1. Introduction

In Sevillian Spanish, clusters consisting of orthographic 〈s〉 plus voiceless stop undergo several changes, including metathesis. Coda /s/ reduces to [h] (debuccalisation), producing h–stop sequences, and [h] metathesises with the adjacent stop, producing stop–h sequences as in (1) (Torreira Reference Torreira, Sagarra and Toribio2006; O’Neill Reference O’Neill2010; Parrell Reference Parrell2012; Torreira Reference Torreira2012; Ruch & Harrington Reference Ruch and Harrington2014; Ruch & Peters Reference Ruch and Peters2016; Henriksen et al. Reference Henriksen, Galvano and Fischer2023).

Metathesis is an ongoing change in the variety and can occur in all /s/–voiceless stop sequences. It occurs in all stress configurations (Ruch Reference Ruch2008; Torreira Reference Torreira2012; Horn Reference Horn2013) and both within morphemes and across word and morpheme boundaries (Ruch Reference Ruch2008; Horn Reference Horn2013). The realisation of 〈s〉–voiceless stop sequences is highly variable, and metathesis is only one possible variant in Sevillian (see §2.1).

Metathesis raises the following question: are the syllables /s/ metathesises out of heavy or light? The answer sheds light on the representation of these sequences and on the structure of the phonological grammar. Metathesis in /sC/ sequences could produce a mismatch between segmental order and syllable structure at different levels of representation or derivational stages. This mismatch permits us to disentangle surface forms from non-surface forms by designing experiments in which listeners’ responses can be explained by reference to one – but not another – level of representation. More broadly, the mismatch creates an opportunity to investigate the separation between components of the phonological grammar and the role of abstraction.

The possibility that syllable structure may differ in surface and non-surface forms arises because surface stop–h sequences are representationally ambiguous, as outlined in (2). On one hand, stop–h sequences could be realisations of a new aspirated stop category, as in (2a) (O’Neill Reference O’Neill2009; Gylfadottir Reference Gylfadottir2015). They look quite similar to aspirated stops in languages like English and German, at least on the surface. Under this conceptualisation, the syllable preceding the stop has no coda and is light at all levels of representation. On the other hand, stop–h sequences may still be realisations of /sC/ sequences (as they have been diachronically), derived by metathesis as in (2b). Under this analysis, segmental order and syllable structure may differ in non-surface and surface forms. At some non-surface representational or derivational level (depending on the style of analysis), /s/ syllabifies as a coda, creating a heavy syllable. On the surface, however, /s/ (realised as [h]) is no longer in that syllable because of metathesis. The resulting stop–h sequence is the onset to the following syllable, leaving the first syllable light (see §4.6.2 for further discussion of resyllabification).

Most existing research treats stop–h sequences as deriving from /sC/ sequences that undergo metathesis, as in (2b) (e.g., Torreira Reference Torreira, Sagarra and Toribio2006; Parrell Reference Parrell2012; Torreira Reference Torreira2012; Ruch Reference Ruch2013; Cronenberg et al. Reference Cronenberg, Gubian, Harrington and Ruch2020). This treatment is supported by results from a behavioural experiment in which Sevillian listeners treat stop–h sequences as realisations of underlying /sC/ clusters: they interpret [h] in word-initial stop–h sequences as /s/ on the preceding word (Gilbert Reference Gilbert2023). The abstract representation does not seem to have changed (/sC/), despite changes in pronunciation towards metathesis ([Ch]).

The current article tests the weight of syllables preceding stop–h sequences by investigating how they interact with stress. Spanish stress shows weight-sensitive restrictions, one of which is that antepenultimate stress does not occur in words with heavy penults (Harris Reference Harris1983; Roca Reference Roca1991). Given that stop–h sequences may arise from /sC/ sequences and involve a change in syllable structure, listeners could treat words with antepenultimate stress where /s/ has metathesised out of the penult differently from words with simple CV penults (![]() vs.

vs. ![]() ). Although they have the same weight profile on the surface (LLL), they may differ at non-surface levels of representation.Footnote

1

). Although they have the same weight profile on the surface (LLL), they may differ at non-surface levels of representation.Footnote

1

The current article has two goals. The first goal is experimental. I present results from a forced-choice stress acceptability task designed to test the weight of syllables that have undergone metathesis (syllables where /s/ has metathesised out). In the task, listeners compare nonce words with antepenultimate stress that have penults of different shapes. The results suggest that listeners strongly prefer words with CV penults over words where /s/ has metathesised out of the penult, and over words with unambiguously heavy penults. A plausible interpretation is that (a) there is a mismatch between the surface form [Ch] and underlying form /sC/ and (b) stress is evaluated on a non-surface form that has a heavy penult. I also discuss (in §4.6) other possible interpretations of why these syllables may be treated as heavy.

The second goal is theoretical. Starting from the assumption that stop–h sequences derive from /sC/ clusters, I explore what kinds of theoretical frameworks can account for the interaction between stress and metathesis in Sevillian. The results from the experiment do not distinguish between several possible analyses, so I sketch analyses in two categories. Process-interaction analyses treat the Sevillian pattern as resulting from the interaction of two phonological processes: stress assignment and metathesis. The interaction is opaque because stress is constrained by structure not visible on the surface. More specifically, it falls into the category of countershifting opacity (Rasin Reference Rasin2022). If future research supports these analyses, the experimental results are interesting because they document productive opacity in an experimental setting (contra, e.g., Sanders Reference Sanders2003). Process interaction analyses need to be either serial or rule-based in order to account for the pattern. Representational analyses treat stress and metathesis as processes that differ in kind, and are relegated to different representational levels of the phonological grammar, such that they do not interact. Representational analyses can take many forms as long as the two processes are separated. I explore a system in which stress operates on layers of representation that include different kinds of timing and gestural information.

This article is organised as follows. §2 provides more information on /sC/ variants and metathesis in Sevillian Spanish, Spanish stress, metathesis and syllable structure, and experimental approaches to weight sensitivity in Spanish. §3 describes the stimuli for the main experiment and presents results from small production and perception studies to verify their acoustic properties. §4 presents the main experiment and several possible interpretations of the results. §5 sketches various theoretical analyses that could account for the interaction. §6 concludes.

2. Background

2.1. Spanish coda /s/ and Sevillian metathesis

The production of coda /s/ is variable throughout the Spanish-speaking world. From a categorical perspective, common realisations include the unreduced variant [s], debuccalisation to [h] and deletion to [

![]() $\varnothing $

] (e.g., Cedergren Reference Cedergren1973; Terrell Reference Terrell1979; Lipski Reference Lipski1986, Reference Lipski1994). These variants are often conceived of as forming part of a reduction continuum, from less to more reduced, as in (3) (e.g., Ferguson Reference Ferguson, Croft, Denning and Kemmer1990; Mason Reference Mason1994).

$\varnothing $

] (e.g., Cedergren Reference Cedergren1973; Terrell Reference Terrell1979; Lipski Reference Lipski1986, Reference Lipski1994). These variants are often conceived of as forming part of a reduction continuum, from less to more reduced, as in (3) (e.g., Ferguson Reference Ferguson, Croft, Denning and Kemmer1990; Mason Reference Mason1994).

Coda /s/ reduction has operated diachronically in the development from Latin to Spanish and other Romance languages, and is often considered to be a reflex of a general pressure against coda consonants (Alonso Reference Alonso1945; Malmberg Reference Malmberg1965; Mason Reference Mason1994). Coda reduction is often treated as progressive feature loss: reduction occurs by loss of oral features ([s] → [h]) followed by loss of laryngeal features ([h] → [

![]() $\varnothing $

]; Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith, Cressey and Napoli1981; Hualde Reference Hualde, Kirschner and DeCesaris1989a; McCarthy Reference McCarthy2008b). However, recent studies show that /s/ reduces more gradiently than can be captured by discrete allophonic categories (e.g., File-Muriel & Brown Reference File-Muriel and Brown2011; Erker Reference Erker2012; Henriksen & Harper Reference Henriksen and Harper2016).

$\varnothing $

]; Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith, Cressey and Napoli1981; Hualde Reference Hualde, Kirschner and DeCesaris1989a; McCarthy Reference McCarthy2008b). However, recent studies show that /s/ reduces more gradiently than can be captured by discrete allophonic categories (e.g., File-Muriel & Brown Reference File-Muriel and Brown2011; Erker Reference Erker2012; Henriksen & Harper Reference Henriksen and Harper2016).

Coda /s/ variants are in synchronic variation in all varieties of Spanish, and varieties differ as to which realisations are most common. Common factors that condition this variation include speech rate, speech style, morphological and phonological context, and speaker demographics (see Erker Reference Erker2012: 11–20 for a thorough overview). Despite high synchronic variation, coda /s/ realisations seem to be stable in most communities (Labov Reference Labov1994: 583–585). It is possible that coda /s/ is undergoing change, as has historically occurred, but at a rate not visible in synchronic variation patterns (Mason Reference Mason1994: 72–76).

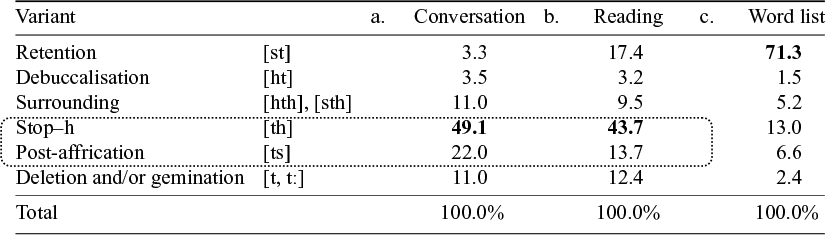

Sevillian Spanish has the variants just described plus several others, including metathesis. Ruch (Reference Ruch2008) reports rates of variants of /st/ sequences in production data from 53 Sevillian speakers in several speech styles, shown in Table 1. Based on impressionistic classification, she finds variants where /s/ remains in its original location ([st], [ht]); variants with segmental metathesis ([th], [ts]); variants where /s/ is phonetically split around /t/ ([hth], [sth]); and variants with /s/ deletion accompanied by variable lengthening of /t/ (![]() ). Note the two possible results of metathesis for /st/ sequences: [th] (post-aspiration; stop–h in my terminology) and [ts] (post-affrication in the terminology of Ruch Reference Ruch2008).

). Note the two possible results of metathesis for /st/ sequences: [th] (post-aspiration; stop–h in my terminology) and [ts] (post-affrication in the terminology of Ruch Reference Ruch2008).

Table 1 Rates of /st/ variants in Sevillian Spanish (Ruch Reference Ruch2008). The most frequent realisation for each speech style is bolded.

In conversational speech (column (a) of Table 1), /st/ is realised as metathesised ([th] or [ts]) in over 70% of forms. Other forms, including the pan-Hispanic standard ([s] retention) and non-standard reductions common in other Spanish varieties (debuccalisation and deletion), are comparatively infrequent. In read speech (column (b)), metathesised realisations constitute over 55% of forms, but the proportion of standard [s] realisations increases. Only in the most careful speech, word list reading (column (c)), are metathesised forms less frequent than non-metathesised ones. Even in that style, the categories with metathesis are the largest after [s] retention. I am unaware of any existing study that presents rates of variants for /sp/ and /sk/ sequences, although phonetic studies show that these sequences also undergo metathesis (e.g., Ruch & Peters Reference Ruch and Peters2016; Henriksen et al. Reference Henriksen, Galvano and Fischer2023).

These variants are undergoing change in Andalusian Spanish varieties. From both categorical and gradient perspectives, metathesis is advanced in Sevillian Spanish, and most advanced among younger speakers (Ruch Reference Ruch2008; Ruch & Peters Reference Ruch and Peters2016). Patterns of stratification by speech style, speaker age and level of education suggest that the stop–h variant is well-established in Seville and may be a regional standard. In contrast, post-affrication is a newer change. It has received scholarly attention only since the early 2000s (Moya Corral Reference Moya Corral2007; Ruch Reference Ruch2008; Vida-Castro Reference Vida-Castro2016, Reference Vida-Castro2022; Del Saz Reference Del Saz, Calhoun, Escudero, Tabain and Warren2019a; Moya Corral & Tejada Giráldez Reference Moya Corral, de la Sierra and Giráldez2020). Vida-Castro's (Reference Vida-Castro2022) comparison of recordings from 1995 and 2015 indicates that post-affrication has increased quickly in Western Andalusia and may carry covert prestige (Ruch Reference Ruch2008; Vida-Castro Reference Vida-Castro2016, Reference Vida-Castro2022).

The diachronic progression of this series of processes appears to have gone as follows: coda /s/ weakening/debuccalisation (plus lengthening of the following consonant) came first, followed by metathesis. For sequences where the second consonant is /t/, there is a further step: post-affrication (Ruch Reference Ruch2008: 69; Vida-Castro Reference Vida-Castro2016; Del Saz Reference Del Saz2019b; Moya Corral & Tejada Giráldez Reference Moya Corral, de la Sierra and Giráldez2020).Footnote 2 It is crucial that debuccalisation appears to have preceded metathesis, because debuccalisation may be a necessary precursor for articulatory and perceptual reasons (see §5.1.4). Although metathesis is not new (Moya Corral & Tejada Giráldez Reference Moya Corral, de la Sierra and Giráldez2020 find evidence of sporadic metathesis in a linguistic atlas from the 1960s), coda /s/ weakening occurs in all parts of the Spanish-speaking world and is older, dating from at least the 16th century (Romero Reference Romero1995a: 192–193). It is not clear whether metathesis is part of the cline of coda reduction or whether it is motivated by the same factors. One proposal is that it is, and that it is a good solution to the pressure against coda consonants: it removes /s/ from coda position while maintaining some of its features (Ruch Reference Ruch2008; Vida-Castro Reference Vida-Castro2016, Reference Vida-Castro2022; Moya Corral & Tejada Giráldez Reference Moya Corral, de la Sierra and Giráldez2020). However, this proposal is not obviously well supported, especially given that coda reduction and metathesis are often accompanied by lengthening of the stop closure, which can be interpreted as maintenance of the coda timing slot.Footnote 3

My experimental stimuli use stop–h forms for consistency across /sp, st, sk/ sequences (only /st/ has a post-affricated variant). Furthermore, while both both stop–h and post-affricated variants are common for /st/, [ts] sequences appear to carry more social meaning (and possibly stigma). Stop–h sequences are recognisable as Sevillian (Ruch Reference Ruch2018), but are standard enough to avoid attracting excessive attention in an experimental setting.

2.2. Spanish stress

In non-verbs, Spanish stress is uncontroversially contrastive and controversially weight sensitive. Primary stress falls in a right-aligned three-syllable window and can be penultimate (as in ![]() ‘hip’), antepenultimate (

‘hip’), antepenultimate (![]() ‘Saturday’) or final (

‘Saturday’) or final (![]() ‘hummingbird’). Penultimate stress is by far the most common; antepenultimate stress is infrequent. Bárkányi (Reference Bárkányi2002) presents a study of stress patterns in non-verbs based on the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española. Based on my own calculations from her numbers, 9% of nouns have antepenultimate stress, 75% have penultimate stress and 15% have final stress (roughly similar to my calculations based on numbers reported by Morales-Front Reference Morales-Front, Núñez-Cedeño, Colina and Bradley2014: 244).

‘hummingbird’). Penultimate stress is by far the most common; antepenultimate stress is infrequent. Bárkányi (Reference Bárkányi2002) presents a study of stress patterns in non-verbs based on the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española. Based on my own calculations from her numbers, 9% of nouns have antepenultimate stress, 75% have penultimate stress and 15% have final stress (roughly similar to my calculations based on numbers reported by Morales-Front Reference Morales-Front, Núñez-Cedeño, Colina and Bradley2014: 244).

Stress is usually taken to be lexically marked in non-verbs, where it can be contrastive (e.g., ![]() ‘bed sheet’ vs.

‘bed sheet’ vs. ![]() ‘savannah’; Harris Reference Harris1983, Reference Harris1991). However, several restrictions also suggest weight sensitivity. For example, words with final stress largely end in consonants (Harris Reference Harris1983, Reference Harris1991; Roca Reference Roca1991), and words ending in a consonant restrict the stress window to the final two syllables (Harris Reference Harris1992: 7). The crucial weight-related restriction for the current experiment is stated in (4):

‘savannah’; Harris Reference Harris1983, Reference Harris1991). However, several restrictions also suggest weight sensitivity. For example, words with final stress largely end in consonants (Harris Reference Harris1983, Reference Harris1991; Roca Reference Roca1991), and words ending in a consonant restrict the stress window to the final two syllables (Harris Reference Harris1992: 7). The crucial weight-related restriction for the current experiment is stated in (4):

The *ĹHσ restriction captures the fact that a heavy penult or ultima narrows the stress window to the final two syllables. There are exceptions, but these tend to be place names or loanwords (e.g., Mánchester, Ámsterdam; Roca Reference Roca1990), which arguably do not result from the language’s productive grammar.Footnote 4

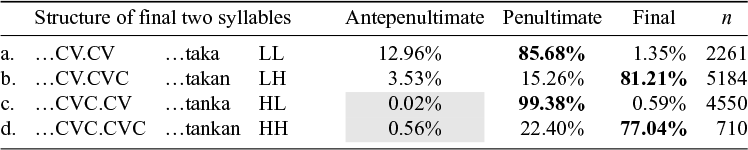

The *ĹHσ restriction is evident in corpus studies of the Spanish lexicon. Bárkányi (Reference Bárkányi2002) finds several relevant generalisations about non-verbs, shown in Table 2. First, when the final two syllables are light, the most frequent stress location is penultimate (row (a) of Table 2). Second, when either the penult or ultima is heavy but the other is light, the heavy one is usually stressed (rows (b) and (c)).

Table 2 Stress patterns in Spanish by syllable type (adapted from Bárkányi Reference Bárkányi2002: 383). The highest percentage in each row is shown in bold.

Although antepenultimate stress is infrequent overall, its frequency depends on the weight of the final three syllables. Table 2 shows that words ending in two light syllables, LL, have the highest percentage of antepenultimate stress (12.96%). Words with a heavy penult or ultima (or both) very rarely have antepenultimate stress (never constituting more than 4% of words with the given shape). Most importantly, words with heavy penults rarely have antepenultimate stress: the antepenult is stressed in only 0.02% of words ending in HL, and 0.56% of words ending in HH (the grey-shaded cells in Table 2). Fuchs (Reference Fuchs2018: 9) finds no such words in the written texts in EsPal, a corpus containing over 300 million word tokens (Duchon et al. Reference Duchon, Perea, Sebastián-Gallés, Martí and Carreiras2013).Footnote 5 In short, a heavy penult almost always prevents antepenultimate stress.

While some theoretical proposals for Spanish argue against weight-sensitivity (e.g., Roca Reference Roca1990, Reference Roca1991 et seq.; Baković Reference Baković2016; Piñeros Reference Piñeros and Núñez-Cedeño2016), there is evidence that speakers apply weight-sensitivity in experiments (see §2.4).

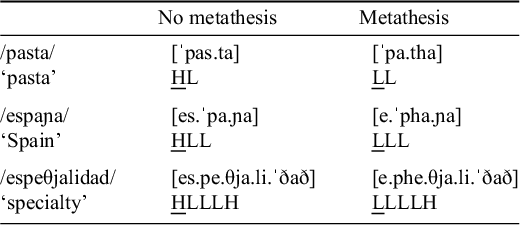

2.3. Metathesis changes syllable structure

Under the assumptions that (a) Spanish stress is weight-sensitive, and (b) Sevillian stop–h sequences are realisations of abstract /sC/ sequences, stress and metathesis could interact as illustrated in Table 3. When metathesis does not occur, /s/ is syllabified as a coda, which creates a heavy syllable. When metathesis does occur, it moves /s/ (debuccalised to [h]) to after the initial consonant of the next syllable, and the sequence syllabifies as an onset. The preceding syllable is light.

Table 3 Metathesis changes surface syllable structure.

If metathesis changes syllable structure, it potentially creates a mismatch between surface-visible structure and non-surface structure upon which stress operates. Stress could be conditioned by the phonetic structure visible on the surface, or by structure that is present only at a non-surface level. Given that antepenultimate stress is blocked in words with heavy penultimate syllables, listeners should disprefer words with antepenultimate stress that have heavy penults at both surface and non-surface levels (e.g., */ˈpa.tan.ka/, *[ˈpa.taŋ.ka]). This should hold regardless of which level of representation their decision is based on.

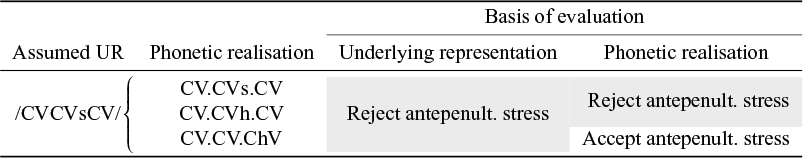

Table 4 illustrates possible decisions listeners could make for words with metathesis. Listeners might accept words with antepenultimate stress when /s/ has metathesised out of the penultimate syllable. This would suggest that they treat the penult as light, evaluating stress on the surface form where the penult has no coda. Or, listeners might disprefer words with antepenultimate stress and these kinds of penults, just like other penults closed with a consonant -- [s], [h] or any other. This would suggest that they treat the penult as heavy, evaluating stress on a structure not visible on the surface, where /s/ is still in coda position.

Table 4 Possibilities for stress judgements in words with metathesis.

An alternative explanation for why penults might be treated as heavy is that metathesis does not really change syllable structure; §4.6.2 argues against this possibility.

2.4. Perception of stress in Spanish

Recent research argues that weight sensitivity is an active restriction in Spanish, and that it affects participants’ production and acceptance of stress patterns. Participants apply weight sensitivity to nonce words and are sensitive to stress–weight configurations that violate restrictions (Shelton Reference Shelton2007, Reference Shelton2013; Shelton et al. Reference Shelton, Gerfen, Palma, Masullo, O’Rourke and Huang2009, Reference Shelton, Gerfen and Palma2012; Shelton & Grant Reference Shelton and Grant2018; Fuchs Reference Fuchs2018).

For example, Shelton (Reference Shelton2007) finds that Spanish speakers are sensitive to unattested combinations of stress location and heavy syllables. He asked Spanish-speaking participants to read aloud nonce words with antepenultimate or penultimate stress, and different kinds of penults. He tested words that (a) are phonotactically illicit or (b) are phonotactically licit in the synchronic system, but are absent for historical reasons. Participants made more mistakes with phonotactically illicit words (e.g., dóvalda, with antepenultimate stress and heavy penult) than with phonotactically licit words (e.g., dóvasa, with antepenultimate stress and light penult; doválda, with penultimate stress and heavy penult). For words that are phonotactically licit but absent for historical reasons, Shelton (Reference Shelton2007) used nonce words with palatal onsets in the final syllable (e.g., dovaña). These words should allow antepenultimate stress because all syllables are light.Footnote 6 In the experiment, participants produced words with final palatal onsets with error rates between those for phonotactically licit and illicit nonce words. Shelton (Reference Shelton2007: 101) suggests that speakers are ‘differentially sensitive to what is… theoretically prohibited by the synchronic grammar as well as to structures that are absent for historical reasons’. Weight restrictions in the synchronic grammar play a role in participants’ stress judgements. See also Fuchs (Reference Fuchs2018) for a study on how Spanish speakers treat words that should permit antepenultimate stress synchronically, but do not for diachronic reasons.

Garcia (Reference Garcia2019) targets the distinction between analogy and syllable weight in Brazilian Portuguese, a closely related language with stress patterns similar to Spanish. In a prior lexicon study, Garcia (Reference Garcia2017: 68) found that antepenultimate stress is more likely in words with light antepenults than in those with heavy antepenults. In his subsequent study, Garcia (Reference Garcia2019: 616) found that LLL words are more likely to bear antepenultimate stress (24% of LLL words) than HLL words (21% of HLL words). This finding is unnatural from the perspective of weight sensitivity, since heavy syllables typically attract stress.

Garcia’s (Reference Garcia2019) speakers did not generalise this unnatural pattern to nonce words in an experimental setting. His participants compared words with identical segmental material that had penultimate or antepenultimate stress (e.g., prísbade vs. prisbáde). The words had weight profiles LLL, HLL, LHL and LLH. Participants chose penultimate stress more than antepenultimate stress only for LHL words. For LLL, HLL and LLH words, listeners chose antepenultimate stress more than penultimate stress. The crucial result is that antepenultimate stress is chosen at a higher rate in HLL words than in LLL words: stress is ‘attracted’ to the antepenultimate syllable in HLL words (presumably because it is heavy). This behaviour goes against the lexical statistics above, where LLL words are more likely to have antepenultimate stress than HLL words. It also goes against the pattern observed for the subset of trisyllabic words in the lexicon, where most of the words that have antepenultimate stress are LLL (71%), and many fewer are HLL (29%) (Garcia Reference Garcia2019: 629). If participants’ choices were based on reference to existing forms, they would be expected to choose the antepenultimate stress version at higher rates in LLL words than in HLL words. Instead, participants applied a more natural pattern of weight sensitivity, with the heavy syllable attracting stress, despite the conflicting pattern in the lexicon.

Finally, Fuchs (Reference Fuchs2018) found that Spanish speakers apply weight sensitivity restrictions to nonce words in a stress judgement task. The nonce words had light penults (e.g., ![]() ) or heavy penults of various types (e.g.,

) or heavy penults of various types (e.g., ![]() ), and each word was presented in written form with both penultimate and antepenultimate stress. Participants gave higher ratings to words with penultimate stress than to those with antepenultimate stress in all of the syllable structure conditions (e.g.,

), and each word was presented in written form with both penultimate and antepenultimate stress. Participants gave higher ratings to words with penultimate stress than to those with antepenultimate stress in all of the syllable structure conditions (e.g., ![]() >

> ![]() ). Among words with penultimate stress, words with heavy and light penults received similar ratings. However, among words with antepenultimate stress, words with heavy penults received significantly lower ratings than those with light penults (

). Among words with penultimate stress, words with heavy and light penults received similar ratings. However, among words with antepenultimate stress, words with heavy penults received significantly lower ratings than those with light penults (![]()

![]() $\gg $

$\gg $

![]() ). This suggests that the restriction against antepenultimate stress when the penult is heavy is active in Spanish speakers’ synchronic grammars, and is applied productively to nonce words: heavy penults make antepenultimate stress worse.Footnote

7

). This suggests that the restriction against antepenultimate stress when the penult is heavy is active in Spanish speakers’ synchronic grammars, and is applied productively to nonce words: heavy penults make antepenultimate stress worse.Footnote

7

My experiment, described in the next section, builds on Fuchs’s (Reference Fuchs2018) findings and (partially) on his methodology, applying them to Sevillian Spanish words with syllables whose codas have metathesised out.

3. Experimental setup

The main research question is as follows: Do Sevillian listeners treat syllables where /s/ has metathesised out as heavy or light? The experiment uses the interaction of metathesis with stress to test this. Metathesis creates a possible mismatch between syllable weight at surface and non-surface levels. Stress could operate on either level, and listeners’ responses to words with metathesis make clear which.

In the main experiment, listeners heard pairs of nonce words with antepenultimate stress that differed only in the type of penult. This section describes the stimulus words for the main experiment (§3.1), and presents acoustic and perceptual studies of them in order to ensure that they were produced, and are perceived, with stress in the intended location (§§3.3 and 3.4). Most of the stimuli nonce words are phonotactically illicit in Spanish (having antepenultimate stress and a heavy penult), and could have been difficult for a native speaker to produce. The results presented in this section show that the acoustic cues to stress are present on antepenultimate vowels in the stimulus words, and that Spanish speakers perceive stress in the intended (antepenultimate) location.

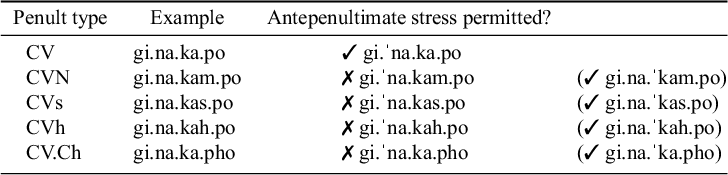

3.1. Stimuli for the main experiment

The nonce words for the main experiment have four syllables and antepenultimate stress. The onsets to the final syllable were /p, t, k/ (which can host metathesised [h]); the vowels in the antepenultimate and penultimate syllables were /a, i, u/. In a given word, the same vowel was used in both the antepenultimate and penultimate syllables (e.g., ![]() ) to avoid the possibility that listeners’ choices were based on the ability of a particular vowel to bear stress.Footnote

8

) to avoid the possibility that listeners’ choices were based on the ability of a particular vowel to bear stress.Footnote

8

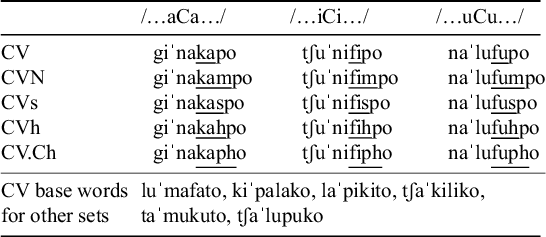

The nonce words were designed in sets. Table 5 shows the three sets with final onset /p/ as an example. Each column is a set, and members of each set differ only in the type of penult: CV (no coda), CVN (coda sonorant), CVs (coda [s]), CVh (coda [h]) and CV.Ch (metathesised [h]). There were 45 test nonce words (9 words

![]() $\times $

5 penult types). The CV forms of the other sets are listed at the bottom of Table 5.

$\times $

5 penult types). The CV forms of the other sets are listed at the bottom of Table 5.

Table 5 Three of the word sets (/a, i, u/ with final onset /p/) used as stimuli for the stress judgement task.

Thirty-six filler words were also included (four filler words in each of the nine sets). The filler conditions involved changes that should not affect stress judgements. Two fillers in each set differed minimally from the CV word by (a) changing the onset of the final syllable from a stop to a nasal (![]() →

→ ![]() ) and (b) changing the voicing, continuancy, nasality or rhoticity/laterality of the first consonant (

) and (b) changing the voicing, continuancy, nasality or rhoticity/laterality of the first consonant (![]() →

→ ![]() ). Another two fillers in each set differed minimally from the CV.Ch word by (a) changing the original voiceless stop in the final onset to a different voiceless stop (

). Another two fillers in each set differed minimally from the CV.Ch word by (a) changing the original voiceless stop in the final onset to a different voiceless stop (![]() →

→ ![]() ) and (b) changing the first consonant (

) and (b) changing the first consonant (![]() →

→ ![]() ).

).

The nonce words were recorded by a linguistically trained male native speaker of Sevillian Spanish in his late 20s. The recording was done in a quiet room with a Zoom H4N Pro recorder. The speaker was instructed to produce all words with antepenultimate stress and different variants of coda /s/ ([s], [h], [Ch]). Although words with this combination of stress and syllable structure do not exist in Spanish, he produced them easily, as verified in the following acoustic analysis and stimulus verification perception study.

Because antepenultimate stress is marked, listeners might be more willing to accept it on nonce words that are more similar to existing words with antepenultimate stress. I controlled for neighbourhood density based on the CV forms using Levenshtein distance, which is the edit distance to turn one string into another. Calculations were based on orthography.Footnote 9

First, I created a subset of four-syllable words with antepenultimate stress from SUBTLEX-ESP, a 41-million-word Spanish corpus based on film subtitles (Cuetos et al. Reference Cuetos, Glez-Nosti, Barbón and Brysbaert2012). Then, I calculated the Levenshtein distance between each CV nonce word candidate and each word in the corpus subset (using the stringdist package for R; van der Loo Reference van der Loo2014). Levenshtein distance is a rough measure of neighbourhood density, but has been found to explain much of listeners’ judgements of word similarity (Vitevitch & Luce Reference Vitevitch and Luce2016: 78).

For the experimental items, I chose CV nonce words that had no lexical neighbours at a Levenshtein distance of three or less, and no more than five neighbours at a distance of four. The goal was to use nonce words that are similar – but not too similar – to real words. Dautriche (Reference Dautriche2017: fn. 13) suggests that word confusability effects tail off after an edit distance of one to two, so words at a distance of three should be similarly susceptible to effects – or lack thereof – of lexical neighbours. The rest of the words in each set were built from these words with CV penults.

3.2. Statistical modelling

Data analysis for the preliminary production and perception experiments, as well as for the main perception experiment, was run in R (v. 4.1.3; R Core Team 2022). Models were run using lme4 (v. 1.1.27.1; Bates et al. Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015) and lmerTest (v. 3.1.3; Kuznetsova et al. Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017). Post-hoc tests were done with emmeans, with Tukey adjustments for multiple comparisons (v. 1.6.2-1; Lenth Reference Lenth2020). Further details about the models are included in the relevant sections.

3.3. Acoustic analysis of stimuli: stress

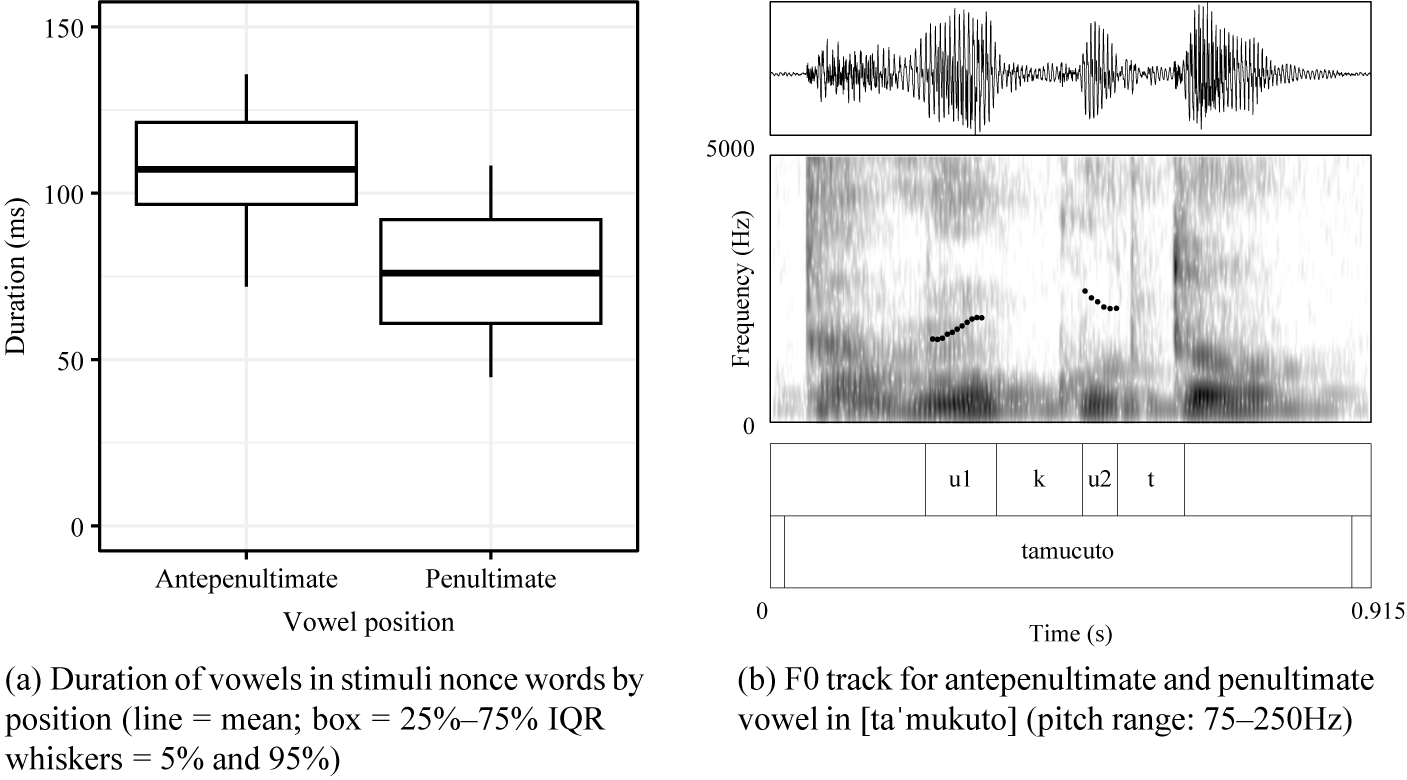

Although antepenultimate stress on words with heavy penults is rare in Spanish, an acoustic analysis suggests that the stimuli created for this study do indeed have antepenultimate stress. Spanish primary stress is realised acoustically with a combination of f0, duration, and intensity (Llisteri et al. Reference Llisteri, Machuca, de la Mota, Riera and Ríos2003; Ortega-Llebaria & Prieto Reference Ortega-Llebaria and Prieto2010). Stressed vowels are longer and have slightly higher intensity, but intensity is a weak and inconsistent correlate (Ortega-Llebaria & Prieto Reference Ortega-Llebaria and Prieto2010). In Castilian Spanish (North-Central Spain), stressed syllables have a rising pitch contour (Ortega-Llebaria & Prieto Reference Ortega-Llebaria and Prieto2010; Vogel et al. Reference Vogel, Anthanasopoulou, Pincus and Heinz2016) that peaks on the following syllable (Ortega-Llebaria & Prieto Reference Ortega-Llebaria and Prieto2010). I have not found studies of Sevillian intonation, but rising contours on stressed syllables are reported for nearby varieties (Henriksen & García-Amaya Reference Henriksen and García-Amaya2012).

The stimulus words show acoustic evidence of stress on the antepenultimate vowel, as intended; this is illustrated in Figure 1. This acoustic analysis compares antepenultimate vowels (intended to be stressed, as in ![]() ) to penultimate vowels (intended to be unstressed, as in

) to penultimate vowels (intended to be unstressed, as in ![]() ). Figure 1a shows that antepenultimate vowels are longer than penultimate vowels. Figure 1b shows an example of an F0 contour on antepenultimate and penultimate vowels. The antepenultimate vowel, labelled u1, has rising F0 that peaks on the following (penultimate, unstressed) vowel. The penultimate vowel, u2, has falling F0. In other stimulus words, the contours are flatter, but mostly fall slightly because of the early peak from the preceding stressed vowel. What is crucial is that the contour differs substantially from the rising contour on stressed vowels. Antepenultimate and penultimate vowels do not differ in intensity.

). Figure 1a shows that antepenultimate vowels are longer than penultimate vowels. Figure 1b shows an example of an F0 contour on antepenultimate and penultimate vowels. The antepenultimate vowel, labelled u1, has rising F0 that peaks on the following (penultimate, unstressed) vowel. The penultimate vowel, u2, has falling F0. In other stimulus words, the contours are flatter, but mostly fall slightly because of the early peak from the preceding stressed vowel. What is crucial is that the contour differs substantially from the rising contour on stressed vowels. Antepenultimate and penultimate vowels do not differ in intensity.

Figure 1 Acoustic evidence of antepenultimate stress in recorded stimuli.

Linear regression models support these observations. The duration and intensity models contain fixed effects of word condition (CV, CVN, CVs, CVh and CV.Ch), vowel position (antepenultimate, penultimate), and their interaction. Penultimate vowels are shorter than antepenultimate vowels (

![]() $\beta = -0.031$

,

$\beta = -0.031$

,

![]() $p < 0.01$

). Neither word condition nor the interaction between vowel position and word condition is significant. The difference in duration holds across conditions. This is important because it suggests that penultimate vowels are not shorter simply because many of them come from syllables with a coda consonant, while antepenultimate vowels all come from open syllables. Penultimate vowels are shorter than antepenultimate vowels even in words with CV penults.Footnote

10

The intensity model had no significant effects.

$p < 0.01$

). Neither word condition nor the interaction between vowel position and word condition is significant. The difference in duration holds across conditions. This is important because it suggests that penultimate vowels are not shorter simply because many of them come from syllables with a coda consonant, while antepenultimate vowels all come from open syllables. Penultimate vowels are shorter than antepenultimate vowels even in words with CV penults.Footnote

10

The intensity model had no significant effects.

For F0, measurements were taken at four points during each vowel (20 ms, 30 ms, 40 ms, 50 ms). For antepenultimate vowels, the maximum F0 on the following (penultimate) vowel was also taken, in order to capture the expected peak on the syllable following primary stress. Each vowel (/a, i, u/) was modelled separately in each position (antepenultimate, penultimate). The models had a fixed effect of measurement location. Results reported are from models and post-hoc tests with emmeans. For antepenultimate vowels (all qualities), the maximum F0 on the following vowel is higher than F0 at all locations within the antepenultimate vowel (

![]() $p < 0.001$

for /a, i, u/). Although the F0 rise within the antepenultimate vowel is not significant, manual inspection shows that many of these vowels show a rise even within that vowel, as in Figure 1b. For penultimate vowels, measurement location was not a significant predictor of F0, but a slight fall is visible in many of the words. This may be because the first measurement point was 20 ms into the vowel, failing to capture the full extent of the fall.

$p < 0.001$

for /a, i, u/). Although the F0 rise within the antepenultimate vowel is not significant, manual inspection shows that many of these vowels show a rise even within that vowel, as in Figure 1b. For penultimate vowels, measurement location was not a significant predictor of F0, but a slight fall is visible in many of the words. This may be because the first measurement point was 20 ms into the vowel, failing to capture the full extent of the fall.

In sum, the antepenultimate vowels in my stimuli carry the acoustic correlates of stress: they are longer than unstressed vowels of the same quality, and have rising F0 contours with a peak on the following syllable. That stress is not reflected in intensity is not surprising, since intensity effects in Spanish stress are small, inconsistently produced and inconsistently used to identify stress (Llisteri et al. Reference Llisteri, Machuca, de la Mota, Riera and Ríos2003; Ortega-Llebaria & Prieto Reference Ortega-Llebaria, Prieto, Vigário, Frota and João Freitas2009, Reference Ortega-Llebaria and Prieto2010).

Other acoustic properties of the stimuli could plausibly affect the interpretation of results of the main experiment, specifically the duration of the final onset consonant, of the penultimate syllable rhyme, and of the segments involved in metathesis. Further discussion can be found in §4.6.2 and in the Supplementary Material. In brief, acoustic duration does not strongly correlate with participants’ responses in the main experiment.

3.4. Preliminary perception study

This preliminary perception study ensures that Spanish-speaking listeners hear stress on the syllable that was intended to be stressed in the stimulus words for the main study.

3.4.1. Materials and task

Recall that the stimuli for the main experiment are four syllables long and have antepenultimate stress (see Table 5). Because they all have antepenultimate stress, it was necessary to modify these words to design a task testing where listeners hear stress.

I created two three-syllable versions of each nonce word – one with antepenultimate stress and one with penultimate stress – by removing the first and final syllables, respectively (e.g., ![]() →

→ ![]() ,

, ![]() ).Footnote

11

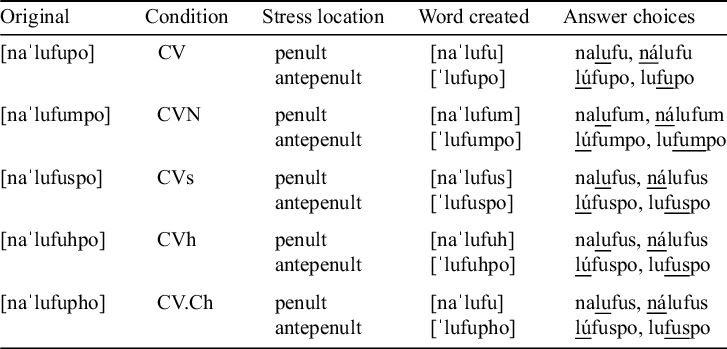

Table 6 illustrates the modified nonce words used in this preliminary perception study.

).Footnote

11

Table 6 illustrates the modified nonce words used in this preliminary perception study.

Table 6 Example stimuli for one word set for preliminary stress experiment.

The experiment was implemented in PCIbex (Zehr & Schwarz Reference Zehr and Schwarz2018). In each trial, listeners heard one word and clicked on one of two given orthographic representations to indicate the word they heard. The two answer choices differed only in the location of stress. Following orthographic conventions of Spanish, antepenultimate stress was marked with an acute accent and penultimate stress was not marked.Footnote

12

Stressed syllables were underlined in both answer choices to ensure that participants visually noticed the difference between choices. Words in three conditions had the same answer choices: CVs, CVh and CV.Ch words all had answer choices with orthographic 〈s〉, even though [s] was not acoustically present in CVh and CV.Ch words. For example, in the penultimate stress condition, ![]() (<

(< ![]() ) and

) and ![]() (<

(< ![]() ) had answer choices nalufus and

nálufus, which would be the corresponding orthographic forms. This should not matter, since the answer choices differed only in stress and /s/ reduction and deletion are common in this context.

) had answer choices nalufus and

nálufus, which would be the corresponding orthographic forms. This should not matter, since the answer choices differed only in stress and /s/ reduction and deletion are common in this context.

Figure 2 Stimulus verification study: accuracy in locating stress by penult type.

There were 162 words. Listener groups A and B each heard half of the words. Listeners in group A heard half of the words in a given set with penultimate stress (CV, CVs, CV.Ch, Filler1 and Filler3) and the other half of the words in the same set with antepenultimate stress (CVN, CVh, Filler2 and Filler4). For a different word set, they heard each word type with the opposite stress pattern. This pattern repeated for all of the word sets. Listeners in group B heard the inverse of group A. Trials were randomised. There were also two practice items and six attention checks.

3.4.2. Participants

Twenty participants from Spain were recruited on Prolific. Ten were assigned to listener group A and ten to listener group B. Region within Spain was not controlled, since the goal is to check if Spanish speakers generally hear stress in the intended location. The experiment lasted 5–15 minutes, and participants were paid. One listener from group A and three from group B were excluded for answering more than one attention check wrong, so the remainder of the analysis includes 16 listeners.

3.4.3. Results

Listeners heard stress where it was intended to be with 88%–98% accuracy across penult type conditions (Figure 2). A mixed-effects logistic regression (fixed effect of word condition, random intercepts for participant and item) finds one significant effect: accuracy was higher for the attention check words than the reference level CV words (

![]() $\beta = -1.58$

,

$\beta = -1.58$

,

![]() $p < 0.05$

). This is expected because the attention check items were unambiguous, and listeners who failed more than one were excluded. The model and post-hoc tests with emmeans found no significant differences between other conditions. Listeners had high overall accuracy in identifying the stressed syllable where it was intended to be, and accuracy did not depend on condition.

$p < 0.05$

). This is expected because the attention check items were unambiguous, and listeners who failed more than one were excluded. The model and post-hoc tests with emmeans found no significant differences between other conditions. Listeners had high overall accuracy in identifying the stressed syllable where it was intended to be, and accuracy did not depend on condition.

In short, the acoustic cues to stress are present on the intended antepenultimate syllables in the stimuli, and Spanish-speaking listeners perceive them. I will thus assume that listeners’ behaviour in the main experiment is based on a correct perception of stress location.

4. Main experiment

4.1. Task

Participants completed the task in their homes; data were collected in 2020. In each trial, participants heard two words with antepenultimate stress that differed only in the type of penultimate syllable, paired as in Table 7 (e.g., one CV–CVN pair was ![]() –

–![]() ). The CV set compares words with different penult types to the word with a CV penult, testing whether words with CV penults are preferred over those with different kinds of heavy penults and the CV.Ch penult. The CV.Ch set compares words with different penult types to the word with a CV.Ch penult, testing whether words with CV.Ch penults are treated differently from words with penults that are unambiguously heavy or light.

). The CV set compares words with different penult types to the word with a CV penult, testing whether words with CV penults are preferred over those with different kinds of heavy penults and the CV.Ch penult. The CV.Ch set compares words with different penult types to the word with a CV.Ch penult, testing whether words with CV.Ch penults are treated differently from words with penults that are unambiguously heavy or light.

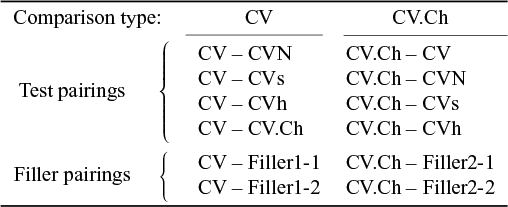

Table 7 Condition pairings for CV and CV.Ch comparisons.

Participants were told that the words were not real words and were asked to choose which word would be a better word of Spanish by clicking buttons on the screen labelled 1 or 2, corresponding to the first and second words they heard.

There were 108 trials, composed of the 9 word sets (Table 5) arranged into the 12 comparisons in Table 7. In each trial, the two words were played with 300 ms in between. Trial order was randomised for each participant, and the order of presentation of the audio files within each trial was counterbalanced. Group A heard half of the word pairs with the base form (CV or CV.Ch) first and the comparison form second (e.g., CV–CVs), and the other half with the comparison form first and the base form second (e.g., CVh–CV). Group B heard the opposite orders. There was one practice trial. Participants also filled out a demographic questionnaire and were paid. The experiment lasted 12–35 minutes.

The task was inspired by Fuchs (Reference Fuchs2018), but differs in several key ways. First, I presented the stimulus words auditorily instead of orthographically, which allowed me to test different allophonic realisations of the same word. Given that metathesis is not represented orthographically, this is crucial. Additionally, Fuchs’s (Reference Fuchs2018) task was a goodness-rating task, which resulted in significant, but small, effects. The current study forces participants to make a binary choice in an attempt to distil their preferences.

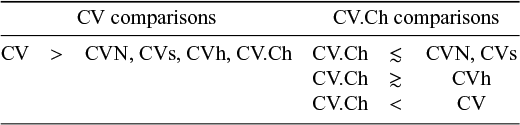

4.2. Hypotheses

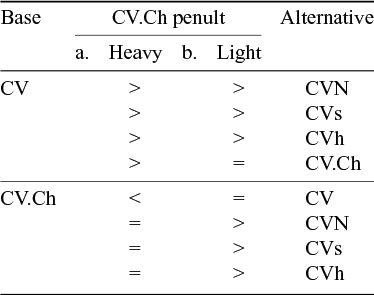

In general, listeners are expected to prefer words with light penults over those with heavy penults. Table 8 lays out listeners’ expected behaviour if they treat CV.Ch penults as heavy (column (a)) or light (column (b)). For the CV-base comparisons, listeners should prefer CV words over alternative CVN, CVs and CVh words. This is the expected preference under both sets of hypotheses, since CV.Ch words are not involved. The CV–CV.Ch comparison distinguishes the two hypotheses. If listeners treat the CV.Ch penult as heavy, they should prefer CV over CV.Ch. If they treat the CV.Ch penult as light, they should not have a preference between CV and CV.Ch.

Table 8 Predictions for listener responses based on whether they treat CV.Ch penults as heavy or light.

The pairs in the CV.Ch comparisons test the hypothesis more directly by comparing CV.Ch words to words with other penult types. For the CV.Ch-base comparisons, the two hypotheses predict different listener behaviour for each comparison type. If listeners treat CV.Ch penults as heavy, they should have no preference between CV.Ch and CVN, CVs or CVh words, and they should prefer CV words over CV.Ch words. (This last preference is the same as the CV–CV.Ch comparison in the CV-base comparisons.) If listeners treat CV.Ch penults as light, they should have no preference between CV.Ch and CV words, and should prefer the CV.Ch word over CVN, CVs and CVh words.

There are multiple possible explanations for why the penults created by metathesis might be treated as heavy or light. In order to separate the experimental results from the interpretation of those results, I leave further discussion of these possibilities for §4.6.

4.3. Statistical models

The results were modelled in mixed-effect logistic regressions using glmer from lme4 in R, and emmeans was used to determine and contrast estimated marginal means and contrasts between other levels of the main predictor (same details as in §3.2). Separate models were built for the CV and CV.Ch comparisons, predicting the likelihood of choosing the base form (CV or CV.Ch) over the alternative. The dependent variable was the response of the base form (coded as 1) vs. the alternative (coded as 0). Coefficients of logistic regressions are in log-odds. Positive coefficients indicate higher log-odds of base response; lower coefficients indicate lower log-odds of the base response (and thus higher log-odds of the alternative response). A log-odds value of 0 corresponds to a probability of 0.5; positive log-odds correspond to a probability greater than 0.5 and negative log-odds correspond to a probability less than 0.5.

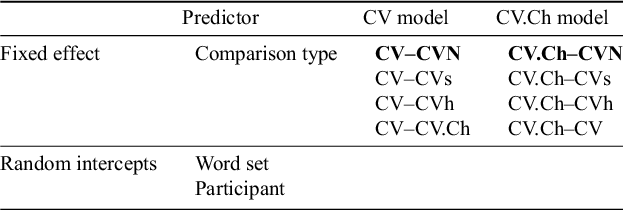

Table 9 shows the fixed effect (comparison type) and random intercepts (word set, participant) in the models. A random slope of condition by participant and condition by word set were not included because models fitted with them resulted in singular fit warnings. Comparison type is dummy coded, and the underlined comparison type is the reference level for the factor. The models respond to the following question: There is a certain log-odds of a base response (e.g., CV) in the reference level of comparison type (e.g., CV–CVN). Does the log-odds of a base response in another comparison type (e.g., CV–CVs) differ from that of the reference level?

Table 9 Predictors in models (reference level in bold).

Tests between other levels of comparison type were done with emmeans, with Tukey adjustment for multiple comparisons. Estimated marginal means are calculated for each comparison type based on the model results, and statistical tests are applied to test for significant differences between the factor levels. For easier interpretation, I used a back-transformation within emmeans to calculate the estimates on the response scale instead of the model’s logit scale. Estimates and confidence limits (95% confidence level) are thus given in probabilities, and contrasts are calculated on the log-odds ratio scale. The estimated probabilities and confidence limits for each comparison type calculated from emmeans are overlaid on the plots of my listeners’ data.

4.4. Participants

The participants were 27 Sevillians (20 female and 7 male), with an average age of 37.9 years (range: 18–70). They were born and completed schooling in the city of Seville and smaller towns in the province. Most had lived their entire lives in the region, although some reported short-term (less than one year; UK, León and Majorca) and long-term stints (two years or longer; Switzerland/Finland, US, Madrid and Galicia) elsewhere. All participants had completed high school; 13 had completed a technical or university degree; and 12 had done postgraduate studies (one did not report education). Participants reported knowledge of languages other than Spanish: English (20), French (7), German (2), Italian (2), Portuguese (2), Gallego (1) and ‘Catalan/Valencian’ (1). Three participants reported almost-native proficiency in another language (English, French and Gallego). Some also participated in the experiment reported in Gilbert (Reference Gilbert2023).

4.5. Results

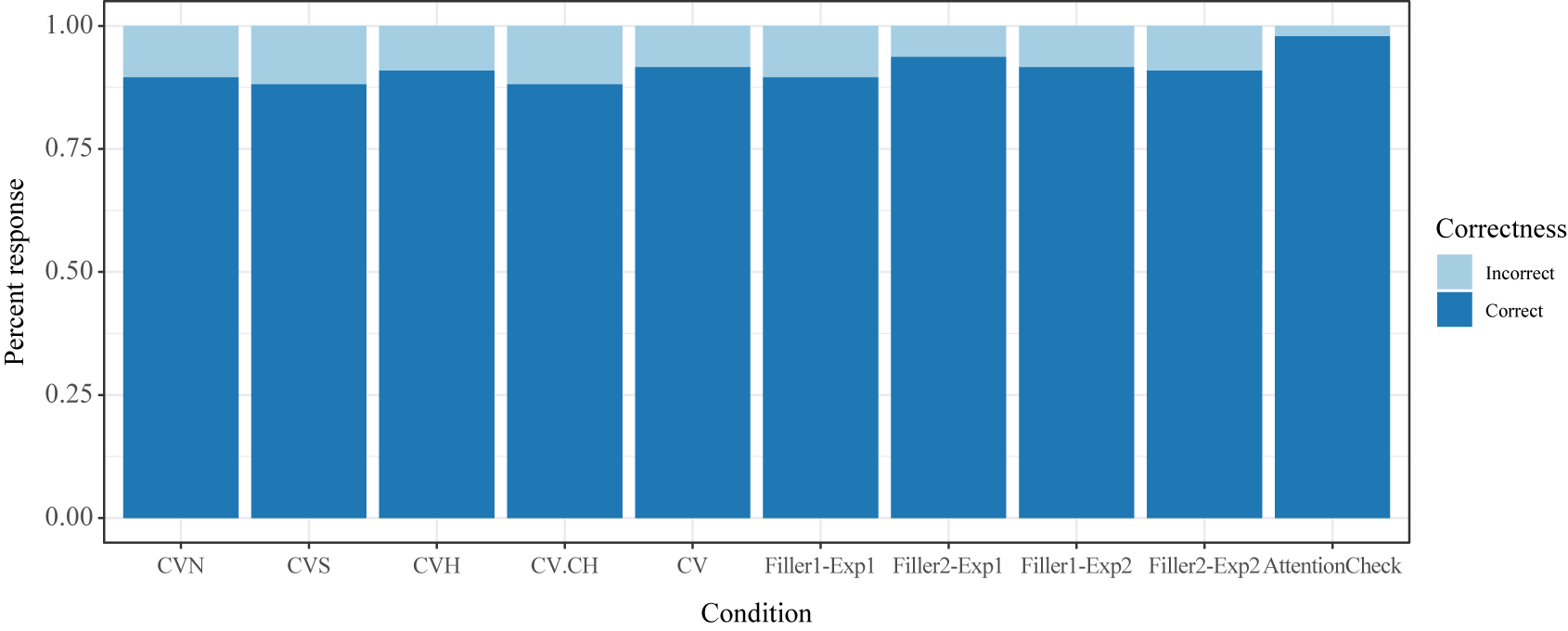

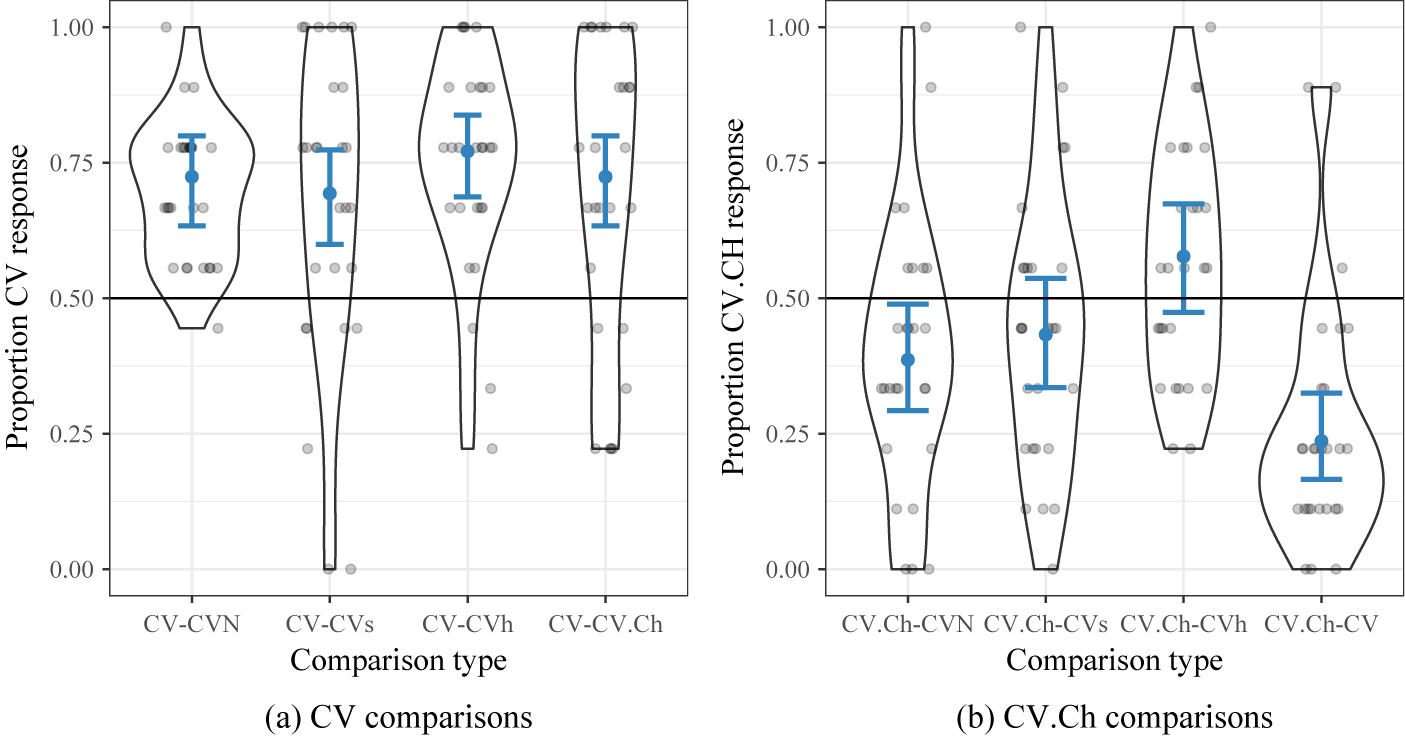

Figure 3 shows results for the CV comparisons (Figure 3a) and CV.Ch comparisons (Figure 3b). The y-axis is the proportion of base response (CV or CV.Ch) over the alternative. Each dot represents an individual speaker’s response rate for the comparison type. The line at 0.5 is for visual clarity. Dots above the line indicate that a listener chose the base form over the alternative more than 50% of the time; dots below the line indicate that a listener chose the alternative over the base more than 50% of the time. The blue dots and error bars are predicted probabilities and 95% confidence limits produced by emmeans based on the logistic regressions.

Figure 3 Listener results from the stress judgement task.

4.5.1. CV comparisons

In the CV comparisons (Figure 3a), the overall rate at which listeners chose CV over the alternative ranged from 67% to 74% across comparison types (percentages calculated within-category, combining all listener responses). Listeners preferred words with light penults over each alternative (CV > CVN, CVs, CVh, CV.Ch; ![]() >

> ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ). The rate of preference for CV is similar for all of the alternative forms, including those with surface-heavy penults and those with CV.Ch penults.

). The rate of preference for CV is similar for all of the alternative forms, including those with surface-heavy penults and those with CV.Ch penults.

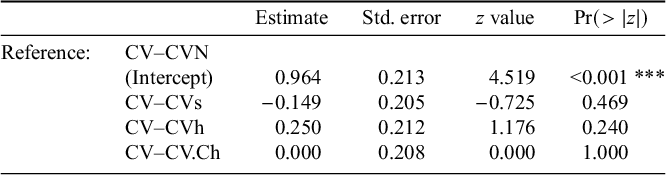

The logistic regression supports these observations (Table 10). Recall that the model predicts the log-odds of choosing the base CV word over the alternative. Positive coefficients indicate higher log-odds of a CV response in the given comparison type than in CV–CVN (the reference level comparison type), while negative coefficients indicate the opposite. For CV–CVN comparisons, listeners chose the base CV word with a log-odds of 0.964 (the intercept;

![]() $p < 0.001$

). In terms of probability, this gives an estimated probability of 0.72 of a CV response.

$p < 0.001$

). In terms of probability, this gives an estimated probability of 0.72 of a CV response.

Table 10 Model for CV comparisons predicting probability of CV response (vs. alternative).

The effect of comparison type is not significant: the log-odds with which listeners prefer the base CV word over the alternative is not statistically different between the reference level CV–CVN and any other level (vs. CV–CVs:

![]() $\beta = -0.149$

,

$\beta = -0.149$

,

![]() $p = 0.469$

); vs. CV–CVh:

$p = 0.469$

); vs. CV–CVh:

![]() $\beta = 0.250$

,

$\beta = 0.250$

,

![]() $p = 0.240$

; vs. CV–CV.Ch:

$p = 0.240$

; vs. CV–CV.Ch:

![]() $\beta = 0.000$

,

$\beta = 0.000$

,

![]() $p = 1.000$

).

$p = 1.000$

).

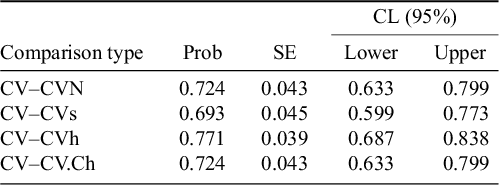

The predicted probabilities for each level of comparison type (from emmeans) are in Table 11. For each comparison type, the predicted probability of a CV response is well above chance (ranging from 0.69 to 0.77). Furthermore, the 95% confidence limits do not span 0.5 (chance), indicating a high likelihood that the true parameter lies above chance. Listeners choose the alternative over the base form significantly over chance in all comparisons. The emmeans contrasts between the predicted probabilities suggest that the probabilities are not significantly different between any of the comparison types (results not shown).

Table 11 emmeans predictions by comparison type for CV model. Intervals are back-transformed from the logit scale.

That listeners prefer CV over CV.Ch words at a similar rate to that at which they prefer CV over CVN, CVh and CVs words does not suggest a robust difference between conditions, but neither does it provide positive evidence for their similarity. The next set of comparisons tests CV.Ch words directly against CVN, CVs and CVh words to address this issue. Do listeners treat all penult types as similarly unacceptable? The statistically significant results in the CV.Ch comparisons are compatible with the lack of effect in the CV comparisons.

4.5.2. CV.Ch comparisons

In the CV.Ch comparisons (Figure 3b), the overall rate at which listeners chose CV.Ch over the alternative was less than 50% in CV.Ch–CVN comparisons (40%) and CV.Ch–CVs comparisons (44%). That is, they dispreferred CV.Ch words in comparison to CVN and CVs words (e.g., ![]() <

< ![]() ;

; ![]() <

< ![]() ). Listeners chose the CV.Ch word even less frequently in CV.Ch–CV comparisons (26%), which had a CV word as the alternative (

). Listeners chose the CV.Ch word even less frequently in CV.Ch–CV comparisons (26%), which had a CV word as the alternative (![]() <

< ![]() ). In contrast, the CV.Ch–CVh comparisons were the only ones in which listeners chose the CV.Ch word at rate over 50% (56%;

). In contrast, the CV.Ch–CVh comparisons were the only ones in which listeners chose the CV.Ch word at rate over 50% (56%; ![]() >

> ![]() ).

).

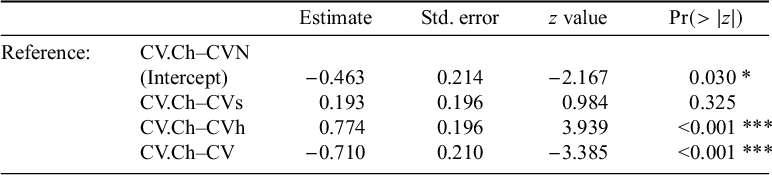

The logistic regression (Table 12) supports the visual interpretation of the results. In CV.Ch–CVN comparisons (the reference level of comparison type), the log-odds of a CV.Ch response is −0.463 (

![]() $p < 0.05$

). This indicates that listeners are less likely to choose CV.Ch than CVN (probability of 0.386 of choosing CV.Ch). In relation to this reference level, the log-odds of choosing CV.Ch in CV.Ch–CVs comparisons is not significantly different (

$p < 0.05$

). This indicates that listeners are less likely to choose CV.Ch than CVN (probability of 0.386 of choosing CV.Ch). In relation to this reference level, the log-odds of choosing CV.Ch in CV.Ch–CVs comparisons is not significantly different (

![]() $\beta = 0.193$

,

$\beta = 0.193$

,

![]() $p = 0.325$

). However, in comparison to the reference level, the log-odds of a CV.Ch response is significantly lower in CV.Ch–CV comparisons (

$p = 0.325$

). However, in comparison to the reference level, the log-odds of a CV.Ch response is significantly lower in CV.Ch–CV comparisons (

![]() $\beta = -0.710$

,

$\beta = -0.710$

,

![]() $p < 0.001$

) and significantly higher in CV.Ch–CVh comparisons (

$p < 0.001$

) and significantly higher in CV.Ch–CVh comparisons (

![]() $\beta = 0.774$

,

$\beta = 0.774$

,

![]() $p < 0.001$

).

$p < 0.001$

).

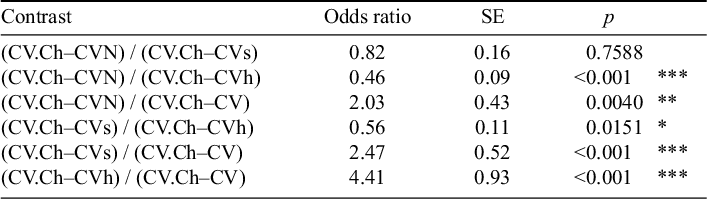

Table 12 Model for CV.Ch comparisons predicting probability of CV.Ch response (vs. alternative).

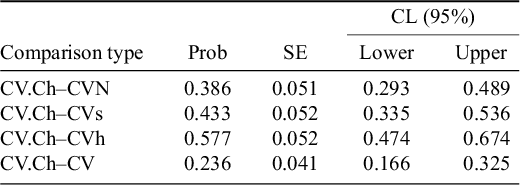

The emmeans estimates of probability CV.Ch response for each comparison type are shown in Table 13. In most comparison types, the predicted probability of a CV.Ch response is less than 0.5 (lower than chance). CV.Ch–CVh comparisons are the only ones for which the predicted probability of a CV.Ch response is greater than 0.5. Note that the 95% confidence limits include chance (0.5) for CV.Ch–CVs and CV.Ch–CVh comparisons, indicating that we cannot exclude the possibility that the true estimate could be at chance. The upper confidence limit for CV.Ch–CVN comparisons is also close to 0.5 (0.489). The emmeans contrasts between the predicted probabilities (Table 14) suggest that the predicted probabilities are significantly different between all levels of comparison type, except CV.Ch–CVN vs. CV.Ch–CVs.

Table 13 emmeans predictions by comparison type for CV.Ch model. Intervals are back-transformed from the logit scale.

Table 14 emmeans contrasts between levels of comparison type for CV.Ch model. Tests are performed on the log-odds ratio scale. P value adjustment: Tukey method for comparing a family of four estimates.

Although there is a general dispreference for CV.Ch words compared to words with CVN and CVs penults (discussed further in §4.5.3), there are two crucial points. First, the predicted confidence limits for the CV.Ch–CVs comparison include chance (0.335–0.536); for CV.Ch–CVN comparisons, the confidence limits approach chance (0.293–0.489). Second, the predicted probability of a CV.Ch response in CV.Ch–CV comparisons is significantly lower than in all other comparisons, and the confidence limits are well below chance (0.166–0.325). In other words, despite an overall dispreference for CV.Ch in comparison to some words with heavy penults, there is a significantly stronger dispreference for these CV.Ch words when the alternative has a CV penult.

4.5.3 Results discussion

Table 15 summarises the results. Listeners prefer antepenultimate-stress words with CV penults over similar words with closed penults (CVN, CVs and CVh) or penults where /s/ has metathesised out (CV.Ch). Regardless of what consonant or surface manifestation of /s/ closes the penult, Sevillian listeners are more likely to choose the CV word, and they do so at similar rates across the alternatives. When choosing between antepenultimate-stress words with CV.Ch penults and those that have CVN, CVs or CVh penults, listeners have preferences, but these preferences are weak. Listeners choose CV.Ch words less frequently than CVN and CVs words and more frequently than CVh words, although the confidence limits around these predicted probabilities include, or are near, chance.

Table 15 Summary of listeners’ preferences in the stress judgement task.

The crucial point is the following: despite the weak dispreference for CV.Ch words when the alternatives are CVN or CVs, this dispreference for CV.Ch words is much stronger when the alternative is a CV word. The relative strength of this dispreference suggests that CV.Ch words are treated more like words with surface-heavy penults than like words with light CV penults. The results are broadly as predicted if CV.Ch penults are treated as heavy (cf. Table 8).

The differences between rates of preference for the CV.Ch word when compared to words with CVN, CVs and CVh penults are somewhat unexpected. The CVN, CVs and CVh words all have heavy penults and should be treated similarly. Furthermore, regardless of whether CV.Ch forms are taken to have heavy or light penults, neither account predicts that they should be dispreferred to forms with surface-heavy penults like CVN and CVs; they should either be treated similarly to these alternatives (if treated as heavy) or preferred over them (if treated as light). The dispreference for CV.Ch relative to CVN and CVs does not necessarily undermine the results. This dispreference could actually further support the idea that CV.Ch forms are treated as having heavy penults, since they are even more dispreferred than words with unambiguously heavy penults.

One result does not fit clearly with the predictions: listeners prefer CV.Ch over CVh words, and this is the only CV.Ch comparison where they choose CV.Ch more than 50% of the time. If CV.Ch derives from /sC/, then CV.Ch and CVh forms share an underlying representation and should be treated similarly. I suspect the preference for CV.Ch over CVh words arises because this comparison is qualitatively different. The judgement between CV and CVN words is a decision between two different words. In the judgement between CV.Ch and CVh words, the decision is between allophonic realisations of a sound in the same word. Between two non-standard pronunciations, listeners choose the one that is more frequent in their dialect (CV.Ch; see §2.1). Thus, this preference could be due to their familiarity with surface phonetic forms, rather than to the differing phonological structure of the forms. Another possibility is that the acoustics of the CVh stimulus words were particularly bad: a combination of surface-present coda [h] and a long closure duration of the final onset consonant resulted in an acoustically overlong penult (measurements are given in the Supplementary Material).

If participants prefer CV.Ch over CVh because CV.Ch is the more common allophonic variant of /sC/ sequences, we might also expect listeners to prefer CV.Ch over CVs, which is also infrequent in conversational speech (§2.1). They do not: CV.Ch forms are chosen slightly less than 50% of the time in CV.Ch–CVs comparisons. I speculate that this is because the full sibilant variant is the national and international standard. While listeners prefer the reduced form of their own dialect over reduced forms that are rare in their dialect (CV.Ch > CVh), they do not always prefer the reduced form of their dialect over the standard (CV.Ch

![]() $\lesssim $

CVs). The fact that CV.Ch was preferred over CVh but not over CVs could also be due to the fact that words with CVs penults did not have the acoustic ‘over-heaviness’ of the CVh penults (see the Supplementary Material).

$\lesssim $

CVs). The fact that CV.Ch was preferred over CVh but not over CVs could also be due to the fact that words with CVs penults did not have the acoustic ‘over-heaviness’ of the CVh penults (see the Supplementary Material).

These observations lead to a possibly different interpretation of the results: that listeners’ choices between the words were based on sociolinguistic factors, not syllable weight.Footnote 13 Listeners’ preference for CV words in CV–CVN and CV–CVs comparisons would be based on the heaviness of CVN and CVs penults. In CV–CVh and CV–CV.Ch comparisons, however, listeners’ preference for CV words could be because CVh and CV.Ch are non-standard variants. The additional surface weight of the CVh word would compound the dispreference for CVh words. This explanation could also apply to the slight dispreference for CV.Ch relative to CVN and CVs: CV.Ch words contain a non-standard variant and the others do not. When evaluating this possible explanation, it is important to keep in mind that although CV.Ch realisations of /sC/ sequences are non-standard at the supraregional level, they are apparently something of a regional standard. In data from nearby Málaga (Vida-Castro Reference Vida-Castro2016), CV.Ch variants are acceptable in most read speech styles, and most frequent among older speakers and highly educated speakers. (These patterns contrast with post-affricated variants, which are most frequent among young speakers and speakers with lower levels of education, and are avoided in read speech.) Whether these explanations hold would come down to how listeners interpreted the task: whether their decisions were based on the phonotactics of a new lexical item, or on the presence of (non-)standard allophonic variants. This would require further empirical testing.

4.6. Interpretation of results: syllable weight

This constellation of results suggests that CV.Ch penults are treated as heavy when it comes to stress assignment, similar to CVs, CVN and CVh penults. There are several possible ways to interpret these results. Because there is no evidence that the syllables created by metathesis are treated as light, I focus only on different analyses that can account for their heaviness: opaque process interaction or representational separation (§4.6.1, elaborated further in §5), syllabification (§4.6.2) and acoustic duration (§4.6.3).

4.6.1. Process interactions and representational separation

That CV.Ch penults are treated as heavy is in line with conceptualising stress and metathesis as processes that apply serially, in an opaque interaction where either stress is assigned before metathesis or the two processes apply at the same time to the same representation. In either case, stress only ‘sees’ the heavy penult, not the result of metathesis. Another way of understanding the stress–metathesis ‘interaction’ is as representational separation: stress and metathesis operate on different levels of the phonological grammar, on different types of representations, so the result of one cannot affect the result of the other. The goal of §5 is to flesh out some of these analytical possibilities in more detail.

4.6.2. Syllabification

Another way of interpreting the result that Sevillians seem to treat CV.Ch penults as heavy would be to say that these penults maintain heaviness due to syllabification. Stop–h sequences could syllabify across the syllable boundary, with the stop in the coda of the preceding syllable (VC.h, heterosyllabic), as opposed resyllabifying as an onset (V.Ch, tautosyllabic). Another possibility is that the stop is representationally linked to both syllables. I discuss these issues here so readers can take them into consideration in interpreting the results, but syllabic affiliation can only be established with future experimental work.

Resyllabification

If stop–h forms are syllabified as VC.h, metathesis would result in the same syllable structure post-metathesis as pre-metathesis, but with the segments swapped (e.g., ![]() , LLHL vs.

, LLHL vs. ![]() , also LLHL). Both have a heavy penult. This VC.h syllabification is possible, but unlikely for several reasons.

, also LLHL). Both have a heavy penult. This VC.h syllabification is possible, but unlikely for several reasons.

First, the VC.h syllabification is not compatible with restrictions on coda obstruents in Spanish. Coda obstruents are restricted both word-medially and word-finally, and those that are allowed are often reduced or deleted (Campos-Astorkiza Reference Campos-Astorkiza2012; Colina Reference Colina2012). This pressure against coda obstruents is synchronically and diachronically evident throughout Romance languages (recall (3); Malmberg Reference Malmberg1965; Vennemann Reference Vennemann1988; Mason Reference Mason1994 and references therein). Syllabifying the sequence as VC.h maintains a consonant in coda position, and replaces /s/ with a voiceless stop. Depending on the theoretical approach taken – for example, based on sonority – a voiceless stop can be an even worse coda than [s] or [h].Footnote 14

Second, if /p, t, k/ were syllabified into coda position, they should reduce like other coda obstruents in Western Andalusian Spanish. In these varieties, coda /p, t, k/ behave like coda /s/: they undergo debuccalisation and metathesis (and affrication), and their weakening is accompanied by variable lengthening of the following consonant (![]() →

→ ![]()

![]() $\sim $

$\sim $

![]() ]; Del Saz Reference Del Saz, Calhoun, Escudero, Tabain and Warren2019a; Henriksen et al. Reference Henriksen, Galvano and Fischer2023). In Sevillian, /p, t, k/ in metathesised stop–h sequences do not reduce to [h] as in (5), suggesting that they are onsets, not codas (Gerfen Reference Gerfen and Lombardi2001).

]; Del Saz Reference Del Saz, Calhoun, Escudero, Tabain and Warren2019a; Henriksen et al. Reference Henriksen, Galvano and Fischer2023). In Sevillian, /p, t, k/ in metathesised stop–h sequences do not reduce to [h] as in (5), suggesting that they are onsets, not codas (Gerfen Reference Gerfen and Lombardi2001).

If VC.h is unlikely, the other option is V.Ch. One possible objection to the V.Ch syllabification is that sequences of stops plus [h] are unattested in Spanish. I follow the discussion in Gilbert (Reference Gilbert2023) about this issue. Neither the VC.h nor the V.Ch syllabifications create preferred sequences in Spanish. The V.Ch syllabification is bad because it creates unattested onset sequences. Additionally, stop–h onsets do not have a sufficient sonority rise (Sonority Sequencing Principle; Clements Reference Clements1990; Blevins Reference Blevins and Goldsmith1995). The VC.h syllabification is bad because it (a) violates the restriction against coda obstruents, as already discussed and (b) violates the preference for sonority to fall across a syllable boundary (Syllable Contact Law; Murray & Vennemann Reference Murray and Vennemann1983; Clements Reference Clements1990; Gouskova Reference Gouskova2004). Given that coda obstruents are so dispreferred in these varieties of Spanish, it is not immediately clear whether the VC.h or V.Ch syllabification is worse. One theoretical possibility that might ameliorate the bad onset issue with V.Ch is Steriade’s (Reference Steriade, Cole and Kisseberth1994) proposal for Mazatec. In brief, she suggests that complex onsets are less marked if they are structurally similar to single segments. In Sevillian, Ch onsets may be less marked than they appear because the sequence consists of a closure and release, two phases which can be present in a single segment too (in aspirated stops). In short, how to account for Ch as a viable onset is an unresolved issue, but it is not obvious that the V.Ch syllabification is worse than VC.h.

Multiple linking

CV.Ch syllables also could be interpreted as heavy if the stop is representationally linked to both syllables. Coda /s/ reduction is often accompanied by variable lengthening of the following consonant in varieties of Andalusian Spanish (e.g., Alvar Reference Alvar1955; Romero Reference Romero1995b; Gerfen Reference Gerfen2002; Campos-Astorkiza Reference Campos-Astorkiza, Hajicová, Kotešovcová and Mírovský2003; Martínez-Gil Reference Martínez-Gil2012). Variable lengthening is also reported in varieties with metathesis (e.g., ![]() ; Ruch Reference Ruch2008; O’Neill Reference O’Neill2010; Ruch & Harrington Reference Ruch and Harrington2014; Henriksen et al. Reference Henriksen, Galvano and Fischer2023). Long stop closures accompanying /s/ reduction have been treated as compensatory lengthening in multiple varieties of Spanish (Hualde Reference Hualde1989b; Campos-Astorkiza Reference Campos-Astorkiza, Hajicová, Kotešovcová and Mírovský2003; Martínez-Gil Reference Martínez-Gil2012).

; Ruch Reference Ruch2008; O’Neill Reference O’Neill2010; Ruch & Harrington Reference Ruch and Harrington2014; Henriksen et al. Reference Henriksen, Galvano and Fischer2023). Long stop closures accompanying /s/ reduction have been treated as compensatory lengthening in multiple varieties of Spanish (Hualde Reference Hualde1989b; Campos-Astorkiza Reference Campos-Astorkiza, Hajicová, Kotešovcová and Mírovský2003; Martínez-Gil Reference Martínez-Gil2012).

A moraic analysis (e.g., Hayes Reference Hayes1989) of compensatory lengthening would go as follows. /s/ reduces by delinking (in part or in full) from its mora, leaving the mora slot empty. The following consonant then spreads into that timing slot and is doubly linked, occupying both coda and onset position. Double linking is often argued to manifest as longer acoustic duration (Broselow et al. Reference Broselow, Chen and Huffman1997; Cohn Reference Cohn2003; Khattab & Al-Tamimi Reference Khattab and Al-Tamimi2014). Under this representation, the long stop would be syllabified across the syllable boundary (Maddieson Reference Maddieson and Fromkin1985); the syllable preceding the stop–h sequence would be heavy; and the assumption that metathesis changes syllable structure would be untenable. While this representation of consonant lengthening could be viable, there are several complications. Lengthening is variable and inversely correlated with the duration of metathesised [h], and stop closures appear to be shortening again as the metathesis change advances (Parrell Reference Parrell2012; Torreira Reference Torreira2012; Ruch & Harrington Reference Ruch and Harrington2014). Furthermore, lengthening can occur with /s/ debuccalisation, not only deletion, so the moraic slot is not entirely empty. It is not clear how a mora-sharing account of lengthening would account for these factors (see Gerfen Reference Gerfen2002), or for the interaction between lengthening and metathesis.

In the stimuli used for the experiment reported in this article, the CV.Ch stimulus words have similar final onset consonant durations to CV words (e.g., ![]() =

= ![]() ), so acoustic lengthening would not provide reason for listeners to treat CV.Ch penults as heavier than CV penults (see Figure 1 in the Supplementary Material).