Introduction

Disease manifestation varies widely between individuals, even when infected with the same pathogen. Pathologies can be linked to specific genetic mutations where the occurrence of disease is virtually guaranteed. The outcome for many conditions, however, is more unpredictable. Moreover, whether a disease occurs or not can be influenced by external factors, such as environment and lifestyle, which appear to operate independent of genetic information inherited by the affected individual. Understanding how these factors promote disease in some individuals but not others is key to the prediction of disease risk and promotion of health in a population.

The adaptation of hosts and pathogens to display mild disease or asymptomatic infection is theorised to occur via a co-evolutionary arms race that promotes an equilibrium between host survivability and pathogen transmission, reducing pathology and increasing tolerance to infection (Glass et al., Reference Glass, Crutchley and Jensen2012; Sironi et al., Reference Sironi, Cagliani, Forni and Clerici2015). In contrast, novel infection of hosts that have not co-evolved with a pathogen would be expected to be more susceptible to severe disease (Glass et al., Reference Glass, Crutchley and Jensen2012; Seal et al., Reference Seal, Dharmarajan and Khan2021). This has been shown for numerous zoonotic infections and by the transfer of high-yield, exotic livestock breeds into endemic regions of disease (Glass, Reference Glass2001; Seal et al., Reference Seal, Dharmarajan and Khan2021). Despite co-evolution of pathogen–host interaction towards milder disease outcomes, there is still the unpredictable potential for members of a tolerant population to suffer acute disease and for those of susceptible breeds to show limited clinical signs (Glass et al., Reference Glass, Preston, Springbett, Craigmile, Kirvar, Wilkie and Brown2005).

To address how variability in disease susceptibility can be generated, our work has aimed to identify factors that promote the markedly different outcomes that occur when different cattle breeds are infected with the tick-borne parasite Theileria annulata, the causative agent of tropical theileriosis. Data indicate that susceptibility to this disease is, in part, mediated by direct interactions between pathogen-derived factors and the host genome that influence chromatin structure and gene expression. The importance of the epigenetic landscape is often overlooked when seeking to identify susceptibility-linked heritable traits but could make a significant contribution given the known role of the epigenome in numerous infectious and non-infectious diseases (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Hollin, Lenz and Le Roch2021).

Pathogenesis and cellular transformation in tropical theileriosis

Tropical theileriosis is a disease of economic importance to livestock production and is endemic over much of Asia and North Africa (Minjauw and McLeod, Reference Minjauw and McLeod2003). Acute disease results in dysregulation of the immune response and lung pathology that mirrors numerous viral diseases. Both large and small production systems are susceptible, and the impact on poorer subsistence farmers is catastrophic. European cattle breeds (Bos taurus), such as Holstein, show a greater susceptibility to acute disease than breeds native to endemic regions, like Sahiwal (Bos indicus) (Glass et al., Reference Glass, Crutchley and Jensen2012). This should be expected, as native breeds that have co-evolved with Theileria would be closer to reaching an equilibrium in the trade-off between host survivability and pathogen transmissibility. Efforts have been made, including the national programme in India (Singh, Reference Singh2015), to improve productivity by crossbreeding tolerant native cattle breeds with European breeds. While this has mitigated losses, infected crossbred animals still show clinical signs and lower production than European breeds (Larcombe et al., Reference Larcombe, Kolte, Ponnudurai, Kurkure, Magar, Velusamy, Rani, Rubinibala, Rekha, Alagesan, Weir and Shiels2019).

Previous studies have confirmed that Sahiwal cattle are tolerant to T. annulata infection when compared to Holstein cattle (Glass et al., Reference Glass, Preston, Springbett, Craigmile, Kirvar, Wilkie and Brown2005). A pro-inflammatory response (cytokine storm) has been observed in infected Holstein calves, allowing postulation that acute disease pathology is linked to parasite-mediated dysregulation of the host immune response (Glass et al., Reference Glass, Crutchley and Jensen2012). In support of that premise, transcriptome analysis on T. annulata-infected leukocytes, B. taurus (Holstein) vs B. indicus (Sahiwal), has found that tolerance is associated with altered expression of hundreds of infection-associated bovine genes that operate in innate immunity and oncogenesis, demonstrating a multifaceted phenotype (Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Paxton, Waddington, Talbot, Darghouth and Glass2008; Larcombe et al., Reference Larcombe, Capewell, Jensen, Weir, Kinnaird and Glass2022). However, despite showing a statistically significant breed associated trend across both sets of samples, many genes showed a degree of variable transcript level within each breed. Given the complicated nature of the data, it is not clear how differential susceptibility to tropical theileriosis arises. One model for this is that divergent interaction between pathogen factors and host chromatin promote different epigenetic landscapes that lead to a wide range of phenotypes, both between and within breed: from tolerance to acute disease.

The major point of host–pathogen interaction associated with pathology in tropical theileriosis is the macroschizont-infected leukocyte. Establishment of the infected cell is accompanied by transformation into a cancer-like cell that metastasises to several organs, including the lungs. Destruction of the lymphoid system and massive pulmonary oedema then occur (Irvin and Morrison, Reference Irvin, Morrison and Soulsby1987), and differences in breed susceptibility have been linked to these events (Chaussepied et al., Reference Chaussepied, Janski, Baumgartner, Lizundia, Jensen, Weir, Shiels, Weitzman, Glass, Werling and Langsley2010). Transformation of leukocytes occurs via constitutive activation of bovine transcription factors, such as NF-κB and AP1, to promote infected cell survival and oncogenesis (Shiels et al., Reference Shiels, Langsley, Weir, Pain, McKellar and Dobbelaere2006), but these factors also act as pro-inflammatory mediators. Activation of these host cell ‘Janus-like’ transcription factors is modulated by parasite-dependent reorganisation of the infected cell gene expression network (Durrani et al., Reference Durrani, Weir, Pillai, Kinnaird and Shiels2012). Thus, while some NF-κB target genes show elevated expression, others are negatively regulated, and expression of interferon-stimulated genes is moderated (Oura et al., Reference Oura, McKellar, Swan, Okan and Shiels2006; Durrani et al., Reference Durrani, Weir, Pillai, Kinnaird and Shiels2012). More recent work extends these findings and indicates that differential modulation of the infection-associated transcription network is linked to breed susceptibility (Larcombe et al., Reference Larcombe, Capewell, Jensen, Weir, Kinnaird and Glass2022). Thus, significant differences (<0.1 FDR) in the expression of hundreds of infection-associated genes were identified between macroschizont-infected cell lines derived from 6 infected Sahiwal calves compared to 5 Holsteins. Pathway analysis highlighted an enrichment of genes and pathways associated with innate immunity and cholesterol biosynthesis, and a modulated type I interferon response was prominent. These results demonstrate that the expression of genes with potential to impact the outcome of infection is actively manipulated by the parasite in a breed-dependent manner. Because most intracellular pathogens hijack the host cell machinery to construct a niche that promotes their survival, the information gained from the Theileria model may apply to other pathogen–host interactions.

A common pathogen hijacking strategy deployed to establish an intracellular niche is the export of molecules that co-opt regulation of host cell gene expression. Pathogens subvert regulation of gene expression by corrupting host transcription factor (TF) activity and by altering host chromatin structure to modulate TF accessibility (Cheeseman and Weitzman, Reference Cheeseman and Weitzman2015; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Hollin, Lenz and Le Roch2021). Theileria annulata likely deploys both strategies. Direct manipulation of transcription factor state is demonstrated by constitutive activation of NF-ĸB via hijacking of the IĸB kinase signalosome (Heussler et al., Reference Heussler, Rottenberg, Schwab, Küenzi, Fernandez, McKellar, Shiels, Chen, Orth, Wallach and Dobbelaere2002), while parasite factors encoded in TashAT gene cluster are indicated as modulators of host chromatin structure (Swan et al., Reference Swan, Stern, McKellar, Phillips, Oura, Karagenc, Stadler and Shiels2001; Shiels et al., Reference Shiels, Langsley, Weir, Pain, McKellar and Dobbelaere2006; Larcombe et al., Reference Larcombe, Capewell, Jensen, Weir, Kinnaird and Glass2022). TashAT proteins travel to infected leukocyte nuclei, bind AT-rich DNA and contain AT-hook domains that are organised in a manner similar to mammalian high mobility group A (HMGA) proteins. HMGAs operate by binding and affecting various AT-rich genetic (DNA) motifs to modify chromatin structures and methylation, regulating transcription factor accessibility and gene expression. HMGAs therefore act as hubs of nuclear function (Reeves, Reference Reeves2001) and have a major role in development, stem cell maintenance, cholesterol biosynthesis and the inflammatory response (Treff et al., Reference Treff, Pouchnik, Dement, Britt and Reeves2004; Henriksen et al., Reference Henriksen, Stabell, Meza-Zepeda, Lauvrak, Kassem and Myklebost2010; Vignali and Marracci, Reference Vignali and Marracci2020). These pathways are also differentially modified by Theileria infection, depending on whether the infected cell line was derived from a tolerant or susceptible host (Larcombe et al., Reference Larcombe, Capewell, Jensen, Weir, Kinnaird and Glass2022). Due to the similarity between mammalian HMGAs and parasite TashAT proteins, we proposed that they act in a related manner and that the pathogen modifies host chromatin and TF accessibility by binding AT-rich genetic motifs to influence the epigenetic landscape and disease susceptibility. In support of this model, many loci ascribed as causal variants for disease susceptibility have been linked to regions of chromatin accessibility (Maurano et al., Reference Maurano, Humbert, Rynes, Thurman, Haugen, Wang, Reynolds, Sandstrom, Qu, Brody, Shafer, Neri, Lee, Kutyavin, Stehling-Sun, Johnson, Canfield, Giste, Diegel, Bates, Hansen, Neph, Sabo, Heimfeld, Raubitschek, Ziegler, Cotsapas, Sotoodehnia, Glass, Sunyaev, Kaul and Stamatoyannopoulos2012).

Breed-specific DNA motifs and selection of epigenetic architecture

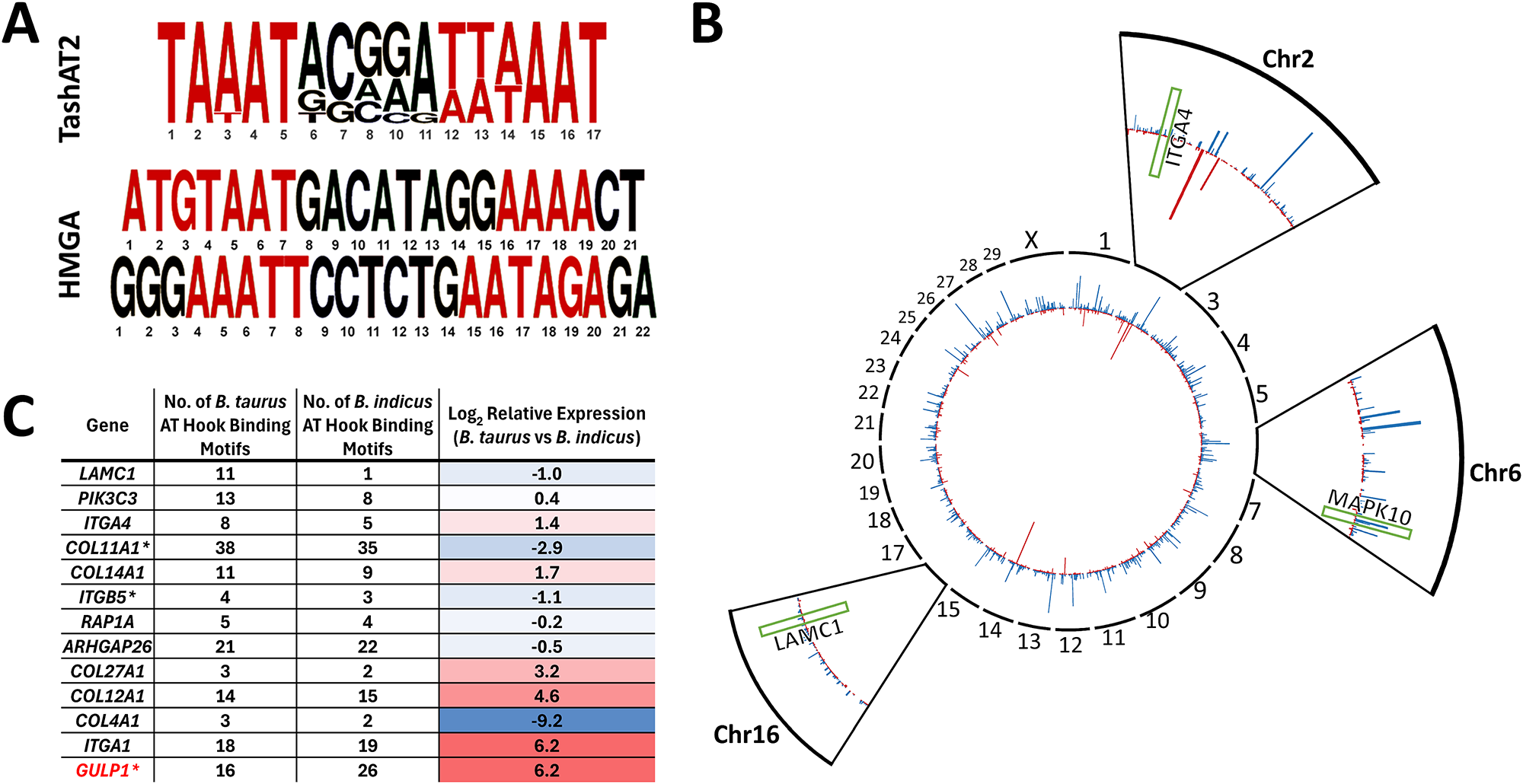

Expression of a TashAT encoding gene (TashAT2) in a transfected bovine macrophage cell line altered transcript levels of more than 800 bovine genes (Durrani et al., Reference Durrani, Kinnaird, Cheng, Brühlmann, Capewell, Jackson, Larcombe, Olias, Weir and Shiels2023). Pathway analysis indicated involvement in focal adhesion, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, axon guidance and integrin signalling with similarity to pathways regulated by mammalian HMGA2 (focal adherence, TGF-β, integrin signalling) (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Ozturk, Cordero, Mehta, Hasan, Cosentino, Sebastian, Krüger, Looso, Carraro, Bellusci, Seeger, Braun, Mostoslavsky and Barreto2015), supporting postulation that the parasite factor acts as an HMGA mimic. Moreover, 184 genes (P < 0.1) modulated by TashAT2 also display differential expression between Sahiwal and Holstein infected cells, with enrichment of genes operating in Integrin signalling (P = 0.04) and Axon guidance (P = 0.02). A further link was established by comparison of the published B. taurus and B. indicus genomes for AT-rich nucleotide motifs bound by TashAT2 (Larcombe et al., Reference Larcombe, Capewell, Jensen, Weir, Kinnaird and Glass2022). The results showed that the pattern (number and positions) of the TashAT2-bound consensus motif differs substantially between the 2 genomes (Figure 1) and that more than 45% of genes differentially expressed between Sahiwal and Holstein infected cells feature at least one putative TashAT2 binding motif (P < 0.001). Within this cohort, there is enrichment in pathways modulated by infection and differences in the number of TashAT2 binding motifs between genes of B. indicus vs B. taurus. An example is the EGF/PI3K pathway, linked to transformation of the infected leukocyte and modulated by mammalian AT-hook proteins (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Wu2021). Furthermore, altered expression of integrin signalling genes is associated with virulence of the Theileria infected leukocyte (Haidar et al., Reference Haidar, Whitworth, Noé, Liu, Vidal and Langsley2015) and can occur via TashAT2 (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Ozturk, Cordero, Mehta, Hasan, Cosentino, Sebastian, Krüger, Looso, Carraro, Bellusci, Seeger, Braun, Mostoslavsky and Barreto2015) and HMGA1 (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Edberg and Li2001). Based on these findings, it can be postulated that variability in the arrangement and, potentially sequence, of motifs bound by AT-hook proteins vary between breeds and possibly individual animals. Such variability could impact on epigenome architecture and the resulting expression level of multiple genes linked to disease susceptibility. How the variability in motif arrangement within the host genome is generated is not known. The nucleotide motif bound by HMGA AT-hook proteins and TashAT2 is only semi-conserved and consists of a pair of AT-rich sequences interspersed with a region higher in GC content (Swan et al., Reference Swan, Stern, McKellar, Phillips, Oura, Karagenc, Stadler and Shiels2001; Su et al., Reference Su, Deng and Leng2020; Larcombe et al., Reference Larcombe, Capewell, Jensen, Weir, Kinnaird and Glass2022). It is probable that these motif patterns have a level of variability between breeds and possibly within breed populations. It is also possible that evolution of the TashAT2-bound motif pattern in the host genome could be influenced by selective pressure, as interaction with a lethal pathogen infection could remove, over time, individuals with patterns that give rise to fatal disease (Tseng et al., Reference Tseng, Wong, Liao, Chen, Lee, Yen and Chang2021). Mammalian HMGA proteins are known to operate in important developmental pathways and are linked to haematopoiesis, epithelial–mesenchymal transition and adipogenesis (Su et al., Reference Su, Deng and Leng2020; Vignali and Marracci, Reference Vignali and Marracci2020). Thus, selective breeding for particular traits may influence the pattern of motifs (and epigenome architecture) encoded by genomes of cattle breeds that are differentially susceptible to pathogen infection.

Figure 1. Differences in the number and location of AT-hook binding site motifs between Bos taurus and Bos indicus genomes (A) Consensus DNA sequence motif bound by parasite TashAT2 compared to mammalian HMGA. AT rich regions are in red. (B) CIRCOS summary plot of genes displaying a different number of TashAT2 binding sites in Bos indicus (red) and Bos taurus (blue). Zoomed views for chromosomes 2, 8 and 16: genes in the EGF and integrin signalling pathways with different numbers of TashAT2 binding site motifs and differing in expression between Holstein and Sahiwal infected cells are indicated by green boxes (ITGA4, MAPK10 and LAMC1). (C) Integrin pathway genes differentially expressed between T. annulata infected Bos taurus vs Bos indicus infected cell lines displaying different numbers of predicted TashAT2 binding site motifs (data derived from Larcombe et al., Reference Larcombe, Capewell, Jensen, Weir, Kinnaird and Glass2022). Relative expression is shaded using a red-to-blue gradient, with red indicating higher values and blue indicating lower values. GULP1 (highlighted red) has been experimentally validated as a modulated target gene in a TashAT2 transfected-BoMac cell line (Durrani et al., Reference Durrani, Kinnaird, Cheng, Brühlmann, Capewell, Jackson, Larcombe, Olias, Weir and Shiels2023).

Genetic diversity and the evolution of pathogen–host interaction

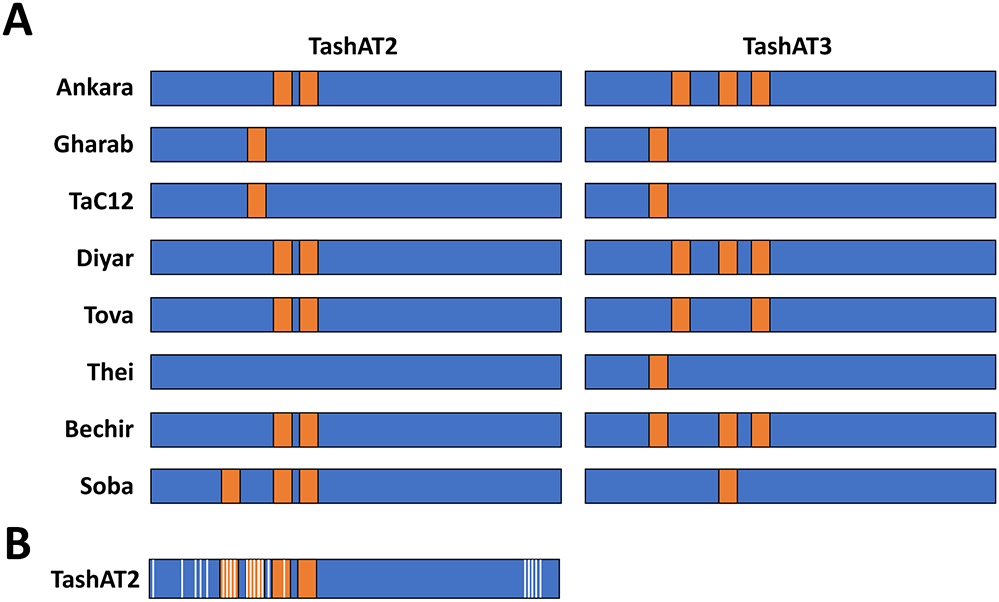

An additional potential contributor to altered infected cell gene expression is diversity in the pattern of AT-hook domains across TashAT2/3 alleles. In the analysis of (Weir et al., Reference Weir, Karagenç, Baird, Tait and Shiels2010), Ten major arrangements were identified across 8 sequenced isolates. These findings have been validated, by analysis of parasite genomes derived from multiple clonal cell lines. The results identified TashAT2/3 alleles displaying variable numbers and spacing of AT-hooks. Moreover, dN/dS analysis provides evidence for positive selection of amino acid substitution primarily within the first 2 AT-hook domains of TashAT2 and towards the C-terminus of the protein (Figure 2). The negatively charged C-terminal tail of HMGA proteins show variable phosphorylation patterns that are thought to influence DNA binding efficiency or protein partner binding, which may contribute to cellular transformation (Sgarra et al., Reference Sgarra, Maurizio, Zammitti, Lo Sardo, Giancotti and Manfioletti2009; Su et al., Reference Su, Deng and Leng2020). In analogy, the substitutions highlighted for the C-terminal region of TashAT2 overlap with predicted PEST motifs (Shiels et al., Reference Shiels, Langsley, Weir, Pain, McKellar and Dobbelaere2006) and phosphorylation sites for protein kinases. Post-translational modification of PEST regions in nuclear proteins are considered important for partner binding and modulation of function, including oncogenic activity (Sarfraz et al., Reference Sarfraz, Afzal, Khattak, Saddozai, Li, Zhang, Madni, Haleem, Duan, Wu, Ji and Ji2021).

Figure 2. Amino acid diversity and rearrangement of AT-hook motifs in TashAT2/3 alleles (A) Pattern of AT-hook motifs predicted from allelic DNA sequences of TashAT2 and TashAT3. The regions containing the TashAT locus were extracted from 8 publicly available genomes (ENA project ID: PRJEB65114) previously aligned to the C9 Ankara reference strain using BEDtools. The number and positions of AT-hook motifs were identified using SMART and the core (GRP) motif for each putative site validated manually. Relative positions of each AT-hook domain are denoted Orange. (B) The TashAT2 sequences were compared using JCoDA to identify sites of positive selection of amino acid substitution. The relative positions of sites with a probability of (dN/dS > 1) greater than 0.9 (white) were overlaid on a composite cartoon of the TashAT2 alleles.

The data for selection of variant pathogen AT-hook domains, together with evidence that TashAT alleles display geographical substructuring (Weir et al., Reference Weir, Karagenç, Baird, Tait and Shiels2010), implies that T. annulata has co-evolved with local host genetic backgrounds to recognise divergent DNA target motifs. In this scenario, the random probability of disease would be influenced by both the genetic background of the infecting parasite populations and the genome of the infected host, leading to a wide range of infection outcomes, between and within animal breeds. Over evolutionary time the pathogen–host relationship has produced B. indicus genomes that possess patterns of (AT-rich) DNA binding motifs that, in general, promote tolerance; while European, Bos taurine breeds, selected for productivity traits in the absence of pathogen pressure, display greater susceptibility. The model predicts that (1) parasite TashAT proteins contribute to the construction of chromatin architectures that promote gene expression changes linked to a spectrum of disease outcomes; (2) differences in the pattern of motifs that interact with AT-hook proteins are linked to breed morphological traits and disease susceptibility and (3) the binding of variant TashAT factors to variant host genome contributes to disease susceptibility.

Analogous viral and bacterial epigenetic modulators

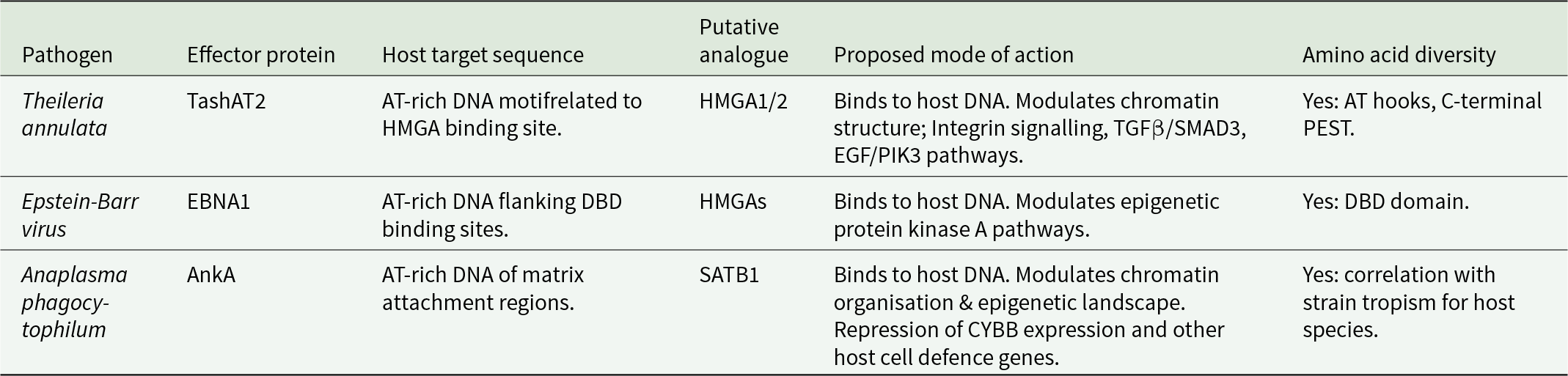

A relevant question in relation to the above model is whether it is applicable for other intracellular pathogen–host interactions. Evidence for multiple pathogen factors manipulating the host epigenome has been generated (Silmon De Monerri and Kim, Reference Silmon De Monerri and Kim2014; Cheeseman and Weitzman, Reference Cheeseman and Weitzman2015; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Hollin, Lenz and Le Roch2021). The 2 examples of pathogen nucleomodulins most related to T. annulata are the Epstein–Barr nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) of Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) and the ankaryin A (AnkA) protein of Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of 3 protozoal, viral and bacterial nucleomodulins that act as (putative) analogues of host architectural transcription factors

Like Theileria, EBV infection is linked to a transformed host cell phenotype and associated pathology (Burkitt’s lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma). Latent virus infection requires attachment of the EBV episome to host chromosomes. This is achieved, in part, via the DNA binding functions of EBNA1 (Frappier, Reference Frappier2012). DNA binding has been shown to involve at least 3 domains. Two domains (CBD1 and CBD2) possess AT-hook motifs that show similarity to mammalian HMGA1a (Kanda et al., Reference Kanda, Horikoshi, Murata, Kawashima, Sugimoto, Narita, Kurumizaka and Tsurumi2013) and Theileria TashAT2/3. Furthermore, the episomal tethering function of EBNA1 can be replicated by HMGA1. Genome-wide mapping of EBV episome attachment sites identified enrichment of AT-rich DNA, flanking C-terminal EBNA1 DNA binding domain (DBD) sites and the epigenetic H3K9me3 mark (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Tanizawa, De Leo, Vladimirova, Kossenkov, Lu, Showe, Noma and Lieberman2020). These sites were associated with transcriptional repression of genes with neural functions or genes operating in the protein kinase A pathway. Thus, EBNA1 binds to host DNA and, like TashAT2, has been postulated to act as an analogue of HMGAs (Coppotelli et al., Reference Coppotelli, Mughal, Callegari, Sompallae, Caja, Luijsterburg, Dantuma, Moustakas and Masucci2013) to modulate the host cell epigenetic landscape resulting in altered gene expression. In further analogy to TashAT2, study of EBNA1 gene sequences from different viral strains identified a high level of sequence divergence (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Brennan, Miles, Moss, Burrows and Burrows2008). While evidence for amino acid substitution in the AT-hook domains is limited, the majority (68%) of isolates predict alterations in the C-terminal DBD. It was proposed that these substitutions may be linked to the evolution and geographical origin of the viral isolate.

Anaplasma phagocytophilum is a tick-borne, Gram-negative bacteria placed in the order Rickettsiales. It is the cause of anaplasmosis in domestic animals and humans. Human granulocytic anaplasmosis is the third most common tick-borne disease in Europe and the USA. The outcome on infection is variable; most patients have mild clinical signs but for 36%, infection results in hospitalisation, with 7% of clinical cases requiring intensive care (Dumler, Reference Dumler2012). Anaplasma phagocytophilum infects neutrophils and, like Theileria, pathology is linked to a proinflammatory cytokine storm with similarity to COVID-19 (Ramanujam et al., Reference Ramanujam, Nasrullah, Ashraf, Bahr and Malik2021). In further analogy to T. annulata, infection of the host cell results in activation of PI3K/AKT and NF-ĸB pathways to protect against apoptosis (Sarkar et al., Reference Sarkar, Hellberg, Bhattacharyya, Behnen, Wang, Lord, Möller, Kohler, Solbach and Laskay2012). An extensive reprogramming of gene expression (Borjesson et al., Reference Borjesson, Kobayashi, Whitney, Voyich, Argue and DeLeo2005) that moderates production of proteins involved in innate immunity operates (Garcia-Garcia et al., Reference Garcia-Garcia, Barat, Trembley and Dumler2009b).

Modulation of gene expression is generated through alteration of host cell chromatin architecture. Wide-scale manipulation of the epigenome is mediated by the AnkA protein that is secreted and translocated to the neutrophil nucleus via an importin-b-, RanGTP-dependent mechanism (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Wang, Clemens, Grab and Dumler2022). AnkA manipulates the epigenome by binding to runs of AT-rich DNA and recruiting histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) to the CYBB promoter region. Recruitment of HDAC1 causes silencing of CYBB expression, promoting pathogen survival (Rennoll-Bankert et al., Reference Rennoll-Bankert, Garcia-Garcia, Sinclair and Dumler2015). DNA binding is achieved by 4 central ankyrin repeats, together with a C-terminal AT-hook like domain with a core RGR motif. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) studies indicate that AnkA acts genome wide to generate large scale changes to the epigenome of the infected cell (Garcia-Garcia et al., Reference Garcia-Garcia, Rennoll-Bankert, Pelly, Milstone and Dumler2009a; Dumler et al., Reference Dumler, Sinclair, Pappas-Brown and Shetty2016). Moreover, AnkA binds to regions of the genome similar to those of matrix attachment regions and lamina associated domains. Therefore, AnkA could act as an analogue of host transcription factors, such as the special AT-rich binding-protein-1 (SATB1), also a target of HIV-1, trans-activator of transcription modulatory activity (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Purbey, Ravi, Mitra and Galande2005), that organise chromatin architecture into topological domains within the nucleus, that in turn, influence the transcriptional programme of the cell (Sinclair et al., Reference Sinclair, Rennoll-Bankert and Dumler2014).

Similar to TashAT2/3 and EBNA1, AnkA displays a high degree of sequence divergence across bacterial strains (Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Schauer, Freyburger, Petrovec, Schaarschmidt-Kiener, Liebisch, Runge, Ganter, Kehl, Dumler, Garcia-Perez, Jensen, Fingerle, Meli, Ensser, Stuen and Von Loewenich2011). Most nucleotide changes are nonsynonymous, predicting amino acid substitution. While no geographical subclustering has been found, different AnkA gene clusters correlate with strain tropism for different host species, suggesting a level of co-evolution and adaptation. There is no evidence, to date, that diversity in AnkA impacts on disease outcome. However, functional diversity is thought possible (Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Schauer, Freyburger, Petrovec, Schaarschmidt-Kiener, Liebisch, Runge, Ganter, Kehl, Dumler, Garcia-Perez, Jensen, Fingerle, Meli, Ensser, Stuen and Von Loewenich2011): and it may be noteworthy, that enriched binding of AnkA to DNA upstream of target gene transcriptional start sites displayed significant variability between the 3 different human genomes investigated (Dumler et al., Reference Dumler, Sinclair, Pappas-Brown and Shetty2016).

Conclusions

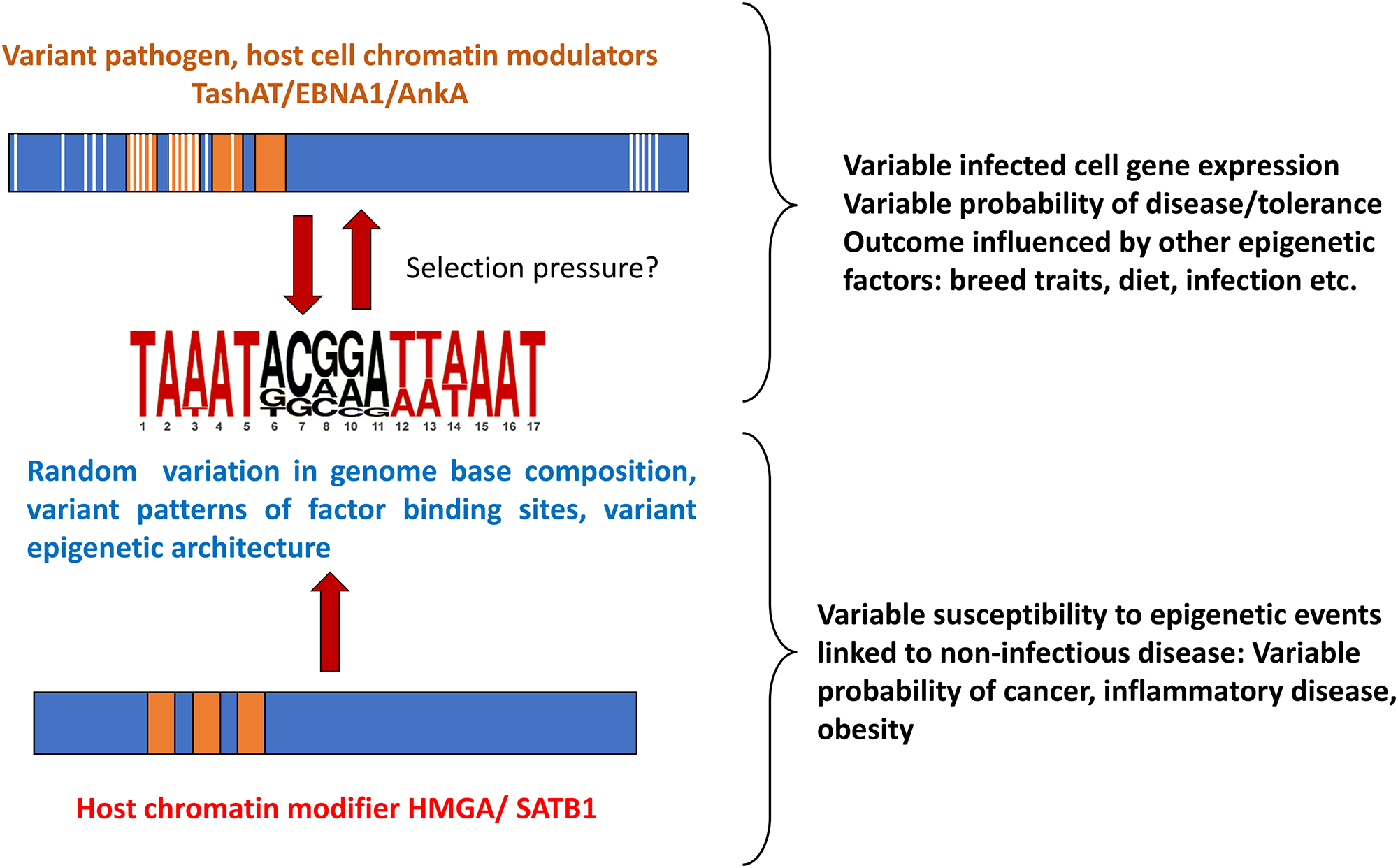

How genome diversity and environmental factors interact to influence susceptibility to disease is not fully understood. The model postulated (outlined in Figure 3) whereby variant DNA motifs interact with divergent regulatory proteins to construct variable epigenetic landscapes, suggests a link between genome, environment and lifestyle which could be important for understanding how the response to infection can vary so widely. For example, the infected cell epigenome and susceptibility to theileriosis may be influenced by host genome, parasite genome, livestock environment/nutrition and infection of the bovine host by other pathogens. Moreover, pathogen factors may mimic host molecules (e.g. HMGA, SATB1) (Coppotelli et al., Reference Coppotelli, Mughal, Callegari, Sompallae, Caja, Luijsterburg, Dantuma, Moustakas and Masucci2013; Sinclair et al., Reference Sinclair, Rennoll-Bankert and Dumler2014; Durrani et al., Reference Durrani, Kinnaird, Cheng, Brühlmann, Capewell, Jackson, Larcombe, Olias, Weir and Shiels2023) that function as base composition readers (Quante and Bird, Reference Quante and Bird2016) and shape chromatin architecture during embryonic development (Goolam and Zernicka-Goetz, Reference Goolam and Zernicka-Goetz2017; Panchal et al., Reference Panchal, Wichmann, Grenman, Eckhardt, Kunz-Schughart, Franke, Dietz and Aigner2020; Su et al., Reference Su, Deng and Leng2020; Vignali and Marracci, Reference Vignali and Marracci2020). These host factors have been implicated in a range of conditions, including neoplasia and disease linked to immune dysfunction (Reeves, Reference Reeves2001; Treff et al., Reference Treff, Pouchnik, Dement, Britt and Reeves2004; Henriksen et al., Reference Henriksen, Stabell, Meza-Zepeda, Lauvrak, Kassem and Myklebost2010; Frömberg et al., Reference Frömberg, Engeland and Aigner2018; Panchal et al., Reference Panchal, Wichmann, Grenman, Eckhardt, Kunz-Schughart, Franke, Dietz and Aigner2020; Vignali and Marracci, Reference Vignali and Marracci2020). Based on the premise that pathogen infection could influence selection of genomes with particular patterns of motifs to which the host factors bind: further study of pathogen-host interaction has potential to provide information on how variable susceptibility to diseases unrelated to infection has evolved, with the caveat that individual outcomes can still depend on just a roll of the dice.

Figure 3. Overview of the proposed model for pathogen-host interaction and evolution of disease susceptibility.

Limitations of the model and future perspectives

The model outlined above has limitations and requires additional data. To date, it is based on 2 reference genomes representing B. taurus and B. indicus. Analysis of genome sequence representing multiple breeds of both subspecies is required; with the proviso that a degree of diversity in the TashAT2 binding site motif pattern (number, position and potentially sequence) is predicted between different breeds and between individuals within a breed. It may also be of interest to identify the gene expression profile of infected leukocytes, and the binding site pattern in the genome, of water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). This could provide information on whether evolution of tolerance to T. annulata displayed by native cattle breeds and Bubalus bubalis reflects related or divergent mechanisms.

While pathogen modulation of the host epigenome may be a relatively common strategy (Bierne and Pourpre, Reference Bierne and Pourpre2020; Silmon De Monerri and Kim, Reference Silmon De Monerri and Kim2014; Cheeseman and Weitzman, Reference Cheeseman and Weitzman2015), it is unknown how applicable the above model is to intracellular pathogens, in general. Consensus AT-hook domains are prevalent in eukaryotes but thought to be rare in prokaryotes (Aravind, Reference Aravind1998). AT-hook proteins are encoded by herpes viruses and AT-hook domains have been reported as shared between viral, host and prokaryotic DNA binding proteins (Dreyfus et al., Reference Dreyfus, Farina and Farina2018). Multiple extended nucleic acid binding AT-hook motifs, and other protein domains with potential to act as base composition readers, have been described (Filarsky et al., Reference Filarsky, Zillner, Araya, Villar-Garea, Merkl, Längst and Németh2015; Quante and Bird, Reference Quante and Bird2016). The model, therefore, may be applicable to other intracellular pathogens. Even if limited to the 3 examples given above; over evolutionary time, a considerable proportion of the human and animal population will have been exposed to these pathogen–host interactions.

Additional data could be obtained by: the assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing of B. indicus and B. taurus infected leukocytes (Buenrostro et al., Reference Buenrostro, Wu, Chang and Greenleaf2015), to compare regions of chromatin accessibility; ChIP-sequencing (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Mortazavi, Myers and Wold2007), to functionally identify genomic locations that TashAT2 protein binds; comparison of the gene expression profile modulated by distinct TashAT2/3 alleles (Durrani et al., Reference Durrani, Kinnaird, Cheng, Brühlmann, Capewell, Jackson, Larcombe, Olias, Weir and Shiels2023); investigation of whether TashAT2 binding site diversity is driven by selection (Sironi et al., Reference Sironi, Cagliani, Forni and Clerici2015) or has evolved passively (McShea, Reference McShea1994).

Author contributions

B.R.S. conceived and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. B.R.S., P.C., and P.R. all contributed to further drafting and editing. Additional analysis was performed by P.C.

Financial support

B.R.S. was awarded a grant from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) https://www.ukri.org/councils/bbsrc/ Grant BB/L004739/1. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.