Introduction

The manifestations of popular culture of the carnival type are part of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity and have usually been valued as spaces of creativity and criticism through humour. However, this perspective is too one-sided and cultural populist and ignores the dark side that can also be contained in these cultural manifestations (Putman, Reference Putnam2002). Thus, we can currently observe the proliferation of hate speech and manifestations of disrespect for minorities that run parallel to the rise of the extreme right in Europe (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007), and which in Spain have been concretised in the entryist and ethno-nationalist turn of cultural policies in various autonomous regions, including Valencia (Rius-Ulldemolins et al., Reference Rius-Ulldemolins, Rubio-Arostegui and Gracia2025).

Festivals are generally seen as spaces of freedom and expression. However, xenophobic positions and hate speech have been denounced during the interwar period and, more recently, since the beginning of the 21st century. We understand hate speech as defined by the UN: “any form of communication, whether oral or written, or conduct that attacks or uses derogatory or discriminatory language in reference to a person or group on the basis of who they are, in other words, on the basis of their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other forms of identity” (Naciones Unidas, 2024). In this sense, expressions of humour containing grammars used by anti-national minorities and racism have been updated in a more indirect but equally effective way, linking ethnic minorities to degrading or dehumanising situations through their representation, under the pretext of freedom of expression in festive moments. This has been observed in neo-traditional festivals in Belgium and, to a lesser extent, in some expressions of festive culture in Valencia. While often portrayed as inclusive and humorous, the Fallas have increasingly featured symbolic representations that marginalize political opponents, particularly Catalan nationalists, as well as other minority groups. In this context, festive culture serves not merely as a mirror of societal tensions, but as a tool of ideological struggle, especially as right-wing and far-right actors have gained ground in the local political and symbolic order.

In this way, we start from the view that festive culture groups are key political actors in cities where events take place that hold social centrality and have the capacity to shape local identity. Although they do not correspond to political elites or ideological groups, their actions and the development of images and performances in the streets clearly contribute to producing a political discourse and influencing local politics, making them key agents in this sphere. For this reason, political elites seek to maintain good relations with the elites of the festive sector through their recognition (awards and laudatory speeches) and through cultural evergetism (funding via subsidies, tax exemptions, and privileges in the use of public space), which creates bonds and a sense of indebtedness—à la Mauss—of participants toward the promoters of the festivities (Picard, Reference Picard2016).

For example, we can see this type of relación entre politics and festival associations in the Fallas of Valencia, which, although they are a neo-traditional festival of great dimensions due to the attractiveness of the public and, above all, the active participation of the people, since the victory of the fascist side in the Civil War and their instrumentalisation of the festival, have constituted a space controlled by the victorious elites of a space that until then had been popular and democratic (Hernández i Martí, Gil-Manuel, Reference Hernández i Martí and Afers1996). Since the transition to democracy, the Fallas have evolved into a space for participation and creative expression, earning recognition as intangible heritage by UNESCO in 2015. However, a dominant sector, aligned with right-wing and far-right ideologies, has instrumentalized the festival. This has given rise to a growing discourse of hate that has its origins in the end of the Franco regime but has become more radical in parallel with the rise of independence in Catalonia and the government of the left-wing coalition in local and regional government (Dowling, Reference Dowling2018; Roig, Reference Roig2020).

The methodology of this study follows a mixed approach. First, we quantified the manifestations against Catalanism and Valencianism. Subsequently, we conducted a process of observation, photographic recording and analysis based on: (a) the photographic analysis of the ninot exhibitions (figures and posters) of the Fallas 2018-2024, b) the observation of the special category Fallas (the most important Fallas) from 2018-2024, c) the registration of the news about figures or ninot referring to Catalan or Valencianist political leaders from 2018-2024 in the main Valencian and national media (Levante-EMV, Las Provincias, ABC, El país, El diario). And d) the publications on the social network X of the VOX party (extreme right) about Fallas between 2018 and 2024 were analysed with the help of the Netylic programme (173 registrations were generated from the official accounts of the party, its councillors and regional deputies). Overall, the analysis is part of the research project on cultural policies and cultural wars funded by the Special Research Action Programme - University of Valencia (UV-INV_AE-3674253).

Festive culture and local politics: the symbolic power to define local identity and its exclusions

Festive culture has received increasing attention for its importance to the local economy and tourism, as well as its role in shaping urban branding and local identities (Langman, Reference Langman2003; Ravenscroft & Matteucci, Reference Ravenscroft and Matteucci2003). Analyses of carnival-style festivals often emphasize them as opportunities to redefine personal and local identity in terms of freedom and agency (Bogad, Reference Bogad2010; Gilmore, Reference Gilmore1998; Spooner, Reference Spooner1996). However, we argue that this approach, which reads the festival as a space of exception and freedom, overlooks the fact that it is also controlled by elites and that the representations it produces can reinforce existing domination and discrimination in society, particularly against women and social minorities (Gilmore, Reference Gilmore1995; Gisbert & Rius-Ulldemolins, Reference Gisbert and Rius2020). Moreover, some authors like Gil-Calvo have pointed out the importance of festivities—especially in Spain—for constituting a sense of “us” or a kind of “festive patriotism” (Gil Calvo, Reference Gil Calvo2012). In this sense, cooperation in organizing the festivity strengthens social ties and creates a potential social base for political mobilization or, in Bourdieusian terms, a form of social capital that can be mobilized as political capital (Mauger, Reference Mauger2023).

In addition, as Randall Collins (Reference Collins2005) notes, contemporary rituals in modern societies help define the symbols of local identity and, through inclusion or exclusion, draw the boundaries of those who are considered part of the collective. This is particularly evident in the way the far right in Spain reclaims symbols and religious elements that explicitly or implicitly exclude migrant communities. A notable example is the use of pork and its distribution in festive public spaces to assert local identity, as practiced by VOX or Aliança Catalana (Costa, Reference Costa2002; Maldita, 2023).

In this sense, participation in the ritual marks belonging, just as it did in the ancient cities described by Fustel de Coulanges (Fustel de Coulanges, Reference Fustel de Coulanges1984). Thus, exclusion from the ritual—or mockery within it—has political effects that go beyond the festive world, and it generates a form of autochthony capital (with centers, peripheries, and the excluded) that shapes local politics in ways that are less visible but no less real than explicit political affiliations (Retière, Reference Retière2003). Likewise, the images created in festive rituals may, as Turnbull-Dugarte and Dugarte argue in relation to figures of pop culture, reinforce a biased reading of political orientation and a polarization of political positions (Turnbull-Dugarte SJ, Reference Turnbull-Dugarte2025), rather than fostering consensus as festive culture is typically assumed to do.

For all these reasons, we believe that analyzing the discourses produced within the framework of festive rituals is key to understanding the definition of national and local identity in contemporary Europe. And it is relevant to do so from the perspective of the sociology of conflict, focusing not only on its socially integrative intention, as is usually emphasized (cf. Costa, 2001). This view seems to us partial and idealized; it is also necessary to recognize the dark side of festive culture and its exclusionary effects through the development of hate speech and the symbolic exclusion from local identity. Similarly, the analysis of festive culture and its discourses is crucial to understanding the processes of construction of national and local identities in 21st-century Europe—and, in some cases, their instrumentalization by the far right.

Humour and hate speech: the dark side of festive culture

Festive culture has usually been analysed as a space of freedom for temporary transgression of the symbolic order and critique of political power (Bogad, Reference Bogad2010; Burke, Reference Burke2007). However, we can find another, darker side to carnival rituals, as in the case of carnivals in Europe in the 1930s: this is the case of the Cologne Carnival of the Nazi regime, which, while promoting the event at a national level, imposed rules on its organisation and promoted its nazification through the dissemination of party flags or costumes or references to Jews (Dietmar & Leifeld, Reference Dietmar and Leifeld2010).Footnote 1 In recent years, we have witnessed some cases where an intense debate has been generated in relation to festive culture and hate speech and minoritiesFootnote 2. This is the case in Belgium, where several incidents during the Carnivalesque festivities in the 2000s have led to an intense debate between organisations defending minorities (anti-Semitic, anti-racist) on the one hand, and the organisers of the festivities, almost always supported by the Belgian authorities, on the other.Footnote 3 Therefore, after a process of deliberation, UNESCO decided to remove the Aalast Carnival from the list of intangible cultural heritage of humanity (UNESCO, 2019). The decision was justified by the fact that Article 2 of the Convention for the Protection of the Intangible Heritage states that “only intangible cultural heritage shall be taken into consideration, in accordance with existing instruments relating to human rights, as well as the requirement of mutual respect between communities, groups and individuals” (UNESCO, 2003). Given the repetition of elements that encourage stereotypes and prejudices, the lack of response from the authorities, and the fact that their inclusion on the list has not promoted dialogue between communities but, on the contrary, their confrontation, due to the national and global dissemination of these events through traditional and digital media.

However, this is not the only case of events linked to anti-ethnic minorities or racism in Belgian festive culture. For example, the Eftepië carnival society paraded in an SS uniform, alluding to the debate about the Zwiarte Piet (Black Peter), a character representing St Nicholas’ page, in which participants dress up and paint their faces black. This black face has caused controversy among anti-racist groups and carnival organisers. The Flemish Minister for Culture responded to UNESCO’s request for information by apologising for the action, placing it in the transgressive context of carnival: “We condemn all forms of anti-Semitism and racial hatred, but carnival remains, of course, a time when people are grotesquely mocked. With stereotypical exaggerations. I suppose that the participants can judge, in all wisdom, whether they cross the line or not and whether they hurt or discriminate against certain people” (UNIA 2019). In short, he refused to sanction or regulate carnival demonstrations by appealing to the participants’ judgement or freedom of expression.

Conflicts over the boundaries of humor and festive culture also exist in other contexts. Although we cannot provide a comprehensive mapping of all international cases, blackface representations are perhaps another clear example of the debate over the limits of humor and their consideration as cultural racism within the context of festive culture in Europe, the United States, or Latin America (Johnson, Reference Johnson and Johnson2012; Lemmens, Reference Lemmens2017; Roper, Reference Roper2019). Furthermore, closer to home in Valencia, this debate has emerged in various expressions of popular culture, such as the Moros i Cristians festival, where Islamophobic discourse can be observed (Santamarina, Reference Santamarina2008) and, in a more incipient form, in the Fallas festivities. It is true that these discourses are legitimized through traditionalist arguments—on the grounds that they are part of the historical fabric of the festivity—or relativized by claiming that the participants are not racist and that such expressions are simply part of a satirical tradition (idem). However, this argument is increasingly being questioned, as the target of the satire is particularly focused on minority groups, and the resulting media and political impact is being instrumentalized, as we have seen, by a far right that uses traditional culture as a battleground in the cultural war. In this context, it has gained social support in the city of Valencia, where, as of 2023, it has entered local government (Rius-Ulldemolins et al., Reference Rius-Ulldemolins, Rubio-Arostegui and Gracia2025).

Las fallas: festive culture and the instrumentalisation of Spanish nationalism

The Fallas emerged in the 19th century as a form of popular culture, characterized by humor and social criticism in many of its monuments (Hernández i Martí, Gil Manuel Reference Hernández i Martí1997). For this reason, the local government and the elite tried to repress the fallas with coercive measures and administrative fines, as they considered them to be manifestations critical of the authorities. However, the popularity of the festival and its celebration, despite the obstacles imposed, made the bourgeois authorities take an interest in it and create their own commissions to transform and ennoble the festival. Likewise, the elite discovered that they could use it to their advantage in order to legitimise themselves socially, and so the Fallas became the city’s festive ritual par excellence. In the words of Antonio Ariño (1992a), the maximum sentimental expression of València, like a new ‘local civil religion’.

In this way, the Fallas were originally a plural and critical festival that remained outside institutional control, which is why they retained their popular and progressive character until the end of the Civil War (1936-1939). The new Francoist dictatorship undertook a radical reform of the festive ritual, associating it with national Catholicism and right-wing regionalism. For this reason, the new regime intensified its control over the Fallas festivities through a network of regulations, rules and specific institutions that put an end to the previous political and ideological pluralism that characterised the Fallas, transforming them into a propagandistic expression of the guidelines of the new regime (Hernàndez i Martí Reference Hernández i Martí and Afers1996). In this way, the Franco regime inaugurated a long period in which the festival became an instrument of hegemony in the political and social life of the city. In the same way that the Junta Central Fallera paid homage to the dictator, the tradition of paying homage to the Verge dels Desamparats (local patron saint) was invented in accordance with the national Catholic ideology that legitimised the regime.

Parallel to this mutation of the centre of the festive ritual from satirical monument to national-catholic homage, an organising body was created, the Junta Central Fallera, as a body directly controlled by the local government and the Fallas elite, who exercised control over the Fallas commissions through the distribution of funds and prizes. Thus, under the Franco regime, the Fallas were thoroughly reinvented (Hernández i Martí, Gil Manuel, Reference Hernández i Martí2002), creating an alliance between the Franco regime and the status groups organised through the JCF, based on the exchange of legitimisation by the Fallero world and the support of the participants in the ritual in exchange for very generous regulations on the use of space and the distribution of resources by the regime and the local authorities (Gisbert-Gracia and Rius-Ulldemolins, Reference Gisbert Gracia and Rius-Ulldemolins2019).

By the end of the 1970s, with the transition to democracy, the Fallas were already a cultural product with enormous potential, with an increasing density of Fallas and competition for prizes, despite the instrumentalisation of the Franco regime, the accommodation of the local elite and the Junta Central Fallera. Certainly, in this context, there was a burst of creativity and openness to the popular quarters, as well as an increase in transgressive representations at a sexual and satirical level. However, the possibility of renewal was finally closed with the so-called Battle of Valencia. This offensive of right-wing regionalism against the then emerging left-wing nationalists (valencianist and also pro-catalanist) in the 1970s and 1980s), which closed the way to democratisation and the opening up of the world of the fallas in favour of a traditionalist reading of them (Hernàndez Reference Hernández i Martí2009). The Battle of Valencia was ultimately won by the far right (Flor, Reference Flor2011), and within the Fallas sphere, pro-regionalist and anti-Catalanist interpretations clearly prevailed among the Fallas elite—to the point that some commissions refused to burn their fallas in 1982 in protest over the exclusion of the term Kingdom of Valencia from the Statute of Autonomy, aligning themselves with blaverist political positions (Ariño Villarroya, Reference Ariño Villarroya1992). Furthermore, far-right groups used the Fallas festivities during the transition and early years of democracy to confront, threaten, and at times physically assault left-wing militants or commissions considered to be Catalanist (Rivero Casado, Reference Rivero Casado2021), prompting a retreat by these sectors from the official Fallas scene (Hernández i Martí, Gil Manuel, Reference Hernández i Martí1997; Rivero Casado, Reference Rivero Casado2021).

In response to this retreat by the left during the 1980s, and with the victory of the regionalist and Spanish nationalist right under the leadership of Rita Barberá from 1991 to 2015, the fallas were instrumentalised by the local post-Francoist right, reconstituted in the so-called Blaverismo movement - a conservative right-wing movement of an anti-Catalan and Spanish nationalist nature (Flor Reference Flor2011) - using the fallas universe as the backbone of their anti-progressive messages, which thus found widespread popular support within the framework of the new constitutional democracy (Peris Reference Peris2014). Since the 1990s, the Popular Party (right-wing Spanish nationalism) governments have used the Valencian local government and its ability to regulate and finance the Fallas, to which they allocate approximately €4 million, as a basis for a patronage network and to promote the presence of people linked to the right and far right in the presidencies of the Fallas (Rius, Gisbert and Vera, Reference Rius-Ulldemolins, Gisbert and Vera2021). With this direct control of the festival’s organising agency, the Junta Central Fallera (JCF), the regionalist right wing has ensured control of the discourse and the definition of a Valencian identity hostile to left-wing Valencianism and Catalanism, going so far as to label them as traitors and enemies of the Fallas festival and, with it, of a conservative Valencian identity and Spanish nationalism. In this way, the Fallas have been very useful in maintaining the hegemony of the conservative party in the city of Valencia for more than 20 years and in keeping the left-wing opposition at bay by excluding it from the ritual (Rius-Ulldemolins and Díaz-Solano, Reference Rius-Ulldemolins and Díaz-Solano2022). In fact, the right governed until 2015 and the left government lasted only two mandates - with a very virulent opposition to its policies - (Martín Cubas et al., Reference Martín Cubas, Rochina Garzón and González2020), with the right returning to government in 2023 in alliance with the extreme right, partly explained by the hegemony and in the fallas, as we will see below.

Las Fallas, social space and the political sphere in Valencia

The organizers of the Fallas festival receive substantial public funding annually, which in 2023 amounted to 11.096 million euros, of which the Valencia City Council contributed 7.8 million euros. (Pastor et al., Reference Pastor, Pardo and Martínez2024: 68). It can therefore be affirmed that in recent times the Fallas have undergone a marked process of institutionalisation and dependence on public funding, establishing themselves as a central event in local life under the discourse of tourist attraction (Hernàndez i Martí et al. Reference Hernàndez i Martí, Santamarina, Moncusí and Albert2005). A discourse that has been reinforced by its inclusion in the UNESCO Intangible Heritage List in 2016, which theoretically values the festival’s inclusivity in a collective creativity. (UNESCO, 2016).

However, this process of institutionalisation has not been accompanied by a process of democratisation of the festival and its participation, dividing Valencian society into a highly organised Fallas sector with a central social and political role, and an anti-Fallas sector that is usually ignored or absent from the festival. (RTVE, 2024). Thus, the Fallero rite brings together a relatively small part of the city (around one hundred and ten thousand people, according to the register of the Fallero commissions), barely 15% of the total population of 749,000 Valencian people. On the other hand, according to data from a survey carried out by the Department of Festive Culture among the Fallero community, this sector is mainly Spanish-speaking (58%), regionalist and Spanish (80.2% feel as much Valencian as Spanish or more Spanish than Valencian), and practising and non-practising Catholics (74.6%). It is also significant that only 0.6% of those registered are immigrants (Ajuntament de València, 2017) and, among them, most are of European origin. Non-European immigrants, who make up 18% of the city’s population, are largely absent from the fallas (Ajuntament de València, 2024).

The division between Falleros and non-fallas, and the predominance of the former, is therefore largely explained by the instrumentalisation of the festival by traditionalist and conservative sectors, the so-called ‘blaverismo’ (Peris Reference Peris2014). This movement understands Valencianity as regionalism and, at the same time, as a form of Spanish nationalism that marks an alterity and confrontation with Catalan (Hernàndez i Martí Reference Hernández i Martí and Afers1996). A Catalanophobia expressed as a reaction of anger against real or imagined transgressions by Catalans against the object of the ritualFootnote 4. Finally, in the General Congress of the Fallas in 1980, they clearly aligned themselves with the thesis of anti-Catalan and right-wing regionalism, which constituted a conservative force in the face of the changes of the democratic period (Flor Reference Flor2011).

The political instrumentalisation of the Fallas: from Blavero regionalism to the construction of the “Catalan enemy”

Anti-Catalanism and anti-Valencian nationalism in the Fallas of Valencia

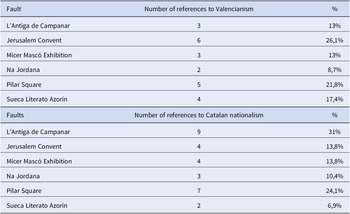

In the city of Valencia, Catalan nationalism was a constant theme, sometimes even more so than Valencianism itself. In general, references to Valencianism were more frequent than references to anti-Catalanism (61.7% compared to 38.3%). However, this is due to the fact that anti-Catalanism is activated by the Catalan historical context, as can be seen, Catalanism was very present in the years around the Battle of Valencia, where the political struggle between Blaverismo and Catalanism was a constant struggle for symbols (Flor, Reference Flor2011). In this way, the Fallas of Valencia were positioned on the anti-Catalanist side and contributed to consolidating the victory of the Spanish regionalist and conservative side, marginalising artistically, but also socially and politically, the opinions expressed by the Catalanist side. Later, when the political situation was calmer, Fallas Valencianism was able to focus on local Valencianism rather than Catalanism, and criticism and satire of Catalanism and Catalonia were left aside. However, as the Catalan independence movement began to gain strength, the Fallas monuments began to reactivate their references to Catalan nationalism, stigmatising and mocking it, using the same slogans as the more radical parties. In this way, from 2011 onwards, after two decades and with the Battle of Valencia seemingly over, the sense of fear that Valencian society would be linked to some elements of Catalanism led the Fallas to start erecting increasingly aggressive Falla monuments criticising Catalan leaders and the independence movement (see Table 1). On this occasion, Catalanism was mentioned more often than Valencianism, which is striking since fallas are supposed to be a space for local criticism and satire, and therefore national politics are usually excluded from fallas. There are some references to Madrid’s political leaders and national rulers, but the focus of criticism is local. In this way, the fallas show two basic themes: 1) the fallas focus on the Catalan question, as in the Battle of Valencia, to define what it means to be a good Valencian; 2) their definition of the good Valencian is completely opposed to that of the progressive sector.

Table 1. Number of references to Valencianism or Catalan nationalism

Source: own elaboration.

Although the organising committees of the Fallas do not express an explicit political stance, they do have an ideological bias, which can be seen in the perspectives of their directors and the relationships they establish with political entities. This is due to the fact that the cadafalc monument is usually proposed by the president of the commission or an elite within the commission, in such a way that the people with the most resources are the ones who have the power to decide what theme and what political link they want to give to the monument. These leaders, especially the presidents of the Fallera Commission or some of the Falleras Mayores, have a direct or indirect political link to the monument. (Gisbert Gracia et al., Reference Gisbert Gracia, Rius-Ulldemolins and Hernández i Martí2018). For example, the former president of the Exposició, Micer Mascò, was for several years a politician of the far-right party VOX and left his posts in the Diputación after being involved in legal cases (Navarro, Reference Navarro2022). On the other hand, the mayor of Fallera in 2018, Rocío Gil, became the leader of the Spanish nationalist party Ciudadanos (Maceda, Reference Maceda2018). Thus, we can see that fallas can produce more or less implicit political ninots, depending on the orientation of their leaders, which generally ends up always being linked to the conservative side. The presidents of fallas are generally high-income and conservative people, especially in traditional fallas.

The construction of the “foreign enemy”: Fallas and Catalanophobia

The rite of the fallas has been constructed since the end of the Franco regime to reinforce collective identity, understood as an organic whole that must defend itself against supposed external aggressions, thus reinforcing a conservative and organicist vision of regional and local identity (Peris, Reference Peris2014; Rius-Ulldemolins et al., Reference Rius-Ulldemolins, Gisbert and Vera2021). The festive culture is thus elaborated with a purifying idea of traditional action against “the others” and the symbolic (and material) expulsion of dissidents from identity and territory. This was the case of a journalist from the countercultural magazine Ajoblanco, who was expelled from Valencia after publishing a satirical article about the Fallas (Ariño Villarroya, Reference Ariño Villarroya2009). This can also be seen in the Fallas world’s criticism of the ideologue of political Valencianism, Joan Fuster, in the 1970s, which called for his expulsion from Valencian lands, accusing him of being a “traitor” to traditions and regional identity as defined in the Fallas sphere (Ariño Villarroya, Reference Ariño Villarroya1992). And this tendency to use ritual to construct the political and ethnic enemy has also been visualised in relation to Catalan nationalism in the 2010s, especially during the rise of independence in the 2010s, as we can see in the following photos (see Figure 1, 2 and 3)).

Figure 1. Monuments and ninots of the fallas with Valencian regionalist (blavero) and Catalanophobic discourses (2018).

Source: Photo 3. Falla San José de la Montaña. Three ninots, one with the Valencian flag. Caption: who rules in our flag is the blue of the sea (symbol of the anti-Catalan regionalism), the flag of the north so despicable can go to hell (…) we, the Valencians, will win. Photo 4: Falla Azcàrraga Ferran el Catòlic. Catalan flag with a pirate skull and a WC.

Figure 2. The characterisation of Catalan politicians in the Fallas as perverse or untrustworthy as a form of criticism in the Fallas.

Photo 1 - Artur Mas, President of the Generalitat de Catalunya in the WC. Photo 2 - Falla de Martí l’Humà. Severed head of the President of the Generalitat de Catalunya Carles Puigdemont, in allusion to the myth of Samson and Delilah. Photo 3 - Image of Jordi Pujol and Artur Mas, presidents of the Generalitat de Catalunya presented as thieves with money in their hands, 2015. Photo 4 - Representation of Oriol Junqueres, leader of Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya with the pro-independence flag and depicted as a prisoner in uniform and chains, 2018. Photo 5 - Falla l’Antiga de Campanar 2016. Motto: “Malèfics”. Artist: Alejandro Santaeulalia. Theme: Catalanism and independence of Catalonia. Font: Cendra Digital. Photo 6 - Independentista as alien from Mars Attacks, 2019.

Figure 3. The characterisation of the political enemy as a woman or a homosexual as a form of criticism in Fallas.

Photo 1: Ninot representing Carles Puigdemont, former president of the Generalitat de Catalunya disguised as a Geisha with Catalan pro-independence flags (2024). Photo 2: Poster of the Falla with the text: “Such a valuable vase of Spanish ceramics has been broken with little skill by this arrogant man” (2024). Photo 3. Ninot by Toni Fornés for the Falla Pedro Cabanes-Conde Lumiares.

As we will see below in relation to Catalonia or the nationalists, they are seen as an external enemy and an internal enemy. Thus, the manipulation of symbols and discourses used is very similar to the rhetoric of the ultra-right and fascism regarding social, ethnic, racial and male chauvinist minorities. Specifically, dehumanisation and hate speech is carried out in a number of ways: a) by depicting them as perverted, untrustworthy or money-hungry beings; b) by depicting them in degrading situations such as defecating or being in prison; c) by depicting the body in degrading situations such as defecating or being in prison; and d) by depicting the body in a degrading way. c) through the representation of the body with animals that are considered perverse in the biblical narrative or other mythical stories (pigs, snakes, rats…); c) through their assimilation with the female gender as something negative in a vision of patriarchal and misogynist machismo; and d) through the representation of homosexuality and these relationships as humiliating acts with a homophobic discourse. Thus, festive culture is not exempt from hateful or xenophobic discourses and, on the contrary, it can be used to construct the image of the external enemy, the Catalan, and the internal enemy, the Valencian, as we will see below.

The portrayal of Catalan leaders as perverse, degraded or evil

It should be noted that the representation of people with money in their hands is one of the typical schemes used by totalitarian ideologies such as Nazism to represent those considered enemies and parasites of the nation. (Fajardo, Reference Fajardo2021; Nayeri, Reference Nayeri2019) as developed in processes that preceded the development of the genocides of the 20th century (Mann, Reference Mann2009).

Thus, in the image of the Catalan leaders, they appear in situations that are negative for the dignity of the individual (taking a shit) or in humiliating disguises and contexts (in prison wearing a prisoner’s uniform), or they are represented by means of popular culture myths or images (see Figure 2 and 3). They are also associated with the stereotype of the greedy Catalan (Sangrador, Reference Sangrador1996) - a stereotype similar to that of the Jew depicted by the Nazis in the exhibition “The Eternal Jew” (AFFA, 2014)- by President Pujol, who wears traditional Catalan dress and claims to want to “steal money” above all else. On the other hand, the image of the head being cut off and exposed to scorn (the classic myth of Samson and Delilah) is used. Or commercial pop culture myths are used, with the villains of Gru or Mars Attacks, to attack Catalan nationalism and present it as “evil” in an amusing but effective and educational way.

Representation of Catalan political leaders as men, women or homosexuals

One of the commonplaces in the Fallas is to characterise those who are elevated to the category of political enemies as enemies of Spain or of Valencia as women or homosexuals. A humorous perspective that is clearly sexist and homophobic, considering that this characterisation makes them less worthy and an object of public ridicule.

It is worth noting that the ninot of 2024, which depicts the Catalan pro-independence leader Carles Puigdemont sodomising the socialist prime minister Pedro Sánchez as a form of ridicule, is linked to the homophobic culture characteristic of the far right, in which political enemies are portrayed as effeminate or homosexual (Cortés Ibáñez, Reference Cortés Ibáñez2014). This ninot was exhibited for several days in the Museum of the Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències, received extensive media coverage and was considered by the media as a “star” ninot due to its media impact and attention in an exhibition open to the underage public and frequently visited by schoolchildren (Maroto Reference Maroto2024). (Maroto, Reference Maroto2024). Although it was criticised by the LGTBI defence collective Casa Lambda for being homophobic, which was awarded the “inventiveness and grace” prize by the Fallas organisation (Miralles, Reference Miralles2024).

Catalan leaders portrayed as “impure animals”

Another way of creating the dehumanisation of the enemy and the unassimilable other is to characterise them as animals in general and as rats in particularFootnote 5. In the case of the Fallas, in 2021, the political leaders of the independence movement, some of whom were in prison at the time, were described as rats with the following captions: “The most pestilent rats in terms of corruption are the ones we now see leaving prison”. / “An epidemic has infected a part of the nation; independence has come by seeking separation”.

As we can see in Figure 4, the leaders of Catalonia are repeatedly depicted as pigs, dogs, snakes and rats, a grammar similar to that of anti-Semitism and the discourse of ethnic hatred against cultural minorities. This is the case of the Falla of the Convent of Jerusalem, that has been the protagonist of one of the most resounding cases of Catalanophobia, representing the presidents and councillors of the Generalitat de Catalunya first as pigs in 2018 and then as rats in 2021Footnote 6. In the latter case, the representation is like the anti-Semitism of the early 20th century by the Nazis of the Jews in the 1930s (Nayeri, Reference Nayeri2019). The president and ministers of the Generalitat de Catalunya are depicted as rats, and it is therefore specified that another president leads the rats, referring to his voters and supporters. It is therefore not a criticism of a political elite, but of an entire collective, with Catalan independence supporters characterised as the animal considered most impure, as far right propaganda did against ethnic minorities (AFFA, 2014).

Figure 4. Representations of Catalan political leaders as snakes, pigs, dogs and rats.

Photo 1: Representation of the President of the Generalitat de Catalunya Carles Puigdemont as a snake. Caption: “The Catalan leaders (…) are resting in Soto del Real (Spanish prison where the Catalan political leaders were imprisoned on remand)”. Falla Bisbe Amigó, 2017. Source: photo by the author. Photo 2 - Falla Convent Jerusalem 2018. Motto: “Per naturala”. Artist: Pere Baenas. Source: Cendra Digital. Photo 3 - Falla Isabel la Católica-Cirilo Amorós- Hernán Cortés. Independència. Source: photo by the author. Photo 4, Jordi Pujol, ex-president of the Generalitat de Catalunya as a rat. Falla Convent de Jerusalem-Matemàtic Marzal de València Photo 5: Puigdemont as a flute player leading the Catalan pro-independence rats throwing stones and Molotov cocktails. Falla Convent de Jerusalem-Matemàtic Marzal.

For this reason, these ninots were criticised by the Compromís leader Joan Baldoví, who recalled that “this nomenclature had already been used by the Nazis to refer to the Jews” (Fajardo, Reference Fajardo2021). This statement hasn’t provoked any reflection or self-criticism on the part of the leaders of the Falla; on the contrary, they threatened the deputy with legal action. In this way, far from atoning for the dehumanisation of the leaders of the national minority and generating hate speech on the networks, the leaders of the Fallas of the Special Category supported the Falla and asked Baldoví for a correction, while at the same time the Right (PP, Ciudadanos and VOX) took the opportunity to describe him as an enemy of the Fallas. We must also remember that these fallas were exhibited in public during all the festivities and received public money in the form of subsidies for their production. The fallas did not receive any criticism from the organisation or the local government, on the contrary, they received the support of various right-wing and far-right councillors. (Fajardo, Reference Fajardo2021).

The phobia of Valencian nationalism: the Fallas ritual against the “internal enemy”

The Fallero ritual has been revealed as a powerful tool to reproduce the social and political order, first by the dictatorship and then by the elite that inherited power in the democratic period, grouped in conservatism and Spanish regionalism (Peris Reference Peris2014). The Fallas field is plural, and in a recent survey of the Valencian population, 38% of those participating in the fallas identified as left-wing and 25% as centrist (Ajuntament de València, 2024). Meanwhile, 36% of participants identified as right-wing—a figure slightly higher than that of the general population, which stands at 30%. However, this data does not include information about the leadership of the fallas (Presidents and Executive Boards), for which there are various indications of connections with right-wing and far-right organizations (Maceda, Reference Maceda2018; Rius-Ulldemolins et al., Reference Rius-Ulldemolins, Gisbert and Vera2021).

Moreover, the local left-wing government elected in 2015 has tried to change the structures, regulations and organisational dynamics, despite the potential for conflict. In its electoral programme, the Coalició Compromís (Valencian Left Coalition) advocated a rigorous management with the direct participation of the Fallero world (breaking with the representative and clientelist system), sustainable and with the desire for a progressive transformation of the festival, which they considered too stagnant in its inertia and conservative parameters (Coalició Compromís 2015). However, attempts to make progress towards greater democratisation and transparency in management, as well as social inclusion and gender inequality, have been met with fierce resistance from the leadership of the Fallero world, who have not hesitated to use homophobia or anti-Catalanism to paralyse the reforms (Díaz-Solano, Rius-Ulldemolins and Gisbert-Gracia, Reference Díaz, Rius and Gisbert2024). A particular target of criticism was the left-wing government’s councillor for festive culture, Pere Fuset, who was repeatedly depicted in the Fallas as a warrior, an absolute monarch, a boxer, and so on.

Pere Fuset tried to promote the use of the Valencian language in the celebrations, to democratise the Fallas and make them more transparent through a new Fallas Congress and a sociological survey. All these initiatives were boycotted with open hostility by conservative sectors (Garsan Reference Garsan2017). These sectors, led by Interagrupación de Fallas (an organisation created in 2010 under the mandate of Felix Crespo, PP councillor for Popular Culture and Fiestas), became a factor of attrition for the local left-wing government, acting as an extension of the Spanish right-wing, which sees the fallas sector as a pillar of its strategy of political and social hegemony, threatened by the decomposition caused by the numerous cases of corruption (Rius-Ulldemolins, Flor and Hernàndez-Martí, Reference Rius-Ulldemolins, Flor Moreno and Hernàndez i Martí2019). A sector that presents the confrontation as a war (see figure above) and uses the fallas as a strategy to delegitimise the government, using the ritual to exclude them from the ritual and from power (see Figure 5) (“they want to cut off his head”, reads the poster in photo 4), with disqualifications as traitors to the region and the fallas (“he wants to undo everything that is ours”).

Figure 5. The representation of Pere Fuset, Councillor for Festive Culture 2015-2020, as an “enemy” of the Fallas.

Photo 1 - Pere Fuset in a trench. Caption: Fuset: -Is he the enemy? Can he stop the war? Falla 178. Photo 2 - This black bishop… orange (Compromís colour) betting on making country, wants to undo without warning all that is ours. Photo 3- Pere Fuset, boxing against the JCF. Falla 184. Caption: The right hook is in full form, Fuset doesn’t know what to do anymore, where to hit. Photo 4 - Falla Plaça del Pilar 2017. Motto: “Que li tallen el cap”. Artist: Paco Torres. Source: the authors and Cendra Digital.

In this way, the arrival of the progressive government has been described in a derogatory way and with a perspective focused on extreme right-wing discourses. This is what we are talking about in “Compromís en el Régim”, a hoax that shows the mayor of the city giving the fascist salute, the councillor for festive culture, Pere Fuset, and also the eagle of San Juan with Francoist links, in which elements defended by Compromís appear, such as traffic lights, feminism (see Figure 6), Catalanism and the very symbol of the progressive coalition. In this way, it trivialises Francoism and his totalitarian regime with a democratic government, thus trivialising fascism and its repression. It also equates the reformist policies of the democratic parties with authoritarian policies, a criticism that fits in with the right-wing and far-right discourse on the alleged “pro-green dictatorship” (see VOX 2024).

Figure 6. The portrayal of Compromís leaders as Catalanists, dictators and traitors.

From left to right and from top to bottom. Photo 1 - Vicent Marzà, Minister of Education of the Generalitat Valenciana 2015-2022. Falla Quart-Palomar. Photo 2: -Mónica Oltra, Vice-President of the Autonomous Government 2015-2022., the Councillor for Festive Culture, both from Compromís (Valencianist left). Caption: Betrayal of traditions. Photo 3 - Poster of the Falla Guillem de Castro-Triador (2018). Slogan: Compromís en el Règim. Source: Sketch.

As we can see in Figure 7, in various fallacies, the top leaders of Compromís insist on being represented with the Catalan flag (considered as a symbol of the external enemy, as we have analysed) in order to characterise them as internal enemies. This has been a constant feature of the various fallas, in which the progressive coalition in local or regional government has been delegitimised, despite the fact that its links with these ideas have never been explicit since it came to power. Mónica Oltra, at the time leader of Compromís and vice-president of the Generalitat Valenciana, is thus presented as a traitor to traditions, despite the fact that she is an active member of a Fallas commission. The Minister of Education at the time is also accused of being a traitor because he is a Catalanist, on the pretext of granting subsidies to a Valencian association for the promotion of education in the Valencian language. In this case, the discourse against the external enemy is combined with the discourse of hatred against the enemy culture, the promotion of the Catalan and Valencian languages and even the traditional Catalan dance, the sardana.

Figure 7. Percentage of votes for Vox in València city in the 2019 general election and dominant fallas (Category 1A and Especial).

Source: own elaboration based on Junta Central Fallera and València City Council Statistics. (Ajuntament de València 2024).

Fallas culture, hate speech and right-wing extremism: from street violence to local government

The relationship between part of the Fallero world and the right and the extreme right is particularly evident in the Fallero elite. Thus, it is worth highlighting the positive correlation between Fallas from the Sección Especial and Primera A and the vote for the extreme right-wing party VOX (Figure 8). The fallas of the Special Section and the First A Section, the most important ones, are mainly located in the most central districts of the city. Basically, in the areas of Roqueta, Russafa, Ciutat Vella and Mestalla (Aragó). In the same way, the concentration of votes for VOX, even though the economic factor of the neighbourhood takes precedence over the economic factor, means that the VOX discourse can be present in the most frequented fallas in Valencia.

Figure 8. Instrumentalisation of the fallas by the extreme right of VOX (2021-2024).

Source: own elaboration based on the account of X VOX Valencia City.

Furthermore, part of the Fallero sector is an active agent in the refoundation of the far right, starting from ultra-Spanish, anti-Catalanist and Blavero positions (Flor Reference Flor2011). It has been revealed that a Fallero chronicler was the organiser of the illegal concentration of the far right against the Valencianist demonstration of 9 October 2017. This demonstration of Valencian nationalism, held annually to commemorate the Day of the Valencian Country, took place after the referendum on self-determination in Catalonia on 1 October 2017. In this context, a group linked to the Fallas networks organised and promoted an appeal against the Valencianist demonstration, arguing that it was “a provocation and humiliation of the Valencians and their identity” to which it was necessary to respond against the “Catalan nationalists”, who were identified as the enemies of Spain and the Valencians, with a classic rhetoric of the enemy within (Cantarero Reference Cantarero2019). A rally attended by the president of the Interagrupación de Fallas, Jesús Hernández Motes, the leader of the Fallas, Pepe Herrero, and violent far-right groups, in which several left-wing Valencianist demonstrators and journalists covering the event were verbally and physically assaulted and the stall of the Catalan newspaper La Jornada was smashed (El diario, Reference El diario2017). Despite the fact that this counterdemonstration and the organised aggression led to 26 people being charged with serious crimes against rights and freedoms - known as hate crimes against minorities - and that among the accused are several members of the Fallas as organisers, this has not led to the resignation or the opening of any investigation or disciplinary proceedings within the Fallas commissions. On the contrary, those responsible, such as the president of the Interagrupación de Fallas, have been confirmed in their positions (Cantarero Reference Cantarero2019).

On the other hand, VOX has become a continuation of the Catalanophobic and anti-nationalist Valencian discourse. According to the deputy, the culture of the left Valencianist government was based on mocking our traditions, our fallas and our religion’ (VOX 2024). Certainly, in this case, his discourse has largely abandoned Blavero regionalism for Spanish nationalism, but he continues to focus on promoting the idea of a division between “good Valencians” and “bad Valencians”, between good falleros and critics of the falleros, between good falleros and critics of the falleros. between the good falleros and the critics whom they consider to be “anti-falleros”, against whom they deploy a discourse of hate, because they are supposed to be enemies of traditions and bad Spaniards and Valencians (cf. VOX 2024).

Thus, we can see how some fallas in the VOX timeline adopt a discourse close to that of the extreme right: 1) At the VOX 2021 political meeting, a falla with the image of ecologists and feminists was made and burned at the end of the event, symbolically appropriating the ritual. 2) Mayor Ribó was accused of attacking the fallas because he defended the criticism of the Falla Convento de Jerusalén, which called the Catalan independentists rats. Therefore, VOX takes advantage of this to defend this attack and to contrast an “us” - defenders of the Fallas - against a “them” - enemies of the Fallas, with the phrase: “Ignorant and mediocre mayors and deputies will pass, but the Fallas will always be there, because they belong to the Valencians” (VOX X report /13-09-2021). 3) The Falla Cuba Literato Azorín receives the visit and support of VOX by adopting anti-feminist and pro-life positions. b) The leaders of VOX posing in the ninot of the Falla that represents the leader Puigdemont sodomising the President of the Government Pedro Sánchez under a Catalan flag (03-02-2024). As we can see, the extreme right, in alliance with a section of the Fallas, is using them to attack their political enemies and turn festive culture into a space for cultural struggle.

On the other hand, in VOX’s representations of politicians, their image is not distorted, nor are they shown as animals or in transvestite or ridiculous situations. On the contrary, they are portrayed as political representatives who carry out actions that are considered morally correct from an extreme right-wing perspective (see Figure 9): a) defending the Spanish army in the face of protests by pacifists who painted a tank pink, which VOX criminally denounced, and b) bombing the Ribó government, which is portrayed as a corrupt mafia. In both cases, the VOX councillors appear in the guise of their own guilt, which serves as a reason for them to claim and be proud of their work in the local government.

Figure 9. Political use of VOX’s depiction of far-right leaders (2023-2024).

Source: own elaboration based on the account of X by Monica Gil (Councillor for Festivities and Traditions) and Juanma Bádenas (Second Deputy Mayor and VOX spokesperson).

A discourse that, although it is not predominant, is present in the ritual of the fallas and legitimises this discourse and attitude through its presence in the public space for weeks. It should also be noted that neither the commissions nor the JCF, which organises the juries that evaluate all the fallas, have ever made negative observations about this type of cadafalcs and ninots; on the contrary, they have continued to reward and subsidise them with public money.

Conclusions

Festival culture offers a space for popular creativity and critical reflection on power and elites. As such, it has been analysed, valued and recognised as an intangible heritage. Since the 2000s, however, there has been a growing awareness of the dark side of festive culture, which euphemistically inherits the legacy of racist and anti-Semitic discourses of the early 20th century. This is the case of certain carnivals in Europe or the festive culture of the Fallas in Valencia. Its conservative and nationalist Spanish re-reading after the Franco regime and the transition has persisted and developed as a culture of hatred, against the external enemy, the Catalans and their political leaders, and against the internal enemy, the Valencians. This discourse is not limited to certain leaders, but is represented by the typical Catalan dress, the flag, the language, that is, it is a discourse of hatred towards the whole collective. And it uses ethno-racial hatred, dehumanising and animalising images, as well as machismo and homophobia. This discourse does not come from a single fault line, but from several, some of which, like the Convento de Jerusalem, are very central and well connected to the political and economic elites. Likewise, the local and Madrid media tend to echo these discourses uncritically these discourses, just as the local and autonomous right-wing rulers are currently supporting and covering them in the name of freedom of expression.

Various anti-racis organisations have challenged this very discourse of freedom of expression as freedom to develop hate speech. The consideration as intangible heritage and popular culture is no longer understood as a carte blanche to develop hate speech. As we have seen, the ruling collectives of the Fallas, especially some of the elite commissions, have not contributed to what the UNESCO Convention foresees in its Article 2 to promote “mutual respect between communities, groups and individuals” (UNESCO 2003). Certainly, we can assume that the majority of Falleros do not belong to this political tendency, but the fact that this type of representation and discourse has been developed repeatedly, and that people with this political tendency are high officials of the organisation, suggests not only a lack of concern, but also connivance with this discourse, which the political leaders have not condemned, but rather have financed and allowed to be exhibited and publicly promoted in municipal spaces. In this sense, although the Fallas can be described as neo-traditional culture with a significant dimension of popular participation, in this case, a sector of the festival’s leadership—acting in collusion with political elites—uses the Fallas to promote an ideological struggle and to construct an exclusionary vision of Valencian local identity directed against social minorities. In this regard, rather than being popular culture in the sense of the culture of the working classes, the Fallas may be understood as an exercise of domination by a status group from the middle and lower-middle classes, who deploy their capital of autochthony to dominate the local political scene and disseminate exclusionary discourses against those they consider their socio-political enemies—having a significant impact in the local and national press and on social media accounts promoted by the far right (Maroto, Reference Maroto2024; Miralles, Reference Miralles2024).

Finally, with the emergence of the extreme right and its entry into government, this political instrumentalization as a tool for generating hate speech has become more explicit and direct. A radicalisation of hate speech that casts further doubt on its character as a cultural manifestation that respects UNESCO’s requirement that intangible heritage should integrate the values of respect for minorities, gender and sexual diversity, and democratic political plurality, and not contribute, as it does now, to hatred between communities.

Financial support

Universitat de València. UV-INV_AE-3674253.