unsure of whether or where to find assistance. Groups that have fled are already under strain and fear for their physical and economic well-being (Iqbal, Reference Iqbal2010).

Women are more likely to be displaced or become refugees than men. Women are less likely to serve in armed conflict, and where gender equality is low, women have likely been exposed to violence at the hands of men – either in the broader society or in their own homes. Single-parent households led by women dominate the populations in refugee camps as women work to keep their children safe (Rehn & Sirleaf, Reference Rehn and Sirleaf2002). Often health conditions in refugee or internally displaced persons (IDP) camps are poor, and reproductive health services are unlikely to be provided in these facilities as the primary concerns tend to be on essential needs like food, water, shelter, and the most basic health care (McGinn, Reference McGinn2000).

When displaced individuals seek outside assistance, their concerns about well-being may not be completely alleviated. In fact, they are likely just shifted in another direction. Displaced persons face a number of risks, including a greater chance of disease transmission. The makeshift nature of refugee camps make them easy breeding grounds for illness. In addition, these camps are often in remote locations without access to health care and basic necessities such as clean water (Gleick, Reference Gleick1993; Hoddie & Smith, Reference Hoddie and Smith2009). Refugees and displaced persons are not evenly distributed across a country (Salehyan & Gleditsch, Reference Salehyan and Gleditsch2006), and thus, the health effects may not be evenly distributed. Getting supplies to these areas can be greatly complicated by on-going fighting.

Refugee camps often lack of consistent access to clean water, which degrades hygiene and increases the risk of infectious diseases (Ghobarah, Huth, & Russett, Reference Ghobarah, Huth and Russett2004; Gleick, Reference Gleick1993). The lack of water and firewood (or other sources of heat for cooking food) can also hinder the preparation nutritious food, leading to poor health and malnutrition (Toole & Waldman, Reference Toole and Waldman1993). Without water and nutritious food, refugee families often find themselves in a cycle of poor health and malnutrition (Toole & Waldman, Reference Toole and Waldman1993).

Displaced persons face a greater chance of disease transmission. The makeshift nature of refugee camps makes them easy breeding grounds for illness. In addition, these camps are often in remote locations and lack access to health care (Hoddie & Smith, Reference Hoddie and Smith2009). For example, Montalvo and Reynal-Querol (Reference Montalvo and Reynal-Querol2007) finds that for every 1,000 refugees that arrive in a country, an additional 2,700 cases of malaria occur in that receiving country. Congested camps in Ethiopia in the late 1980s had a huge outbreak of typhus, and dysentery and cholera devastated Rwandan refugees in 1994 (World Health Organization, 2003). Toole (Reference Toole, Levy and Sidel1997) reports mortality rates that are up to 100 times higher in these camps than the normal rates in the affected countries.

While refugees often face harsh health conditions, internally displaced people may suffer even more than refugees as their situations are often beyond the reach of international aid agencies (Toole & Waldman, Reference Toole and Waldman1993). According to the Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights, “internally displaced persons (also known as IDPs) are persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized border” (UNHCR, n.d.).

Displacement also has longer-term consequences as the population movements cause the disruption or destruction of social networks and social capital (Kondylis, Reference Kondylis2010). This can be particularly harmful in less developed countries where extended family networks are often the primary mechanism for insurance (Blattman & Miguel, Reference Blattman and Miguel2010). All of these challenges – reduced economic circumstances, physical threats, and the difficulties of keeping a family together – begin to wear on women who face high levels of anxiety and stress while living in these camps. Amowitz, Heisler, and Iacopino (Reference Amowitz, Heisler and Iacopino2003) found high rates of depression among displaced Afghani women living in Pakistan.

Economic assets will likely be lost and resettlement can be challenging, which again echoes the unique struggles women face due to the indirect economic costs of war. Displacement can lead to a vicious cycle of household poverty that is difficult to escape (Buvinic et al., Reference Buvinic, Das Gupta, Casabonne and Verwimp2013), especially in areas where property rights for women are limited. In Cote d’Ivoire where the primary wealth is held in land, the customary system of land ownership discriminates against women making it difficult or in some places impossible for women to own land (UN Women, 2020). For many women who were displaced by conflict there, when they returned home their claims to family land was either ignored or ruled against. Displaced populations often suffer physically, economically, and emotionally. Laws that reinforce gendered economic inequality exacerbate this suffering. If women lack standing in court or equal protection under the law, their efforts to rebuild their lives after war will be much more challenging than those of their male counterparts.

Gender-Based Violence Effects

Conflict-related sexual violence has some of the most obvious gendered consequences. Gender-based violence increases not only at the hands of enemies but also in the form of domestic abuse during conflict (True, Reference True2012). While men can also be the victims of such violence during conflict and women can also be perpetrators (Gentry & Sjoberg, Reference Gentry and Sjoberg2015; Sjoberg & Gentry, Reference Sjoberg and Gentry2007, Reference Sjoberg and Gentry2011), the victims are much more likely to be women (Cohen, Reference Cohen2013). Violence against women generally increases with the decline of law and order in conflict states. Under such conditions, women’s security may be threatened both inside and outside of their homes as the whole of society is ruled by aggression and violence (Rehn & Sirleaf, Reference Rehn and Sirleaf2002). Militarization changes societies and increases violence (Enloe, Reference Enloe2010). Conflict leads to a degrading of social norms about what is appropriate behavior, and more risk-taking occurs, which can have devastating effects on women. This type of violence has been employed as a weapon of war and of ethnic cleansing in civil conflicts around the world (Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2006; Cohen, Reference Cohen2013; Wood, Reference Wood2009).

Research suggests that some degree of sexual violence occurs in all conflicts, but that there is a great deal of variation in the type and extent (Cohen & Nordås, Reference Cohen and Nordås2014; Wood, Reference Wood2009). This type of violence has been employed as a weapon of war and of ethnic cleansing in civil conflicts around the world (Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2006; Cohen, Reference Cohen2013; Wood, Reference Wood2006).

The International Criminal Court (ICC) defines sexual violence as “an act of a sexual nature against one or more persons or caused such person or persons to engage in an act of a sexual nature by force, or by threat of force or coercion, such as that caused by fear of violence, duress, detention, psychological oppression or abuse of power, against such person or persons or another person, or by taking advantage of a coercive environment or such person’s or persons’ incapacity to give genuine consent” (Article 7(1) (g)-6) (International Criminal Court, 2011). This includes rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, and forced sterilization/abortion.Footnote 3 Cohen (Reference Cohen2013) suggests that while wartime rape may be devastating for both the victims and the perpetrators, it should be considered independently from lethal uses of force, building on Wood (Reference Wood2009) which notes that patterns of rape are distinct from those associated with homicide and displacement in war. In addition, rape is often utilized as the alternative for mass killings of male populations, especially in circumstances of ethnic conflict.

While rape may be used during war either strategically or opportunistically, intimate partner violence also increases greatly both during and after conflict (Mooney, Reference Mooney2005). When gender inequality is high, domestic violence is already occurring at a higher rate than in more equal societies. While research has put the focus on mass sexual violence like strategic rape, these acts as part of a broader range of gender-based violence (True, Reference True2012). Violence against women more generally increases with the decline of law and order in conflict states. Under such conditions, women’s security may be threatened both inside and outside of their homes as the whole of society is ruled by aggression and violence (Rehn & Sirleaf, Reference Rehn and Sirleaf2002). Militarization changes societies and increases violence (Enloe, Reference Enloe2010). Conflict leads to a degrading of social norms about what is appropriate behavior, and more risk-taking occurs. Both domestic violence and sexual abuse in the home also increase.

Women can be sexually assaulted as a means of humiliating their families (Rehn & Sirleaf, Reference Rehn and Sirleaf2002). Civilian terror is a tactic of war, one that is being employed more frequently in modern conflict. Women may also feel obligated to trade sex for protection from local rebel leaders. Gender-based violence increases not only at the hands of enemies, but also in the form of domestic abuse during conflict (True, Reference True2012). During civil war, gender stereotypes are not only reinforced but often increase in strength (Goldstein, Reference Goldstein2001). Sexual violence is more likely when the stereotypes reinforce traditional gender roles.

An additional issue related to sexual violence as well as women’s health is the challenge of HIV/AIDS. The head of UNAIDS has noted that “conflict and HIV are entangled as twin evils” (quoted in Elbe (Reference Elbe2002, p. 160)). The violent nature of these attacks can also increase the likelihood of infection (Singer, Reference Singer2002). In Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, soldiers expressed a stated intention of transmitting the disease through rape (UNAIDS, 2000). While Spiegel (Reference Spiegel2004) has demonstrated that the link between conflict and HIV prevalence is complex, women and displaced persons are often a greater risk for infection in war torn countries. Women are vulnerable due to their physiological and social disadvantages. Treatment and appropriate drugs for many sexually transmitted diseases are relatively common, but medical attention and medication are often difficult to obtain in conflict states.

Connecting these issues to the challenges of displacement, women in refugee camps often find that they need to be constantly vigilant because of the increased threat of sexual violence to themselves and their children (Sjoberg, Reference Sjoberg2013). Women may also have to guard against those who would attempt to recruit their children into the fighting. These women are also often separated from their extended families, which can complicate the process of returning or rebuilding after displacement.

Sexual violence against women often come with a stigma or results in the blaming of the victim. When women lack a political voice and feel unprotected by the legal system, sexual violence may already be a regular occurrence even before armed conflict breaks out. When the war begins, this societal pattern will be intensified. The wartime challenges that women face are both a result and a reflection of the position of women in peacetime (True, Reference True2012).

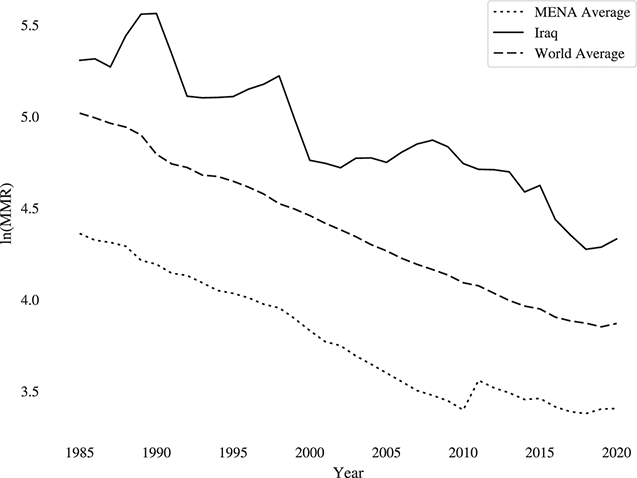

Women’s Health Outcomes during Conflict

In the previous sections, we have laid out three ways that armed conflict could negatively impact the health of women in distinct ways, but we also know that health policies created during peace time have gendered consequences. To demonstrate the difference between the health outcomes that women experience in countries at peace versus those in countries at war, we constructed a dataset of 146 countries between 1990 and 2019. As we will do in Sections 2 and 3, we focus here on two major measures of women’s health – Female Life Expectancy, which measures life expectancy at birth for women measured in years (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg and Holmberg2023; World Bank, 2022) and the natural log of the maternal mortality rate, ln(MMR) (World Health Organization, 2023). We use a dichotomous variable measuring the presence of Civil Conflict (Davies, Pettersson, & Öberg, Reference Davies, Pettersson and Öberg2022; Gleditsch et al., Reference Gleditsch, Wallensteen, Eriksson, Sollenberg and Strand2002). We include a measure of gendered political inequality by including the women’s Political Empowerment Index, which measures women’s political empowerment (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2023b; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt and Tzelgov2023).

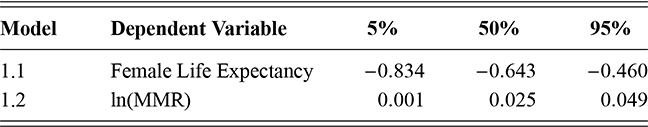

Table 1 includes the first differences of the Conflict variable from two Bayesian hierarchical linear models of women’s health outcomes – Female Life Expectancy and ln(MMR).Footnote 4 The results clearly show that the presence of a conflict, in comparison to those countries without a civil conflict, undermines women’s health outcomes. The presence of a civil conflict decreases Female Life Expectancy by 0.643 years. Conflict increases the ln(MMR) by 0.025, which represents a 2.5% increase in the maternal mortality rate. Thus, while women may face obstacles to health care in countries at peace, we find evidence that the presence of civil conflict worsens outcomes. Along with the theoretical discussion earlier, we take this as our jumping off point for turning our focus to the inter related impacts of political inequality on both the causes and consequences of war. Where women lack political agency, their health suffers. When conflict occurs in those countries, the problems are magnified.

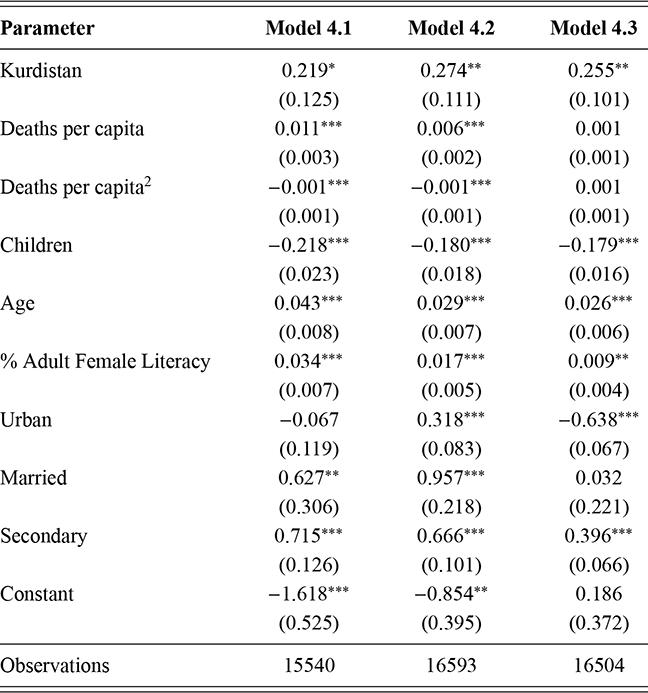

| Model | Dependent Variable | 5% | 50% | 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | Female Life Expectancy | −0.834 | −0.643 | −0.460 |

| 1.2 | ln(MMR) | 0.001 | 0.025 | 0.049 |

Note: Table reports the posterior median and 90% Credibility Intervals.

Making the Connections

Our review of the literature on women and conflict leads to a critical conclusion – gender, and, more specifically, the political inequalities defined by gendered hierarchiess impact both the causes and consequences of war. First, the evidence clearly demonstrates that the unequal treatment of women increases the probability of conflict. Second, the impact of war on women is significant, due to their unequal status in society. The impact of gender hierarchies is cemented into place by political inequality. Despite the fact that women suffer fewer combat deaths, they are far more likely to suffer the indirect consequences of war. This is an effect of the fact that violence is far more likely in gender unequal societies. These processes are inextricably linked.

In today’s conflicts, women face substantial morbidity and mortality consequences (Bendavid et al., Reference Bendavid, Boerma and Akseer2021), in large part because of their unequal positions before and during conflict. Where women lack a political voice, gender inequalities of all types (political, economic, and social) will lead to heightened consequences. When women are under represented in government and discriminated against in political institutions like the judicial system, they will suffer from reduced social safety nets, damaged infrastructure, weakened economies, insecurities associated with displacement, and sexual violence – all of which can lead to increased mortality and morbidity. Evidence suggests that women’s descriptive representation leads to improved women’s health outcomes (Mechkova & Edgell, Reference Mechkova and Edgell2023).

Recognizing this fact leads us to the expectation that both the presence and impact of conflict will depend, in part, on the level of gender inequality in a society. While women in nearly every country are poorer than men and have a more limited voice in politics, the inequality between men and women varies across countries. Existing research on the position of women in different societies finds strong evidence that states vary across key indicators such as the percentage of women in the legislature (Schwindt-Bayer & Squire, Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Squire2014), maternal mortality rate (Banda et al., Reference Banda, Odimegwu, Ntoimo and Muchiri2017), and access to education (Zahidi, Reference Zahidi2023), among others. If gendered inequality explains the cause and consequences of war, then we would expect that variation in inequality will lead to variation in both the presence and consequence of war. Conflict typically occurs in countries where women’s status is lower compared to men. As a result, the women’s health consequences from war are significant because we are only observing them in states where women are in a position of political weakness. They lack voices in legislative bodies and the policies that have been created by those legislatures have not been centered on their needs.

Recognizing that women’s political equality affects both the likelihood and consequences of civil conflict complicates how we measure the effects of civil conflict on women’s health. Unless dealt with this, our empirical analysis could suffer from selection bias. Selection bias arises when variables affect not on the creation of the sample but also the outcomes in which we are interested (Böhmelt & Spilker, Reference Sartori2003; Sartori, Reference Böhmelt and Spilker2020). The presence of selection bias could lead to biased estimations from our outcome equations (Heckman, Reference Heckman1979). The concern is important enough that issues of selection bias are common in the broader IR scholarship (Böhmelt & Spilker, Reference Böhmelt and Spilker2020; Clayton & Dorussen, Reference Clayton and Dorussen2021; Dorussen, Böhmelt, & Clayton, Reference Dorussen, Böhmelt and Clayton2022).

We argue that selection bias likely affects our analysis based on the existing theoretical literature for several reasons. There could be unmeasured factors that influence both the likelihood of conflict and women’s health outcomes. Countries that have weak gender equality are more likely to suffer not only from conflict but also from weak women’s health outcomes. Thus, to accurately understand the effects of civil conflict on women’s health, we need to take into account the issue of selection bias.

To test our argument about the inter relationship between gender inequality and conflict, we use two different empirical strategies. First, we employ regression analysis using our cross-sectional time-series dataset of global civil conflicts between 1990 and 2019. For this analysis, we utilize a two-stage Bayesian Heckman selection model.Footnote 5

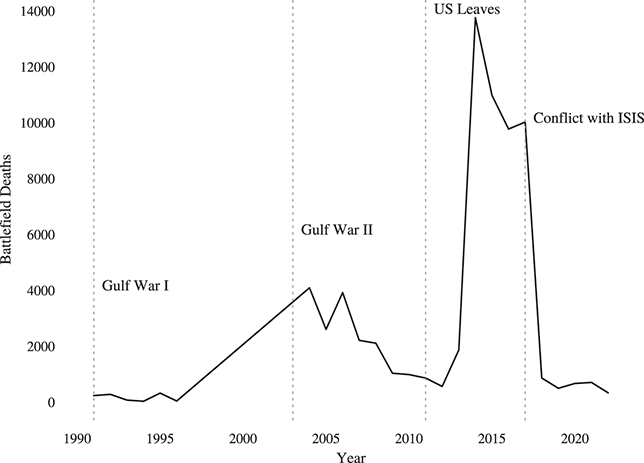

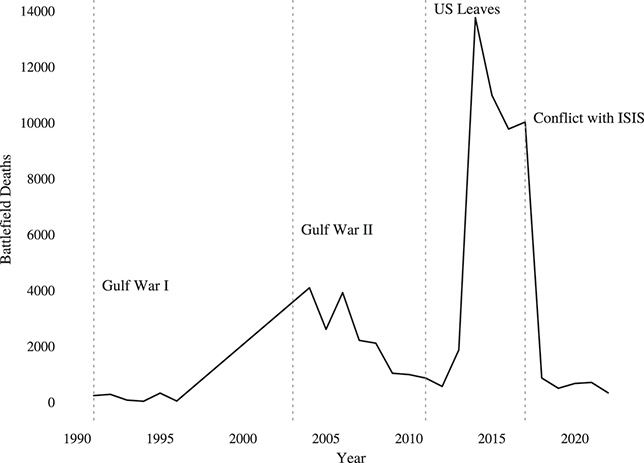

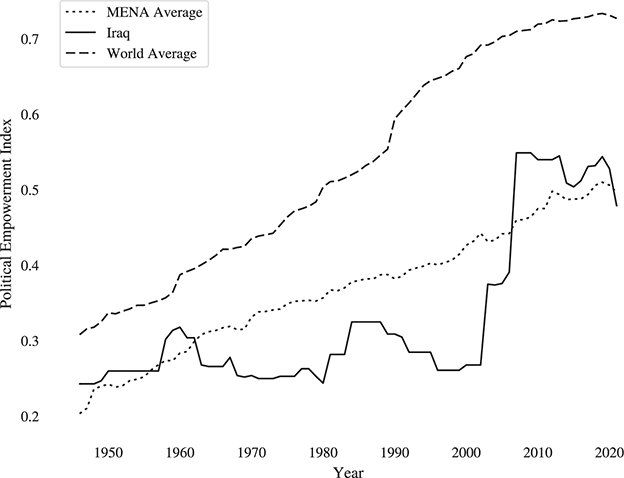

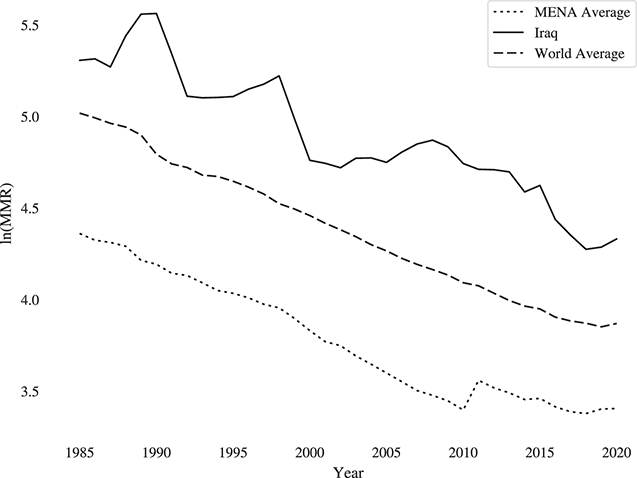

Second, we undertake a case-study of Iraq in the early twenty-first century. We believe Iraq offers an interesting testing ground for our theory because of differences between the laws governing women’s political empowerment in south and central Iraq versus the Kurdish Regional Government. Women in the Kurdish region have been serving in the regional parliament since 1992, and in 2012, they held nearly one third of the seats. Comparing women’s health outcomes across governorates allows us to examine whether improvements in women’s social position increase the uptake of services that lessen maternal mortality.

Plan for the Element

In this Element, we empirically test the implications of the sample selection that results from gender inequality. In the places where wars occur, women are vulnerable and we expect that as that vulnerability increases, women will suffer greater negative health and well-being effects from war.

In Section 2, we focus on how armed conflict affects female life expectancy. Several previous studies have examined whether conflict is related to changes in female life expectancy (e.g., Li & Wen, Reference Li and Wen2005; Plümper & Neumayer, Reference Plümper and Neumayer2006), but they fail to acknowledge how women’s position in society affects the likelihood of violence that causes these negative outcomes. In Section 3, we examine maternal mortality rates. As with life expectancy, maternal mortality rates have been examined in other studies of conflict effects (e.g., Kotsadam & Østby, Reference Kotsadam and Østby2019; Kottegoda, Samuel, & Emmanuel, Reference Kottegoda, Samuel and Emmanuel2008; Tamura et al., Reference Tamura, Hinderaker, Manzi, Van Den Bergh and Zachariah2012; Urdal & Che, Reference Urdal and Che2013), but again, none of these studies regarding female life expectancy or maternal health consider the connection between causes and consequences of conflict.

While female life expectancy and maternal mortality (MMR) are related, they have different underlying mechanisms. In order to predict levels of maternal mortality in a society, population characteristics such as size, poverty rates, and percentage of those living in cities are important indicators. When we think about life expectancy, on the other hand, conflict characteristics like the length of the war and its intensity as well as the regime type of the conflict state are important predictors. Because different societal forces are driving these outcomes, we think it is important to consider how the inter relationship between conflict and gender inequality might affect them.

Additionally, maternal mortality is in and of itself gendered in nature. In unequal societies, policies may exist that do not prioritize maternal health. Life expectancy, on the other hand, is not. Even in unequal societies, investments in programs that enhance men’s health could lead to improvements in life expectancy, even if women have a more difficult time accessing them.

In Section 4, we take an in-depth look at how decades of violence in Iraq have affected women. The type of conflict has varied over time and location within the country as has the intensity. Examining the experiences of Iraqi women allows us to pinpoint how exposure to violence affects women’s well-being. In addition, the laws regarding women’s political empowerment are not the same across the whole state of Iraq. The Kurdish Regional Government has had the opportunity since 1991 to pass distinct laws, differences have emerged. In this section, we examine whether or not these policy differences have an impact on women’s well-being.

Finally, in Section 5, we briefly review our findings, noting their importance. Moreover, we expand on the policy implications of our results. If anything, our analysis highlights the importance of gendered political inequality in reducing both the incidence of civil conflicts and its consequences as well. These findings strengthen the international community’s case for bringing more women into peace processes and the political systems that created or revised as a result of armed conflict.

Appendix

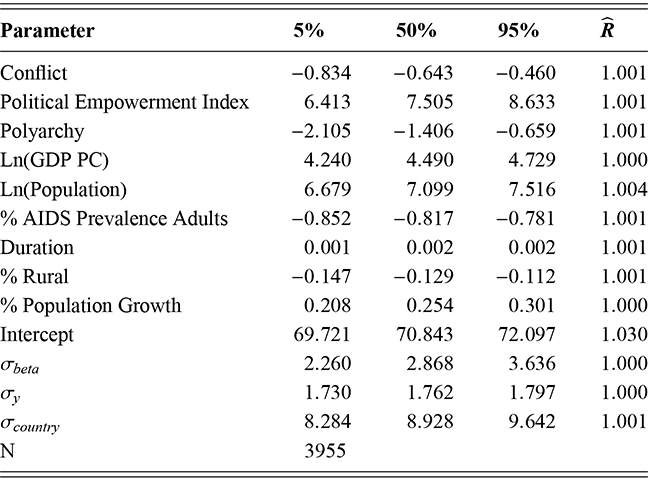

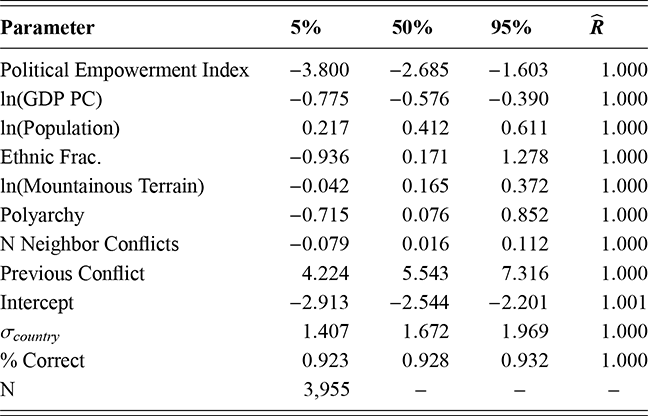

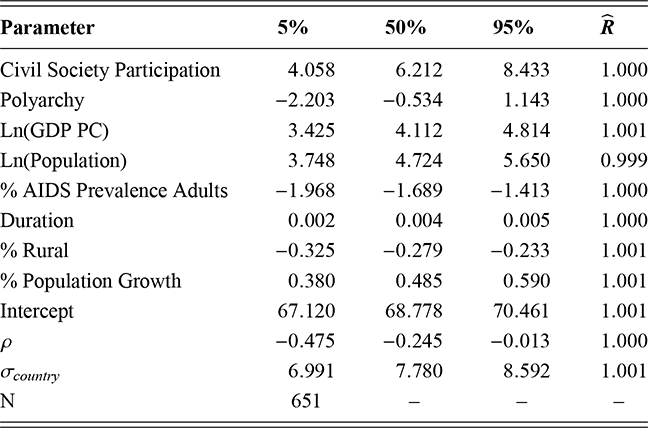

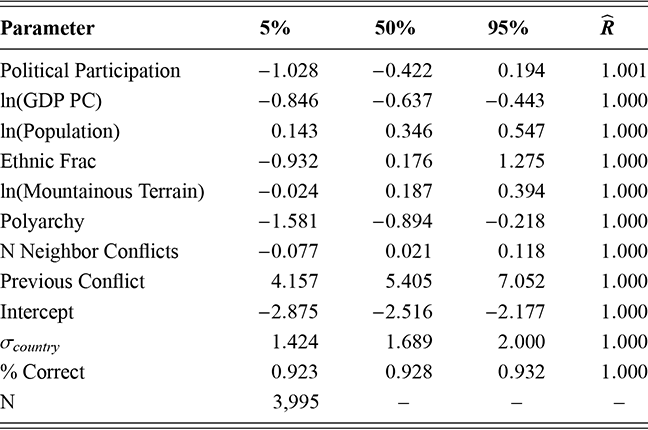

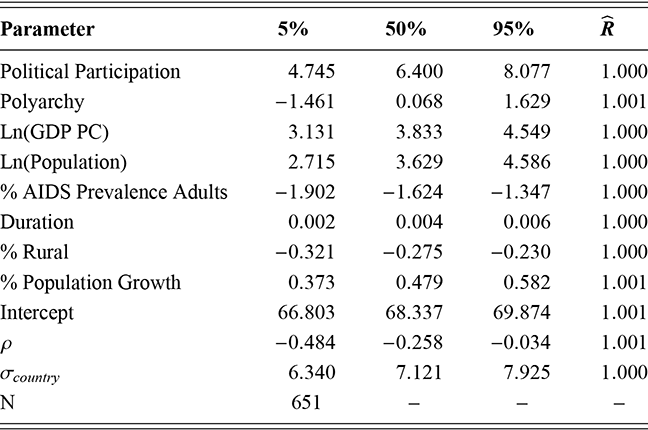

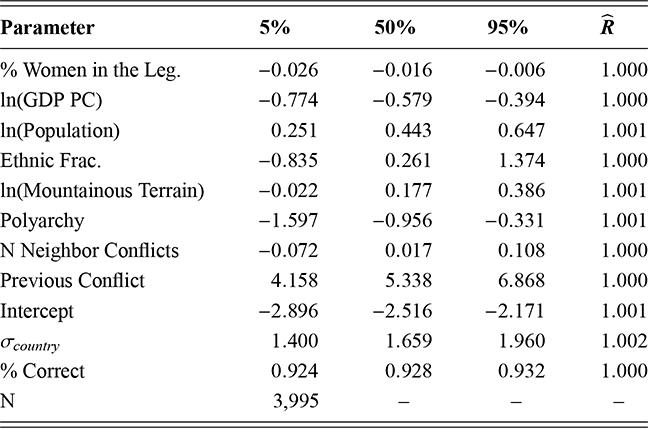

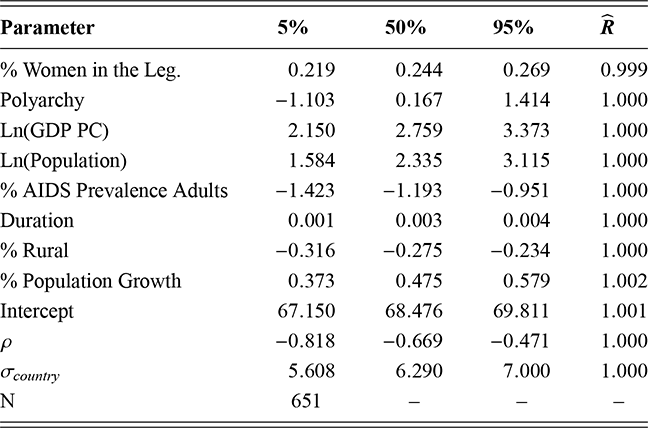

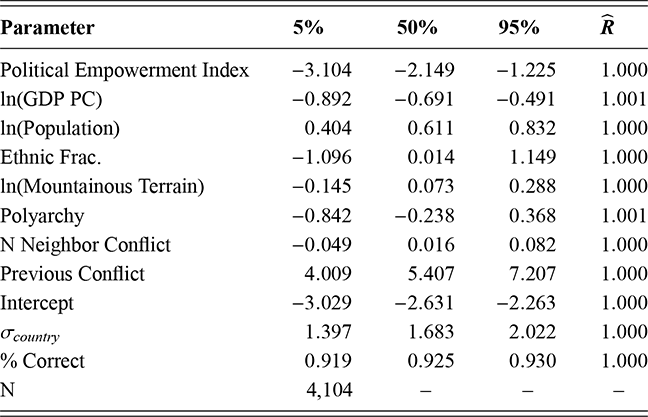

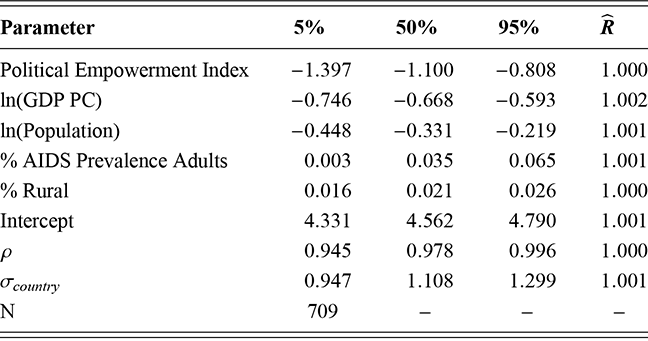

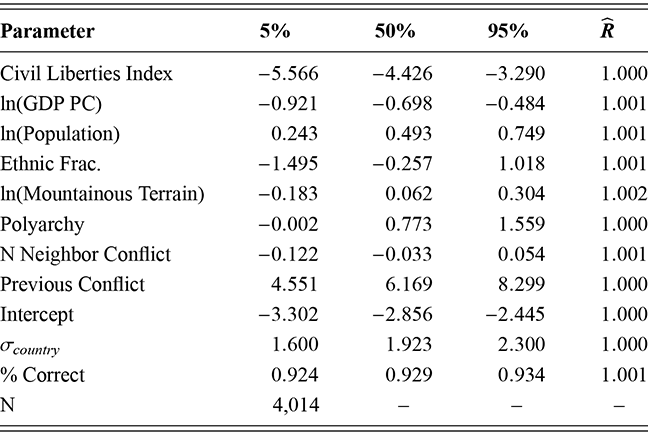

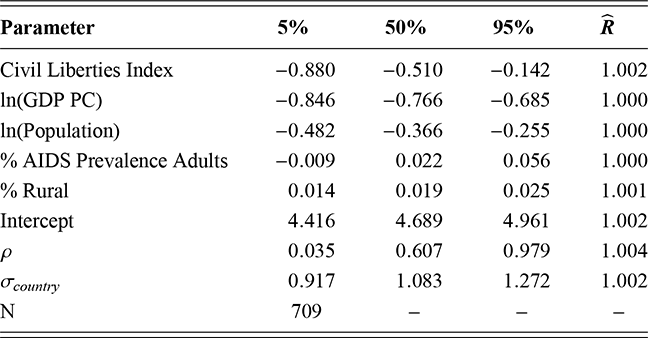

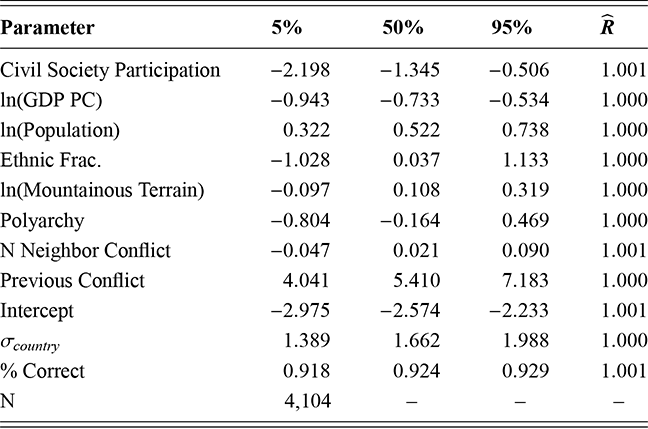

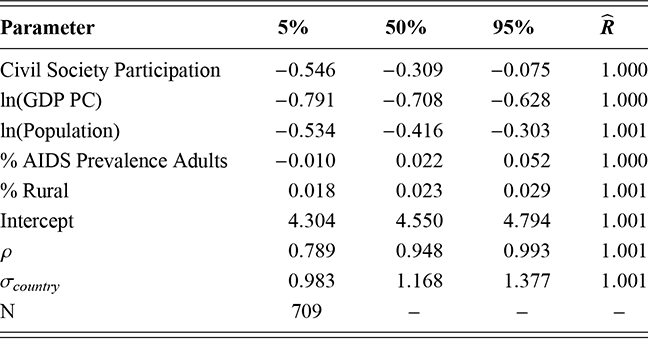

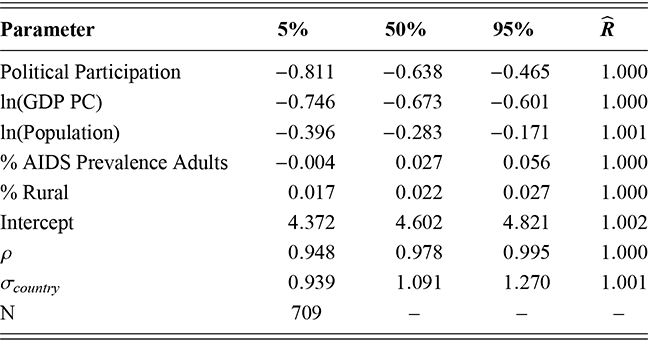

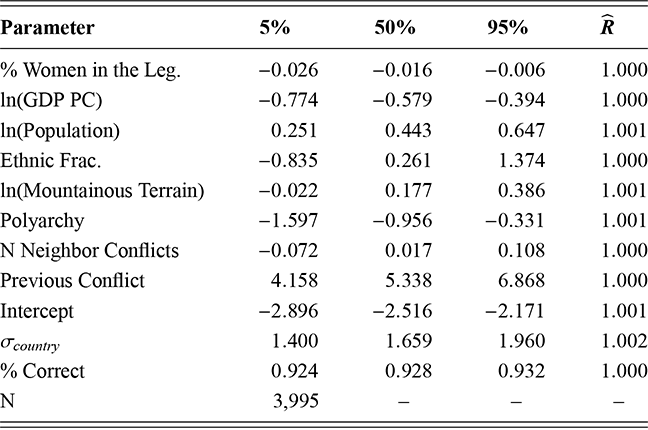

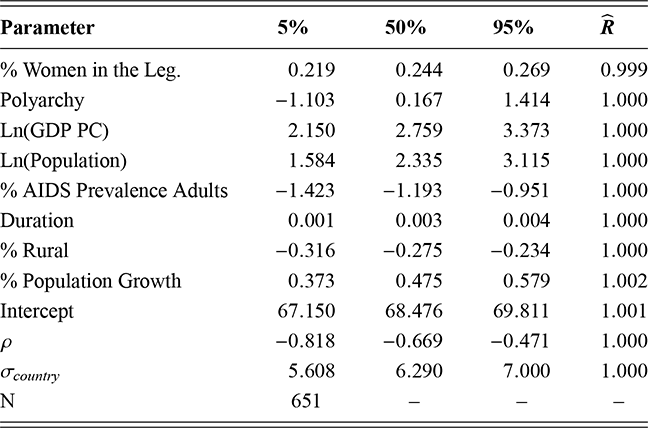

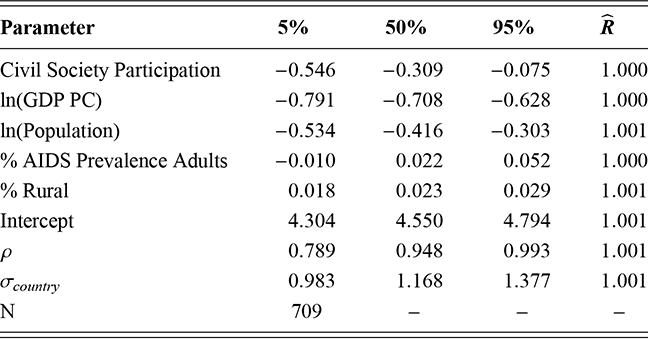

The estimates reported in figure 1 are taken from the models reported in Tables 2 and 3. We estimated both models using a Bayesian hierarchical-linear model with random intercepts for individual countries. We estimated 10,000 iterations with a burn-in of 5,000 iterations for each model. The diagnostics, included in the detailed results, indicate that each model converged.

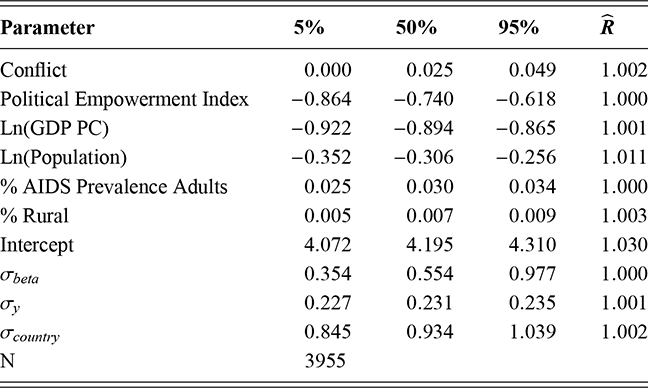

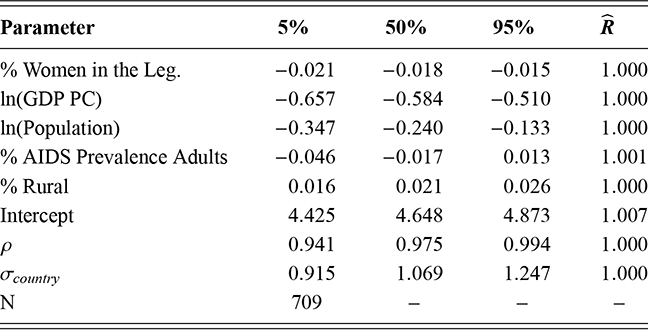

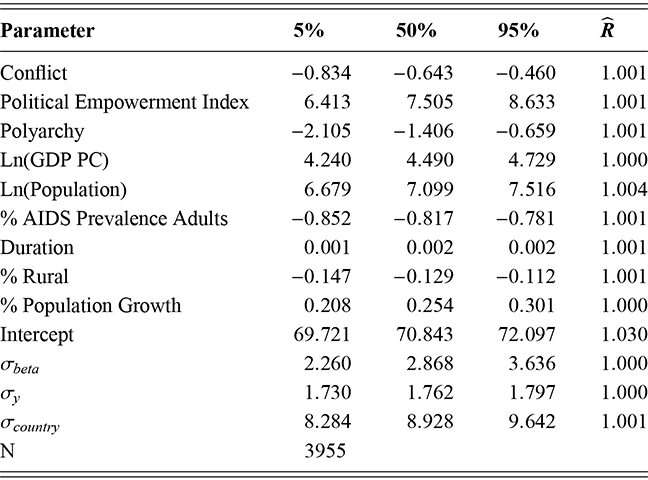

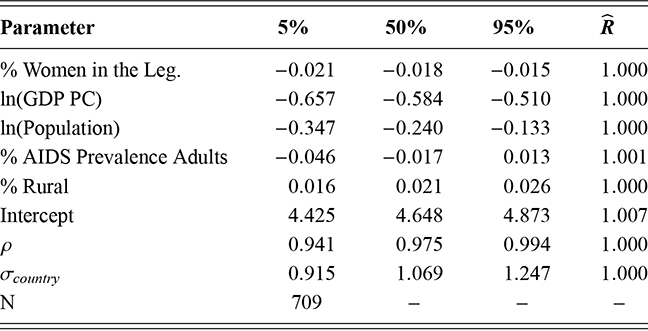

Note: Table reports the posterior coefficient and parameter estimates.

Table 2Long description

The table has 5 columns: Parameter, 5 percent, 50 percent, 95 percent, and R hat. It reads as follows. Row 1: Conflict; minus 0.834; minus 0.643; minus 0.460; 1.001. Row 2: Political Empowerment Index; 6.413; 7.505; 8.633; 1.001. Row 3: Polyarchy; minus 2.105; minus 1.406; minus 0.659; 1.001. Row 4: l n (G D P P C); 4.240; 4.490; 4.729; 1.000. Row 5: l n (Population); 6.679; 7.099; 7.516; 1.004. Row 6: Percentage AIDS Prevalence Adults; minus 0.852; minus 0.817; minus 0.781; 1.001. Row 7: Duration; 0.001; 0.002; 0.002; 1.001. Row 8: Percentage Rural; minus 0.147; minus 0.129; minus 0.112; 1.001. Row 9: Percentage Population Growth; 0.208; 0.254; 0.301; 1.000. Row 10: Intercept; 69.721; 70.843; 72.097; 1.030. Row 10: Sigma beta; 2.260; 2.868; 3.636; 1.000. Row 11: Sigma y; 1.730; 1.762; 1.797; 1.000. Row 12: Sigma country; 8.284; 8.928; 9.642; 1.001. Row 13: N: 3955.

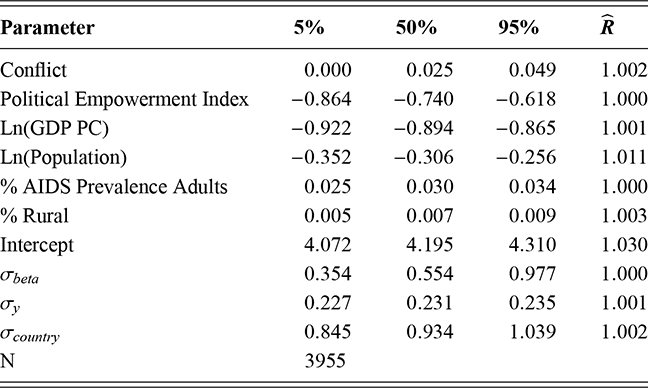

Note: Table reports the posterior coefficient and parameter estimates.

Table 3Long description

The table has 5 columns: Parameter, 5 percent, 50 percent, 95 percent, and R hat. It reads as follows. Row 1: Conflict; 0.000; 0.025; 0.049; 1.002. Row 2: Political Empowerment Index; minus 0.864; minus 0.740; minus 0.618; 1.000. Row 3: l n (G D P P C); minus 0.922; minus 0.894; minus 0.865; 1.001. Row 4: l n (Population); minus 0.352; minus 0.306; minus 0.256; 1.011. Row 5: Percentage AIDS Prevalence Adults; 0.025; 0.030; 0.034; 1.000. Row 5: Percentage Rural; 0.005; 0.007; 0.009; 1.003. Row 6: Intercept; 4.072; 4.195; 4.310; 1.030. Row 7: Sigma beta; 0.354; 0.554; 0.977; 1.000. Row 8: Sigma y; 0.227; 0.231; 0.235; 1.001. Row 9: Sigma country; 0.845; 0.934; 1.039; 1.002. Row 10: N: 3955.

For both models, we included our Conflict dummy variable to estimate the effects of civil conflict on health outcomes (Davies, Pettersson, & Öberg, Reference Davies, Pettersson and Öberg2022; Gleditsch et al., Reference Gleditsch, Wallensteen, Eriksson, Sollenberg and Strand2002). In model 1.1, Table 2, the dependent variable is Female Life Expectancy (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg and Holmberg2023; World Bank, 2022). In model 1.2, Table 3, we measured women’s health outcomes with the natural log of the maternal mortality rate ln(MMR). Again, our measure for women’s political equality was taken from V-Dem–Political Empowerment Index, which measures women’s political empowerment (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2023b; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt and Tzelgov2023).

We include a set of control variables typical for models of female life expectancy, model 1.1. We control for differences in levels of democracy by including Polyarchy (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2023b; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt and Tzelgov2023). Life expectancy may vary by wealth, so we include the natural log of GDP per capita, Ln(GDP PC) (Bolt & van Zanden, Reference Bolt and van Zanden2020; Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg and Holmberg2023). We control for differences in population with the natural log of population ln(Population) (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg and Holmberg2023; World Bank, 2022). Variation in AIDS prevalence may lead to differences in female life expectancy; consequently, we include the % AIDS Prevalence Adults to control for greater death rates due to HIV (UN AIDS, 2023). Regime stability may matter, so we code all observations with the duration of the current regime in years Duration (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2023b; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt and Tzelgov2023). Differences in urban and rural areas may matter so we include the percentage of the population living in rural areas, % Rural Population (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg and Holmberg2023; World Bank, 2022). Finally, we include the rate of population growth, % Population Growth (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2023b; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt and Tzelgov2023).

We utilize a similar set of controls of our model of ln(MMR), model 1.2 in Table 3. We include the Ln(GDP PC), % Rural, % AIDS Prevalence Adults, and ln(Population) (Bolt & van Zanden, Reference Bolt and van Zanden2020; Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg and Holmberg2023; UN AIDS, 2023).

2 Gendered Political Inequality and Life Expectancy in Conflict Countries

In this section, we begin our examination of the gendered health consequences of war. Estimating the effect of conflict on life expectancy is a common method of estimating the societal impacts of war (e.g., Gates et al., Reference Gates, Hegre, Nygård and Strand2012; Plümper & Neumayer, Reference Plümper and Neumayer2006). If the expectation is that conflict has a deleterious effect on women’s health, then this is an obvious first place to look.

Women’s life expectancy in all countries – regardless of whether or not they experience conflict – is influenced by their position in society. Access to health care and education as well as income levels and social safety nets all influence life expectancy and are influenced by gender equality. Life expectancy for women will be lower where women’s positions in society are lower. This must be taken into account when examining the life expectancy consequences of conflict for women. Women in conflict societies already have lower rates of life expectancy when the first shot is fired compared to their counterparts in more peaceful societies.

Life Expectancy and Political Equality

Life expectancy at birth is understood to be a good indicator of overall population health and is shaped by various factors, many of which are influenced by gender (Pinho-Gomes, Peters, & Woodward, Reference Pinho-Gomes, Peters and Woodward2023). Does the level of gendered political inequality impact women’s life expectancy? Based on the existing research, there is strong evidence to believe that it does. Because of the traditional gender hierarchies around the world, men in all countries, regardless of income level, have more control over their lives (UNDP, 2018). They have greater access to political power, economic resources, and the political processes by which resource allocation decisions are made. Where women lack political agency, their life expectancy may be lower.

Policies that promote gender equality should improve female life expectancy (Mateos et al., Reference Mateos and Fernández-Sáez2022). Focusing on political equality, government policies on health can be influenced by the presence (or absence) of women in the legislature and women’s political engagement and empowerment. Women are more committed to social issues (Karam & Lovenduski, Reference Karam and Lovenduski2005; Reingold, Reference Reingold2003; Welch, Reference Welch1985). Women’s representation increases social spending (Bolzendahl & Brooks, Reference Bolzendahl and Brooks2007), and an increase in the share of women in cabinet is associated with an increase in public health spending (Mavisakalyan, Reference Mavisakalyan2014). In developing countries where women make up at least 20% of the lower house of the legislature, health outcomes like measles immunization, DPT immunizations, and infant and child morality all improve, and incremental increases in women’s representation lead to the greatest improvement in socially and economically disadvantaged countries (Swiss, Fallon, & Burgos, Reference Swiss, Fallon and Burgos2012).

Female legislators often prioritize women’s health once they take office. In Argentina, female legislators introduced 80% more pieces of legislation on reproductive rights than their male counterparts (Franceschet & Piscopo, Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008). Beyond introducing legislation regarding women’s health, Westfall and Chantiles (Reference Westfall and Chantiles2016) shows that women’s health outcomes are better in countries where women’s representation is higher, particularly as a result of gender quotas.

With greater political engagement by educated women, investment specifically in women’s health increases. In the next section, we discuss maternal health in greater detail, but investment in women’s health results in more midwives (Van Lerberghe et al., Reference Van Lerberghe, Matthews and Achadi2014), more contraception (Bentley & Kavanagh, Reference Bentley and Kavanagh2008), and lower fertility rates (Beer, Reference Beer2009; Fuse & Crenshaw, Reference Fuse and Crenshaw2006), all of which improve female life expectancy.

Women’s Life Expectancy in Conflict Societies

Now we turn to examining the impact of conflict on women’s life expectancy. Several existing studies suggest that on balance that the impact of civil conflict is disproportionately felt by women (Li & Wen, Reference Li and Wen2005; Plümper & Neumayer, Reference Plümper and Neumayer2006; Rehn & Sirleaf, Reference Rehn and Sirleaf2002; Rehn.Sirleaf.2002,). The impact may vary over time as the health effects of conflict for men may be more concentrated in the short- and medium-term, while the effects for women have the potential to be longer-term (Ghobarah, Huth, & Russett, Reference Ghobarah, Huth and Russett2003). Gates et al. (Reference Gates, Hegre, Mokleiv Nygård and Strand2010) find a deleterious effect in fragile states, but it is unclear whether the conflict or state fragility is the driving factor. In a more recent study, Hoddie and Smith (Reference Hoddie and Smith2009) find that the health costs of conflict for women vary by age cohort. With a more refined estimation strategy, we attempt to clarify relationship found in some, but not all, previous studies.

Conflict may also indirectly affect well-being by decreasing the availability of education, particularly to women and girls (Buvinić, Das Gupta, & Shemyakina, Reference Buvinić, Das Gupta and Shemyakina2014; Guha-Sapir & D’Aoust, Reference Guha-Sapir and D’Aoust2011; Shemyakina, Reference Shemyakina2011). While improvements in female literacy lead to improved health and well-being, the inverse is also true. National literacy rates also correspond to life expectancy with better-educated populations enjoying longer lives (Kabir, Reference Kabir2008). These indirect economic consequences of war, including the destruction of infrastructure, degraded public education, and increased poverty, are all likely to hit women hard and to negatively impact women’s health. The impact of all of these consequences will be magnified in countries where women lack equal political, social, and economic access.

As the economic costs rise and civilian infrastructure is destroyed, women may lack the ability to access life saving health care. Funding for public health services may be cut or shifted to military efforts, thus also diminishing care. Women are more likely to depend on such services. Women’s health services are also more likely to be on the budgetary chopping block in societies where women’s political voices are muted.

When populations are displaced, the ability to access care is disrupted. Refugee camps have notoriously poor sanitation, and communicable disease often runs rampant. Women dominate the populations of such camps. Displaced women and girls face greater challenges to their well-being than their male counter-parts.

In addition, sexual violence and sexually transmitted disease will likely increase, which can also have an negative impact on women’s life expectancy. This size of this effect will be greater in societies where women lack political voice and violence against women is seen as more acceptable.

Based on the discussion earlier, we expect that the likelihood of conflict will depend on gendered political equality, which should in turn influence the negative consequences on women’s health. Because more unequal states are more likely to experience conflict, women in conflict states are more likely to experience larger, negative impacts on life expectancy than in those societies that are more equal. Consequently, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2.1: In conflict countries, as women’s political empowerment decreases, women’s life expectancy will decrease.

Measuring the Impact of Conflict on Life Expectancy

We test our hypotheses using a dataset of 145 countries between 1990 and 2019. The unit of analysis is country-year. As mentioned previously, we utilize a two-stage Bayesian Heckman selection model to control for the potential selection effects on conflict consequences.Footnote 6 We include random intercepts at the country level to control for differences in variance estimates by country. We mean center all of our model continuous covariates to ease convergence.Footnote 7 The ![]() parameters for models 2.1–2.5 are statistically significant and negatively correlated, varying between

parameters for models 2.1–2.5 are statistically significant and negatively correlated, varying between ![]() and

and ![]() ; these results support our decision to use a selection model.Footnote 8 For all second-stage covariates, which were included in the first stage, we adjust the coefficients to take into account their impact on the probability of conflict (Sweeney, Reference Sweeney2003).

; these results support our decision to use a selection model.Footnote 8 For all second-stage covariates, which were included in the first stage, we adjust the coefficients to take into account their impact on the probability of conflict (Sweeney, Reference Sweeney2003).

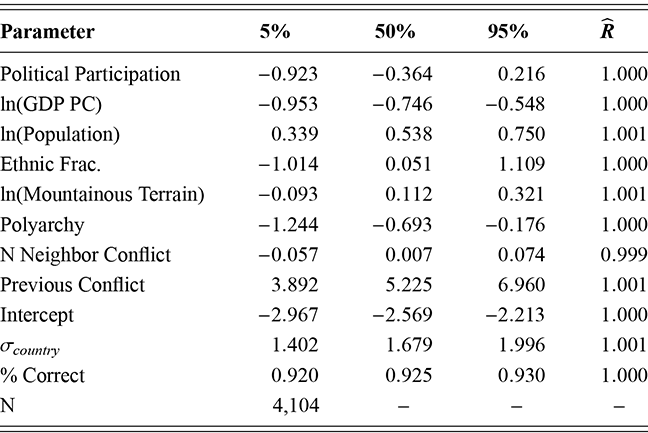

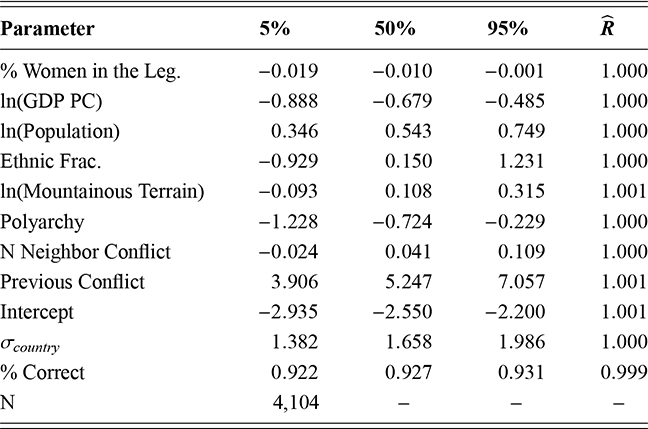

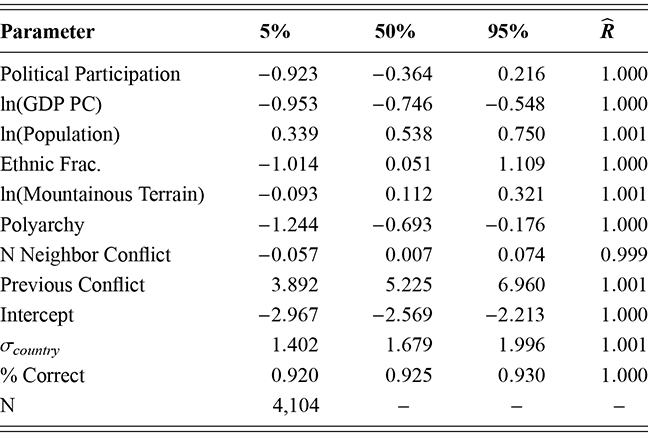

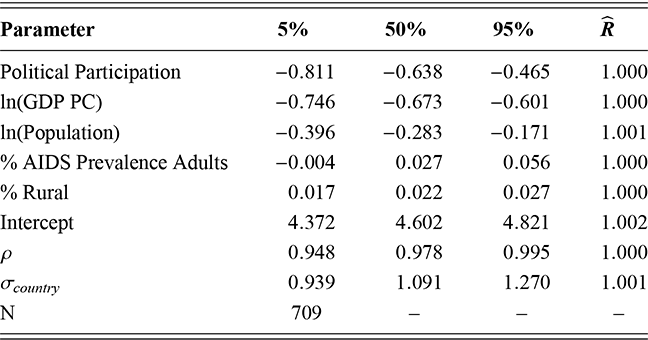

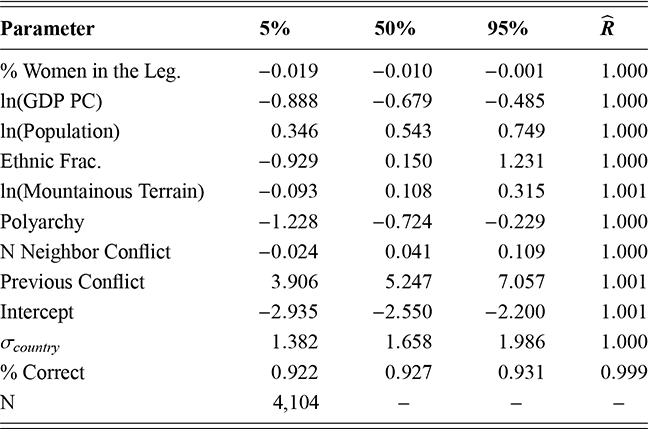

Our first stage models conflict. Our dependent variable, Conflict, indicates whether an intrastate conflict occurred in the country in a given year (Davies, Pettersson, & Öberg, Reference Davies, Pettersson and Öberg2022; Gleditsch et al., Reference Gleditsch, Wallensteen, Eriksson, Sollenberg and Strand2002). In the second stage, our dependent variable is Female Life Expectancy, which measures life expectancy at birth for women measured in years (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg and Holmberg2023; World Bank, 2022).

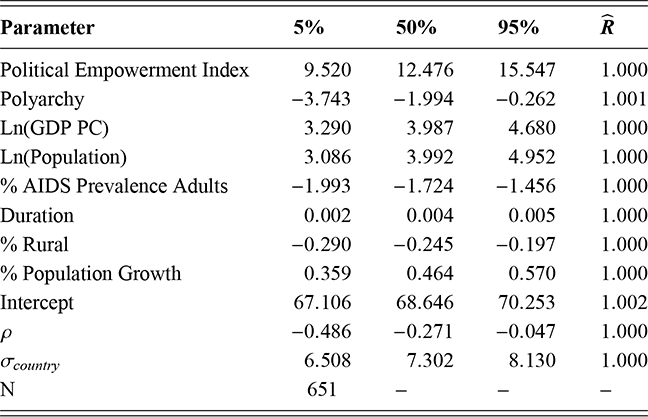

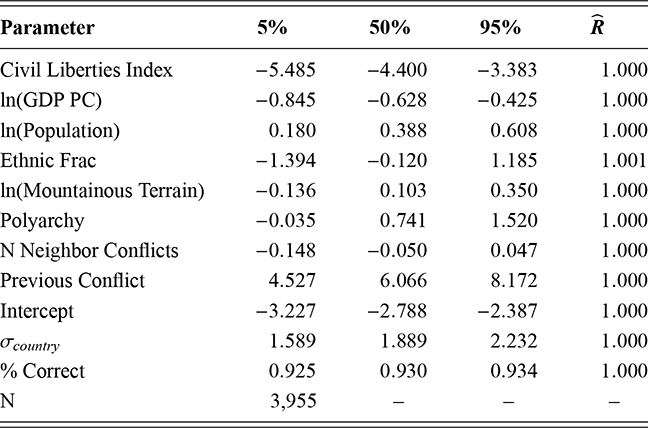

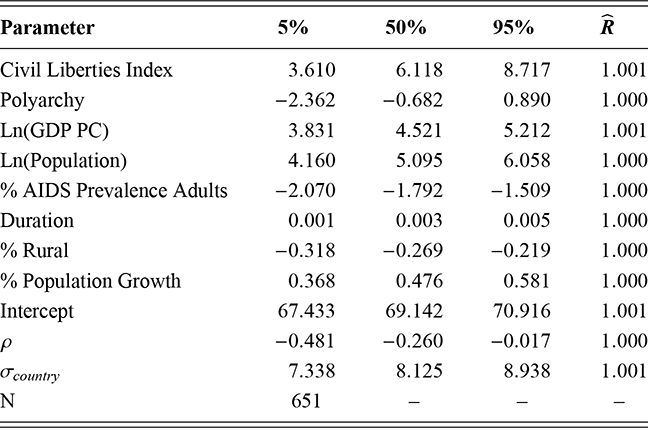

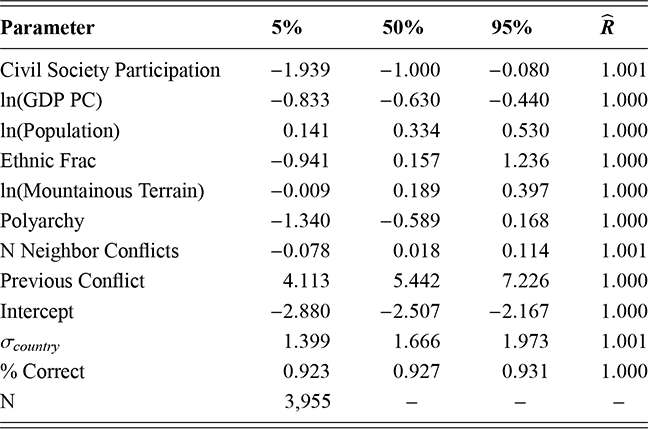

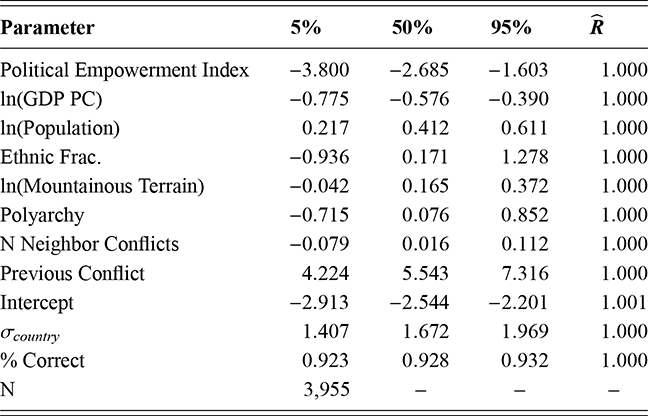

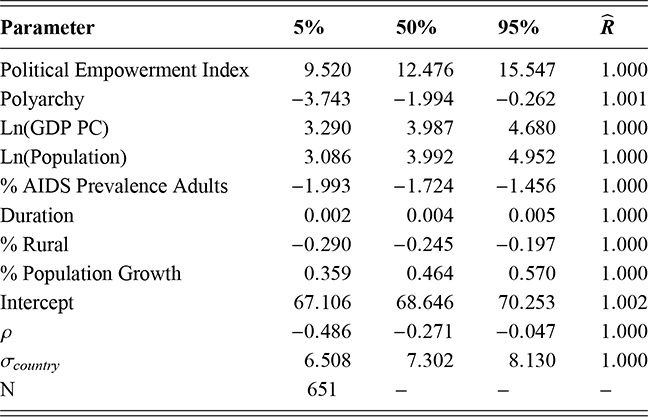

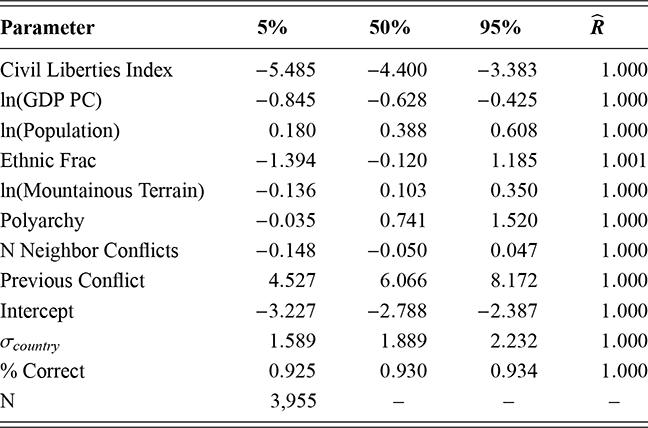

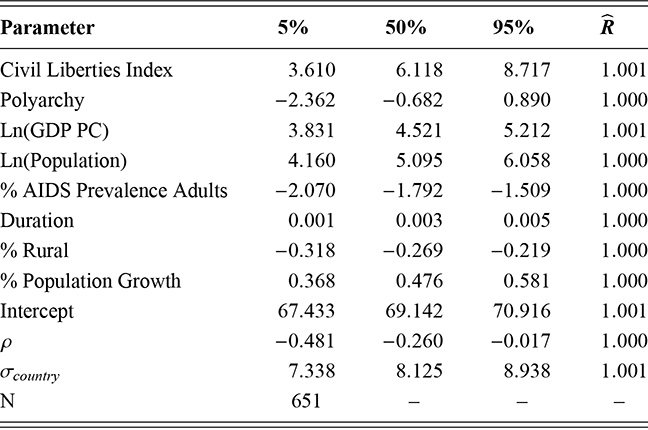

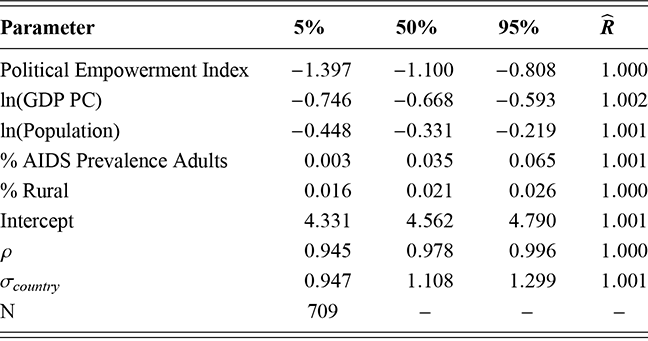

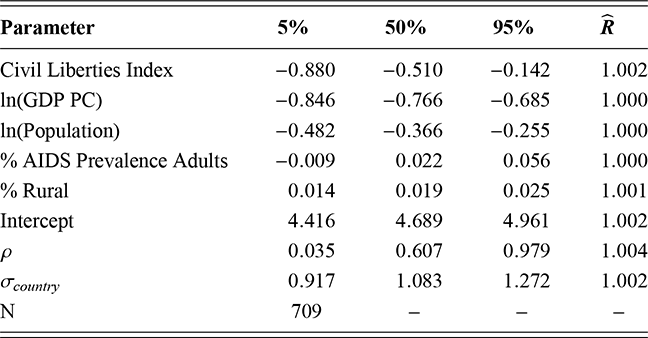

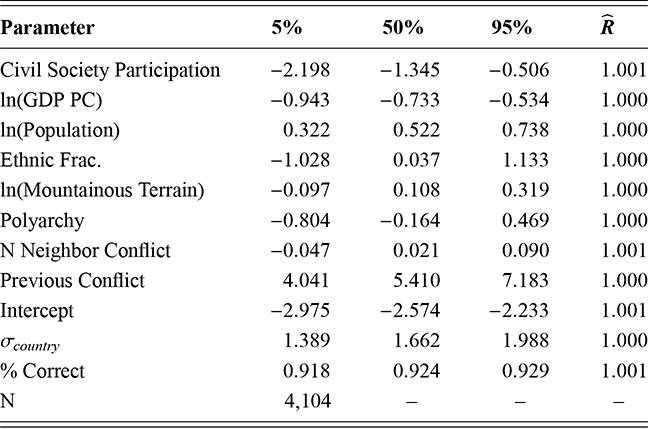

We measure women’s political empowerment using a series of variables taken from the V-Dem 13 dataset (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2023b; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt and Tzelgov2023). Model 2.1 uses the women’s Political Empowerment Index (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2023a). More equal societies will have greater values on the women’s Political Empowerment Index, while more unequal societies will have lower values. The index is composed of three separate indices–the women’s Civil Liberties Index (model 2.2), the women’s Civil Society Participation Index (model 2.3), and the women’s Political Participation Index (model 2.4) (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2023a). It is possible that the impact of these different elements of the empowerment index will have different effects on the causes and consequences of conflict; therefore, we run models using these three indices separately. Finally, in model 2.5, we include % Women in the Legislature, which measures the percentage of women in the lower chamber of the legislature (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2023a). Based on our argument, we expect each of these measures to be negatively correlated with Conflict, but positively correlated with Female Life Expectancy.

We include several control variables in our first stage. First, we control for differences in the level of economic development, using the natural log of GDP per capita, ln(GDP PC) (Bolt & van Zanden, Reference Bolt and van Zanden2020; Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg and Holmberg2023). Previous research finds that civil conflict is more common in poorer countries (Gates et al., Reference Gates, Hegre, Nygård and Strand2012; Theisen, Reference Theisen2008). Second, we include the natural log of population, ln(Population), to control for differences in population size (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg and Holmberg2023; World Bank, 2022). Civil conflict is more likely as population increases (Theisen, Reference Theisen2008). Third, we control for ethnic diversity by including a measure of ethnic fractionalization –Ethnic Frac. (Collier & Hoeffler, Reference Collier and Hoeffler2002; Fearon, Reference Fearon2003; Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg and Holmberg2023). Fourth, we include the natural log of each country’s mountainous terrain, ln(Mountain Terrain), to control for the impact of a country’s terrain on conflict (Miller, Reference Miller2022). Research shows that mountainous terrain is more favorable for rebel groups, increasing the probability of civil conflict (Bohara, Mitchell, & Nepal, Reference Bohara, Mitchell and Nepal2006; Carter, Shaver, & Wright, Reference Carter, Shaver and Wright2019; Hendrix, Reference Hendrix2011). Fifth, we code each country/year with its level of democracy based on the V-Dem Polyarchy index (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2023b; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt and Tzelgov2023). Civil conflicts are more common in less democratic countries (Theisen, Reference Theisen2008). Fourth, we measure the number of neighboring states that are experiencing conflict, N Neighbor Conflicts as well (Miller, Reference Miller2022). Previous work finds that civil conflict often spreads to neighboring countries (Fearon & Laitin, Reference Fearon and Laitin2003; Gibler & Miller, Reference Gibler and Miller2014; Nunn & Puga, Reference Nunn and Puga2012; Riley, DeGloria, & Elliot, Reference Riley, DeGloria and Elliot1999). Finally, we include a dummy variable indicating whether there was a previous conflict in the country, Previous Conflict, for each observation (Davies, Pettersson, & Öberg, Reference Davies, Pettersson and Öberg2022; Gleditsch et al., Reference Gleditsch, Wallensteen, Eriksson, Sollenberg and Strand2002).

The second stages of our models include similar control variables. First, we include controls for democracy, Polyarchy (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2023b; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt and Tzelgov2023). Regime type may impact the quality of life; therefore, it could influence life expectancy (Plümper & Neumayer, Reference Plümper and Neumayer2006). Second, we control for wealth by including the Ln(GDP PC) (Bolt & van Zanden, Reference Bolt and van Zanden2020; Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg and Holmberg2023). Those in wealthier countries have more resources and better health infrastructures; therefore, we expect female life expectancy to depend on a countries wealth (Baum & Lake, Reference Baum and Lake2003; Bergh & Nilsson, Reference Bergh and Nilsson2010; Kennelly, O’Shea, & Garvey, Reference Kennelly, O’Shea and Garvey2003; Plümper & Neumayer, Reference Plümper and Neumayer2006). Third, we control for population by including ln(Population) (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg and Holmberg2023; World Bank, 2022). The provision of health resources could be dependent upon the size of the population (Baum & Lake, Reference Baum and Lake2003). Fourth, we include the % AIDS Prevalence Adults to control for greater death rates due to HIV (UN AIDS, 2023). AIDS prevalence has been found to limit life expectancy (Plümper & Neumayer, Reference Plümper and Neumayer2006). Fifth, we code all observations with the duration of the current regime, Duration (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Knutsen2023b; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt and Tzelgov2023). More durable regimes may provide a more stable environment, improving health outcomes (Plümper & Neumayer, Reference Plümper and Neumayer2006). Sixth, we include the percentage of the population living in rural areas, % Rural Population (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg and Holmberg2023; World Bank, 2022). Urban areas often contain better health infrastructure than do rural ones (Bergh & Nilsson, Reference Bergh and Nilsson2010; Kotsadam & Østby, Reference Kotsadam and Østby2019; Torres & Urdinola, Reference Torres and Urdinola2019; Urdal & Che, Reference Urdal and Che2013). Finally, we include the rate of population growth, % Population Growth (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg and Holmberg2023; World Bank, 2022). Rapid population growth can pose a strain on state resources, potentially limiting resources for health care.

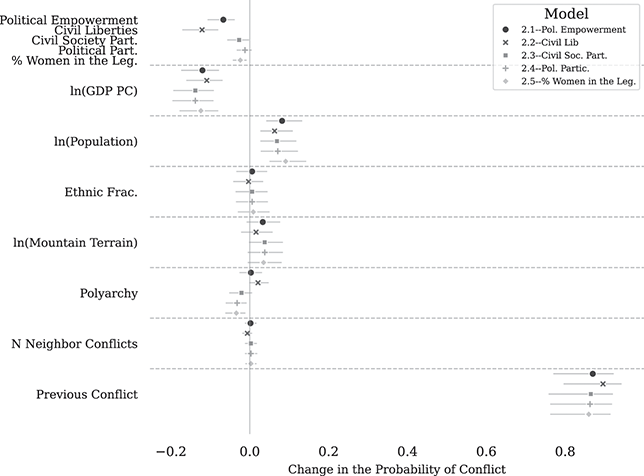

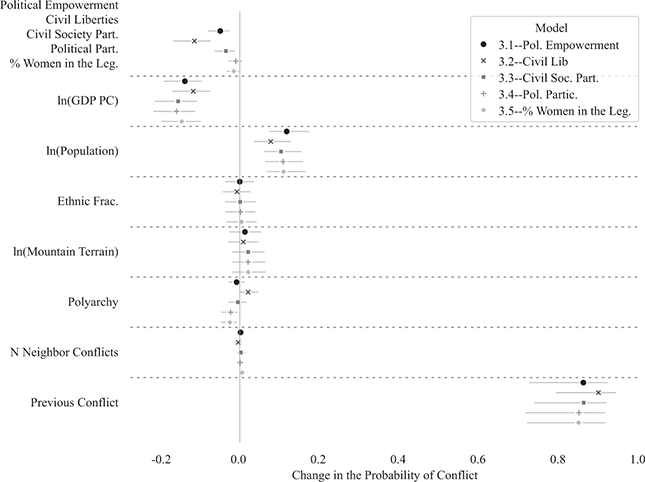

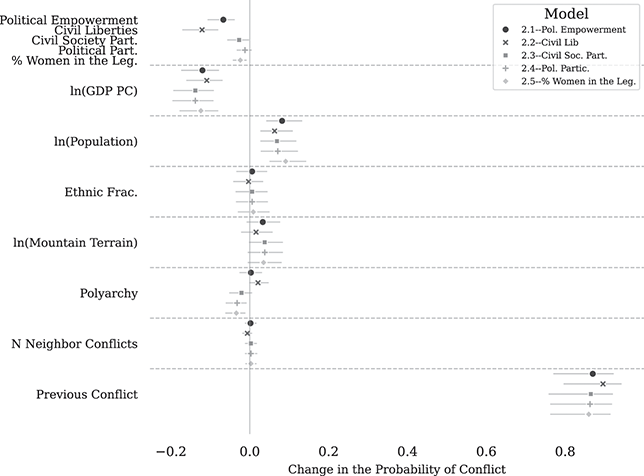

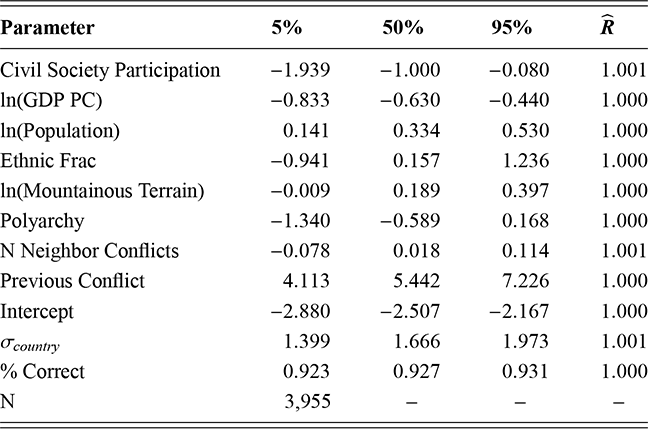

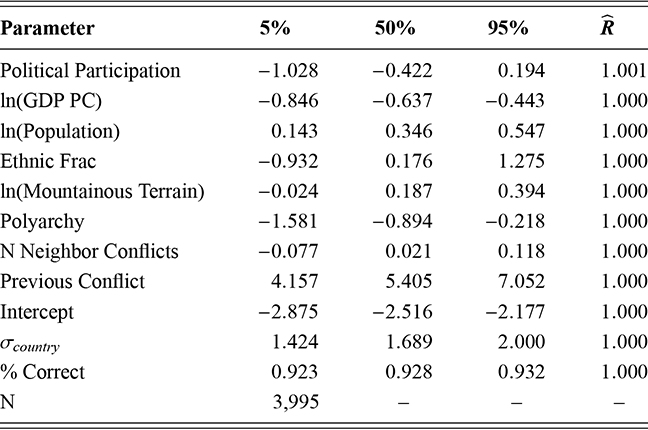

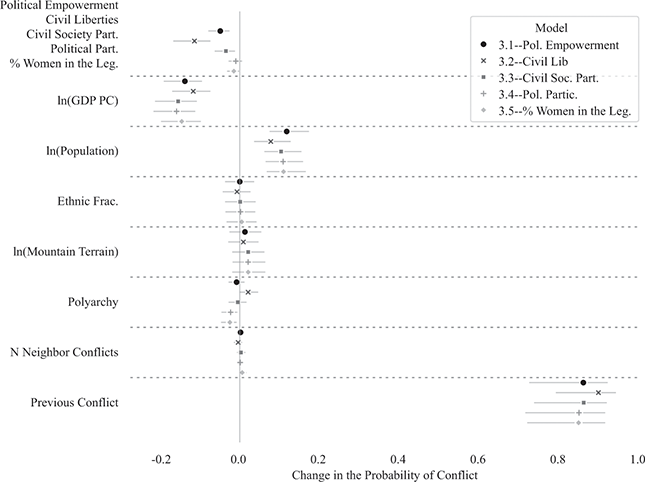

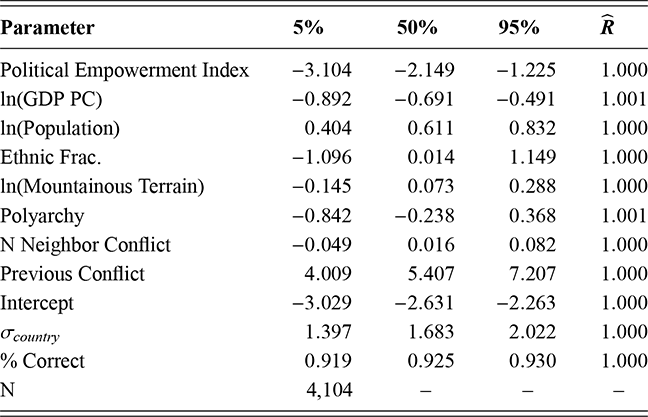

To begin our analysis, we examine the results of the first stages of our models (2.1 through 2.5) in order to test hypothesis 2.1. In Figure 3, we plot the posterior medians and 90% credibility intervals of the first differences for all covariates.Footnote 9 For continuous variables, the first differences represent the change in the probability of conflict if we increase the value of each variable from one standard deviation below its mean to one standard deviation above its mean. For dummy variables, the first differences are the change in the probability of conflict if we increase the value of the variable from 0 to 1.

Note: Posterior Medians and 90% Cr. Int.

Figure 3 Conflict first differences, models 2.1–2.5

The estimates presented in Figure 3 provide support for hypothesis 2.1 – the probability of conflict decreases as women’s political equality increases. Increasing equality on four of our five covariates (Political Empowerment Index, Civil Liberties Index, Civil Society Participation Index, and % Women in the Legislature) reduces the probability of conflict between 1.2% (% Women in the Legislature and 12.1% (Civil Liberties Index). These are significant changes in the probability of conflict. The first difference for the Political Participation Index is negatively correlated with conflict, but 0 is within the 90% credibility interval.

The control variable estimates provide interesting insights as well. As expected, increasing the value of ln(GDP PC) produces a significant decrease in the probability of conflict in all models, between 10.9% and 13.8%. It is not a surprise that civil conflict is less likely in wealthy countries. We do find that increases in ln(Population), tend to increase the probability of conflict between 6.3% and 8.2% across models 2.1 through 2.5. There is little evidence based on our models that either Ethnic Frac. or ln(Mountain Terrain) has an independent impact on the probability of conflict. The impact of democracy, as measured by Polyarchy, has conflicting results. The variable is statistically significant for models 2.3, 2.4, and, 2.5 employing the Civil Society Participation Index, Political Participation Index, and % Women in the Legislature variables. The N Neighbor Conflicts is statistically insignificant in all models. There is strong evidence that having a previous conflict increases the probability of conflict. Our estimates find that a previous conflict increases the probability of conflict in a given year by over 80% in all models.

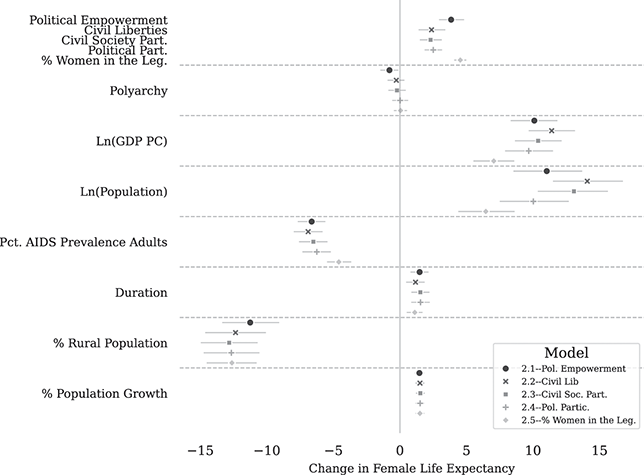

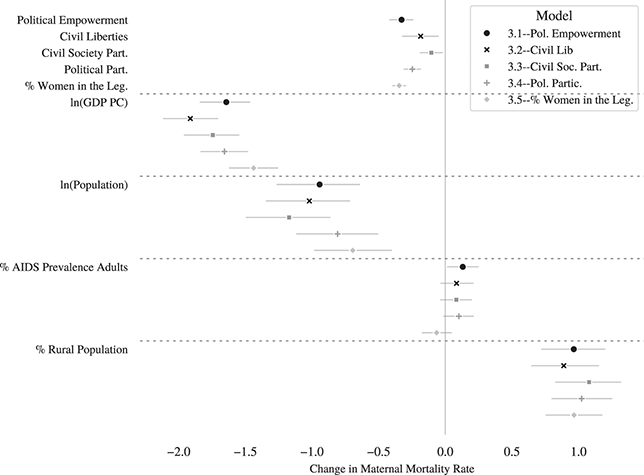

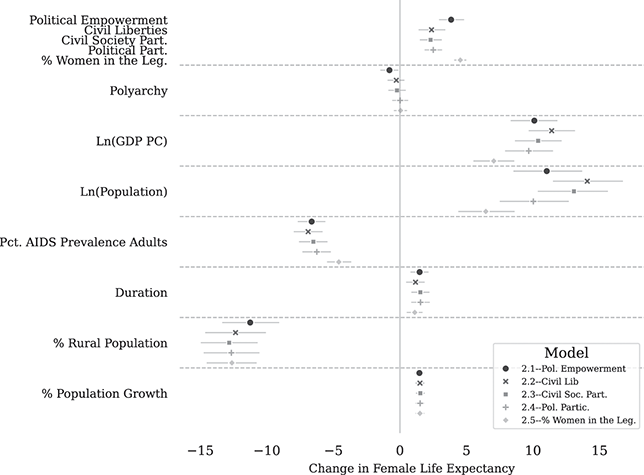

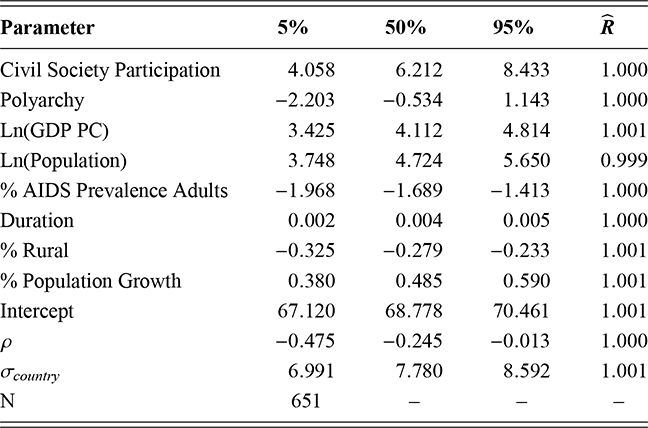

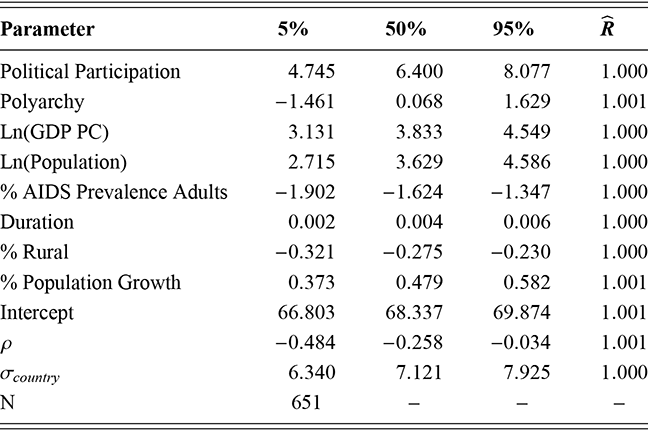

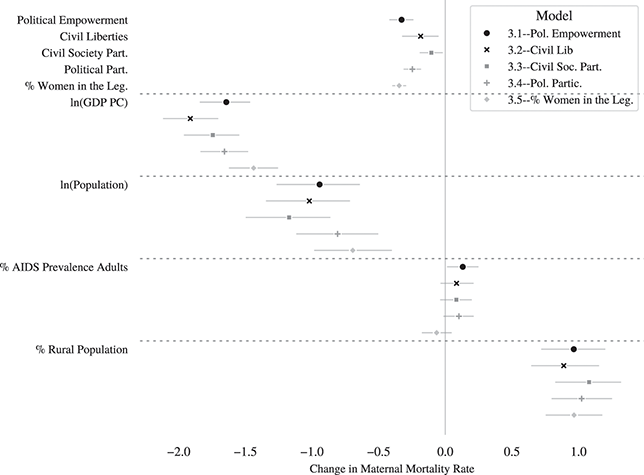

Next, we present the results of the second stages of our models, which test hypothesis 2.1. Figure 4 presents the first differences, calculated as discussed previously, of our models’ second stages using the Female Life Expectancy dependent variable. The results are clear. In all models, increases in political equality are correlated with increases in female life expectancy in countries undergoing civil conflict. Increasing each index from one standard deviation below its mean to one over increases female life expectancy by 3.8 (Political Empowerment Index), 2.4 (Civil Liberties Index), 2.3 (Civil Society Participation Index), 2.5 (Political Participation Index), and 4.5 years (% Women in the Legislature) respectively. Thus, women’s life expectancy in conflict countries was greater in those countries with greater gendered political equality than in those with weaker levels of gendered political equality. In addition, these findings are robust to selection effects.

Note: Posterior Medians and 90% Cr. Int.

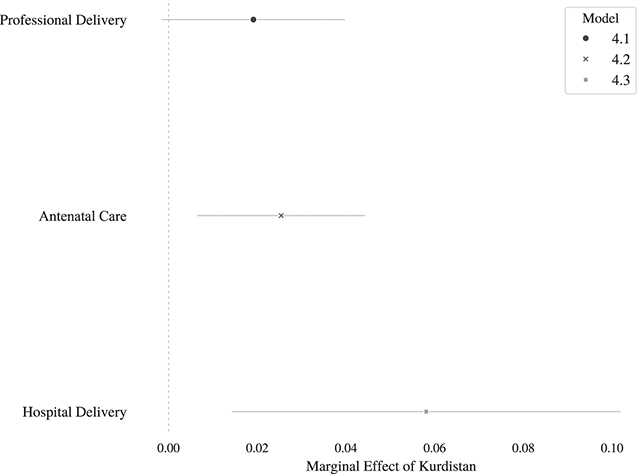

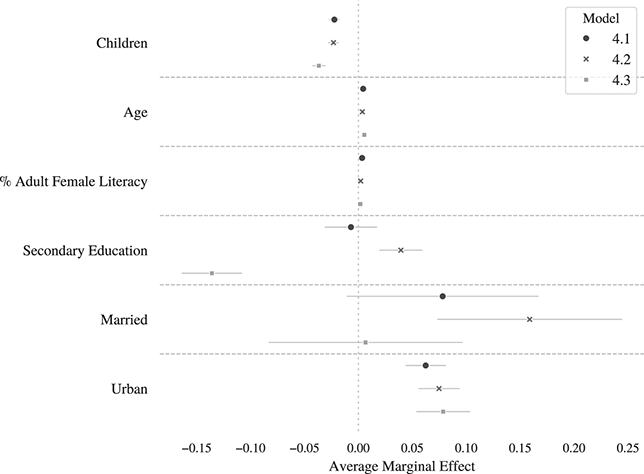

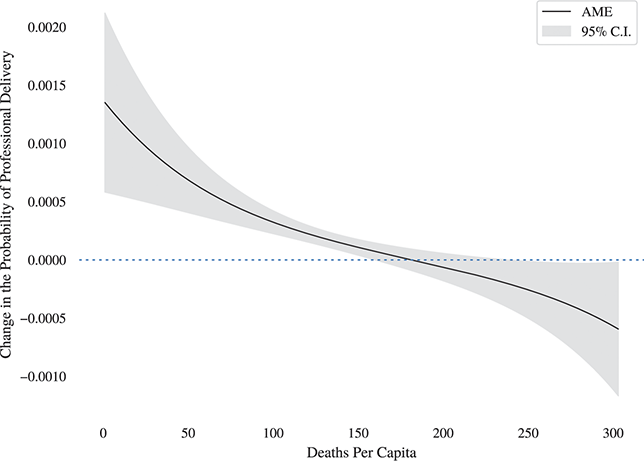

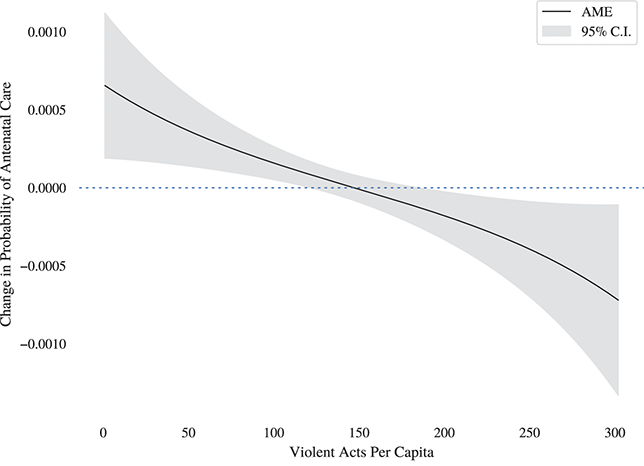

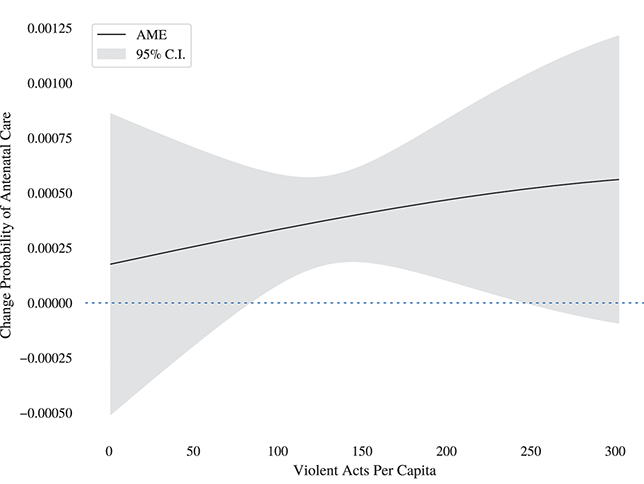

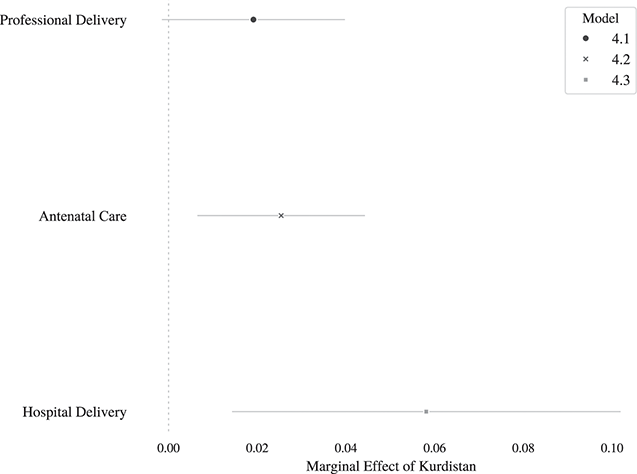

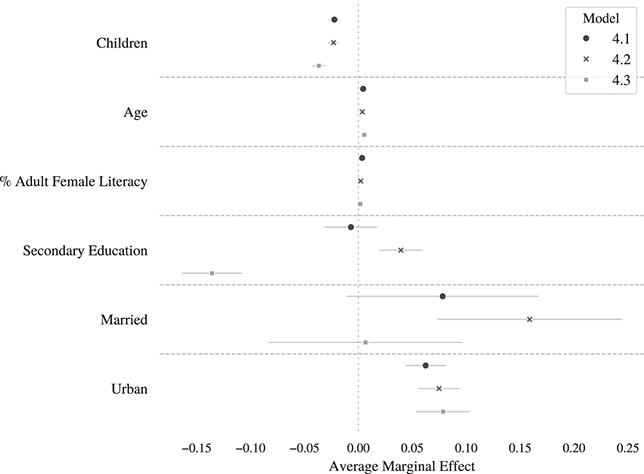

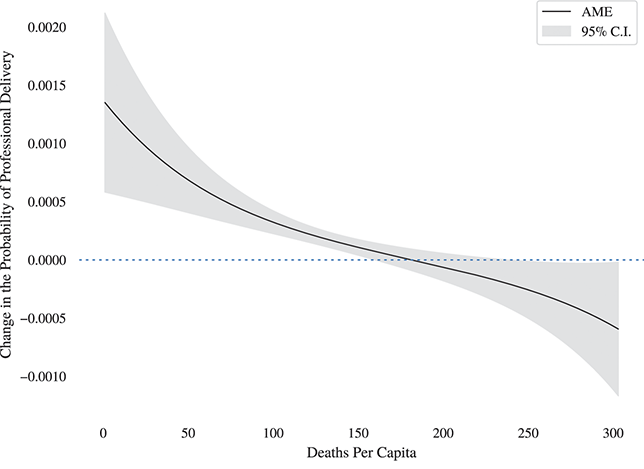

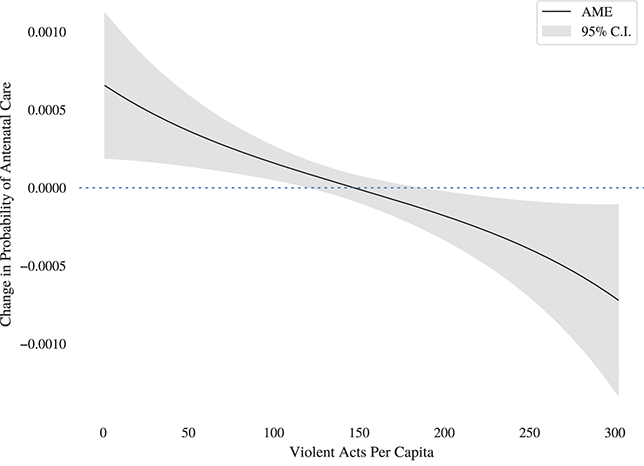

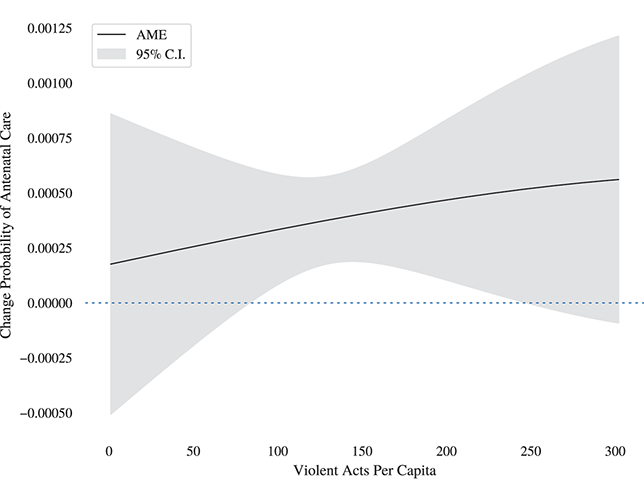

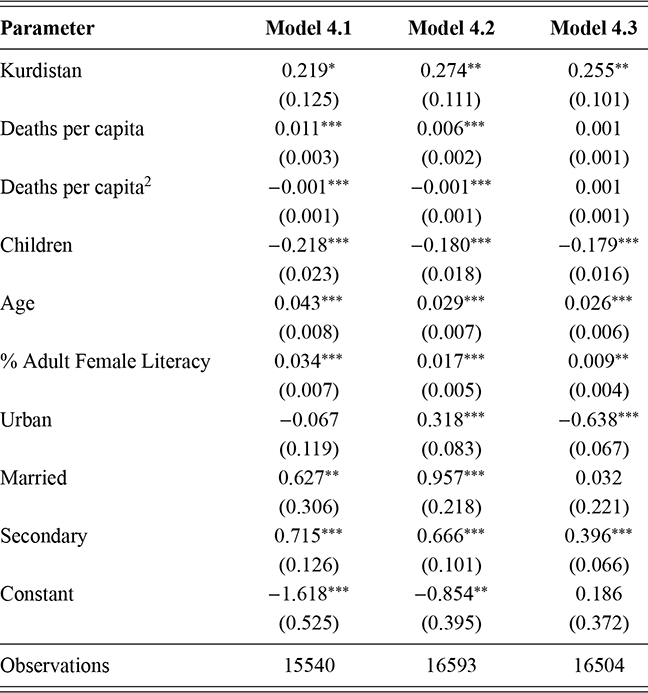

Figure 4 Female life expectancy first differences, models 2.1–2.5