Introduction

The year 2022 was marked by a sequence of numerous unprecedented crises, keeping Swiss politics on its toes. In the year's early weeks, the Federal Council announced to gradually phase out most COVID-19 protective measures. Mask requirements in numerous public venues (e.g., shops, restaurants), access limitations regulated by the COVID-19 certificate, and permit requirements for large-scale events, as well as restrictions on private gatherings, were abolished as early as 17 February 2022. By 1 April 2022, also the two remaining measures were eased (i.e., compulsory masks on public transport and in healthcare facilities, five-day isolation requirement). However, the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered yet another series of crises. First, it fundamentally challenged Switzerland's neutrality—a traditional pillar of Swiss identity. The initial wavering on whether it was joining the EU sanctions over neutrality concerns led to fierce criticism at home and abroad. Second, the Russian attack caused the largest influx of refugees since World War II, with around 75,000 people arriving from Ukraine. Switzerland granted them “protection status S,” allowing them to work and lead as normal a life as possible. Third, in summer and autumn, the federal government responded to the looming energy crisis with the launch of a campaign calling on people to save energy as shortages were expected. All in all, the many crises Switzerland faced in 2022 were addressed in a typically Swiss-style “muddling-through” fashion: A political elite that is deliberatively trying to reconcile international and time pressure(s) with the constraints caused by a “retarding,” consensus-seeking domestic political system.

Election report

Parliamentary and presidential elections

At the national level, no parliamentary elections were held in Switzerland in 2022.

The President and the Vice-President of the Swiss Confederation, in turn, are elected annually in a joint proceeding of the two chambers of the Swiss federal Parliament (United Federal Assembly). In Swiss-style consociationalism, presidential elections are not competitive at all, and there is an “unwritten rule” that Federal Councillors are elected to the said positions in order of seniority. On 7 December 2022, the outgoing Vice-President of the year 2022, Alain Berset (Social Democrats [SPS/PSS]), Federal Councillor and Head of the Federal Department of Home Affairs, was thus chosen President of the Swiss Confederation for 2023. He received 140 votes (56.9 per cent), well below the 190 Members of Parliaments (MPs; 77.2 per cent) who endorsed him in 2018 when he took on the rotating role of Swiss President for the first time. The result also clearly undercut the average share of some 71 per cent of the votes the elected post-2000 Swiss presidents usually obtained (Vatter Reference Vatter2020: 394). Whereas Alain Berset has repeatedly come out on top in approval ratings, he received negative headlines throughout 2022, which obviously made themselves felt on Election Day. It should be kept in mind that Switzerland is the only country in the world whose federal government works according to the constitutionally enshrined “principle of collegiality.” The seven members of the Federal Council each have equal rights, that is, the President is but primus inter pares (first among equals) in order to ensure that no single person can concentrate too much power in its own hands. But with the presidential office, there still comes a whole series of traditional duties (e.g., chairing government meetings, performing representational functions).

Regional elections

Although there has been a wide-ranging process of legislative centralization since the 1848 foundation of the Swiss federal state, the 26 Swiss cantons have retained considerable administrative and, especially, fiscal autonomy (Dardanelli & Mueller Reference Dardanelli and Mueller2019). Because there is obviously something at stake, it is crucial to closely monitor the regional (i.e., cantonal) “electoral arenas” as well. In 2022, elections were held in the cantons of Nidwalden, Obwalden, Vaud, Bern, Glarus, Graubünden, and Zug in that respective chronological order. While the cantons’ distinct “institutional patterns” (Vatter et al. Reference Vatter, Arnold, Arens, Vogel, Bühlmann, Schaub, Dlabac and Wirz2020) in terms of, for example, the electoral systems, as well as other idiosyncratic, context-specific effects (e.g., the role of personalities) matter, the cantons are still “echo chambers” (Bochsler Reference Bochsler2019: 401). Electoral swings in cantonal elections held in the second to the fourth year of the national election cycle can best be predicted by looking at the electoral swings in other cantons (ibid.). In the 2022 cantonal elections, this empirical interconnectedness was clearly visible. The electoral outcomes in the seven cantons have further consolidated the three major trends that have been visible since the last Swiss national elections back in 2019. The first major trend is the inroads both the Green Party (GPS/PES) and the Green Liberal Party (GLP/PVL) kept making—with the “green wave” rolling mostly at the expense of the SPS/PSS (especially in Bern and Vaud), but elsewhere also to the detriment of the Liberals (FDP/PLR (e.g., in Ob- and Nidwalden). Second, the four national-level governing parties—SPS/PSS, The Centre/Le Centre,Footnote 1 FDP/PLR, and Swiss People's Party (SVP/UDC)—are having a hard time appealing to voters. Most notably the Christian-democratic, center to center-right Centre/Le Centre, but to a somewhat lesser degree also the social-democratic SPS/PSS, suffered (significant) electoral losses. The records of the center-right FDP/PLR and the radical right-wing populist SVP/UDC were more mixed, as both political parties managed to (slightly) increase their vote share in certain cantons (i.e., Obwalden, Glarus) while still being defeated in a majority of places (i.e., Nidwalden, Vaud, Bern, Graubünden; Zug only in terms of SVP/UDC). A third and final major trend is the increasing proportion of female MPs in cantonal parliaments. With the exception of the canton of Obwalden, women progressed in all seven cantons by over 1.2 (Zug) and 11.6 percentage points (Graubünden) as compared to the last cantonal election. All in all, the results of the 2022 cantonal elections thus mark important “political windsocks” ahead of the 2023 Swiss federal elections.

Data on the regional elections can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Results of regional (i.e., cantonal) elections in Switzerland in 2022

Notes:

1. The residual category labeled “Other” (Übrige) encompasses minor (or splinter) political parties that are grouped together by the Federal Statistical Office. A detailed breakdown can be found in the below-mentioned source.

2. In the canton of Vaud, numerous multi-party lists competed for votes (Mischlisten).

3. In the canton of Graubünden, SPS/PSS and GPS/PES competed for votes on a joint list (gemeinsame Liste), which obtained a total of 22.7% of the total votes cast. This is why the respective vote share of SPS/PSS and GPS/PES cannot be reported each individually.

4. In the canton of Zug, the Alternative Linke Zug (Alternative Left Zug) joined the Green Party back in 2009 to form the Alternative—die Grüne Zug (Alternative Left—the Greens Zug). The votes that the joint list of the Alternative—die Grüne Zug obtained in 2022 are listed in the row that displays the vote share of the GPS/PES.

Source: Federal Statistical Office (2023).www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/politik/wahlen/kantonale-parlamenswahlen.html

Referenda

In 2022, Swiss voters voted on 11 nationwide ballot proposals, that is, a total number that is slightly above the average of some nine nationwide ballot proposals annually during the last three decades (Swissvotes 2023). Following the pre-fixed “referendum days,” Swiss voters headed to the polls thrice.

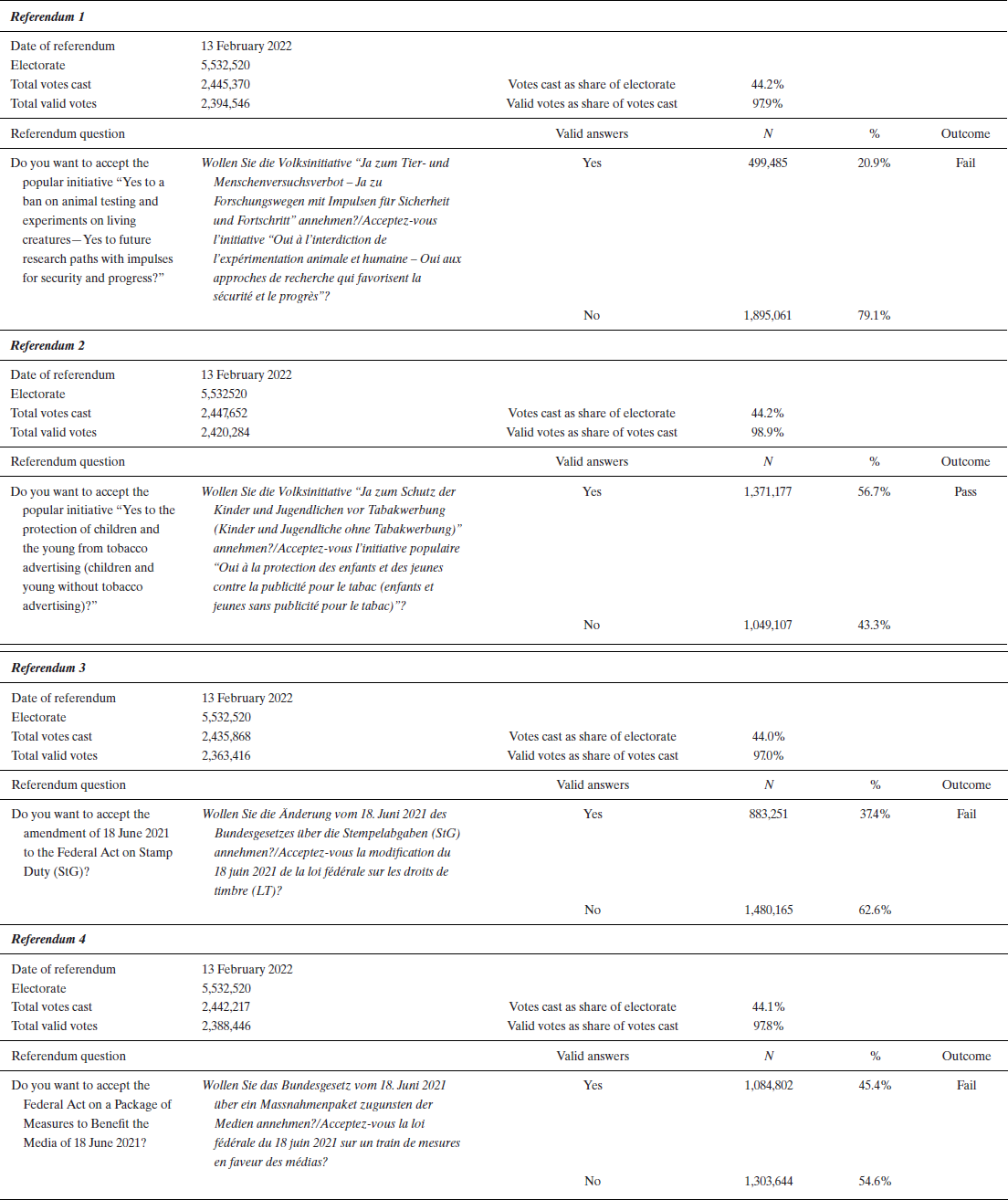

The first popular vote took place on 13 February 2022 when four proposals were on the ballot (Table 2). The popular initiative “Yes to a ban on animal testing and experiments on living creatures” sought to ban all experiments on humans and animals, along with the import of new products developed using such methods. Whereas supporters wanted to halt tests, stressing they are unethical and unnecessary, the “No” committee supported by, for example, the umbrella organizations for higher education institutions and the powerful pharmaceutical industry, raised concerns that a ban would harm the research and health sectors. With a share of only 20.9 per cent “Yes” votes and none of the 26 Swiss cantons in favor, the plan to make the country the first one worldwide to ban animal testing was among the least supported nationwide ballot proposals of all time (Swissvotes 2023). As revealed by the post-ballot survey, the vast majority of voters prioritized medical treatment and basic research over animal welfare, believing that the current level of animal testing is already limited to what is absolutely necessary (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Jenzer, Tschanz and Rey2022a: 16–23).

Table 2. Results of four referenda held on 13 February 2022 in Switzerland

Source: Swissvotes (2023).

On the same day, Swiss voters also voted on a second popular initiative, entitled “Yes to the protection of children and the young against tobacco advertising.” Even though being home to the world's largest cigarette companies, Switzerland has historically had one of the weakest laws against tobacco advertising and sponsorship in Europe. Moreover, research has shown that most adult smokers—around one in four people in Switzerland—began when they were minors, also due to exposure to tobacco advertising in public places. The proponents’ core message that health is more important than economic interests obviously hit a nerve, as 56.7 per cent of the voters and 15 cantons backed the popular initiative. Since the instrument's 1891 introduction, this was only the 25th popular initiative that has passed the rigid “double-majority requirement” of approval of a majority of those who vote and a majority of the cantons. Exit polls indeed emphasized the broad acceptance it received among left-leaning and center voters (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Jenzer, Tschanz and Rey2022a: 24–32).

The third proposal of the day was a referendum on the amendment of the Federal Act on Stamp Duty. In Switzerland, a stamp tax on equity capital is levied when a company wants to raise funds by issuing securities (e.g., stocks, shares). It is imposed only on amounts above CHF 1 million, and it currently amounts to 1 per cent of the value of the capital raised. According to the Federal Council's estimates, around 2300 businesses paid stamp duty in 2020, generating around CHF 250 million a year. To speed up the bounce-back in the economy after the COVID-19 crisis and to boost the Swiss financial industry's international competitiveness, the Parliament wanted to reduce the tax burden on large companies by ending the stamp tax. While a majority of Swiss MPs stressed the economic benefits of tax cuts, the left-wing parties along with the trade unions launched a referendum, decrying the measure as a “gift” to the richest multinationals. The stamp duty was dismissed at the ballot box (37.4 per cent “Yes” votes) with the electorate worrying that citizens would have to make up for the shortfall in revenue (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Jenzer, Tschanz and Rey2022a: 33–41).

Finally, on 13 February, Swiss voters also decided on a referendum on a package of state-funded measures to benefit the media. In light of the numerous challenges the media faces (e.g., huge losses in advertising revenue due to tech giants like Google and lower subscriptions), Parliament adopted a new government policy to allocate a total funding of around CHF 3 billion over a seven-year period. The package included both indirect subsidies (e.g., subsiding of morning newspaper delivery) as well as direct subsidies for online media and for outlets with decidedly regional/local content. In fear of the emergence of uncritical “state media” and concerns over disproportionately privileging Switzerland's large publishing houses, a committee of politicians mainly from the right of the political spectrum launched a referendum to veto parliament's decision. Winning only 45.4 per cent of the vote, the government-sponsored measures to benefit the media fell short of a majority. For most voters, their vote was a matter of principle: Taxpayers’ money should not be spent on media (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Jenzer, Tschanz and Rey2022a: 42–50).

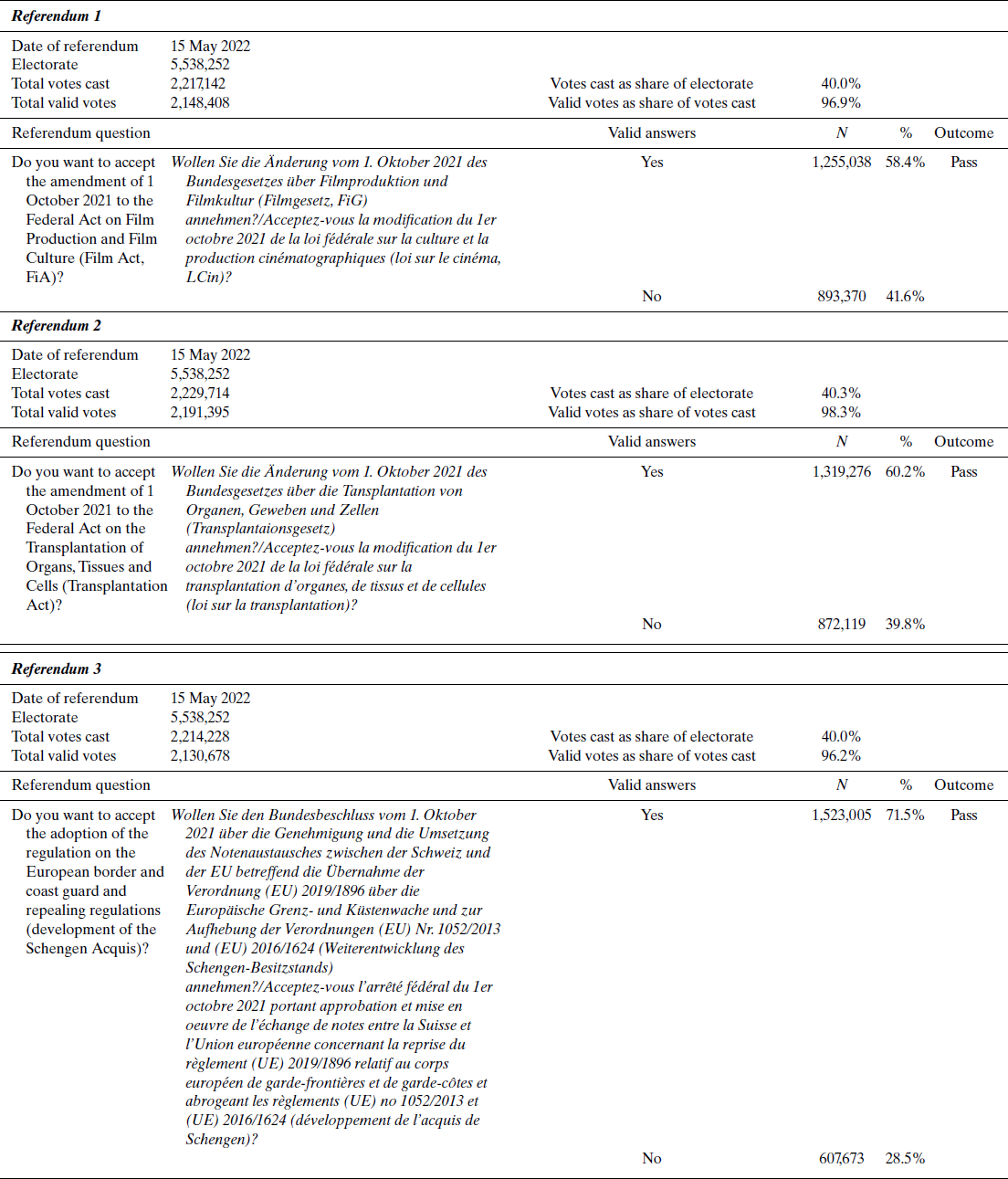

On 15 May 2022, Swiss voters voted on three optional referendums (Table 3). Known as “Lex Netflix (Netflix law),” the referendum on the amendment to the Federal Act on Film Production and Film Culture challenged Parliament's decision to oblige online streaming platforms to invest up to 4 per cent of their revenue from Switzerland in Swiss films and TV series. Should they fail to do so, Netflix, Amazon, Disney+, and the like will have to pay an equivalent tax aimed at promoting the Swiss film industry—a measure that applies in similar veins in almost half of the countries in Europe. While a referendum committee led by the youth wings of Switzerland's center-right and right-wing parties saw the compulsory investments requested from online streaming platforms as an attack on economic freedom, a solid majority of 58.4 per cent of the voters approved the legislation with a view to supporting the domestic film industry (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Jenzer, Tschanz and Rey2022b: 14–21).

On the same day, Swiss voters also got to vote on the referendum on the amendment to the Federal Transplantation Act. By means of a counterproposal to a popular initiative, Parliament decided on a fundamental change in the national organ donation system: moving from explicit to presumed consent. The system change was meant to catch up with European countries where the principle of presumed consent for organ donation is widespread. Moreover, the reform was deemed necessary as demand for organs outstrips supply. The referendum passed with 60.2 per cent “Yes” votes with hardly any segment of the voting population largely opposing the new “opt-out” system of organ donation (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Jenzer, Tschanz and Rey2022b: 22–30).

Third and finally, the funding of the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) was put to a referendum vote. As a member of the border-free Schengen Area, Switzerland contributes to the funding of Frontex proportional to its gross domestic product (GDP). The agency's global budget has been increased in the aftermath of the 2015 migrant influx in order to deploy more staff on the ground as a means to tighten control of EU's external borders. Amid concerns over the “militarization of borders,” “criminalization of migration,” and migrant pushback, migrant support organizations and green/left-leaning political parties jointly initiated a referendum. However, a vast majority of 71.5 per cent of the voters endorsed the increase of the country's contribution to Frontex, mostly due to security considerations (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Jenzer, Tschanz and Rey2022b: 31–39).

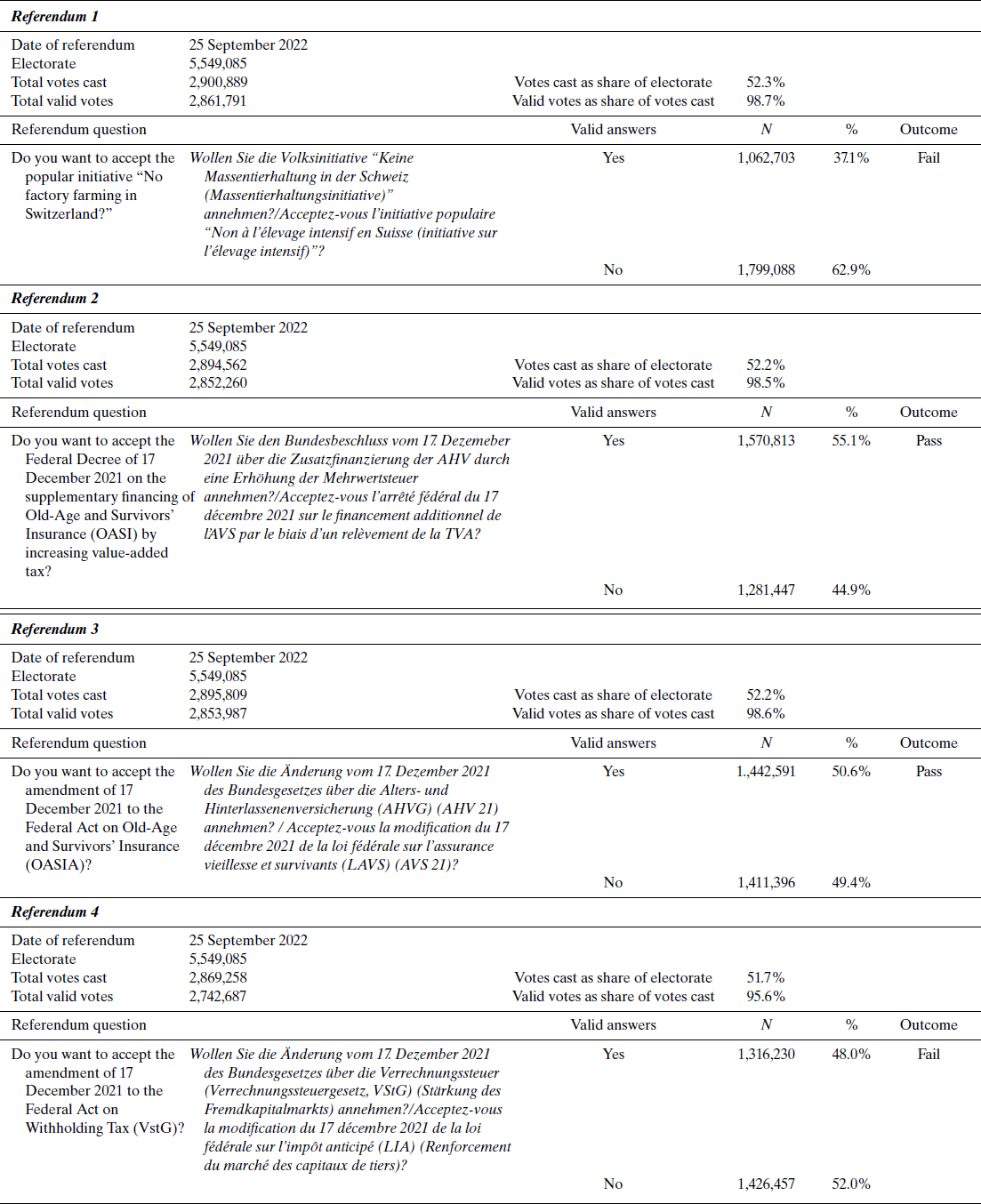

On 25 September 2022, another four proposals were on the ballot (Table 4). The popular initiative “No factory farming in Switzerland,” launched by animal rights and welfare organizations, aimed at both eradicating intensive livestock and poultry farming and imposing stricter important regulations for animal products. Yet the clear rejection of only 37.1 per cent “Yes” votes and only one approving “half-canton” was a sign that voters were not convinced by the claim that there was abuse in need of fixing, especially since Switzerland has some of the strictest animal protection laws anyway (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Jenzer, Pagani, Tschanz and Rey2022c: 17–24).

Table 4. Results of four referenda held on 25 September 2022 in Switzerland

Source: Swissvotes (2023).

The second and third proposal of that day were both linked to the reform of the Federal Act on Old-Age and Survivors’ Insurance (OASI), that is, the cornerstone of the three-pillar Swiss social insurance system. The OASI scheme, introduced in 1948, is financed through salary deductions in a pay-as-you-go system. As its long-term financial stability was at risk due to, for example, the rise in life expectancy, the government and Parliament worked out a comprehensive reform (“OASI 21”). Among other things, “OASI 21” stipulated the increase of the ordinary retirement age for women from 63 to 65 (including compensatory measures for “female transitional generations”) and flexible retirement age rules, as well as the rise in value added tax (VAT) on goods and services from 7.7 per cent to a new rate of 8.1 per cent. Although raising the ordinary retirement age for women remained a major bone of contention (especially for the political left and trade unions), both proposals—that is, the supplementary financing of OASI by increasing VAT passed and the “OASI 21” package—passed with a “Yes” vote share of 55.1 per cent and 52.2 per cent, respectively. This is a notable outcome as over the past 25 years, a series of OASI reform proposals were rejected, most recently in 2017 (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Jenzer, Pagani, Tschanz and Rey2022c: 25–45).

The fourth and final proposal on which the Swiss electorate decided on 25 September 2022 was the referendum on the Federal Act on Withholding Tax meant to challenge Parliament's decision to scrap the 35%-withholding tax on interest from Swiss bonds. Amid a deteriorated state of the economy, however, only a minority of 48 per cent “Yes” voters supported the tax cuts whose main beneficiaries would have been wealthy investors (Golder et al. Reference Golder, Mousson, Keller, Venetz, Jenzer, Pagani, Tschanz and Rey2022c: 46–54). This was also the last proposal put to the ballot in the year 2022—and, in fact, the last in a while.

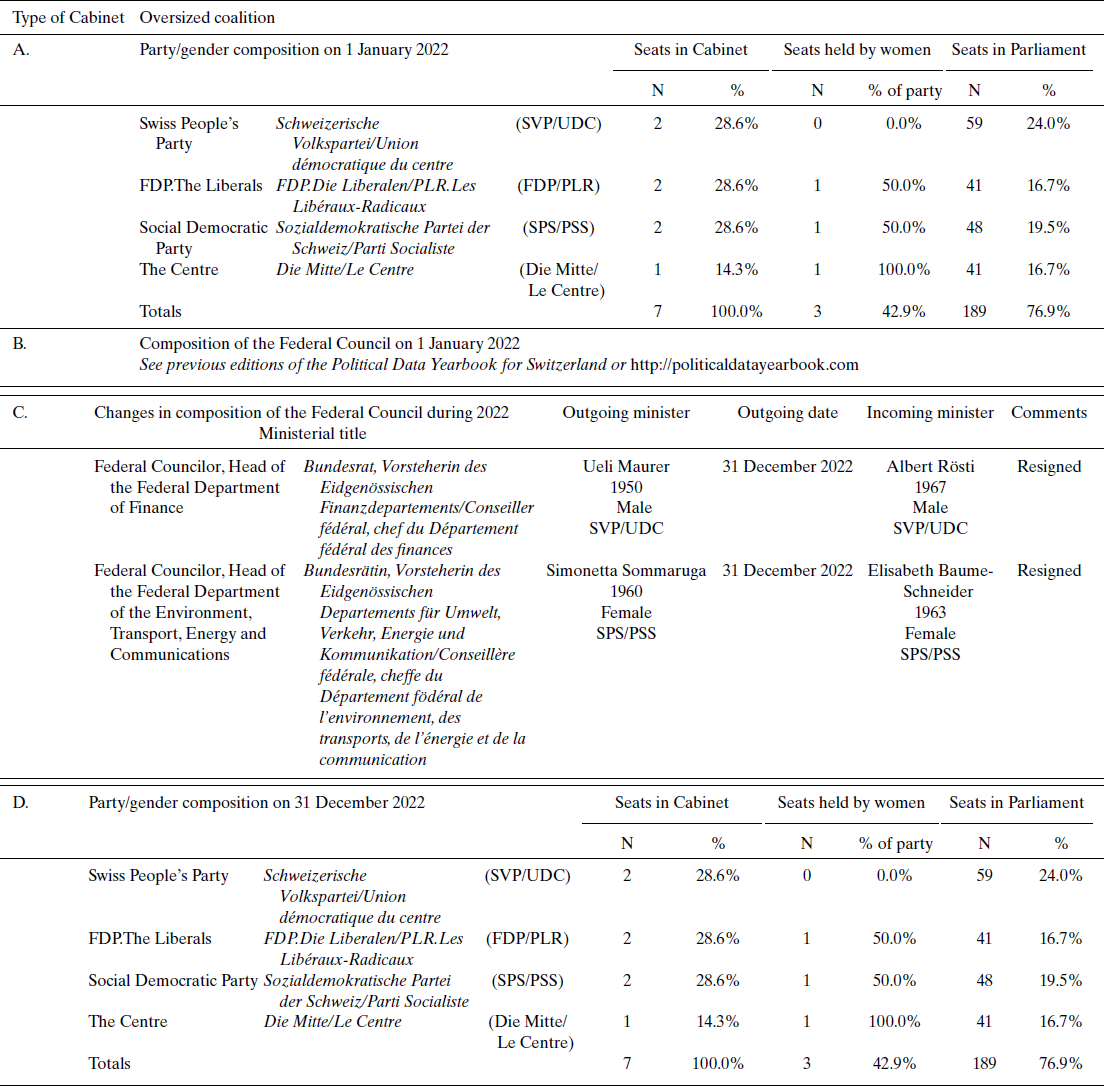

Cabinet report

In 2022, two members of the Federal Council announced their resignation by the end of the year. Ueli Maurer (SVP/UDC), Federal Councillor and Head of the Federal Department of Finance, pronounced that he is stepping down on 30 September 2022. On 2 November 2022, family reasons made Simonetta Sommaruga (SPS/PSS), Federal Councillor and Head of the Federal Department of the Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications, take the same decision after her husband suffered a stroke. With a period of office of 14 and 13 years, respectively, both Federal Councillors have served for a period well above the average of some 10 years (Vatter Reference Vatter2020: 112). Parliament was due to elect successors on 7 December 2022. In Swiss-style consociationalism, the outcome of government elections is in uttermost cases a story of “fresh faces, old coalition formula”: The two outgoing ministers were replaced by Federal Councillors-elect Albert Rösti (SVP/UDC) and Elisabeth Baume-Schneider (SPS/PSS), respectively. Hence neither the party-political nor the gender composition of the Cabinet has changed (Table 5). Still, there was a historic component in the election as Baume-Schneider became the first person from the canton of Jura to be represented in the Swiss national government—that is, the youngest canton, which was founded in 1979 amid a severe territorial conflict. Noteworthy, with an average age of 60 years, Switzerland now has the oldest Cabinet in Europe (Zumbrunn et al. Reference Zumbrunn, Schaub and Freiburghaus2023).

Table 5. Cabinet composition of the Federal Council (Bundesrat/Conseil fédéral) in Switzerland in 2022

Notes:

1. In Switzerland, the term of office of the members of the national government is constitutionally fixed, that is, all Federal Councillors are elected for a four-year-period. The Cabinet cannot be dismissed/dissolved. The term of this Council is from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2023.

2. “Parliament” refers to the United Federal Assembly and thus consists of the seats in both chambers (i.e., National Council and Council of States), adding up to a total of 246 seats.

3. The President and the Vice-President of the Swiss Confederation rotate annually. Since they are elected from the seven members of the Federal Council, their one-term-period-of-office does not change the party/gender composition of the Cabinet (see section “Election report” for details).

Source: The Federal Council (2023).

Parliament report

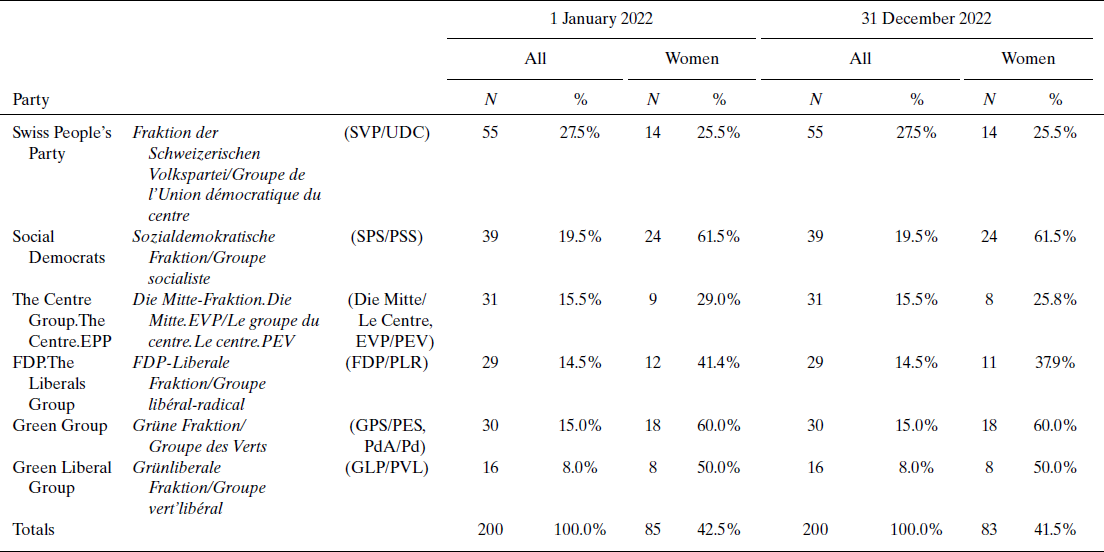

In 2022, six MPs of the lower house (National Council) stepped down for reasons ranging from resignation from political offices altogether to election to the Federal Council or the government of their home canton. While the party-political composition of the lower house was not affected by the legislative turnover, the share of female National Councillors was slightly pushed down from 42.5 per cent to 41.5 per cent (Table 6).

Table 6. Party and gender composition of the lower house of Parliament (Nationalrat/Conseil national) in Switzerland in 2022

Notes: Parliamentary groups are not identical to political parties, as either MPs who belong to the same political party or MPs who share similar ideological views may get together to form a parliamentary group.

Source: The Federal Assembly (2023).

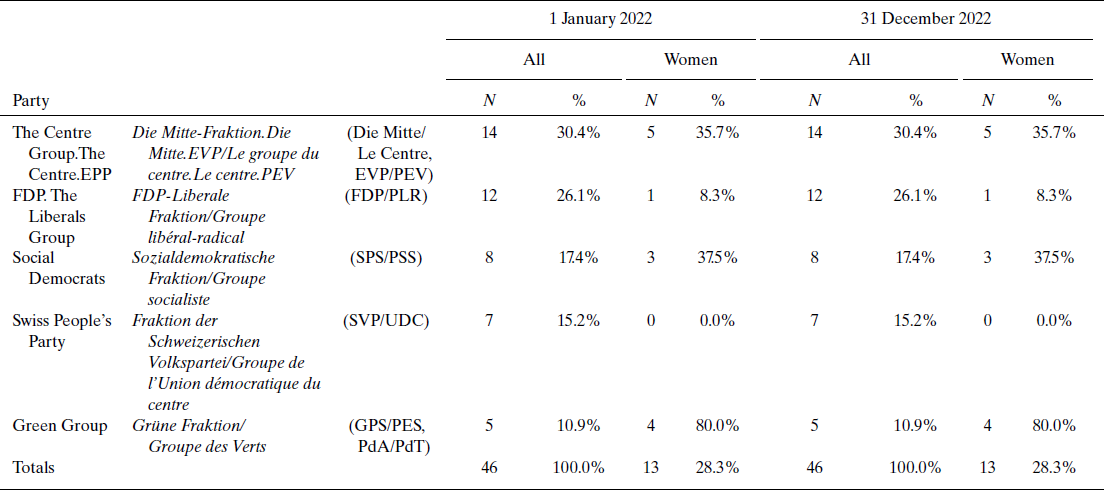

In the upper house (Council of States), there has been but one change: as Elisabeth Baume-Schneider (SPS/PSS), Councillor of States, was elected to the national government, Mathilde Crevoisier Crelier (SPS/PSS) was sworn in her place to represent the canton of Jura (Table 7).

Table 7. Party and gender composition of the upper house of Parliament (Ständerat/Conseil des États) in Switzerland in 2022

Source: The Federal Assembly (2023).

Political party report

There were no changes in the Swiss party landscape, neither in terms of the parties’ organization nor in terms of leadership.

Institutional change report

At the national level, no major institutional changes occurred besides the amendments to the Federal Constitution, triggered by the popular initiative requesting a ban on tobacco advertising and sponsorship as well as by the mandatory referendum on the rise in VAT, which both passed in a popular vote (see section “Election report”).

Turning to the cantons, the complete overhaul of the electoral system in the canton of Graubünden is worth mentioning. In early 2022, Graubünden and Appenzell Innerrhoden were the only two remaining cantons utilizing purely majority and plurality methods for cantonal elections. In 2019, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court, however, ruled that Graubünden's electoral system violates the principle that every vote counts the same and is thus unconstitutional. After Graubünden's electorate rejected the switch to proportional representation (PR) eight times at the ballot box, the 2021 “Bündner Kompromiss” finally passed—a compromise that delicately balanced proportional representation of all votes and proportional representation of all valley populations (regions). The 2022 cantonal elections were thus the first ones held under biproportional apportionment, that is, a PR method that is also common in other cantons (Vatter et al. Reference Vatter, Arnold, Arens, Vogel, Bühlmann, Schaub, Dlabac and Wirz2020).

Issues in national politics

Traditionally, the Swiss political discourse is largely shaped by the practice of direct democracy, that is, the many proposals that are put to the ballot up to four times per year. Also in 2022, popular votes have set new topics on the agenda (e.g., eco-friendly farming, animal welfare), forced the political elite to take a stand on “morality politics” (e.g., organ donation), and/or manufactured broad ad hoc campaigning coalitions Swiss politics is in need of in order to pass the high referendum hurdles (e.g., OASI reform).

Besides, there have been two major and highly controversial “elephant-in-the-room” issues. The first issue is Swiss–EU relations. After the Federal Council unilaterally broke off negotiations with the EU on an overriding institutional framework agreement in 2021, both sides kept struggling to sort out their differences and to look for a new way forward. The exploratory talks since the Swiss rejection of the deal have revealed a political standoff: Switzerland has continued to seek opt-outs of some of the single market rules, while Brussels is not keen to concede too much. The manifold consequences of this ongoing stalemate are all obvious. Most notably, Switzerland's loss of participation in the “Horizon Europe” research program is a heavy blow for Swiss universities (Wasserfallen Reference Wasserfallen, Emmenegger, Fossati, Häusermann, Papadopoulos, Sciarini and Vatter2024).

Second, in light of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent global turmoil, 2022 was also marked by numerous attempts at gearing up the country for future crises. In principle, Swiss-style consensus democracy is more capable of crisis management than majoritarianism (Freiburghaus et al. Reference Freiburghaus, Vatter and Stadelmann-Steffen2023). Still, the COVID-19 pandemic, the massive influx of refugees, and the looming energy crisis have shown that intergovernmental relations between the federation and the cantons, as well as the institutional make-up of the Federal Council, are in dire need of reform (e.g., Freiburghaus & Mueller Reference Freiburghaus, Mueller, Emmenegger, Fossati, Häusermann, Papadopoulos, Sciarini and Vatter2024; Freiburghaus et al. Reference Freiburghaus, Mueller, Vatter, Chattopadhyay, Knüpling, Chebenova, Whittington and Gonzalez2021). Otherwise, the Swiss federal government will need to continue to use emergency powers to speed up the required responses. These are challenges that have been identified by scholars and practitioners alike—but have so far failed to pass the rigid rules for institutional reform(s) in Switzerland.

Acknowledgement

Open access funding provided by Universität Bern.