Issues in national politics in 2013

Although countries had succeeded by 2013 in putting economic crisis behind them, others continued to struggle with austerity, high unemployment and cumbersome debt. While the economy remained a dominant theme of the year, it was certainly not the only one. Some countries turned their attention to cultural issues such as gay marriage and women's rights, while others tried to tackle the endemic problem of corruption. There was a new round of scandals, and a growing indication of widespread disillusionment with politics. In several countries, voters rejected seasoned politicians in favour of nonpartisan experts, and in some countries, frustration with politics spilled over into violence. On the international scene, the credibility of the Eurozone remained weakened by a series of bail-outs, the crisis in Syria created domestic tensions concerning refugees, and the documents leaked by Edward Snowden about the United States National Security Agency turned into an international diplomatic row.

The economy

For some countries, the economic woes of the preceding years were starting to become a thing of the past by 2013. A few states emerged relatively unscathed, such as Israel, Malta, New Zealand, Norway and Sweden. Others, such as the United Kingdom and Japan, began to get back on track. Italy's progress was commended internationally, although domestically the lingering effects of the recession were still keenly felt. Perhaps most encouraging were the signs that three of the countries that had fared most badly during the recession and had needed international intervention were now beginning to recover. Greece, although not yet out of the woods, managed to reduce its deficit dramatically, and produced a primary surplus for the first time since 2002, even though it remained in recession and faced an ongoing unemployment rate of 28 per cent. Drastic austerity measures caused great resentment and resistance among the Greek people, but the troika of the International Monetary Fund, European Central Bank and European Commission expressed confidence that their intervention was starting to work. The same could be said for Ireland – another country that had been bailed out by the troika and was now starting to recover. Ireland's gross domestic product (GDP) remained flat, but its gross national product rose and unemployment fell, offering some grounds for future optimism. Meanwhile, Portugal continued to struggle in 2013, but things began to improve towards the end of the year. Deficit and debt remained too high, and unemployment grew for much of the year, but it started to come down in the final quarter. Other signs of recovery at the end of 2013 led Portugal to hope to be rid of the troika by mid-2014.

Not everyone was feeling so hopeful, however. The Austrian government struggled to defend its management of an economy that was comparatively strong, but very weak by Austrian standards, with banks requiring a government bail-out and unemployment at a near-record high. Belgium likewise struggled with bankruptcies and high unemployment. Cyprus joined the ranks of several other European countries bailed out by the troika following the impending bankruptcy of its banks. Its economy shrank (although by less than expected) and unemployment went up. Unemployment was also a problem for Denmark, which fared less well than its Scandinavian neighbours. The government tried to get the country back on track by curbing spending and cutting taxes. Slovenia's economy actually worsened in 2013, with GDP continuing to go down while unemployment rose further. Meanwhile, France decided to change direction as ongoing stagnant growth and record levels of unemployment caused the government to reconsider its strategy of growth promotion and join its European neighbours in adopting policies of austerity.

For countries where austerity was still the name of the game in 2013, the sacrifices were many and painful. Belgium, Cyprus, Greece, Latvia, the Netherlands and Portugal all struggled with painful cuts to areas such as health care, development and the civil service, alongside some privatisations. The acute crisis in Slovenia led to international pressure to impose austerity, but Slovenians tried to stop short of the deep cuts undertaken in some of their European neighbours. Ireland and Lithuania began to ease the austerity measures as their economies began to recover.

In the midst of budget cuts, shrinking public sectors and high unemployment, many states had to grapple with containing their welfare states. Denmark, the Netherlands and Portugal all sought to constrain spending on unemployment benefit through reducing entitlement. Belgium, Finland and Portugal tried to rein in spending on health care, while the United States faced a serious of administrative blunders in trying to get their own public health care scheme (‘Obamacare’) up and running. The Netherlands and Portugal also tried to curb spending on pensions, while efforts in Finland to raise the retirement age were met with resistance. Pension crises were also linked to ageing populations (a particular problem for Japan), and Latvia introduced measures to try and increase the birth rate.

Cultural politics

Given the severe budgetary constraints on policy making, it is perhaps not surprising that some states chose to divert attention away from expensive policies and towards a symbolic policy with very few financial implications – namely, gay marriage. Interestingly, this issue has been used to divert attention away from economic problems by governments supporting same-sex unions as well as those opposing them. In France, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, gay marriage was legalised in 2013. In the United Kingdom, the law created internal division within the governing Conservative Party, seen by hard-line right-wingers as an unwelcome attempt by the prime minister to appear liberal. The law was also not supported universally by the government's junior coalition partner, the Liberal Democrats, despite the party's announced preference for liberal principles. In France, analogous legislation was widely supported by the governing party but – unlike in the United Kingdom – attracted widespread and vocal public protest via a highly mobilised campaign. New Zealand offered perhaps the most peaceful transition of gay marriage into law. In Malta, the newly elected government promised gay marriage as part of its election campaign, but still faced some resistance once it attempted to come good on this promise. In the United States, where opposition to gay marriage had previously been part of the Republican Party strategy to boost right-wing turnout at elections, several shifts worked in favour of the legalisation of gay marriage: Barack Obama mentioned gay rights in his State of the Union speech, and the Supreme Court's ruling on the Defence of Marriage Act led to federal-level recognition of gay marriage but allowed states to make their own decisions. Meanwhile, Croatia moved in the opposite direction, with a successful referendum enacting a constitutional amendment banning gay marriage and adoption.

Just as 2013 offered a mixed bag for gay rights, so it did too for gender equality. In Slovenia, Alenka Bratušek became the country's first female prime minister after her male predecessor was ousted in a corruption scandal (and Sibel Siber became the first female prime minister of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, though she held the post only for three months as the head of a caretaker government pending elections). In Australia, however, female prime minister, Julia Gillard, was ousted by her party in favour of a male rival. In Hungary, domestic violence became enshrined in the penal code as a separate offence following mobilisation by women's groups and by women within the parliamentary majority, although a male MP from the same party made offensive comments on the issue. In Ireland, a woman died from pregnancy-related complications after being refused an abortion, resulting in a change to legislation to permit abortion when the mother's life is at risk, although the law remains ineffective. Finally, Austria and Switzerland held remarkably similar referendums, each proposing to replace compulsory male military conscription with voluntary military service open to both sexes. Majorities in both countries rejected the referendum in favour of the status quo.

Anti-politics and corruption

One of the more worrying trends in 2013 was a widespread rejection of politics. Antipathy towards politicians was fuelled by disillusionment with years of austerity and deeply entrenched social problems as well as numerous scandals and widespread corruption. Problems with corruption appear prominently in no fewer than 11 Yearbook chapters (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Malta, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain). Romania and Spain reinforced their efforts to tackle corruption, while corruption has led to growing public protest in Bulgaria and Slovenia, but in Slovakia the public protest against corruption subsided. Other scandals also peppered the year, ranging from the disgraced mayor of Toronto, Rob Ford in Canada, to the sentencing of Silvio Berlusconi in Italy. Senior politicians in both Croatia and Germany were forced to resign after accusations of having plagiarised their PhD theses. Scandals relating to financial misconduct plagued both France and the United Kingdom, with several British politicians also facing allegations of sexual misconduct.

Citizens expressed their discontent in numerous forms ranging from abstention to violence. Voters shunned the polls in Bulgaria, and the newly elected government was at pains to emphasise its expert, nonpartisan nature. This was a recurring theme, with a growing preference for electing people with expertise in domains outside the political realm, rather than electing politicians who were seen as self-serving, incompetent and corrupt. In the Czech Republic, one of the major contenders in the presidential election ran as a nonpartisan candidate, and widespread dissatisfaction with political parties due to endemic corruption brought success for new parties that were untainted by scandal. One party, named ‘Action of Dissatisfied Citizens’ (ANO), offered the slogan ‘we are not politicians – we work’. In Italy, ‘anti-politics’ was the theme of the campaign, and support for politics and parties was at an all-time low, while in Australia, the support for mainstream parties continued to decline. Luxembourg used non-elected experts from the financial sector to reassure the markets, while there was an (unsuccessful) attempt in Poland to replace the partisan government with a nonpartisan expert government led by an academic.

Retaliation also took angrier forms. Bulgaria witnessed 194 days of continuous protest, while the Greeks went on strike yet again in protest against deep cuts. In Belgium, France and the United Kingdom, rising dissatisfaction with mainstream politics led to growing support for the far-right. Nationalism and xenophobia were also on the rise in Finland, including in parties outside the far-right. Slovakia elected a far-right anti-Roma candidate in its regional elections. There were also several incidences of political violence. In Portugal, the protests against austerity were fewer in number than in 2012, but more violent in nature. In Sweden, there were riots in Stockholm following a fatal police shooting, as well as eruptions of violence between racist and anti-racist groups. In the United States, the Boston Marathon ended tragically when two bombs exploded, killing several people and injuring many more. Greece also experienced several bomb explosions and other incidents of political violence that included the dousing of security guards with petrol, the murder of a left-wing activist by a Golden Dawn cadre, and the murder of two members of Golden Dawn (and the serious injury of a third) by a new terrorist organisation. The global economic crisis has thus caused or exacerbated domestic tensions that may continue to pose problems even once the worst of the crisis is over.

International contention and cohesion

Other international crises with domestic repercussions included Syria and the National Security Agency (NSA) scandal. Bulgaria and Malta both struggled to accept large influxes of refugees from Syria, while the British government experienced a rare and humiliating defeat on a foreign policy issue after taking a vote on humanitarian intervention in Syria. Meanwhile, the documents leaked by Edward Snowden regarding bugging by the NSA led to a domestic uproar that soon went global after it emerged that the NSA was also spying on people in other countries. The Germans were particularly affronted after it emerged that the NSA had even tapped Angela Merkel's telephone.

Despite economic woes, international tensions, a weakened political mainstream, rising support for far-right parties and sporadic outbreaks of political violence, there was no indication that the countries included in the Yearbook were set to repeat the conflict and political tragedies of the 1930s. In fact, one of the quiet surprises of the year was that the Eurozone remained perfectly intact. Growing euroscepticism, both in established states and in acceding and candidate countries such as Croatia and Latvia, was voiced primarily at the popular (and populist) level. At the elite level, the benefits of ongoing union are still perceived to outweigh the costs. For all the difficulties of recent years, the overall picture is one of a Europe that remains (more or less) unified and on the cusp of economic recovery, alongside its allies around the world.

Changes in the composition of parliaments and cabinets

Voter dissatisfaction with political parties and politicians that manifested itself in protests and demonstrations during 2013 also shaped the outcomes of the year's parliamentary elections. In most cases, incumbents took severe beatings, new parties continued to pose a challenge to established ones and voter turnout tended to decline. Radical right and other xenophobic parties, however, did not manage to take advantage of this favourable situation and generally did badly in most countries.

Eleven of the Yearbook countries held parliamentary elections during 2013. In only two countries (Bulgaria and the Czech Republic) did these elections occur significantly outside of the normal election cycle – a share of early elections that was much lower than recent years. Although most elections occurred at the scheduled time, they did not necessarily reinforce the status quo: eight of the 11 elections produced significant changes in government composition. In Luxembourg, the CSV, who have headed all but one government since 1945, had to leave the ruling coalition together with LSDA and were replaced by the Green Party and the Democratic Party (which had not been in office since 1979, but that now gained the office of prime minister). In Bulgaria, Iceland, Norway, Malta, the Czech Republic and Australia, the turnover was more or less total, with only some minor parties remaining in the governments in some of the countries, while Berlusconi's PDL was reduced to a junior coalition partner in Italy. In Germany and Austria, the elections resulted in grand coalitions between the two biggest parties. In Germany, CDU/CSU opted for a coalition with SPD when its former coalition partner the Christian Democrats (FPD) failed to win representation in parliament; in Austria, coalition cooperation continued between SPÖ and ÖVP, although both parties obtained their worst results since 1945 and only barely managed to secure a majority in parliament. Finally, in Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu continued as prime minister, even though his Likud Party lost 10 percentage points compared to the previous election.

With the exception of Germany's CDU/CSU, incumbent parties were heavily punished by the voters, regardless of their ideological orientation. It is therefore difficult to identify any left-wing or right-wing trends during 2013. In Israel, the largest right-wing government retained control over the cabinet but with a different coalition configuration. In Iceland, Norway and Australia, the right-wing opposition defeated the left-wing incumbents. In Bulgaria, Malta and the Czech Republic, the opposite was true: the left-wing opposition defeated the right-of-centre governments. In Italy, the outcome was rather left-oriented as PD assumed the leading role in the coalition, but the real and perhaps only winner was the anti-establishment party M5S, led by comedian Beppe Grillo. In Luxembourg, the power gravitated towards the centre as the liberal DP replaced and took over the Christian Democrats' function in the government coalition.

Dissatisfaction did not translate directly into changes in participation. Voter turnout increased in four of the countries including Luxembourg, which has compulsory voting, where turnout increased from 85 to 91 per cent, and Israel, which saw an increase by three percentage points to almost 68 per cent. In six countries the turnout decreased, however – most dramatically so in Bulgaria, where it went from 60 to 51 per cent, and in Italy and Austria, where it dropped from about 80 to around 75 per cent. Other counties saw less dramatic ups and downs in turnout rates, and in Australia, which also has compulsory voting, it remained identical.

Another indication of voter dissatisfaction is the extent to which anti-establishment parties, either old or new, increased their support. In terms of new party success, 2013 witnessed the continuation of a trend that has been visible for some time now – namely substantial inroads for such parties. Most spectacular was naturally the success of the above-mentioned Five Star Movement in Italy, which became the largest party in terms of votes (although far behind in terms of seats), winning 25.6 per cent. In Israel, journalist and television celebrity Yair Lapid led Yesh Atid to 14.3 per cent of the vote and a role in the cabinet. In the Czech Republic, billionaire businessman Andrej Babiš's party, ANO 2011, attracted 18.7 per cent of the votes and a significant role in the Czech government, and another new party, Dawn of Direct Democracy, took 6.9 per cent of the votes. In the usually quite stable Austria, two new parties managed to win parliamentary representation: 5.7 per cent to Team Stronach, named after its founder, businessman Frank Stronach, and 5.0 per cent to the liberal NEOS. Iceland also saw the success of two new parties: socially liberal Bright Future (8.2 per cent) and the Pirate Party (5.1 per cent). New parties did not enter government in either Austria or Iceland. In Australia, businessman and politician Clive Palmer secured 4 per cent of the votes and a single parliamentary seat with his newly established Palmer United Party. Finally, new parties came close to winning seats in both Germany and Bulgaria.

With these new party successes came severe shocks to several previously successful parties. Between 2009 and 2013 Germany's FDP dropped from its highest-ever support level of 14.6 per cent to its lowest level of 4.8 per cent. The Civic Democratic Party (ODS) in the Czech Republic experienced a similar drop from 20.2 to 7.7 per cent, and in Italy, Berlusconi's PDL fell from 37.2 to 21.4 per cent. The list of those suffering rapid collapse also included several parties that had previously experienced rapid gains: Kadima in Israel lost 90 per cent of its support, falling from 22.5 to 2.1 per cent; in Austria the radical right BZÖ collapsed from 10.7 to only 3.6 per cent and lost its entire parliamentary delegation; and in the Czech Republic, corruption allegations and internal divisions meant that Public Affairs did not even contest the election.

Despite the high electoral volatility and strong support for new parties, few radical right parties did well during the year. In Bulgaria, Ataka lost 2 percentage points, winning 7.3 per cent (although it gained two seats). In Austria, the collapse of BZÖ, who lost 7 percentage points, did not benefit FPÖ, which gained only 3 percentage points. In Italy, Lega Nord lost half its support, winning a meagre 4 per cent. Even in Norway, where the Progress Party (which may not even be considered to belong to this category) finally made it into the government for the first time, their vote share fell quite substantially by almost 7 percentage points to 16.3 per cent. No radical right party managed to win representation in any of the other 2013 elections, and the only relative success on the far left was the Communist Party in the Czech Republic which rose by 4 percentage points to almost 15 per cent. It is thus safe to say that although deeply dissatisfied, the voters mainly shunned parties on the far ends of the ideological spectrum.

Finally, in terms of female parliamentary representation, 2013 was a positive year, witnessing increases in eight countries (Germany, Israel, Malta, Austria, Australia, Luxembourg, Bulgaria and Italy), status quo in two (Iceland and Norway) and decreases in only one (the Czech Republic). The most impressive gains in terms of percentage points were made in Italy, which went from 21 to 31 per cent; Luxembourg, which went from 22 to 28 per cent; and Malta, which rose by more than half from a low base of 9 per cent to over 14 per cent. Malta's shift in 2013 left only two countries with a share of women in parliament below 10 per cent: Hungary (9 per cent) and Japan (8 per cent).

Changes in parliamentary composition also occurred because of death and resignation. In the full set of 37 Yearbook countries, women's representation rose in 24, remained the same in ten and decreased only in three (the Czech Republic, Estonia and France), and in no case did the decrease exceed 2.5 percentage points. Sweden still tops the list with 45 per cent women, followed by Finland and Belgium which are both above the 40 per cent level. Nine countries are below the 20 per cent mark. Looking over a wider time perspective, the increases are striking. All but five countries have increased women's representation over the last ten years, and in many the increase has been greater than 10 percentage points. Slovenia and Italy are the most exceptional cases: representation of women went from just over 10 per cent in 2004 to over 30 per cent in 2013.

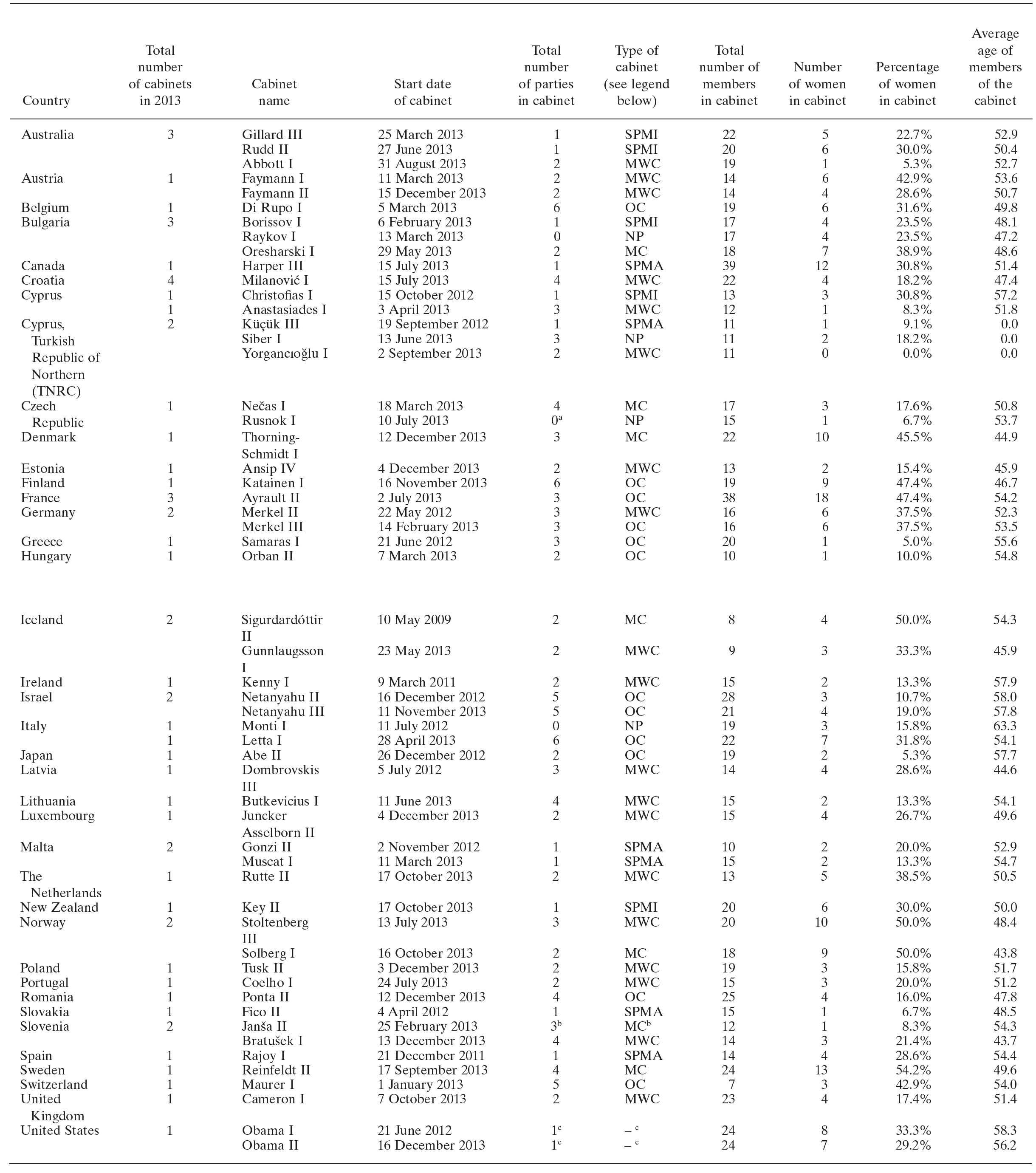

Perhaps the biggest change in overall cabinet statistics in 2013 concerned the representation of women. The data for 2013 in Table 1 show a nearly three percentage point increase in the share of female government ministers to 26 per cent – the highest level ever recorded for the Yearbook countries. The changes were not uniform, however, and the new government in Australia was strikingly male in its composition, with only one woman out of 19 members. Meanwhile, the new government of Cyprus had no women whatsoever for two months until a male minister resigned and a woman was appointed in his stead.

Table 1. Number of parties in cabinet, type of cabinet and gender and average age of cabinet members on 31 December 2013 (or last day in office for cabinets ending during 2013)

Legend: SPMA = single-party majority; SPMI = single-party minority; MWC = minimum winning coalition; MC = minority coalition; OC = oversized coalition; NP = nonpartisan.

Notes:

a Although the Rusnok I government in the Czech Republic was nominally nonpartisan, one member retained his party membership in the Christian Democratic Union and others maintained close, but non-official ties to the Social Democratic Party. b The Janša II government in Slovenia began the year as a MWC with five parties but lost support of two parties during the early months of 2013 and lost majority support for a brief period before a parliamentary vote of no-confidence. c The presidential system of the United States does not fit easily into categories used in the Yearbook. The Obama I government included two members of the opposition Republican Party. The Obama II government included one Republican.

The average age of government ministers also dropped by more than half a year between 2012 and 2013 to just under 52, but remained quite consistent with past results. The average has not fallen below 50 years or exceeded 53 years in over twenty years.

The Minimum Winning Coalition increased its lead over other government arrangements (rising from 31 to 40 per cent, largely at the expense of Oversized Coalitions) but overall configurations remained stable. As in previous years, approximately 70 per cent of governments maintained a parliamentary majority (some could count on independents and others for a reliable majority), and about 75 per cent of all governments were multiparty coalitions.

The format of the Yearbook

The Yearbook includes 37 countries and covers the period from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2013. New to the Yearbook is Croatia, which entered the European Union on 1 July 2013.

As in the earlier editions, each country report is broken down into a number of sections, with an emphasis on the inclusion of comparable, systematic data. To enhance the cohesion of the Yearbook and the comparability of each report, we have introduced a new template to which we have asked all authors to adhere. The template makes the Yearbook more user-friendly, and simplifies comparisons across countries and over time. In 2013, reports now start with an introduction, which provides a short summary of the key developments of the year. The remainder of the report is then broken down into sections reporting on elections, cabinets, parliaments, national issues, referendums and institutional changes. Except on rare occasions where categories do not fit country-level idiosyncrasies, each report follows a common overall framework:

-

• Introduction

-

• Election report

-

∘ Parliamentary elections

-

∘ Presidential elections

-

∘ European elections

-

∘ Subnational elections

-

∘ National initiatives and referendums

-

-

• Cabinet report

-

• Parliament report

-

• Institutional changes

-

• Issues in national politics

The absence of a heading simply indicates the lack of relevance of that particular topic in a given year. In any given year, for example, it is likely that only a minority of countries will have held general elections or national referendums or have undergone major institutional changes, and elections to the European Parliament obviously only occur in the Member States of the European Union. In addition to yearly updates of cabinet and parliament composition, country reports conclude with a section on issues in national politics, but discussions of these issues may also appear earlier in discussions of elections and cabinet formation.

As part of our transition to the online interactive database of the Political Data Yearbook: Interactive (www.politicaldatayearbook.com), we have standardised data tables for elections and cabinets. We have introduced a new table to track the party affiliation and gender of members of parliament, and many country reports also include a new table on significant changes within the party system and party leadership that will become standard in next year's Yearbook

Relevant data under the more ‘variable’ headings, on the other hand (i.e., under those headings that are not necessarily relevant to each country), are reported for the following countries:

General elections to the lower house of parliament:

Australia, Austria, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Germany, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta and Norway (and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus)

Australia, Austria, Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, United Kingdom

Elections or systematic changes to the upper house of parliament:

Cyprus, Czech Republic

Presidential elections (direct elections only):

Croatia

Elections to the European Parliament:

Australia, Austria, Canada, Germany, Switzerland

Land, cantonal, state elections (federal countries only):

Australia, Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Germany, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Norway, Slovenia, United States (and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus)

New and returning cabinets:

Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Ireland, New Zealand, Switzerland

Results of national referenda:

Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Slovenia, Spain, United States

Institutional changes:

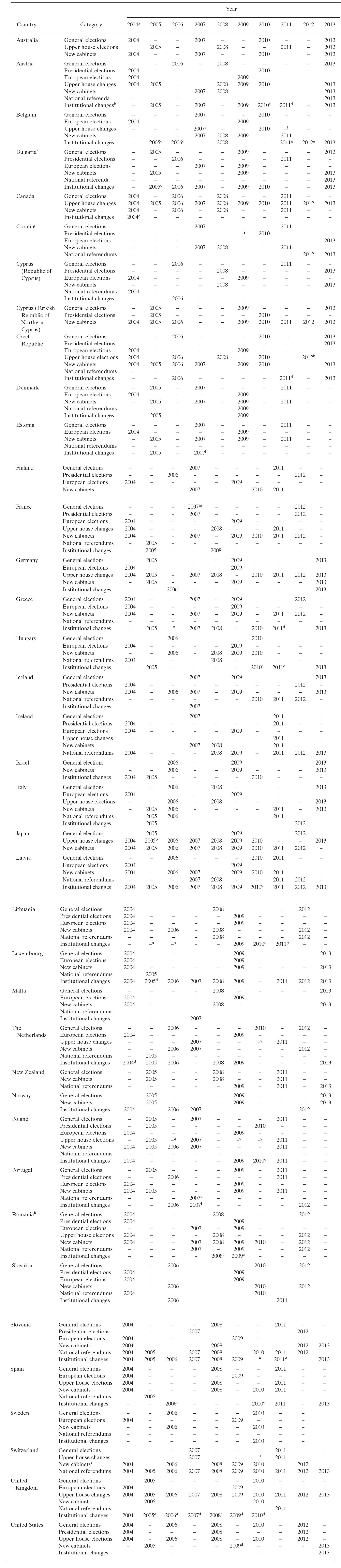

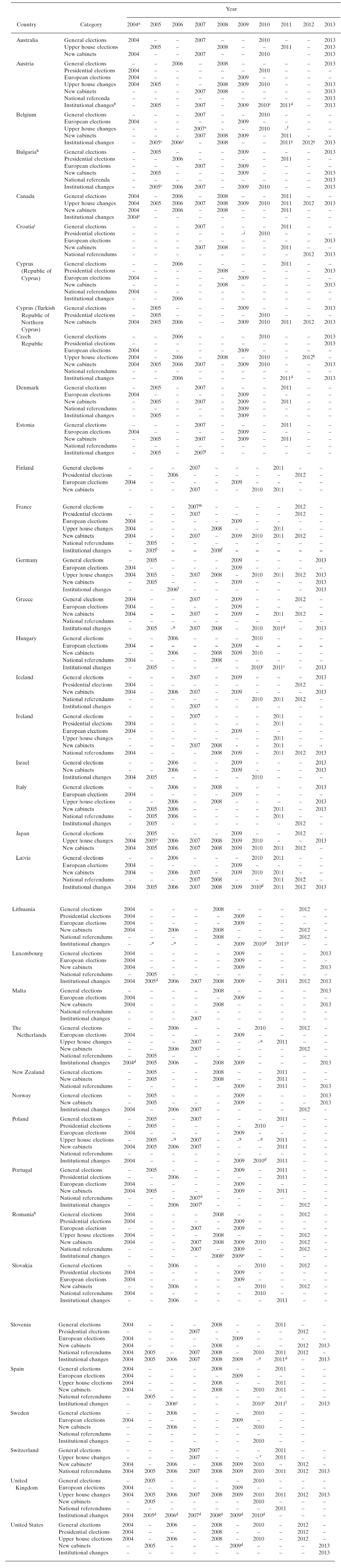

Table 2 is a cumulative index listing each major category of a formal political change in a consistent timeline for each country, which allows both a sense of the confluence of events and a sense of the kinds of formal change that a country may face.

Table 2. Cumulative index of political events

Notes:

aFor a cumulative index 1991–2001, see Katz and Koole (Reference Katz and Koole2002: 890–895). For a cumulative index 2003–2012, see Bågenholm et al. (2013: 14–19). bUnless otherwise specified, listings for ‘Institutional change’ relate to the inclusion of this formal category or a similar category within the country chapter. In some cases, authors list significant institutional changes within other categories and mark these cases with appropriate footnotes. cListed in the cumulative index in Caramani et al. (Reference Caramani, Deegan-Krause and Murray2012: 3:23) as ‘Institutional change’, but listed changes are not included under a separate formal heading within the country chapter. dNot mentioned in the cumulative index in Caramani et al. (Reference Caramani, Deegan-Krause and Murray2012: 3:23). eNot mentioned in the cumulative index in Biezen and Katz (Reference van Biezen and Katz2004, Reference van Biezen and Katz2005, Reference van Biezen and Katz2006). fCaramani et al. (Reference Caramani, Deegan-Krause and Murray2012: 3:23) lists minor changes linked to cabinet formation (Di Rupo I, 6 December 2011) after the very long ‘transition’ cabinet (Leterme II). gMajor institutional changes agreed on in 2011 but not implemented until 2012. hFirst included in the Political Data Yearbook in 2007. I First included in the Political Data Yearbook in 2013 but record of elections and governments is provided for previous years. jThe two rounds of the Croatian presidential elections spanned 2009–2010. kNot listed in 2013 Political Data Yearbook table. lInstitutional change listed under alternative heading (including ‘Constitutional amendment’, ‘Constitutional reform’, ‘Institutional reform’ and ‘Reform programme’). mNot mentioned in the cumulative index in Bale and Biezen (Reference Bale and van Biezen2008). nListed in Caramani et al. (Reference Caramani, Deegan-Krause and Murray2012: 3:23) because country chapter includes heading for ‘Institutional change’ related to changes that did not gain formal approval during the period in question. oNot mentioned in the cumulative index in Biezen and Katz (Reference van Biezen and Katz2006). pCaramani et al. (Reference Caramani, Deegan-Krause and Murray2012: 3:23) inadvertently locates its reference to 2011 ‘Institutional changes’ in the category for ‘Upper house changes’. qCaramani et al. (Reference Caramani, Deegan-Krause and Murray2012: 3:23) refers to minor changes occurring outside the normal cycle of upper house changes. rPrevious editions of the Political Data Yearbook inadvertently list Switzerland's upper house elections in 2010 rather than the correct date of 2007. sSwitzerland's Federal Council includes seven members elected for four-year terms, but not simultaneously. Dates listed here correspond to years in which new Federal Councillors took office.