Policy Significance Statement

This paper addresses a key policy gap in agricultural data governance by showing that data ownership is meaningful only when supported by enforceable mechanisms that give farmers real control at the point of data use. By integrating legal, voluntary, and technical pathways, the review highlights the persistent enforcement gap in current EU initiatives and outlines a three-pillar approach: baseline rights for farmers, accessible sovereignty-enabling infrastructure, and participatory governance, to support fair and transparent agricultural data ecosystems.

1. Introduction

The agricultural sector thrives on interconnected data ecosystems, merging sensor networks, Internet of Things (IoT) devices, and external databases to inform decision-making. While farmers have historically depended on experience and intuition, precision agriculture (PA), developed in the 1980s alongside advancements like GPS technology (Zhang, Reference Zhang2015; Pedersen and Lind, Reference Pedersen and Lind2017), has led to a data-driven transformation for farming practices. Farmers typically gather this data through their own equipment or by employing external parties to collect and process their data (Bronson and Knezevic, Reference Bronson and Knezevic2016; Miles, Reference Miles2019). The use of IoT-embedded devices introduces complexities regarding data ownership, as these devices not only collect but also transmit the data to external parties for processing (Gubbi et al., Reference Gubbi, Buyya, Marusic and Palaniswami2013; Wysel et al., Reference Wysel, Baker and Billingsley2021). Additionally, IoT-based traceability systems are increasingly mandated by national and EU regulations for livestock identification, particularly for disease control and subsidy verification (Bandyopadhyay and Sen, Reference Bandyopadhyay and Sen2011). This situation creates an ethical gray area concerning who actually ‘owns’ the data (Sykuta, Reference Sykuta2016; Dagne, Reference Dagne2021): Is it the farmer on whose land and with whose crops/cattle the data was generated, or is it the agriculture technology providers (ATPs) that provide the technology and handle the data? While emerging regulations like the EU Data Act (Regulation (EU) 2023/2854, 2023) aim to empower users by granting them access and usage rights to data from connected products, they notably stop short of defining a legal concept of data “ownership” (Atik, Reference Atik2022, Reference Atik2023). The lack of clear regulations leaves this question unresolved, potentially disadvantaging the farmer (Ellixson and Griffin, Reference Ellixson and Griffin2016).

Although farmers physically host the sensors, the data is frequently processed and stored remotely by ATPs (Hackfort et al., Reference Hackfort, Marquis and Bronson2024). These companies may claim proprietary rights over the data generated, as their devices are essential for data collection and processing (Chichaibelu et al., Reference Chichaibelu, Baumüller and Matschuck2023; Radauer et al., Reference Radauer, Searle and Bader2023). Ruder (Reference Ruder2024) describes this process as an embodiment of surveillance capitalism where farmers unwittingly relinquish data ownership and control via lengthy, unclear End User License Agreements (EULAs) and data licenses. According to Stone (Reference Stone2022), new surveillance technologies are increasingly being developed and deployed to influence decision-making among farmers in the Global South. This dynamic raises concerns about farmers’ control over their own operational data and their capacity to determine who can access, use, or share this information (Atik, Reference Atik2022). Farmers are systematically disempowered within corporate-controlled data ecosystems, where ATP firms leverage proprietary technologies and contractual authority to monetize data while marginalizing farmers (Sykuta, Reference Sykuta2016; Hackfort et al., Reference Hackfort, Marquis and Bronson2024). Furthermore, farmers worry that government data collection, whether for evaluating farm programs or enforcing environmental regulations, may be used in ways that could disadvantage them (Sykuta, Reference Sykuta2016).

Similar concerns apply to data relationships between landowners and tenant farmers, where tenant farmers often lack formal rights over the data they generate (DeLay et al., Reference DeLay, Boehlje and Ferrell2023). Other concerns involve how their data is handled once shared, particularly its potential trading or disclosure to third parties without their knowledge (van der Burg et al., Reference van der Burg, Wiseman and Krkeljas2020). Moreover, farmers feel vulnerable when negotiating contracts with large, often foreign-owned technology providers, whose licensing terms may fall under external jurisdictions (Wiseman et al., Reference Wiseman, Sanderson, Zhang and Jakku2019). Consequently, this ambiguity in data ownership complicates the development of fair and transparent data-sharing agreements and may hinder collaborative efforts among stakeholders, as farmers and ATPs may have conflicting interests in data use (Wiseman et al., Reference Wiseman, Sanderson, Zhang and Jakku2019; Wysel et al., Reference Wysel, Baker and Billingsley2021).

Beyond contractual inequities, scholarly debates further complicate data governance. While governance literature often frames data as an “asset” (Birch et al., Reference Birch, Cochrane and Ward2021), Information Systems (IS) research emphasizes its dynamic role in value creation through sociotechnical practices (Alaimo et al., Reference Alaimo, Kallinikos and Valderrama2020; Costabile and Øvrelid, Reference Costabile and Øvrelid2023; Strnadl, Reference Strnadl2023). As Carballa Smichowski (Reference Carballa Smichowski2018, cited in Hicks, Reference Hicks2022) argues, the value of data lies not in its raw form but emerges from the interplay between datasets and the analytics applied to them. Building on this, critical scholars caution that agricultural data governance is shaped by data productivism, an ideology that data extraction is inherently beneficial, even when it prioritizes corporate and state interests over farmers’ autonomy (Montenegro De Wit and Canfield, Reference Montenegro De Wit and Canfield2024; Hackfort et al. Reference Hackfort, Marquis and Bronson2024). Furthermore, agricultural data governance cannot be divorced from the political economy of agribusinesses, where corporations leverage technological and financial capital to consolidate control over data flows. This mirrors broader neoliberal trends of commodification, a process where communal resources like data are privatized for market gain (Fraser, Reference Fraser2018; Bronson, Reference Bronson2022).

Despite growing attention to agricultural data governance, existing studies tend to examine legal, voluntary, and technical mechanisms in isolation, overlooking how they interact in shaping farmers’ ability to control and share data. This systematic review asks: What mechanisms govern and enforce data ownership and rights sharing in agriculture, and what are their associated challenges and limitations?

Through the analysis of 63 studies, this review makes four interrelated contributions. First, we identify three distinct governance pathways: Legal Enforcement, Voluntary Governance, and Technical Enforcement which together constitute a novel integrative framework. This framework transforms fragmented scholarship into an integrated analytical structure, revealing interdependencies that single-mechanism studies overlook. Second, we demonstrate that “data ownership” is being reframed by “data sovereignty” in policy discourse, requiring fundamental reorientation from static ownership claims to dynamic control mechanisms. Third, we diagnose the “enforcement gap” between nominal legal rights and practical farmer control as the central governance challenge, showing this gap cannot be resolved by any single mechanism alone. Finally, we propose a three-pillar approach: enforceable rights default-allocated to farmers, accessible infrastructure, and participatory governance, as the integrative solution for farmer-centric data ecosystems.

1.1. Agricultural data

Agricultural data embodies a distinctive blend of complexities that sets it apart from data in other sectors. The wide range of data, from small-scale soil measurements to large-scale weather data, and the variety of technologies used to collect it, from simple sensors to satellites with different formats and standards, make ownership even more complex (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Heath, McRobert, Llewellyn, Sanderson, Wiseman and Rainbow2021; Atik, Reference Atik2022, Reference Atik2023). The assortment of tools from basic soil-testing kits to advanced drones and satellite imagery results in a range of data formats, standards, and levels of precision (Ryan, Reference Ryan2019; Steup et al., Reference Steup, Dombrowski and Su2019; Rozenstein et al., Reference Rozenstein, Cohen and Alchanatis2024). Establishing ownership and sharing rights amid this technological diversity requires adaptable and forward-thinking policies that can accommodate the evolution of technologies (Lehmann et al., Reference Lehmann, Reiche and Schiefer2012; Uddin et al., Reference Uddin, Chowdhury and Kabir2022). Furthermore, the interdependent nature of data sources in agriculture further entangles ownership rights (Dagne, Reference Dagne2021; Šestak and Copot, Reference Šestak and Copot2023). For instance, an accurate irrigation prescription model cannot be generated by soil moisture sensor data alone as it requires the integration of weather forecast data, crop growth stage information, and more data sources to be actionable. Safeguarding individual privacy and the commercial sensitivity of farm operations presents another challenge. Data on farming practices may reveal farmers’ personal information or proprietary business insights, such as the profitability of certain crops or the efficiency of specific farming techniques (Carbonell, Reference Carbonell2016; Uddin et al., Reference Uddin, Chowdhury and Kabir2022; Rozenstein et al., Reference Rozenstein, Cohen and Alchanatis2024). Another unique issue to agricultural data is the intrinsic connection between data and land rights (Chandra and Collis, Reference Chandra and Collis2021; Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Rotz, Magnan and Bronson2022). Unlike other sectors where data can often be distinctly separate from physical assets, in agriculture, data is intimately tied to the land (Ibrahim and Truby, Reference Ibrahim and Truby2023; Kotal et al., Reference Kotal, Elluri, Gupta, Mandalapu and Joshi2023), rendering data ownership a reflection of land ownership and use rights (Ryan, Reference Ryan2019). Therefore, Fraser (Reference Fraser2018) connects PA to historical land grabs, linking data extraction to territorial control. Agricultural data cocreation by farmers and ATPs introduces another complexity to data ownership frameworks (Bronson and Knezevic, Reference Bronson and Knezevic2016; Atik, Reference Atik2023). As Bronson (Reference Bronson2022) cautions, the assumption that data is apolitical or neutral obscures the power imbalances and systemic biases inherent in its creation and risks perpetuating inequalities within agricultural systems. As noted by Ingram et al. (Reference Ingram, Maye, Bailye, Barnes, Bear, Bell, Cutress, Davies, de Boon, Dinnie, Gairdner, Hafferty, Holloway, Kindred, Kirby, Leake, Manning, Marchant, Morse and Oxley2022), debates over data ownership and transparency increasingly converge on the question of value distribution, rather than mere control. Echoing Lioutas et al. (Reference Lioutas, Charatsari, La Rocca and De Rosa2019), Rotz et al. (Reference Rotz, Duncan, Small, Botschner, Dara and Mosby2019), Bronson and Knezevic (Reference Bronson and Knezevic2016), and Ingram et al. (Reference Ingram, Maye, Bailye, Barnes, Bear, Bell, Cutress, Davies, de Boon, Dinnie, Gairdner, Hafferty, Holloway, Kindred, Kirby, Leake, Manning, Marchant, Morse and Oxley2022) argue that power asymmetries originate not from who can access the data itself, but rather who can harness its value. Verhulst (Reference Verhulst2023) deepens this critique by identifying agency asymmetries, in which data relationships are structured through imbalances and hierarchies, meaning that one party, often already vulnerable or marginalized, is further disempowered in its ability to act, negotiate, or benefit from the data. Another factor, the replicability of farm data, signifies a unique challenge. Data collected from one context can often be replicated and utilized in another, raising concerns over the control and distribution of this replicated data (Ellixson and Griffin, Reference Ellixson and Griffin2016; Hummel et al., Reference Hummel, Braun, Tretter and Dabrock2021; Radauer et al., Reference Radauer, Searle and Bader2023). These characteristics demand strict measures to ensure that replication does not infringe upon the original ownership terms or dilute the value of the data for the original contributors, as argued by Hackfort et al. (Reference Hackfort, Marquis and Bronson2024).

1.2. Data ownership and governance in agricultural data ecosystems

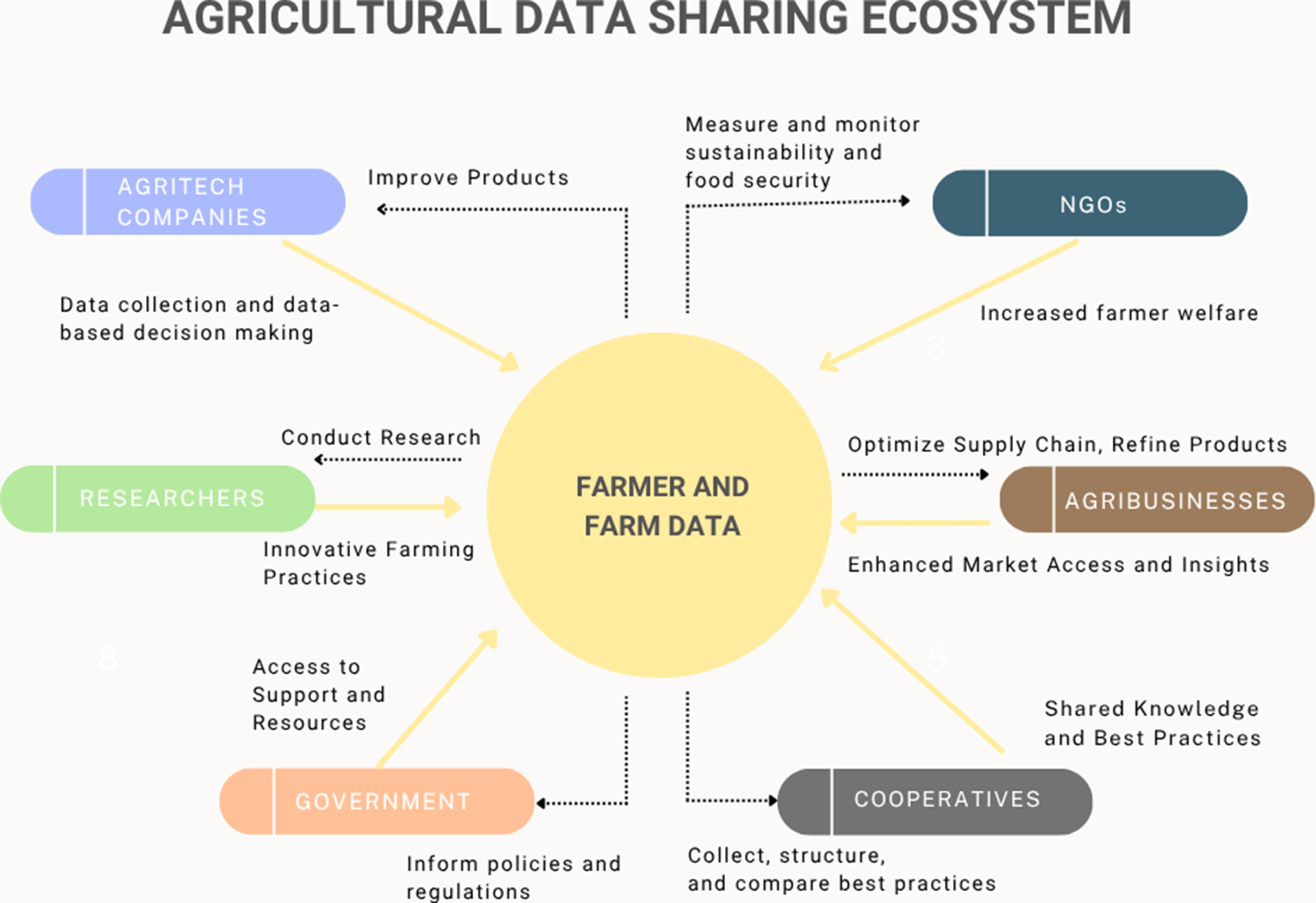

Data derived from agricultural activities holds immense value for various stakeholders, including farmers, ATPs, researchers (Wilgenbusch et al., Reference Wilgenbusch, Pardey and Bergstrom2022; Rozenstein et al., Reference Rozenstein, Cohen and Alchanatis2024), agribusinesses, policymakers, and the broader community, as illustrated in Figure 1 (created by the authors). This wealth of information drives innovation, informs strategic decisions, and shapes policies that benefit the entire agricultural data ecosystem (Ingram et al., Reference Ingram, Maye, Bailye, Barnes, Bear, Bell, Cutress, Davies, de Boon, Dinnie, Gairdner, Hafferty, Holloway, Kindred, Kirby, Leake, Manning, Marchant, Morse and Oxley2022). At the center of this ecosystem, farmers share and receive data on crop and livestock health or weather forecasts to support evidence-based decisions. Additionally, farmers use such data to substantiate claims about their products, such as organic status, animal welfare, carbon footprint, or origin (DeLay et al., Reference DeLay, Boehlje and Ferrell2023; Šestak and Copot, Reference Šestak and Copot2023). Compliance-related traceability data also supports rising regulatory demands for food safety, sustainability, and supply chain transparency (Wysel et al., Reference Wysel, Baker and Billingsley2021; Rozenstein et al., Reference Rozenstein, Cohen and Alchanatis2024). ATPs use this data to improve algorithms and train models, research institutions employ it for scientific advancement (Jouanjean et al., Reference Jouanjean2020), and governments rely on it for policy development and regulation (Ugochukwu and Phillips, Reference Ugochukwu and Phillips2024). Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) use agricultural data to address sustainability, food security, and farmer welfare (Rozenstein et al., Reference Rozenstein, Cohen and Alchanatis2024). Agribusinesses and supply chain actors use it to optimize operations, while farmers’ associations and cooperatives use data to disseminate best practices within their networks (Atik, Reference Atik2022; Luyckx and Reins, Reference Luyckx and Reins2022). Given these diverse stakeholder interests and competing claims over agricultural data, understanding what ‘ownership’ entails becomes essential.

Figure 1. Agricultural data-sharing ecosystem.

As Atik (Reference Atik2022) and Walter (Reference Walter1997) explain and building on Honoré’s (Reference Honoré1988) influential framework (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2013), ownership comprises a bundle of sub-rights rooted in Roman law: usus (the right to use), fructus (the right to benefit from), and abusus (the right to transfer or dispose of). Honoré identified 11 distinct “incidents” of ownership, including possession, management, income, security, and transmissibility, revealing that ownership is not absolute dominion but a flexible framework of separable entitlements that can be distributed across multiple parties. However, legal frameworks vary significantly in their treatment of data as property. Hummel et al. (Reference Hummel, Braun and Dabrock2020) note that many jurisdictions, such as the United States and United Kingdom, do not recognize data as property due to its nonrivalrous and nonexclusive nature. In contrast, European legal frameworks tend to conceptualize data rights as extensions of fundamental human rights, prioritizing individual control and privacy over economic ownership claims. Beyond legal definitions, ownership also engages ethical considerations. Morally, farmers’ rights to benefit from data they generate must be balanced against the societal imperative for equitable access to agricultural innovations (Carbonell, Reference Carbonell2016; Wolfert et al., Reference Wolfert, Ge, Verdouw and Bogaardt2017; Hummel et al., Reference Hummel, Braun and Dabrock2020). This tension between individual data rights and collective benefit shapes ongoing governance debates.

Parallel to these conceptual debates, the practical imperative to enable data sharing has driven the development of new institutional structures. According to Šestak and Copot (Reference Šestak and Copot2023), a data ecosystem is a “socio-technical complex network in which actors interact and collaborate to find, archive, publish, consume, or reuse data, as well as to generate value through these interactions.” Within such ecosystems, a data space is a standardized and governed framework designed to enable data sharing within a data ecosystem. Falcão et al. (Reference Falcão, Matar, Rauch, Elberzhager and Koch2023) expand this notion through the concept of an Agricultural Data Space (ADS), envisioned as a digital ecosystem composed of interconnected agricultural data-sharing platforms. Recognizing the importance of data exchange for economic growth, innovation, and societal welfare, EU proposed the Common European Data Spaces (CEDS) (Bernal, Reference Bernal2024; von Scherenberg et al, Reference von Scherenberg, Hellmeier and Otto2024), which aims to establish a unified European data market, built around 14 sector-specific data spaces, among them the Common European Agricultural Data Space (CEADS) (Atik, Reference Atik2022). Data spaces such as the CEADS are conceptualized as decentralized ecosystems that enable direct data exchange among participants without relying on a central repository, using shared vocabularies to achieve semantic interoperability (Šestak and Copot, Reference Šestak and Copot2023). Another example is the COGNAC Agricultural Data Space (Bacco et al., Reference Bacco, Kocian, Chessa, Crivello and Barsocchi2024), a Fraunhofer initiative, which seeks to improve access to machinery and operational data on digital farms. The EU’s vision for these spaces, particularly in agriculture, places data sovereignty at their core, defined as the power of individuals, organizations, or states to control access to, use of, storage of, and sharing of their data (von Scherenberg et al, Reference von Scherenberg, Hellmeier and Otto2024).

Within such ecosystems and data spaces, digital platforms act as the operational layer that enables these interactions to occur in practice, providing the technical infrastructure through which data is shared, processed, or exchanged (Bernal, Reference Bernal2024). Data marketplaces represent a specific category of multisided platforms designed to facilitate the buying, selling, or licensing of data (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Abbas and Jung2022). In agriculture, several initiatives exemplify this model, including AgDataHub (France), DJustConnect (Belgium), Agrifood Data Space (Finland), JoinData (Netherlands), DKE agrirouter (Germany), and Agrimetrics (UK) (Bacco et al., Reference Bacco, Kocian, Chessa, Crivello and Barsocchi2024). Digital platforms may choose to operate as part of federated data-sharing networks, such as data spaces, which connect independent systems through common governance, interoperability, and trust frameworks. Bernal (Reference Bernal2024) refers to the actors who share data in data marketplaces and platforms as data holders and data users or consumers, highlighting that data sharing predominantly takes place within Business-to-Business (B2B) relationships, as businesses hold both the technological capacity and the societal position to collect, manage, exchange, and derive profit from data produced by diverse actors. This framing exposes a fundamental challenge for smallholder farmers who generate the data but often lack the technological infrastructure and legal ownership recognition necessary to participate as autonomous data holders within such marketplace structures.

Ownership and decision rights vary across centralized, decentralized, and autonomous models of digital platforms. Centralized models concentrate authority with the platform owner, decentralized ones distribute it among the community members, and autonomous models rely on smart contracts for governance (Fadler and Legner, Reference Fadler and Legner2021; Costabile, Reference Costabile2023; Constantiou and Kallinikos, Reference Constantiou and Kallinikos2015). Key roles in these structures include platform owners, complementors, and users, with actors often assuming overlapping responsibilities (Heimburg and Wiesche, Reference Heimburg and Wiesche2022). While these governance configurations shape how authority and control are exercised within platforms, the underlying notion of ownership itself remains complex and contested.

Importantly, sharing farm data for collaborative research or innovation does not require relinquishing ownership; rather, it demands governance mechanisms that preserve the rights of data originators while enabling shared value creation (Idowu et al., Reference Idowu, Wachenheim, Hanson and Sickler2023). However, unequal power relations persist; technology providers can exploit consent mechanisms or impose restrictive terms that limit farmers’ agency. Ryan (Reference Ryan2020) notes that such actors may use coercive strategies, such as revoking data access or imposing penalties, if farmers challenge their terms, underscoring the need for transparency and informed consent (Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Hazrati Fard, Amiri-Zarandi and Dara2022). Desai (Reference Desai2017) further observes that the Internet of Things (IoT) shifts control from users to manufacturers, a trend that recent legislation like the EU Data Act (Regulation (EU), 2023/2854) seeks to counter by granting users specific access and usage rights, though not formal ownership, over data generated by their connected devices (Article 4).

2. Methodology

As an interdisciplinary study at the intersection of agricultural studies, legal scholarship, and information systems, this article applies a systematic review methodology to synthesize and critically assess the fragmented governance mechanisms shaping the ownership of nonpersonal data in agriculture. This review adheres to the guidelines established by Kitchenham and Charters (Reference Kitchenham and Charters2007). According to Kitchenham (Reference Kitchenham2004), a systematic literature review (SLR) aims to summarize existing evidence on a topic and identify research gaps, which was the primary reason for selecting this method. Kitchenham’s three-phase approach: Planning, Conducting, and Reporting, was adapted from the medical field to software engineering. Its rigorous and structured methodology ensures reliability and reproducibility, making it the preferred choice for this study. Planning includes defining the review objective and developing a protocol, which is crucial for minimizing researcher bias. To ensure rigor, we developed a predefined protocol during the planning phase and adhered to it throughout the review process. The protocol encompasses key components such as the research question, search strategy, selection criteria, quality assessment, data extraction, and synthesis.

2.1. Research question

Our process began with the careful formulation of the research question, designed to be both specific and comprehensive, ensuring a focused review of the topic at hand:

The research question (RQ).

RQ: What mechanisms govern and enforce data ownership and rights sharing in agriculture and what are their associated challenges and limitations?

The first objective of this research question is to systematically identify and analyze the mechanisms that define and manage data ownership in the agricultural sector. The second objective is to identify challenges and limitations in the existing governance mechanisms and propose areas for future research.

2.2. Search strategy

This section describes the search strategy employed in the review, including the scope, search method, and search query. The formulation of the research question was followed by the construction of a structured Boolean search query aimed to manually search for journal and conference papers in Scopus and Google Scholar within 2010 and 2024. The search was conducted in June 2024. To concentrate our search specifically on issues of data ownership and rights sharing within the agricultural sector, we formulated our query using the following keywords to encompass the fundamental concepts of ownership, rights, and sharing, the specific domain of application within the agricultural sector and its data-driven practices, as well as the mechanisms that govern and enforce these concepts, as directly specified in our research question.

(“data ownership” OR “ownership of agricultural data” OR “data rights” OR “property rights” OR “data sharing” OR “rights sharing”) AND (“agriculture” OR “agricultural sector” OR “farming” OR “precision agriculture” OR “smart farming” OR “digital agriculture” OR “agri-tech” OR “agriculture technology providers” OR “ATP” OR “farm technology” OR “sensor data” OR “IoT in agriculture” OR “govern” OR “enforce”).

The structured query retrieved articles hosted by major academic publishers, including IEEE, ACM, SpringerLink, ScienceDirect, SAGE Publications, Wiley, Taylor & Francis, and others.

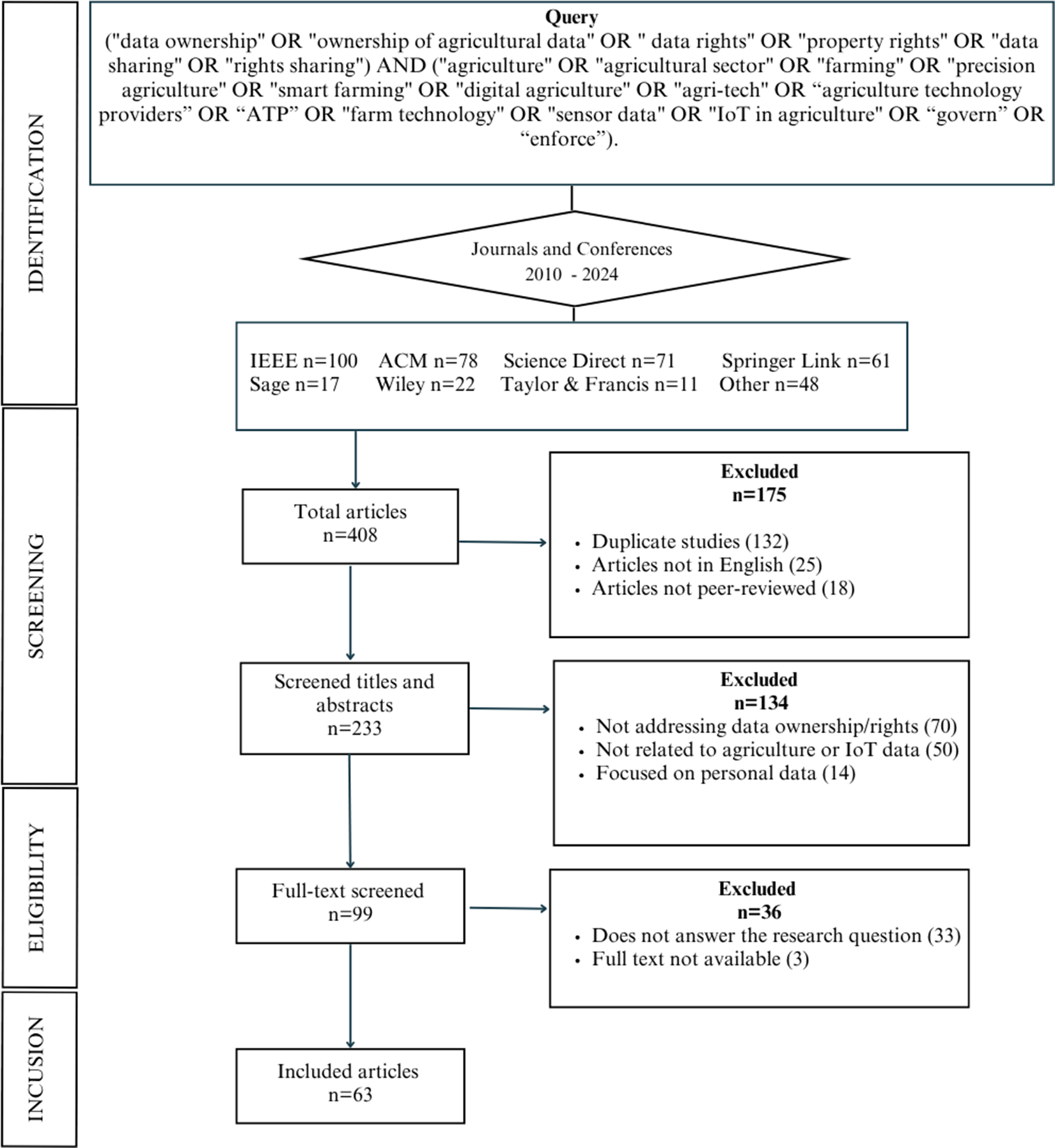

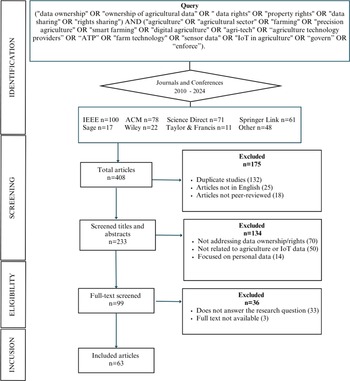

2.3. Selection criteria

Our systematic review followed strict inclusion and exclusion criteria established during the protocol definition to minimize bias, in accordance with the guidelines of Kitchenham and Charters (Reference Kitchenham and Charters2007). The main stages of the literature search are shown in Figure 2, following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Haddaway et al., Reference Haddaway, Page, Pritchard and McGuinness2022). Our inclusion criteria were: peer-reviewed journal and conference papers (2010–2024) addressing the establishment, enforcement, or governance of data ownership/rights sharing in agricultural contexts. The initial search returned 408 records. After removing duplicate entries, non-English articles, and articles that were not peer-reviewed, 233 titles and abstracts were screened. At this stage, studies were excluded if they did not address data ownership or data rights, were unrelated to agriculture or IoT data, or focused exclusively on personal data. This resulted in 99 articles selected for full-text review, where 36 papers were excluded for mentioning ownership superficially without explaining how it was defined, contested, or enforced, hence not answering our research question. The references chapter denotes the 63 reviewed papers (57 journal papers and 6 conference papers) with an asterisk (*). The excluded papers were recorded on an Excel file in case of a need for iteration.

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the selection process of studies.

2.4. Quality assessment

To ensure the relevance of selected studies, we applied a single quality criterion: whether the paper explored how data ownership is governed in agriculture or how data rights are enforced. Three of the coauthors independently scored studies as “Yes” (meets criteria) or “No” (excluded). Disagreements were resolved by the fourth author. Sixty-three papers from the selection phase successfully met the quality assessment criteria, demonstrating their relevance and suitability for inclusion in the study.

2.5. Data extraction and synthesis

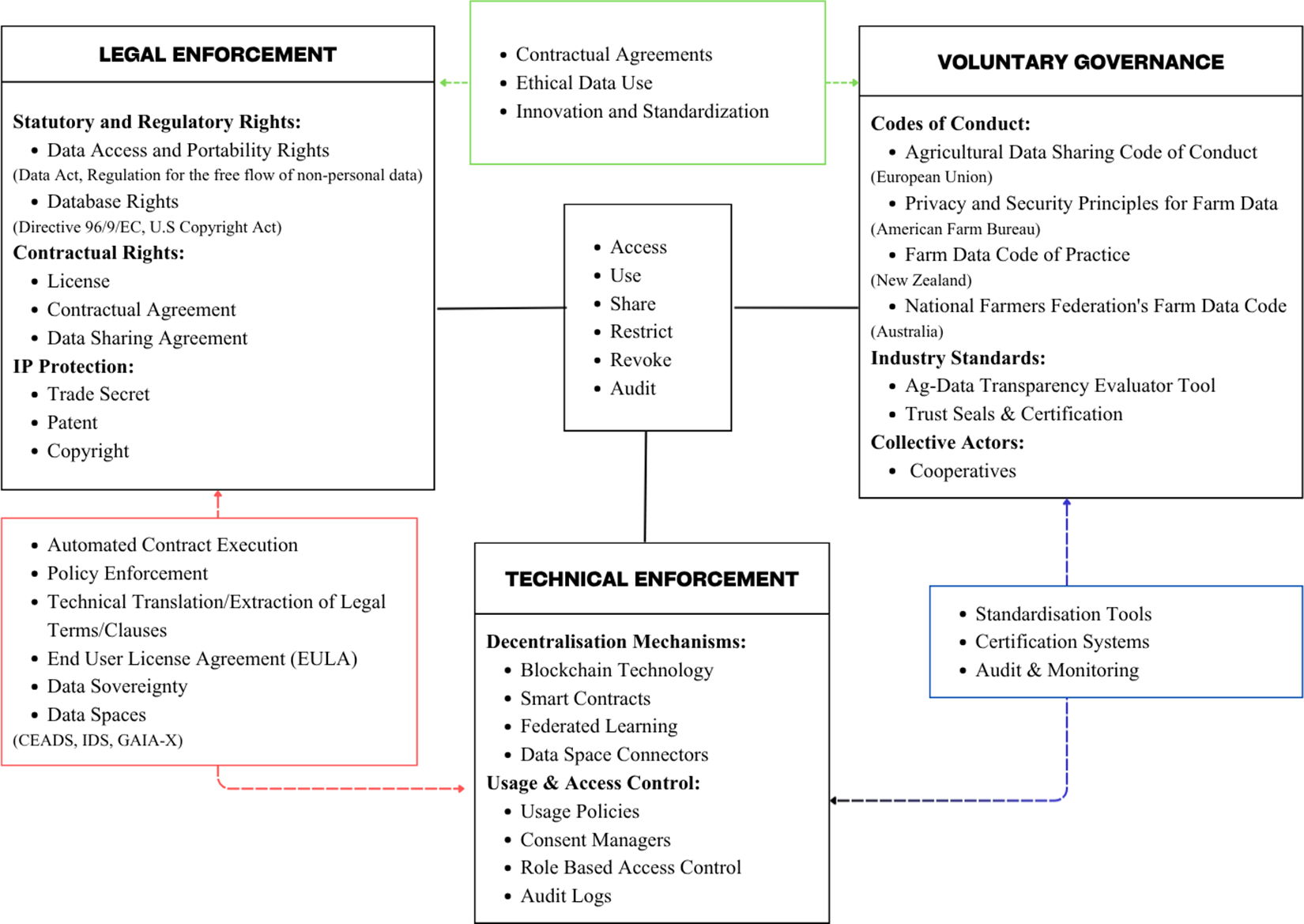

The data-extraction process systematically captured information from 63 selected studies to enable a rigorous thematic analysis. In agricultural data governance, key terms such as “ownership,” “access,” “rights,” “sharing,” and “govern” appear inconsistently across literature, making manual screening and Excel-based thematic extraction more reliable for capturing conceptual relevance. Hence, a structured Excel form was used to record key details, including authorship, publication year, study focus, stakeholders involved, governance mechanisms, and key findings relevant to the research question. The synthesis followed a thematic analysis approach (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) to identify recurring patterns and gaps concerning agricultural data ownership. The first author conducted a detailed reading of all studies to gain familiarity and assign initial descriptive codes related to governance mechanisms, enforcement strategies, and stakeholder power dynamics. These codes were subsequently grouped into broader patterns through collaborative discussions among coauthors, giving rise to candidate themes such as “Legal Enforcement” and “Technical Enforcement.” The themes were then reviewed and refined to ensure they accurately addressed the research question, resulting in the emergence of three core categories of governance mechanisms: Legal Enforcement, Voluntary Governance, and Technical Enforcement. The themes’ interrelations were mapped to form the conceptual framework illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Conceptual framework of ownership governance mechanisms in agriculture.

3. Findings

This section synthesizes the findings of our systematic review through the conceptual framework (Figure 3) that categorizes the governance of agricultural data ownership into three interconnected pathways: Legal Enforcement, Voluntary Governance, and Technical Enforcement. The framework illustrates that these are not isolated categories but overlapping systems that collectively define, allocate, and enforce the bundle of rights associated with data ownership. Each subsequent subsection is dedicated to one of these pathways, where we detail the specific mechanisms, from statutory laws and contractual agreements to codes of conduct, blockchain-based architectures, and emerging data spaces that operationalize ownership claims.

3.1. Legal enforcement

As Chichaibelu et al. (Reference Chichaibelu, Baumüller and Matschuck2023) observe, protecting farm data is inherently complex due to its entanglement with data protection, contract, competition, and intellectual property laws.

Within this legal landscape, the database directive (Directive 96/9/EC, 1996) addresses the legal protection of databases in the EU, potentially relevant for agricultural databases. For farmers and ATPs, this means there is a legal framework that recognizes their work in creating valuable databases. It ensures that if they spend time and resources collecting and organizing data, they have certain rights over the use and distribution of that information (Schneider, Reference Schneider1998; van der Burg et al., Reference van der Burg, Wiseman and Krkeljas2020). Conversely, in the United States, database contents receive intellectual property protection only when their creation demonstrates “a minimal degree of creativity.” Consequently, purely factual content remains unprotected despite potentially substantial investments in data collection (Harison, Reference Harison2010). The U.S. Copyright Act protects database contents as intellectual property by classifying them as compilations. Protection applies when data is selected, coordinated, and arranged in an original manner.

Legislations derived from the European Strategy for Data (European Commission, 2020), such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Regulation (EU) 2016//679, 2016), Data Governance Act (DGA) (Regulation (EU) 2022/868, 2022), and the Data Act (DA) (Regulation (EU) 2023/2854, 2023), collectively regulate the data protection of various actors (von Scherenberg et al., Reference von Scherenberg, Hellmeier and Otto2024).

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into force in 2016 across Europe and since then it has significantly shaped the global landscape of privacy and data protection legislation (van der Burg et al., Reference van der Burg, Wiseman and Krkeljas2020). It highlights the prioritization of security, privacy, and the safeguarding of personal data processed within the EU (Atik, Reference Atik2023; Ibrahim and Truby, Reference Ibrahim and Truby2023). Data like soil nutrient levels, weather patterns, or crop yield metrics are nonpersonal (Chichaibelu et al., Reference Chichaibelu, Baumüller and Matschuck2023) and fall outside privacy regulations like GDPR. GPS data (e.g., tractor routes, field boundaries) can be personal data if they directly or indirectly identify a natural person (European Union, 2016; Wiseman et al., Reference Wiseman, Sanderson, Zhang and Jakku2019). Likewise, data from IoT devices (e.g., irrigation schedules, livestock health monitors) is personal only if tied to identified or identifiable individuals (Regan, Reference Regan2019; Rozenstein et al., Reference Rozenstein, Cohen and Alchanatis2024). GDPR is widely considered the leading standard for data privacy (Kotal et al., Reference Kotal, Elluri, Gupta, Mandalapu and Joshi2023). Its influence is apparent globally, with similar legislation emerging in other regions, for instance, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), 2018.

The EU regulation that facilitates the flow of nonpersonal data and is particularly pertinent to agricultural data is the EU Regulation on the Free Flow of Non-Personal Data (Regulation (EU) 2018/1807, 2018). This regulation distinctly classifies data from machinery as nonpersonal, underlining the clear distinction between personal and nonpersonal data in the sector of agriculture (Wiseman et al., Reference Wiseman, Sanderson, Zhang and Jakku2019) and suggests creating voluntary initiatives, such as codes of conduct or practices on agricultural data sharing by contractual agreement to enable farmers to change service providers easily, akin to the data mobility rights provided in GDPR. Agricultural data is positioned as a critical driver of innovation and economic growth within the agriculture sector (Chandra and Collis, Reference Chandra and Collis2021; Wysel et al., Reference Wysel, Baker and Billingsley2021) and by banning data localization, the practice of mandating data storage within specific jurisdiction, the regulation seeks to dismantle barriers to cross-border data sharing, fostering a unified digital market (van der Burg et al., Reference van der Burg, Wiseman and Krkeljas2020).

Although the Data Governance Act and other EU agricultural policies are intended to enhance trust in data intermediaries and facilitate data-sharing, Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Regan and van der Burg2023) criticize the Act for framing governance through overly abstract personal/nonpersonal distinctions that provide “little to no provision” for the reality that datasets shift in status depending on their use, context, and the actors involved.

To address more concrete issues of access and fairness, the EU Data Act introduces key provisions designed to ensure equitable data-sharing practices, particularly relevant for sectors like agriculture. It addresses contractual fairness by protecting smaller entities from unfair terms in data-sharing agreements with larger ATPs (Atik, Reference Atik2022, Reference Atik2023). The EU Data Act does not explicitly define “data ownership” or assign legal ownership of data. Instead, it focuses on usage and access rights by granting (“users”) rights to access and share data from connected products they own, rent, or lease, like tractors, as well as sensors and other products that generate data (Art. 2(5), EU Data Act). Furthermore, the Act covers the data from “related services” such as essential software for the product’s function and related services tied to them (Art. 2(6), EU Data Act). It excludes data from digital farm services (e.g., crop analytics apps) that are not directly linked to machinery (Atik, Reference Atik2022). Atik (Reference Atik2022) argues that while the Data Act provides a foundational framework, sector-specific regulations are necessary to address agricultural data-governance challenges, such as interoperability standards, historical data transfers, and access to nonmachinery datasets.

The Data Act’s provisions for access and use must be understood as part of the broader regulatory architecture designed to enable the European Strategy for Data (European Commission, 2020), von Scherenberg et al., Reference von Scherenberg, Hellmeier and Otto2024). This strategy aims to create sector-specific Common European Data Spaces, including for agriculture (Atik, Reference Atik2022). The Common European Agricultural Data Space (CEADS), currently in development, is the sector-specific instantiation of this vision (European Commission, 2020). It seeks to move beyond the legislative foundation to create a functioning marketplace and ecosystem for sharing data, relying on the technical and voluntary mechanisms to protect data rights (European Commission, 2020; Atik, Reference Atik2022; Falcão et al., Reference Falcão, Matar, Rauch, Elberzhager and Koch2023; Hellmeier et al., Reference Hellmeier, Pampus, Qarawlus and Howar2023).

This ambiguity around ownership is not unique to the Data Act. Farm data is also not protected under traditional intellectual property regimes such as U.S. patent or copyright law, which apply to inventions and creative works, respectively (Idowu et al., Reference Idowu, Wachenheim, Hanson and Sickler2023). Europe takes a similar starting point, as raw facts generated on the farm are not property protected by patent or copyright (Directive 96/9/EC). Instead, legal protections rely on a layered mix of database rights (Directive 96/9/EC), trade secrets (Directive, 2016/943), and emerging data access rules (e.g., Data Act Articles 4–5 and 43), alongside voluntary codes of conduct, which together give farmers and ATPs a different legal toolkit.

Hence, trade secrets emerge as a valuable alternative for securing farm data (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Regan and van der Burg2023; Ibrahim and Truby, Reference Ibrahim and Truby2023). Trade secrets, a globally recognized form of intellectual property protection, are commonly used to safeguard data as a crucial form of Intellectual Property (IP) (Radauer et al., Reference Radauer, Searle and Bader2023). Trade secret protection can be applied to closed data depending on factors like practicability or enforceability. Trade secrets offer a potential solution for farmers seeking to maintain exclusivity over their farm data, provided they actively safeguard it (Radauer et al., Reference Radauer, Searle and Bader2023). If farmers want to assert their exclusive rights to use data through trade secrets, they must argue that farm data is a form of intellectual property that gives a competitive edge to the farm business that possesses it (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Regan and van der Burg2023). Digital data are intangible, meaning the copies of original data are just as original, also irreplaceable, meaning if destroyed cannot be recovered (Hummel et al., Reference Hummel, Braun and Dabrock2020), and there is still a debate whether farm data is excludable (collected using proprietary methods by an entity that prohibits its sharing) or nonexcludable (shared with others) (Ugochukwu and Phillips, Reference Ugochukwu and Phillips2024). Destroying digital data completely is challenging if not impossible as it typically exists in multiple copies and locations. To claim ownership of farm data, it is necessary to demonstrate that it is appropriately classified as a trade secret (Carbonell, Reference Carbonell2016). When farmers hire ATPs for collecting their data, a new digital copy of the data is created so the farmer loses ownership of the original data, making the data nonexclusive (Atik, Reference Atik2023; Ugochukwu and Phillips, Reference Ugochukwu and Phillips2024). Nonetheless, a trade secret includes information that remains undisclosed to the public, holds commercial value, and is secretly maintained in confidence by its proprietor (Directive- 2016/943). When data is closely guarded, the opportunities for innovation, collaboration, and improvement across the agricultural sector are limited (Šestak and Copot, Reference Šestak and Copot2023).

The governance gaps and power asymmetries created by underdeveloped regulation are starkly visible in regions where foundational data-protection frameworks for agriculture are absent. For instance, in Africa, Chichaibelu et al. (Reference Chichaibelu, Baumüller and Matschuck2023) highlight that regulators are yet to address the protection of agricultural data, and existing personal data laws contain no specific provisions for farm data. In the absence of regulation, data sharing is governed by licensing contracts, but no legal frameworks exist to ensure the fairness of their terms. In 2010, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) established the first regional legal instrument for data protection in Africa, with the African Union following four years later through its Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection. Both aim to harmonize personal data laws across the continent to address cross-border data flows and regulatory fragmentation. However, as Dagne (Reference Dagne2021) points out, farmers’ access to their own data can be constrained by two key factors: de facto control over digital infrastructure and the exclusivity of data ownership rights. Ownership of the hardware and platforms used to collect and store data often determines who can access it, reinforcing asymmetries in power and control.

These structural imbalances are worsened by the digital divide and legal inequality between farmers and agri-tech providers, particularly when negotiating data-sharing agreements (Ryan, Reference Ryan2019; Uddin et al., Reference Uddin, Chowdhury and Kabir2022). Farmers often find themselves at a disadvantage in discussions with large tech companies, leading to hesitancy in sharing data due to unclear benefits and perceived risks via EULAs and data sharing agreements (Sykuta, Reference Sykuta2016; Wiseman et al., Reference Wiseman, Sanderson, Zhang and Jakku2019; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Heath, McRobert, Llewellyn, Sanderson, Wiseman and Rainbow2021). Kaur and Dara (Reference Kaur and Dara2023) examine how service-provider agreements deal with ownership of farm data, finding that only 19 of 141 agreements use the term “ownership” when referring to who owns the data once it has been collected or transferred, whereas 122 agreements reference “access” and 103 reference “control,” with sample policy excerpts illustrating the often-limited scope of farmers’ ownership rights. The study further highlights that these agreements are typically long, legally dense, and hard to comprehend: 95% of them fall into the “difficult-to-read” category, and nearly 75% require university-level education to understand their content.

On the other hand, Fraser (Reference Fraser2018) argues that even the availability of “open” data does not inherently empower farmers. Access alone does not guarantee the ability to derive meaningful value, as transforming raw data points into actionable insights requires analytical expertise, computational resources that many farmers, particularly in resource-constrained settings, may lack.

In essence, while the protection of data is crucial for maintaining competitive advantages and ensuring privacy, finding a balance that also encourages the sharing of data can lead to broader gains for the entire agricultural community (Carbonell, Reference Carbonell2016; Sykuta, Reference Sykuta2016). The draft ownership-and-sharing rules could stop farmers from sharing their farm data to alternative service providers, which may in turn reduce the quality of services those rival ATPs can offer (Sykuta, Reference Sykuta2016).

Atik (Reference Atik2022) highlights how traditional ownership frameworks struggle with the technical and economic realities of agricultural data, such as its replicability and collaborative generation. The author cites Härtel’s proposal for data sovereignty as an alternative paradigm, which shifts focus from static legal entitlements to dynamic governance mechanisms that prioritize control and ethical stewardship (Härtel, Reference Härtel2020). According to von Scherenberg et al. (Reference von Scherenberg, Hellmeier and Otto2024)), data sovereignty is not a static property or a one-off “ownership” label; it is the sustained capacity of the data provider to set, monitor and, if necessary, revoke the conditions under which others may exploit the data, backed by trustworthy infrastructure and enforceable contracts (Jarke et al., Reference Jarke, Otto and Ram2019). This aligns with Zhang et al.’s (Reference Zhang, Heath, McRobert, Llewellyn, Sanderson, Wiseman and Rainbow2021) argument that agricultural data governance best practices emphasize principles like data sovereignty, stewardship, and custodianship to balance stakeholder rights.

Furthermore, the inability of contracts to anticipate every possible future use, condition, or context of data exchange creates a gap in governance, a space where actual control must be exercised beyond what is written. As Chaddad and Iliopoulos (Reference Chaddad and Iliopoulos2012) explain: residual control rights refer to the authority to make decisions over an asset in situations not covered by law or contract, and because all contracts are incomplete, these rights ultimately define who truly “owns” the “asset” (see also Grossman and Hart, Reference Grossman and Hart1986). In the context of agricultural data, this means that even if a farmer is nominally recognized as the data “owner,” that status is hollow unless accompanied by enforceable mechanisms, technical or institutional, that enable them to assert and execute those residual control rights in real time.

3.2. Voluntary governance

Considering that the GDPR protects personal data privacy, and related regulations promote codes of conduct and data-sharing agreements, jurisdictions including the European Union, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand have developed their own sets of guidelines for agricultural data sharing. The primary aim of these guidelines is to foster a trustworthy relationship between farmers and agricultural businesses through the formulation of contractual agreements. Participation in these initiatives is voluntary, yet they serve to encourage the ethical and clear exchange of information.

In response to the need for clear data ownership and sharing rules, the American Farm Bureau Federation introduced the Privacy and Security Principles for Farm Data (PSPFD) in 2014 (Fraser, Reference Fraser2018), a pivotal move in the United States (Ibrahim and Truby, Reference Ibrahim and Truby2023; Kaur and Dara, Reference Kaur and Dara2023). Under the U.S. Farm Bureau’s Privacy and Security Principles for Farm Data, farmers (i) retain ownership of on-farm data and must negotiate any sharing agreement, (ii) grant access only by explicit contract, and (iii) have the right to clear notice of collection and downstream uses (PSPFD, 2014; Amiri-Zarandi et al., Reference Amiri-Zarandi, Dara, Duncan and Fraser2022).

However, Sykuta (Reference Sykuta2016) argues that it is unclear if following these principles will protect the value of farmers’ data or prevent service providers from turning their data into monopolies. The principles of the American Farm Bureau for Farm Data say farmers own the information that comes straight from their farms, but they do not own new information that ATPs create from it, such as recommendations and predictions (Sykuta, Reference Sykuta2016).

Based on these principles, an Ag-data transparency evaluator tool has been developed (Steup et al., Reference Steup, Dombrowski and Su2019). ATPs will assess themselves and their work with data, to check if their practices are according to the principles of PSPFD. If they are successful, they will receive a seal, and their results will be published on websites for farmers to see (Wiseman et al., Reference Wiseman, Sanderson, Zhang and Jakku2019). This seal provides trust between farmers and ATP companies (Desai, Reference Desai2017; Sanderson et al., Reference Sanderson, Wiseman and Poncini2018). A similar practice is done according to New Zealand’s Farm Data Code of Practice, which launched in 2014 (Sanderson et al., Reference Sanderson, Wiseman and Poncini2018).

In the following years, the European Union unveiled its own EU Code of conduct on agricultural data sharing by contractual agreement in 2018 (EU, 2019; Atik, Reference Atik2022; Kotal et al., Reference Kotal, Elluri, Gupta, Mandalapu and Joshi2023). The Code was developed collaboratively by farmers’ cooperatives in partnership with COPA (Committee of Professional Agricultural Organisations), which represents farmers, and COGECA (General Confederation of Agricultural Cooperatives), which represents agricultural cooperatives (van der Burg et al. Reference van der Burg, Wiseman and Krkeljas2020). This code acts as a structure to encourage good data handling, enable cooperation, and foster innovation in agriculture, all while safeguarding the rights and interests of farmers (EU, 2019). As per the EU code, data produced by a farmer from agricultural activities, referred to as the “data originator,” should be attributed to and owned by the farmer (Wiseman et al., Reference Wiseman, Sanderson, Zhang and Jakku2019). Conversely, data from machines and sensitive information are considered the property of the machine manufacturer. According to Gardezi et al. (Reference Gardezi, Joshi, Rizzo, Ryan, Prutzer, Brugler and Dadkhah2024), the EU Code of Conduct helps protect farmers from opaque, non-sovereign EULAs by promoting clearer and more controllable data-sharing terms. However, there is a lack of clarity in the code as it assigns different responsibilities to parties based on their roles (Sanderson et al., Reference Sanderson, Wiseman and Poncini2018). This situation poses a difficulty because all involved parties need to comprehend their responsibilities prior to applying the code.

Compared to the U.S. Privacy and Security Principles and the New Zealand Farm Code, the EU Code is more detailed and offers a wealth of information in advocating the use of contractual agreements among those participating in data sharing (Atik, Reference Atik2022; Jakku et al., Reference Jakku, Taylor, Fleming, Mason, Fielke, Sounness and Thorburn2019). The EU’s code, while detailed, suffers from ambiguity in assigning responsibilities and using terminology not recognized by legal standards for data ownership (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Heath, McRobert, Llewellyn, Sanderson, Wiseman and Rainbow2021). This confusion can hinder effective application and understanding by all parties involved (Wiseman et al., Reference Wiseman, Sanderson, Zhang and Jakku2019). Larger agribusinesses may have more resources to understand and navigate the code, while small farmers may struggle to do so. For instance, the EU Code’s recommendation for “fair contracts” does not prevent agri-tech firms from embedding clauses that grant them broad licensing rights over farm data (Wiseman et al., Reference Wiseman, Sanderson, Zhang and Jakku2019).

Shortly thereafter, Australia followed with the National Farmers Federation’s Farm Data Code in 2020 (van der Burg et al., Reference van der Burg, Wiseman and Krkeljas2020; Kaur and Data, Reference Kaur and Dara2023). ATPs that meet the standards of the Code are allowed to showcase the Code’s mark on their website and documents (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Heath, McRobert, Llewellyn, Sanderson, Wiseman and Rainbow2021). Australia’s Farm Data Code (2020) prioritizes data portability so farmers can switch providers without losing data, but lacks compliance audits, relying instead on industry goodwill (Steup et al., Reference Steup, Dombrowski and Su2019; van der Burg et al., Reference van der Burg, Wiseman and Krkeljas2020). Unlike EU, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, no voluntary codes of conduct for agricultural data sharing have been adopted in the African region (Chichaibelu et al., Reference Chichaibelu, Baumüller and Matschuck2023).

These codes recommend farmers to get involved in contractual agreements with third parties to share their data. These agri-data sharing principles and codes of practice are not required by government legislation, and neither are agribusinesses obligated to participate in them; thus, they rely heavily on industry participation (Sanderson et al., Reference Sanderson, Wiseman and Poncini2018; van der Burg et al., Reference van der Burg, Wiseman and Krkeljas2020; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Heath, McRobert, Llewellyn, Sanderson, Wiseman and Rainbow2021). Hence, the effectiveness of these codes is limited by their voluntary nature. Furthermore, this means that even if a party violates the code, there may be limited resources for those affected. This lack of accountability can undermine trust in the system and deter participation. A lack of clear metrics makes it difficult to assess whether these codes improve data-sharing practices (Radauer et al., Reference Radauer, Searle and Bader2023). Although Sanderson et al. (Reference Sanderson, Wiseman and Poncini2018) suggest tracking farmer trust levels, current evaluations rely on anecdotal evidence, leaving gaps in understanding their long-term impacts.

In the absence of clearly defined legal data rights (Carbonell, Reference Carbonell2016), the National Cooperative Dairy Herd Improvement Program (NCDHIP) offers an example of voluntary data governance. It is a long-running U.S. program that coordinates the collection of farm-level data to support research on dairy cattle breeding and genetic selection, where farmers retain control through cooperative ownership. As Hutchins and Hueth (Reference Hutchins and Hueth2023) note, organizations like the Dairy Herd Improvement Associations (DHIAs) and Dairy Records Processing Centers (DRPCs) are “organized as cooperatives, owned by dairy farmers,” enabling members to influence how their data is used while protecting their sovereignty as data producers. GODAN (Global Open Data for Agriculture and Nutrition) represents another model of international cooperation, which prioritizes making agricultural and nutritional information available, accessible, and usable through open data initiatives (Rotz et al., Reference Rotz, Duncan, Small, Botschner, Dara and Mosby2019).

3.3. Technical enforcement

While legal frameworks define who may collect, access, and reuse agricultural data, they often stop short of ensuring these rights are respected in practice. Technology steps into this enforcement gap, not as a neutral solution, but as a mediator that operationalizes governance rules by embedding access and usage policies into digital infrastructures. These technical enforcement mechanisms aim to enable compliance, transparency, and accountability (Spanaki et al., Reference Spanaki, Karafili and Despoudi2021; Ur Rahman et al., Reference Ur Rahman, Baiardi and Ricci2020; Klug and Prinz, Reference Klug and Prinz2023). However, their effectiveness is fundamentally constrained by the rules they encode and the power dynamics they reflect.

Hummel et al. (Reference Hummel, Braun and Dabrock2020) argue that even in the absence of full legal property rights, the language of ownership continues to express a legitimate demand: the desire to reassert control over how data is accessed, used, and governed. In this context, ownership functions as a proxy for a bundle of rights: such as the ability to distribute, restrict, or revoke access, which enable individuals to shape data practices that affect them. Control, then, becomes the operative dimension of ownership, shifting focus from legal entitlement to functional agency. This emphasis on control aligns with Chaddad and Iliopoulos (Reference Chaddad and Iliopoulos2012), who argue that residual control rights ultimately determine who holds true authority over an asset, especially in settings where contracts are incomplete and enforcement is uncertain. This logic underpins data sovereignty: the sustained capacity to set, monitor, and revoke conditions for data use (Jarke et al., Reference Jarke, Otto and Ram2019; von Scherenberg et al., Reference von Scherenberg, Hellmeier and Otto2024). Yet, data sovereignty, as framed by Hummel et al. (Reference Hummel, Braun, Tretter and Dabrock2021) and recently expanded in von Scherenberg et al. (Reference von Scherenberg, Hellmeier and Otto2024), remains largely aspirational unless coupled with enforcement mechanisms. Technical infrastructure promises to make it actionable by automatically validating and executing rights defined in data-sharing contracts, acting as an intermediary layer between providers and consumers.

Several recent studies have explored how this vision of enforceable data sovereignty is being operationalized in practice, particularly through data-sharing platforms and technical infrastructures. Chandra and Collis (Reference Chandra and Collis2021) highlight the importance of developing data-sharing platforms that are secure, privacy-preserving, and aligned with principles of data sovereignty for enabling AI-based decision support in agriculture. Data sovereignty is also encountered in the study by Klug and Prinz (Reference Klug and Prinz2023), which illustrates how usage control policies and data sovereignty can be technically implemented within a modular, blockchain-supported data space for the agri-food sector. This enables the enforcement of usage rules that allow stakeholders to apply specific restrictions and policies to their shared data (Kiran et al., Reference Kiran, Dharanikota and Basava2019). However, such enforcement remains contingent upon the fairness of the predefined rules themselves. These platforms rely on a constellation of actors, data owners, providers, consumers, and users, each of whom plays a role in maintaining the integrity of data transactions (Šestak and Copot, Reference Šestak and Copot2023), yet this complex coordination often assumes equitable participation that may not reflect real-world power dynamics.

Proposed technical solutions are increasingly diverse. Kotal et al. (Reference Kotal, Elluri, Gupta, Mandalapu and Joshi2023) propose a framework for embedding privacy-policy rules into Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-based synthetic data generators by automatically extracting “permission/obligation/prohibition” clauses from regulations and enforcing attribute-level privacy during agricultural data sharing. However, the authors recognize that automatically extracting clauses from legal or contractual texts can misinterpret nuanced language, leading to either overly strict constraints that hamper utility or tolerate rules that risk non-compliance.

According to Nazarov and Nazarov (Reference Nazarov and Nazarov2023), smart contracts are proposed to lower the likelihood of data-sharing disputes through automatic execution when predefined conditions are met, with potential to foster trust among stakeholders. However, most agricultural implementations of smart contracts remain hypothetical, lacking empirical evidence of real-world impact. Nevertheless, the use of blockchain technology in agricultural data sharing has also been applied by Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Wang and Zheng2020). Rather than storing full datasets on the blockchain, the system records a concise “data summary,” essentially metadata describing the dataset and its access terms, as a blockchain transaction. This transaction is signed by the data owner’s private key and anchored to their public address, which binds ownership of that dataset to them. Any later access or sharing request must reference this on-chain summary to prove who originally published (and thus owns) the data. Building on this type of approach, Ur Rahman et al. (Reference Ur Rahman, Baiardi and Ricci2020) document an Enterprise Operating System (EOS) blockchain integrated with the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) that performs role-based permission checks on-chain. This system processes access requests by either granting or blocking them, while recording each decision immutably on the blockchain (Lou et al., Reference Lou, Bhat and Huang2023).

These enforcement mechanisms align technically with Article 33(1)(d) of the EU Data Act, which calls for interoperability mechanisms capable of automating the execution of data-sharing agreements, and Article 36 (1)(a), which lists the essential requirements of smart contracts for executing data-sharing agreements such as access control, safe termination, or resetting the contract as well as data archiving.

Several frameworks focus on usage control. Falcão et al. (Reference Falcão, Matar, Rauch, Elberzhager and Koch2023) propose a platform in which each farm is represented by a “digital field twin” that can be deployed across multiple hosting instances, intended to provide farmers true data portability and control over ownership. A consent manager handles permissions at field/data-item levels, while an access manager verifies requests against consents and logs transactions to an audit trail within the twin, automating permission checks and potentially preserving transparency. However, this current design prioritizes interoperability and sovereignty at the expense of other key quality attributes, most notably scalability, as the high volume of raw field data in large-scale operations may overwhelm both storage and processing components.

In parallel with these platform-oriented solutions, other work focuses on creating the technical conditions that allow such enforcement mechanisms to operate across heterogeneous systems. Interoperability standards like agro-XML, GS1 XML, and ISOagriNet (Lehmann et al., Reference Lehmann, Reiche and Schiefer2012) establish technical prerequisites for cross-platform enforcement system functionality. Sprenkamp et al. (Reference Sprenkamp, Delgado Fernández, Eckhardt and Zavolokina2024) position federated learning as a potential governance mechanism by maintaining data locality during collaborative training. These approaches technically correspond to EU Data Act Articles 33–35, which advocate open specifications for transport, semantic, behavioral, and policy interoperability across data services.

Alongside such platform-based approaches, efforts to formalize usage control also appear at the policy-specification layer. For instance, Matteucci et al. (Reference Matteucci, Petrocchi and Sbodio2010) developed the Controlled Natural Language for Data Sharing Agreements (CNL4DSA) as a method for specifying data-sharing agreements. Though not agriculture-specific, the tool sought to simplify complex policy languages and enable users to define Data Sharing Agreements (DSAs) with configurable privacy parameters and conflict identification capabilities prior to policy implementation. DSAs also form the basis of an artificial intelligence-based framework by Spanaki et al. (Reference Spanaki, Karafili and Despoudi2021) for role-based data access control in Agriculture 4.0. Their approach implements DSAs using argumentation reasoning, positioned as a method to manage complexities in multi-stakeholder agricultural data sharing. The authors suggest AI-driven DSAs may support regulatory alignment and offer mechanisms for reconciling competing stakeholder interests.

Policy enforcement mechanisms must address the full data lifecycle: from collection and processing to sharing, storage, and erasure (Amiri-Zarandi et al., Reference Amiri-Zarandi, Dara, Duncan and Fraser2022), including concepts like “sticky policies,” which are data usage rules embedded or attached to the data and that travel with data to enforce terms beyond the point of initial transfer (Spanaki et al., Reference Spanaki, Karafili and Despoudi2021). This aligns with the EU Data Act Article 4(7), which establishes that data becomes subject to erasure when no longer needed for the agreed purpose. Reflecting this, Kaur et al. (Reference Kaur, Hazrati Fard, Amiri-Zarandi and Dara2022) suggest ATPs incorporate retention clauses for postcontract data purging, while Amiri-Zarandi et al. (Reference Amiri-Zarandi, Dara, Duncan and Fraser2022) examine automated deletion protocols to limit residual data exposure. In theory, farmers could embed retention periods in agreements to mandate deletion, though practical enforcement remains contingent on their bargaining power and technical capacity to verify compliance.

Beyond legislative rights, the European Strategy for Data (European Commission, 2020) heavily promotes data spaces as the foundational infrastructure for sovereign data sharing (Jarke et al., Reference Jarke, Otto and Ram2019). Data spaces are decentralized environments that enable the reading and integration of diverse data from distributed sources, with the purpose of preserving the data owner’s control and sovereignty (Jarke et al., Reference Jarke, Otto and Ram2019; Falcão et al., Reference Falcão, Matar, Rauch, Elberzhager and Koch2023). Architectures like CEADS, GAIA-X, and the International Data Spaces (IDS) provide the reference models for this vision, where core technical components called “Connectors” enforce data-usage policies, ensuring participants retain sovereignty over their data by attaching and enforcing usage policies during exchange (Hellmeier et al., Reference Hellmeier, Pampus, Qarawlus and Howar2023). In agriculture, this model is seen as a pathway to trust and new value creation (Falcão et al., Reference Falcão, Matar, Rauch, Elberzhager and Koch2023; Klug and Prinz, Reference Klug and Prinz2023). Other proposed systems combine data spaces with blockchain technology to provide immutable traceability for consumers and create fair data monetization models that incentivize farmer participation (Klug and Prinz, Reference Klug and Prinz2023). Ultimately, the development of agricultural data spaces aligns with broader EU policy goals, such as those enshrined in the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) (Klug and Prinz, Reference Klug and Prinz2023), by aiming to create a more transparent, fair, and valued position for farmers in the digital value chain (Jarke et al., Reference Jarke, Otto and Ram2019; Atik, Reference Atik2022; Klug and Prinz, Reference Klug and Prinz2023; Šestak and Copot, Reference Šestak and Copot2023).

Despite these advancements, implementation barriers remain. High costs, energy demands, and complexity deter adoption, especially among smallholders, potentially exacerbating the digital divide (Ryan, Reference Ryan2019; Nazarov and Nazarov, Reference Nazarov and Nazarov2023). Blockchain’s technical constraints (latency, fees) further limit real-world applicability in data-intensive farming (Ur Rahman et al., Reference Ur Rahman, Baiardi and Ricci2020). Critically, these tools merely automate governance as they cannot resolve core ambiguities around data ownership, consent, or benefit allocation. By enforcing predefined rules without addressing who sets them or for whose benefit, technologies risk institutionalizing existing power asymmetries (e.g., ATP-favorable EULAs) or creating new friction points.

4. Discussion

This systematic review synthesizes a decade of scholarship on agricultural data ownership and governance, revealing a landscape characterized by fundamental tensions between data ownership and data sharing. This section draws on foundational theoretical frameworks from property theory (Locke, Reference Locke and Laslett1988; Honoré, Reference Honoré1988), commons governance (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990; Hess and Ostrom, Reference Hess and Ostrom2007), and science and technology studies (Winner, Reference Winner1980; Morozov, Reference Morozov2013; Pistor, Reference Pistor2019) to provide a structure to interpret our findings and position them within broader scholarly debates.

Our analysis demonstrates that agricultural data constitutes a relational asset whose value emerges not from exclusive possession but from contextual circulation, combinatorial synthesis, and multi-stakeholder cocreation (EU, 2019; Falcão et al., Reference Falcão, Matar, Rauch, Elberzhager and Koch2023; Kotal et al., Reference Kotal, Elluri, Gupta, Mandalapu and Joshi2023; Bacco et al., Reference Bacco, Kocian, Chessa, Crivello and Barsocchi2024). This relational nature fundamentally challenges the Lockean labor theory of property that underpins traditional intellectual property regimes, where individual effort confers ownership rights (Locke, Reference Locke and Laslett1988). In agricultural contexts, data generation represents a collaborative process: farmer decisions, proprietary sensor technologies, and algorithmic processing converge to produce information whose authorship cannot be singularly attributed (Ellixson and Griffin, Reference Ellixson and Griffin2016; Ellixson et al., Reference Ellixson, Griffin, Ferrell and Goeringer2018; DeLay et al., Reference DeLay, Boehlje and Ferrell2023). Moreover, the nonrivalrous and infinitely replicable nature of data further destabilizes conventional property paradigms (Arrow, Reference Arrow1962). Unlike physical assets subject to scarcity constraints, data can be simultaneously utilized by multiple actors without depletion, rendering exclusive control both economically inefficient and technically unenforceable (Idowu et al., Reference Idowu, Wachenheim, Hanson and Sickler2023; Radauer et al., Reference Radauer, Searle and Bader2023). This condition creates what Hess and Ostrom (Reference Hess and Ostrom2007) describe as a knowledge commons dilemma: while openness maximizes innovation potential, individual actors face incentives to restrict access for competitive gain, producing socially suboptimal outcomes.

Regulatory responses increasingly acknowledge these complexities. The EU Data Act (Regulation (EU) 2023/2854, 2023) strategically avoids defining data ownership, instead articulating a bundle of separable access, usage, and portability rights (Atik, Reference Atik2022, Reference Atik2023). This legislative approach operationalizes Honoré’s (Reference Honoré1988) classic decomposition of property into distinct incidents: “usus” (right to use), “fructus” (right to benefit), and “abusus” (right to dispose), while recognizing that these rights may be distributed across multiple stakeholders rather than concentrated in a singular owner. This shift from ownership to rights-based governance marks a conceptual evolution with data’s unique characteristics, yet its practical implementation remains contested and incomplete.

This discussion develops four key arguments from our synthesis: the political economy of power asymmetries (4.1), the paradigm shift from ownership to sovereignty (4.2), participatory governance as an integrative solution (4.3), and a policy blueprint for closing the enforcement gap (4.4).

4.1. Power asymmetries and structural disempowerment: the political economy of agricultural data

The conceptual ambiguity surrounding data ownership creates structural conditions for systematic power imbalances that disadvantage farmers within corporate-controlled data ecosystems. Our analysis reveals that Agricultural Technology Providers (ATPs) leverage superior technical expertise, legal resources, and market positioning to embed expansive data appropriation claims within unclear contractual instruments (Sykuta, Reference Sykuta2016; Ruder, Reference Ruder2024). Kaur and Dara (Reference Kaur and Dara2023) demonstrate that most agricultural data agreements are written at readability levels far beyond farmers’ comprehension, creating information asymmetries that undermine informed consent.

This dynamic exemplifies what Pistor (Reference Pistor2019) terms the code of capital, the strategic deployment of legal instruments to encode and entrench economic advantage. EULAs and data licenses function as private regulatory regimes that determine data governance in the absence of clear statutory frameworks (Fairbairn and Kish, Reference Fairbairn and Kish2023; Montenegro De Wit and Canfield, Reference Montenegro De Wit and Canfield2024). The result is a systematic transfer of power from data generators (farmers) to data processors (ATPs), optimizing data flows for corporate monetization rather than equitable benefit distribution (Hackfort et al., Reference Hackfort, Marquis and Bronson2024). Regulatory lag exacerbates these power asymmetries. Legal systems struggle to adapt to rapidly evolving data collection and analytics technologies, creating temporal gaps that favor technologically sophisticated actors (Carbonell, Reference Carbonell2016; Uddin et al., Reference Uddin, Chowdhury and Kabir2022). While voluntary codes of conduct emerge as industry-led governance mechanisms, their nonbinding nature and lack of enforcement infrastructure limit effectiveness in countering structural imbalances (Sanderson et al., Reference Sanderson, Wiseman and Poncini2018; Wiseman et al., Reference Wiseman, Sanderson, Zhang and Jakku2019; van der Burg et al., Reference van der Burg, Wiseman and Krkeljas2020). Sector-specific variations further complicate governance (Atik, Reference Atik2022, Reference Atik2023).

4.2. From ownership to sovereignty: a necessary paradigm shift

A central finding of this review is that the concept of data ownership is increasingly being sidelined in both policy and scholarly discourse, recognized as a source of intractable ambiguity rather than a governance solution (Hummel et al., Reference Hummel, Braun and Dabrock2020; Atik, Reference Atik2022). Our analysis demonstrates that ownership rhetoric retains utility for expressing moral claims or legitimate demands for control (Hummel et al., Reference Hummel, Braun and Dabrock2020) but fails as a precise legal instrument for governing agricultural data ecosystems. This is not merely an academic observation but reflects deliberate policy choices, most notably exemplified by the EU Data Act’s strategic avoidance of ownership definitions in favor of dynamically allocated access and usage rights (Atik, Reference Atik2022, Reference Atik2023). This legislative approach signals a broader paradigm shift from ownership-centric to sovereignty-focused frameworks (Hummel et al., Reference Hummel, Braun and Dabrock2020; Atik, Reference Atik2022). Data sovereignty reframes governance debates from the static question “Who owns it?” to the dynamic, operational question: “Who can control what happens to it, under what conditions, and subject to what accountability mechanisms?” (Jarke et al., Reference Jarke, Otto and Ram2019; von Scherenberg et al., Reference von Scherenberg, Hellmeier and Otto2024). This reframing acknowledges that agricultural data’s value derives not from possession but from circulation, combination, and contextual application, necessitating governance models that manage flows and value distribution rather than adjudicating contested ownership titles. The sovereignty paradigm operationalizes Ostrom’s (Reference Ostrom1990) insights on common-pool resource governance: effective management of shared resources requires clearly defined boundaries, participatory rulemaking, graduated sanctions, conflict resolution mechanisms, and nested institutional arrangements.

Technology is increasingly positioned as a mechanism for operationalizing data sovereignty, defined as the sustained capacity to set, monitor, and revoke conditions for data use (Jarke et al., Reference Jarke, Otto and Ram2019; von Scherenberg et al., Reference von Scherenberg, Hellmeier and Otto2024). Blockchain-based smart contracts, federated learning architectures, and cryptographic usage control systems offer potential for transparent, auditable, and automated enforcement of data-sharing agreements (Klug and Prinz, Reference Klug and Prinz2023; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Wang and Zheng2020; Nazarov and Nazarov, Reference Nazarov and Nazarov2023; Sprenkamp et al., Reference Sprenkamp, Delgado Fernández, Eckhardt and Zavolokina2024). These technologies promise to resolve the enforcement gap between nominal rights and practical control by embedding governance rules directly into technical infrastructure. However, our analysis reveals fundamental paradoxes in technical enforcement approaches.

First, technology operates as an executor of predefined rules rather than a determinant of those rules’ substantive content. If underlying contractual agreements embed exploitative terms, technical systems merely automate and entrench existing inequities rather than resolving them (Ryan, Reference Ryan2019; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Regan and van der Burg2023). This reflects Winner’s (Reference Winner1980) classic insight that technologies embody political choices. Blockchain systems are not neutral arbiters but implementations of particular governance logics that may reproduce power asymmetries. Second, sophisticated technical solutions impose significant adoption barriers, high costs, energy demands, computational complexity, and specialized expertise requirements, that systematically exclude smallholders and resource-constrained farmers (Regan, Reference Regan2019; Ur Rahman et al., Reference Ur Rahman, Baiardi and Ricci2020; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Heath, McRobert, Llewellyn, Sanderson, Wiseman and Rainbow2021; Lioutas et al., Reference Lioutas, Charatsari, La Rocca and De Rosa2019).