1.1 Terminology Related to Stratigraphy

According to the International Chronostratigraphic Table developed by the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), the 4.6 billion years of our planet’s history are divided into eons, eras, periods, epochs and stages, with many dozens of names, mostly derived from Greek words or geographical locations. Importantly, the timing of the beginning and end of all stratigraphic units must be precisely defined and associated with specific geological events. However, these boundaries do not necessarily coincide with major climatic changes or changes in the regime of climate variability.

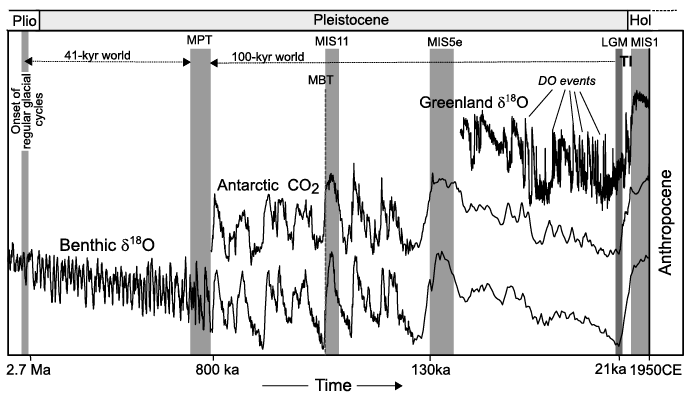

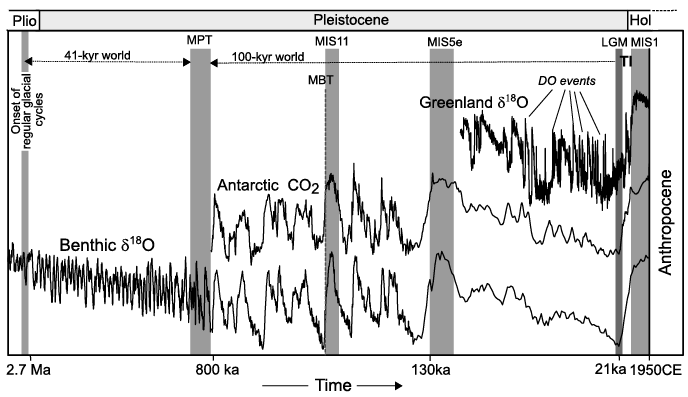

This book is primarily concerned with the Quaternary, which, according to the ISC, began at 2.58 Ma after the end of the Neogene period; 2.58 Ma is also the boundary between the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs, and this is why it is also known as the Pliocene–Pleistocene Transition (PPT). However, from a climatological point of view, “Quaternary” is primarily associated with the period of time with regular glacial cycles, and the onset of such glacial cycles occurred around 2.7 Ma, that is, significantly earlier than the official PPT. The Quaternary period is divided into two epochs: Pleistocene and Holocene. The latter began at 11.7 ka and thus represents only 0.3% of the Quaternary, while the remaining 99.7% is covered by the Pleistocene. Such a division is difficult to justify from a purely climatological point of view, since the Holocene was, at least until recently, one of more than 50 previous Quaternary interglacial periods. Since the official chronostratigraphic terminology alone is insufficient for describing climate variability during the Quaternary, this book also uses several other terminological systems (see Figure 1.1). One of these is the so-called Marine Isotope Stages (MISs). This name is related to the fact that the MISs are derived from the marine oxygen isotope records. Odd numbers of MISs correspond to interglacial and even numbers to glacial conditions. The exception is the last glacial cycle, which is divided into five MISs, with the additional division of MIS 5 into five sub-substages, of which only MIS 5e is the true interglacial. The Quaternary is divided into more than 100 MISs, while before 2.58 Ma, a different naming system is used to identify climate variability. The names of stages from the International Chronostratigraphic Chart are not used in this book.

Figure 1.1 Selected Quaternary chronological terminology used in this book illustrated by the three most influential paleoclimate records: benthic ![]() , Antarctic and Greenland ice cores. Abbreviations: Plio – Pliocene, the epoch preceding the Quaternary period; Holo – Holocene, officially the current geological epoch, also the name of the current interglacial, equivalent to MIS 1; TI – the last glacial termination or Termination I; LGM – Last Glacial Maximum, time slab corresponding to the time interval 22–19 ka; MIS 5e – previous interglacial, also known as the Eemian interglacial; MIS 11 – the longest interglacial of the late Quaternary and the first interglacial after the Mid-Brunhes Transition; MPT - Mid-Pleistocene Transition, the transition from the 41-kyr to the 100-kyr world.

, Antarctic and Greenland ice cores. Abbreviations: Plio – Pliocene, the epoch preceding the Quaternary period; Holo – Holocene, officially the current geological epoch, also the name of the current interglacial, equivalent to MIS 1; TI – the last glacial termination or Termination I; LGM – Last Glacial Maximum, time slab corresponding to the time interval 22–19 ka; MIS 5e – previous interglacial, also known as the Eemian interglacial; MIS 11 – the longest interglacial of the late Quaternary and the first interglacial after the Mid-Brunhes Transition; MPT - Mid-Pleistocene Transition, the transition from the 41-kyr to the 100-kyr world.

There are a number of other useful terms used in paleoclimatology to designate different, more or less well-defined time intervals, such as the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, the interval between 22 and 19 ka), glacial terminations (numbered backwards in time with the most recent Termination I starting at ca. 18 ka and ending at ca. 7 ka) and the Eemian Interglacial (the name of the penultimate interglacial or MIS 5e, between about 130 and 120 ka). Some time intervals, usually associated with significant deviations in paleoclimate characteristics, are called “events” (such as numerous Dansgaard–Oeschger and Heinrich events), and some are called “transitions” (e.g., the mid-Pleistocene Transition – MPT). In this book, all these terms and many others are used for convenience, but usually without any attempt to give strict definitions or their precise timing.

According to the ICS, we are still living in the Holocene epoch, the most recent part of the Quaternary. However, many scientists argue that current human activity has caused significant changes to the environmental conditions in general and the climate in particular, and that there is a need to introduce a new epoch – the Anthropocene. At the time of writing, this idea has been rejected by the ICS Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy, which, of course, cannot prevent the use of the term “Anthropocene” in the scientific literature. Climate change during the Anthropocene is discussed in Chapter 8 of this book.

When time is expressed numerically, it is usually defined as the time before present (BP), but the “present” moves in time. This is not a problem when discussing rather ancient times (millions or thousands of years ago), but for more recent times, it is necessary to define the meaning of “present” more precisely. One possible solution is to use B2K (i.e., before 2000 CE [Common Era]) instead of the present. For the Holocene, especially when applied to the history of human civilization, it is common to use the terms Common Era and Before Common Era. For the future, which will be discussed in the Anthropocene chapter, the use of a Common Era would be appropriate for the current millennium, but for a longer (deep) future, to avoid possible confusion, the year after present (AP) will be used.

It is important to note that, for historical reasons, the opposite direction of the time axis to that commonly used in other branches of science (time increases to the right) is still used in many paleoclimate publications. This book uses exclusively the “physical” direction of the time axis. The standard abbreviations for time are kyr (1000 years), ka (1000 years BP) and Ma (million years BP), where BP is before present (in case the accuracy of the time definition is significantly less than 100 years) and B2K is before the year 2000 CE, for a more accurate time scale. Note that in paleoclimatology, the term “age model” is often used as a synonym for time.

1.2 Earth System

1.2.1 Earth as the Planet

The Earth is the third planet in the Solar System and the only known habitable planet in the Universe. The Earth’s climate is largely controlled by astronomical parameters such as the luminosity (total amount of energy emitted into space in a unit of time) of the nearest star (the Sun) around which the Earth orbits, the distance to that star, the radius and mass of the Earth, the period of its rotation on its axis and the angle between the plane of rotation around the Sun and the Earth’s axis of rotation. Some of these characteristics change over time and cause climate change. The solar luminosity gradually increasing due to the typical life cycle of Sun-like stars (gradual internal heating and expansion). It is thought that 4000 Ma ago, the solar luminosity was about 25% lower than today. However, during the Quaternary, the long-term trend in solar luminosity has been negligible. Solar luminosity also varies on much shorter time scales (periods of 11, 80 and 200 years), but these variations are very small (on the order of 0.1% of the average solar “constant”) and likely of little importance for understanding past climate change.

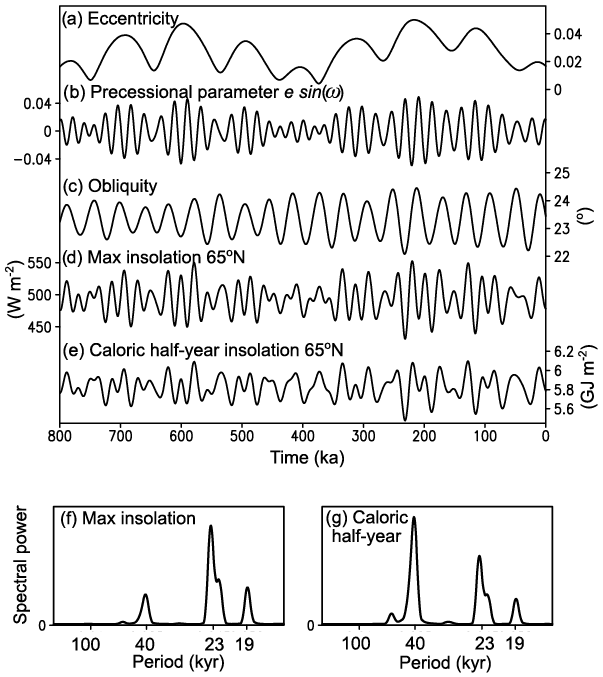

The Earth orbits the Sun along an ellipse that is currently very close to a circle. The parameters of the Earth’s orbit (eccentricity and the so-called precession parameter) and the angle between the direction of the Earth’s axis of rotation and the plane of its rotation around the Sun (obliquity) vary in time with several periods ranging between 20,000 and 2 million years. These variations in the Earth’s orbital parameters play a crucial role in Quaternary climate variability (see Box 1.1).

By far the largest source of energy affecting climate and life is the Sun. This is more than three orders of magnitude larger than the geothermal heat flux, but the latter still plays an important role in ice sheet dynamics and affects deep ocean temperature. The dissipation of tidal energy associated with the gravitational interaction with the Moon and Sun is an order of magnitude smaller, but is important for vertical mixing in the deep ocean and thus for global ocean circulation and energy transport. A large amount of energy is currently produced by human activity, mainly through the burning of fossil fuels. Note that this does not include the greenhouse effect of the greenhouse gases produced, which is several orders of magnitude greater than the direct heat produced by combustion. So far, this heat emission has only a local direct effect on climate.

The rate at which the Earth rotates on its axis determines the length of day and night and strongly influences atmospheric and oceanic dynamics through the so-called Coriolis force. The angular rate of the Earth’s rotation has been decreasing since the formation of the Earth due to tidal dissipation, but over the last few million years, it can be considered constant.

The presence of an ocean and the composition of the atmosphere are two closely related factors that strongly influence climate and are critical for the existence of life, which in turn influences the composition of the atmosphere. They are the result of a very long-term co-evolution of different components of the Earth system.

1.2.2 Atmosphere

The term “climate” has historically referred to the average state of the atmosphere, although it is now used in a broader sense to include other components of the Earth system, such as the hydrosphere and cryosphere. Nevertheless, in the discussions of climate and climate change, atmospheric properties such as near-surface air temperature and precipitation are given primary attention.

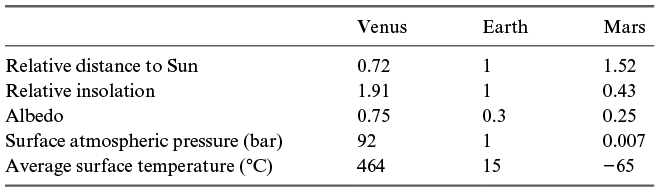

The Earth’s atmospheric composition and mass are radically different from those of two neighboring Earth-type planets – Venus and Mars (see Table 1.1). This is explained by the presence of water and life on Earth. While the atmospheres of Venus and Mars consist mainly of CO2, the Earth’s atmosphere consists mainly of nitrogen and oxygen. The current CO2 concentration in the Earth’s atmosphere is about 0.04%, while the preindustrial concentration was 0.028%.

| Venus | Earth | Mars | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative distance to Sun | 0.72 | 1 | 1.52 |

| Relative insolation | 1.91 | 1 | 0.43 |

| Albedo | 0.75 | 0.3 | 0.25 |

| Surface atmospheric pressure (bar) | 92 | 1 | 0.007 |

| Average surface temperature (°C) | 464 | 15 | −65 |

Note: Venus and Martian atmospheres consist mostly of CO2, while the CO2 concentration in the Earth’s atmosphere is currently 0.04%. The difference in insolation between Earth and Mars can only explain about 40°C difference, while in reality, it is almost twice as large. The reason is that the greenhouse effect makes the Earth about 33°C warmer than it would be without the greenhouse effect, while the Martian atmosphere is too thin to cause a significant greenhouse effect. Venus, with its high albedo, should be even colder than the Earth without the greenhouse effect. In fact, it is 450°C warmer than Earth because of a much stronger greenhouse effect.

The composition of the atmosphere is one of the key factors determining the Earth’s climate and has changed drastically over the past 4 billion years due to geochemical and biological processes. Most constituents of the atmosphere are well mixed – that is, have nearly constant concentrations in space and time (at least on an annual time scale), except in the upper atmosphere. Two gases dominate the Earth’s atmosphere – nitrogen and oxygen (together 99%) – but their concentrations remain nearly constant on time scales of millions of years and so do not play an active role in Quaternary climate change. There are three other well-mixed gases that make up a much smaller fraction of atmospheric mass, but because they are greenhouse gases (i.e., they actively absorb infrared radiation), they play a significant role in past climate changes, particularly during the Quaternary: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O). Concentrations of these gases varied almost synchronously with Quaternary glacial cycles and played a key role in past climate change. These three gases, especially CO2, are also the main drivers of current anthropogenic global warming.

There are a few important gases that have a relatively short lifetime in the atmosphere, so their concentrations vary considerably over time and space. These are water vapor and ozone. Since most of the Earth’s surface is covered by the ocean, the atmosphere contains a significant amount of water vapor (up to 1% near the ocean surface in the tropics), but the concentration of water vapor decreases rapidly with altitude and toward the poles. Water vapor is the main greenhouse gas in the Earth’s atmosphere and explains most of the natural 33°C greenhouse effect. It also plays a major role in horizontal energy transport in the atmosphere and forms clouds, which play an important role in the Earth’s radiative budget and hydrological cycle.

The lifetime of ozone is controlled by chemical reactions. Stratospheric ozone is formed by photochemical reactions, and its concentration decreases from the equator to the poles. Ozone is important for the Earth’s radiation budget because it absorbs most of the UV radiation. For the same reason, it is important for human health, which is why the depletion of ozone over Antarctica observed in recent decades (the “ozone hole”) has caused serious concern in the past.

In addition to gases, the Earth’s atmosphere always contains a certain amount of impurities such as dust and salt particles, black carbon and sulfur aerosol. Although in relatively small concentrations, different types of aerosol play important roles in climate and climate change through their direct influence on the Earth’s radiative balance and indirect influence through cloud formation. Aerosol deposition over snow cover can also affect its albedo, and in the ocean, dust deposition also affects the ocean carbon cycle.

The most important climatological property of the atmosphere is its temperature. The three-dimensional temperature field in the atmosphere is influenced by, and in turn controls, atmospheric radiative processes, atmospheric circulation and the hydrological cycle. In particular, atmospheric temperature is affected by absorption and emission of radiation (both shortwave and infrared), phase transitions (condensation), vertical mixing, advection by large-scale and mesoscale motions, and other processes. Therefore, accurate modeling of the atmospheric temperature distribution, and consequently of other atmospheric properties, is a serious challenge. In addition, atmospheric temperature and the associated energy exchange strongly influence the ocean, cryosphere and biosphere.

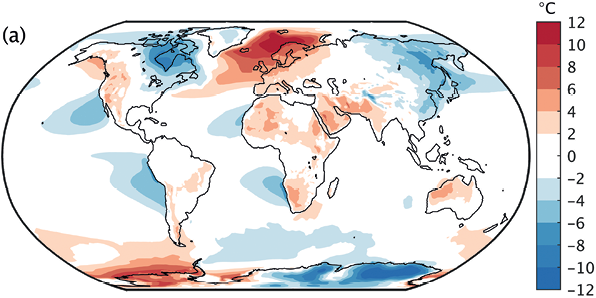

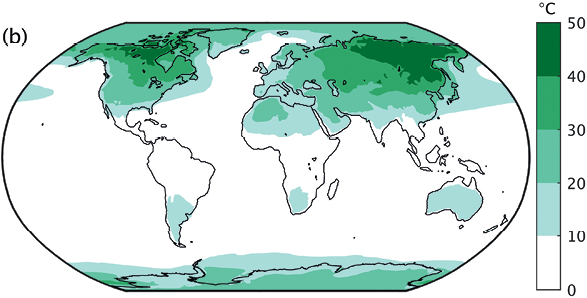

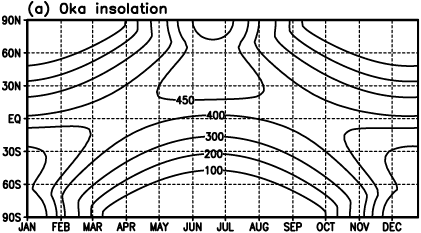

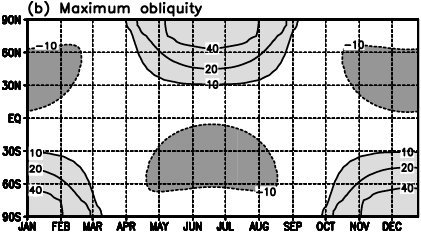

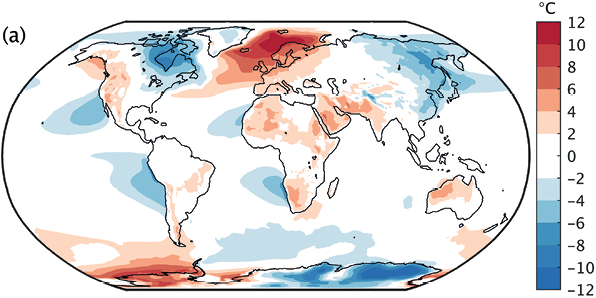

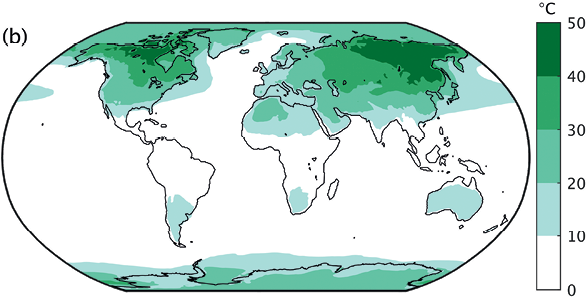

The temperature in the troposphere (the lowest 10–15 km), averaged over the climatological time scale, decreases approximately linearly with altitude, and the average lapse rate (vertical temperature gradient) in the troposphere is close to 6°C/km. The horizontal temperature distribution is mainly controlled by the insolation (which depends on latitude and season), the planetary albedo and the horizontal energy transport in both the atmosphere and the ocean. The seasonal distribution of insolation is controlled by the Earth’s astronomical parameters, which vary with orbital periods of 104–105 years. These variations are the direct cause of the Quaternary glacial cycles and associated climate variability. The areas where the ocean releases large amounts of energy to the atmosphere are also characterized by positive temperature anomalies relative to the zonally averaged annual mean temperatures (see Figure 1.2a). This explains numerous and significant regional temperature changes observed on millennial time scales during most of the Quaternary. In addition, seasonal temperature variations strongly depend on the heat capacity of the underlying surface and are much larger in the continental interior than in the ocean (see Figure 1.2b).

(a) Deviation of the annual mean surface air temperature, corrected for the elevation effect, from the zonal mean temperatures

Figure 1.2(a)Long description

Global deviations in annual mean surface air temperature after correcting for elevation effects. The scale ranges from negative 12 degrees Celsius to positive 12 degrees Celsius. Strong warm anomalies appear near the Arctic, Northern Europe, Western Antarctica, and some parts of North America. Cooler anomalies appear around Eastern Antarctica, the Oceans, and Eastern Russia.

(b) The magnitude of the seasonal variations of the surface air temperature computed from ERA-Interim reanalysis data.

Figure 1.2(b)Long description

Global magnitude of the seasonal variations of the surface air temperature. The scale ranges from 0 degrees Celsius to 50 degrees Celsius. The highest seasonal variation ranges appear near North America, Europe, and Northern Asia. Moderate seasonal variation ranges appear near South America and Southern Africa. Lesser seasonal variation ranges appear near Australia and the oceans.

The distribution of water vapor (expressed in terms of specific humidity) in the atmosphere is closely related to air temperature, since the specific humidity of saturated water vapor is an exponential function of air temperature. Therefore, to a first approximation, the vertical profile of specific humidity can be approximated by the exponent with a vertical height scale of about 2 km. The distribution of relative humidity is mainly controlled by the atmospheric circulation and the type of underlying surface (ocean or land). As the most important greenhouse gas, water vapor is responsible for the strongest positive climate feedback, amplifying climate changes caused by other greenhouse gases and other climate forcings. Water vapor transport is an essential element of the global hydrological cycle, strongly influencing ocean circulation, the cryosphere and the biosphere. Condensation of water vapor leads to cloud formation, which plays an equally important role in controlling climate and climate change. The set of cloud-related climate feedbacks represents the main uncertainty in modeling the climate response to changes in atmospheric CO2 concentration. The amount of water which condensates in the atmosphere and then precipitates, together with air temperature, determines the spatial distribution of vegetation.

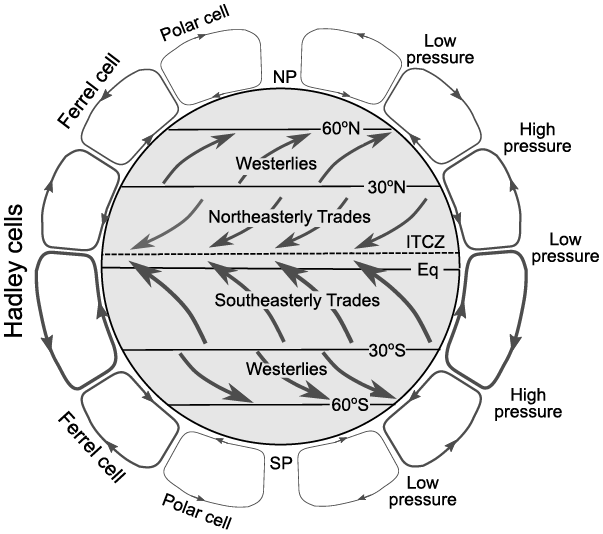

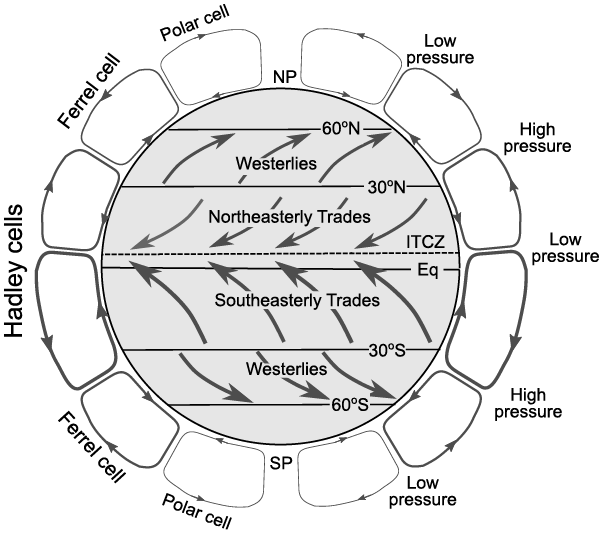

Atmospheric circulation (i.e., the movement of air, usually referred to as wind) is a complex three-dimensional phenomenon with a wide range of temporal and spatial scales (see Figure 1.3). It plays a fundamental role in climate and climate change. The global circulation of the atmosphere includes such large-scale (>103 km) phenomena as the trade winds, westerlies, monsoons and the meridional cells of the atmospheric circulation. The latter are represented by three pairs of cells: Hadley, Ferrel and Polar cells. This complex circulation results from the interplay between temperature gradients from the equator to the poles and the rotation of the Earth around its axis. This qualitative circulation pattern is robust to a wide range of global climates, but seasonal variations in the intensity and meridional extent of individual cells are influenced by climate and, in turn, affect climate. For example, asymmetric temperature changes in different hemispheres lead to a meridional shift in the position of two Hadley cells, affecting the location of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). At the same time, global warming or cooling causes the Hadley cells to expand or contract. This zonally averaged meridional circulation is a major contributor to the sea level pressure patterns that drive the major zonal winds known as the trades and westerlies. Again, this pattern is fairly stable across different climates, but the strength and position of both wind systems are affected by climate change. Another element of atmospheric circulation that strongly influences regional climate and is sensitive to climate change is the monsoon circulation. There is both empirical and modeling evidence that the strength of the south-east Asian monsoon, for example, has varied greatly both during glacial cycles and during millennial climate changes.

Figure 1.3 Large-scale atmospheric circulation for northern summer conditions. The Intertropical Convergence Zone is shifted north of the equator, the southern Hadley cell is stronger and wider than the northern one, and the southern zonal winds are stronger than the northern ones.

Figure 1.3Long description

The diagram shows by arrows the direction of the westerlies (winds blowing eastwards) and trades (winds blowing westwards) in both hemispheres for northern summer conditions when the Intertropical Convergence Zone is located north of the equator. The figure also shows the main cells of the atmospheric meridional circulation and the direction of air movement in these cells. The figure also shows the location of low-pressure areas (equatorial belt and high latitudes of both hemispheres) and high-pressure areas (subtropics).

1.2.3 Hydrosphere

The Earth is unique in having a large amount of water in liquid form on its surface, known as the hydrosphere. Most of the water is found in the oceans, which play a fundamental role in the climate system as an essentially unlimited source of water for the energy and water cycles. According to geological data, the ocean has been present for most of the Earth’s 4 billion years of history. The presence of the ocean is thought to be crucial to both the existence of life and plate tectonics.

The world’s oceans contain about 97% of the Earth’s water and cover 71% of the Earth’s surface. During the late Quaternary glacial cycles, the volume of the ocean varied by 3% and its area by about 6%. Unlike the atmosphere, which is global, the ocean consists of three major ocean basins separated by continents and connected mainly by the circumpolar Southern Ocean. Plate tectonics changes the geographical patterns of the oceans on geological time scales, but during the Quaternary the configuration of the ocean (apart from shelf areas affected by sea level changes) was very similar to that of today.

The modern ocean has an average depth of 4000 km, and its heat capacity per unit area exceeds that of the atmosphere by three orders of magnitude. The ocean is therefore an important heat reservoir on time scales from seasonal to centennial. Even considering only the upper layer of the ocean, the heat capacity of the ocean is one to two orders of magnitude greater than that of the atmosphere. As a result, the ocean absorbs a large amount of energy in summer and releases it in winter, significantly reducing the amplitude of seasonal temperature variations. The difference between maximum and minimum temperatures over open water does not usually exceed 10°C. The heat released by the ocean is transported by the atmosphere to the surrounding land, where the air cools rapidly in winter, so that the moderating effect of the ocean diminishes toward the continental interior (see Figure 1.2b).

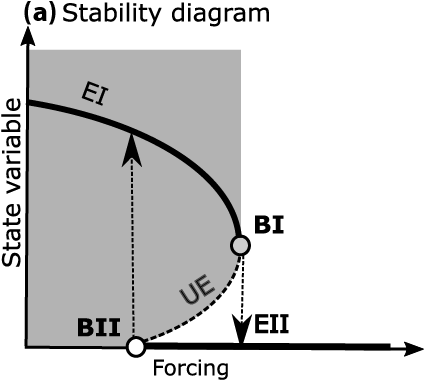

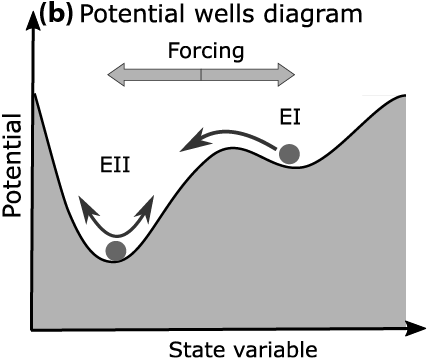

Unlike the atmosphere, most of the ocean is stably stratified, mainly due to a decrease in temperature with depth. As a result, vertical mixing is efficient only in the upper mixed layer, typically a few tens to a few hundred meters deep, below which vertical mixing is very weak. Only in a few rather small areas in the high latitudes of the Atlantic and near Antarctica could surface cooling during winter destabilize a significant part of the water column. Although these areas are small compared to the ocean as a whole, they play a very important role in ocean circulation and therefore in climate. Because the deep ocean is filled with water masses formed at high latitudes, the global volume-averaged temperature of the ocean is only 4°C, while the average sea surface temperature is 18°C.

Ocean water contains about 3.5% salt per unit mass. Although the total salt content of the ocean changes only on geological time scales, local salinity, defined as the amount of salt per kilogram of seawater, changes significantly, especially in the upper ocean. The presence of salt in the water plays an important role in the ocean. At low temperatures, the effect of salinity on seawater density is comparable to that of temperature. Because salinity affects vertical mixing and ocean circulation, the large-scale ocean circulation is still often called “thermohaline circulation,” that is, driven by temperature and salinity (the Latin word “haline” means salt). The presence of salt in seawater also eliminates an anomalous property of freshwater related to maximum density. Freshwater reaches its maximum density at about 4°C. Further cooling makes the water lighter. This makes it easier for ice to form in freshwater. In the sea, the maximum density is not reached before the freezing point at −1.8°C for average ocean salinity.

The oceans transport energy from the tropics to the high latitudes that is comparable to the amount of energy transported by the atmosphere (see Section 1.3). The energy is transported by several types of processes: meridional overturning circulation, Ekman transport, ocean gyre circulation and transient synoptic eddies. The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), has attracted particular attention, as both empirical data and modeling results suggest that this type of circulation experienced significant and sometimes very abrupt variations during the Quaternary, causing large climate changes at both regional and global scales. This variability of the AMOC is attributed to its intrinsic instability under cold glacial climatic conditions (see Chapter 6). However, although it may seem counterintuitive, model simulations suggest that a significant weakening of the AMOC may also occur in the relatively near future in response to anthropogenic climate warming (see Chapter 8). Currently, the AMOC transports more than 1 PW of energy northwards across the equator. This energy is released over relatively small areas of the ocean, and there are regions, such as the North Atlantic, where the annual mean energy flux from the ocean to the atmosphere reaches 100 W/m2, a value comparable to the energy received from the Sun. Therefore, a complete shutdown of the AMOC leads to a decrease in the annual mean surface temperature of about 10°C in the areas where heat is currently being released into the atmosphere. The pattern of climate response to AMOC shutdown is similar to that of present-day azonal temperature anomalies (Figure 1.2a).

Other elements of the hydrosphere, such as lakes, rivers and groundwater, also play an important role in the hydrological cycle, although they contain much less water. In particular, rivers redistribute water over long distances and provide significant freshwater input to the ocean, affecting ocean circulation. During glacial periods, some rivers routing changed significantly compared to modern times due to blockage by ice sheets and changes in topography. This, in turn, can lead to a significant change in the area of the ocean that receives meltwater from the ice sheet. Lakes are an important source of local precipitation and can act as important positive feedback, explaining, for example, the “green Sahara” phenomenon during the mid-Holocene and earlier interglacials. During glacial periods, proglacial lakes formed during ice sheet retreat can, in turn, significantly affect ice sheet mass loss and hence the rate of retreat (see Chapter 5).

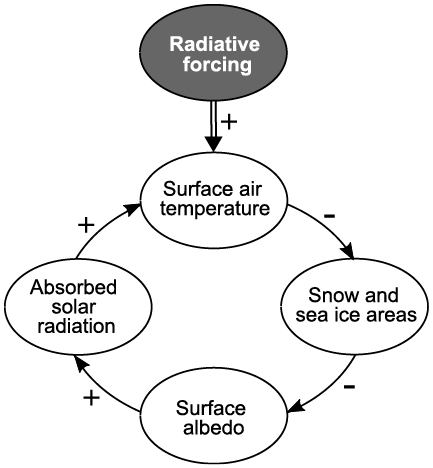

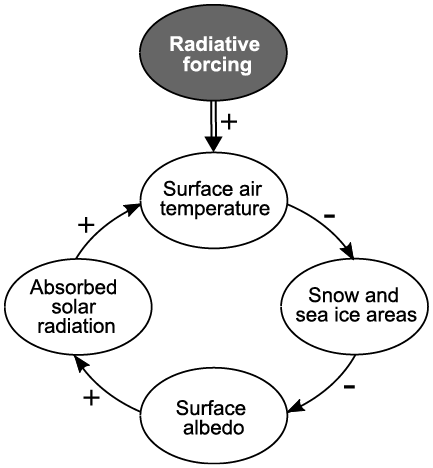

1.2.4 Cryosphere

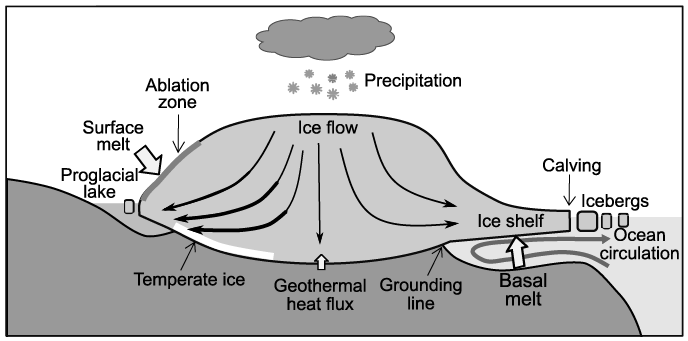

The cryosphere is defined as all water in solid form, that is, snow, sea ice, permafrost (i.e., frozen ground water), glaciers and ice sheets. Snow cover (both land, sea ice and ice sheets) plays an important role in surface and planetary albedo and contributes significantly to the albedo-climate feedback. Sea ice also contributes to albedo, but it also affects ocean circulation and the exchange of energy, water and gases between the ocean and the atmosphere. Permafrost stores a significant amount of carbon, which can be released into the atmosphere when the permafrost thaws. However, ice sheets play by far the most important role in Quaternary climate dynamics. Ice sheets are the slowest component of the climate system. A typical response time of ice sheets to orbital or radiative forcing is on the order of thousands to tens of thousands of years, that is, comparable to the time scales of orbital forcing. Ice sheets are therefore never in equilibrium and their response to external and internal forcings is fundamentally transient.

Two existing at present ice sheets – Antarctic and Greenland – contain the amount of ice that, if melted completely, would raise global sea level by about 65 meters. During the Quaternary, two other major ice sheets were periodically formed over North America and Eurasia, and the global volume of ice sheets during the Last Glacial Maximum was about three times greater than today, with ice sheets covering up to 10% of the Earth’s surface. Understanding the processes by which ice sheets translate regional and seasonal changes in insolation caused by variations in Earth’s orbital parameters to global scale long-term climate change is one of the major challenges of Quaternary climate dynamics and is discussed in Chapter 6.

The temporal evolution of ice sheets is primarily controlled by their mass balance and internal dynamics. For land-based ice sheets, the mass balance is essentially a surface mass balance is determined by accumulation (mainly snowfall) and surface melt, most of which occurs at low elevations. Where ice sheets extend into the ocean, calving (iceberg formation) and melting at the base of ice shelves or glaciers in the ocean can also play an important role in the mass balance of the ice sheet. The accumulation of ice in the center of ice sheets and the melting or calving at the margins creates a gradient in ice sheet surface elevation, which drives the dynamics of the ice sheets. To a first approximation, ice can be considered as a very viscous but non-Newtonian fluid, since ice viscosity depends strongly on temperature and internal stress. Typical velocities in the interior of the ice sheet are on the order of several meters to 100 meters per year. At the margins, and especially in ice streams, the ice can move much faster, up to several kilometers per year. The rate of movement of the ice sheet depends on the thickness and slope of the ice sheet, and even more so on the state of the base of ice sheet. There are two main types of basal conditions – one is when the temperature at the base of the ice is below the pressure melting point (which is 0°C at zero pressure and decreases by about 1°C for every kilometer of ice thickness). If the ice is frozen to the bed, the horizontal velocity of the ice at the base is close to zero. However, if the base of the ice sheet is at the pressure melting point and there is a (usually very thin) layer of water separating the ice from the bedrock, the ice can slide and move much faster.

The Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets have existed for millions of years, but new ice sheets can form relatively quickly in the high latitudes of the NH under favorable climatic conditions, such as cold summers during periods of low summer insolation. The formation of a new ice sheet requires an area of perennial snow cover, which can continuously accumulate snow and form an ice cap. Initial ice caps can then expand laterally and grow into a large ice sheet on a time scale of thousands of years. During this growth phase, several positive feedbacks play an important role. First, the increase in the area of the ice sheet, at least initially, proportionally increases the total accumulation of snow. Second, the surface albedo of the ice sheet is significantly higher than that of ice-free land under the same climate conditions. This increases the planetary albedo above the ice sheet, reducing the absorbed solar radiation and leading to strong regional cooling. This in turn reduces surface melting and makes the overall surface mass balance of an ice sheet more positive. The third is the elevation feedback. This is related to the fact that the atmospheric temperature typically decreases by 4–6°C per kilometer of altitude. The downward longwave radiation flux also decreases with altitude. This leads to a reduction in both sensible heat flux and absorbed longwave radiation. As a result, the higher the ice sheet, the less it melts.

Since the Quaternary ice sheets did not grow indefinitely, there must also be some negative feedbacks. One is related to the fact that as the ice sheets expand southwards (in the NH), the ambient atmospheric temperature rises and so does the surface melt. Another negative feedback, known as the desert-elevation feedback, is related to a reduction in precipitation over high and extensive ice sheets. While total precipitation continues to increase with the size of the ice sheet, most of the precipitation occurs over the ice sheet margins, with very little snowfall occurring in the central part of the ice sheet.

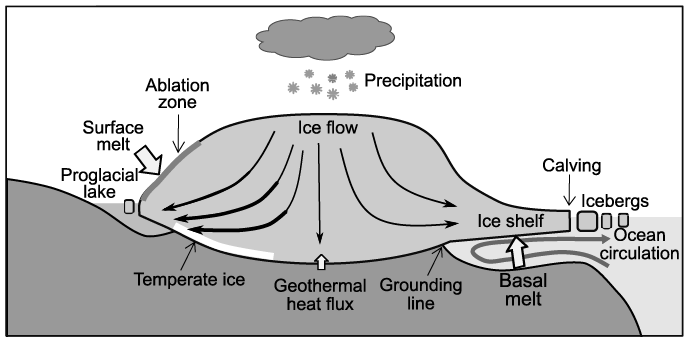

The above-mentioned processes and feedbacks are only a part of the large number of feedbacks and processes associated with ice sheet-climate interactions (see Figure 1.4). In particular, ice sheets also modify atmospheric circulation and precipitation patterns. According to model simulations, the growth of the Laurentide ice sheet leads to a strengthening of the westerlies over the Atlantic, which also affects the circulation of the Atlantic Ocean. At the same time, stationary topographic waves associated with high ice sheets affect the temperature in the areas away from the ice sheet. Model simulations show that the changes in atmospheric circulation caused by a large Laurentide ice sheet lead to pronounced warming west of the ice sheet.

Figure 1.4 Conceptual scheme of the interaction between climate and the ice sheet under glacial climate conditions.

Figure 1.4Long description

The diagram shows a vertical cross-section of a typical land-based ice sheet and associated ice shelf. The arrows within the ice sheet indicate the direction and speed of ice movement. It also shows the location of the ablation zone (the surface of the ice sheet at low altitude) and the location of the temperate ice (ice at the pressure melting point) at the base of the ice sheet. They also show major processes and fluxes, such as geothermal heat flux at the base of the ice sheet, calving of icebergs into the ocean and proglacial lakes, and basal ice melting in the ocean.

Another important ice-sheet-climate interaction is related to the melting of the ice sheet and the calving of icebergs, which produce large amounts of freshwater. The average net freshwater flux from the ice sheets to the oceans (mainly the North Atlantic) during past glacial cycle was 0.1 Sv, but it can be significantly larger during certain intervals, such as Heinrich events. A large meltwater flux during glacial termination may be sufficient to significantly weaken the AMOC, reducing warming, over the North Atlantic and western Europe, which reduces surface melting of the ice sheets, and thus provides a significant negative feedback. Beyond these regional processes, changes in the ice sheets cause global sea level rise and fall. This affects climate, dust and carbon cycles around the globe.

1.2.5 Biosphere

The biosphere is the zone of air, water and land where life exists. While it includes most of the troposphere and the entire ocean, on land it is concentrated in a relatively thin layer of soil and just above the land surface. The total mass of the biosphere is rather small compared to other elements of the Earth system, but it plays an important role in past climate variability by controlling atmospheric composition, weathering rate, surface albedo and roughness, and the global hydrological cycle. The most important consequence of the existence of life on Earth is the high concentration of oxygen and low concentration of CO2 in the Earth’s atmosphere. Until recently, the biosphere was also the main source of methane.

The natural terrestrial biosphere (vegetation cover) is largely controlled by climate characteristics, such as summer and winter temperatures and annual precipitation. This fact has already been used in the Köppen climate classification. However, a one-to-one correspondence between climate and vegetation distribution can only be expected under constant climatic conditions, and in the case of climate change, vegetation dynamics must be taken into account. The time scales of the equilibration between climate and vegetation cover are not well known, but it is clear that the time scales can be very long (hundreds of years to millennia). In addition, more than 50% of the land surface is currently influenced by humans in one way or another.

The terrestrial biosphere, primarily vegetation, is not only controlled by the climate but also influences it in a number of ways. In particular, the presence of vegetation affects the albedo of the land surface. Land covered by dense vegetation has a lower albedo than bare soil, and even when vegetation is sparse, the presence of organic carbon in the soil makes it much darker than that of a sandy desert such as the Sahara. However, the difference in albedo between snow-covered forest and non-forest (grassland or bare soil) is particularly significant. While the surface albedo of the snow layer over a flat surface can be as high as 0.8, a forest, even when covered by snow, remains relatively dark with a typical albedo of 0.2–0.3. Summer warming in the boreal latitudes causes the forest to expand northwards, lowering the albedo and causing additional warming, creating a positive climate-vegetation feedback, also known as the taiga–tundra feedback (see Section 1.6). Vegetation also affects the global water cycle through evapotranspiration. Transpiration depends on climate, but also directly on CO2 concentration through stomatal resistance. In practice, this means that under the same climatic conditions, vegetation will evaporate less water at high CO2 levels, leading to additional regional warming. In addition to living biomass, much of the organic carbon on land is stored in peat and permafrost. These carbon pools have large capacity and long residence times and contribute to glacial-interglacial CO2 variations. During the late Holocene, deforestation caused significant CO2 emissions to the atmosphere and contributed to the observed anthropogenic climate change. The terrestrial biosphere is known to have been a significant net sink of anthropogenic CO2 (about 25% of anthropogenic emissions). In the future, however, thawing permafrost and soil degradation could become significant long-term sources of CO2. The presence of large amounts of organic carbon in soils affects weathering rates and thus atmospheric CO2 concentrations on the geological time scales. The terrestrial biosphere (mainly wetlands and termites) plays an important role in the methane cycle.

The marine biosphere is one of the smallest carbon pools. However, the carbon fluxes associated with the marine biosphere are not small, which is explained by the very fast turnover time of the marine biosphere. Most of the living marine biomass is concentrated in a thin (on the order of a hundred meters) upper layer of the ocean, where the intensity of sunlight is still sufficient for photosynthesis. Sinking organic matter and biologically produced calcites (shells) provide an important carbon flux to the deep ocean (biological pump). Changes in biological production as well as temperature-dependent remineralization rates, are the factors that influence the strength of the biological pump and thus the storage of carbon in the deep ocean, which is thought to be an important factor in explaining glacial-interglacial variations in CO2.

1.2.6 Solid Earth

Solid Earth processes beyond the top few meters of soil are not usually considered when studying short-term climate change. However, on longer time scales, the solid Earth is an important element in climate dynamics. First, plate tectonics, through changes in the position and elevation of the continents and the bathymetry of the oceans, affects the radiative balance of the climate system, atmospheric and oceanic circulation, and the global water and carbon cycles. In particular, the formation of high mountain ridges such as the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau has strongly influenced atmospheric circulation, in particular by enhancing monsoon circulation and summer precipitation.

Second, plate tectonics controls the release of CO2 through volcanoes and deep-sea hydrothermal vents. This has a direct effect on the atmospheric CO2 concentration because, on long time scales, atmospheric CO2 is controlled by the balance between volcanic outgassing and chemical weathering rates. The rate of uplift can also affect weathering, since the weathering rate of newly exposed rocks is much higher than that of old rocks and terrestrial sediments. It has been proposed that the last phase of the Cenozoic cooling was largely caused by increased weathering due to unusually rapid continental uplift. In addition to the permanent volcanic CO2 outgassing, the most powerful volcanic eruptions can affect the climate regionally and globally on time scales of several years, mainly through the formation of the sulfur aerosol layer in the stratosphere, which increases the reflection of sunlight.

On time scales of less than a million years, the position of the continents and surface orography can be considered constant, with the notable exception of areas periodically covered by large ice sheets. Ice loading lowers the lithosphere by about 1/3 of the thickness of the ice sheet, typically about 1 km. This lithospheric adjustment plays an important role in ice sheet dynamics, especially during glacial terminations. The typical relaxation time scale of lithospheric rebound depends on mantle viscosity and is in the range of 1000–10,000 years. Therefore, relatively rapid retreat of ice sheets during glacial terminations leads to the formation of periglacial lakes and inundation of continents by the ocean.

Another process related to the interaction between ice sheets and the solid Earth is glacial erosion. Advancing ice sheets transport terrestrial sediments toward the ice sheet margins. As a result of repeated glacial advances, the northern parts of North America and Scandinavia are largely devoid of terrestrial sediments, consisting primarily of exposed bedrock covered by only thin layers of soil. This process is considered crucial in explaining changes in the dominant periodicity of glacial cycles about 1 million years ago.

After the terrestrial sediments were removed, the waxing and waning of the ice sheets began to erode the bedrock, creating fjords, straits and inlets. The present Arctic Archipelago has been shaped by numerous advances of the North American Ice Sheet and was a relatively flat part of the North American continent prior to the Quaternary. Hudson Bay and the Hudson Strait are thought to have been formed by glacial erosion less than 1 million years ago. The presence of deep fjords and straits influences the dynamics of the ice sheet through the development of fast ice streams.

Finally, the geothermal heat flux, although rather small (in most cases less than 0.1 W/m2 on continental plates), plays an important role in ice sheet dynamics. Without this flux, ice sheets would be much less mobile, as they would have smaller areas of temperate ice at the base where rapid sliding is possible.

1.3 Global Energy, Water and Other Material Cycles

1.3.1 Earth Energy Budget

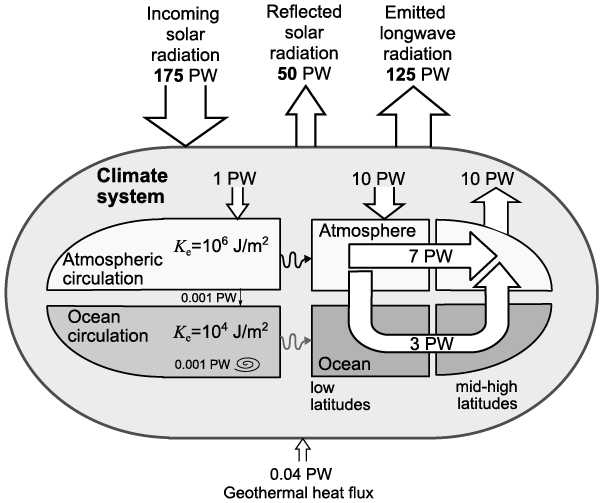

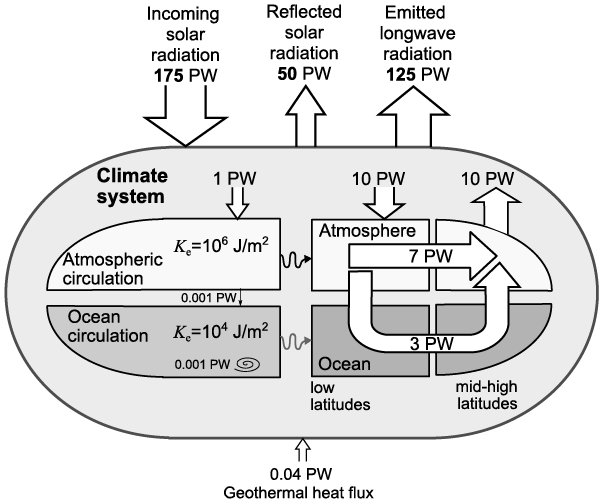

The amount of solar energy received by the Earth is determined by the so-called “solar constant,” which in reality is not exactly constant and is defined as the solar radiation per unit area perpendicular to the direction of the Sun’s rays at the average distance from the Sun to the Earth. This value is currently close to 1361 W/m2. This value has changed significantly over geological time scales, increasing by about 10% over the last billion years. The average amount of radiation absorbed per unit area of the Earth’s surface is about 240 W/m2, giving a total of about 125 PW (see Figure 1.5). This total depends on the planetary albedo, which in turn is mainly controlled by surface albedo and cloud cover. During glacial periods, the surface albedo changed significantly over areas covered by ice sheets, reducing the amount of radiation absorbed globally by up to 3 W/m2, or about 1%.

Figure 1.5 Global-scale energy balance and transport in the climate system. The climate system receives about 175 PW (1 PW = 1015W) of energy from the sun, of which 50 PW is reflected and 125 PW is emitted into space as longwave (infrared) radiation. Only about 1 PW of the absorbed energy is converted into kinetic energy in the atmosphere, and even less (about 0.001 PW) is transferred to ocean motion. A further 0.001 PW comes from the dissipation of tidal energy.

Figure 1.5Long description

The diagram shows the whole Earth system as an oval. Large arrows at the top of the oval indicate global incoming solar energy (175 petawatts), reflected solar energy (50 petawatts), and outgoing longwave radiation (125 petawatts). The total geothermal flux of 0.04 petawatts is shown at the bottom of the oval. Inside the oval, four segments illustrate the redistribution of energy within the atmosphere and ocean. The left segments show the transformation of the total energy flux into kinetic energy of atmospheric motion (1 petawatt) and kinetic energy of ocean circulation (0.001 petawatt). The right segments show that 7 petawatts of energy is transported in the atmosphere from low to high latitudes, while the ocean transports 3 petawatts.

On time scales much longer than a year, the radiative balance of the Earth system is close to zero, that is, the amounts of radiation absorbed by Earth and emitted back into space are very close to each other. The peculiarity of the Earth’s atmosphere is that it is sufficiently transparent to shortwave solar radiation, of which more than 50% reaches the Earth’s surface, but due to the presence of water vapor, CO2 and other greenhouse gases, the atmosphere is opaque to outgoing infrared radiation, and only 5% of the energy emitted from the Earth’s surface escapes directly into space through a narrow window in the absorption spectra of the atmosphere. The rest is absorbed in the atmosphere and re-emitted both upwards and downwards. Thus, a significant fraction of the absorbed solar energy is “recycled” many times within the atmosphere before it is able to leave it. This is the essence of the natural greenhouse effect, which for the preindustrial atmosphere was about 32°C in terms of global annual surface air temperature. This means that if the Earth’s atmosphere did not contain greenhouse gases, the surface temperature would be –18°C instead of the observed 14°C. During glacial times, reduction in CO2 concentration (and to a lesser extent methane and N2O) directly and through positive climate feedbacks reduced the natural greenhouse effect by about 3°C, which is comparable to the direct effect of ice sheets on surface temperature. At present, an anthropogenic increase in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases (in this case water vapor acting as a positive feedback) has led to an additional 1.5°C of global warming compared to preindustrial times.

Water plays a fundamental role in the Earth’s energy budget, not only as the main atmospheric greenhouse gas, but also through phase transitions and the associated latent heat transfer. The heat flux from the Earth’s surface to the atmosphere through evaporation is equal to almost half of the absorbed solar radiation. The horizontal transport of moisture in the atmosphere also accounts for a significant fraction of the meridional energy transport in the Earth system.

Only a small fraction of the solar energy absorbed by the Earth (less than 1%) is converted into kinetic energy in the atmosphere, and three orders of magnitude less is converted into kinetic energy of the ocean circulation. The Earth system is therefore an extremely inefficient heat engine. Nevertheless, the oceanic and atmospheric circulations redistribute significant amounts of energy between low and high latitudes: about 10 PW, or more than 10%, of the amount of solar energy absorbed at low latitudes (between 30°S and 30°N) is transferred by the atmosphere and ocean to the extratropics, making the Earth’s climate much more equable (see Figure 1.5). The atmosphere transfers more energy than the ocean, mainly through the meridional atmospheric circulation in the tropics and through the synoptic eddies (cyclones and anticyclones) at high latitudes. In the ocean, heat transport is dominated by the meridional overturning circulation (in the Atlantic) and by horizontal gyres and synoptic eddies elsewhere. While ocean eddies play a rather small role in meridional ocean heat transport, they contain most of the oceanic kinetic energy and play an important role in ocean dynamics.

1.3.2 Global Water Cycle

The global hydrological cycle plays an important role in the climate system and climate change for a number of reasons. First, evaporation, condensation and horizontal moisture transport in the atmosphere are important components of the Earth’s energy balance and energy transport. Second, water vapor is the most important greenhouse gas and provides a strong positive feedback for climate change caused by other factors. Third, clouds play a critical role in the energy balance of the climate system. Fourth, the balance between evaporation and precipitation affects the salinity of the ocean surface and hence the ocean circulation. Fifth, the hydrological cycle largely determines the evolution of ice sheets. Finally, precipitation determines spatial patterns of vegetation cover, especially in the subtropics.

In contrast to energy, atmospheric moisture in the tropics is transported toward the equator, and only outside the tropics is it transported toward the poles. This is related to the meridional atmospheric circulation – the Hadley and Ferrell cells. Latitudinal zones characterized by ascending air have high precipitation, and zones with descending air have low precipitation. As a result, the zonal distribution of precipitation is characterized by a strong maximum at the equator and smaller maxima in the midlatitudes, with local minima in the subtropics. Meridional moisture transport at high latitudes is dominated by synoptic eddies. As the water holding capacity of air is lower at low temperatures, precipitation has a tendency to decrease toward the poles.

Due to the strong dependence of water vapor on temperature, the hydrological cycle is significantly enhanced with global warming and weakened with cooling, but this does not mean that precipitation increases/decreases everywhere with higher/lower temperatures. This is due to the strong influence of atmospheric dynamics on precipitation. As the position and width of the Hadley cell depend on the climate state, this factor explains the complexity of the response of precipitation to climate change. At regional and local scales, the Earth’s topography strongly influences the distribution of precipitation. On geological time scales, mountain uplift leads to a large spatial redistribution of precipitation. On astronomical time scales, the retreat and growth of ice sheets cause pronounced changes in atmospheric dynamics and precipitation. Another component of atmospheric dynamics that strongly influences regional precipitation patterns is the monsoon circulation. Both paleoclimate records and model simulations show that the monsoon circulation is highly sensitive to changes in Earth’s orbital parameters and reorganizations of the AMOC.

More than half of the water that precipitates over land then evaporates back into the atmosphere, and the rest is returned to the oceans through river and groundwater flows. Because the flow of water to the ocean is controlled by surface elevation, changes in river routing are very slow. However, the growth of large continental ice sheets during glacial periods can block some rivers, form periglacial lakes and significantly alter surface water fluxes. In addition, ice sheets themselves are important sources of freshwater for the ocean, both in the form of surface runoff and the solid ice discharge (icebergs calving), which can melt far from where they are formed.

1.3.3 Global Carbon Cycle

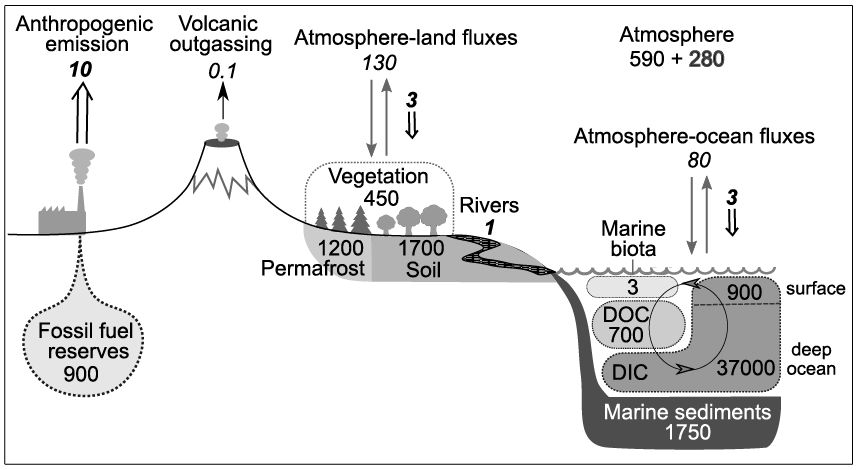

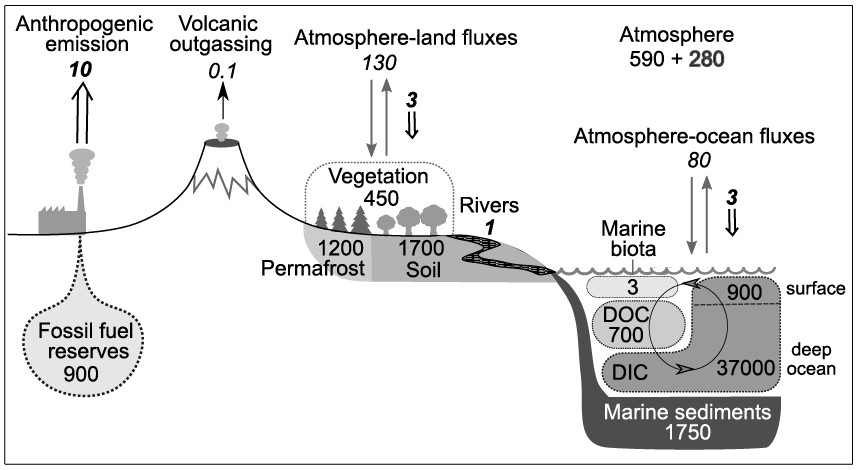

Since CO2 is the main well-mixed greenhouse gas responsible for a significant fraction of climate variability throughout Earth’s history, understanding the carbon cycle is very important for climate dynamics. Although the atmosphere is a very small reservoir of carbon compared to the ocean and the Earth’s crust, the amount of carbon in the atmosphere to a large degree determines climate. The atmosphere interacts with other carbon reservoirs in a rather complicated way (see Figure 1.6), and this interaction gives rise to several positive and negative climate-carbon cycle feedbacks.

Figure 1.6 Global carbon cycle. Regular numbers indicate the size of carbon pools in GtC (109 tonnes in carbon equivalent), italic numbers correspond to annual carbon fluxes in GtC/yr. Bold italic numbers correspond to anthropogenic CO2 emissions and fluxes associated with anthropogenic activities (both fossil fuel combustion and land use). Bold regular number indicates change in the atmospheric inventory due to anthropogenic emissions. DOC stands for the dissolved organic carbon and DIC for the dissolved inorganic carbon.

Figure 1.6Long description

The diagram shows the fluxes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere - anthropogenic emissions (10 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide per year in carbon equivalent and volcanic outgassing of 0.1 gigatonnes per year. The diagram also shows the total carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere (590 gigatonnes in pre-industrial times and an additional 280 gigatonnes from anthropogenic emissions) and the terrestrial carbon pool (450 gigatonnes in the living biosphere, 1700 gigatonnes in unfrozen soil, and 1200 gigatonnes in permafrost). The graph also shows the carbon content of the ocean in the form of dissolved inorganic carbon (38000 gigatonnes), dissolved organic carbon (700 gigatonnes), and marine biota (3 gigatonnes). In addition, marine sediments contain about 1750 gigatonnes of carbon.

On geological time scales (>105 years), the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is primarily controlled by the balance between volcanic outgassing and carbon removal from the climate system by silicate weathering and organic carbon burial. Volcanic outgassing is closely linked to plate tectonics and spreading rates. Thus, on geological time scales, plate tectonics is the primary driver of climate change. At the same time, the rate of weathering is strongly dependent on precipitation and therefore climate. As volcanic outgassing increases, so does atmospheric CO2 concentration. This leads to an increase in global temperature and an intensification of the hydrological cycle. In turn, high precipitation increases the rate of silicate weathering, which more efficiently removes CO2 from the atmosphere, thereby stabilizing the CO2 concentration. This interplay between outgassing and weathering rates is one of the fundamental negative climate feedbacks that is thought to keep the Earth’s climate within a relatively narrow range necessary to sustain the oceans and life (the mechanism known as the “Earth thermostat,” see Box 4.1). However, the rate of weathering depends not only on climate, but also on the area of newly exposed silicate rock. Weathering is therefore sensitive to the rate of uplift, and the general cooling trend during the millions of years prior to the Quaternary is attributed, at least in part, to increased uplift and enhanced weathering. While the interplay between CO2 outgassing and weathering may have played a rather minor role in glacial-interglacial CO2 variations, it controlled the average CO2 level during the Quaternary.

On orbital time scales of 104–105 years, other elements of the global carbon cycle begin to play a dominant role. During glacial cycles, most of the glacial-interglacial CO2 variability can only be explained by the redistribution of carbon between atmosphere, ocean and land. Both paleoclimate evidence and modeling results indicate that the carbon content of the terrestrial pool was significantly lower during glacial periods compared to preindustrial climates. Therefore, the only way to explain the low atmospheric CO2 during the glacial period is the increase in carbon stored in the ocean. The carbon content of the ocean is three orders of magnitude greater than that of the atmosphere, and even a small relative change in the carbon content of the ocean causes a significant change in the atmospheric CO2 concentration. Therefore, at first glance, it seems easy to explain the redistribution of about 200 GtC (gigatons of CO2 in carbon equivalent, which is ¼ of the total mass of CO2 in the atmosphere) between the ocean and atmosphere needed to reduce the atmospheric concentration by the observed 80 ppm. However, numerous attempts to simulate the observed glacial atmospheric concentration of CO2 have shown that this is not a trivial task, and a fully satisfactory understanding of how the carbon cycle operated during glacial cycles is still lacking.

Over the past few centuries, humanity has come to rely on fossil fuels as a primary source of energy. The burning of coal, oil and natural gas has increased the carbon content of the atmosphere (and therefore the concentration of CO2) by almost 50%. This increase is the main cause of anthropogenic global warming. Currently, about 500 GtC of fossil carbon have been used. Although the total amount of fossil fuel reserves is not known exactly, it may be an order of magnitude greater than the amount of fossil fuel used to date. However, using all available fossil fuels would raise atmospheric concentrations to levels comparable to the Eocene epoch 60 million years ago, leading to drastic climate change. Fortunately, recent developments make such a scenario increasingly unlikely. Following the complete cessation of fossil fuel burning, atmospheric CO2 concentrations will begin to fall. However, assuming no artificial removal of carbon from the atmosphere, it will take at least 100,000 years for the Earth system to return to its preindustrial state in terms of climate and CO2 concentration (see Box 8.1).

1.3.4 Methane and Nitrous Oxide Cycles

Methane is another important well-mixed greenhouse gas. It is much more efficient than CO2 in absorbing infrared radiation. In the distant past, before there was a significant increase in atmospheric oxygen concentration (the Great Oxidation Event, about 2 Ba), methane concentrations in the atmosphere were much higher and methane as a climate forcing played a role comparable to that of CO2. The development of an oxygen-rich atmosphere due to microbial photosynthesis, significantly increased the rate of methane removal from the atmosphere, and today the typical lifetime of atmospheric methane is only 10 years. As a result, the concentration of methane is three orders of magnitude lower than that of CO2. The main natural source of methane is tropical wetlands, with extratropical wetlands and other biological processes (such as termites) playing a secondary role. In turn, most methane is removed from the atmosphere by oxidation reactions that convert methane to CO2. Currently, fossil fuel combustion, landfills, waste and agriculture have more than doubled the atmospheric concentration of methane from 700 ppb (parts per billion) in preindustrial times to 1800 ppb today.

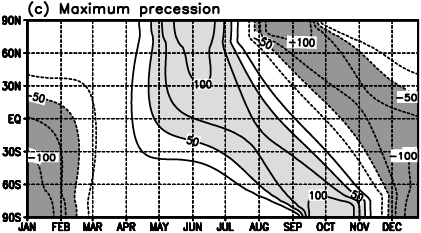

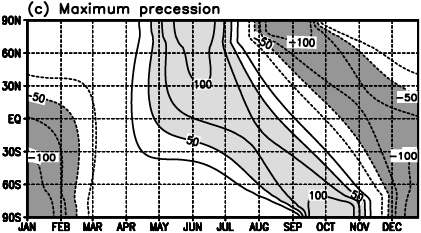

During glacial periods, methane concentrations fluctuate between 400 and 700 ppb fairly synchronously with other climate parameters such as CO2 and global ice volume. These variations are mostly attributed to changes in methane emissions from wetlands, which in turn are explained by lower glacial temperatures and precipitation. It is therefore not surprising that methane has a much stronger precessional component than CO2, since precession affects the strength of the hydrological cycle in the tropics. Methane concentration also has a strong millennial-scale variability, synchronous with Dansgaard–Oeschger events.

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is another well-mixed greenhouse gas that has contributed to both Quaternary and anthropogenic climate change. In nature, N2O is mainly produced by biological processes in the soil and ocean and removed by chemical reactions in the stratosphere. At present, anthropogenic N2O emissions, mainly from agriculture and fossil fuel combustion, are comparable to natural N2O production. As a result, the atmospheric concentration of N2O has increased by 25% since preindustrial times. Correspondingly, the N2O concentration during the glacial period was 25% lower than during preindustrial (i.e., interglacial) conditions. The lower glacial CH4 and N2O concentrations resulted in a global radiative forcing (compared to preindustrial) of about −0.3 W/m2 each, which are not negligible values, but still significantly smaller (in absolute value) than the −2 W/m2 caused by the glacial CO2 decrease.

1.3.5 Dust Cycle

The global dust cycle affects Earth’s physical and biogeochemical processes and plays a role in Quaternary climate variability. The aeolian dust is made of the smallest soil particles produced by the physical erosion of rocks. The main sources of dust today are deserts and semideserts. The dust particles are carried into the atmosphere when wind speeds are high enough. The large particles are deposited over a short distance, but smaller particles (order of micrometers) can be lifted several kilometers by atmospheric circulation and turbulence and then carried hundreds or even thousands of kilometers by the wind. Aeolian dust is gradually removed from the atmosphere by processes of gravitational deposition and wet deposition (by rain).

Dust particles in the atmosphere directly affect the climate by reflecting and absorbing both visible and infrared radiation. They also affect the energy balance of the Earth system through their effect on cloud formation by acting as cloud nucleation centers. At least in some ocean areas where iron is the limiting factor for biological marine productivity, dust deposition may be an important external source of iron.

It is very likely that aeolian dust played an even more important role during glacial times than it does today. First, most reconstructions of dust deposition suggest that glacial climates were much dustier than today, and modeling experiments indicate that global dust deposition doubled during glacial times. A number of factors are required to explain such a large increase in aeolian dust, as the drying of the glacial atmosphere alone is not sufficient. One possible reason is an increase in dust sources, in particular an increase in desert areas and sparser vegetation cover over semidesert and arid areas due to lower CO2 concentrations. Another potential source of glacial dust is exposed shelf areas caused by sea level lowering and areas near continental ice sheet margins, where significant amounts of dust could be produced by glacial erosion processes.

1.4 Climate, Climate Variability and Climate Change

1.4.1 Definitions of Climate, Climate Variability and Climate Change

Initially, the term climate referred only to the atmosphere, specifically to average weather conditions such as mean July temperature or annual precipitation. To obtain a sufficiently accurate average climatology, the World Meteorological Organisation defined climate by averaging meteorological characteristics over 30 years. Currently, the definition of climate is much broader and climate is defined by IPCC as “the statistical description (of the climate system) in terms of the mean and variability of relevant quantities.” In this sense, climate is a comprehensive statistical description of the current state of the climate system, and assumes that this state can evolve gradually over time. The temporal evolution of climate states on time scales much longer than individual weather events is usually referred to as “climate variability” or “climate change.” In theory, the term “climate change” should only be applied to time scales longer than the time chosen to define a climate state (decades), but the commonly used term “abrupt climate change” does not fit such a narrow definition, as abrupt climate changes have occurred on shorter time scales in the past. Prominent examples of climate variability that cannot be considered climate change are the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which has a typical periodicity of 3–6 years, the North Atlantic Oscillation (NOA), the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), and so forth. At the same time, glacial cycles can be described as both climate variability and climate change. Since this book is mostly concerned with processes that are much longer than weather (synoptic) processes, “climate variability” and “climate change” will be used as synonyms.

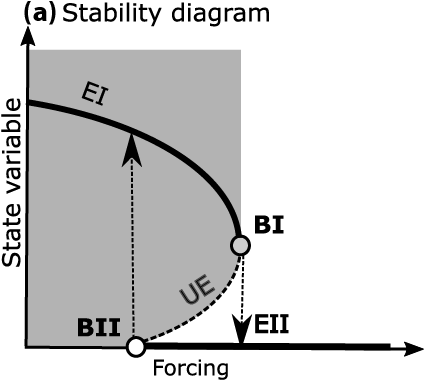

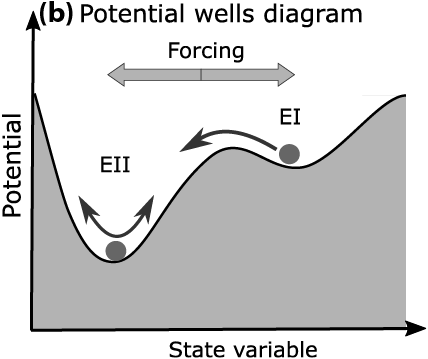

1.4.2 Internal and Externally Forced Climate Variability

Internal climate variability represents an intrinsic fluctuation in several components of the climate system on time scales much longer than the time scales of individual weather systems, which is not directly related to external climate forcings. Typical examples of such variability are ENSO, NOA and AMO. These types of variability have time scales of years to decades and distinct regional patterns. Reconstructions of the Earth’s climate over the last millennium show that natural climate variability has been rather weak (only a few tenths of a degree in terms of global temperature), which is consistent with the notion that interglacial climates are rather stable. This is not the case for glacial climates, which prevailed for most of the Quaternary. The strong millennial-scale climate variability associated with the Dansgaard–Oeschger events was also internal variability as no external forcing with relevant periodicities is known. At the same time, Quaternary glacial cycles are an example of externally forced climate variability or climate change. The forcing of glacial cycles is due to variations in summer boreal insolation, also known as orbital forcing. Another example of external climate forcing is volcanic eruptions. Although volcanoes are not external to the Earth system, they are not considered as a part of the climate system. The same applies to global tectonics, which affects the climate on very long time scales. Anthropogenic activity is also considered an external forcing, even though humans are physically inside the climate system. The interpretation of changes in CO2 concentrations depends on the context. During the Anthropocene, CO2 concentration is the primary forcing of anthropogenic climate change, and CO2 is considered an external forcing. The same is true for climate change on geological time scales related to temporal variations in volcanic CO2 outgassing. However, when considering glacial cycles, CO2 represents an internal feedback rather than an external forcing.

1.4.3 Natural Climate Variability and Anthropogenic Climate Change

The importance of understanding natural climate variability has been highlighted by former debates about the nature of observed climate change. Reconstructions of global mean near-surface air temperature based on meteorological observations clearly show a warming trend in both global and most regional temperatures over the last century, increasing confidence that observed climate change is unnatural. And if the first IPCC Assessment Report (IPCC 1990) stated that “unequivocal detection of the enhanced greenhouse effect from observations is unlikely for a decade or more,” the latest, the Sixth IPCC Assessment Report (IPCC Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pirani, Connors, Péan, Berger, Caud, Chen, Goldfarb, Gomis, Huang, Leitzell, Lonnoy, Matthews, Maycock, Waterfield, Yelekçi, Yu and Zhou2021a) makes a very strong statement in this regard: “It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land.” This increase in confidence in the attribution of observed climate change has occurred because (i) it has been shown that the amplitude of observed warming already significantly exceeds the natural climate variability observed over the past 100 years and reconstructed for the past 1000 years, and (ii) observed temperature trends are fully consistent with model results that include anthropogenic forcings and are inconsistent with simulations of natural climate variability alone over the same period. Natural climate variability still plays a role at regional scales, but globally anthropogenic forcing is the dominant factor in observed climate change since the end of the twentieth century and will remain the dominant factor in the foreseeable future.

1.5 Climate Forcings

1.5.1 Radiative and Other Climate Forcings

Many different factors influence climate on different time scales, and it would be natural to refer to such factors as “climate forcings.” However, the term “climate forcing” is often used as a synonym for “radiative forcing,” for example in the IPCC Glossary (IPCC Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pirani, Connors, Péan, Berger, Caud, Chen, Goldfarb, Gomis, Huang, Leitzell, Lonnoy, Matthews, Maycock, Waterfield, Yelekçi, Yu and Zhou2021b), even though the existence of other external forcings is recognized. Indeed, in the case of anthropogenic climate change, most climate forcings can be expressed in terms of their global impact on climate in units of intensity (W/m2). Radiative forcing is defined as the change in the global radiative balance at the top of the atmosphere caused by a change in the climate forcing under consideration, in the absence of other changes in the state of the climate system and associated climate feedbacks. For CO2, the definition of radiative forcing is slightly different – its radiative forcing is defined as the change in the radiative balance at the top of the atmosphere after the instantaneous adjustment of stratospheric temperature to the new CO2 concentration. Such a definition of CO2 radiative forcing is justified by the fact that the stratosphere responds very rapidly to changes in CO2 concentration, and such stratospheric adjustment causes an additional increase in the magnitude of CO2 radiative forcing. Although radiative forcing is a useful numerical characteristic that allows us to estimate and compare the global impact of different climate forcings, it is important to recognize that it is a purely theoretical characteristic that can only be derived from specially designed modeling experiments.

However, not all climate forcings that are important for understanding past and future climate change can be expressed in terms of radiative forcing. One such important forcing for Quaternary climate dynamics is the so-called “orbital forcing,” which is related to changes in the Earth’s orbital parameters: eccentricity, obliquity and precession (see Box 1.1). The Earth’s orbital parameters affect the spatial and temporal distribution of insolation, with changes expressed in units of intensity W/m2. However, the changes in global mean annual insolation caused by variations in orbital parameters are very small and irrelevant to the problems of Quaternary climate variability. Therefore, orbital forcing cannot be expressed in terms of global radiative forcing.

Apart from orbital forcing, there are several other important climate forcings that cannot be measured in terms of radiative forcing. One of these is the “freshwater forcing,” that is, an anomaly in the freshwater flux to the ocean, which can significantly affect ocean circulation and meridional ocean heat transport, and thus regional climate. Another example is “orographic forcing.” For example, the uplift of Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau about 10 million years ago affected regional climate and strengthened the Indian summer monsoon. Similarly, the growth of ice sheets during glacial cycles affected climate not only through changes in surface albedo (this aspect can be measured as radiative forcing), but also through changes in atmospheric and oceanic circulation. In addition, the waning and waxing of continental ice sheets affect climate regionally and globally through changes in sea level and hence an area of the ocean surface. Changes in the vegetation cover, both natural and anthropogenic (land use), affect climate in many ways, particularly through changes in surface albedo, surface roughness, and evapotranspiration.

Depending on which components of the Earth system are modeled and which are prescribed, the same components of climate can be considered as forcings or internal feedbacks. For example, in the case of modeling the climate of the Last Glacial Maximum, ice sheets and atmospheric CO2 concentration should be prescribed based on empirical data, and they are treated as climate forcings. However, in the case of simulating glacial cycles with the Earth system models, where ice sheets and the global carbon cycle are part of the model, their temporal evolution represents several important feedbacks to the only external forcing – the orbital forcing.

1.5.2 Solar Luminosity

As noted earlier, solar luminosity (energy output per unit time) has increased by about 25% over the past 4 billion years (Bahcall et al. Reference Bahcall, Pinsonneault and Basu2001). Since the mean distance of the Earth from the Sun has remained virtually constant over time, a 1% change in solar luminosity at today’s global mean planetary albedo of about 0.3 corresponds to a global radiative forcing of 2.5 W/m2, which is comparable to the radiative forcing of a doubling of CO2. Thus, changes in solar luminosity are important climate forcings on very long time scales (108–109 years), but not for the Quaternary.

In addition, solar luminosity varies on much shorter time scales, such as the 11-year cycle. Total solar irradiance has only been measured by satellites since the late 1970s, and before that can only be reconstructed from indirect proxies. The 11-year cycle results in very small (ca. 0.1%) variations in solar irradiance, and there is no evidence that solar irradiance has changed more significantly over longer solar cycles (Lean Reference Lean2018). Thus, the expected direct contribution of solar irradiance change to global temperature is well below 0.2°C. It is important to recognize that solar cycles result not only in very small changes in total solar output, but also in much larger (relative) redistributions of energy between visible and UV radiation. The consequences of these changes are not yet fully understood, but at present there is no convincing evidence that solar cycles are important for understanding Quaternary climate variability.

1.5.3 Orbital Forcing

The term “orbital forcing” refers to changes in the spatial-temporal distribution of insolation due to changes in the Earth’s orbital parameters (eccentricity and precession) and the tilt of the Earth’s axis of rotation relative to the plane of rotation (obliquity). The causes for these changes is the influence on Earth from the celestial bodies, primarily the Sun, Moon, Jupiter and Saturn. While changes in orbital parameters cause significant variations in insolation for a given season and latitude, the global, annual mean changes in insolation are very small (order of 0.1% of the solar constant). This makes orbital forcing different from other climate forcings, such as CO2 concentration or solar luminosity. Although orbital forcing has always been present and has affected the Earth’s climate, only during certain periods (and the Quaternary is the prominent example) has this forcing become the primary cause of climate variability.

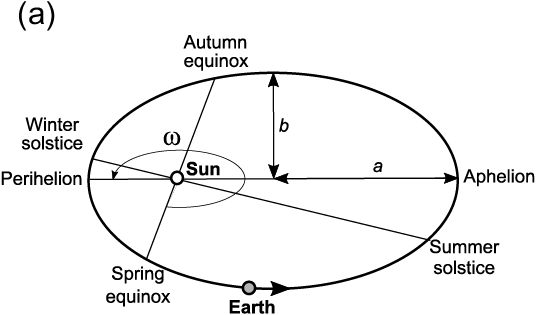

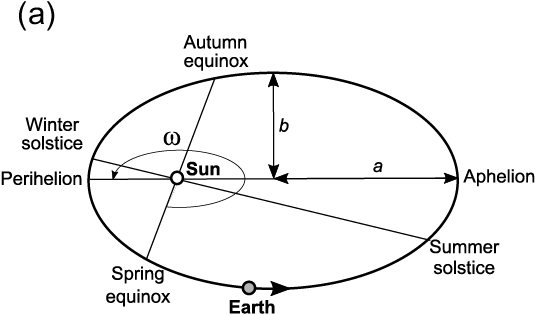

According to Kepler’s laws, the Earth moves around the Sun in an ellipse, and the Sun is at one of the foci of this ellipse. The interaction between the Earth and other celestial bodies causes the Earth’s orbit to change over time. The first orbital parameter is eccentricity, the measure of the elongation of the ellipse (see Figure 1.7). The eccentricity typically varies between 0.01 and 0.05. The current value of eccentricity (e = 0.0167) is much smaller than the average one and Earth’s orbit is now almost circular. Changes in eccentricity occur at several periods: 95, 124, 400 kyr and about 2 million years. Changes in eccentricity affect the annual mean insolation, but these changes are very small (Paillard Reference Paillard2001). However, during the last million years, the dominant periodicity of glacial cycles (both ice volume and global temperature) was 100 kyr, which is very close to one of the eccentricity periods. Therefore, there is little doubt that eccentricity does play an essential role in the late Quaternary climate dynamics, but does it indirectly, through amplitude modulation of the precessional component of orbital forcing.

(a) Parameters of the Earth orbit. Here, a is the semimajor and b is the semiminor axis which defines the eccentricity ![]() . The angle between vernal (NH spring) equinox and perihelion

. The angle between vernal (NH spring) equinox and perihelion ![]() is called the climatic precession.

is called the climatic precession.

Figure 1.7(a)Long description

Schematic representation of the Earths orbit around the Sun, which is located at one of the focal points of the ellipse. The position of key elements of the orbit: aphelion, perihelion, summer and winter solstices, and spring and autumn equinoxes. The semimajor and semiminor axes of the ellipse determine the eccentricity of the Earths orbit. The angle between the vernal equinox and perihelion is called the climatic precession.

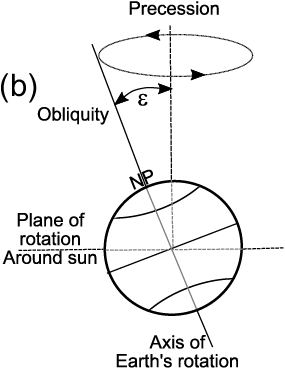

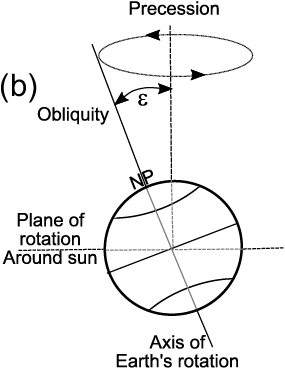

(b) The precession of Earth’s axis with respect to the orbital plane, where ![]() is obliquity.

is obliquity.

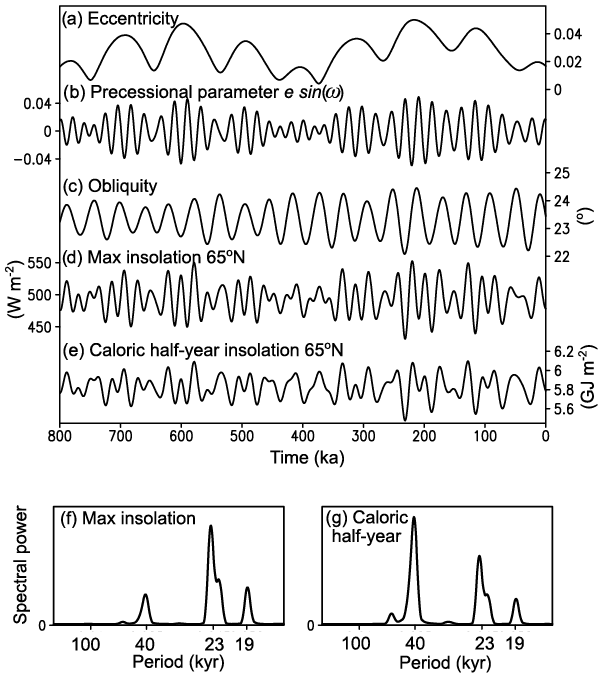

Figure 1.7(b)Long description