Introduction

Mental health technology (MHT) encompasses various digital tools used in mental health, including applications, social media, artificial intelligence (AI), telehealth, online therapy, and chatbots. These technologies allow digital platforms, devices, and software to deliver mental health services and resources, potentially making them more accessible, affordable, convenient, efficient, and personalised for individuals seeking mental health support.

This rapidly expanding field presents new opportunities, but also significant challenges, for delivering personalised mental health interventions at scale (Richards & Richardson, Reference Richards and Richardson2012, Torous et al. Reference Torous, Andersson, Bertagnoli, Christensen, Cuijpers, Firth, Haim, Hsin, Hollis, Lewis, Mohr, Pratap, Roux, Sherrill and Arean2019).

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the use of various components of MHT (O’Brien & McNicholas, Reference O’Brien and McNicholas2020, Twomey et al. Reference Twomey, O’Reilly and Byrne2013, Wright & Caudill, Reference Wright and Caudill2020). Many approaches, including video-enabled psychology sessions, telehealth for outpatient appointments via conferencing software, and digital cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), were scaled up to meet large-scale public demand (Corruble, Reference Corruble2020). Significant demand on limited resources has also increased the popularity of such platforms, allowing many service users to access mental health supports without limitations based on geography or lack of staffing (Timulak et al. Reference Timulak, Richards, Bhandal-Griffin, Healy, Azevedo, Connon, Martin, Kearney, O’Kelly, Enrique, Eilert, O’Brien, Harty, González-Robles, Eustis, Barlow and Farchione2022).

In the wake of the pandemic, there is an ongoing appraisal of the balance between traditional models of care, such as face-to-face consultation, and the integration of complementary digitally enabled solutions, especially in the context of increased demand and growing waiting lists (HSE, 2025c, Ndayishimiye et al. Reference Ndayishimiye, Lopes and Middleton2023).

Accumulating evidence suggests that internet-based CBT, including virtual/digital therapists, may be helpful for a range of mild to moderate mental health conditions (Carl et al. Reference Carl, Miller, Henry, Davis, Stott, Smits, Emsley, Gu, Shin, Otto, Craske, Saunders, Goodwin and Espie2020, Hedman-Lagerlöf et al. Reference Hedman-Lagerlöf, Carlbring, Svärdman, Riper, Cuijpers and Andersson2023, Lee et al. Reference Lee, Harty, Adegoke, Palacios, Gillan and Richards2024, Lee et al. Reference Lee, Palacios, Richards, Hanlon, Lynch, Harty, Claus, Swords, O’Keane, Stephan and Gillan2023, Loveys et al. Reference Loveys, Sagar, Pickering and Broadbent2021, Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Fan, Ma, Wang, Zu, Yang, Chen, Wei and Li2024). Furthermore, regulators are starting to approve digital therapeutics for mental health purposes (Assmann et al. Reference Assmann, Jacob, Schaich, Berger, Zindler, Betz, Borgwardt, Arntz, Fassbinder and Klein2025, Phan et al. Reference Phan, Mitragotri and Zhao2023). Recently, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first prescription of a “digital therapeutic” app as an adjunct to clinician-managed outpatient care for major depressive disorder (Rejoyn, 2024).

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recently published early value assessment guidance on MHT, including virtual reality (VR) technology for managing psychosis symptoms in adults and young people (Freeman et al. Reference Freeman, Lambe, Kabir, Petit, Rosebrock and Yu2022, Freeman et al. Reference Freeman, Lister, Waite, Galal, Yu and Lambe2023, NICE, 2024).

Ireland’s national mental health policy, “Sharing the Vision,” recommends that “evidence-based digital and social media channels should be used to the maximum to promote mental health and to provide appropriate signposting to services and supports and develop the potential for digital health solutions to enhance service delivery and empower service users” (HSE, 2024, 2025b).

The adoption of MHT unfolds within a broader conversation about how service delivery models adapt to evolving technological, social, and demographic realities. According to established technology acceptance frameworks such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), user uptake is shaped by factors including perceived usefulness, ease of use, trust, social influence, and accessibility (Alojail, Reference Alojail2024, Lee et al. Reference Lee, Ramasamy and Subbarao2025).

Attitudes towards MHT are further influenced by perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and external cues (Muruganantham et al. Reference Muruganantham, Hezerul Abdul and Sarina Binti2024). Digital literacy, age, and socio-economic status contribute to the digital divide, requiring equitable implementation strategies that address both structural and attitudinal barriers. Age also plays a moderating role, with older users particularly affected by perceptions of ease of use and vulnerability (Muruganantham et al. Reference Muruganantham, Hezerul Abdul and Sarina Binti2024).

Other influential variables include technology anxiety, resistance to change, and concerns about data privacy (Rajak & Shaw, Reference Rajak and Shaw2021). To address these concerns and promote adoption, stakeholder readiness and targeted educational interventions are critical components of a comprehensive implementation strategy (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Ramasamy and Subbarao2025).

Opinions among service users/patients and the public are mixed. In general, there is openness to implementation provided it is accompanied by regulation, data security, and transparent human oversight, particularly in relation to decision-making processes (Hoffman et al. Reference Hoffman, Oppert and Owen2024, IPPOSI, 2025, Kim et al. Reference Kim, Vegt, Visch and Vos2024, Miller et al. Reference Miller, Gilbert, Virani and Wicks2020, Robertson et al. Reference Robertson, Woods, Bergstrand, Findley, Balser, Slepian and Shah2023, Young et al. Reference Young, Amara, Bhattacharya and Wei2021).

A survey of individuals with severe mental health problems (n = 447) in an outpatient setting in Beijing, China, found that despite high ownership and use of digital technologies, fewer than half used these platforms frequently for health-related purposes. This may be partly due to limited knowledge in using MHT (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lewis, Chen, Berry and Bucci2023).

A similar study conducted in Ireland among patients (n = 61) at a general practice found that only 39% of participants were aware of technology-based resources to support their mental health, and only 11% had ever used them. Interestingly, 72% reported that they would find it helpful if their general practitioner (GP) recommended digital resources for mental health issues (Finucane, Reference Finucane2019)

Given the rapid advance of MHT, understanding mental health service user attitudes may help to identify barriers to successful adoption and facilitate assessment of accessibility and effectiveness. This paper sought to explore the use of and attitudes towards MHT technologies among attendees of a public community mental health service in Ireland.

Methods

Ethical approval

Tallaght University Hospital/St. James’s Hospital Joint Research Ethics Committee approved this study (Project ID:3669).

Survey design

A questionnaire was designed, informed by previous studies (Nogueira-Leite et al. Reference Nogueira-Leite, Diniz and Cruz-Correia2023, Nogueira-Leite et al. Reference Nogueira-Leite, Marques-Cruz and Cruz-Correia2024) and structured to reflect constructs found in technology acceptance frameworks such as TAM and UTAUT, including perceived knowledge, comfort, and interest in digital tools.

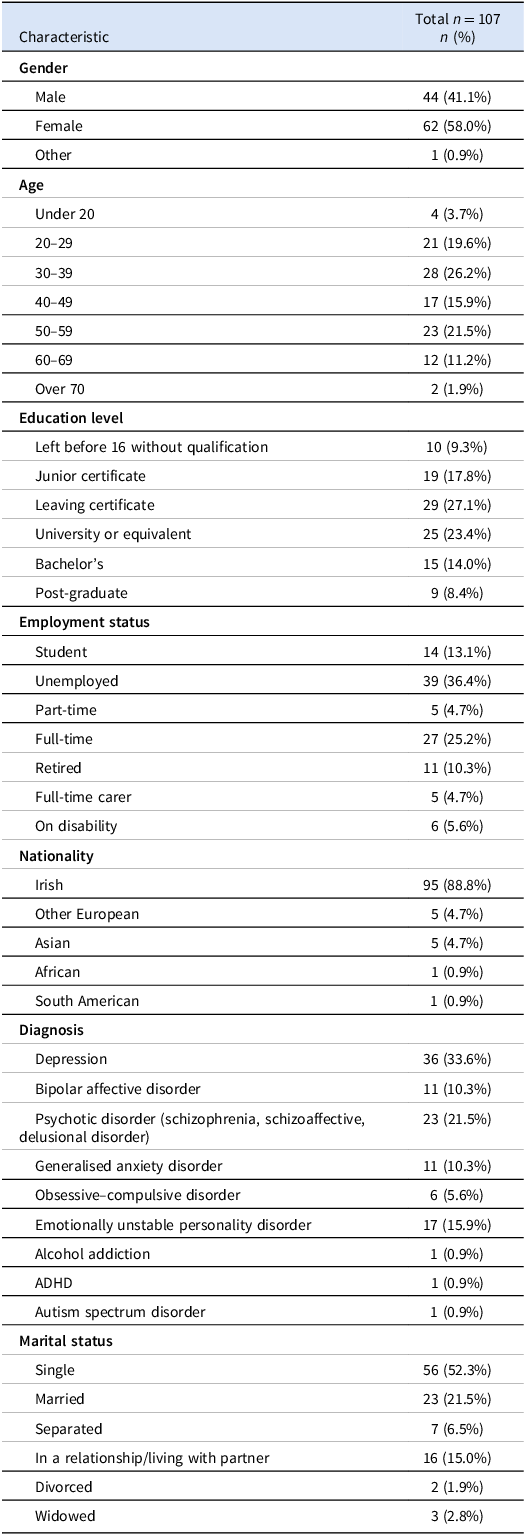

Basic demographic details, including age, gender, educational level, employment status, marital status, and nationality, were collected. The diagnoses of the participants were also recorded.

A 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, somewhat agree, neither/neutral, somewhat disagree, and strongly disagree) was used to capture attitudes about MHT in several domains, including (1) mobile apps, (2) online therapy and counselling, (3) telehealth, (4) web-based programmes, (6) chatbots, and (7) social media. The Likert-scale items were designed to assess respondents’ perceived knowledge, comfort, past usage, and willingness to engage with each MHT modality.

Participants were asked to rank their preferences for mental health appointments and what technological resources they would prefer to use to manage their mental health between appointments/on waiting lists. See the supplementary materials for the survey and the participant information leaflet.

Participants and procedure

The sample of service users was selected using convenience sampling at outpatient appointments between January 2024 to July 2024. Prior to commencement of the survey, an information leaflet was given to participants, and informed consent was signed.

Inclusion Criteria: Adult (≥18 years) service users attending the Dublin South Central Community Mental Health Service and diagnosed with a mental health condition.

Exclusion Criteria: Service users with cognitive impairment or learning disability interfering with the ability to consent or understand the survey, service users with active mental health crises, service users with active psychotic symptoms, and any service users who could not provide informed consent to participate.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 29.0.2.0 (20) for Mac. Frequencies of responses to questions were examined (Supplementary Tables S1, S2, S3), and the non-parametric Chi-square test was used to compare answers between age groups (Supplementary Table S4). For detailed analysis, survey responses on the Likert scale were recoded to yes, no, or neutral. Secondary analyses examined outcomes stratified by age group (divided into <30, 30–49, and ≥50). The Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate correction was used.

Results

A total of 107 participants completed the questionnaire. Demographics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic information of participants

Technology device ownership and use

The majority of participants 92 (86%) owned a smartphone, more than half 63 (58.9%) had a desktop or laptop computer, under a third 33 (30.8%) had a tablet, 11 (10.3%) had a non-smartphone mobile phone, 18 (16.8%) reported owning a wearable device such as a smart watch, and 6 (5.6%) denied owning any of these devices (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Technology device ownership and internet use. A. The majority of participants, 86% owned a smartphone, 58.9% had a desktop or laptop computer, 30.8% had a tablet, 10.3% had a non-smartphone mobile phone, 16.8% reported owning a wearable device such as a smart watch, and 5.6% did not own any of these devices. B. 28% reported using the internet almost constantly, 29% many times a day, 13.1% occasionally, 19.6% a few times a day, 1.9% weekly, 0.9% monthly, and 7.5% never.

Of 107 participants, 30 (28%) reported using the internet almost constantly, 31 (29%) many times a day, 14 (13.1%) occasionally, 21 (19.6%) a few times a day, 2 (1.9%) weekly, 1 (0.9%) monthly, and 8 (7.5%) never (Figure 1B).

Previous psychotherapy (with a human)

14 participants (13.1%) reported never attending psychological therapy, 55 (51.4%) reported having previously attended, 32 (29.9%) reported currently attending, and 6 (5.6%) reported being currently on a waitlist.

Mental health apps

Among those who reported using a mental health app, 8 (7.5%) used Headspace, 7 (6.5%) used CALM, 1 used YouTube, and 13 did not specify the app. 52 (48.6%) participants disagreed or strongly disagreed that they were knowledgeable about mental health apps, while over a third, 42 (39.3%), agreed or strongly agreed that they would feel comfortable using these apps (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Attitudes towards mental health technologies. A. Use of and interest in social media, VR, AI, internet-delivered therapy, and mental health apps. B. Knowledge and comfort using the various mental health technologies.

Fifteen service users shared additional details about their app usage, highlighting benefits such as providing helpful information, aiding meditation, reducing anxiety, offering support, or improving sleep. One service user described their app as “too hard to use when anxious.”

There was no significant difference in reports of feeling knowledgeable about apps by age (χ 2 = 12.06, df = 4, p = 0.32). Still, significantly more participants aged over 50 reported not being comfortable using apps (χ 2 = 25.97, df = 4, p < 0.01) compared to younger participants. In contrast, a larger proportion of those aged 30–49 were neutral or positive about using apps (see Supplementary Table S4).

Internet-delivered therapy

44 (41.1%) participants reported not having used internet-delivered therapy, such as CBT, and not being interested in it. 42 (39.3%) reported not having used but being interested in internet-delivered therapy. 16 (15%) reported having used it in the past, and 5 (4.7%) reported currently using such therapy (Figure 2A). Of those who had used internet-delivered therapy, 10 reported having used SilverCloud (digital CBT service that the HSE provides in Ireland), and 6 reported having used another form of remote therapy, while 5 participants did not answer.

Some users reported that internet-delivered therapy was beneficial due to its convenience, the scarcity of specialists in Ireland, and the flexibility it offers. However, one participant described internet-delivered therapy as impersonal.

Additionally, 48 participants (44.9%) disagreed or strongly disagreed that they were knowledgeable about internet-delivered therapy, while 45 participants (42.1%) agreed or strongly agreed that they would feel comfortable using it (Figure 2).

There was no significant difference between participants feeling knowledgeable about (χ 2 = 8.27, df = 4, p = 0.88) or comfortable with (χ 2 = 6.85, df = 4, p = 0.88) internet-delivered therapies between age groups (see Supplementary Table S4).

Artificial intelligence

See Figure 3A for attitudes to AI. There was no difference between comfort using AI for mental health between age groups (χ 2 = 3.11, df = 4, p = 0.88), but significantly more service users between 30–49 and under the age of 30 reported feeling knowledgeable about AI (χ 2 = 24.63, df = 4, p < 0.01). No other item differed significantly by age group (see Supplementary Table S4).

Figure 3. Attitudes to AI and concerns about mental health technologies. A. Participants’ feelings and beliefs about AI. B. Concerns and worries about mental health technologies.

Virtual reality

10 (9.3%) participants strongly agreed that they were knowledgeable about VR technology, 21 (19.6%) agreed, 15 (14%) felt neutral, 31 (29%) disagreed, and 30 (28%) strongly disagreed that they were knowledgeable about VR. Four (3.7%) participants strongly agreed that they would feel comfortable using VR for their mental health, 22 (20.6%) agreed, 24 (22.4%) felt neutral, 27 (25.2%) disagreed, and 30 (28%) strongly disagreed.

There were no significant differences in feeling knowledgeable about (χ 2 = 7.03, df = 4, p = 0.88) or comfortable with (χ 2 = 6.23, df = 4, p < 0.88) VR by age group (see Supplementary Table S4).

Social media

8 (7.5%) participants said they were currently using social media as a resource for managing their mental health, 35 (32.7%) said they were not at present but had in the past, 14 (13.1%) reported not having done so but being interested in doing so and 50 (46.7%) reported not having done so and not being interested in doing so. Those who had used social media reported using Facebook (16 participants), TikTok (9 participants), and Instagram (10 participants) (Figure 2A).

Of the 43 participants who had used social media, 2 participants strongly agreed that using social media for their mental health was beneficial, 20 agreed that it was beneficial, 12 were neutral, and five disagreed that it was beneficial. Four did not answer. Those who said it was beneficial described using social media to “answer questions” or because it was “educational” or “informative,” or to seek out peer support “connect with others,” “listen to others’ stories” and “learn about others’ experiences,” or to use it as a “distraction.”

8 (7.5%) participants strongly agreed that they were knowledgeable about mental health resources on social media, 32 (29.9%) agreed, 23 (21.5%) were neutral, 25 (23.4%) disagreed, and 19 (17.8%) strongly disagreed. Three (2.8%) participants strongly agreed that they felt comfortable using mental health resources on social media, 27 (25.2%) agreed, 23 (21.5%) felt neutral, 29 (27.1%) disagreed, and 25 (23.4%) strongly disagreed (Figure 2B).

There were no significant differences in feeling knowledgeable about (χ 2 = 9, df = 4, p = 0.88) or comfortable with (χ 2 = 8.22, df = 4, p = 0.88) social media by age group (see Supplementary Table S4).

Concerns and worries about technology use

The majority of participants reported at least one concern about using digital platforms for managing their mental health. Slightly more than half the participants, 56 (52.6%), would consider using technology for mental health while on a waiting list, but half the participants, 54 (50.4%), also endorsed having concerns about these platforms dealing with sensitive mental health matters (Figure 3B).

Appointment delivery preference

93 (86.9%) participants ranked mental health appointments that were face-to-face with a person as most preferable, 8 (7.5%) would most prefer online with a person, 2 (1.9%) most preferred telephone appointments with a person, and 2 (1.9%) most preferred online with an AI chatbot (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Preferred options for mental health appointments and while on the waiting list. A. The majority of mental health service users preferred face-to-face mental health appointments (86.9%), whereas 7.5% would most prefer online with a person, 1.9% would most prefer telephone appointments with a person, and 1.9% would most prefer online appointments with an AI chatbot. B. First preferences for technological resources participants would most prefer to use to manage their mental health between appointments were split, with 30.8% most preferring websites or online forums or communities, 26.2% most preferring AI chatbots, 23.4% preferring mental health apps, and 17.8% preferring social media.

First preferences for which technological resources participants would most prefer to use to manage their mental health between appointments were split, with 33 (30.8%) most preferring websites or online forums or communities, 28 (26.2%) most preferring AI chatbots, 25 (23.4%) preferring mental health apps, and 19 (17.8%) preferring social media (Figure 4B).

Discussion

This study provided further insights into the attitudes of mental health service users towards the rapidly evolving field of MHT. Overall, there were low levels of knowledge about and comfort using MHT. Younger participants were generally more comfortable with and knowledgeable about mobile apps and AI-based interventions.

Notably, nearly half of the total sample reported concerns regarding confidentiality and privacy when using MHT. These reservations underscore the need to address issues of privacy and security and highlight the importance of providing appropriate education and training to support the safe and effective integration of MHT into clinical practice.

The findings reinforce key concerns outlined in national strategy documents, particularly the call for digital mental health solutions that are evidence-based, person-centred, and adaptable to diverse user needs (HSE, 2025a, b).

While there is clear interest in digital mental health interventions, especially among younger service users, the data also highlight persistent concerns around trust, accessibility, and acceptability. These align with constructs from the TAM and UTAUT, which emphasise perceived usefulness, ease of use, and social influence as critical drivers of adoption (Alojail, Reference Alojail2024).

Empirical evidence suggests that perceived usefulness and trust strongly predict young people’s intention to use digital interventions, whereas ease of use is less influential (Sawrikar & Mote, Reference Sawrikar and Mote2022). For adults with intellectual disabilities, usability factors such as visual design, support needs, and basic digital skills are crucial to meaningful engagement (Vereenooghe et al. Reference Vereenooghe, Trussat and Baucke2021).

Similar themes emerge in research on mobile health apps, where user trust and social cues significantly shape adoption patterns (Russell et al. Reference Russell, Lloyd-Houldey, Memon and Yarker2018). These findings underscore the importance of designing digital mental health interventions that are not only technically sound but also responsive to users’ lived contexts and varying levels of digital confidence.

Our findings of low levels of knowledge about MHT are in line with previous studies in Ireland (Finucane, Reference Finucane2019). Similarly, concerns around confidentiality, privacy, and trust when using MHT echo previous studies of service users, psychiatrists, and psychologists (Carlbring et al. Reference Carlbring, Hadjistavropoulos, Kleiboer and Andersson2023, Cummins & Schuller, Reference Cummins and Schuller2020, Sunarti et al. Reference Sunarti, Fadzlul Rahman, Naufal, Risky, Febriyanto and Masnina2021). Indeed, there have been notable data protection issues. For example, in the United States, controversy has surrounded a popular mental health app following allegations that it sold users’ data to third parties (Neporent, Reference Neporent2024).

Surprisingly, social media was the most used platform for mental health purposes. This may also raise concerns about the underlying quality of evidence and broader worries about people, especially younger people, navigating potential misinformation (Hudon et al. Reference Hudon, Perry, Plate, Doucet, Ducharme, Djona, Testart Aguirre and Evoy2025).

The second most commonly used platform was mental health apps. In our sample, 86% of participants owned a smartphone, slightly below the reported national ownership rate of 95% in Ireland (Deloitte Ireland LLP, 2024). Despite this high level of access, only a quarter of our participants reported current or previous use of mental health apps. This proportion is even lower than that reported in a previous study of individuals with mental health disorders in Beijing, where fewer than half frequently used such platforms for health-related purposes (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lewis, Chen, Berry and Bucci2023).

Notably, over one-third expressed interest in using such apps in the future. However, it should also be noted that relatively few digital mental health apps have received formal approval (Rejoyn, 2024) and many have limited scientific validation, regulatory oversight, or robust evidence supporting their effectiveness (Anthes, Reference Anthes2016, Neary & Schueller, Reference Neary and Schueller2018).

AI has the potential to transform multiple facets of healthcare, ranging from risk prediction and patient monitoring to non-clinical administrative tasks (Eisemann et al. Reference Eisemann, Bunk, Mukama, Baltus, Elsner, Gomille, Hecht, Heywang-Köbrunner, Rathmann, Siegmann-Luz, Töllner, Vomweg, Leibig and Katalinic2025, Ginder et al. Reference Ginder, Li, Halperin, Akar, Martin, Chattopadhyay and Upadhyay2023, Johri et al. Reference Johri, Jeong, Tran, Schlessinger, Wongvibulsin, Barnes, Zhou, Cai, Van Allen, Kim, Daneshjou and Rajpurkar2025, Moritz et al. Reference Moritz, Topol and Rajpurkar2025, Osipov et al. Reference Osipov, Nikolic, Gertych, Parker, Hendifar, Singh, Filippova, Dagliyan, Ferrone, Zheng, Moore, Tourtellotte, Van Eyk and Theodorescu2024). AI-assisted therapeutic chatbots are progressing at a rapid pace, and their ability to emulate empathy seems to be improving (Boucher et al. Reference Boucher, Harake, Ward, Stoeckl, Vargas, Minkel, Parks and Zilca2021, Carlbring et al. Reference Carlbring, Hadjistavropoulos, Kleiboer and Andersson2023, Heinz et al. Reference Heinz, Mackin, Trudeau, Bhattacharya, Wang, Banta, Jewett, Salzhauer, Griffin and Jacobson2025, Kuhail et al. Reference Kuhail, Alturki, Thomas and Alkhalifa2024, Raile, Reference Raile2024). This raises interesting issues for personalised preferences for non-human therapeutic approaches for those individuals who may feel more at ease sharing their experiences with AI-based therapists (Hoffman et al. Reference Hoffman, Oppert and Owen2024) and cultural differences (Chin et al. Reference Chin, Song, Baek, Shin, Jung, Cha, Choi and Cha2023).

While some studies report generally open attitudes and acceptance among service users (Abd-Alrazaq et al. Reference Abd-Alrazaq, Alajlani, Ali, Denecke, Bewick and Househ2021, Limpanopparat et al. Reference Limpanopparat, Gibson and Harris2024), significant gaps remain in the standardisation of reporting and evaluation frameworks. There is a need for greater transparency, methodological consistency, and replicability in chatbot research (Vaidyam et al. Reference Vaidyam, Wisniewski, Halamka, Kashavan and Torous2019), and many service users, psychiatrists, and other mental health professionals maintain a cautious stance (Blease et al. Reference Blease, Worthen and Torous2024, Siddals et al. Reference Siddals, Torous and Coxon2024, Sweeney et al. Reference Sweeney, Potts, Ennis, Bond, Mulvenna, O’neill, Malcolm, Kuosmanen, Kostenius, Vakaloudis, Mcconvey, Turkington, Hanna, Nieminen, Vartiainen, Robertson and Mctear2021).

A study of mental health professionals (n = 160) in Portugal showed that less than half (43.6%) of the respondents planned to prescribe or recommend digital mental health apps to their patients, with psychologists holding slightly more favourable attitudes than psychiatrists (Nogueira-Leite et al. Reference Nogueira-Leite, Diniz and Cruz-Correia2023).

Additionally, almost half of our respondents were not comfortable with their psychiatrist or GP utilising AI in supporting decisions about their care. In a survey of 138 psychiatrists affiliated with the American Psychiatric Association, approximately 40% reported using ChatGPT to assist in answering clinical questions, and 70% agreed that generative AI will help with documentation and reducing administrative burden (Blease et al. Reference Blease, Worthen and Torous2024). Interestingly, GPT-4 outperformed both psychiatry residents and open-source models in diagnostic and knowledge tasks (Bang et al. Reference Bang, Jung, You, Kim and Kim2025).

The majority of participants in our study voiced discomfort utilising AI in any aspect of their lives, rising to almost 60% about healthcare specifically. The scepticism went even further, as less than 40% of the participants believed that AI would benefit human mental health over the next two decades, dropping to below 30% when applied to beliefs around their own mental health.

Younger respondents, as expected, felt more knowledgeable about AI than their older peers. This highlights the age divide in digital literacy and comfort. Previous literature has theorised that AI chatbots may be appealing to younger people in general due to their familiarity with existing online platforms (Koulouri et al. Reference Koulouri, Macredie and Olakitan2022). It also emphasises that for AI to be widely adopted in psychiatry, substantial efforts must be made to educate and support older service users.

Notwithstanding the advancing competencies of AI, the majority of participants in our study expressed a clear preference for face-to-face mental health appointments. However, just over half of the participants said they would consider using MHT while on a waiting list. This suggests its potential as a complementary tool to clinician-led conventional care and a possible support within the HSE’s Waiting List Action Plan – Beyond the Wait (HSE, 2025c).

Our study, in line with previous research, highlights the need for a guided approach and associated training if MHT is to be successfully delivered in a public psychiatric clinic (Breedvelt et al. Reference Breedvelt, Zamperoni, Kessler, Riper, Kleiboer, Elliott, Abel, Gilbody and Bockting2019, McCausland et al. Reference McCausland, McCarron and McCallion2023, Nogueira-Leite et al. Reference Nogueira-Leite, Diniz and Cruz-Correia2023).

To advance the implementation of MHT, it is essential to co-design digital care pathways with service users, recognising both demographic differences and varying levels of attitudinal readiness. As Ireland progresses towards its Digital for Care 2030 goals, translating high-level policy into equitable and effective practice demands sustained engagement with the lived realities of front-line mental health services. Co-design has been shown to improve user engagement, tailor interventions to individual needs, and empower participants in the therapeutic process (Veldmeijer et al. Reference Veldmeijer, Terlouw, Van Os, Van Dijk, Van’t Veer and Boonstra2023).

However, challenges persist in sustaining meaningful participation and balancing service user insights with clinical frameworks. Research suggests that digital innovation in mental health care requires systemic adjustments, such as revised clinical roles and the introduction of digital navigators to support users (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Blease, Faurholt-Jepsen, Firth, Van Daele, Moreno, Carlbring, Ebner-Priemer, Koutsouleris, Riper, Mouchabac, Torous and Cipriani2023).

Collaborating with people who have lived experience can help address concerns around stigma, disempowerment, and access, while also enhancing agency and self-monitoring (Patrickson et al. Reference Patrickson, Musker, Thorpe, van Kasteren and Bidargaddi2023). Nonetheless, successful adoption is influenced by practical factors including IT infrastructure, staff capacity, training, and concerns about how technology may affect therapeutic relationships (Pithara et al. Reference Pithara, Farr, Sullivan, Edwards, Hall, Gadd, Walker, Hebden and Horwood2020).

Findings from our study reflect the tension between innovation and inclusion, emphasising the importance of participatory approaches that are sensitive to the complex contexts in which digital tools are implemented.

Of course, any advance in MHT must occur alongside the Irish Digital for Care 2030 framework and the long-overdue implementation of the national electronic health record system in Ireland, which according to the European Union, must be accessible to all citizens by 2030 (eMHIC, 2024, EU, 2024, HSE, 2024, 2025a). To ensure that digital interventions are both practical and equitable, we recommend (1) targeted digital literacy initiatives, especially for older service users; (2) regulatory frameworks that ensure privacy, transparency, and clinical validation; and (3) the incorporation of service user perspectives into the design and implementation of MHT tools.

Conclusions

This study underscores both the promise and complexity of integrating technology into mental health care. Digital tools have the potential to improve access and complement traditional services, but key challenges, particularly around regulation, privacy, and proven effectiveness, remain. Future efforts should prioritise robust evaluation frameworks, comprehensive education and guidance for users and providers, and ethical, evidence-based implementation, especially when supporting vulnerable populations (Kelly, Reference Kelly2024, McCradden et al. Reference McCradden, Hui and Buchman2023, Redahan & Kelly, Reference Redahan and Kelly2024).

Our findings also reveal a clear age divide, with younger users demonstrating greater comfort and familiarity with mental health technologies. These results emphasise the importance of targeted education and training to ensure that technological interventions are equitably and effectively integrated into routine psychiatric practice.

Alongside the need for robust evidence demonstrating the efficacy of these novel MHT approaches, the challenge ahead lies in striking a balance between innovation and trust, ensuring that technological advancements genuinely serve and support mental health service users.

Limitations

This survey did not permit the calculation of response rate and may not be fully representative of all service users in Ireland. Convenience sampling was used to select participants for this survey, which may have introduced selection bias into the pool of respondents.

Exploration of attitudinal variations according to demographics and diagnoses would be interesting, but subgroup analyses lack sufficient power to derive meaningful interpretations.

Participants were recruited from community mental health teams in the Community Healthcare Organisation 7 area. The teams that participated in this survey are located in the Dublin South Central Community Mental Health Service. These public teams predominantly serve urban areas. It would be beneficial to replicate this study in both rural and private settings to allow for further generalisation of results.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2026.10170.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the participants.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

JRK is the principal investigator (Ireland) on COMPASS, GH, and Transcend Therapeutics-sponsored clinical trials in Dublin, Ireland. JRK has consulted for Clerkenwell Health, and JRK and AH have received grant funding from the Health Research Board (ILP-POR-2022-030, DIFA-2023-005, HRB KTA-2024-002).

Ethical standards

Tallaght University Hospital/St. James’s Hospital Joint Research Ethics Committee approved this study (Project ID:3669). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.