Introduction

Difficult though it might be to comprehend from the fragmentary remains, we have to imagine a world in which prior to the Reformation, virtually every one of the more than ten thousand parish churches in England was filled with stained glass.Footnote 1

Stained-glass windows were integral to the late medieval parish church building and its décor. As Richard Marks explains, they were once a universal feature. Yet it is due to the presence of fragmentary remains and historical records of lost medieval glass, and not in spite of their existence, that it is possible to imagine a world in which this was the case. In the south-west region of England alone, here encompassing the counties of Cornwall, Devon and Somerset (pre-1974), medieval glass survives and is documented in over two hundred parish churches to date.Footnote 2 It is clear from this and wider regional surveys on the medium that glazing was not reserved for the largest churches, or even the wealthiest and most populous settlements. Instead, it was a prominent part of everyday parochial visual culture. Together, the cobbled pieces and descriptions of ancient glass that survive afford the researcher insightful glimpses into a lost religious tradition practised in the locality, one centred on liturgical performance, vivid sensory engagement and devotional experience. They constitute a vital source of information on medieval worship that has yet to be interrogated to its fullest potential.

This article addresses the theme of margins and peripheries through the lens of stained glass in three methodological senses. Firstly, discussion deliberately focusses on stray pieces of glass and accounts of lost windows traditionally marginalized by the canon. Until recently, this privileged extant, innovative and coherent programmes of stained-glass windows that could more readily be studied in relation to conventional art historical lines of enquiry, such as the significance of style, the identification of workshops and the skill of individual craftsmen.Footnote 3 Within the English context, a significant proportion of the literature on stained glass has been dedicated to the collections of ‘great churches’, such as the cathedrals at Wells and Canterbury, and York Minster, or the exceptionally well-preserved sequences remaining in smaller churches, such as St Peter Mancroft in Norwich and St Mary’s Fairford (Gloucestershire).Footnote 4 Whilst the summary catalogues produced by the Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi have greatly enriched knowledge of smaller and displaced manifestations of glass situated within a wide range of ecclesiastic and domestic settings, the emphasis of their analysis remains on the documentation, provenance and classification of iconographic types, as opposed to the interpretation of meaning in light of late medieval spirituality.Footnote 5 Fragments need to be integrated into the conversation currently taking place in cathedral contexts around the role stained glass played in wider religious themes, such as the liturgy, devotional trends and the spiritual topography of the church building.Footnote 6

Secondly, this article pulls the parish church from the periphery to the heart of study. Despite the wave of revisionist interest in the medieval parish as a socio-spiritual body in the 1990s and 2000s, research into the architecture and materiality of the parish church building has considerably lagged behind that generated on cathedral, monastic and collegiate sites which stand as grander monuments with greater institutional status.Footnote 7 This neglect caused Paul Binski to argue in 1999 for the urgent need to focus scholarly attention on the English parish church and its furnishings, ‘rather than seeing it as some unfathomable, and perhaps embarrassing, epiphenomenon of something that was “really” going on elsewhere’.Footnote 8 Since the publication of this article, the roots of the parish church as an academic and popular object of study have been steadily growing, which has led to an appreciation that the structure and contents of these buildings were deeply embedded within the socio-religious life of their community.Footnote 9 However, there is much progress still to be made due to the sheer bulk of material to process in relation to questions of context, function and reception, within an architecturally diverse category of buildings numbering well into the thousands.Footnote 10

Finally, this article adopts the South-West as a regional case study as it occupies the geographic periphery of the country and is often popularly perceived as a cultural backwater. Aside from a handful of studies and individual scholars invested in the subject, the South-West is often sidelined in mainstream studies on pre-Reformation religious practice in favour of urbanized or populous centres with better records.Footnote 11 More specifically, research into the glazing of south-western England is particularly lacking, despite it hosting a diverse body of evidence from the recognizable windows of St Neot (Cornwall) to the lesser known collections of glass at Bampton (Devon) or Langport (Somerset).Footnote 12 Even the substantially complete survivals housed at Doddiscombsleigh (Devon) and St Kew (Cornwall) have yet to receive sustained scholarly study. The oldest extant glass to be found outside of a cathedral in the region dates to the early fourteenth century at Bere Ferrers (Devon), coinciding with the foundation of a collegiate community there.Footnote 13 Elsewhere, the majority of surviving material dates from the late fourteenth to early sixteenth centuries, corresponding with the late medieval drive to expand, redevelop and embellish the parish church building.Footnote 14 Unlike the dominant glazing centres of York and Norwich, the names and dates of glaziers operating in the area is not well documented.Footnote 15 However, the South-West is well-served with the written evidence of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century antiquarians that account for the subject matter and composition of stained-glass windows that have since been lost or altered due to modern restoration.Footnote 16 Thus, it is high time that the spotlight was turned upon the glazing of south-western England.

This article argues that an integration of marginalized stained-glass fragments and lost glass into the mainstream of academic debates on the tenor of pre-Reformation parochial spirituality not only substantially augments the body of evidence we have as an entry point into the subject, but also generates a better understanding of the multifaceted role the medium played in quotidian religious life. There are methodological and interpretive challenges when encountering isolated remains or decontextualized pieces, but there are also benefits. A glass fragment often refers to its totality, conveying ideas beyond itself and testifying to a missing tradition of glazing. The sheer variety of these pieces correct any assumptions of homogeneity or perfection created by the unique programmes of large churches. Combined with the written evidence of absent schemes, this idea of variety encourages the researcher to view the parish church on a continuum more broadly, as an active, evolving building.

The discussion of this article draws out and contextualizes three striking iconographic patterns that arise from a closer study of these sources. In doing so, this article does not intend to provide a comprehensive account of south-western glazing, but rather to provide an introduction to the available material and to pull at some of the interpretative threads that appear. It opens with the identification of Crucifixion scenes, exploring the significance of their proximity to altars and symbolic resonance with the mass. It proceeds with a consideration of scenes from the seven sacraments and their doctrinal value to the parish community. Finally, the article moves to examine evidence of narrative cycles and reflects upon their connection to devotional impulses.

Crucifixion Scenes

The Crucifixion was a popular subject to depict in stained glass, either as an isolated scene or as a component of the wider Passion story. It famously adorns the fifteenth-century and sixteenth-century east windows of Great Malvern Priory (Worcestershire) and St Mary’s Fairford, as well as having been intended for the chapel at Hampton Court Palace in London.Footnote 17 These pictorial imaginations of Christ’s life and death intersected with a growing devotional intensity towards the figure of Christ and the mass in the two centuries preceding the break with Rome.Footnote 18 The medieval liturgy was mediated through the senses, as it was an elaborate ceremony focussed on movement, song and recitation, giving life to the written word.Footnote 19 Above all, however, there was a special emphasis on sight. The spiritual and salvific potency of seeing the elevation of the consecrated host was such that it led the fourteenth-century Dominican friar John Bromyard to comment that if Christ himself were to walk into the church during the height of the canon he would have been missed.Footnote 20 For large ecclesiastic sites, such as the cathedrals of Beauvais and Chartres in France, as well as Wells in England, it has been observed that glazing formed a vital part of a sophisticated physical infrastructure designed to support the performance of the liturgy and reinforce visions of the elevated eucharist during the mass.Footnote 21 The evidence of fragments and lost schemes indicate that these observations are applicable to the stained-glass configurations of smaller churches.

The tradition of visualizing the Crucifixion in glass extended into the parish churches of the South-West of England. Christ is commonly depicted nailed to the cross in a central light flanked by figures of the weeping Virgin Mary and St John the Evangelist in neighbouring lights. Fuller or complete examples of this can be seen in the churches of St Catherine’s near Bath (Somerset), Kelly (Devon), St Winnow (Cornwall) and Winscombe (Somerset). These schemes are often both richly detailed and theologically sophisticated. For instance, at St Winnow, the Crucifixion is now set against plain glass (Figure 1). A skull and collection of bones appear in the ground beneath both the cross and the feet of the figures. Whilst accentuating the theme of death and sacrifice, these bones refer to Golgotha, or the place of a skull, as recounted in the canonical gospels, thereby setting the image in historical, biblical terms. The use of dark and dull colours further alludes to the eclipse which engulfed the land at the Son of God’s death. At Winscombe, two trees grow beside Jesus’ bleeding feet, an artistic motif denoting the tree of life and tree of knowledge of good and evil described in Genesis 2: 9 (Figure 2). The glass thus visualizes the restoration of Eden and salvation of humanity achieved through Christ’s redemptive act on the cross, a lifegiving tree.Footnote 22 In the tracery lights above, a collection of angels upholds shields exhibiting the instruments of Christ’s torture. Reading from left to right, these emblems are: a crown of thorns, a robe and dice, three nails, a ladder with a hammer and pincers, a pillar with two whips, and the cross. The shields refer to pivotal moments in Christ’s torment, such as the flagellation, thus symbolically guiding the viewer through the journey which led to Calvary.

Figure 1. Crucifixion window, St Winnow’s parish church, St Winnow, Cornwall. © The author.

Figure 2. Crucifixion window, St James’ parish church, Winscombe, Somerset. © The author.

The testimony of fragments strengthens this pattern of survival and reveals the widespread nature of this iconography. Fragments denoting this lost subject matter are easier to identify due to the highly recognizable set of motifs and symbolism often deployed. For instance, the scant shards of glass remaining in the east window at Creed display the side of Christ’s head with faint traces of the crown of thorns alongside a pierced hand shedding blood (Figure 3). Christ’s nailed hand is repeated in the east window’s tracery of St Tudy (Cornwall). Meanwhile, in the south transept at Lamorran (Cornwall) a collection of glass contains the images of two skulls and some bones, reminiscent of those described at St Winnow. Sometimes, larger sections of the cross or of Christ’s dying figure upon it survive, as at Laneast (Cornwall) (Figure 4). At Dinder (Somerset), the upper half of the cross inscribed with the letters INRI can be identified amongst a collection of fragments situated in a window over the pulpit which also showcases remains of the Holy Trinity. INRI stands for the mock title Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum, or ‘Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews’, bestowed upon Jesus by Pontius Pilate (John 19: 19). In other locations, all that remains are the mournful outlines of the Virgin Mary and St John, as at Altarnun (Cornwall), Gidleigh (Devon) and Pitcombe (Somerset) (Figure 5). At Trull (Somerset), a nineteenth-century reconstruction of the crucified Christ was inserted into a fifteenth-century Crucifixion window which retained the by-standing Mother of God and favoured disciple because, ‘a small piece of glass shewing a portion of a head crowned with thorns’ confirmed its original presence.Footnote 23 Therefore, this assembly of glass remnants adds representational weight to the iconographic theme, a rare impression of which is given by the whole examples that can still be seen today.

Figure 3. Crucifixion fragments, St Crida’s parish church, Creed, Cornwall. © The author.

Figure 4. Fragment of Christ crucified, St Sidwell and Gulvat’s parish church, Laneast, Cornwall. © The author.

Figure 5. Fragment depicting St John the Evangelist, St Nonna’s parish church, Altarnun, Cornwall. © The author.

Furthermore, it is possible to recover lost Crucifixion scenes from the documentary record. For instance, the scene once decorated the east window of the church at Clyst St George (Devon) alongside the representations of a clerical donor figure, identified in an inscription as the late fourteenth-century rector of the church John Allar, St George holding a shield and the crowned Virgin Mary carrying the Christ child in one arm and a rod in the other.Footnote 24 Having survived restoration work conducted on the chancel in 1854, this glass was unfortunately later destroyed when the church building was bombed during the Second World War.Footnote 25

The frequency of this iconography in stained glass points to a dynamic relationship between windows, altars and the ritual of the mass, illuminated in one respect spatially. The Crucifixion theme was often incorporated into the east window positioned directly behind the high altar in the chancel or above a subsidiary altar in a side chapel, where a significant proportion of the aforementioned fragments and assemblages are found. The east window of the chancel or chapel was typically larger in scale than other windows in the space, as it physically occupied and defined the boundaries of the holy ground surrounding the altar. Its amplified imagery materially framed the altar, thus demonstrating that stained-glass windows were informed by an awareness of spatial setting and could operate as a backdrop to an altar in a similar vein to an altarpiece or reredos.Footnote 26 This has been acknowledged in higher status churches, such as in the case of the great east window at Gloucester Cathedral which was described by Richard Marks as a ‘gigantic triptych’.Footnote 27 Yet, the pervasiveness of Crucifixion glazing in parish churches indicates that this also happened on a smaller scale.

Stained glass visualized the intrinsic meaning of the mass and renewed the events memorialized in the holy sacrament. As a memorial to the scriptural events, the glass underpins the purpose of the mass as an act of remembrance and solemn reflection, as immortalized in Christ’s words repeated by the priest in the canon: ‘As oft as ye shall do these things, ye shall do them in remembrance of me’.Footnote 28 The words and acts of Christ’s final days were continuously renewed in the daily performance of the mass, which encouraged the laity to experience Christ’s Passion and death as a present reality.Footnote 29 For instance, the Lay Folks’ Mass Book was a widely circulated treatise translated around the twelfth century, which guided lay involvement in the mass. During the Gospel reading, it directed the laity to stand in respect and ‘speke þou night, / bot þenk on him þat dere þe boght’.Footnote 30 The presence of the Crucifixion scene strengthened this contemplative experience and created the impression that the event was taking place in real time. It served as a reminder of humanity’s salvation at Calvary and, by association, the perpetual, redemptive power of the mass daily enacted in the church.

Stained-glass windows also interpreted the intimate connection between Christ’s body and the host consecrated by the priest. This is most apparent in the physical proximity of the glass to an altar where the bread was blessed, making the visual link inescapable. As the priest officiated over the ceremony with his back to the congregation, his gaze was directed towards Jesus’ death upon the cross depicted in glass. At the point of elevation enacted directly in front of the window, the host would have been seen on a level visual plane as Christ’s image. The identification was further enhanced pictorially by Christ’s nakedness, with his flesh laid bare before the viewer. The bond between the eucharist and the Crucifixion was stressed in contemporary didactic literature. For example, John Mirk’s fifteenth-century Instructions for Parish Priests clearly relates the crucifix to the Eucharist by advising priests to teach the laity to ‘be-leue on that sacrament; / That þey receyue in forme of bred, / Hyt ys goddess body þat soffered ded / Vp on the holy rode tre’.Footnote 31

Therefore, to summarize, stained-glass windows added weight and significance to the physical setting and performance of the mass. Their vivid imagery underscored both the doctrinal and scriptural meaning of the sacrament by connecting the priest’s acts at the altar with the soteriological power of Christ’s death on the cross. Fragments and textual evidence indicate that the presence of Crucifixion imagery above altars was far more pervasive than the surviving, cohesive programmes of cathedrals or larger churches suggest. The vibrant interaction between art, space and liturgy evident in these greater monuments also took place within the parish church setting.

The Seven Sacraments

Turning to another iconographic theme, several parish churches in south-west England illustrate remnants of the seven sacraments, one of the basic tenets of late medieval Christian faith.Footnote 32 At St Mary’s Bishops Lydeard (Somerset), a collection of fifteenth-century fragments survives in a vestry window. Amongst them, a cleric in red vestments gathers around a font with a lay couple and a headless figure dressed in a blue tunic. An open rubric lies in the midst of the group and traces of a label identify the scene as a baptism (Figure 6). At Burrington (Somerset), pieces of glass in a north aisle window display the blessing at holy orders and the pinnacle of the eucharist ceremony where the priest elevates the host.Footnote 33 The documentary record of lost glass strengthens this pattern. For example, in 1434, Thomas Marshall, vicar of All Saints’ Bristol, paid for two windows to be placed in the south aisle of the church, known as the Rood or Cross aisle, with one depicting the seven sacraments and the other the seven works of mercy.Footnote 34 Elsewhere in the late eighteenth century, the antiquarian Rev. John Collinson visited St Mary’s Meare (Somerset) and commented: ‘The east window of the north aile [sic] contains very fine old painted glass, in which are several historical groups of fine figures; but much obscured by dirt. The principal are the administration of Baptism, the Lord’s Supper, and Extreme Unction.’Footnote 35 Some time after Collinson’s visit, the stained glass was removed and replaced with clear glass because it was believed to have made the interior too dark.Footnote 36

Figure 6. Fragments depicting a baptism, St Mary’s parish church, Bishop’s Lydeard, Somerset. © The author.

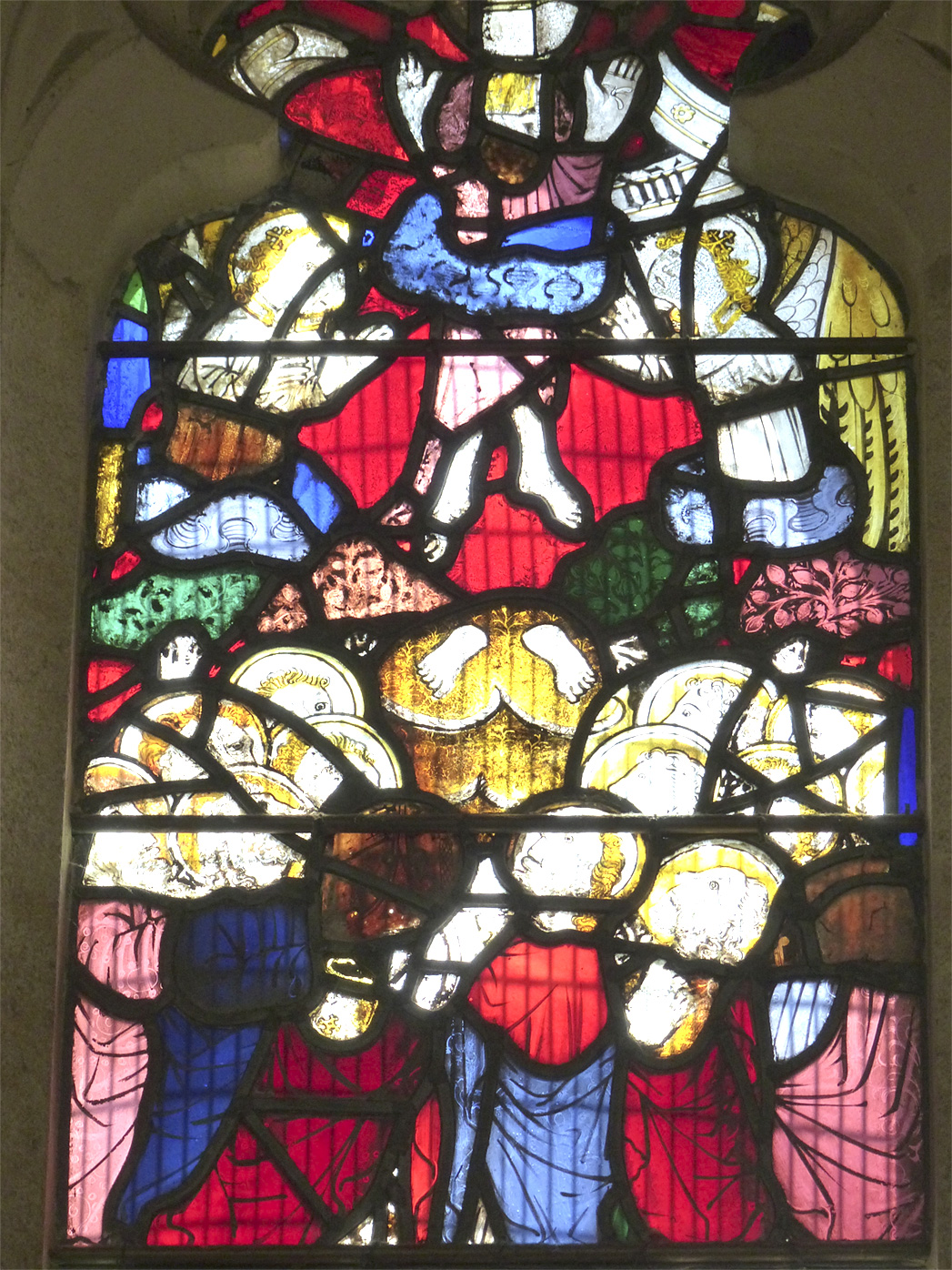

The north aisle’s east window at St Michael’s Doddiscombsleigh (Devon) possesses the most famous and best-preserved example of a seven sacraments window in the country, enabling the researcher to contextualize these fragments and descriptions (Figure 7). The fifteenth-century window displays groups of figures enacting the sacraments and surrounding a modern depiction of Christ seated in majesty, created by the stained-glass workshop Clayton and Bell upon the window’s restoration in the nineteenth century.Footnote 37 The sacraments are connected to Christ by red lines flowing from his five wounds. It is likely that the original image of Christ once resembled the solitary figure that now survives at Cadbury (Devon), where red lines stem from Jesus’ bleeding hands, feet and side (Figure 8). This practice of connecting the sacraments to the figure of Christ can be witnessed in other examples across the south-western counties as the sacraments radiate from Christ showcasing the Passion wounds at Melbury Bubb (Dorset) and Crudwell (Wiltshire). Meanwhile, at Llandyrnog (Denbighshire), the sacraments are linked by red lines to a central crucifix. On occasion, sacrament windows formed part of a larger programme portraying central articles of the late medieval Christian faith, as at All Saints’ Bristol cited above. For example, Thomas Habington, surveying the county of Worcestershire in the seventeenth century, recalled seeing the north aisle of Great Malvern Priory adorned with ‘the Pater Noster, Ave Maria, the Creede, the Commandments, the Masse, the Sacraments issuing out from the wounds of our Saviour; my memory fainteth. But to conclude all in one, there is the whole Christian doctrine’.Footnote 38 Fragmented scenes of three sacraments – ordination, marriage and baptism – now reside in the east window of the church.

Figure 7. Seven sacraments window, St Michael’s parish church, Doddiscombleigh, Devon. © The author.

Figure 8. Christ showcasing his wounds, St Michael’s parish church, Cadbury, Devon. © The author.

Therefore, whilst the sacrament window at Doddiscombsleigh is rare in its condition and completeness, the witness of fragments and lost glass indicates that the subject matter was not uncommon. This elucidates the complex, multifaceted role that stained-glass windows assumed within the parish church setting. For instance, in their full composition, these windows executed a form of doctrinal exegesis, as they interpreted and relayed the sacraments’ value to the viewer. The programmes make a profound theological statement regarding the origins and virtue of the seven sacraments, as derived from Christ’s blood and sacrifice.Footnote 39 As the twelfth-century French theologian and bishop Peter Lombard explained, ‘before the advent of Christ, who brought grace, the sacraments of grace could not be granted, for they have derived their virtue from his death and passion.’Footnote 40 These stained-glass windows thus demonstrate how sophisticated theological ideas filtered down into the popular experience and imagination.

Moreover, these stained-glass assemblages imprinted the church’s interior with the main purpose of the building: the performance of the sacraments. The sacraments held a central place in quotidian religious life. For instance, the laity were expected to attend the eucharist regularly and to partake of holy communion annually, at Easter. They were also expected to make their confession at least once a year during the season of Lent. Meanwhile, baptism, confirmation and marriage were rites of passage or life-cycle events conferred in a church which aimed to integrate an individual into the local Christian community.Footnote 41 This is reflected in the corporate character of these images. For instance, at Doddiscombsleigh, the individual’s act of penance is set within the public space of the church where additional penitents wait in the background.Footnote 42 This sets the individual within a context of regular collective confession. By illustrating central aspects of sacramental performance, the windows prepared the congregation for the rites they regularly witnessed in the church, even visualizing what may not have been entirely visible from their position in the nave. These windows thus grant unique insight into the daily reality of religious practice and communal worship in the parish.

Furthermore, seven sacrament windows also formed a key part of the late medieval church’s pastoral and educational drive, to ensure both the parochial clergy and laity understood and accepted key principles of the orthodox faith. The constitutions of the 1281 Council of Lambeth stipulated that the laity were to be instructed on the seven sacraments regularly in English, alongside other central articles of religious belief and practice, such as the Ten Commandments and the seven works of mercy.Footnote 43 This was subsequently expanded upon in the production of vernacular instructional manuals, such as the 1357 Lay Folk’s Catechism and John Mirk’s Instructions for Parish Priests. Footnote 44 Stained-glass sacrament schemes enshrined catechetical teaching, illustrating important stages in a Christian’s life and spiritual development, thereby reinforcing verbalizations of their significance.

Therefore, an analysis of fragments and descriptions of lost glass indicates that a decorative feature which might have been assumed to be ‘specialized’, confined to a handful of churches, was actually quite commonplace. Illustrations of the seven sacraments were found in numerous parish churches across the South-West of England. Their existence demonstrates the manifold ways in which stained-glass windows communicated. On one level, they interpreted intricate theological beliefs surrounding the origins of the sacraments and delivered a powerful exposition of orthodox teaching. On another level, they reflected the enactment of the sacraments central to the routine religious life of the parish community.

Passion Cycles

Finally, the testimony of surviving fragments, in combination with evidence from the written record, points to the widespread display of narrative Passion cycles. The Passion theme has not loomed large in accounts of English stained glass from this period except in recognition of a few select cases. Today, it finds expression in the well-preserved sequence which adorns the chapel at St Mary Magdalene’s Newark (Nottinghamshire), spans the chancel and Corpus Christi chapel at Fairford, as well as in the remaining episodes that decorate the east window of St Peter Mancroft, including the entombment and resurrection. With regard to the South-West, the fifteenth-century series in the north chapel at St Kew (Cornwall) provides one of the best examples of a Passion window in the country, despite receiving little academic study (Figure 9). The window is divided into four main lights with ten labelled panels depicting individual events from Holy Week. It opens with Christ’s triumphant entry into the city of Jerusalem on Palm Sunday and concludes with the harrowing of hell. However, two panels are missing and two out-of-place Nativity scenes have been inserted at the bottom of the window, which strongly suggests that it originally concluded with scenes of Christ’s resurrection.

Figure 9. Passion window, St James’ parish church, St Kew, Cornwall. © The author.

The coherency and preservation of St Kew’s window may give the impression that such subject matter was rare, but the study of fragments draws the existence of further Passion windows into sharper focus. To take one example, the church of St Michael’s Bampton (Devon) houses an important collection of fifteenth-century stained glass in a south aisle window that on first glance appears to be substantially complete (Figure 10). However, upon closer inspection, the glass is arranged in a kaleidoscopic manner, with pieces of glass cobbled together, proving to be illegible in many places. Only four subjects can be immediately deciphered, including depictions of the Holy Trinity, the Virgin Mary at the Annunciation and St George (originally St Michael) piercing a dragon beneath his feet.Footnote 45 One panel in the upper register presents the twelve apostles huddled around Christ’s disappearing feet and floating figure with two trees in the background, thus representing Christ’s Ascension at the Mount of Olives (Figure 11). It is possible to confirm the originality of this scene when tracing the restoration history of the window.Footnote 46

Figure 10. South aisle window, St Michael’s parish church, Bampton, Devon. © The author.

Figure 11. Panel depicting the Ascension, St Michael’s parish church, Bampton, Devon. © The author.

As a requisite component of the biblical narrative, it is unlikely that the Ascension scene initially stood as an isolated frame. It probably constituted a key part of a wider programme visualizing Christ’s death and resurrection. The details preserved in a combination of fragments support this interpretation, from the repeated figure of Christ, whose head can be seen adorned with a crown of thorns, to instruments of Christ’s torture, such as a ladder and whips. A scroll bearing the words ‘Resurrec[tio] d[o]m̄[ini]’ appears among the shards in the top left panel, and the letters ‘dm̄’ for domini are visible twice more, indicative that labels once accompanied the imagery, guiding the viewer through the narrative. The Passion window at St Kew confirms that this was a feature of such cycles and suggests a structure that the glass may have once followed.

Witness accounts from the nineteenth century identify the remains of further stained-glass Passion programmes in the region that no longer exist today. For example, all that remains in St Michael’s Michaelstow (Cornwall) are traces of coloured glass. However, in the late nineteenth century, Sir John Maclean wrote about the south aisle’s east window:

The former contained remains of painted glass. The subject was probably the last scenes in the life of Our Lord, as the fragments contained several heads with the legend ‘Hic ductus est ante Pilatum.’ In the tracery of this window were two angels bearing shields, with the monograms of Our Lord and the Blessed Virgin. The window has been re-glased, and the ancient glass is gone.Footnote 47

Elsewhere, in the east window of the south aisle at St Gorran’s (Cornwall), the head of a male figure is all that survives in the tracery. However, in his topographical study of Cornwall published in 1820, Charles Gilbert noted: ‘Some remains of stained glass are preserved in one of the windows, in which is represented the fixing of Christ to the cross, and the taking of him down from the same, after being crucified.’Footnote 48 This was corroborated by the writer Joseph Polsue, who saw ‘scanty remains … [of] the principle [sic] scenes at the Crucifixion’ in the window.Footnote 49 In 1824, at Mullion (Cornwall), Fortiscue Hitchins recorded seeing ‘the ascension of Christ, with the apostles gazing on him with apparent wonder and amazement.’Footnote 50 It is also possible that the reclining figure seen in the south chapel window at Creed represents a sleeping disciple in the garden of Gethsemane or a soldier at the tomb (Figure 12). Thus, the combination of these sources indicates that the practice of depicting the climactic events of Christ’s death and resurrection in the medium of stained glass was adopted by many parish churches.

Figure 12. Fragments depicting a sleeping apostle or soldier, St Crida’s parish church, Creed, Cornwall. © The author.

Passion windows contributed to the liturgical rites and devotional practices performed in the parish church in diverse ways. The programme itself takes the viewer on a journey with Christ and His followers through His trial and persecution to the foot of the cross and beyond to His resurrection. This was a journey recreated in celebrated ecclesiastical processions in the church, from bearing palms and flowers around the churchyard and into the church via the west door to echo Christ’s entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday; to ‘creeping to the cross’ in ritualistic mourning on Good Friday.Footnote 51 By the fifteenth century, an expansive discourse had developed in the publication of vernacular literature, such as the widely disseminated Speculum Sacerdotale and John Mirk’s Festial, which vigorously encouraged the laity to visualize and re-enact these pivotal moments in Christian history.Footnote 52 In ritually replicating these events, believers were transported. The laity sought to relive these experiences as Margery Kempe, a fifteenth-century laywoman who recorded her visions and experiences, described that whilst on procession on Maundy Thursday:

Þe sayd creatur went procession with oþer pepil, sche saw in hir sowle owr Lady, Seynt Mary Mawdelyn, & þe xij apostelys. And þan sche be-held with hir gostly eye how owr Lady toke hir leue of hir blysful Son, Crist Ihesu … Sche sey hyr Lord steyn vp in-to Heuyn.Footnote 53

These visions were emotively manifested in the religious imagery of the window, which suggests that glass supported and inspired the devotional purpose of processions.

The glass also intersects with a growing affective trend in late medieval spirituality which focussed on the humanity and suffering of Christ. Parish clergy and their congregations were absorbing textual representations of Christ-the-Man and these fragments indicate how these ideas were given visual expression. These provided images of graphic accounts of the Passion, viscerally exposing the viewer to Jesus’ humiliation, physical pain and anguish. These themes were elaborated upon in sermons, drama and devotional literature which were all designed to ignite the audience’s imagination, as well as their compassion and empathy. As Richard Rolle meditated on Christ’s cries, tears and anguish, he bade ‘Loue, writ with þi blod so ofte Min harde herte tyl it be softe’.Footnote 54 This tradition was also geared towards inspiring the devotee to moral reform, as John Mirk’s Passion sermon exhorted Christian men and women to ‘kneliþ now adon, prayng to Crist þat he forȝeue you þat ȝe haue trespassyd aȝeyns hym by recheles sweryng’.Footnote 55 In this sense, glass harnessed the emotive power of images to move, direct and guide the individual in their daily interactions with the divine.

In summary, fragments and textual sources suggest that the ‘explosion’ of narrative glass cycles observed in the great cathedrals of the Continent in the later medieval period was also experienced in smaller, parochial churches.Footnote 56 The proliferation of Passion windows demonstrate that stained glass both embodied and reinforced the performance of religious activities in the church, such as festive processions. Emotive stained-glass renderings of Christ and His suffering simultaneously cultivated an affective, inward-looking piety in the viewer that was popular in wider devotional traditions.

Conclusion

By drawing fragments and accounts of lost glazing from the periphery into the centre of research, this study has highlighted the potential for such piecemeal evidence to enrich and nuance understanding of the interaction between late medieval worship and the decorative arts within the parish church setting. These sources offer fresh perspectives on the agency of stained glass as a devotional medium, which both augmented collective forms of spirituality and directed individual piety. Here, the glazing of ordinary parish churches acted as a microcosm of the grander sequential programmes of large ecclesiastical sites which pushes the parish church building and its furnishing into sharper focus. In many cases where documentary records from this era no longer exist, as at Laneast and Creed, these remains comprise the only form of evidence that survives testifying to the daily reality of religious experience in a specific place which makes them an invaluable resource for study, in addition to showcasing the richness of material available in the South-West of England. Furthermore, this approach connects with a burgeoning trend in the wider academic field as scholars are increasingly turning towards fragments and decontextualized pieces. The growing study of fragmentology is not only spread across different fields of textual and visual art studies, from literature to music to textiles, but it is also rising with intensity, with a succession of volumes and essays published in the past five years.Footnote 57 The implications of such research leads to a necessary re-evaluation of the canon or established corpus in any specific medium.