1. Introduction

The end-Permian mass extinction (EPME) and the subsequent prolonged recovery were primarily triggered by the massive volcanic activity of the Siberian Traps magmatism (STM) (Svensen et al. Reference Svensen, Planke, Polozov, Schmidbauer, Corfu, Podladchikov and Jamtveit2009). This volcanism released immense quantities of greenhouse gases, sulphur compounds and halogens in rapid, repeated pulses that destabilized global environments. On land, the principal kill mechanisms included intense acid rain, ozone layer destruction leading to elevated UV-B radiation, mercury poisoning and abrupt global warming (Black et al. Reference Black, Lamarque, Shields, Elkins-Tanton and Kiehl2014; Li et al. Reference Li, Frank, Xua, Fielding, Gong and Shen2022; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Peng, Marshall, Lomax, Bomfleur, Kent, Fraser and Jardine2023; Dal Corso et al. Reference Dal Corso, Newton, Zerkle, Chu, Song, Song, Tian, Tong, Di Rocco, Claire, Mather, He, Gallagher, Shu, Wu, Bottrell, Metcalfe, Cope, Novak, Jamieson and Wignall2024). These stresses caused the widespread collapse of terrestrial ecosystems and a prolonged delay in ecological recovery (Galfetti et al. Reference Galfetti, Hochuli, Brayard, Bucher, Weissert and Vigran2007; Stanley, Reference Stanley2009). Direct evidence for acidification and its latitudinal control on land during the EPME is, however, very scarce (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Zhang, Ramezani, Zhang, Erwin, Feng, Shao, Cai, Zhang, Xu and Shen2024). The effects of the STM that triggered the EPME (Payne et al. Reference Payne, Lehrmann, Wei, Orchard, Schrag and Knoll2004; Wignall, Reference Wignall2011) lasted until the end of the Early Triassic due to different intense pulses in activity (Svensen et al. Reference Svensen, Planke, Polozov, Schmidbauer, Corfu, Podladchikov and Jamtveit2009). The biotic crisis of the Smithian–Spathian boundary (SSB) was the result of one of these volcanic pulses and one of the last barriers to the onset of biotic recovery after the EPME (Galfetti et al. Reference Galfetti, Hochuli, Brayard, Bucher, Weissert and Vigran2007; Payne et al. Reference Payne, Lehrmann, Wei, Orchard, Schrag and Knoll2004; Posenato, Reference Posenato2019; Sahney and Benton, Reference Sahney and Benton2008).

During the last decade, SSB research constrained the effects of acidity on continental basins near the equator and the possible relationship between acidity and the circulation of volcanic aerosols due to global wind circulation (Galán-Abellán et al . Reference Galán-Abellán, Barrenechea, Benito, De La Horra, Luque, Alonso-Azcárate, Arche, López-Gómez and Lago2013 a; Borruel-Abadía et al. Reference Borruel-Abadía, Barrenechea, Galán-Abellán, Alonso-Azcárate, De La Horra, Luque and López-Gómez2016, Reference Borruel-Abadía, Barrenechea, Galán-Abellán, De La Horra, López-Gómez, Ronchi, Luque, Alonso-Azcárate and Marzo2019; Barrenechea et al. Reference Barrenechea, Gianolla, López-Gómez, Borruel-Abadía, De La Horra and Ronchi2025). In this study, we present new data from a global latitudinal reconstruction of the acidity conditions in continental environments for the SSB, based on the quantification of strontium-rich hydrated aluminium phosphate–sulphate (APS) minerals that typically precipitate at low pH conditions (Dill, Reference Dill2001; Stofreggen and Alpers, Reference Stoffregen and Alpers1987). The results reveal a global pattern of environmental stress that could have emanated latitudinal from the uneven distribution of aerosols derived from STM.

1.a. Geological context

The Early Triassic (∼251.9 to ∼247.2 Ma) was characterized by three large-scale negative shifts in δ13C ratios in marine carbonates (Payne et al. Reference Payne, Lehrmann, Wei, Orchard, Schrag and Knoll2004). These excursions have been linked to episodes of massive CO2 outgassing from the STM that likely produced ocean acidification, global warming and widespread anoxia/euxinia, with the largest occurring near the SSB. This latter episode also coincided with the extinction of ammonites and conodonts (Orchard, Reference Orchard2007) and impeded complete biotic recovery during the Early Triassic (Sahney and Benton, Reference Sahney and Benton2008).

On land, these pulses correlate with similar excursions reported from paleosol data (Retallack, Reference Retallack2021), with a drastic modification in the spore-pollen assemblages (Galfetti et al. Reference Galfetti, Hochuli, Brayard, Bucher, Weissert and Vigran2007). In the continental realm, the massive release of CO2 and other volcanic greenhouse gases from the STM generated sustained global warming and acid rain. In addition, episodic pyroclastic eruptions caused further sulphuric acid rain and ozone depletion, which in turn may have severely damaged the global environment, leading to the terrestrial biotic crisis (Black et al. Reference Black, Lamarque, Shields, Elkins-Tanton and Kiehl2014; Li et al. Reference Li, Frank, Xua, Fielding, Gong and Shen2022; Dal Corso et al. Reference Dal Corso, Newton, Zerkle, Chu, Song, Song, Tian, Tong, Di Rocco, Claire, Mather, He, Gallagher, Shu, Wu, Bottrell, Metcalfe, Cope, Novak, Jamieson and Wignall2024). Furthermore, Paterson et al. (Reference Paterson, Rossi and Schneebeli-Hermann2024) report increased concentrations of As, Co, Hg and Ni, which is interpreted as compelling evidence for heavy metal-induced stress and genetic disturbance in plant communities during the EPME. The SSB activity of the STM is widely considered to have the most severe paleoenvironmental effects in the Early Triassic (Retallack et al. Reference Retallack, Sheldon, Carr, Fanning, Thompson, Williams, Jones and Hutton2011). In this context, the presence of APS minerals in continental rocks can provide insight into the environmental conditions that prevailed during the SSB crisis and the biotic recovery that followed. These minerals belong to the alunite supergroup and are stable under conditions of high (PO₄)3⁻ activity, high oxygen potential and relatively low pH values (Dill, Reference Dill2001; Vieillard et al. Reference Vieillard, Tardy and Nahon1979; Stoffregen and Alpers, Reference Stoffregen and Alpers1987). As recently shown in the SSB continental rocks of the W peri-Tethys, where APS formation is texturally constrained to follow the sedimentation process, relative proportions of APS minerals could reflect the duration and intensity of the acidification process (Barrenechea et al. Reference Barrenechea, Gianolla, López-Gómez, Borruel-Abadía, De La Horra and Ronchi2025; Borruel-Abadía et al. Reference Borruel-Abadía, Barrenechea, Galán-Abellán, Alonso-Azcárate, De La Horra, Luque and López-Gómez2016, Reference Borruel-Abadía, Barrenechea, Galán-Abellán, De La Horra, López-Gómez, Ronchi, Luque, Alonso-Azcárate and Marzo2019). Here, we address the acidity peaks that occurred on land during the SSB globally, encompassing several new locations at different latitudes.

2. Methods

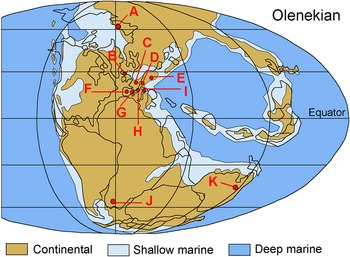

We selected Smithian–Spathian sequences across a wide paleolatitude range, including nine outcrop sections and three drill cores (Figure 1). This selection completes previous detailed studies on a much larger number of sections in the Iberian Basin, the Catalan Basin – Minorca (Spain), the Nurra Basin (Sardinia, Italy) and the Western Dolomites (Vicentinian Prealps, Italy) (Barrenechea et al. Reference Barrenechea, Gianolla, López-Gómez, Borruel-Abadía, De La Horra and Ronchi2025; Borruel Abadía et al. Reference Borruel-Abadía, Barrenechea, Galán-Abellán, Alonso-Azcárate, De La Horra, Luque and López-Gómez2016, Reference Borruel-Abadía, Barrenechea, Galán-Abellán, De La Horra, López-Gómez, Ronchi, Luque, Alonso-Azcárate and Marzo2019; Galán-Abellán et al. Reference Galán-Abellán, Barrenechea, Benito, De La Horra, Luque, Alonso-Azcárate, Arche, López-Gómez and Lago2013a). A total of 179 fine-grained sandstone samples were analysed, mostly of continental origin, but also from transitional to shallow marine environment in one drill core (Figure 2 and Supplementary material). All our sections are temporally and spatially constrained based on terrestrial palynomorph and tetrapod assemblages or magnetostratigraphy. The sedimentary facies for the studied subunits are similar across all stratigraphic sections (Table S1, Supplementary material), indicating the distribution of APS and organic preservation are not facies-dependent. Most of the studied successions correspond to siliciclastic rocks, and only the section of the Western Dolomites (Italy) shows layers of carbonate rocks towards the top of the section.

Figure 1. Pangea during the Olenekian, which includes the Smithian and the Spathian. A to K: location of the outcrop sections and drill cores of Figure 2.

The chemical composition of APS minerals was analysed with an electron microprobe analyser (EMPA) JEOL JXA-8900 M WDS. We quantified APS minerals based on EMPA elemental maps following the methodology of Borruel-Abadía et al. (Reference Borruel-Abadía, Barrenechea, Galán-Abellán, Alonso-Azcárate, De La Horra, Luque and López-Gómez2016). Textural relationships were described using a JEOL 6400 scanning electron microscope (SEM), equipped with an energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS). Additional data on texture and composition of the samples were obtained in a TESCAN Vega 4 SEM (high/low vacuum) operating at 20 kV with colour cathodoluminescence and two EDX Bruker detectors (30 and 60 mm2).

3. Results and discussion

When present, APS minerals show very similar textural and compositional characteristics in the different sections studied (Figure 3). They occur as small (0.2–5 µm), disseminated, euhedral, pseudocubic crystals or as polycrystalline aggregates (up to 200 µm). Their idiomorphic nature and delicate stepped faces rule out a detrital origin. Textural relationships indicate that the precipitation of diagenetic quartz and illite cement postdates the formation of APS minerals and suggests the replacement of metamorphic rock fragments and detrital micas occurred before the main stage of compaction of the sedimentary pile. All these features were first described in detail in many sections in the Iberian Ranges (Spain) by Galán-Abellán et al. (Reference Galán-Abellán, Barrenechea, Benito, De La Horra, Luque, Alonso-Azcárate, Arche, López-Gómez and Lago2013 a) and were later reported in the Catalan Coastal Range, Minorca (Spain), Sardinia (Italy) (Borruel-Abadía et al. Reference Borruel-Abadía, Barrenechea, Galán-Abellán, Alonso-Azcárate, De La Horra, Luque and López-Gómez2016) and the Western Dolomites (Italy) (Barrenechea et al. Reference Barrenechea, Gianolla, López-Gómez, Borruel-Abadía, De La Horra and Ronchi2025). They concluded that APS minerals formed during early-diagenetic stages, shortly after sedimentation and most likely under the influence of acidic meteoric waters.

Figure 3. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images from sample MG7 (Dolomites, Italy): (a) euhedral crystals of APS minerals surrounded by quartz and illite. (b) APS crystals and moulds within the quartz cement (white arrow). (c) Backscattered electron (BSE) image in a thin section of sample MG1, with small APS minerals and detrital mica plates replaced by kaolinite. (d) Kaolinized mica with disseminated APS minerals. (e) BSE image of a thin section of sample V48 (W German basin). The white arrows point to APS mineral crystals in the clay matrix. (f) Enlarged view of crystals of APS minerals, closely related to the kaolinized detrital mica (white arrow). (g) Plot of APS mineral compositions from Dolomites and from the W German basin compared to previously published data from other peri-Tethyan basins. Q: quartz; Feld: feldspar; Kaol: kaolinite; APS: APS mineral.

Our results show a clear latitudinal control on the concentration of APS minerals (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S2). This cannot be ascribed to variations in grain size since all studied sequences are lithologically and texturally similar. The formation of APS minerals primarily depends on acidic conditions, which in turn may have been favoured by a warm, seasonal climate. Although Galán-Abellán et al. (Reference Galán-Abellán, Alonso-Azcárate, Newton, Bottrell, Barrenechea, Benito, De La Horra, López-Gómez and Luque2013 b) suggested that pyrite oxidation could enhance acidity, they also considered a potential contribution from volcanic aerosols. While isotopic data confirming a volcanic origin for these aerosols are lacking, the remarkable textural and compositional uniformity of APS across sections separated by thousands of kilometres indicates a common formation mechanism operating at a scale broader than strictly local. Furthermore, the absence of carbonate layers in most of the studied sites suggests a limited influence of their potential buffering capacity against the low pH induced by volcanic inputs of acidic gases. In fact, this influence should only be considered in the Western Dolomites section, which contains carbonate layers, but the APS minerals are found only in the siliciclastic strata of fluvial origin (Supplementary Table S1). On the other hand, sections with sporadic marine influence may have been affected by the buffering effect of seawater, which could bias the interpretation of the presence of APS minerals as indicators of increased acidity. We consider it unlikely that this buffering effect influences the decreasing trend in APS mineral contents towards higher latitudes, given the overall predominance of continental facies in these sections. However, it cannot be ruled out that it may have some impact on the successions with greater marine influence.

Figure 4. Volume fraction of APS minerals across the studied sections (this study) together with biotic ammonoid and conodont (Stanley, Reference Stanley2009) and flora (Hochuli et al. Reference Hochuli, Sanson-Barrera, Schneebeli-Hermann and Bucher2016) changes and simplified carbon isotope signatures (Payne et al. Reference Payne, Lehrmann, Wei, Orchard, Schrag and Knoll2004) during the Early and Middle Triassic. For the sake of clarity, volume fraction of APS minerals data from equatorial latitudes has been split into two separate columns, one for the Iberian Ranges and another for the Catalan Ranges, Minorca, N Sardinia and Dolomites. (See Supplementary Table S2 for complementary information).

Across the SSB, contents greater than 0.1 vol.% are detected around the equatorial zones, in the W peri-Tethys basins, while the concentration of these minerals decreases drastically towards higher latitudes, being practically non-existent from 40º N and 40º S onwards. In the W peri-Tethys, trends in the APS minerals are consistent in all outcrop sections and drill cores (Figure 4). APS variations through time are also clear. The oldest studied samples have low concentrations in APS minerals but increase substantially across the SSB in all studied basins (from 0.09 to 1.07 vol.%) (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S2). The highest APS mineral contents are observed in the Iberian Basin, central Spain, located near the equator, about 10º N–14º N (Borruel-Abadía et al. Reference Borruel-Abadía, Barrenechea, Galán-Abellán, Alonso-Azcárate, De La Horra, Luque and López-Gómez2016), where no remains of fauna or flora have been found so far in the Smithian–Spathian sedimentary record (Borruel-Abadía et al. Reference Borruel-Abadía, Barrenechea, Galán-Abellán, De La Horra, López-Gómez, Ronchi, Luque, Alonso-Azcárate and Marzo2019). Such high APS mineral levels persist until the late Spathian, where bioturbation processes appear as first signs of life recovery. In the lower-middle Anisian successions, APS mineral percentages are low in this basin (between 0.006 and 0.09 vol.%), and this decrease coincides with the first occurrence of paleosols, bioturbations, plant remains, tetrapod footprints and insects (Borruel-Abadía et al. Reference Borruel-Abadía, López-Gómez, De La Horra, Galán-Abellán, Barrenechea, Arche, Ronchi, Gretter and Marzo2015) (Figure 4). A similar trend occurs in Sardinia (Italy), in latitudes similar to Iberia, where high APS mineral content (0.04–0.18 vol.%) also coincides with the absence of flora and fauna during the SSB, and the first signs of life appear only in the late Spathian (Baucon et al. Reference Baucon, Ronchi, Felletti and De Carvalho2014). In a recent work, Barrenechea et al. (Reference Barrenechea, Gianolla, López-Gómez, Borruel-Abadía, De La Horra and Ronchi2025) report the same pattern of APS mineral distribution with respect to the lack of indicators of organic activity in the Western Dolomites, also in sub-equatorial latitudes. The absence of fossils in these continental W peri-Tethys areas also coincides with extreme temperatures and hyperarid environmental conditions (Bourquin et al. Reference Bourquin, Bercovici, López-Gómez, DIEZ, Broutin, RONCHI, Durand, Arché, Linol and Amour2011).

Towards higher latitudes, the APS mineral content drops rapidly (Figure 4). Rare disseminated crystals occur in samples near the SSB in NE France and central Germany, with a maximum APS mineral concentration of 0.101 vol.%. In N Germany, the concentration is 0.0124 vol.%, and in the Solway Basin (UK), the maximum content is 0.0026 vol.%. The Spathian sedimentary record of French and English successions shows no fossil remains, only some signs of bioturbation in the Vosges Mountains (NE France) (Bourquin et al. Reference Bourquin, Guillocheau and Péron2009) and possible vertebrate footprints in the Solway Basin (Brookfield, Reference Brookfield2004) in the middle Spathian sedimentary record. However, the German succession for these ages contains plant remains, conchostracans and acritarchs (Aigner and Bachmann, Reference Aigner and Bachmann1992). This decreasing trend in APS mineral content continues northwards, and the Boreal area (Barents Sea, Norway) (Rossi et al. Reference Rossi, Paterson, Helland-Hansen, Klausen and Eide2019) is practically devoid of APS minerals. In contrast to areas at lower latitudes, temperature and acidity conditions in the Boreal area were not as extreme during the SSB (Woods, Reference Woods2005). So, even though paleontological evidence indicates a synchronous major change in terrestrial and marine ecosystems near the SSB, this area might be regarded as a most likely refuge of plants and of early recovery during the Early Triassic (Galfetti et al. Reference Galfetti, Hochuli, Brayard, Bucher, Weissert and Vigran2007), allowing deciduous forests and temperate paleosols (Retallack et al. Reference Retallack, Sheldon, Carr, Fanning, Thompson, Williams, Jones and Hutton2011).

As in the Boreal areas, virtually no APS minerals have been found in the southern high-latitude studied sections of South Africa and E Australia during the SSB (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S2). In these areas, the presence of different types of fossils (Smith and Botha-Blink, Reference Smith and Botha-Blink2014; Retallack, Reference Retallack2021) shows that the consequences of damaged environmental conditions were not as marked as in low latitudes. The chemical composition of paleosols and stomatal index of fossil plants in the Bowen Basin, E Australia, reveals this CO2 crisis coincided with elevated temperatures and precipitation, but also with opportunities for transient migrations of lycopsids and large amphibians to higher latitudes (Retallack et al. Reference Retallack, Sheldon, Carr, Fanning, Thompson, Williams, Jones and Hutton2011). During the middle Smithian, Dicroidium leaves and dispersed cuticles become common in the central Sydney Basin (65º–70ºS) and persisted throughout the remainder of the Triassic in E Australia, becoming a dominant component of coal-forming mire ecosystems in the Middle and Late Triassic (Fielding et al. Reference Fielding, Frank, Mcloughlin, Vajda, Mays, Tevyaw, Winguth, Winguth, Nicoll and Bocking2019).

Our results are consistent with global patterns of biotic activity documented during the Early Triassic, although the differences between the mechanisms and effects operating in marine and continental realms must be taken into account. At the end-Smithian, there were major losses in many marine groups, including bivalves, conodonts and ammonoids (Stanley, Reference Stanley2009). Fish fossils are very rare in equatorial areas, especially in the Smithian successions, despite being common at higher latitudes at the time (Sun et al. Reference Sun, Joachimski, Wignall, Yan, Chen, Jiang, Wang and Lai2012). Marine reptile fossils (ichthyosaur) are also not found in equatorial waters until the middle-late Spathian (Sun et al. Reference Sun, Joachimski, Wignall, Yan, Chen, Jiang, Wang and Lai2012). Other notable absences from equatorial oceans are calcareous algae during the entire end-Permian–early Spathian interval, although they are present in higher latitudes (Wignall et al. Reference Wignall, Morante and Newton1998). The increase in temperature and acidity in the oceans has a direct relationship with the atmospheric increase in CO2 (Wignall, Reference Wignall2011).

On land, tetrapod fossil occurrences are generally absent between 30°N and 40°S during the Early Triassic (Romano et al. Reference Romano, Bernardi, Petti, Rubidge, Hancox and Benton2020). Moreover, in equatorial Pangea, conifer-dominated forests did not become established until the end of the Spathian (Looy et al. Reference Looy, Brugman, Dilcher and Visscher1999). The interval between the end of the Smithian and the end of the Spathian, during which acidic conditions prevailed, coincides with a phase of global warming (Bourquin et al. Reference Bourquin, Bercovici, López-Gómez, DIEZ, Broutin, RONCHI, Durand, Arché, Linol and Amour2011). The ultimate causes of global acidification remain uncertain, but the most plausible explanation involves the environmental impact of aerosols generated by STM activity (Payne et al. Reference Payne, Lehrmann, Wei, Orchard, Schrag and Knoll2004), which would have produced acid rain (Black et al. Reference Black, Lamarque, Shields, Elkins-Tanton and Kiehl2014) and contributed to widespread continental acidification (Galfetti et al. Reference Galfetti, Hochuli, Brayard, Bucher, Weissert and Vigran2007). The massive injection of CO2 into the atmosphere associated with Siberian volcanism is considered to have driven this global warming (Hochuli et al. Reference Hochuli, Sanson-Barrera, Schneebeli-Hermann and Bucher2016) and to have sustained episodes of acid rainfall with comparable effects in both hemispheres, as modelled by Black et al. (Reference Black, Lamarque, Shields, Elkins-Tanton and Kiehl2014) for the EPME. These authors also emphasized that acid rain and the global collapse of the ozone layer, linked to episodic pyroclastic volcanism and heating of volatile-rich Siberian country rocks, generated repeated and rapidly imposed atmospheric stresses that contributed to terrestrial ecological collapse. Sulphur injected during these eruptions can sharply decrease pH once eruptive activity ceases. The mechanisms inferred for the EPME likely remained active during the Early Triassic pulses (Svensen et al. Reference Svensen, Planke, Polozov, Schmidbauer, Corfu, Podladchikov and Jamtveit2009), thereby delaying biotic recovery until the SSB. We suggest that APS mineral precipitation is closely related to these recurrent episodes of sulphur injection into the atmosphere. According to the model of Black et al. (Reference Black, Lamarque, Shields, Elkins-Tanton and Kiehl2014), enhanced acidity in equatorial regions is likely governed by wind circulation patterns and regional precipitation totals. The configuration of the Pangean landmass during the Early Triassic may have disrupted zonal circulation (Kutzbach and Gallimore Reference Kutzbach and Gallimore1989), and seasonal temperature contrasts between hemispheres may have produced pressure gradients that drove cross-equatorial airflow (Parrish, Reference Parrish1993). These conditions may have facilitated the migration of volcanic aerosols from the STM towards lower latitudes during the SSB, where surface acidity and associated environmental impacts intensified. Acid rain derived from sulphate aerosols would have been particularly strong in the Northern Hemisphere, with its most pronounced effects between the equator and 60°N (Black et al. Reference Black, Lamarque, Shields, Elkins-Tanton and Kiehl2014). This is likely because acid gases (HF, HCl and SO2) are attenuated during long-distance transport, which may help explain the scarcity of APS minerals in Southern Hemisphere sections.

Although arid climatic conditions may have contributed to sustaining environmental acidity, the presence of APS minerals in the study areas does not depend exclusively on climatic variability. During the arid pulse at the end of the Spathian, no increase in APS minerals is observed; the establishment of a semi-arid climate took place only after APS concentrations had already declined.

Our study offers an approach for estimating acidity in continental sequences and for evaluating its impact on environmental change and ecosystem recovery. Acidity contributed to the SSB biotic crisis and moderated the recovery after the EPME, with variable impacts on Pangea ecosystems depending on their paleolatitude. The high APS contents at the SSB in equatorial areas strongly suggest that pulses of highly acidic conditions conducive to APS formation likely persisted for longer and were more intense than those recorded in higher latitude sections.

The Early Triassic provides a unique deep-time perspective on the precarious balance between life and acid conditions depicted during SSB major environmental changes. The APS distribution across global continental records confirms acidity levels during the SSB were decisive for the onset of life recovery after the EPME. Acidity levels were conditioned by latitude, with the SSB biotic crisis having lower environmental impact in high latitudes, where recovery was therefore faster. Acidic conditions did not return to SSB levels during the Middle Triassic, allowing environmental recovery after the EPME.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756825100472

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Exploration Data Centre of the Department of Resources, Queensland Government (Australia), for assistance in core retrieval, investigation and sampling, and the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate for permission to sample well 7226 11-1. They also appreciate the technical assistance of the National Center for Electron Microscopy (Madrid) for EMPA and SEM analysis. Constructive criticism from an anonymous reviewer helped to improve the manuscript.

Financial support

The authors are grateful for the financial support of the projects PID2022-141050NB-I00 (Spain), PRIN 2022–24 (Italy) and ARC FT230100230 (Australia).

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests as defined by the journal or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and/or discussion reported in this paper.

Author contributions

JFB and JLG: Original proposal and coordination of the study. Field work and sample collection in the Iberian Ranges, Catalonia, Minorca (Spain), Sardinia, Dolomites (Italy), West and East German Basins (Germany) and Bowen Basin (Australia). Drafting of the manuscript and drawing of figures. VBA: Field work and sample collection in the Iberian Ranges, Minorca (Spain), Sardinia and Dolomites (Italy). Determination of APS mineral content by EMPA. Drafting of the manuscript and drawing of figures. ABGA: Field work and sample collection in the Iberian Ranges and Catalonia (Spain) and West German Basin (Germany). Discussion and input on the draft manuscript. FJL: Sample processing and mineralogical study. Discussion and input on the draft manuscript. RHB: Field work and sample collection in the Iberian Ranges, Minorca, Catalonia (Spain), Sardinia and Dolomites (Italy). Discussion and input on the draft manuscript. TU and JE: Field work and sample collection in the Bowen Basin (Australia). Discussion and input on the draft manuscript. AR: Field work and sample collection in the Nurra Basin (Sardinia, Italy). Discussion and input on the draft manuscript. PG: Field work and sample collection in the Dolomites (Italy). Discussion and input on the draft manuscript. NP y VMR: Sample collection in the Western and NW Barents Sea (Norway). Discussion and input on the draft manuscript. TMC: Field work and sample collection in the East German Basin (Germany). Discussion and input on the draft manuscript. RMHS and DW: Field work and sample collection in the Central Karoo Basin (South Africa). Discussion and input on the draft manuscript. SB: Sample collection in the Vosges Mountains (France). Discussion and input on the draft manuscript. MB: Field work and sample collection in the Solway Basin (UK). Discussion and input on the draft manuscript.

Data availability statement

Data are provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.