Introduction

Populism is on the rise. In many countries, populist actors have become very successful and may even gain government representation (Ellger, Reference Ellger2024; Roberts, Reference Roberts2022; Spoon & Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2019; Vachudova, Reference Vachudova2021). As such, the right-wing populist party, Party for Freedom, became the largest party during the 2023 Dutch parliamentary elections with a vote share of 23.7 per cent. In Sweden, the right-wing populist party, Sweden Democrats, became the second largest force during the 2022 parliamentary elections and even entered a government coalition for the first time. And, in Italy, Giorgia Meloni, the right-wing populist party leader of Brothers of Italy, became Italy's first female Prime Minister in 2022.

Often, the success of populist parties is associated with democratic backsliding or challenges towards liberal democracy (Albertazzi & Mueller, Reference Albertazzi and Mueller2013; Rummens, Reference Rummens, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017; Urbinati, Reference Urbinati2019). However, despite populism being studied from various angles (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Kaltwasser2018; Mudde, Reference Mudde2004; Taggart, Reference Taggart2000), it is still not clear why and when different voters support populist candidates. One major element often associated with the success of populist actors is their discursive strategy (Aalberg et al., Reference Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Stromback and Vreese2016; Aslanidis, Reference Aslanidis2018) as populist communication can have enormous effects on citizens' opinions and their political behaviour, including voting (Bos et al., Reference Bos, van der Brug and de Vreese2013; Hameleers et al., Reference Hameleers, Bos and de Vreese2017; Mueller, Reference Mueller2016; Reinemann et al., Reference Reinemann, Stanyer, Aalberg, Esser and de Vreese2019; Wirz, Reference Wirz2018). Although some recent studies focus on the effect of blame attribution in populist discourse (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Sheets and Boomgaarden2018, Reference Bos, Schemer, Corbu, Hameleers, Andreadis, Schulz, Schmuck, Reinemann and Fawzi2020; Busby et al., Reference Busby, Gubler and Hawkins2019) or on which attitudes or pre-dispositions affect the populist vote (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Andreadis, Anduiza, Blanusa, Corti, Delfino, Rico, Ruth, Spruyt, Steenbergen, Littvay, Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Kaltwasser2018; Hieda et al., Reference Hieda, Zenkyo and Nishikawa2021), little is known about how elements of (non-)populist discourse causally affect voting behaviour.

Theoretical and empirical considerations suggest that blame attribution is not the only decisive element of populist discourse. Research also considers people-centric rhetoric (Meijers & Van Der Velden, Reference Meijers and Van Der Velden2022; Rooduijn & Akkerman, Reference Rooduijn and Akkerman2017) and language simplicity (Bischof & Senninger, Reference Bischof and Senninger2018) as commonly used tools of populist rhetoric. Considering these still understudied elements when studying the effect of populist discourse on citizens, this article asks what makes the populist appeal effective.

Focusing on varying discursive elements, I attempt to answer this research question by looking at different elements of populist and non-populist messages, testing their effect on vote choice. To this end, I conducted an extensive voter experiment in Germany between December 2020 and January 2021 (N = 3325).Footnote 1 The forced choice vignette experiment asked respondents to cast their vote choice between two candidate statements. These statements varied across the three discursive elements of blame attribution, people-centrism and language complexity to capture different populist and non-populist messages.

Contrary to prior research with observational data, the results show that populist attitudes are not the main driver for populist voting but that blame attribution is the most decisive driver for vote choice. Blame attribution was measured with three ideological variants: left (blaming capitalists), right (blaming refugees) and neutral (blaming politicians). Ideology expressed through blame attribution corresponds highly with voters' vote intentions. This shows that ideology seems more decisive than populism in explaining vote choice. Simple language, on the other hand, in contradiction to its theoretical considerations, has an overall negative effect on vote choice. People-centrism has a positive effect on vote choice in most statement configurations. The results show that people tend to like politicians who create an in-group feeling and consider themselves part of the voter group. Surprisingly, the neutral version of blame towards politicians drives vote choice across all voter groups not only voters with populist attitudes or vote intentions. These results suggest an overall dissatisfaction with the functioning of political systems and the work of politicians. The results also hold irrespective of voters' ideological preferences. Further, they are in line with other experimental studies showing that individuals' ideology preferences determine vote choice instead of populist attitudes (Castanho Silva & Wratil, Reference Castanho Silva and Wratil2023; Dai & Kustov, Reference Dai and Kustov2022; Neuner & Wratil, Reference Neuner and Wratil2022). However, this study goes beyond these conjoint experiments as it not only tests people-centrism and anti-elitism as elements of populism but adds even more attributes often associated with populism, such as blame attribution and simple language. Still, this analysis shows that various populist elements have a minimal effect on an individual's voting decision, showing that ideology is still the main driver for vote choice.

Even though the study was only conducted in Germany, results may also be applicable to other European countries with similar political systems. As Hauwaert and Van Kessel (Reference Hauwaert and Van Kessel2018) as well as Reinemann et al. (Reference Reinemann, Stanyer, Aalberg, Esser and de Vreese2019) have shown, populist voters across several countries in Europe display similar characteristics and respond to similar patterns. Therefore, we can assume that the main results from this survey experiment also travel beyond Germany.

As such, this analysis contributes to the crucial debate on populism, its rising popularity in recent years, and the challenges it poses towards representative democracy. More broadly, this analysis contributes to the debate on vote choice and how certain discursive elements can influence voting behaviour. It provides a causal link between (non-)populist discourse and how it affects voters, showing that various voter groups respond surprisingly positively to similar language patterns.

Populist discourse: Theoretical considerations and hypotheses

Researchers have discussed many concepts when defining populism. Main research strands include populism as a strategy (Weyland, Reference Weyland2001), populism as an organisational form (Roberts, Reference Roberts2006) or a cultural style (Ostiguy, Reference Ostiguy, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017). Most prominently, scholars have discussed the ideational approach established by Mudde (Reference Mudde2004). Especially when analysing discursive elements of populism or populist communication strategies, scholars agree on core features included within the ideational approach (Hunger & Paxton, Reference Hunger and Paxton2022). As such, this article is also based on the main assumptions of the ideational approach and combines them with ideas of how they can be enacted through language.

As such, discourse is not the only element that matters when defining populism. However, scholars agree that it is impossible to understand populism without analysing its discursive patterns (Aslanidis, Reference Aslanidis2018). Given that specific language patterns are crucial for populism, they can be considered relevant for the success of populists. Therefore, we must understand how these language patterns affect voters and, more precisely, vote choice, if we aim to understand why populist actors have become more successful around the globe.

In this paper, I reconceptualise populism in terms of three elements displayed in populist discourse: people-centrism, ideologically toned blame attribution, and language complexity. The first two elements consider the content side of the discourse, whereas the last element focuses on a stylistic element. I chose to analyse a combination of these three elements as they are referenced as key features in the literature on populism based on populism as discourse and the ideational approach. However, the three elements are often discussed separately instead of connected to each other. Therefore, I explain people-centrism, ideologically toned blame attribution, and language complexity and discuss how the interplay of these three elements creates the theoretical foundation of populism.

People-centric rhetoric

Even though there is no unique and fully encompassing definition of populism, current scholarship from Western democracies largely agrees on the ideational approach towards populism (Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2019). This approach classifies the world of politics into a dualistic view of good versus evil. As such, populists claim to be the true democrats who defend the will of the common and ‘good’ people against the corrupt and ‘evil’ elites (Canovan, Reference Canovan1999; Mudde, Reference Mudde2004). Following the populist logic, the people and their sovereignty are the core of democracy, which is threatened by the elites; the people are considered the basis of a good society (Albertazzi & McDonnell, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2008; Mény & Surel, Reference Mény and Surel2002).

This definition captures the recognisable features scholars agree on, that is, the ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mentality. This understanding is transmitted through their rhetoric and plays a major role in how populists communicate worldwide. I will refer to this rhetorical strategy in this article as people-centric rhetoric. This rhetoric strategy underlines that populist actors use ‘us’ to talk about the common people for whom they understand themselves as advocates. Following the populist worldview, the common people are usually classified as a sovereign, homogeneous, pure and virtuous group (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014). Populists aim to create an in-group feeling that common people can feel part of. Consequently, they use the reference of the ‘other’ to create an opposing entity. This reference helps the ‘us'-group or in-group to demarcate itself better, but it also creates a ‘them'-group or out-group that can be opposed and blamed for societal or political problems. Populist actors align these groups with their populist view of a dualistic world. This worldview is transmitted vociferously through their rhetoric, underlining that people-centric rhetoric is a significant element of populist discourse.

Even though using people-centric rhetoric or references to the ‘us'-group is a strong characteristic of populist discourse, populist actors do not uniquely apply it. Mainstream actors also use people-centric rhetoric in their messages to create a feeling of proximity to their electorate. Thus, people-centric rhetoric can be understood as a discursive element that populist and mainstream actors employ. Nevertheless, populist actors tend to over-emphasise this element and speak to people who are more responsive to it. Thus, I expect a positive effect of people-centric rhetoric in political messages across all voter groups. However, populist actors benefit even more from the use of people-centric rhetoric. This leads to the following hypothesis.Footnote 2

People-Centrism Hypothesis

H1

People-centric rhetoric positively affects vote choice in general, but it has an even stronger effect among individuals with populist vote intentions or attitudes.

Blame attributive language

Besides the fundamental division of ‘us’ versus ‘them’, scholars argue that populist actors exploit social identity frames to emphasise in- and out-groups even more (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Schemer, Corbu, Hameleers, Andreadis, Schulz, Schmuck, Reinemann and Fawzi2020). Commonly, populist actors aim to underline in-group favourability and out-group hostility. Using discursive elements, they create a subjective sense of unfair treatment among people of the in-group enacted through people of the out-group or society (Elchardus & Spruyt, Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016). Identifying a group of people by creating an opposing group of people makes them feel more attached to their own group, as it creates a clear identification within group boundaries.

According to social psychological theory, populist actors apply psychological micro-mechanisms that create identity through discourse. Thus, I rely more precisely on social identity theory in this analysis. Commonly, social identity theory argues that an in-group creates a positive assessment of its own group in demarcation from the other (out-)groups. Additionally, the theory points out that in-group members usually share emotional involvement and achieve social consensus within the group (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Jost and Sidanius2004), which unites them as group members.

In relating these assumptions to people who are prone to populist ideas, research shows that such individuals often have problems with finding a positive social identity (Spruyt et al., Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck2016). As the world has become more complex, people have struggled to find their role and identity in it – or as Rostbøll (Reference Rostbøll and Rostbøll2023) puts it: ‘many people have lost their formerly secure feelings of identity and status, and they are increasingly turning their frustration at their loss toward the political system by supporting populist parties and leaders’ (Rostbøll, Reference Rostbøll and Rostbøll2023, p. 2). Huddy (Reference Huddy2001) emphasises that it is, therefore, important to consider identity choices. She emphasises that choosing to be part of a group voluntarily increases self-esteem and group cohesion leading to higher in-group identification but also more discrimination against out-groups (Huddy, Reference Huddy2001, p. 139) (see also Perreault & Bourhis, Reference Perreault and Bourhis1999 and Turner et al., Reference Turner, Hogg, Turner and Smith1984). Thus, when people choose to support a populist party or movement, it is because they have lost part of their former identity or feel disappointed by an in-group they used to be part of. These negative feelings unite them, and let them create a new identity – an identity of disappointment in the current political system or, more broadly, society in general. Populist actors are aware of their supporters’ disappointment. They use this disappointment strategically to form a new identity and in-group among these people.

As such, blame attribution is added as an additional layer to people-centric rhetoric. It forges identity through an in-group versus out-group understanding of the world. The most generic form of blame attribution is blame against politicians or, more broadly, against the political system. Commonly, all populists blame politicians as it helps populist actors to create a generic out-group that can be held accountable for the malfunctioning of society. Usually, blame against politicians is detached from any ideological placement. Therefore, blame attribution against politicians can be seen as a neutral version of populist blame attribution and can serve to detect the general functioning of populist rhetorical strategies. However, blaming politicians without using any form of people-centrism is not generically populist. Mainstream actors can also blame other political elites in their discourse. Therefore, it is essential to highlight that populist rhetoric consists always of both elements, people-centrism as well as anti-elitism (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004).

As blame attribution is enacted through language, it can be considered to produce framing effects (Busby et al., Reference Busby, Gubler and Hawkins2019). Thus, it is important to notice that framing effects can be enforced through pre-dispositions, such as values that accompany blame-attributive language. Individuals’ underlying attitudes or values can affect how much certain frames influence them. Chong and Druckman (Reference Chong and Druckman2007) point out that ‘individuals who have strong values are less amenable to frames that contradict those values’ (Chong & Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007, p. 111). If individuals are juxtaposed with the different arguments of an issue, they commonly choose the alternative closer to their pre-existing values and underlying principles (Sniderman & Theriault, Reference Sniderman, Theriault, Sniderman and Saris2004). This can be related to populist rhetoric and, more precisely, blame attribution. Individuals with underlying populist attitudes will accordingly respond more to frames that build up on these pre-dispositions. As well, individuals who share populist attitudes will favour frames from populist actors that apply these rhetorical strategies. Thus, individuals who share populist attitudes or vote intentions should be more likely to vote for a candidate who blames political elites for societal problems. This leads to the following hypothesis.Footnote 3

Politician Hypothesis

H2a

Blame attribution against politicians positively affects vote choice for people with populist vote intentions or attitudes.

So far, I have discussed populist actors as one unity. However, as outlined earlier, populism is often attached to a host ideology. Populism is commonly combined with radical right and radical left ideologies (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2012). Even though, it is essential to note that centrist parties can also adopt populist strategies, such as the Five Star Movement in Italy. However, in this analysis, I will focus on populist actors and their supporters from the radical left and the radical right, as these are the parties that most commonly adopt populist stances (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014).

As such, blame attribution varies depending on the host ideology of a populist actor. By referencing certain in- and out-groups, populist actors can direct their ideological positioning. As left-wing (populist) actors usually apply a discourse that centres around social class, they often create an out-group that consists of the economic elites or simply ‘the rich’. Right-wing (populist) actors, on the other hand, apply an ethic and nativist-guided discourse. They usually target immigrants and/or refugees as an out-group and blame them for the malfunctioning of various societal problems. Thus, ideological differences can be emphasised and even strengthened by blaming a chosen other.

However, the success of blame attribution fostered by populist parties on the left or the right will correlate with voters’ ideological pre-dispositions, just as attributing blame to political elites does too. Consequently, placing blame on immigrants and/or refugees will mostly affect people who already have existing right-wing attitudes or vote intentions. Correspondingly, attributing blame to economic elites will attract individuals with left-wing attitudes or vote intentions. This leads to the following two hypotheses:Footnote 4

Migration Hypothesis

H2b

Blame attributions against refugees positively affect vote choice only for individuals who share right-wing populist vote intentions or attitudes.

Economic-Elite Hypothesis

H2c

Blame attribution against economic elites positively affects vote choice only for individuals who share left-wing populist vote intentions or attitudes.

Populist style

A long tradition in research on populism has pointed out that a decisive characteristic of populist actors is communicating simply (Aalberg et al., Reference Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Stromback and Vreese2016; Canovan, Reference Canovan1999; Mudde, Reference Mudde2004). This communication style is moreover enforced through a populist worldview and political strategies, or, ‘populism's tendency not only to communicate in a simple and direct manner but also to offer solutions that are direct and simple’ (Moffitt & Tormey, Reference Moffitt and Tormey2014, p. 387). Populism often provides a simple and attractive alternative for the more complex and contradictory ideas of liberal democracies (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007). As such, populist actors apply a simple view of the world, which is often based on in- and out-group thinking, resulting in ‘us’ versus ‘them’ rhetorical strategies. Additionally, they position themselves as the grounded alternative for the current political or economic establishment. Thus, people should perceive populists as the simple and maybe even crude, but honest, alternative to the ruling elites that common people perceive as being too pretentious. Populists' simple communication style signals these political strategies and ideas. Hameleers et al. (Reference Hameleers, Bos, de Vreese, Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Stromback and Vreese2016) underline that ‘the communication style of populists distinguishes itself by using simple and direct language, one-liners, and provocative statements directed toward the elite and other out-groups’ (Hameleers et al., Reference Hameleers, Bos, de Vreese, Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Stromback and Vreese2016, p. 147).

Next to qualitative evidence, scholars have also attempted to measure the language complexity of populist actors quantitatively. Bischof and Senninger (Reference Bischof and Senninger2018) show that manifestos of populist parties use simpler language than non-populist parties. Decadri and Boussalis (Reference Decadri and Boussalis2020) even provide causal evidence and emphasise that MPs who change parties adapt their language complexity depending on whether they are part of a populist party or not. MPs of populist parties use significantly simpler language than MPs of non-populist parties. In the U.S. context, Oliver and Rahn (Reference Oliver and Rahn2016) have shown that Donald Trump used simpler language than his competitors in the 2016 presidential election. Other empirical results, however, reveal a more mixed picture. By analysing the speeches of political leaders, McDonnell and Ondelli (Reference McDonnell and Ondelli2020) show, for example, that populist leaders sometimes even use more complex language than non-populist leaders.

Nevertheless, given the idea that simpler language leads to politics that are easier to comprehend and that voters would rather vote for someone whom they can understand as they can more easily hold that politician to account (Bischof & Senninger, Reference Bischof and Senninger2018), I will still consider simple language as having a generally positive effect on all voters, and voters with populist attitudes in particular. The theoretical considerations about populist behaviour enforce these assumptions even though the results regarding their usage are contradictory. This leads to the final hypothesis.Footnote 5

Simple-Language Hypothesis

H3

Simple language positively affects vote choice in general, but it has an even greater effect on people with populist vote intentions or attitudes.

Germany as a case and sample strategy

The survey experiment was implemented in Germany, which can be considered an ideal case because of the recent success of populist actors in this country. Currently, both a left-wing and a right-wing populist party are represented in the German Bundestag: Die Linke (The Left)Footnote 6, which is considered a left-wing populist party, and Alternative for Germany (AfD), which is a right-wing populist party (Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2019). Thus, I studied individuals who support populist parties with opposing ideological positions in a comparative setting. Additionally, the German party system covers a broad range of parties' ideological positions, including the extreme positions covered by the Left and the AfD, but also, in general, more moderate ideological positions like the Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) or Social Democrats (SPD).

In addition, the mixed electoral system in Germany has allowed me to frame the candidate choice experiment in the form of candidate voting decisions (see Neuner & Wratil, Reference Neuner and Wratil2022). In German national elections, citizens cast two votes. The first vote is for a direct candidate. Through the so-called Erststimme, voters directly select a candidate in their electoral district following a first-past-the-post formula. The second vote is for a party and is commonly referred to as Zweitstimme. This survey experiment models the vote of the Erststimme and creates a somewhat realistic scenario.

Other features that we should consider when looking at Germany as a case are possible regional differences as well as voter characteristics. Germany's history may drive regional differences as the country was divided into East Germany (German Democratic Republic – GDR) and West Germany (Federal Republic of Germany – FDR) until 1990 with two different political systems. Electorally, populist parties are currently more assertive in East Germany than in West Germany (Loew & Faas, Reference Loew and Faas2019). Significantly, the AfD became very successful in Eastern German federal states like Saxony.

When looking at voter characteristics, we can observe that ideological proximity, as well as populist attitudes, characterise voters of both parties. Hansen and Olsen (Reference Hansen and Olsen2022) argue that anti-immigrant ideology is a stronger predictor for AfD vote choice than socio-demographic variables. They also find that negative attitudes towards political elites are increasing the probability of voting for the AfD. Similar results are found for voters of the Left. Goodger (Reference Goodger2023) finds that also policy proximity to left-leaning policies predicts vote choice for the Left. These results are in line with other studies when analysing support for left-wing and right-wing populist parties in Europe (Hauwaert & Van Kessel, Reference Hauwaert and Van Kessel2018; Reinemann et al., Reference Reinemann, Stanyer, Aalberg, Esser and de Vreese2019). As such, the results presented in the analysis are not only relevant to the German case but can also travel beyond that and may be especially applicable to other countries in Europe with similar political systems.

In total, 3325 respondents were surveyed. The sample is drawn from a large online panel provided by the survey company Lucid. Lucid provides access to a pool of people across Germany with varying ages and educational backgrounds, ensuring a somewhat representative sample of the German population. The mean age of the final sample is 45.3, with 51.7 per cent female and 48.3 per cent male respondents. The survey was conducted between mid-December 2020 and mid-January 2021. I also asked respondents about essential characteristics. As such, I was able to control for regional differences between East and West Germany as well as educational variation.

Research design: Paired vignette experiment

To shed light on the effect of populist and non-populist rhetorical strategies and which elements are the driving factors, I conducted a paired vignette experiment in Germany between December 2020 and January 2021 with a sample size of 3325 respondents. This gave me 9975 vignette ratings, as each respondent had to answer three choice tasks. Paired vignette designs follow the same logic as paired conjoint experiments and allow researchers to estimate the causal effects of multiple treatment components (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). Compared to conjoint experiments, vignette designs are presented in a text form instead of a table format (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hangartner and Yamamoto2015). Therefore, this design seemed most suitable to test the effect of political statements with varying populist and non-populist rhetorical strategies. Respondents read two short paragraphs with varying attribute levels in this design specification. The paired vignette design is particularly beneficial for answering the stated research question of how elements of (non-)populist discourse causally affect voting behaviour. It allows the treatments to vary across different discursive elements. Thus, combinations of rhetorical and stylistic features in political statements can be modelled and their causal effect tested. A translated English version of the questionnaire is presented in online Appendix C.Footnote 7 Below, I will describe the dependent and independent variables and possible moderators.

Dependent variable: Vote choice

In this newly designed survey experiment, respondents were presented with three pairs of fictional candidates' statements that use varying populist rhetorical strategies and language complexities. These pairs were randomly drawn from a pool of 16 differently framed statements. Then, respondents were asked to state for which candidate's statement from the pair they would rather cast their vote. Therefore, respondents' vote preference is the dependent variable following the logical structure of conjoint/vignette experiments.

Respondents were also asked to state how much they could imagine voting for each candidate in the pair. Thus, respondents could state whether it is very unlikely that they would vote for a candidate (1) or very likely that they would vote for a candidate (7).Footnote 8 The task was repeated three times for each respondent. To minimise associations of existing candidates as well as their parties and to include statements that might not occur in reality, I study vote choice for candidates rather than parties and do not provide party labels (see Neuner & Wratil, Reference Neuner and Wratil2022).

Independent variable and treatment: Statement variations

To measure the effect of the three elements of populist discourse (people-centric rhetoric, blame attributive language and populist style), different fictional statements of politicians are framed. All statements are focused on the worsening of Germany's current labour market situation. This issue is well suited to analyse various discursive elements on the effect of vote choice. First, the labour market is a less politicised issue by radical left or radical right actors in comparison to topics like immigration or crime. In fact, political actors from both sides of the ideological spectrum highlight the current labour market situation in similar ways and with similar intensity. This allows me to frame statements that evoke comparable interest among voter groups from both sides of the political spectrum. Second, the labour market provides us with a national and European dimension (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008) and has been proven as a suitable policy issue for survey experiments that test the effect of different populist frames (Hameleers et al., Reference Hameleers, Bos and de Vreese2017). As the labour market situation affects a country's economic well-being, it produces common interest among various groups of people.

Even though all statements focus on the worsening of the labour market, they apply different rhetorical strategies to emphasise populist and non-populist language as well as left-wing, right-wing and centrist positions. As populist rhetoric is commonly emphasised through people-centric language that opposes an out-group (which could be political elites, economic elites (left-wing populism) or refugees (right-wing populism) depending on the populists' host), ideology, the attribute levels of the statements vary among these dimensions. The statements include phrases like ‘our situation’ and ‘we’ to frame people-centric rhetoric. Non-people-centric rhetoric, on the other hand, employs neutral frames like ‘the situation’. Blame attribution is used to model left-wing and right-wing rhetorical strategies. Populist actors commonly use blame attribution to evoke opposing feelings by citizens against elites (Busby et al., Reference Busby, Gubler and Hawkins2019; Hameleers et al., Reference Hameleers, Bos and de Vreese2018). Thus, left-wing populism is modelled through people-centric language, attributing blame to economic elites. Right-wing populism is modelled through people-centric language that attributes blame attributions to refugees.Footnote 9

To illustrate how people-centrism and blame-attributive language are used commonly in populist rhetoric, I selected an example from an excerpt of a parliamentary speech given by Gottfried Curio, MP for the AfD in the German Bundestag on 22 November 2017:

[…]The influx with low-skilled individuals plus planned family reunification does not stabilise the labour market and pension system; instead, it increases unemployment and reliance on social benefits, especially in an increasingly digitised working world. The goal should be to increase the birth rate. An activating family policy, as demanded by us, would take priority instead of replacing our own people. This means Billions for our families instead of alimentation and integration for non-permanent or currently difficult placeable migrants […] (Deutscher Bundestag, 2017, p. 173)

On the one hand, the quote shows how a right-wing populist MP uses people-centric rhetoric, that is, ‘our own people’ and ‘our families’. On the other hand, it shows a real-world example of how a right-wing populist party blames refugees/migrants for challenging the labour market. Therefore, the example shows how the survey experiment captures real-world discussions held in the German parliament (Bundestag).Footnote 10

In addition, the different combinations of the statements are framed on two occasions: once applying average language complexity and once applying simple language complexity. Language complexity is assessed through readability scores. Readability scores allow one to estimate how complex a text is to read. I apply the LIX readability score developed by Björnsson (Reference Björnsson1968). This measure is beneficial for German text (Anderson, Reference Anderson1981). Moreover, Bischof and Senninger (Reference Bischof and Senninger2018) show that it is very applicable in German-speaking political contexts. LIX calculates the complexity of a text by calculating the sum of the average sentence length and the percentage of long words (more than seven letters). In detail, LIX is calculated in the following way:

with W indicating the number of words in a text and S being the number of sentences. Thus, the first part of the equation indicates the average sentence length. 7W indicates the number of words with seven or more letters. Lower LIX scores display less complex texts. Readability scores between 25 and 70 display reasonable language complexity for the German language. Scores below 25 are considered very easy, around 40 are expected and more than 55 are difficult (Bischof & Senninger, Reference Bischof and Senninger2018, p. 479).

For the survey experiment, statements that are framed using simple language complexity display a LIX score of between 26 and 35. Statements with average language complexity display a LIX score of between 43 and 55. I abstained from using (over)complex language in the statements as the average language complexity in the German parliament has a score of 48 on the LIX score and only very occasionally above 55 on the LIX score, especially in the last legislative period (Kittel, Reference Kittel2023). The LIX scores for each statement are presented in online Appendix E. I also report the commonly used Flesch-Kincaid score and the SMOG.de score that is adopted for the German language. Both scores show similar results to the LIX score.

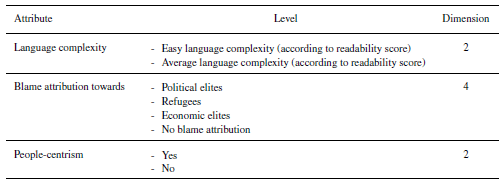

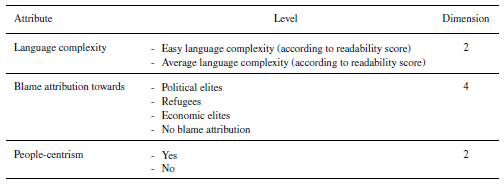

In total, 16 statements are framed, varying across the three attributes: language complexity, people-centrism and blame attribution. An overview of all attributes and their corresponding levels is presented in Table 1. The complete list of the English version of statements is presented in online Appendix C.1.

Table 1. Paired vignette design

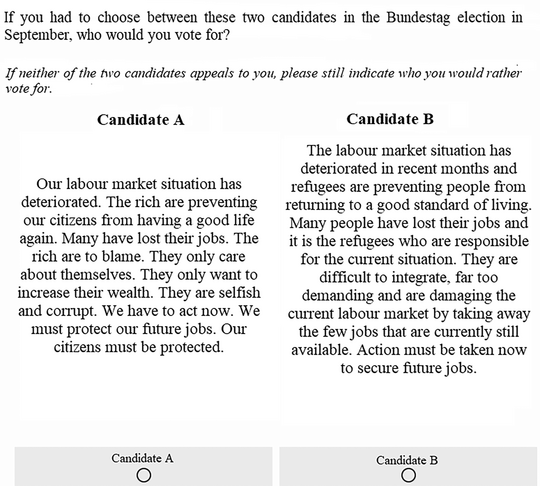

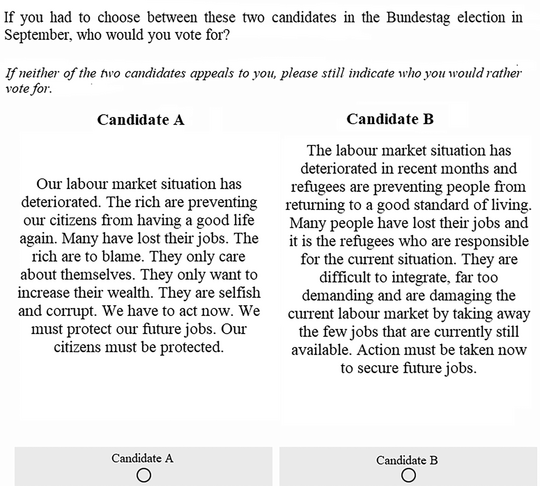

Figure 1 shows the English translation of statements presented to respondents who participated in the online survey experiment. It shows two randomly drawn combinations out of the 16 statement variations. Respondents had to choose either Candidate A or Candidate B. The original German version of these two statements is presented in Figure 1 in online Appendix D. The statement of Candidate A displays simple language complexity, people-centrism and places blame on economic elites (Statement No. 6). The statement of Candidate B shows average language complexity, no-people-centrism and places blame on refugees (Statement No. 11 in online Appendix C.1, section on Treatment Combinations).

Moderators: Political attitudes and personal characteristics

Following the stated hypotheses, I am also interested in whether varying statements have a different effect depending on respondents' populist attitudes and ideological positions. Accordingly, it is assumed that ideological as well as populist attitudes moderate the effect of language simplicity. Thus, respondents are asked different questions to measure their ideological attitudes, vote intentions and populist attitudes.

To measure respondents' ideological attitudes and vote intentions, I used classical ideological placement measures as well as vote intention questions. Thus, respondents were asked for whom they would vote if elections were to take place today. This serves as the main moderator variable throughout the main analysis. However, I also ask respondents to position themselves on an ideological scale from 0 (extreme left) to 10 (extreme right). Respondents who indicate a value below or equal to 2 are considered left-wing voters. If they also display a thin populist factor above 1, they are considered left-wing populists. A value of above or equal to 8 displays a right-wing position. If respondents also display a value above 1 for the thin populist factor, they are considered right-wing populists. A value in between these extremes is regarded as a centrist position, which can, however, also be combined with thin populist attitudes. Results with the ideological placements are presented in online Appendix G.

To measure respondents' underlying thin populist attitudes, I referred to a battery of eight political claims based on claims used by Neuner and Wratil (Reference Neuner and Wratil2022) in a similar setting. Initially, the claims were introduced by Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014) and have also been validated by other studies (see Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020). Online Appendix C presents the complete list of political claims. Respondents had to identify on a 1 (fully agree) to 4 (fully disagree) Likert scale how much they coincide with each political claim. Respondents could also decide not to answer any of the given claims. For the analysis, the data were recoded from 2 (fully agree) to −2 (fully disagree) with 0 for no information. Afterwards, a factor analysis was conducted to create a single factor that describes if a respondent is considered populist or not. Values from the eight batteries were combined to create this factor. If the factor shows a value above 0, the person is considered to have underlying thin populist attitudes. If the factor falls below 0, the respondent is considered to have no thin populist attitudes. This measure was used and validated in a similar survey experiment by Neuner and Wratil (Reference Neuner and Wratil2022).

Ultimately, I decided to use vote intention instead of thin populist attitudes in the main analysis. As Wuttke et al. (Reference Wuttke, Schimpf and Schoen2020) propose, ‘populist attitudes should be treated as an attitudinal syndrome that is more than the sum (or average) of its subdimensions’ (p. 372). Following their advice, vote intention seems to be the overall accurate choice as it incorporates whether people have a preference for populist actors or not, a point that sits at the core interest of this analysis. Results based on the populist attitudes scale are presented in online Appendix G.

Finally, respondents were also asked about certain demographic characteristics. They were asked to report their age, educational background, occupation and area of residency within Germany.Footnote 11 These characteristics were asked to generate a representative sample of the German population.

Results

The average voter

First, we will look at the effect of individual and combined rhetorical elements on the average voter. As such, I will analyse which rhetorical elements, individually or in combination, increase a candidate's likelihood of being voted for. These results will show which rhetorical elements the average voter responds to the most.

As paired vignette experiments follow a similar logic to conjoint experiments, they can be analysed using similar estimation techniques. To analyse the results of this survey experiment, I follow the recent advice by Leeper et al. (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020) and present the results as marginal means (MMs) instead of the commonly used, in conjoint/vignette experiments, average marginal component effects. MMs are especially beneficial when presenting subgroup results of conjoint/vignette experiments (see Neuner & Wratil, Reference Neuner and Wratil2022). As this analysis aims to detect the effect of language complexity across different subgroups of people, MMs are considered the best strategy to present the results. The interpretation of MMs in a forced paired vignette design is straightforward. It gives the probability that a profile will be chosen given that the attribute value x is present, marginalising across all other attribute values.Footnote 12

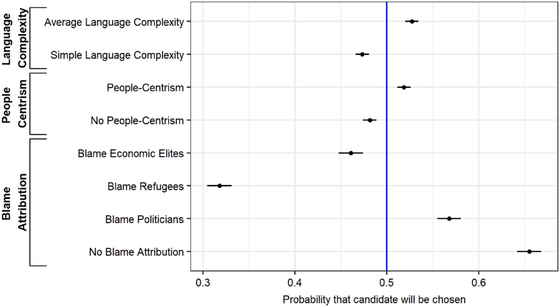

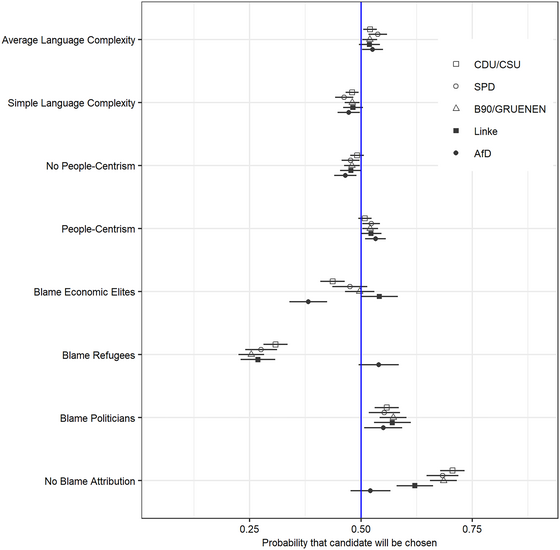

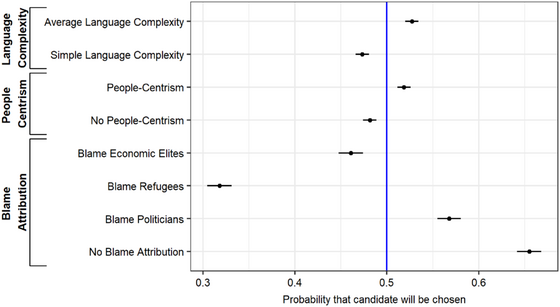

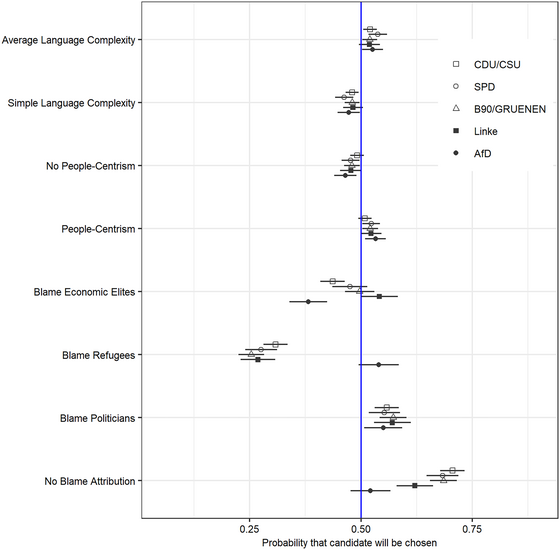

Figure 2 displays MMs using the full sample for all attribute levels. The blue vertical line shows the 0.5 probability of a candidate being chosen. Thus, the estimate on the left of the line indicates that the attribute level negatively affects the chosen candidate. The estimate on the right of the line instead positively affects candidate support. This shows that populist framing has different effects across the general voting-eligible population in Germany. It is also demonstrated that people-centric language has, on average, a positive effect on candidate vote choice, supporting the people-centrism hypothesis (H1). Furthermore, it shows that the average voter favours candidates that use average language complexity compared to simple language complexity. This contradicts the simple-language hypothesis (H3). The highest positive effect on candidate vote choice is achieved when no blame is attributed. Thus, on average, people are not attracted by blame-attributing rhetoric. However, blaming politicians also has a positive effect on vote choice. This already hints towards mixed results for the blame attribution hypothesis listed under H2.

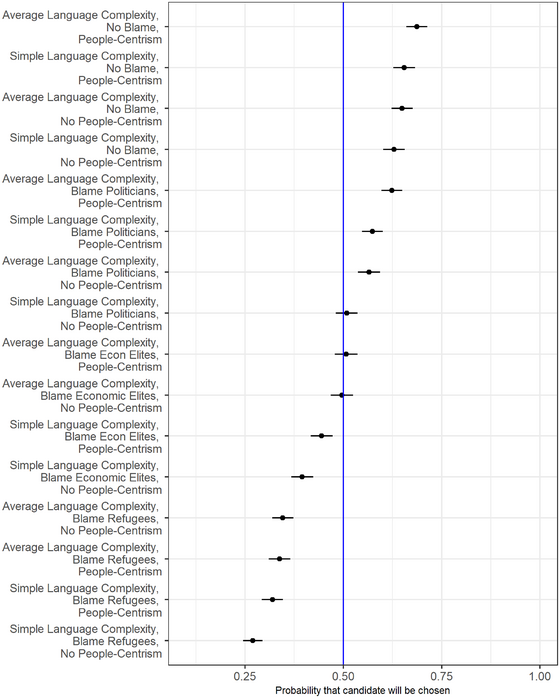

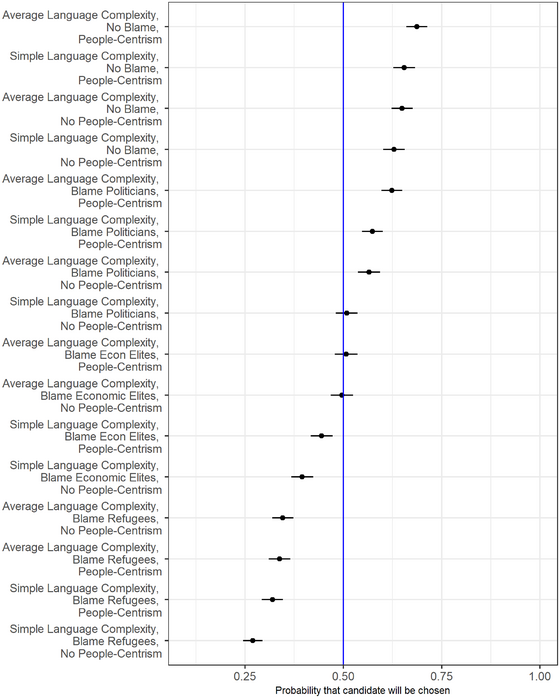

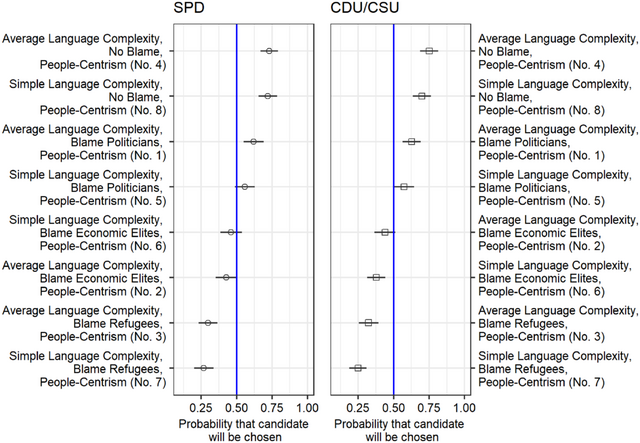

Figure 3 also shows MMs for the full sample. However, instead of the individual attribute levels, it displays the interacted attribute levels, therefore creating a more realistic view of which message combinations work best. Also, this shows which populist messages work best as they usually constitute a combination of the three rhetorical elements of people-centric rhetoric, blame attributive language and populist style. Thus, Figure 3 shows individuals' voting decisions for all 16 political statements.

The results also show that if we do not control for any underlying attitudes, individuals, on average, favour statements that do not attribute any blame, that use people-centric rhetoric and average language complexity. However, statement combinations attributing blame to politicians, whether these use people-centric rhetoric or not, score among the second highest combination types and positively affect vote choice. As before, statement combinations that blame economic elites had either no or a negative effect on vote choice, irrespective of whether other elements were included or excluded in the political message. The same holds for statements that blame refugees. They produce an overall negative effect on vote choice. In addition, the results show that simple language always has a more negative effect than average language complexity, no matter which framing valence is used. On the other hand, people-centrism always has a more positive effect on vote choice.

The results also hold when we control for geographical differences. In online Appendix G (Figures 5 and 6), I show a sub-group analysis of citizens living in the regions of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the former Federal Republic of Germany (FDR). I control for regional differences as the AfD is electorally stronger in federal states belonging to the former GDR. However, there are no statistically significant results between the two regions. The results show that people living in the former GDR and the former FDR regions do not react differently to the various discursive elements. We can only observe a slightly more positive effect on blame towards refugees for citizens living in the former GDR. However, these results are minor and not statistically significant. As such, the results hold across regions and are not driven by geographical patterns.

Populist voters versus non-populist voters

Now, we will turn to the interaction effect between different statement elements and people's ideological preferences, namely their vote intentions. Therefore, depending on people's vote intention, I will compare which statement combinations increase candidates' vote share. As such, we can analyse if populist voters (AfD and Linke voters) are likelier to vote for candidates that employ more populist and ideological radical rhetorical elements.

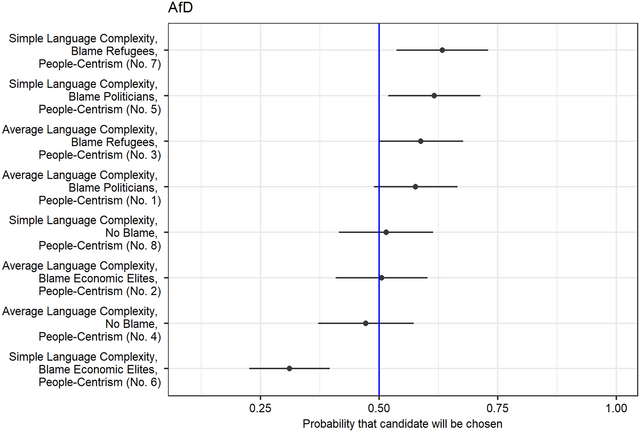

Figure 4 shows the full sample divided by individuals' vote intentions on the survey day. Most interestingly, the results show that blame attribution seems to be the most decisive driver of vote choice. The results show that blame against refugees in a political message positively affects right-wing populist voters in Germany (AfD voters). For all other voters, it has a negative effect. Similar results can be observed for political messages that blame economic elites. They drive the vote choice for left-wing populist voters (Linke voters) but have a zero to negative effect on all other voters. This shows confirmation for H2b and H2c. Blame against politicians has a surprisingly positive effect for all voter groups. Thus, voters generally respond positively to political messages that blame politicians. This contradicts hypothesis H2a. No blame attribution, however, scores highest among non-populist party voters. Also, the results show that people-centrism and average language complexity positively affect all party voters on average. This supports the people-centrism hypothesis (H1) and refutes the simple-language hypothesis (H3).

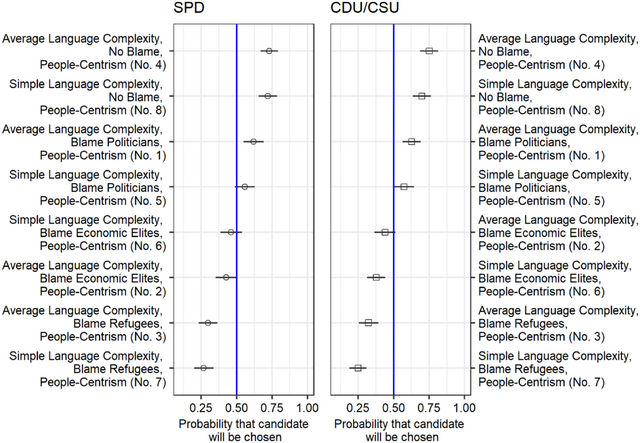

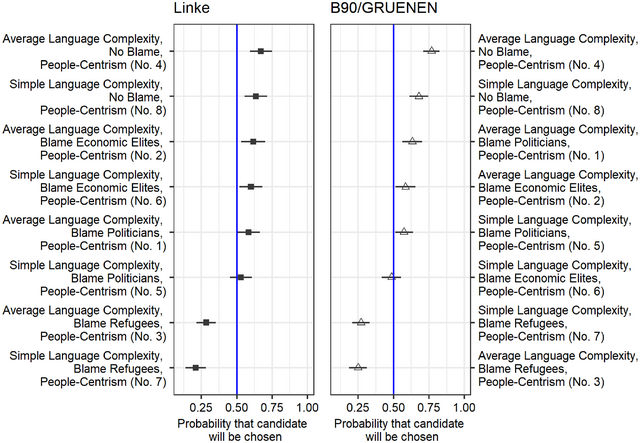

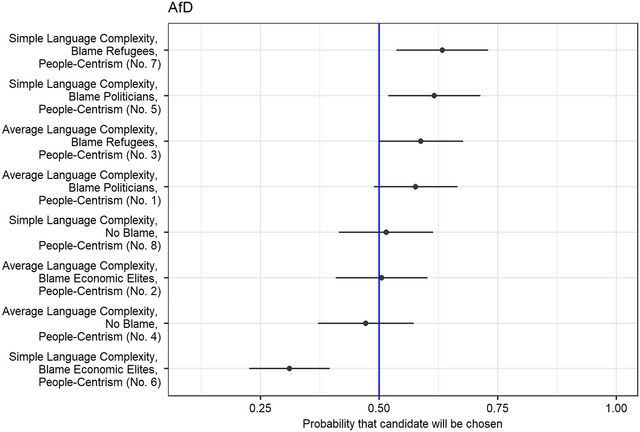

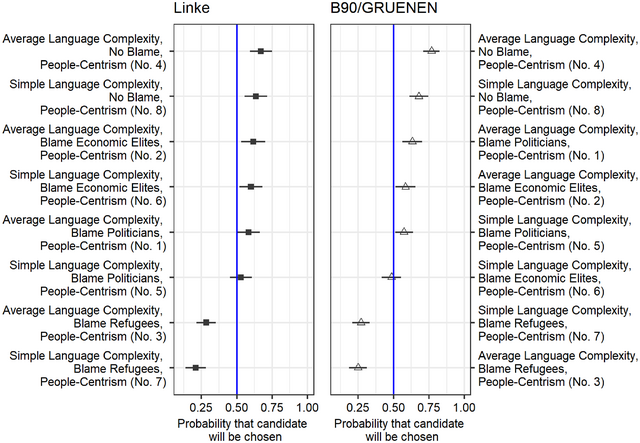

Finally, we will look at message combinations, individuals' underlying attitudes, or vote intentions. This produces a close, realistic assessment of how underlying ideological attitudes affect how people respond to political messages. The results for message combinations, including people-centric rhetoric, are presented in Figures 5–7. Figures including all statement combinations (with and without people-centric rhetoric) are presented in online Appendix F (Figures 2–4). The results are split into three figures (five graphs) due to better graphical representation. The most interesting results are that blame attribution against refugees again has a positive effect only for people who intend to vote for the AfD (right-wing populist party). However, in combination with people-centrism and simple language, this political statement has the highest positive effect on people who intend to vote for the AfD. This shows that it is not an individual component of a political statement but rather the combination of all three populist discursive elements that make people with corresponding attitudes turn towards these parties. This is supported even further when we look at statements that do not include people-centric rhetoric. For these statement combinations (see online Appendix F, Figure 4), AfD-oriented people have a lower chance of casting their vote for that candidate and become even negative for the combination of simple language, blame against refugees, and lack of people-centric rhetoric. This shows that this particular combination seems to affect vote choice. As such, it is important to consider various aspects and their effect when discussing populist discourse.

The results of the three figures also show that the combination of average language complexity, blame against politicians and people-centrism produces a highly positive effect on candidate vote choice among all voter groups. These results are rather surprising, as they contradict the politician hypothesis (H2a) that assumes blaming politicians will only positively affect voters with populist attitudes or vote intentions. But also for SPD and CDU/CSU voters, blame attribution scores positively in many statement combinations (see Figure 5). In addition, they show that individuals who do not cast a populist vote respond positively to elements of populist discourse. People, on average, seem to blame politicians for societal problems. Blaming economic elites or refugees, on the other hand, depends on the corresponding underlying attitudes of the individual or, more precisely, their vote intention.

These results are also confirmed when we look at populist attitudes instead of vote intentions. As a robustness check, I created thin and thick populist attitudes scales following Neuner and Wratil (Reference Neuner and Wratil2022). Online Appendix G shows results for people displaying left-wing populist attitudes, right-wing populist attitudes or centrist no attitudes (online Appendix G, Figures 9 and 10). The results show that the preferred blame attribution is highly connected to people's ideological preferences. Further, the results confirm that simple language is usually less preferred than average language complexity in all statement combinations. When looking at the division between populist and non-populist people without controlling for any ideological preferences, we can observe that no blame or blame towards politicians has a positive effect on either group, even though blame towards politicians scores higher among people with populist attitudes (online Appendix G, Figures 9 and 10).

In addition, a sub-sample of N = 1748 respondents was analysed. The sub-sample was created through an attention check that was asked of respondents and only included respondents who read all statements that were presented to them. For the attention check, respondents were asked to state to whom each of the six candidates attributed blame. Thus, respondents were asked six times to indicate whether blame was attributed to political or economic elites, refugees or nobody. Respondents who answered at least five of six questions correctly were included in the sample. This measure considers that respondents could have had one slip of the pen but, in general, read all of the statements.Footnote 13 Results of the sub-sample are nearly equivalent to the full sample results.

Discussion and conclusion

Populist messages consist of various discursive elements that make them successful among various voter groups. However, not every element is equally successful for every person. This depends very much on people's underlying attitudes and vote intentions. While previous observational work could not detect causal claims on the effect of discursive strategies on vote choice, this article contributes to this gap by showing how different voter groups are attracted to different discursive strategies. The analysis gives new insights into how particular discursive elements causally affect vote choice and, more precisely, which populist elements also affect voters who ultimately would not intend to vote for a populist party. Thus, this experiment showed the following four results.

First, it showed that people-centric rhetoric works among all voter groups; it does not solely appeal to populist voters. This may be due to the pleasant feeling of being part of a group. People-centric rhetoric incorporates people who usually like to belong somewhere. These results also show that, overall, people prefer a more inclusive language in comparison to technocratic communication. As such, people seem to be more attracted by a populist discourse which includes them as actors compared to technocratic discourse which employs a top-down approach (Caramani, Reference Caramani2017). As these results hold for all voter groups, they also provide important implications for non-populist and mainstream actors. We can imply that overall, people seem to prefer a bottom-up approach in which they are included in the discourse instead of a top-down approach in which politicians claim to be ultimate experts who have complete answers to problems. Therefore, non-populist actors can benefit from using a more inclusive and people-centric rhetoric in their communication with voters.

Second, the results show that the ‘neutral’ version of blame attribution – namely towards politicians – increases vote choice among all voter groups. These are rather surprising results, as blame-attributive language is considered an element of populist discourse. Even though no blame attribution in candidates' statements usually generates the highest likelihood of a candidate being elected by non-populist voters, these results show that populist dynamics and elements of their rhetorical strategies are effective for a large group of voters. People seem to be ‘discontent, not only with politics but also with societal life in general’ (Spruyt et al., Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck2016, p. 335). Thus, certain populist discursive elements affect even non-populist voters more quickly than expected. However, more research is necessary to reveal if non-populist actors are aware of these mechanisms, and use them, or if a general increase in dissatisfaction and distrust in politicians has led to these results.

Third, voters' ideological preferences have a higher effect on vote intentions than underlying populist attitudes. These dynamics are often understudied in the discussion in research on populism. Nevertheless, this experiment has shown that underlying ideological attributes have an effect if people respond to targeted blame attribution and define their vote choice more than just their general populist attitudes. This may also open up discussions on whether populism and ideology from the left and the right should be more often discussed as co-existing instead of neglecting one or the other. Populist rhetoric is, after all, very much primed by its host ideology.

Fourth, the paper showed that against all expectations, simple language has a negative effect on vote choice in nearly all political statement combinations and for all voter groups. These results contradict the expected result but align with similar results found by In Bischof and Senninger (Reference Bischof and Senninger2021). They hint at the fact that people may prefer politicians who speak with average language complexity, as they assign them more competence. However, this can also be specific to the German case and German language peculiarities.

As it is not only relevant to understand what effect certain discursive elements have on vote choice but also how long-lasting and persuasive they may be, we can relate the results to research on persuasion effects in political communication. Research has shown that persuasion strategies in campaigns often have strong but short-lived effects on voting behaviour (Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Gimpel, Green and Shaw2011). Interpreting these findings in relation to this survey experiment leads us to assume that (populist) discursive strategies may affect voters in the short run and can influence election results. Discursive strategies may not change voters' underlying ideological preferences in the long run, though. If we consider that blame attribution towards refugees or capitalists only positively affected voters that already displayed underlying right-wing or left-wing ideological attitudes, respectively, we can assume that other factors may affect ideological change for voters. In a broader scope, these results imply that underlying ideological preferences primarily drive vote choice. As such, populist actors may not convince people who do not already share their ideology to vote for them by just applying a blame-attributive discourse. This shows that language does affect people. However, instead of changing attitudes quickly, language instead reinforces them. Nevertheless, these are only interpretations based on earlier research results. More research testing the long-lasting effects on certain discursive elements would be necessary to receive binding results.

Even though the survey experiment was only conducted as a single case study in Germany and the German language displays unique linguistic characteristics, results can travel beyond that case. As discussed earlier, scholars have shown that similar cross-country experiments testing voting behaviour and populist attitudes are often similar across Western European countries. Given that party systems across Europe, especially Western Europe, are relatively similar, there is little reason to believe these results do not hold beyond Germany.

Analysing different discursive elements of populist and non-populist discourse and their effects on various voter groups has shown that language can be used strategically to affect vote choice. It has also shown that peoples' underlying attitudes greatly affect how a message is perceived. A general dissatisfaction with the functioning of the political systems – or at least how politicians work – seems to lead to a general acceptance of blaming political elites for societal problems. Emerging research shows, too, that all kinds of parties use anti-elite rhetoric strategically, often depending on their electoral circumstances (Licht et al., Reference Licht, Abou‐Chadi, Barbera and Hua2024). Future work should focus further on the interplay of parties' strategic use of anti-elite rhetoric and how this affects voting behaviour. This will help to disentangle the challenges advanced democracies may face in the future.

Acknowledgements

I thank Geoff Allen, Mariana Carmo Duarte, Bruno Castanho Silva, Amy Catalinac, Denis Cohen, Sven-Oliver Proksch, Simon Hix, Ellen Immergut, Alexandru Moise, Simon Munzert, Costin Ciobanu, Konstantin Vössing and Christopher Wratil as well as the three anonymous reviewers for providing constructive feedback and helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript as well as the research design. Also, I would like to thank participants at the MPSA Conference 2023, Düsseldorf Lunch Talk 2022, Political Behaviour Colloquium EUI 2022, ECPR General Conference 2021 and the CIVICA PhD Panel 2020 for their comments and engaging discussions. The survey experiment was funded by the Early Stage Researcher Grant from the European University Institute, Villa Sanfelice, 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole, Italy.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Ethics statement

The survey experiment received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the European University Institute on 14 December 2020. It was also pre-registered on EGAP and can be accessed through this link https://osf.io/7utsx.

Conflict of interest statement

In submitting my manuscript, I have carefully followed the instructions of the authors. Therefore, I have no conflicts of interest to declare, and the manuscript is currently not under review elsewhere.

Data availability statement

Data from the survey experiment and the reproducible code for the analysis are available on OSF Registries through the following link: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/G7V6S.

Online Appendix

Appendix A Deviations from the Pre-Analysis Plan

Appendix B Real World Examples - Populist Statements

Appendix C Full Questionnaire - English Version

Appendix D Treatment Combination of Candidate Statements - German Version with Screenshot from the original Experiment

Figure 1: German candidate choice question (dependent variable) as presented to the respondent in the survey, Statement 6 (left-hand side) and Statement 11 (right-hand side) in Appendix C.1.

Figure 1. English version of the candidate choice question (dependent variable), statement 6 (left-hand side) and statement 11 (right-hand side) in online Appendix C.1.

Appendix E Readability Scores

Table 1: Readability Scores According to Treatment-Vignette

Table 2: Readability Scores According to Treatment-Vignette

Appendix F Full Results of Interaction Levels

Figure 2: Interactions of Attribute Levels: Marginal Means by Parties, SPD and CDU/CSU in Comparison

Figure 2. Marginal means of attribute levels without subgroup division.

Note: Marginal means are displayed with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Figure 3: Interactions of Attribute Levels: Marginal Means by Parties, Linke and B90/GRUENE in Comparison

Figure 3. Interactions of attribute levels for all voters: marginal means.

Note: Marginal means are displayed with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Figure 4: Interactions of Attribute Levels: Marginal Means by Parties, AfD

Figure 4. Marginal means by party groups.

Note: Marginal means are displayed with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Appendix G Robustness Checks

Figure 5: Marginal Means for Citizens Living in the Former GDR vs. Citizens Living in the Former FDR

Figure 5. Interactions of attribute levels with statement numbers (only showing people-centric statements): marginal means for SPD and CDU/CSU voters.

Note: Marginal means are displayed with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Figure 6: Interaction of Attribute Levels: Marginal Means for Citizens Living in the Former GDR vs. Citizens Living in the Former FDR

Figure 6. Interactions of attribute levels with statement number (only showing people-centric statement): Marginal means for Linke and B90/GRUENE voters.

Note: Marginal means are displayed with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Figure 7: Interactions of Attribute Levels (only Statements with People-Centric Rhetoric): Marginal Means for Populists and Non-Populists

Figure 7. Interactions of attribute levels with statement numbers (only people-centric statements): Marginal means for AfD voters.

Note: Marginal means are displayed with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Figure 8: Interactions of Attribute Levels (only Statements Without People-Centric Rhetoric): Marginal Means for Populists and Non-Populists

Figure 9: Interactions of Attribute Levels (only Statements with People-Centric Rhetoric): Marginal Means for Left-Wing Populists, Right-Wing Populists and NonPopulists

Figure 10: Interactions of Attribute Levels (only Statements without People-Centric Rhetoric): Marginal Means for Left-Wing Populists, Right-Wing Populists and NonPopulists

Figure 11: Marginal Means by Ideology Grouping (without controlling for populism)

Figure 12: Marginal Means by Populists and Non-Populists Groups

Figure 13: Marginal Means for Populists and Non-Populists

Appendix H Results: Exploratory Hypotheses

Figure 14: Marginal Means for Emotions vs. No Emotions

Figure 15: Marginal Means by Emotional Feelings

Figure 16: Marginal Means by Education Groups