People living with severe mental illness (SMI), including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar illness, experience a shorter life expectancy and poorer physical health outcomes than those living without SMI. Premature mortality rates have risen consistently in recent years in people with SMI. Reference Polcwiartek, O’Gallagher, Friedman, Correll, Solmi and Jensen1 This inequality gap widens as the general population benefits from improvements in chronic disease management and better life expectancy. 2

One in four people living with SMI have comorbid physical illness. Physical health multimorbidity is 2.5 times more common in those with SMI than in those without. The burden of physical ill health is especially high for adults aged under 40 years, who are four times more likely to experience physical multimorbidity than those without SMI. Reference Halstead, Cao, Hognason Mohr, Ebdrup, Pillinger and McCutcheon3

Cardiometabolic multimorbidity (the coexistence of two or more of three cardiometabolic disorders – hypertension, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease (CVD)) Reference Di Angelantonio, Kaptoge, Wormser, Willeit, Butterworth and Bansal4 – accounts for a significant proportion of this health inequality and poorer physical health in those living with SMI. People with SMI acquire cardiometabolic risk factors at a younger age when compared with the general population, and the impact of cardiometabolic multimorbidity is even more severe in younger individuals. Evidence suggests that, in the general population, the presence of three cardiometabolic conditions at age 40 years is associated with an estimated 23 years’ reduced life expectancy, Reference Di Angelantonio, Kaptoge, Wormser, Willeit, Butterworth and Bansal4 which would be more pronounced in people with SMI.

The interaction between SMI and cardiometabolic risk factors is multifaceted. Psychotropic medicines – in particular, second-generation antipsychotics – can cause cardiometabolic side-effects to varying degrees. Antipsychotic medications are, however, a key component of the treatment of SMI. Antipsychotic medications improve life expectancy for people with schizophrenia, because those who do not take antipsychotics have a shorter life expectancy than those who do. Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, Doedens, Numminen, van Tricht and de Haan5,Reference Correll, Bitter, Hoti, Mehtala, Wooller and Pungor6 Non-pharmacological factors, such as lifestyle, genetics and reduced access and/or utilisation of healthcare services, contribute to elevated cardiometabolic risk, delayed diagnosis and suboptimal management of cardiometabolic outcomes. Reference Polcwiartek, O’Gallagher, Friedman, Correll, Solmi and Jensen1 It has also been suggested that chronic inflammation is an underlying mechanism for schizophrenia and neuropsychiatric disorders and, thereby, may predispose people with SMI to cardiometabolic disease. Reference Henderson, Vincenzi, Andrea, Ulloa and Copeland7

Preventive cardiology, a comprehensive strategy of risk mitigation to prevent cardiovascular diseases and its clinical sequelae, is an area that is becoming increasingly important for the general population. Reference German, Baum, Ferdinand, Gulati, Polonsky and Toth8 Prevention of cardiometabolic illness in SMI is equally important and must be a priority, because it is a modifiable factor in this early mortality. The complex interplay between the various risk factors and healthcare systems means that not only are those with SMI exposed to higher cardiometabolic risk at a younger age, but that suboptimal management of cardiometabolic risk and treatment of CVD leads to higher cardiovascular disease mortality. Up to 88% of people with SMI who have established dyslipidaemia do not receive lipid-lowering treatment. Reference Nasrallah, Meyer, Goff, McEvoy, Davis and Stroup9 Similarly, 62% of those with hypertension and 30% with diabetes remain untreated for this comorbidity. Reference Polcwiartek, O’Gallagher, Friedman, Correll, Solmi and Jensen1,Reference Nasrallah, Meyer, Goff, McEvoy, Davis and Stroup9

Cardiometabolic risk is managed through risk factor identification and both pharmacological and non-pharmacological prevention strategies. Various international guidelines have been developed for the monitoring, assessment and prevention of cardiovascular risk, but no guidelines exist for the management of cardiometabolic risk in SMI. Reference Polcwiartek, O’Gallagher, Friedman, Correll, Solmi and Jensen1,Reference Visseren, Mach, Smulders, Carballo, Koskinas and Back10,11 Implementation of recommendations is suboptimal, even in the general population, and UK national audit data report that less than half of people at high risk of cardiovascular event are prescribed lipid-lowering therapy as prevention. 11 Currently available clinical prediction models (e.g. QRISK3, Reference Hippisley-Cox, Coupland and Brindle12 SCORE Reference Visseren, Mach, Smulders, Carballo, Koskinas and Back10 ) for the assessment of cardiovascular risk are known to underestimate this in people with SMI, because traditional risk factors only partially account for the excess cardiovascular risk in SMI. Reference Polcwiartek, O’Gallagher, Friedman, Correll, Solmi and Jensen1 At present, although there is no clinically available tool to predict cardiometabolic outcomes in SMI, tools under development such as PRIMROSE and PsyMetRiC could be clinically useful in targeting pharmacological interventions in people with SMI who are exposed to elevated cardiometabolic risk from a young age. Reference Zomer, Osborn, Nazareth, Blackburn, Burton and Hardoon13,Reference Perry, Osimo, Upthegrove, Mallikarjun, Yorke and Stochl14

Non-pharmacological interventions, including diet and lifestyle interventions, play an important role in addressing cardiometabolic risk in people with SMI. Such interventions have been reviewed in systematic and umbrella reviews and demonstrate efficacy in the prevention and management of cardiometabolic risk factors, as well as in improving mental health outcomes such as quality of life. Reference Croatto, Vancampfort, Miola, Olivola, Fiedorowicz and Firth15–Reference Solmi, Basadonne, Bodini, Rosenbaum, Schuch and Smith18 Despite the abundance of evidence for the benefits of non-pharmacological interventions, there exist cohorts of people living with SMI for whom non-pharmacological interventions are not always feasible: for example, those who are acutely unwell may be unable to engage in exercise or healthy eating.

Because the side-effects of antipsychotic medicines are known to elevate cardiometabolic risk predominantly via mechanisms such as hyperlipidaemia, weight gain and hyperglycaemia, choosing agents with lower risk of these side-effects and switching strategies are promoted to mitigate these side-effects. The use of metabolically high-risk agents such as olanzapine and clozapine is discouraged as first-line treatment in first-episode psychosis. Reference Osser, Roudsari and Manschreck19–Reference Galletly, Castle, Dark, Humberstone, Jablensky and Killackey21 Similarly, switching to lower-risk agents has demonstrated improvements in cardiometabolic outcomes. Reference Siskind, Gallagher, Winckel, Hollingworth, Kisely and Firth22 However, it is recognised that for some, including those with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, these interventions are not always feasible and that adjunctive therapies may be necessary. Qualitative research also suggests that people living with SMI indicate a preference for the early use of adjunctive treatments to prevent distressing side-effects such as weight gain. Reference Fitzgerald, Crowley, Ní Dhubhlaing, O’Dwyer and Sahm23

Pharmacological management of risk factors (i.e. using drug therapy) for cardiometabolic disease can potentially improve outcomes and reduce the mortality gap for people living with SMI. Analysis of data from the Danish national registry found that, when individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia were managed with cardioprotective triple therapy (i.e. beta-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, statin and/or antithrombotic) after a myocardial infarction, there was no increase in hazard ratio for all-cause mortality when compared with the general population (hazard ratio 1.05, 95% CI: 0.43–2.52). Reference Kugathasan, Horsdal, Aagaard, Jensen, Laursen and Nielsen24 This demonstrates that healthcare professionals treating people with SMI have an opportunity to improve outcomes by ensuring adequate management of risk factors in the prevention of cardiovascular events.

Systematic reviews have evaluated the evidence for various pharmacological interventions for different cardiometabolic outcomes including weight gain, dyslipidaemia and diabetes. Because cardiometabolic risk factors are likely to coexist, there is a need for an umbrella review to collate the available evidence across all cardiometabolic outcomes. Reference Carolan, Hynes, McWilliams, Ryan, Strawbridge and Keating25,Reference Mezhal, Oulhaj, Abdulle, AlJunaibi, Alnaeemi and Ahmad26 The aim of this umbrella review was to summarise the evidence from systematic reviews for pharmacological interventions to manage cardiometabolic outcomes in people with SMI.

Method

Protocol and registration

Umbrella review methodology was selected for this study. Numerous systematic reviews have been conducted in this area, but there is no recent overview of findings. Building on a review of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions by Vancampfort and colleagues in 2019, this review focuses only on pharmacological interventions and incorporates a number of systematic reviews in this area in recent years. Reference Vancampfort, Firth, Correll, Solmi, Siskind and De Hert16 A protocol was prepared following the Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews 2022 checklist. Reference Gates, Gates, Pieper, Fernandes, Tricco and Moher27 The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Reference Pollock, Becker, Pieper and Hartling28 and several other guidance documents were consulted in the design of this review. Reference Fusar-Poli and Radua29–Reference Aromataris, Fernandez, Godfrey, Holly, Khalil and Tungpunkom31 The protocol was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (no. CRD42023455043).

Study selection criteria

Population, setting and study design

Systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with or without meta-analysis were included. A systematic review was defined as one that includes a specific research question, a reproducible search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, selection methods and a list of included studies. Reference Martinic, Pieper, Glatt and Puljak32 Systematic reviews in adults over 18 years with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar illness or major depressive disorder were included. Reviews carried out only in children and adolescents were excluded. Where reviews included populations with comorbid mental illnesses such as addiction disorders, these reviews were included and comorbid illnesses recorded. Studies carried out in primary, secondary or tertiary care settings were included. All other settings were excluded.

Intervention

Systematic reviews of any pharmacological intervention were included in the review. Systematic reviews of non-pharmacological interventions (e.g. behavioural or lifestyle interventions) only were excluded, as were antipsychotic switching interventions. Antipsychotic switching strategies (i.e. moving from one drug to another) have a role in the management of cardiometabolic outcomes in people with SMI but will not be possible for some patients, e.g. those receiving clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

Where a systematic review included both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, the systematic review was included in the umbrella review but only data from the primary RCTs for pharmacological interventions were extracted. Furthermore, where the systematic review included naturalistic studies, data were extracted only from primary RCTs that fulfilled the umbrella review inclusion criteria.

Comparator

All comparators were included in the review, including placebo, treatment as usual and non-pharmacological interventions.

Outcomes

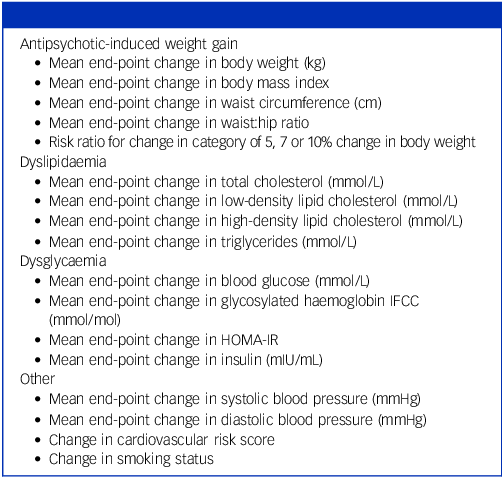

All cardiometabolic outcomes were included; the grouping of primary outcomes is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Outcome measures extracted

IFCC, International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance.

Search strategy

The following databases were searched from inception to 5 June 2024: PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. An information specialist (Killian Walsh, Information Specialist at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland) was consulted on the development of the search strategies and search terms. An example of the search strategy for the PubMed database is outlined as follows:

(((((‘Mental Disorders’[Mesh]) OR ‘Psychotic Disorders’[Mesh]) OR ‘Schizophrenia’[Mesh]) OR (‘severe mental illness’ OR ‘psychosis’ OR ‘mental disease’ OR ‘schizophrenia spectrum disorder’ OR ‘schizophrenia’)) AND (‘body weight gain’ OR obesity OR bmi OR glucose OR dyslipidemia OR cholesterol OR hyperglycemia OR dysglycaemia OR Diabetes OR cardiac OR Cardiovascular OR weight OR ‘metabolic disorder’ OR ‘cardiometabolic syndrome’)) AND (Pharmacological) AND (treatment OR prevention OR management) Filters: Systematic Review.

Conference posters, abstracts, protocols and unfinished studies were excluded.

Screening and data extraction

Search data were managed using COVIDENCE software. Two researchers (A. Carolan and I.J.R.) independently screened the title and abstracts for eligibility and inclusion in the review. Conflicts in decisions were resolved through discussion and agreement and, if necessary, through consultation with the other members of the research team (J.D.S., C.H.-R. and D.K). Data extraction was carried out independently, with the aid of a pre-piloted extraction tool, by two researchers (A. Carolan and A.M.). Reference lists and bibliographies of eligible studies were also screened.

Management of overlap of primary studies

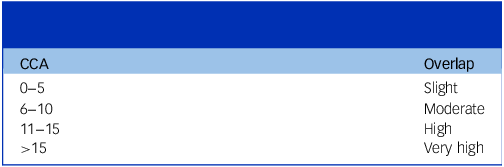

Systematic reviews of the same intervention may include some of the same primary studies. Corrected cover area is a measure of pairwise overlap, allowing identification of reviews with a large overlap in primary publications and the avoidance of attributing too much weight to primary publications included in several systematic reviews. Reference Pollock, Becker, Pieper and Hartling28,Reference Pieper, Antoine, Mathes, Neugebauer and Eikermann33

An overall corrected cover area was calculated using citation matrices and the formula shown in Fig. 1, where N is the total number of primary RCTs including duplicate studies, r is the number of rows or RCTs without duplication and c is the number of columns or systematic reviews.

Fig. 1 Corrected cover area calculation.

Corrected cover area is calculated as a percentage and categorised as slight, moderate, high or very high (see Table 2).

Table 2 Corrected cover area score (CCA, %) and corresponding degree of overlap

A sub-analysis of corrected cover area according to primary outcomes measured was also calculated for each of the outcome groups listed in Table 1. For antipsychotic-induced weight gain (AIWG), we estimated corrected cover area for reviews of the prevention and treatment of AIWG separately.

Due to the wide scope of the review, in which all pharmacological interventions for all cardiometabolic outcomes were included, a narrative synthesis was selected as the method for analysis of the results. It was anticipated that significant overlap across systematic reviews would introduce the potential for bias. The results of a small number of studies that were repeatedly reported across multiple systematic reviews could be inappropriately stressed over those studies that did not overlap across multiple systematic reviews. To our knowledge, methods for the management of significant overlap when performing meta-analysis in umbrella reviews have not yet been established and tested.

Quality assessment

The quality of the included systematic reviews was critically assessed using A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews version 2, a validated instrument version 2 (AMSTAR 2), a 16-domain validated tool with which the user rates adherence to each domain as either ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or, for some domains, ‘Partial yes’. Reference Shea, Reeves, Wells, Thuku, Hamel and Moran34 The overall confidence in the results of the review was rated as either high, where either no or one non-critical weakness was identified; moderate, where there was more than one non-critical weakness; low, where there was one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses; or critically low, if more than one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses was identified. AMSTAR 2 was applied independently by two reviewers (A. Carolan and A.M.). Where discrepancies in judgement were identified, data were checked until agreement was achieved.

Results

A total of 1830 articles were obtained in the search and, following removal of duplicates (n = 107), 1723 abstracts and titles were screened. Thirty-three systematic reviews were eligible for inclusion in the umbrella review. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram illustrates the stages of screening (Fig. 1 of Supplementary Appendix 3 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10476).

The characteristics of the included studies are outlined in Table 1 of Supplementary Appendix 4. A list of excluded studies and the reasons for exclusion can be found in Table 2 of Supplementary Appendix 3. Table 3 of Supplementary Appendix 3 outlines the outcomes measured in the included reviews. AIWG was the most widely studied cardiometabolic outcome, with 21 of the 33 systematic reviews listing change in body weight and/or body mass index (BMI) as primary outcome measures. Of these studies, 20 reviewed the treatment of AIWG and 6 reviewed its prevention. Dyslipidaemia, dysglycaemia and smoking cessation were the next most common outcomes. Five reviews included changes in blood cholesterol (total, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and/or triglycerides) as primary outcome measures. Four reviews included changes in blood glucose and/or HbA1c as primary outcome measures, and five included changes in smoking status as a primary outcome measure.

Corrected cover area and quality assessment

The overall corrected cover area was 6.3%, indicating moderate overlap of primary RCTs across the included systematic reviews.

Slight overlap was noted in reviews in which dyslipidaemia was a primary outcome (5.0%); moderate overlap was noted for reviews in which the primary outcome measure was treatment of AIWG (8.5%) and dysglycaemia outcomes (9.1%); very high overlap was observed for the prevention of AIWG (15.15%), and for reviews in which the primary outcome measure was smoking cessation (25.7%).

An example of the citation matrix for the prevention of AIWG outcome group is illustrated in Table 4 of Supplementary Appendix 3.

The majority of reviews (n = 17) were rated as being of critically low quality using AMSTAR 2. Seven reviews were rated as Similarlylow quality, two as moderate and seven as high quality. The overall AMSTAR 2 score is illustrated in Fig. 2 of Supplementary Appendix 3, and the proportion of adherence across each AMSTAR domain in Fig. 3 of Supplementary Appendix 3.

Interpretation and application of corrected cover area and AMSTAR 2 are described in further detail in Supplementary Appendix 3.

Comparators

The majority of comparators were placebo (n = 17) or placebo/usual care (n = 8). Three reviews included non-pharmacological interventions as comparators, i.e. behavioural therapy (n = 1), cognitive–behavioural therapy (n = 1), supportive group sessions (n = 1) and motivational interviewing (n = 1). Two reviews included other pharmacological interventions as comparators, namely alternative diabetic medication (n = 1) and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) monotherapy (n = 1). The comparator was not reported in three systematic reviews.

Concurrent medication

Concurrent psychotropic medicines were not reported in seven reviews. Antipsychotic medicines were prescribed in the 26 reviews that reported concurrent psychotropic medicines. Table 5 of Supplementary Appendix 3 outlines the reporting of concurrent psychotropic medicines across the systematic reviews. Second-generation antipsychotics were most common (n = 25) and, of these, olanzapine (n = 21, clozapine (n = 21), risperidone (n = 14) and quetiapine (n = 11) were the most frequent. The mood stabilisers lithium (n = 1) and valproate (n = 1) were also prescribed. Because the prescription of other psychotropic medicines was not listed as exclusion criteria across the systematic reviews, antidepressants and other mood-stabilising medicines may have been prescribed but not reported.

Interventions studied

Metformin was the most widely studied pharmacological intervention for cardiometabolic outcomes in people with SMI (n = 18), with topiramate (n = 11) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (n = 9) being the next most commonly studied. Specifically, the GLP-1 agonists liraglutide (n = 5) and exenatide (n = 4) have been reviewed but semaglutide was not. Aripiprazole was included in 7 of the 33 systematic reviews. Table 6 of Supplementary Appendix 3 outlines the pharmacological interventions studied according to World Health Organization classification, and the corresponding number of reviews. Two of the interventions studied have been withdrawn from the market: the European Medicines Agency withdrew sibutramine in 2010 due to cardiovascular risks, and ranitidine in 2019 due to the presence of low levels of an impurity, N-nitrosodimethylamine. Bupropion and naltrexone were the only agents reviewed for both smoking cessation and other cardiometabolic outcomes.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Of the 33 systematic reviews, 28 included a meta-analysis of results. A summary of meta-analysis results by primary outcome measure can be found in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3 Results of anthropometric, glycaemic and lipid outcomes of included reviews

GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; H2RA, histamine-2 receptor antagonist; OLZ + SAM, olanzapine and samidorphan. Bold indicates a statistically significant effect (i.e. P < 0.05). Blank cells denote not reported.

a. Where blood glucose was reported as mg/dL, this was converted to mmol/L using the formula mmol/L = mg/dL × 0.0555. Where HbA1c was reported as National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) (%), this was converted to International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC) (mmol/mol) using the formula IFCC = (10.93 × NGSP) − 23.5.

b. Where total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein and low-density lipoprotein were reported as mg/dL, this was converted to mmol/L using the formula mmol/L = mg/dL/38.67. Where triglyceride was reported as mg/dL, this was converted to mmol/L using the formula mmol/L = mg/dL/88.57.

c. Khaity et al reported lipid outcomes52, but results were pooled from primary randomised controlled trials in which different units of measurement were used. For this reason, these results are not reported in this table.

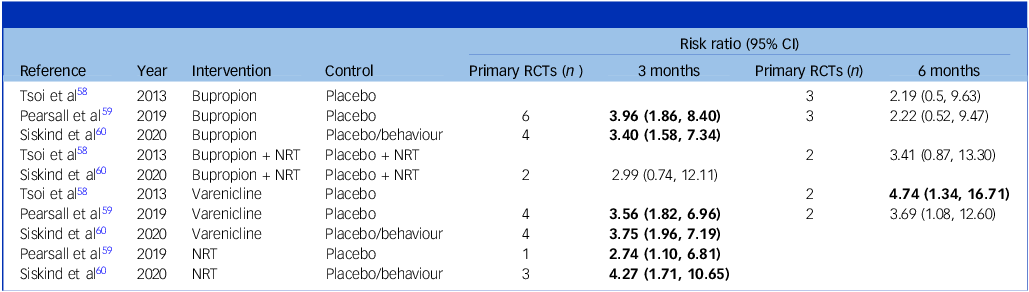

Table 4 Results of meta-analyses in which smoking cessation was a primary outcome measure

RCTs, randomised controlled trials; NRT, nicotine replacement therapy.

Bold indicates a statistically significant effect (i.e. P < 0.05). Blank cells denote not reported.

Dyslipidaemia

Metformin and GLP-1 agonists were the most commonly reviewed interventions for dyslipidaemia; both are unlicensed agents for this indication. Licensed agents such as statins were studied in only two reviews, and just two primary RCTs studied statins in the intervention arm.

Of the five systematic reviews with lipid parameters as primary outcome measures, two provided a meta-analysis of the results. Kanagasundaram et al pooled a meta-analysis of mean difference for end-point change in lipid parameters, showing a statistically significant lowering of both total cholesterol (n = 3, mean difference –0.37 mmol/L, 95% CI: –0.69 mmol/L, –0.06 mmol/L, P = 0.02) and triglycerides (n = 6, mean difference –0.23 mmol/L, 95% CI: –0.37 mmol/L, –0.1 mmol/L, P = 0.0003) for metformin compared with controls. Reference Kanagasundaram, Lee, Prasad, Costa-Dookhan, Hamel and Gordon43 The lipid-lowering therapies omega-3 and statins also demonstrated a statistically significant lowering of total cholesterol (n = 4, mean difference –0.3 mmol/L, 95% CI: –0.4 mmol/L, –0.19 mmol/L, P < 0.00001), but not of other lipid parameters. Reference Kanagasundaram, Lee, Prasad, Costa-Dookhan, Hamel and Gordon43

Four reviews were rated as critically low quality using AMSTAR 2 and one was rated low quality.

Dysglycaemia

Metformin (n = 3), melatonin (n = 1) and GLP-1 agonists (n = 1) were the most commonly reviewed interventions for dysglycaemia. Meta-analysed data were available only for metformin and melatonin, where glucose parameters were a primary outcome measure (Table 3). Taylor et al reported that metformin had a statistically significant effect on fasting glucose (mean difference –0.15, 95% CI: –0.29, –0.01), as did HbA1c (mean difference –0.90, 95% CI: –1.5, –0.30), compared with controls. Reference Taylor, Stubbs, Hewitt, Ajjan, Alderson and Gilbody35 Mishu et al and Zimbron et al reported an improvement in fasting glucose with metformin and melatonin, but mean difference was not statistically significant. Reference Zimbron, Khandaker, Toschi, Jones and Fernandez-Egea36,Reference Mishu, Uphoff, Aslam, Philip, Wright and Tirbhowan37

Weight gain

Metformin has demonstrated efficacy in the prevention of AIWG. Augmentation of metformin with antipsychotic medicines can reduce the extent of weight gain, in the range of 3.12 kg (de Silva et al Reference de Silva, Suraweera, Ratnatunga, Dayabandara, Wanniarachchi and Hanwella41 ) to 5.02 kg (Praharaj et al Reference Praharaj, Jana, Goyal and Sinha42 ), compared with controls. Agarwal et al and Yu et al reviewed metformin for the prevention of AIWG, and in both reviews it was rated as high quality using AMSTAR 2. Reference Yu, Lu, Lai, Hahn, Agarwal and O’Donoghue39,Reference Agarwal, Stogios, Ahsan, Lockwood, Duncan and Takeuchi40 De Silva et al, Praharaj et al and Faulkner et al reviewed the use of metformin for the prevention and treatment of AIWG, in which it was rated as moderate and low quality, respectively. Reference de Silva, Suraweera, Ratnatunga, Dayabandara, Wanniarachchi and Hanwella41,Reference Praharaj, Jana, Goyal and Sinha42,Reference Faulkner, Cohn and Remington61

Smoking cessation

Bupropion, varenicline and nicotine replacement have all demonstrated efficacy in smoking cessation in people with SMI compared with controls. The relative risk of abstinence from smoking at 3 and 6 months is summarised in Table 3. The majority of primary RCTs had a 3-month duration (n = 22). In studies of 6-month duration (n = 12), only varenicline demonstrated a statistically significant benefit in smoking cessation relative to controls in a review by Tsoi et al (n = 2, relative risk 4.74, 95% CI: 1.34,16.71). Reference Tsoi, Porwal and Webster58 The combination of NRT + bupropion did not show a statistically significant difference in smoking cessation relative to NRT + placebo.

Discussion

In this umbrella review we describe the evidence for pharmacological interventions that have been systematically reviewed for cardiometabolic outcomes in people with SMI.

Summary of findings

Metformin has the strongest evidence base for the management of cardiometabolic outcomes in SMI. The largest effect was observed for the prevention of weight gain, but metformin has also demonstrated a clinically significant effect in the treatment of weight gain, dyslipidaemia (total cholesterol and triglycerides) and dysglycaemia. GLP-1 agonists and topiramate showed less consistency. GLP-1 agonists and topiramate are effective at treating weight gain, but the effect across other cardiometabolic parameters is less consistent.

Aripiprazole was included in 7 of the 33 systematic reviews, which is relatively fewer than metformin (n = 18), topiramate (n = 12) and GLP-1 agonists (n = 9). The lowering effect of aripiprazole on cardiometabolic outcomes was also inconsistent. Mizuno and colleagues found that aripiprazole had a statistically significant lowering effect on body weight, fasting glucose, total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol, but not other parameters, Reference Mizuno, Suzuki, Nakagawa, Yoshida, Mimura and Fleischhacker38 whereas Wang and colleagues found a statistically significant lowering of HbA1c but not other parameters. Reference Wang, Wang, Cheng, Fang, Chen and Yu48

Bupropion, varenicline and nicotine replacement have all demonstrated efficacy in smoking cessation in people with SMI compared with controls. Varenicline is effective in sustaining smoking cessation at 6 months.

The dearth of evidence for licensed agents in the management for cardiometabolic outcomes in people with SMI was a key finding in this review. Medicines that are licensed for the management of weight gain and dyslipidaemia have been relatively poorly reviewed in people with SMI. Instead, the evidence has tended to focus on the off-label use of agents such as metformin and melatonin. However, this should not preclude the use of licensed agents in managing cardiometabolic outcomes in people with SMI. Interventions are frequently studied for specific populations if there are particular safety concerns, e.g. potential worsening of mental health symptoms during smoking cessation. Interventions to protect the physical health of the general population should equally be offered to those with SMI, and this review has not found evidence to the contrary.

Few reviews have provided an analysis of the dose-dependent effects of pharmacological interventions. Hegde and colleagues reported their results according to dosing ranges for individual agents. While helpful, the resulting sample sizes are smaller, making it difficult to compare relative efficacy between individual agents. Of note, lower doses of metformin were found to be more effective than higher doses in their review. Reference Hegde, Mishra, Maiti, Mishra, Mohapatra and Srinivasan49

Where reviews provided an analysis of the impact of the stage of illness on the efficacy of pharmacological interventions, there were inconsistent findings. Siskind and colleagues found that the effect of GLP-1 agonists on the management of weight gain was not significantly impacted by psychosis severity. Reference Siskind, Hahn, Correll, Fink-Jensen, Russell and Bak50 Similarly, Yu and colleagues found no significant difference in effect size for metformin in those who were antipsychotic naïve, a proxy for first-episode psychosis. Reference Yu, Lu, Lai, Hahn, Agarwal and O’Donoghue39 However, de Sliva and colleagues found a larger effect size for metformin in those with first-episode psychosis. Reference de Silva, Suraweera, Ratnatunga, Dayabandara, Wanniarachchi and Hanwella41

Clinical implications

Statins are recommended for the general population in the management of hypercholesterolaemia and the prevention of cardiovascular disease. 62 These licensed agents should be offered equally to people with SMI and the general population. Unlicensed agents such as metformin and GLP-1 agonists may also play a role, especially if there is comorbid illness (e.g. type 2 diabetes mellitus) or a concomitant goal to manage AIWG.

Metformin is widely used as a first-line agent in the management and prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the general population, and its use is supported by international guidelines. GLP-1 agonists are not first-line for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus, and most guidelines recommend these as second- or third-line interventions. Reference Moran, Bakhai, Song, Agwu and Guideline63–Reference Qaseem, Obley, Shamliyan, Hicks, Harrod and Crandall65 It is noteworthy that other second- and third-line oral agents for type 2 diabetes mellitus, such as sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and dipeptyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, have not been studied in regard to the management of cardiometabolic outcomes in people with SMI, despite the abundance of evidence for their use in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the general population. SGLT-2 inhibitors, in particular, have proven cardiovascular benefits in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus, Reference Moran, Bakhai, Song, Agwu and Guideline63–Reference Qaseem, Obley, Shamliyan, Hicks, Harrod and Crandall65 but these agents are underutilised in people with SMI and type 2 diabetes mellitus in which the management is generally suboptimal. The strong evidence base for these agents in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the general population probably negates the need for further research in people with SMI, and guidelines for the general population should be applied equally to those with SMI. However, the potential role of these agents in the prevention of cardiometabolic illness in people with SMI is unknown, and further research is warranted.

Future research

The results of this review indicate that pharmacological intervention for the prevention or treatment of weight gain may offer additional protection against other cardiometabolic outcomes. For example, the early use of metformin in the prevention of weight gain may afford additional protection for dyslipidaemia and dysglycaemia. Clusters of cardiometabolic risk factors increase overall cardiometabolic risk, and early intervention to prevent cardiometabolic illness is essential. Reference Zhang, Tang, Shen, Si, Liu and Xu66 Further studies are needed to evaluate the role of metformin in the prevention of cardiometabolic illness, and to determine whether its early use in the prevention of AIWG delays the onset of dyslipidaemia or dysglycaemia and, subsequently, the need for additional medicines such as statins or antidiabetic agents.

It was noted that much of the current evidence for dyslipidaemia is derived from primary RCTs where lipid parameters were secondary outcome measures. High-quality RCTs assessing the efficacy of metformin and GLP-agonists for lipid parameters or composite cardiovascular risk as a primary outcome measure are lacking.

Translating evidence into practice

Delays in translating evidence into practice are well documented and, ultimately, such delays do not serve those living with SMI who are exposed to cardiometabolic risk from a young age. Reference Morris, Wooding and Grant67 Clinicians are faced with the conundrum of how and when to intervene when younger adults present with elevated cardiovascular risk, and current guidelines recommendations lack clarity and specificity for early intervention. The recently published clinical practice guidelines for the early use of metformin in the prevention of AIWG are welcome. Reference Carolan, Hynes-Ryan, Agarwal, Bourke, Cullen and Gaughran68 Facilitating the rapid translation of evidence into practice should be a research priority, to ensure that other cardiometabolic risk factors are proactively managed in people living with SMI.

Medicines optimisation tools could assist clinicians in prescribing appropriate medicines to protect the physical health of people with SMI. An example of one such tool is OPTIMISE, a 62-indicator tool that was developed using Delphi consensus methodology. Reference Carolan, Keating, McWilliams, Hynes, O’Neill and Boland69 OPTIMISE incorporates recommendations for the initiation of pharmacological interventions to improve cardiometabolic outcomes, as well as other physical health outcomes, in people with SMI. Reference Carolan, Keating, McWilliams, Hynes, O’Neill and Boland69 For example, the tool directs the user to consider statin therapy, e.g. atorvastatin 20 mg daily in adults who have a ≥10% 10-year risk of developing CVD. Reference Carolan, Keating, McWilliams, Hynes, O’Neill and Boland69 Similar tools have demonstrated efficacy in improving appropriate prescribing in other populations (e.g. paediatric, frail older adults and those with intellectual disabilities). Reference Cherubini, Guiteras, Denkinger, Beuscart and Onder70–Reference Barry, O’Brien, Moriarty, Cooper, Redmond and Hughes73 Translation of evidence and guideline recommendations into practice could be facilitated by medicines optimisation tools such as OPTIMISE.

At present, there is no clinically available risk prediction tool for the prediction of cardiometabolic outcomes in SMI. Reference Polcwiartek, O’Gallagher, Friedman, Correll, Solmi and Jensen1 Clinical prediction models currently available for the assessment of cardiovascular risk are known to underestimate this in people with SMI, because traditional risk factors only partially account for excess cardiovascular risk in SMI. Reference Polcwiartek, O’Gallagher, Friedman, Correll, Solmi and Jensen1,Reference Perry, Upthegrove, Crawford, Jang, Lau and McGill74 Tools such as the PRIMROSE prediction model that account for additional risk in SMI, including SMI diagnosis and antidepressant and/or antipsychotic medicines, have been shown to better estimate cardiovascular risk in people with SMI, but wider implementation is needed to determine their efficacy. Reference Zomer, Osborn, Nazareth, Blackburn, Burton and Hardoon13 Current guidelines recommend the assessment of cardiovascular risk in the general population over the age of 40 years, but many people with SMI are exposed to elevated risk from a younger age. PsyMetRiC is a risk-prediction model under development that assesses 6-year cardiometabolic risk in people with SMI aged 16–35 years. Reference Perry, Osimo, Upthegrove, Mallikarjun, Yorke and Stochl14 Such a tool could be particularly useful clinically to target interventions for primary prevention in those who are exposed to elevated cardiometabolic risk from a young age.

The appropriate threshold for intervention in those with SMI is not yet defined. Until recently, a QRISK3 score of 10% or higher (i.e. ≥10% 10-year risk of developing CVD) would prompt intervention with lipid-lowering therapy, but more recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines suggest that intervention may be appropriate at lower thresholds for those with SMI for whom traditional risk prediction models underestimate cardiovascular risk. Srihari and colleagues reported 10-year cardiovascular risk estimates in the first year following diagnosis with schizophrenia in a cohort of 76 young adults with first-episode psychosis; Reference Srihari, Phutane, Ozkan, Chwastiak, Ratliff and Woods75 mean age was 22.4 years (s.d. 4.8). In that first year there was a small but significant trend upwards in 10-year cardiovascular risk, although the sample average remained in the low-risk (<10%) category. Reference Srihari, Phutane, Ozkan, Chwastiak, Ratliff and Woods75

Despite recognition of the elevated cardiometabolic risk in those with SMI and the presence of this elevated risk from a younger age, in their current guise, the clinical guidelines do not contain specific recommendations for pharmacological interventions to lower cardiometabolic risk in people with SMI. Given the complex interplay between risk factors and healthcare system barriers, clinicians would benefit from clear recommendations and clinical guidelines to better address cardiometabolic risk in people with SMI.

Outcomes measured

Inconsistency was noted in the primary and secondary outcomes measured across the included systematic reviews, as noted in Table 3 of Supplementary Appendix 3. For example, waist circumference is not consistently measured in studies investigating the management of AIWG. Core outcome sets exist for conditions such as obesity, but a core outcome set for AIWG has not been defined. Waist circumference is a recommend outcome measure for all clinical trials focusing on obesity and it would, therefore, be expected that waist circumference is an outcome measure for all trials focusing on AIWG.

It was noted that reviews of smoking cessation interventions did not assess cardiometabolic outcomes and, conversely, only one review of interventions to improve cardiometabolic outcomes included smoking cessation as an outcome. The benefits of smoking cessation in improving cardiometabolic outcomes are well known: it has the potential to lower overall cardiovascular risk by 50% within the first year of stopping. We included smoking cessation intervention in this review because it is the most effective pharmacological intervention available to improve cardiometabolic outcomes in people with SMI who smoke. Composite cardiometabolic outcomes or overall cardiovascular risk scores were assessed in just two reviews. This may be due to the relatively short follow-up time across primary RCTs (mean), and improvements in composite scores can be delayed. When developing guidelines for the use of statins in the general population, guideline development groups (e.g. NICE, 62 ESC Reference Visseren, Mach, Smulders, Carballo, Koskinas and Back10 ) compare outcome measures such as mortality or cardiovascular events rather than cholesterol levels. This is because ‘what is of most importance to patients is whether a cardiovascular event occurs’. 62 It is therefore difficult to compare unlicensed agents such as metformin/GLP-1 agonists with statins in people with SMI when evidence summaries use different outcome measures.

A core outcome set of cardiometabolic outcome measures would be helpful to standardise the methods available for evaluating the efficacy of pharmacological interventions in people with SMI who are at risk of cardiometabolic illness. Patient and public partners should be involved in the development of a core outcome set, and patient-reported outcome measures should be considered for inclusion given their absence at present.

Limitations

Our results are presented for each cardiometabolic outcome that was studied as a primary outcome measure (Tables 3 and 4). Many of the reviews included other cardiometabolic parameters as secondary outcome measures. For example, when weight gain was a primary outcome measure, lipid and glucose parameters were often measured as secondary outcomes.

Pooled analysis of primary and secondary outcome measures would be valuable in determining the overall effect size of the pharmacological interventions. Vancampfort and colleagues conducted a meta-review, containing 20 reviews of pharmacological interventions, of meta-analyses in pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for physical health outcomes in SMI. Reference Vancampfort, Firth, Correll, Solmi, Siskind and De Hert16 When primary and secondary outcomes are pooled in this manner, metformin has demonstrated a medium-level effect on cardiometabolic parameters (weight, total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, blood glucose, Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance and HbA1c), and other agents such as topiramate demonstrated more consistent clinically significant effects on certain cardiometabolic parameters (i.e. a large effect on LDL cholesterol, medium-level effect on weight and triglycerides).

It is noteworthy that, while metformin has the strongest evidence in the management of cardiometabolic outcomes, many of the studies using metformin for the management of weight gain in SMI were carried out prior to the availability of newer agents such as GLP-1 agonists.

The safety and tolerability of pharmacological interventions were not assessed in this review; we note that 12 of the included reviews did not assess these parameters in their analysis. Where drop-out rates were reported in trials for weight gain, these were similar across the control and intervention groups. Reference Agarwal, Stogios, Ahsan, Lockwood, Duncan and Takeuchi40,Reference de Silva, Suraweera, Ratnatunga, Dayabandara, Wanniarachchi and Hanwella41,Reference Zhuo, Xu, Liu, Li, Zheng and Gao46,Reference Faulkner, Cohn and Remington61

Metformin has a long-established safety profile for type 2 diabetes mellitus and is generally well tolerated, with a low risk of serious side-effects. This review reiterates what is observed in practice, where gastrointestinal upset was the most commonly reported side-effect and that there was no significant difference in tolerability compared with controls. Reference Agarwal, Stogios, Ahsan, Lockwood, Duncan and Takeuchi40,Reference de Silva, Suraweera, Ratnatunga, Dayabandara, Wanniarachchi and Hanwella41

Topiramate can be associated with neuropsychiatric side-effects, and its use in females is restricted. Reference Mahase76 No significant difference in drop-out rates was observed between control and intervention groups in this review. Reference Agarwal, Stogios, Ahsan, Lockwood, Duncan and Takeuchi40,Reference Choi47

Aripiprazole was also well tolerated, with no significant difference observed compared with controls. Reference Choi47,Reference Zheng, Zheng, Li, Tang, Wang and Xiang57 The use of aripiprazole as antipsychotic augmentation is described as antipsychotic polypharmacy. While aripiprazole may be beneficial in the management of cardiometabolic side-effects, there are complications associated with antipsychotic polypharmacy. Of note, the median dose of aripiprazole used in one review was 14 mg/day, 50% of the maximum dose. Reference Zheng, Zheng, Li, Tang, Wang and Xiang57 This may result in high-dose antipsychotic therapy (HDAT) if prescribed alongside therapeutic doses of other antipsychotic medicines. Such strategies require closer physical health monitoring due to the risks associated with HDAT.

While on balance the benefits of treatment probably outweigh the risks, the long-term safety data for GLP-1 agonists are not yet established. In this review, GLP-1 agonists appeared to be well tolerated, with nausea more common in GLP-1 groups than in controls. Reference Siskind, Hahn, Correll, Fink-Jensen, Russell and Bak50 Some concerns have been raised regarding potential neuropsychiatric effects of GLP-1 agonists, and post-marketing surveillance in the coming years should provide clarity on any potential risks.

Statins can increase the risk of dysglycaemia. In the general population, the benefits of treatment in lowering overall cardiovascular risk are considered to outweigh the risk of dysglycaemia, even in those with comorbid diabetes. 62 Although multifactorial, the risk of dyslipidaemia in SMI is in part attributed to the side-effects of psychotropic medicines. It is unclear whether the additive impact of statin- and antipsychotic-induced dysglycaemia suggests that there is a role for other pharmacological interventions to manage dyslipidaemia. The two reviews that included statin therapy found no significant difference in tolerability compared with controls, but the primary RCTs had a short follow-up time of just 12 weeks. Reference Kanagasundaram, Lee, Prasad, Costa-Dookhan, Hamel and Gordon43,Reference Ferrell, Ernst, Ferrell, Jaiswal and Vassar77

Pharmacological interventions to manage cardiac conduction abnormalities were not assessed in this review. People with SMI may be predisposed to cardiac conduction abnormalities. Psychotropic medicines can, to varying degrees, cause electrocardiogram changes and QT-interval prolongation, in particular, is associated with increased risk of mortality. Clozapine-induced tachycardia is managed in practice with rate-limiting agents such as beta-blockers or ivabradine. Lally and colleagues conducted a Cochrane Review of the evidence for pharmacological interventions in clozapine-induced tachycardia. Reference Lally, Docherty and MacCabe78 No primary RCTs met the criteria for inclusion.

Our review population was restricted to people living with SMI. This is because cardiometabolic risk is well recognised as be ingelevated in this population due to multiple factors including lifestyle factors, healthcare system factors and illness, as well as the side-effects of medication. Expanding the population to include those prescribed antipsychotic medicines for other indications (e.g. intellectual disability) may allow a more comprehensive review of the efficacy of pharmacological interventions for antipsychotic-induced cardiometabolic side-effects.

In conclusion, this umbrella review found that pharmacological interventions can improve cardiometabolic outcomes in adults with SMI. Licensed treatments have been reviewed in relatively low numbers. The potential for pharmacological interventions to prevent cardiometabolic illness is an area that warrants further research. This umbrella review should inform clinical guidelines development to incorporate specific recommendations for pharmacological interventions in improving cardiometabolic outcomes in people with SMI who are underserved by current clinical guidelines.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10476

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (A. Carolan) on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

A. Carolan is supported by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland for tuition fees. The authors thank Killian Walsh, Information Specialist at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, for support in developing the search strategy; and Dr Caitriona Cahir, Senior Lecturer at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, for her guidance on quantitative analysis methodology.

Author contributions

A. Carolan, C.R., J.D.S. and D.K. developed the concept for this research. A. Carolan conducted data searches, collection, analysis, verification and interpretation. A. Carolan drafted the manuscript. A. Coady provided an independent second verification of corrected cover area analyses. I.J.R. and A. Coady provided an independent second verification of the systematic literature searches. A.M. provided an independent second verification of the data extraction and AMSTAR quality assessments. C.R., J.D.S., D.K. and B.O. provided a substantive review of the manuscript. A. Carolan, D.K., A.M., A. Coady, I.J.R., C.H.-R., B.O., J.D.S. and C.R. had full access to all data in the study. All authors have read and approved the manuscript and accept final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Health Research Board (grant no. APRO-2023-005). The funder of this research had no role in the study design, data collection, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Declaration of interest

None.

Transparency declaration

The authors affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.